Abstract

Background

The legal climate for cannabis use has dramatically changed with an increasing number of states passing legislation legalizing access for medical and recreational use. Among cancer patients, cannabis is often used to ameliorate adverse effects of cancer treatment. Data are limited on the extent and type of use among cancer patients during treatment and the perceived benefits and harms. This multicenter survey was conducted to assess the use of cannabis among cancer patients residing in states with varied legal access to cannabis.

Methods

A total of 12 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, across states with varied cannabis-access legal status, conducted surveys with a core questionnaire to assess cannabis use among recently diagnosed cancer patients. Data were collected between September 2021 and August 2023 and pooled across 12 cancer centers. Frequencies and 95% confidence intervals for core survey measures were calculated, and weighted estimates are presented for the 10 sites that drew probability samples.

Results

Overall reported cannabis use since cancer diagnosis among survey respondents was 32.9% (weighted), which varied slightly by state legalization status. The most common perceived benefits of use were for pain, sleep, stress and anxiety, and treatment side effects. Reported perceived risks were less common and included inability to drive, difficulty concentrating, lung damage, addiction, and impact on employment. A majority reported feeling comfortable speaking to health-care providers though, overall, only 21.5% reported having done so. Among those who used cannabis since diagnosis, the most common modes were eating in food, smoking, and pills or tinctures, and the most common reasons were for sleep disturbance, followed by pain and stress and anxiety with 60%-68% reporting improved symptoms with use.

Conclusion

This geographically diverse survey demonstrates that patients use cannabis regardless of its legal status. Addressing knowledge gaps concerning benefits and harms of cannabis use during cancer treatment is critical to enhance patient-provider communication.

Evidence of cannabis use, including for medicinal purposes, comes from archaeological evidence and early written records dating as early as 1500 BCE (1). In the late 19th century, the Lancet published an article by J. Russel Reynolds, describing the use of “cannabis indica,” noting, in his experience, effectiveness in treating “senile insomnia,” dysmenorrhea, and some types of painful neuropathy (1,2). These early reports also highlighted the challenges of dosing and limiting the toxic side effects, including dysphoria, that remain relevant today. The legal climate around cannabis use changed in the 1900s and, because of strict control along with its classification as a schedule I drug in the United States (ie, drugs, substances, or chemicals with no currently accepted medical use and high potential for abuse) (3), research into potential medicinal application of cannabis and its potential benefits and harms was severely restricted.

The legal landscape for cannabis and cannabinoids use has dramatically changed over the past decade (4). Although cannabis remains classified as a schedule I drug, as of November 8, 2023, a total of 39 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation for the legal use of cannabis for medical conditions, and 24 states and the District of Columbia have fully legalized cannabis for medical and adult nonmedical use (5,6). One common use of medical cannabis has been to manage chemotherapy-related symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Recognizing the benefit of cannabis for chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting, the drug Marinol (dronabinol), a synthetic cannabinoid, was developed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1985 (7) and classified as a schedule II drug, which must be prescribed by a health-care provider. With state legalization of cannabis, a wide variety of cannabis products, with varying potency, cannabinoid constituents and ratios, and methods of delivery are more readily available to consumers, including cancer patients.

Cancer patients use cannabis and cannabinoids during treatment for a variety of symptoms beyond nausea, including pain, sleep disturbance, and anxiety (8-13). Several surveys estimate that one-quarter of cancer patients use cannabis and cannabinoids for symptom management during their treatment (8-11,13,14). Given the rapidly changing availability of a wide variety of products and modes of delivery, there remains a significant gap in knowledge about the extent and type of use among cancer patients during treatment and the perceived benefits and harms.

The current survey was undertaken to assess the use of cannabis products among cancer patients residing in states with varied legal access to cannabis. Common elements of the survey conducted by 12 National Cancer Institute (NCI)–Designated Cancer Centers across the United States included current and past use of cannabis, mode of use, reasons for use, perception of harms and benefits, and health-care provider recommendations regarding use. We present a summary of the results of the survey taking into consideration the legal status of the state of residence of the cancer patients.

Methods

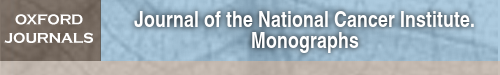

A total of 12 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers were awarded supplemental funding to conduct surveys assessing cannabis use among recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cancer centers responded to a call for administrative supplements, and applications were administratively reviewed by NCI. Selected sites were in states with varied legal status for medical and recreational cannabis use at the time of the survey. The 12 cancer centers independently received approval from their institutional review boards and collected data from September 2021 to August 2023. Eligible participants were patients diagnosed with cancer who were undergoing treatment or recently completed cancer treatment and who resided in their respective cancer center’s catchment area (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of NCI-Designated Cancer Center sites and state legalization status (2023). NCI = National Cancer Institute; OSHU = Oregon Health and Science University.

Cancer centers were responsible for sampling patients within their catchment area with the goal of 1000 completed surveys. Centers were asked to recruit patients who were currently undergoing treatment or who had completed treatment within the past 2 years. Enrolled patients were diagnosed and treated between January 2017 and December 2020. Cancer centers used a variety of methods to recruit patients, including invitations sent through mail, email, phone calls, text messages, and electronic medical record–based messaging. In addition, a combination of web-based, telephone, and paper-based surveys were used across cancer centers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample size and sampling methods

| NCI-Designated Cancer Center | Abramson | Case | Fred Hutchinson | Hollings, Medical University of South Carolina | Mayo Clinic | Memorial Sloan- Kettering | Moffit | Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University | Sidney Kimmel | Sylvester, University of Miami | Moores, University of California San Diego | Masonic, University of Minnesota | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location surveyeda | DE, PA, NJ | OH | WA | SC | AZ, FL, MN | CT, NY, NJ | FL | OR | PA, NJ | FL | CA | MN | ||

| Legal status of area surveyed |

|

Mixed (medical and decriminalized) | Fully legal (medical and decriminalized) | Fully illegal (no medical and not decriminalized) |

|

|

Mixed (medical and not decriminalized) | Fully legal (medical and decriminalized) |

|

Mixed (medical and not decriminalized) | Fully legal (medical and decriminalized) | Mixed (medical and decriminalized) | — | |

| No. sampledb | 5808 | — | 10 723 | 7749 | 10 000 | 3837 | 9043 | 3807 | 10 092 | — | 6849 | 2062 | 69 970 | |

| No. responded | 1054 | 334 | 1539 | 1036 | 2304 | 1258 | 1592 | 534 | 1568 | 232 | 954 | 775 | 13 180 | |

| Response rate, %b | 18.1 | — | 14.4 | 13.4 | 23.0 | 32.8 | 17.6 | 14.0 | 15.5 | — | 13.9 | 37.6 | 19 | |

| Prevalence of use since diagnosis | Unweighted, % (95% CI), 12 centers | 33.4 (30.5 to 36.2) |

32.2 (27.0 to 37.8) |

41.3 (38.8 to 43.8) |

28.4 (25.6 to 31.1) |

23.1 (21.4 to 24.9) |

30.8 (28.2 to 33.4) |

46.9 (44.5 to 49.4) |

54.9 (50.6 to 59.2) |

33.3 (31.0 to 35.6) |

44.7 (38.1 to 51.4) |

31.6 (28.5 to 34.7) |

20.9 (17.9 to 23.9) |

33.7 (32.9 to 34.5) |

| Weighted, % (95% CI), 10 centersb | 31.2 (28.4 to 34.2) |

— | 41.0 (38.5 to 43.6) |

26.0 (23.3 to 28.9) |

23.8 (22.1 to 25.6) |

29.4 (26.5 to 32.5) |

44.4 (41.9 to 46.9) |

55.0 (50.7 to 59.3) |

33.4 (30.6 to 36.4) |

— | 30.4 (27.3 to 33.7) |

25.3 (21.3 to 29.7) |

32.9 (31.9 to 33.9) |

|

| Survey administration | Web survey | Web survey or paper survey | Web survey or telephone survey | Web survey or telephone survey | Web survey | Web survey | Web survey | Web survey or paper survey | Web survey or paper survey | Web survey or paper survey | Web survey | Paper survey | ||

| Sampling method | Stratified random sampling | Convenience sampling | All eligible patients are sampled | Simple random sampling | Stratified random sampling | Stratified random sampling | All eligible patients are sampled | Stratified random sampling | Simple random sampling | Convenience sampling | All eligible patients are sampled | Stratified random sampling | ||

The state of residence was imputed based on the location of the cancer center if missing. Em dashes are for Case and Miami that didn’t conduct probability sampling (convenience sampling) and therefore no response is required for No. sampled and response rate, and data are not weighted. AZ = Arizona; CA = California; CI = confidence interval; CT = Connecticut; DE = Delaware; FL = Florida; MN = Minnesota; NJ = New Jersey; NY = New York; OH = Ohio; PA = Pennsylvania; SC = South Carolina; WA = Washington.

Sample size, response rate. and weighted estimate of the convenience sample of Miami and Case Western Cancer Center were not applicable.

For this survey, the terms cannabis and cannabinoids refer to any marijuana, cannabis concentrates, edibles, lotions, ointments, tinctures containing cannabis, cannabidiol-only products, pharmaceutical or prescription cannabinoids (eg, dronabinol, nabilone), and other products made with cannabis. A set of common core measures (15) were developed by NCI and approved by the centers and administered by each site. The core questions assessed current and past use of cannabis, modes of use, reasons for use, perception of harms and benefits, and health-care provider recommendations regarding use. De-identified data were sent to the coordinating center for cleaning and weighting.

Characteristics of the sample and past and current use of cannabis were assessed for respondents whose data were pooled from the 12 sites (n = 13 180). Respondents were characterized by state-level legalization status. We assigned 3 state-level legalization statuses for cannabis use (fully legal, legal for medical use, and fully illegal) to all respondents in the pooled dataset based on the state where the respondent lived at the time of cancer diagnosis. The “legal for medical use” category included the states where cannabis use was legalized for medical purposes and decriminalized and the states where cannabis use was legalized for medical purposes and not decriminalized. The “fully illegal” category included states where cannabis use was not legalized for medical purposes regardless of the decriminalization status. The legalization status for respondents who refused to report where they lived at the time of cancer diagnosis or were not asked this question was imputed using the location of the cancer center (Case Western, Fred Hutchinson, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Oregon Health and Science University Knight Cancer Institute, San Diego Moores, and Minnesota Masonic Cancer Centers did not have the variable “residence at diagnosis”). For example, the legalization status of the 8 respondents who refused to answer in the Abramson Cancer Center’s data was set as legal for medical use, which is the legalization status in Pennsylvania.

Analyses regarding perceived benefits and risks of cannabis use and communication with health-care providers about use were conducted only among respondents from the 10 cancer centers that used probability sampling methods (n = 12 614). Weighting was conducted for those sites from patient lists defining their catchment area with some stratifying the sample by cancer type, sex, race and ethnicity, or a combination of demographic variables (see Table 1). Survey weights were calculated accounting for patients’ probability of selection and patient nonresponse. Prior to weighting, using available patient-level data (eg, cancer type, sex, age, race and ethnicity, and marital status), nonresponse analysis was conducted within each cancer center. A multidimensional ranking approach to adjust the weights to sum to the cancer centers population of interest separately for each cancer center was implemented.

Weighted estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the core survey measures were calculated and presented for the 10 sites that drew probability samples, accounting for the complex survey design. The 10 sites that drew probability samples had a sample size of 12 614 respondents, which, with sampling weights applied, represent a population of 118 712 cancer patients across all catchment areas (see Supplementary Table 1, available online).

Analyses for prevalence and patterns of cannabis use, including frequency and duration, mode, reasons for use, and perceived therapeutic benefit of use, were conducted only among those who used cannabis since diagnosis and included only those sites that used probability sampling methods (n = 4163). We conducted Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. To compare the core measures by the state-level legalization status, we built multivariable logistic regression models and computed model–based estimates for the respondents’ reported cannabis use and the percentages of various patterns of cannabis use by legalization status, adjusted by categorical age, sex at birth, and race and ethnicity. We used an alpha of 0.05 to calculate 95% confidence intervals and statistical significance for all analyses. All data cleaning and analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Demographic description of respondents and cannabis use

For the 12 cancer centers combined, 13 180 cancer patients responded to the survey from a base population of 69 970 patients (Table 1). Among the 10 sites that drew probability samples, 12 614 responded to surveys for an overall response rate of 18%.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of all survey respondents according to whether they used cannabis before and/or after the diagnosis of cancer or never used. The median age of respondents was 65 years, ranging from 19 to 100 years. More than one-half of respondents were female, and the majority were White and college graduates or higher. There was representation from patients living in states across the spectrum of state cannabis policies governing use, including fully legal (39.8%), legalized for medical use (52.1%), and fully illegal (8.1%). Breast and prostate were the most frequently reported cancer types. Current treatment status was not reported for 19% of respondents; 18% reported being actively treated with either hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation, or a combination of therapies. Approximately one-quarter of patients used cannabis prior to diagnosis only (no use after diagnosis), and a similar percent reported use before and after diagnosis; 6% reported use since diagnosis only (not prior to diagnosis), and 38% reported never using cannabis. Respondents who reported using cannabis at any time before or after diagnosis differed from respondents who reported never using cannabis by all demographic characteristics and state policies governing cannabis use.

Table 2.

Characteristics of sample, 12 sites unweighted data

| Characteristic | Total |

Cannabis use before diagnosis only | Cannabis use since cancer diagnosis only |

Cannabis use before and since diagnosis |

Never used |

P

unweighted, 12 centers |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only before vs never used | Only since vs never used | Before and after vs never used | ||||||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||||

| All respondents, No., row % | 13 180 | 3461 (26.3) | 831 (6.3) | 3507 (26.6) | 5063 (38.4) | |||

| Age, y | ||||||||

| Median (range) | 64.53 (19-100) | 65.55 (20-94) | 60.02 (22-90) | 61.07 (19-92) | 66.97 (19-100) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Younger than 50 | 2148 (16.3) | 413 (11.9) | 221 (26.6) | 848 (24.2) | 646 (12.8) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| 50-64 | 3935 (29.9) | 1102 (31.8) | 266 (32.0) | 1186 (33.8) | 1350 (26.7) | |||

| 65 and older | 6624 (50.3) | 1867 (53.9) | 321 (38.6) | 1385 (39.5) | 2931 (57.9) | |||

| Missing | 473 (3.6) | 79 (2.3) | 23 (2.8) | 88 (2.5) | 136 (2.7) | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 5791 (43.9) | 1678 (48.5) | 275 (33.1) | 1624 (46.3) | 2147 (42.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0001 |

| Female | 7054 (53.5) | 1754 (50.7) | 544 (65.5) | 1829 (52.2) | 2861 (56.5) | |||

| Unknown or missing | 335 (2.5) | 29 (0.8) | 12 (1.4) | 54 (1.5) | 55 (1.1) | |||

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 344 (2.6) | 67 (1.9) | 32 (3.9) | 52 (1.5) | 189 (3.7) | |||

| Black | 788 (6.0) | 167 (4.8) | 62 (7.5) | 208 (5.9) | 342 (6.8) | |||

| Hispanic | 667 (5.1) | 133 (3.8) | 79 (9.5) | 184 (5.2) | 261 (5.2) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Other | 338 (2.6) | 95 (2.7) | 19 (2.3) | 117 (3.3) | 103 (2.0) | |||

| Unknown or missing | 427 (3.2) | 55 (1.6) | 23 (2.8) | 72 (2.1) | 91 (1.8) | |||

| White | 10 616 (80.5) | 2944 (85.1) | 616 (74.1) | 2874 (82.0) | 4077 (80.5) | |||

| Education | ||||||||

| High school graduate or less | 2278 (17.3) | 481 (13.9) | 144 (17.3) | 543 (15.5) | 1084 (21.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Some college | 2233 (16.9) | 611 (17.7) | 119 (14.3) | 631 (18.0) | 849 (16.8) | |||

| College graduate | 3475 (26.4) | 1000 (28.9) | 193 (23.2) | 938 (26.7) | 1302 (25.7) | |||

| Postgraduate | 3201 (24.3) | 956 (27.6) | 172 (20.7) | 767 (21.9) | 1279 (25.3) | |||

| Unknown or missing | 1993 (15.1) | 413 (11.9) | 203 (24.4) | 628 (17.9) | 549 (10.8) | |||

| State cannabis policy | ||||||||

| Fully legal | 5248 (39.8) | 1496 (43.2) | 260 (31.3) | 1589 (45.3) | 1751 (34.6) | <.0001 | .0377 | <.0001 |

| Legalized for medical use | 6865 (52.1) | 1645 (47.5) | 510 (61.4) | 1676 (47.8) | 2871 (56.7) | |||

| Fully illegal | 1067 (8.1) | 320 (9.2) | 61 (7.3) | 242 (6.9) | 441 (8.7) | |||

| Type of cancer | ||||||||

| Brain | 226 (1.7) | 42 (1.2) | 24 (2.9) | 77 (2.2) | 74 (1.5) | |||

| Breast | 2757 (20.9) | 710 (20.5) | 185 (22.3) | 631 (18.0) | 1172 (23.1) | |||

| Colorectal | 628 (4.8) | 152 (4.4) | 46 (5.5) | 182 (5.2) | 234 (4.6) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 387 (2.9) | 86 (2.5) | 31 (3.7) | 117 (3.3) | 146 (2.9) | |||

| Liver and gall bladder | 217 (1.6) | 38 (1.1) | 21 (2.5) | 71 (2.0) | 81 (1.6) | |||

| Pancreas | 188 (1.4) | 36 (1.0) | 14 (1.7) | 62 (1.8) | 68 (1.3) | |||

| Oropharyngeal | 285 (2.2) | 90 (2.6) | 11 (1.3) | 91 (2.6) | 85 (1.7) | |||

| Lung | 824 (6.3) | 244 (7.1) | 66 (7.9) | 220 (6.3) | 281 (5.6) | |||

| Melanoma | 714 (5.4) | 203 (5.9) | 26 (3.1) | 146 (4.2) | 324 (6.4) | |||

| Prostate | 1717 (13.0) | 546 (15.8) | 50 (6.0) | 371 (10.6) | 704 (13.9) | |||

| Gynecological | 520 (3.9) | 125 (3.6) | 32 (3.9) | 136 (3.9) | 223 (4.4) | |||

| Kidney | 453 (3.4) | 116 (3.4) | 22 (2.6) | 122 (3.5) | 184 (3.6) | |||

| Bladder | 362 (2.7) | 109 (3.1) | 16 (1.9) | 75 (2.1) | 362 (3.0) | |||

| Thyroid | 291 (2.2) | 63 (1.8) | 22 (2.6) | 77 (2.2) | 125 (2.5) | |||

| Lymphoma | 561 (4.3) | 151 (4.4) | 31 (3.7) | 154 (4.4) | 225 (4.4) | |||

| Myeloma | 221 (1.7) | 50 (1.4) | 25 (3.0) | 54 (1.5) | 90 (1.8) | |||

| Leukemia | 317 (2.4) | 65 (1.9) | 27 (3.2) | 77 (2.2) | 141 (2.8) | |||

| Other | 2354 (17.9) | 595 (17.2) | 182 (21.9) | 658 (18.8) | 877 (17.3) | |||

| Not reported | 1275 (9.7) | 318 (9.2) | 80 (9.6) | 406 (11.6) | 408 (8.1) | |||

| Cancer treatment status | ||||||||

| Hormonal only | 612 (4.6) | 154 (4.4) | 33 (4.0) | 163 (4.6) | 226 (4.5) | |||

| Active | 160 (26.1) | 48 (31.2) | 2 (6.1) | 44 (27.0) | 62 (27.4) | |||

| Completed | 75 (12.3) | 18 (11.7) | 8 (24.2) | 22 (13.5) | 27 (11.9) | |||

| Not reported | 377 (61.6) | 88 (57.1) | 23 (69.7) | 97 (59.5) | 137 (60.6) | |||

| Chemotherapy only | 1288 (9.8) | 273 (7.9) | 111 (13.4) | 372 (10.6) | 508 (10.0) | |||

| Active | 229 (17.8) | 42 (15.4) | 21 (18.9) | 73 (19.6) | 91 (17.9) | |||

| Completed | 569 (44.2) | 116 (42.5) | 46 (41.4) | 196 (52.7) | 208 (40.9) | |||

| Not reported | 490 (38.0) | 115 (42.1) | 44 (39.6) | 103 (27.7) | 209 (41.1) | |||

| Immunotherapy only | 549 (4.2) | 154 (4.4) | 46 (5.5) | 157 (4.5) | 186 (3.7) | |||

| Active | 92 (16.8) | 29 (18.8) | 6 (13.0) | 22 (14.0) | 35 (18.8) | |||

| Completed | 288 (52.5) | 81 (52.6) | 28 (60.9) | 100 (63.7) | 77 (41.4) | |||

| Not reported | 169 (30.8) | 44 (28.6) | 12 (26.1) | 35 (22.3) | 74 (39.8) | |||

| Radiation only | 1760 (13.4) | 460 (13.3) | 119 (14.3) | 452 (12.9) | 686 (13.5) | |||

| Active | 61 (3.5) | 18 (3.9) | 5 (4.2) | 10 (2.2) | 27 (3.9) | |||

| Completed | 1075 (61.1) | 288 (62.6) | 75 (63.0) | 304 (67.3) | 396 (57.7) | |||

| Not reported | 624 (35.5) | 154 (33.5) | 39 (32.8) | 138 (30.5) | 263 (38.3) | |||

| More than 1 treatment | 3828 (29.0) | 1015 (29.3) | 260 (31.3) | 1002 (28.6) | 1510 (29.8) | |||

| Activea | 1614 (42.2) | 473 (46.6) | 101 (38.8) | 472 (47.1) | 556 (36.8) | |||

| Completeda | 1209 (31.6) | 319 (31.4) | 81 (31.2) | 338 (33.7) | 465 (30.8) | |||

| Not reported | 1005 (26.3) | 223 (22.0) | 78 (30.0) | 192 (19.2) | 489 (32.4) | |||

| Not reportedb | 2492 (18.9) | 637 (18.4) | 152 (18.3) | 760 (21.7) | 837 (16.5) | |||

Considered active if at least 1 of the treatments is active.

Questions related to cancer treatment were not asked in the survey by Sylvester Cancer Center (University of Miami), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University Cancer Center.

Perceptions and beliefs about cannabis use among cancer patients

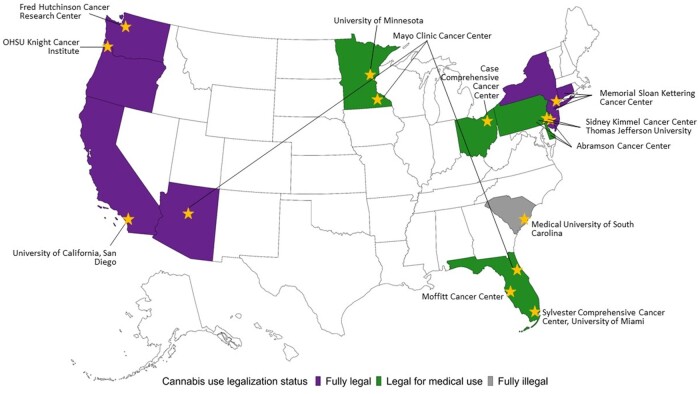

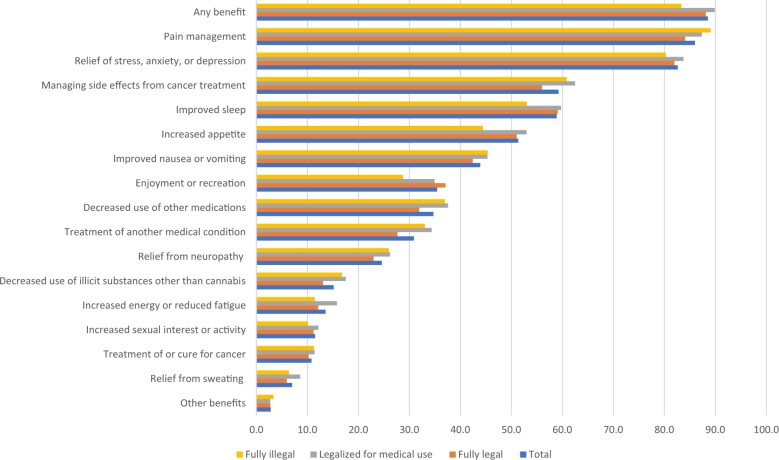

Regardless of past or current cannabis use, 88.5% of cancer patients sampled reported perceiving any benefit related to cannabis use (Figure 2). Benefits cited most frequently included pain management; relief of stress, anxiety, or depression; improved sleep; and managing side effects from cancer treatment. Reporting specific benefits did not appear to be related to state-level cannabis policies. Fewer (65%) cancer patients perceived any risks related to cannabis use (Figure 3). Specific enumerated risks included the inability to drive, difficulty concentrating, lung damage, and impaired memory. Reporting of specific risks among cancer patients varied by state cannabis policies, with inability to drive, impaired memory, risk of addiction to cannabis, and legal risks cited more frequently by patients residing in states where cannabis was fully illegal.

Figure 2.

Perceived benefits of cannabis use among cancer patients (n = 12 614; 10 sites).

Figure 3.

Perceived risks of cannabis use among cancer patients (n = 12 614; 10 sites).

Health-care provider discussions and recommendations

Table 3 presents the results concerning health-care provider communication for all and by state legal status. Among all respondents, more than 60% of patients reported that they would be somewhat or extremely comfortable in speaking with health-care providers about cannabis, even among states where cannabis use was illegal. However, a minority (21.5% of sample) of patients reported discussing cannabis use with a health-care provider, and of those who did, the majority (72.4%) discussed it with the treating oncologist. When stratified by state cannabis policies, 22.3% of respondents residing in states where cannabis was fully legal, 23.3% in states where cannabis was legalized for medical use, and 11.0% in states where cannabis was fully illegal discussed cannabis use with a health-care provider. Cancer patients who used cannabis since diagnosis were more likely to discuss cannabis use with health-care providers than patients who did not use cannabis since diagnosis (50.9% vs 7.6%; P < .001), and a higher percentage of those patients who used cannabis since diagnosis than those who didn’t reported discussing use with the primary care provider, treating oncologist, nurse, or other health-care provider (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

Table 3.

Communication with health-care providers about cannabis use among all respondentsa

| Characteristic | Total (n = 12 614) |

Fully legal (n = 5229) |

Legalized for medical use (n = 6318) |

Fully illegal (n = 1067) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | |

| Comfort in speaking to health-care providers about cannabisb | ||||||||||||

| Extremely uncomfortable | 1291 | 11 762 | 9.9 (9.3 to 10.5) | 578 | 6487 | 11.1 (10.0 to 12.2) | 599 | 4187 | 8.3 (7.6 to 9.0) | 114 | 1088 | 11.0 (9.0 to 13.1) |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 1486 | 13 539 | 11.4 (10.7 to 12.1) | 691 | 7565 | 13.0 (11.8 to 14.1) | 638 | 4588 | 9.1 (8.3 to 9.8) | 157 | 1386 | 14.0 (11.8 to 16.3) |

| Somewhat comfortable | 3058 | 28 028 | 23.6 (22.7 to 24.5) | 1424 | 16 077 | 27.6 (26.0 to 29.1) | 1354 | 9455 | 18.7 (17.7 to 19.8) | 280 | 2495 | 25.3 (22.4 to 28.1) |

| Extremely comfortable | 4960 | 45 925 | 38.7 (37.7 to 39.7) | 2246 | 25 381 | 43.5 (41.8 to 45.2) | 2215 | 15 806 | 31.3 (30.1 to 32.5) | 499 | 4737 | 48.0 (44.7 to 51.2) |

| Missing | 1819 | 19 458 | 16.4 (15.9 to 16.9) | 290 | 2843 | 4.9 (4.3 to 5.5) | 1512 | 16 450 | 32.6 (31.6 to 33.5) | 17 | 165 | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.5) |

| Discussed use with provider Missing responses (n = 227) | ||||||||||||

| No | 9680 | 90 919 | 78.5 (77.6 to 79.4) | 3931 | 44 183 | 77.7 (76.2 to 79.1) | 4816 | 38 024 | 76.7 (75.4 to 78.0) | 933 | 8712 | 89.0 (86.9 to 90.8) |

| Yes | 2707 | 26 062 | 21.5 (20.6 to 22.4) | 1167 | 13 098 | 22.3 (20.9 to 23.8) | 1408 | 11 817 | 23.3 (22.0 to 24.6) | 132 | 1148 | 11.0 (9.2 to 13.1) |

| Discussed with type of provider | ||||||||||||

| Primary care provider | 1073 | 10 151 | 38.9 (36.6 to 41.2) | 419 | 4789 | 36.8 (33.4 to 40.3) | 607 | 4951 | 41.5 (38.4 to 44.7) | 47 | 412 | 35.8 (27.2 to 45.4) |

| Oncologist involved with treatment | 1899 | 18 687 | 72.4 (70.1 to 74.5) | 881 | 9828 | 74.9 (71.6 to 78.0) | 924 | 8025 | 69.1 (66.0 to 71.9) | 94 | 834 | 75.6 (66.9 to 82.7) |

| Nurse or physician’s assistant involved with treatment | 924 | 9019 | 34.6 (32.4 to 37.0) | 420 | 4757 | 36.4 (32.9 to 40.0) | 462 | 3873 | 32.8 (29.9 to 36.0) | 42 | 390 | 34.1 (25.7 to 43.8) |

| Pharmacist | 140 | 1537 | 5.5 (4.6 to 6.7) | 60 | 771 | 5.5 (4.2 to 7.3) | 69 | 667 | 5.3 (4.0 to 6.9) | 11 | 99 | 8.3 (4.5 to 15.0) |

| Nutritionist or dietician | 150 | 1521 | 5.8 (4.8 to 7.0) | 55 | 622 | 5.5 (4.0 to 7.6) | 90 | 860 | 6.4 (5.0 to 8.2) | 5 | 39 | 3.1 (1.2 to 8.0) |

| Another health-care professional | 742 | 7157 | 27.1 (24.9 to 29.3) | 260 | 3202 | 24.1 (21.0 to 27.4) | 453 | 3712 | 31.4 (28.5 to 34.5) | 29 | 243 | 20.8 (14.2 to 29.6) |

| Provider recommended cannabis use Missing responses (n = 206) |

||||||||||||

|

11 222 | 10 4975 | 90.9 (90.2 to 91.5) | 4686 | 52 303 | 91.8 (90.8 to 92.8) | 5513 | 43 164 | 87.3 (86.2 to 88.4) | 1023 | 9507 | 96.9 (95.8 to 97.8) |

| Yes | 1186 | 12 030 | 9.1 (8.5 to 9.8) | 412 | 4934 | 8.2 (7.3 to 9.2) | 732 | 6743 | 12.7 (11.7 to 13.8) | 42 | 352 | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.3) |

| Recommended by type of provider | ||||||||||||

| Primary care provider | 274 | 2685 | 20.8 (18.1 to 23.8) | 73 | 804 | 16.0 (12.2 to 20.6) | 193 | 1822 | 25.2 (21.6 to 29.2) | 8 | 58 | 17.5 (8.7 to 31.9) |

| Oncologist involved with treatment | 519 | 5538 | 46.1 (42.7 to 49.6) | 181 | 2016 | 41.5 (35.8 to 47.4) | 321 | 3368 | 49.5 (45.1 to 54.0) | 17 | 154 | 46.7 (31.2 to 62.9) |

| Nurse or physician’s assistant involved with treatment | 263 | 2844 | 23.0 (20.0 to 26.2) | 114 | 1344 | 28.1 (22.8 to 34.1) | 138 | 1399 | 19.5 (16.1 to 23.4) | 11 | 101 | 28.1 (15.7 to 44.9) |

| Pharmacistc | 28 | 263 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.1) | 8 | 104 | 2.1 (0.5 to 3.7) | 15 | 119 | 1.8 (0.7 to 2.8) | 5 | 39 | 11.8 (1.5 to 22.1) |

| Nutritionist or dieticianc | 68 | 807 | 7.1 (4.9 to 9.3) | 25 | 330 | 7.7 (4.2 to 11.2) | 39 | 451 | 6.7 (3.8 to 9.6) | 4 | 26 | 7.8 (0.1 to 15.4) |

| Another health-care professional | 506 | 4940 | 41.0 (37.5 to 44.5) | 149 | 2011 | 39.8 (34.0 to 45.9) | 337 | 2790 | 41.8 (37.6 to 46.2) | 20 | 139 | 40.2 (26.7 to 55.3) |

Asked of all patients those who used and those who didn’t use; reported for sites that used probability sampling; percents are adjusted by age (3 categories as in Table 2), race (5 categories as in Table 2), and sex at birth. CI = confidence interval; n = unweighted sample size; No. = weighted to reflect estimates of population size.

This question was not asked in the survey of Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center (n = 1568). These respondents were included in the “missing” category.

Not adjusted to demographics because of small cells and model failures to converge.

Approximately 9% of cancer patients reported that a health-care provider recommended cannabis use, and of those, 46.1% reported that the oncologist involved with treatment recommended use (Table 3). In states where cannabis was fully legal and legalized for medical use, a higher percentage of patients reported that health-care providers recommended cannabis than in states where cannabis was fully illegal. Regardless of state policies governing cannabis use, the oncologist involved with treatment was the most common health-care provider making cannabis use recommendations.

Patterns of use among cancer patients who reported using cannabis since diagnosis

Approximately one-third of respondents reported using cannabis since being diagnosed with cancer (Table 4). More than 70% of respondents were aged 50 years or older, 55.8% were female, most were White race, and more than half were college graduates or had postgraduate education. Among cancer patients who reported using cannabis since cancer diagnosis, 81.4% used cannabis prior to diagnosis, and more than 51.7% were from states where cannabis was fully legal. Among cancer types, the highest percentage of cannabis use since diagnosis was for breast cancer (17.7%), followed by prostate cancer (10%).

Table 4.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cancer patients who used cannabis since diagnosis (n = 4163)

| Characteristic | n | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 4163 | 38 454 (32.9) | |

| Age, y | ||

| Median (range) | 4163 | 61.14 (19-92) |

| Younger than 50 | 979 | 8883 (23.1) |

| 50-64 | 1409 | 12 521 (32.6) |

| 65 and older | 1679 | 15 610 (40.6) |

| Missing | 96 | 1440 (3.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1817 | 16 347 (42.5) |

| Female | 2296 | 21 446 (55.8) |

| Unknown or missing | 50 | 661 (1.7) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 74 | 1049 (2.7) |

| Black | 246 | 3926 (10.2) |

| Hispanic | 214 | 1915 (5.0) |

| Other | 130 | 1365 (3.6) |

| Unknown or missing | 80 | 897 (2.3) |

| White | 3419 | 29 301 (76.2) |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate or less | 627 | 6285 (16.3) |

| Some college | 707 | 6889 (17.9) |

| College graduate | 1094 | 10 851 (28.2) |

| Postgraduate | 916 | 9620 (25.0) |

| Unknown or missing | 819 | 4809 (12.5) |

| Cannabis use prior to diagnosis | ||

| No | 772 | 7026 (18.3) |

| Yes | 3378 | 31 314 (81.4) |

| Unknown or missing | 13 | 113 (0.3) |

| State cannabis policy | ||

| Fully legal | 1852 | 19 873 (51.7) |

| Legalized for medical use | 2008 | 16 008 (41.6) |

| Fully illegal | 303 | 2573 (6.7) |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Brain | 98 | 719 (1.9) |

| Breast | 792 | 6802 (17.7) |

| Colorectal (combine colon and rectum) | 212 | 1805 (4.7) |

| Other gastrointestinal (esophagus, stomach, small intestine) | 138 | 2300 (6.0) |

| Liver and gall bladder | 82 | 774 (2.0) |

| Pancreas | 72 | 842 (2.2) |

| Oropharyngeal | 96 | 924 (2.4) |

| Lung | 272 | 2530 (6.6) |

| Melanoma | 164 | 1210 (3.1) |

| Prostate | 415 | 3840 (10.0) |

| Gynecologic malignancy (combine cervix, cervical, uterine, ovary) | 163 | 1434 (3.7) |

| Kidney | 139 | 1108 (2.9) |

| Bladder | 88 | 661 (1.7) |

| Thyroid | 97 | 779 (2.0) |

| Lymphoma (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma) | 179 | 1647 (4.3) |

| Myeloma | 73 | 643 (1.7) |

| Leukemia | 91 | 656 (1.7) |

| Other | 816 | 6266 (16.3) |

| Not reported | 478 | 6099 (15.9) |

| Cancer treatment status | ||

| Hormonal only | 197 | 1304 (3.4) |

| Active | 46 | 375 (28.8) |

| Completed | 30 | 186 (14.3) |

| Not reported | 121 | 743 (56.9) |

| Chemotherapy only | 451 | 3559 (9.3) |

| Active | 95 | 928 (26.1) |

| Completed | 244 | 1868 (52.5) |

| Not reported | 112 | 763 (21.5) |

| Immunotherapy only | 181 | 1182 (3.1) |

| Active | 28 | 275 (23.2) |

| Completed | 128 | 752 (63.6) |

| Not reported | 25 | 156 (13.2) |

| Radiation only | 564 | 3752 (9.8) |

| Active | 15 | 175 (4.7) |

| Completed | 382 | 2449 (65.3) |

| Not reported | 167 | 1128 (30.1) |

| More than 1 treatment | 1220 | 10 508 (27.3) |

| Activea | 573 | 5386 (51.3) |

| Completeda | 420 | 3753 (35.7) |

| Not reported | 227 | 1369 (13.0) |

| Not reportedb | 916 | 13 137 (34.2) |

Considered active if at least 1 of the treatments is active.

Questions related to cancer treatment were not asked in the survey by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Oregon Health and Science University Knight Cancer Center. n = unweighted sample size; No. = weighted to reflect estimates of population size.

Frequency of cannabis use

Among cancer patients who used cannabis since diagnosis, 60% reported current use (Table 5). The median number of days cancer patients reported using cannabis within the past 30 days was 17.1 (range = 14.8-19.5 days). Approximately 40% used cannabis up to 10 days within the past 30 days, 13.1% used 11 to 20 days, and 29.9% used between 21 and 30 days. Estimates of current cannabis use varied by state cannabis policies governing use with the percentage of current use being higher among patients residing in states where cannabis was fully legal (59.0%, P = .010) and legalized for medical use (62.7%, P < .001) than in states where cannabis was fully illegal (50.0%). The median number of days for current use differed by state cannabis policies, with cancer patients who resided in states where cannabis was fully illegal reporting a higher median number of days used than cancer patients who resided in states where cannabis was legalized for medical use (19.1 vs 14.2, P < .001).

Table 5.

Frequency and duration of use among cancer patients who used cannabis since cancer diagnosis (weighted, 10 centers; n = 4163)a

| Total (n = 4163) |

Fully legal (n = 1852) |

Legalized for medical use (n = 2008) |

Fully illegal (n = 303) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | n | No. | Weighted percent (95% CI) | P, fully legal vs fully illegal | P, legalized for medical vs fully illegal |

|

||||||||||||||

| No | 1596 | 15 311 | 40.0 (38.2 to 41.9) | 714 | 8178 | 41.0 (38.2 to 43.9) | 734 | 5873 | 37.3 (34.7 to 39.9) | 148 | 1261 | 50.0 (43.8 to 56.1) | .0101 | .0002 |

| Yes | 2528 | 22 791 | 60.0 (58.1 to 61.8) | 1118 | 11 514 | 59.0 (56.1 to 61.8) | 1255 | 9965 | 62.7 (60.1 to 65.3) | 155 | 1312 | 50.0 (43.9 to 56.2) | ||

| No. days, median (range) | 2280 | 19 284 | 17.1 (14.8 to 19.5) | 907 | 8605 | 18.1 (15.7 to 20.5) | 1218 | 9366 | 14.2 (11.8 to 16.6) | 70 | 581 | 19.1 (16.4 to 21.9) | .3012 | <.0001 |

| 0-10 | 1184 | 9334 | 40.4 (38.1 to 42.7) | 356 | 3574 | 30.0 (26.9 to 33.4) | 774 | 5328 | 54.3 (51.1 to 57.4) | 54 | 433 | 33.8 (26.3 to 42.2) | .387 | <.0001 |

| 11-20 | 327 | 3050 | 13.1 (11.6 to 14.7) | 160 | 1488 | 13.2 (11.1 to 15.8) | 136 | 1264 | 12.0 (9.9 to 14.4) | 31 | 298 | 21.7 (15.4 to 29.7) | .0125 | 0.0034 |

| 21-30 | 769 | 6899 | 29.9 (27.9 to 32.1) | 391 | 3543 | 29.9 (26.9 to 33.1) | 308 | 2774 | 28.3 (25.4 to 31.4) | 70 | 581 | 44.1 (36.0 to 52.5) | .0012 | 0.0003 |

|

||||||||||||||

| No | 1185 | 10 404 | 27.9 (26.2 to 29.7) | 483 | 4934 | 25.5 (23.1 to 28.0) | 590 | 4522 | 29.5 (27.1 to 32.0) | 112 | 948 | 38.8 (32.9 to 44.9) | <.0001 | .0039 |

| Yes | 2794 | 26 452 | 72.1 (70.3 to 73.8) | 1279 | 14 141 | 74.5 (72.0 to 76.9) | 1333 | 10 768 | 70.5 (68.0 to 72.9) | 182 | 1542 | 61.3 (55.1 to 67.1) | ||

| Every day, % | 1218 | 10 893 | 41.0 (38.7 to 43.2) | 532 | 5728 | 40.2 (36.9 to 43.7) | 610 | 4528 | 42.0 (38.9 to 45.2) | 76 | 636 | 40.3 (32.8 to 48.3) | .9901 | .6879 |

| Few times per wk, % | 596 | 5846 | 21.8 (20.0 to 23.7) | 270 | 2903 | 20.4 (17.9 to 23.2) | 283 | 2550 | 23.2 (20.5 to 26.2) | 43 | 393 | 25.2 (18.9 to 32.8) | .1903 | .5972 |

| Few times per mo, % | 453 | 4333 | 15.5 (13.9 to 17.3) | 221 | 2489 | 16.8 (14.3 to 19.5) | 197 | 1569 | 13.8 (11.8 to 16.2) | 35 | 275 | 17.2 (12.4 to 23.5) | .8779 | .2372 |

| ≤once per mo, % | 517 | 5274 | 19.3 (17.5 to 21.3) | 251 | 2954 | 20.1 (17.5 to 23.1) | 239 | 2090 | 19.0 (16.5 to 21.8) | 27 | 230 | 14.9 (10.0 to 21.7) | .1458 | .2450 |

|

||||||||||||||

| No | 644 | 5990 | 21.3 (19.6 to 23.2) | 267 | 2607 | 20.0 (17.4 to 22.8) | 316 | 2862 | 22.3 (19.8 to 25.0) | 61 | 521 | 24.1 (18.8 to 30.3) | .1816 | .5696 |

| Yes | 2502 | 21 662 | 78.7 (76.9 to 80.4) | 1057 | 10 283 | 80.0 (77.3 to 82.6) | 1248 | 9725 | 77.7 (75.0 to 80.2) | 197 | 1654 | 75.9 (69.7 to 81.2) | ||

| Every day, % | 929 | 7880 | 36.2 (34.0 to 38.5) | 375 | 3636 | 35.4 (32.0 to 39.0) | 492 | 3737 | 38.1 (34.9 to 41.3) | 62 | 507 | 30.3 (23.7 to 37.8) | .2207 | .0611 |

| Few times per wk, % | 473 | 4126 | 18.8 (17.1 to 20.7) | 210 | 1923 | 19.2 (16.7 to 22.0) | 223 | 1827 | 18.0 (15.5 to 20.9) | 40 | 376 | 21.6 (15.9 to 28.6) | .4765 | .2921 |

| Few times pe mo , % | 478 | 4327 | 19.8 (17.9 to 21.8) | 220 | 2228 | 21.3 (18.3 to 24.7) | 228 | 1862 | 19.2 (16.7 to 22.1) | 30 | 237 | 14.4 (10.0 to 20.3) | .0411 | .1325 |

| ≤once per mo, % | 607 | 5219 | 23.7 (21.8 to 25.7) | 250 | 2480 | 23.1 (20.1 to 26.4) | 294 | 2228 | 23.1 (20.5 to 26.0) | 63 | 511 | 31.5 (24.8 to 39.0) | .0279 | .0234 |

Use of cannabis during and after cancer treatment

Among the sample of respondents who reported initiating treatment (96%) and using cannabis since cancer diagnosis, a weighted 72.1% reported using it during treatment, and 41.0% reported using it daily (Table 5). A greater percentage of patients who resided in states where cannabis was fully legal and where it was medically legal used cannabis during treatment than in states where cannabis was fully illegal (74.5% and 70.5%, respectively, vs 61.3%; P < .01). There were no differences in frequency of cannabis use during treatment by state cannabis policies. Approximately 76% of the sample of respondents had completed treatment, and among those, a weighted 78.7% reported using cannabis after treatment. No differences were observed in use of cannabis after completion of treatment by state cannabis policies governing use. However, a greater percentage of respondents continued to use cannabis a few times a month after treatment in states where it was fully legal than in states where it was fully illegal (21.3% vs 14.4%; P = .04). Conversely, a greater percentage of respondents in states where cannabis was fully illegal continued to use cannabis less than once per month than in states where cannabis was fully legal or legal for medical use (P = .02).

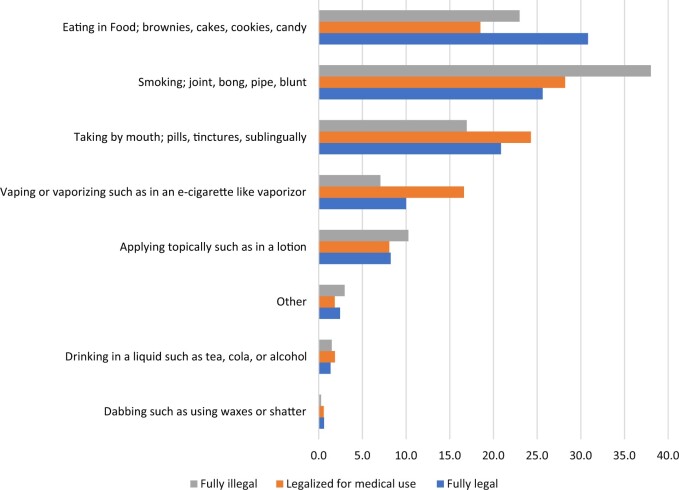

Modes of cannabis use

The modes of cannabis used among cancer patients since cancer diagnosis are shown in Figure 4. Patients reported eating in food, such as brownies, cakes, cookies, and candy; smoking in a joint; bong, pipe, or blunt; and taking by mouth by pills, tinctures, or sublingually as most frequent modes of using cannabis. Whereas eating in food was the most frequent mode of use among cancer patients who resided in states where cannabis was fully legal (30.8%), smoking was the most frequent mode of use among patients in states where cannabis was legalized for medical use (28.2%) and fully illegal (38.0%). Cannabis use since cancer diagnosis did not vary substantially by cancer site for males and females; however, the mode of use varied by sex where smoking was the most frequent mode of use among male prostate (37.8%), lung (36.0%), melanoma (33.3%), and lymphoma (33.7%) patients (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Eating in food was the most frequent mode of use among female breast (22.7%), melanoma (31.3%), and lymphoma (26.4%) patients, and taking by mouth was the most frequent mode of use by female lung cancer patients.

Figure 4.

Mode of cannabis used most often by state cannabis policy.

Reasons for using cannabis

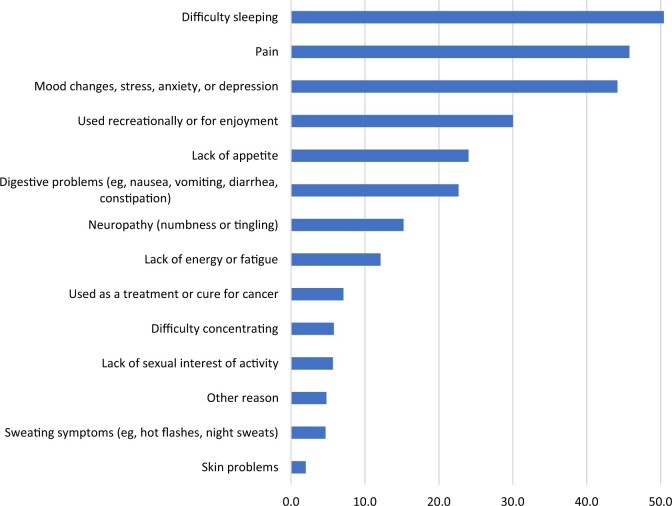

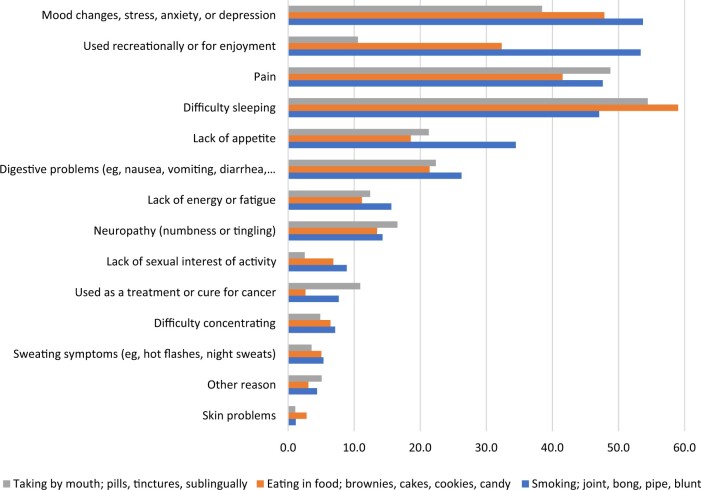

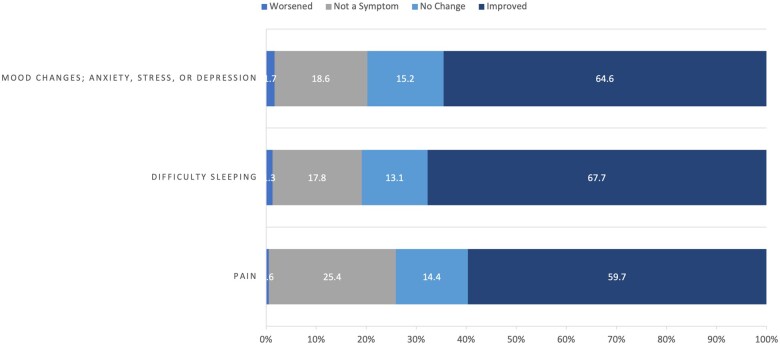

The most frequent reasons cancer patients reported using cannabis since diagnosis, ordered by frequency, was for difficulty sleeping; pain; mood changes; stress, anxiety, or depression; and recreation or enjoyment (Figure 5). Although difficulty sleeping remained the most frequently cited reason for using cannabis among patients who ate cannabis in food or took it by mouth, when stratified by mode of cannabis use, cancer patients who smoked by joint, bong, pipe, or blunt reported mood changes; stress, anxiety, or depression; and recreation or enjoyment as the main reasons for using cannabis (Figure 6). Taking pills, tinctures, or sublingually by mouth was the most common mode of use for pain, and eating in food was the most common mode for difficulty sleeping. Regardless of mode of use, 59.7%-67.7% of cancer patients reported improvement in symptoms related to pain, difficulty sleeping, and mood resulting from their use of cannabis since diagnosis (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Reasons for use among cancer patients who used cannabis since diagnosis (n = 4163).

Figure 6.

Reasons for using cannabis since diagnosis by most common modes of use (n = 4163).

Figure 7.

Perceived impact on symptoms among cancer patients who used cannabis since diagnosis of cancer (n = 4163).

Discussion

In this large descriptive study of more than 12 000 cancer patients who were undergoing cancer treatment or had recently completed cancer treatment, we determined the prevalence and patterns of cannabis use in geographically and demographically diverse catchment areas of 12 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers in states with varying cannabis legal landscapes. We observed that close to one-third of cancer patients used cannabis since their cancer diagnosis, and 60% (or 20% of the sample) reported current use of cannabis. Most patients who used cannabis since cancer diagnosis had used it prior to diagnosis, with 6% of patients reporting use of cannabis after diagnosis without having used it previously. Overall, the reported use of cannabis following the diagnosis of cancer is consistent with prior surveys (10,16,17). The reported use in surveys must be interpreted with caution because of possible selection bias among respondents agreeing to complete the survey, particularly in states where cannabis use is illegal.

Of note, the reported use of cannabis since diagnosis only varied slightly by legal status, among the 10 sites with probability samples, with the percentage of use being higher among patients who resided in states where cannabis was fully legal (34.3%) or legalized for medical use (31.5%) than in states where cannabis was fully illegal (24.7%) (data not shown). However, among those who reported cannabis use, current reported use was lower among patients residing in states where cannabis is fully illegal (50%) than in states with legal use (59%-62.7% current use) (Table 5). The lower overall reported use and current use suggests that the state’s legal cannabis context may influence patients’ decisions regarding cannabis use and is consistent with findings in the general population where the prevalence of cannabis use varies by state legalization status (18).

We also observed that cancer patients primarily ate cannabis in food, smoked it, or took it by mouth in the form of pill, tinctures, or sublingually rather than other forms such as vaping and in lotions. These responses are similar to results of other surveys where cancer patients used edibles most often (14). Among a group of patients having any approved condition seeking certification for medical cannabis in Michigan, smoking as the mode of use was reported less frequently among cancer patients than those without cancer (19), consistent with the overall results of our survey. Mode of use varied by legal status where, interestingly, smoking was the most frequent mode among patients residing in states where cannabis was either illegal or legalized only for medical use, while eating in food was the most common mode where cannabis was fully legal. Available evidence is limited on adverse health risks associated with mode of delivery, but inhalation of smoked cannabis raises concern about other exposures and harms related to respiratory outcomes (20). Interestingly, 36% of male and 20% of female lung cancer respondents reported smoking cannabis. There could be a preference for smoking cannabis among those who smoked cigarettes (21), and lung cancer patients, who may be current or former cigarette smokers, may prefer smoked cannabis. Although smoked cannabis can lead to exposure to carcinogenic combustion products, whether it increases risk to respiratory cancers as cigarette smoking does remain an open question (20,22).

Consistent with other surveys (8,14,23-25), cancer patients in our survey used cannabis primarily for symptom relief, including difficulty sleeping, pain, and mood changes. However, close to 30% reported using it recreationally or for enjoyment, likely reflecting the use of cannabis among cancer patients before cancer diagnosis.

In general, cancer patients perceived that the benefits of using cannabis outweighed the risks. Benefits noted were consistent across legal status. Patients in states where cannabis use is illegal noted the associated legal risks with use. Among patients residing in fully illegal cannabis states, perceived risks were greater and specifically related to associated legal risks and addiction to cannabis. These risks may also be shared by providers in those states and contribute to stigma associated with cannabis use, which could adversely affect patient-provider relationships. Whether these perceived risks and benefits related to use during cancer treatment reflect actual benefits and harms requires further extensive investigation, preferably in the context of randomized trials.

Of concern is the lack of conversation with health-care providers about cannabis use despite patients stating they would feel comfortable discussing its use. Though most of the patients, regardless of legal status, reported they were comfortable communicating use with providers about cannabis, much fewer reported having the discussion. In addition, those patients residing in states with illegal cannabis status were less likely to discuss cannabis use with their providers. Given the increasing availability of cannabis, it is important to have open communication between patient and providers, particularly because there may be harmful treatment interactions. For example, some studies have observed decreased responses and overall survival among patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (7) and immunotherapy (26-28). At least 1 clinical study has shown similar tumor progression among cannabis-treated and cannabis-naïve non–small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (29). More broadly, there is evidence of potential drug interactions with cannabis, suggesting that health-care providers should monitor responses of cannabis users, especially those with chronic conditions (30).

The low overall response rate across cancer centers is a limitation of the survey, and selection bias must be considered in interpreting results. Moreover, response rates varied markedly across states regardless of legal statuses. Although the reported use was consistent with other smaller surveys, given the potential sensitivity of the subject, particularly in states where cannabis use is illegal, and despite most surveys being conducted anonymously, it is difficult to know whether users of cannabis were more or less likely than never users to respond. Moreover, cancer patients treated at NCI-Designated Cancer Centers are not representative of the US population of cancer patients given that most patients receive treatment at other cancer treatment facilities. Although the legal landscape for cannabis use is changing, state legalization status was fixed at the time of survey administration, particularly for medical use, and was consistent over the period since diagnosis and the reference time for the survey. Although a limitation of the survey, we don’t believe changes in adult nonmedical cannabis laws during survey administration had an impact on cannabis use since diagnosis. Given the low response rate for patients in cancer centers, representation of cancer center catchment areas is dubious. Thus, overall estimates should be interpreted with caution and estimates of prevalence are questionable.

This large geographically diverse survey demonstrates that patients are using cannabis regardless of its legality in their state of residence. The use of cannabis is likely to increase given liberalization of legal status along with the perception of benefits. Thus, it is critical to address the knowledge gaps and determine actual benefits and harms of cannabis use during cancer treatment, particularly assessing any potential treatment interactions, and to enhance patient-provider communication. Future research should assess actual benefits and risks of using cannabis among cancer patients undergoing treatment in controlled clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the ICF team for providing support for the development of the survey core questionnaire, statistical data analysis and weighted estimates, and meeting management and coordination. ICF team members listed in alphabetical order: Emily Beltran, Nancy Byrne, Sarah Field, Andrew Fitzgerald, Lee Harding (former ICF Team member), Yun Kim (co-author), Deirdre Middleton (former ICF Team member), Zoe Padgett (former ICF Team member), and Danny Sengphilom.

This article appears as part of the monograph “Use of Cannabis Among Cancer Patients.” This issue was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. The opinions expressed by the authors are their own, and this material should not be interpreted as representing the official viewpoint of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Cancer Institute.

Contributor Information

Gary L Ellison, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kathy J Helzlsouer, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Sonia M Rosenfield, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Yun Kim, ICF, Rockville, MD, USA.

Rebecca L Ashare, Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Department of Psychology, University of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA.

Anne H Blaes, Division of Hematology, Oncology, and Transplantation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Jennifer Cullen, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cleveland, OH, USA; Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Neal Doran, University of California, San Diego, Health Moores Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA; Psychology Service, Jennifer Moreno Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Diego, CA, USA.

Jon O Ebbert, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA.

Kathleen M Egan, Department of Cancer Epidemiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA.

Jaimee L Heffner, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Richard T Lee, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cleveland, OH, USA; City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA, USA.

Erin A McClure, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA; Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Corinne McDaniels-Davidson, University of California, San Diego, Health Moores Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA, USA; Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Science, School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA.

Salimah H Meghani, Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Department of Biobehavioral Health Sciences, NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Polly A Newcomb, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Shannon Nugent, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Nicholas Hernandez-Ortega, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Health System, Miami, FL, USA; School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA.

Talya Salz, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Denise C Vidot, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Health System, Miami, FL, USA; School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA.

Brooke Worster, Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Dylan M Zylla, The Cancer Research Center, HealthPartners and Park Nicollet, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Data availability

All data included in this effort are de-identified and do not include identifying information for any respondents. De-identified data for all but three of the Cancer Centers will be made available in the Database for Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) (https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/aa/wga.cgi?page=login), an NIH controlled-access repository; the title of this publication should be used to search for this dataset in dbGaP. Requests for the data from Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina should be sent to Dr. Erin McClure (mccluree@musc.edu). Contact Dr. Brooke Worster (Brooke.Worster@jefferson.edu) for requests to data collected by Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Jefferson Health. For requests to data collected by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, contact Dr. Rebecca Ashare (crdatashare@mskcc.org).

Author contributions

Gary L. Ellison, PhD, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Kathy J. Helzlsouer, MD, MHS (Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Sonia Rosenfield, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Yun Kim, MPH (Data curation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Rebecca L. Ashare, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Anne H. Blaes, MD, MS (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Jennifer Cullen, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Neal Doran, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Jon O. Ebbert, MD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Kathleen M. Egan, ScD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Jaimee L. Heffner, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Richard T. Lee, MD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Erin A. McClure, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Corinne McDaniels-Davidson, PhD, MPH (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Salimah H. Meghani, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Polly A. Newcomb, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Shannon Nugent, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Nicholas Hernandez-Ortega, MPH (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Talya Salz, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Denise C. Vidot, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Brooke Worster, MD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), and Dylan M. Zylla, MD, MS (Data curation; Writing—review & editing).

Funding

Funding for the conduct of the surveys was provided through supplemental grant awards to 12 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers: P30CA016520; P30CA043703; P30CA015704; P30CA240139; P30CA077598; P30CA015083; P30CA008748; P30CA138313; P30CA076292; P30CA023100; P30CA069533; P30CA056036.

Monograph sponsorship

This article appears as part of the monograph “Cannabis Use Among Cancer Survivors,” sponsored by the National Cancer Institute.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Jon O. Ebbert has consulting agreements with K Health, Exact Sciences, and MedinCell and serves on the scientific advisory board for Applied Aerosol Technologies, which are not related to the current work.

References

- 1. Crocq MA. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2020;22(3):223-228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/mcrocq [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reynolds JR. Therapeutical uses and toxic effects of cannabis indica. Lancet. 1890;135(3473):637-638. [Google Scholar]

- 3. DEA. Drug Scheduling. 10 July 2018. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling. Accessed November 8, 2023.

- 4. Ellison GL, Alejandro Salicrup L, Freedman AN, et al. The National Cancer Institute and Cannabis and Cannabinoids Research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2021;2021(58):35-38. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgab014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NCoS Legislatures. State Medical Cannabis Laws. https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-medical-cannabis-laws. Accessed November 8, 2023.

- 6.ProCon.org. Legal Medical and Recreational Marijuana States. https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/legal-medical-marijuana-states-and-dc/. Accessed November 8, 2023.

- 7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017:486. 10.17226/24625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blake EA, Ross M, Ihenacho U, et al. Non-prescription cannabis use for symptom management amongst women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;30:100497. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2019.100497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macari DM, Gbadamosi B, Jaiyesimi I, Gaikazian S. Medical cannabis in cancer patients: a survey of a community hematology oncology population. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(9):636-639. doi: 10.1097/coc.0000000000000718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, et al. Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4488-4497. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saadeh CE, Rustem DR. Medical marijuana use in a community cancer center. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(9):e566-e578. doi: 10.1200/jop.18.00057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weiss MC, Hibbs JE, Buckley ME, et al. A Coala-T-Cannabis Survey Study of breast cancer patients’ use of cannabis before, during, and after treatment. Cancer. 2022;128(1):160-168. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson MM, Masterson E, Broglio K. Cannabis use among patients in a rural academic palliative care clinic. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(10):1224-1226. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azizoddin DR, Cohn AM, Ulahannan SV, et al. Cannabis use among adults undergoing cancer treatment. Cancer. 2023;129(21):3498-3508. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program NCI. Cannabis Core Measures Questionnaire. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/cannabis/CoreMeasuresQuestionnaire.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2023.

- 16. McClure EA, Walters KJ, Tomko RL, Dahne J, Hill EG, McRae-Clark AL. Cannabis use prevalence, patterns, and reasons for use among patients with cancer and survivors in a state without legal cannabis access. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(7):429. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07881-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tringale KR, Huynh-Le MP, Salans M, Marshall DC, Shi Y, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. The role of cancer in marijuana and prescription opioid use in the United States: a population-based analysis from 2005 to 2014. Cancer. Jul.1 2019;125(13):2242-2251. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Steigerwald S, Cohen BE, Vali M, Hasin D, Cerda M, Keyhani S. Differences in opinions about marijuana use and prevalence of use by state legalization status. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):337-344. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cousins MM, Jannausch M, Jagsi R, Ilgen M. Differences between cancer patients and others who use medicinal Cannabis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vásconez-González J, Delgado-Moreira K, López-Molina B, Izquierdo-Condoy JS, Gámez-Rivera E, Ortiz-Prado E. Effects of smoking marijuana on the respiratory system: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2023;44(3):249-260. doi: 10.1177/08897077231186228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith DM, Hyland A, Kozlowski L, O’Connor RJ, Collins RL. Use of inhaled nicotine and cannabis products among adults who vape both substances. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(3):432-441. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.2019773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):239-247. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson SP, Zylla DM, McGriff DM, Arneson TJ. Impact of medical cannabis on patient-reported symptoms for patients with cancer enrolled in Minnesota’s Medical Cannabis Program. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(4):e338-e345. doi: 10.1200/jop.18.00562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poghosyan H, Noonan EJ, Badri P, Braun I, Young GJ. Association between daily and non-daily cannabis use and depression among United States adult cancer survivors. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69(4):672-685. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vinette B, Côté J, El-Akhras A, Mrad H, Chicoine G, Bilodeau K. Routes of administration, reasons for use, and approved indications of medical cannabis in oncology: a scoping review. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09378-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bar-Sela GIL, Cohen I, Campisi-Pinto S, et al. Correction: Bar-Sela et al. Cannabis Consumption Used by Cancer Patients during Immunotherapy Correlates with Poor Clinical Outcome. Cancers 2020, 12, 2447. Cancers. 2022;14(8):1957. doi:. 10.3390/cancers14081957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, Wollner M, Peer A, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis impacts tumor response rate to nivolumab in patients with advanced malignancies. Oncologist. 2019;24(4):549-554. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. To J, Davis M, Sbrana A, et al. MASCC guideline: cannabis for cancer-related pain and risk of harms and adverse events. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(4):202. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07662-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waissengrin B, Leshem Y, Taya M, et al. The use of medical cannabis concomitantly with immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: A sigh of relief?. Eur J Cancer. 2023;180:52-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alsherbiny M, Li C. Medicinal cannabis—potential drug interactions. Medicines. 2018;6(1):3. doi: 10.3390/medicines6010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this effort are de-identified and do not include identifying information for any respondents. De-identified data for all but three of the Cancer Centers will be made available in the Database for Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) (https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/aa/wga.cgi?page=login), an NIH controlled-access repository; the title of this publication should be used to search for this dataset in dbGaP. Requests for the data from Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina should be sent to Dr. Erin McClure (mccluree@musc.edu). Contact Dr. Brooke Worster (Brooke.Worster@jefferson.edu) for requests to data collected by Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Jefferson Health. For requests to data collected by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, contact Dr. Rebecca Ashare (crdatashare@mskcc.org).