Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a rising health concern worldwide. As an indicator organism, E. coli, specifically extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli, can be used to detect AMR in the environment and estimate the risk of transmitting resistance among humans, animals and the environment. This study focused on detecting cefotaxime resistant E. coli in floor swab samples from 49 households in rural villages in Bangladesh. Following isolation of cefotaxime resistant E. coli, DNA extracted from isolates was subjected to molecular characterization for virulence and resistance genes, determination of resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics to define multidrug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug resistant (XDR) strains, and the biofilm forming capacity of the isolates. Among 49 households, floor swabs from 35 (71 %) households tested positive for cefotaxime resistant E. coli. Notably, all of the 91 representative isolates were ESBL producers, with the majority (84.6 %) containing the blaCTX-M gene, followed by the blaTEM and blaSHV genes detected in 22.0 % and 6.6 % of the isolates, respectively. All isolates were MDR, and one isolate was XDR. In terms of pathogenic strains, 8.8 % of the isolates were diarrheagenic and 5.5 % were extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC). At 25 °C, 45 % of the isolates formed strong biofilm, whereas 43 % and 12 % formed moderate and weak biofilm, respectively. On the other hand, at 37 °C, 1.1 %, 4.4 % and 93.4 % of the isolates were strong, moderate and weak biofilm formers, respectively, and 1.1 % showed no biofilm formation. The study emphasizes the importance of screening and characterizing cefotaxime resistant E. coli from household floors in a developing country setting to understand AMR exposure associated with floors.

Keywords: AMR, MDR, XDR, ESBL E. coli, Resistance genes, Virulence genes, Household floors, Biofilm

1. Introduction

The rising trend of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacterial pathogens has become a worldwide health concern, significantly raising the mortality and morbidity rate of microbial infections [1]. Competition for resources among microorganisms and the production of secondary metabolites to enhance survival, fueled by the acquisition of resistance through horizontally transferring genes within neighboring bacterial populations, results in both established and emerging mechanisms of resistance among bacteria [2]. The resultant multidrug resistant patterns in bacteria lead to infections that are difficult to treat with existing third generation antimicrobials, posing severe global health concerns.

Escherichia coli, a common resident within warm-blooded animals’ gastrointestinal tract, is the most widely utilized fecal indicator organism worldwide to assess contamination in environmental compartments [3]. E. coli has also been classified as one of the organisms most commonly involved in horizontally transferring antibiotic resistance genes, therefore playing a significant part in the emergence and spread of AMR [4]. AMR E. coli can serve as a suitable indicator to detect and quantify AMR in the environment, assess how anthropogenic activities affect AMR in specific environmental compartments and estimate the risk of transmission between the environment, humans and animals/livestock [5]. Specifically, extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli is employed in national and international AMR surveillance programs, as per WHO recommendations [6]. Although most E. coli strains coexist with their human host with mutual benefits, six pathogenic strains are often associated with food-borne infections in humans [7]. Other pathotypes of E. coli responsible for extraintestinal infections have been termed extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC). Studies suggest that ExPEC is the leading cause of adult bacteremia, the second leading cause of neonatal meningitis (meningitis-associated E. coli, MNEC) and is responsible for the vast majority of urinary tract infections (uropathogenic E. coli, UPEC) [8]. A study demonstrated that the severity of sepsis induced by ESBL ExPEC is three times higher than β-lactam resistant E. coli strains [9].

In settings where human/animal fecal waste is not isolated from the environment, antimicrobial resistant organisms can be transmitted to new hosts from feces via multiple environmental compartments [10]. Among these compartments, soil may be a particularly important reservoir. Domestic animal ownership, open defecation, poor sanitation practices and the presence of animal fecal waste have been associated with E. coli contamination of soil [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]], and levels of contamination within household interiors can be extensive in developing countries [13,16,17]. In rural areas of developing countries like Bangladesh, household floors are frequently made of soil and can mediate direct contact of residents with contaminated soil. A recent study in rural Bangladesh that collected front yard soil detected multidrug resistant E. coli in 12.6 % of samples and potentially pathogenic E. coli in 10 % of samples [12]. The persistence of AMR E. coli in domestic environments is a threat because the organism produces filamentous structures from the cell surface that help it adhere to surfaces [5]. AMR in soil is particularly concerning because contaminated soil in turn can contaminate hands and objects in the home and soil can also be ingested deliberately (geophagia) or as dust [11,[13], [14], [15],18].

The WHO has long highlighted that in order to estimate AMR threat to animal and human health, a multi-sectoral “One-Health” approach to AMR surveillance is required [1]. Considering the suitability of E. coli to assess the burden of AMR and microbial contamination in household settings, this study focused on detecting and isolating cefotaxime resistant E. coli from household floors in rural Bangladesh to assess their multidrug resistance profiles, presence of pathogenic and resistance genes, correlation among phenotypic and genotypic traits, as well as their biofilm forming capacity. Cefotaxime has been proposed to be a cost-efficient alternative for detecting presumptive ESBL E. coli which may confer resistance to antibiotics from multiple classes [19], hence this antibiotic was utilized for assessing β-lactamase producing capability.

2. Results

2.1. Enumeration of cefotaxime resistant E. coli through MPN method

Out of the 49 households in our study, floor swabs from 35 (71 %) households were positive for cefotaxime resistant E. coli based on the detection of fluorescent cells from the Quanti-Tray/2000 system supplemented with cefotaxime solution. The counts of cefotaxime resistant E. coli per positive household are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The geometric mean of cefotaxime resistant isolates across the 35 positive households was >3.6 × 103 MPN per 100 ml of floor swab elution. Cefotaxime resistant E. coli counts ranged from 10 MPN/100 mL floor swab elution (observed among five households) to above the upper detection limit of 24,196 MPN/100 mL floor swab elution (observed among three households).

2.2. ESBL genes were predominant among cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates

The representative isolates obtained were already presumptive ESBL producers considering their resistance to cefotaxime in the modified IDEXX assay supplemented with cefotaxime. Further molecular assessment showed that a high percentage of the commonly distributed ESBL genes were present within the isolates. The distribution of the detected β-lactamase genes and the percentage of isolates harboring different combinations of ESBL genes are demonstrated in Table 1. Among the 91 isolates, 84 (92.3 %) could be classified within the three most common ESBL producing genes, including 77 (84.6 %) positive for blaCTX-M, 20 (22 %) for blaTEM, and 6 (6.6 %) for blaSHV. Among these, 14 isolates (15.4 %) were positive for both blaCTX-M and blaTEM, and 3 (3.3 %) for all three genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM and blaSHV). No isolates were positive for blaOXA.

Table 1.

Distribution of β-lactamase genes among E. coli isolates.

| ESBL genes and combinations | Percentage of isolates |

|---|---|

| CTX-M | 84.6 % (77/91) |

| TEM | 22.0 % (20/91) |

| SHV | 6.6 % (6/91) |

| OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| CTX-M and TEM | 15.4 % (14/91) |

| CTX-M and SHV | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| CTX-M and OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| TEM and SHV | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| TEM and OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| SHV and OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| CTX-M, TEM and SHV | 3.3 % (3/91) |

| TEM, SHV and OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| SHV, OXA and CTX-M | 0.0 % (0/91) |

| CTX-M, TEM, SHV and OXA | 0.0 % (0/91) |

2.3. Highly-drug resistant E. coli strains present in the soil swabs

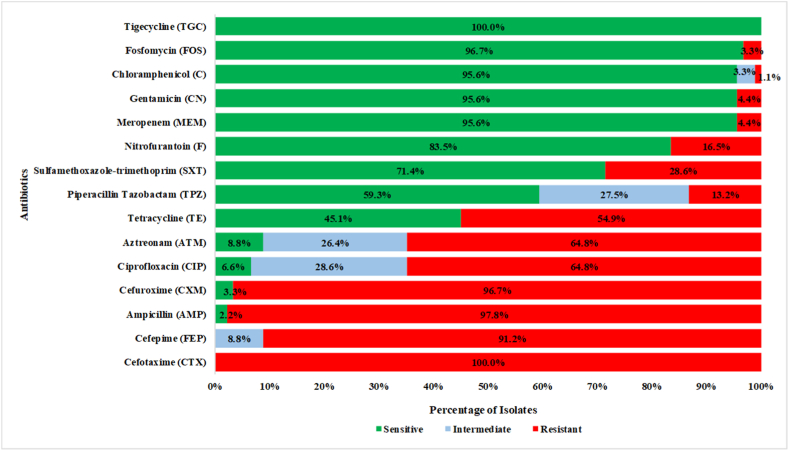

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion assay demonstrated that the majority of the 91 isolates were resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics based on CLSI and EUCAST guidelines. Among the 15 tested antibiotics, 91/91 (100 %) of the isolates were susceptible to tigecycline and resistant to cefotaxime. For the remaining 13 antibiotics, the majority of the isolates were resistant to the following three antibiotics: 89/91 (97.8 %) to ampicillin, 88/91 (96.7 %) to cefuroxime, and 83/91 (91.2 %) to cefepime. On the other hand, the majority of the isolates were sensitive to four antibiotics: 88/91 (96.7 %) to fosfomycin, 87/91 (95.6 %) to chloramphenicol, 87/91 (95.6 %) to gentamicin, and 87/91 (95.6 %) to meropenem. All isolates were multidrug resistant (resistant to ≥ 3 antimicrobial categories) [[20], [21], [22], [23]], and one isolate was extensively drug resistant (XDR) (resistant to ≥ 12 antimicrobial classes) [24]. The percentage of resistance among the isolates is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Multiple-drug resistance profile of E. coli isolates. Considering the selective pressure induced by cefotaxime-addition in the modified-IDEXX assay, all the isolates showed phenotypic resistance to cefotaxime. Majority of the isolates showed resistance to three other antibiotics, cefepime, ampicillin, and cefuroxime. On the other hand, a number of isolates showed sensitivity to tigecycline, fosfomycin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and meropenem.

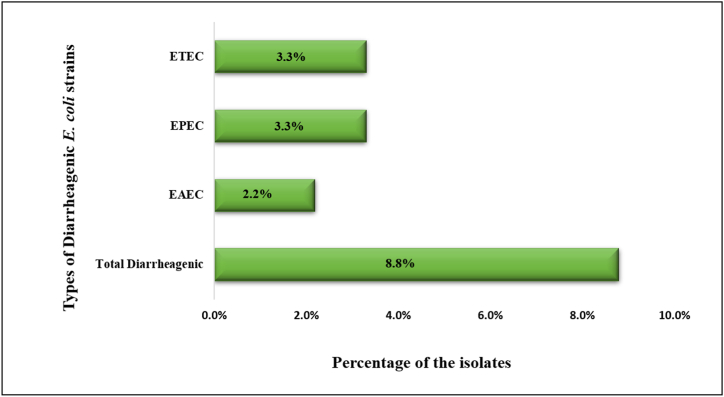

2.4. Diarrheagenic E. coli were prevalent on household floors

Screening of cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates for intestinal pathogenic genes showed that 8/91 isolates (8.8 %) appeared to be diarrheagenic. Among those, two isolates (2.2 %) were identified as EAEC and positive for both aaiC and aat genes; three isolates (3.3 %) were identified as EPEC and positive for both bfpA and eae genes; three isolates (3.3 %) were identified as ETEC and positive for eltB gene. None of the isolates were positive for eltB, iaa, ipaH, stx1, and stx2 genes. The percentage of diarrheagenic isolates is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Classification of the diarrheagenic E. coli isolates. No EHEC and EIEC were found among the isolates. Among the persistent types of diarrheagenic isolates, ETEC and EPEC were more prevalent.

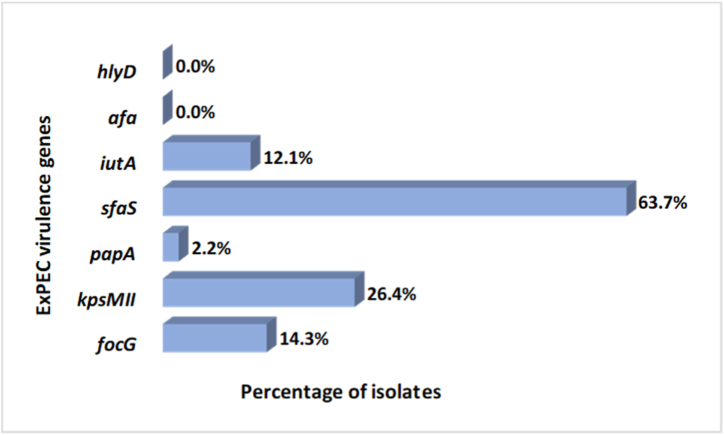

2.5. Cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates with ExPEC genes

A high prevalence of ExPEC genes was detected among the cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates. Five out of the seven targeted genes were detected, including focG, kpsMII, sfaS, papA and iutA genes. The characteristics of the ExPEC genes among the isolates are depicted in Fig. 3. Out of the 91 isolates, 77 isolates (84.6 %) were positive for at least one ExPEC gene, 21 isolates (23.1 %) for at least two genes and 5 isolates (5.5 %) for at least 3 genes. Notably, 13 isolates (14.3 %) were positive for focG, 24 (26.4 %) were positive for kpsMII, 2 (2.2 %) for papA, 58 (63.7 %) for sfaS, and 11 isolates (12.1 %) were positive for iutA. None of the isolates were positive for afa and hlyD.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of ExPEC genes among E. coli isolates. Predominantly, sfaS gene was present among the isolates, followed by kpsMII gene. None of the isolates contained hlyD and afa genes.

Different combinations of genes were detected amongst the isolates (Table 2). A total of 21 isolates demonstrated the presence of two different genes. Of these, 4 isolates (4.4 %) were positive for both sfaS and iutA, 4 isolates (4.4 %) were positive for both focG and sfaS, 4 isolates (4.4 %) were positive for both iutA and kpsMII, 9 isolates (9.9 %) were positive for both kpsMII and sfaS. Similarly, 2 isolates (2.2 %) were positive for kpsMII, focG and sfaS, 2 isolates (2.2 %) were positive for kpsMII, papA and iutA, and 1 isolate was positive for focG, iutA, and sfaS. If an E. coli isolate harbors at least three ExPEC genes, then it is classified as an extraintestinal pathogen or ExPEC strain [25]. According to these criteria, 5 isolates (5.5 %) were ExPEC strains among the 91 isolates.

Table 2.

Combinations of ExPEC genes among the cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates.

| Number of ExPEC genes | Combinations of ExPEC genes | Percentage of E. coli isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Two genes | sfaS + iutA | 4.4 % (4/91) |

| focG + sfaS | 4.4 % (4/91) | |

| kpsMII + sfaS | 9.9 % (9/91) | |

| kpsMII + iutA | 4.4 % (4/91) | |

| Three genes | kpsMII + papA + iutA | 2.2 % (2/91) |

| focG + kpsMII + sfaS | 2.2 % (2/91) | |

| focG + iutA + sfaS | 1.1 % (1/91) |

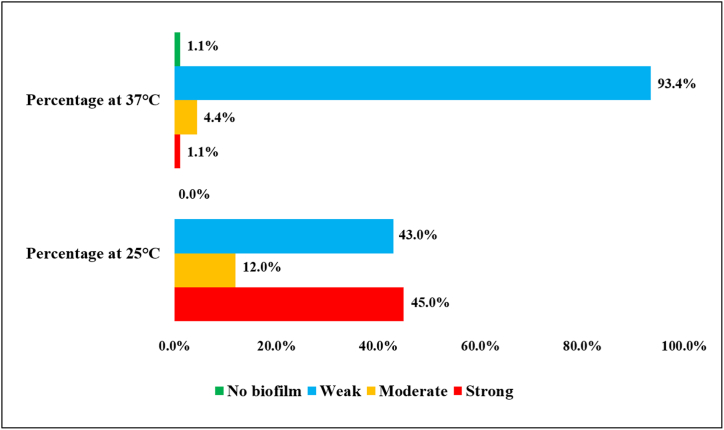

2.6. Biofilm formation ability of cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates

Higher biofilm formation was observed at 25 °C compared to 37 °C. The percentage of isolates demonstrating variable strength of biofilm formation at different incubation temperatures is depicted in Fig. 4. At 25 °C, 41/91 (45 %) of the isolates formed strong biofilm, 39/41 (43 %) formed moderate biofilm, and 11/41 (12 %) formed weak biofilm. On the other hand, at 37 °C, a very low percentage of isolates showed a biofilm forming tendency. At this temperature, 1/91 (1.1 %) of the isolates formed strong biofilm, 4/91 (4.4 %) formed moderate biofilm, 85/91 (93.4 %) formed weak biofilm, and 1/91 (1.1 %) formed no biofilm.

Fig. 4.

Biofilm formation of cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates at 37 °C and 25 °C demonstrates biofilm forming capacity at 25 °C is comparatively higher.

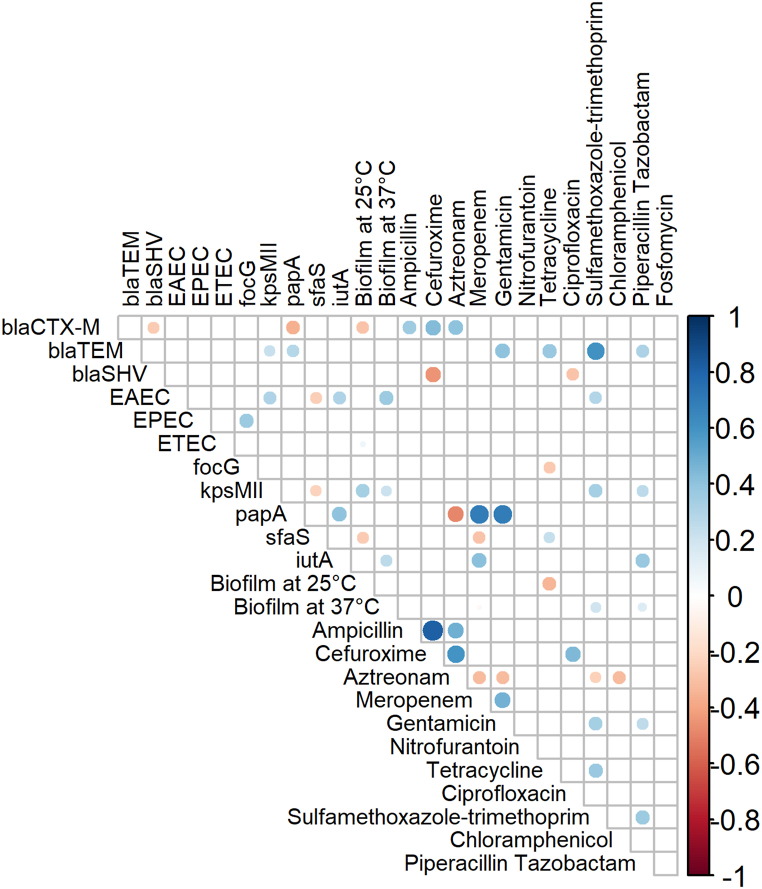

2.7. Correlation between phenotypic and genotypic features

To assess the correlation between the phenotypic attributes (biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance) and genotypic attributes (resistance and virulence genes), a correlation matrix was constructed (Fig. 5). Among the β-lactams, resistance to ampicillin, cefuroxime and aztreonam was positively correlated to the presence of blaCTX-M genes but negatively correlated or non-correlated to the presence of blaSHV and blaTEM genes, respectively. Resistance to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was significantly positively correlated to the presence of blaTEM gene.

Fig. 5.

Correlation matrix of the genotypic (resistance and virulence genes) and the phenotypic (antibiotic resistance profiles and biofilm formation) features demonstrates a significant correlation among the variables. White spaces are non significantly correlated. Blue circles indicate a significant positive correlation and red circles indicate a significant negative correlation. The size and strength of color represent the numerical value of the correlation coefficient. The matrix only demonstrates significant (p < 0.05) associations, as assessed by the Fisher Exact test.

Significant correlations were also detected in resistance amongst multiple antibiotics, which complies with their phenotypic patterns of resistance. Resistance to almost all classes of antibiotics showed some positive correlation with other classes, except chloramphenicol, fosfomycin, tetracycline and nitrofurantoin. Except for one isolate, all other isolates showed similar resistance to ampicillin and cefuroxime, thereby resistance to these two antibiotics showed a significant positive correlation. The presence of the papA gene was strongly correlated with resistance against carbapenems and aminoglycosides. In contrast, the presence of blaSHV and papA genes showed a negative correlation with cefuroxime and aztreonam, respectively. The coexistence of resistance and virulence was also detected within some isolates. In terms of biofilm forming ability, kpsMII, iutA, and EAEC strains showed a significant correlation with biofilm formation at 37 °C. At 25 °C, only kpsMII showed a significant positive correlation, whereas resistance to tetracycline and presence of blaCTX-M and sfas genes showed significant negative correlations with biofilm formation.

3. Discussion

AMR has become a rising concern for the world of health sciences in this century and multiple studies have detected the presence of pathogenic E. coli strains on surfaces and soils inside rural households, as well as on hands and in stored drinking water in lower-income countries [13,16,17,26]. Antimicrobial resistant E. coli has been detected in courtyard soil in Bangladesh, indicating soilborne presence of AMR [12]. In our study in rural Bangladesh, out of 49 households, 35/49 (71 %) of indoor household floors, including both soil and concrete floors, tested positive for cefotaxime resistant E. coli. Our estimate is higher than the 48 % prevelence of ESBL-producing E. coli detected in household and hospital settings in Jordan but lower than the 91 % prevalence reported in a poulty farm environment in the Netherlands [27,28]. Since E. coli is an indicator of fecal contamination, high E. coli prevalence on household floors suggests poor hygiene and sanitation, raising concerns about exposure by household members, especially young children [29]. Moreover, cefotaxime resistant E. coli on floors raises further concerns considering the possibility of horizontally transferring resistance genes to surrounding pathogenic microbial populations [30]. Therefore, surveillance of environmental ESBL E. coli is essential to track dissemination through environmental sources, including soils and household floors.

The presence of antibiotic resistance in E. coli has been mainly correlated to the occurrence of different β-lactamase genes, including mainly the ESBL genes along with some other plasmid-mediated resistance genes [31]. ESBL genes render the isolates resistant to all β-lactam class antibiotics and often to other antibiotic classes as well, causing difficult-to-treat infections that require the application of “last-resort” antibiotics such as carbapenems [[32], [33], [34]]. The majority (84.6 %) of the β-lactamase producers in this study had the blaCTX-M gene, consistent with previous studies demonstrating the high prevalence of this gene among cefotaxime resistant isolates [[35], [36], [37]]. In fact, blaCTX-M is one of the foremost groups of ESBL genes among environmental sources and nosocomial infections, which might be because of the presence of multiple clones of the CTX-M enzyme resulting from the epidemic pattern of dissemination of several mobile genetic elements [35,38]. The high presence of the blaCTX-M gene on household floors, consistent with previous evidence of detection in farming soil [39,40], requires attention and reinstates the necessity to find an efficient solution to contain the spread of the gene among other pathogenic organisms. The second most prominent β-lactamase gene in our study was blaTEM (22.0 %). TEM has been reported to be a common β-lactamase gene in gram-negative organisms, specifically E. coli, and accounts for ampicillin resistance in the Enterobacteriaceae group [41,42]. Since 97.8 % of the isolates in our study were resistant to ampicillin, this might partially be attributed to the presence of blaTEM gene. Another 6.6 % of the isolates were positive for blaSHV and none of the isolates were found to be positive for blaOXA, which is consistent with previous studies showing a lower prevalence of these genes among cefotaxime resistant isolates [37,43,44].

The persistence of MDR E. coli in soil samples has been a major concern in developing countries [12]. The extensive use of antibiotics in vegetable farming and animal production leads to the dissemination of antibiotics in the environment, exacerbating the persistence of resistance among pathogens [[45], [46], [47]]. Two recent studies conducted in Bangladesh and Tanzania have isolated 12.6 % and 10 % MDR E. coli from soil samples collected from household front yards, suggesting soils in residential areas can harbor MDR organisms due to poor sewage disposal or unsafe management of manure [12,48]. A concerning finding is that all isolates in our study were MDR E. coli, and one isolate was XDR as defined by previous studies [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. Exposure to MDR pathogenic strains on floors can lead to difficult-to-treat infections among members of these households, especially children [29]. Moreover, E. coli has been reported to be easily transmitted through aerosol formation [49], which raises further concerns regarding the dissemination of these resistant organisms into the environment and contributing to the rise in resistance among surrounding microbial communities through exerting selective pressure.

Diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) is the primary cause of foodborne infection among all age groups and demographics, with symptoms not only limited to diarrhea but also gastroenteritis, nutrient malabsorption and inflammation [50]. In our study, 8/91 (8.8 %) of the isolates were identified as diarrheagenic strains, raising health concerns for household members, considering the samples were collected from floors within the interior of the households. The virulence genes of these DEC may confer additional benefits for the organism to survive under environmental stress as well as provide an evolutionary advantage compared to other microbial populations in the same environment [51]. Besides, all 8 DEC isolates were resistant to ≥5 of the antibiotics tested, therefore classified as MDR, raising concern regarding the treatment of the infections caused by these isolates using our current clinical arrangements. Although there are studies suggesting that the virulence of the DEC strains does not directly influence the persistence or survival of these strains in the environment [52], both climatic and anthropogenic factors in different ecological niches have to be considered for understanding the actual risk exacerbated by the MDR DEC strains present on household floors.

ExPEC are hypothesized to be opportunistic pathogens. They occupy a niche in human and animal intestines, serving as reservoirs of virulence genes, but are only capable of colonizing the extraintestinal sites of the host, making them the leading cause of adult bacteremia, the second leading cause of neonatal meningitis and the cause of the vast majority of urinary tract infections [8,53]. It is difficult to retrace the origin of ExPEC causing human infections but it is well established that the transmission occurs through various routes including contaminated food or direct contact with domestic animals [53]. Domestic animals were common among households in our study, which may explain the high prevalence (84.6 %) of isolates with at least one ExPEC virulence gene in our study, even though only 5.5 % of isolates were definitively classified as ExPEC due to being positive for at least three virulence genes. Notably, all of the ExPEC strains were resistant to ≥6 of the 15 antibiotics tested. The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in agriculture and veterinary medicine may generate selection pressure for the environmental ExPEC strains and make the treatment of such infections increasingly challenging [54]. It is important to investigate the ecological behavior and antibiotic resistance patterns of ExPEC strains to tackle future economic and public health concerns.

Biofilms are considered hotspots for horizontal gene transfer, with a high potential to transfer resistance genes [55,56]. Soil biofilms are of primary concern since soil is considered a reservoir for different antibiotic resistance genes and is a fundamental part of human or animal lives, establishing a medium for the transmission of resistant pathogens to humans or animals [57]. E. coli is a well-accepted model organism for in vivo studies about biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces because many cell surface components including flagella, type I fimbriae, colonic acid, poly(β-1,6-GlcNAc)], autotransporters and other outer membrane proteins were found in E. coli K-12 strain [[58], [59], [60]]. Besides, E. coli biofilms are the major causative agents for medical-device associated infectivity. For example, UPEC strains have been frequently associated with biofilms formed in the lumen of catheters, where they resist antibiotics and shear stress [61]. Biofilms also assist E. coli in mounting resistance against antibiotics, mostly accredited to putative multidrug resistant pumps, reduced antimicrobial diffusion, and reduced growth rates [[62], [63], [64]]. The extent of biofilm formation is influenced by different physicochemical parameters, as well as by the surrounding microbial communities [65]. The biofilm forming potential of environmental E. coli isolates and factors that contribute to this potential have not been well investigated [66]. In our study, we found that the biofilm forming capacity of cefotaxime-resistant E. coli was higher at 25 °C compared to 37 °C, which is consistent with previous studies [67]. Considering the historical average temperature of Bangladesh being 25.75 °C [68], the majority of the isolates will be capable of inducing biofilm formation within the household indoor environment. Notably, at 25 °C, 4 out of 5 ExPEC isolates and 4 out of 8 DEC isolates showed strong biofilm forming tendency, which is concerning considering the resistance or virulence spreading potential of biofilms.

There are some limitations of this study. Firstly, we conducted PCR for four major ESBL genes, so there might be a chance of underdetection of genes. Secondly, the study findings may not be generalized to other environmental conditions because the survival and distribution of microbes in a tropical environment are significantly different than other environmental conditions. In addition, we did not investigate the isolates for their plasmids. A large amount of antimicrobial resistance in the environment often correlates with resistance-trait plasmids [69], hence plasmid-mediated resistance was left undetected. Finally, our sample size was small and therefore we may have missed associations. However, this study provides insight into the resistance and pathogenesis of E. coli isolates from household floors in a rural low-income country setting and can form a foundation for future studies on AMR transmission via floors.

4. Conclusion

There is a rising concern worldwide regarding the contribution of environmental compartments including hands, surfaces, and soil in transmitting enteric bacteria and antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Our study demonstrates the widespread presence of cefotaxime resistant E. coli on household floors in a rural setting. A considerable percentage of the resistant isolates was diarrheagenic and ExPEC, as determined by molecular confirmation. Notably, all cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates, including the pathogenic isolates, were MDR. Coexistence of virulence and resistance against multiple classes of antibiotics poses a severe threat of “difficult-to-treat” infections. In rural Bangladesh and similar settings, these risks are exacerbated by limited access to healthcare facilities. Future studies should quantify AMR E. coli in different environmental compartments, including household floors, to indicate the extent of fecal contamination and antimicrobial resistance in such settings. Studies focusing on elucidating the fate as well as the origin of these pathogenic organisms are crucial to design preventive steps for controlling exposure and transmission. All these findings will necessitate preventive measures and facilitate interventions for improved sanitation and hygiene practices to improve health among vulnerable populations.

5. Materials and methods

5.1. Swab collection

Floor swab samples were collected from 49 households in villages in Sirajganj district in northwestern Bangladesh, with ethical consent of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). The range of location coordinates of the sampling households are from latitude (24.42133–24.54405) to longitude (89.42954–89.36405) and from latitude (24.47101–24.45911) to longitude (89.28701–89.43716). Households were enrolled if they had a child <2 years old, had either a soil or concrete floor and did not have a recent case of anthrax. Field staff collected one floor swab sample in each household using a sterile Whirl-Pak® PolySponge™ bag pre-hydrated with 10 ml of HiCap™ Neutralizing Broth (Nasco, USA). A sterilized 50 cm × 50 cm stencil was laid next to the head of the bed where the child usually sleeps to mark the floor sampling area, avoiding areas under furniture, mats or carpets. Field staff swabbed the area within the stencil once horizontally and once vertically. Samples were preserved on ice and transported ensuring a temperature between 4 °C and 10 °C to the Laboratory of Environmental Health (LEH), icddr,b, Dhaka [70].

5.2. Swab processing and isolating cefotaxime resistant E. coli

The samples were preserved overnight at 4 °C and processed within 24 h from sampling time. Samples were brought to room temperature before processing. Using a sterile graduated cylinder, 100 ml autoclaved deionized water was added into the Whirl-Pak® Hydrated PolySponge™ Bag containing the sponge. The sponge was massaged from outside for 15 s and then gently swirled for 15 s, followed by decanting the liquid into a sterile Whirl-Pak bag [71]. The process was repeated a total of three times to generate a 300 ml solution. Using a sterile disposable pipette, 10 ml solution was immediately removed from the bottom of the elution bag and added into a fresh Whirlpak containing 90 ml autoclaved deionized water to create a 100 mL final aliquot with 10-fold dilution. This step was repeated to create a second 100 mL aliquot with 100-fold dilution. Colilert-18 media was added to each 100 mL aliquot, and 80 μL of filter-sterilized cefotaxime solution (5 mg/mL) was added after Colilert-18 media was completely dissolved [[72], [73], [74]]. Samples were transferred into Quanti/Tray 2000 and incubated at 35 °C for 22 h [75]. Following incubation, the Quanti/Tray cells with presumptive cefotaxime resistant E. coli were identified as those fluorescing under UV light. The most probable number (MPN) of cefotaxime resistant E. coli was quantified as per the MPN table [76] and reported as MPN/100 ml of the eluted floor swab samples. Up to three fluorescent cells were chosen in random order from individual Quanti/Trays and 100 μL of sample was collected from selected cells after sterilizing the back of the tray using 70 % ethanol. The presumptive E. coli samples from the positive Quanti/Tray cells were streaked on non-selective MacConkey Agar (BD, USA) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colonies appearing pink were confirmed as E. coli. From each plate, one representative isolate was chosen for further analysis, yielding a total of 91 isolates. Each isolate represented one positive Quanti/Tray cell from the eluted swabs. E. coli strain ATCC 25922 was used as a positive control for MacConkey agar. Field blanks, lab blanks, field duplicates and lab replicates were processed for QA/QC.

5.3. Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes

Confirmed cefotaxime-resistant E. coli colonies from MacConkey Agar plates were incubated overnight in 3 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth for enrichment. Following the boiling lysis method, DNA was extracted from the enriched broth [77]. An extraction blank was generated for each batch of DNA extraction. PCR analysis was performed to detect ESBL genes blaSHV, blaOXA, blaTEM and blaCTX-M as per a previously established protocol [67]. Primer sequences for all target genes in the study with their subsequent product sizes are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Positive controls were used from previously conducted studies [77], a no-template control was used as a negative control for PCR, and the extraction blanks were processed along with samples. To detect successful PCR amplification and the presence of the targeted gene, post-PCR amplification confirmation was conducted using agarose gel electrophoresis. The gel was prepared using 1 % agarose with freshly prepared Tris-Borate EDTA (0.5X TBE) buffer. The gels were examined for the presence of bands in desired band size after viewing through the GelDoc Go Imaging System (BIORAD, California, USA) and images were saved for further analysis. The same procedures for QA/QC and post-PCR amplification were executed for all the PCR reactions described below.

5.4. Detecting diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) genes

DNA from the cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates was analyzed by PCR to detect diarrheagenic genes, as per a previously established protocol [77]. A multiplex PCR specific for eight genes was conducted at first targeting ETEC (estA, eltB), EPEC (bfpA, eae), EAEC (aaiC, aat), and EIEC (iaa, ipaH) detection, the genes corresponding to most prevalent E. coli pathotypes. Another simplex PCR was conducted for the stx gene for the detection of EHEC (stx1, stx2). The primer sequences for the corresponding genes and their subsequent product sizes are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

5.5. Detecting ExPEC genes

DNA from the cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates was further screened for detection of seven extraintestinal pathogenicity (ExPEC) associated genes, including focG, kpsMII, papA, sfaS, afa, hlyD and iutA, by multiplex PCR as per an established protocol [77]. The primer sequences for the corresponding genes and their subsequent product sizes are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

5.6. Determination of antibiotic resistance profile

The antimicrobial sensitivity profiling of cefotaxime resistant isolates was characterized following the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [78]. The susceptibility profiles of all the isolates against 15 antibiotics, ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), cefuroxime (CXM, 30 μg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30 μg), cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), aztreonam (ATM, 30 μg), meropenem (MEM, 10 μg), gentamicin (CN, 10 μg), nitrofurantoin (F, 300 μg), tetracycline (TE, 30 μg), tigecycline (TG, 15 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT, 25 μg), chloramphenicol (C, 30 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (TPZ, 110 μg) and fosfomycin (FOS, 200 μg), were established following the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion assay using commercially utilized disks from Thermo Fisher Scientific™ (Waltham, USA). E. coli ATCC 25922 strain was used as a positive control and the procedure was replicated three times. The average diameter of the zone of inhibition (mm) was used to classify isolates as sensitive, intermediate, and resistant as per the CLSI and EUCAST guidelines [78,79].

5.7. Biofilm forming assay

The biofilm forming ability of the cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates was examined by conducting the quantitative adherence assay at both 25 °C and 37 °C [80]. The results of the biofilm containing microtiter plates (OD) were detected at 590 nm wavelength using an ELISA plate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA). The isolates were classified as strong biofilm former, moderate biofilm former, weak biofilm former or non-biofilm former [37].

5.8. Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2019 and R (version 4.3.2) were used for statistical analysis. The presence of resistance and virulence genes was tabulated as a binary variable, 1 depicting the presence of the tested genes and 0 depicting the absence of the tested genes for each set of analyses. For the correlation plot, antibiogram results were also interpreted using the binary format, 1 depicting resistant or intermediate and 0 depicting sensitive isolates. Correlations between the detection of resistance genes, DEC genes, ExPEC genes, phenotypic resistance and biofilm forming tendency were assessed using the ‘cor’ function, and the Fisher exact test was utilized to determine significant (p < 0.05) correlations. In order to visualize correlations between these variables for interpretation, the ‘corrplot’ function was used [81]. The correlation plot excluded those variables to which isolates demonstrated 100 % resistance or sensitivity.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH), grant number R01 HD 108196.

Data availability statement

Data associated with this study have not been deposited into a publicly available repository. Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tahani Tabassum: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation. Md. Sakib Hossain: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Ayse Ercumen: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization. Jade Benjamin-Chung: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Md. Foysal Abedin: Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mahbubur Rahman: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Farjana Jahan: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Munima Haque: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Zahid Hayat Mahmud: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This research study was funded by National Institute of Health (NIH), grant number R01 HD 108196. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of NIH to its research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh and Canada for providing core support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34367.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; 2016. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies J., Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moe C.L., Sobsey M.D., Samsa G.P., Mesolo V. Bacterial indicators of risk of diarrhoeal disease from drinking-water in the Philippines. Bull. World Health Organ. 1991;69:305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaper J.B., Nataro J.P., Mobley H.L.T. Pathogenic escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anjum M.F., Schmitt H., Börjesson S., Berendonk T.U., Donner E., Stehling E.G., Boerlin P., Topp E., Jardine C., Li X. The potential of using E. coli as an indicator for the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the environment. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021;64:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report 2022. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062702

- 7.Nataro J.P., Kaper J.B. Diarrheagenic escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo T.A., Johnson J.R. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:1753–1754. doi: 10.1086/315418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melzer M., Petersen I. Mortality following bacteraemic infection caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli compared to non-ESBL producing E. coli. J. Infect. 2007;55:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Elsas J.D., V Semenov A., Costa R., Trevors J.T. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. ISME J. 2011;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauza V., Ocharo R.M., Nguyen T.H., Guest J.S. Soil ingestion is associated with child diarrhea in an urban slum of Nairobi, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;96:569. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montealegre M.C., Roy S., Böni F., Hossain M.I., Navab-Daneshmand T., Caduff L., Faruque A.S.G., Islam M.A., Julian T.R. Risk factors for detection, survival, and growth of antibiotic-resistant and pathogenic Escherichia coli in household soils in rural Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01978-18. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickering A.J., Julian T.R., Marks S.J., Mattioli M.C., Boehm A.B., Schwab K.J., Davis J. Fecal contamination and diarrheal pathogens on surfaces and in soils among Tanzanian households with and without improved sanitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:5736–5743. doi: 10.1021/es300022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehm A.B., Wang D., Ercumen A., Shea M., Harris A.R., Shanks O.C., Kelty C., Ahmed A., Mahmud Z.H., Arnold B.F. Occurrence of host-associated fecal markers on child hands, household soil, and drinking water in rural Bangladeshi households. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016;3:393–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vujcic J., Ram P.K., Hussain F., Unicomb L., Gope P.S., Abedin J., Mahmud Z.H., Sirajul Islam M., Luby S.P. Toys and toilets: cross‐sectional study using children's toys to evaluate environmental faecal contamination in rural Bangladeshi households with different sanitation facilities and practices. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2014;19:528–536. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Julian T.R., Islam M.A., Pickering A.J., Roy S., Fuhrmeister E.R., Ercumen A., Harris A., Bishai J., Schwab K.J. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from feces, hands, and soils in rural Bangladesh via the Colilert Quanti-Tray System. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:1735–1743. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03214-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattioli M.C., Pickering A.J., Gilsdorf R.J., Davis J., Boehm A.B. Hands and water as vectors of diarrheal pathogens in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:355–363. doi: 10.1021/es303878d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navab-Daneshmand T., Friedrich M.N.D., Gächter M., Montealegre M.C., Mlambo L.S., Nhiwatiwa T., Mosler H.-J., Julian T.R. Escherichia coli contamination across multiple environmental compartments (soil, hands, drinking water, and handwashing water) in urban Harare: correlations and risk factors. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018;98:803. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruden A., Alcalde R.E., Alvarez P.J.J., Ashbolt N., Bischel H., Capiro N.L., Crossette E., Frigon D., Grimes K., Haas C.N. An environmental science and engineering framework for combating antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2018;35:1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterson D.L., Doi Y. Editorial commentary: a step closer to extreme drug resistance (XDR) in gram-negative bacilli. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007:1179–1181. doi: 10.1086/522287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallen A.J., Hidron A.I., Patel J., Srinivasan A. Multidrug resistance among gram-negative pathogens that caused healthcare-associated infections reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2006–2008. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:528–531. doi: 10.1086/652152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Fallon E., Gautam S., D’Agata E.M.C. Colonization with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: prolonged duration and frequent cocolonization. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1375–1381. doi: 10.1086/598194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould I.M. The epidemiology of antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2008;32:S2–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basak S., Singh P., Rajurkar M. Multidrug resistant and extensively drug resistant bacteria: a study. J. Pathog. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4065603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang J., Suh Y.-S., Di D.Y.W., Unno T., Sadowsky M.J., Hur H.-G. Pathogenic Escherichia coli strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the Yeongsan River basin of South Korea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:1128–1136. doi: 10.1021/es303577u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang K.W.K., Millar B.C., Moore J.E. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023;80 doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2023.11387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghanem B., Haddadin R.N. Multiple drug resistance and biocide resistance in Escherichia coli environmental isolates from hospital and household settings. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018;7:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0339-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaak H., van Hoek A.H.A.M., Hamidjaja R.A., van der Plaats R.Q.J., Kerkhof-de Heer L., de Roda Husman A.M., Schets F.M. Distribution, numbers, and diversity of ESBL-producing E. coli in the poultry farm environment. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George C.M., Oldja L., Biswas S., Perin J., Lee G.O., Kosek M., Sack R.B., Ahmed S., Haque R., Parvin T. Geophagy is associated with environmental enteropathy and stunting in children in rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;92:1117. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Global tricycle surveillance ESBL E. coli. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021402

- 31.Furlan J.P.R., Stehling E.G. Multiple sequence types, virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance genes in multidrug-and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli from agricultural and non-agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 2021;288 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sirot D. Extended-spectrum plasmid-mediated β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1995;36:19–34. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.suppl_a.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bush K., Jacoby G.A., Medeiros A.A. A functional classification scheme for beta-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacoby G.A., Medeiros A.A. More extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1697–1704. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bora A., Hazarika N.K., Shukla S.K., Prasad K.N., Sarma J.B., Ahmed G. Prevalence of blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from Northeast India. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2014;57:249. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.134698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan E.R., Aung M.S., Paul S.K., Ahmed S., Haque N., Ahamed F., Sarkar S.R., Roy S., Rahman M.M., Mahmud M.C. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase genes in Bangladesh. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018;24:1568–1579. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moniruzzaman M., Hussain M.T., Ali S., Hossain M., Hossain M.S., Alam M.A.U., Galib F.C., Islam M.T., Paul P., Islam M.S. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from patients and surrounding hospital environments in Bangladesh: a molecular approach for the determination of pathogenicity and resistance. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartmann A., Locatelli A., Amoureux L., Depret G., Jolivet C., Gueneau E., Neuwirth C. Occurrence of CTX-M producing Escherichia coli in soils, cattle, and farm environment in France (Burgundy region) Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:83. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng B., Huang C., Xu H., Guo L., Zhang J., Wang X., Jiang X., Yu X., Jin L., Li X. Occurrence and genomic characterization of ESBL-producing, MCR-1-harboring Escherichia coli in farming soil. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2510. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben Said L., Jouini A., Klibi N., Dziri R., Alonso C.A., Boudabous A., Ben Slama K., Torres C. Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in vegetables, soil and water of the farm environment in Tunisia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;203:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haghighatpanah M., Nejad A.S.M., Mojtahedi A., Amirmozafari N., Zeighami H. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and plasmid-borne blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes among clinical strains of Escherichia coli isolated from patients in the north of Iran. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016;7:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delmani F., Jaran A.S., Al Tarazi Y., Masaadeh H., Zaki O., Irbid T. Characterization of ampicillin resistant gene (blaTEM-1) isolated from E. coli in Northern Jordan. Asian J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2017;7:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lina T.T., Khajanchi B.K., Azmi I.J., Islam M.A., Mahmood B., Akter M., Banik A., Alim R., Navarro A., Perez G. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao L., Tan Y., Zhang X., Hu J., Miao Z., Wei L., Chai T. Emissions of Escherichia coli carrying extended-spectrum β-lactamase resistance from pig farms to the surrounding environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2015;12:4203–4213. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sengeløv G., Agersø Y., Halling-Sørensen B., Baloda S.B., Andersen J.S., Jensen L.B. Bacterial antibiotic resistance levels in Danish farmland as a result of treatment with pig manure slurry. Environ. Int. 2003;28:587–595. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(02)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh F., Duffy B. The culturable soil antibiotic resistome: a community of multi-drug resistant bacteria. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rangasamy K., Athiappan M., Devarajan N., Parray J.A. Emergence of multi drug resistance among soil bacteria exposing to insecticides. Microb. Pathog. 2017;105:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonola V.S., Katakweba A.S., Misinzo G., Matee M.I.N. Occurrence of multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli in chickens, humans, rodents and household soil in Karatu, Northern Tanzania. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1137. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10091137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan W., Chai T.J., Miao Z.M. ERIC-PCR identification of the spread of airborne Escherichia coli in pig houses. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:1446–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leimbach A., Hacker J., Dobrindt U. E. coli as an all-rounder: the thin line between commensalism and pathogenicity. Between Pathog. Commensalism. 2013:3–32. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martínez J.L. Bacterial pathogens: from natural ecosystems to human hosts. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;15:325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naganandhini S., Kennedy Z.J., Uyttendaele M., Balachandar D. Persistence of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strains in various tropical agricultural soils of India. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bélanger L., Garenaux A., Harel J., Boulianne M., Nadeau E., Dozois C.M. Escherichia coli from animal reservoirs as a potential source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011;62:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meena P.R., Priyanka P., Rana A., Raj D., Singh A.P. Alarming level of single or multidrug resistance in poultry environments‐associated extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli pathotypes with potential to affect the One Health. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2022;14:400–411. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abe K., Nomura N., Suzuki S. Biofilms: hot spots of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in aquatic environments, with a focus on a new HGT mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020;96:fiaa031. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michaelis C., Grohmann E. Horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in biofilms. Antibiotics. 2023;12:328. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12020328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu S., Wu Y., Cao B., Huang Q., Cai P. An invisible workforce in soil: the neglected role of soil biofilms in conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;52:2720–2748. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prigent‐Combaret C., Prensier G., Le Thi T.T., Vidal O., Lejeune P., Dorel C. Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli‐producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;2:450–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reisner A., Haagensen J.A.J., Schembri M.A., Zechner E.L., Molin S. Development and maturation of Escherichia coli K‐12 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:933–946. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheikh J., Hicks S., Dall’Agnol M., Phillips A.D., Nataro J.P. Roles for Fis and YafK in biofilm formation by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:983–997. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicolle L.E. Catheter-related urinary tract infection. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:627–639. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nesse L.L., Osland A.M., Asal B., Mo S.S. Evolution of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli biofilm treated with high doses of ciprofloxacin. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1246895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katongole P., Nalubega F., Florence N.C., Asiimwe B., Andia I. Biofilm formation, antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence genes of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from clinical isolates in Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ballén V., Gabasa Y., Ratia C., Sánchez M., Soto S. Correlation between antimicrobial resistance, virulence determinants and biofilm formation ability among extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated in Catalonia, Spain. Front. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.803862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cherif-Antar A., Moussa–Boudjemâa B., Didouh N., Medjahdi K., Mayo B., Flórez A.B. Diversity and biofilm-forming capability of bacteria recovered from stainless steel pipes of a milk-processing dairy plant. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016;96:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma G., Sharma S., Sharma P., Chandola D., Dang S., Gupta S., Gabrani R. Escherichia coli biofilm: development and therapeutic strategies. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016;121:309–319. doi: 10.1111/jam.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fang H., Ataker F., Hedin G., Dornbusch K. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamases among Escherichia coli isolates collected in a Swedish hospital and its associated health care facilities from 2001 to 2006. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:707–712. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01943-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman M.R., Lateh H. Climate change in Bangladesh: a spatio-temporal analysis and simulation of recent temperature and rainfall data using GIS and time series analysis model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017;128:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Munita J.M., Arias C.A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Virulence Mech. Bact. Pathog. 2016:481–511. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahmud Z.H., Shirazi F.F., Hossainey M.R.H., Islam M.I., Ahmed M.A., Nafiz T.N., Imran K.M., Sultana J., Islam M.S., Islam M.A. Presence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance among Escherichia coli strains isolated from human pit sludge. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019;13:195–203. doi: 10.3855/jidc.10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harris A.R., Pickering A.J., Harris M., Doza S., Islam M.S., Unicomb L., Luby S., Davis J., Boehm A.B. Ruminants contribute fecal contamination to the urban household environment in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:4642–4649. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b06282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hornsby G., Ibitoye T.D., Keelara S., Harris A. Validation of a modified IDEXX defined-substrate assay for detection of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in environmental reservoirs. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 2023;25:37–43. doi: 10.1039/d2em00189f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.IDEXX, Colilert*, (n.d.). https://www.idexx.com/en/water/water-products-services/colilert/(accessed January 4, 2024).

- 74.Galvin S., Boyle F., Hickey P., Vellinga A., Morris D., Cormican M. Enumeration and characterization of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli bacteria in effluent from municipal, hospital, and secondary treatment facility sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:4772–4779. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02898-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.IDEXX, Quanti-Tray System, (n.d.) https://www.idexx.com/en/water/water-products-services/quanti-tray-system/(accessed January 4, 2024).

- 76.IDEXX, IDEXX Quanti-Tray ®/2000 MPN Table, n.d https://www.idexx.com/files/qt97mpntable.pdf.

- 77.Hossain M.S., Ali S., Hossain M., Uddin S.Z., Moniruzzaman M., Islam M.R., Shohael A.M., Islam M.S., Ananya T.H., Rahman M.M. ESBL producing Escherichia coli in faecal sludge treatment plants: an invisible threat to public health in Rohingya camps, cox's bazar, Bangladesh, front. Public Health (Lond.) 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.783019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.CLSI . 30th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA: 2020. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.https://www.nih.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CLSI-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 79.EUCAST "The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. 2024. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_5.0_Breakpoint_Table_01.pdf Version 14.0, 2024.

- 80.Nirwati H., Sinanjung K., Fahrunissa F., Wijaya F., Napitupulu S., Hati V.P., Hakim M.S., Meliala A., Aman A.T., Nuryastuti T. BMC Proc., BioMed Central. 2019. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from clinical samples in a tertiary care hospital, Klaten, Indonesia; pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okanda T., Haque A., Koshikawa T., Islam A., Huda Q., Takemura H., Matsumoto T., Nakamura S. Characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in the intensive care unit of the largest tertiary hospital in Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.612020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this study have not been deposited into a publicly available repository. Data will be made available on request.