Abstract

Background and Objectives

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) caused by antibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) is an inflammatory myopathy that has been epidemiologically correlated with previous statin exposure. We characterized in detail a series of 11 young statin-naïve patients experiencing a chronic disease course mimicking a limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. With the hypothesis that HMGCR upregulation may increase immunogenicity and trigger the production of autoantibodies, our aim was to expand pathophysiologic knowledge of this distinct phenotype.

Methods

Clinical and epidemiologic data, autoantibody titers, creatine kinase (CK) levels, response to treatment, muscle imaging, and muscle biopsies were assessed. HMGCR expression in patients' muscle was assessed by incubating sections of affected patients with purified anti-HMGCR+ serum. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) with a special focus on cholesterol biosynthesis–related genes and high-resolution human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing were performed.

Results

Patients, aged 3–25 years and mostly female (90.9%), presented with subacute proximal weakness progressing over many years and high CK levels (>1,000 U/L). Diagnostic delay ranged from 3 to 27 years. WES did not reveal any pathogenic variants. HLA-DRB1*11:01 carrier frequency was 60%, a significantly higher proportion than in the control population. No upregulation or mislocalization of the enzyme in statin-exposed or statin-naïve anti-HMGCR+ patients was observed, compared with controls.

Discussion

WES of a cohort of patients with dystrophy-like anti-HMGCR IMNM did not reveal any common rare variants of any gene, including cholesterol biosynthesis–related genes. HLA analysis showed a strong association with HLA-DRB1*11:01, previously mostly described in statin-exposed adult patients; consequently, a common immunogenic predisposition should be suspected, irrespective of statin exposure. Moreover, we were unable to conclusively demonstrate muscle upregulation/mislocalization of HMGCR in IMNM, whether or not driven by statins.

Introduction

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) is a type of inflammatory myopathy clinically characterized by subacute proximal weakness and high serum creatine kinase (CK) levels. Most patients with IMNM produce anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) or anti–signal-recognition particle (anti-SRP) autoantibodies. Most patients with anti-HMGCR IMNM have a history of exposure to statins; however, symptoms fail to resolve after statin discontinuation and immunosuppressive therapy becomes necessary.1

IMNM associated with anti-HMGCR was first described in the early 2000s by 3 groups reporting 38 statin-exposed adult patients presenting with acute or subacute proximal limb weakness.2-4 Many series since then have described further characteristics of the disease. Bulbar, respiratory, or cardiac involvement is extremely rare, and extramuscular symptoms are usually absent. Muscle biopsy shows muscle fiber necrosis and regeneration, frequent overexpression of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I), and macrophage-predominant inflammatory infiltrates with few lymphocytes. Serum CK levels are very elevated, usually ranging from 1,000 to 20,000 U/L.1 Although response to immunosuppressive drugs is usually good, some patients require more than 1 agent. Different combination strategies are based on daily corticosteroids, steroid-sparing immunosuppressive medication, and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Although CK levels tend to decrease with medication, they continue high and patients can only rarely be tapered off all treatment during follow-up.5 Although anti-HMGCR antibody titers correlate with disease severity and decrease after treatment, they rarely normalize in recovered patients.6

Up to 70%–75% of patients with anti-HMGCR IMNM have been exposed to statins, according to large series.4,7,8 Nevertheless, statins are widely used and data to establish statins as causal agents of IMNM generate controversy.9 Because previous exposure to statins correlates with age, a lower percentage of younger patients are exposed to statins compared with older patients (40% < 53 years vs 97% > 60 years). However, young age has been independently associated with greater disease severity and treatment refractoriness.5,10 A distinct anti-HMGCR IMNM phenotype has been reported in very young statin-naïve patients, with subacute clinical presentation and chronic progression mimicking muscular dystrophy. Cases of young asymptomatic patients with anti-HMGCR antibodies and high CK levels, although extremely rare, have been reported, with either progression of weakness without treatment11 or complete resolution of CK elevation after treatment with methotrexate and IVIG.12 Some children and young adults with anti-HMGCR IMNM respond reasonably or very well to immunotherapy.13,14 Nevertheless, pediatric cohort studies report that even patients treated early on in the disease course may experience clinical relapse or partial treatment response or may need adjuvant immunosuppressants other than corticosteroids to achieve disease stabilization.15,16 In fact, a recent case-based review reported that only one-third of children achieve complete remission after a mean follow-up of 31 months.17

A chronic progressive course, often resembling limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD), may manifest in statin-naïve patients affected by anti-HMGCR IMNM, and this may lead to misdiagnosis or a lengthy diagnostic delay, sometimes of years, until the anti-HMGCR antibodies are tested. We previously reported a series of 5 young patients with anti-HMGCR IMNM mimicking LGMD,18 and several subsequent reports have documented similar phenotypes.13,16,19,20 Two recent case reports have attested to muscle imaging evidence of progression from muscle edema to fatty infiltration over the years, demonstrating irreversible muscle damage.11,17 This fact would suggest that treatment must be prompt, given that immunomodulatory therapy initiated years after onset is usually unsuccessful in controlling the disease.

As yet unknown is why, in statin-naïve subjects, anti-HMGCR antibodies are produced, with subsequent development of IMNM. It has been postulated that ingesting natural sources of statins, e.g., mushrooms or red yeast rice, may trigger the disease in predisposed individuals, especially in Japan and China, where the association with pharmaceutical statin exposure is relatively low. Evidence from large series of anti-HMGCR patients has shown a well-established immunogenic association with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II. The DRB1*11:01 allele is strongly associated (OR = 25) with the development of anti-HMGCR autoantibodies in adults.21 Although the association has been described even in patients with no known statin exposure, a stronger association (OR = 80) is observed when there is a dual effect of HLA-DRB1*11:01 presence and statin exposure.8 In children, as opposed to adults, there is a strong association with the DRB1*07:01 allele.15 In a study of 6 children and young adults with a LGMD-like phenotype, haplotype analysis indicated the presence of one or other of those alleles in most of the patients, with no apparent correlation with age.14

HMGCR is a ubiquitous cytoplasmic antigen expressed in normal myotubes.22 Some authors claim that HMGCR enzyme upregulation, conformational changes, or mislocalization from the intracellular space to the cell surface can break immune tolerance and trigger autoantibody formation.1,23 Those mechanisms, especially when a HLA risk allele is present, would result in aberrant processing by antigen-presenting cells, producing the immunogenic epitopes that lead to an autoimmune humoral response.

Two groups have recently described a new autosomal recessive LGMD caused by biallelic loss-of-function variants in the HMGCR gene, that led to a conformational change in the enzyme and a phenotype of chronic progressive proximal weakness.24,25 Although 10 of the 15 patients who were tested did not have antibodies against HMGCR, this recent discovery of a new molecularly identified recessive LGMD may suggest that polymorphisms or pathogenic variants in HMGCR might change enzyme conformation and activate the immune system to produce autoantibodies. Another explanation for immunologic loss of tolerance against HMGCR may be mutations in other genes that encode proteins involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, leading to secondary compensatory overexpression of the enzyme in muscle cells and triggering of the immune response.

With a view to exploring the possible existence of a genetic predisposing condition, our aim was to describe in detail our series of young patients with chronic anti-HMGCR IMNM now enlarged to 11 and so expand knowledge of the unexplored pathophysiology of this distinct disease phenotype.

Methods

Gathered clinical and epidemiologic data for the study of 11 patients are summarized in Table 1. Antibodies against HMGCR were detected by ELISA in 8 patients and chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) in 3 patients. The patients were also tested for anti-SRP antibodies.

Table 1.

Main Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of 11 Patients With Statin-Naïve HMGCR+ IMNM

| Patient ID | Age at onset/Dx delay | Ab titers (range 0–19.9) | Initial CK levels (IU/L) | CK levels at Dx (U/L) | HLA-DRB1 | Initial symptoms | IS Tx (n) | Tx response | Current clinical status | Years of follow-up |

| P1 | Childhood/3 y | CLIA: 192 CU/mL | 8,000 | 1,000 | 04:01; 04:07 |

Subacute onset (2 mo) with symmetrical scapular > pelvic weakness and significant flexor axial involvement. Frequent falls. Mild scoliosis and a winged scapula from onset. No respiratory or bulbar involvement | IVIG, CS, AZA, MTX, MMF, RTX (6) Currently: IVIG in periodic pulses + PDN 5 mg/d |

Yes, partial | Proximal and symmetric weakness, MRC 3+/5 periscapular and 4/5 pelvic. Ambulant No distal weakness. Cervical flexion weakness 4/5 and axial flexion 3/5. Mild scoliosis, mild lumbar hyperlordosis, scapular winging R > L |

10 |

| P2 | Adolescence/12 y | ELISA: 132 SGU | 1,200 | 1,000 | Np | LL proximal weakness. Subacute, slowly progressive | IVIG, CS, AZA (3) | Yes, partial | Proximal UL and LL weakness 4/5. Ambulant | 14 |

| P3 | Childhood/20 y | ELISA: 325 SGU | 5,000–8,000 | 220 | 11:02; 11:04 |

Subacute axial and limb-girdle weakness | IVIG, CS, MTX, RTX (4) | Yes, partial | Manages to walk some steps at home but needs wheelchair outdoors | 23 |

| P4 | Early adulthood/18 y | ELISA: 111 SGU | 8,000 | 300 | 11:01; 01:01 |

Subacute axial and limb-girdle weakness | CS, IVIG, MTX, AZA, RTX, TAC (6) | Yes, partial | Proximal, distal, and axial weakness. MRC 3/5. Ambulant | 18 |

| P5 | Early childhood/27 y | CLIA: 59.5 CU/mL | 6,000 | 200 | 07:01; 13:02 |

Subacute onset of proximal weakness (loss of ambulation) and skin rash on knees and knuckles, treated with CS for 5 y with a partial response. Ambulation recovered after the first year of treatment | CS, MTX, MMF (3) Currently: MMF 1g/12h |

Yes, partial | Mild proximal UL weakness (biceps 4/5) and severe in LL (psoas and glutei 1/5) Ambulant |

35 |

| P6 | Early adulthood/7 y | ELISA: 229 SGU | 8,500 | 3,000 | 07:01; 15:01 |

Proximal limb-girdle weakness Motor clumsiness since early childhood |

CS, MTX, IVIG (3) | No | Severe proximal weakness Wheelchair bound |

15 |

| P7 | Childhood/25 y | ELISA: 183 SGU | 10,000 | 225 | 11:01; 14:54 |

Subacute proximal weakness in LL. | CS, MTX, IVIG (3) | No | Proximal, distal, axial weakness Wheelchair dependent Respiratory failure: nocturnal NIV since 21 y |

35 |

| P8 | Adolescence/5 y | ELISA: 177 SGU | 7,000 | 2,000 | 11:01; 08:01 |

Progressive limb-girdle weakness, scoliosis and rigid spine, asymmetric scapular winging, axial involvement | CS, IVIG (2) | Yes, partial | Clinical improvement, in particular in shoulder girdle | 10 |

| P9 | Adolescence/14 y | Immunodot strong +. Confirmed in rat triple tissue (HALIP) | UNL X5 | 1,082 | 07:01; 11:01 |

Proximal weakness in LL, around 4 y after also in UL. In 2012, treated with CS for 1 y without improvement | CS, MTX, AZA, IVIG (4) | Yes, partial | Mild proximal deficit: UL 4/5 and LL 4/5. Muscle pain at rest and after exercise | 15 |

| P10 | Early adulthood/6 y | CLIA: 467,5 CU/mL | 3,000 | 5,500 | 11:01; 11:04 |

Progressive proximal LL weakness Stopped running at 23 y. UL affected 2 y from onset. |

CS, MTX, IVIG (3) | Yes, partial | Proximal deficit in UL 4/5, LL 3/5, asymmetric (worse on left side). Wheelchair bound. Mild dysphagia. Elbow retractions | 10 |

| P11 | Childhood/19 y | ELISA: 948 SGU | 12,500 | 83 | 11:01; 01:02 |

Subacute onset (mo) of LL weakness, frequent falls, ambulation lost in 1 y. At 12 y, surgery for scoliosis. At 14 y, respiratory involvement. Cervical rigidity developed | IVIG, CS, AZA (3) Currently: IVIG and CS |

Yes, partial | Wheelchair bound. Only head, hand, and finger movements Severe respiratory involvement: currently tracheostomy, FVC 10%, IV 11 h/d |

22 |

Abbreviations: Ab = antibody; AZA = azathioprine; CLIA = chemiluminescent immunoassay; CS = corticosteroid; CU/mL = chemoluminescence units/milliliter; Dx = diagnosis; FVC = forced vital capacity; HALIP = HMGCR-associated liver immunofluorescence pattern; HLA = human leukocyte antigen; HMGCR = 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase; IMNM = immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy; IS Tx = immunosuppressive treatment; IV = invasive ventilation; IVIG = IV immunoglobulin; LL = lower limb(s); MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; MRC = Medical Research Council Muscle Strength Scale; MTX = methotrexate; NIV = noninvasive ventilation; Np = not performed; PDN = prednisone; R > L = right > left; RTX = rituximab; SGU = standard units for ELISA; TAC = tacrolimus; Tx = treatment; UL = upper limb(s); U/L = units per liter; UNL = upper normal limit.

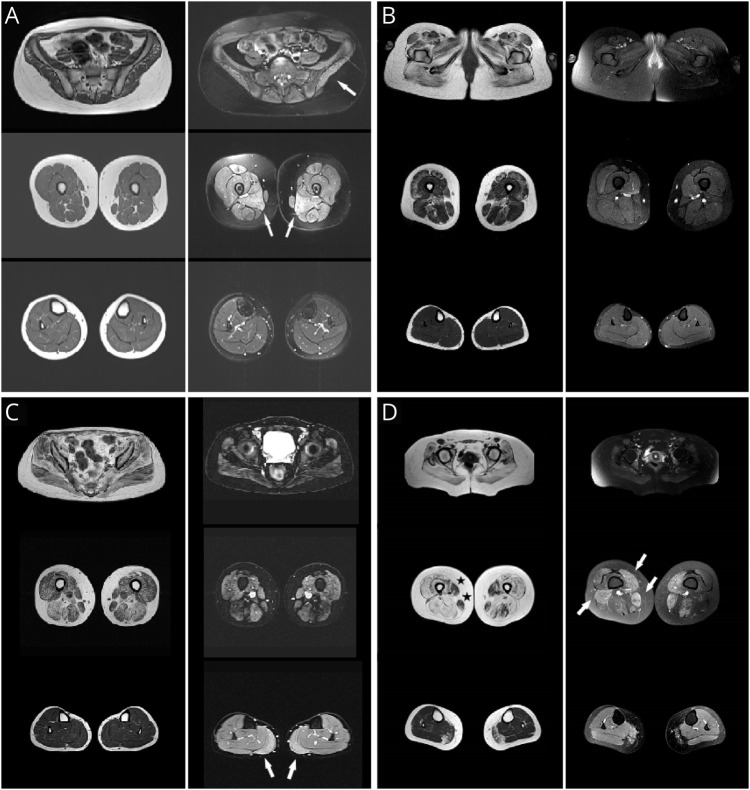

Muscle Imaging

Muscle imaging studies—MRI or CT—were performed in 10 patients on diagnosis (9 MRI and 1 CT). The MRI protocol included T1-weighted (T1w), short-T1 inversion recovery (STIR), and T2-weighted (T2w) sequences.

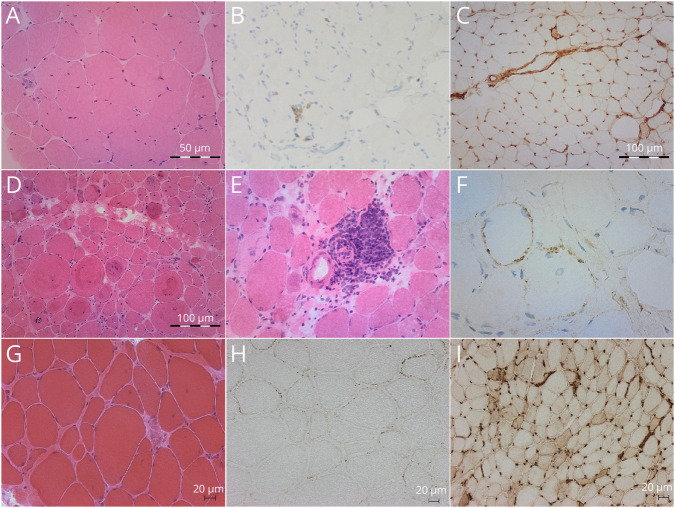

Muscle Pathology

Muscle biopsies were performed in all 11 patients and were previously processed for routine histochemical staining and for immunohistochemistry, as previously described.26 For the purposes of this study, MHC-I and membrane attack complex (MAC) immunostaining were assessed in 6 and 4 patients, respectively. In addition, HMGCR protein expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry in 1 statin-exposed HMGCR+ IMNM patient, as previously described,26 and by immunofluorescence in 2 statin-naïve HMGCR+ IMNM patients and 1 healthy control using purified immunoglobulin G (IgG) from statin-exposed HMGCR+ patient serum compared with a seronegative control serum (IgG Purification Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The obtained IgG was labeled with biotin following the manufacturer's instructions (EZ Link Biotinylation Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Muscle sections were immunolabeled using biotinylated IgG and Alexa 594 streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Anti-HMGCR purified biotinylated IgG immunoreactivity was double-checked by incubating patient seropositive and control seronegative sera in triple rat tissue (NOVA Lite Rat Liver-Kidney-Stomach Kit, Inova Diagnostics, San Diego, CA) to observe the specific HMGCR-associated liver immunofluorescence pattern (HALIP), as previously described.27 HMGCR expression was also assessed in 3 patient samples using a commercial antibody compared with a healthy control (dilution 1:25 of anti-HMGCR sc-271595, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX).

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed in all 11 patients to study coding exons and flanking regions ( ±50 base pairs) of candidate genes. In brief, DNA libraries were prepared using Kapa reagents (Roche, including HyperExome probes targeting the whole exome) and sequenced in a NextSeq 500 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The resulting fastq sequencing files were analyzed using standard procedures, i.e., BWA alignment, GATK variant calling, and ExomeDepth for copy number variants, and variants were annotated using ANNOVAR.28-30 Data filtering to obtain candidate variants included assessment of population frequencies, inheritance model, and impact on the protein, among others.

Variants were classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines.31 Evaluated were rare variants in 40 genes related with the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway: ACAT1, ACAT2, CARM1, COQ2, CREBBP, CYP51A1, DHCR24, DHCR7, EBP, EGR2, FDFT1, FDPS, GGPS1, HMGCR, HMGCS1, HMGCS2, HSD17B7, IDI1, IDI2, INSIG1, INSIG2, LBR, LIPA, LSS, MSMO1, MVD, MVK, NSDHL, PMVK, PPARA, RXRA, SC5D, SCAP, SMARCD3, SOAT1, SQLE, SREBF1, SREBF2, TBL1X, and TM7SF2. Also evaluated were variants in 139 known genes associated with muscular dystrophies and myopathies.

Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing and Statistical Analysis

We used next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully sequence the HLA of 10 patients to determine whether they carried the DRB1*11:01 or DRB1*07:01 alleles or other unknown HLA associations. Exons 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7/8 of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C; exons 2 and 3 of HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DRB1; and exons 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of HLA-DPB1 were amplified by multiplex PCR (NGSgo®-MX6-1).32 NGS was performed on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) using the same kit. All samples were simultaneously sequenced in a MiSeq run, and the resulting sequences were analyzed using NGSengine (version 2.8.1.27684; GenDX, Utrecht, Netherlands) and IMGT/HLA Database (version 3.50.0). The percentage of individuals carrying each allele (carrier frequency) was calculated for comparison with carrier frequency for the general population, obtained from the Allele Frequencies database.33-39

To perform the statistical analysis, the weighted average populational carrier frequency was calculated considering the number of anti-HMGCR+ patients from each country represented in the study. Data were compiled in a coded database. The degree of HLA data-disease association was expressed as an odds ratio (OR) value for a 95% confidence interval (CI). Fisher exact test, OR, and CI calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism v8.0 package.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All patients consented to participate in this observational study. Clinical evaluations and complementary tests were performed as part of the routine diagnostic workup.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Clinical and Laboratory Features

Of the 11 studied patients, 10 were female (90.9%), and in terms of ethnicity, 10 were White (6 Spanish, 2 Romanian, 1 Italian, and 1 Algerian) and 1 was Latin American (Colombian). All patients were positive for anti-HMGCR and negative for anti-SRP antibodies according to ELISA or CLIA detection tests. The main clinical characteristics and anti-HMGCR antibody titers are summarized in Table 1.

Birth and early development were normal in all patients. Age at onset ranged from 3 to 25 years, and diagnostic delay ranged from 3 to 27 years. Most of the patients presented with subacute proximal weakness in the lower limbs (and less frequently in the upper limbs) that had developed over months; 1 patient presented with a concomitant skin rash in the knee and knuckle areas that disappeared after steroid therapy; 1 patient had the Raynaud phenomenon; 1 patient had mild scoliosis and a winged scapula from onset; 5 patients (45.5%) showed axial weakness, either at onset or during evolution; 2 patients had cervical rigidity; 1 patient had bulbar symptoms (P10); and finally, 7.5 and 16 years after disease onset, 2 patients experienced respiratory involvement requiring noninvasive (P7) and invasive ventilation (P11). At symptom onset, CK levels were markedly elevated (1,200–12,500 U/L).

Muscle Imaging

A muscle imaging study was performed in 10 patients (9 MRI and 1 CT). MRI results for 6 patients (P1 to P6), shown in Figure 1 and eFigure 1, suggest that progressive muscle atrophy correlates with longer disease duration. T1w images showed early-stage absent or mild fatty infiltration in the gluteal muscles that, symmetrically over time, progressed to the thigh muscles, with no clear predominance of the anterior or posterior compartment and, in the advanced disease stage, involved the distal leg muscles (typically the medial gastrocnemius muscle). The presence of edema, revealed as STIR hyperintensity, was variable and usually patchy in the thighs and legs, irrespective of disease duration.

Figure 1. Lower-Limb MRI Scans (T1w and STIR Images) From 4 Patients.

Disease progression in years. (A) Patient 1 (P1), 3 years. (B) P2, 12 years. (C) P3, 20 years. (D) P4, 18 years. Left columns: Axial T1w images in the pelvis, thigh, and leg. Right columns: Matched STIR images. Note progressive symmetric muscle involvement in relation to disease progression. T1w images initially show fatty infiltration in the gluteal muscles that later spreads to the thigh muscles, and in more advanced disease stages, leg involvement affecting the medial gastrocnemius muscle. Note also the preservation of the gracilis and sartorius muscles (asterisks), even in late disease stages. STIR images show increased water content in some muscles (patchy inflammation) in 3 patients irrespective of disease evolution: bilaterally in the gluteal and adductor mayor muscles in P1 (A, arrows), in the thighs and medial gastrocnemius muscle in P3 (C, arrows), and in the thighs in P4 (D, arrows).

Biopsy Findings

Muscle biopsy results were available for 10 patients. Although muscle pathology features were similar in all studied patients, lesions varied from mild to severe and were characterized by increased variability in fiber size, mild to moderate endomysial fibrosis, and the consistent presence of very few to abundant necrotic and regenerative fibers. Muscle biopsies from P6 and P8 showed several whorled fibers. Inflammatory infiltrates were present in 4 patients, generally very scarce except in 2 patients, one of whom (P6) showed several perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. MHC-I was overexpressed in 5 of 6 patients. MAC/C5b-9 deposition in the membrane of non-necrotic fibers was observed in 4 of 4 tested patients. Muscle pathology details are summarized in Table 2, and images for 3 muscle biopsies are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Summarized Muscle Pathology Details

| Patient ID | Increased fiber size variability | Muscle fiber necrosis | Inflammatory infiltrates | Endomysial fibrosis | MHC class I overexpression | MAC deposition | Additional findings |

| P1 | Important | Abundant | Scarce | Mild | Yes | np | |

| P2 | Moderate | Mild | Absent | Mild | np | np | |

| P3 | Moderate | Mild | Absent | Mild | np | np | |

| P4 | Moderate | Mild | Absent | Mild | np | np | |

| P5 | Moderate | Mild | Absent | Mild | Yes | np | |

| P6 | Moderate | Abundant | Moderate | Mild | Yes | Yes | Whorled fibers |

| P7 | Moderate | Moderate | Scarce | Absent | Yes | np | |

| P8 | Moderate | Moderate | Absent | Moderate | Yes | Yes | Whorled fibers |

| P9 | Moderate | Moderate | Absent | Mild | np | Yes | |

| P10 | Moderate | Abundant | Moderate | Moderate | Absent | Yes | |

| P11 | Moderate | nk | nk | nk | nk | nk |

Abbreviations. MAC, membrane attack complex; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; np, not performed; nk, not known.

Figure 2. Muscle Biopsy Findings From 3 Patients.

(A–C) Patient 5 (P5). (D–F) P6. (G–I): P8. (A, D, E, G) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). (B) CD8 immunohistochemistry. (C, I) MHC class I immunohistochemistry; (F, H) MAC/C5b-9 immunohistochemistry. Histology shows mild to severe changes ranging from minimal to important variability in muscle fiber size, variable numbers of necrotic fibers, and absent to moderate endomysial fibrosis. Note the large number of whorled fibers in P6. Note also the few CD8 lymphocytes present in P5, in contrast with the large mononuclear perivascular inflammatory infiltrate in P6. MHC class I overexpression is absent in P5 but is diffusely overexpressed in P8. Membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition in the muscle fiber membrane can be observed in P6 and P8.

No overexpression of the HMGCR protein was observed in the muscle fibers of any of the studied patients after incubation with purified IgG from the patient's HMGCR+ serum, matching with IgG from a control serum, and comparison with a healthy control muscle. Immunofluorescence images are shown in eFigure 2. No differences in HMGCR expression using a commercial antibody were observed either (data not shown).

Treatment and Clinical Response

All patients received a combination of 2 or more immunosuppressive medications (range 2–6; median 3). Corticosteroids were administered to all patients and IVIG to 10 of the 11 patients. The most frequently administered immunosuppressants were methotrexate (n = 8) and azathioprine (n = 5), followed by rituximab (n = 3), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 2), and tacrolimus (n = 1). Of note, 2 patients with disease evolution of 7 and 25 years failed to respond to treatment, whereas the remaining patients partially responded, with either initial motor improvement or disease stabilization. No patient achieved full remission, including cases diagnosed early on and treated at 3, 5, and 6 years from onset. Treatment intensification was tried in all cases, but outcomes were no better. Table 1 reports treatments and current clinical status for the 11 patients.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

WES did not reveal any causative pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in 40 genes that encode proteins involved in cholesterol biosynthesis. In this subset of candidate genes, identified in 4 patients were 6 heterozygous variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in IDI2, MVD, HMGCS2, SOAT1, and DHCR7. A patient (P9) with a VUS in HMGCS2 had another VUS in DHCR7, both detected in a heterozygous state in genes with an autosomal recessive inheritance (see eTable 1 for more details). Likewise, no pathogenic variants that could explain the phenotype were observed in any myopathy-causative gene. Moreover, any rare variant (gnomAD v.2.1.1 allele frequency <0.05) in other genes was found to be common to all patients.

Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing

Of 10 patients, 6 were carriers of the HLA-DRB1*11:01 and 3 were carriers of the DRB1*07:01 allele (1 was a carrier of both risk alleles). The other 2 patients carried neither allele, specifically the only Latin American in the cohort (P1) and a carrier of DRB1*11:02 and DRB1*11:04 (P3). A significantly higher proportion of the DRB1*11:01 allele was observed in the anti-HMGCR+ patients compared with the general population (60% vs 13.7%; OR = 9.4, p = 0.0009, CI = 2.65–33.39). By contrast, the percentage of patients carrying DRB1*07:01 did not differ from the weighted carrier frequency for the general population (30% vs 27.4%; OR = 0.45, p = 1.56; CI = 0.40–6.05).

Discussion

Performing WES and focusing on genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, we could not prove a monogenic predisposition in statin-naïve children and young adults with anti-HMGCR IMNM. Nevertheless, we did find a strong association with HLA-DRB1*11:01, which is strongly and mostly associated with statin-related IMNM in adults.

In children and young individuals compared with statin-exposed adults, anti-HMGCR IMNM differs in terms of clinical evolution, response to treatment, and prognosis. Patients tend to develop proximal muscle weakness early on in childhood or adolescence, and evolution is characteristically chronic and slowly progressive, resembling a muscular dystrophy, often resulting in a delayed diagnosis.14-17 Therefore, a systematic suspicion of IMNM and testing for specific autoantibodies, especially in children and adolescents with suspected but not genetically confirmed LGMD, may help improve diagnostic time lines and lead to early treatment before muscle damage becomes irreversible.

Although most of the patients in our cohort showed an initial partial response to immunosuppressive medication, weakness progressed over long-term follow-up despite intensive treatment. Muscle biopsy showed different degrees of myofiber necrosis and macrophage infiltration, with variable overexpression of MHC-I and, in all tested samples, complement deposition on the surface of non-necrotic fibers. These findings are similar to those from larger studies assessing muscle pathology in young and adult patients exposed or not to statins, characterized by necrosis and regeneration of muscle fibers with mild or absent lymphocytic infiltrates. MAC deposition on sarcolemma has been reported in 65% of the patients by some groups, whereas other authors have reported MAC deposition exclusively in the cytoplasm of some necrotic fibers.40,41 Other groups have described a constant expression of the autophagy marker p62 in the sarcoplasm of some fibers.42,43 Nevertheless, p62 immunoreactivity was not systematically assessed in our series. Despite the idea of complement inhibition has been explored considering MAC deposition in necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, a recent randomized phase 2 trial with the C5 inhibitor zilucoplan failed to show significant clinical improvements or creatine kinase decrease in these patients.44 Such findings may relate with the fact that necrotic and regenerating fibers, also in nonimmune myopathies, activate complement, and therefore, complement deposition is not a specific finding of IMNM.45,46 According to this, complement inhibition may not be the adequate therapy target, but other potential drugs have shown promising effects in vitro.47

Our MRI findings suggest that this imaging tool can be useful especially in early stages, when evident patchy muscle inflammation may raise suspicion of an inflammatory myopathy. Diffuse fatty replacement, with active inflammation in some cases, was evident in advanced disease stages. Nevertheless, in our patients we did not identify a specific pattern of muscle involvement. This observation is similar to what has been reported in adult patients with anti-HMGCR IMNM.48 Despite a characteristic pattern of muscle involvement was proposed affecting preferentially hip rotators and glutei muscles, after applying regression models, the estimated positive predictive value was only 55%. A recent retrospective study in patients with IMNM showed that muscle MRI can be useful for monitoring disease activity and that the percentage of STIR+ muscles correlated with higher risk of fat replacement at follow-up, but a specific pattern of involvement was not identified either.49 Regarding young statin-naïve patients, only few imaging data from case reports are available with similar findings,11,17 and there are not larger series to allow a proper comparation.

Some authors claim that upregulation of HMGCR and/or conformational changes in the enzyme can increase immunogenicity.1 Also meriting consideration is mislocalization from the intracellular space to the cell surface, where there could be possible targeting by autoantibodies.23 The mechanism of this latter option is unclear, and it is not even known whether it is feasible with HMGCR, but it has been described for other intracellular proteins. Macrophages, for instance, can express endoplasmic reticulum proteins in the plasma membrane when they fuse to form multinucleated giant cells,50 just as fibroblasts can express chaperone proteins.51

Those mechanisms (overexpression, conformational changes, and/or mislocalization), together with specific immunogenic HLA alleles, would be the main route for statins, competitive inhibitors of HMGCR, to trigger the disease through a humoral immune response.1 Alternatively, anti-HMGCR autoantibodies might cross-react with a different unidentified antigen. It cannot be ruled out, either, that the autoantibodies may enter the muscle fibers, as has been shown for anti-DNA antibodies,52 but recent experiments in healthy myotubes show that the intracellular antigen is only accessible to anti-HMGCR antibodies after cell permeabilization.22 This was the reason that led us to investigate whether the existence of a common genetic disorder could explain a predisposition to produce antibodies against HMGCR in the absence of statin exposure and why we evaluated HMGCR expression in muscle fibers in our patients.

It has been shown that none of a large cohort of patients with genetically determined muscular dystrophy had anti-HMGCR antibodies, proving their high specificity.53 The only previous attempt to seek genetic mutations in statin-naïve patients diagnosed with anti-HMGCR IMNM was done by a group that performed WES in 8 treatment-refractory patients, none of whom had a known pathogenic variant in any of the muscular dystrophy genes.5

Nevertheless, despite the fact that HMGCR is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway that ultimately enables synthesis of cholesterol, cholesterol pathway–related genes have never been studied. We hypothesized that a mutation in a gene linked to cholesterol biosynthesis could cause HMGCR overexpression, either as a compensatory mechanism when cholesterol production is decreased or because of deficient degradation of the enzyme. This overexpression would cause a loss in immune tolerance and consequent production of self-reacting antibodies against HMGCR—similar, in fact, to the expected statin-mediated mechanism. Some of the studied genes linked to cholesterol biosynthesis encode the enzymes needed to produce cholesterol, including HMGCR, among others.54 For instance, one of our patients was carrier of a VUS in HMGCS2, which encodes the mitochondrial HMG-CoA synthase needed for cholesterol synthesis. This enzyme is analogous to the cytoplasmic HMG-CoA synthase encoded by HMGCS1. Nevertheless, the VUS was a missense variant detected in heterozygosis in a gene with autosomal recessive inheritance and was classified by most pathogenicity predictors as “benign, neutral, or tolerated.” This fact and the presence in only 1 patient suggest that the VUS is extremely unlikely causative of a cholesterol deficiency and secondary HMGCR upregulation, as happens with the rest of the variants found. Furthermore, any rare variants were detected in HMGCR itself that could cause a change in epitope conformation and antigen presentation and finally trigger autoantibody formation.

Other analyzed genes encode sterol sensors that regulate the cellular accumulation of sterols and are essential to the endogenous degradation of HMGCR mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Some examples of those regulatory elements are the Insig and Scap proteins.54,55 In fact, an animal study has shown that genetic INSIG1/2 deletion results in an accumulation of HMGCR to a level that is approximately 20-fold higher than in wild-type mice.56 Another gene included in our study was COQ2, which encodes the coenzyme Q2 necessary for coenzyme Q10 synthesis. The reason for its inclusion was the evidence that most patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS)—included in the broader concept of statin-induced myopathy—show overt coenzyme Q10 reduction in blood and muscle samples.57-59 That evidence has led to several clinical trials designed to clarify whether Q10 supplementation could be useful to treat SAMS, although contradictory results show that the effect remains controversial.60-63 Whether a coenzyme Q10 deficit is directly pathogenic is not known. Yet, a possible, although unlikely, explanation could be that levels of coenzyme Q10 are reduced in non–statin-related HMGCR+ IMNM. Ruling out this possibility was the reason why we sought specific mutations in the COQ2 gene.

Finally, in the HLA analysis of our cohort to study possible associations with statin-naïve anti-HMGCR IMNM, we found that there was a stronger association with HLA-DRB1*11:01 than in the general population (60% vs 13.7%, OR = 9.4, p = 0.0009), the same allele associated with anti-HMGCR IMNM in adults mostly exposed to statins.14,15,21 By contrast, the proportion of patients who carried the DRB1*07:01 allele, previously associated with pediatric forms,14,15,21 was not significantly higher than that in the general population. Those findings lead to different conclusions. First, DRB1*11:01 association is not restricted to the adult forms and also has an important role in pediatric patients with chronic forms of anti-HMGCR IMNM. Second, it could be hypothesized that the DRB1*11:01 carriers have been exposed to natural sources of statins, with the combination of statins and a HLA risk allele triggering the disease. This latter possibility seems very unlikely because we would expect some familial aggregation that does not occur in IMNM. Nonetheless, despite this link never having been described, it cannot be fully ruled out.

Regarding the study of HMGCR expression in muscle, we found no differences in protein expression or localization in patient biopsies using natural and commercial anti-HMGCR antibodies and so found an identical result for a sample from a statin-exposed adult patient. Nevertheless, the small sample size should be considered as a possible limitation and these results should be confirmed with higher number of skeletal muscle biopsies. Similar findings were reported by Allenbach et al. showing weak and sparse sarcolemma binding with antibodies against HMGCR in healthy fibers not undergoing necrosis,22 in contrast with a robust binding in regenerating NCAM-positive fibers.7 This fact calls into question the pathogenic role of anti-HMGCR antibodies and the antibody or complement-dependent induction of necrosis in necrotizing autoimmune myopathy.9,64,65 Still, based on our experience, and contrary to what has previously been postulated, overexpression or mislocalization of the enzyme leading to increased immunogenicity and antibody formation in anti-HMGCR+ IMNM cannot be conclusively demonstrated, independently of statin exposure.

Infantile and juvenile anti-HMGCR IMNM is a rare entity, clinically different from acute adult forms of the disease, characterized by treatment refractoriness, and a slow but progressive evolution that mimics muscular dystrophy. Although a genetic predisposition has been postulated, it has never been deeply evaluated. In our study, we have described a large series of young patients with dystrophy-like anti-HMGCR IMNM. Of interest, we found a strong association with HLA-DRB1*11:01, previously linked to mainly statin-exposed adult forms of anti-HMGCR IMNM. Because WES failed to reveal any common rare variants, including in genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, a monogenic predisposition could not be demonstrated. Furthermore, we did not find overexpression or mislocalization of HMGCR in patient muscle fibers. The high prevalence of HLA-DRB1*11:01 suggests a common immunogenic risk factor shared by statin-naïve young patients and statin-exposed adults. Further research is needed to explore the possible presence of environmental, epigenetic, or post-translational factors that may modulate disease onset and course resulting in such different phenotypes, as well as different pathophysiologic mechanisms in antibody formation beyond HMGCR overexpression or mislocalization.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Department of Medicine at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Glossary

- anti-HMGCR

anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase

- anti-SRP

anti–signal-recognition particle

- CI

confidence interval

- CK

creatine kinase

- CLIA

chemiluminescent immunoassay

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IMNM

immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy

- IVIG

IV immunoglobulin

- LGMD

limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

- MHC-I

major histocompatibility complex class I

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OR

odds ratio

- SAMS

statin-associated muscle symptoms

- STIR

short-T1 inversion recovery

- T1w

T1-weighted

- T2w

T2-weighted

- WES

whole exome sequencing

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Laura Llansó, MD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Alba Segarra-Casas, MD | Department of Genetics, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Cristina Domínguez-González, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Research Institute imas12, Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Edoardo Malfatti, MD, PhD | Université Paris-Est Créteil, INSERM, U955 IMRB; AP-HP, Hôpital Mondor, FHU SENEC, Service d'Histologie, Créteil, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Solange Kapetanovic, MD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Osakidetza Basque Health Service, Basurto University Hospital, Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Benjamín Rodríguez-Santiago, MD, PhD | Department of Genetics, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid; Genomic Instability Syndromes and DNA Repair Group and Join Research Unit on Genomic Medicine UAB, Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Oscar de la Calle, MD, PhD | Immunology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Rosa Blanco | Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain | Major role in the acquisition of data; additional contributions (in addition to one or more of the above criteria) |

| Amelia Dobrescu, MD | Department of Genetics, Craiova University Hospital, Romania | Study concept or design |

| Andrés Nascimento-Osorio, MD | Neuropaediatrics Department, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Fundación Sant Joan de Déu, CIBERER - ISC III, Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Andrés Paipa, MD, PhD | Neurology Department, Neuromuscular Unit, IDIBELL-Hospital de Bellvitge, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Aurelio Hernandez-Lain, MD | Pathology Department, Neuropathology Unit, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Cristina Jou, MD | Pathology Department, Institut Pediàtric de Recerca, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, and MetabERN, Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Anaís Mariscal, MD, PhD | Immunology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Laura González-Mera, MD | Neurology Department, Neuromuscular Unit, IDIBELL-Hospital de Bellvitge, Hospitalet de Llobregat; Department of Neurology, Hospital de Viladecans, Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Ana Arteche, MD | Department of Genetics, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Research Institute imas12, Madrid, Spain | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Cinta Lleixà, PhD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain | Study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data; additional contributions (in addition to one or more of the above criteria) |

| Marta Caballero-Ávila, MD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Álvaro Carbayo, MD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Ana Vesperinas, MD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain | Study concept or design |

| Luis Querol, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Eduard Gallardo, PhD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Montse Olivé, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Institut de Recerca Sant Pau (IR Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain. Biomedical Network Research Centre on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III cofunded by ERDF/FEDER (Una manera de hacer Europa) under grant FIS PI21/01621 awarded to MO. LL is supported by a Grífols-funded grant (Beca de formación en enfermedades neuromusculares Isabel Illa).

Disclosure

L. Llansó, C. Domínguez-González, A. Hernandez-Lain, E. Malfatti, L. González-Mera, A. Nascimento-Osorio, C. Jou, C. Lleixà, M. Caballero-Ávila, A. Carbayo, A. Vesperinas, E. Gallardo, and M. Olivé are members of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Mohassel P, Mammen AL. Anti-HMGCR myopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5(1):11-20. doi: 10.3233/JND-170282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauchais AL, Iba Ba J, Maurage P, et al. Polymyositis induced or associated with lipid-lowering drugs: five cases. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2004;25(4):294-298. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needham M, Fabian V, Knezevic W, Panegyres P, Zilko P, Mastaglia FL. Progressive myopathy with up-regulation of MHC-I associated with statin therapy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(2):194-200. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grable-Esposito P, Katzberg HD, Greenberg SA, Srinivasan J, Katz J, Amato AA. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(2):185-190. doi: 10.1002/mus.21486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiniakou E, Pinal-Fernandez I, Lloyd TE, et al. More severe disease and slower recovery in younger patients with anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarylcoenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(5):787-794. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):4087-4093. doi: 10.1002/art.34673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limaye V, Bundell C, Hollingsworth P, et al. Clinical and genetic associations of autoantibodies to 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme a reductase in patients with immune-mediated myositis and necrotizing myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(2):196-203. doi: 10.1002/mus.24541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalakas MC. Myositis: are autoantibodies pathogenic in necrotizing myopathy? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(5):251-252. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2018.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassardjian CD, Lennon VA, Alfugham NB, Mahler M, Milone M. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):996-1003. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiebeler M, Franke R, Ingenerf M, et al. Slowly progressive limb-girdle weakness and HyperCKemia - limb girdle muscular dystrophy or anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA-reductase-myopathy? J Neuromuscul Dis. 2022;9(5):607-614. doi: 10.3233/JND-220810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki R, Yunoki T, Nakano Y, et al. A young female case of asymptomatic immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: a potential diagnostic option of antibody testing for rhabdomyolysis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2023;33(2):183-186. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2022.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohassel P, Foley AR, Donkervoort S, et al. Anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase necrotizing myopathy masquerading as a muscular dystrophy in a child. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(6):1177-1181. doi: 10.1002/mus.25567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohassel P, Landon-Cardinal O, Foley AR, et al. Anti-HMGCR myopathy may resemble limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6(1):e523. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishi T, Rider LG, Pak K, et al.; Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Study Group. Association of anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase autoantibodies with DRB1*07:01 and severe myositis in juvenile myositis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(7):1088-1094. doi: 10.1002/acr.23113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang WC, Uruha A, Suzuki S, et al. Pediatric necrotizing myopathy associated with anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(2):287-293. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sener S, Batu ED, Sari S, et al. A child with refractory and relapsing anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase myopathy: case-based review. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2023;10(2):279-291. doi: 10.3233/JND-221557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paipa Merchan A, Jou C, Kapetanovic S, et al. Early onset autoimmune necrotizing myopathy associated with anti-HMGCR antibodies: an unmissable diagnosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(S2):S249-S316. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.06.233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tard C, Tiffreau V, Jaillette E, et al. Anti-HMGCR antibody-related necrotizing autoimmune myopathy mimicking muscular dystrophy. Neuropediatrics. 2017;48(6):473-476. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CH, Liang WC. Pediatric immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1123380. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1123380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mammen AL, Gaudet D, Brisson D, et al. Increased frequency of DRB1*11:01 in anti-hydroxymethylglutaryl- coenzyme a reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(8):1233-1237. doi: 10.1002/acr.21671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allenbach Y, Arouche-Delaperche L, Preusse C, et al. Necrosis in anti-SRP+ and anti-HMGCR+myopathies: role of autoantibodies and complement. Neurology. 2018;90(6):e507-e517. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arouche-Delaperche L, Allenbach Y, Amelin D, et al. Pathogenic role of anti-signal recognition protein and anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase antibodies in necrotizing myopathies: myofiber atrophy and impairment of muscle regeneration in necrotizing autoimmune myopathies. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):538-548. doi: 10.1002/ana.24902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yogev Y, Shorer Z, Koifman A, et al. Limb girdle muscular disease caused by HMGCR mutation and statin myopathy treatable with mevalonolactone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(7):e2217831120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217831120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales-Rosado JA, Schwab TL, Macklin-Mantia SK, et al. Bi-allelic variants in HMGCR cause an autosomal-recessive progressive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110(6):989-997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Luna N, Gallardo E, Illa I. In vivo and in vitro dysferlin expression in human muscle satellite cells. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(10):1104-1113. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.10.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarado-Cardenas M, Marin-Sánchez A, Martínez MA, et al. Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy: a distinct new IFL pattern can increase the rate of HMGCR antibody detection by clinical laboratories. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(12):1161-1166. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754-1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297-1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al.; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creary LE, Sacchi N, Mazzocco M, et al. High-resolution HLA allele and haplotype frequencies in several unrelated populations determined by next generation sequencing: 17th International HLA and Immunogenetics Workshop joint report. Hum Immunol. 2021;82(7):505-522. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enrich E, Campos E, Martorell L, et al. HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 allele and haplotype frequencies: an analysis of umbilical cord blood units at the Barcelona Cord Blood Bank. HLA. 2019;94(4):347-359. doi: 10.1111/tan.13644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Re V, Caggiari L, Monti G, et al. HLA DR-DQ combination associated with the increased risk of developing human HCV positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is related to the type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75(2):127-135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rendine S, Ferrero NM, Sacchi N, Costa C, Pollichieni S, Amoroso A. Estimation of human leukocyte antigen class I and class II high-resolution allele and haplotype frequencies in the Italian population and comparison with other European populations. Hum Immunol. 2012;73(4):399-404. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Páez-Gutiérrez IA, Hernández-Mejía DG, Vanegas D, Camacho-Rodríguez B, Perdomo-Arciniegas AM. HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 and -DQB1 allele and haplotype frequencies of 1463 umbilical cord blood units typed in high resolution from Bogotá, Colombia. Hum Immunol. 2019;80(7):425-426. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnaiz-Villena A, Benmamar D, Alvarez M, et al. HLA allele and haplotype frequencies in Algerians. Relatedness to Spaniards and Basques. Hum Immunol. 1995;43(4):259-268. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(95)00024-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pingel J, Solloch UV, Hofmann JA, Lange V, Ehninger G, Schmidt AH. High-resolution HLA haplotype frequencies of stem cell donors in Germany with foreign parentage: how can they be used to improve unrelated donor searches? Hum Immunol. 2013;74(3):330-340. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.allelefrequencies.net

- 40.Watanabe Y, Uruha A, Suzuki S, et al. Clinical features and prognosis in anti-SRP and anti-HMGCR necrotising myopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1038-1044. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alshehri A, Choksi R, Bucelli R, Pestronk A. Myopathy with anti-HMGCR antibodies: perimysium and myofiber pathology. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(4):e124. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allenbach Y, Benveniste O, Stenzel W, Boyer O. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(12):689-701. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00515-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merlonghi G, Antonini G, Garibaldi M. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM): a myopathological challenge. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21(2):102993. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mammen AL, Amato AA, Dimachkie MM, et al. Zilucoplan in immune-mediated necrotising myopathy: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(2):e67-e76. doi: 10.1016/s2665-9913(23)00003-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spuler S, Engel AG. Unexpected sarcolemmal complement membrane attack complex deposits on nonnecrotic muscle fibers in muscular dystrophies. Neurology. 1998;50(1):41-46. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engel AG, Biesecker G. Complement activation in muscle fiber necrosis: demonstration of the membrane attack complex of complement in necrotic fibers. Ann Neurol. 1982;12(3):289-296. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Julien S, van der Woning B, De Ceuninck L, et al. Efgartigimod restores muscle function in a humanized mouse model of immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(12):4006-4011. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Carrino JA, et al. Thigh muscle MRI in immune-mediated necrotising myopathy: extensive oedema, early muscle damage and role of anti-SRP autoantibodies as a marker of severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):681-687. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fionda L, Lauletta A, Leonardi L, et al. Muscle MRI in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM): implications for clinical management and treatment strategies. J Neurol. 2023;270(2):960-974. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNally AK, Anderson JM. Multinucleated giant cell formation exhibits features of phagocytosis with participation of the endoplasmic reticulum. Exp Mol Pathol. 2005;79(2):126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okazaki Y, Ohno H, Takase K, Ochiai T, Saito T. Cell surface expression of Calnexin, a molecular chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(46):35751-35758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007476200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanase K, Madaio MP. Nuclear localizing anti-DNA antibodies enter cells via caveoli and modulate expression of caveolin and p53. J Autoimmun. 2005;24(2):145-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2004.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mammen AL, Casciola-Rosen L, Christopher-Stine L, Lloyd TE, Wagner KR. Myositis-specific autoantibodies are specific for myositis compared to genetic muscle disease. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(6):e172. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeBose-Boyd RA. Feedback regulation of cholesterol synthesis: sterol-accelerated ubiquitination and degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Cell Res. 2008;18(6):609-621. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown MS, Radhakrishnan A, Goldstein JL. Retrospective on cholesterol homeostasis: the central role of scap. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87(1):783-807. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-011852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engelking LJ, Liang G, Hammer RE, et al. Schoenheimer effect explained—feedback regulation of cholesterol synthesis in mice mediated by Insig proteins. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(9):2489-2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI25614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marcoff L, Thompson PD. The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(23):2231-2237. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Langsjoen PH, Langsjoen AM. The clinical use of HMG CoA-reductase inhibitors and the associated depletion of coenzyme Q10. A review of animal and human publications. Biofactors. 2003;18(1-4):101-111. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banach M, Serban C, Sahebkar A, et al.; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration Group. Effects of coenzyme Q10 on statin-induced myopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(1):24-34. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor BA, Lorson L, White CM, Thompson PD. A randomized trial of coenzyme Q10 in patients with confirmed statin myopathy. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(2):329-335. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latkovskis G, Saripo V, Sokolova E, et al. Pilot study of safety and efficacy of polyprenols in combination with coenzyme Q10 in patients with statin-induced myopathy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2016;52(3):171-179. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qu H, Guo M, Chai H, Wang WT, Gao ZY, Shi DZ. Effects of coenzyme Q10 on statin-induced myopathy: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(19):e009835. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banach M, Serban C, Ursoniu S, et al.; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration LBPMC Group. Statin therapy and plasma coenzyme Q10 concentrations—a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. 2015;99:329-336. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dalakas MC. Autoimmune inflammatory myopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2023;195:425-460. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-98818-6.00023-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dalakas MC, Mammen AL. Case 22-2019: a 65-year-old woman with myopathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1693-1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1911058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.