Abstract

Background:

The incidence of self-harm and suicidal behaviour in adolescents is increasing. Considering the great impact in this population, an actualization of the evidence of those psychological treatment’s excellence for suicidal behaviour. Thus, the aim of this paper is to compile the available evidence on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy in preventing self-harm and suicidal behaviour in adolescents.

Methods:

A umbrella review was carried out, different databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Psyinfo, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar) were consulted. The 16-item measurement tool to assess systematic reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) were performed by two independent reviewers and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The Rayyan-Qatar Computing Research Institute was used for the screening process.

Results:

Nine systematic reviews were included. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy appears to reduce the incidence of suicide-related events compared with treatment as usual, compared to usual treatment (which usually consists of drugs and talk therapy) especially when combined with fluoxetine. Dialectical behavioural therapy seems to be associated with a reduction in suicidal ideation and self-harm.

Conclusions:

Although the results found show results with high heterogeneity. The evidence on cognitive behavioural therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy for suicide prevention, self-harm and suicide ideation in adolescents seems to show positive results. Considering, the special population and great impact, further research is needed and comparable studies should be sought that allow to set up robust recommendations.

Keywords: prevention, suicidal behaviour, self-harm, adolescence, cognitive-behavioural therapy

Introduction

Suicide is a major public health concern, since it has become the leading external cause of death in Spain in recent years and has reached record levels in 2022, with a mortality rate per 100,000 inhabitants of 183 in children under 15 years of age, and 4,533 between 15 and 29 years of age [1, 2, 3]. The prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm in adolescents is 17–18%, of which 70–93% have 3 or more episodes of recidivism [4]. In this regard, data on suicide should be analysed with caution, as there is under-reporting [5, 6].

Suicide comprises a number of terms, ranging from suicide, which is defined as death caused by a deliberate attempt to take one’s own life, to attempted suicide which is self-harm that is intended to result in death but does not [7]. Suicidal ideation is the thought process of having ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of completing suicide [8], as opposed to what we know as suicidal behaviour, which involves taking action. Self-harms refers to when a person intentionally harms himself or herself, whether it is a minor injury or not [9].

There is evidence of the strong relationship between both behaviors (non-suicidal self-harm and suicidal behaviors) and the predictive value of self-harm on suicidal risk, which makes any of them an important objective of psychological intervention [10].

Thus, it is important to bear in mind that adolescents are a population group with specific characteristics requiring a special approach and age-specific programmes [11]. Tailoring the message to the target audience is key in the prevention of suicide as this may encourage people with suicidal ideation to seek professional help [1, 6, 12]. In this sense, the cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) acts on the patient’s observable actions, their interaction with the environment and the way they think or feel, thus favouring the development of healthy and adaptive mental processes [5, 13, 14]. Similarly, the dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) combines the cognitive behavioural theory with Eastern meditative principles and practices to regulate emotions, behaviour and thoughts [15].

The suicide of a child tragically impacts the well-being and functioning of family members and this suffering goes beyond the physical and emotional morbidity [16], in addition to the significant number of years of life potentially lost. Hence, CBT and DBT may be optimal interventions to achieve suicide prevention amongst adolescents. This study aims to compile the available evidence on the effectiveness of CBT and DBT in treat of self-harm and suicidal behaviour in adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Design

An umbrella review (review of systematic reviews) was conducted following the recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for an overview of systematic reviews (OSRs) (PRIO-harms) tool [17]. The protocol was registered at the PROSPERO database, number CRD42022358474. The PRISMA 2020 checklist can be found as additional material in Supplementary Table 1.

Inclusion Criteria

Systematic reviews of CBT or DBT interventions in 13–18 year-old adolescents, published in English or Spanish between 2012 and 2022, were included. To enhance readability, results were organised according to type of therapy.

Search Strategy

The following databases were consulted: PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Psyinfo, Embase, Web of Science (WOS), Scopus and Google Scholar. References of the previously identified documents were revised. Searches were performed using a combination of free text and controlled vocabulary terms (Suicid* AND (Adolescen* OR teenager* OR teen* OR young OR youth) AND (Program* OR plan* OR strateg* OR prevention OR trial* OR intervention*) AND “Cognitive behavioral therapy” AND Effectiveness AND (“Systematic review” OR “meta-analysis” OR “metaanalysis”)). To limit the results to systematic reviews we used the search filter designed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [18]. The search was adapted to the language of the other sources consulted. All this was validated by a librarian specialised in public health.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

This umbrella review allows the identification of multiple articles that synthesize the evidence from systematic reviews in which the same intervention and the same problem are involved, but different results are obtained, making it useful to easily contrast the different findings of these.

Two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts (first selection) of each review was checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria before requesting the full text. Likewise, these were then independently assessed in full text (second selection). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between reviewers. When two reviews were found with the same research question, the most updated reference was included, and the one that included the largest number of studies amongst its results.

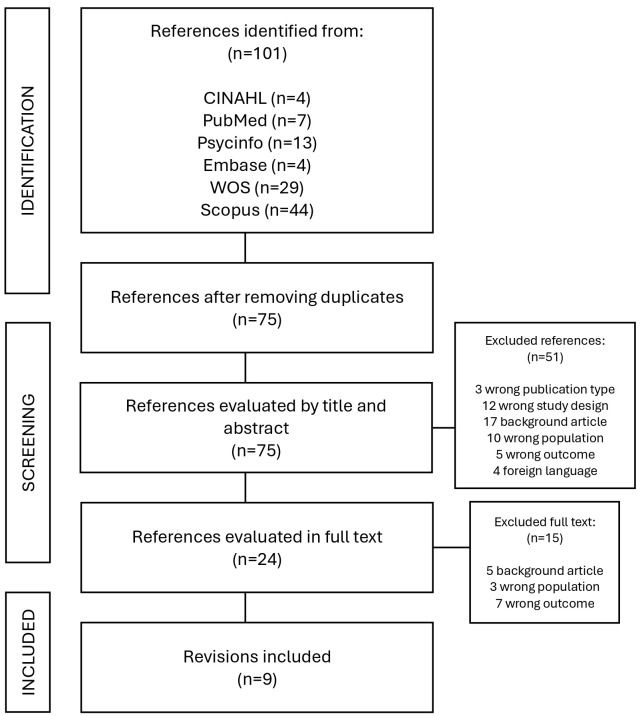

Data extraction was carried out by a researcher using an ad-hoc form designed and validated by the second reviewer (variables considered: population, comparison, methods, no. studies included, results and conclusion). Screening was done using the Rayyan-Qatar Computing Research Institute software (https://www.rayyan.ai/) application for systematic literature reviews. The process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection process.

Risk of Bias

The 16-item measurement tool to assess systematic reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) was used to assess the risk of bias, which was carried out independently by two assessors [19]. Extracted data and results from the quality appraisal were compiled with conflicts resolved through discussion by the reviewers.

Results

The search identified 101 references. After carrying out the selection process, a total of 9 systematic reviews were finally included. Main characteristics of these reviews are shown in Table 1 (Ref. [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included reviews.

| Author (year) | Population | Comparison | Methods | No. studies included | Results | Conclusion |

| Bahji et al. (2021) [20] | Children and adolescents (10–19 years) | Psychosocial interventions for the treatment of self-harm and suicidal behaviour | Search: PubMed, MedLine, PsycINFO and Embase until 2020. Inclusion criteria: RCT, comparison of psychotherapies for suicide and self-harm prevention. | 44 RCTs (5406 participants) | Cognitive behavioural therapy did not show a significant reduction in suicidal ideation (mean deviation (MD) –0.21; 95% confidence interval (CI): –1.63 to 1.21) or self-harm (MD 0.6; 95% CI: 0.31 to 1.19). | Most psychotherapies were reasonably well tolerated and some psychotherapies indicated efficacy for particular measures of self-harm or suicidality. |

| Dialectical behavioural therapies were associated with reductions in self-harm (odds ratio (OR) 0.28; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.64) and suicidal ideation (weigthed mean difference (WMD) −0.71; 95% CI: –1.19 to –0.23). Mentalization-based therapies were associated with decreases in self-harm (OR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.97) and suicidal ideation (WMD –1.22; 95% CI: –2.18 to –0. 26). | ||||||

| Witt et al. (2021) [21] | Children and adolescents (18 years old) with a history of self-harm | Psychosocial or pharmacological interventions for self-harm | Search: Cochrane Specialized Register of Common Mental Disorders, Cochrane Library, Central, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid and PsycINFO Ovid. | 17 RCTs (2280 participants) | No significant differences were found between CBT and other psychological intervention in the repetition of self-harm (OR 0.93; 95% CI: 0.12 to 7.24), nor between the psychological intervention and pharmacotherapy in suicidal ideation (OR 0.26; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.98) in minors with depression. | Younger people have cognitive, behavioural and emotional characteristics different from adults, and these should be taken into account in order to make age-specific innovations in the design and content of interventions. |

| Regarding DBT compared to usual treatment, a decrease was found in the repetition of self-harm (OR 0.46; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.82) and suicidal ideation (standardized mean difference (SMD): –0.43; 95% CI: –0.68 to –0.18). | Studies consider that the most important predictor is a previous event of suicidal behaviour. | |||||

| TBM was associated with a non-significant reduction in repetition of self-harm (OR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.06 to 8.46) compared to usual treatment. | ||||||

| Cox et al. (2014) [22] | Minors (18 years old) diagnosed with depressive disorder | Psychological therapies and antidepressant medication | Search: Cochrane, MedLine, Embase and PsycINFO until 2012. Inclusion criteria: RCT with minors diagnosed with depression. | 11 RCTs (1307 participants) | Cognitive behavioural therapy did not show significant differences between groups in suicidal ideation (MD 0.60; 95% CI: –2.25 to 3.45), at 6–9 months (MD 1.78; 95% CI: –2.29 to 5.85) or at one year (MD 0.90; 95% CI: –1.37 to 3.17). In two trials, psychotherapy decreased suicidal ideation compared to medication (OR 0.26; 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.72) (MD –3.12; 95% CI: –5.91 to –0.33), this effect remained at 6–9 months (OR 0.26; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.98), but not at one year (p 0.05). | Psychological therapy may be associated with less suicidal ideation. A combination of treatments could protect against suicidality. There is great variability within the data. Additional data is needed. |

| There were no differences between combined therapy and psychotherapy (OR 1.68; 95% CI: 0.53 to 5.34), nor between combined therapy and psychotherapy plus placebo (p 0.05). No results were shown on self-harm. | ||||||

| Mann et al. (2021) [23] | Population with suicidal behaviour or ideation | Scalable, evidence-based suicide prevention strategies | Search: PubMed and Google Scholar between 2005–2019. Inclusion criteria: RCTs and studies on limitation of access to lethal means, educational approaches and antidepressants | 97 RCTs and 30 epidemiological studies | Cognitive behavioural therapy decreased the risk of suicidal behaviour in adolescents with depression. CBT reduced suicide attempts in patients presenting to the emergency department after a suicide attempt and in substance use disorders compared to TAU. No results were reported on self-harm. | CBT is a proven scalable strategy for suicide prevention. |

| Xiang et al. (2022) [24] | Minors (18 years old) diagnosed with depressive disorder | Combined therapy | Search in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, WOS, CINAHL, LiLACS and ProQuest until 2020. Inclusion criteria: RCTs on pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. | 14 RCTs (1325 participants) | Treatment with fluoxetine plus CBT did not have a significant effect for suicidality (suicidal ideation or attempt/behaviour) (OR 1.17; 95% CI: 0.67 to 2.06). Children under 25 years of age treated with antidepressants are more likely to develop suicidal thoughts than adults, especially when treated with venlafaxine. No results were reported on self-harm. In those 16 years of age, the dropout rate was higher. | Despite the limited evidence, therapies combined with CBT may be superior to other active treatment options, although other psychotherapies were not included in the study. Combined therapies have poorly been studied in this age group. |

| Ma et al. (2014) [25] | Minors with a diagnosis of depressive disorder | Contemporary interventions for depressive disorder in children and adolescents | Search: Cochrane, CINAHL, EMBASE, LiLACS, MedLine, PSYCINFO and PSYNDEX until 2014. Inclusion criteria: RCT, antidepressants, CBT, fluoxetine combined with CBT and placebo, acute treatment of major depressive disorder. | 21 RCTs (4969 participants) | CBT decreased suicidal ideation compared to fluoxetine (OR 1.88; 95% CI: 1.41 to 2.50). The cumulative odds of the combination therapy of fluoxetine plus CBT was the most effective treatment (95.2%), but it was worse tolerated than placebo and its acceptability was inferior to the use of other antidepressants. No significant differences were found between fluoxetine and the combination therapy (OR 0.77; 95% CI: 0.59 to 1.00). No results of self-harm were reported. | CBT showed lower efficacy, acceptability and safety than the rest and was considered relatively less useful as a first-line treatment. The combination therapy showed the greatest efficacy, although safety remained a major concern. Further research is needed. |

| Zhou et al. (2020) [26] | Minors with a diagnosis of depressive disorder | Interventions and treatments available for depressive disorder in children and adolescents | Search: PubMed, Embase, LiLACS, CINAHL, PsycINFO, WOS, Cochrane and ProQuest until 2019. Inclusion criteria: RCTs, acute treatment, 18 years old with depression. | 71 RCTs (9510 participants) | The combined therapy of fluoxetine plus CBT was more effective for the prevention of suicidality (OR 0.13; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.59). Venlafaxine was associated with a significantly higher risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour (OR 8.31; 95% CI: 1.92 to 343.17). No results of self-harm were reported. | Psychotherapies were superior to control group, but more research is required as these therapies were adaptations of treatments developed for adults. |

| Most RCTs of psychotherapy were assessed as having a high risk of bias and had lower dropout rates and baseline severity scores than RCTs of pharmacotherapy. | ||||||

| Frías et al. (2015) [27] | Patients (parents or minors) with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I, II, non-specific) | Psychosocial treatments in pediatric bipolar disorder | Search: PsycINFO and PubMed until 2014. Inclusion criteria: Minors 6–19 years old with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. | 4 case studies, 9 open trials, 7 RCTs, 8 systematic reviews and 5 theoretical trials (606 patients) | At 2-month follow-up, CBT showed a reduction in depressive symptoms, including suicidal behaviour. DBT showed a 3-fold greater reduction in suicidal ideation compared to TAU. No results of self-harm were reported. | Research on CBT for suicide prevention is scarce and evidence insufficient. DBT seems promising in this area and findings need to be replicated in larger samples. |

| Ougrin et al. (2015) [28] | Minors 18 years of age with a history of self-harm | Pharmacological, social and psychological interventions for self-harm in adolescents | Search: Cochrane, MedLine, PubMed, PsycINFO and EMBASE until 2014. Inclusion criteria: RCT, comparison with TAU or placebo, with self-harm | 19 RCTs (2176 participants) | There were no significant differences in suicide attempts (risk difference: –0.03; 95% CI: –0.09 to 0.03) between therapies. | Improving adherence to treatment seems key to reducing the risk of self-harm and suicide. Although the pooled effectiveness of the interventions versus TAU was significant, there is a high heterogeneity across studies. Further research is therefore needed. |

| The pooled risk difference for any self-harm was –0.07 (95% CI: –0.01 to –0.13). The NNT was 21 (95% CI: 11.2 to 98.5) at 10 months. For non-suicidal self-harm there was a non-significant risk reduction (risk difference: –0.1; 95% CI: –0.21 to 0.00) compared to TAU. Furthermore, studies with a strong family component (risk difference: –0.14; 95% CI: –0.27 to –0.02) or with multiple sessions (risk difference: –0.09; 95% CI: –0.017 to 0.00) were associated with a significant reduction in self-harm. DBT showed a significant reduction in the risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation. |

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; DBT, dialectical behavioural therapy; TAU, usual treatment; RCT, randomized clinical trial; DM, mean difference; SMD, standardized mean difference; NNT, Number Needed to Treat; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. Suicidality includes suicidal ideation or attempt/behaviour.

Bias Risk Assessment

Table 2 (Ref. [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]) shows the assessment of risk of bias. Overall, the included systematic reviews show a high risk of bias. It should be highlighted that several reviews did not include a list of excluded articles and did not refer to the existence of any protocol prior to the conduction of the review. On the other hand, almost all the reviews conducted an exhaustive literature search, described the Problem/Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) question (item 1) and described their potential conflicts of interest (item 16).

Table 2.

Risk of bias rating of included reviews using the 16-item measurement tool to assess systematic reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) tool.

| Item | Bahji et al. (2021) [20] | Witt et al. (2021) [21] | Cox et al. (2014) [22] | Mann et al. (2021) [23] | Xiang et al. (2022) [24] | Ma et al. (2014) [25] | Zhou et al. (2020) [26] | Frías et al. (2015) [27] | Ougrin et al. (2015) [28] |

| 1 | + | + | + | × | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | – | + | – | × | + | × | + | × | × |

| 3 | × | + | + | + | × | × | × | + | × |

| 4 | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – |

| 5 | + | + | + | × | + | + | + | × | + |

| 6 | + | + | + | × | + | + | + | × | + |

| 7 | × | + | – | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| 8 | × | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – |

| 9 | – | + | + | × | + | + | + | × | + |

| 10 | × | + | + | × | × | + | + | × | × |

| 11 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + |

| 12 | × | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + |

| 13 | × | + | + | × | + | + | + | × | + |

| 14 | × | + | + | × | + | + | + | + | + |

| 15 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + |

| 16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Critically low | High | High | Critically low | Low | Critically low | Low | Critically low | Critically low |

Rating overall confidence in the results of the review: High: the systematic review provides an accurate and comprehensive summary of the results of the available studies that address the question of interest. Low: the review has a critical flaw and may not provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies that address the question of interest. Critically low: the review has more than one critical flaw and should not be relied on to provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies. +, Yes; ×, NO; –, Partial yes; ?, No Meta-Analysis conducted.

Results according to Type of Intervention

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Bahji et al.’s review [20] (2021) found no significant difference between CBT and treatment as usual in suicidal ideation (standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.21; 95% confidence interval (CI): –1.63 to 1.21) amongst children and adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. Likewise, Witt et al. [21] (2021) found no significant difference for CBT compared with another psychological intervention in the repetition of self-harm (odds ratio (OR) 0.93; 95% CI: 0.12 to 7.24), nor between psychological intervention and pharmacotherapy in suicidal ideation (OR 0.26; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.98) in minors with depression.

A Cochrane review included 11 clinical trials, in adolescents with depression, evaluating the effectiveness of psychological therapies (therapy in nine trials included individual CBT sessions, and in two trials group sessions). With regards to suicide, a study (n = 188) showed a significantly lower incidence of suicide-related events in those who received psychological interventions compared to those with pharmacological interventions [fluoxetine] (OR 0.26; 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.72) [22]. Attention should also be drawn to Mann et al.’s review [23] (2021) showing that CBT reduced the risk of suicidal behaviour in adults and adolescents with depression, and halved the rate of suicide reattempt in patients presenting to an emergency department following a recent suicide attempt compared with treatment as usual.

Combined Therapy (CBT and Pharmacotherapy)

Xiang et al.’s review [24] (2022) evaluated the combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for children and adolescents with acute depressive disorders against other treatment options. No significant difference was found in the number of patients reporting suicidal ideation or suicidal attempt/behaviour (OR 1.17; 95% CI: 0.67 to 2.06; n = 932). It should be highlighted that the combination of fluoxetine (OR 1.90; 95% CI: 1.10 to 3.29) or non-selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors antidepressants (OR 2.46; 95% CI: 1.06 to 5.72) was superior to other treatment options [24]. Similar results have been described by Ma et al. [25] (2014) in adolescents with major depression. Patients receiving the combination of antidepressant (fluoxetine) and CBT showed lower suicidal ideation (95.2%), followed by fluoxetine (2.2%), mirtazapine (1.2%), sertraline (0.6%) and (0.2%) paroxetine, citalopram and venlafaxine (0.2%) [25].

In contrast, Zhou et al.’s review [26] (2020) showed that the combination therapy of fluoxetine and CBT was significantly more effective than placebo in preventing suicidality in adolescents (OR 0.13; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.59).

Alternative Therapies to CBT: Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT)

Witt et al.’s Cochrane review [21] (2021) included four clinical trials (n = 270 participants) comparing DBT with treatment as usual. The review shows a decrease in the repetition of self-harm (OR 0.46; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.82) and suicidal ideation (SMD –0.43; 95% CI: –0.68 to –0.18) [21]. In the 10–19 year-old population group, Bahji et al. [20] (2021) found significant reductions in self-harm (OR 0.28; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.64) and suicidal ideation (SMD –0.71; 95% CI: –1.19 to –0.23) with DBT compared to treatment as usual.

Frías et al.’s review [27] (2015) in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder examined 20 references on psychological interventions, including an open trial (n = 10) and a controlled clinical trial (n = 14), and found that those on DBT showed a significant improvement in the frequency of suicidal ideation.

Lastly, the review by Ougrin et al. [28] (2015) included a study showing significant differences following DBT delivered by psychotherapists who underwent lengthy training with ongoing supervision, which may also influence the effectiveness of psychotherapy as these interventions offer greater variability than the administration of a drug.

Discussion

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy appears to deliver better results than treatment as usual or placebo, particularly when CBT is part of the combined therapy with fluoxetine [29, 30, 31]. In this regard, antidepressant therapy in adolescents should be indicated with caution since several studies have evidenced an increased risk for developing suicidal behaviours in adolescents. Hence, scientific literature shows children and adolescents undergoing antidepressant therapy are associated with a higher likelihood of developing suicidal thoughts, ideation and behaviour, and this association was particularly significant with venlafaxine [24, 26, 30].

The fact that this is a particularly vulnerable population, the low number of studies and participants, the majority of the included review were rated as low or critically low, together with the lack of comparisons between the different interventions, means that caution must be taken in offering a robust recommendation on the type of intervention to be carried out.

It should be noted that most of the interventions evaluated are adaptations of treatments developed for adults and applied to adolescents with minimal adaptations. However, younger people have cognitive, behavioural and emotional characteristics different from adults and it is believed that implementing age-specific innovations in the designs and contents of interventions would yield better outcomes. In addition, interventions should be developed in collaboration with this age-specific patients to ensure their needs are met [21]. Adolescents may be exposed to stressful life situations that may strongly influence their mental health and for which they usually do not yet have the necessary coping skills or resources to deal with. Similarly, the consumption of alcohol and drugs, starting at increasingly younger ages, raises the potential risk of suicidal behaviour [21, 31].

The last decade has seen a significant increase in cyberbullying amongst children and adolescents from digitalised countries worldwide. Scientific literature shows a prevalence of cybervictimisation of 2% to 57%, with an average prevalence of 23%. Cyberbullying is associated with a 2.23-fold increase in the risk of suicidal ideation and a 2.55-fold increase in the risk of suicidal behaviour compared to those who have not been cyberbullied. Even bullies report more suicidal ideation and behaviour, although at a lower rate than victims [32, 33, 34, 35].

A diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive disorder is a risk factor that influences the severity of suicidal ideation and behaviour [36]. Thus, it seems reasonable that young people with mental health issues should be offered any kind of psychological intervention. The review by Ougrin et al. [28] (2015) compared the psychological intervention, which included psychological and social interventions and no pharmacological intervention, and found an absolute risk reduction for any self-harm -including suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-harm and/or self-harm with ambiguous intent- (Absolute risk reduction 4.99%; 95% CI: 1.01% to 8.97%; Number Needed to Treat (NNT) 21; 95% CI: 11.2 to 98.5), with a NNT of 10, in 10 months, for non-suicidal self-harm. Meta-regression analyses found no significant association between effect size and the different characteristics of the study (number of sessions, quality of the study, proportion of women, etc.) [28].

The results show that CBT is associated with a reduction in the risk of repeating the suicide attempt [23, 24]. However, A study considers that the most important predictor is the occurrence of a repeated episode of suicidal behaviour (self-harm or suicide attempt) [21].

It should be stressed that the mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) has shown promising outcomes. Thus, the review from Witt et al. [21] (2021) found that MBT was associated with a non-significant reduction in the repetition of self-harm compared to treatment as usual. The lack of significance might be due to the low number of subjects evaluated (n = 85) [21]. Similarly, in the 10 to 19 year-old population, a reduction was found in self-harm (OR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.97) and suicidal ideation (SMD –1.22; 95% CI: –2.18 to –0.26) compared to treatment as usual [20].

Carrasco et al.’s umbrella review [10] (2023) aimed to determine the effectiveness of different psychological interventions in relation to autolytic events in the adolescent population. The review concluded that this type of therapies shows a significant effectiveness, despite their small to medium effect sizes, for self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Furthermore, these effects weakened in the medium to long term and even tended to disappear [10].

Finally, in order to also consider the structural approach, it has been noted that educational centres, such as primary and secondary schools, can be a great resource for improving the mental health of children and adolescents. Moreover, they have the opportunity to involve the family in the interventions, which is particularly interesting as in many cases therapies are more effective when there is a strong family component. Schools have been shown to be very safe environments and, although interventions have not proved a beneficial effect for young people, they have not been shown to be harmful [37].

Conclusions

The paucity of literature on the prevention of self-harm and suicide in adolescents is therefore striking. This, together with the high risk of systematic reviews for bias and results heterogeneity, highlights the need for further research on preventing suicide in adolescents and related factors (psychological factors in the aetiopathogenesis of the disorder) to design improved interventions [20, 21, 26, 28]. On the other hand, there is a lack of studies that compare interventions in group format versus individual ones or CBT vs DBT. Therefore, it would be advisable to carry out studies that evaluate their comparative effectiveness.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Begoña Martínez Vázquez for the translation of this article into English and Camila Higueras for the magnificent work on the literature search. This work have been incorporated into the Andalusian School of Public Health’s (Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública) curriculum for its Master’s degree in Public Health and Health Management.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.62641/aep.v52i4.1631.

Availability of Data and Materials

A complete list of primary and secondary search citations is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CT and AO designed the research study. CT conducted the research. AO provided help and advice on the study methodology. CT analyzed the data. CT and AO wrote this manuscript. Both authors contributed to important editorial changes to the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The author for the correspondence on behalf of the other signatories guarantees the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study; that no relevant information has been omitted; and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and qualified. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Suárez Alonso AG. Estrategia de salud mental del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Periodo 2022-2026 - Confederación Salud Mental España. 2022. [(Accessed: 2 December 2022)]. Available at: https://consaludmental.org/centro-documentacion/estrategia-salud-mental-2022-2026/ In Spanish.

- [2].Harold Koplewicz MD. La evidencia avala la eficacia de la Terapia Cognitivo-Conductual en una amplia variedad de trastornos en la adolescencia, según un informe. Infocop Online. 2017. [(Accessed: 2 December 2022)]. Available at: https://www.infocop.es/view_article.asp?id=7090. In Spanish.

- [3].Tasa de mortalidad por suicidio por comunidad autónoma, edad, sexo y periodo. 2022. [(Accessed: 18 May 2024)]. Available at: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?tpx=46688. In Spanish.

- [4].Mollà L, Batlle Vila S, Treen D, López J, Sanz N, Martín LM, et al. Autolesiones no suicidas en adolescentes: revisión de los tratamientos psicológicos. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica . 2015;20:51–61. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- [5].Arenas Rodríguez D. Eficacia de la Terapia Cognitivo Conductual para la conducta suicida de adolescentes con depression. Psicoevidencias—Portal de gestión del conocimiento del Programa de Salud Mental de Andalucía. Psicoevidencias . 2021 In Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vivir la vida. Guía de aplicación para la prevención del suicidio en los países. Organización Panamericana de la Salud: Washington, D.C. 2021. [(Accessed: 2 December 2022)]. Available at: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/54718. In Spanish.

- [7].Suicidio MedlinePlus en español. 2020. [(Accessed: 9 January 2023)]. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/spanish/ency/article/001554.htm. In Spanish.

- [8].ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. [(Accessed: 19 May 2024)]. Available at: https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#778734771. In Spanish.

- [9].Cañón Buitrago SC, Carmona Parra JA. Ideación y conductas suicidas en adolescentes y jóvenes. Pediatría Atención Primaria . 2018;20:387–397. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- [10].Carrasco MÁ, Carretero EM, López-Martínez LF, Pérez-García AM. Eficacia de los tratamientos psicológicos para los comportamientos autolesivos suicidas y no suicidas en adolescentes. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes . 2023;10:53–67. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ospina Gutiérrez ML, Ulloa Rodriguez MF, Ruiz Moreno LM. Non-suicidal self-injuries in adolescents: Prevention and detection in primary care. Semergen . 2019;45:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2019.02.010. (In Spanish) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fundación Española para la Prevención del Suicidio. Observatorio del Suicidio en España. 2020. [(Accessed: 9 January 2022)]. Available at: https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio/ In Spanish.

- [13].Santa Cecilia T. La terapia cognitivo-conductual aplicada a casos de ideación suicida. Psicología y Mente. 2020. [(Accessed: 11 January 2023)]. Available at: https://psicologiaymente.com/clinica/terapia-cognitivo-conductual-ideacion-suicida. In Spanish.

- [14].Puntí Vidal J, Gracia Liso R, Torralbas Ortega J. Intervención psicoterapéutica en la prevención del suicidio: diez años de experiencia práctica. XXI Congreso Virtual Internacional de Psiquiatría, Psicología y Enfermería en Salud Mental . 2020 In Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- [15].McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, et al. Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents at High Risk for Suicide: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry . 2018;75:777–785. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vig PS, Lim JY, Lee RWL, Huang H, Tan XH, Lim WQ, et al. Parental bereavement - impact of death of neonates and children under 12 years on personhood of parents: a systematic scoping review. BMC Palliative Care . 2021;20:136. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00831-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, Ntzani E, Haidich AB. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology . 2018;93:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Search filters Healthcare Improvement Scotland. SIGN. 2021. [(Accessed: 1 November 2022)]. Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/search-filters/ In Spanish.

- [19].Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ . 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bahji A, Pierce M, Wong J, Roberge JN, Ortega I, Patten S. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Psychotherapies for Self-harm and Suicidal Behavior Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open . 2021;4:e216614. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Witt KG, Hetrick SE, Rajaram G, Hazell P, Taylor Salisbury TL, Townsend E, et al. Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2021;3:CD013667. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013667.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, et al. Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2014;2014:CD008324. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mann JJ, Michel CA, Auerbach RP. Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of Psychiatry . 2021;178:611–624. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xiang Y, Cuijpers P, Teng T, Li X, Fan L, Liu X, et al. Comparative short-term efficacy and acceptability of a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry . 2022;22:139. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03760-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ma D, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Li L. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and safety of medicinal, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and placebo treatments for acute major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Current Medical Research and Opinion . 2014;30:971–995. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.860020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, Del Giovane C, Furukawa TA, Weisz JR, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry . 2020;7:581–601. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Frías Á, Palma C, Farriols N. Intervenciones psicosociales en el tratamiento de los jóvenes diagnosticados o con alto riesgo para el trastorno bipolar pediátrico: una revisión de la literatura. The Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health . 2015;8:146–156. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . 2015;54:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fonseca-Pedrero E, Pérez-Álvarez M, Al-Halabí S, Inchausti F, López-Navarro ER, Muñiz J, et al. Empirically Supported Psychological Treatments for Children and Adolescents: State of the Art. Psicothema . 2021;33:386–398. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2021.56. (In Spanish) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Calear AL, Christensen H, Freeman A, Fenton K, Busby Grant J, van Spijker B, et al. A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry . 2016;25:467–482. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0783-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fundación Save the Children Suicidios en adolescentes en España: factores de riesgo y datos. 2022. [(Accessed: 11 January 2023)]. Available at: https://www.savethechildren.es/actualidad/suicidios-adolescentes-espana-factores-riesgo-datos. In Spanish.

- [32].Expósito D. El suicidio entre los jóvenes. El País. 2022. [(Accessed: 1 February 2023)]. Available at: https://elpais.com/opinion/2022-01-26/el-suicidio-entre-los-jovenes.html. In Spanish.

- [33].Teen Suicide Stanford MEDICINA— Children’s Health. 2022. [(Accessed: 1 February 2023)]. Available at: https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=teen-suicide-90-P02584. In Spanish.

- [34].Dorol-Beauroy-Eustache O, Mishara BL. Systematic review of risk and protective factors for suicidal and self-harm behaviors among children and adolescents involved with cyberbullying. Preventive Medicine . 2021;152:106684. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].John A, Glendenning AC, Marchant A, Montgomery P, Stewart A, Wood S, et al. Self-Harm, Suicidal Behaviours, and Cyberbullying in Children and Young People: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research . 2018;20:e129. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Leigh E, Chiu K, Ballard ED. Social Anxiety and Suicidality in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology . 2023;51:441–454. doi: 10.1007/s10802-022-00996-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Caldwell DM, Davies SR, Hetrick SE, Palmer JC, Caro P, López-López JA, et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry . 2019;6:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A complete list of primary and secondary search citations is available upon request from the corresponding author.