Key Points

Question

What is the association of tirzepatide vs glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) treatment with all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular or kidney events in US patients with type 2 diabetes?

Findings

In this cohort study of 140 308 patients with type 2 diabetes, treatment with tirzepatide was associated with significantly lower hazards of all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events compared with GLP-1 RA.

Meaning

These findings suggest that treatment with tirzepatide may confer additional clinical benefits for patients with type 2 diabetes.

This cohort study investigates the risks of mortality and adverse cardiovascular and kidney outcomes among individuals with type 2 diabetes taking tirzepatide vs glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists.

Abstract

Importance

Despite its demonstrated benefits in improving cardiovascular risk profiles, the association of tirzepatide with mortality and cardiovascular and kidney outcomes compared with glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) remains unknown.

Objective

To investigate the association of tirzepatide with mortality and adverse cardiovascular and kidney outcomes compared with GLP-1 RAs in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used US Collaborative Network of TriNetX data collected on individuals with type 2 diabetes aged 18 years or older initiating tirzepatide or GLP-1 RA between June 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023; without stage 5 chronic kidney disease or kidney failure at baseline; and without myocardial infarction or ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke within 60 days of drug initiation.

Exposures

Treatment with tirzepatide compared with GLP-1 RA.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, and secondary outcomes included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), the composite of MACEs and all-cause mortality, kidney events, acute kidney injury, and major adverse kidney events. All outcomes were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Results

There were 14 834 patients treated with tirzepatide (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [11.8] years; 8444 [56.9%] female) and 125 474 treated with GLP-1 RA (mean [SD] age, 58.1 [13.3] years; 67 474 [53.8%] female). After a median (IQR) follow-up of 10.5 (5.2-15.7) months, 95 patients (0.6%) in the tirzepatide group and 166 (1.1%) in the GLP-1 RA group died. Tirzepatide treatment was associated with lower hazards of all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.45-0.75), MACEs (AHR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71-0.91), the composite of MACEs and all-cause mortality (AHR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), kidney events (AHR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.37-0.73), acute kidney injury (AHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.88), and major adverse kidney events (AHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.67). Treatment with tirzepatide was associated with greater decreases in glycated hemoglobin (treatment difference, −0.34 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.44 to −0.24 percentage points) and body weight (treatment difference, −2.9 kg, 95% CI, −4.8 to −1.1 kg) compared with GLP-1 RA. An interaction test for subgroup analysis revealed consistent results stratified by estimated glomerular filtration rate, glycated hemoglobin level, body mass index, comedications, and comorbidities.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, treatment with tirzepatide was associated with lower hazards of all-cause mortality, adverse cardiovascular events, acute kidney injury, and adverse kidney events compared with GLP-1 RA in patients with type 2 diabetes. These findings support the integration of tirzepatide into therapeutic strategies for this population.

Introduction

Cardiovascular and kidney diseases are prevalent in patients with diabetes, causing substantial morbidity and mortality.1,2,3 Many hypoglycemic agents have been evaluated for cardiovascular and kidney protection beyond their originally designed hypoglycemic effects.4 Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) were found to improve kidney and cardiovascular outcomes,5,6 with new trials ongoing and results emerging.

Tirzepatide, a dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) RA, was developed in view of the synergistic effect of both receptors in achieving negative energy balance besides facilitating glucose-dependent insulin secretion.7 Studies have shown tirzepatide’s superiority over semaglutide in reducing glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and weight (additional reductions of 0.15-0.45 percentage points in HbA1c and 1.9-5.5 kg in body weight) in patients with type 2 diabetes.8 Compared with insulin glargine, tirzepatide has been shown to ameliorate annual estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline by 2.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 and to reduce the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio by 31.9%.9,10 Favorable effects on additional cardiovascular risk factors, including atherogenic lipoproteins and blood pressure, were also observed with tirzepatide compared with semaglutide (increase of 6.8%-7.9% vs 4.4% in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, decrease of 17.5%-23.7% vs 11.1% in very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and decrease of 4.8-6.5 mm Hg vs 3.6 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure).8 However, whether these metabolic improvements lead to benefits in survival and kidney or cardiovascular outcomes remains unclear.

One meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) reported noninferiority of tirzepatide for cardiovascular safety compared with the control groups,11 though the included studies were highly heterogenous regarding their comparators (ie, placebo, insulin, GLP-1 RA) and trial participant characteristics, thus precluding a solid conclusion.11 Notably, there is a lack of studies directly comparing tirzepatide with GLP-1 RAs, thereby necessitating further investigation in this context. Hence, we investigated the association of tirzepatide with mortality and adverse cardiovascular and kidney outcomes compared with GLP-1 RAs in US patients with type 2 diabetes.

Method

Data Source

This cohort study used data from the TriNetX database, which collects deidentified, patient-level data from electronic health records. Information in the TriNetX database comes from health care organizations (HCOs), typically academic health care centers, that collect data from their main and satellite hospitals and outpatient clinics. Available data include demographics, diagnoses (based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes), procedures (classified by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Procedure Coding System or Current Procedural Terminology), medications (Veterans Affairs Drug Classification System and RxNorm codes), laboratory tests (organized using Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes), and health care utilization records. We used the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX, which includes data from more than 100 million patients from 62 HCOs in the US.

Patient-level data were analyzed using the built-in statistical tool on the TriNetX platform, which is based on Java, version 11.0.16 (Oracle); R, version 4.0.2 (with packages Hmisc, version 4.1-1 and Survival, version 3.2-3) (R Project for Statistical Computing); and Python, version 3.7 (with the libraries lifelines, version 0.22.4; matplotlib, version 3.5.1; numpy, version 1.21.5; pandas, version 1.3.5; scipy, version 1.7.3; and statsmodels, version, 0.13.2) (Python Software Foundation), with the outputs validated using independent, industry-standard methods. The results were provided to investigators in summarized format. Details regarding the database can be found online12 and as previously described.13,14

Ethical approval for using the TriNetX database in this study was granted by Chi Mei Hospital’s institutional review board, and institutional review boards from all hospitals involved. Informed consent was waived because this study was conducted using only aggregated statistical summaries of deidentified information. This study was conducted adhering to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki15 and adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

Patients aged 18 years or older with type 2 diabetes and prescribed tirzepatide or a GLP-1 RA during June 1, 2022, through June 30, 2023, were included because tirzepatide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on May 13, 2022. Individuals with acute myocardial infarction, intracranial hemorrhage, or cerebral infarction within 60 days before the index prescription date were excluded to avoid misidentifying incident outcomes. The patients were divided into tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA groups, excluding those previously given medications from the counterpart groups (ie, GLP-1 RA for the tirzepatide group and tirzepatide for the GLP-1 RA group) within 6 months before or any time after the index prescription. To achieve an incident user design, patients with prior use of a GLP-1 RA or tirzepatide before the index date were excluded. To mitigate misinterpretation, individuals with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), or receiving dialysis at baseline were excluded from the major adverse kidney event (MAKE) outcome analysis.

We conducted 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) that involved 48 variables covering demographics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory results. Patients in both groups were followed for a maximum of 21 months or until data analysis on May 2, 2024. Details regarding the codes used to identify the demographics, diagnoses, procedures, medications, and laboratory results are provided in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.

Covariates

Covariate selection was guided by clinical relevance, encompassing major comorbidities and risk factors that could contribute to mortality, cardiovascular or kidney outcomes, and baseline health status in accordance with current knowledge. We considered the following variables to adjust for imbalances in baseline characteristics between the tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA groups: age; sex; race and ethnicity (as documented in the electronic health record); cardiovascular disease; dementia; chronic lower-respiratory disease; autoimmune disease; CKD; chronic hepatitis; liver cirrhosis; anemia; HIV; neoplasms; socioeconomic status and psychosocial-related health hazards; diabetic complications; and medicines including diuretics, lipid-lowering agents, hypoglycemic agents, and hypotensive agents. We further adjusted for body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, HbA1c, and eGFR. Additional details on the categorization and codes adopted to define the covariates are provided in Table 1 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups Before and After Propensity Score Matching.

| Characteristic | Before matching, No. (%) | After matching, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide (n = 14 834) | GLP-1 RA (n = 125 474) | Standardized difference | Tirzepatide (n = 14 832) | GLP-1 RA (n = 14 832) | Standardized difference | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55.4 (11.8) | 58.1 (13.3) | 0.213 | 55.4 (11.8) | 55.5 (13.3) | 0.004 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 8444 (56.9) | 67 474 (53.8) | 0.064 | 8444 (56.9) | 8436 (56.9) | 0.001 |

| Male | 5563 (37.5) | 53 326 (42.5) | 0.106 | 5563 (37.5) | 5577 (37.6) | 0.008 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| African American or Black | 2517 (17.0) | 25 212 (20.1) | 0.088 | 2517 (17.0) | 2469 (16.6) | 0.009 |

| Asian | 337 (2.3) | 4558 (3.6) | 0.080 | 337 (2.3) | 355 (2.4) | 0.008 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 957 (6.5) | 11 676 (9.3) | 0.106 | 957 (6.5) | 906 (6.1) | 0.014 |

| White | 9978 (67.3) | 75 762 (60.4) | 0.144 | 9978 (67.3) | 10 052 (67.8) | 0.011 |

| Othera | 466 (3.1) | 3137 (2.5) | 0.092 | 466 (3.1) | 451 (3.0) | 0.003 |

| Unknown | 579 (3.9) | 5129 (4.1) | 0.026 | 579 (3.9) | 599 (4.0) | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 8265 (55.7) | 72 438 (57.7) | 0.041 | 8265 (55.7) | 8149 (54.9) | 0.016 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1623 (10.9) | 16 814 (13.4) | 0.075 | 1623 (10.9) | 1588 (10.7) | 0.008 |

| Heart failure | 821 (5.5) | 9447 (7.5) | 0.081 | 821 (5.5) | 736 (5.0) | 0.026 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 670 (4.5) | 7334 (5.8) | 0.060 | 670 (4.5) | 685 (4.6) | 0.005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 437 (2.9) | 5579 (4.4) | 0.080 | 437 (2.9) | 441 (3.0) | 0.002 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 320 (2.2) | 4150 (3.3) | 0.071 | 320 (2.2) | 288 (1.9) | 0.015 |

| Chronic lower-respiratory disease | 1789 (12.1) | 17 673 (14.1) | 0.060 | 1789 (12.1) | 1760 (11.9) | 0.006 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1261 (8.5) | 14 841 (11.8) | 0.110 | 1261 (8.5) | 1207 (8.1) | 0.013 |

| Anemia | 822 (5.5) | 10 552 (8.4) | 0.113 | 822 (5.5) | 801 (5.4) | 0.006 |

| Inflammatory liver disease | 308 (2.1) | 2064 (1.6) | 0.032 | 308 (2.1) | 277 (1.9) | 0.015 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 259 (1.7) | 2241 (1.8) | 0.003 | 259 (1.7) | 286 (1.9) | 0.014 |

| Neoplasm | 2166 (14.6) | 19 460 (15.5) | 0.025 | 2166 (14.6) | 2209 (14.9) | 0.008 |

| Systemic connective tissue disorder | 248 (1.7) | 2124 (1.7) | 0.002 | 248 (1.7) | 244 (1.6) | 0.002 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 74 (0.5) | 632 (0.5) | 0.001 | 74 (0.5) | 81 (0.5) | 0.007 |

| HIV | 53 (0.4) | 895 (0.7) | 0.049 | 53 (0.4) | 45 (0.3) | 0.009 |

| Dementia | 36 (0.2) | 614 (0.5) | 0.041 | 36 (0.2) | 32 (0.2) | 0.006 |

| Diabetic complications | ||||||

| Kidney | 1281 (8.6) | 13700 (10.8) | 0.069 | 1281 (8.6) | 1226 (8.3) | 0.013 |

| Ophthalmic | 699 (4.7) | 6015 (4.8) | 0.002 | 698 (4.7) | 663 (4.5) | 0.011 |

| Neurologic | 1610 (10.9) | 14143 (11.2) | 0.004 | 1609 (10.8) | 1555 (10.5) | 0.012 |

| Circulatory | 850 (5.7) | 7503 (5.9) | 0.004 | 850 (5.7) | 812 (5.5) | 0.011 |

| SES and psychosocial-related health hazards | 322 (2.2) | 4019 (3.2) | 0.060 | 322 (2.2) | 313 (2.1) | 0.004 |

| Medications | ||||||

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors | 5530 (37.3) | 55 876 (44.5) | 0.148 | 5530 (37.3) | 5424 (36.6) | 0.015 |

| Fibrates | 461 (3.1) | 3715 (3.0) | 0.009 | 461 (3.1) | 420 (2.8) | 0.016 |

| Ezetimibe | 427 (2.9) | 3536 (2.8) | 0.004 | 427 (2.9) | 434 (2.9) | 0.003 |

| Biguanides | 5449 (36.7) | 54 056 (43.1) | 0.130 | 5449 (36.7) | 5415 (36.5) | 0.005 |

| Sulfonylureas | 1397 (9.4) | 17 517 (14.0) | 0.142 | 1397 (9.4) | 1331 (9.0) | 0.015 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 842 (5.7) | 10 329 (8.2) | 0.101 | 842 (5.7) | 807 (5.4) | 0.010 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 393 (2.7) | 3565 (2.8) | 0.012 | 393 (2.7) | 352 (2.4) | 0.018 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 2544 (17.2) | 19 843 (15.8) | 0.036 | 2544 (17.2) | 2403 (16.2) | 0.026 |

| Insulin | 3870 (26.1) | 34 311 (27.3) | 0.028 | 3870 (26.1) | 3687 (24.9) | 0.028 |

| β-Blockers | 3082 (20.8) | 31 563 (25.2) | 0.104 | 3082 (20.8) | 3043 (20.5) | 0.006 |

| ACEis | 2871 (19.4) | 25 812 (20.6) | 0.030 | 2871 (19.4) | 2835 (19.1) | 0.006 |

| ARBs | 2628 (17.7) | 27 153 (21.6) | 0.099 | 2628 (17.7) | 2578 (17.4) | 0.009 |

| Diuretics | 3775 (25.5) | 35 796 (28.5) | 0.069 | 3775 (25.5) | 3706 (25.0) | 0.011 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2298 (15.5) | 24 569 (19.6) | 0.108 | 2298 (15.5) | 2282 (15.4) | 0.003 |

| Laboratory tests and examinations | ||||||

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 7.66 (1.82) | 8.01 (1.95) | 0.185 | 7.66 (1.82) | 7.69 (1.94) | 0.016 |

| ≥7% | 6391 (43.1) | 57 672 (46.0) | 0.058 | 6391 (43.1) | 6230 (42.0) | 0.022 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 13.7 (1.8) | 13.4 (1.9) | 0.165 | 13.7 (1.8) | 13.6 (1.9) | 0.071 |

| ≥12 g/dL | 7514 (50.7) | 62 308 (49.7) | 0.020 | 7514 (50.7) | 7451 (50.2) | 0.008 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 81.4 (24.9) | 80.3 (27.7) | 0.042 | 81.4 (24.9) | 82.6 (27.4) | 0.044 |

| ≥45 mL/min/1.73m2 | 9527 (64.2) | 79 769 (63.6) | 0.014 | 9527 (64.2) | 9330 (62.9) | 0.028 |

| SBP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 131.4 (17.1) | 131.8 (17.9) | 0.023 | 131.4 (17.1) | 131.5 (17.7) | 0.009 |

| ≥130 mm Hg | 7591 (51.2) | 65 805 (52.4) | 0.025 | 7591 (51.2) | 7609 (51.3) | 0.002 |

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 92.9 (37.3) | 92.3 (38.6) | 0.016 | 92.9 (37.3) | 93.2 (37.8) | 0.008 |

| ≥160 mg/dL | 563 (3.8) | 4833 (3.9) | 0.003 | 563 (3.8) | 552 (3.7) | 0.004 |

| 100-160 mg/dL | 3082 (20.8) | 24 892 (19.8) | 0.023 | 3082 (20.8) | 2984 (20.1) | 0.016 |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 169.0 (50.8) | 169.3 (49.2) | 0.006 | 169.0 (50.8) | 169.6 (48.3) | 0.014 |

| ≥240 mg/dL | 697 (4.7) | 6617 (5.3) | 0.026 | 697 (4.7) | 677 (4.6) | 0.006 |

| 200–240 mg/dL | 1412 (9.5) | 13 071 (10.4) | 0.030 | 1412 (9.5) | 1394 (9.4) | 0.004 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 36.7 (6.2) | 34.8 (6.7) | 0.285 | 36.7 (6.2) | 36.5 (6.3) | 0.026 |

| ≥30 | 8055 (54.3) | 58 981 (47.0) | 0.146 | 8055 (54.3) | 7980 (53.8) | 0.010 |

| 25–30 | 1495 (10.1) | 18 674 (14.9) | 0.146 | 1495 (10.1) | 1461 (9.9) | 0.008 |

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HMG-CoA, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SES, socioeconomic status; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2.

SI conversion factors: To convert HbA1c to proportion of total HbA1c, multiply by 0.01; to convert hemoglobin to g/L, multiply by 10; to convert LDL and total cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

Other race and ethnicity included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, multiracial, or not belonging to any racial or ethnic group listed here or in the table.

Prespecified Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality during the follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), including myocardial infarction, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, or cardiac death; kidney events, including stage 5 CKD, ESKD, or need for dialysis; and MAKEs, including stage 5 CKD, ESKD, need for dialysis, or death.

Additionally, we investigated acute kidney injury (AKI) and the composite of all-cause mortality and MACEs. To establish a baseline for comparison, we included hernia, traumatic intracranial injury, sensorineural hearing loss, skin cancer, and lumbar radiculopathy as negative control outcomes, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and simethicone as negative control exposures. Each component of the composite outcomes was also evaluated for consistency of effect direction. Changes in HbA1c and body weight were evaluated at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 months after the index date. The diagnostic, visit, and procedural codes used to define these outcomes are provided in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

We performed prespecified subgroup analyses based on baseline eGFR (≥45 or <45 mL/min/1.73 m2); HbA1c (≥7% or <7%); BMI (≥30 or <30); presence of hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or proteinuria; use of metformin, insulin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis), or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs); or previous GLP-1 RA use in the tirzepatide group. To investigate potential differences based on drug indications, such as glycemic control or weight reduction, we also stratified the patients by HbA1c level and BMI as follows: normal BMI of less than 25 (may have received the medications for diabetes control), BMI of 25 or higher and HbA1c less than 7% (may have been treated for weight loss given that their HbA1c was below the target per current treatment guidelines16), and BMI of 25 or higher and HbA1c greater than 7% (may have been treated for both weight loss and glycemic control).

The potential dose effect was evaluated by comparing different tirzepatide doses (maximum ≤7.5 mg or ≥10 mg) with the maximal doses of GLP-1 RA. To investigate the robustness of our findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by incorporating individuals without follow-up outcomes into PSM and survival analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA groups were presented as means with SDs or counts with percentages. Categorical variables were compared by χ2 test and continuous variables by independent 2-sample t test. One-to-one PSM was performed using the greedy nearest neighbor algorithm with a caliper of 0.1 pooled SDs to balance baseline characteristics between the 2 groups. Variables were considered adequately matched if the between-group standardized difference was less than 0.1. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival probabilities after PSM. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) with 95% CIs and P values were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models for all outcomes. The quantitative effect of unmeasured confounding was analyzed using the E-value method, which assesses the effect magnitude required for unaccounted confounders to elucidate the observed variances between the 2 groups. An E-value of x indicates that the observed association could be explained away only by an unmeasured confounder associated with both the treatment and the outcome by a risk ratio of at least x-fold each, beyond the measured confounders.17 Proportional hazard assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Missing data regarding the outcomes were addressed by excluding the respective cases. Likewise, patients lost to follow-up were excluded to avoid bias or inaccuracies from incomplete data. All tests were 2-sided with P < .05. For the 6 primary and secondary outcomes, Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons, with α set at .0083, providing an overall type I error rate of .0488. Statistical analyses were conducted using the analytic tool on the TriNetX platform and R, version 4.2.2.

Results

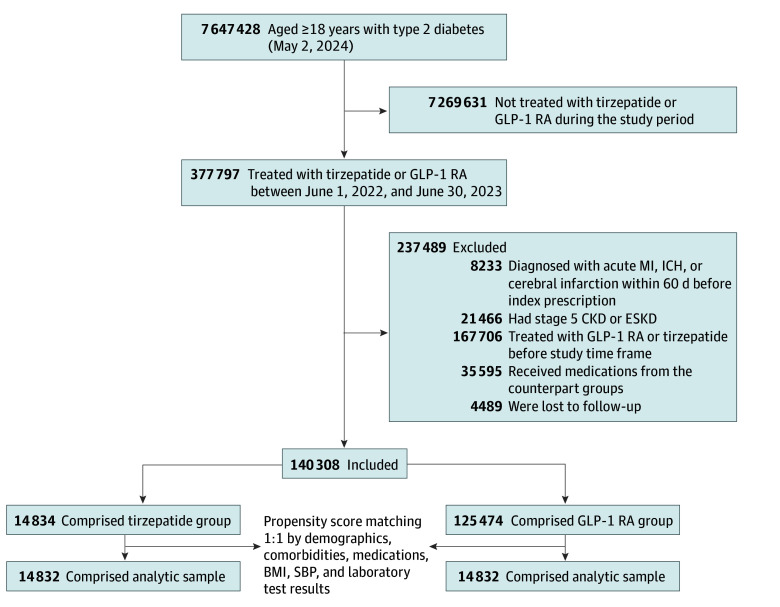

Within the cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes, 14 834 received tirzepatide, while 125 474 were prescribed a GLP-1 RA during the study time frame (Figure 1). The numbers of patients excluded due to lack of follow-up after the index date were 348 of 15 182 (2.3%) prescribed tirzepatide and 4141 of 129 615 (3.2%) prescribed a GLP-1 RA. The characteristics of patients lost to follow-up were similar between groups, including younger age, a high proportion of male and Black individuals, high HbA1c, and few comorbidities (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Following PSM, each group included 14 832 individuals for our outcome analyses (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Cohort Construction.

BMI indicates body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Before PSM, tirzepatide-treated patients were younger (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [11.8] years) compared with the GLP-1 RA group (mean [SD] age, 58.1 [13.3] years) (P < .001). Additionally, the tirzepatide group had a higher percentage of White patients (67.3% vs 60.4%; P < .001), whereas the GLP-1 RA group had higher percentages of Black (20.1% vs 17.0%), Asian (3.6% vs 2.3%), and Hispanic or Latinx (9.3% vs 6.5%) patients; and a higher percentage of female patients (56.9% vs 53.8%; P < .001), whereas the GLP-1 RA group a higher percentage of males (42.5% vs 37.5%). Patients in the tirzepatide group also had lower prevalence rates of CKD or anemia, and fewer were using statins, biguanides, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, β-blockers, ARBs, or calcium channel blockers. After PSM, the 2 groups were balanced, with standardized differences for all the included covariates being less than 0.1 (Table 1).

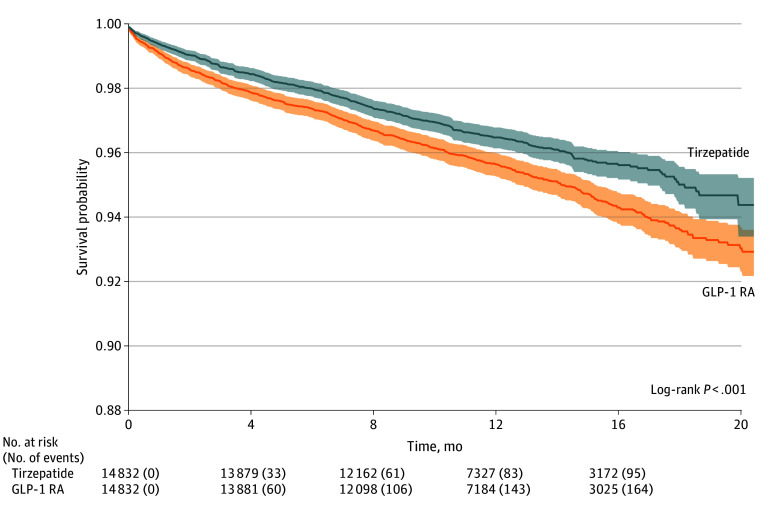

All-Cause Mortality

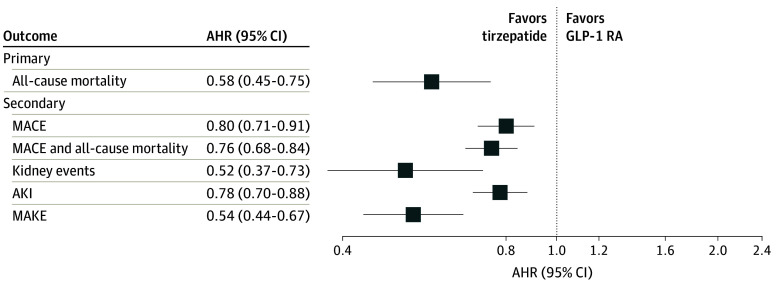

The overall cohort was followed up for a median of 10.5 months (IQR, 5.2-15.7 months). During the follow-up period, 95 patients (0.6%) in the tirzepatide group and 166 (1.1%) in the GLP-1 RA group died. We observed a lower hazard of all-cause mortality in patients given tirzepatide compared with GLP-1 RA (AHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.45-0.75; P < .001) (Table 2; Figure 2; Figure 3). The test for proportionality showed no violation of the proportional hazards assumption (Schoenfeld test P = .94).

Table 2. Comparison of Tirzepatide vs GLP-1 RA for Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcome | No. of patients with outcome | AHR (95% CI) | P value | E-value (E-value for the upper limit of CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide (n = 14 832) | GLP-1 RA (n = 14 832) | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| All-cause mortality | 95 | 166 | 0.58 (0.45-0.75)a | <.001b | 2.82 (1.99) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| MACEs | 472 | 589 | 0.80 (0.71-0.91)a | <.001b | 1.79 (1.44) |

| MACE and all-cause mortality | 543 | 721 | 0.76 (0.68-0.84)a | <.001b | 1.98 (1.65) |

| Kidney events | 53 | 102 | 0.52 (0.37-0.73)a | <.001b | 3.24 (2.09) |

| Acute kidney injury | 506 | 652 | 0.78 (0.70-0.88)a | <.001b | 1.87 (1.53) |

| MAKEs | 129 | 241 | 0.54 (0.44-0.67)a | <.001b | 3.11 (2.35) |

Abbreviations: AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MAKE, major adverse kidney event.

Proportionality (Schoenfeld test P > .05).

Bonferroni-corrected α = .0083.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

AHR indicates adjusted hazard ratio; AKI, acute kidney injury; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MAKE, major adverse kidney event.

Figure 3. All-Cause Mortality.

GLP-1 RA indicates glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist.

Secondary Outcomes

The hazard of MACEs was lower among patients treated with tirzepatide (AHR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71-0.91; P < .001), as was the hazard of kidney events (AHR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.37-0.73; P < .001), AKI (AHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.88; P < .001), MAKEs (AHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.67; P < .001), and the composite of MACEs and all-cause mortality (AHR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84; P < .001), favoring tirzepatide (Table 2; Figure 2). Our E-value analysis indicated an unlikely significant influence from unmeasured confounders (E-values of the point estimates [upper limits of the CI] for all-cause mortality, MACEs, and kidney events were 2.82 [1.99], 1.79 [1.44], and 3.24 [2.09], respectively) (Table 2). The hazard of each MACE component (ie, myocardial infarction, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, cardiac death) and MAKE component (ie, stage 5 CKD or ESKD) was consistently lower with tirzepatide compared with GLP-1 RAs, with AHRs ranging from 0.78 (95% CI, 0.67-0.91) to 0.91 (95% CI, 0.56-1.45) for MACE components and from 0.45 (95% CI, 0.25-0.82) to 0.49 (95% CI, 0.35-0.67) for MAKE components (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Sensitivity analysis incorporating patients without any follow-up into PSM and survival analyses showed consistent results with our main analysis (eTable 6 in Supplement 1).

Compared with GLP-1 RA treatment, tirzepatide treatment was associated with greater reductions in HbA1c (treatment difference, −0.34 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.44 to −0.24 percentage points) and body weight (treatment difference, −2.9 kg; 95% CI, −4.8 to −1.1 kg) over 20 months. The most significant HbA1c decrease occurred within the first 4 months and stabilized after 8 months, while weight reduction persisted through 16 to 20 months (eTable 7 and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

Results comparing tirzepatide vs maximal doses of GLP-1 RA closely matched the main analysis, with similar AHRs and corresponding 95% CIs (eFigure 2A in Supplement 1). When stratified by tirzepatide dose, treatment with 10 mg or more was associated with lower hazards of all-cause mortality, MACEs, and MAKEs compared with 7.5 mg or less (eFigure 2B and C in Supplement 1).

Negative Controls and Subgroup Analysis

Our study revealed no significant differences in the hazard of negative control outcomes between the tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA groups for hernia, traumatic intracranial injury, sensorineural hearing loss, lumbar radiculopathy, and skin cancer. Results were consistent when selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and simethicone were introduced as negative control exposures (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). The interaction test revealed no significant effect differences across all subgroups stratified by eGFR; HbA1c; presence of hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, proteinuria, or diabetic complications; use of metformin, insulin, SGLT2is, ACEis, or ARBs; previous use of GLP-1 RAs; potential treatment indications (body weight loss, glycemic control, or both); LDL cholesterol level; or BMI (all interaction test P > .05) (eFigures 4-9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

From this retrospective cohort study of 140 308 US patients with type 2 diabetes treated with tirzepatide or GLP-1 RAs, we have for the first time to our knowledge presented evidence substantiating that tirzepatide therapy is associated with lower risks of all-cause mortality, MACEs, MAKEs, and AKI compared with GLP-1 RA therapy after a median follow-up of 10.5 months. Consistent results were found in subgroup analyses stratified by eGFR; HbA1c; presence of cardiovascular disease, proteinuria, or diabetic complications; use of metformin, insulin, SGLT2is, ACEis, or ARBs; previous GLP-1 RA treatment; potential indications; LDL cholesterol level; and BMI.

The association of tirzepatide with less all-cause mortality and MACEs may be attributable to tirzepatide’s efficacy in improving the cardiovascular risk profile, including blood pressure, LDL, triglycerides, HbA1c,8,18 cardiovascular risk biomarkers,19 and body weight in patients with obesity.18,20 Consistently, a network meta-analysis comparing various GLP-1 RAs and dual and triple receptor agonists showed that tirzepatide was the most effective in reducing HbA1c, fasting glucose, triglyceride level, and waist circumference compared with all other GLP-1 RAs.21 The meta-analysis also ranked tirzepatide second for weight loss, surpassed only by cagrilintide-semaglutide, another dual receptor agonist under development. Our analysis similarly showed an association of greater HbA1c and weight loss with tirzepatide, and the trajectories aligned with those reported in previous trials,8 suggesting a potential mediatory role for these factors. This finding is in line with a recent report in which withdrawing tirzepatide led to substantial weight regain.22 Nonetheless, studies on the efficacy of tirzepatide in reducing adverse cardiovascular outcomes have yielded inconsistent results, suggesting that GIP may have both beneficial23,24 and untoward cardiovascular effects,25,26 though the results may be due to reverse causality.

While 1 meta-analysis of 7 RCTs reported no significant difference in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and MACE risk between tirzepatide and a mix of comparators, including placebo, 2 insulin formulations, and GLP-1 RAs,11 another study of 8 RCTs contrarily showed a significant decrease in all-cause mortality and MACE risk with tirzepatide treatment compared with the control group receiving placebo or active comparators.27 The disparity may be due to differences in the included studies, comparators, sample sizes, baseline patient characteristics, and outcome definitions. Both studies carried high clinical heterogeneity in participant inclusion criteria and comparator selection. Of note, previous trials on tirzepatide and GLP-1 RAs for cardiovascular and mortality outcomes had median follow-ups of 1.6 to 3.8 years,28,29 but the survival curves for composite primary cardiovascular outcomes began diverging as early as 8 weeks to approximately 6 months,28,29,30,31 suggesting potential early benefits after treatment initiation.

Both GLP-1 and GIP belong to the incretin system that regulates hormone secretion in response to carbohydrate intake.32 Although the effect of GIP has been found to be greatly attenuated in patients with type 2 diabetes,33 subsequent research has shown that islet β-cell sensitivity to GIP may be restored with glycemic control.34 Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide acts in the central nervous system by blocking nausea and emesis from GLP-1 agonism without affecting satiety or energy intake reduction,35 thereby improving overall treatment tolerability. In animal studies, dual GLP-1 and GIP coagonists synergistically reduced fat mass and improved metabolic profiles superior to selective GLP-1 agonist, contrary to selective GIP agonist, which was weight neutral.36 Subsequent clinical trials confirmed that tirzepatide was more effective than selective GLP-1 agonists in increasing insulin secretion and sensitivity, improving meal tolerance, and suppressing glucagon secretion,37 with similar suppression of appetite and calorie intake.38 Additionally, nutrition-independent regulation of the GIP pathway through inflammatory stimuli may stabilize atherosclerosis plaques by inhibiting monocyte and macrophage activation39 and suppressing cardiomyocyte enlargement, apoptosis, and interstitial fibrosis.40 The potential superiority of GIP and GLP-1 RAs over GLP-1 RAs for MACEs and mortality, as suggested by our findings, indicates that combined activation of GIP and GLP-1 receptors may provide additional benefits over the activation of GLP-1 receptors alone.

The kidney-protective effect of tirzepatide was first shown in post hoc analyses of the SURPASS-4 (Tirzepatide vs Insulin Glargine in Type 2 Diabetes and Increased Cardiovascular Risk) trial, which recruited patients with type 2 diabetes, overweight, and established or high risk for cardiovascular disease. Patients treated with tirzepatide added to insulin had less eGFR decline10,41 and proteinuria progression and fewer composite kidney end points compared with the insulin group.10 These findings align with studies on selective GLP-1 agonists.42 Notably, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to directly compare the association with kidney outcomes between tirzepatide and selective GLP-1 RAs. Preclinical studies suggested that GIP may attenuate local adipose tissue inflammation and reduce proinflammatory cytokine levels,43 which may act favorably on the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease.44 On the other hand, GLP-1 receptors are present on preglomerular vascular smooth muscle, glomerular, and tubular cells and, thus, may directly affect the kidney.45,46 Proposed mechanisms include afferent arteriole vasodilation, proximal tubular diuresis, and inhibition of glomerular hyperfiltration.45,47 Importantly, pharmacokinetic studies showed that tirzepatide exposure was not significantly affected by kidney function impairment48 and represented a viable therapy for patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD, for whom few options existed.49 Treatment with tirzepatide or a GLP-1 RA might pose a risk of AKI due to dehydration from gastrointestinal adverse effects.50,51 Although our analysis found a lower hazard of AKI in the tirzepatide group compared with the GLP-1 RA group, this result should be interpreted with caution since we could not identify the cause of these AKI events or their chronologic association with tirzepatide or GLP-1 RA use.

The interaction test from subgroup analyses revealed no significant discrepancies in our primary and secondary outcomes among different subgroups. Of note, most patients included in this study were relatively healthy, with an eGFR of at least 45 mL/min/1.73 m2; no history of ischemic heart disease or heart failure; and not taking metformin, insulin, SGLT2is, ACEis, or ARBs. Accordingly, the null results from our subgroup analyses may be partly due to reduced statistical power from smaller sample sizes. Nevertheless, for individuals already benefiting from efficacious treatments, the integration of GIP agonists surpassed the efficacy of existing therapeutic regimens in specific combinations. The potential dose-response relationships observed in our analysis stratified by tirzepatide dose also support tirzepatide’s possible efficacy.

Our findings also provide directions for future research in other target populations. The observational nature of our data precluded inference of causality, which might be confirmed in future research, such as in ongoing RCTs evaluating the efficacy of tirzepatide in improving cardiovascular and kidney outcomes compared with GLP-1 agonists52 and in treating patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.53

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, data from TriNetX were registry based, and therefore, misidentification and underrepresentation of mild cases or of individuals not engaged with the health care system may exist and influence the results. The reliance on diagnostic codes to identify variables and outcomes may also result in misclassification, potentially biasing the results. To address this information bias, we conducted specificity tests comparing unrelated events between the tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA groups and found no significant differences, indicating little registration bias. Second, the duration of treatment could not be ascertained from the database, precluding analysis of a long-term carryover effect. While we observed clinical benefits, their effect sizes were relatively imprecise when interpreting the confidence intervals and require further investigation. Third, unmeasured variables may have contributed to the studied outcomes, introducing additional confounding. Given the observational nature of this study and that some baseline characteristics differed between the groups, residual confounding cannot be eliminated entirely. To address potential bias, we juxtaposed unrelated events among GLP-1 RA and tirzepatide users, finding no discernible disparities and indicating that bias from residual confounding may be negligible. We also used comedication and biochemical results as proxies for disease severity to mitigate potential confounding. Higher E-values that surpassed the hazard ratios indicated that minor unaccounted confounders could not counteract the observed association, thus increasing the potential for causality. Fourth, although consistent results were found in sensitivity analyses incorporating individuals lost to follow-up into survival analysis, much of the nonsummarized data and their changes over time were restricted from investigators to safeguard the detailed health information from potential misuse in identifying and tracking specific individuals, thereby precluding further imputation methods. Fifth, information directly related to socioeconomic status, including education, income, and insurance status, was not documented, limiting further investigation into their contributions. Finally, this study comprised patients with type 2 diabetes, of whom most were relatively healthy without underlying cardiovascular or advanced kidney diseases, so the applicability of our findings to other clinical settings remain to be explored.

Conclusions

In summary, this cohort study provided evidence supporting the association of tirzepatide treatment, compared to GLP-1 RAs, with lower hazards of all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular or kidney events through a head-to-head comparison in patients with type 2 diabetes. These insights advocate for the integration of tirzepatide into therapeutic strategies for managing type 2 diabetes and highlight its potential to enhance current clinical practice.

eTable 1. Demographic, Diagnostic, Procedural, Medication, Visit, and Laboratory Codes Used in the Definition of the Cohorts

eTable 2. Demographic, Diagnostic, and Laboratory Codes Used in the Definition of Covariates

eTable 3. Diagnostic, Visit, and Procedural Codes Used in the Definition of Outcomes

eTable 4. Numbers and Characteristics of Individuals Excluded Because of a Lack of Any Follow-Up

eTable 5. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for the Components of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and Kidney Events

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Incorporating Individuals Without Follow-Up Into Propensity Score Matching and Survival Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcomes

eTable 7. Changes in Mean Glycated Hemoglobin Level and Body Weight (95% CI)

eFigure 1. Changes in Glycated Hemoglobin Level and Body Weight From Baseline

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Primary and Secondary Outcomes Compared Between Different Doses of Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA

eFigure 3. Results for Negative Control Outcomes and Analysis With Negative Control Exposure

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis of All-Cause Mortality Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 5. Subgroup Analysis of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 6. Subgroup Analysis of the Composite of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 7. Subgroup Analysis of Kidney Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 8. Subgroup Analysis of Acute Kidney Injury Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 9. Subgroup Analysis of Major Adverse Kidney Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361-377. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0001-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng Y, Li N, Wu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes-related chronic kidney disease from 1990 to 2019. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:672350. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.672350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glovaci D, Fan W, Wong ND. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21(4):21. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1107-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, de Boer IH, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health . Cardiorenal protection with the newer antidiabetic agents in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(17):e265-e286. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown E, Heerspink HJL, Cuthbertson DJ, Wilding JPH. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists: established and emerging indications. Lancet. 2021;398(10296):262-276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00536-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 Receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coskun T, Sloop KW, Loghin C, et al. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: from discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol Metab. 2018;18:3-14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. ; SURPASS-2 Investigators . Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503-515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingvay I, Mosenzon O, Brown K, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction with tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes: insights from SURPASS clinical program. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12933-023-01797-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heerspink HJL, Sattar N, Pavo I, et al. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(11):774-785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00243-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sattar N, McGuire DK, Pavo I, et al. Tirzepatide cardiovascular event risk assessment: a pre-specified meta-analysis. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):591-598. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TriNetX . Accessed September 6, 2023. https://trinetx.com

- 13.Palchuk MB, London JW, Perez-Rey D, et al. A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open. 2023;6(2):ooad035. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooad035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan HC, Chen JY, Chen HY, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransport protein 2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute kidney disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2350050. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee . 6: Glycemic goals and hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(suppl 1):S111-S125. doi: 10.2337/dc24-S006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karagiannis T, Avgerinos I, Liakos A, et al. Management of type 2 diabetes with the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2022;65(8):1251-1261. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05715-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson JM, Lin Y, Luo MJ, et al. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide improves cardiovascular risk biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(1):148-153. doi: 10.1111/dom.14553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. ; SURMOUNT-1 Investigators . Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;384:e076410. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronne LJ, Sattar N, Horn DB, et al. ; SURMOUNT-4 Investigators . Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: the SURMOUNT-4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(1):38-48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.24945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagashima M, Watanabe T, Terasaki M, et al. Native incretins prevent the development of atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54(10):2649-2659. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2241-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karhunen V, Daghlas I, Zuber V, et al. Leveraging human genetic data to investigate the cardiometabolic effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide signalling. Diabetologia. 2021;64(12):2773-2778. doi: 10.1007/s00125-021-05564-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jujić A, Atabaki-Pasdar N, Nilsson PM, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality: a prospective study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(5):1043-1054. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05093-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jujić A, Nilsson PM, Atabaki-Pasdar N, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide in the high-normal range is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(1):224-230. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patoulias D, Papadopoulos C, Fragakis N, Doumas M. Updated meta-analysis assessing the cardiovascular efficacy of tirzepatide. Am J Cardiol. 2022;181:139-140. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al. ; Harmony Outcomes Committees and Investigators . Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1519-1529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. ; LEADER Steering Committee; LEADER Trial Investigators . Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. ; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators . Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Prato S, Kahn SE, Pavo I, et al. ; SURPASS-4 Investigators . Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10313):1811-1824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02188-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holst JJ. The incretin system in healthy humans: the role of GIP and GLP-1. Metabolism. 2019;96:46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vilsbøll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst JJ. Defective amplification of the late phase insulin response to glucose by GIP in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45(8):1111-1119. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0878-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Højberg PV, Vilsbøll T, Rabøl R, et al. Four weeks of near-normalisation of blood glucose improves the insulin response to glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(2):199-207. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1195-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marques-Antunes J, Braga J, Santos T, Nora M, Scigliano H. Basal cell carcinoma after radiation therapy in breast cancer. Breast J. 2021;27(8):678-680. doi: 10.1111/tbj.14266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finan B, Ma T, Ottaway N, et al. Unimolecular dual incretins maximize metabolic benefits in rodents, monkeys, and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(209):209ra151. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heise T, Mari A, DeVries JH, et al. Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(6):418-429. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00085-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heise T, DeVries JH, Urva S, et al. Tirzepatide reduces appetite, energy intake, and fat mass in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(5):998-1004. doi: 10.2337/dc22-1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kahles F, Liberman A, Halim C, et al. The incretin hormone GIP is upregulated in patients with atherosclerosis and stabilizes plaques in ApoE−/− mice by blocking monocyte/macrophage activation. Mol Metab. 2018;14:150-157. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiromura M, Mori Y, Kohashi K, et al. Suppressive effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide on cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in angiotensin II-infused mouse models. Circ J. 2016;80(9):1988-1997. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heerspink HJL, Sattar N, Pavo I, et al. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on cystatin C-based kidney function: a SURPASS-4 post hoc analysis. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(8):1501-1506. doi: 10.2337/dc23-0261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mima A, Gotoda H, Lee R, Murakami A, Akai R, Lee S. Effects of incretin-based therapeutic agents including tirzepatide on renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Metabol Open. 2023;17:100236. doi: 10.1016/j.metop.2023.100236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finan B, Müller TD, Clemmensen C, Perez-Tilve D, DiMarchi RD, Tschöp MH. Reappraisal of GIP pharmacology for metabolic diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(5):359-376. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pérez-Morales RE, Del Pino MD, Valdivielso JM, Ortiz A, Mora-Fernández C, Navarro-González JF. Inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. Nephron. 2019;143(1):12-16. doi: 10.1159/000493278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muskiet MHA, Tonneijck L, Smits MM, et al. GLP-1 and the kidney: from physiology to pharmacology and outcomes in diabetes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(10):605-628. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK, et al. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology. 2014;155(4):1280-1290. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson SC, Kashkouli A, Singh P. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor stimulation increases GFR and suppresses proximal reabsorption in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304(2):F137-F144. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00064.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urva S, Quinlan T, Landry J, Martin J, Loghin C. Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of the dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(8):1049-1059. doi: 10.1007/s40262-021-01012-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossing P, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5):990-999. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filippatos TD, Elisaf MS. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on renal function. World J Diabetes. 2013;4(5):190-201. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v4.i5.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fanshier AV, Crews BK, Garrett MC, Johnson JL. Tirzepatide: a novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide/glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: the first twincretin. Clin Diabetes. 2023;41(3):367-377. doi: 10.2337/cd22-0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.A study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) compared with dulaglutide on major cardiovascular events in participants with type 2 diabetes. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04255433. Updated May 29, 2024. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?term=NCT04255433

- 53.A study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) in participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HfpEF) and obesity: the SUMMIT trial. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04847557. Updated May 29, 2024. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?term=NCT04847557

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Demographic, Diagnostic, Procedural, Medication, Visit, and Laboratory Codes Used in the Definition of the Cohorts

eTable 2. Demographic, Diagnostic, and Laboratory Codes Used in the Definition of Covariates

eTable 3. Diagnostic, Visit, and Procedural Codes Used in the Definition of Outcomes

eTable 4. Numbers and Characteristics of Individuals Excluded Because of a Lack of Any Follow-Up

eTable 5. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for the Components of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and Kidney Events

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Incorporating Individuals Without Follow-Up Into Propensity Score Matching and Survival Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcomes

eTable 7. Changes in Mean Glycated Hemoglobin Level and Body Weight (95% CI)

eFigure 1. Changes in Glycated Hemoglobin Level and Body Weight From Baseline

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Primary and Secondary Outcomes Compared Between Different Doses of Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA

eFigure 3. Results for Negative Control Outcomes and Analysis With Negative Control Exposure

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis of All-Cause Mortality Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 5. Subgroup Analysis of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 6. Subgroup Analysis of the Composite of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 7. Subgroup Analysis of Kidney Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 8. Subgroup Analysis of Acute Kidney Injury Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

eFigure 9. Subgroup Analysis of Major Adverse Kidney Events Between Tirzepatide and GLP-1 RA Groups

Data Sharing Statement