Abstract

Purpose:

Family physicians are increasingly more likely to encounter transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) patients requesting gender-affirming care. Given the significant health inequities faced by the TGD community, this study aimed to assess changes in military-affiliated clinicians’ perspectives toward gender-affirming care over time.

Methods:

Using a serial cross-sectional survey design of physicians at the 2016 and 2023 Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians conferences, we studied participants’ perception of, comfort with, and education on gender-affirming care using Fisher’s Exact tests and logistic regression.

Results:

Response rates were 68% (n = 180) and 69% (n = 386) in 2016 and 2023, respectively. Compared to 2016, clinicians in 2023 were significantly more likely to report receiving relevant education during training, providing care to >1 patient with gender dysphoria, and being able to provide nonjudgmental care. In 2023, 26% reported an unwillingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormones (GAH) to adults due to ethical concerns. In univariable analysis, female-identifying participants were more likely to report willingness to prescribe GAH (OR = 2.6, 95%CI = 1.7-4.1) than male-identifying participants. Willingness to prescribe was also associated with ≥4 h of education (OR = 2.2, 95%CI = 1.1-4.2) compared to those with fewer than 4 h, and those who reported the ability to provide nonjudgmental care compared to those who were neutral (OR = 0.09, 95%CI = 0.04-0.2) or disagreed (OR = 0.11, 95%CI = 0.03-0.39). Female-identifying clinicians were more likely to agree additional training would benefit their practice (OR = 5.3, 95%CI = 3.3-8.5).

Conclusions:

Although military-affiliated family physicians endorsed more experience with and willingness to provide nonjudgmental gender-affirming care in 2023 than 2016, profound gaps in patient experience may remain based on the assigned clinician. Additional training opportunities should be available, and clinicians unable to provide gender-affirming care should ensure timely referrals. Future research should explore trends across clinical specialties.

Keywords: (MeSH): United States, gender dysphoria, transgender persons, military personnel, hormones, LGBTQ Persons, health inequities

Introduction

In the United States (US), more than 1.6 million people, including 700 000 youth identify as transgender and gender-diverse (TGD),1,2 such that their gender identity or behavior differs from those socially attributed to their sex assigned at birth. 3 This incongruence can lead to significant clinical distress or impairment (ie, gender dysphoria),3 -5 and family physicians are increasingly more likely to encounter TGD people who request primary or gender-affirming care, such as counseling, exogenous sex hormone therapy, and surgery, in their medical practice. 6 For example, one study examining TGD people’s reasons for primary care visits demonstrated that approximately 50% were related to gender-affirming care. 7

One relevant subgroup of primary care physicians available to provide gender-affirming care to a diverse population worldwide at minimal cost to beneficiaries is US military-affiliated family physicians. These clinicians serve US military Service members and retirees, as well as their family members; many clinicians eventually separate from the military and serve as leaders in the civilian primary care workforce. With the TGD community’s overrepresentation in the Military Health System (MHS) at a ratio up to 2:1 compared to the general population,8,9 military-affiliated family physicians are likely to provide healthcare to TGD patients and are well-positioned to reduce inequities in access to care.

TGD people face significant inequities in health and healthcare access and utilization compared to their cisgender peers,10 -13 which are amplified in communities of color and can vary significantly depending on legislation and insurance coverage.14 -16 For instance, TGD persons have cited a lack of clinicians’ cultural sensitivity as a barrier to care.17,18 Up to one-third of TGD individuals avoid or delay care due to fear of discrimination or mistreatment,19 -21 with the odds of delaying care increasing when patients perceive the need to teach their clinician about gender-affirming care. 11 Avoidance of care and preventive services or use of non-traditional medical care due to prior negative experiences with traditional healthcare systems has been found within studies from several countries, 22 and has been associated with decreased life expectancy. 23 Increasing awareness of these inequities has led to calls for training on gender-affirming care in US undergraduate and graduate medical education.24,25 Furthermore, the extent to which US medical residency programs cover gender-affirming care or provide experiences for residents to work with TGD patients is widely disparate.24,26 One study showed that, although 71% of family medicine residents felt that gender-affirming care was within their scope of practice, only 10% felt competent in providing it post-training. 26 The knowledge gap may be profound for clinicians caring for TGD youth, with one study revealing that 86% of pediatric specialists desired training in gender-affirming care. 12

Educational interventions, even as brief as 2 h of instruction, appear to effectively improve competency in caring for TGD patients in clinical practice, including in domains of clinician attitude, knowledge, and skill.25,27 -29 However, compared to studies on educational interventions or patient experiences with gender-affirming care, research examining primary care physicians’ perceptions of and ability to provide gender-affirming care remains more limited.17,30 -36 This is important because the majority of TGD individuals report concerns about the lack of medical professionals trained to care for them, 37 which may lead to several downstream impacts on TGD patients’ health outcomes (eg, rates of depression, substance use, and STI/HIV prevention).22,38 -40 Therefore, this study aimed to assess changes in military-affiliated family physicians’ perception of, comfort with, and education in providing gender-affirming care over time by comparing cohorts surveyed in 2016 and 2023. Additionally, we sought to assess if factors, such as clinician experience and sociodemographics, would be predictors of perceived ability and willingness to provide gender-affirming care.

Methods

We conducted a serial cross-sectional study based on surveys distributed to all attendees of the Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians Annual (USAFP) Conferences in March 2016 and 2023. The Institutional Review Board at the senior author’s institution approved this study and the USAFP Clinical Investigation Committee reviewed and approved inclusion of our questions in the larger omnibus conference survey. During the conference, the Clinical Investigation Committee made several announcements regarding the presence of the Omnibus Survey on the conference’s online platform and welcomed participation. Participation was voluntary and respondents were informed of the nature of the study, risks and benefits of participation, and participants’ ability to skip specific sets of questions. Responses were collected anonymously via an online audience response system. Medical student and non-clinician responses were excluded from our analyses. This article was prepared in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

Outcomes and Covariates

Using multiple choice and Likert-type questions (see Supplemental Table), 5 binary outcomes were created to assess clinician perceptions: (1) likelihood of willingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormones (GAH; ie, would prescribe independently, with expert assistance, or with additional training; vs. would not prescribe), (2) belief in the ability to provide nonjudgmental care to TGD patients (ie, strongly agree/agree vs. other responses), (3) presence of ethical reasons for not prescribing GAH to an adult (yes vs. no), (4) routinely asking about sexuality, sexual practices, or gender identity when taking an adolescent psychosocial history (at least sometimes vs. rarely/never), and (5) belief additional training on gender-affirming care would benefit one’s practice (strongly agree/agree vs. other responses). Participant characteristics used as covariates in univariable and multivariable models included gender identity (male, female, TGD/prefer not to answer), service branch, practice setting, percent of time in clinical care, time since medical school graduation, provision of care to a patient with known gender dysphoria, hours of relevant education during medical school, residency, or after, and belief in receipt of sufficient education in provision of GAHs.

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the samples by study year. Five-level Likert variables were condensed into 2- or 3-level variables for analysis. Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare results to the same question across time. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to examine the effects of predictor variables on outcomes of interest from the 2023 dataset; the 2016 dataset was previously analyzed. 41 In select univariable models, 3 additional predictor variables were added, including identification as sexual- or gender-diverse, belief in the ability to provide nonjudgmental care to TGD individuals, and completion of family medicine residency. These variables were not added to the multivariable models due to relevance/priority or collinearity. Missing data were addressed with pairwise deletion.

Results

The response rates for the 2016 and 2023 surveys were n = 180 (68%) and n = 386 (69%), respectively. The majority of our sample reported a male gender identity, were >10 years beyond medical school graduation, and practiced in academic settings (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics by Survey Group.

| Characteristic | 2016 survey (n = 180) | % [95% CI] | 2023 survey (n = 386) | % [95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity, no. (%) | .027 | ||||

| Male | 113 | 63.5 [56.1-70.3] | 208 | 53.9 [48.9-58.8] | — |

| Female | 65 | 36.5 [29.7-43.9] | 171 | 44.3 [39.4-49.3] | — |

| TGD/Prefer not to answer | 0 | — | 7 | 1.8 [0.9-3.8] | — |

| Branch of service, no. (%) | .340 | ||||

| Air force | 69 | 39.4 [32.4-46.9] | 125 | 32.4 [27.9-37.2] | — |

| Army | 57 | 32.6 [26.0-39.9] | 131 | 33.9 [29.4-38.8] | — |

| Navy | 31 | 17.7 [12.7-24.1] | 75 | 19.4 [15.8-23.7] | — |

| Other | 18 | 10.3 [6.6-15.8] | 55 | 14.3 [11.1-18.1] | — |

| Practice setting, no. (%) | .585 | ||||

| Academic | 95 | 54.0 [46.5-61.3] | 198 | 51.3 [46.3-56.3] | — |

| Non-academic | 81 | 46.0 [38.7-53.5] | 188 | 48.7 [43.7-53.7] | — |

| Time in clinical care, no. (%) | .241 | ||||

| ≤50% | 90 | 50 [42.7-57.3] | 172 | 44.7 [39.8-49.7] | — |

| >50% | 90 | 50 [42.7-57.3] | 213 | 55.3 [50.3-60.2] | — |

| Time since medical school graduation, no. (%) | — | ||||

| <5 years | — | — | 120 | 31.1 [26.7-35.9] | — |

| 5-10 years | — | — | 98 | 25.4 [21.3-30.0] | — |

| >10 years | — | — | 168 | 43.5 [38.6-48.5] | — |

| Completion of family medicine residency, no. (%) | .120 | ||||

| Completed | 141 | 78.3 [71.7-83.8] | 264 | 71.9 [67.1-76.3] | — |

| Not completed | 39 | 21.7 [16.2-28.3] | 103 | 28.1 [23.7-32.9] | — |

| Identify as sexual and/or gender diverse, no. (%) | — | ||||

| Yes | — | — | 30 | 7.8 [5.5-10.9] | — |

| No | — | — | 348 | 90.2 [86.7-92.8] | — |

| Prefer not to answer | — | — | 8 | 2.1 [1.0-4.1] | — |

Abbreviation: TGD, transgender/gender-diverse.

Fisher’s exact test was used to determine P values. The P value represents the overall significance and compares the proportions of each characteristic between 2016 and 2023. Medical students were already subtracted from the n of each survey.

Table 2.

Comparison of Participant Responses by Survey Group.

| Characteristic | 2016 survey (n = 180) | % [95% CI] | 2023 survey (n = 386) | % [95% CI] | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During medical school and residency, I have received _ hours of didactic training on providing healthcare to transgender people. | <.001 | ||||

| 0 h | 130 | 74.3 [67.2-80.3] | 162 | 43.7 [38.7-48.8] | |

| 1-3 h | 36 | 20.6 [15.2-27.3] | 138 | 37.2 [32.4-42.2] | |

| 4+ h | 9 | 5.1 [2.7-9.6] | 71 | 19.1 [15.4-23.5] | |

| After residency, I have received _ hours of didactic training on providing healthcare to transgender people. | — | ||||

| 0 h | — | — | 123 | 34.6 [29.8-39.7] | |

| 1-3 h | — | — | 149 | 41.9 [36.8-47.1] | |

| 4+ h | — | — | 84 | 23.6 [19.5-28.3] | |

| I have received sufficient education on provision of hormone therapy for adult patients determined ready for gender affirmation/transition. | <.001 | ||||

| Strongly agree/agree | 9 | 5.3 [2.7-9.8] | 73 | 19.7 [15.9-24.1] | |

| Neutral | 13 | 7.6 [4.4-12.7] | 86 | 23.2 [19.2-27.8] | |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 149 | 87.1 [81.2-91.4] | 212 | 57.1 [52.0-62.1] | |

| Since getting my license, I have provided primary care to military or non-military patients with known gender dysphoria. | <.001 | ||||

| 0 patients | 111 | 62.7 [55.3-69.6] | 73 | 19.8 [16.0-24.2] | |

| 1 patient | 31 | 17.5 [12.6-23.9] | 58 | 15.7 [12.3-19.8] | |

| 2+ patients | 35 | 19.8 [14.5-26.3] | 238 | 64.5 [59.5-69.2] | |

| Exposure to openly transgender Service members, either informally or in a simulated training environment, would help me to feel more comfortable caring for transgender patients. | .007 | ||||

| Strongly agree/agree | 89 | 50.6 [43.2-57.9] | 195 | 52.7 [47.6-57.8] | |

| Neutral | 49 | 27.8 [21.7-35.0] | 132 | 35.7 [30.9-40.7] | |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 38 | 21.6 [16.1-28.3] | 43 | 11.6 [8.7-15.3] | |

| I believe I can provide nonjudgmental care to an individual with gender dysphoria during an office visit. | .045 | ||||

| Strongly agree/agree | 130 | 76.0 [69.0-81.9] | 315 | 84.7 [80.6-88.0] | |

| Neutral | 28 | 16.4 [11.5-22.7] | 42 | 11.3 [8.4-14.9] | |

| Disagree/strongly Disagree | 13 | 7.6 [4.4-12.7] | 15 | 4.0 [2.4-6.6] | |

| I would personally prescribe gender-affirming hormones to an adult patient with known gender dysphoria. | .001 b | ||||

| Yes - TOTAL | 82 | 47.1 [39.8-54.6] | 231 | 62.3 [57.2-67.1] | |

| Yes - independently | 1 | 0.6 | 32 | 8.6 | |

| Yes - after additional education | 13 | 7.2 | 58 | 15.6 | |

| Yes - with direct assistance from an experienced clinician | 30 | 16.7 | 56 | 15.1 | |

| Yes - with both additional education and direct assistance from an experienced clinician | 38 | 21.1 | 85 | 22.9 | |

| No - TOTAL | 92 | 52.9 [45.4-60.2] | 140 | 37.7 [32.9-42.8] | |

| No - because of ethical concerns | 14 | 7.8 | 38 | 10.2 | |

| No - because of lack of comfort c | 34 | 18.9 | 42 | 11.3 | |

| No - because of both ethical concerns & lack of comfort | 44 | 24.4 | 60 | 16.2 | |

| No response | 5 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| For routine adolescent encounters, do you ask at least 1 question about sexuality, sexual practices, or gender identity | — | ||||

| At least sometimes a | — | — | 321 | 87.2 [83.4-90.3] | |

| Never or rarely | — | — | 47 | 12.8 [9.7-16.6] | |

| Additional training on transgender and gender-diverse health would benefit my current/future practice. | — | ||||

| Strongly agree/agree | — | — | 224 | 60.5 [55.5-65.4] | |

| Neutral | — | — | 90 | 24.3 [20.2-29.0] | |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | — | — | 56 | 15.1 [11.8-19.2] | |

Fisher’s exact test was used to determine P values. The P value represents the overall significance and compares the proportions of each characteristic between 2016 and 2023. Medical students were already subtracted from the n of each survey.

The response “At least sometimes” includes responses for Always, Usually, and Sometimes.

P value only for yes vs no totals.

Lack of comfort other than ethical concerns.

Time-Trend Analyses

The 2023 participants were more likely to report a female gender identity than those in 2016 (44% vs 37%, P = .027); approximately 8% of the 2023 sample identified as sexual and/or gender-diverse (not assessed in 2016). There were no statistical differences between cohorts regarding service branch, practice setting, time in clinical care, or completion of residency over time. Compared to those surveyed in 2016, those surveyed in 2023 reported more didactic hours in providing healthcare for TGD people during undergraduate and graduate medical education, reflecting a 41% decrease in the percentage of clinicians reporting 0 h of relevant education (74% vs 44% receiving no training, P < .001). In 2023, 66% reported additional training after completion of formal education, and there was a 226% increase in the number of physicians reporting caring for ≥2 patients with gender dysphoria (65% in 2023 vs 20% in 2016, P < .001). Those in 2023 were also more likely to report having received sufficient education on the provision of gender-affirming medical care (P < .001) and believed they could provide nonjudgmental gender-affirming care (85% in 2023 vs 76% in 2016; P = .045; Figure 1).

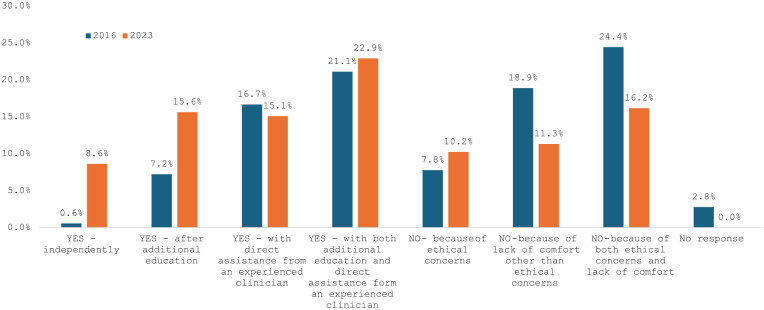

Figure 1.

Willingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormones.

Compared to 2016, 2023 respondents were also more likely to express willingness to prescribe GAH to an eligible adult patient either independently or with additional education and/or assistance from an experienced clinician (62% vs 47%; P = .001; Figure 1). Of the 37% who would not prescribe hormone therapy in 2023, 10% reported ethical concerns, 11% reported a lack of comfort, and 16% reported both ethical concerns and a lack of comfort. Despite the greater training reported in the 2023 cohort, over half of respondents (61%) agreed that additional training in TGD healthcare would benefit their clinical practice.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of 2023 Participants

Willingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormones

In univariable analysis, female-identifying (OR = 2.6, 95%CI = 1.7-4.1) and sexual- or gender-diverse (OR = 3.16, 95%CI = 1.18-8.5) participants were more likely to report willingness to prescribe GAH than their peers (Table 3). Similarly, greater willingness to prescribe GAH was reported among: (1) those with ≥4 h of total education in gender-affirming healthcare (OR = 2.2, 95%CI = 1.1-4.2) compared to <4 h; (2) those who reported the ability to provide nonjudgmental care (OR = 9.4, 95%CI = 2.59-34.1) compared to those who do not (note that those with a neutral response were not statistically different from those who disagree/strongly disagree); (3) those in academic medical settings (OR = 1.59, 95%CI = 1.04-2.43) compared those not in academic settings; and (4) those who had provided primary care to ≥1 TGD person (ORs = 1.84-2.28) compared to those who have not provided such care. Service branch, time in clinical care, time since medical school graduation, and completion of residency were not significantly related to willingness to prescribe GAH. In multivariable analysis controlling for relevant covariates, findings persisted for female-identifying participants (aOR = 3.05, 95%CI = 1.84-5.07), those who had provided care for ≥1 TGD patient (aOR = 2.42, 95%CI = 1.08-5.43), and those with ≥4 h of training (aOR = 2.41, 95%CI = 1.07-5.42) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariable Logistic Regression Examining Participant Characteristics on Outcomes of Interest (2023 Data).

| Ethical reasons for not prescribing gender affirming hormones to an adult b (N = 371) | Belief one provides nonjudgmental care to transgender patients b (N = 372) | Likelihood of willingness to prescribe gender affirming hormones b (N = 371) | Routinely asking about sexuality, sexual practices or gender identity when taking an adolescent psychosocial history b (N = 368) | Belief additional training on provision of healthcare to TGD people would benefit one’s practice b (N = 370) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Gender identity | ||||||||||

| Male | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Female | 0.31 (0.19-0.52) | <.001 | 1.61 (0.90-2.91) | .11 | 2.61 (1.67-4.08) | <.01 | 2.38 (1.21-4.68) | .01 | 5.26 (3.25-8.50) | <.01 |

| TGD/Prefer not to answer | 0.90 (0.16-5.05) | .907 | — | — | 1.81 (0.32-10.11) | .50 | — | — | 1.24 (0.25-6.31) | .79 |

| Branch of service | ||||||||||

| Air force | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Army | 1.40 (0.81-2.44) | .222 | 0.46 (0.22-0.97) | .04 | 0.63 (0.37-1.05) | .08 | 0.80 (0.37-1.75) | .59 | 0.67 (0.40-1.13) | .13 |

| Navy | 0.46 (0.21-0.99) | .049 | 0.68 (0.28-1.67) | .40 | 1.35 (0.71-2.58) | .36 | 0.73 (0.30-1.77) | .49 | 1.04 (0.56-1.93) | .91 |

| Other | 0.97 (0.47-2.02) | .942 | 0.43 (0.18-1.05) | .06 | 0.53 (0.28-1.02) | .06 | 0.68 (0.26-1.75) | .42 | 0.52 (0.27-1.00) | .05 |

| Practice setting | ||||||||||

| Academic | 1.09 (0.69-1.73) | .715 | 0.74 (0.42-1.31) | .30 | 1.59 (1.04-2.43) | .03 | 2.62 (1.37-5.03) | <.01 | 1.40 (0.92-2.12) | .12 |

| Non-academic | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Time in clinical care | ||||||||||

| ≤50% | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| >50% | 1.10 (0.69-1.76) | .677 | 1.00 (0.57-1.77) | .99 | 0.93 (0.61-1.42) | .75 | 0.65 (0.34-1.23) | .18 | 1.05 (0.69-1.59) | .83 |

| Time since medical school graduation | ||||||||||

| <5 years | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 5-10 years | 1.02 (0.56-1.86) | .957 | 0.86 (0.39-1.90) | .70 | 0.89 (0.51-1.57) | .70 | 1.53 (0.64-3.67) | .34 | 0.85 (0.48-1.50) | .58 |

| >10 years | 0.74 (0.43-1.29) | .291 | 0.67 (0.34-1.34) | .26 | 0.99 (0.60-1.63) | .97 | 0.93 (0.46-1.88) | .84 | 0.75 (0.45-1.23) | .26 |

| Completion of family medicine residency | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.86 (0.51-1.46) | .578 | 1.13 (0.59-2.16) | .72 | 0.89 (0.54-1.45) | 0.64 | 1.15 (0.57-2.30) | .70 | 0.84 (0.51-1.37) | .48 |

| No | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Provision of primary care to a patient with known gender dysphoria since becoming licensed | ||||||||||

| 0 patients | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 1 patient | 0.74 (0.34-1.61) | .446 | 2.05 (0.82-5.12) | .126 | 2.28 (1.11-4.70) | .025 | 0.86 (0.36-2.05) | .727 | 1.65 (0.82-3.34) | .159 |

| 2+ patients | 0.82 (0.46-1.46) | .504 | 2.19 (1.14-4.20) | .019 | 1.84 (1.08-3.12) | .024 | 2.36 (1.11-5.00) | .025 | 1.92 (1.13-3.29) | .017 |

| Hours of education on provision of healthcare to TGD people a | ||||||||||

| 0 h | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 1-3 h | 0.91 (0.47-1.79) | .796 | 0.54 (0.22-1.31) | .17 | 0.88 (0.47-1.65) | .69 | 3.06 (1.44-6.52) | <.01 | 1.02 (0.54-1.92) | .96 |

| 4+ h | 0.53 (0.26-1.05) | .070 | 1.52 (0.59-3.97) | .39 | 2.19 (1.15-4.20) | .02 | 6.95 (2.91-16.61) | <.01 | 1.28 (0.68-2.42) | .45 |

| Belief one can provide nonjudgmental care to transgender patients | ||||||||||

| Strongly agree/agree | REF | — | N/A | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Neutral | 9.15 (4.48-18.72) | <.001 | — | — | 0.09 (0.04-0.20) | <.01 | 0.56 (0.24-1.29) | .17 | 0.09 (0.04-0.22) | <.01 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 8.50 (2.80-25.79) | <.001 | — | — | 0.11 (0.03-0.39) | <.01 | 0.87 (0.19-4.03) | .86 | 0.07 (0.02-0.32) | <.01 |

| Received sufficient education on provision of hormone therapy | ||||||||||

| Strongly agree/agree | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Neutral | 1.44 (0.73-2.85) | .29 | 0.40 (0.16-1.02) | .06 | 0.42 (0.22-0.81) | .01 | 0.50 (0.17-1.52) | .22 | 0.73 (0.39-1.38) | .33 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 0.78 (0.42-1.42) | .41 | 0.60 (0.25-1.42) | .24 | 0.79 (0.44-1.40) | .42 | 0.44 (0.16-1.17) | .10 | 3.09 (1.78-5.39) | <.01 |

| Identify as sexual and/or gender diverse | ||||||||||

| No | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Yes | 0.19 (0.04-0.81) | .03 | 5.6 (0.75-42.0) | .094 | 3.16 (1.18-8.50) | .022 | 0.70 (0.25-1.92) | .483 | 3.42 (1.27-9.19) | .015 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1.03 (0.20-5.38) | .98 | 1 | — | 1.65 (0.32-8.60) | .555 | 1 | — | 1.78 (0.34-9.32) | .494 |

Abbreviations: REF, reference population (from which odds ratios for the other variable categories were calculated); TGD, transgender/gender-diverse.

Combined data from education “during medical school and residency” and “after residency.”

Binary outcome (ie, yes/no).

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Examining Participant Characteristics on Outcomes of Interest (2023 Data).

| Variable | Ethical reasons for not prescribing gender affirming hormones to an adult b (N = 371) | Belief one provides nonjudgmental care to transgender patients b (N = 372) | Likelihood of willingness to prescribe gender affirming hormones b (N = 371) | Routinely asking about sexuality, sexual practices or gender identity when taking an adolescent psychosocial history b (N = 368) | Belief additional training on provision of healthcare to TGD people would benefit one’s practice b (N = 370) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Gender identity | ||||||||||

| Male | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Female | 0.27 (0.16-0.49) | <.001 | 1.65 (0.87-3.14) | .126 | 3.05 (1.84-5.07) | <.001 | 2.69 (1.27-5.70) | .010 | 5.03 (2.96-8.54) | <.001 |

| TGD/prefer not to answer | 1.05 (0.16-7.00) | .96 | 1.00 | — | 1.52 (0.21-11.25) | .682 | 1.00 | — | 0.82 (0.12-5.42) | .839 |

| Branch of service | ||||||||||

| Air force | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | |

| Army | 1.22 (0.67-2.25) | .518 | 0.53 (0.24-1.17) | .115 | 0.76 (0.43-1.36) | .355 | 0.93 (0.38-2.25) | .869 | 0.70 (0.38-1.30) | .257 |

| Navy | 0.41 (0.17-0.95) | .038 | 0.80 (0.30-2.10) | .647 | 1.79 (0.86-3.71) | .117 | 0.73 (0.27-2.02) | .550 | 1.23 (0.59-2.55) | .587 |

| Other | 1.00 (0.41-2.46) | .991 | 0.59 (0.20-1.67) | .316 | 0.57 (0.25-1.29) | .174 | 1.18 (0.37-3.78) | .783 | 0.71 (0.30-1.71) | .449 |

| Practice setting | ||||||||||

| Academic | 1.27 (0.72-2.22) | .408 | 0.43 (0.22-0.86) | .018 | 1.41 (0.84-2.37) | .191 | 2.30 (1.02-5.16) | .044 | 1.14 (0.67-1.97) | .627 |

| Non-academic | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Time in clinical care | ||||||||||

| ≤50% | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| >50% | 0.98 (0.51-1.89) | .955 | 0.62 (0.29-1.34) | .227 | 0.89 (0.49-1.62) | .709 | 0.36 (0.15-0.88) | .024 | 0.81 (0.44-1.50) | .500 |

| Time since medical school graduation | ||||||||||

| <5 years | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 5-10 years | 1.33 (0.62-2.84) | .469 | 0.43 (0.16-1.14) | .091 | 0.76 (0.37-1.55) | .450 | 1.42 (0.49-4.17) | .520 | 0.48 (0.22-1.03) | .058 |

| >10 years | 0.61 (0.26-1.48) | .276 | 0.36 (0.12-1.06) | .065 | 1.54 (0.69-3.43) | .296 | 1.02 (0.32-3.17) | .979 | 0.73 (0.31-1.68) | .456 |

| Provision of primary care to a patient with known gender dysphoria since becoming licensed | ||||||||||

| 0 patients | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 1 patient | 0.81 (0.34-1.92) | .626 | 2.48 (0.92-6.66) | .071 | 2.42 (1.08-5.43) | .032 | 0.67 (0.25-1.78) | .419 | 1.40 (0.60-3.15) | .446 |

| 2+ patients | 1.01 (0.52-1.97) | .965 | 2.78 (1.31-5.91) | .008 | 1.65 (0.89-3.04) | .109 | 1.80 (0.78-4.18) | .170 | 2.00 (1.03-3.90) | .041 |

| Hours of education on provision of healthcare to TGD people a | ||||||||||

| 0 h | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| 1-3 h | 0.88 (0.40-1.94) | .758 | 0.47 (0.18-1.25) | .130 | 0.68 (0.32-1.42) | .299 | 3.13 (1.27-7.68) | .013 | 0.84 (0.38-1.87) | .676 |

| 4+ h | 0.28 (0.12-0.69) | .005 | 1.50 (0.49-4.58) | .478 | 2.41 (1.07-5.42) | .033 | 5.53 (1.89-16.19) | .002 | 2.40 (1.00-5.74) | .050 |

| Received sufficient education on provision of hormone therapy | ||||||||||

| Strongly agree/agree | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — | REF | — |

| Neutral | 1.10 (0.51-2.38) | .807 | 0.59 (0.21-1.63) | .310 | 0.49 (0.23-1.04) | .065 | 0.59 (0.17-2.00) | .397 | 0.95 (0.45-1.98) | .887 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 0.56 (0.27-1.17) | .125 | 0.91 (0.34-2.42) | .845 | 0.99 (0.49-1.98) | .976 | 0.59 (0.19-1.86) | .370 | 4.72 (2.33-9.56) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: REF, reference population (from which adjusted odds ratios for the other variable categories were calculated); TGD, transgender/gender-diverse.

Combined data from education “during medical school and residency” and “after residency”.

Binary outcome (ie, yes/no).

Likelihood of reporting nonjudgmental care

Those who reported caring for ≥2 patients with gender dysphoria were more likely to report belief in their ability to provide nonjudgmental care (OR = 2.19, 95%CI = 1.14-4.20) compared to those who did not report caring for a person with gender dysphoria, a finding that persisted in multivariable analysis (aOR = 2.78, 95%CI = 1.31-5.91). Those who provided care to ≥1 patient did not significantly differ from those who had not. In univariable but not multivariable analysis, Army Service members were less likely to report belief in their ability to provide nonjudgmental care (OR = 0.46, 95%CI = 0.22-0.97) compared to Air Force Service members.

Likelihood of ethical concern

Female-identifying respondents (OR = 0.31, 95%CI = 0.19-0.52) had lower odds of reporting ethical concerns as a barrier to prescribing GAH to an adult patient than male-identifying respondents; this finding persisted in multivariable analysis (aOR = 0.27, 95%CI = 0.16-0.49). Those who reported an inability to provide nonjudgmental care were also more likely to report ethical reasons as a barrier to prescribing (neutral regarding the ability to provide nonjudgmental care: OR = 9.15, 95%CI = 4.48-18.72; disagreement response regarding the ability to provide nonjudgmental care: OR = 8.5, 95%CI = 2.8-25.79); this was not assessed in multivariable analysis. In both univariable and multivariable analyses, those in the Navy were less likely to report ethical concerns than those in the Air Force.

Belief that additional training would benefit one’s practice

In univariable analyses, female-identifying (OR = 5.26, 95%CI = 3.25-8.5) and sexual- or gender-diverse (OR = 3.42, 95%CI = 1.28-9.19) participants were more likely to report that additional education in TGD healthcare would benefit their practice compared to their peers. Similarly, there were greater odds of reporting that additioning training would be beneficial by those who provided primary care to ≥2 TGD patients (compared to 0 TGD patients; OR = 1.92, 95%CI = 1.13-3.29) and by those who indicated they had insufficient education (compared to those who reported sufficient education; OR = 3.09, 95%CI = 1.78-5.39). Compared to those who agreed that they could provide nonjudgemental care, those who were neutral (OR = 0.09, 95%CI = 0.04-0.22) or who disagreed (OR = 0.07, 95%CI = 0.02-0.32) were less likely to report that additional training would be beneficial. In multivariable analyses, the findings regarding female-identifying participants, those caring for ≥2 patients, and those who disagreed they have had sufficient education persisted. Furthermore, those who reported a willingness to prescribe GAH were more likely than others to report that additional training would benefit their practice (OR = 12.0, 95%CI = 7.26-19.79).

Discussion

In this serial cross-sectional study examining clinician perspectives on gender-affirming care in 2016 and 2023, we found that clinicians’ education on, experience with, and willingness to participate in gender-affirming care increased significantly. However, 2023 data show that inequities may exist: female-identifying clinicians, those who identify as sexual or gender-diverse, those with ≥4 h of education, and those who report being able to provide nonjudgmental care have twofold to tenfold greater odds of reporting a willingness to prescribe GAH to a patient than comparator groups. These clinician groups also demonstrated significant findings within multiple other outcomes (see Tables 3 and 4), suggesting that patient experience may differ markedly depending on the clinician assigned. Given that patients may have little agency in selecting their primary care clinician and may not know a clinician’s practice style or training in gender-affirming care during their selection of or assignment to a primary care clinician, processes to ensure timely and accurate patient handoffs to clinicians willing to provide high-quality and evidence-based care may be crucial to optimizing care outcomes.

Clinician Willingness to Provide Gender-Affirming Care for TGD Patients: 2016 and 2023

Clinicians in 2023 reported more willingness to prescribe GAH for an adult patient independently or with additional education than clinicians in 2016. A contributing factor could be the larger percentage of female-identifying clinicians surveyed in 2023 relative to 2016, who demonstrated greater odds of reporting the willingness to provide gender-affirming care compared to male-identifying participants. This trend also occurred as clinicians reported greater exposure to TGD patients (eg, 226% increase between 2016 to 2023 in physicians reporting caring for ≥2 TGD patients). Similarly, the proportion of respondents who had received ≥1 h of didactics on TGD healthcare during their medical training increased by 119%. This apparent shift in curriculum is likely reflective of expanding social awareness toward the TGD community, and new guidelines from multiple medical societies and government agencies over the past decade.4,28

Our study also demonstrated changing attitudes toward TGD patients; the number of physicians who felt they could not provide nonjudgmental care decreased by 47% from 2016 to 2023. Notably, the belief in one’s ability to provide nonjudgmental care was associated with the number of TGD patients cared for. Conversely, the belief one could not provide nonjudgmental care was associated with greater odds of citing “ethical reasons” for not prescribing GAH.

Prior research indicates that clinicians with less exposure to or education on gender-affirming care are less likely to report willingness to provide such care.11,19,32,42 Alternatively, clinicians may not seek training or patient care experiences outside their areas of clinical interest. In the US, there have been limited studies examining hours of relevant education in medical education curricula; the median time allocated in US programs was 5 h, with gender-affirming therapies much less frequently addressed compared to topics on HIV, gender identity, safe sex, and sexual orientation. 25 A more recent survey of 160 residency programs reported an average of 11 h spent on transgender health, although areas such as adolescent health, transitioning, chronic disease risk, and surgery were noted by 30% to 50% of residency directors to receive minimal coverage. 24 Recent studies reviewing medical education in Europe and Korea reveal the topic of gender-affirming care is often excluded or missing from the broadly accepted curricula.43,44 With only 19% of participants in 2023 who reported ≥4 h of relevant education during their medical training, our study highlights the variation in contemporary training.

Special Clinician Populations Who May Be More Likely to Serve TGD Patients

Our models indicated that female-identifying clinicians had significantly greater odds of prescribing GAH to an adult, routinely asking about sexuality, sexual practices, or gender identity when taking an adolescent psychosocial history, and believing that additional training would benefit their practice, compared to male-identifying peers. Female-identifying clinicians were also significantly less likely to cite ethical reasons for not providing gender-affirming care. Similar trends were found among sexual/gender-diverse clinicians. The results of the current study are consistent with prior research suggesting more positive attitudes toward the TGD community among female and sexual/gender-diverse clinicians,45,46 though the current study is novel in examining sex and gender differences in family physicians’ willingness to prescribe GAH. Differences may be related to variance in empathy, as unrelated research has shown cisgender women often score higher than men on measures of empathy.47 -49 Sexual and gender diverse clinicians are also more likely to seek out relevant education and be more aware of the stigma faced by their patients. 50

Possible Correlates of Additional Training

Similar to prior research,51 -53 the majority (61%) of respondents agreed that additional training on gender-affirming care would benefit their practice, signaling both the need and desire for greater training in this area. Indeed, clinical guidelines by multiple medical organizations can support physicians in providing gender-affirming care,4,54,55 and improvements in medical education to address inequities in care provision and access are on the rise.4,30,56

In our study, those who did not believe in their ability to provide nonjudgmental care had significantly lower odds of reporting additional training would be beneficial to their practice, whereas those who reported willingness to prescribe GAH were 12 times more likely than those who did not to report a training benefit, suggesting that robust education alone may not guarantee optimal clinical care environments. Notably, those with ≥4 h of training may have special interest in caring for sexual- or gender-diverse patients, making them more likely to have affirming responses. Nevertheless, there is evidence that small increases in education on gender-affirming care can improve trainees’ comfort and willingness to provide such care. 26 Many clinicians in the study population, however, appear to indicate an interest in advanced training, and efforts to expand training opportunities for those who seek it may greatly impact patient outcomes.

Limitations

As with other survey research, this study may have been subject to recall and participation/non-response bias. Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, it was not possible to identify individuals who completed both the 2016 and 2023 surveys; however, changeover in military personnel and the duration of time passed suggest the number of respondents taking the survey both years may be limited. This topic is prone to social desirability and acquiesce bias, although selection and sampling bias was likely minimal. The study was also limited by the small number of clinicians identifying as TGD in 2023 (not assessed in 2016). To maintain anonymity, TGD respondents were combined with the small number of individuals who reported their gender identity as “prefer not to answer,” thereby precluding us from exploring perceptions of care among TGD clinicians specifically. Missing data may be due to technological difficulties or respondent preferences in answering a given question. The extent to which the culture of military-affiliated family physicians differs from the broad US family medicine specialty is not known, and we acknowledge that differences between military and civilian family physician populations, if any, may impact the generalizability of our study’s results.

Conclusions

Although military-affiliated family physicians endorsed more experience with and willingness to provide nonjudgmental gender-affirming care in 2023 than in 2016, profound gaps in patient experience may remain based on the assigned clinician. Clinicians unable to provide gender-affirming care should ensure timely referrals. Basic education is becoming more available to address the needs of TGD patients, and advanced training opportunities should be available for those positioned and willing to provide such care. Future research is needed to explore trends across specialties and the effectiveness of educational efforts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241264193 for Military Family Physicians’ Readiness to Provide Gender-Affirming Care: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study by Kryls O. Domalaon, Austin M. Parsons, Jennifer A. Thornton, Kent H. Do, Christina M. Roberts, Natasha A. Schvey and David A. Klein in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpc-10.1177_21501319241264193 for Military Family Physicians’ Readiness to Provide Gender-Affirming Care: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study by Kryls O. Domalaon, Austin M. Parsons, Jennifer A. Thornton, Kent H. Do, Christina M. Roberts, Natasha A. Schvey and David A. Klein in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: Christina M. Roberts is now affiliated to Department of Pediatrics, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Authors’ Note: Presentations: This work was presented at the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine’s National Meeting and the Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physician’s Meeting, both in March of 2024.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Roberts has previously received funding from Organon for contraception research (Organon investigator initiated grant program). she is no longer funded by Organon.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Open Access fees were be supported by the 60th MDG Clinical Investigation Facility, Travis AFB.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Uniformed Services University, the US Air Force, the US Department of Defense or the US government.

ORCID iD: Kryls O. Domalaon  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9945-1538

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9945-1538

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Boskey ER, Quint M, Xu R, et al. Gender affirmation-related information-seeking behaviors in a diverse sample of transgender and gender-diverse young adults: survey study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e45952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? Williams Institute; 2022. Accessed December 2, 2023. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(1):S1-S259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):e1-e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garnier M, Ollivier S, Flori M, Maynié-François C. Transgender people’s reasons for primary care visits: a cross-sectional study in France. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e036895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Belkin A. Caring for Our transgender troops–The negligible cost of transition-related care. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1089-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schaefer AG, Plumb RI, Kadiyala S, et al. Assessing the Implications of Allowing Transgender Personnel to Serve Openly. RAND Corporation; 2016. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1530.html [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnston CD, Shearer LS. Internal medicine resident attitudes, prior education, comfort, and knowledge regarding delivering comprehensive primary care to transgender patients. Transgend Health. 2017;2(1):91-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soled KRS, Dimant OE, Tanguay J, Mukerjee R, Poteat T. Interdisciplinary clinicians’ attitudes, challenges, and success strategies in providing care to transgender people: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vance SR, Jr, Halpern-Felsher BL, Rosenthal SM. Health care providers’ comfort with and barriers to care of transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):251-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rider GN, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, Coleman E, Eisenberg ME. Health and care utilization of transgender and gender nonconforming youth: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20171683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alpert AB, CichoskiKelly EM, Fox AD. What lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex patients say doctors should know and do: a qualitative study. J Homosex. 2017;64(10):1368-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stroumsa D, Crissman HP, Dalton VK, Kolenic G, Richardson CR. Insurance coverage and use of hormones among transgender respondents to a national survey. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(6):528-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Movement Advancement Project. Equality Maps: Healthcare Laws and Policies. Movement Advancement Project. Updated April 26, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare_laws_and_policies

- 17. Johnson N, Pearlman AT, Klein DA, Riggs DS, Schvey NA. Stigma and barriers in healthcare among a sample of transgender and gender-diverse active duty service members. Med Care. 2023;61(3):145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schvey NA, Klein DA, Pearlman A, Kraff R, Riggs D. Stigma, health, and psychosocial functioning among transgender active duty service members in the U.S. Military. Stigma Health. 2020;5(2):188-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shires DA, Prieto LR, Woodford MR, Jaffee KD, Stroumsa D. Gynecological providers’ willingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender patients. Transgend Health. 2022;7(4):323-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kattari SK, Bakko M, Langenderfer-Magruder L, Holloway BT. Transgender and nonbinary experiences of victimization in health care. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(23-24):NP13054-NP13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.ustranssurvey.org/reports/#2015report [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boonyapisomparn N, Manojai N, Srikummoon P, Bunyatisai W, Traisathit P, Homkham N. Healthcare discrimination and factors associated with gender-affirming healthcare avoidance by transgender women and transgender men in Thailand: findings from a cross-sectional online-survey study. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lutwak N, Byne W, Erikson-Schroth L, et al. Transgender veterans are inadequately understood by health care providers. Military Med. 2014;179(5):483-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kopel J, Beck N, Almekdash MH, Varma S. Trends in transgender healthcare curricula in graduate medical education. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2023;36(5):620-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG, Jr, Greene RE, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Donovan M, VanDerKolk K, Graves L, McKinney VR, Everard KM, Kamugisha EL. Gender-affirming care curriculum in family medicine residencies: a CERA Study. Fam Med. 2021;53(9):779-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hersh BJ, Rdesinski RE, Milano C, Cantone RE. An effective gender-affirming care and hormone prescribing standardized patient case for residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Heesewijk J, Kent A, van de Grift TC, Harleman A, Muntinga M. Transgender health content in medical education: a theory-guided systematic review of current training practices and implementation barriers & facilitators. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2022;27(3):817-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dowshen N, Nguyen GT, Gilbert K, Feiler A, Margo KL. Improving transgender health education for future doctors. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e5-e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rider GN, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, Coleman E, Brown C, Eisenberg ME. Perspectives from nurses and physicians on training needs and comfort working with transgender and gender-diverse youth. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(4):379-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marshall SA, Stewart MK, Barham C, Ounpraseuth S, Curran G. Facilitators and barriers to providing affirming care for transgender patients in primary care practices in Arkansas. J Rural Health. 2023;39(1):251-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shires DA, Stroumsa D, Jaffee KD, Woodford MR. Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):555-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tutić Grokša I, Doričić R, Branica V, Muzur A. Caring for transgender people in healthcare: a qualitative study with hospital staff in Croatia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Armuand G, Dhejne C, Olofsson JI, Stefenson M, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA. Attitudes and experiences of health care professionals when caring for transgender men undergoing fertility preservation by egg freezing: a qualitative study. Ther Adv Reprod Health. 2020;14:2633494120911036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Madera SL, Díaz NV, Padilla M, et al. “Just like any other patient”: transgender stigma among physicians in Puerto Rico. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(4):1518-1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vijay A, Earnshaw VA, Tee YC, et al. Factors associated with medical doctors’ intentions to discriminate against transgender patients in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. LGBT Health. 2018;5(1):61-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lambda Legal. When health Care Isn’t Caring: Lambda Legal’s Survey of Discrimination Against LGBT People and People With HIV. Lambda Legal; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reisner SL, Perez-Brumer AG, McLean SA, et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators to integrating HIV prevention and treatment with cross-sex hormone therapy for transgender women in Lima, Peru. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3299-3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sha Y, Dong W, Tang W, et al. Gender minority stress and access to health care services among transgender women and transfeminine people: results from a cross-sectional study in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holland D, White LCJ, Pantelic M, Llewellyn C. The experiences of transgender and nonbinary adults in primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2024;30(1):2296571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schvey NA, Blubaugh I, Morettini A, Klein DA. Military family physicians’ readiness for treating patients with gender dysphoria. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):727-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sharma A, Shaver JC, Stephenson RB. Rural primary care providers’ attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities in a midwestern state in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(4):5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burgwal A, Gvianishvili N, Hård V, et al. The impact of training in transgender care on healthcare providers competence and confidence: a cross-sectional survey. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(8):967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee SR, Kim MA, Choi MN, et al. Attitudes toward transgender people among medical students in South Korea. Sex Med. 2021;9(1):100278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rowan SP, Lilly CL, Shapiro RE, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of health care providers toward transgender patients within a rural tertiary care center. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):24-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dunlap SL, Holloway IW, Pickering CE, Tzen M, Goldbach JT, Castro CA. Support for transgender military service from active duty United States military personnel. Sex Res Social Policy. 2021;18(1):137-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pang C, Li W, Zhou Y, Gao T, Han S. Are women more empathetic than men? Questionnaire and EEG estimations of sex/gender differences in empathic ability. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2023;18(1):nsad008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elkin B, LaPlant EM, Olson APJ, Violato C. Stability and differences in empathy between men and women medical students: a panel design study. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(6):1851-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chaitoff A, Sun B, Windover A, et al. Associations between physician empathy, physician characteristics, and standardized measures of patient experience. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1464-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Westafer LM, Freiermuth CE, Lall MD, Muder SJ, Ragone EL, Jarman AF. Experiences of transgender and gender expansive physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cooper RL, Ramesh A, Radix AE, et al. Affirming and inclusive care training for medical students and residents to reduce health disparities experienced by sexual and gender minorities: a systematic review. Transgend Health. 2023;8(4):307-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arthur S, Jamieson A, Cross H, Nambiar K, Llewellyn CD. Medical students’ awareness of health issues, attitudes, and confidence about caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rowe D, Ng YC, O’Keefe L, Crawford D. Providers’ Attitudes and knowledge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. Fed Pract. 2017;34(11):28-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP reaffirms gender-affirming care policy, authorizes systematic review of evidence to guide update. AAP News. Published August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/25340/AAP-reaffirms-gender-affirming-care-policy

- 55. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Klein DA, Schvey NA, Baxter TA, Larson NS, Roberts CM. Caring for military-affiliated transgender and gender-diverse youths: a call for protections. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(3):251-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241264193 for Military Family Physicians’ Readiness to Provide Gender-Affirming Care: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study by Kryls O. Domalaon, Austin M. Parsons, Jennifer A. Thornton, Kent H. Do, Christina M. Roberts, Natasha A. Schvey and David A. Klein in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpc-10.1177_21501319241264193 for Military Family Physicians’ Readiness to Provide Gender-Affirming Care: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study by Kryls O. Domalaon, Austin M. Parsons, Jennifer A. Thornton, Kent H. Do, Christina M. Roberts, Natasha A. Schvey and David A. Klein in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health