Abstract

Background:

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1R) agonists have been approved by Food and Drug Administration for management of obesity. However, the causal relationship of GLP1R agonists (GLP1RA) with cancers still unclear.

Methods:

The available cis-eQTLs for drugs target genes (GLP1R) were used as proxies for exposure to GLP1RA. Mendelian randomizations (MR) were performed to reveal the association of genetically-proxied GLP1RA with 14 common types cancer from large-scale consortia. Type 2 diabetes was used as positive control, and the GWASs data including 80 154 cases and 853 816 controls. Replicating the findings in the FinnGen study and then pooled with meta-analysis. Finally, all the related randomized controlled trails (RCTs) on GLP1RA were systematically searched from PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library to comprehensively synthesize the evidence to validate any possible association with cancers.

Result:

A total of 22 significant cis-eQTL single-nucleotide polymorphisms were included as genetic instrument. The association of genetically-proxied GLP1RA with significantly decreased type 2 diabetes risk [OR (95%)=0.82 (0.79–0.86), P<0.001], which ensuring the effectiveness of identified genetic instruments. The authors found favorable evidence to support the association of GLP1RA with reduced breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma risk [0.92 (0.88–0.96), P<0.001, 0.92 (0.85–0.99), P=0.029, respectively], and with increased colorectal cancer risk [1.12 (1.07–1.18), P<0.001]. In addition, there was no suggestive evidence to support the association of GLP1RA with ovarian cancer [0.99 (0.90–1.09), P=0.827], lung cancer [1.01 (0.93–1.10), P=0760], and thyroid cancer [0.83 (0.63–1.10), P=0.187]. Our findings were consistent with the meta-analysis. Finally, 80 RCTs were included in the systematic review, with a low incidence of different kinds of cancer.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that GLP1RA may decrease the risk of breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma, but increase the risk of colorectal cancer. However, according to the systematic review of RCTs, the incidence of cancer in patients treated with GLP1RA is low. Larger sample sizes of RCTs with long-term follow-up are necessary to establish the incidence of cancers and evaluate the risk-benefit ratios.

Key words: cancers, drug target, GLP1R agonists, Mendelian randomization

Introduction

Highlights

Our study explored the causal relationship between GLP1R agonists (GLP1RA) and 14 cancers by Mendelian randomization and systematic review.

This study found the GLP1RA may decrease the risk of breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma, but increase the risk of colorectal cancer. The use of GLP1RA does not increase the risk of ovarian cancer, lung cancer, and thyroid cancer.

The systematic review of randomized controlled trails on GLP1RA showed a low incidence of different kinds of cancer.

Semaglutide, an agonist of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1R), was originally developed for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and has been granted supplemental approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 4 June 2021 for use in obese and overweight adult1. GLP1R is expressed in various tissues and organs, including the adipose, smooth muscle, lungs heart, kidney and pancreas, and specific nuclei of the central nervous system2. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1RA) are also considered for the therapy of prediabetes, liver disease, and neurodegenerative diseases2. A recent multicourse clinical trial suggests that weekly injections of semaglutide in overweight or obese patients without diabetes result in reduce the risk of death from cardiovascular events by 20%3.

However, as GLP1RA is approved for weight control in more countries around the world, it is unclear whether the potential side effects can be tolerated when treating millions of individuals with medications like semaglutide. The GLP1RA simulate gut hormones, in addition to causing the common gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, and increases pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, and gastroparesis4. A study reported that a remarkably increase in pancreatic cancer among patients who treated with GLP1RA5, but an extensive review of preclinical and clinical studies by FDA and EMA concluded that the causal relationship between GLP1RA and pancreatic adverse events was inconsistent6. What about long-term risks? However, no studies have been performed to systematically explored the possible risk between this drug target agonist and cancers.

Due to the lack of long-term randomized controlled trials of GLP1RA, Mendelian randomization (MR) can be conducted to assess causality relationship between GLP1RA and various types of cancer by using genetic variants in the GLP1R gene, and overcome the potential bias from confounding and reverse causation7. Drug target MR has been prioritized for clinical trial design, and multiple studies have explored the potential drug efficacy of different drug targets in related diseases8–11. Here, we performed an MR analysis to comprehensively explore the causal relationship between GLP1RA and 14 cancers. To verify and complement the MR results, we conducted a systematic review of RCTs on GLP1RA to investigate the association with cancers.

Methods

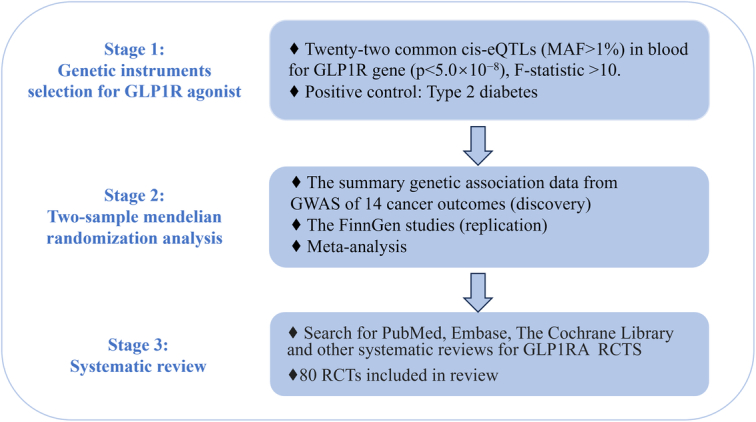

The overall investigation of this study is presented in Figure 1. We first select the genetic instruments for GLP1R and conducted a drug target MR to explore the causal relationship of the GLP1R gene activation with 14 cancer outcomes. We performed the positive control analysis to further examine the association of exposures of interest with type 2 diabetes to ensure the reliability of genetic instruments. We then repeated the analysis in the FinnGen study to confirm the findings of the drug target MR and meta-analysis the results. Finally, we try to systematic review the randomized controlled studies on GLP1RA to comprehensively synthesize the evidence to validate any possible association with cancers. All the studies included in our analysis have been approved by the relevant institutional review committee and obtained the informed consent from participants.

Figure 1.

Study design overall flowchart. eQTL, expression quantitative trait locus; GLP1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; MAF, minor allele frequency; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

MR analysis

Selection of genetic instruments

The GLP1R agonist which approved by FDA for blood glucose and weight-regulated drug was included as exposures in this study. As presented in Figure 1, the available cis-eQTLs for drugs target genes (GLP1R) were used as the proxy of exposure to the GLP1R agonists. The summary-level data for cis-eQTLs including 235 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were obtained from eQTLGen Consortium12 (https://www.eqtlgen.org/), the details of which are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). We selected the common (minor allele frequency>1%) cis-eQTLs SNPs significantly (P<5.0×10−8) associated with the expression of GLP1R in blood as instrumental variables. Moreover, the F-statistics>10 to ensure instrumental strength associated with exposure traits. In addition, we evaluated the association of the genetic instruments with type 2 diabetes to proxy the exposure of GLP1R agonists. Finally, considering possible pleiotropic effects of the genetic instruments on potential confounders, we excluded the pleiotropic SNPs that associated with other potential confounders through the PhenoScanner (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/).

Outcome sources

To avoid the potential bias due to diverse populations, we restricted the genetic background the population in our drug target MR to participants of European populations. we extracted type 2 diabetes from a large meta-analysis of GWASs contain 80 154 cases and 853 816 controls13. The data was downloaded from the DIAGRAM-Consortium (http://diagram-consortium.org/downloads.html). We collected GWAS summary-level data of 14 common types cancer from large-scale consortia: brain, oral, thyroid, esophageal, breast, lung, gastric, pancreatic, colorectal, prostate, ovarian, endometrial, basal cell carcinoma, and multiple myeloma13–22. The details of each cancer outcome are presented in Supplementary Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455).

Replication with FinnGen study and meta-analysis

We performed the replication analyses of finding from the ‘Discovery’ results by using summary genetic cancer outcome data from the FinnGen consortium (R9) (https://www.finngen.fi/en)23. The FinnGen research is a large-scale project including genotype and clinical data with registries in up to 377 277 participants23. The number of individuals included in replication analysis ranged from 133 164 to 306 119 and is shown in Supplementary Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). Moreover, we performed meta-analysis to pool the MR findings from the discovery and replication analyses.

Statistical analyses

To reveal the causal effects of GLP1R agonist with 14 cancers, we performed MR analysis utilizing the ‘TwoSampleMR’ R package (version 0.5.8). The associations between cis-eQTLs and the outcomes were calculated odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding CIs by applying the random-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method. Positive control analysis was conducted to validate the genetic instruments for GLP1R. Since GLP1R agonists are already approved by the FDA for control blood glucose and weight, we thus verified the association of genetic instruments from eQTLs with type 2 diabetes as positive control study. Moreover, the MR-PRESSO was used to detect outlier genetic variants. In addition, we performed the MR-Egger intercept test to evaluate the horizontal pleiotropy24, and Cochrane’s Q value was performed to assess the heterogeneity in IVW estimators, and P<0.05 indicates the evidence of heterogeneity.

For the meta-analysis, we used estimated ORs and 95% CI. I 2 was used to evaluate heterogeneity across included studies, and if I 2>50%, it is considered significant heterogeneity. To decrease the influence of heterogeneity on the accuracy, all the analyses are conducted using random effect model. Probability values of<0.05 were considered statistic significantly. All the analysis were done with R software (V4.3.0).

Systematic review clinical drug trials on GLP1R agonist

We systematically retrieved PubMed, Embase, and The Cochrane Library for all related studies to 23 December 2023. The retrieve strategies were a combination of Mesh Terms and free words, and the full search strategies are provided in the supplementary Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). The reference lists of relevant literatures and reviews were also screened. Trails were retained if they were RCTs reporting the association with any cancer or cancer events followed GLP1RA treatment. We excluded studies included patient under 18 years, and studies that were limited to treatment with GLP1A alone. Non-English literature and literature where the full text cannot be found are also excluded. Two reviewers (Y.M.S. and Y.J.L.) independently screened titles and abstracts, and the disagreements were resolved through consensus. The following items were extracted from trails that conform to the inclusion criteria: the first author, country, years, study design, condition of patients, sample size, number of cases, cancer events, and follow-up period.

Results

Genetic instruments selection

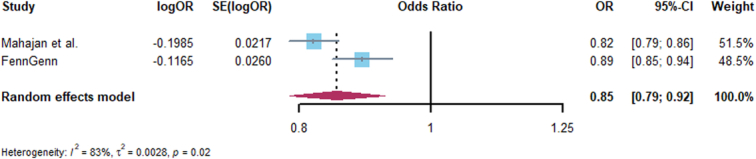

A total of 22 significant cis-eQTL SNPs were selected from eQTLGen as genetic instrument for drug target gene GLP1R. The F statistic of all instrument variants is over 47, which indicates no bias caused by weak instrument in our study (Supplementary Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). In addition, the result of positive control proved that GLP1RA significantly decreased the risk of type 2 diabetes [OR (95%)=0.82 [0.79–0.86), P<0.001] and similar with replication analyses of FinnGen consortium [OR (95%)=0.89 (0.85–0.94), P<0.001], which was also consistent with meta-analysis (Fig. 2), further ensuring the effectiveness of identified genetic instruments.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of associations of GLP1RA and Type 2 diabetes across Mahajan et al. and FinnGen.

Discovery MR analysis on GLP1RA with cancers

The results from ‘Discovery’ MR analysis found an obvious protective effect on some cancers with the higher expression of GLP1R gene in blood with the IVW method as the mainly causal results, including oral cancer [OR (95%)=0.11 (0.07–0.15), P<0.001], multiple myeloma [OR (95%)=0.32 (0.21–0.48), P<0.001], breast cancer [OR (95%)=0.92 (0.88–0.96), P<0.001], and basal cell carcinoma [OR (95%)=0.92 (0.85–0.99), P=0.029]. However, the IVW-MR analysis also showed suggestive evidence that with the increased expression of GLP1R gene, an increased risk of prostate cancer [OR (95%)=1.09 (1.05–1.14), P<0.001], colorectal cancer [OR (95%)=1.12 (1.07–1.18), P<0.001], endometrial cancer [OR (95%)=1.15 (1.03–1.28), P=0.001], esophageal cancer [OR (95%)=1.48 (1.19–1.85), P<0.001], and gastric cancer [OR (95%)=1.74 (1.54–1.97), P<0.001]. In addition, there was no supporting evidence to verify the association of GLP1R expression with pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer and thyroid cancer (Supplementary Table 5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). The Cochrane Q statistics and MR-Egger intercept test proved that there were no statistical heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy in IVW-MR (Supplementary Table 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455, 7, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455).

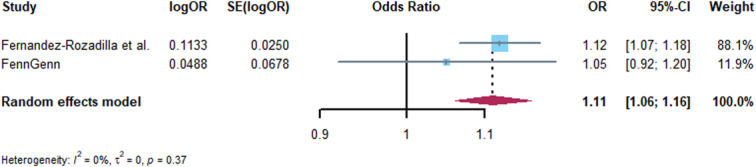

Replication with FinnGen study and meta-analysis

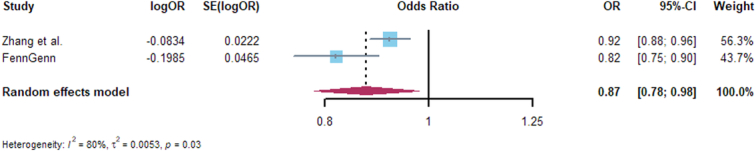

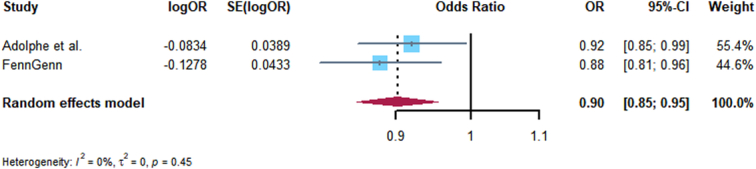

Replication analyses were performed for GLP1R with 14 kinds cancer, and only the associations of GLP1R expression with breast cancer, basal cell carcinoma, thyroid cancer, and endometrial cancer were consistent with Discovery analysis, the MR, heterogeneity, and horizontal pleiotropy results are presented in Supplementary Tables 8–10 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). Furthermore, we conducted meta-analysis of Discovery and Replication analyses, the consistent evidence of association with Discovery analysis including: breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma, colorectal, thyroid, lung, and ovarian cancer. The expression of GLP1R significantly decreased the risk of breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma (Figs 3, 4), but with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (Fig. 5), and no associated with thyroid, lung, and ovarian cancer (Supplementary Figs 1–3, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C456). Other meta-analysis results are shown in Supplementary Figs 4–11, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C456.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of associations of GLP1RA and basal cell carcinoma risk across Adolphe et al. and FinnGen.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of associations of GLP1RA and breast cancer risk across Zhang et al. and FinnGen.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of associations of GLP1RA and colorectal cancer risk across Fernandez-Rozadilla et al. and FinnGen.

Review of RCTs on GLP1R agonists

A total of 36 123 potentially relevant studies were identified from our database and citation searches. The titles and abstracts of 7248 studies were screened, and 101 studies were scanned for full text. Finally, the remaining 80 RCTs were included in our review. The PRISMA flowchart shows the literature screening process and reasons for exclusion in our report (Supplementary Fig. 12, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C456). The trails were mainly conducted in America, China, Korea, Japan, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, France, and UK. Detailed characteristics of the included RCTs are shown in Supplementary Table 11 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). In summary, the majority of RCTs focused on the therapeutic effect of GLP1R agonist on type 2 diabetes, and a few studied on obesity, heart failure, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, type 1 diabetes, and carotid plaque. These RCTs included only adults and the number of participants ranged from 44 to 17 604. Most of the studies had shorter patient follow-up periods, with only 10 RCTs exceeding 2 years Supplementary Table 11 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C455). The incidence of different kinds of cancer among the included studies was low, with a total of 65 328 participants in the GLP1R treatment group, of which 1559 patients developing cancer. Among the treated group, the larger number of cancers diagnosed were pancreatic cancer (n=63), breast cancer (n=48), lung cancer (n=37), colorectal cancer (n=36), and prostate cancer (n=34), and the detailed cancer data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The details of various of cancer from systematic review.

| Subject | GLP1R agonists (n) | Placebo (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall participants | 65 328 | 56 016 |

| Cancers | 1559 | 1498 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 63 | 53 |

| Breast cancer | 48 | 27 |

| Lung cancer | 37 | 39 |

| Colorectal cancer | 36 | 31 |

| Prostate cancer | 34 | 53 |

| Thyroid cancer | 29 | 17 |

| Kidney cancer | 19 | 11 |

| Bladder cancer | 17 | 14 |

| Melanoma | 14 | 6 |

| Liver cancer | 14 | 9 |

| Gastric cancer | 13 | 16 |

| Lymphoma | 11 | 6 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 9 | 3 |

| Oral cancer | 7 | 6 |

| Leukemias | 6 | 14 |

| Cervical cancer | 6 | 2 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 5 | 3 |

| Ovarian cancer | 3 | 2 |

| Bone cancer | 2 | 5 |

| Endometrial cancer | 1 | 0 |

| Uterine cancer | 1 | 0 |

| Multiple myeloma | 0 | 1 |

| Brain cancer | 0 | 2 |

| Head and neck cancer | 0 | 3 |

| Esophagus cancer | 0 | 1 |

Discussion

Obesity affects ~800 million people worldwide, and is associated with increased rates of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, sleep disorders, cardiovascular disease, and premature death, for which raises concerns about weight management25. The FDA approved semaglutide for the management of obesity, which attracted attention on its safety for long-term use1. We comprehensively investigated the genetic and clinical trials to explore the causal association of using GLP1R agonist with cancers. We found the expression of GLP1R gene in blood with the decreased risk of breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma, but with a lower increased risk of colorectal cancer, which were consistent in both drug-target MR and meta-analysis. In addition, we found that the use of GLP1R agonists did not increase the risk of lung, thyroid, and ovarian cancers. Although a few clinical trials reported occurrence of breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and thyroid cancer, etc. subsequent to use of the GLP1R agonist, these findings need to be verified in larger multicenter randomized controlled trials, especially with long follow-up periods.

Drug target MR can be used to explore new therapeutic targets for diseases as well as complications of drugs, and have been found to be effective in numbers conditions, such as coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and cancers26–29. Previous studies have focused on the effectiveness of GLP1R agonists treatment on type 2 diabetes and obesity, and recently demonstrated benefits for cardiovascular disease30,31. However, few attentions have been paid to the association of GIP1R agonists with cancers. In our ‘Discovery’ MR analysis verified the inverse associations between GLP1R agonists and breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma. GLP-1R is expressed in human breast cancer, and GLP-1 can attenuate breast cancer cell proliferation by activating GLP-1R and subsequently inhibiting the activation of NF-kB32. In addition, GLP-1R can increase the level of cAMP, activate the downstream target CREB, and effectively inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells33. Moreover, our findings replicate consistently when pooled with the FinnGen study. However, a randomized controlled trial with a sample size of 14 752 people, who subcutaneous injections with GLP1R agonists showed no decreased occurrence in breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma after 3.2 years of follow-up34. Accordingly, the protective role of GLP1R agonists in development of breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma need further assessment in future clinical studies.

We also found indicated evidence for an association of genetically-proxied GLP1R with increased risk of colorectal cancer. GLP1R is expressed in normal colon tissue and has recently been found to have elevated levels of DNA hypermethylation in colorectal cancer35,36. In addition, GLP1R agonists could enhance Wnt signaling, its activation plays a crucial role in colorectal cancer development, for which using of GLP1R agonists may have high risk of colorectal cancer37. However, a recent retrospective study reported that GLP1R agonists were associated with decreased the risk of colorectal cancer38. Although its large sample size, the potential biases inherent in observational studies such as unmeasured or uncontrolled confounders and reverse causality, which need warrant further validation of the conclusion. it is worth noting that the result of meta-analysis was consistent with our ‘Discovery’ analysis, which guarantees the reliability of our conclusions. Finally, there was suggestive evidence to support GLP1R agonists were not associated with the risk of lung, thyroid, and ovarian cancers, which were consistent with clinical trials39,40.

There are several strengths as follows. Firstly, we explored the associations of GLP1R agonists with 14 common types cancer in large GWAS summary-level data and validated the findings in FinnGen biobank. Secondly, we performed meta-analysis of ‘Discovery’ and ‘Replication’ analyses, increasing statistical capacity and the breadth of analyses. Thirdly, the systematic review of RCTs on GLP1R agonists were performed to stabilize the evidence. Limitations also need to be noticed when interpreting our results. Firstly, the drug target MR findings reflect the effect of long-period genetically-proxied GLP1R agonists on cancer risk may not be consistent with results in clinical trials over a relatively limited period of time. Secondly, we only found consistent results for basal cell carcinoma, breast, colorectal, lung, thyroid, and ovarian cancer in the pooled ‘Discovery’ and ‘Replication’ analyses, but inconsistent finding for multiple myeloma, brain, oral, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and endometrial cancer. Much larger sample size of GWAS and RCTs with long follow-up period are needed in the future. Thirdly, our analyses were conducted with participants of European ancestry, so the universality of our findings to non-European populations is unclear. Fourth, we did not explore the association of some rarer cancers and the subtypes of selected cancers. Finally, our study was limited to cancer risk but not progression, future studies should focus on the potential effect of GLP1R agonists in cancer treatment and prognosis.

In summary, using multiple analytic approaches our study found that genetically-proxied GLP1R agonists was associated with protective effect on breast cancer and basal cell carcinoma, but with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. In addition, we found that GLP1R agonists did not increase the risk of lung, thyroid, or ovarian cancers. All the findings of our analysis need to be evaluated in RCTs with long follow-up duration.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

All the studies included in our analysis have been approved by the relevant institutional review committee and obtained the informed consent from participants.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 8197081674 to SR L, 82102803 and 82272849 to GT D). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, collection and analysis of data, interpretation of results, and decision to publish.

Author contribution

S.R.L., G.T.D., and F.R.Z.: led on the conception and design of the study; Y.M.S., Y.J.L., and Y.T.D.: searched, extracted, and critically appraised the studies included in the analysis; Y.M.S.: planned and performed the statistical analyses; Y.M.S.: wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and the final draft of the paper. All other authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: not applicable.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: not applicable.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): not applicable.

Guarantor

Shaorong Lei, Guangtong Deng, and Furong Zeng.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Provenance and peer review

Not applicable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted using the published article, eQTLGen Consortium (https://www.eqtlgen.org/), and FinnGen consortium for sharing the summary-level data on gallstones. The authors would also like to acknowledge the investigators of these consortia and studies for generating the data used for this analysis.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 3 May 2024

Contributor Information

Yuming Sun, Email: 962881298@qq.com.

Yongjia Liu, Email: liuyongjia56@sina.com.

Yating Dian, Email: dianyating@outlook.com.

Furong Zeng, Email: zengflorachn@hotmail.com.

Guangtong Deng, Email: dengguangtong@outlook.com.

Shaorong Lei, Email: leishaorong@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Aggarwal R, Vaduganathan M, Chiu N, et al. Potential implications of the FDA approval of semaglutide for overweight and obese adults in the United States. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2021;68:97–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersen A, Lund A, Knop FK, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:390–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023;389:2221–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruder K. As semaglutide’s popularity soars, rare but serious adverse effects are emerging. JAMA 2023;330:2140–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elashoff M, Matveyenko AV, Gier B, et al. Pancreatitis, pancreatic, and thyroid cancer with glucagon-like peptide-1–based therapies. Gastroenterology 2011;141:150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMinn PC. Enterovirus vaccines for an emerging cause of brain-stem encephalitis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:792–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 2021;326:1614–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cupido AJ, Reeskamp LF, Hingorani AD, et al. Joint genetic inhibition of PCSK9 and CETP and the association with coronary artery disease: a factorial Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fang S, Yarmolinsky J, Gill D, et al. Association between genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition and prostate cancer risk: a Mendelian randomisation study. PLoS Med 2023;20:e1003988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gill D, Burgess S. The evolution of Mendelian randomization for investigating drug effects. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Storm CS, Kia DA, Almramhi MM, et al. Finding genetically-supported drug targets for Parkinson’s disease using Mendelian randomization of the druggable genome. Nat Commun 2021;12:7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Võsa U, Claringbould A, Westra HJ, et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat Genet 2021;53:1300–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mahajan A, Spracklen CN, Zhang W, et al. Multi-ancestry genetic study of type 2 diabetes highlights the power of diverse populations for discovery and translation. Nat Genet 2022;54:560–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adolphe C, Xue A, Fard AT, et al. Genetic and functional interaction network analysis reveals global enrichment of regulatory T cell genes influencing basal cell carcinoma susceptibility. Genome Med 2021;13:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Timofeeva M, Chen Z, et al. Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and east Asian ancestries. Nat Genet 2023;55:89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang L, Zheng Z, Fang H, et al. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat Genet 2021;53:1616–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKay JD, Hung RJ, Han Y, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes. Nat Genet 2017;49:1126–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O’Mara TA, Glubb DM, Amant F, et al. Identification of nine new susceptibility loci for endometrial cancer. Nat Commun 2018;9:3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phelan CM, Kuchenbaecker KB, Tyrer JP, et al. Identification of 12 new susceptibility loci for different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 2017;49:680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet 2021;53:1415–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang H, Ahearn TU, Lecarpentier J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 32 novel breast cancer susceptibility loci from overall and subtype-specific analyses. Nat Genet 2020;52:572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang A, Shen J, Rodriguez AA, et al. Characterizing prostate cancer risk through multi-ancestry genome-wide discovery of 187 novel risk variants. Nat Genet 2023;55:2065–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 2023;613:508–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song Y, Zhu C, Shi B, et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from two large prospective cohorts in Europe and East Asia and Mendelian randomization. EClinicalMedicine 2023;64:102236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elmaleh-Sachs A, Schwartz JL, Bramante CT, et al. Obesity management in adults. JAMA 2023;330:2000–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. The Lancet 2012;379:1214–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chong M, Sjaarda J, Pigeyre M, et al. Novel drug targets for ischemic stroke identified through Mendelian randomization analysis of the blood proteome. Circulation 2019;140:819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Henry A, Gordillo-Marañón M, Finan C, et al. Therapeutic targets for heart failure identified using proteomics and Mendelian randomization. Circulation 2022;145:1205–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yarmolinsky J, Díez-Obrero V, Richardson TG, et al. Genetically proxied therapeutic inhibition of antihypertensive drug targets and risk of common cancers: a Mendelian randomization analysis. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012;344:d7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ussher JR, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: cardiovascular benefits and mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023;20:463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwaya C, Nomiyama T, Komatsu S, et al. Exendin-4, a glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonist, attenuates breast cancer growth by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Endocrinology 2017;158:4218–4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ligumsky H, Wolf I, Israeli S, et al. The peptide-hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 activates cAMP and inhibits growth of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;132:449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1228–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Campos RV, Lee YC, Drucker DJ. Divergent tissue-specific and developmental expression of receptors for glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 in the mouse. Endocrinology 1994;134:2156–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mori Y, Olaru AV, Cheng Y, et al. Novel candidate colorectal cancer biomarkers identified by methylation microarray-based scanning. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011;18:465–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun Y, Fan L, Meng J, et al. Should GLP-1 receptor agonists be used with caution in high risk population for colorectal cancer? Med Hypotheses 2014;82:255–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang L, Wang W, Kaelber DC, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and colorectal cancer risk in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes, with and without overweight/obesity. JAMA Oncol 2024;10:256–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Espinosa De Ycaza AE, Brito JP, McCoy R, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer: a narrative review. Thyroid 2024;34:403–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rouette J, Yin H, Yu OHY, et al. Incretin-based drugs and risk of lung cancer among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2020;37:868–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.