Abstract

Introduction

Orthorexia nervosa (ON), characterized by a pathological preoccupation with “extreme dietary purity,” is increasingly observed as a mental health condition among young adults and the general population. However, its diagnosis is not formally recognized and has remained contentious.

Objective

In this systematic review, we attempt to overview previous reviews on ON, focusing on the methodological and conceptual issues with ON. This would serve both as a summary and a way to highlight gaps in earlier research.

Methods

This systematic review took reference from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines, and using combinations of the search terms (“orthorexia” OR “orthorexia nervosa” OR “ON”) AND (“review” OR “systematic review” OR “meta-analysis”), a literature search was performed on EMBASE, Medline and PsycINFO databases from inception up to October 31, 2023. Articles were included if (1) they were written or translated into English and (2) contained information pertaining to the diagnostic stability or validity of ON, or instruments used to measure ON symptoms and behaviors. Only review articles with a systematic literature search approach were included.

Results

A total of 22 reviews were qualitatively reviewed. Several studies have reported variable prevalence of ON and highlighted the lack of thoroughly evaluated measures of ON with clear psychometric properties, with no reliable estimates. ORTO-15 and its variations such as ORTO-11, ORTO-12 are popularly used, although their use is discouraged. Existing instruments lack specificity for pathology and several disagreements on the conceptualization and hence diagnostic criteria of ON exist.

Discussion

Previous reviews have consistently highlighted the highly variable (and contradictory) prevalence rates with different instruments to measure ON, lack of stable factor structure and psychometrics across ON measures, paucity of data on ON in clinical samples, and a need for a modern re-conceptualization of ON. The diagnosis of ON is challenging as it likely spans a spectrum from “normal” to “abnormal,” and “functional” to “dysfunctional.” “Non-pathological” orthorexia is not related to psychopathological constructs in the same way that ON is.

Keywords: Orthorexia, Orthorexia nervosa, Systematic review, Overview of reviews

Plain Language Summary

Orthorexia nervosa, or “ON” for short, is when someone becomes too focused on eating only foods they see as “pure” or “clean.” While eating healthily is a good thing, orthorexia nervosa takes it to the extreme and can harm a person’s overall well-being. Although more experts are starting to notice and talk about this issue, it is still not officially labelled as a mental health problem. To better understand ON, we systematically reviewed past reviews on the topic to see where they agreed and where they had different views. Our research showed that there is no clear agreement on how common ON is. The tools we currently use to identify if someone has ON are not always trustworthy. There is also some confusion about what exactly ON is and how it is distinct as compared to other similar conditions. This is concerning because we need to accurately identify and help those struggling with ON. This overview of reviews highlights the areas where we need to dig deeper and do more research to fully understand and address ON.

Introduction

Orthorexia is derived from the term meaning “proper appetite.” However, when combined as “orthorexia nervosa,” with “nervosa” indicating a disorder, it refers to an unhealthy obsession with consuming only foods perceived as healthy. This condition is characterized by ritualistic eating behaviors, a strict dietary regimen, and a stringent avoidance of foods considered unhealthy or lacking in nutritional value [1]. In addition to malnourishment, such “health fanatic” eating habits can become noxious to social relationships, causing individuals to develop an altered psychophysical state and experience a deterioration in quality of life [2]. While physical exercise and a balanced diet are cornerstones for achieving optimal health, an obsessive pursuit of this ideal can become detrimental and distressing for the individual [3, 4].

This nascent field of research has culminated in the consensus among clinicians that orthorexia nervosa (ON) is the fixation, obsession, and preoccupation with “extreme dietary purity” [5]. However, ON continues to lack a working definition in the sphere of eating disorders (EDs) and is not a recognized disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), despite its purported prevalence in contemporary society [6]. ON has been framed within the context of “healthiest” societies, albeit the divide between “non-pathological” and “disordered” eating behaviors is increasingly blurred.

Although ON has been increasingly recognized in diverse populations including young persons and working adults, and multiple systematic reviews on the topic exist [7–9], several contentions still exist with regard to the methodological and conceptual issues with ON [10]. As a logical next step, in this review, we aimed to provide an overview of published systematic reviews in this space, allowing the findings of previous reviews to be compared and discussed, in relation to the descriptive psychopathology of orthorexia and the measurement and distinctness of orthorexia symptoms and behaviors. This would serve both as a summary and a way to highlight gaps in earlier research.

Aims of the Study

The aims of the present review were (1) to overview previous reviews on literature pertaining to ON, (2) to examine what other psychological conditions and risk factors tend to co-occur with ON, and (3) to discuss the implications for defining ON as a distinct construct.

Methods

This review took reference from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines [11] and a systematic search strategy was developed, in consultation with a medical information specialist. Using combinations of the search terms (“orthorexia” OR “orthorexia nervosa” OR “ON”) AND (“review” OR “systematic review” OR “meta-analysis”), a literature search was performed on EMBASE, Medline, and PsycINFO databases from inception up to October 31, 2023. The full search strategy is displayed in online supplementary Table S1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000536379). Articles were selected according to the information in the abstract. Articles were included if they were (1) published in or had an English language translation and (2) contained information pertaining to the psychopathology of ON, diagnostic stability or validity of ON or instruments used to measure ON symptoms and behaviors. Only review articles with a systematic literature search approach were included. Narrative reviews, selected reviews, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts/proceedings, case series, and reports were excluded. Additional relevant articles were sought via a manual bibliography search.

Results

Literature Retrieval

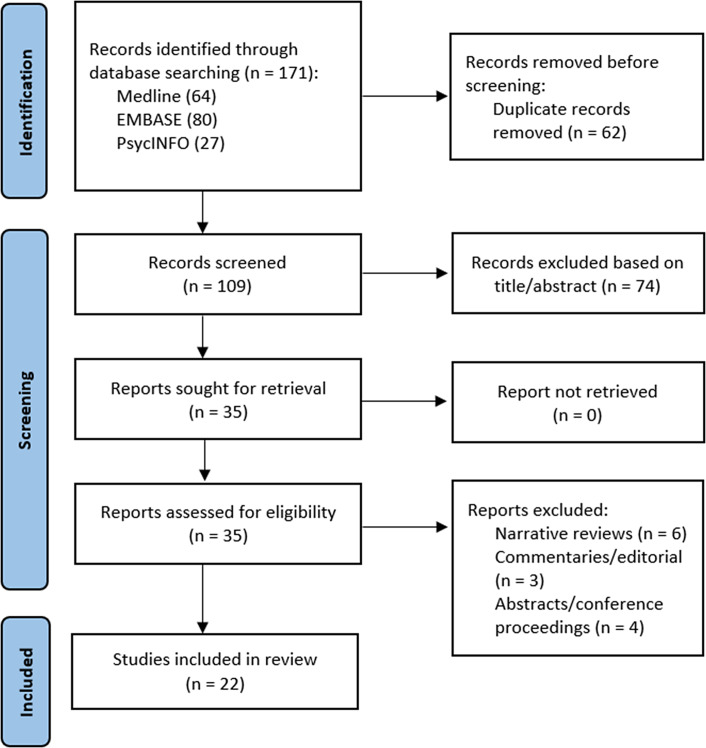

The initial search identified a total of 171 records, of which 109 remained after removal of duplicates. The titles and abstracts of these articles were screened, and a total of 35 articles were included in the full-text review. Of these, 13 narrative reviews, commentaries, and conference abstracts were excluded, leaving 22 articles [7–9, 12–30] for inclusion (Fig. 1). The key study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the studies identified during the literature search and abstraction process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews on ON with or without meta-analysis

| Author, year | Study objective | Included studies | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atchison et al. [7] 2022 | Review literature regarding ON and ED symptoms | 42 articles (containing original, empirical data using both a measure of disordered eating (e.g., EAT, EDI) or weight-related eating behavior (e.g., dieting, restraint, emotional eating) and a measure of ON other than the ORTO/BOT (e.g., TOS, DOS, EHQ) | - ON behavior, motivated by thinness and weight control, involves characteristic restraint and specific restrictive eating, despite individuals scoring high on ON measures not displaying notably different body image concerns or problematic eating habits compared to the general population |

| - The absence of a link with dysregulated eating indicates that ON’s restrictive eating might not be as severe or calorie-focused as in other EDs, thereby differentiating ON from other EDs | |||

| Costa et al. [8] 2017 | Review available literature on the phenomenon of ON | 15 articles (9 quantitative studies, 5 literature reviews, 1 qualitative study, and 1 case study) | - The ORTO-15 questionnaire, though partially validated, is the main recognized tool for assessing ON symptoms |

| - Current research indicates that ON shows symptom overlap with OCD and AN, and to a lesser extent, BN | |||

| Gkiouleka et al. [9] 2022 | Review available literature on ON, in the context of adolescents and young adults | Not specified | - ON prevalence varies widely among children and young adults across countries and populations, but studies concur that these age groups are at risk of ON |

| - ON should be recognized as an ED, which is also related to obsessive-compulsive behaviors, not specifically as OCD | |||

| Grammatikopoulou et al. [12] 2021 | Review prevalence and symptomatology of ON in patients with diabetes | 6 articles (5 cross-sectional and 1 case-control study) | - Similar to studies conducted in the general population, the ORTO-15 questionnaire or its adaptations were predominantly used, with prevalence rates ranging from 1.5% to 81.3% |

| - Limited research suggests patients with diabetes may display ON tendencies, but understanding regarding the origins, mechanisms, and traits of patients with concurrent diagnoses is still lacking | |||

| Hafstad et al. [13] 2023 | Review prevalence of ON in exercising/sports samples | 24 articles (24 cross-sectional studies) | - The overall prevalence of ON across all 24 studies was 55.3% (95% CI: 43.2–66.8), and majority of the studies used the ORTO-15 questionnaire |

| - Significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98.4%) was observed, and neither gender, sport type, nor sample size could account for this in the meta-regression | |||

| Håman et al. [14] 2015 | Review available empirical or theoretical literature on ON | 19 articles (14 cross-sectional studies, 3 case reports, 1 grounded theory study, and 1 theoretical study) | - Orthorexia has been depicted as an individual issue; future studies should employ empirical-holistic and interpretive qualitative methods, focusing on a social health perspective like healthism |

| - The role of sports and exercise concerning orthorexia has not been well-studied | |||

| Huynh et al. [15] 2023 | Review available literature on ON and OC symptoms | 40 articles (40 cross-sectional studies) | - Studies that utilized older methods for evaluating ON showed varying correlations with OC symptoms, as opposed to newer studies employing more recent tools (since 2018) that consistently revealed stronger, more significant relationships between ON and OC |

| - OC symptoms in ON have likely been underemphasized; further research with validated tools warranted | |||

| Mathieu et al. [16] 2023 | Review literature on the associations between vegetarianism, body mass index, and EDs/ON | 46 articles (43 cross-sectional studies, 2 case-control studies, and 1 population-based telephone survey) | - Regardless of the evaluation method utilized, research typically indicates a higher likelihood of orthorexic tendencies among vegetarians and vegans compared to omnivores |

| - Vegetarians and vegans who base their dietary choices on health concerns exhibit a higher risk of developing ON compared to those guided by ethical motivations; the motivations behind food choices vary between different forms of orthorexia | |||

| McComb et al. [17] 2019 | Review literature on psychosocial risk factors and correlates associated with ON | 54 articles (54 correlational studies) | - The prevalence rates of ON are wide ranging and are likely artificially elevated due to the suboptimal psychometric qualities of the ORTO-15, the most frequently utilized assessment tool for identifying ON |

| - A positive association exists between ON and various factors: perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive traits, psychopathology, disordered eating, past ED history, dieting, poor body image, and a drive for thinness; mixed findings are noted concerning ON and age, socioeconomic status, body mass index, working in a health-related field, exercise habits, vegetarianism/veganism, body dissatisfaction, and the use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs; gender and self-esteem generally show no correlation with ON | |||

| McLean et al. [18] 2022 | Review literature on vegetarianism, veganism, and disordered eating (including ON) | 17 articles (17 cross-sectional studies) | - Most studies reported higher levels of ON behaviors among vegetarians and vegans |

| - Use of ED measures in vegetarians and vegans shows poor psychometric fit among all scales | |||

| Nucci et al. [19] 2022 | Review literature on disordered eating (including ON) among cancer patients | 2 articles (1 case control and 1 case report) | - ON can lead to weight loss, malnutrition, and interpersonal impairments among cancer patients |

| Opitz et al., 2020 [20] | Review literature on the psychometric properties of ON assessment scales | 68 articles (instruments include Body Image Screening Questionnaire (BISQ), Burda Orthorexia Risk Assessment (B-ORA), BOT, DOS, EHQ, Orthorexia Nervosa Scale (ONS), ORTO-15, Scale to Measure Orthorexia in Puerto Rican Men and Women, TOS) | - Existing ON measures, including BOT and ORTO-15, show questionable psychometric properties and their use should be discouraged; some tools, such as DOS and TOS, challenge initial diagnostic criteria for ON, other instruments like EHQ-R, ONS, and B-ORA need additional evaluation |

| - Further research should also address the current inconsistencies in ON conceptualization, which are apparent in its measurement tools | |||

| Örge et al. [21] 2023 | Review literature on childhood trauma and development of EDs (including ON) | 21 articles (21 cross-sectional studies, only 2 specifically focusing on ON) | - Apart from two Turkish studies, no international literature on childhood maltreatment and ON |

| - In comparison, childhood maltreatment appears to be an important risk factor for development of EDs in adulthood | |||

| Paludo et al. [22] 2022 | Review literature reporting prevalence of risk for ON in athletes | 6 articles (6 cross-sectional studies) | - Utilizing the ORTO-15 and a cutoff of 40 points, there was no difference in ON scores between athletes and non-athletes, highlighting the need to address ON as a concern within the wider population |

| Pontillo et al. [23] 2022 | Reviewed literature on ON and its relationship with EDs and OCD | 10 articles (7 experimental studies, 1 observational, controlled study, 1 cross-sectional study, and 1 case report) | - ON should be recognized as a clinically significant condition, rather than merely a behavioral or lifestyle phenomenon |

| - The relationships between ON, EDs, and OCD remain muddled and future studies, especially longitudinal ones, are essential to discern whether ON develops before or after the onset of EDs, OCD, or both | |||

| Pruneti et al. [24] 2023 | Review literature on psychophysiology of OC spectrum disorders and ON | 8 articles (4 cross-sectional studies, 3 case-control studies, and 1 longitudinal observational study; none specifically pertaining to ON) | - Poor inhibition abilities in OCD, even amid low activation, and a disconnection between cognitive and psychophysiological activation is noted |

| - Diagnostic criteria often used to identify ON, such as obsessiveness and compulsions related to heightened somatic tension, appear to share pathognomonic characteristics with OCD, although no empirical study exists | |||

| Skella et al. [25] 2022 | Review literature on correlations between orthorexia and EDs in young adults and adolescents | 37 articles (37 cross-sectional studies) | - Adolescents with EDs had an increased risk of ON |

| - Available studies were all cross-sectional in nature and could not establish causation, moreover, many were of low quality | |||

| Strahler [26] 2019 | Review literature on sex differences in ON behaviors | 67 articles (67 cross-sectional studies) | - Majority of the research using the ORTO-15 (62% of the studies) and BOT (8.9% of the studies) showed equal levels of ON behaviors in both men and women |

| - Other studies have indicated higher subclinical ED-related symptoms in women, with a minor sex difference observed in results from the DOS. | |||

| Strahler et al. [27] 2021 | Review literature on ON and addictive exercise behaviors | 25 articles (25 cross-sectional studies) | - ON and exercise addiction have overlaps; orthorexic eating has a small correlation with exercise (21 studies, r = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.06–0.18) and moderate correlation with exercise addiction (7 studies, r = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.13–0.45) |

| - This correlation neither asserts ON and exercise addiction as entirely independent nor strongly comorbid disorders | |||

| Valente et al. [28] 2019 | Critically review tools used to assess ON | 70 articles (70 cross-sectional studies) | - Six diagnostic questionnaires have been constructed from 2000 to 2018 to assess ON: BOT, ORTO-15, EHQ, DOS, BOS, and TOS. The ORTO-15 test has been the most utilized, with several adaptations in multiple languages |

| - The inconsistency in prevalence rates is attributed to the varied diagnostic tools used; a contemporary re-conceptualization of ON is required | |||

| Varga et al. [29] 2013 | Review literature on ON prevalence, risk groups and risk factors | 11 articles (11 cross-sectional studies) | - Prevalence of ON was 6.9% in the general population and 35–57.8% for high-risk groups (including healthcare professionals, artists, etc.) |

| - Diagnostic criteria for ON remain unclear | |||

| Zagaria et al. [30] 2022 | Review the magnitude of association between ON, ED, and OCD symptoms | 36 articles (36 cross-sectional studies) | - ON symptoms show a moderate association with ED symptoms (r = 0.36) and a smaller association with OCD symptoms (r = 0.21) |

| - Although ON leans more toward the ED spectrum, the non-high strength of these associations indicates that ON might be a distinct ED |

AN, anorexia nervosa; BN, bulimia nervosa; BOS, Barcelona Orthorexia Scale; BOT, Bratman Orthorexia Test; DOS, Düsseldorfer Orthorexia Scale; EAT, eating attitudes test; EDI, eating disorder inventory; ED, eating disorder; EHQ, Eating Habits Questionnaire; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ON, orthorexia nervosa; TOS, Teruel Orthorexia Scale.

Psychometric Properties of Tools Used to Measure Dimensional ON Symptoms

ON is an emerging phenomenon with its diagnostic criteria, methods of classification, and psychopathological mechanisms subjected to ongoing debate and questioning. The following diagnostic criteria: (1) obsessional or pathological preoccupation with healthy nutrition; (2) emotional consequences (e.g., distress or anxiety) of non-adherence to self-imposed nutritional restrictions; (3) psychosocial impairments; and the ORTO-15 are commonly used to support the clinical diagnosis of ON [1] although few studies have been conducted in clinical populations, as highlighted by Skella et al. [25].

Accordingly, the heterogeneity of literature on ON and the subjectivity surrounding what constitutes “disordered eating” have attracted academic criticism on ON’s diagnostic parameters [10]. In addition, the lack of consensus on a criterial “gold standard” makes it difficult to gauge the appropriateness of presently available self-report measures and their true sensitivities and specificities [10]. Based on two reviews of the tools used to assess ON [20, 28], the ORTO-15 and the Orthorexia Self-Test, both developed by Bratman, were most frequently used in the psychometric evaluation of ON. Other commonly used tools include the German Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala (DOS) and the Eating Habits Questionnaire (EHQ). The validity of the ORTO-15, a 15-item self-reported measure, has been frequently called into question given the high percentage of false positives. This is likely due to strong overlaps between orthorexic and healthy behaviors, as well as low internal validity with large variance across items [20, 28]. The ORTO-15 also omits obsessive-compulsive behaviors that might confound the results obtained [15].

As highlighted in a review of psychosocial risk factors and correlates with ON by McComb and Mills [17], the prevalence rates of ON are wide ranging and are likely artificially elevated due to the suboptimal psychometric qualities of the ORTO-15, the most frequently utilized assessment tool for identifying ON. The broad range of ON prevalence reported can be partly attributed to the difficulty in differentiating between healthy eating and “pathological” ON.

Epidemiology of ON

Several studies have evaluated the prevalence of ON in specific populations. A recent systematic review by Grammatikopoulou et al. [12] aimed to determine the prevalence of ON in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). The authors found that the range of prevalence rates varied widely from 1.5% in type 2 DM adults evaluated using the Bratman Orthorexia Test (BOT) to 81.3% in type 1 DM children and adolescents evaluated using the ORTO-15 Questionnaire. The review by Gkiouleka et al. [9], which focused on adolescents and young adults, also found a wide range of prevalence across different populations and countries. In terms of athletic populations, the review by Paludo et al. [21] found there was no difference in ON scores between athletes and non-athletes, instead highlighting the need to address ON as a concern within the wider population.

It is apparent that owing to the lack of thoroughly evaluated measures of ON with clear psychometric properties, it is difficult to obtain valid and reliable estimates of its prevalence. Valente et al. [27] reviewed 70 cross-sectional studies and concluded in a recent review that there exists no reliable data regarding the prevalence or epidemiology of ON, although some groups appear to be more susceptible to the risk of ON than others. The inconsistency in prevalence rates is attributed to the varied diagnostic tools used, and a contemporary re-conceptualization of ON is required to advance the field [27].

Diagnostic Overlaps with Existing Psychiatric Disorders

Apart from the methodological shortcomings, ON’s diagnostic conundrum also implicates conceptual issues. This disordered pattern of eating shares several overlaps with various existing psychiatric disorders in terms of symptomatology, and the boundaries between existing psychiatric disorders can be difficult to delineate.

Overlaps with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

ON and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) patients share a degree of obsessive-compulsive tendencies such as intrusive thoughts about food and health at inappropriate times, a disproportionate concern over impurity, and ritualized patterns of eating [8, 9, 15, 23, 24, 30]. A recent 2023 review by Pruneti et al. [24] found that the diagnostic criteria often used to identify ON, such as obsessiveness and compulsions related to heightened somatic tension, appear to share pathognomonic characteristics with OCD, although no empirical study exists.

Zagaria et al. [30] performed a meta-analysis, searching for studies up to February 2021, which found ON to be distinct from OCD and more associated with EDs. The authors further contend that the non-high magnitude of the pooled correlations possibly suggests that ON is different from pre-existing EDs and OCD. Hence, ON could be treated as a stand-alone ED and be included as an emerging syndrome in the DSM classification.

In a newer review by Huynh et al. [15], which included studies up to April 2023, it was found that studies that utilized older methods for evaluating ON symptoms showed varying overlaps with OC symptoms; however, newer research employing more recent tools (since 2018) have consistently revealed stronger, more significant relationships between ON and OC. The review by Huynh et al. [15] builds on earlier findings and suggests an OC aspect of ON that was previously not given enough attention.

Overlaps with Other EDs

Whether ON should lie on the spectrum of existing EDs is yet another matter of scrutiny. Disordered eating and a past ED history have been positively associated with ON in a review by McComb and Mills [17]. Additionally, in a recent review by Atchison et al. [7], the authors reported that ON behavior is frequently related to both trait and disordered restrictive eating symptoms seen in AN, despite individuals scoring high on ON measures not displaying notably different body image concerns or problematic eating habits compared to the general population. However, the absence of a link with dysregulated eating indicates that ON’s restrictive eating might not be as severe or calorie-focused as in other EDs, thereby differentiating ON from other EDs [7].

Discussion

Based on a systematic review of existing reviews, it is clear that current instruments such as the widely used ORTO-15 are, at best, mediocre screening tools for ON, and there have been several disagreements on the conceptualization and hence diagnostic criteria of ON. The instruments used to evaluate the degree to which individuals display orthorexic behaviors have also suffered from issues of sensitivity and specificity [31]. A recent mixed-method examination has further suggested that the ORTO-15 is sensitive to diet changes but lacks specificity for pathology [32].

In response to the criticism of the ORTO-15, other newer measures have been explored as potential alternatives to support a clinical diagnosis of ON. When assessed with these newer tools, more consistent and significant relationships between ON and OC symptoms have been found, as compared to studies done prior to 2018 [15]. Preliminary studies have shown strong internal consistency of the EHQ, suggesting reliability [33]. Other scales such as the Test Orthorexia Nervosa (TON), Orthorexia Nervous Inventory (ONI) have also been developed. In particular, the newer Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) adopts a bidimensional test structure [34]; the ON scale measures distress and interference associated with healthy eating preoccupation while some of the thoughts and behaviors captured by items on the healthy orthorexia (HO) scale could be described as rigid. Some contend that HO can be seen as a protective behavior [35]. In fact, healthy orthorexia is positively correlated with positive affect and negatively correlated with psychopathology [35]. Recent exploratory factor analyses have also identified a two-dimensional structure in both the DOS and EHQ, which represent healthy orthorexia and ON [36, 37]. More studies are needed to create a more academically rigorous and universally accepted diagnostic tool given the limitations of existing tools (as summarized in Table 2). This would allow for the reliable diagnosis of ON and further assessment of other measures. At present, developers of newer measures like the EHQ, ONI, and TOS have not recommended using these measures clinically or suggested cut-scores for screening for psychopathology. None of the existing assessment tools can support clinical diagnoses because they have not been evaluated for this use.

Table 2.

Summary of current assessment tools for ON

| Assessment tools | Strengths and limitations |

|---|---|

| Bratman Orthorexia Test | • Low internal validity with large variance across items |

| • Creators of the scale did not follow standardized statistical procedures when creating it | |

| ORTO-15 and variations (e.g., ORTO-11) | • Unreliable and lacks validity |

| • Has been translated into many languages | |

| • Not specific for disordered eating | |

| • Initial pool of items was not the subject of any factor analysis procedure | |

| • ORTO-15 was developed prior to the establishing typical characteristics of ON | |

| ORTO-R | • More precise measurement than ORTO-15 |

| Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala | • Preliminary data indicate internal consistency |

| • Has been validated in English and French | |

| • May not be able to differentiate anorexia and orthorexia | |

| Eating Habits Questionnaire | • Preliminary data indicate strong internal consistency |

| • Factor structure is rather variable across studies | |

| Authorized Bratman Orthorexia Self-Test | • Reliable and valid instrument to assess ON risk, as indicated by its face, structural, and convergent validity results |

| • More research required to verify the results | |

| Barcelona Orthorexia Scale | • In development, aims to address the psychological features of orthorexia |

| Motivation for Healthy Behaviors in Orthorexia Nervosa | • Has not been validated |

| Orthorexia Nervosa Inventory | • Good internal consistency and reliability |

| • First ON measure to include items assessing physical impairments | |

| Test of Orthorexia Nervosa | • Scale and subscales showed good psychometric properties, stability, reliability, and construct validity, although ORTO-15 was used for convergent validity |

| • May still indicate non-pathological orthorexic tendencies | |

| Teruel Orthorexia Scale | • Encompasses the differentiable aspects of orthorexia: healthy orthorexia and ON |

| • Satisfactory psychometric properties |

In reviewing the overlaps between ON and other existing psychiatric disorders, the symptomatology of ON appears to share similarities with various disorders, including OCD and other EDs. However, the ideas in ON appear to be more ego-syntonic (and less intrusive) compared to the ego-dystonic thoughts experienced by OCD sufferers [38]. There is also a difference between obsessions and over-valued ideas, which are maintained with “less delusional intensity,” as highlighted in the earlier versions of the DSM [39]. Over-valued ideas are not always distressing, and so do not negatively reinforce behaviors that help avoid, counteract, or neutralize them [39, 40]. Some argue that the aspect of ON involving over-valued ideas about health may intersect with “healthy orthorexia.” This is because over-valued ideas are not inherently pathological; they only become symptoms of psychopathology when they become intrusive, difficult to control in a distressing manner, or when acting upon them results in danger or distress. A similarity between ON and OCD is the idiosyncratic subjectivity of the “purity” associated with chosen foods. From our past clinical experience with individuals with ON behaviors, it seems that this “extreme dietary purity” may not always align with what is typically considered as healthy. Patients may also be fixated on the “health-giving properties” of a particular type of food to the exclusion of others.

Compared to other EDs, the correlation between ON and measures of ED symptoms could easily be inflated by shared behaviors or overlapping item content, especially when it comes to restrained eating or impairment caused by a narrow diet or inadequate calorie intake [25, 41]. Moreover, heterogeneity in reported correlations between ON and EDs may be partially attributed to the utilization of ON measures with unreliable psychometric properties. The same criticism has been raised about studies suggesting a relationship between vegetarianism and disordered eating [16, 18, 42–44]. The key difference that has been proposed between ON and EDs is that the over-valued idea is centred on health rather than weight, but measures of ON symptoms are not designed to distinguish between these over-valued ideas. A key feature of ON is restrictive eating, driven by ideas of health and/or purity. This resembles the restrictive eating seen in AN, albeit likely influenced by the modern diet culture and erroneous emphasis on “clean” or “pure” foods. However, in EDs, issues of control (particularly feelings of incompetence and fear of losing control) are thought to be central and they contribute to, maintain, and perpetuate ED symptoms [7, 19, 20, 26, 45].

However, the differences that have been found between ON and anorexia nervosa (AN) in terms of epidemiology are potentially inaccurate. Although sex prevalence in ON is more equal than in AN [26], which has a higher prevalence in females, AN could be underdiagnosed in males due to stigma and female-oriented diagnostic criteria. Though onset tends to be in young adults for ON, and earlier for AN in childhood and adolescence, this could be a sampling artefact, as ON has been researched mostly in young adult populations [9].

Apart from OCD and EDs, the symptoms and features of ON may also bear likeness to illness anxiety disorders, and ON may be an epiphenomenon of a primary mental disorder. Health anxiety is known to be associated with food and diet preoccupations [46]. Health anxiety may also lead to drastic and problematic changes in one’s eating and lifestyle behaviors [47]. Health anxiety could potentially exacerbate symptoms and be the underlying cause of ON; however, health anxiety is also poorly defined in the literature [48]. This begets the question of whether ON is an “abnormal” social phenomenon, a symptom of certain underlying psychiatric conditions, or a distinct mental illness?

Although it is apparent that ON is quite different from OCD and differs slightly from existing EDs, do clinical descriptions of ON suggest that it is a sufficiently distinct clinical diagnosis or syndrome, to prevent unnecessary expansion of diagnostic classifications? There is no easy answer. Based on the Feighner criteria [49], in terms of clinical features or symptomatology, ON is characterized by an obsession with healthy eating and avoidance of foods perceived as unhealthy. This goes beyond the pursuit of a healthy diet and delves into an obsession that can adversely affect an individual’s quality of life. In terms of laboratory tests, as of now, there are no specific laboratory tests that diagnose ON. More importantly, most of the reviewed literature relies on the ORTO-15, an instrument that is considered unreliable and lacks validity [18, 20]. In terms of delineation from other disorders, ON can be differentiated from other EDs like anorexia or bulimia based on its unique focus on the quality of food rather than quantity. However, individuals with ON have symptoms and concerns reminiscent of those with EDs. Both EDs and ON could be variants of a more fundamental disorder with over-valued ideas (rather than obsessions) and a need for control as its core psychopathology. It is apparent that more qualitative data and insights are required to establish ON as a distinct diagnosis and clinical entity, and distinguishing ON from general health consciousness can be challenging. When attempting to identifying a course over time, although longitudinal studies are lacking, ON features have been found to be stable over 6 months [50]. In terms of the heritability of ON, it is not well-established. However, like other EDs, a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors probably contributes to its onset [51].

It is possible that the mental health field can pivot to a dimensional model of psychopathology. The empirical evidence for such a paradigm shift is compelling and there is growing recognition that some dimensions of disordered behaviors are transdiagnostic [52, 53]. Individuals with mental health disorders frequently fulfil the diagnostic criteria of multiple disorders [54]. Thus, a dimensional view of psychopathology, as opposed to the prevailing categorical classification, may enrich our understanding and management of ON.

The crux of the issue is perhaps that most human behaviors exist on a continuum of “normal” to “abnormal,” making it difficult (and perhaps unnecessary) to classify ON as a discrete category besides facilitating a cross-sectional “diagnosis.” All inherently “healthy” behaviors risk becoming excessive, problematic, and impairing. Although we have yet to identify unique genetic or neurobiological markers, the pathogenesis of ON probably has biological and environmental components. Several authors, including Shisslak et al. [55] and Brooks et al. [56], have proposed a spectrum of possible eating behaviors. As these behaviors may stem from an initial aesthetic or “healthful” goal [57], although not all manifestations of EDs align with concerns predominantly centred on body image, weight, and aspirations for aesthetic or health ideals, they should also be examined in terms of their adaptive functioning and degree of dysfunction. The TOS adopts a bidimensional test structure and encompasses two related but differentiable idea of orthorexia (healthy orthorexia and ON) [34]. Many of the articles included in the review highlight healthy or “non-pathological” orthorexia and report that it is not related to psychopathological constructs in the same way that ON is [18, 20, 28]. Not adequately disentangling health from impairing orthorexia is also a methodological issue in much of the measurement literature for ON.

From a practical perspective, the mental health field has traditionally used categorical diagnoses to help inform clinical decision-making, thus thresholds (and therefore categories) may still have a place in clinical assessment and management. Categorical diagnoses have pragmatic utilities: they guide clinicians in treatment [58] and enable billing systems for clinical management [59]. As such, shifting from categorical to dimensional diagnoses would be a challenging transformation for the practice of psychiatry.

The main issue with the current literature surrounding ON revolves around how ON is operationalized and measured. Extant research has been devoted to the diagnostic criteria and assessment tools of ON [20, 28] but less so to the phenomenon of ON [8]. The self-report symptom inventories of ON and ED may be correlated largely because of behavioral similarities between ON and restrictive EDs [25, 41], rather than because of shared underlying traits or shared symptoms. More importantly, most of the reviewed literature found the majority of studies relied on the ORTO-15, an instrument that is considered unreliable and lacks validity [18, 20, 28].

Directions for Future Research

As eating and exercise addiction can be intertwined for orthorexic individuals as highlighted by Strahler et al. [27], this should be an area for future research. Exercise is not currently mentioned in the proposals of diagnostic criteria for ON, although not every associated behavior or risk factor needs to be part of the diagnostic criteria.

Additionally, no reviews have explored the overlaps between ON and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or ON and autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Perfectionistic tendencies have been found to have stronger ties to EDs than OCD [60]. Although patients with ON, EDs, and OCD may have traits of perfectionism, rigidity and a strong need for control, OCD does not, at its core, necessarily possess these personality traits. In fact, doubt (or indecision) has been described to be a central feature in the clinical appreciation of OCD [61], also known in French as “la folie du doute.” Individuals with ON value strict control over what goes into the body (either in service of weight or shape or some idea of “health”) and any “slip-up” is perceived to be a failure of self-control. However, doubt and indecision are not entirely incompatible with perfectionism both in the broader context and specifically within OCD. A diminished emphasis on achieving precise outcomes or adhering strictly to a perceived “correct” method may reduce the levels of doubt and uncertainty experienced. The multidimensional nature of perfectionism [62] and the differential relationships between ON and domains of perfectionism [63] are relevant to consider. The overlaps between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and ON are thus a direction for future research.

Previous research has also suggested similarities between AN and ASD. Individuals with AN report higher levels of social anxiety, isolation, and challenges in interpersonal relationships, which parallel women with ASD. Some have even suggested that AN is a female manifestation of ASD [64]. ASD in females, or the female autism phenotype, tend to go undiagnosed as well [65]. Recent literature, while scant, indicates a similar diagnostic overlap between ON and ASD. Patients with ON rigidly focus on their diets and perform ritualized patterns of eating [1, 66]. Patients with ASD may also go to extreme lengths to avoid certain foods due to their sensitivity to tastes and textures (and insensitivity to hunger) [67]. Moreover, they often experience social isolation due to their intolerance of others’ food beliefs. These symptoms – the inflexible adherence to routine, the pattern of repetitive behavior and narrow interests – are typical of individuals with ON and those on the autism spectrum [67]. Alexithymia, the inability to identify bodily sensations and internal states with emotions, may also underlie both disorders [68].

Conclusion

ON has emerged with changing times, culture, and practices, in particular the rise of dieting, “clean” or “pure” food labels and other health fads. The disordered eating pattern seen in patients with ON deserves further attention and research. Based on the present review of reviews, it is evident that the main gap in the ON literature is how ON per se is operationalized and measured. Previous reviews have consistently highlighted the highly variable (and contradictory) prevalence rates with different instruments to measure ON, lack of stable factor structure and psychometrics across ON measures, paucity of data on ON in clinical samples, and a need for a modern re-conceptualization of ON. Current diagnostic and assessment tools lack the specificity to differentiate pathology and must be improved upon. Without this, we have a tall order to investigate ON proper. As with other human behaviors, ON likely spans a spectrum from “normal” to “abnormal,” and “functional” to “dysfunctional.” More theoretically driven research is necessary to propel the field forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Asst/Prof Dr Donovan Yutong Lim (Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health) for reading an earlier version of the manuscript and providing useful comments and feedback. Additionally, we appreciate the detailed review and constructive comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers, which improved our work.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This research was not funded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Qin Xiang Ng.; methodology: Dawn Yi Xin Lee, Chun En Yau, Ming Xuan Han, Clarence Ong, Clyve Yu Leon Yaow, and Qin Xiang Ng; investigation: Dawn Yi Xin Lee, Chun En Yau, Ming Xuan Han, Jacqueline Jin Li Liew, Clarence Ong, Clyve Yu Leon Yaow, and Qin Xiang Ng; writing – original draft preparation: Dawn Yi Xin Lee, Chun En Yau, Ming Xuan Han, Jacqueline Jin Li Liew, Seth En Teoh, and Qin Xiang Ng; writing – review and editing: Dawn Yi Xin Lee, Chun En Yau, Ming Xuan Han, Jacqueline Jin Li Liew, Seth En Teoh, Clarence Ong, Clyve Yu Leon Yaow, Kuan Tsee Chee, and Qin Xiang Ng; supervision: Qin Xiang Ng and Kuan Tsee Chee. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was not funded.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Dunn TM, Bratman S. On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav. 2016;21:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(2):e28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freire GLM, da Silva Paulo JR, da Silva AA, Batista RPR, Alves JFN, do Nascimento Junior JRA. Body dissatisfaction, addiction to exercise and risk behaviour for eating disorders among exercise practitioners. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiss-Leizer M, Tóth-Király I, Rigó A. How the obsession to eat healthy food meets with the willingness to do sports: the motivational background of orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(3):465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cena H, Barthels F, Cuzzolaro M, Bratman S, Brytek-Matera A, Dunn T, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(2):209–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vandereycken W. Media hype, diagnostic fad or genuine disorder? Professionals’ opinions about night eating syndrome, orthorexia, muscle dysmorphia, and emetophobia. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Atchison AE, Zickgraf HF. Orthorexia nervosa and eating disorder behaviors: a systematic review of the literature. Appetite. 2022;177:106134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costa CB, Hardan-Khalil K, Gibbs K. Orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;38(12):980–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gkiouleka M, Stavraki C, Sergentanis TN, Vassilakou T. Orthorexia nervosa in adolescents and young adults: a literature review. Children. 2022;9(3):365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Strahler J, Stark R. Perspective: classifying orthorexia nervosa as a new mental illness-much discussion, little evidence. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(4):784–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grammatikopoulou MG, Gkiouras K, Polychronidou G, Kaparounaki C, Gkouskou KK, Magkos F, et al. Obsessed with healthy eating: a systematic review of observational studies assessing orthorexia nervosa in patients with diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hafstad SM, Bauer J, Harris A, Pallesen S. The prevalence of orthorexia in exercising populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eat Disord. 2023;11(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Håman L, Barker-Ruchti N, Patriksson G, Lindgren EC. Orthorexia nervosa: an integrative literature review of a lifestyle syndrome. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2015;10:26799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huynh PA, Miles S, de Boer K, Meyer D, Nedeljkovic M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and symptoms of proposed orthorexia nervosa: the contribution of assessments. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathieu S, Hanras E, Dorard G. Associations between vegetarianism, body mass index, and eating disorders/disordered eating behaviours: a systematic review of literature. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2023;74(4):424–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McComb SE, Mills JS. Orthorexia nervosa: a review of psychosocial risk factors. Appetite. 2019;140:50–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McLean CP, Kulkarni J, Sharp G. Disordered eating and the meat-avoidance spectrum: a systematic review and clinical implications. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(7):2347–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nucci D, Santangelo OE, Provenzano S, Nardi M, Firenze A, Gianfredi V. Altered food behavior and cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Opitz MC, Newman E, Alvarado Vázquez Mellado AS, Robertson MDA, Sharpe H. The psychometric properties of Orthorexia Nervosa assessment scales: a systematic review and reliability generalization. Appetite. 2020;155:104797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Örge E, Volkan E. Çocukluk çağı travmalarının yeme bozukluklarına etkisi: sistematik derleme. Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar. 2023;15(4):652–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paludo AC, Magatão M, Martins HRF, Martins MVS, Kumstát M. Prevalence of risk for orthorexia in athletes using the ORTO-15 questionnaire: a systematic mini-review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:856185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pontillo M, Zanna V, Demaria F, Averna R, Di Vincenzo C, De Biase M, et al. Orthorexia nervosa, eating disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a selective review of the last seven years. J Clin Med. 2022;11(20):6134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pruneti C, Coscioni G, Guidotti S. A systematic review of clinical psychophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorders: does the obsession with diet also alter the autonomic imbalance of orthorexic patients? Nutrients. 2023;15(3):755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Skella P, Chelmi ME, Panagouli E, Garoufi A, Psaltopoulou T, Mastorakos G, et al. Orthorexia and eating disorders in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Children. 2022;9(4):514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strahler J. Sex differences in orthorexic eating behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analytical integration. Nutrition. 2019;67-68:110534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strahler J, Wachten H, Mueller-Alcazar A. Obsessive healthy eating and orthorexic eating tendencies in sport and exercise contexts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. 2021;10(3):456–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valente M, Syurina EV, Donini LM. Shedding light upon various tools to assess orthorexia nervosa: a critical literature review with a systematic search. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(4):671–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Varga M, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(2):103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zagaria A, Vacca M, Cerolini S, Ballesio A, Lombardo C. Associations between orthorexia, disordered eating, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(3):295–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roncero M, Barrada JR, Perpiñá C. Measuring orthorexia nervosa: psychometric limitations of the ORTO-15. Span J Psychol. 2017;20:E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mitrofanova E, Pummell E, Martinelli L, Petróczi A. Does ORTO-15 produce valid data for “Orthorexia Nervosa”? A mixed-method examination of participants’ interpretations of the fifteen test items. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(3):897–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gleaves DH, Graham EC, Ambwani S. Measuring “orthorexia”: development of the eating habits questionnaire. Int J Educ Psychol Assess. 2013;12(2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barrada JR, Roncero M. Bidimensional structure of the orthorexia: development and initial validation of a new instrument. An Psicol. 2018;34(2):283–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barthels F, Barrada JR, Roncero M. Orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia as new eating styles. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hallit S, Barrada JR, Salameh P, Sacre H, Roncero M, Obeid S. The relation of orthorexia with lifestyle habits: Arabic versions of the eating habits questionnaire and the dusseldorf orthorexia scale. J Eat Disord. 2021;9(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Myrissa K, Jackson L, Kelaiditi E. Orthorexia Nervosa: examining the reliability and validity of two self-report measures and the predictors of orthorexic symptoms in elite and recreational athletes. Perform Enhanc Health. 2023;11(4):100265. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. American Psychiatric Association (APA) . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Veale D. Over-valued ideas: a conceptual analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(4):383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brytek-Matera A, Rogoza R, Gramaglia C, Zeppegno P. Predictors of orthorexic behaviours in patients with eating disorders: a preliminary study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heiss S, Coffino JA, Hormes JM. Eating and health behaviors in vegans compared to omnivores: dispelling common myths. Appetite. 2017;118:129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heiss S, Coffino JA, Hormes JM. What does the ORTO-15 measure? Assessing the construct validity of a common orthorexia nervosa questionnaire in a meat avoiding sample. Appetite. 2019;135:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Timko CA, Hormes JM, Chubski J. Will the real vegetarian please stand up? An investigation of dietary restraint and eating disorder symptoms in vegetarians versus non-vegetarians. Appetite. 2012;58(3):982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Froreich FV, Vartanian LR, Grisham JR, Touyz SW. Dimensions of control and their relation to disordered eating behaviours and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hadjistavropoulos H, Lawrence B. Does anxiety about health influence eating patterns and shape-related body checking among females? Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43(2):319–28. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Quick VM, McWilliams R, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Case-control study of disturbed eating behaviors and related psychographic characteristics in young adults with and without diet-related chronic health conditions. Eat Behav. 2012;13(3):207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Axelsson E, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Validity and clinical utility of distinguishing between DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder in pathological health anxiety: should we close the chapter? J Psychosom Res. 2023;165:111133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Novara C, Pardini S, Visioli F, Meda N. Orthorexia nervosa and dieting in a non-clinical sample: a prospective study. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(6):2081–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bulik CM, Coleman JRI, Hardaway JA, Breithaupt L, Watson HJ, Bryant CD, et al. Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25(5):543–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bemme D, Kirmayer LJ. Global mental health: interdisciplinary challenges for a field in motion. Transcult Psychiatry. 2020;57(1):3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goldberg D. A dimensional model for common mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(S30):44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shisslak CM, Crago M, Estes LS. The spectrum of eating disturbances. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18(3):209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brooks SJ, Rask-Andersen M, Benedict C, Schiöth HB. A debate on current eating disorder diagnoses in light of neurobiological findings: is it time for a spectrum model? BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lewthwaite M, LaMarre A. “That’s just healthy eating in my opinion”-Balancing understandings of health and “orthorexic” dietary and exercise practices. Appetite. 2022;171:105938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kessler RC. The categorical versus dimensional assessment controversy in the sociology of mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):171–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zimmerman M. Why hierarchical dimensional approaches to classification will fail to transform diagnosis in psychiatry. World Psychiatr. 2021;20(1):70–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Halmi KA, Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Crow S, Fichter MM, Kaplan AS, et al. The relation among perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(4):371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, Krasnow J, Wang Y, Grados MA, Cullen B, et al. An investigation of doubt in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;75:117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Smith MM, Sherry SB, Ge SY, Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Baggley DL. Multidimensional perfectionism turns 30: a review of known knowns and known unknowns. Can Psychol. 2022;63(1):16–31. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(1):177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kerr-Gaffney J, Hayward H, Jones EJH, Halls D, Murphy D, Tchanturia K. Autism symptoms in anorexia nervosa: a comparative study with females with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Autism. 2021;12(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tubío-Fungueiriño M, Cruz S, Sampaio A, Carracedo A, Fernández-Prieto M. Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(7):2190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huke V, Turk J, Saeidi S, Kent A, Morgan JF. Autism spectrum disorders in eating disorder populations: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2013;21(5):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carpita B, Cremone IM, Amatori G, Cappelli A, Salerni A, Massimetti G, et al. Investigating the relationship between orthorexia nervosa and autistic traits in a university population. CNS Spectr. 2021;27(5):613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vuillier L, Carter Z, Teixeira AR, Moseley RL. Alexithymia may explain the relationship between autistic traits and eating disorder psychopathology. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):63–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.