Abstract

Obesity significantly impacts gut microbial composition, exacerbating metabolic dysfunction and weight gain. Traditional treatment methods often fall short, underscoring the need for innovative approaches. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists have emerged as promising agents in obesity management, demonstrating significant potential in modulating gut microbiota. These agents promote beneficial bacterial populations, such as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium, while reducing harmful species like Enterobacteriaceae. By influencing gut microbiota composition, GLP-1 agonists enhance gut barrier integrity, reducing permeability and systemic inflammation, which are hallmarks of metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Additionally, GLP-1 agonists improve metabolic functions by increasing the production of short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which serve as energy sources for colonocytes, modulate immune responses, and enhance the production of gut hormones that regulate appetite and glucose homeostasis. By increasing microbial diversity, GLP-1 agonists create a more resilient gut microbiome capable of resisting pathogenic invasions and maintaining metabolic balance. Thus, by shifting the gut microbiota toward a healthier profile, GLP-1 agonists help disrupt the vicious cycle of obesity-induced gut dysbiosis and inflammation. This review highlights the intricate relationship between obesity, gut microbiota, and GLP-1 agonists, providing valuable insights into their combined role in effective obesity treatment and metabolic health enhancement.

Keywords: gut-brain axis communication, short-chain fatty acids, weight management drugs, metabolic health, gut microbiome, gut microbiota dysbiosis, obesity treatment, glp-1 agonists

Introduction and background

Obesity, affecting one in eight individuals globally [1], presents a critical public health challenge. As defined by the WHO using the BMI, obesity classifications start with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 for overweight individuals [2]. A BMI between 30.0 and 34.9 indicates Obesity Class 1, 35.0-39.9 falls into Obesity Class 2, and a BMI of 40 or above is considered Obesity Class 3, marking an extremely high risk of developing serious health complications [2]. Since 1990, the global prevalence of obesity among adults has more than doubled [1]. By 2022, 43% of adults were classified as overweight, and 16% were obese [1]. Among children and adolescents aged 5-19 years, the prevalence of overweight increased from 8% in 1990 to 20% in 2022, with 8% living with obesity [1]. The consequences of obesity are extensive and severe, significantly increasing the risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular conditions like hypertension and coronary artery disease [3], and various cancers, including those of the breast, colon, and endometrium [4]. Furthermore, obesity negatively affects bone health, elevating the likelihood of osteoarthritis and fractures [5], and it can lead to reproductive issues like polycystic ovary syndrome in women and reduced sperm quality in men [6]. Beyond these physical health impacts, obesity also places substantial economic burdens on societies through increased healthcare costs and diminished productivity, as evidenced by higher rates of absenteeism and reduced work efficiency among those affected [7].

In addition to its complex health and economic repercussions, there is one particular physiological effect of obesity that needs detailed discussion. That is its significant influence on the gut microbiome, which is the complex community of microorganisms residing in the intestinal tract. These microbes play essential roles in digesting fiber, synthesizing vitamins, stimulating the immune system, and protecting against pathogens. Moreover, gut microbes produce by-products that have significant effects on the body, both locally and systemically. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by gut bacteria are suggested to have anti-inflammatory and tumor-suppressive effects in the gut [8]. SCFAs have also been shown to stimulate the production of tight junction proteins, resulting in increased blood-brain barrier integrity [9]. These microbes also produce multiple vitamins, including thiamine, riboflavin, biotin, cobalamin, and vitamin K [10]. Thus, a balanced and diverse gut microbiota is crucial for overall health, impacting everything from nutrient absorption and energy regulation to immune function and mood [11]. However, obesity disrupts this balance, notably increasing the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. This shift enhances the body’s ability to harvest energy from the diet, leading to further weight gain and metabolic imbalance. The resulting microbial imbalance reduces overall microbial diversity and alters the production of SCFAs [12]. Additionally, obesity can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier, increasing its permeability [13]. This allows bacterial components to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation and exacerbating metabolic dysfunction, thereby creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates the condition and complicates its management [13].

Management strategies for obesity encompass a range of approaches, from lifestyle modifications such as diet and exercise to medical interventions including pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery. Lifestyle changes often serve as the first line of defense, encouraging healthier eating patterns and increased physical activity. For individuals whose adjustments prove insufficient, specific pharmacological treatments can provide additional support. Commonly prescribed medications for obesity include phentermine, orlistat, and newer agents like glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists [14].

GLP-1 agonists represent a significant advancement, particularly due to their dual role in managing diabetes and obesity [15]. These drugs mimic the action of the GLP-1 hormone, which is naturally released after eating and plays a crucial role in regulating blood glucose levels and satiety [16]. By activating GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1Rs) in the brain, these agonists reduce caloric intake through enhanced feelings of fullness and slowed gastric emptying, thereby moderating nutrient absorption and stabilizing blood glucose levels [17]. Importantly, GLP-1 agonists also exert beneficial effects on the gut microbiota. They promote the growth of beneficial bacterial populations such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while reducing harmful species like Enterobacteriaceae [18]. This advantageous adjustment of the gut microbiota strengthens intestinal barrier integrity, reduces systemic inflammation, and enhances metabolic functions. Additionally, these changes in the microbiota can affect drug pharmacokinetics, modulate immune responses, and influence lipid metabolism [19].

In this paper, we investigate the intricate relationships between obesity, the gut microbiome, and GLP-1 agonists to better understand their roles in the obesity crisis. Our focus is on the mechanisms by which GLP-1 agonists influence the gut microbiota. By analyzing these interactions, this discussion aims to shed light on the potential of GLP-1 agonists through their modulation of the gut microbiota, serving as key components in effective obesity treatment.

Review

GLP-1 agonists, obesity, and gut microbiota interactions

Obesity is associated with increased adipose tissue distribution in the body, which is a metabolically active organ that secretes a range of hormones and cytokines. In non-obese individuals, it primarily releases anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-1, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 receptor antagonists, transforming growth factor beta, and adiponectin [20], whereas in obese individuals, the nature of these secretions shifts toward pro-inflammatory factors like angiotensin II, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, leptin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 [20]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines contribute to inhibiting β-cell proliferation and the release of insulin in response to glucose [21], leading to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation that affects various organ systems, including the gut. This state of inflammation is linked with alterations in gut microbial composition, which in turn affects the body’s energy extraction processes from food. In obese individuals, there is a noted increase in energy extraction due to changes in the gut microbiota [22]. A study conducted by Palmas et al. [23] revealed that obese individuals tend to have a higher presence of bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum, like Blautia hydrogenotrophica and Ruminococcus obeum, while lean individuals generally have more from the Bacteroidetes phylum, such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. This imbalance results in a higher Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in individuals with obesity [24], which is associated with increased overall adiposity, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose regulation [25].

GLP-1 agonists are widely used for the treatment of obesity [26], which exert their effect by binding to GLP-1Rs. GLP-1Rs are variably distributed throughout the body. They are highly concentrated in the duodenum’s Brunner’s glands and found at lower levels in the stomach’s muscularis externa and the intestinal myenteric plexus neurons [27]. Outside the gut, GLP-1Rs are prevalent in the CNS, specifically in areas such as the hippocampus, neocortex, hypothalamus, spinal cord, and cerebellum [28]. The primary signaling pathway of GLP-1Rs is initiated by the activation of the Gαs protein [29]. It enhances insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells [30], moderates postprandial glucose by slowing gastric motility and reducing gastric emptying [31], and contributes to appetite regulation and weight management through feelings of satiety and fullness [32]. Activation of hypothalamic and brainstem GLP-1Rs triggers signaling that increases activity in appetite-suppressing neurons and inhibits appetite-promoting pathways involving neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide. Simultaneously, it enhances satiety pathways mediated by pro-opiomelanocortin and corticotropin-releasing hormone, leading to reduced appetite and food intake [33,34]. This is one of the mechanisms by which GLP-1 agonists exert their therapeutic effects on obesity and metabolic disorders.

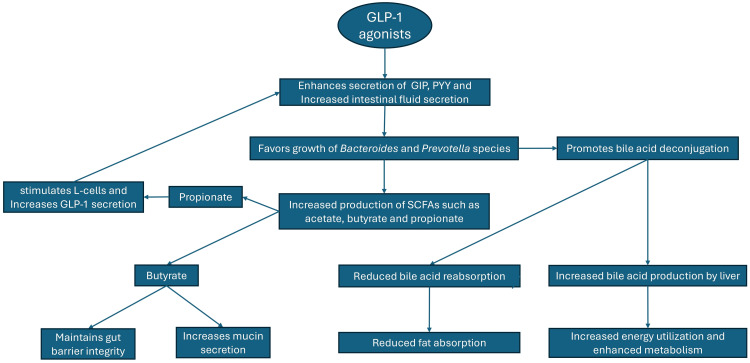

GLP-1 agonists also impact gut microbiota composition. This interaction with the gut microbiota represents an additional mechanism through which these drugs exert their therapeutic effects on obesity. They can modify the gut microbiota, potentially reversing the detrimental shifts induced by obesity and aiding in its treatment. In the following sections, we will discuss three primary ways in which GLP-1 agonists can contribute to the treatment of obesity through their effect on the gut microbiota. These pathways are illustrated and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Impact of GLP-1 agonists on gut microbiota and metabolism.

The figure shows how GLP-1 agonists favor the growth of Bacteroides and Prevotella species and enhance metabolism through increased energy utilization and bile acid production.

GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PYY, peptide YY; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid

Image credits: Kanwarmandeep Singh and Gurkamal Singh Nijjar

SCFA production

GLP-1 agonists significantly enhance the secretion of gut hormones like peptide YY (PYY) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide [35]. This elevation in hormone levels increases intestinal fluid secretion, creating a nutrient-rich environment that is particularly beneficial for specific gut microbes, such as Bacteroidetes and Prevotella [36]. This selective advantage allows these bacteria to flourish and excel at fermenting dietary fibers like inulin and resistant starches. Their activities lead to increased production of SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Propionate, in particular, directly boosts GLP-1 secretion from L-cells, establishing a positive feedback loop that enhances its effects. SCFAs also activate G protein-coupled receptor 43 on L-cells and other gut cells, contributing to further GLP-1 release [35]. Butyrate is crucial for gut barrier integrity because it serves as the main energy source for colonocytes. It stimulates the production of tight junction proteins to prevent harmful substances from passing into the bloodstream. It also promotes the secretion of mucin, a protein that forms a protective mucus layer on the intestinal lining. It also has anti-inflammatory properties that help reduce inflammation and repair damage in the gut lining, thereby maintaining a healthy and functional intestinal barrier [37]. Additionally, SCFAs modulate immune function and reduce inflammation in the gut [38]. These effects combined influence appetite regulation, insulin sensitivity, and fat storage, showcasing the potential of GLP-1 agonists in weight management. However, due to individual differences in gut microbiota composition, the treatment efficacy of these agonists can vary among individuals [39].

Gut-brain axis regulation

Gut-brain axis regulation refers to the complex communication network between the gut microbiota and the CNS, particularly the brain. This involves hormonal, neural, and immune signaling pathways [40]. In the hormonal pathway, gut microbes produce metabolites like serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid that act as hormones, influencing brain functions such as appetite, mood, and cognition [41]. In the neural pathway, the vagus nerve transmits signals related to gut motility, appetite, and stress responses [42]. In the immune pathway, the gut’s immune system interacts with the CNS through the release of cytokines and other immune signaling molecules, impacting mood, behavior, and neuroinflammation [43].

Obesity establishes a damaging cycle in the gut, largely driven by high-fat, high-sugar diets that promote the growth of Firmicutes bacteria and reduce the growth of Bacteroides [44]. These bacteria produce inflammatory molecules that damage the gut barrier, causing increased gut permeability to stimulate systemic inflammation [13]. This inflammation disrupts gut-brain communication through the vagus nerve and hormonal pathways, leading to weakened satiety signals and increased cravings for unhealthy foods, which complicates weight management [45]. It also contributes to mood swings and emotional eating due to altered mood regulation [45]. Chronic inflammation linked to obesity raises stress hormones like cortisol [46], which further disrupts the gut microbiome and diminishes SCFA production, creating a feedback loop that promotes unhealthy eating habits and weight gain.

GLP-1 agonists can play a pivotal role in disrupting the vicious cycle of obesity by supporting the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, which enhances gut mucosal integrity [47] and optimizes nutrient availability [48]. By altering this composition, they help increase the production of SCFAs, which strengthens satiety signals and reduces cravings for unhealthy foods, ultimately supporting healthier weight management [49].

Bile acid metabolism

Obesity significantly alters bile acid metabolism through several mechanisms. It often causes increased bile acid production in the liver, likely compensating for the higher dietary fat intake associated with obesity [50]. GLP-1 agonists can reshape the gut microbiome by promoting beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Verrucomicrobia, and Bacteroidetes [36] that indirectly affect bile acid metabolism. Gut bacteria alter the structure of bile acids through deconjugation, a process that has a significant impact on bile acid reabsorption and the efficiency of fat absorption. GLP-1 agonists promote the growth of bacteria that enhance deconjugation [51]. Once deconjugated, bile acids are more effectively reabsorbed in the intestines and returned to the liver for reuse. Consequently, with fewer bile acids remaining in the intestines to break down new fats, the overall absorption of dietary fats is reduced. This reduction in fat absorption means fewer calories from fats are taken in by the body, potentially decreasing overall calorie intake and aiding in weight management. In response, the liver increases its production of bile acids. This increased production enhances metabolism and further increases energy utilization.

Discussion

In the complex relationship between microbial composition, dietary influences, and metabolic and inflammatory pathways, GLP-1 agonists have emerged as a promising modality for reshaping gut microbial diversity toward a healthier profile. GLP-1 agonists demonstrate a significant ability to modulate the gut microbiota composition, which represents a promising strategy for addressing obesity and its associated inflammatory environment and offers hope for newer, more effective therapeutic strategies.

Ley et al. discovered that obese individuals, even after significant weight loss, did not fully normalize the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes observed in lean individuals [52]. These observations highlight the impact of dietary factors on gut microbiota composition in the context of obesity. Expanding on this, Feng et al. demonstrated a compelling correlation between the abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and fasting blood glucose levels among patients receiving GLP-1 agonist therapy, implicating gut microbes in the intricate regulation of blood glucose dynamics [53]. Similarly, Stenman et al. revealed a positive association between Bifidobacterium levels and enhanced insulin sensitivity, suggesting Bifidobacterium is a potential mediator of metabolic health, likely through its facilitation of GLP-1 production [54]. Yang et al. demonstrated that A. muciniphila supplementation led to elevated levels of GLP-1 and PYY, both of which suppress appetite and improve obesity [55]. Additionally, Depommier et al. found that A. muciniphila supplementation in diet-induced obese mice resulted in reductions in body weight gain and fat mass, along with an increase in fecal caloric content [56]. These findings highlight the intricate symbiosis between the gut microbiota and the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1 agonists in managing metabolic health.

Zhang et al. observed that in diabetic male rats, liraglutide was associated with more SCFA-producing bacteria, and their gut microbiota became more varied in general [57]. This helped reduce inflammation and improve obesity. They also suggested the same reason for drugs like liraglutide being good for gut bacteria and overall health. Ying et al. observed similar results and noticed that liraglutide led to more diversity in two types of bacteria, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria [58]. These bacteria are linked to more SCFA production, which contributes to reduced inflammation and helps with weight loss [35]. These studies emphasize the effect of liraglutide on specific gut bacteria. Moreover, investigations by Tsai et al. reinforced the association between GLP-1 agonists and specific gut microbial alterations and explained their role in promoting anti-inflammatory and anti-obesity effects through modulation of the gut microbiota [39].

Beyond metabolic regulation, Hunt et al. provided evidence for the anti-inflammatory properties of GLP-1 agonists in reducing obesity-related inflammation, thereby expanding the therapeutic range of these agents [59]. Collectively, these findings signify the multifaceted impact of GLP-1 agonists on gut microbiota composition and metabolic health, offering promising ways for the development of targeted therapeutic interventions for obesity and related metabolic disorders. To further elucidate these relationships, Table 1 summarizes various studies that investigate the interaction between GLP-1 agonists, obesity, and gut microbiota.

Table 1. Studies demonstrating the interaction between GLP-1 agonists, obesity, and the gut microbiota.

This table summarizes various studies that investigate the relationship between GLP-1 agonists, obesity, and the gut microbiota. It highlights the impact of GLP-1 agonists on gut microbiota composition, metabolic health, and inflammation, providing insights into their potential mechanisms and therapeutic benefits in obesity management.

GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; PYY, peptide YY; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid

| Study design | Type of study | Result | Significance |

| Tsai et al. (2021) [39] | Observational | Roseburia species were associated with decreased obesity and dyslipidemia, potentially enhancing GLP-1 responsiveness. Prevotella/Bacteroides ratio was associated with obesity, with Prevotella potentially contributing to insulin resistance. | Highlights the association between specific bacterial taxa and metabolic health markers |

| Ley et al. (2005) [52] | Observational | Decreased Firmicutes and increased Bacteroidetes in obese individuals on low-fat or low-carbohydrate diets, but levels did not fully normalize compared to lean individuals. | Indicates the impact of diet on gut microbiota composition in obesity |

| Feng et al. (2014) [53] | Observational | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii showed a significant negative correlation with fasting blood glucose levels in GLP-1 agonist-treated patients, implicating gut microbes in blood glucose regulation. | Suggests a link between gut microbiota and GLP-1 agonist efficacy in managing blood glucose levels |

| Stenman et al. (2015) [54] | Observational | Bifidobacterium was positively correlated with increased insulin sensitivity, likely due to enhanced GLP-1 production. | Indicates the potential of Bifidobacterium as a mediator of metabolic health |

| Yang et al. (2020) [55] | Interventional | Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila increased GLP-1 and PYY levels, contributing to appetite suppression and weight reduction. | Highlights the potential of A. muciniphila as a therapeutic target for obesity |

| Depommier et al. (2020) [56] | Experimental | A. muciniphila supplementation in diet-induced obese mice reduced body weight gain, total adiposity index, and fat mass gain, alongside increased fecal caloric content. | Indicates the potential of Bifidobacterium as a mediator of metabolic health |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [57] | Observational | Liraglutide was associated with increased SCFA-producing bacteria and a more diverse microbiota, potentially promoting anti-inflammatory and anti-obesity effects. | Suggests a mechanism for the beneficial effects of GLP-1 agonists on gut microbiota and metabolic health |

| Ying et al. (2023) [58] | Observational | Liraglutide was found to be associated with an increased diversity of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, which are associated with increased SCFA production and anti-inflammatory effects, as well as anti-obesity effects. | Highlights the association between liraglutide and specific gut microbial changes |

| Hunt et al. (2021) [59] | Experimental | Exendin-4, a GLP-1-like peptide, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and decreased immune response in the gut. | Indicates the anti-inflammatory potential of GLP-1 agonists in obesity-related inflammation |

| Hippe et al. (2016) [60] | Observational | Reduction in F. prausnitzii was associated with increased hemoglobin A1c values, suggesting a role in metabolic health. | Highlights the potential significance of F. prausnitzii in glucose regulation |

| Dong et al. (2022) [61] | Observational | Subjects with visceral obesity had significantly decreased levels of Bifidobacterium. | Suggests a potential role of Bifidobacterium in metabolic health |

| Turnbaugh et al. (2008) [62] | Experimental | A lard-based saturated fat diet in rodents was associated with an increased ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes along with an absolute decrease in Bacteroidetes levels. | Demonstrates the influence of dietary fats on gut microbiota composition |

| Li et al. (2016) [63] | Experimental | Palm oil was found to be associated with an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. | Indicates the impact of specific dietary components on gut microbiota composition |

| Ryu et al. (2023) [64] | Observational | Liraglutide has been linked with an increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria in the gut, correlating with elevated production of SCFAs, anti-inflammatory properties, and anti-obesity benefits. | Further supports the association between Liraglutide and specific gut microbial changes |

| Wärnberg et al. (2004) [65] | Observational | Increasing BMI was correlated with elevated IL-6 levels, indicating a pro-inflammatory state in obese individuals. | Highlights the association between obesity and systemic inflammation |

Conclusions

GLP-1 agonists have emerged as a promising therapeutic option for obesity by significantly influencing gut microbiota composition and function. These agents enhance the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as Bacteroidetes, and promote the production of SCFAs, which are crucial for gut health. Studies demonstrate that GLP-1 agonists improve gut barrier integrity, reduce systemic inflammation, and modulate metabolic pathways, leading to better glucose regulation and weight management. The positive feedback loop between SCFA production and GLP-1 secretion amplifies these beneficial effects. The ability of GLP-1 agonists to shift the microbial balance toward a healthier profile underscores their potential to disrupt the harmful cycle of obesity-induced gut dysbiosis and inflammation. Personalized treatment strategies considering individual gut microbiota variations may further enhance the efficacy of GLP-1 agonists. This multifaceted impact on gut microbiota and metabolic health positions GLP-1 agonists as a critical component in developing comprehensive and effective obesity treatments.

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Kanwarmandeep Singh, Gurkamal Singh Nijjar, Ajay Pal Singh Sandhu, Yasmeen Kaur, Abhinandan Singla, Meet Sirjana Kaur

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Kanwarmandeep Singh, Smriti K. Aulakh, Sumerjit Singh, Shivansh Luthra, Fnu Tanvir, Meet Sirjana Kaur

Drafting of the manuscript: Kanwarmandeep Singh, Smriti K. Aulakh, Gurkamal Singh Nijjar, Ajay Pal Singh Sandhu, Fnu Tanvir, Yasmeen Kaur, Abhinandan Singla

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kanwarmandeep Singh, Sumerjit Singh, Shivansh Luthra, Meet Sirjana Kaur

Supervision: Kanwarmandeep Singh, Abhinandan Singla, Meet Sirjana Kaur

References

- 1.Obesity and overweight. [ Jun; 2024 ]. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 2.Diagnosis of obesity: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. Haam JH, Kim BT, Kim EM, et al. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023;32:121–129. doi: 10.7570/jomes23031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1925–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Lancet. 2008;371:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obesity and osteoarthritis. Kulkarni K, Karssiens T, Kumar V, Pandit H. Maturitas. 2016;89:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obesity and reproductive function: a review of the evidence. Klenov VE, Jungheim ES. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26:455–460. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Impact of obesity on employment and wages among young adults: observational study with panel data. Lee H, Ahn R, Kim TH, Han E. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:139. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Morrison DJ, Preston T. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The role of the microbiome for human health: from basic science to clinical applications. Mohajeri MH, Brummer RJ, Rastall RA, Weersma RK, Harmsen HJ, Faas M, Eggersdorfer M. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1703-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective. LeBlanc JG, Milani C, de Giori GS, Sesma F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Gomaa EZ. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020;113:2019–2040. doi: 10.1007/s10482-020-01474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:342–362. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The role of gut hormones in glucose homeostasis. Drucker DJ. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:24–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI30076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Incretin hormones: their role in health and disease. Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20 Suppl 1:5–21. doi: 10.1111/dom.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, et al. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4473–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI75276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, et al. Diabetes. 2012;61:364–371. doi: 10.2337/db11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Adak A, Khan MR. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:473–493. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2943-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase glucose, alanine and triacylglycerol utilization but inhibit insulin secretion in a clonal pancreatic β-cell line. Kiely A, McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR, Newsholme P. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:113–123. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Influence of foods and nutrition on the gut microbiome and implications for intestinal health. Zhang P. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:9588. doi: 10.3390/ijms23179588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gut microbiota markers associated with obesity and overweight in Italian adults. Palmas V, Pisanu S, Madau V, et al. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5532. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84928-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.From gut microbiota through low-grade inflammation to obesity: key players and potential targets. Vetrani C, Di Nisio A, Paschou SA, et al. Nutrients. 2022;14:2103. doi: 10.3390/nu14102103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, et al. Nature. 2013;500:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recent progress and future options in the development of GLP-1 receptor agonists for the treatment of diabesity. Lorenz M, Evers A, Wagner M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:4011–4018. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK, et al. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1280–1290. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the integration of neural and endocrine responses to stress. Diz-Chaves Y, Herrera-Pérez S, González-Matías LC, Lamas JA, Mallo F. Nutrients. 2020;12:3304. doi: 10.3390/nu12113304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acting on hormone receptors with minimal side effect on cell proliferation: a timely challenge illustrated with GLP-1R and GPER. Gigoux V, Fourmy D. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;4:50. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Holst JJ. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1409–1439. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Effects of GLP-1 and its analogs on gastric physiology in diabetes mellitus and obesity. Maselli DB, Camilleri M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1307:171–192. doi: 10.1007/5584_2020_496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Effects of GLP-1 on appetite and weight. Shah M, Vella A. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9289-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Time and metabolic state-dependent effects of GLP-1R agonists on NPY/AgRP and POMC neuronal activity in vivo. Dong Y, Carty J, Goldstein N, et al. Mol Metab. 2021;54:101352. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Expression of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor in neuropeptide Y neurons of the arcuate nucleus in mice. Ruska Y, Szilvásy-Szabó A, Kővári D, et al. Brain Struct Funct. 2022;227:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00429-021-02380-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gut microbiota and GLP-1. Everard A, Cani PD. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosstalk between glucagon-like peptide 1 and gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Zeng Y, Wu Y, Zhang Q, Xiao X. mBio. 2024;15:0. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02032-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butyrate and the intestinal epithelium: modulation of proliferation and inflammation in homeostasis and disease. Salvi PS, Cowles RA. Cells. 2021;10:1775. doi: 10.3390/cells10071775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.A glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist lowers weight by modulating the structure of gut microbiota. Zhao L, Chen Y, Xia F, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:233. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gut microbial signatures for glycemic responses of GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Tsai CY, Lu HC, Chou YH, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:814770. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.814770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Strandwitz P. Brain Res. 2018;1693:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Bonaz B, Bazin T, Pellissier S. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:49. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Fung TC, Olson CA, Hsiao EY. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:145–155. doi: 10.1038/nn.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obesity, diabetes, and gut microbiota: the hygiene hypothesis expanded? Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2277–2284. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Timper K, Brüning JC. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10:679–689. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adipokine inflammation and insulin resistance: the role of glucose, lipids and endotoxin. Piya MK, McTernan PG, Kumar S. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:0. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Microbiome. 2017;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Control of appetite and energy intake by SCFA: what are the potential underlying mechanisms? Chambers ES, Morrison DJ, Frost G. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74:328–336. doi: 10.1017/S0029665114001657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Role of gut microbiota-generated short-chain fatty acids in metabolic and cardiovascular health. Chambers ES, Preston T, Frost G, Morrison DJ. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7:198–206. doi: 10.1007/s13668-018-0248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Obesity diabetes and the role of bile acids in metabolism. Tomkin GH, Owens D. J Transl Int Med. 2016;4:73–80. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Review: microbial transformations of human bile acids. Guzior DV, Quinn RA. Microbiome. 2021;9:140. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The abundance of fecal Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in relation to obesity and gender in Chinese adults. Feng J, Tang H, Li M, et al. Arch Microbiol. 2014;196:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s00203-013-0942-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Probiotic B420 and prebiotic polydextrose improve efficacy of antidiabetic drugs in mice. Stenman LK, Waget A, Garret C, Briand F, Burcelin R, Sulpice T, Lahtinen S. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2015;7:75. doi: 10.1186/s13098-015-0075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beneficial effects of newly isolated Akkermansia muciniphila strains from the human gut on obesity and metabolic dysregulation. Yang M, Bose S, Lim S, et al. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1413. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila increases whole-body energy expenditure and fecal energy excretion in diet-induced obese mice. Depommier C, Van Hul M, Everard A, Delzenne NM, De Vos WM, Cani PD. Gut Microbes. 2020;11:1231–1245. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1737307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Featured article: structure moderation of gut microbiota in liraglutide-treated diabetic male rats. Zhang Q, Xiao X, Zheng J, et al. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2018;243:34–44. doi: 10.1177/1535370217743765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Therapeutic efficacy of liraglutide versus metformin in modulating the gut microbiota for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ying X, Rongjiong Z, Kahaer M, Chunhui J, Wulasihan M. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1088187. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1088187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.GLP-1 and intestinal diseases. Hunt JE, Holst JJ, Jeppesen PB, Kissow H. Biomedicines. 2021;9:383. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faecalibacterium prausnitzii phylotypes in type two diabetic, obese, and lean control subjects. Hippe B, Remely M, Aumueller E, Pointner A, Magnet U, Haslberger AG. Benef Microbes. 2016;7:511–517. doi: 10.3920/BM2015.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Obesity is associated with a distinct brain-gut microbiome signature that connects Prevotella and Bacteroides to the brain's reward center. Dong TS, Guan M, Mayer EA, et al. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2051999. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2051999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bamboo shoot fiber prevents obesity in mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Li X, Guo J, Ji K, Zhang P. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32953. doi: 10.1038/srep32953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anti-obesity activity of human gut microbiota Bacteroides stercoris KGMB02265. Ryu SW, Moon JC, Oh BS, et al. Arch Microbiol. 2023;206:19. doi: 10.1007/s00203-023-03750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inflammatory mediators in overweight and obese Spanish adolescents. The AVENA Study. Wärnberg J, Moreno LA, Mesana MI, Marcos A. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28 Suppl 3:0–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]