Abstract

Background

Glaucoma is the second commonest cause of blindness worldwide. Non‐penetrating glaucoma surgeries have been developed as a safer and more acceptable surgical intervention to patients compared to conventional procedures.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of non‐penetrating trabecular surgery compared with conventional trabeculectomy in people with glaucoma.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 8), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to September 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to September 2013), Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS) (January 1982 to September 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 27 September 2013.

Selection criteria

This review included relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs on participants undergoing standard trabeculectomy for open‐angle glaucoma compared to non‐penetrating surgery, specifically viscocanalostomy or deep sclerectomy, with or without adjunctive measures.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the search results. We obtained full copies of all potentially eligible studies and assessed each one according to the definitions in the 'Criteria for considering studies' section of this review. We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

We included five studies with a total of 311 eyes (247 participants) of which 133 eyes (participants) were quasi‐randomised. One hundred and sixty eyes which had trabeculectomy were compared to 151 eyes that had non‐penetrating glaucoma surgery (of which 101 eyes had deep sclerectomy and 50 eyes had viscocanalostomy). The confidence interval (CI) for the odds ratio (OR) of success (defined as achieving target eye pressure without eye drops) does not exclude a beneficial effect of either deep sclerectomy or trabeculectomy (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.88). The odds of success in viscocanalostomy participants was lower than in trabeculectomy participants (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.81). We did not combine the different types of non‐penetrating surgery because there was evidence of a subgroup difference when examining total success. The odds ratio for achieving target eye pressure with or without eye drops was imprecise and was compatible with a beneficial effect of either trabeculectomy or non‐penetrating filtration surgery (NPFS) (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.79). Operative adjuvants were used in both treatment groups; more commonly in the NPFS group compared to the trabeculectomy group but no clear effect of their use could be determined. Although the studies were too small to provide definitive evidence regarding the relative safety of the surgical procedures we noted that there were relatively fewer complications with non‐filtering surgery compared to trabeculectomy (17% and 65% respectively). Cataract was more commonly reported in the trabeculectomy studies. None of the five trials used quality of life measure questionnaires. The methodological quality of the studies was not good. Most studies were at high risk of bias in at least one domain and for many, there was lack of certainty due to incomplete reporting. Adequate sequence generation was noted only in one study. Similarly, only two studies avoided detection bias. We detected incomplete outcome data in three of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides some limited evidence that control of IOP is better with trabeculectomy than viscocanalostomy. For deep sclerectomy, we cannot draw any useful conclusions. This may reflect surgical difficulties in performing non‐penetrating procedures and the need for surgical experience. This review has highlighted the lack of use of quality of life outcomes and the need for higher methodological quality RCTs to address these issues. Since it is unlikely that better IOP control will be offered by NPFS, but that these techniques offer potential gains for patients in terms of quality of life, we feel that such a trial is likely to be of a non‐inferiority design with quality of life measures.

Keywords: Aged; Humans; Middle Aged; Glaucoma, Open‐Angle; Glaucoma, Open‐Angle/surgery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sclerostomy; Sclerostomy/methods; Trabeculectomy; Trabeculectomy/methods

Plain language summary

Comparison of two surgical techniques for the control of eye pressure in people with glaucoma

Increased eye pressure is the major risk factor for developing glaucoma (a group of eye diseases that lead to progressive, irreversible damage to the optic nerve (the nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain)). Glaucoma is the second biggest cause of blindness worldwide. Eye pressure can be controlled surgically. Trabeculectomy (penetrating eye surgery) is the removal of a full‐thickness block of the trabecular meshwork (eye filtration tissue) to make a hole that allows aqueous (watery fluid present in the front part of the eyes and partly responsible for eye pressure) to filter out of the eye. It is the standard surgical procedure and has been widely practised for over 40 years. Non‐penetrating filtering surgical procedures, in which aqueous is allowed to filter out without the removal of a full‐thickness block of trabecular tissue, also aim to control eye pressure and have the reputation of being safer than trabeculectomy. The most widely practised non‐penetrating surgical procedures for glaucoma are viscocanalostomy and deep sclerectomy. Each procedure involves a different level of partial‐thickness surgical dissection into the eye filtration tissue. Surgical success is defined as lowering the eye pressure to normal limits (less than 21 mmHg) for at least 12 months after surgery. This review included five trials with 311 eyes (267 participants). These studies included 160 eyes which had trabeculectomy compared to 151 eyes that had non‐penetrating glaucoma surgery, of which 101 eyes had deep sclerectomy and 50 eyes had viscocanalostomy. This review showed that trabeculectomy is better in terms of achieving total success (pressure controlled without eyedrops) than non‐penetrating filtering procedures. Although when we looked at the outcome of partial success (pressure controlled with additional eyedrops) it was more imprecise and our results could not exclude one surgical approach being better than the other. However, the review noted that these studies had some limitations regarding their design and were too small to give definitive information on differences in complications following surgery. None of the studies measured quality of life.

Background

Description of the condition

Epidemiology

A systematic review of all population‐based surveys on blindness and low vision by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002 estimated that 37 million people are blind worldwide, with 12.3% (4.4 million) attributable to glaucoma, second only to cataract (48%) (Bourne 2006). Quigley et al project that 8.4 million people will be blind from primary glaucoma by 2010, rising to 11.1 million by 2020. The numbers who are blind are a fraction of those with the disease; the authors estimate the combined number of people with primary glaucoma to be 60.5 million by 2010, increasing by 20 million over the subsequent decade (Quigley 2006). Nevertheless, it has also been estimated that half of all people with glaucoma do not know that they have it and are, therefore, not receiving treatment that may prevent vision loss. Studies consistently report a prevalence rate for primary open‐angle glaucoma (POAG) of 1% to 2% of white adults. However, significant racial differences exist with higher rates in dark races (Tielsch 1991). In addition, the Baltimore Eye Survey described that the rates of visual impairment among African‐Americans were twice that of whites (Tielsch 1991).

Presentation and diagnosis

Primary open‐angle glaucoma, even under treatment, has been associated with measurable rates of progression of visual field loss. Published studies indicate that on an annual basis between 3% and 8% of patients under the care of an ophthalmologist may suffer progressive field damage (Kass 1976; Mao 1991; Quigley 1996). A diagnosis of open‐angle glaucoma is made on the basis of a combination of clinical signs including: intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, a clinically open angle identified by gonioscopy, optic disc (asymmetry of cup/disc ratio more than 0.2 or glaucomatous pathological disc, ranging from notching to advanced cupping, or both) and classical glaucomatous visual field changes.

Description of the intervention

Options for management include medical treatment, laser therapy and surgical intervention. In general, filtration surgery is indicated when medical and laser therapies are insufficient to control the glaucoma, and when the rate of deterioration of visual function is rapid enough to damage the patient's quality of life (Spaeth 2000). Patients with open‐angle glaucoma are operated on in order to increase the outflow of aqueous. Trabeculectomy is a filtering surgery in which removal of a full‐thickness block of eye filtration tissue is done to achieve decreased resistance to the outflow filtration of aqueous (eye fluid that contributes to eye pressure) and subsequently lowering of eye pressure. It is considered by many ophthalmologists to be the gold‐standard glaucoma operation. However, it is associated with significant postoperative complications such as hyphaema, shallow or flat anterior chamber, hypotony, choroidal detachment and hypotony maculopathy, all due to excessive filtration, and subsequent development of cataract. A new approach in trabecular surgery has been developed to minimise these complications; this is non‐penetrating filtering (trabecular) surgery (partial‐thickness removal of tissue) (Mortensen 2004). There are two widely practised technical approaches to non‐penetrating filtration surgery (NPFS). Deep sclerectomy involves the creation of conjunctival and scleral flaps similar to a trabeculectomy; a deeper inner block of scleral tissue is excised under the scleral flap creating a Descemet's window that allows aqueous seepage from the anterior chamber. Subsequent fluid percolation proceed subconjunctivally, resulting in a filtration bleb. Further placement of a collagen implant in the scleral bed has been reported to maintain the sub‐scleral space (Sanchez 1997;Tan 2001). In the second technique, viscocanalostomy, a high viscoelastic material is injected through the two open ends of Schlemm's canal to dilate it. The superficial scleral flap is sutured so tight and viscoelastic is injected beneath the scleral flap at the end of the intervention prior to closure of conjunctiva (Guedes 2006; Hamard 2002; Stegmann 1999).

How the intervention might work

Surgery is an effective way to lower IOP (Burr 2012). Bylsma hypothesises that if the safety margin of glaucoma surgery could be increased significantly without sacrificing efficacy, surgical intervention for glaucoma might be considered earlier (Bylsma 1999). Zimmerman et al reported favourable results of non‐penetrating trabeculectomy in phakic and aphakic patients (Zimmerman 1984). Stegmann et al described a similar technique in which the scleral space is filled with a viscoelastic substance. They reported a complete success rate of 82.7% and a qualified success rate of 89.0% over a 35‐month follow‐up (Stegmann 1999). Fyodorov as well as Kozlov et al, described placing a collagen implant in the scleral bed to enhance the filtration of deep sclerectomy (Fyodorov 1990; Kozlov 1990). Sanchez and co‐authors also reported a better surgical outcome when the collagen implant is used (Sanchez 1997). Chiou et al reported ultrasonic biomicroscopy findings consistent with IOP‐lowering by aqueous filtration through the thin remaining trabeculo‐descemetic membrane (TDM) to an area under the scleral flap, which was hypothetically kept open by the presence of the collagen implant (Chiou 1998). Other available implants are the reticulated hyaluronic acid implant, SKGEL implant and the hydrophilic acrylic non‐absorbable implant.

Why it is important to do this review

Although conventional trabeculectomy has been considered the optimum approach for IOP reduction, the high possibility of both early and late related complications directs the interest in evaluation of non‐penetration glaucoma surgery as a developing new surgical procedure. A systematic review is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the new procedure and its potential for fewer complications and greater acceptability to patients.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to examine the effects of non‐penetrating trabecular surgery (viscocanalostomy or deep sclerectomy with or without adjuvants) compared with conventional trabeculectomy (modified Cairns‐type technique), when used to treat people with open‐angle glaucoma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. A quasi‐randomised trial is one that uses quasi‐randomisation to allocate participants to different interventions. Quasi‐randomisation is a method of allocating participants to different forms of care that is not truly random; for example, allocation by date of birth, day of the week, medical record number, month of the year or the order in which participants are included in the study. We included studies which gave outcome data at a minimum of 12 months.

Types of participants

Participants in the trials were people with open‐angle glaucoma who had undergone the surgical treatments in question. There was no restrictions on age, gender or ethnicity.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing non‐penetrating filtration surgeries (NPFS) (viscocanalostomy and deep sclerectomy) with conventional trabeculectomy. Antimetabolites may have been used in either or both arms of the trials.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of successful procedures at least 12 months after surgery. Intraocular pressure was as measured by applanation tonometry in each included trial. Total success was defined as a target intraocular pressure (IOP) at 12 months or more post surgery being less than 21 mmHg without additional topical IOP‐lowering medications. Partial success was defined as pressure at 21 mmHg or below with or without medication.

Secondary outcomes

Progressive visual field loss according to the criteria defined in the methodology of each trial. We described the instrument used to quantify visual field loss and the definitions of progressive visual field loss for each included study, whenever possible.

Progression of optic disc damage or nerve fibre layer loss according to the criteria defined in the methodology of the trial.

Reduction of LogMAR score equal to or greater than 0.3 approximating to a Snellen visual acuity of 2 lines or more.

Quality of life measures, including whether or not there had been a reduction in use of IOP‐lowering medications following surgical interventions.

The secondary outcome measures were measured at one year.

Adverse outcomes

Any adverse effects related to the interventions. Complications following surgery include: hypotony, wound leak, infection, cataract progression and cataract surgery. We also recorded the number of cases where NPFS had to be converted to trabeculectomy.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) 2013, Issue 8, part of The Cochrane Library. www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 27 September 2013), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to September 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to September 2013), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to September 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 27 September 2013.

See: Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), LILACS (Appendix 4), mRCT (Appendix 5), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 6) and the ICTRP (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We searched the abstracts of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) for the years 1988 to 2007 using keywords:

non‐penetrating glaucoma;

deep sclerectomy/viscocanalostomy/trabeculectomy;

collagen implant/SKGEL/reticulated hyaluronate implant/polymegma/mitomycin C/5‐fluorouracil;

goniopuncture.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all studies identified electronically and by handsearching. We obtained full copies of all potentially eligible studies and assessed each according to the definitions in the 'Criteria for considering studies for this review' section. We resolved disagreements by discussion between the review authors. Where necessary we attempted to obtain additional information from the principal investigators of the trials. We arranged for translation of trials published in a language other than English.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data onto a modified version of a form developed by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group. When data were missing or difficult to determine from the paper, we contacted the authors for more information. The review authors compared the extracted data and resolved discrepancies by discussion. We extracted the following information.

Methods: methods of allocation, masking (outcome assessment), exclusions after randomisation, losses to follow‐up, compliance and study design, intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis.

Participants: country of enrolment, number randomised, age, sex, ethnicity, main inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: type of surgical method, use of adjuvants, any immediate (within two weeks) postoperative interventions.

Outcomes: we collected data on all identified outcomes together with length of follow‐up and exclusions/drop outs.

Data entry: two review authors collected the data in spreadsheets then entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed each included study for risk of bias according to chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered five parameters of quality.

Adequate sequence generation: Was the sequence of allocation of participants to groups adequately generated?

Allocation concealment: Was the sequence of allocation of participants to groups concealed until after the interventions were allocated?

Blinding (masking): Were the persons assessing outcome unaware of the assigned intervention?

Incomplete outcome data: Were rates of follow‐up and compliance similar in the groups? Was the analysis by intention‐to‐treat, i.e. were all participants analysed as randomised and were all randomised particpants analysed?

Selective reporting of outcomes: Are the reports of the study free of suggestions of selective outcome reporting?

We assessed each question‐based entry as 'low risk' of bias, 'high risk' of bias or 'unclear' and this is presented in the 'Risk of bias' table for each study included. We contacted study authors for clarification if any parameter was considered 'unclear'. We included trials considered as 'high risk' of bias on any parameter in the analysis, however, we assessed the effect of excluding these trials in a sensitivity analysis. We did not grade trials according to performance bias (masking of participants and researchers) as the trial participants and persons providing care could not be masked. However, bias could be reduced by using observers masked to the intervention when assessing the primary outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

Our primary outcome was dichotomous and thus our measure of treatment effect was the odds ratio. We compared the odds of total success (target pressure without drops) between treatment groups and the odds of control with or without drops between treatment groups.

Unit of analysis issues

We included studies which had used one eye per participant and those which used two eyes per participant, but we took account of pairing using the generic inverse variance method in our analysis. Paired studies were entered as clustered trials and an effect estimate computed. Studies with a single eye were entered and an effect estimate computed. These effect estimates were then meta‐analysed using the generic inverse method.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to extract data from the papers to enable an available case analysis. We noted the proportion of participants who did not provide outcome data in the study characteristics table. If drop outs were very high or were different across treatment groups then we assessed that study as at 'high risk' of bias and excluded it from the meta‐analysis but not from the review. In the case of missing data, we used an available case analysis method.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We carefully reviewed the trial reports to identify clinical diversity. We used the Chi2 test to assess evidence of heterogeneity and examined the I2 statistic to assess consistency between studies. We considered an I2 value of less than 25% as low heterogeneity, between 25% and 50% as moderate heterogeneity and over 50% as high heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to assess for publication bias, however, since there were fewer than 10 studies identified by our review this was not possible. Should future trials become available we will use funnel plots to assess reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We used the random‐effects model since we believe that our studies estimate effects which follow a distribution across studies. If there were fewer than three trials (i.e. limited data) we did consider use of a fixed‐effect model. If high (I2 more than 50%) heterogeneity existed we did not combine the studies, but provided a descriptive summary of results. The following comparisons were made:

deep sclerectomy versus conventional trabeculectomy;

viscocanalostomy versus conventional trabeculectomy.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analysis for the type of NPFS: sclerectomy or viscocanalostomy.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of excluding trials assessed as 'high risk' on any aspect of trial quality due to a small number of trials being identified but will do so in future updates of this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

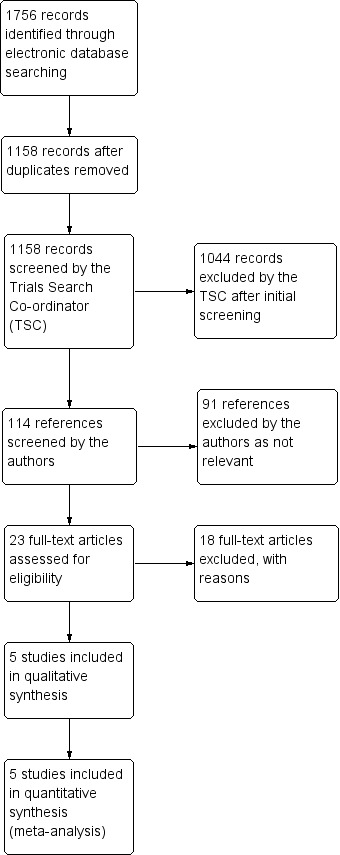

The electronic searches yielded a total of 1756 references (Figure 1). After deduplication the Trials Search Co‐ordinator scanned 1158 records and removed 1044 references which were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 114 references against the 'Criteria for considering studies for this review'. We obtained full‐text reports of 23 citations for further investigation. We contacted six trial authors via their corresponding emails: Chiselita 2001; Cillino 2005; El Sayyad 2000; Kobayashi 2003; Russo 2008 and Yalvac 2004. For Kobayashi 2003 and Yalvac 2004 we received invalid email reply messages. With the exception of Russo 2008, no other trial authors replied to our emails. We found five studies meeting the inclusion criteria. A summary of the characteristics of the included studies is given below. The other 18 studies were excluded for various reasons.

1.

Results from searching for studies for inclusion in the review

Included studies

We included five trials in the review (Cillino 2005; El Sayyad 2000; Kobayashi 2003; Russo 2008; Yalvac 2004). Evidence of quasi‐randomisation was found in Cillino 2005 and Russo 2008. Full details of the trials can be found in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Setting, participants and interventions

Three of the five trials were conducted in Europe, two in Italy and one in Turkey, and two were carried out in Asia, Japan and Saudi Arabia. Three hundred and five eyes with POAG were included across all five studies. In addition, Cillino 2005 had included six eyes with pseudoexfoliative glaucoma as part of their work. A total of 311 eyes from 247 participants were included in this review in which 133 eyes (participants) were quasi‐randomised. One hundred and fifty‐one eyes had non‐penetrating glaucoma surgery (101 deep sclerectomy and 50 viscocanalostomy) while 160 eyes had trabeculectomy.

Adjuvants

Cillino 2005 used Mitomycin C (MMC) in all participants. El Sayyad 2000 and Russo 2008 used 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) injections in a small proportion of both the non‐penetrating filtration surgery (NPFS) and trabeculectomy arms of their studies. Kobayashi 2003 used MMC in all participants in the trabeculectomy arm. The other studies did not use an adjuvant in either arm.

Goniopunctures were used in the NPFS arm of all included studies except Russo 2008, which used reticulated hyaluronate implants in all of the deep sclerectomy operated participants and Yalvac 2004 which used hyaluronate injection in all cases (viscocanalostomy). Similarly, Kobayashi 2003 used viscocanalostomy with hyaluronate injection in all operated cases. However, their goniopuncture rate was just above half of all cases.

Laser suture lysis was only used by El Sayyad 2000.

Further details of adjuvant usage are shown in Table 1.

1. Use of adjuvant/additional materials ‐ minor interventions, added operatively or used during the period of follow‐up.

| Study ID | Mito‐C | 5‐FU |

Reticulated hyaluronic implant |

Hyaluronate injection |

Goniopuncture |

Laser suture lysis |

||||||

| NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | |

| Cillino 2005 DS | 19/19 | 21/21 | 0/19 | 0/21 | 0/19 | 0/21 | 0/19 | 0/21 | 4/19 | 0/21 | 0/19 | 0/21 |

| El Sayyad 2000 DS | 0/39 | 0/39 | 17/39 | 15/39 | 0/39 | 0/39 | 0/39 | 0/39 | 4/39 | 0/39 | 0/39 | 17/39 |

| Kobayashi 2003 VC | 0/25 | 25/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 25/39 | 0/25 | 14/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | Used but n = ? |

| Russo 2008 DC | 0/43 | 0/50 | 5/43 | 2/50 | 43/43 | 0/59 | 0/43 | 0/50 | 0/43 | 0/50 | 0/43 | 0/50 |

| Yalvac 2004 VC | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 25/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/25 |

NPFS: non‐penetrating filtration surgery Trab: trabeculectomy

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

All five included studies had intraocular pressure as the primary outcome. The length of follow‐up was 12 months in Cillino 2005, El Sayyad 2000 and Kobayashi 2003, three years in Yalvac 2004 and four years in Russo 2008.

Secondary outcome measures

Field of vision and optic disc changes were only reported in Kobayashi 2003. Cillino 2005 was the only trial not to report on visual acuity changes.

Quality of life measures

Only Kobayashi 2003, El Sayyad 2000 and Russo 2008 reported changes to medication scores (Table 2). Whilst change in medication score clearly impacts on patients, none of the five trials used any quality of life questionnaires.

2. Secondary outcomes.

|

|

Medication score Mean (SD) |

Field of vision (Mean deviation at 12 months) |

Visual acuity (drop of 2 lines or more) |

|||||

| NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | |||

| Preoperative | At 12 months | Preoperative | At 12 months | |||||

| Cillino 2005 | Not reported |

Not reported | Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

Not reported |

| El Sayyad 2000 | 2.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.4) | 2.6 (0.6) | 0.27 (0.50) | Not reported | Not reported | 2 participants (due to age‐related maculopathy) | 1 participant (AMD) + 1 participant (cataract) |

| Kobayashi 2003 | 3.2 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.9) | ‐0.21(0.28) | ‐0.30(0.85) | 1 participant (postoperative increased IOP) | Not reported |

| Russo 2008 | 3.3 (1.1) | Not reported at 12 months (2.2 (1.1) at 48 months) | 3.4 (1.3) | Not reported at 12 months (1.0 (1.0) at 48 months) |

Not reported | Not reported | The mean (SD) BCVA before surgery was 0.7 ( 0.1), dropped to 0.6 (0.1) at 48 months | Mean (SD) BCVA before surgery was 0.8 (0.1), dropped to 0.4 (0.1) at 48 months believed due to higher incidence of developing cataract in 9 participants |

| Yalvac 2004 | Not reported |

Not reported | Not reported |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 2 participants (cataract) + 1 participant (AMD) + 1 participant (haemorrhagic Descemet’s membrane detachment) | 7 participants (cataract) + 1 participant (AMD) |

AMD: age‐related macular degeneration BCVA: best‐corrected visual acuity IOP: intraocular pressure NPFS: non‐penetrating filtration surgery SD: standard deviation Trab: trabeculectomy

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 studies after reviewing their full‐text. The reasons for exclusion are detailed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

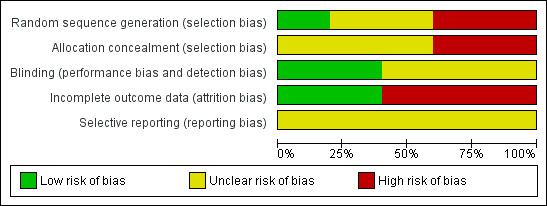

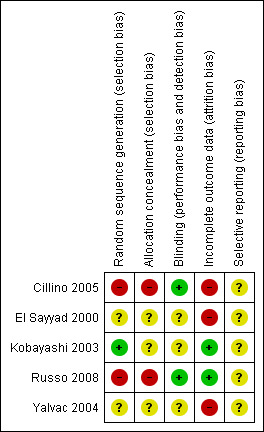

Methodological aspects of the included studies were generally a potential source of risk of bias. More details of methodological quality are shown in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Adequate sequence generation was noted only in Kobayashi 2003. Cillino 2005 and Russo 2008 showed inadequate sequence generation because they were quasi‐randomised using surgical chart numbers while it was unclear in El Sayyad 2000 and Yalvac 2004. For three out of the five studies, we assessed allocation concealment as unclear and the remaining two studies had a high risk of bias (Cillino 2005 and Russo 2008 because the chart numbers could not be concealed).

Blinding

Cillino 2005 and Russo 2008 were the only two studies where detection bias was clearly avoided by using observers masked to the intervention for the primary outcome measure. We assessed the other three studies as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

We detected incomplete outcome data in three of the included studies with post randomisation exclusions. Kobayashi 2003 and Russo 2008 avoided this source of bias because they were paired eye studies.

Selective reporting

We did not create funnel plots as less than 10 studies were included in the review.

Effects of interventions

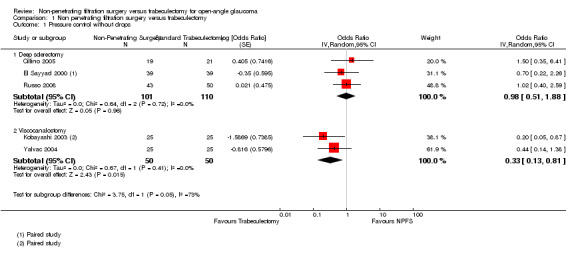

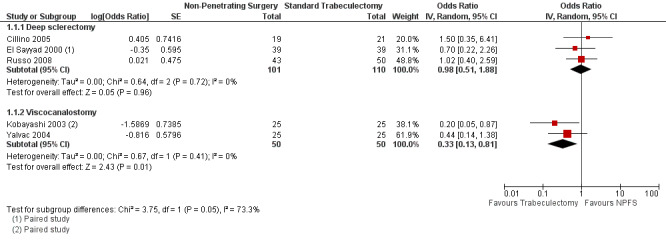

The odds of success in deep sclerectomy participants was not different to that in trabeculectomy participants (odds ratio (OR) 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 1.88) while the odds of success in viscocanalostomy participants was lower than in trabeculectomy participants (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.81). We did not combine the different types of non‐penetrating surgery because there was evidence of a subgroup difference when examining total success. Details and effect estimates are illustrated in Analysis 1.1; Figure 4.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non penetrating filtration surgery versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 1 Pressure control without drops.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Non‐penetrating filtration surgery verus trabeculectomy, outcome: 1.1 Pressure control without drops.

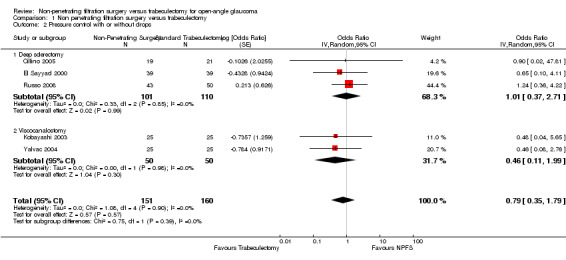

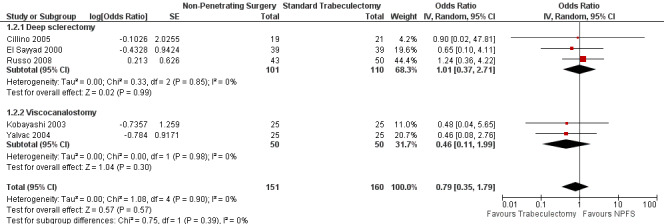

Similar findings were seen with success with out drops and partial success with or without drops although here we did estimate a pooled figure (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.79) which was not statistically significant. Details and effect estimates are illustrated in Analysis 1.2; Figure 5.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non penetrating filtration surgery versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 2 Pressure control with or without drops.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Non‐penetrating filtration surgery verus trabeculectomy, outcome: 1.2 Pressure control with or without drops.

Summary scores for these outcomes are collated in Table 2.

Secondary outcomes

Most of the participants who showed reduction in visual acuity were in the trabeculectomy group, mainly related to age‐related maculopathy or cataract.

Adverse effects

The rates of the reported adverse effects were 26 complications with non‐penetrating surgeries (17%), compared to 104 complications in the trabeculectomy group (65%). Postoperative IOP spikes were reported by Cillino 2005, Kobayashi 2003 and Russo 2008 in the non‐penetrating procedures group. There were no postoperative IOP spikes reported in the trabeculectomy arms of any of the included studies, except Russo 2008. Hypotony was reported more in the trabeculectomy arm than the non‐penetrating procedures arm of the studies but the difference in hypotony rates differed between studies. Decrease of visual acuity due to developing cataract was reported in two participants in the viscocanalostomy group compared to seven participants in the trabeculectomy group in Yalvac 2004. Similarly, nine participants were reported to develop cataract after trabeculectomy compared to none after deep sclerectomy in Russo 2008. El Sayyad 2000 also reported one participant developing cataract in the trabeculectomy group. Kobayashi 2003 reported decrease of visual acuity from postoperative increased IOP in one participant with viscocanalostomy. Similarly in the viscocanalostomy group in Yalvac 2004, there was one participant with decrease of visual acuity from Descemet's membrane detachment. Full details of adverse effects are shown in Table 3.

3. Events for adverse effects of included studies.

| Cillino 2005 | El Sayyad 2000 | Kobayashi 2003 | Russo 2008 | Yalvac 2004 | ||||||

| NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | NPFS | Trab | |

| Total number of eyes | 19 | 21 | 39 | 39 | 25 | 25 | 43 | 50 | 25 | 25 |

| Hyphaema | 4 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Shallow AC | 1 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Choroidal detachment | 1 | 6 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 4 | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Postoperative IOP spike |

3 | 0 | Not reported | Not reported | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Inflammation AC | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported | 1 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Hypotony | 1 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| Cataract progression | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 7 |

AC: anterior chamber IOP: intraocular pressure NPFS: non‐penetrating filtration surgery Trab: trabeculectomy

Discussion

Glaucoma is an important public health concern. Its irreversibility and the demographic changes of an ageing population add to the problem. The issue of intraocular pressure (IOP) control and the success rates of non‐penetrating glaucoma surgery compared to trabeculectomy remain a point of ongoing debate.

Summary of main results

There was a trend toward better IOP outcomes with trabeculectomy which was statistically significant when comparing total success in participants with viscocanalostomy with trabeculectomy. Complications appeared more common in the trabeculectomy arm, where cataract was more commonly reported. None of the studies included quality of life outcome questionnaires and the methodological quality of the studies was not high. We found evidence of a subgroup difference between viscocanalostomy and deep sclerectomy when examining total success, although since this was evidence from across studies rather than within each study, it should be treated with some caution.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Surgical expertise is one of the factors that can affect outcomes, and when considering two different surgical procedures, viscocanalostomy and deep sclerectomy, the difference in surgical expertise between the procedures might explain the difference in outcomes. None of the included studies commented on the surgical expertise of the surgeons performing either procedure. This should be considered when evaluating new, highly technical procedures such as non‐penetrating filtration surgery (NPFS) which have been practised far less in comparison to trabeculectomy which has been widely used for over 40 years. Jonescu‐Cuypers et al had first reported no success at all for viscocanalostomy but this increased to 30% in their subsequent reports (Jonescu‐Cuypers 2001; Luke 2002). Similarly, Gilmour et al described how the procedure of viscocanalostomy required a learning curve and that this might have be relevant to their outcomes when compared to trabeculectomy (Gilmour 2009).

There was differences in some specific features of the interventions in the trials. It is worth mentioning that whereas viscocanalostomy groups used high‐viscosity sodium hyaluronate in all eyes, only Russo 2008 used reticulated hyaluronic acid implants in all their deep sclerectomy participants, which may have modified the outcome of this study. The use of antimetabolites was not uniform among the five trials. Only Yalvac 2004 did not use antimetabolites in both groups. However, the overall rate of using operative adjuvants is more than double for the non‐penetrating procedures when compared to trabeculectomy. The use of antimetabolites can directly affect the success rates of either procedure (Wilkins 2005). Russo 2008 and Yalvac 2004 did not report the use of goniopuncture which is considered by some authors as the completing step in NPFS, directly affecting success rates (Mendrinos 2008).

The justification for non‐penetrating filtering surgical techniques is based on greater safety with a lower risk of complications when compared to trabeculectomy (Mendrinos 2008; Shaarawy 2004; Tan 2001). Hypotony and hyphaema were two adverse effects reported in all of the trials included in this review. Although they were recorded at lower rates in the NPFS participants than in those who had trabeculectomy, it is important to note that these risks were also low in the trabeculectomy group. Randomised controlled trials rarely have power to look reliably at adverse events and whilst we have collated all the information that we could on harms, it is important to view these data with caution.

Tan 2001 highlighted that quality of life, measured by functional status and sense of well being, is lower in patients with glaucoma compared with control participants, and is influenced by visual acuity, visual field impairment and topical medication use. In this review, little attention was paid to fields of vision in the included trials. Although both compared procedures appeared to reduce the need for medication, the difference between the two appears subtle and was only reported in three trials (El Sayyad 2000; Kobayashi 2003; Russo 2008). Visual acuity appeared to be affected mainly in the trabeculectomy group, with diversity in reporting among included trials (Table 2). None of the five trials used quality of life measure questionnaires. This was a key finding of this review.

Quality of the evidence

We planned to report treatment effects separately for the two types of NPFS. We did not combine results for the total success comparison because there was evidence of a difference in treatment effect. Because this subgroup analysis was across studies, it should be viewed with some caution. When we combined total and qualified success rates, we still found that trabeculectomy had better outcomes compared to NPFS but these differences were not statistically significant. Larger studies would be needed to assess evidence of a treatment effect when considering this outcome. Overall, the quality of the evidence was not high. Two trials were quasi‐randomised, three had post randomisation exclusions and none provided patient orientated outcomes. Surgical trials are demanding in terms of controlling bias especially for masking. Only two trials attempted to control for observation bias by masking the observers of the primary outcome.

Potential biases in the review process

Pildal 2007 highlighted that trials without adequate allocation concealment have been shown to overestimate the benefit of experimental interventions. Methodological quality issues were a strong source of bias in most of the included trials. With stricter methodological inclusion criteria, none of the five trials would have been included. It is important to consider avoiding these sources of bias in future trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The meta‐analysis by Cheng et al focused on the pooled success rates of viscocanalostomy and deep sclerectomy rather than comparative studies with specified qualifying criteria (Cheng 2004). In this review the primary outcome measure is similar to that described by Chen 1997: surgical total success when IOP is less than 21 mmHg without additional medications after one year of surgery. They reported that the probability of successful control of IOP was 82% at five years and 67% at 10 and 15 years. Ke 2011 conducted a meta‐analysis, in which their study inclusion criteria included all non‐penetrating trabecular surgeries as one entity. Similar to our review, they concluded that trabeculectomy could reduce IOP better than non‐penetrating trabecular surgeries which, however, showed lower rates of complications when compared to trabeculectomy.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review provides limited evidence that control of intraocular pressure (IOP) is better with trabeculectomy than viscocanalostomy although there is greater uncertainty around the effect with deep sclerectomy. The confidence limits are wide and the quality of evidence poor so one cannot conclude this might indicate equivalence. Results regarding harms were inconclusive but this is not surprising given that adverse events are often rare. This review has highlighted the lack of use of quality of life outcomes and the need for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with higher methodological quality to address these issues.

Implications for research.

A high‐quality, multi‐centred RCT is required to compare trabeculectomy to either deep sclerectomy or viscocanalostomy. We feel that these techniques should not be combined in one group when compared to trabeculectomy. Surgical expertise should be taken into account when allocating centres for a large RCT, i.e. the surgeons should be undertaking a defined minimum number of procedures in a year. Alternatively, an expert design could be used where participants are randomised to "expert surgeons" for either technique. Since it is unlikely that better IOP control will be offered by non‐penetrating filtration surgery but that these techniques offer potential gains for patients in terms of quality of life, we feel that the trial should be a non‐inferiority design with quality of life measures. Complications should be well defined with rigorous reporting standards and methods.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2008 Review first published: Issue 2, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 March 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

| 19 November 2007 | New citation required and major changes | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the work of Dr. Nitin Anand, Dr. Nahla Sobhy and Dr. Mohamed Khafagy for their help in the review preparation. We acknowledge the support of Anupa Shah in the preparation of the review, together with all the editorial team of the Cochrane Eyes And Vision Group (CEVG). We thank Jennifer Burr, Ann Ervin and Kristina Lindsley for their comments on the protocol and Marie Diener‐West, Ruth Thomas and Scott Fraser for their comments on the review. CEVG created and executed the electronic search strategies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Glaucoma, Open‐Angle #2 open near angle near glaucoma* #3 poag #4 primary near glaucoma* #5 chronic near glaucoma* #6 secondary near glaucoma* #7 low near tension near glaucoma* #8 low near pressure near glaucoma* #9 normal near tension near glaucoma* #10 normal near pressure near glaucoma* #11 pigment near glaucoma* #12 MeSH descriptor Exfoliation Syndrome #13 exfoliat* near glaucoma* #14 pseudoexfoliat* near syndrome* #15 pseudoexfoliat* near glaucoma* #16 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15) #17 MeSH descriptor Trabeculectomy #18 trabeculectom* #19 MeSH descriptor Sclerostomy #20 sclerostom* #21 sclerectom* #22 viscocanalostom* #23 MeSH descriptor Filtering Surgery #24 filtrat* near surg* #25 (#17 OR #18) #26 (#19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24) #27 (#25 AND #26) #28 (#16 AND #27)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 3. placebo.ab,ti. 4. dt.fs. 5. randomly.ab,ti. 6. trial.ab,ti. 7. groups.ab,ti. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp animals/ 10. exp humans/ 11. 9 not (9 and 10) 12. 8 not 11 13. exp glaucoma open angle/ 14. (simple$ adj3 glaucoma$).tw. 15. (open adj2 angle adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 16. POAG.tw. 17. (primary adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 18. (chronic adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 19. (secondary adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 20. (low adj2 tension adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 21. (low adj2 pressure adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 22. (normal adj2 tension adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 23. (normal adj2 pressure adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 24. (pigment$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 25. exp exfoliation syndrome/ 26. (exfoliat$ adj2 syndrome$).tw. 27. (exfoliat$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 28. (pseudoexfoliat$ adj2 syndrome$).tw. 29. (pseudoexfoliat$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 30. or/13‐29 31. exp trabeculectomy/ 32. trabeculectom$.tw. 33. or/31‐32 34. exp sclerostomy/ 35. sclerostom$.tw. 36. sclerectom$.tw. 37. viscocanalostom$.tw. 38. exp filtering surgery/ 39. (filtrat$ adj3 surg$).tw. 40. or/34‐39 41. 33 and 40 42. 30 and 41 43. 12 and 42

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville (Glanville 2006).

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random$.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo$.tw. 17. random$.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12‐21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29. or/25‐28 30. 29 not 10 31. 30 not (11 or 23) 32. 11 or 24 or 31 33. exp open angle glaucoma/ 34. (open adj2 angle adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 35. POAG.tw. 36. (primary adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 37. (chronic adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 38. (secondary adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 39. (low adj2 tension adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 40. (low adj2 pressure adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 41. (normal adj2 tension adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 42. (normal adj2 pressure adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 43. (pigment$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 44. exp exfoliation syndrome/ 45. (exfoliat$ adj2 syndrome$).tw. 46. (exfoliat$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 47. (pseudoexfoliat$ adj2 syndrome$).tw. 48. (pseudoexfoliat$ adj2 glaucoma$).tw. 49. or/33‐48 50. exp trabeculectomy/ 51. trabeculectom$.tw. 52. or/50‐51 53. exp glaucoma surgery/ 54. sclerostom$.tw. 55. sclerectom$.tw. 56. viscocanalostom$.tw. 57. exp filtering operation/ 58. (filtrat$ adj3 surg$).tw. 59. or/53‐58 60. 52 and 59 61. 49 and 60 62. 32 and 61

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

glaucoma$ and open or chronic or primary or low or normal or pigmentary or exfoliat$ and trabeculectom$ or sclerostom$ or sclerectom$ or viscocanalostom$

Appendix 5. metaRegister of Controlled Trials search strategy

(trabeculectomy) and (sclerostomy or sclerectomy or viscocanalostomy)

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(Trabeculectomy) AND (Sclerostomy OR Sclerectomy OR Viscocanalostomy)

Appendix 7. ICTRP search strategy

Trabeculectomy = Condition AND Sclerostomy OR Sclerectomy OR Viscocanalostomy = Intervention

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Non penetrating filtration surgery versus trabeculectomy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pressure control without drops | 5 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Deep sclerectomy | 3 | 211 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.51, 1.88] |

| 1.2 Viscocanalostomy | 2 | 100 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.13, 0.81] |

| 2 Pressure control with or without drops | 5 | 311 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.35, 1.79] |

| 2.1 Deep sclerectomy | 3 | 211 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.37, 2.71] |

| 2.2 Viscocanalostomy | 2 | 100 | Odds Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.11, 1.99] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cillino 2005.

| Methods |

Unit of analysis: participants (1 eye per participant) Method of allocation: randomised Masking (outcome assessment): masked Exclusions after randomisation: 3 eyes of 3 participants Losses to follow‐up: none stated Compliance: not stated Study design (intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis): this study compares IOP after DS and TP, using low‐dosage intraoperative MMC in both techniques. 19 eyes of 19 participants were allocated to DS with MMC and 21 eyes of 21 participants were allocated to TP with MMC. The 40 participants (eyes) were followed until the 12th month. The authors also made a comparison between the DS group with MMC and a historical control group of participants who had undergone DS without MMC. |

|

| Participants |

Country of enrolment: Italy Number randomised: 43 participants: data below refer to 40 participants (3 DS with MMC excluded) Age: DS group: 71.9 ± 7.1 years Trabeculectomy group: 68.9 ± 6.4 years Sex: DS group: 10 males, 9 females Trabeculectomy group: 10 males, 11 females Ethnicity: not stated Main inclusion criteria: patients with POAG or PEXG under maximum topical therapy Main exclusion criteria: patients with clinically significant cataract where combined surgery was indicated, and patients with diseases other than glaucoma or previous ocular surgery were excluded |

|

| Interventions |

Type of surgical method: DS versus TP Use of adjuvants: In DS with MMC cases with postoperative IOP above 21 mmHg from 3‐week follow‐up a Nd:YAG laser goniopuncture was performed Nd:YAG laser goniopuncture was performed in 4 eyes (22%) No needling of blebs or laser suture lysis was performed in either group Any immediate (within 2 weeks) postoperative interventions: none stated |

|

| Outcomes |

IOP total success (≤21 mmHg without anti‐glaucoma medications):

DS group: 15/19 (78.9%)

Trabeculectomy group: 15/21 (71.4%) IOP qualified success (≤21 mmHg with anti‐glaucoma medications): DS group: 19/19 (100%) Trabeculectomy group: 21/21 (100%) IOP failure: none Field of vision: not stated Optic disc: not stated Drop in visual acuity 2 lines or more: not stated Drop in postoperative medication score: not stated Adverse effects: DS group: 4 cases (21%) had hyphaema, 3 cases (15.8%) had postoperative IOP spike, 1 case (5.2 %) had inflammation, 1 case (5.2%) had choroidal detachment and 1 case (5.2%) had shallow AC No cases of hypotony or flat AC were reported in this group Trabeculectomy group: 8 cases (38.1%) had hypotony, 6 cases (28.6%) had choroidal detachment, 9 cases (42.8%) had hyphaema, 2 cases (9.5%) had flat AC, 7 cases (33.3%) had shallow AC and 4 cases (19%) had postoperative inflammation Length of follow‐up: 12 months Exclusions and drop outs: 3 participants were excluded from the DS group |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation was based on a surgical chart number. Participants with even numbers had DS, participants with odd numbers had trabeculectomy. This is not adequate. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | It is not possible to conceal adequately the surgical chart number from the personnel in the study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data collecting team was masked to the type of surgery performed on each eye |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 3 of the randomised participants in the DS group did not complete the procedure and hence their follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient evidence to judge as high or low |

El Sayyad 2000.

| Methods |

Unit of analysis: paired (1 eye per participant had DS, the other had trabeculectomy) Method of allocation: not stated Masking (outcome assessment): not stated Exclusions after randomisation: 2 participants were excluded and replaced due to conversion from DS to trabeculectomy. Losses to follow‐up: none Compliance: not stated Study design (intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis): 39 participants (78 eyes) with bilateral POAG underwent bilateral filtering surgery between October 1997 and March 1998. Participants were assigned randomly to receive DS in 1 eye and trabeculectomy in the other; the surgeries were scheduled with no more than 3 days between them. Participants were followed up to 12 months after surgery. |

|

| Participants |

Country of enrolment: Saudi Arabia Number randomised: 39 participants (78 eyes) Age: 53.4 ± 9.6 years (range: 38 to 75 years) Sex: men (62.5%) Ethnicity: not stated Main inclusion criteria: patients with uncontrolled glaucoma despite maximally tolerated medications Main exclusion criteria: patients with previous ocular surgery, patients younger than 35 years of age, or those with significant posterior segment eye disorders |

|

| Interventions |

Type of surgical method: DS in 1 eye and trabeculectomy in the other Use of adjuvants: ‐5FU: 17 eyes (43.6%) in deep sclerectomy group 15 eyes (38.5%) in trabeculectomy group ‐Goniopuncture: 4 eyes (10.3%) in deep sclerectomy group ‐Argon Suture lysis: 17 eyes(43.6%) in trabeculectomy group Any immediate (within 2 weeks) postoperative interventions: Resuturing of the conjunctival flap was required in 1 case with leak 3 days postoperatively in the trabeculectomy group. Argon laser suture lysis was performed in the early postoperative period in 17 eyes (43.6%) in the trabeculectomy group. |

|

| Outcomes |

IOP total success (final IOP ≤21 mmHg without anti‐glaucoma medications):

DS group: 31 eyes (79%)

Trabeculectomy group: 33 eyes (85%) IOP qualified success (final IOP ≤ 21 mmHg with anti‐glaucoma medications): DS group: 36 eyes (92.3%) Trabeculectomy group: 37 eyes (94.7%) IOP failure: DS group: 3 eyes (7.7%) Trabeculectomy group: 2 eyes (5.1%) Field of vision: not stated Optic disc: not stated Drop in visual acuity 2 lines or more: 2 eyes in the DS group and 1 eye in the trabeculectomy group showed a drop in visual acuity of 2 Snellen lines or more because of age‐related maculopathy After trabeculectomy 1 eye developed progressive cataract with the loss of 3 Snellen lines Drop in postoperative medication score: the mean number of anti‐glaucoma medications at 12 months was 0.3 ± 0.4 in the sclerectomy group and 0.27 ± 0.50 in the trabeculectomy group. This is compared to preoperative 2.4 ± 0.7 in the sclerectomy group and 2.6 ± 0.6 in the trabeculectomy group. Adverse effects: DS group: 1 case (2.6%) had conjunctival leak, 1 case (2.6%) had hyphaema and 1 case (5.1%) had iris incarceration No cases of hypotony, progressive cataract or shallow AC were reported in this group Trabeculectomy group: 1 case (2.6%) had hypotony, 3 cases (7.7%) had conjunctival leak, 3 cases (7.7%) had hyphaema, 3 cases (7.7%) had flat AC, 2 cases (5.1%) had postoperative inflammation and 1 case (2.6%) had cataract Length of follow‐up: 12 months Exclusions and drop outs: 2 patients were excluded. No drop outs. |

|

| Notes | The trial investigators did not consider successful cases of 5‐FU and goniopuncture as qualified success | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The authors say participants were assigned randomly but no definite method of randomisation was stated in the study |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information about allocation concealment was given in the study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the persons assessing outcome were unaware of the nature of the procedure in each eye of the participant |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Follow‐up rates were equal in both groups ‐ however, 2 participants were excluded from the study (and replaced) because of perforation of Descemet's membrane occurring during deep sclerectomy |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient evidence to judge as high or low |

Kobayashi 2003.

| Methods |

Unit of analysis: paired (1 eye of each participant was assigned to viscocanalostomy, the other had trabeculectomy with MMC) Method of allocation: computer‐generated numbers Masking (outcome assessment): not stated Exclusions after randomisation: none Losses to follow‐up: none Compliance: not stated Study design (intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis): patients with bilateral POAG were enrolled in a prospective clinical study. The eyes of each participant were randomly assigned to receive viscocanalostomy in one eye and trabeculectomy with MMC in the other eye. The participants were followed up for 12 months. |

|

| Participants |

Country of enrolment: Japan Number randomised: 25 participants (50 eyes) Age: 62.5 ± 7.4 years (range 43 to 83 years) Sex: 11 men, 14 women Ethnicity: Asian Main inclusion criteria: Patients with bilateral POAG who had IOP of 22 mmHg or more under medical therapy Main exclusion criteria: Patients with angle‐closure glaucoma or post‐traumatic, uveitic, neovascular or dysgenetic glaucoma, as well as patients who needed combined cataract–glaucoma procedures |

|

| Interventions |

Type of surgical method: viscocanalostomy in one eye and trabeculectomy with MMC in the other eye Use of adjuvants: Viscocanalostomy group: goniopuncture was performed weeks and months after surgery if the target pressure was not reached 14 eyes (56%) in this group required a goniopuncture with Nd:YAG laser 4.6 ± 7.3 weeks (range 2 to 22 weeks) after surgery Mean goniopuncture‐induced pressure reduction was 3.5 ± 1.4 mmHg (range 2 to 7 mmHg) Trabeculectomy group: laser suture lysis was performed if an adequate bleb was not formed or the target pressure was not reached. The study does not include any information on the number of cases that required this procedure. Any immediate (within 2 weeks) postoperative interventions: none stated |

|

| Outcomes |

IOP total success:

The surgery was considered a complete success with an IOP ≤ 20 mmHg and an IOP reduction ≥ 30% without glaucoma medication, compared with the preoperative level on medical therapy 15 viscocanalostomy‐treated eyes (60%) and 22 trabeculectomy‐treated eyes (88%) were considered complete successes IOP qualified success: A qualified success was defined as an IOP reduction ≤ 20 mmHg with glaucoma medication or an IOP reduction < 30% compared with a preoperative level with medical therapy 8 viscocanalostomy‐treated eyes (32%) and 2 trabeculectomy‐treated eyes (8%) were considered qualified successes IOP failure: IOP > 20 mmHg despite glaucoma medication 2 viscocanalostomy‐treated eyes (8%) and 1 trabeculectomy‐treated eye (4%) were considered failure Field of vision: Visual field testing with Humphrey visual field analyser, program 30‐2 Sita Fast was carried out before surgery and at 6 and 12 months after surgery The mean change in mean deviation was ‐0.21 ± 0.28 in viscocanalostomy group and ‐0.30 ± 0.85 in trabeculectomy group at 1 year Optic disc: The optic nerve was examined with a Goldmann 3‐mirror lens with recording of the size of the disc, vertical and horizontal cup/disc ratio, presence of rim notching or splinter haemorrhage, and the peripapillary atrophy. Heidelberg Retina Tomograph (HRT) examination of the optic disc was performed in each participant at baseline and at a 1‐year interval or earlier if a clinical change was recorded. To assess changes of cup area‐disc area ratio, the initial (preoperative) ratio was set to 100%, and postoperative measurements were normalised relative to the initial size. The study reported the change in HRT measurement at 1 year in both groups in cup area/disc area ratio as 101.2 ± 2.0% in the viscocanalostomy group and 101.4 ± 1.6% in the trabeculectomy group Drop in visual acuity 2 lines or more: The study reports that 1 case from the viscocanalostomy group experienced an IOP elevation and a decrease of best‐corrected visual acuity from 20/40 to 20/200, and then underwent trabeculectomy with MMC. No further data are supplied about the trabeculectomy group. Drop in postoperative medication score: The number of anti‐glaucomatous drugs before surgery in the viscocanalostomy group was 3.2 ± 0.2 (2 to 4) and at 1 year after surgery 0.7 ± 0.9 (0 to 3) While in the trabeculectomy group the number of anti‐glaucomatous drugs before surgery was 3.1 ± 0.3 (2 to 4) and at 1 year after surgery 0.4 ± 0.9 (0 to 3) Adverse effects: Viscocanalostomy group: No cases in the viscocanalostomy group were converted to trabeculectomy 1 case (4%) experienced a microperforation of the trabeculo‐Descemet's membrane with no effect on completing the procedure as viscocanalostomy. 2 cases (8%) had choroidal de‐roofing, 3 cases (12%) had a postoperative IOP spike and 4 cases (16%) had peripheral anterior synechiae formation. No cases of hypotony, shallow AC, hyphaema, posterior synechiae or cataract formation were reported in this group. Trabeculectomy group: 5 cases (20%) in this group had postoperative hypotony, 4 cases (16%) had shallow/flat AC, 4 cases (16%) of hyphaema occurred, 5 cases (20%) of peripheral anterior synechiae formation, 2 cases (8%) had failed bleb and 2 cases (8%) had cataract formation Length of follow‐up: 12 months Exclusions and drop outs: none |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Eyes were randomised within 24 hours after enrolment using computer‐generated numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No comment was made in the study regarding allocation concealment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the team assessing the outcome were unaware of the assigned procedure |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The eyes of the same participant were randomised between the 2 groups so follow‐up rates were similar in both groups and the participants were analysed on an "intention‐to‐treat" basis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient evidence to judge as high or low |

Russo 2008.

| Methods |

Unit of analysis: participants (1 eye per participant) Method of allocation: randomised Masking (outcome assessment): not stated Exclusions after randomisation: none Losses to follow‐up: none Compliance: not stated Study design (intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis): This prospective randomised clinical trial compared IOP after DS with reticulated hyaluronic acid implant and TP. 43 eyes of 43 participants were allocated to DS with implant and 50 eyes of 50 participants were allocated to TP. The 93 participants (eyes) were followed until the 48th month. |

|

| Participants |

Country of enrolment: Italy Number randomised: 93 participants Age: DS group: 66.3 ± 3.2 years TPgroup: 68.2 ± 2.1 years Sex: DS group: 23 males, 20 females TP group: 24 males, 26 females Ethnicity: not stated Main inclusion criteria: Patients with uncontrolled POAG despite maximally tolerated medications and no previous laser or surgical procedure Main exclusion criteria: Angle‐closure glaucoma, secondary open‐angle glaucoma (PEXG and pigmentary glaucoma), glaucoma surgery combined with other procedure (e.g. phacoemulsification), pregnancy or a known allergy to collagen |

|

| Interventions |

Type of surgical method: DS versus TP Use of adjuvants: When the filtering bleb showed any sign of fibrosis or became encysted at any postoperative visit, subconjunctival injection of 5 mg of 5‐FU (0.1 ml of 50 mg/ml 5‐FU) was administered and was repeated up to 7 times if necessary. No goniopuncture, needling of blebs or laser suture lysis was performed in either group. Any immediate (within 2 weeks) postoperative interventions: not stated |

|

| Outcomes |

IOP total success: (final IOP ≤21 mmHg without anti‐glaucoma medications at 36 months):

DS group: 32/43 eyes (74.4%)

TP group: 37/50 eyes (74%) IOP qualified success: (final IOP ≤21 mmHg with anti‐glaucoma medications at 36 months): DS group: 38/43 (88.3%) TP group: 43/50 (86%) IOP failure: DS group: 5 eyes (11.7%) TP group: 7 eyes (14%) Field of vision: not stated Optic disc: not stated Drop in visual acuity 2 lines or more: The mean BCVA in the DS group before surgery was 0.7 ± 0.1, dropped to 0.6 ± 0.1 at 48 months The mean BCVA in the TP group before surgery was 0.8 ± 0.1, dropped to 0.4 ± 0.1 at 48 months. This was attributed to the higher incidence of developing cataract in the TP group. Drop in postoperative medication score: The number of anti‐glaucomatous drugs before surgery in the DS group was 3.3 ± 1.1 and dropped to 2.2 ± 1.1 at 48 months after surgery In the trabeculectomy group the number of anti‐glaucomatous drugs before surgery was 3.4 ± 1.3 and dropped to 1.0 ± 1.0 at 48 months after surgery Adverse effects: DS group: Intraoperative and early postoperative period: 1 case (2.3%) had a microperforation, 1 case (2.3%) had wound leak, 1 case (2.3%) had hyphaema, 2 cases (4.6%) had hypotony, 1 case (2.3%) had inflammation, 1 case (2.3%) had elevated IOP and 1 case (2.3%) had macular oedema Late postoperative period: 2 cases (4.6%) had progressive cataract No flat AC were reported in this group TP group: Intraoperative and early postoperative period: 2 cases (4%) had wound leak, 3 cases (6%) had hyphaema, 3 cases (6%) had flat AC, 4 cases (8%) had hypotony, 4 cases (8%) had choroidal detachment, 2 cases (4%) had inflammation, 2 cases (4%) had elevated IOP and 1 case (2%) had macular oedema Late postoperative period: 9 cases (18%) had progressive cataract Length of follow‐up: 4 years (48 months) Exclusions and drop outs: none |

|

| Notes | The trial investigators reported results at 36 months and 48 months only; as well as setting 2 target IOPs, 21 mmHg and 18 mmHg. We took the results at 36 months for a target IOP of 21 mmHg. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation was based on a surgical chart number. Participants with even numbers had DS, participants with odd numbers had PT. This is not adequate. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | It is not possible to conceal adequately the surgical chart number from the personnel in the study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | IOP was measured by technicians; surgeons were unaware of IOP when performing the surgical procedure (information received from direct contact with author) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The mean follow‐up period was 47 +/‐12.3 months for the non‐penetrating DS group and 46.4 +/‐14.1 months for the trabeculectomy group (P = 0.720) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient evidence to judge as high or low risk |

Yalvac 2004.

| Methods |

Unit of analysis: 1 eye per participant Methods of allocation: not stated Masking (outcome assessment): not stated Exclusions after randomisation: 1 participant from the viscocanalostomy group was excluded and was replaced by another Losses to follow‐up: none stated Compliance: not stated Study design (intention‐to‐treat or available case analysis): 50 eyes of 50 participants were divided into 2 groups (25 eyes per group). One group underwent trabeculectomy and the other viscocanalostomy. The 2 groups were followed up to 3 years. |

|

| Participants |

Country of enrolment: Turkey Number randomised: 50 eyes of 50 participants Age: Trabeculectomy group: 66.8 ± 10.2 (range 44 to 70) Viscocanalostomy group: 53.6 ± 12.6 (range 42 to 72) Sex: Trabeculectomy group: 6 females, 19 males Viscocanalostomy group: 8 females, 17 males Ethnicity: not stated Main inclusion criteria: patients with uncontrolled POAG despite maximally tolerated medical therapy Main exclusion criteria: primary angle‐closure, neovascular, congenital, traumatic and uveitic glaucoma and previous ocular surgery |

|

| Interventions |

Type of surgical method: viscocanalostomy versus trabeculectomy Use of adjuvants: No adjunctive antimetabolite injections were given and no neodymium:YAG laser goniopunctures were performed in any participant postoperatively Any immediate (within 2 weeks) postoperative interventions: none stated |

|

| Outcomes |

IOP total success (IOP 6 to 21 mmHg without medication): Figures estimated from Kaplan Meier plots Trabeculectomy group: complete success at 1 year was 55.1% Viscocanalostomy group: complete success at 1 year was 35.3% IOP qualified success (6 to 21 mmHg with medication): Trabeculectomy group: qualified success at 1 year was 90.5% Viscocanalostomy group: qualified success at 1 year was 83.1% IOP failure: Trabeculectomy group: failure at 1 year was 9.5% Viscocanalostomy group: failure at 1 year was 16.9% Field of vision: not stated Optic disc: not stated Drop in visual acuity 2 lines or more: Trabeculectomy group: 8 participants (32%) (progressive cataract formation in 7 eyes and AMD in 1 eye) Viscocanalostomy group: 4 participants (16%) (haemorrhagic Descemet’s membrane detachment in 1 eye, cataract formation in 2 eyes and AMD in 1 eye) Drop in postoperative medication score: No clear data are available at 1 year on the drop in anti‐glaucoma medication Adverse effects: Trabeculectomy group: 7 participants (28%) had hypotony, 2 participants (8%) had hyphaema, 1 participant (4%) had pupillary block, 3 participants (12%) had bleb encapsulation and 7 participants (28%) had progressive cataract Viscocanalostomy group: 1 participant (4%) had hypotony, 1 participant (4%) had hyphaema, 1 participant (4%) had bleb encapsulation, 1 participant (4%) had haemorrhagic Descemet’s membrane detachment and 2 participants (8%) had progressive cataract Length of follow‐up: 3 years Exclusions and drop outs: 1 participant in the viscocanalostomy group was excluded and replaced. No drop outs were reported. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The authors state that participants were assigned randomly but no definite method of randomisation was described in the study |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information about allocation concealment was given in the study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the persons assessing outcome were unaware of the nature of the procedure in each eye of the participant |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Rates of follow‐up were similar in both groups ‐ however, 1 patient was excluded and replaced by another participant because of inadvertent trabeculo‐Descemet's membrane perforation |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient evidence to judge as high or low risk |

AC: anterior chamber AMD: age‐related macular degeneration DS: deep sclerectomy IOP: intraocular pressure mg: milligram ml: millilitre mmHg: millimetres of mercury MMC: Mitomycin C Nd:YAG: neodymium: yttrium–aluminium‐garnet PEXG: pseudoexfoliative glaucoma POAG: primary open‐angle glaucoma TP: trabeculectomy with the Crozafon‐De Laage Punch 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ambresin 2002 | Retrospective non‐randomised trial |

| Carassa 2003 | The trial investigators took an end point when the procedure failed, using the last IOP reading before surgical revision or addition of medication forwards to compare with other studies. This is a severe form of incomplete outcome data. |

| Chiselita 2001 | Different criteria for success from the inclusion criteria of this review. The study used a drop in IOP of 30% compared to preoperative level as a cut‐off point for success versus failure. |

| Cillino 2008 | It is a retrospective analysis of the same group of participants as in Cillino 2005 but with data assessed at 48 months. The data from Cillino 2005 at 12 months of follow‐up are already included in the review. |

| Fukuchi 2001 | Minimum follow‐up was too short: 3 months |

| Gandolfi 2005 | Conference report with not enough details for analysis and no further publication of the study |

| Gilmour 2009 | The primary outcome of the surgery was assessed at a point of 18 mmHg (not 21 mmHg), and the minimum follow‐up period was 6 months (not 12 months) |

| Huo 2008 | No randomisation is mentioned in the study and it is more like a case study of control and observational groups with no actual randomisation |

| Jonescu‐Cuypers 2001 | The follow‐up period was 6 to 8 months only which does not meet the inclusion criteria for the review |

| Lachkar 2001 | Conference report with not enough details for analysis and no further publication of the study |

| Leszczynski 2012 | The study design is a prospective controlled study and not a RCT. The investigators used a very deep sclerectomy technique (which is different from the standard deep sclerectomy surgical technique) as they excised the entire thickness of the sclera during their procedure |

| Luke 2001 | Conference report with not enough details for analysis and no further publication of the study |

| Mermoud 1999 | Non‐randomised trial |

| O'Brart 2001 | Conference report with not enough details for analysis and no further publication of the study |

| Schwenn 2004 | Assessment was only mean values, no report on success and failure rates which are not modes on analysis in the methodology of this study |

| Spinelli 2000 | Excluded as supplement 232 for this journal does not appear to exist |

| Yarangümeli 2005 | The trial investigators included cases with angle‐closure glaucoma |

| Yuan 2007 | The investigators used non‐contact Topcon CT80 tonometer to measure intraocular pressure and did not use contact tonometry in all cases. They did not use a standard viscocanalostomy surgical technique but used a modified one |

Differences between protocol and review

In the 'Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies' section two parameters to assess the risk of bias were added in the review that were not in the protocol: adequate sequence generation in selection bias and selective reporting of outcomes.

Contributions of authors

Conceiving the review: ME Designing the review: ME Co‐ordinating the review: ME Data collection for the review ‐ Designing electronic search strategies: CEVG Trials Search Co‐ordinator ‐ Undertaking manual searches: ME, MK ‐ Screening search results: ME, MK, OE ‐ Organising retrieval of papers: ME ‐ Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: ME, MK ‐ Appraising quality of papers: ME, MK ‐ Extracting data from papers: ME, MK ‐ Writing to authors of papers for additional information: ME, MK ‐ Providing additional data about papers: ME, MK ‐ Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: MK Data management for the review ‐ Entering data into RevMan: ME, CB, MK ‐ Analysis of data: ME, CB, MK, OE Interpretation of data ‐ Providing a methodological perspective: ME, MK, CB ‐ Providing a clinical perspective: ME, MK, OE ‐ Providing a policy perspective: ME, MK, OE ‐ Providing a consumer perspective: ME, MK, OE Writing the review: ME, MK, OE, RW Providing general advice on the review: ME, CB, MK, OE Securing funding for the review: ME

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

NIHR, UK.