Abstract

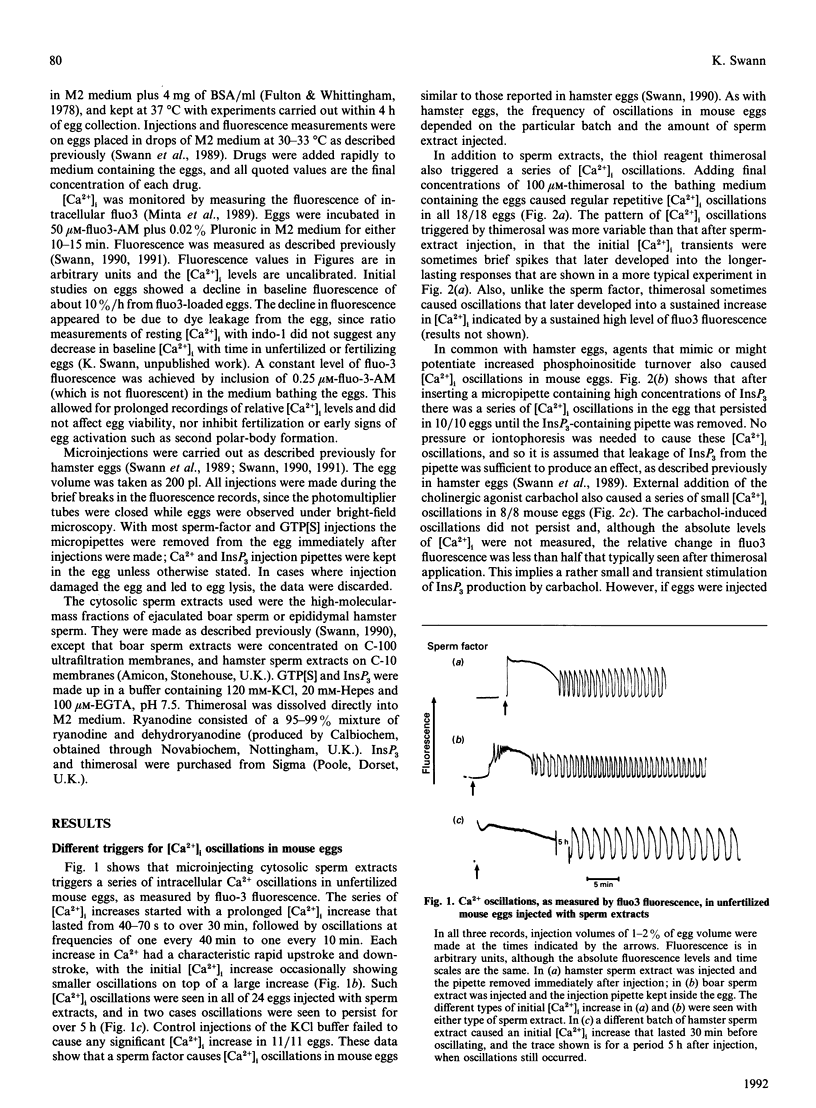

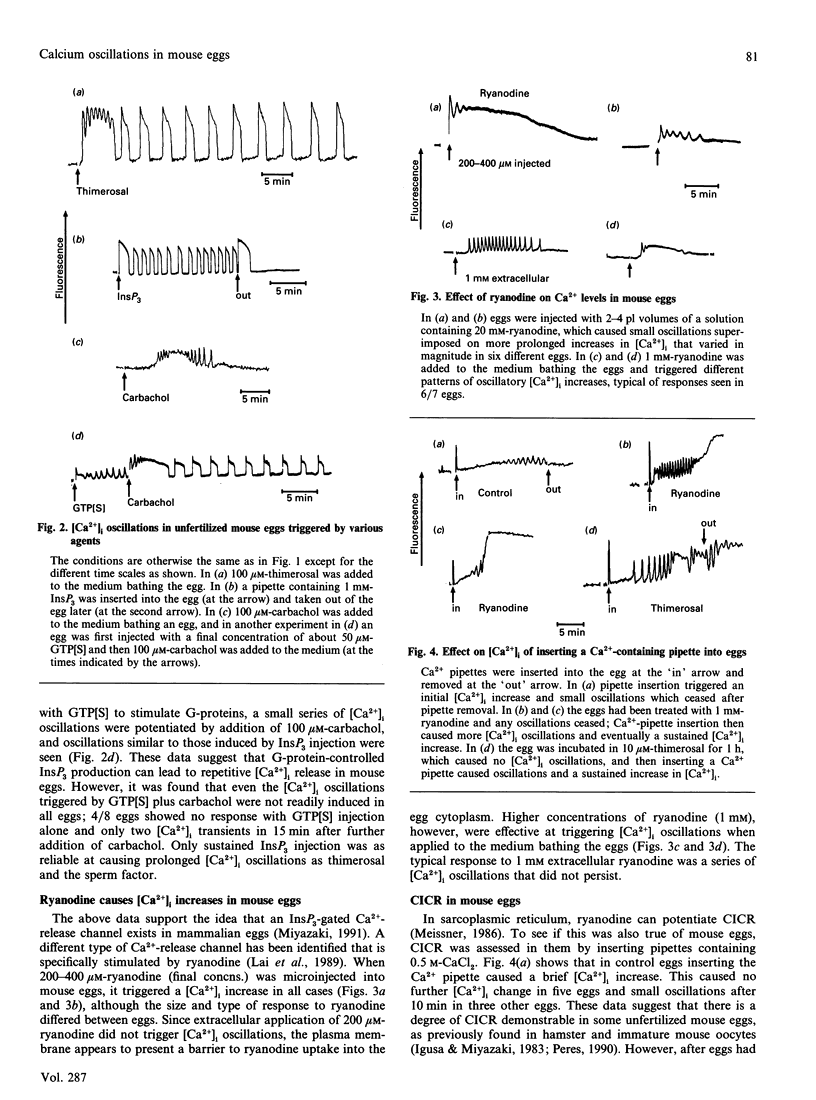

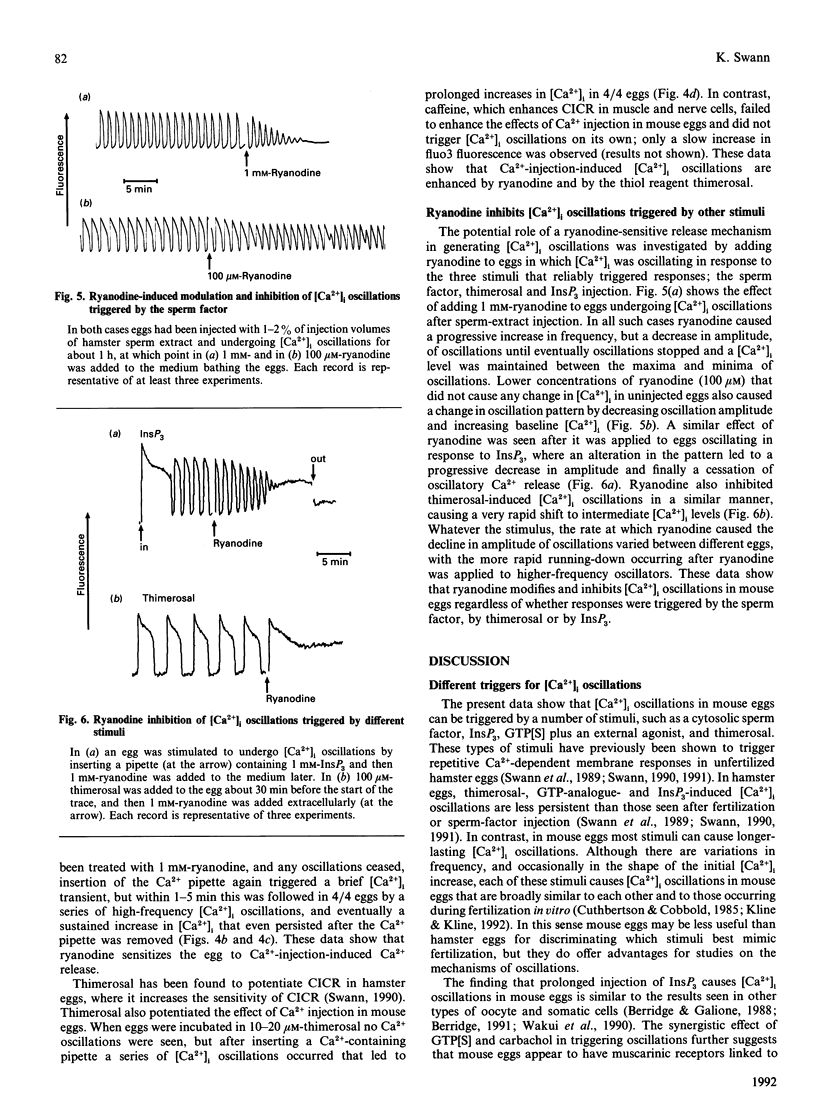

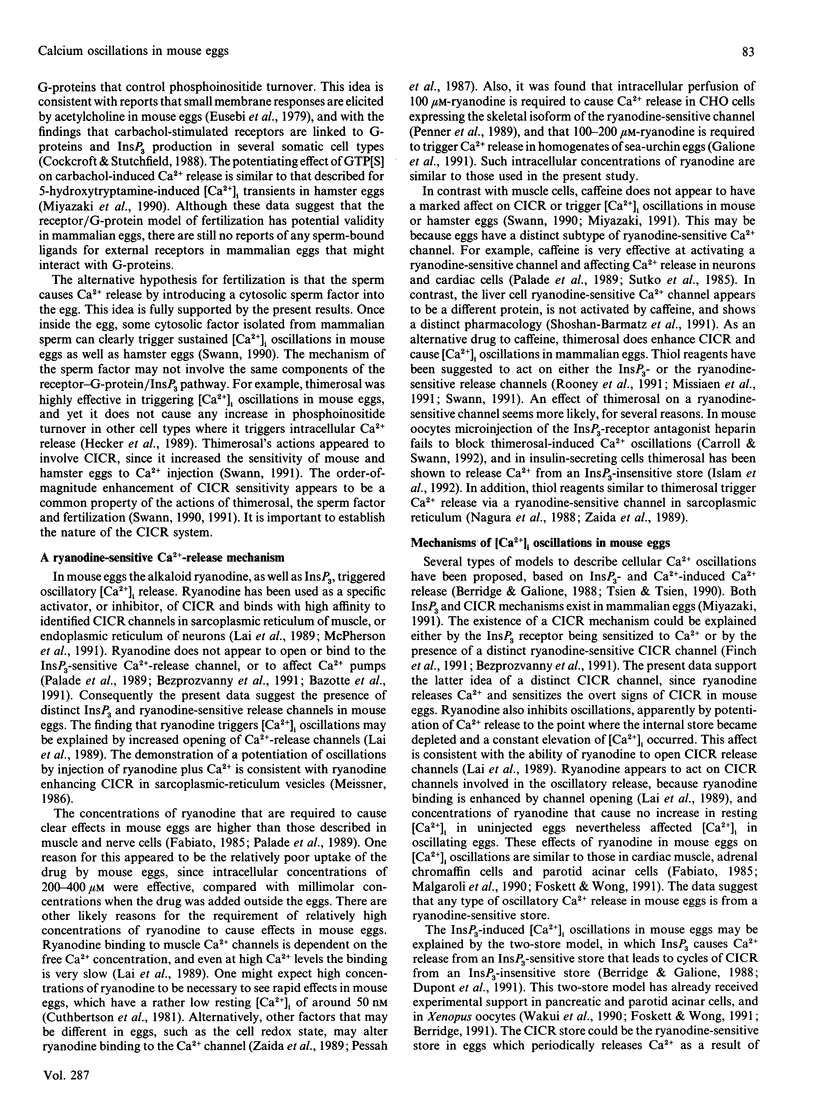

Relative intracellular free Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i) were monitored in mature unfertilized mouse eggs by measuring fluorescence of intracellular fluo3. A number of different agents were found to cause sustained repetitive transient [Ca2+]i oscillations. These were microinjection of a cytosolic sperm factor, sustained injection of Ins-(1,4,5)P1, or extracellular addition of the thiol reagent thimerosal. Stimulating G-protein activity by injection of guanosine 5'-[gamma-thio]triphosphate plus application of carbachol also caused [Ca2+]i oscillations, but less reliably than other stimuli. A role for Ca(2+)-induced Ca2+ release and a ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ channel in mouse eggs was suggested by the finding that microinjection, or external addition, of ryanodine also caused [Ca2+]i increases. Furthermore, ryanodine, along with thimerosal, increased the sensitivity of eggs to Ca(2+)-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations. When ryanodine was added to eggs oscillating in response to the sperm factor, InsP3 or thimerosal, it caused a decrease in amplitude of oscillations and eventually a block of [Ca2+]i oscillations associated with a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i. These data suggest that a ryanodine-sensitive Ca(2+)-release mechanism exists in mouse eggs and that a ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store plays a role in generating intracellular [Ca2+]i oscillations.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bazotte R. B., Pereira B., Higham S., Shoshan-Barmatz V., Kraus-Friedmann N. Effects of ryanodine on calcium sequestration in the rat liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991 Oct 9;42(9):1799–1803. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90518-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. Caffeine inhibits inositol-trisphosphate-induced membrane potential oscillations in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Biol Sci. 1991 Apr 22;244(1309):57–62. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Galione A. Cytosolic calcium oscillators. FASEB J. 1988 Dec;2(15):3074–3082. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.15.2847949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I., Watras J., Ehrlich B. E. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 1991 Jun 27;351(6329):751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek T. R., Barry V. A., Berridge M. J., Missiaen L. Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells contain an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-insensitive but caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ store that can be regulated by intraluminal free Ca2+. Biochem J. 1991 May 1;275(Pt 3):697–701. doi: 10.1042/bj2750697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft S., Stutchfield J. G-proteins, the inositol lipid signalling pathway, and secretion. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1988 Jul 26;320(1199):247–265. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1988.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley I., Whalley T., Whitaker M. Guanosine 5'-thiotriphosphate may stimulate phosphoinositide messenger production in sea urchin eggs by a different route than the fertilizing sperm. Cell Regul. 1991 Feb;2(2):121–133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson K. S., Cobbold P. H. Phorbol ester and sperm activate mouse oocytes by inducing sustained oscillations in cell Ca2+. Nature. 1985 Aug 8;316(6028):541–542. doi: 10.1038/316541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson K. S., Whittingham D. G., Cobbold P. H. Free Ca2+ increases in exponential phases during mouse oocyte activation. Nature. 1981 Dec 24;294(5843):754–757. doi: 10.1038/294754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont G., Berridge M. J., Goldbeter A. Signal-induced Ca2+ oscillations: properties of a model based on Ca(2+)-induced Ca2+ release. Cell Calcium. 1991 Feb-Mar;12(2-3):73–85. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90010-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi F., Mangia F., Alfei L. Acetylcholine-elicited responses in primary and secondary mammalian oocytes disappear after fertilisation. Nature. 1979 Feb 22;277(5698):651–653. doi: 10.1038/277651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Effects of ryanodine in skinned cardiac cells. Fed Proc. 1985 Dec;44(15):2970–2976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch E. A., Turner T. J., Goldin S. M. Calcium as a coagonist of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release. Science. 1991 Apr 19;252(5004):443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.2017683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskett J. K., Wong D. Free cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration oscillations in thapsigargin-treated parotid acinar cells are caffeine- and ryanodine-sensitive. J Biol Chem. 1991 Aug 5;266(22):14535–14538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton B. P., Whittingham D. G. Activation of mammalian oocytes by intracellular injection of calcium. Nature. 1978 May 11;273(5658):149–151. doi: 10.1038/273149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker M., Brüne B., Decker K., Ullrich V. The sulfhydryl reagent thimerosal elicits human platelet aggregation by mobilization of intracellular calcium and secondary prostaglandin endoperoxide formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Mar 31;159(3):961–968. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Frank A., Meissner G. Isolation of a Ca2(+)-releasing factor from caffeine-treated skeletal muscle fibres and its effect on Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1989 Dec;10(6):427–436. doi: 10.1007/BF01771818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igusa Y., Miyazaki S. Effects of altered extracellular and intracellular calcium concentration on hyperpolarizing responses of the hamster egg. J Physiol. 1983 Jul;340:611–632. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. S., Rorsman P., Berggren P. O. Ca(2+)-induced Ca2+ release in insulin-secreting cells. FEBS Lett. 1992 Jan 27;296(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe L. A. First messengers at fertilization. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1990;42:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline D., Kline J. T. Repetitive calcium transients and the role of calcium in exocytosis and cell cycle activation in the mouse egg. Dev Biol. 1992 Jan;149(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90265-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F. A., Erickson H. P., Rousseau E., Liu Q. Y., Meissner G. Purification and reconstitution of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle. Nature. 1988 Jan 28;331(6154):315–319. doi: 10.1038/331315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F. A., Misra M., Xu L., Smith H. A., Meissner G. The ryanodine receptor-Ca2+ release channel complex of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Evidence for a cooperatively coupled, negatively charged homotetramer. J Biol Chem. 1989 Oct 5;264(28):16776–16785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgaroli A., Fesce R., Meldolesi J. Spontaneous [Ca2+]i fluctuations in rat chromaffin cells do not require inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate elevations but are generated by a caffeine- and ryanodine-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store. J Biol Chem. 1990 Feb 25;265(6):3005–3008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson P. S., Kim Y. K., Valdivia H., Knudson C. M., Takekura H., Franzini-Armstrong C., Coronado R., Campbell K. P. The brain ryanodine receptor: a caffeine-sensitive calcium release channel. Neuron. 1991 Jul;7(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90070-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G. Ryanodine activation and inhibition of the Ca2+ release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1986 May 15;261(14):6300–6306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minta A., Kao J. P., Tsien R. Y. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. J Biol Chem. 1989 May 15;264(14):8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L., Taylor C. W., Berridge M. J. Spontaneous calcium release from inositol trisphosphate-sensitive calcium stores. Nature. 1991 Jul 18;352(6332):241–244. doi: 10.1038/352241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release and guanine nucleotide-binding protein-mediated periodic calcium rises in golden hamster eggs. J Cell Biol. 1988 Feb;106(2):345–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S., Katayama Y., Swann K. Synergistic activation by serotonin and GTP analogue and inhibition by phorbol ester of cyclic Ca2+ rises in hamster eggs. J Physiol. 1990 Jul;426:209–227. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S. Repetitive calcium transients in hamster oocytes. Cell Calcium. 1991 Feb-Mar;12(2-3):205–216. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagura S., Kawasaki T., Taguchi T., Kasai M. Calcium release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum due to 4,4'-dithiodipyridine. J Biochem. 1988 Sep;104(3):461–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson T. E., Nelson K. E. Intra- and extraluminal sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane regulatory sites for Ca2(+)-induced Ca2+ release. FEBS Lett. 1990 Apr 24;263(2):292–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozil J. P. The parthenogenetic development of rabbit oocytes after repetitive pulsatile electrical stimulation. Development. 1990 May;109(1):117–127. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade P., Dettbarn C., Alderson B., Volpe P. Pharmacologic differentiation between inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release and Ca2+- or caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular membrane systems. Mol Pharmacol. 1989 Oct;36(4):673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner R., Neher E., Takeshima H., Nishimura S., Numa S. Functional expression of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor cDNA. FEBS Lett. 1989 Dec 18;259(1):217–221. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres A. InsP3- and Ca2(+)-induced Ca2+ release in single mouse oocytes. FEBS Lett. 1990 Nov 26;275(1-2):213–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Stambuk R. A., Casida J. E. Ca2+-activated ryanodine binding: mechanisms of sensitivity and intensity modulation by Mg2+, caffeine, and adenine nucleotides. Mol Pharmacol. 1987 Mar;31(3):232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakow T. L., Shen S. S. Multiple stores of calcium are released in the sea urchin egg during fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Dec;87(23):9285–9289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney T. A., Renard D. C., Sass E. J., Thomas A. P. Oscillatory cytosolic calcium waves independent of stimulated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jul 5;266(19):12272–12282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshan-Barmatz V. High affinity ryanodine binding sites in rat liver endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 1990 Apr 24;263(2):317–320. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81403-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshan-Barmatz V., Pressley T. A., Higham S., Kraus-Friedmann N. Characterization of high-affinity ryanodine-binding sites of rat liver endoplasmic reticulum. Differences between liver and skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 1991 May 15;276(Pt 1):41–46. doi: 10.1042/bj2760041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutko J. L., Ito K., Kenyon J. L. Ryanodine: a modifier of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in striated muscle. Fed Proc. 1985 Dec;44(15):2984–2988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K. A cytosolic sperm factor stimulates repetitive calcium increases and mimics fertilization in hamster eggs. Development. 1990 Dec;110(4):1295–1302. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K., Igusa Y., Miyazaki S. Evidence for an inhibitory effect of protein kinase C on G-protein-mediated repetitive calcium transients in hamster eggs. EMBO J. 1989 Dec 1;8(12):3711–3718. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K. Thimerosal causes calcium oscillations and sensitizes calcium-induced calcium release in unfertilized hamster eggs. FEBS Lett. 1991 Jan 28;278(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80110-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K., Whitaker M. J. Second messengers at fertilization in sea-urchin eggs. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1990;42:141–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. W., Tsien R. Y. Calcium channels, stores, and oscillations. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:715–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakui M., Osipchuk Y. V., Petersen O. H. Receptor-activated cytoplasmic Ca2+ spiking mediated by inositol trisphosphate is due to Ca2(+)-induced Ca2+ release. Cell. 1990 Nov 30;63(5):1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N. F., Lagenaur C. F., Abramson J. J., Pessah I., Salama G. Reactive disulfides trigger Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum via an oxidation reaction. J Biol Chem. 1989 Dec 25;264(36):21725–21736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]