Summary

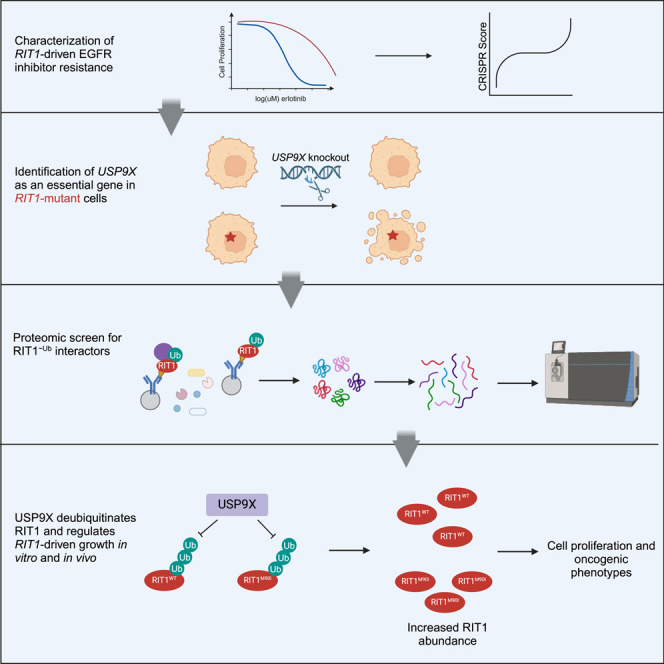

RIT1 is a rare and understudied oncogene in lung cancer. Despite structural similarity to other RAS GTPase proteins such as KRAS, oncogenic RIT1 activity does not appear to be tightly regulated by nucleotide exchange or hydrolysis. Instead, there is a growing understanding that the protein abundance of RIT1 is important for its regulation and function. We previously identified the deubiquitinase USP9X as a RIT1 dependency in RIT1-mutant cells. Here, we demonstrate that both wild-type and mutant forms of RIT1 are substrates of USP9X. Depletion of USP9X leads to decreased RIT1 protein stability and abundance and resensitizes cells to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. Our work expands upon the current understanding of RIT1 protein regulation and presents USP9X as a key regulator of RIT1-driven oncogenic phenotypes.

Subject areas: Molecular biology, Cancer, Proteomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

RIT1-driven drug resistance in vitro and in vivo depends on the deubiquitinase USP9X

-

•

USP9X knockout abrogates RIT1-driven proliferation and anchorage-independent growth

-

•

USP9X positively regulates RIT1 protein abundance in multiple lung cancer cell lines

-

•

USP9X’s catalytic activity controls the ubiquitination of wild-type and mutant RIT1

Molecular biology; Cancer; Proteomics

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and globally.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most prevalent type of lung cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common histological subtype of NSCLC.2 Given that approximately 238,000 individuals will be diagnosed with lung cancer in 2023,1 even rare molecular subtypes, defined by biomarkers found in ≤5% of tumors,3 affect tens of thousands of individuals every year. In 2014, RIT1 (Ras-like in all tissues) was identified as a rare LUAD oncogene that activates RAS signaling in tumors without canonical epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or KRAS mutations.4,5 RIT1 is mutated in 2% of LUAD tumors and amplified in another 14%.4,5 The biological effect of RIT1 amplifications in lung cancer is not well understood, but recent work suggests that RIT1 amplifications phenocopy mutant RIT1.6 In addition to LUAD, RIT1 alterations have been identified in other cancers such as myeloid malignancies, uterine carcinosarcoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma.7,8,9 Additionally, germline variants in RIT1 cause Noonan syndrome,10 an inherited “RASopathy” characterized by cardiac abnormalities, distinct facial features, and developmental delay, among other phenotypes.

RIT1 is an RAS-related small GTPase with structural similarity to KRAS.4,11,12 Similarly to other RAS proteins, RIT1 cycles between GDP- and GTP-bound states and can activate downstream MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and AKT signaling when bound to GTP.4,13,14 Although RIT1 is known to affect MAPK signaling, this regulation differs across cell types.4,14,15 Of the currently known mutations, the M90I variant (RIT1M90I) is most prevalent in lung cancer, although there is a diversity of other somatic variants that occur, mostly clustering near the switch II domain.4 RIT1 mutants have similar or increased GTP loading compared to wild-type RIT1, but wild-type RIT1 is also GTP loaded.14 This is in contrast to KRAS, whose activity is tightly regulated by GTPase-activating proteins and guanine exchange factors; mutations in KRAS impair this regulation and substantially increase the GTP-to-GDP ratio of KRAS.16 RIT1 mutations, however, appear to ablate regulation of RIT1 protein abundance.14 Wild-type RIT1 can be polyubiquitinated and targeted for proteasomal degradation by the CUL3 RING E3 ligase and the adaptor protein LZTR1 (leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1), but mutant forms of RIT1 evade this regulation.14 LZTR1 appears to be a critical regulator of RIT1 in Noonan syndrome because bi-allelic inactivating mutations in LZTR1 lead to increased RIT1 expression and, like mutant RIT1, cause Noonan syndrome.14,17,18 This mechanism is not exclusive to Noonan syndrome and has also been explored in the context of cancer. LZTR1 mutations are found in myeloid malignancies, and LZTR1 knockout increases the abundance of RIT1 in these cells, thereby promoting increased phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and ERK1/27,19,.20

Recent work suggests that mass action of mutant RIT1 molecules recruits RAF kinases to the plasma membrane and activates RAS-related signaling and cell proliferation.21 Increased abundance of RIT1M90I is mediated by resistance to LZTR1-mediated degradation,14 but it is not yet clear how overexpression of wild-type RIT1 is maintained within the cell. Multiomic analyses that examined proteomic, phosphoproteomic, and transcriptomic datasets revealed that overexpression of wild-type RIT1 phenocopies RIT1M90I in terms of gene expression and activation of effector pathways.6 Our current understanding of RIT1 oncogenesis is converging on the notion that protein abundance is crucial for cancer progression driven by RIT1; however, in LUAD, it is not clear how RIT1 protein abundance or other mechanisms contribute to tumor growth.

In order to better understand RIT1 biology and genetic dependencies, we previously designed a CRISPR screening approach to identify genes required for RIT1M90I-driven resistance to EGFR inhibitors such as erlotinib and osimertinib.15,22 This screen utilized EGFR-mutant PC9-Cas9 LUAD cells, which are sensitive to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).23 Expression of oncogenic mutants—including RIT1M90I and KRASG12V—confers EGFR TKI resistance.15,24 Although RIT1 mutations generally do no co-occur with other driver mutations (including EGFR), there have been instances of RIT1 mutations developing as a resistance mechanism to ALK inhibitors in ALK+ lung cancer.25 The PC9-Cas9/EGFR TKI system is conceptually similar to the widely used Ba/F3 model system.26 Ba/F3 cells are a mouse pro-B cell line dependent on interleukin 3 (IL-3) for survival.26 Expression of a driver oncogenic mutation—such as EGFR—renders these cells IL-3 independent.26 The Ba/F3 model system has been used since the late 1980s to understand the biology of driver genes and test the sensitivity to targeted therapies.27 The PC9-Cas9-based system is analogous to this, given that expression of oncogenes renders PC9-Cas9 cells insensitive to EGFR inhibitors.15,24

To date, chemotherapy and immunotherapy are the only treatment options for RIT1-driven cancers; therefore, the identification of additional genetic vulnerabilities could be a key step in developing new targeted therapies and personalized medicine approaches. Furthermore, resistance to EGFR inhibitors remains a major clinical problem. Up to 35% of patients are predicted to harbor intrinsic resistance mutations, and even sensitive tumors commonly acquire resistance 1–2 years post-treatment.28,29 Therefore, our CRISPR screening strategy also provides important insight into the biology of TKI resistance.

To identify additional regulators of RIT1 abundance beyond LZTR1, we looked for genetic dependencies of RIT1 in ubiquitin-related genes and identified the deubiquitinase (DUB) USP9X as a candidate. As a DUB, USP9X removes polyubiquitin chains and prevents the degradation of protein substrates.30,31,32,33,34,35 In the context of cancer, USP9X can be upregulated or downregulated in various cancer types, depending on the target substrates.36 In LUAD, USP9X has been found amplified,5,24 deleted,5,24 and mutated.24,37,38,39,40 The exact consequences of these diverse mutations have yet to be fully elucidated. In NSCLC, USP9X has been characterized as an oncogene,41,42,43 and high USP9X expression is associated with poorer overall survival.44 Beyond this study, an understanding of USP9X alterations in NSCLC is lacking. Most sequencing panels do not include USP9X; even in a study that analyzed pre- and post-osimertinib treatment tumors, USP9X alterations were not assessed.45 As such, we do not have a succinct understanding of how USP9X functions in NSCLC or in targeted therapy resistance.

Here, we demonstrate that both wild-type and mutant RIT1 are substrates of USP9X, and USP9X is an important regulator of RIT1-driven proliferation in vitro and in vivo. This work expands upon our understanding of RIT1 biology and presents USP9X as a potentially important clinical target for future studies.

Results

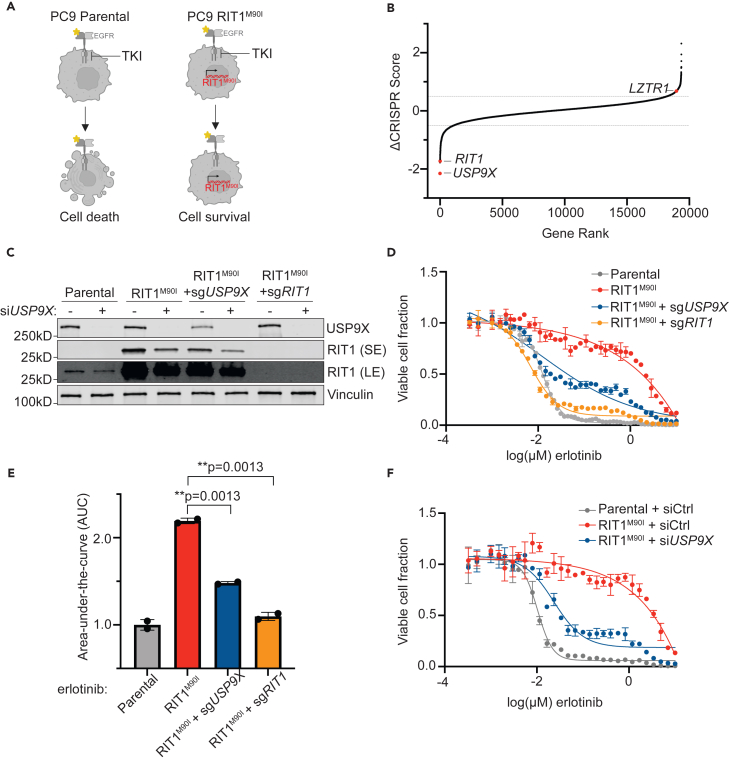

USP9X is an essential gene in RIT1-mutant cells

To identify potential regulators of RIT1 protein abundance, we analyzed data from our previous CRISPR screen of genetic dependencies of RIT1M90I. In the prior work, we identified genes that were required for RIT1M90I to promote resistance to the EGFR TKI erlotinib in EGFR-mutant PC9-Cas9 LUAD cells15 (Figure 1A). When comparing the CRISPR scores in erlotinib-treated vs. DMSO-treated screens, RIT1 emerged as a top essential gene, as expected (Figures 1B and S1A; Table S1). Another top essential gene was the deubiquitinase USP9X (Figures 1B and S1A; Table S1). To validate the result of the screen that USP9X is necessary for RIT1-induced resistance to EGFR inhibition, we generated pooled populations of RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells harboring a guide RNA targeting USP9X or RIT1 (Figure 1C). Knockout of USP9X or RIT1 resensitized cells to erlotinib (Figures 1D and 1E) and osimertinib (Figures S1B and S1C). We previously found that RIT1M90I rescued phospho-AKT signaling in EGFR TKI-treated cells,15 so we investigated how USP9X loss affected this signaling. USP9X knockdown led to a reduction of pAKT (serine 473) in parental PC9-Cas9 cells and a reduction of pAKT in RIT1-mutant cells (Figure S1D). This suggests that USP9X loss may abrogate currently known mechanisms of RIT1M90I-mediated EGFR TKI resistance. We confirmed that siUSP9X-treated RIT1M90I-mutant cells were resensitized to erlotinib (Figures 1F and S1E) and osimertinib (Figures S1F and S1G). Together, these experiments show that USP9X is required for RIT1-driven drug resistance in RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells.

Figure 1.

USP9X depletion reverses RIT1-driven drug resistance

(A) Schematic of RIT1-driven EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) resistance. Left, EGFR-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells are sensitive to EGFR TKIs such as erlotinib. Right, expression of RIT1M90I in PC9-Cas9 cells confers EGFR TKI resistance. Figure created with Biorender.com.

(B) Gene rank plot of previously published CRISPR/Cas9 whole-genome screen performed in RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells.15 ΔCRISPR Score is the difference between CRISPR scores in the erlotinib screen vs. CRISPR scores in the DMSO screen.

(C) Western blot of PC9-Cas9 cells treated with siCtrl or siUSP9X for 48 h. RIT1 bands are shown from a short exposure (SE) and long exposure (LE) to visualize both wild-type and mutant RIT1 abundance. Vinculin serves as a loading control.

(D) Dose-response curves of parental PC9-Cas9 cells and RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells with indicated gene knockouts (sgRIT1 and sgUSP9X) treated with erlotinib for 72 h. Knockouts confirmed from western blot in (C). CellTiterGlo was used to quantify viable cell fraction determined by normalization to DMSO control. Data shown are the mean ± SD of two technical replicates. Data are representative results from n = 2 independent experiments.

(E) Area under the curve (AUC) analysis of dose-response curves in (D). p values calculated by unpaired two-tailed t tests.

(F) Dose-response curves of RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells treated with siCtrl or siUSP9X for 48 h, prior to treatment with erlotinib for 72 h. Knockdowns validated by western blot in (C). CellTiterGlo was used to quantify viable cell fraction determined by normalization to DMSO control. Data shown are the mean ± SD of two technical replicates. Data are representative results from n = 3 independent experiments.

Given that the protein abundance of RIT1 is known to be important for its function,14 we were intrigued to see the deubiquitinase USP9X as a top essential gene in RIT1-mutant cells (Figures 1B and S1A; Table S1). We hypothesized that USP9X may be positively regulating RIT1 levels, and USP9X knockout would reduce RIT1 protein abundance. Indeed, USP9X knockout reduced RIT1M90I and RIT1WT protein abundance, and complete ablation of USP9X with an additional siRNA resulted in further reduction of RIT1M90I (Figure 1C). These data suggest that USP9X positively regulates RIT1 protein abundance.

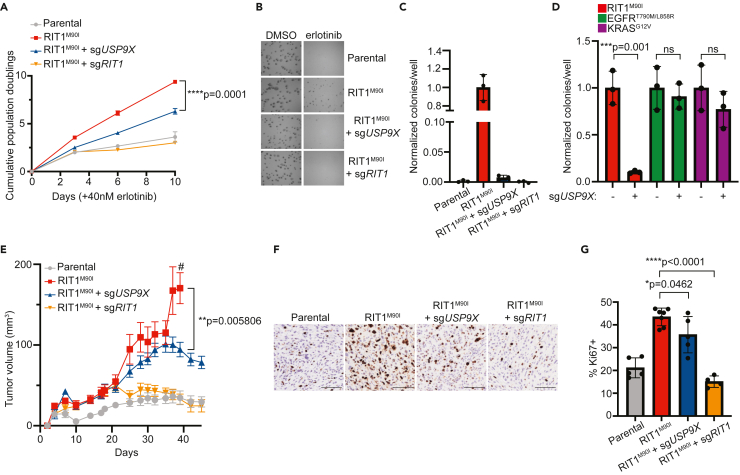

In addition to EGFR TKI resistance, expression of RIT1M90I is known to promote anchorage-independent growth.4 Given this, we investigated how USP9X regulates proliferation and anchorage independence in RIT1-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells. Under normal media conditions, genetic depletion of RIT1 and USP9X did not affect 2D proliferation of RIT1-mutant cells (Figure S2A). In the context of erlotinib, PC9-Cas9-RIT1M90I cells depend on RIT1 for growth; therefore, genes required under erlotinib treatment are RIT1 dependency genes (Figure 1A). Because of this, we expect that the effect of USP9X depletion will be most pronounced when cells are treated with an EGFR inhibitor. Under erlotinib treatment, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X cells and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 cells proliferated slower than RIT1M90I cells (Figure 2A). In addition to 2D growth, we explored 3D growth via soft agar colony formation assays in DMSO and erlotinib (Figure 2B). Whereas RIT1M90I promoted anchorage-independent growth in erlotinib, combined RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 cells formed significantly fewer colonies compared to RIT1M90I cells (Figure 2C). To confirm that this USP9X dependency is specific to RIT1-mutant cells, we performed soft agar experiments in erlotinib-resistant KRAS- and EGFR-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells with or without sgUSP9X (Figure S2B). As expected, USP9X knockout did not affect the number of colonies formed by KRASG12V- and EGFRT790M/L858R-mutant cells (Figure 2D). We also assessed colony size and found that USP9X knockout decreased the size of colonies formed by RIT1-mutant—but not KRAS- or EGFR-mutant—cells (Figure S2C). These data demonstrate that USP9X is important for promoting RIT1-driven proliferation and anchorage-independent growth.

Figure 2.

USP9X regulates RIT1-driven proliferation in vitro and in vivo

(A) Proliferation of parental PC9-Cas9 cells and RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells with indicated gene knockouts (sgRIT1 and sgUSP9X) treated with 40 nM erlotinib. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three technical replicates per cell line. Data are representative results from n = 2 independent experiments. p value calculated by multiple unpaired two-tailed t tests.

(B) Representative images of soft agar colony formation assay in parental and RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells with indicated gene knockouts (sgRIT1 and sgUSP9X) treated with DMSO or 500 nM erlotinib. Images captured at 4X after 10 days of growth. Scale bar is 100 μM.

(C) Normalized counts of colonies per well formed by indicated cell lines treated with 500 nM erlotinib. All data were normalized to DMSO control for each cell line, and then normalized to RIT1M90I. Counts taken after 10 days of growth. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three technical replicates per cell line. p values calculated by unpaired two-tailed t tests.

(D) Normalized counts of colonies per well formed by indicated PC9-Cas9 cell lines expressing RIT1M90I, EGFRT790M/L858R, or KRASG12V with or without sgUSP9X. All data were normalized to DMSO control for each cell line, and then normalized to “no sgUSP9X” conditions. Counts taken after 10 days of growth. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three technical replicates per cell line. p values calculated by unpaired two-tailed t tests. Data in (C) and (D) are representative results from n = 2 independent experiments.

(E) Xenograft assay of PC9-Cas9 cells (parental, RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X, and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1) in immunocompromised mice treated with 5 mg/kg osimertinib daily. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of n = 8 tumors per group. p value calculated by unpaired two-tailed t test. # indicates when mice in the RIT1M90I group were euthanized due to tumor ulceration.

(F) Representative immunohistochemistry staining of Ki67-positive images from xenograft tumors in (E). Scale bar is 100 μM.

(G) Quantification of Ki67 positivity. Each point represents a unique tumor; for some conditions, limited tumor tissue was available. p values calculated by unpaired two-tailed t tests.

See also Figure S2.

Given the strong USP9X dependency we observed in RIT1-mutant cells’ response to EGFR inhibition (Figures 1D–1F and S1B–S1G), we asked whether known pro-survival USP9X substrates such as MCL1 also play a role in our experimental setting. We found that USP9X knockout did not affect the abundance of MCL1 (Figure S2D). MCL1 was previously identified as an important USP9X substrate in the context of myeloid malignancies,30 but MCL1 does not appear to be a key substrate in RIT1-mutant lung cancer.

To expand upon our in vitro findings, we explored how USP9X knockout affects in vivo tumor growth. We injected PC9-Cas9 cells (Parental, RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X, and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 cells) into the flanks of nude mice. In mice treated with 5 mg/kg of osimertinib daily, RIT1 + sgUSP9X and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 tumors grew slower than RIT1M90I tumors (Figure 2E). This dosage was chosen based on previous animal studies and to mimic clinically achievable osimertinib dosing.46,47 In mice treated with vehicle, no growth differences were observed across these PC9-Cas9 cell lines (Figure S2E). Ki67 immunohistochemistry staining (Figure 2F) confirmed a slower proliferation rate in RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 tumors compared to RIT1M90I-mutant tumors (Figure 2G). Together, these data support our in vitro findings and suggest that USP9X regulates the oncogenicity of RIT1-mutant cells.

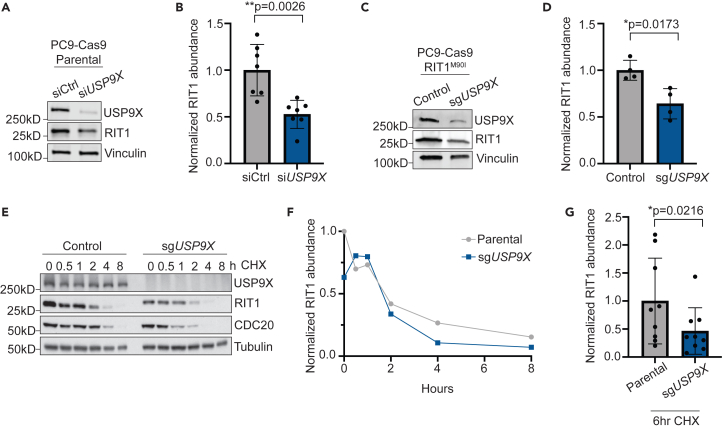

USP9X regulates RIT1 abundance and stability in multiple cell lines

We hypothesized that USP9X knockout might destabilize RIT1, thus explaining USP9X’s ability to counteract RIT1 function observed earlier. Using multiple complementary methods including CRISPR and siRNA, we observed that USP9X knockout or knockdown reduced the abundance of either wild-type RIT1 (Figures 3A and 3B) or RIT1M90I (Figures 1C, 3C, and 3D). To confirm that changes in RIT1 protein abundance were due to USP9X, we re-expressed USP9X in USP9X knockout PC9-Cas9 cells and found that re-expression of USP9X restored RIT1 protein level (Figures S3A and S3B). Importantly, we found no difference in RIT1 mRNA expression in siUSP9X-treated parental and RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells (Figures S3C and S3D), suggesting that differences in RIT1 protein abundance are due to post-transcriptional mechanisms.

Figure 3.

USP9X controls RIT1 abundance and stability in PC9 lung adenocarcinoma cells

(A) Western blot of parental PC9-Cas9 cells treated with indicated siRNAs for 48 h. Vinculin serves as a loading control.

(B) Quantification of western blot band intensity of RIT1 bands in (A). Data shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments with 2–3 biological replicates per condition. p value calculated by paired two-tailed t test.

(C) Western blot of RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells (control) and a CRISPR-engineered clonal USP9X KO (sgUSP9X) cell line. Vinculin serves as a loading control.

(D) Quantification of western blot band intensity of RIT1 bands in (C). Data shown are the mean ± SD of two independent experiments with 2 biological replicates per condition. p value calculated by paired two-tailed t test.

(E) Parental PC9-Cas9 and sgUSP9X cells treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time periods before harvesting for western blot. CDC20 serves as a positive control for USP9X activity. Tubulin serves as a loading control. Data are representative of n = 3 independent experiments.

(F) Analysis of RIT1 protein abundance over time based on RIT1 band intensity in (E).

(G) Comparison of RIT1 protein abundance based on western blot band intensity of aggregated CHX-chase experiments in cells treated with CHX for 6 h. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments with 3 technical replicates per cell line. p value calculated by paired two-tailed t test.

See also Figure S3.

We next determined the stability of RIT1 in the presence and absence of USP9X depletion. Cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit protein translation, and the level of RIT1 was monitored over time by western blot. In USP9X knockout (KO) PC9-Cas9 cells, RIT1 abundance decreased at a faster rate than in parental cells with intact USP9X (Figures 3E–3G). Across CHX experiments, we found that by 6 h of CHX treatment, RIT1 abundance was significantly lower in USP9X KO cells compared to parental (Figure 3G).

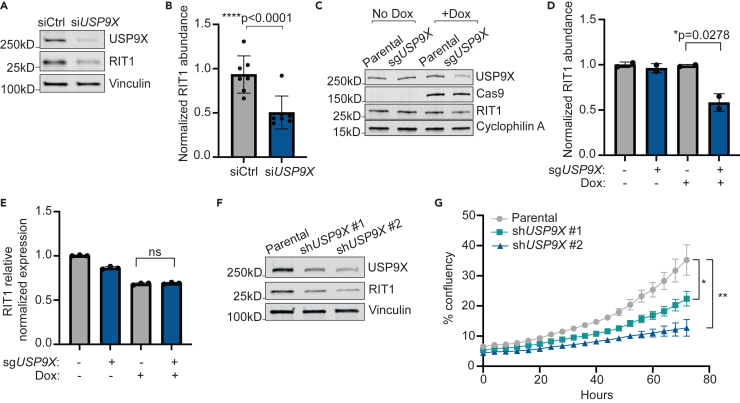

NCI-H2110 cells are a publicly available NSCLC cell line with endogenous RIT1M90I mutation.4 Similar to our results in PC9-Cas9 cells, treatment with siUSP9X in NCI-H2110 cells significantly reduced the abundance of RIT1M90I (Figures 4A and 4B). As orthogonal confirmation, we generated NCI-H2110 cell lines incorporating an inducible (iCas9) system where expression of Cas9 is under control of doxycycline (dox).48 Following dox treatment and Cas9 expression, USP9X knockout significantly decreased RIT1 abundance (Figures 4C and 4D) but not mRNA levels (Figure 4E), indicating that USP9X’s regulation of RIT1 occurs post-transcriptionally and across multiple cell contexts. Together, these data show that USP9X is important for maintaining RIT1 protein abundance and stability in both RIT1WT and RIT1M90I genetic backgrounds.

Figure 4.

USP9X regulates RIT1M90I abundance and proliferation of NCI-H2110 cells

(A) Western blot of NCI-H2110 cells treated with indicated siRNAs for 72 h. Vinculin serves as a loading control.

(B) Quantification of western blot bands based on (A) and additional replicates. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments with 2–3 technical replicates per condition. p value calculated by paired two-tailed t test.

(C) Western blot of NCI-H2110iCas9 cells treated with 1 μg/mL Dox for 7 days to induce Cas9 expression. Cyclophilin A serves as a loading control.

(D) Quantification of Western blot bands in (C). Data shown are the mean ± s.d. of two independent experiments. p value calculated by paired two-tailed t test.

(E) Relative expression of RIT1 as determined by qPCR and ΔΔCt analysis. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three technical replicates per condition. Data are representative results from n = 2 independent experiments. ns = not significant by paired two-tailed t test.

(F) Western blot of NCI-H2110 cells transduced with two unique shRNAs targeting USP9X (shUSP9X #1 and shUSP9X #2). Vinculin serves as a loading control.

(G) Proliferation of parental NCI-H2110 cells and shUSP9X knockdown cell lines over time. p values calculated by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. ∗p = 0.01645; ∗∗p = 0.00245.

Given that USP9X appears to regulate the abundance of RIT1M90I in NCI-H2110 cells, we also sought to assess the phenotypic effects of USP9X loss in this cell line. We previously confirmed that RIT1 knockout abrogated the growth of NCI-H2110 cells,15 indicating that these cells depend on RIT1M90I for survival. To expand upon this observation, we used two unique short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to knockdown USP9X in NCI-H2110 cells (Figure 4F), which resulted in slower proliferation (Figure 4G). Together, these data suggest that USP9X regulates RIT1-driven growth in numerous lung cancer cell line models.

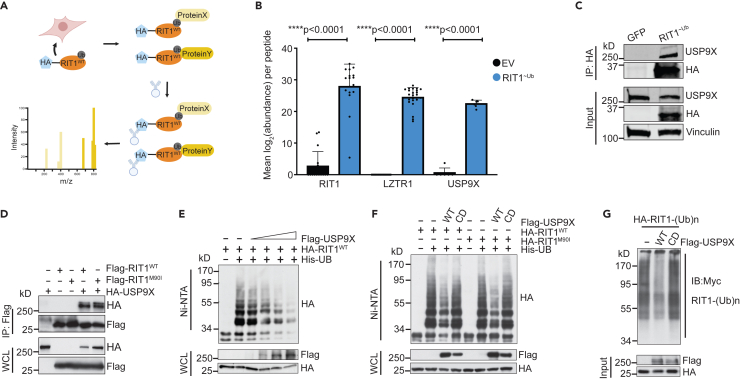

RIT1 ubiquitination is mediated by USP9X’s catalytic activity

To explore USP9X’s regulation of RIT1 in an unbiased fashion and to identify other potential DUBs of RIT1, we fused RIT1 to a ubiquitin molecule through a flexible peptide linker to obtain a constitutively ubiquitinated form of RIT1 that we termed RIT1∼Ub (Figure 5A). This construct acts as a molecular trap, by stabilizing interaction with DUBs, which are unable to cleave the peptide bond.49 Next, we undertook affinity purification-mass spectrometry in HEK293T cells using our RIT1∼Ub mutant. In cells expressing RIT1∼Ub, we found enrichment of RIT1 and LZTR1 peptides compared to control cells transfected with empty vector (Figures 5B and S4A–S4C). We also found a similar enrichment of USP9X peptides (Figures 5B, S4A, and S4D), indicating that USP9X is physically interacting with ubiquitinated RIT1. The interaction of USP9X with RIT1∼Ub was validated by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 4C).

Figure 5.

USP9X binds to and deubiquitinates RIT1

(A) Schematic of affinity purification/mass spectrometry (AP/MS) experiment performed in HEK293T cells transfected with RIT1∼Ub vector. This experiment was designed to identify proteins that bind to ubiquitinated RIT1. Figure created with BioRender.com.

(B) Mean abundance (log2-transformed) of peptides across biological replicates (n = 7 for empty vector/EV and n = 4 for RIT1∼Ub) of AP/MS experiment. p values calculated by paired two-tailed t tests.

(C) Co-immunoprecipitation in HEK293T cells transfected with GFP control or RIT1∼Ub plasmid. Vinculin serves as a loading control. Data shown are representative of n = 2 independent experiments.

(D) Western blot of whole-cell lysates (WCLs) and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates (IP) derived from HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-RIT1WT or FLAG-RIT1M90I together with the HA-USP9X construct. 36 h post-transfection, cells were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 10 h before harvesting. Data shown are representative of n = 4 replicates for RIT1WT and n = 1 replicates for RIT1M90I.

(E) Western blot of WCL and subsequent His-tag pull-down in 6 M guanine-HCl containing buffer derived from HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 16 h to block the proteasome pathway before harvesting. Data shown are representative of n = 3 independent experiments.

(F) Ubiquitination experiment as described in (E) in HEK293T cells transfected with RIT1WT and RIT1M90I, as well as wild-type or catalytically dead (CD) USP9X. Data shown are representative of n = 3 independent experiments.

(G) FLAG-USP9X proteins were immunopurified from HEK293T cells before incubating with ubiquitinated HA-RIT1 proteins for 1 h at room temperature in DUB assay buffer. RIT1 proteins were then enriched and resolved on SDS-PAGE, followed by western blot using Myc antibody to detect Myc-ubiquitin-conjugated RIT1 proteins.

See also Figure S4.

To further assess the physical interaction of USP9X and RIT1, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments in HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged RIT1 (wild-type and RIT1M90I) and HA-tagged USP9X. As expected, we saw evidence for the interaction of RIT1WT and RIT1M90I with USP9X (Figure 5D). To rule out potential confounding factors related to tagged USP9X, we performed this experiment with endogenous USP9X in HEK293T cells and found that endogenous USP9X also interacts with RIT1WT and RIT1M90I (Figure S4E).

To investigate if USP9X is regulating RIT1 ubiquitination, we transiently transfected HA-tagged RIT1 and His-tagged ubiquitin in HEK293T cells. We titrated increasing amounts of FLAG-USP9X and found that ubiquitinated RIT1 decreased in a dose-dependent manner in relation to the amount of USP9X expressed (Figure 5E). Ubiquitin pull-down with either wild-type USP9X or a catalytically dead (CD)35 mutant showed that USP9X reduced ubiquitination of RIT1WT and RIT1M90I in a manner dependent on its catalytic activity (Figure 5F). To validate USP9X as a bona fide DUB for RIT1, we immunopurified FLAG-USP9XWT and FLAG-USP9XCD from HEK293T cells. Purified USP9XWT and USP9XCD proteins were then incubated with ubiquitinated HA-RIT1 in the form of crude lysates to determine the activity of USP9X in removing the polyubiquitin chains assembled on RIT1. After the in vitro reaction, RIT1 proteins were enriched using anti-HA immunoprecipitation followed by western blot to detect ubiquitinated RIT1 proteins. As shown in Figure 5G, USP9XWT, but not the catalytically dead USP9XCD, was capable of effectively eliminating polyubiquitinated RIT1. These results further support the notion that USP9X functions as a DUB for RIT1 to maintain RIT1 protein abundance in cells.

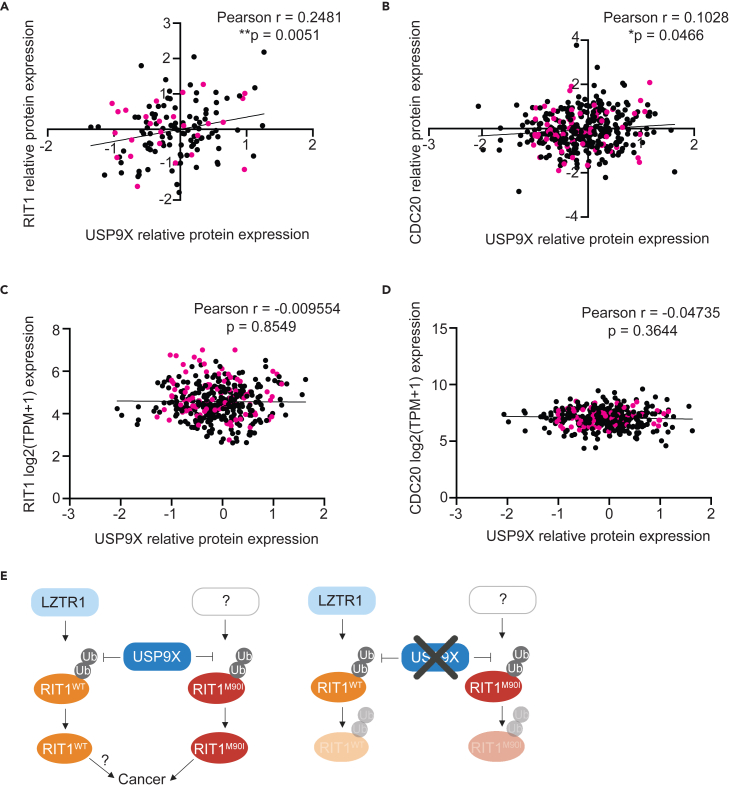

USP9X could be a promising therapeutic target for RIT1-driven diseases

Our findings suggest that USP9X genetic depletion reduces RIT1 abundance and abrogates RIT1-driven oncogenic phenotypes, so USP9X could be a promising drug target in diseases characterized by RIT1 mutations and amplifications, potentially even in diseases beyond LUAD. Analysis of the Cancer Dependency Map and associated proteomics datasets50 revealed a positive correlation between USP9X protein abundance and RIT1 protein abundance (Figure 6A), suggesting that this regulation may extend to multiple cancer types driven by RIT1 alterations. Importantly, this correlation was also seen with CDC20—a known USP9X substrate35 (Figure 6B)—whereas no correlation was observed when comparing USP9X protein abundance to mRNA expression of RIT1 (Figure 6C) or CDC20 (Figure 6D).51 Additionally, analysis of RIT1 copy-number data in lung cancer cell lines revealed that cell lines with RIT1 amplifications (i.e., copy number/CN greater than 2) were more dependent on USP9X (Figure S5). Thus, we propose USP9X inhibition as a strategy to promote RIT1 degradation, which would be detrimental to the growth and proliferation of RIT1-driven tumors (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

USP9X-mediated regulation of RIT1 is relevant across cancer types

(A) Correlation of proteomics data50 from the Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) comparing USP9X (Q93008) and RIT1 (Q92963-3). Pearson r and p values calculated in Prism. Pink dots indicate non-small cell lung cancer cell lines.

(B) Correlation of DepMap proteomics data50 comparing USP9X (Q93008) and CDC20 (Q12834). Pearson r and p values calculated in Prism. Pink dots indicate non-small cell lung cancer cell lines.

(C) Correlation of DepMap mRNA expression data (Expression Public 23Q2)51 for RIT1 and USP9X proteomics data (Q93008).50 Pearson r and p values calculated in Prism. Pink dots indicate non-small cell lung cancer cell lines.

(D) Correlation of DepMap mRNA expression data (Expression Public 23Q2)51 for CDC20 and USP9X proteomics data (Q93008).50 Pearson r and p values calculated in Prism. Pink dots indicate non-small cell lung cancer cell lines.

(E) Proposed model (left) of RIT1 protein regulation. RIT1WT is ubiquitinated by LZTR1, while RIT1M90I is ubiquitinated by a currently unknown E3 ligase. USP9X counteracts the ubiquitination of both wild-type and mutant RIT1. Increased RIT1 abundance and stability are important for RIT1 function and disease progression. The exact biological consequences of RIT1WT amplification have yet to be elucidated. Genetic knockout (right) of USP9X prevents RIT1 deubiquitination, thereby promoting RIT1 degradation and abrogating oncogenic phenotypes. Figure created with BioRender.com.

See also Figure S5.

Together, we suggest a model whereby USP9X positively regulates wild-type and mutant RIT1 (Figure 6E). We predict that this regulation counteracts the effects of LZTR1 on wild-type RIT1 (Figure 6E). The E3 ligase capable of ubiquitinating mutant RIT1 has yet to be identified (Figure 6E). Our findings further build upon the concept that protein abundance of RIT1 is key to its function, and we identify USP9X as a RIT1 regulator.

Discussion

Our group previously performed CRISPR screens to explore RIT1 genetic dependencies15 and identified the deubiquitinase USP9X as a genetic regulator of RIT1 function.15 This finding was particularly interesting given that there is a growing understanding that the protein abundance of RIT1 is important for its function.14,20,21 Mutant forms of RIT1 evade regulation by the CRL3LZTR1 complex, thereby increasing RIT1 protein abundance.14 As such, it is highly probable that the activity of RIT1 is also regulated by DUBs.

Given the function of USP9X as a deubiquitinase, we predicted that USP9X would physically interact with and modify the ubiquitination status of RIT1. Our unbiased affinity purification/mass spectrometry approach revealed that USP9X interacts with mono-ubiquitinated RIT1 (Figures 5A, 5B, S4A, and S4D). As expected, this assay also detected LZTR1—a known RIT1 interactor—thereby increasing the robustness of our findings (Figures 5B, S4A, and S4C). We further validated the physical interaction of USP9X and RIT1 in HEK293T cells (Figures 5D and S4E) and confirmed that the catalytic activity of USP9X regulates the ubiquitination status of RIT1WT and RIT1M90I (Figures 5F and 5G).

Even though mutant RIT1 is the predominant form of RIT1 expressed in RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells, LZTR1 was observed as a cooperating factor in our CRISPR screen.15 In other words, knockout of LZTR1 conferred a growth advantage in RIT1M90I-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells (Figures 1B and S1A; Table S1). This result was somewhat unexpected given that the M90I mutation in RIT1 prevents its interaction with LZTR1.14 However, it is possible that LZTR1 is acting on the endogenous wild-type RIT1 that is also expressed in our engineered RIT1-mutant PC9-Cas9 cells. Our work predicts that both USP9X and LZTR1 are acting on wild-type RIT1, while only USP9X is targeting mutant RIT1 (Figure 6E). The findings presented here support currently known mechanisms of RIT1 regulation,14,20,52,53 while also identifying USP9X as a regulator of both wild-type and mutant RIT1.

The regulatory network involving USP9X, RIT1, and LZTR1 may have co-evolved from flies to mammals. USP9X, first discovered in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) as the fat facets gene, is essential for embryogenesis in flies and mice (Mus musculus).54,55 USP9X can replace fat facets during fly development54 and shares 44% identity and 88% similarity to the fruit fly gene.56 Although USP9X’s catalytic domain is consistent with DUBs in yeast, fat facets is the earliest USP9X ortholog characterized.36 From flies to mammals, USP9X is highly constrained across evolution.57 Orthologs of RIT1 and LZTR1 have been documented in fruit flies but not in Caenorhabditis elegans.52 This contrasts with KRAS, which is highly conserved in yeast.52

Although it was initially characterized in the context of development,58,59 USP9X has been implicated in apoptosis,30,60,61 protein trafficking,33,62,63,64 and polarity.65,66,67 USP9X has been found across a wide range of cellular compartments, including the cytoplasm,64 nucleus,68,69 and mitochondria.30 This diversity highlights that USP9X function is largely dictated by cell type. As a deubiquitinase, USP9X positively maintains the abundance of proteins by removing polyubiquitin chains and preventing proteasomal degradation.30,31,32,33,34,35 USP9X is known to remove both monoubiquitin33,70 and polyubiquitin30,71,72,73 chains. Despite these diverse functions, structural analysis of USP9X suggests that the catalytic domain preferentially binds to and cleaves polyubiquitin chains with K48 and K11 linkages, the two types of linkage that mediate 26S proteasomal degradation.71 LZTR1 promotes K48 polyubiquitination of RIT1WT at K187 and K135.14 Given this, it is possible that USP9X deubiquitinates RIT1WT at these lysine sites. Future work is needed to identify the precise lysines targeted by USP9X and whether this varies between wild-type and mutant forms of RIT1.

In the context of cancer, USP9X has been characterized as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor, depending on its substrates in different cellular contexts.36 Outside of cancer, USP9X mutations underlie X-linked developmental disability (XID).74,75 In the neurons of individuals afflicted with XID, USP9X knockout causes cytoskeletal disruptions that hinder cell growth and migration.74 RIT1 is known to regulate neuronal growth and survival76 and can also affect actin dynamics in fibroblast-like cells via regulation of p21-activated kinase.77 It is possible that USP9X-mediated regulation of RIT1 is important in the context of XID, but this requires further experimentation. These findings, in combination with the observation that USP9X can cleave a diverse range of ubiquitin linkages,71 suggest that cellular context is important for determining key USP9X substrates and potential relevance in disease states.

RIT1 regulation by a DUB could open opportunities to inhibit DUB function and thereby decrease RIT1 protein levels. Attempts have been made to develop small-molecule inhibitors against USP9X. The compound WP1130 has been shown to inhibit USP9X as well as other DUBs including USP5, USP14, and UCH37.78 In cells expressing high abundance of oncoproteins targeted by USP9X, WP1130 treatment abrogates growth and proliferation.79,80 However, the pre-clinical practicality of WP1130 is limited due to low solubility and poor bioavailability in animal models.81,82 The compound G9 is a newer USP9X inhibitor, and it is more soluble and less toxic than WP1130.82 Experiments with G9 have shown promising results for breast cancer, leukemia, and melanoma cells harboring specific mutations.32,83,84,85 Notably, G9 has also been shown to target USP2486 and USP5,87 so it is difficult to directly link the effects of this drug to USP9X inhibition. In 2021, a more specific USP9X inhibitor FT709 was developed with a nanomolar range IC50.88 Unlike WP1130 or G9, FT709 does not target USP24 or USP5.88 It will be intriguing to test if FT709 destabilizes RIT1 in NSCLC cells and whether FT709 sensitizes EGFR TKI-resistant NSCLC cells to EGFR or MAPK inhibition.

In summary, we identified USP9X as a positive regulator of RIT1 function. USP9X deubiquitinates wild-type and mutant RIT1 (Figures 5E–5G), thereby increasing RIT1 abundance and stability. Given that protein abundance of RIT1 is important for its function,14,20,21 USP9X is a key factor in mediating RIT1-driven oncogenic phenotypes. Our work supports previously known mechanisms of RIT1 regulation by LZTR1,14,20,52 and we suggest that USP9X and LZTR1 oppose the action of one another in controlling the ubiquitination status of wild-type RIT1 (Figure 6E). We found that USP9X also targets RIT1M90I (Figures 1C, 3C, 3D, and 4A–4D) and future work is needed to identify other players within the ubiquitin-proteasome system that may be regulating mutant forms of RIT1 (Figure 6E; Table S1). Additionally, more experimentation is required to understand the biological consequences of RIT1WT amplification in disease states. Overall, this work builds upon our knowledge of RIT1 biology, the mechanisms underlying how RIT1 alterations cause disease, and the role of USP9X in lung cancer. These insights can be leveraged in the future to develop robust novel therapies for diseases characterized by RIT1 mutations and amplifications.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we primarily focused on the PC9 cell line/drug resistance system for studying RIT1 dependencies. The PC9 system is analogous to the widely used Ba/F3 system, in which expression of an oncogene confers IL-3-independent growth, but in PC9 cells, expression of an oncogene confers EGFR-independent growth. Even though RIT1 mutations are generally mutually exclusive with EGFR mutations, the PC9 system is based on a human lung cancer cell line and thus represents an improvement in physiological relevance over the mouse-based, non-epithelial Ba/F3 system. In addition, we also studied RIT1 function in NCI-H2110 cells, a lung cancer cell line with endogenous RIT1M90I mutation. However, these findings should be extended to additional cell models of RIT1 function in the future, and ideally also to patient-derived xenograft models of RIT1-mutant lung cancer, should they become available.

We demonstrated that USP9X deubiquitinates RIT1M90I, but we have yet to identify the E3 ubiquitin ligase(s) that is promoting its ubiquitination and degradation. In our CRISPR screen, we identified 22 E3 ligases that were positively selected (Table S1), meaning that individual genetic knockout of these ligases conferred a growth advantage in RIT1-mutant PC9 cells. Therefore, these genes are candidate E3 ligases that may target RIT1M90I independently or potentially cooperate with CRL3LZTR1 to ubiquitinate RIT1. Systematic characterization and investigation of these 22 E3 ligases is required to further elucidate the protein-level regulation of RIT1M90I.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| β-Actin | Cell Signaling Technology | 4970; RRID: AB_2223172 |

| USP9X | Proteintech | 55054-1-AP; RRID: AB_10792932 |

| RIT1 | Abcam | Ab53720; RRID: AB_882379 |

| Vinculin | Sigma-Aldrich | V9264; RRID: AB_10603627 |

| Cyclophilin A | Bio-Rad | VMA00535; RRID: AB_3101732 |

| Cas9 | Cell Signaling Technology | 14697; RRID: AB_2750916 |

| CDC20 | Santa Cruz | 13162; RRID: AB_628089 |

| Tubulin | Sigma-Aldrich | T5168; RRID: AB_477579 |

| Flag | Sigma-Aldrich | F1804; RRID: AB_262044 |

| HA | Biolegend | 901503; RRID: AB_2565005 |

| MCL1 | Cell Signaling Technology | 94296; RRID: AB_2722740 |

| EGFR | Cell Signaling Technology | 2232; RRID: AB_331707 |

| pEGFR | Cell Signaling Technology | 2236; RRID: AB_331792 |

| KRAS | Sigma-Aldrich | WH0003845M1; RRID: AB_1842235 |

| pAKT | Cell Signaling Technology | 9271; RRID: AB_329825 |

| Rabbit IGG antibody | R&D Systems | AB-105-C; RRID: AB_354266 |

| IRDye secondary antibodies | LiCOR | 922-322/680 |

| MYC | Cell Signaling Technology | 2272; RRID: AB_10692100 |

| Ki67 clone D385 | Cell Signaling Technology | 12202; RRID: AB_2620142 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| One Shot TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli | ThermoFisher Scientific | C404010 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Erlotinib-OSI-774 | SelleckChem | S1023 |

| Osimertinib-AZD92921 | SelleckChem | S7297 |

| MG132 | Selleck Chemicals | Cat. No. S2619, CAS No. 1211877-36-9 |

| Cycloheximide | Tocris Bioscience | Cat. No. 0970, CAS No. 66-81-9 |

| Complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets | ThermoFisher Scientific | A32955 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor tablets | ThermoFisher Scientific | A32957 |

| Trypsin | Corning | MT 25-053-CI |

| jetPRIME Reagent | Polyplus | 101000027 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent | ThermoFisher Scientific | L3000008 |

| TransIT-LT1 | Mirus Bio | MIR2304 |

| RNAiMAX | ThermoFisher Scientific | 13778075 |

| ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel | Millipore Sigma | A2220 |

| EZview Red Anti-HA Affinity Gel | Millipore Sigma | E6779 |

| Protein A agarose beads | Cell Signaling | 9863S |

| Protein G Sepharose beads | GE Healthcare | 17-0618-01 |

| DMSO | Sigma-Aldrich | D2650 |

| PEG300 | SelleckChem | S6704 |

| Tween80 | SelleckChem | S6702 |

| Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 | Leica | AR9640 |

| Mixed Refine DAB | Leica | DS9800 |

| Refine Hematoxylin | Leica | DS9800 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | 23225 |

| Bio-Rad Protein Assay Reagent | Biorad | 5000001 |

| CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay | Promega | G7572 |

| Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX | Invitrogen | CMAX00008 |

| SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System | Invitrogen | 18091050 |

| Plasmid Plus Midi kit | Qiagen | 12941 |

| Trans-blot Turbo Transfer System | Biorad | 1704274 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: RIT1 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Hs00608424 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: 18S | ThermoFisher Scientific | Hs99999901_s1 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Proteomic data | ProteomeXchange Consortium PRIDE84 | ProteomeXchange (PRIDE): PXD047228 |

| CRISPR screen | Published15 | |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| PC9 | Dr. Matthew Meyerson (Broad Institute) | |

| NIH3T3 | ATCC | CRL-1658 |

| NCI-H2110 | ATCC | CRL-5924 |

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Nude Nu/J mice (females); 6-12 weeks old | Jackson Laboratory | # 002019 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| sgUSP9X: TCATACTATACTCATCGACA | Synthego | |

| siUSP9X: Sense: 5' A.C.A.C.G.A.U.G.C.U.U.U.A.G.A.A.U.U.U.U.U 3' Antisense: 5' 5'-P.A.A.A.U.U.C.U.A.A.A.G.C.A.U.C.G.U.G.U.U.U 3' |

Dharmacon | CTM-511558 |

| siCtrl: ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting siRNA #1 | Dharmacon | D-001810-01-05 |

| shUSP9X | MISSION (Millipore Sigma) | TRCN0000007361 TRCN0000007362 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pEGFP-N1 | Clontech | 6085-1 |

| pCMV-3xFLAG-USP9XWT | Akopian et al.89 | |

| pcDNA5-FLAG-USP9X (WT and CD) | Skowyra et al.35 | |

| pcDNA3-8xHis-ubiquitin | ||

| p3xFLAG-RIT1 (WT and M90I) | Berger et al.4 | |

| pcDNA3-HA-RIT1 (WT and M90I) | ||

| pcDNA3-HA-USP9X | ||

| pDEST27-GST-RIT1 (WT and M90I) | Castel et al.14 | |

| pCGS1-HA-RIT1-Ub (RIT1∼Ub) | Dr. Pau Castel | |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism | Graphpad | v10.1.0 |

| ImageJ | NIH | 1.53t |

| ImageStudio | Licor | v5.2.5 |

| Licor Acquisition Software | Licor | v1.1.0.61 |

| IncuCyte 2023A | IncuCyte | 2023A Rev1 |

| HistoQuest | TissueGnostics | v7.1.1.119 |

| Other | ||

| DMEM | Genesee Scientific | 25-500 |

| RPMI 1640 | Gibco | 11875119 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Peak Serum | PS-FB2 |

| 96-well cell culture plate | Falcon | 353075 |

| 6-well cell culture plate | CytoOne | CC7682-7506 |

| 6-well non-treated plate | ThermoFisher Scientific | 150239 |

| 10cm cell culture dish | ThermoFisher Scientific | 12556002 |

| White-bottom 384-well cell culture plate | Falcon | 08-772-116 |

| PBS | Corning | 21-040-CV |

| Tris pH 7.5 | Invitrogen | 15-567-027 |

| Tris pH 8.0 | Lonza | 51238 |

| EDTA 0.5 M | Hoefer | GR123-100 |

| NaCl 5 M | Growcells | MRGF-1207 |

| IGEPAL CA-630 | Sigma-Aldrich | 18896 |

| NP-40 | GBiosciences | 072N-A |

| Glycerol | ThermoFisher Scientific | 3563501000M |

| Intercept PBS Blocking Buffer | LiCOR | 927-70003 |

| Select Agar | Sigma-Aldrich | A5054 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Alice Berger (ahberger@fredhutch.org).

Materials availability

Reagents used in this study are commercially available or available upon request to the lead author.

Data and code availability

-

•

The mass spectrometry data are publicly available at the Proteomics IDEntification database (PRIDE)90 repository with the dataset identifier PXD047228. CRISPR screening data was re-analyzed from data in a previously published manuscript.15

-

•

This study did not generate custom code. The custom macro for image analysis is available upon request.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell lines

PC9 cells were a gift from Dr. Matthew Meyerson (Broad Institute). PC9-Cas9 cells were generated as previously described.15 NIH3T3, NCI-H2110, and HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1658, CRL-5924, and CRL-3216, respectively). PC9-Cas9 and NCI-H2110 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). NIH3T3 and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Genesee Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS (Peak Serum, PS-FB2). All cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 and confirmed mycoplasma-free.

Method details

Cell line generation

RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X, and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1 cells were generated as previously described.15 PC9-Cas9 + sgUSP9X cells were generated by co-transfecting with lipofectamine CRISPR max (Life Technologies) and a synthetic guide RNA: TCATACTATACTCATCGACA.

Single cells were plated in a 96-well cell culture plate (Falcon), and clones were expanded and validated by Western blot and Sanger sequencing. H2110iCas9 cells were generated as previously described.15 PC9-Cas9 KRASG12V- and EGFRT790M/L858R-mutant cells harboring sgNTC and sgUSP9X were generated by transduction with pXPR003 and sgNTC or sgUSP9X guide RNAs. Lentivirus was generated as previously described.15 Stable cell lines were generated by lentiviral transduction in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene followed by selection with 1 μg/mL puromycin for 72 hours.

Transformation and plasmid preparation

To propagate plasmids, One Shot TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli (ThermoFisher Scientific) were transformed with 1 μg of plasmid. Bacteria were propagated and plasmid was isolated using the Plasmid Plus Midi kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

For the USP9X re-expression experiment, 2x105 PC9-Cas9 cells (parental and sgUSP9X) were plated into individual wells of a 6-well plate (CytoOne). The next day, cells were transfected with 2.5 μg GFP control plasmid or pCMV-3xFLAG-USP9XWT vector using the TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio). After 48 hours, GFP expression was confirmed by direct fluorescent expression using the EVOS FL digital inverted microscope Cell Imaging System v1.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before lysate collection.

siRNA treatment

Lyophilized siRNAs were obtained from Dharmacon and resuspended to make 100 μM stock solutions. For siCtrl conditions, ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting siRNA #1 was used. The sequence for siUSP9X is as follows:

Sense: 5’ ACACGAUGCUUUAGAAUUUUU 3’.

Antisense: 5’ PAAAUUCUAAAGCAUCGUGUUU 3’.

Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

shRNAs

USP9X shRNAs were obtained from MISSION (Millipore Sigma). Two unique USP9X-targeting shRNAs were ordered as glycerol stocks in the pLKO.1 backbone:

| Reference number | Target sequence |

|---|---|

| TRCN0000007361 | GAGAGTTTATTCACTGTCTTA |

| TRCN0000007362 | CGATTCTTCAAAGCTGTGAAT |

Plasmids were propagated as described above, and shRNAs were packaged into lentivirus. Stable cell lines were generated by lentiviral transduction in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene followed by selection with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 72 hours.

Dose response curves

For drug treatment experiments in PC9-Cas9 cells, cells were plated in white-bottom 384-well plates (Falcon) at a density of 400 cells per well in 40 μL of media. For siRNA experiments, 1x106 cells were plated in a 10 cm cell culture dish (ThermoFisher Scientific). 24 hours later, cells were transfected with 120 pmol of siCtrl or siUSP9X (Dharmacon) following the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection procedure (Life Technologies). 48 hours later, cells were plated in 384-well plates as described above. 24 hours after cell plating, a serial dilution of erlotinib or osimertinib was performed using a D300e dispenser (Tecan). 72 hours post-treatment, 10 μL of CellTiterGlo reagent (Promega) was added to each well and luminescence was quantified on an Envision MultiLabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer). The viable cell fraction was calculated by comparing the viability of drug-treated cells to the average viability of cells treated with DMSO only (Sigma-Aldrich), normalized by fluid volume. Curve fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism (v10.1.0). Inhibitors were obtained from SelleckChem: Erlotinib-OSI-774 (S1023) and Osimertinib-AZD92921 (S7297). Area-under-the curve (AUC) analyses were performed in Prism 10 (v10.0.3).

Cell lysis and immunoblotting

Whole-cell extracts for immunoblotting were prepared by washing cells with cold PBS (Corning) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher) on ice and then scraping cells in RTK lysis buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 137 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 10% Glycerol, and ddH20] supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific) and protease inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific, EDTA-free). Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 min. Following centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 20 min), lysates were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) in a 96-well plate and read on an Accuris Smartreader 96 (MR9600). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes using the Trans-blot Turbo Transfer System (BioRad). Membranes were blocked in Intercept PBS blocking buffer (LiCOR) for 1 h at room temperature followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. IRDye (LiCOR) secondary antibodies were used for detection and were imaged on the LiCOR Odyssey DLx. Images were acquired using the Licor Acquisition Software (v1.1.0.61) from LiCOR Biosciences. Loading control and experimental proteins were probed on the same membrane unless indicated otherwise. For clarity, loading control is shown below experimental conditions in all panels regardless of the relative molecular weights of the experimental protein(s). Quantification and normalization of Western blot band intensity was performed following protocols from Invitrogen (iBright Imaging Systems).

For immunoprecipitation experiments in Figures 5D–5F: cells were lysed in EBC buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40/IGEPAL CA-630) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific) and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). To prepare the Whole Cell Lysates (WCL), 3 × SDS sample buffer was directly added to the cell lysates and sonicated before being resolved on SDS-PAGE and subsequently immunoblotted with primary antibodies. The protein concentrations of the lysates were measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent on a Bio-Rad Model 680 Microplate Reader. For immunoprecipitation, 1 mg lysates were incubated with the appropriate agarose-conjugated primary antibody for 3-4 h at 4°C or with unconjugated antibody (1-2 mg) overnight at 4°C followed by 1 h incubation with Protein G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Immuno-complexes were washed four times with NETN buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% NP-40) before being resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies.

Primary antibodies used for immunoblotting: β-Actin 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4970), USP9X 1:500 (Proteintech, 55054-1-AP), RIT1 1:1000 (Abcam, Ab53720), Vinculin 1:1500 (Sigma-Aldrich, V9264), Cyclophilin A 1:1000 (Bio-Rad, VMA00535), Cas9 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, 14697), CDC20 1:2000 (Santa Cruz, 13162), Tubulin 1:2000 (Sigma-Aldrich, T5168), Flag 1:2000 (Sigma-Aldrich, F1804), HA 1:2000 (Biolegend, 901503), MCL1 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, 94296), EGFR 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2232), pEGFR tyr1068 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2236), KRAS 1:500 (Sigma-Aldrich, WH0003845M1), pAKT ser473 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology 9271), MYC 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology 2272).

Proliferation assay

PC9-Cas9 cells (Parental, RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X, and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1) were seeded in triplicate in 6-well tissue culture-treated dishes (CytoOne) at a density of 1x105 cells per well. Cells were counted and passaged every 2-4 days and replated at a density of 1x105 cells per well. Cumulative population doublings were calculated in excel, and statistical analyses were performed in Prism (v10.1.0).

For proliferation experiments in NCI-H2110 cells, 1.5x105 cells were plated in triplicate wells of a 6-well plate (CytoOne). The next day, plates were loaded onto the IncuCyte S3 and images were captured every 4 hours using a Basler Ace 1920-155uM – CMOS camera with the 4X objective. Percent confluency was calculated in the IncuCyte 2023A Rev1 software.

Soft agar assays

For soft agar colony formation assays, 4x105 PC9-Cas9 cells (Parental, RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X, and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1) were suspended in 1.3 mL media and 2.7 mL 0.5% select agar (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI+10% FBS. 1 mL of this cell suspension was plated into 3 wells on a bottom layer of 0.5% select agar in RPMI+10% FBS in 6-well non-tissue culture treated dishes (Thermo Scientific). For soft agar inhibitor experiments, erlotinib was suspended in the top agar solution at a final concentration of 500 nM. DMSO control conditions were prepared to normalize by DMSO volume. After 10 days of growth, brightfield images were acquired on an ImageExpress (Molecular Devices) microscope using a 4x/0.2 NA objective. Fields of view were tiled in a 9x9 grid to cover the entire well with no overlap. A z-stack with 1125 μm range and 25 μm step size were acquired for each field of view and saved as a 2D minimum projection. All images were analyzed in ImageJ (1.53t) using a custom macro (available upon request). Images were excluded if they were obstructed by the 6-well plate and/or if the agar contained bubbles or other abnormalities.

In vivo xenograft studies and ethical approval

All procedures and animal protocols were approved by the IACUC committee at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (FHCC) on protocol “Berger 50967” and performed in the AALAC accredited FHCC vivarium. Mice were housed in HEPA ventilated cages on a 12-hour light-dark cycle. In vivo work was performed by trained technicians.

Day 0: PC9-Cas9 cells (Parental, RIT1M90I, RIT1M90I + sgUSP9X and RIT1M90I + sgRIT1) were prepared so that each 200 μL injection contained 2 million cells. Cells were implanted subcutaneously on both flanks of immune compromised Nude mice (4 mice per condition, Female NUDE mice, 6-12 weeks old, JAX part # 002019) to generate tumors. Mice were identified using unique ear notches.

Day 1: Mice were enrolled into treatment arms (16 total mice for vehicle control and 16 total mice for 5 mg/kg simertinib) and were treated orally on weekdays for up to 60 days. Osimertinib solution was prepared weekly in 5%DMSO + 40%PEG300 (SelleckChem) + 5%Tween80 (SelleckChem) + 50%ddH2O. The vehicle and drug treatments were administered into the stomach via sterile flexible gavage tubes attached to a syringe.

Tumors were measured 2-3x per week for the duration of the study using Caliper (PMC use NEIKO 01407A electronic digital caliper). Measurements were collected manually by palpating the implant site and determining tumor boundaries. Tumor length and width were recorded into an excel sheet, and volume [L∗(Wˆ2)/2] was tracked. Mice were weighed weekly for health monitoring and for dose calculations. At 60 day endpoint, or earlier if IACUC early endpoint criteria were met, the mice were humanely sacrificed for collection of tumor tissue. 3 tumor fragments were snap frozen and remaining tissue was preserved in formalin for FFPE.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections were cut at 4 microns, air dried at room temperature overnight, and baked at 60°C for 1 hour. Slides were stained on a Leica BOND Rx autostainer (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) using Leica Bond reagents. Epitope retrieval was performed at 100°C for 20 minutes with Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 (Leica AR9640). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% H2O2 for 5 min followed by protein blocking with TCT buffer (0.05M Tris, 0.15M NaCl, 0.25% Casein, 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.05% Proclin 300 at pH 7.6 +/- 0.1) for 10 min. Rabbit anti-Ki67 clone D385 (Cell Signaling 12202) at a dilution of 1:2000 was incubated for one hour and Refine Rabbit polymer HRP was applied for 12 minutes, followed by Mixed Refine DAB (Leica DS9800) for 10 min and counterstained with Refine Hematoxylin (Leica DS9800) for 4 min after which slides were dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped with permanent mounting media.

Slides were imaged using a 10×/0.3 objective on a Zeiss Axio Imager Z2 microscope as part of a TissueFAXS system (TissueGnostics; Vienna, Austria). Images were analyzed in HistoQuest (v7.1.1.119).

Cycloheximide-chase

Parental PC9-Cas9 and sgUSP9X cells treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time periods before harvesting protein for Western blot. Cycloheximide (Tocris Bioscience, Cat. No. 0970, CAS No. 66-81-9), was dissolved in DMSO as 100 mg/ml stock solution freshly before each use.

RT-qPCR

For RT-qPCR experiments in siRNA-treated PC9-Cas9 cells (parental and RIT1M90I-mutant), 150,000 cells were plated in individual wells of a 6-well plate (CytoOne). The next day, siRNA treatment was performed as described above. 48 hours post-transfection, each well was washed with 1 mL cold PBS, and 700uL of Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) was added to each well. After 1 minute, the suspension was collected, and RNA was isolated using the Direct-Zol RNA Miniprep Plus (Zymo Research). Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg RNA and the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using TaqMan gene expression assays (ThermoFisher Scientific): RIT1 (assay Hs00608424_m1) and 18S (assay Hs99999901_s1). For RIT1 reactions, 30 ng of cDNA was used. For 18S reactions, 5 ng of cDNA was used.

Reactions were run on the BioRad CFX384 Real-Time system

For the H2110iCas9 RT-qPCR experiments, total RNA was extracted from two biological replicates of parental H2110iCas9 cells and H2110iCas9 + sgUSP9X cells treated with 1 ug/uL doxycycline for 7 days. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg RNA and the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). 20 ng of cDNA was used for each RT-PCR reaction. cDNA was amplified using TaqMan gene expression assays (ThermoFisher Scientific): RIT1 (assay Hs00608424_m1) and 18S (assay Hs99999901_s1). Reactions were run on the BioRad CFX384 Real-Time system. Expression was normalized to 18S within each sample in the same experiment, and relative expression was quantified using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Co-immunoprecipitation

For RIT1∼Ub pulldown, 2 million HEK293T cells were plated in 10 cm cell culture dishes (ThermoFisher Scientific). The next day, cells were transfected with 10 μg of indicated plasmids (RIT1∼Ub refers to transfection with the pCGS1-HA-RIT1-Ub vector) and jetPRIME reagent (Polyplus), following the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 hours post-transfection, HA pulldown was performed using EZview Red Anti-HA Affinity Gel (Millipore Sigma). In brief, cells were washed with cold PBS supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were scraped in 1 mL NP40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 10% glycerol, 10mM Tris (pH 8.0), and ddH20) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific). 50 μL of lysate was reserved for the Whole Cell Lysate. 30 μL of pre-washed EZview beads were added per condition, and samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with shaking. Samples were washed 3X and then prepared for SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described above. For RIT1∼Ub pull downs used for affinity purification mass spectrometry, a similar protocol was used with few substitutions. First, the number of cells was scaled up to 15 million in two 15 cm plates and magnetic anti-HA beads (ThermoFisher Scientific) were used instead. After washing beads with lysis buffer, two additional washes were performed using PBS to remove residual detergent present in the beads. For each experimental condition, four biological replicates were used.

For IP:RIT1 experiments with endogenous USP9X, 3 million HEK393T cells were plated in 10 cm cell culture dishes (ThermoFisher Scientific). The next day, cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of GST-tagged RIT1 plasmids or GFP control plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 hours later, cells were washed with cold PBS supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were scraped in 700 μL lysis buffer (50mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1% IGEPAL-CA-630) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific). Protein lysates were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), and 1 mg of protein was used for each IP condition. 50 μg of protein was set aside for the Whole Cell Lysate. For IP conditions, each lysate was pre-cleared with 20 μL of pre-washed Protein A agarose beads (Cell Signaling 9863S). Next, 1 μg of RIT1 antibody (Abcam Ab53720) or 1 μg of control rabbit IgG antibody (R&D Systems AB-105-C) was added, and samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with shaking. 20 μL of beads were added to each tube, and samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with shaking. The next day, samples were washed 3X and prepared for SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described above.

In vivo ubiquitination assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with RIT1, USP9X, and His-ubiquitin constructs. 36 hours after transfection, 10 μM MG132 was added to block proteasome degradation, and cells were harvested in denatured buffer (6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mM imidazole), followed by Ni-NTA (Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid) purification and immunoblot analysis. MG-132 (Selleck Chemicals, Cat. No. S2619, CAS No. 1211877-36-9), was dissolved in DMSO as a 10 mM stock solution and stored in -20°C.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

USP9X proteins were immunopurified from HEK293T cells transfected with pcDNA5-Flag-USP9X construct. Anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (Millipore Sigma) was used to purify USP9X. The proteins were kept on the beads in protein assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT). To prepare poly-ubiquitinated RIT1, HA-RIT1 and Myc-ubiquitin were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. The crude lysate was prepared using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 10 mM DTT). USP9X proteins were then incubated with ubiquitinated RIT1-containing lysates at room temperature for 1 h. RIT1 proteins were further enriched using Anti-HA Affinity Gel (Millipore Sigma) and ubiquitinated RIT1 was visualized by western blot using Myc antibody.

Affinity purification/mass spectrometry

On-bead trypsin digests were performed as previously described,14 and digested tryptic peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the same configuration and settings as previously reported.91 Acquired MS data were analyzed using a workflow previously described.91,92 Briefly, spectra were searched in Protein Prospector (version 6.2.493) against human proteome (SwissProt database downloaded on 01/18/2021) and decoy database of corresponding randomly shuffled peptides. Search engine parameters were as follows: “ESI-Q-high-res” for the instrument, trypsin as the protease, up to 2 missed cleavages allowed, Carbamidomethyl-C as constant modification, default variable modifications, up to 3 modifications per peptide allowed, 15 ppm precursor mass tolerance, and 25 ppm tolerance for fragment ions. The false discovery rate was set to <1% for peptides, and at least 3 unique peptides per protein were required. Protein Prospector search results formatted as BiblioSpec spectral library were imported into Skyline (v21) to quantify peptide and protein abundances using MS1 extracted chromatograms.94 Statistical analysis of observed protein abundances was performed using MSstats package integrated in Skyline.95

Abundance per peptide represents the log2-abundance of the peak intensity (AUC) from mass-spectrometry for each peptide. Mean per-peptide abundance is the average enrichment of abundance for each peptide across replicates. Mean of mean-peptide abundance was calculated as the average of mean-peptide abundance for all peptides for the protein across repeats. Mean of mean-peptide abundance was used to generate the heatmap (Figure S4A). Heatmap shows a subset of those proteins with at least a 5-fold enrichment over empty vector (EV).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. unless otherwise noted. Exact numbers of biological and technical replicates for each experiment are reported in the Figure Legends. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant based on the appropriate statistical test for the experiment in question. For all data, ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01, ∗∗∗p<0.001, ∗∗∗∗p<0.0001. Data were analyzed using Prism Software 10.0 (GraphPad).

CRISPR data analysis

CRISPR scores were calculated as previously described.15 In brief, all data were scaled so that the median of non-essential genes (based on previously published lists in DepMap96) is 0 and the median of essential genes is -1. CRISPR scores were defined as this scaled, normalized log-fold-change data. All data from this CRISPR screen are available within the main figures and supplemental information from the associated published manuscript.15

DepMap analyses

For correlation analyses, data were explored in the Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) online portal (https://depmap.org/portal/). Proteomics data were captured from50 and available within DepMap. RIT1, CDC20, and USP9X expression were evaluated in the Expression Public 23Q2 datasets and previously published.51 Correlation and statistical tests were performed in Prism (v10.1.0). For the RIT1 copy number analysis, all lung cancer cell lines in DepMap were selected and separated based on normal copy number (CN = 1) and high copy number (CN > 1). Copy Number data were from the Copy Number (Absolute) data set in DepMap. USP9X CRISPR scores were obtained from DepMap Public 23Q4+ Score, Chronos.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through NCI F31CA271637 to A.K.R., NCI R37CA252050 and a Pardee Foundation award to A.H.B., R01CA255398 and ACS RSG-19-226-01-TBE to L.W., ACS TLC-21-009-01-TLC to A.H.B. and L.W., and NCI R01CA279171 to P.C. This research was supported by the Cellular Imaging Shared Resource RRID:SCR_022609 and by the Preclinical Modeling Shared Resource, RRID:SCR_022617 of the Fred Hutch/University of Washington/Seattle Children’s Cancer Consortium (P30 CA015704). Immunohistochemistry was performed by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Experimental Histopathology shared resource (P30 CA015704). We would like to thank Sarah Masunaga and Umut Demirkol of the Preclinical Modeling Shared Resource for their assistance with the xenograft experiments. We would also like to thank Dr. Lena Schroeder of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Cellular Imaging Shared Resource for assistance with microscopy and image analysis. The wild-type and catalytically dead USP9X pcDNA5 constructs used in ubiquitination experiments were a kind gift from Dr. Lindsey Allan at the University of Dundee and were previously published.35 The pCMV-3xFLAG-USP9XWT construct was a kind gift from Dr. Michael Rape at the University of California, Berkeley, and was previously published.89

Author contributions

A.K.R., L.W., and A.H.B. conceived and designed the study. A.K.R., M.G., S.P.M., and A.S. performed the cellular and biochemistry experiments. E.C. led the xenograft modeling team and performed the PC9-Cas9 in vivo experiments. C.R. assisted with conceiving and planning for the xenograft experiments. A.V. generated RIT1-mutant PC9-Cas9 knockout cell lines. S.M. analyzed the AP/MS data and generated associated plots. P.C. contributed reagents. A.U. and P.C. performed AP/MS experiments and provided the associated methods. A.K.R. wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed by all co-authors.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 14, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.110499.

Contributor Information

Lixin Wan, Email: lixin.wan@moffitt.org.

Alice H. Berger, Email: ahberger@fredhutch.org.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2023;73:17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemjabbar-Alaoui H., Hassan O.U., Yang Y.-W., Buchanan P. Lung cancer: Biology and treatment options. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1856:189–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harada G., Yang S.-R., Cocco E., Drilon A. Rare molecular subtypes of lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023;20:229–249. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger A.H., Imielinski M., Duke F., Wala J., Kaplan N., Shi G.-X., Andres D.A., Meyerson M. Oncogenic RIT1 mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2014;33:4418–4423. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo A., Holmes K., Kamlapurkar S., Mundt F., Moorthi S., Fung I., Fereshetian S., Watson J., Carr S.A., Mertins P., Berger A.H. Multiomic characterization of oncogenic signaling mediated by wild-type and mutant RIT1. Sci. Signal. 2021;14 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abc4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez-Seguí I., Makishima H., Jerez A., Yoshida K., Przychodzen B., Miyano S., Shiraishi Y., Husseinzadeh H.D., Guinta K., Clemente M., et al. Novel recurrent mutations in the RAS-like GTP-binding gene RIT1 in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia. 2013;27:1943–1946. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherniack A.D., Shen H., Walter V., Stewart C., Murray B.A., Bowlby R., Hu X., Ling S., Soslow R.A., Broaddus R.R., et al. Integrated Molecular Characterization of Uterine Carcinosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L., Xi S., Zhou Z., Zhang F., Hu P., Cui Y., Wu S., Wang Y., Wu S., Wang Y., et al. Elevated expression of RIT1 hyperactivates RAS/MAPK signal and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to combined treatment with sorafenib and AKT inhibitor. Oncogene. 2022;41:732–744. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki Y., Niihori T., Banjo T., Okamoto N., Mizuno S., Kurosawa K., Ogata T., Takada F., Yano M., Ando T., et al. Gain-of-function mutations in RIT1 cause Noonan syndrome, a RAS/MAPK pathway syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee C.H., Della N.G., Chew C.E., Zack D.J. Rin, a neuron-specific and calmodulin-binding small G-protein, and Rit define a novel subfamily of ras proteins. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6784–6794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06784.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao H., Kadono-Okuda K., Finlin B.S., Andres D.A. Biochemical characterization of the Ras-related GTPases Rit and Rin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;371:207–219. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simanshu D.K., Nissley D.V., McCormick F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell. 2017;170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castel P., Cheng A., Cuevas-Navarro A., Everman D.B., Papageorge A.G., Simanshu D.K., Tankka A., Galeas J., Urisman A., McCormick F. RIT1 oncoproteins escape LZTR1-mediated proteolysis. Science. 2019;363:1226–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.aav1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vichas A., Riley A.K., Nkinsi N.T., Kamlapurkar S., Parrish P.C.R., Lo A., Duke F., Chen J., Fung I., Watson J., et al. Integrative oncogene-dependency mapping identifies RIT1 vulnerabilities and synergies in lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4789. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trahey M., McCormick F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science. 1987;238:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.2821624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto G.L., Aguena M., Gos M., Hung C., Pilch J., Fahiminiya S., Abramowicz A., Cristian I., Buscarilli M., Naslavsky M.S., et al. Rare variants in SOS2 and LZTR1 are associated with Noonan syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2015;52:413–421. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston J.J., van der Smagt J.J., Rosenfeld J.A., Pagnamenta A.T., Alswaid A., Baker E.H., Blair E., Borck G., Brinkmann J., Craigen W., et al. Autosomal recessive Noonan syndrome associated with biallelic LZTR1 variants. Genet. Med. 2018;20:1175–1185. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pich O., Reyes-Salazar I., Gonzalez-Perez A., Lopez-Bigas N. Discovering the drivers of clonal hematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:4267. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31878-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S., Vedula R.S., Cuevas-Navarro A., Lu B., Hogg S.J., Wang E., Benbarche S., Knorr K., Kim W.J., Stanley R.F., et al. Impaired Proteolysis of Noncanonical RAS Proteins Drives Clonal Hematopoietic Transformation. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:2434–2453. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuevas-Navarro A., Wagner M., Van R., Swain M., Mo S., Columbus J., Allison M.R., Cheng A., Messing S., Turbyville T.J., et al. RAS-dependent RAF-MAPK hyperactivation by pathogenic RIT1 is a therapeutic target in Noonan syndrome-associated cardiac hypertrophy. Sci. Adv. 2023;9 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adf4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger A.H., Brooks A.N., Wu X., Shrestha Y., Chouinard C., Piccioni F., Bagul M., Kamburov A., Imielinski M., Hogstrom L., et al. High-throughput Phenotyping of Lung Cancer Somatic Mutations. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noro R., Gemma A., Kosaihira S., Kokubo Y., Chen M., Seike M., Kataoka K., Matsuda K., Okano T., Minegishi Y., et al. Gefitinib (IRESSA) sensitive lung cancer cell lines show phosphorylation of Akt without ligand stimulation. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:277. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]