Abstract

To assess the biochemical, mechanical and structural characteristics of retained dentin after applying three novel bromelain-contained chemomechanical caries removal (CMCR) formulations in comparison to the conventional excavation methods (hand and rotary) and a commercial papain-contained gel (Brix 3000). Seventy-two extracted permanent molars with natural occlusal carious lesions (score > 4 following the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS-II)) were randomly allocated into six groups (n = 12) according to the excavation methods: hand excavation, rotary excavation, Brix 3000, bromelain-contained gel (F1), bromelain-chloramine-T (F2), and bromelain-chlorhexidine gel (F3). The superficial and deeper layers of residual dentin were examined by Raman microspectroscopy and Vickers microhardness, while the surface morphology was assessed by the scanning electron microscope (SEM). A multivariate analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test (p > 0.05) was performed for data analysis. The novel formulations showed an ability to preserve the partially demineralized dentin that showed a reduced phosphate content with a higher organic matrix. This was associated with lower Vickers microhardness values in comparison to sound dentin and rotary excavation. The collagen integration ratio in all methods was close to sound dentin (0.9–1.0) at the deeper dentin layer. The bromelain-chloramine-T gel (F2) produced the smoothest smear-free dentin surface with a higher number of opened dentinal tubules. In contrast, dense smearing covering the remaining dentin was observed in the manual and rotary methods with obstructed dentin tubule orifices. The bromelain-contained formulations can be considered a new minimally invasive approach for selectively removing caries in deep cavitated dentin lesions.

Subject terms: Health care, Medical research, Materials science

Introduction

The concept of minimally invasive management of deep dentin carious lesions implies the removal of soft and wet defected tissues that are heavily infiltrated by bacteria with irreversibly denatured collagen (caries-infected dentin, CID) while maintaining the deeper partially demineralized dentin (caries-affected dentin, CAD) that possesses the potential for remineralization and tissue repair1,2. Chemo-mechanical caries removal (CMCR) agents are considered a suitable approach for managing deep carious lesions that can preserve the integrity of tooth structure, maintain pulp sensibility, and thereby increase the long-term survival of the dentin-pulp complex3–7. They reduce pain and discomfort in young patients8 with a better compromise between effective and selective caries removal7,9, as they soften the irreversibly damaged collagen in carious tissues by chlorinating and disrupting their hydrogen bonds when the sodium hypochlorite-based agents are applied (GK-101E (Caridex, National Patent Dental Products, Inc., NJ, USA), and Carisolv (Medi Team Denta-lutveckling AB, Göteborg, Sweden)). While the enzyme-based agents (Carie-Care (Uni-biotech Pharmaceuticals Private Limited, India), Papacárie (Papain-based gel, Fórmula & Ação, São Paulo), and Brix 3000 (Brix, Los Arces, Santa Fe, Argentina)) promote the proteolysis of collagen cross-linkages in denatured proteins facilitating their removal by non-cutting tip instruments10.

Papacárie gel is based on a papain enzyme obtained from Carica papaya that is similar to human pepsin and has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities11. It contains chloramine-T, pectin, propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol, toluidine blue, salts, preservatives, thickeners, stabilizers, and deionized water10. Brix 3000 is the latest papain-based gel that comprises 30,000 U/mg (10%) of papain enzyme, propylene glycol, citrus pectin, triethanolamine, sorbitan monooleate, disodium phosphate, monopotassium phosphate, toluidine blue, and distilled water. It is produced by an encapsulation buffer-emulsion technology that enables the proteolytic enzyme to solidify at a neutral pH of 7, which promotes the stability of papain enzyme and enhances its reactivity against broken collagen strands12. Guedes et al.13 observed a similarity in the morphological features of residual dentin treated by Papacárie Duo and Brix 3000 under SEM; however, Brix 3000 exhibited lower cytotoxicity on the dental pulp cells due to the absence of chloramine-T, with a shorter excavation time than Papacárie Duo14.

Al-Badri et al.15 developed new chemomechanical caries removal (CMCR) agents based on bromelain, which is a cysteine endopeptidase enzyme extracted from pineapple stem with profound proteolytic activity against denatured proteins, short-chain peptides, and amide links which promote the disintegration of collagen cross-linkages and internal peptide bonds in the defected tissues, facilitating their removal16. The active site amino acids of the bromelain enzyme formed multiple interactions with type-1 collagen, with good binding affinity to chloramine-T and chlorhexidine di-gluconate (CHX) when examined by a virtual simulation method15. Three new formulations were prepared in that study15; the first gel contains 30% by wt. bromelain only (F1), the second composes of 30% by wt bromelain and 0.01 wt% chloramine-T (F2), while 1.5 wt% of CHX was added to 30% by wt of bromelain in the third gel (F3). The clinical evaluation of the remaining dentin (visual observation, tactile, and DIAGNOdent pen detector) showed the potential ability of these agents to remove dental caries effectively in a shorter time in comparison to Brix 300015. However, the chemomechanical characteristics of the residual dentin were not previously investigated to evaluate the potential ability of these agents to preserve the mineralizable tissues in comparison to conventional hand and rotary excavations.

Raman micro-spectroscopy is a highly specific, conservative approach that can examine the ultrastructural components of biological tissues quantitatively through their specific vibrational signatures17,18. It can also assess the integration of the triple helix structure in type I collagen7,18,19, by calculating the ratio of amide III to the C–H bond of pyrrolidine ring. The microhardness test remains the outstanding in-vitro method that can evaluate the mechanical properties of the remaining dentin after caries removal, resembling tactile feedback clinically, where the higher values reflect the denser crystalline structures in the dental hard tissues18,20.

Accordingly, this study assessed the selective ability of these novel bromelain-containing formulations (F1–F3) in removing carious dentin by examining the biochemical and mechanical properties of the superficial and deeper remaining tissues via Raman micro-spectroscopy, followed by the Vickers microhardness test. While, the structural characteristics of the residual dentin surfaces were viewed under the scanning electron microscope. The results were compared to a commercial CMCR agent (Brix 3000) and conventional excavation methods (hand and rotary excavation). The proposed null hypotheses were that there are statistically no significant differences in the inorganic and organic Raman peak intensities and microhardness values of the residual dentin between the experimental agents (F1-F3), Brix 3000, and the conventional methods (hand and rotary) at each dentin layer and between layers.

Methods

Sample preparation

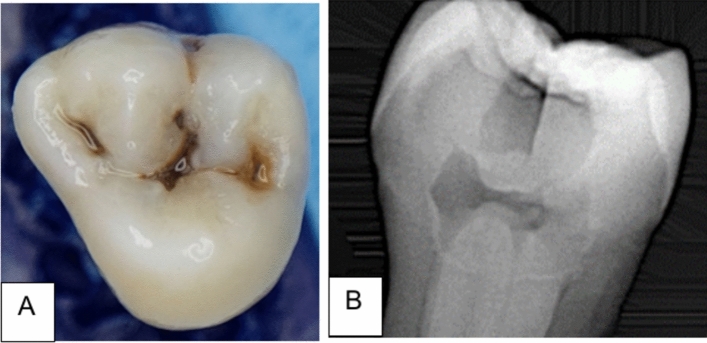

Seventy-two extracted human molars with natural carious lesions were collected from patients between 25 and 40 years old. The lesions in the selected teeth showed a score > 4 following the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS-II)21, which appeared as a dark shadow of the underlying dentin with or without loss of the surface integrity (Fig. 1A). The lesions extended through the middle third of dentin without pulp exposure, when verified by X-ray CCD-detector (Fig. 1B); however, teeth that showed extensive cavitated lesions and undermined cusps or pulpal involvement were discarded. All teeth were stored for six weeks in distilled water (4 °C) that was refreshed on a weekly basis. The ethical protocol of the selected teeth was reviewed and approved by the health research authority, reference number 505, on 3/10/2022. Teeth were randomly allocated into six groups (n = 12 per group) according to the caries excavation methods.

Figure 1.

(A) A photograph shows the carious lesion with a score > 4 following ICDAS-II, (B) X-ray photograph illustrates a radiolucent carious lesion that extends through the dentin.

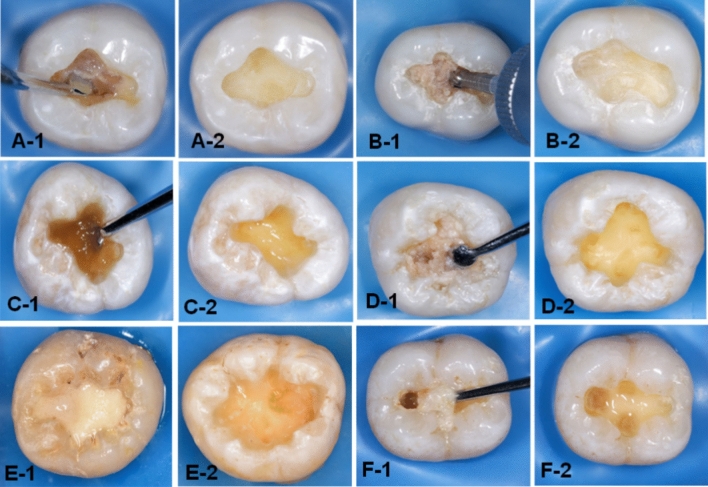

The carious lesion in dentin was exposed by preparing a class I cavity (2 mm depth) through enamel with a tungsten carbide fissure bur (HM31CL-012-FG Carbide Bur Specialty, 1.2 mm, Komet, Lemgo, Germany) attached to a high-speed handpiece (300 k rpm). In the first group, the caries was excavated manually (H excavation) using a hand-held spoon excavator instrument with a 1.3 mm diameter until complete removal of the mushy and soft carious tissues (Fig. 2A-1,A-2). These tissues were removed mechanically in the second group (R excavation) by using a round carbon steel bur with a1.2 mm cutting diameter (#1-012 Round, Komet, Lemgo, Germany) attached to a slow-speed handpiece (5–10 k rpm) with circular light strokes (Fig. 2B-1,B-2)7. Brix 3000 (Brix S.R.L., Area Industrial, Los Arces, Santa Fe, Argentina) was applied following the manufacturer’s instructions in the third group. The agent was dispensed inside each cavity and left for two minutes, then a non-sharped spoon excavator instrument was used to scrape away the caries gently in a pendulum movement. The remaining tissue was examined after each application with a sharp probe, and the procedure was repeated 2–3 times until complete removal of the wet and meshy carious tissues (Fig. 2C-1,C-2)7,15. In the last three groups (4–6), the experimental gels (bromelain agent (Br, F1), bromelain-chloramine-T (BrCh, F2), and bromelain-chlorhexidine gel (BrCHX, F3) were applied using the same procedure as Brix 3000 (Fig. 2D-1,D-2,E-1,E-2,F-1,F-2, respectively). These procedures were conducted by a single operator to eliminate inter-operator subjectivity. The endpoint of caries excavation was identified when the residual tissues appeared yellow or light brown with a firm or leathery/scratchy sensation on probing3,22. A DIAGNOdent detection pen (655-nm diode laser, KaVo, Germany) was used, and the readings in all methods were < 20 (n = 3 per cavity), which indicates the absence of infected tissues within the remained dentin23,24. Then, teeth were sectioned longitudinally (Isomet 1000, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) in a mesiodistal direction, and the buccal halves were embedded in epoxy resin molds. The examined areas received sequential polishing (P1200 for 10 s, P2500 for 10 s, and P4000 for 4 min) followed by 10 min of ultrasonic debridement7,25.

Figure 2.

Photographs illustrating the residual dentin after caries excavation methods. H excavation (A-1,A-2), R excavation (B-1,B-2), Brix 3000 (C-1,C-2), the bromelain gel (F1) (D-1,D2), bromelain-chloramine-T gel (F2), (E1,E2), and the bromelain-chlorhexidine gel (F3), (F-1,F-2).

Raman micro-spectroscopy

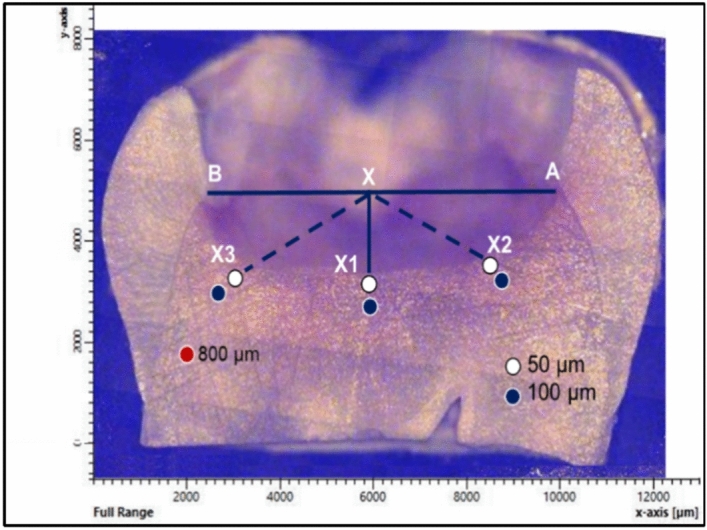

The biochemical properties of the excavated dentin were examined by using a high-resolution Raman micro-spectroscope (Senterra, Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany) that operates in point-scan mode. To standardize the examined points, a linear connection was made between both sides of the excavated cavity (AB) at the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ). From the midpoint (X), three lines were descended towards the cavity floor (X1–X3)3. Six points were examined by Raman micro-spectroscopy per sample at 50 µm and 100 µm distance from X1–X3 (Fig. 3). The peak intensity value was the average of three readings at the superficial and deeper layers. A sound dentin reference point was measured 800 µm away from the dentin-enamel junction in each tooth. Spectra acquisition was carried out by using a near-infrared diode laser (785 nm) with 400 line/mm diffraction grating, 100 mW laser power, and 30 s integration time. The beam was focused onto the surface by an Olympus objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.40, and 20× magnification and a 5 µm spot size. The spectra were taken over the range of 200–3600 cm−1, and processed by Raman software (OPUS, Bruker Optics, Germany, https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/infrared-and-raman/opusspectroscopy-software.html). Four Raman band intensities were examined: the phosphate v1 vibration, amide I, amide III, and the C–H bond of the pyrrolidine ring at 960 cm−1, 1650 cm−1, 1235 cm−1, and 1450 cm−1, respectively. The mean intensity value of each peak was the average of three readings at superficial and deeper layers (50 µm and 100 µm, respectively), which were compared to their relative sound dentin references. While the collagen integration ratios were calculated by dividing the intensity of amide III by that of C–H bond7,18,19.

Figure 3.

The selected points (n = 6) at the excavated margins that were examined by Raman spectroscopy, followed by Vickers microhardness. A sound dentin reference point was examined 800 µm away from the dentin-enamel junction.

Vickers microhardness test

The hardness profile of the residual dentin after caries excavation was evaluated by a Vickers microhardness tester (TH714, Obsnap Instruments Sdn Bhd, Malaysia). A pyramid diamond-shaped square-based indenter of 300 gf was applied for 15 seconds7,25. The examination was done on three points at 50 µm and 100 µm away from the cavity margin, which were previously scanned by Raman micro-spectroscopy (Fig. 3). The hardness value (VHN) was the average of three readings at the superficial and deeper dentin layers.

The morphological examination

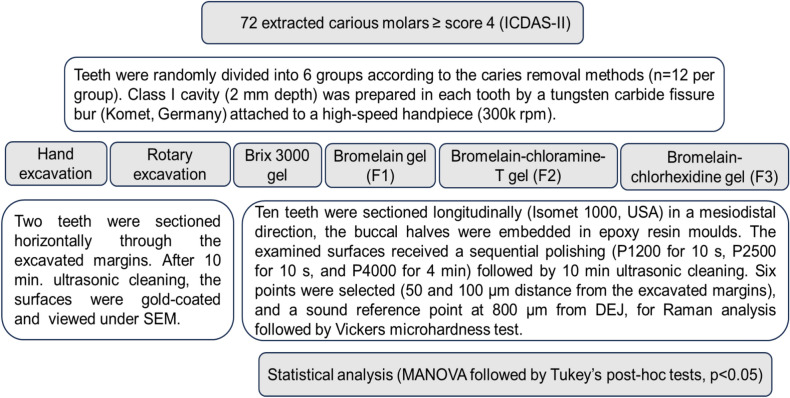

The prepared specimens were sectioned horizontally by a low-speed water-cooled diamond saw microtome (Isomet 1000, Buehler, IL, USA) at the level of the excavated margins (n = 2). After 10 min of ultrasonic debridement, the surfaces were gold-coated and viewed under a scanning electron microscope (Inspect F50, FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) by using a 30 kV accelerating voltage at three magnification powers (1500×, 3000×, and 6000×). The assessment comprised the texture of retained dentin, the presence of smearing, and the patency of dentin tubule orifices. The experimental groups and procedure are summarized in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

A scheme representing the experimental groups and procedures.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was performed using the G-Power 3.1.9.7 software (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower) developed by Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany19,26. Given a research power of 85%, an alpha error probability of 0.05 two-sided, and an effect size of F of 0.25 (medium effect size) with six groups and three measures, the required sample size is 60 samples (n = 10 per group). Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA, https://www.ibm.com/sps). The data was normally distributed (Q–Q plots and Shapiro–Wilk tests) and analyzed parametrically by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison tests. The statistical significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

The Research Ethical Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, granted the ethical approval for the current study (Ref No. 505, 10/3/2022). All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the local institutional committee in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The authors confirm that informed consent forms for all extracted teeth were obtained from all patients and/or their legal guardians. The ethical standards were followed precisely during this study. At any stage of the research, the authors confirm: (1) No person was exposed to any component of the materials or methods used in the research without any potential harm occurring for them; (2) The authors didn't use any live plants or cytotoxic materials in this investigation; and (3) Components or materials were not used in the research in a manner or concentration that would cause direct or indirect harm to the individuals carrying out the research or those in charge of the various measurement processes; (4) All the tools used in the research were dealt with in a scientific, healthy, and accurate manner, which entails the safety of individuals and places in accordance with the governing local rules and laws.

Clinical relevance

This study revealed the effectiveness of utilizing the bromelain enzyme in caries removal, which showed an ability to maintain the partially demineralized dentin with enhanced morphological features of the retained tissues. Thus, the implementation of these new formulations will provide a promising translational potential for preserving the repair capacity of the dentin-pulp complex after clinical caries removal.

Results

Chemical analysis (Raman micro-spectroscopy)

The mean (± SD) and statistical correlations of Raman peaks intensities at 50 and 100 µm distance from the cavities’ margins and their sound dentin references are presented in Table 1. Four characteristic Raman peaks were identified: the phosphate (symmetric P–O stretching mode, v1-PO43−), amide I, amide III, and C–H bond of the pyrrolidine ring at 960 cm−1, 1650 cm−1, 1235 cm−1, and 1450 cm−1, respectively. The first dentin layer (50 µm) showed a statistically significant reduction in Raman phosphate intensities after all techniques as compared to their correspondent sound references (p < 0.001). Although the values were increased towards the deeper layer (100 µm), they were only statistically significant in the chloramine-T and chlorhexidine-contained gels (F2 and F3, p = 0.030, 0.004, respectively). At both layers, the bur-excavated dentin recorded the highest phosphate intensity (p < 0.001), while, both F2 and F3 exhibited the lowest values, which were comparable to those of hand excavation, Brix 3000, and F1.

Table 1.

Raman band intensities (mean ± SD) of the remaining superficial and deep dentin after different caries removal techniques.

| The superficial layer (50 µm) | The deeper layer(100 µm) | Sound references | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate peak v1-PO43− (960 cm−1) | |||

| H excavation | 1730.7 (101.4)*aq | 1840.9 (124.6)*as | 2984.4 (163.6) |

| R excavation | 2568.2 (129.4)*b | 2610.5 (114.6)*b | 3091.3 (84.9) |

| Brix | 1708.9 (108.5)*cq | 1726.0 (111.1)*cst | 3027.6 (86.7) |

| Br(F1) | 1624.6 (102.9)*dq | 1700.7 (94.1)*dst | 3056.9 (105.2) |

| BrCh (F2) | 1528.7 (109.4)*r | 1656.5 (125.1)*t | 3034.0 (106.5) |

| BrCHX (F3) | 1534.2 (101.8)*r | 1698.0 (94.3)*st | 3044.9 (100.1) |

| Amide I (1650 cm−1) | |||

| H excavation | 24.0 (1.5)*u | 21.5 (1.2)e | 20.0 (1.9)e |

| R excavation | 19.5 (1.5)f | 19.2 (1.4)f | 18.3 (1.4)f |

| Brix | 20.9 (1.9)*pf | 19.3 (1.2)pf | 18.7 (2.3)f |

| Br (F1) | 24.4 (1.2)*u | 22.3 (1.1)*e | 18.6 (1.3) |

| BrCh (F2) | 27.4 (1.5)*v | 24.2 (1.1)*g | 20.9 (2.0) |

| BrCHX (F3) | 28.8 (1.7)*v | 25.2 (2.3)*g | 20.1 (1.2) |

| Amide III (1235 cm−1) | |||

| H excavation | 28.0 (1.2)*hw | 26.2 (1.9)*hx | 23.0 (1.5) |

| R excavation | 23.5 (1.9)*i | 22.6 (1.3)ij | 21.3 (1.5)j |

| Brix | 28.8 (1.6)*kw | 28.4 (1.7)*kx | 22.5 (1.8) |

| Br (F1) | 30.1 (2.3)*w | 27.8 (2.3)*x | 22.8 (1.2) |

| BrCh (F2) | 27.6 (1.0)*lw | 26.2 (1.3)*lx | 21.4 (1.3) |

| BrCHX (F3) | 28.7 (2.0)*mw | 27.0 (1.4)*mx | 23.8 (2.1) |

| C–H bond of pyrrolidine ring (1450 cm−1) | |||

| H excavation | 29.4 (1.4)*n | 29.3 (2.1)*nz | 22.1 (1.4) |

| R excavation | 25.3 (1.2)*o | 25.6 (1.6)*o | 21.6 (1.8) |

| Brix | 34.0 (2.2)*y | 28.3 (3.1)*z | 23.6 (1.3) |

| Br (F1) | 35.6 (2.8)*y | 28.8 (3.0)*z | 22.1 (1.1) |

| BrCh (F2) | 36.3 (2.3)*y | 30.8 (1.6)*z | 22.4 (1.4) |

| BrCHX (F3) | 38.7 (1.4)* | 31.4 (1.6)*z | 22.2 (1.5) |

H excavation: hand excavation, R excavation: Rotary excavation, Brix: Brix 3000, Br (F1): bromelain gel, BrCh (F2): bromelain-chloramine-T gel, BrCHX (F3): bromelain-chlorhexidine gel. (*): There are statistically significant differences between Raman peak intensities in the superficial and deep dentin layers from their sound dentin references. Similar letters indicate that there were statistically no significant differences between groups and layers within columns and rows. Multivariant ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc tests (alpha level of 0.05).

In contrast, the organic contents were higher in the excavated dentin in all methods, which reduced towards the deeper dentin layer (100 µm), but still lower than the relative sound dentin references (p < 0.05). The residual dentin in the rotary technique exhibited the lowest organic content among all methods (p < 0.05). Amide I was the highest in the F2 and F3 groups at both dentin layers (p < 0.05). This was followed by F1, which was close to hand excavation (p = 0.995), while both Brix and rotary excavation recorded the lowest values that were comparable to their correspondent references (p > 0.05).

For Amide III, the intensities were comparable between hand excavation and the chemical agents (commercial and experimental gels) at both layers (p > 0.05). While the lowest value was observed in the rotary excavation method, that was comparable to sound dentin (p > 0.05). Similarly, the peak intensity of the C–H bond was the lowest in the rotary method that was comparable between layers (p = 0.999). From the other hand, there was a profound increase in the intensity of C–H bond in the superficial layer of excavated dentin when the chlorhexidine-contained formula (F3) was applied, which was reduced towards the second layer (p < 0.001) approaching the values of hand excavation, Brix 3000, F1, and F2 that showed similar values at both layers (p > 0.05), (Table 1).

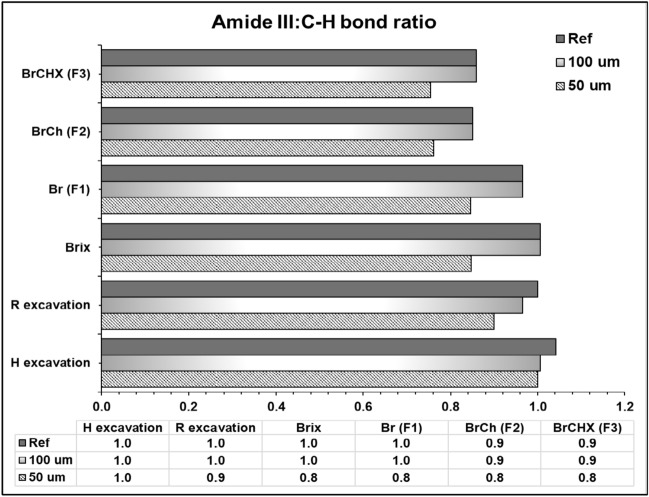

The collagen integrity ratio (Amide III: C–H bond) was the highest in the hand and bur-excavated dentin at the superficial layer (1.0, 0.9, respectively), while the lowest ratio (0.8) was noticed after applying the chemical agents (commercial and experimental), which was increased in the deeper layer approaching sound dentin (1.0) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A bar chart graph presenting the collagen integrity ratio (amide III: C–H bond pyrrolidine ring) at the superficial and deeper dentin layers and their relative sound dentin references.

Vickers microhardness

There was a significant decrease in the hardness values of residual dentin after all excavation methods as compared to their relative sound dentin reference (p < 0.001, Fig. 6), which increased significantly in the deeper layer except in hand excavation (p = 0.804). The bur-excavated dentin recorded the highest VHN among methods at both layers (p < 0.001). At the superficial layer, the hardness values were comparable (p < 0.05) between the manual excavation, Brix, and the bromelain-contained gel (F1), which in turn showed statistically no significant differences from F2 and F3, p = 0.923 and 0.106, respectively. At the deeper layer, the VHN was comparable between all groups (p > 0.05) except rotary excavation (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

A bar chart illustrating the mean Vickers hardness values of the residual dentin and non-carious dentin after different caries removal approaches. (*) There were statistically significant differences in hardness values in both layers from their sound dentin references. Similar letters mean that there were statistically no significant differences between groups within each layer. Multivariant ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc tests (alpha level of 0.05).

Discussion

This study highlighted the efficiency of bromelain-containing gels as a minimally invasive caries removal approach, replacing conventional rotary excavation. These new agents showed an ability to preserve the inorganic and organic components of the remaining dentin to support biomimetic dentin remineralization and induce tissue repair by the dentin-pulp complex or by applying suitable therapeutic materials22,27–29 without sacrificing the sound or mineralizable tooth tissues.

The micro-Raman analysis provided a representation of tissue changes that occurred during the caries process, and all spectra were recorded in the region of 877–1785 cm−1, which covers the fingerprint region of the mineral and collagen matrix in the residual dentin after caries removal. The most intense peak at 961 cm−1 represents the dentin mineral phosphate (v1 symmetric stretch of PO43−) that reflects the alterations in the mineral crystallinity and degree of tissue demineralization30. This study revealed a significant reduction (43–49%, p < 0.001) in the mineral phase of residual dentin at a 50 µm distance from the excavated margins after using the commercial papain-based and the experimental bromelain-based CMCR agents in comparison to sound dentin, indicating the presence of partially demineralized tissue17,18,30,31. However, the remaining dentin in the deeper layer (100 µm) maintains more residual mineral as the phosphate intensity increases and is comparable to that of sound dentin (p > 0.05) in all methods, except the chloramine-T and CHX-containing formulations (F2 and F3, p = 0.030 and 0.004, respectively), which maintained more demineralized tissue at both layers. Although the recorded values were higher than the previously reported values for CAD18 when the same setting parameters were applied, this relatively higher mineral level is beneficial as it can potentially control the rate of subsequent mineral deposition and the generation of prenucleation clusters for further tissue remineralization32. In contrast, the rotary-excavated surfaces maintained the highest phosphate level than all methods (p < 0.05) which means that the excavation endpoint is located within highly mineralized dentin, supporting the non-selective ability of this method that was previously reported3,7,33.

Regarding the organic phase, the spectral region of amides I and III was detected at 1650 cm−1, and 1235 cm−1, respectively. The amide I represents the secondary structure of proteins in collagen; the amide III is related to the non-reduceable cross-links of collagen34, and the C–H bond pyrrolidine rings are specified in the collagen structure of independent order35. The position and intensity of these peaks indicate an alteration in the triple helical structure of collagen fibrils that are sensitive to the microstructural changes within polypeptide chains during the caries process. This has a direct influence on tissue repair as the growth of the apatite’s crystallites takes place parallel to the long axis of collagen fibrils, and their nucleation is associated with non-collagenous proteins31,36.

Generally, the organic matrix ratio to mineral is higher in the carious tissues than sound dentin, which resulted from the degeneration in the extracellular matrix by the bacterial enzymes after disintegration of the mineral phase during the caries process37. It is manifested by the presence of esters derived from the bacterial lipid components38,39. The protein matrix is decreased in the bacterially-free dentin zone if compared to CID zone18,39, but still higher than the non-carious dentin. This was also observed in the residual dentin after all caries excavation methods in this study.

The bromelain-contained gels preserved higher levels of Amide I, III, and C–H bond in the residual dentin than sound dentin, and the highest intensities were observed in the chloramine-T and chlorhexidine-containing formulations (F2 and F3, respectively) at both layers. The amino acids (lysine, leucine, and glutamic acid) in chloramine-T have the ability to interact with various moieties in the carious tissues while reducing the aggressive effect of sodium hypochlorite on non-carious tissues, facilitating the degradation of denatured collagen in the outer soft layer with a conservative effect on the deeper layer of CAD and/or sound dentin40. This preservation of the organic matrix in the residual dentin was also noticed in the CHX-contained gel, as the CHX has a binding ability to collagen and the mineralized matrix in partially demineralized dentin due to the electrostatic interaction of the protonated amine groups in chlorhexidine with the mineral phosphate and hydroxyl groups of collagens and non-collagenous phosphoproteins41. This property confers the antiproteolytic function of CHX to inhibit the collagen-bound proteases that disintegrate the exposed collagen fibrils, contributing to the long-term stability of the CHX-treated resin-bonded interfaces42. Although the combination of CHX with bromelain minimized the activity of bromelain15, but such preservation of the organic phase is also beneficial in regulating the nucleation and maturation of the apatite crystals, inducing tissue repair30 which necessitates further investigations.

The commercial papain-contained and the experimental bromelain-contained gels maintained a higher amount of Amide III and C–H bond in the residual dentin as compared to the bur method and non-carious dentin (p < 0.001). This was associated with a lower collagen integration ratio (0.8), indicating the presence of partially demineralized tissue within the retained dentin, as this ratio denotes an apparent micro-structural alteration within the triple helical structure of collagen if the ratio is ≤ 0.87,18,19. However, in the inner layers, these microstructural changes did not seem to affect the collagen integration, as the ratio was close to that of sound dentin (0.9–1) (Fig. 5). The elevated protein level in the chemical method might be due to the proteolytic effect of both enzymes that hydrolyze the partially denatured collagen and fibrin mantle while preserving the healthy collagen fibrils. The hand excavation also maintained a higher protein content that was comparable to the chemical method, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the dissolution and the lubricating effect of these agents when assisted by the mechanical action. In contrast, the bur-excavated residual dentin showed a reduction in Amide I and III that was close to non-carious dentin (p > 0.05). The results coincide with Al-Sagheer et al.7 but are inconsistent with Pai et al.43 who found a similarity in Amide I content between rotary and Carisolv, suggesting that the use of sodium hypochlorite-based agents may not preserve more organic content by the dissolution of healthy and partially demineralized tissues.

The result of tissue hardness coincided with Raman analysis, as the lower phosphate intensity and higher organic content of excavated dentin are associated with lower VHN in comparison to non-carious dentin (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6). This agreed with previous studies17,18 that reported the presence of a direct correlation between the mineral to matrix Raman peak ratio and the equivalent microhardness number; the higher ratios are associated with higher mineral contents in the affected and sound dentin as compared to the infected tissues. This seems to be logic, as the dynamic cycles of tissue demineralization and remineralization during the carious process reduced the tissue hardness, modulus of elasticity, and intrinsic strength of the matrix31,44. This is associated with higher water content that replaced lost minerals, thus reducing the hardness of the CAD in comparison to sound dentin45,46. Interestingly, tissue hardness increased in the deeper dentin layers in all methods. This might be due to the possible occlusion of dentinal tubules by minerals that deposit during the natural repair process in the caries-affected areas47. However, the residual dentin is still softer than sound dentin, as the ultrastructure of the formed minerals during the demineralization-remineralization cycles may differ from the normal apatite48. In agreement with previous studies4,6,7, bur-excavated dentin showed higher hardness values (p < 0.05) than all methods, indicating the non-selectivity of this technique in excavating the carious and non-carious dentin simultaneously due to the lack of tactile sensation and minimal control over the process.

The proteolytic enzymes (papain and bromelain) decompose the degenerated collagen but might induce softening of the residual tissues, reducing the hardness of the chemically excavated dentin when Brix 3000 and bromelain-contained agents (F1–F3) were applied. This supports the ability of these chemical agents to preserve the partially demineralized dentin after caries removal with lower hardness values. This consistent with the results of Al-Sagheer et al.7 and Hamama et al.33 who noticed a reduction in the hardness values of the chemically excavated dentin in comparison to the bur-excavated dentin. However, Santos et al.14 showed no differences in values between the chemomechanical (Brix 3000 and Papacárie Duo) and bur excavation methods. Taking into consideration the variations in size and activity of carious lesions, the microstructural alterations, and pulp response, and there are no identical lesions even in the same individual45, all these factors are difficult to be controlled or expected.

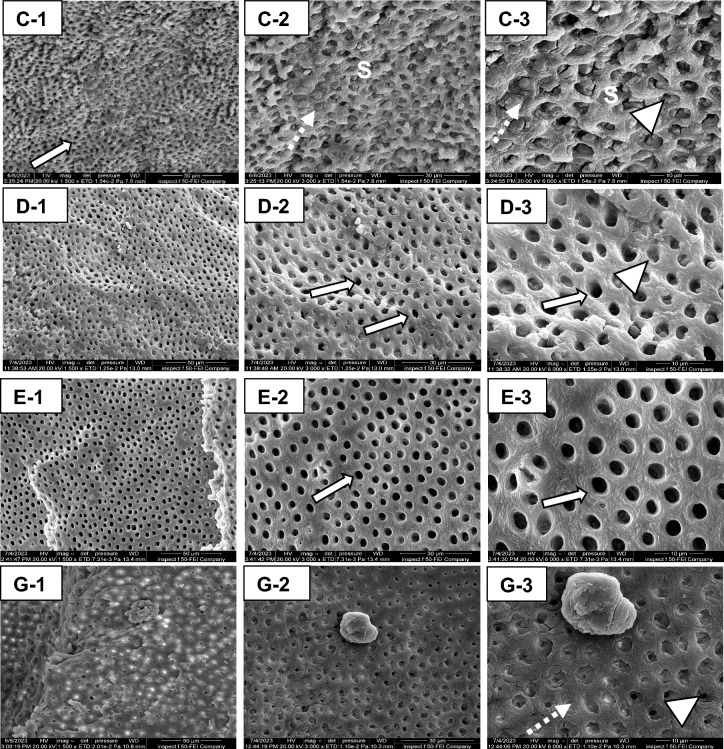

The chloramine-containing formula (F2) produced the smoother dentin surface under SEM without smearing, leaving behind a large number of patent dentinal tubules (Fig. 7E-1-3). This coincides with the observation of Al-Badri et al.15, as the oxidizing nature of sodium hypochlorite in chloramine can chlorinate proteins and break them into radicals, inducing the fragmentation of the organic phase in the thick smear layer49, which has a great influence on the diffusion of adhesive resin into intertubular dentin. F1 and F2 also produced smooth dentin surfaces (Fig. 7D-1-3 and G-1-3, respectively) with minimal smearing in comparison to Brix 3000 (Fig. 7C-1-3); however, the amount of patent tubules was relatively less than in F2 (Fig. 7E-1-3), and the majority of them are either partially or fully occluded with smear plugs. By combining CHX with bromelain, the ability of CHX to completely eliminate the smear layer was reduced compared to its previous application as a disinfectant agent, which also relies on the concertation of CHX and the duration of application50,51. In agreement with Al-Badri et al.15 and Hamama et al.32, the brix-treated surfaces illustrated the presence of more debris that obliterated the dentinal tubules. Donmez et al.52 also noticed an uneven residual dentin surface following Brix 3000, associated with a variable width of tubules’ opening combined with the presence of microorganisms. But Guedes et al.13 observed a similarity in the remaining dentin treated by Papacárie Duo, Brix 3000, and the untreated surfaces.

Figure 7.

The remaining dentin after using the CMCR agents; Brix 3000 (C-1-3), the bromelain gel (F1,D-1-3), bromelain-chloramine-T gel (F2,E-1-3), and the bromelain-chlorhexidine gel (F3,G-1-3). Less smearing (S) in all gels is noticed as compared to hand and rotary-excavated surfaces (Fig. 8). However, the surface appears rough in Brix-treated group (C-3), and the tubules are either partially occluded (arrowhead) or completely plugged (dotted arrow). F1 produced a wave-like smooth surface, and the majority of dentinal tubules are opened (white arrow, D-2), with the presence of partially-occluded tubules (arrowhead, D-3). F2 produced very smooth surface free from smearing with completely patent dentin tubules (white arrow, E-2, and 3). The residual dentin in F3 is relatively rough at low magnification (G-1) with some tissue debris. At higher magnification (G-3), the dentin tubules are either fully or partially occluded with smear plugs (dotted arrow, arrowhead, respectively).

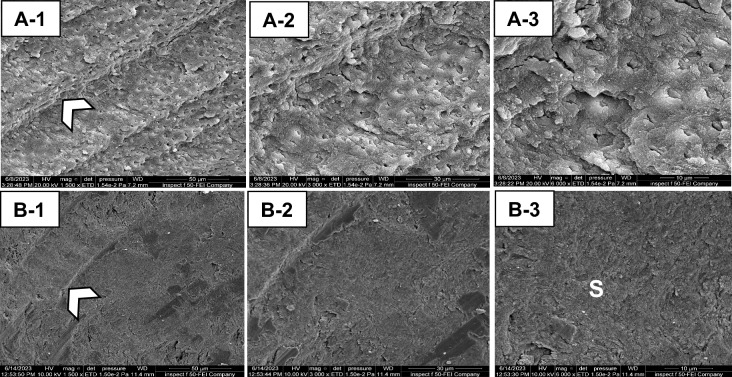

The residual dentin after hand and bur excavation produced more rough surfaces than chemically excavated dentin. There was a thick, well-formed smear layer occluding the dentinal tubules completely in hand and rotary techniques (Fig. 8A-1-3 and B-1-3, respectively). This will impede proper surface wetting and, thus, the infiltration of dental adhesives if applied without preconditioners53. This coincides with the observations of Banerjee et al.4, Hamama et al.32, and Al-Sagheer et al.7. However, the status of dentinal tubules is greatly influenced by the rate of caries progression, as more opened tubules were observed in active versus arrested lesions. Furthermore, there is a possibility of the chronic development of dental caries, which affects the morphology of the dentinal tubules.

Figure 8.

Scanning electron micrographs of the residual dentin after mechanical caries removal, hand excavation (A-1-3), and rotary excavation (B-1-3). The manual excavation produced rough surfaces that were completely covered with smear layer (S). The dentin appears rutted with the presence of tool marks (arrowhead) and some remnants of crushed debris obstructing the dentin tubules (A-3). In the bur-excavated surfaces, a homogenous thick smearing (S) was observed occluding the orifices of the dentin tubules (B-3). The bur marks (arrowhead), are observed on the surface (B-1).

The proposed hypothesis in the current study was rejected, as the application of novel bromelain-based formulations showed statistically significant changes in the chemical and mechanical properties of retained dentin when compared to the rotary method and non-carious dentin. They showed a preservation of the mineralizable dentin with enhanced structural features for subsequent integration into adhesive-based restorations. However, this investigation utilized extracted teeth with natural carious lesions of variable size and level of activity from the in vivo lesions, which requires prolonged clinical trials to extrapolate these findings.

Conclusions

This study reveals the effectiveness of utilizing the bromelain enzyme in caries removal while preserving the partially demineralized remaining dentin. The presence of chloramine or chlorhexidine maintains the inorganic and organic components of the residual dentin with lower hardness values. These results were comparable to an extent to Brix 3000 and hand excavation, which can be considered minimally-invasive alternatives to the rotary method that exhibited higher minerals with reduced organic contents approaching that of sound dentin. The novel formulations showed smooth dentin surfaces free from the smear layer, and a higher amount of opened dentinal tubules was observed in the chloramine-containing formula. Thereby, these new formulations provide a promising strategy to support the maximum reparative capacity of the dentin-pulp complex after caries removal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would acknowledge and appreciate the Baghdad College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Baghdad/Iraq, for providing the facilities and the ultimate support to accomplish this study. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Huda Al-Badri: conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing (original draft); and funding acquisition. Lamis A. Al-Taee: conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing (review and editing); visualization; and supervision. Avijit Banerjee: conceptualization; methodology; investigation; visualization; data curation; writing (review and editing). Shatha A. AL-Shammaree: methodology; investigation; visualization; data curation; writing (review and editing); and supervision.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Banerjee, A. Minimal intervention dentistry: Part 7. Minimally invasive operative caries management: Rationale and techniques. Br. Dent. J.214, 107–111. 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.106 (2013). 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwendicke, F. et al. Managing carious lesions: Consensus recommendations on carious tissue removal. Adv. Dent. Res.28, 58–67. 10.1177/0022034516639271 (2016). 10.1177/0022034516639271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee, A., Kidd, E. A. & Watson, T. F. In vitro evaluation of five alternative methods of carious dentine excavation. Caries Res.34, 144–150. 10.1159/000016582 (2000). 10.1159/000016582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, A., Kidd, E. & Watson, T. Scanning electron microscopic observations of human dentine after mechanical caries excavation. J. Dent.28, 179–186. 10.1016/S0300-5712(99)00064-0 (2000). 10.1016/S0300-5712(99)00064-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali, A., Almaroof, A., Festy, F., Banerjee, A. & Mannocci, F. In vitro remineralization of caries-affected dentin after selective carious tissue removal. World J. Dent.9, 170–179. 10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1529 (2018). 10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali, A. H. et al. Self-limiting versus conventional caries removal: A randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. Res.97, 1207–1213. 10.1177/0022034518769255 (2018). 10.1177/0022034518769255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Sagheer, R. M., Addie, A. J. & Al-Taee, L. A. An in vitro assessment of the residual dentin after using three minimally invasive caries removal techniques. Sci. Rep.14, 7087. 10.1038/s41598-024-57745-0 (2024). 10.1038/s41598-024-57745-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail, M. M. & Haidar, A. H. Impact of Brix 3000 and conventional restorative treatment on pain reaction during caries removal among group of children in Baghdad city. J. Baghdad Coll. Dent.31, 7–13. 10.26477/jbcd.v31i2.2617 (2019). 10.26477/jbcd.v31i2.2617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neves, A. D., Coutinho, E., De Munck, J. & Van Meerbeek, B. Caries-removal effectiveness and minimal-invasiveness potential of caries-excavation techniques: a micro-CT investigation. J. Dent.39, 154–162. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.11.006 (2011). 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobboletta, M. & Brix, USA LLC. Dental gel composition of papain for the atraumatic treatment of caries and method of preparing same. U.S. Patent. 10,137,178 (2018).

- 11.Bussadori, S. K., Castro, L. C. & Galvão, A. C. Papain gel: a new chemo-mechanical caries removal agent. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent.30, 115–120 (2005). 10.17796/jcpd.30.2.xq641w720u101048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyfarth, S., Cassano, K., Warol, F., de DeusSantos, M. & Scarparo, A. A new efficient agent to chemomechanical caries removal. Braz. Dent. J.77, e1946. 10.18363/rbo.v77.2020.e1946 (2020). 10.18363/rbo.v77.2020.e1946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guedes, F. R. et al. Cytotoxicity and dentin composition alterations promoted by different chemomechanical caries removal agents: A preliminary in vitro study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent.13, e826–e834. 10.4317/jced.58208 (2021). 10.4317/jced.58208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos, T. M. L. et al. Comparison between conventional and chemomechanical approaches for the removal of carious dentin: An in vitro study. Sci. Rep.10, 8127. 10.1038/s41598-020-65159-x (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-65159-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Badri, H., Al-Shammaree, S. A., Banerjee, A. & Al-Taee, L. A. The in-vitro development of novel enzyme-based chemo-mechanical caries removal agents. J. Dent.138, 104714. 10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104714 (2023). 10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavan, R., Jain, S., Shraddha, & Kumar, A. Properties and therapeutic application of bromelain: A review. Biotechnol. Res. Int.2012, 976203. 10.1155/2012/976203 (2012). 10.1155/2012/976203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alturki, M., Koller, G., Almhöjd, U. & Banerjee, A. Chemo-mechanical characterization of carious dentine using Raman microscopy and Knoop microhardness. R. Soc. Open Sci.7, 200404. 10.1098/rsos.200404 (2020). 10.1098/rsos.200404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Shareefi, S., Addie, A. & Al-Taee, L. Biochemical and mechanical analysis of occlusal and proximal carious lesions. Diagnostics.12, 2944. 10.3390/diagnostics12122944 (2022). 10.3390/diagnostics12122944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Júnior, Z. S. et al. Effect of papain-based gel on type I collagen-spectroscopy applied for microstructural analysis. Sci. Rep.5, 1–7. 10.1038/srep11448 (2015). 10.1038/srep11448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alturki, M., Koller, G., Warburton, F., Almhöjd, U. & Banerjee, A. Biochemical characterisation of carious dentine zones using Raman spectroscopy. J. Dent.105, 103558. 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103558 (2021). 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitts, N. B. & Ekstrand, K. R. I.C.D.A.S. Foundation, International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) and its International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS)-methods for staging of the caries process and enabling dentists to manage caries Community. Dent. Oral. Epidemiol.41, e41–e52. 10.1111/cdoe.12025 (2013). 10.1111/cdoe.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Innes, N. P. T. et al. Managing carious lesions: Consensus recommendations on terminology. Adv. Dent. Res.28, 49–57. 10.1177/0022034516639276 (2016). 10.1177/0022034516639276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lussi, A. et al. Detection of approximal caries with a new laser fluorescence device. Caries Res.40, 97–103. 10.1159/000091054 (2006). 10.1159/000091054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadasiva, K. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of visual, tactile method, caries detector dye, and laser fluorescence in removal of dental caries and confirmation by culture and polymerase chain reaction: An in vivo study. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci.11, S146–S150. 10.4103/JPBS.JPBS_279_18 (2019). 10.4103/JPBS.JPBS_279_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Hasan, R. M. & Al-Taee, L. A. Interfacial bond strength and morphology of sound and caries-affected dentin surfaces bonded to two resin-modified glass ionomer cements. Oper. Dent.47, E188–E196. 10.2341/21-048-L (2022). 10.2341/21-048-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods.41, 1149–1160. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 (2009). 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali, A. H., Thani, G. B., Foschi, F., Banerjee, A. & Mannocci, F. Self-limiting versus rotary subjective carious tissue removal: A randomized controlled clinical trial-2-year results. J. Clin. Med.9, 2738. 10.3390/jcm9092738 (2020). 10.3390/jcm9092738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al Taee, L., Banerjee, A. & Deb, S. An integrated multifunctional hybrid cement (pRMGIC) for dental applications. Dent. Mater.35, 636–649. 10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.005 (2019). 10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Taee, L., Banerjee, A. & Deb, S. In-vitro adhesive and interfacial analysis of a phosphorylated resin polyalkenoate cement bonded to dental hard tissues. J. Dent.118, 104050. 10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104050 (2022). 10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almahdy, A. et al. Microbiochemical analysis of carious dentine using Raman and fluorescence spectroscopy. Caries Res.46, 432–440. 10.1159/000339487 (2012). 10.1159/000339487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, Y., Spencer, P. & Walker, M. P. Chemical profile of adhesive/caries-affected dentin interfaces using Raman microspectroscopy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.81, 279–286. 10.1002/jbm.a.30981 (2007). 10.1002/jbm.a.30981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, Y. et al. The use of sodium trimetaphosphate as a biomimetic analog of matrix phosphoproteins for remineralization of artificial caries-like dentin. Dent. Mater.27, 465–477. 10.1016/j.dental.2011.01.008 (2011). 10.1016/j.dental.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamama, H. H., Yiu, C. K., Burrow, M. F. & King, N. M. Chemical, morphological and microhardness changes of dentine after chemomechanical caries removal. Aust. Dent. J.58, 283–292. 10.1111/adj.12093 (2013). 10.1111/adj.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramakrishnaiah, R. et al. Applications of Raman spectroscopy in dentistry, analysis of tooth structure. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev.50, 332–350. 10.1080/05704928.2014.986734 (2015). 10.1080/05704928.2014.986734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sylvester, M. F., Yannas, I. V., Salzman, E. W. & Forbes, M. J. Collagen banded fibril structure and the collagen-platelet reaction. Thromb. Res.55, 135–148. 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90463-5 (1989). 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90463-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopes, C. D. A. et al. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) application chemical characterization of enamel, dentin and bone. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev.53, 747–769. 10.1080/05704928.2018.1431923 (2018). 10.1080/05704928.2018.1431923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ko, A. C. et al. Early dental caries detection using a fibre-optic coupled polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopic system. Opt. Express.16, 6274–6284. 10.1364/OE.16.006274 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.006274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almhöjd, U. S., Norén, J. G., Arvidsson, A., Nilsson, A. & Lingström, P. Analysis of carious dentine using FTIR and ToF-SIMS. Oral. Health. Dent. Manag.13, 735–744 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alturki, M., Almhöjd, U., Koller, G., Warburton, F. & Banerjee, A. In vitro analysis of organic ester functional groups in carious dentine. Appl. Sci.12, 1088. 10.3390/app12031088 (2022). 10.3390/app12031088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tonami, K. I., Araki, K., Mataki, S. & Kurosaki, N. Effects of chloramines and sodium hypochlorite on carious dentin. J. Med. Dent. Sci.50, 139–146. 10.11480/jmds.500201 (2003). 10.11480/jmds.500201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrilho, M. R. et al. Substantivity of chlorhexidine to human dentin. Dent. Mater.26, 779–785. 10.1016/j.dental.2010.04.002 (2010). 10.1016/j.dental.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komori, P. C. P. et al. Effect of 2% chlorhexidine digluconate on the bond strength to normal versus caries-affected dentin. Oper. Dent.34, 157–165. 10.2341/08-55 (2009). 10.2341/08-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pai, V. S. et al. Chemical analysis of dentin surfaces after Carisolv treatment. Conserv. Dent. Endod. J.12, 118–122. 10.4103/0972-0707.57636 (2009). 10.4103/0972-0707.57636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pugach, M. K. et al. Dentin caries zones: Mineral, structure, and properties. J. Dent. Res.88, 71–76. 10.1177/0022034508327552 (2009). 10.1177/0022034508327552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall, G. W. et al. Nanomechanical properties of hydrated carious human dentin. J. Dent. Res.80, 1768–1771. 10.1177/00220345010800081701 (2001). 10.1177/00220345010800081701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng, L., Hilton, J. F., Habelitz, S., Marshall, S. J. & Marshall, G. W. Dentin caries activity status related to hardness and elasticity. Eur. J. Oral. Sci.111, 243–252. 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00038.x (2003). 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banerjee, A., Sherriff, M., Kidd, E. A. M. & Watson, T. F. A confocal microscopic study relating the autofluorescence of carious dentine to its microhardness. Br. Dent. J.187, 206–210. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800241 (1999). 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogawa, K., Yamashita, Y., Ichijo, T. & Fusayama, T. The ultrastructure and hardness of the transparent layer of human carious dentin. J. Dent. Res.62, 7–10. 10.1177/00220345830620011701 (1983). 10.1177/00220345830620011701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakajima, M., Kunawarote, S., Prasansuttiporn, T. & Tagami, J. Bonding to caries- affected dentin. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev.47, 102–114. 10.1016/j.jdsr.2011.03.002 (2011). 10.1016/j.jdsr.2011.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khalil, R. J. & Al-Shamma, A. M. Early and delayed effect of 2% chlorhexidine on the shear bond strength of composite restorative material to dentin using a total etch adhesive. J. Baghdad Coll. Dent.325, 1–17 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapinska, B., Klimek, L., Sokolowski, J. & Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Dentine surface morphology after chlorhexidine application-SEM study. Polymers.10, 905. 10.3390/polym10080905 (2018). 10.3390/polym10080905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donmez, N., Kazak, M., Kaynar, Z. B. & Sesen Uslu, Y. Examination of caries-affected dentin and composite-resin interface after different caries removal methods: A scanning electron microscope study. Microsc. Res. Tech.85, 2212–2221. 10.1002/jemt.24078 (2022). 10.1002/jemt.24078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kinoshita, J. I., Kimura, Y. & Matsumoto, K. Comparative study of carious dentin removal by Er, Cr:YSGG laser and Carisolv. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg.21, 307–315. 10.1089/104454703322564532 (2003). 10.1089/104454703322564532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.