Abstract

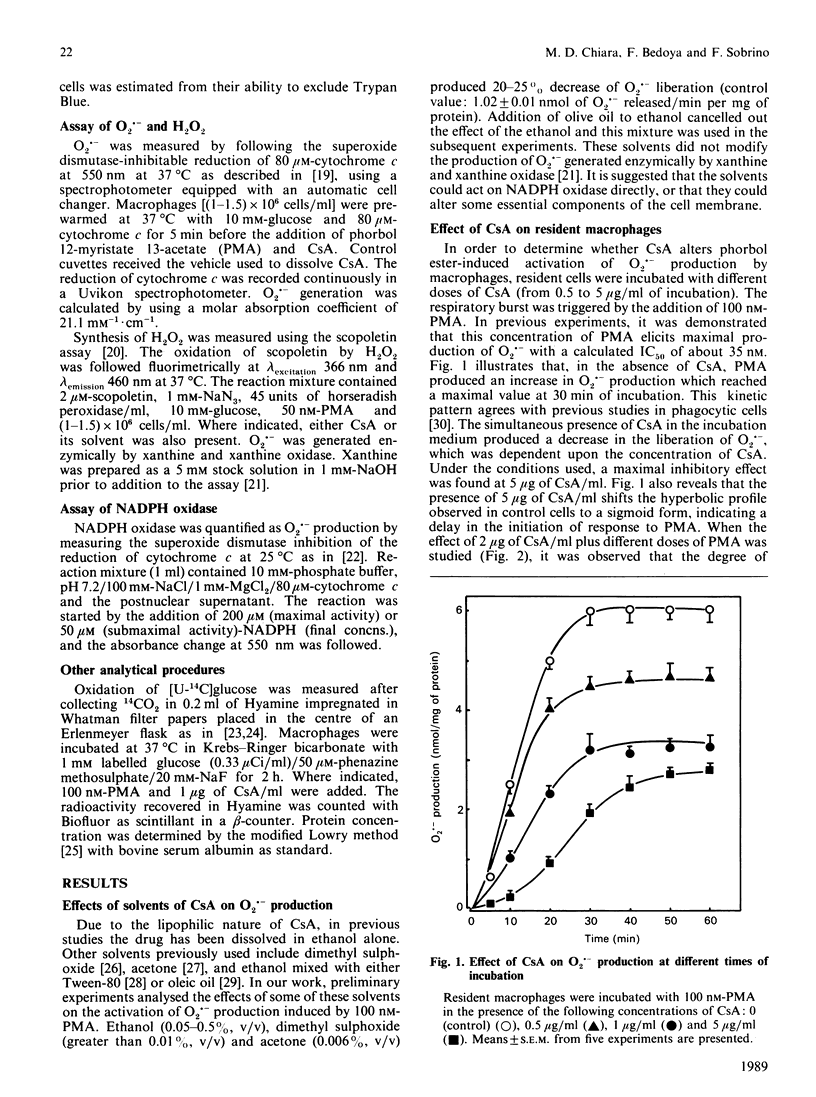

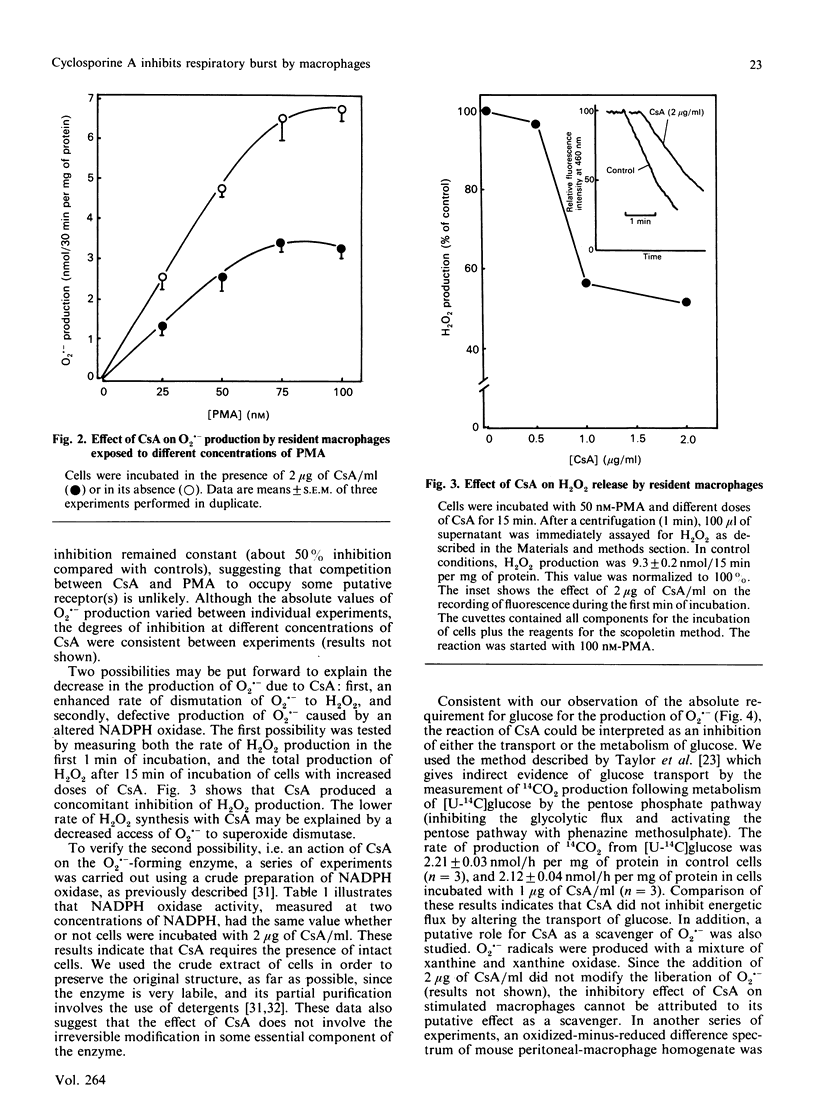

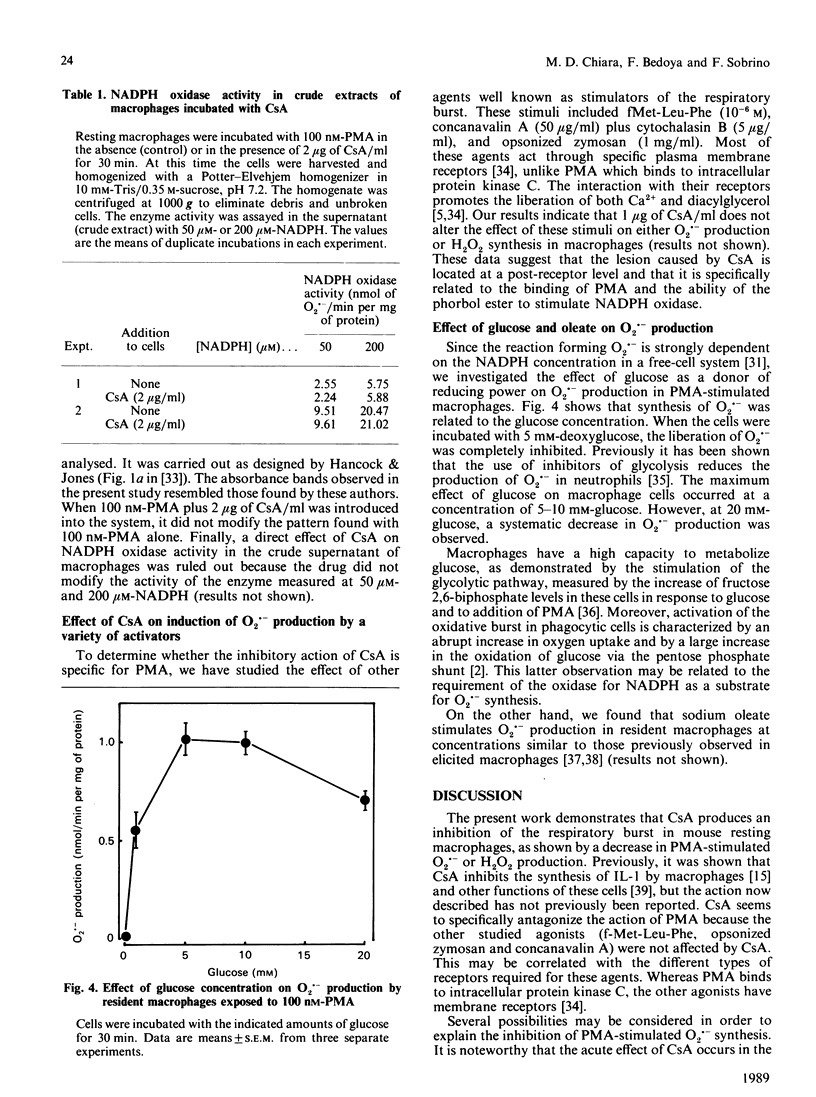

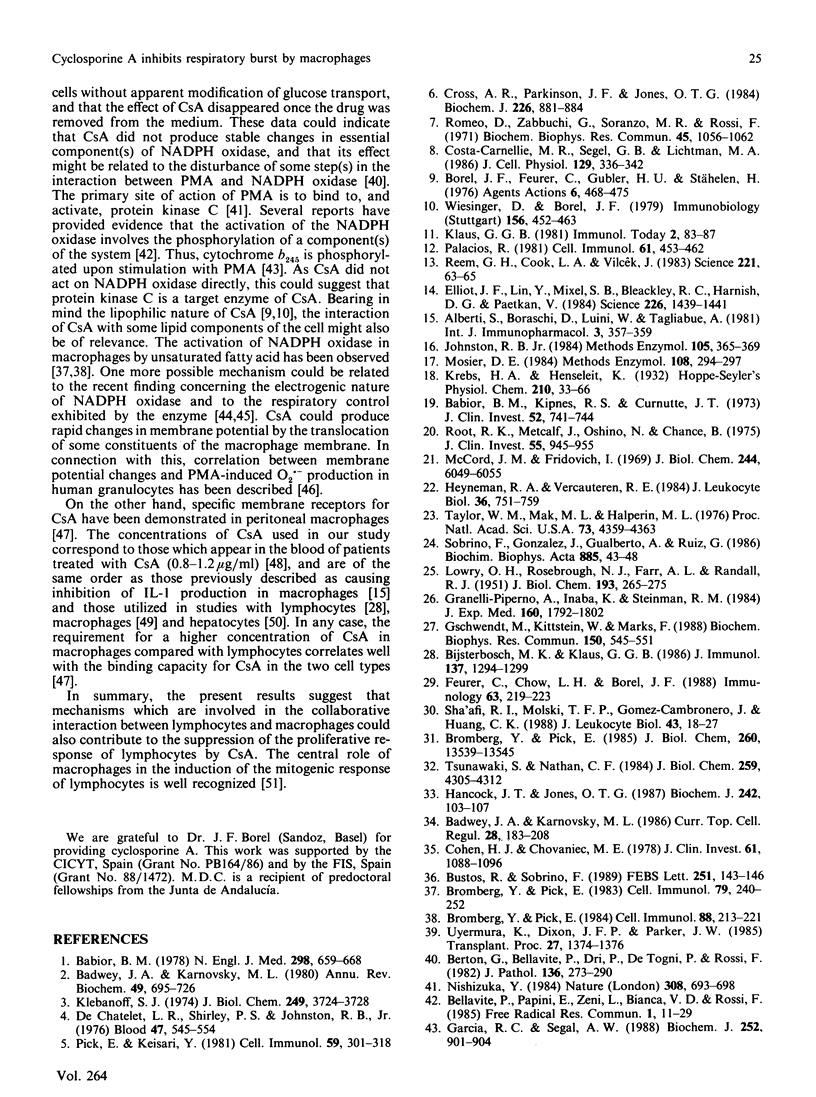

Peritoneal resident macrophages from mice are sensitive to inhibition by cyclosporin A (CsA) of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-stimulated oxidative burst. Inhibition was assessed in terms of superoxide anion (O2.-) and H2O2 production. Key findings were as follows. (a) CsA inhibited in a dose-dependent manner the production of O2.- when cells were stimulated with PMA. CsA did not alter the respiratory burst induced by other stimuli (zymosan, concanavalin A and fMet-Leu-Phe). It was verified that CsA itself had no scavenger effect. (b) A concomitant decrease in H2O2 liberation following CsA exposure was found. This inhibition was observed both in the initial rate of synthesis and in the accumulation after 15 min of incubation. (c) NADPH oxidase activity in the crude supernatant was unaffected by the previous incubation of macrophages with CsA. CsA does not inhibit glucose transport measured as 14CO2 production. (d) The production of O2.- was strongly dependent on the glucose concentration. Sodium oleate also stimulated O2.- production in resident macrophages. These data might be correlated with the inhibitory effect of CsA upon other functions of macrophages.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alberti S., Boraschi D., Luini W., Tagliabue A. Effects of in vivo treatments with cyclosporin-A on mouse cell-mediated immune responses. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1981;3(4):357–364. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(81)90031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Kipnes R. S., Curnutte J. T. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M. Oxygen-dependent microbial killing by phagocytes (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1978 Mar 23;298(12):659–668. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803232981205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badwey J. A., Karnovsky M. L. Active oxygen species and the functions of phagocytic leukocytes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:695–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badwey J. A., Karnovsky M. L. Production of superoxide by phagocytic leukocytes: a paradigm for stimulus-response phenomena. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1986;28:183–208. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152828-7.50006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavite P., Papini E., Zeni L., Della Bianca V., Rossi F. Studies on the nature and activation of O2(-)-forming NADPH oxidase of leukocytes. Identification of a phosphorylated component of the active enzyme. Free Radic Res Commun. 1985;1(1):11–29. doi: 10.3109/10715768509056533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton G., Bellavite P., Dri P., de Togni P., Rossi F. The enzyme responsible for the respiratory burst in elicited guinea pig peritoneal macrophages. J Pathol. 1982 Apr;136(4):273–290. doi: 10.1002/path.1711360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijsterbosch M. K., Klaus G. G. Concanavalin A induces Ca2+ mobilization, but only minimal inositol phospholipid breakdown in mouse B cells. J Immunol. 1986 Aug 15;137(4):1294–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel J. F., Feurer C., Gubler H. U., Stähelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: a new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions. 1976 Jul;6(4):468–475. doi: 10.1007/BF01973261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y., Pick E. Activation of NADPH-dependent superoxide production in a cell-free system by sodium dodecyl sulfate. J Biol Chem. 1985 Nov 5;260(25):13539–13545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y., Pick E. Unsaturated fatty acids as second messengers of superoxide generation by macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1983 Jul 15;79(2):240–252. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y., Pick E. Unsaturated fatty acids stimulate NADPH-dependent superoxide production by cell-free system derived from macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1984 Oct 1;88(1):213–221. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos R., Sobrino F. Control of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate levels in rat macrophages by glucose and phorbol ester. FEBS Lett. 1989 Jul 17;251(1-2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H. J., Chovaniec M. E. Superoxide production by digitonin-stimulated guinea pig granulocytes. The effects of N-ethyl maleimide, divalent cations; and glycolytic and mitochondrial inhibitors on the activation of the superoxide generating system. J Clin Invest. 1978 Apr;61(4):1088–1096. doi: 10.1172/JCI109008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Casnellie M. R., Segel G. B., Lichtman M. A. Signal transduction in human monocytes: relationship between superoxide production and the level of kinase C in the membrane. J Cell Physiol. 1986 Dec;129(3):336–342. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical issues in cyclosporine monitoring: report of the Task Force on Cyclosporine Monitoring. Clin Chem. 1987 Jul;33(7):1269–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A. R., Parkinson J. F., Jones O. T. Mechanism of the superoxide-producing oxidase of neutrophils. O2 is necessary for the fast reduction of cytochrome b-245 by NADPH. Biochem J. 1985 Mar 15;226(3):881–884. doi: 10.1042/bj2260881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChatelet L. R., Shirley P. S., Johnston R. B., Jr Effect of phorbol myristate acetate on the oxidative metabolism of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 1976 Apr;47(4):545–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. F., Lin Y., Mizel S. B., Bleackley R. C., Harnish D. G., Paetkau V. Induction of interleukin 2 messenger RNA inhibited by cyclosporin A. Science. 1984 Dec 21;226(4681):1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.6334364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feurer C., Chow L. H., Borel J. F. Preventive and therapeutic effects of cyclosporin and valine2-dihydro-cyclosporin in chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in the Lewis rat. Immunology. 1988 Feb;63(2):219–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R. C., Segal A. W. Phosphorylation of the subunits of cytochrome b-245 upon triggering of the respiratory burst of human neutrophils and macrophages. Biochem J. 1988 Jun 15;252(3):901–904. doi: 10.1042/bj2520901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granelli-Piperno A., Inaba K., Steinman R. M. Stimulation of lymphokine release from T lymphoblasts. Requirement for mRNA synthesis and inhibition by cyclosporin A. J Exp Med. 1984 Dec 1;160(6):1792–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greineder D. K., Shevach E. M., Rosenthal A. S. Macrophage-lymphocyte interaction. III. Site of alloantiserum inhibition of T lymphocyte proliferation induced by allogeneic or aldehyde-bearing cells. J Immunol. 1976 Oct;117(4):1261–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwendt M., Kittstein W., Marks F. The weak immunosuppressant cyclosporine D as well as the immunologically inactive cyclosporine H are potent inhibitors in vivo of phorbol ester TPA-induced biological effects in mouse skin and of Ca2+/calmodulin dependent EF-2 phosphorylation in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988 Jan 29;150(2):545–551. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. T., Jones O. T. The inhibition by diphenyleneiodonium and its analogues of superoxide generation by macrophages. Biochem J. 1987 Feb 15;242(1):103–107. doi: 10.1042/bj2420103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L. M., Chappell J. B., Jones O. T. Internal pH changes associated with the activity of NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils. Further evidence for the presence of an H+ conducting channel. Biochem J. 1988 Apr 15;251(2):563–567. doi: 10.1042/bj2510563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L. M., Chappell J. B., Jones O. T. Superoxide generation by the electrogenic NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils is limited by the movement of a compensating charge. Biochem J. 1988 Oct 1;255(1):285–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyneman R. A., Vercauteren R. E. Activation of a NADPH oxidase from horse polymorphonuclear leukocytes in a cell-free system. J Leukoc Biol. 1984 Dec;36(6):751–759. doi: 10.1002/jlb.36.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R. B., Jr Measurement of O2- secreted by monocytes and macrophages. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff S. J. Role of the superoxide anion in the myeloperoxidase-mediated antimicrobial system. J Biol Chem. 1974 Jun 25;249(12):3724–3728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem. 1969 Nov 25;244(22):6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier D. E. Separation of macrophages on plastic and glass surfaces. Methods Enzymol. 1984;108:294–297. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)08094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicchitta C. V., Kamoun M., Williamson J. R. Cyclosporine augments receptor-mediated cellular Ca2+ fluxes in isolated hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1985 Nov 5;260(25):13613–13618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. The role of protein kinase C in cell surface signal transduction and tumour promotion. Nature. 1984 Apr 19;308(5961):693–698. doi: 10.1038/308693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios R. Cyclosporin A inhibits the proliferative response and the generation of helper, suppressor and cytotoxic T-cell functions in the autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction. Cell Immunol. 1981 Jul 1;61(2):453–462. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(81)90393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick E., Keisari Y. Superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by chemically elicited peritoneal macrophages--induction by multiple nonphagocytic stimuli. Cell Immunol. 1981 Apr;59(2):301–318. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(81)90411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reem G. H., Cook L. A., Vilcek J. Gamma interferon synthesis by human thymocytes and T lymphocytes inhibited by cyclosporin A. Science. 1983 Jul 1;221(4605):63–65. doi: 10.1126/science.6407112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo D., Zabucchi G., Soranzo M., Rossi F. Macrophage metabolism: activation of NADPH oxidation by phagocytosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971 Nov;45(4):1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root R. K., Metcalf J., Oshino N., Chance B. H2O2 release from human granulocytes during phagocytosis. I. Documentation, quantitation, and some regulating factors. J Clin Invest. 1975 May;55(5):945–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI108024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryffel B., Donatsch P., Götz U., Tschopp M. Cyclosporin receptor on mouse lymphocytes. Immunology. 1980 Dec;41(4):913–919. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha'afi R. I., Molski T. F., Gomez-Cambronero J., Huang C. K. Dissociation of the 47-kilodalton protein phosphorylation from degranulation and superoxide production in neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1988 Jan;43(1):18–27. doi: 10.1002/jlb.43.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino F., Gonzalez J., Gualberto A., Ruiz G. Short-term stimulation by adenosine of basal and insulin-induced glycogen synthesis in rat adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986 Jan 23;885(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(86)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W. M., Mak M. L., Halperin M. L. Effect of 3':5'-cyclic AMP on glucose transport in rat adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Dec;73(12):4359–4363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. W., Moon D. K., Geczy C. L., Nelson D. S. Cyclosporin A inhibits lymphokine production but not the responses of macrophages to lymphokines. Immunology. 1983 Feb;48(2):291–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunawaki S., Nathan C. F. Enzymatic basis of macrophage activation. Kinetic analysis of superoxide production in lysates of resident and activated mouse peritoneal macrophages and granulocytes. J Biol Chem. 1984 Apr 10;259(7):4305–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitin J. C., Chapman C. E., Simons E. R., Chovaniec M. E., Cohen H. J. Correlation between membrane potential changes and superoxide production in human granulocytes stimulated by phorbol myristate acetate. Evidence for defective activation in chronic granulomatous disease. J Biol Chem. 1980 Mar 10;255(5):1874–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesinger D., Borel J. F. Studies on the mechanism of action of cyclosporin A. Immunobiology. 1980 Jan;156(4-5):454–463. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(80)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]