Abstract

Background: Orlistat (ORS) and metformin (MEF) are robustly used as well-established clinical drugs for the treatment for both obesity and the consequences of diabetes mellitus. Additionally, no study has been conducted to explore the consequence of the combination of both ORS and MEF on the kidneys of rats with obesity-induced renal injury (OBS). Objectives: Therefore, the objective of the current research was designed to explore the possible ameliorative effects of either ORS and/or MEF or their combination against obesity (OBS) induced experimental renal oxidative stress. Methods: Renal oxidative stress was investigated at redox histopathological and immunohistological points in the kidney tissues. Results: The levels of urea, uric acid, and creatinine increased with the obesity effect; in addition, the myeloperoxidase (MPO) and xanthine oxidase (XO) activators were elevated significantly with the induction of OBS. The levels of non-enzymatic antioxidants (glutathione and thiol) declined sharply in OBS rats as compared to the normal group. Conclusion: The data displayed that the combination of both ORS and MEF declined the obesity effects significantly by reducing the level of peroxidation (MDA), and enhancement intracellular antioxidant enzymes. These biochemical findings were supported by histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and Masson-Trichrome evaluation, which showed minor morphological changes in the kidneys of rats.

Keywords: nephrotoxicity, renal toxicity, excessive weight, orlistat, metformin, obesity, oxidative stress, kidney functions

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Obesity, a pervasive and intricate metabolic disorder, stands at the intersection of various health challenges, including the development of diabetes mellitus.1–3 In addressing the consequences of obesity, orlistat (ORS) and metformin (MEF) have emerged as stalwart treatments, particularly in diabetes management.4,5 Despite their efficacy, a significant research gap exists in understanding the collective impact of ORS and MEF on the renal system when confronted with obesity-induced renal injury (OBS).6 Renal complications stemming from obesity manifest as a spectrum of structural and functional alterations, underscoring the urgency of targeted interventions.7–10

Although prior studies have shed light on the individual effects of ORS and MEF, a nuanced exploration of their combined synergistic impact on the kidneys during experimentally induced obesity remains scarce.11 Given the intricate interplay between obesity, diabetes, and renal physiology, to uncover potential synergies between these pharmaceutical agents in mitigating renal oxidative stress.12,13

Biochemical markers such as urea, uric acid, and creatinine, alongside indicators of inflammatory and oxidative stress (myeloperoxidase and xanthine oxidase),14–16 will be scrutinized to unravel the intricate consequences of obesity on renal function.

It has been demonstrated that orlistat (ORS) lowers blood levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and total cholesterol without affecting weight reduction.17–19 Consistent with earlier research, previous clinical trial demonstrated that concurrent administration of phentermine and ORS improves vascular endothelial cell function and significantly lowers total cholesterol and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol when compared to phentermine alone.20 ORS may so reduce the risk of CVD. However, the precise mechanism underlying the earlier findings remains ambiguous, and additional investigation is required to assess the medication’s long-term benefit on cardiovascular risk.

Specifically, being overweight increases the risk of urinary damage. According to epidemiological research, the physiological risk level increases with each unit increase in body mass index.21 A study conducted on animals revealed that OBS induced adipocytes to produce more uric acid through the effect of hypoxia.22 Reduced uric acid levels and protection against gout flare-ups are two long-term benefits of weight loss.23

(ORS) is a strong, permanent lipase inhibitor that prevents triglycerides from diets from being absorbed.24 The China National Medical Products Administration has authorized ORS for the treatment of patients who are obese. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of ORS in ameliorating obesity and associated disorders, including metabolic fatty liver disease.25,26

In patients with polycystic ovary syndrome who were overweight or obese, ORS plus Diane-35 significantly lowered their serum uric acid levels.27 However, there was no discernible difference when Diane-35 was given alone. Patients with type 2 diabetes showed significant improvements in serum uric acid levels when taking ORS in conjunction with a low-calorie diet.28

Previous study,29 proved that MEF improved insulin parameters, while no effect was detected when compared to lifestyle modification. A few small trials showed heterogenous effects on liver parameters in patients with NAFLD treated with MEF compared to control. MEF was associated with a modest weight reduction in obese non-diabetic patients. Further high-quality and better powered studies are needed to examine the impact of MEF in patients with insulin resistance.29

This study aims to assess the possible synergistic actions between ORS and MEF in amelioration of antioxidant enzyme capacities with amelioration of renal functions and to mitigate the harmful effects of obesity on renal function.

Materials and methods

Reagent a and chemicals

ORS was purchased from October Pharma. MET was obtained from Chemical Industries Development Co., Egypt. Other used chemicals in this study was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Corporation (St Louis, MO, United States). Assay kits for antioxidant, oxidative and other biomarkers assay kits were purchased from Biodiagnostic Co., and BioMed Diagnostics (Egypt).

Ethical statement and experimental animals

50 male albino rats “2 months age” and weighing 150–180 g. The male rats were all housed in hygienic metal cages with controlled all environmental conditions and free regular standard feed and water for the normal control group. Meanwhile, the obese groups were given high fat diets and marked as (OBS) animals. This experimental work was carried out in accordance with European animal care and was approved by Zagazig University’s (ZU-IACUC ethical committee) under approval number (ZU-IACUC/1/F/102/2023). Based on the obtained ethical approval, euthanasia was obtained via administration of Ketamine-Xylazine at very low dosage to avoid any possible pain.

Experimental groups

50 male rats were divided randomly into 5 groups, 10 male rats/per group. The experimental design and timeline are shown in (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and experimental timeline.

For induction of Obesity: For 30 successive days, male rats were fed a high-fat diet with 26500.00 kcal/kg−1 of calories per day (twice per day). The following was the makeup of HFD: A supplement of vitamin D and certain trace minerals like Cu, I2, Se, and Zn was added to the diet, which consisted of 34% fat, 25% fiber, 22% protein, 7% salt, 10% ash, and 2% calcium. The HFD groups treated using either ORS and/or MEF or their combination for another 30 successive days.

Treatment groups was divided into 5 group as follows:

(I-Control group): was fed a standard diet of a normal equally balanced diet with the addition of water ad libitum; (II-OBS group): High-fat diet successively for 30 days; (III-OBS + ORS group): The male rats were fed and induced OBS, followed by successive administrations of ORS at a dosage of (2 mg Kg−1) based on previous studies30,31 for successive 30 days; (IV-OBS + MEF group): Male rats were fed and induced OBS and then concurrent treatment of MEF at a dosage of (70 mg Kg−1)30,31; (V-OBS+ ORS+ MEF group): Male rats were OBS followed by subsequent treatment with both ORS and MEF (1/2 h after the 1st dose) at a dose for successive 30 days.

Samples collection

Following the completion of the 30-day experiment, 50 serum samples were obtained from the eye plexus following light anesthesia with Xylene/Ketamine prior to animal sacrifice in accordance with ethical approval and international guidelines for animal care. Blood samples were centrifuged at ~3,000 r.p.m. for approximately 5 min to obtain the serum samples. After being used, the serum samples were suddenly preserved at −20 °C in a refrigerator. Following xylene/ketamine (I.P.) anesthesia, the experimental animals were suddenly decapitated, and the renal tissues were removed. Two portions of the tissues were used for immunological testing, histology, and Masson Trichrome staining, while the remaining portion was used to measure the antioxidant enzymes’ capacities following homogenization. The tissue homogenates’ supernatants were collected and used at −20 °C for.

Biochemical investigation

Measurement of kidney functions

The urea, creatinine, and uric acid levels were quantified using commercially procured kits sourced from Human Gesellschaft for Biochemical and Diagnostics mbH, Germany. These kits are designed for biochemical and diagnostic analyses. The determination of analyte concentrations was performed following the specific protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Preparation of tissue homogenates for antioxidant assays

Small piece (~0.25 g) of renal tissues were used to estimate the oxidative stress and antioxidant parameters. Renal tissues were washed with 50 mM of cold ice alkaline buffer sodium phosphate buffer saline (100 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, pH 7.4), 0.25 M sucrose and 0.1 mM EDTA. Then, the renal tissues were blended using a Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer (High speed homogenizer FSH-2A, LABFENG, China) (5-mL cold buffer/g), The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C for determining the enzymatic assays and were centrifuged at 2,500 × g for lipid peroxidation level, after centrifugation, the tissues will be depleted at the bottom of the tube and then,discarded and the pure liquid solution (Tissue extraction solution: Supernatant) will be used, and then get the supernatant for performing the antioxidant assays, the supernatant was preserved in the deep freezer −20 °C, until being used.

Assessment of the oxidative stress markers

Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured according to Ohkawa et al.32 Briefly, add 50 μL of Standard, Blank, or Sample per well. Immediately add 50 μL of Detection A working solution to each well. Gently tap the plate to ensure thorough mixing. Wash by filling each well with Wash Buffer, and let it sit for 1~2 min. Complete removal of liquid at each step is essential to good performance. Determine the optical density of each well at once, using a microplate reader set to 450 nm.

Superoxide dismutase enzyme activity (SOD) Cat No. CSB-E08555r was assessed according to Marklund and Marklund et al.,33 The enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. It is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all cells exposed to oxygen. Simply, Add 100 μL of Standard, Blank, or Sample per well. Cover with the adhesive strip (important step). Incubate for 1 h at 37 °C. Working solution may appear cloudy. Warm to room temperature and mix gently until solution appears uniform. Cover the microliter plate with a new adhesive strip. Keeping the plate away from drafts and other temperature fluctuations in the dark. Add 50 μL of Stop Solution to each well. Determine the optical density of each well within 30 min, using a microplate reader set to 450 nm.

CAT activity Cat. No. (CSB-E13439r) was estimated according to Aebi at 240 nm (Spectrophotometer, Bioespectro),34 it was expressed in (U/g). Briefly, Add 100 μL of standard and sample per well and follow the instructions and procedures as follows (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CAT assay procedure summary.

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx), Cat. No. (CSB-E12144r) activity was evaluated.35 Briefly, Add 100 μL of Standard, Blank, or Sample per well. Cover with the adhesive strip. Incubate for 2 h at 37 ° C, then remove the liquid of each well. Wash by filling each well with Wash Buffer (200 μL) using a squirt bottle, multi-channel pipette, manifold dispenser or autowasher. Determine the optical density using a microplate reader set to 450 nm.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and xanthine oxidase (XO) activities were measured by the method of Suzuki et al.36 and Litwack et al.,37 respectively. Total thiols level was evaluated according to Sedlak and Lindsay.38 Results were expressed in mM/g tissue.

Histological assessment of renal tissues

Fixed renal samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, the samples were processed by using hematoxylin/eosin staining procedures. Photomicrographs of the renal tissue samples were taken by light microscope (Olympus BX53 microscope) to view the stained slides.39

Immunohistochemical assessment of renal tissues

The obtained renal slices (4-m thickness) were blocked with 0.1% H2O2-containing MEOH for 15 min to disrupt the endogenous peroxidase and study apoptosis-related proteins. After blocking, the sections were treated at 4 °C with a polyclonal caspase-3 antibody. The color intensity of caspase-3 in the immunohistochemical sections was used to classify the intensity of immunostaining.

Masson’s trichrome stain study

Masson’s trichrome is a tricolor staining technique to differentiate cells from the adjoining connective tissue.40 This staining process results in red-stained keratin and muscle fibers, blue or green-colored collagen and bone structures, light-red or pink cytoplasm, and dark brown-to-black-stained cell nuclei. The trichrome staining was administered by immersing the fixed sample into Weigert’s iron hematoxylin.40

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed statistically as (mean ± SE).One-Way ANOVA is used. Valuation significant at P ≤ 0.05. It was assumed that the OBS-induced group had CAT levels of 2.17 ± 0.56, while the OBS + ORS + MEF group had CAT levels of 3.11 ± 0.75. Sample size is 50, with 10 in each group, at 80% power and 95% confidence level. OPEN EPI software was used to calculate this statistical ratio.41

Results

Effect of ORS, MEF, and their combination on renal function markers

The renal functions were tested using serum urea, uric acid, and creatinine. In the serum samples of the obesity-induced renal injury, the concentrations of urea and uric acid were both significantly higher than in the control group (Fig. 3). The levels of urea and uric acid were significantly lower in the OBS (Experimental induction of obesity) plus ORS group, and the OBS (Experimental induction of obesity) plus MEF group than in the control group. In the meantime, urea and uric acid levels were significantly lower in the obese animals treated with both ORS and MEF than in the corresponding group of obese animals.

Fig. 3.

Kidney function parameters of different treated groups either OBS group or OBS groups treated with either ORS, MEF or both. Significance values is abbreviated as follow: Ns: Non-significant, *Significant P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001 (highly significant value).

Creatinine levels were within normal limits in the control group and slightly above normal in the obese groups treated with ORS plus MEF (Fig. 3). Following numerous experiments involving kidney tissues, our previous studies42 revealed the normal values for creatinine, which was found to be higher in obese rats than in normal animals (P < 0.001).

Effect of ORS, MEF and its combination on antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation marker of the renal tissue homogenates

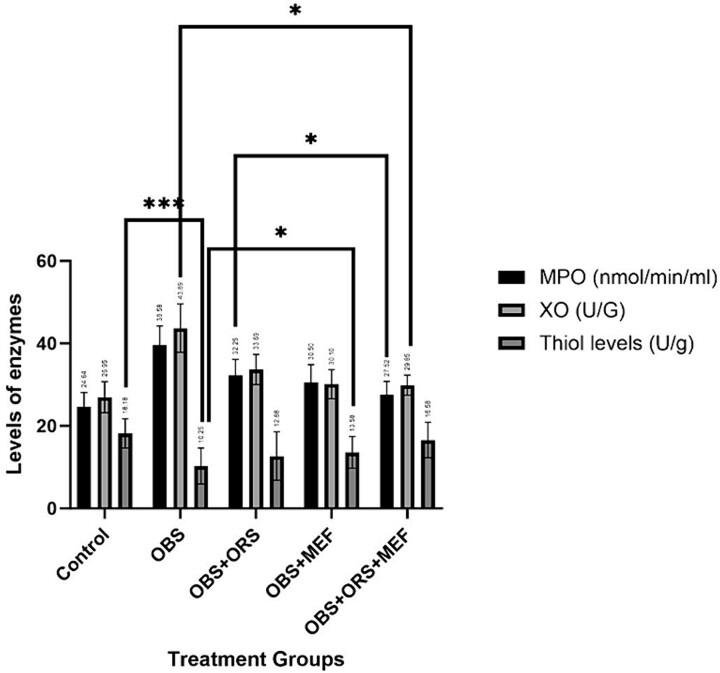

The study reveals that obese animals have higher MPO and XO levels compared to control animals, while thiol levels are significantly declined in obese rats as shown in (Fig. 4). The experimental obesity significantly increases MPO and XO activities and declines thiol levels (P < 0.05) as compared to the control group. Treatment with either ORS and/or MEF significantly decreases MPO and XO activities and increases thiol levels (P < 0.0001) compared to the OBS group alone. The results suggest that obesity can significantly impact the body’s nutrient levels.

Fig. 4.

Myloperoxidase, xanthine oxidase and thiol levels of different treated groups either OBS group or OBS groups treated with either ORS, MEF or both. Significance values is abbreviated as follow: Ns: Non-significant, *Significant P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001 (highly significant value).

The study examined the effects of ORS and/or MEF alone or in combination with OBS on kidney oxidative/antioxidant status. Results showed no significant changes in antioxidant parameters between the control and OBS plus ORS and MEF groups. OBS group increased lipid peroxidation levels and declined SOD, CAT, and GPx activities. Combination of ORS and MEF improved all enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) and non-enzymatic antioxidant (MDA) levels of different treated groups either OBS group or OBS groups treated with either ORS, MEF or both. Significance values is abbreviated as follow: Ns: Non-significant, *Significant P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001 (highly significant value).

Histological evaluation

The histological evaluation involved meticulous examination of preserved renal specimens utilizing the hematoxylin/eosin staining technique to provide insights into the tissue’s morphological characteristics. Under a light microscope, photomicrographs were captured, offering a detailed scrutiny of the renal tissue samples as shown in Fig. 6. In addition, renal slices, measuring 4 mm in thickness, underwent a brief immersion in a 0.1% solution of water and methanol for 15 min. This pretreatment aimed to enhance the investigation of apoptosis-related markers. Subsequently, both tissue sections underwent an extended overnight treatment at 4 °C with a caspase-3 antibody. The ensuing color intensity of caspase-3 in the immunohistochemical sections was pivotal for categorizing the immunostaining intensity Fig. 6 unfolds a comprehensive narrative.

Fig. 6.

A) The control group’s photomicrograph at 200× magnification unveiled normal glomeruli, afferent and efferent arterioles, capillary tuft, Bowman’s space, and normal tubules featuring intact lining cells and patent lumens. Contrastingly, B) the OBS group exhibited pathological changes at 400× magnification, encompassing reduced glomerulus size, marked capillary loop thickening, and tubular hypertrophy with a loss of normal polarity. C) The OBS plus ORS group displayed an elongated glomerulus with nearly normal architecture, albeit with increased glomerular distance. In contrast, D) the OBS plus MEF group showcased a normal glomerulus with some dilated glomerular distance and tubules. E) The OBS plus ORS and MEF group demonstrated near-normal glomeruli and dilated renal tubules, suggesting substantial restoration.

Figure 6 showed the following features (A) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental rat kidney (control group) showing normal glomeruli (normal afferent and efferent arterioles, normal capillary tuft and bowman’s space) (Orange arrow) and normal tubules with normal lining cells and patent lumen (H&EX200). (B) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental OBS group kidney showing marked reduced glomerulus (Blue arrow), and showed marked thickening of the capillary loops due to marked hyalinization and mesangial proliferation of the capillary loops leading to narrowing, nearly occlusion of bowman’s space with hyaline casts inside it (Orange arrow), the other glomerulus shows severe shrinkage, fibrosis and calcification of the capillary tuft (Orange arrow), most of the tubules show hypertrophy of the lining cells with loss of normal polarity (H&Ex400). (C) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental OBS plus ORS group kidney showing elongated golmerus with almost architecture but with distant glomerular distance (***) and normal tubules (white arrow) (H&EX400). (D) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental OBS plus MEF group kidney showing normal glomerulus (Orange arrow), with some dilated glomerular distance and some dilated renal tubules (yellow ***) (H&EX400). (E) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental OBS plus ORS and MEF group kidney showing almost normal glomeruli (Orange arrows), with dilated renal tubules (yellow ***) with almost normal architecture (H&EX400).

Immunohistochemical evaluation

Figure 7 clarified the immunohistochemical analysis, highlighting the expression of caspase-3. (A) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental normal control group showing negative immunoreactivity of caspase-3 in the tubular epithelial indicating absence of apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells (control group). (DAB chromogen, Meyer’s hematoxylin counterstain ×100). (B) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental mice kidney after administration of toxic material showing marked positive immunoreactivity of caspase-3 in the cytoplasm of the tubular epithelial cells and some immunoreactivity in glomeruli indicating marked apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells. (DAB chromogen, Meyer’s hematoxylin counterstain ×100). (C and D) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of kidney of either OBS plus ORS or OBS plus MEF showing moderate positive immunoreactivity of caspase-3 in the cytoplasm of the tubular epithelial cells and indicating moderate apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells with some positivity in glomeruli. (DAB chromogen, Meyer’s hematoxylin counterstain ×100). (E) photomicrograph of cross section of the renal cortex and medulla of kidney of OBS plus ORS and MEF group showing mild positive immunoreactivity of caspase-3 in the cytoplasm of the tubular epithelial cells and indicating mild apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells. (DAB chromogen, Meyer’s hematoxylin counterstain ×100).

Fig. 7.

A) The control group exhibited negative immunoreactivity, indicating an absence of apoptosis. In contrast, B) the OBS group displayed marked positive immunoreactivity, signifying significant apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells. C) The OBS plus ORS and D) OBS plus MEF groups exhibited moderate positive immunoreactivity, indicating a reduction in apoptosis, while E) the OBS plus ORS and MEF treated group demonstrated mild positivity, suggesting mild apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells.

Masson-trichrome evaluation

Moving to Fig. 8, the renal medulla’s toxicity was vividly portrayed in the OBS group’s photomicrograph. This toxicity was characterized by tubular hypertrophy, hydropic degeneration resulting in a star-shaped lumen or lumen occlusion, distortion of tubules, and the presence of red blood cells and hyaline casts within tubules. (A) (B) photomicrograph of a cross-section of the renal medulla of experimental OBS rat kidney showing toxicity in the form most of the tubules showed hypertrophy of the lining cells as a result of hydropic degeneration (water intoxication) compressing the lumen of the tubules into a star-shaped lumen or occlusion of the lumen and distortion of the tubules, red blood cell, and hyaline casts filling some of the tubules and occluding them and hyaline cast is obvious in one tubule. (Masson Trichrome ×400). (C and D) photomicrograph of cross-section of the renal cortex and medulla of experimental rat kidney of either OBS plus ORS or OBS plus MEF showing mild toxicity in the form of mesangial expansion resulting in narrowing of Bowman’s space (white thin arrow), some of the tubules showed hypertrophy of the lining cells as a result of hydropic degeneration (water intoxication) compressing the lumen of the tubules into star-shaped lumen or occlusion of the lumen (Double headed black arrow), and red blood cell casts in some of the tubules. (Masson Trichrome ×400). (E) OBS plus ORS and MEF treated group showing restoring mainly almost the renal medulla of experimental rat kidney showing normal tubules (White arrow) with back-to-back arrangement of the tubules, with red cell casts in the tubule-interstitial tissue (Double headed black arrow). (Masson trichrome ×400).

Fig. 8.

A) Control group showing normal tubules without toxicity. B) OBS group’s photomicrograph showed toxicity that was characterized by tubular hypertrophy and hydropic degeneration. C) The OBS plus ORS and D) OBS plus MEF groups displayed mild toxicity, with features like mesangial expansion, narrowing of Bowman’s space. E) The OBS plus ORS and MEF treated group showed restorative effects, with almost normal renal medulla featuring normal tubules.

Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the potential ameliorative effects of orlistat (ORS) and/or metformin (MEF), individually or in combination, on experimentally induced obesity (OBS) and its impact on renal oxidative stress in rats. The results revealed several significant findings about biochemical markers, enzymatic activities, and antioxidant levels. One noteworthy observation was the elevation of urea, uric acid, and creatinine levels in OBS rats, indicating impaired renal function associated with obesity. The increased activities of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and xanthine oxidase (XO) further highlighted the inflammatory and oxidative stress responses triggered by obesity. These findings align with existing literature demonstrating the detrimental effects of obesity on renal physiology.

Moreover, the study identified a substantial decline in the levels of non-enzymatic antioxidants, namely glutathione and thiol, in OBS rats compared to the normal group. This decline underscores the compromised antioxidant defense mechanisms in the kidneys of obese rats, contributing to heightened oxidative stress. The central focus of the discussion revolves around the combination of ORS and MEF, which exhibited a significant reduction in obesity-induced effects. The combination therapy effectively decreased lipid peroxidation (MDA levels) and enhanced intracellular antioxidant enzymes. This suggests a potential synergistic effect between ORS and MEF in mitigating oxidative stress associated with obesity.

The study’s strength lies in its multi-faceted approach, integrating biochemical analyses with histopathological and immunohistological evaluations. The congruence of findings across these diverse methodologies strengthens the robustness of the conclusions drawn from the study.

It is well known that obesity is a real a global health concern and it is highly associated with high morbidity and mortality. Obesity also elevates the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and many types of cancer. The combination of these metabolic syndrome can induce a lot of metabolic disturbances.43

However, the major risk induced via renal pathway which is induced by obesity, Contrary to the current findings, Tousson et al.44 revealed that treatment of obese rats with ORS revealed significant changes in creatinine and urea levels when compared with the obese rat’s group, their findings revealed an insignificant decline in creatinine and urea levels when compared with obese or treated obese rats with ORS groups, the obtained results greatly confirmed this concept and the novelty is the synergism between ORS and MEF in declining the biomarkers that revealed any damage in the kidney tissues like creatinine, urea and uric acid levels, as it appears statistically that ORS reduced both creatinine, urea in addition to uric acid levels by 25.28, 26.69, 22.68 and % as compared to OBS group. Meanwhile, MEF declined the mentioned parameters by 20.68, 22.59,and 20.22%, but obviously that both treatment of ORS and MEF significantly reduced the same mentioned parameters by 40.22, 38.69,and 42.22% as compared to OBS group, which best describe the synergistic effects between both ORS and MEF in amelioration of kidney function parameters. The current findings revealed the effect of ORS and MEF on improving renal functions especially the combined groups and this effect may be due to the ameliorative effect of MEF on renal functions and absorption of glucose and thus it may reduce the effect of ORS and thus the results were better than ORS alone and thus revealed the positive synergistic effect between both ORS and MEF.

The current findings greatly confirmed the previous finding of Kasturi et al.45 who concluded the synergistic effect of Berberine and/or ORS restored greatly the body weight and the organ weight, to a healthy weight comparable to those in age- and gender-matched controls and this may explain the current observation via reducing it’s expected side effects by other antioxidant agent.

A previous study of Hsu et al.,46 found that MEF may have an adverse effect on renal function in diabetics with type 2 DM and moderate chronic kidney disease, since the kidneys in those cases eliminate MEF mostly undigested, renal impairment may result in metformin accumulation and an elevation in MEF, which has been linked to lactic acidosis.47,48 Thus, The impact of MEF, ORS, and their combination on renal function markers in obesity-induced renal injury is investigated in this study and it confirmed that ORS synergistically mitigated and reduced the accumulation of MEF on renal tissues and produced this ameliorative effect.

Yi et al.,49 confirmed that patients with type 2 diabetes with reduced renal functions who continuing metformin treatment, they have lower risks of major kidney and cardiovascular events, which is in complete agreement with the current findings and increasing the effect synergistically in case of combination with ORS.

Michael et al.,50 found that ORS can reduce weight efficiently in patients with high fat diets and lowers the fat absorption through inhibition of triglycerides hydrolysis, this finding greatly supported the current findings by potent synergistic actions between ORS and MEF in improving renal functions, but in patients with fat-malabsorption syndromes, unabsorbed fat in the small bowel can produce calcium soaps, thus it can’t bind with calcium in the gut, and thus allow elevation of intestinal oxalate absorption, thus the current findings may explain the complementary and synergistic effect between MEF and ORS in alleviation of renal tissues damage, also MEF can mitigate ORS effects in malabsorption syndromes and can produce ameliorative effect.

As recently, attention has been focused on the use of the drug adjuvants to decline the dosage of administered drugs, minimize their side effects, improve the efficacy of therapeutic interventions, and greatly inhibited the diabetic complications Ayobami et al.51

The same current concept of synergism between therapeutic agents, previous study evaluated the benefits of using L-ergothioneine combined with MEF in renal dysfunctions associated with diabetes mellitus in experimental animal model. Significantly, L-egt exhibits renal-protective effects and improves the therapeutic outcomes when administered combined with MEF, thus, providing further support to the use of combination therapies to manage any disease related nephropathy.51

A another interesting explanation in this study with this novel therapeutic approach, It is well known that using MEF greatly decline insulin resistance and consequently it will improve the kidney functions as previously approved that the combination of L-egt and metformin improves glucose metabolism in diabetic rats, resulting from the highly improved efficacy of MEF to elevate the insulin sensitivity, thereby promoting glucose uptake and declined the hepatic gluconeogenesis pathway,52 this scientific concept greatly supported the current results that confirmed the novel synergism occurred between ORS and MEF in amelioration of renal functions and decline of oxidative injury resulted as consequence procedures of obesity.

Conclusion

The study investigates the ameliorative effects of ORS and MEF against obesity-induced renal injury in rat kidneys. It found that the combination therapy effectively mitigated the negative effects of obesity on renal function and oxidative stress. The study also revealed a decline in non-enzymatic antioxidants, indicating compromised antioxidant defense mechanisms. The combination of ORS and MEF emerged as a promising therapeutic approach, effectively reducing lipid peroxidation and enhancing intracellular antioxidant enzymes. Histopathological and immunohistological evaluations show minor kidney changes in rats treated with the therapy. While these results are promising, Further research is needed to understand long-term effects, safety, and mechanisms underlying the observed protective effects.

Contributor Information

Khadeejah Alsolami, Pharmacology and Toxicology Department, College of Pharmacy, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia.

Reham Z Hamza, Biology Department, College of Sciences, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-187).

Author contributions

Khadeejah Alsolami and Reham Z. Hamza contributed to this study equally. They are responsible for information collection, data organization, and manuscript writing, responsible for study design and manuscript reviewing.

CRediT authorship contribution statement: Khadeejah Alsolami and Reham Z. Hamza: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Data curation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration.

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-187).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors do not possess any financial or other competing interests that require disclosure.

Data availability

All data available as described in the article.

References

- 1. Suleiman JB, Nna VU, Zakaria Z, Othman ZA, Bakar ABA, Mohamed M. Obesity-induced testicular oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis: protective and therapeutic effects of orlistat. Reprod Toxicol. 2020:95:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leisegang K, Henkel R, Agarwal A. Obesity and metabolic syndrome associated systemic inflammation and the impact on the male reproductive system. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019:82(5):e13178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chin-Yu L, Ting-Chia C, Shyh-Hsiang L, Sheng-Tang W, Tai-Lung C, Chih-Wei T. Metformin ameliorates testicular function and spermatogenesis in male mice with high-fat and high-cholesterol diet-induced obesity. Nutrients. 2020:12(7):1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med. 2012:9(12):e1001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poongothai J, Gopenath TS, Manonayaki S. Genetics of human male infertility. Singapore Med J. 2009:50(4):336–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar N, Singh AK. Trends of male factor infertility, an important cause of infertility: a review of literature. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015:8(4):191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Wright DL, Meeker JD, Hauser R. Body mass index in relation to semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, and serum reproductive hormone levels among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2009:93(7):2222–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hofny ER, Ali ME, Abdel-Hafez HZ, Kamal EE-D, Mohamed EE, El-Azeem HGA, Mostafa T. Semen parameters and hormonal profile in obese fertile and infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2010:94(2):581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mulligan T, Frick MF, Zuraw QC, Stemhagen A, McWhirter C. Prevalence of hypogonadism in males aged at least 45 years: the HIM study. Int J Clin Pract. 2008:60(7):762–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Wakf AM, Elhabibi E-SM, El-Ghany EA. Preventing male infertility by marjoram and sage essential oils through modulating testicular lipid accumulation and androgens biosynthesis disruption in a rat model of dietary obesity. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci. 2015:2(3):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferigolo P, Ribeiro de Andrade M, Camargo M, Carvalho V, Cardozo K, Bertolla R, Fraietta R. Sperm functional aspects and enriched proteomic pathways of seminal plasma of adult men with obesity. Andrology. 2019:7(3):341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plessis D, Cabler S, McAlister DA, Sabanegh E, Agarwal A. The effect of obesity on sperm disorders and male infertility, nature reviews. Urology. 2010:7(3):153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thaler MA, Seifert-Klauss V, Luppa PB. The biomarker sex hormone-binding globulin–from established applications to emerging trends in clinical medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015:29(5):749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thundathil JC, Dance AL, Kastelic JP. Fertility management of bulls to improve beef cattle productivity. Theriogenology. 2016:86(1):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bellastella G, Menafra D, Puliani G, Colao A, Savastano S. How much does obesity affect the male reproductive function? Int J Obes Suppl. 2019:9(1):50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal A, Aponte-Mellado A, Premkumar BJ, Shaman A, Gupta S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012:10(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Won Y-J, Kwon GE, Lee HS, Choi MH, Lee J-W. The effect of Orlistat on sterol metabolism in obese patients. Front Endocrinol. 2022:13:824269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, Foreyt JP, Halsted CH, Heber D, Heimburger DC, Lucas CP, Robbins DC, Chung J, et al. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with Orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999:281(3):235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hollander PA, Elbein SC, Hirsch IB, Kelley D, McGill J, Taylor T, Weiss SR, Crockett SE, Kaplan RA, Comstock J, et al. Role of Orlistat in the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes. A 1-year randomized double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 1998:21(8):1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwon YJ, Lee H, Nam CM, Chang HJ, Yoon YR, Lee HS, Lee JW. Effects of Orlistat/phentermine versus phentermine on vascular endothelial cell function in obese and overweight adults: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021:14:941–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu S, Lin X, Tao M, Chen Q, Sun H, Han Y, Yang S, Gao Y, Qu S, Chen H. Efficacy and safety of orlistat in male patients with overweight/obesity and hyperuricemia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2024:23(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsushima Y, Nishizawa H, Tochino Y, Nakatsuji H, Sekimoto R, Nagao H, Shirakura T, Kato K, Imaizumi K, Takahashi H, et al. Uric acid secretion from adipose tissue and its increase in obesity. J Biol Chem. 2013:288(38):27138–27149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Choi HK. The serum urate-lowering impact of weight loss among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile: the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010:49(12):2391–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schcolnik-Cabrera A, Chávez-Blanco A, Domínguez-Gómez G, Taja-Chayeb L, Morales-Barcenas R, Trejo-Becerril C, Perez-Cardenas E, Gonzalez-Fierro A, Dueñas-González A. Orlistat as a FASN inhibitor and multitargeted agent for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018:27(5):475–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Valladales-Restrepo LF, Sánchez-Ramírez N, Usma-Valencia AF, Gaviria-Mendoza A, Machado-Duque ME, Machado-Alba JE. Effectiveness, persistence of use, and safety of orlistat and liraglutide in a group of patients with obesity. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023:24(4):535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feng X, Lin Y, Zhuo S, Dong Z, Shao C, Ye J, Zhong B. Treatment of obesity and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease with a diet or orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023:117(4):691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song J, Ruan X, Gu M, Wang L, Wang H, Mueck AO. Effect of orlistat or metformin in overweight and obese polycystic ovary syndrome patients with insulin resistance. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018:34(5):413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Didangelos TP, Thanopoulou AK, Bousboulas SH, Sambanis CL, Athyros VG, Spanou EA, Dimitriou KC, Pappas SI, Karamanos BG, Karamitsos DT. The ORLIstat and CArdiovascular risk profile in patients with metabolic syndrome and type 2 DIAbetes (ORLICARDIA) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004:20(9):1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rachelle H, Zarzour F, Ghezzawi M, Saadeh N, Bacha DS, Al Jebbawi L, Marlene C, Mantzoros CS. The impact of metformin on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024:26(5):1850–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamza RZ, Alsolami K. Ameliorative effects of Orlistat and metformin either alone or in combination on liver functions, structure, immunoreactivity and antioxidant enzymes in experimentally induced obesity in male rats. Heliyon. 2023:9(8):e18724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alsolami K, Hamza RZ. Orlistat and metformin effectively reduce pancreatic dysfunction, insulin resistance and blood glucose levels in male rats experimentally induced with obesity. Int J Pharmacol. 2024:20(5):726–734. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979:95(2):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marklund SL. Expression of extracellular superoxide dismutase by human cell lines. Biochem J. 1990:266(1):213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aebi H. Oxygen radicals in biological systems - catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984:105(1947):121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hafeman DG, Sunde RA, Hoekstra WG. Effect of dietary selenium on erythrocyte and liver glutathione peroxidase in the rat. J Nutr. 1974:104(5):580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suzuki K, Ota H, Sasagawa S, Sakatani T. Fujikura T, assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal Biochem. 1983:132(2):345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Litwack G, Bothwell JW, Williams JN, Elvehjem CA. A colorimetric assay for xanthine oxidase in rat liver homogenates. J Biol Chem. 1953:200(1):303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. J Anal Biochem. 1968:25(1):192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 6th ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foot NC. The Masson trichrome staining methods in routine laboratory use. Stain Technol. 1933:8(3):101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dean A, Sullivan K, Soe M. OpenEpi: Open source epidemiologic statistics for public health. 2013. [Accessed 2022 March 2]. SCIENCE OPEN.com, research+ publishing network. Available online: https://www.OpenEpi.com.

- 42. El-Shenawy NS, Hamza RZ, Al-Salmi FA, Al-Eisa RA. Evaluation of the effect of nanoparticles zinc oxide/Camellia sinensis complex on the kidney of rats treated with monosodium glutamate: antioxidant and histological approaches. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2019:20(7):542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004:89(6):2595–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tousson E, Massoud A, Salem A, Fatoh SA. Nephrotoxicity associated with Orlistat in normal and obese female rats. J Biosci Appl Res. 2018:4(3):193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kasturi B, Moumita N, Choudhury Y. Berberine is as effective as the anti-obesity drug Orlistat in ameliorating betel-nut induced dyslipidemia and oxidative stress in mice. Phytomed Plus. 2021:1(3):100098. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wei-Hao H, Pi-Jung H, Pi-Chen L, Szu-Chia C, Mei-Yueh L, Shyi-Jang S. Effect of metformin on kidney function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and moderate chronic kidney disease. Oncotarget. 2018:9(4):5416–5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2011:34(6):1431–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014:312(24):2668–2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yi Y, Kwon EJ, Yun G, et al. Impact of metformin on cardiovascular and kidney outcome based on kidney function status in type 2 diabetic patients: a multicentric, retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2024:14(1):2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Michael MB, Amit XG, Matthew AW. Does orlistat cause acute kidney injury? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2012:3(2):53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ayobami D, Channa ML, Nadar A. L-ergothioneine and its combination with metformin attenuates renal dysfunction in type-2 diabetic rat model by activating Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021:141:111921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Agius L, Ford B, Chachra S. The metformin mechanism on gluconeogenesis and ampk activation: the metabolite perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2020:21(9):3240–3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data available as described in the article.