Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

Childhood cancer survivors may experience complex health issues during transition and long-term follow-up (LTFU); therefore, high-quality healthcare is warranted. Care coordination is one of the essential concepts in advanced healthcare. Care coordination models vary among childhood cancer survivors in transition and LTFU. This study aimed to identify care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors in transition and LTFU and synthesise essential components of the models.

Design

This scoping review was guided by the methodological framework from Arksey and O’Malley and was reported with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. A systematic literature search was conducted on six databases using possible combinations of terms relevant to childhood cancer survivors, transition/LTFU and care coordination model. Data were analysed by descriptive and content analysis.

Data sources

The literature search was first conducted in May 2023 and updated in May 2024. Six databases including Medline, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL and Cochrane Library were searched; meanwhile, a hand search was also conducted.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Studies relevant to describing any models, interventions or strategies about care coordination of transition or LTFU healthcare services among childhood cancer survivors were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently screened and included studies. Basic information as well as care coordination model-related data in the included studies were extracted. Descriptive summary and content analysis were used for data analysis.

Results

In the 20 545 citations generated by the search strategy, seven studies were identified. The critical determinants of the models in the included studies were the collaboration of the multidisciplinary team, integration of the navigator role and the provision of patient-centred, family-involved, needs-oriented clinical services. The main functions of the models included risk screening and management, primary care-based services, psychosocial support, health education and counselling, and financial assistance. Models of care coordination were evaluated at patient and clinical levels. Based on this review, core concepts of successful care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors in transition or LTFU were synthesised and proposed as the ‘3 I’ framework: individualisation, interaction and integration.

Conclusion

This scoping review summarised core elements of care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU. A proposed conceptual framework to support and guide the development of care coordination strategies for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU care was developed. Future research is needed to test the proposed model and develop appropriate care coordination strategies for providing high-quality healthcare for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU.

Keywords: Nursing Care, Paediatric oncology, Review

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This review conducted a comprehensive search across multiple databases to identify studies on the coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and long-term follow-up.

We used the methodological framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley to guide this review, which resulted in a well-organised and structured approach.

The review summarised the key determinants of the care coordination models and proposed a conceptual framework to guide the development of care coordination strategies in clinical practices.

This review only considered English-language articles, and most studies were from Western countries, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

Introduction

Childhood cancer survivors refer to individuals who received a cancer diagnosis between the ages 0 and 19 years.1 With increasing survival rates for this population, it is estimated that approximately 85% of patients diagnosed with cancer in childhood and adolescence will become long-time cancer survivors.2 However, childhood cancer survivors continue to face a variety of adverse physical, psychological and social effects caused by cancer and relevant treatments.3,6 In addition, they also face unique challenges during the survivorship phase, such as the healthcare transition from paediatric-centred to adult-oriented care.7 Therefore, offering high-quality care coordination during the transition and long-term follow-up (LTFU) to childhood cancer survivors is a high priority.8 9

Care coordination is described as the organisation of healthcare activities to link specific patients with a wide range of comprehensive healthcare services, which is considered an essential component of patient-centred care.10,13 It aims to effectively coordinate the fragmented and discontinued healthcare services to promote continuity, accessibility, quality and cost-effective care.12 Implementing care coordination has been shown to improve health-related outcomes, including decreasing hospitalisations and complications, enhancing symptom management, and increasing patient satisfaction.14 Additionally, care coordination can also improve healthcare system performance metrics such as cost-effectiveness and service quality.15,18 Given the number of interactions with various healthcare services, childhood cancer survivors with complex health needs and their families may particularly benefit from care coordination.19

Of note, care coordination strategies varied due to the differences in paediatric patients’ health conditions, local healthcare system and contexts.19 Several previous studies have attempted to summarise features in care coordination for both paediatric and adult patients with chronic diseases or adult patients with complex health needs. Key features highlighted in these studies included multiple stakeholders (eg, patients, families and healthcare providers), interdependence, interaction and communication among participants and appropriate healthcare delivery.11 13 20 However, evidence for care coordination strategies that specifically target childhood cancer survivors in transition and LTFU was lacking.

Therefore, this scoping review was conducted with a threefold aim: (1) to identify care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU, (2) to synthesise key elements of the models and (3) to evaluate and summarise the performance of the models in clinical practice. Identifying and summarising the critical determinants of care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors' transition and LTFU is critical to optimising care coordination strategies for this patient population.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the development, or implement, or reporting, or dissemination of this study.

This scoping review was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guideline.21 The methodology of this scoping review was guided by the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley.22 The framework consists of five stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results.22 This review was conducted following these five stages.

Identifying research questions

This review aimed to identify the care coordination models applied in childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU care and to synthesise the significant features of these models. We determined the relevant research questions based on the review’s aims with three research questions proposed.

Question 1: What are the essential components of the care coordination models for transition and LTFU care of childhood cancer survivors? This question focuses on summarising the features and main tasks of the relevant (existing) care coordination models.

Question 2: Which outcomes are used to evaluate the performance of the care coordination models?

Question 3: What common elements are reflected in the care coordination models for transition and LTFU care of childhood cancer survivors?

These three questions are addressed in this review. In addition, based on the findings, a conceptual paradigm has been developed to show how care coordination strategies can be tailored to meet the needs of this specific patient population.

Identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

The systematic literature search was first conducted in May 2023 and updated in May 2024 across six databases (Medline, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL and Cochrane Library) to identify studies published in English without limitation on publication date. Search terms mainly included “child,” “cancer,” “transition,” “follow up” and “care coordination,” which were searched using all possible combinations with Medical Subject Headings. Hand searches of relevant websites, journals and reference lists of relevant articles were also conducted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were (1) focusing on childhood cancer survivors and (2) describing any models, interventions or strategies about care coordination of transition or LTFU healthcare services among childhood cancer survivors. Conference abstracts, study protocols and ongoing trials (without reported results) were excluded.

Study selection

Once the final search strategy was determined, EndNote V.X9 was used to manage the searched studies to remove duplicates. Then, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies using the inclusion and exclusion criteria as the first step. After excluding ineligible studies, the two reviewers read the full text of the remaining studies to identify relevant studies according to the criteria. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus or by a senior researcher (as the third reviewer).

Charting the data

Data from the included studies were extracted using standardised forms developed for this project. The basic information of the studies was descriptively summarised, including the author, publication year, country, target populations, study context and the care coordination model described in the study. The summary information of care coordination models, including their components, functions and outcomes for evaluation, was also extracted.

Data analysis

Descriptive summary and content analysis were used for data analysis. The extracted information from the studies and care coordination models was descriptively summarised. Content analysis was conducted to collect and draw conclusions from the information relevant to the review questions.

Results

Study selection

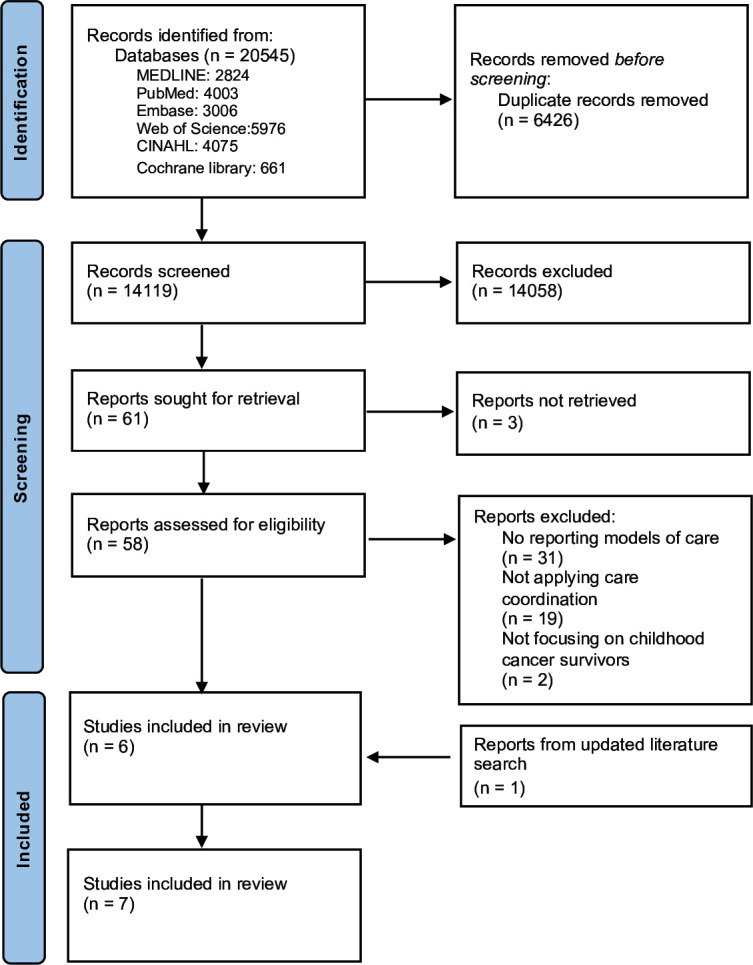

During the initial search, 20 545 studies were identified from the 6 databases, and after removing 6426 duplications, a total of 14 119 titles and abstracts were screened by 2 independent researchers. Of these, 61 studies were thoroughly reviewed with full text and 6 were included (figure 1). Additionally, the updated search resulted in one more study included in the review. Hence, a total of seven studies were ultimately included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 shows the key information of all included studies. The seven included studies were published between 2004 and 2020. All studies were conducted in developed countries, with five in the USA, one in the Netherlands and one in Australia. From these studies, a total of seven care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU were identified: the Tactic Clinic Model,23 the Innovative Clinic Model,24 the St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care,25 the Multidisciplinary Model of Care,26 the Long-Term Follow-Up Programme,27 the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model28 and the Re-Engage Model.29

Table 1. Summary of the included studies.

| Author and year | Country | Targeted populations | Context | Care coordination model |

| Overholser et al23 2015 | USA | Adult survivors of childhood cancer | Clinic | The Tactic Clinic Model |

| McClellan et al24 2015 | USA | Adult survivors of childhood cancer | Clinic | The Innovative Clinic Model |

| Hudson et al25 2004 | USA | Childhood cancer survivors | Clinic | The St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care [The After Completion of Therapy (ACT) Clinic] |

| Carlson et al26 2008 | USA | Childhood cancer survivors | Clinic | The Multidisciplinary Model of Care |

| Friedman et al27 2006 | USA | Survivors of childhood cancer | Clinic or community based, or combined | The Long-Term Follow-Up Programme |

| Loonen et al28 2016 | Netherlands | Survivors of childhood and adult-onset cancer | Clinic | The Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model |

| Signorelli et al29 2020 | Australia | Survivors of childhood cancer | An e-health intervention | The Re-Engage Model |

Components of the care coordination models

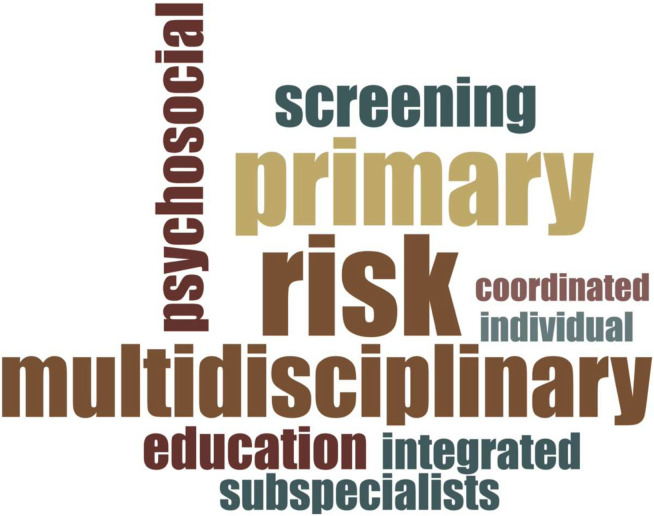

Using NVivo V.12.0 software, we first identified a total of 10 most frequently used words among all care coordination models in the included studies (figure 2) to preliminarily explore their common elements. The 10 words were risk, primary, multidisciplinary, screening, psychosocial, education, integrated, subspecialists, individual and coordinated. Then, we summarised the features and care tasks of the care coordination models in the context of transition and LTFU care for childhood cancer survivors. Table 2 demonstrates the summary information.

Figure 2. Word cloud of top 10 most frequently used words of the care coordination models.

Table 2. Care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU included in this review.

| Model | Settings | Structure of the model | Main care tasks | Evaluation |

|

Long term follow-up through to young adulthood | Multidisciplinary team (general internist, clinical health psychologist, an oncology survivorship nurse educator) and clinic nurse coordinator |

|

Patients’ response rate and Clinical referrals |

|

Transition from hospital to medical centre | Nurse navigator and a primary care physician in the adult setting and paediatric survivorship workgroup (paediatric and adult oncologists, internal medicine physicians, specialists, administrators, psychosocial and supportive care providers and organisations, and clinical researchers) |

|

Patient-reported outcomes (access to services, satisfaction with care, patient distress and patient access to treatment) and clinical outcomes (referral, patients’ adherence, length of waiting time) |

|

Transition from paediatric oncology to community providers | Nurse practitioner and social worker and clinic nurse and Subspecialty provider and Physician |

|

Not report |

|

Long-term follow-up | Subspecialists (oncology, endocrinology, cardiology, pulmonology, psychology, cardiology, nutrition) and nursing roles (nurse coordinator, outpatient clinic nurse, advanced practice nurse, research nurse) |

|

Patient (access to services) and Healthcare provider (efficiency and effectiveness of services) and Institution (referrals, patients’ satisfaction) |

|

Long-term follow-up | Multidisciplinary team: physician, nurse coordinator, medical social worker and other subspecialists |

|

Not report |

|

Regular long-term follow-up | Survivorship clinic/coordination and medical expert team and psychosocial expert team and consultants |

|

Patient (health outcomes, satisfaction) and clinic (cost-effectiveness) |

|

Long-term follow-up | A distance-delivered live intervention: including a clinical nurse consultant, a specially constituted MDT (including paediatric and adult oncologists, nurse, GP, psychologist, social worker) |

|

Survivors’ health-related self-efficacy, health behaviours, information needs, satisfaction with care and emotional well-being |

GPgeneral practitionerMDTmultidisciplinary team

Features of the care coordination models

Three features of care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU were generalised, including the collaboration of the multidisciplinary team, involvement of a navigator/coordinator and provision of patient-centred, family-involved and needs-oriented healthcare services.

Collaboration of the multidisciplinary team

The collaboration of multidisciplinary teams of health professionals was a significant feature in all care coordination models. All models emphasised the need for cooperation across multidisciplinary teams to provide comprehensive health services for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU. Furthermore, in one model, the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model, the multidisciplinary collaboration extended beyond a single healthcare facility to include collaborations across institutions, clinical settings and organisations.28

Regarding the structure of the multidisciplinary teams, the models typically involved physicians, multiple subspecialists (eg, in paediatric oncology, endocrinology, cardiology, psychology, nutrition), clinical nurses and social workers. These professionals were responsible for providing physical, and psychological care services, as well as social support for childhood cancer survivors. In addition, two care coordination models included paediatric educators and subspecialty consultants to provide relevant health education or counselling plans.24 25

Involvement of a navigator or coordinator

Another key feature of the care coordination models was the involvement of a navigator or coordinator. Since multiple healthcare professionals and services were involved in one childhood cancer survivor’s care, matching each survivor to the appropriate services in an efficient manner was a commonly described challenge. Therefore, introducing a dedicated role responsible for coordinating various services and patient navigation was a feature of the models. The navigator or coordinator typically played the role of ‘link’, connecting childhood cancer survivors and their families to various healthcare professionals and services. In the Innovative Clinic Model, the navigator needed to contact relevant subspecialists in advance.24 In the Multidisciplinary Model of Care, the coordinator was described as the central connection among the survivors, families and healthcare providers, overseeing the management and coordination of the care plan.26

Regarding the qualifications of the navigators or coordinators, four of the five models reported that the role was undertaken by nurses24 26 27 29 while one model indicated that either physicians or nurses could be responsible for the coordination.28 In addition, one model specified that the navigator needed to have social work expertise.23

Provision of patient-centred, family-involved and needs-oriented healthcare services

Providing patient-centred, family-involved and needs-oriented healthcare services was another key feature of the included care coordination models. Patient-centred care emphasises that the patient’s individual health-related needs should be the central focus.30 31 In this review, two care coordination models, the Long-Term Follow-Up Programme27 and the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model,28 highlighted a focus on patient’s needs and providing tailored needs-oriented healthcare services.

Two models emphasised the integration of family concerns, in addition to the needs of the survivors. The Innovative Clinic Model emphasises communication and collaboration between healthcare providers and patients and their families.24 Similarly, the Multidisciplinary Model of Care included both childhood cancer survivors and their families’ needs as targets for the healthcare services.26

Care tasks provided by the care coordination models

We identified and summarised five essential care tasks provided by the care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU. These care tasks included risk screening and management, primary care-based services, psychosocial support, health education and counselling, and financial assistance.

Risk screening and management

Cancer survivors are at risk of complications, comorbidities and reduced quality of life, due to the impacts of cancer and treatments.632,34 To prevent these severe health issues, providing a risk-based care plan instead of services after specific symptoms appear was an important function of care coordination.32 We found that most care coordination models in this review listed risk management as an essential care task and highlighted that healthcare services provided in models were risk based. The Long-Term Follow-Up Programme suggested that classified risk reduction and mitigation related to developing late effects as one of the model’s core functions.27 In the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model, a risk-based screening service for cancer treatment-related late effects was provided.28 The Tactic Clinic Model emphasised providing a risk-based survivorship care plan, and a risk assessment service was included for childhood cancer survivors.23 The St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care also described comprehensive risk-based services for childhood cancer survivors, including clinical risk assessment and cancer-related risk counselling.25 In the Multidisciplinary Model for Care, risk-based screening and counselling services were provided to identify survivors already or possibly affected by chronic side effects of cancer treatment.26

Primary care-based services

Another important care task the care coordination models provided was the primary care-based services. Primary care was defined as the integrated and comprehensive healthcare services to address a majority of healthcare needs,35 emphasising providing services based on the patient’s individual medical and treatment history and living contexts rather than a specific disease only.36 The Tactic Clinic Model aimed to provide primary care-based services for adult childhood cancer survivors. It integrated the local primary care-based resources into care coordination strategies to provide LTFU care services for childhood cancer survivors.23 A similar feature was found in the Re-Engage model, where personalised care plans were developed for each survivor, and those with low-and medium-risk survivors were referred to primary services.29 The Innovative Clinic Model integrated primary care and survivorship care into the transitional care services for adult survivors of childhood cancer to meet their comprehensive health needs.24 In the Multidisciplinary Model, the strategy of sharing care plans was applied, in which primary care providers were enrolled to support the transition of childhood cancer survivors.26 In the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model, a multidisciplinary and risk-based approach was applied to integrate care for cancer survivors. For survivors with low risk of cancer treatment-related health problems, primary care physicians were assigned to be involved in their long-term care services, including follow-up and first-line treatment.28

Psychosocial support

Both the diagnosis of cancer and the effects of cancer treatment during critical periods of growth and development can impact childhood cancer survivors and result in various types of psychosocial issues.37 Evidence shows that providing effective psychosocial support had increased positive effects among cancer survivors, including improving their overall health conditions and health-related quality of life.38 In fact, the term ‘psychosocial’ was listed in the top 10 most frequently used words describing the care models. In the Long-Term Follow-Up Programme, addressing survivors’ psychosocial issues was emphasised as one of the model’s main functions.27 Likewise, in both the Tactic Clinic Model and the St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care, every survivor receives a relevant assessment by a clinical health psychologist, and a targeted plan and recommendations for psychosocial support.23 25 In the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model, a team of psychosocial experts is involved in a comprehensive evaluation of each survivor’s psychosocial needs.28 Given the increased risk of complex psychosocial problems, the Innovative Clinic Model included psychosocial support in the model’s core healthcare services.24

Health education and counselling

All models emphasised the provision of health education and counselling as an essential care task of their care coordination services. The term ‘education’ was also one of the top ten frequently used words in describing the care models. In five of the care coordination models, the nurse coordinator typically delivered health education for childhood cancer survivors.23,2629 In the Long-Term Follow-Up Programme model, health education and counselling were provided cooperatively by the nurse, physician and medical social worker together.27

Financial assistance

The review identified that some of the care coordination models listed providing financial assistance as one of the tasks within their care coordination activities.25,27 Specifically, the models that highlighted financial assistance noted that obtaining adequate health insurance and securing employment were significant challenges faced by young adult childhood cancer survivors. Therefore, the financial assistance provided in these models focuses primarily on guidance and support related to insurance and employment-related issues, with social workers or nurses providing this support.

Outcomes for evaluating the performance of models

Several care coordination models reported the evaluation of models’ performance based on outcomes at the patient level and clinical level, including childhood cancer survivors’ health conditions, health behaviour, health-related quality of life, specialist referrals, cost-effectiveness, and patients’ and their families’ satisfaction.

The Tactic Clinic Model reported with the implementation of their care coordination activities, more childhood cancer survivors were transferred to this clinic, and a significant proportion of them showed adherence to continue in LTFU care.23 The Innovative Clinic Model used patients’ health conditions, adherence to treatment and follow-up, and satisfaction levels to assess the results of the implementation of their care coordination strategies.24 The Re-Engage Model assessed survivors’ satisfaction and health-related self-efficacy.29 In the St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care, the patients’ assessment included childhood cancer survivors’ health conditions, health behaviour and health-related quality of life.25 The Multidisciplinary Model of Care demonstrated improvements in several patient-related outcomes, including health-related outcomes, participation in follow-up care and levels of satisfaction of patients and families.26 The Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model proposed that cost-effectiveness should be included as an outcome in the model’s evaluation. Meanwhile, the components of this model were reported to be cost-effective in reducing the caring costs.28

Common elements of the care coordination models

Based on these findings, we concluded the common elements of the care coordination models for transition or LTFU healthcare services among childhood cancer survivors. The commonness was synthesised as the ‘3I’s’: individualisation, interaction and integration.

Individualisation

The first common element reflected in the care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition or LTFU healthcare was individualisation. Individualised services based on each survivor’s specific disease and treatment history were emphasised across these models. The Long-Term Follow-Up Programme emphasised that due to the wide range of health-related needs among survivors, a one-size-fits-all approach was not appropriate.27 The Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model underlined that a personalised model was developed to provide individualised follow-up for each patient.28 The Re-Engage Model also emphasised developing a personalised follow-up plan for their patients.29 In the Tactic Clinic Model, each patient’s treatment history, current health status and special health concerns would be assessed, and a care plan would be developed based on the individual’s needs.23 In the Innovative Clinic Model, each adult survivor would receive a unique template and a scheduling script from the clinic, to record their individual needs and arrange the targeted healthcare services.24 In the St. Jude Model of Long-Term Survivor Care, each childhood cancer survivor received an individual summary of their disease history and treatment mode and individualised health counselling at the time of transition from specialised paediatric cancer care to community healthcare.25 Similarly, in the Multidisciplinary Model of Care, a shadow chart was adopted, in which each survivor’s disease and treatment history was recorded to guide the providers in implementing relevant care activities.26

Interaction

The second common element of the care coordination model was interaction. The interaction included both verbal and nonverbal behaviours,39 and it primarily referred to interactions between childhood cancer survivors, families, and multiple healthcare professionals and specialists. In some models, interaction also refers to interactions between various healthcare providers involved in care. For example, the Tactic Clinic Model included a training discussion between medical staff and interns on providing appropriate healthcare for childhood cancer survivors.23 The Multidisciplinary Model of Care included a non-verbal interaction of communication through the medical record chart, which provided the opportunity for healthcare staff to review and build on each other’s care plans.26

Integration

The third element of the care coordination model was integration. Based on the reviewed care coordination models, we found that integration was reflected in the comprehensive nature of the healthcare services provided to childhood cancer survivors, which could be classified into two aspects: not limited to one single healthcare provider and focusing on meeting patients’ overall health needs. First, to reduce the fragmentations of care involving many healthcare professionals,40 the care coordination models provided continuity of care for childhood cancer survivors. In these models, various healthcare professionals were involved in the survivors’ care services, cooperating to contribute to a comprehensive care plan for each survivor.23 26 27 Second, the care coordination models in this review did not focus on a single health issue but instead aimed to address the survivors’ complex health needs using a holistic approach.23 24 26 Moreover, the Personalised Cancer Survivorship Care Model proposed a two-directional integration of care for childhood cancer survivors: vertical and horizontal integration. The vertical integration of care refers to the collaboration among different levels of healthcare organisations while the horizontal integration of care refers to the collaboration among different healthcare providers within one organisation.28 Across these models, shared decision-making was adopted to achieve integration of care among various healthcare professionals and patients.28

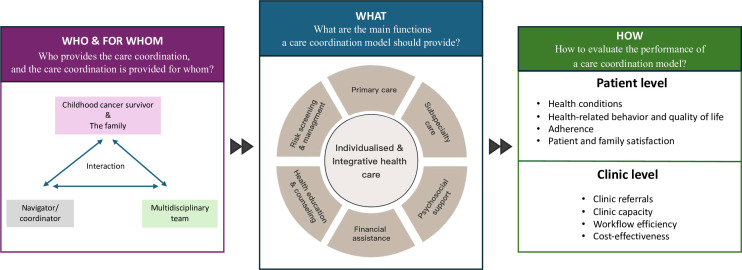

Conceptual framework

Figure 3 illustrates a proposed conceptual framework to support and guide the development of care coordination strategies for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU care. This framework was generated based on the findings of the research questions addressed in this review. The proposed conceptual framework could be used to guide the development of care coordination strategies and interventions specifically tailored for childhood cancer survivors’ transition into clinical practice, However, the authors note that this framework would require further testing and validation in future studies before it can be widely applied.27

Figure 3. A proposed conceptual framework of care coordination about childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU care. LTFU, long-term follow-up.

Discussion

This review provided evidence on the characteristics and application of care coordination models among childhood cancer survivors for their transitions and LTFU. A total of seven care coordination models were included; based on the analysis of these models, three questions of this review including features, care tasks and outcomes of the models were summarised. Features mainly included the collaboration of the multidisciplinary team, the inclusion of a navigator/coordinator role, and providing patient-centred, family-involved and needs-oriented healthcare services. The main care tasks of the care models in this review included risk screening and management, primary care-based services, psychosocial support, health education and counselling, and financial assistance. Outcomes commonly used to evaluate the performance of the models in this review were patients’ health-related and clinical. These findings provided the groundwork to synthesise three common elements of the care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU, including ‘individualisation’, ‘interaction’ and ‘integration’.

Care coordination: individualised and integration of care services

To provide healthcare services based on an individual’s unique health needs, various healthcare providers are involved in the care plan of childhood cancer survivors. This is particularly important as with the burden of risks and late effects survivors endure, it is difficult to require survivors to flight for the care they need.41 Therefore, to avoid fragmented care, the integration of multiple services to meet an individual’s needs was essential.40 In this review, we found that ‘integrated’ was one of the most frequently used words of all six care coordination models. Integration in the care coordination models served three crucial purposes: providing the continuity of care, addressing complex health needs, and enabling vertical and horizontal integration. These three aspects of integrated care are consistent with the definitions of integration in healthcare.42 Previous studies have reported that the integration of services in care coordination among paediatric patients proved effective in decreasing the costs and improving the patient and their family’s care experience.43 Consistent findings in this review suggest that the cost-effectiveness of care services among childhood cancer survivors improved after implementing care coordination models.28 Similarly, the Multidisciplinary Model of Care in this review highlights continuity rather than fragmentation of care for childhood cancer survivors, and survivors and their families reported a high level of satisfaction with this care coordination model.26

Multidisciplinary team approach: collaboration for care coordination

In this review, the use of a multidisciplinary team approach was a noteworthy feature of the care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU. Due to the impact of cancer, its treatment and developmental changes, childhood cancer survivors experience diverse and complex healthcare needs that necessitate a multidisciplinary team-based approach.44 45 Physicians, nurses, subspecialists and social workers were commonly represented in the multidisciplinary team, collaborating in the decision-making process for the individualised care plan based on the healthcare needs of childhood cancer survivors. In this review, the Multidisciplinary Model of Care reported that clinical efficiency was improved by applying the multidisciplinary approach while patient-centred care was also promoted.26 The results echoed previous studies, which have shown that applying a multidisciplinary, needs-oriented care coordination model can enhance the efficiency and quality of patient treatment and care.46 Compared with care provided by a single physician, collaboration among healthcare staff in a multidisciplinary team has been demonstrated to be more effective in improving patient management.46 47 Despite this, it is worth noting that the high level of communication, instruction and data sharing required between multiple practitioners can pose challenges.48 Therefore, ongoing training and making use of innovations in training are likely possible solutions to manage such challenges.

Nurses: undertaking significant roles in care coordination models

In the care coordination models reviewed, we found that nurses undertook significant roles. Many models assigned nurses to be the navigators or coordinators, who could help harmonise the clinic flow among patients and various healthcare providers, perform an essential role in the paediatric patients’ transition and contribute to bridging the gap between children and adult care services. They coordinated relevant care services for young patients with complex health needs until their adult healthcare was determined. Due to their contribution, continuity of care could be ensured.49 In this review, the nurse navigator served as a bridge between childhood cancer survivors and healthcare providers, interacting with patients and their families and participating in various care coordination services.

Besides the nurse navigator or coordinator, in some models of this review, clinical nurses, nurse practitioners, advanced practice nurses, nurse educators and research nurses were also involved in the care coordination clinic flow and responsible for a wide range of healthcare services.23 25 26 29 The roles of nurses in care coordination aligned with the framework of nurses’ contributions to care coordination from the American Nurses Association, covering the healthcare system, institutional and individual/population aspects.11 50 The participation of different nurse roles in care coordination enhanced the quality and efficiency of patients’ care.51 However, nurses face several challenges and barriers in fulfilling their role in the care coordination role. Some of the key issues reported include increased workload, lack of resources and funding, inadequate training and support and poor communication between multidisciplinary teams.52 Nursing staff also work hard to navigate the complex healthcare system and coordinate diverse services for patients with unique needs. Addressing these challenges through targeted interventions and resources can further enhance caregiver contributions to effective care coordination.48 52

Implications

This review synthesises findings from prior studies on care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU and addresses gaps in evidence. Based on our findings in this review, future efforts to implement care coordination strategies for childhood cancer survivors should involve a multidisciplinary team approach to provide individualised, comprehensive and integrated care services tailored to the unique health needs of each survivor. To link survivors, their families and healthcare providers, as well as to manage multiple healthcare activities, the role of patient coordinator or navigator in the care coordination model is recommended, and nurses are well suited to participate in this role. In addition to patient coordination and navigation, experienced nurses could also be responsible for health education and research endeavours related to care coordination for childhood cancer survivors.

Of note, we did not determine the best model for childhood cancer survivors in this review. Considering the variation across health systems in different contexts, a single model is unlikely to fit all childhood cancer survivors’ needs of their transition and LTFU in all clinical settings.27 53 Therefore, future research should focus on the overall performance and outcomes of interest of various care coordination models to provide more guidance on optimal models in different contexts.

Limitations

This review had several limitations that should be noted. First, this review only searched and screened studies published in English, resulting in limited studies. Moreover, all care coordination models included in this review were implemented in Western countries, with five from the USA and one from Europe. Considering the influence of the healthcare system and health policy on care coordination,53 care coordination models under different contexts might have heterogeneity. A US-based model may not apply to other countries. The European centres and developing countries may face many hurdles in setting up the LTFU clinics and this review does not have much information on that. Although in this review we considered the settings of each model in the analysis, in future studies, the background of the study site and organisational context needs to be assessed when generalising the findings.

Conclusion

This review analysed existing care coordination models for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU care. Three features and five main care tasks of the care coordination models were identified. The 3I’s common elements (individualisation, interaction and integration) were synthesised and a conceptual model was proposed. Future research is needed to implement and test the proposed model to refine care coordination strategies that are appropriate for high-quality healthcare for childhood cancer survivors’ transition and LTFU.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Research Start-up Fund, grant number 5501858.

Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-087343).

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability free text: All data relevant to the study are included in the article. Other data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Contributor Information

Cho Lee Wong, Email: jojowong@cuhk.edu.hk.

Carmen Wing Han Chan, Email: whchan@cuhk.edu.hk.

Mengyue Zhang, Email: kassiezhang@link.cuhk.edu.hk.

Yin Ting Cheung, Email: yinting.cheung@cuhk.edu.hk.

Ka Ming Chow, Email: kmchow@cuhk.edu.hk.

Chi Kong Li, Email: ckli@cuhk.edu.hk.

William H C Li, Email: williamli@cuhk.edu.hk.

Eden Brauer, Email: ebrauer@sonnet.ucla.edu.

Yongfeng Chen, Email: chenyongfeng@link.cuhk.edu.hk.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.World Health Orgnization Childhood cancer. [13-Sep-2023];2021 https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-636r.pdf Available. accessed.

- 2.Marchak JG, Sadak KT, Effinger KE, et al. Transition practices for survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17:342–50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-023-01351-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denlinger CS, Carlson RW, Are M, et al. Survivorship: introduction and definition. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:34–45. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriks MJ, Harju E, Michel G. The unmet needs of childhood cancer survivors in long-term follow-up care: A qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2021;30:485–92. doi: 10.1002/pon.5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan CWH, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health-related quality-of-life and psychological distress of young adult survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Psychooncology. 2014;23:229–36. doi: 10.1002/pon.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan CWH, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health Behaviors of Chinese Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Comparison Study with Their Siblings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6136. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betz CL, O’Kane LS, Nehring WM, et al. Systematic review: Health care transition practice servicemodels. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64:229–43. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia S, Meadows AT. Long-term follow-up of childhood cancer survivors: future directions for clinical care and research. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:143–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson MM, Bhatia S, Casillas J, et al. Long-term Follow-up Care for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Pediatrics. 2021;148:e2021053127. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. AHRQ Technical Reviews. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol 7: Care Coordination) Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karam M, Chouinard M-C, Poitras M-E, et al. Nursing Care Coordination for Patients with Complex Needs in Primary Healthcare: A Scoping Review. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21:16. doi: 10.5334/ijic.5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izumi S, Barfield PA, Basin B, et al. Care coordination: Identifying and connecting the most appropriate care to the patients. Res Nurs Health. 2018;41:49–56. doi: 10.1002/nur.21843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz EM, McDonald KM. What is care coordination? Int J Care Coord. 2014;17:5–24. doi: 10.1177/2053435414540615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, et al. The impact of long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LM, Ayanian JZ. Care continuity and care coordination: what counts? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:749–50. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, et al. Cancer Care Coordination: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 30Years of Empirical Studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:532–46. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatri R, Endalamaw A, Erku D, et al. Continuity and care coordination of primary health care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:750. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09718-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmarcher-Holzhacker M, Oxley H, Rusticelli E. OECD, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, OECD Health Working Papers. 2007. Improved health system performance through better care co-ordination; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno MA. Pediatric Care Coordination. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:112–12. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan-Porter W, Ullman K, Majeski B, et al. Care Coordination Models and Tools-Systematic Review and Key Informant Interviews. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:1367–79. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07158-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Overholser LS, Moss KM, Kilbourn K, et al. Development of a Primary Care-Based Clinic to Support Adults With a History of Childhood Cancer: The Tactic Clinic. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:724–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClellan W, Fulbright JM, Doolittle GC, et al. A Collaborative Step-Wise Process to Implementing an Innovative Clinic for Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:e147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson MM, Hester A, Sweeney T, et al. A model of care for childhood cancer survivors that facilitates research. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21:170–4. doi: 10.1177/1043454204264388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson CA, Hobbie WL, Brogna M, et al. A multidisciplinary model of care for childhood cancer survivors with complex medical needs. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;25:7–13. doi: 10.1177/1043454207311741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman DL, Freyer DR, Levitt GA. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:159–68. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loonen JJ, Blijlevens NM, Prins J, et al. Cancer Survivorship Care: Person Centered Care in a Multidisciplinary Shared Care Model. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18:4. doi: 10.5334/ijic.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Johnston KA, et al. Re-Engage: A Novel Nurse-Led Program for Survivors of Childhood Cancer Who Are Disengaged From Cancer-Related Care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:1067–74. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds A. Patient-centered Care. Radiol Technol. 2009;81:133–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–3. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:804–12. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixon SB, Bjornard KL, Alberts NM, et al. Factors influencing risk-based care of the childhood cancer survivor in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:133–52. doi: 10.3322/caac.21445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chow KM, Chan JCY, Choi KKC, et al. A Review of Psychoeducational Interventions to Improve Sexual Functioning, Quality of Life, and Psychological Outcomes in Gynecological Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:20–31. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safran DG. Defining the Future of Primary Care: What Can We Learn from Patients? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:248. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zebrack BJ, Chesler MA, Penn A. In: Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. Bleyer WA, Barr RD, editors. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. Psychosocial support; pp. 375–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Schueller SM, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cancer survivors: A meta-analysis of effects on positive affect. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13:943–55. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsen ML, Sereika SM, Hoffman LA, et al. Nurse and patient interaction behaviors’ effects on nursing care quality for mechanically ventilated older adults in the ICU. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2014;7:113–25. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20140127-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin N. Understanding Integrated Care. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16:6. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonorezos ES, Barnea D, Cohn RJ, et al. Models of Care for Survivors of Childhood Cancer From Across the Globe: Advancing Survivorship Care in the Next Decade. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2223–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lillrank P. Integration and coordination in healthcare: an operations management view. J Integ Care. 2012;20:6–12. doi: 10.1108/14769011211202247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Disabilities C, Committee M, Turchi RM, et al. Patient- and Family-Centered Care Coordination: A Framework for Integrating Care for Children and Youth Across Multiple Systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1451–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leach KF, Stack NJ, Jones S. Optimizing the multidisciplinary team to enhance care coordination across the continuum for children with medical complexity. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021;51:101128. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox CL, Sherrill-Mittleman DA, Riley BB, et al. Development of a comprehensive health-related needs assessment for adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taberna M, Gil Moncayo F, Jané-Salas E, et al. The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and Quality of Care. Front Oncol. 2020;10:85. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruhstaller T, Roe H, Thürlimann B, et al. The multidisciplinary meeting: An indispensable aid to communication between different specialities. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2459–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLoone JK, Chen W, Wakefield CE, et al. Childhood cancer survivorship care: A qualitative study of healthcare providers’ professional preferences. Front Oncol. 2022;12:945911. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.945911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly D. Theory to reality: the role of the transition nurse coordinator. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:888. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.16.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Nurses Association Framework for measuring nurses’ contributions to care coordination. 2013

- 51.Cropley S, Sandrs ED. Care coordination and the essential role of the nurse. Creat Nurs. 2013;19:189–94. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.19.4.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, et al. Models of childhood cancer survivorship care in Australia and New Zealand: Strengths and challenges. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:407–15. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kilbourne AM, Hynes D, O’Toole T, et al. A research agenda for care coordination for chronic conditions: aligning implementation, technology, and policy strategies. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:515–21. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]