Abstract

Three CCD (central core disease) mutants, R4892W (Arg4892→Trp), I4897T and G4898E, in the pore region of the skeletal-muscle Ca2+-release channel RyR1 (ryanodine receptor 1) were characterized using a newly developed assay that monitored Ca2+ release in the presence of Ca2+ uptake in microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells), co-expressing each of the three mutants together with SERCA1a (sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1a). Both Ca2+ sensitivity and peak amplitude of Ca2+ release were either absent from or sharply decreased in homotetrameric mutants. Co-expression of wild-type RyR1 with mutant RyR1 (heterotetrameric mutants) restored Ca2+ sensitivity partially, in the ratio 1:2, or fully, in the ratio 1:1. Peak amplitude was restored only partially in the ratio 1:2 or 1:1. Reduced amplitude was not correlated with maximum Ca2+ loading or the amount of expressed RyR1 protein. High-affinity [3H]ryanodine binding and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release were also absent from the three homotetrameric mutants. These results indicate that decreased Ca2+ sensitivity is one of the serious defects in these three excitation–contraction uncoupling CCD mutations. In CCD skeletal muscles, where a mixture of wild-type and mutant RyR1 is expressed, these defects are expected to decrease Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, as well as orthograde Ca2+ release, in response to transverse tubular membrane depolarization.

Keywords: Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release, 45Ca2+ uptake and release, excitation–contraction coupling, central core disease, ryanodine receptor, skeletal-muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum

Abbreviations: CCD, central core disease; DHPR, dihydropyridine receptor; EC, excitation–contraction; HEK-293 cell, human embryonic kidney 293 cell; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; mAb and pAb, monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies; MH, malignant hyperthermia; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA1a, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1a; wt, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

A key step in EC (excitation–contraction) coupling in skeletal muscles involves Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in response to depolarization of the sarcolemmal membrane. Two critical proteins in this process are the dihydropyridine-sensitive, L-type Ca2+ channel [DHPR (dihydropyridine receptor)], located in the transverse tubular membrane, and the Ca2+-release channel isoform 1 (RyR1, ryanodine receptor 1), located in the junctional terminal cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Ca2+ release through RyR1 is activated by direct physical interaction with DHPR molecules, which are activated by depolarization [1]. Mutations in the α1 subunit of DHPR cause human hypokalemic periodic paralysis [2,3] and human MH (malignant hyperthermia), a toxic response to inhalational anaesthetics and depolarizing skeletal-muscle relaxants [4]. Mutations in RYR1 also cause MH in humans [5], swine [6] and dogs [7] and cause CCD (central core disease) in humans [8,9].

CCD is an autosomal dominant, slow-progressive or non-progressive congenital myopathy with different kinds of penetration ranging from asymptomatic to severe (for details, see reviews in [10–14]). CCD is characterized by hypotonia and proximal muscle weakness with the variable occurrence of pes cavus, kyphoscoliosis, congenital hip dislocation, clubfoot and joint contractures. Diagnosis of CCD is based on the histology of muscle biopsies, which reveal amorphous central cores that are depleted of mitochondria and lack normal oxidative enzyme activity in both fibre types. A majority, but not all CCD patients are MH-susceptible, the same RYR1 mutation causing both the phenotypes [8,9].

More than 80 human RYR1 mutations have been associated with MH or CCD to date [14–19]. These mutations are missense or inframe deletions and insertions. MH mutations predominate in the cytosolic N-terminal and central hotspots (MH/CCD domains 1 and 2), whereas CCD mutations predominate in the C-terminal hotspot (MH/CCD domain 3). In our recent model of the membrane topology of RyRs [20], most of the C-terminal CCD mutations are located in the pore region, in transmembrane sequences and in the luminal loops connecting transmembrane sequences, but a few lie in the large, N-terminal cytosolic domain and the cytosolic loops at the C-terminus.

Functional studies of isolated RyR1, isolated sarcoplasmic-reticulum microsomes and skinned muscle fibres from MH pigs and humans have demonstrated defects in RyR1 function and the abnormal regulation of Ca2+ in muscles (for details, see review in [10]). These defects include the increased sensitivity of RyR1 to activation by Ca2+ and other agents such as caffeine, halothane and 4-chloro-m-cresol. Often, the channels are less sensitive to inactivation by Ca2+ and calmodulin. Ca2+ release in cultured human skeletal-muscle cells derived from an MH-susceptible individual [21] and from an MH/CCD patient with the I2453T (Ile2453→Thr) mutation [22] exhibited increased sensitivity to halothane and 4-chloro-m-cresol. Functional expressions of MH and MH/CCD mutant RyR1 constructs in mammalian cell lines and dyspedic myotubes showed their enhanced sensitivity to caffeine, halothane and 4-chloro-m-cresol [21,23–27] and decreased sensitivity to inhibition by Ca2+ and Mg2+ [26].

Mutations causing CCD are classified into two categories, leaky-channel [11,27–29] and EC uncoupling [14,30,31]. Expression of MH/CCD mutations from the first two hotspots, in HEK-293 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells) and dyspedic myocytes increased resting cytosolic Ca2+ levels and reduced the size of the Ca2+ store, suggesting Ca2+ leakage from homotetrameric channels [27,29,31–33]. Immortalized B-lymphocytes from CCD patients carrying RYR1 mutations in MH/CCD domain 3 showed endogenous Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and a depleted Ca2+ store in the absence of any pharmacological activator of RyR1 [18,34], suggesting that the heterotetrameric channels in these cells are leaky. However, I4897T and other mutants in the pore region expressed as homotetramers in dyspedic myotubes produced an uncoupling of sarcolemmal excitation from Ca2+ release by the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Resting cytosolic Ca2+ levels and the size of the Ca2+ store were normal [30,31].

The pharmacology of some domain 3 CCD mutants is distinct from that of MH/CCD mutants in domains 1 and 2. When expressed in a heterologous system, the homotetrameric I4897T and some other mutations in domain 3 abolished caffeine-induced Ca2+ release and the heterotetrameric mutation reduced the amplitude of Ca2+ release significantly [18,30–32,35,36]. The corresponding mutation in RyR2 (I4829T) resulted in unregulated channels with high open probability, reduced conductance and loss of high-affinity [3H]ryanodine binding [35,36]. Although single-channel measurements [35–37] and [3H]ryanodine binding [38,39] have provided detailed information about the mutant channel's function, there are contradictions between the in vivo function and the altered regulation seen in single channels in vitro [35,36]. The inability of uncoupled mutants to bind [3H]ryanodine with high affinity excludes the use of these approaches for further functional analysis of the CCD mutations.

To gain further insight into how these mutations affect channel function, we devised an assay for 45Ca2+ uptake and release in microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells co-transfected with SERCA1a (sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1a) and RyR1. This assay allowed us to measure Ca2+ release through wt (wild-type) and mutant RyR1 under specific conditions. We demonstrated that the RyR1 CCD mutations R4892W, I4897T and G4898E abolished or decreased Ca2+ sensitivity and peak amplitude of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release, reflecting an alteration in the intrinsic channel function.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

[45Ca] was obtained from Amersham Biosciences and [3H]ryanodine from DuPont NEN (Boston, MA, U.S.A.); fura 2 acetoxymethyl ester was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.); unlabelled ryanodine was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.); and the expression vector pcDNA 3.1(−) was from Invitrogen. All other reagents were of reagent-grade or the highest grade available.

Mutagenesis

Construction of the RyR1 CCD mutant I4897T was described previously [32]; the mutants R4892W and G4898E were constructed using the same approach.

Cell culture and DNA transfection

Culturing of HEK-293 cells and cDNA transfection using the calcium phosphate precipitation method were performed as described previously [38]. For co-transfection of wt or mutant RyR1 with SERCA1a, 20 μg of RyR1 and 8 μg of SERCA1a DNA were added to a 10 cm plate.

Microsome preparation and protein assay

Microsomes were prepared as described previously [40]. Protein concentration was determined by dye binding using BSA as a standard [41].

[45Ca] uptake and release

We analysed the Ca2+-release channel function for wt and CCD mutant RyR1 using an oxalate-supported 45Ca2+-uptake and -release assay, in which 45Ca2+ was actively loaded into isolated microsomal vesicles expressing recombinant SERCA1a by ATP-dependent Ca2+ transport. By comparing the amount of 45Ca2+ accumulated in the microsomal vesicles for a 60 min incubation period in the presence and absence of the potent Ca2+-release channel inhibitor Ruthenium Red, the amount of Ca2+ released could be calculated. The assay was performed in a buffer containing 150 mM KCl, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.1 μM free Ca2+, 5 mM potassium oxalate, 1 mM Na2-ATP, 100 μg/ml heparin and 0.5–1 μCi/ml [45Ca]CaCl2 in the presence or absence of Ruthenium Red (40 μM). Microsomes with or without pretreatment with 40 μM Ruthenium Red were added after all the components were mixed and incubated at room temperature (22–24 °C). Duplicate aliquots were filtered through glass-fibre filters, which were then washed with 12 ml of a washing buffer containing 150 mM KCl and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), and counted in a scintillation counter. For time-course studies, 100 μl aliquots, each containing approx. 15 μg of microsomes, were taken from the reaction mixture for filtration after different time periods. For Ca2+ sensitivity measurements, approx. 15 μg of microsomes were incubated in separate 100 μl reaction mixtures containing incremental concentrations of Ca2+ in the presence and absence of Ruthenium Red for 60 min before filtration. All experiments were performed in duplicate. Free Ca2+ was calculated using the apparent binding constants described by Fabiato [42].

Quantification of expressed RyR1 and SERCA1a by ELISA

Relative expressions of RyR1 and SERCA1a in microsomal fractions were determined by sandwich ELISA using mAb (monoclonal antibody) 34C and pAb (polyclonal antibody) R46 (a gift from Dr K. P. Campbell, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, U.S.A.) for RyR1 and using mAb A52 and pAb R4 for SERCA1. In this assay, polystyrene microtitre plates were coated with a sheep anti-mouse IgG, Fc fragment-specific antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, U.S.A.) by overnight incubation of 100 μl of coating antibody solution containing 500 ng of antibody diluted in 50 mmol/l Tris buffer (pH 7.8) in each well. The plates were then washed six times with the washing buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20 and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4). mAb (100 ng/well) was applied to each well, incubated for 1 h and washed six times with washing buffer. Samples in a series of three dilutions (1:1, 1:4 and 1:8) containing approx. 15 μg of microsomes in a 1:1 ratio, solubilized in 1% CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Hepes/Tris (pH 7.2), were added to separate wells, incubated for 2 h and then washed six times with washing buffer. A pAb antibody (1:1000) was then added for 60 min and washed. Finally, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000) was applied to the plates and an alkaline phosphatase substrate was added. The signal was measured by time-resolved fluorescence. All samples were measured in duplicate.

Fluorescence measurements and [3H]ryanodine binding

A microfluorimetry system (Photon Technologies) was used to monitor the fura 2 acetoxymethyl ester fluorescence changes in transiently transfected or non-transfected HEK-293 cells, as described previously [36,38]. [3H]Ryanodine-binding properties were analysed using the [3H]ryanodine-binding assay described previously [38].

RESULTS

Characterization of R4892W, I4897T and G4898E by [3H]ryanodine binding and Ca2+ photometry

More than ten mutations in the region of RyR1 predicted to be associated with the membrane have been identified in patients with CCD. Seven of these mutations, lying in the pore region between amino acids 4890 and 4913, have been characterized by reconstitution in dyspedic myotubes [32,34]. In the present study, we selected three of these pore region mutants, R4892W, I4897T and G4898E, to test the functional consequences of mutation using a novel approach, which measures 45Ca2+ release in the presence of 45Ca2+ uptake.

RyR1 and the RyR1 mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E were first characterized by [3H]ryanodine binding and Ca2+ photometry. Approx. 36–40 h after transfection in HEK-293 cells, highaffinity [3H]ryanodine binding was measured in whole cell lysates and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was measured in intact cells, as described previously [38]. No high-affinity [3H]ryanodine binding was detected in either isolated microsomes or solubilized lysates from cells expressing the three mutants (results not shown), confirming previous evidence that specific mutations in the pore region disrupt [3H]ryanodine binding [35,36]. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in cells expressing homotetrameric forms of the three mutants could not be detected (results not shown). However, caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was observed for co-expression of these mutants with wt RyR1 in a 1:1 ratio. Caffeine sensitivity (EC50 value) was 1.9±0.3 mM (±S.D., n=5, P<0.05) for R4892W; 2.4±0.7 mM (n=5, P>0.05) for I4897T; and 5.6±1.9 mM (n=5, P<0.05) for G4898E. These values for R4892W and G4898E were significantly different from the EC50 value of 2.6±0.9 mM (n=5) that was obtained for wt RyR1.

Oxalate-supported, ATP-dependent 45Ca2+ uptake and release in microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells expressing RyR and SERCA1a

Co-expression of SERCA1a with IP3R (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor) and measurement of oxalate-supported Ca2+ accumulation in the presence and absence of heparin, a potent inhibitor of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, provided the means by which Ca2+ release from microsomal fractions expressing IP3Rs could be determined through a subtractive measurement [43]. We reasoned that co-expression of SERCA1a with RyR1 would provide an equally effective method for measuring Ca2+-release activity in wt or mutant RyR1 expressed in HEK-293 cells. Through the inhibition of RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release with the potent inhibitors Ruthenium Red or high concentrations of ryanodine [44–46], Ca2+ release mediated by RyR1 could be determined by comparing the amount of Ca2+ retained in the microsomes in the presence and absence of the RyR inhibitor.

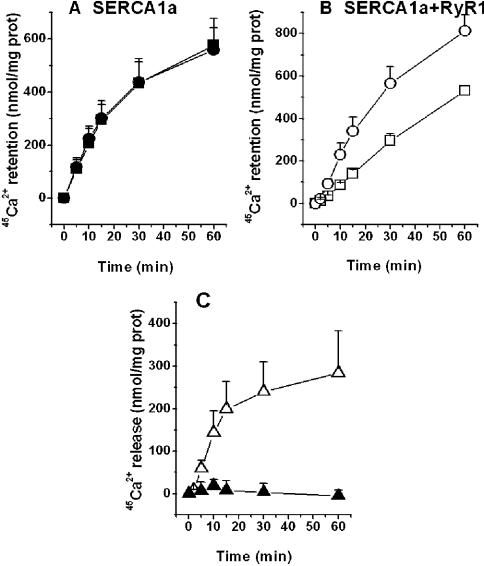

Microsomes isolated from non-transfected HEK-293 cells or HEK-293 cells transfected only with RyR cDNA had negligible ATP-dependent Ca2+ uptake activity in the presence of 5 mM oxalate and 0.1 μM free Ca2+ (pCa 7; results not shown). Microsomes from cells expressing SERCA1a alone transported Ca2+ to the lumen by ATP hydrolysis (Figure 1A), with a normalized linear slope of 3.1±0.43%·(mg of protein)−1·min−1 (n=3) for a time course of 15 min. The addition of Ruthenium Red at 40 μM did not alter the time course for Ca2+ uptake significantly (Figure 1A), suggesting that Ruthenium Red does not interfere with Ca2+ uptake under these conditions [slope=3.02±0.55% mg−1·min−1 (n=3)]. When RyR1 was co-expressed with SERCA1a, ATP-dependent Ca2+ accumulation in the microsomes was significantly higher in the presence of 40 μM Ruthenium Red than in its absence at all time points measured (Figure 1B). The slope of Ca2+ uptake during the first 15 min for microsomes containing both SERCA1a and RyR1 in the presence of Ruthenium Red was 2.95±0.45% mg−1·min−1 (n=5), similar to that for microsomes containing only SERCA1a, suggesting that Ca2+ release through RyR1 is completely blocked by Ruthenium Red under these conditions.

Figure 1. Time course for Ca2+ uptake and release.

Experiments were performed as described in the Experimental section, with microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells expressing either SERCA1a alone (A) or RyR1 (B). Symbols in (A, B) represent two experimental conditions: presence (•, ○) or absence (▪, □) of 40 μM Ruthenium Red. (C) Net Ca2+ release was calculated by subtracting the amount of Ca2+ retained in the microsomes in the presence of 40 μM Ruthenium Red from the amount of Ca2+ retained in the absence of this inhibitor (results from A and B). ▴, no Ca2+ release was observed for SERCA1a alone, using results from (A); ▵, a significant amount of Ca2+ was released by RyR1, using results from (B) (n=5). Results are expressed as means±S.D.

The level of Ca2+ release triggered by the levels of ATP and Ca2+ used in the experiment was calculated by subtracting the amount of Ca2+ retained in the presence of Ruthenium Red from the amount of Ca2+ retained without this inhibitor (Figure 1C). The time course for Ca2+ release was linear for up to 15 min, with a slope of 13.4±4.4 nmol·mg−1·min−1, reaching a maximum of 283±90 nmol/mg of protein at 60 min. For expressed SERCA1a alone, there was no significant difference in Ca2+ accumulation in the presence or absence of 40 μM Ruthenium Red, in line with the view that there was no Ca2+ release through endogenous RyR1 Ca2+-release channels (Figure 1C). This was expected, since RyR1 is not expressed in HEK-293 cells [47].

The time course for Ca2+ accumulation by microsomes from HEK-293 cells expressing SERCA1a and the RyR1 CCD mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E was almost identical in the presence and absence of 40 μM Ruthenium Red (results not shown) and was similar to the time course for SERCA1a alone (see Figure 1A). These results indicate that the levels of Ca2+ (pCa 7) and ATP (1 mM) present in the medium did not activate the mutant channels as significantly as they did wt RyR1 (Figure 1B). Since both Ca2+ and ATP are activators of Ca2+ release [48], methods were designed to test whether higher concentrations of Ca2+ alone could activate wt and mutant channels in this assay system.

Ca2+ dependence of Ca2+ release from microsomes loaded with Ca2+ by SERCA1a activity

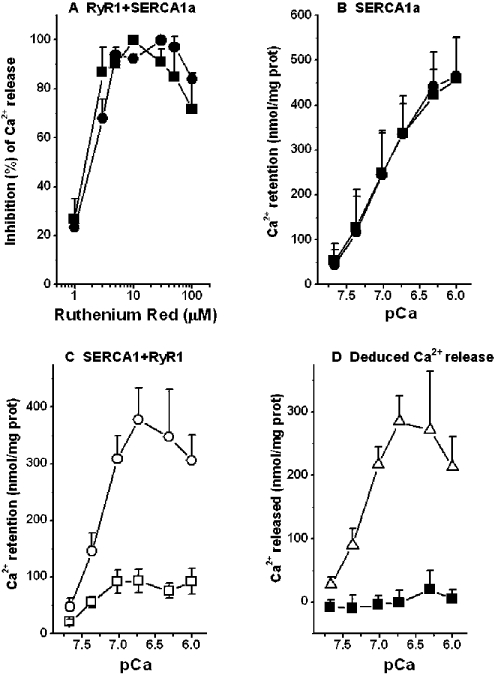

A series of Ca2+ concentrations from pCa 7.67 to 6 was used to determine if Ca2+ could induce Ca2+ release from microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells expressing SERCA1a and wt type RyR1. To attain maximum resolution between the Ca2+ levels retained in the microsomes in the presence and absence of Ruthenium Red, we chose an incubation period of 1 h. This time period was chosen because incubation for 1 h gave a better separation between the curves representing Ca2+ uptake and Ca2+ release compared with incubation for 15 or 30 min at incremental Ca2+ concentrations (results not shown), even though Ca2+ release was linear only for time points up to 15 min. We also tested the effect of Ruthenium Red on the inhibition of Ca2+ release in wt RyR1 at pCa 6.0 and 7.0. Similar levels of inhibition of Ca2+ release were observed with Ruthenium Red at concentrations between 5 and 50 μM at both pCa 6.0 and 7.0 (Figure 2A). All further experiments were performed with 40 μM Ruthenium Red.

Figure 2. Effect of Ruthenium Red on Ca2+ release by RyR1 at pCa between 7.67 and 6 and on Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release from microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells expressing either SERCA1a alone, or with RyR1.

(A) Normalized inhibition of Ca2+ release (n=3) was plotted against incremental concentrations of Ruthenium Red at pCa 7 (▪) and pCa 6 (•). (B) Ca2+ uptake at incremental Ca2+ concentrations in the presence (•) or absence (▪) of 40 μM Ruthenium Red, showing no difference between the two groups (n=3). (C) Ca2+ uptake at incremental Ca2+ concentrations in the presence (○) of 40 μM Ruthenium Red was higher than that in the absence (□) of Ruthenium Red (n=5). (D) Net Ca2+ release was calculated by subtracting the Ca2+ retained in the microsomes in the presence of Ruthenium Red from the amount of Ca2+ retained in the absence of Ruthenium Red (results from B and C). ▪, no Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release by the SERCA1a alone microsomes from (B); ▵, Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release by RyR1 from (C). Results are expressed as means±S.D.

In microsomes from HEK-293 cells expressing SERCA1a alone, incremental increases in Ca2+ concentrations from pCa 7.67 to 6 increased the Ca2+ accumulation in the presence or absence of Ruthenium Red (Figure 2B). In microsomes from HEK-293 cells co-transfected with wt RyR1 and SERCA1a, Ca2+ accumulation increased slightly as Ca2+ concentrations were increased from pCa 7.7 to 7, where a plateau was reached in the absence of Ruthenium Red (Figure 2C). The addition of 40 μM Ruthenium Red increased Ca2+ retention in the microsomes over the range of Ca2+ concentrations studied. Nevertheless, we noted decreased retention of Ca2+ at Ca2+ concentrations higher than pCa 6.7, where a maximum was reached (Figure 2C). These results suggest that high concentrations of Ca2+ can compete with Ruthenium Red to increase Ca2+ release from the store by activating the channels.

Subtraction of the amount of Ca2+ retained in microsomes in the presence of Ruthenium Red from the amount of Ca2+ retained in microsomes in the absence of Ruthenium Red showed no Ca2+ release when SERCA1a was expressed alone, but produced a bell-shaped curve for Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release when SERCA1a was co-expressed with RyR1 (Figure 2C). We analysed the increasing phase of Ca2+ release by fitting the release phase of the curve to the maximum point and the EC50 value for Ca2+ sensitivity of Ca2+ release was determined to be pCa 7.22±0.11 (n=5).

Defects in Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release in CCD pore region mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E

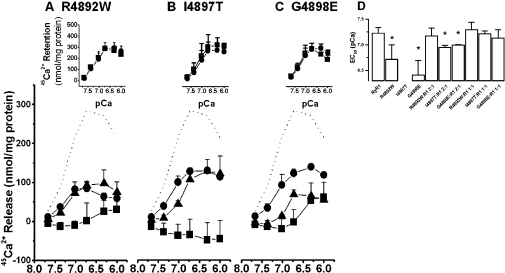

The same methods were used to determine whether CCD mutant Ca2+-release channels, R4892W, I4897T and G4898E, would respond to incremental increases in Ca2+ concentration. Homotetrameric R4892W (Figure 3A) and G4898E (Figure 3C) did not release any significant level of Ca2+ below pCa 6.7, but released a small amount of Ca2+ above pCa 6.3. Homotetrameric I4897T did not release Ca2+ at any of the Ca2+ concentrations tested; indeed, Ruthenium Red decreased Ca2+ sequestration, producing a negative value between pCa 7.7 and 6 for Ca2+ release from I4897T (Figure 3B, inset). This difference was up to 15% (Figure 3B, inset). This phenomenon was never observed for wt RyR1 (Figure 2D); however, to a lesser extent, it was observed for R4892W and G4898E at pCa values between 7.7 and 6.7 (insets to Figures 3A and 3C). It is probable that Ruthenium Red normally binds in the transmembrane domain and stabilizes it so that spontaneous or activated channel function is inhibited. For the I4897T mutant, on the other hand, Ruthenium Red binding might be altered so that spontaneous channel opening is slightly enhanced in comparison with the Ruthenium Red-free channel. If this should be true, then Ile4897 might be a key residue in Ruthenium binding.

Figure 3. Reduction in the Ca2+ sensitivity of Ca2+ release in CCD mutants R4892W (A), I4897T (B) and G4898E (C).

Experiments were performed as described in the Experimental section, with microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells expressing SERCA1a with wt or mutant RyR1. Ca2+ release was calculated by subtracting the Ca2+ retained in the microsomes in the presence of Ruthenium Red from the Ca2+ retained in the absence of Ruthenium Red, as in Figures 1 and 2. (A–C) ······, Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release for wt RyR1 (results from Figure 2); ▪, homotetrameric mutants (n=3–5); •, heterotetrameric mutants transfected with cDNAs in the ratio of 1:2 (wt RyR1/mutant RyR1, n=3); ▴, heterotetrameric mutants in the ratio 1:1 (wt RyR1/mutant RyR1, n=3). Insets to Figures 3(A)–3(C) show Ca2+ retention in microsomes in the presence (▪) or absence (•) of 40 μM Ruthenium Red. These data are the source for calculating the Ca2+ sensitivity of the three homotetrameric channels. (D) EC50 values were calculated from (A–C). The value for homotetrameric I4897T could not be determined. From an analysis using one-way ANOVA, EC50 values for homo- and heterotetrameric I4897T and G4898E in a 1:2 ratio were significantly lower (*P<0.05) compared with those for wt RyR1; however, they were not different for wt RyR1 versus heterotetrameric RyR1 in a 1:1 ratio. Results are expressed as means±S.D.

These observations establish that the CCD mutants R4892W and G4898E have a Ca2+-dependent Ca2+-release function, but with decreased Ca2+ sensitivity. On the other hand, Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release was not found in the CCD mutant I4897T. Normalizing the data and fitting them with a logistic dose–response equation gave EC50 values of 6.72±0.28 pCa units for R4892W (n=3) and 6.41±0.27 for G4898E (n=3; Figure 3D). These values are significantly lower than the value of pCa 7.22±0.11 determined for RyR1. For the CCD mutant I4897T, EC50 could not be calculated.

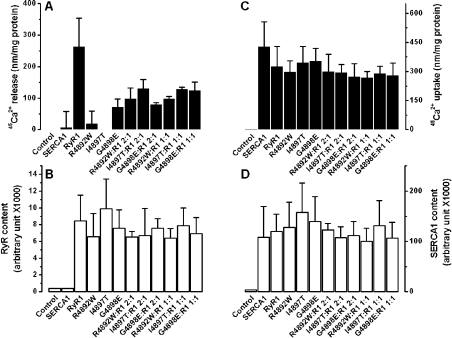

A second important feature of Ca2+ release through the CCD mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E was the loss or sharp decrease in the amplitude of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release for both homo- and heterotetrameric forms (Figures 3A–3C and 4A) when compared with that observed for wt RyR1. We excluded the possibility that these differences arose from different expression levels, since a sandwich ELISA showed that the amount of protein expressed was comparable among the wt and the mutants (Figure 4B). Decreased amplitude was also not due to different levels of Ca2+ loading, since maximum Ca2+ uptake was similar between the wt and mutants (Figure 4C) and Ca2+ uptake was proportional to the expressed levels of SERCA1a in all cases (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Reduction in peak amplitude of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release in the CCD mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E.

(A) Peak amplitudes were obtained from the maximum Ca2+ release observed at pCa 6.75–6 for the wt and homo- or heterotetrameric RyR1 mutants mainly from Figure 3. ANOVA showed a significant difference between peak amplitudes for wt and mutants (P<0.01). (B) Content of expressed wt and homo- or heterotetrameric RyR1 mutants, measured by ELISA, as described in the Experimental section. No RyR1 was detected in control HEK-293 cells transfected with pcDNA vector or cells expressing SERCA1a alone. No significant difference was obtained by ANOVA between wt and mutants (P>0.05) for peak Ca2+ uptake (C) or content of expressed SERCA1a (D) for the samples: SERCA1a alone, SERCA1a+wt RyR1 and SERCA1a+mutant RyR1. No significant differences were observed for Ca2+ uptake and SERCA1a content between control cells and those transfected with pcDNA vector. Results are expressed as means±S.D.

We examined the possibility that co-expression of the CCD mutant RyR1 with wt type RyR1 could restore Ca2+ sensitivity and the amplitude of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release for mutant channels. Expression of wt RyR with mutant RyR1 in the ratio 1:2 restored Ca2+ sensitivity fully for R4892W and partially for I4897T and G4898E (Figure 3). When expressed in the ratio 1:1, Ca2+ sensitivity was completely restored for all the three mutants (Figure 3). However, the amplitude of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release for heterotetrameric channels, co-expressed with wt RyR1 in a 1:2 or 1:1 ratio, was not fully recovered for any of the three mutants (Figure 4A). For all three heterotetrameric mutants, RyR1 expression and total Ca2+ loading relative to SERCA1a content were at levels close to those for wt RyR1 (Figures 4B–4D).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we devised an assay for the measurement of Ca2+ release in the presence of Ca2+ uptake in microsomes isolated from HEK-293 cells. The assay involves the co-expression of SERCA1a with wt or CCD mutant RyR1 and compares the amount of Ca2+ accumulated in the presence and absence of an inhibitor of the Ca2+-release channel. We used this assay to show that incremental increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations not only activate Ca2+ uptake, but also activate Ca2+ release, resulting in decreased Ca2+ accumulation. The decrease in Ca2+ accumulation was used as a measure of Ca2+ release. The assay also permitted us to obtain a measure of the Ca2+ sensitivity of wt and mutant Ca2+-release channels. We demonstrated defects in Ca2+ sensitivity and the maximum amplitude of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release for homotetrameric CCD mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E. Co-expression of mutants with wt RyR1 restored Ca2+ sensitivity to normal in 1:1 heterotetramers, but restored the amplitude of Ca2+ release only partially.

In developing the assay for measurement of Ca2+ release in the presence of Ca2+ uptake in microsomes, problems arise in quantifying the Ca2+ sensitivity of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release. Owing to differential co-operative interactions between ATP and Ca2+ at each Ca2+ concentration and, potentially, other unknown factors, our EC50 values probably do not reflect true Ca2+ sensitivity. Nevertheless, we believe that the values can be used for valid comparison of function between wt and mutant channels. The assay, which measures Ca2+ permeation through a large population of channels, is especially valuable for the investigation of those mutants that appear to have lost single channel function.

In earlier studies involving the expression of homotetrameric I4897T or its equivalent in RyR2 (I4829T), caffeine-induced Ca2+ release and high-affinity [3H]ryanodine binding were lost [30,32,36]. Similarly, caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was lost for the homotetrameric G4898E mutant [31]. However, our results for caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from R4892W are not in agreement with the results of Avila et al. [31], who used reconstitution of dyspedic myotubes to show only a marginal reduction in caffeine-induced Ca2+ release with the homotetrameric mutant R4892W. This result differed from results they obtained in characterizing five other CCD mutations in the pore region, namely G4890R, I4897T, G4898E, G4898R and R4913G [30,31], all of which lost orthograde Ca2+ release through RyR1, retained retrograde Ca2+ entry through the DHPR and lost sensitivity to caffeine. R4892W and A4905V mutants, however, retained partial caffeine sensitivity and A4905V mutant retained partial voltage sensitivity. Although all these mutants acted as EC-uncoupling mutants, the specific properties of EC-uncoupled mutants may be heterogeneous.

The differences in the results between our study of caffeine sensitivity for the R4892W mutant and that of Avila et al. [31] may be due to the expression system used. For example, dyspedic myotubes may express endogenous modifier proteins, which participate in the function of expressed RyR proteins. Myotubes provide a more physiological setting in which coupling of RyR1 with DHPR permits both orthograde and retrograde Ca2+ release to be monitored and may also provide a setting in which R4892W can respond to caffeine. Caffeine is believed to act by increasing the sensitivity of the Ca2+ activation site [49]. Thus, if channel function in R4892W is activated by caffeine in myotubes, it implies that the Ca2+-release channel function and the Ca2+ activation site can be restored in this mutant under appropriate expression conditions. This possibility requires further examination in future studies.

In our Ca2+ uptake and release assay, the R4892W mutant is activated by high Ca2+ levels (Figure 3A) and is only weakly responsive to 10 mM caffeine (results not shown). From the present study, we conclude that the mutants R4892W, I4897T and G4898E all have decreased Ca2+ sensitivity, which is reflected as a change in the Ca2+ dependence of Ca2+ release. It is probable that decreased Ca2+ sensitivity and a lower amplitude of Ca2+ release reflect alterations in mutant channel function and do not result from alterations in luminal Ca2+ concentrations, which were similar in all experiments.

Earlier studies have identified a Ca2+-regulatory site upstream of the pore region at Glu3885 in RyR3 [37], equivalent to Glu4032 in the linear RyR1 sequence. Our results suggest the possibility that Ca2+ activation is influenced by interactions between residues in the pore region and those in other regions of the protein. It is also possible that these mutations decrease Ca2+ conductance through the channel pore by interfering with ion permeability. Although we do not have specific data on conductivity, it is interesting that a neighbouring mutation, G4826A in RyR2 (equivalent to G4894A in the RyR1 pore sequence), decreases channel conductance by almost 30-fold [36,50]. Thus a combination of decreased Ca2+ sensitivity and decreased conductance may account for the altered properties of the three mutants investigated in the present study.

An important question concerns how defects in the Ca2+ sensitivity of Ca2+ release for CCD mutants relate to the pathogenesis of CCD. The three homotetrameric mutant channels studied here were not leaky to Ca2+. In this respect, they differed from other CCD mutant RyR1 channels in MH/CCD domains 1 and 2 [25,27,29] and a single mutant, Y4796C, in domain 3 [31,33], which were leaky. Co-expression of I4897T with wt RyR1 yielded heterotetrameric channels that were also not leaky [30]. These results confirm that the three mutations we have investigated have the EC-uncoupled phenotype [30].

There are several potential causes for EC uncoupling, including functional defects in either DHPR or RyR1 protein functions, altered membrane trafficking, altered channel assembly and disruption of the interaction between DHPR and RyR1 [14]. Whereas EC-uncoupled RyR1 mutants do not release Ca2+ in response to depolarization of the sarcolemmal membrane [30,31], physical interaction between DHPR and RyR1 proteins is not interrupted, since retrograde signalling is retained. Evidence from previous studies [30,31,36] has implicated alterations of channel function in MH/CCD domain 3 mutants. The present study provides more specific evidence that defects in channel function are related to decreased sensitivity to activating Ca2+, so that the mutant channels release less Ca2+ in response to Ca2+, ATP, pharmacological modulators or depolarization [30,31].

In a ‘skipping model’ of the spatial organization of the triad, alternate RyR1 molecules contact a tetrad of DHPR molecules [51]. Evidence from a previous study shows that RyR1 coupled physically with DHPR requires voltage activation and uncoupled RyR1 is activated by Ca2+ [52]. Thus activation of these RyR1 complexes is initiated by direct interaction with DHPR in 50% of the RyR molecules and the other 50% is activated by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release [1]. In heterozygous CCD skeletal muscles, RyR tetrameric molecules are homo- and heterotetramers of wt and mutant subunits, which should interact randomly with DHPR tetrads. Thus interaction with DHPR probably activates channels with differential Ca2+ release rates ranging from nil to normal, but the overall Ca2+ release would be greatly reduced. Our finding of defects in Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release for these CCD mutants provides new insights into the mechanism, since Ca2+ sensitivity can be restored in heterotetramers, but the peak amplitude of Ca2+ release is not restored. Thus the outcome for EC-uncoupled RyR channels would be a decrease in Ca2+ release with a consequent reduction in muscle strength [14].

Central core formation is also believed to contribute to muscle weakness, although changes in tension are not proportional to changes in morphology [53]. Although increase in resting cytosolic Ca2+ level, due to leaky channels, may contribute to the formation of the core by damaging the mitochondria and myofibrils [11], it is not known how an EC-uncoupled channel causes the same muscle pathology. Animal models of leaky and EC-uncoupled forms of CCD would be helpful in elucidating the mechanisms underlying the clinical phenotypes and pathology of CCD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants MT-3399 and MOP-49403 to D.H.M. from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Neuromuscular Research Partnership Program and by a grant from the Canadian Genetic Diseases Network of Centers of Excellence.

References

- 1.Franzini-Armstrong C., Protasi F. Ryanodine receptors of striated muscles: a complex channel capable of multiple interactions. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:699–729. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ptacek L. J., Tawil R., Griggs R. C., Engel A. G., Layzer R. B., Kwiecinski H., McManis P. G., Santiago L., Moore M., Fouad G., et al. Dihydropyridine receptor mutations cause hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1994;77:863–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkat-Rott K., Lehmann-Horn F., Elbaz A., Heine R., Gregg R. G., Hogan K., Powers P. A., Lapie P., Vale-Santos J. E., Weissenbach J., et al. A calcium channel mutation causing hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:1415–1419. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.8.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monnier N., Procaccio V., Stieglitz P., Lunardi J. Malignant-hyperthermia susceptibility is associated with a mutation of the alpha 1-subunit of the human dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type voltage-dependent calcium-channel receptor in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60:1316–1325. doi: 10.1086/515454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillard E. F., Otsu K., Fujii J., Khanna V. K., de Leon S., Derdemezi J., Britt B. A., Duff C. L., Worton R. G., MacLennan D. H. A substitution of cysteine for arginine 614 in the ryanodine receptor is potentially causative of human malignant hyperthermia. Genomics. 1991;11:751–755. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90084-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii J., Otsu K., Zorzato F., de Leon S., Khanna V. K., Weiler J. E., O'Brien P. J., MacLennan D. H. Identification of a mutation in porcine ryanodine receptor associated with malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1991;253:448–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1862346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts M. C., Mickelson J. R., Patterson E. E., Nelson T. E., Armstrong P. J., Brunson D. B., Hogan K. Autosomal dominant canine malignant hyperthermia is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the skeletal muscle calcium release channel (RYR1) Anesthesiology. 2001;95:716–725. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quane K. A., Healy J. M., Keating K. E., Manning B. M., Couch F. J., Palmucci L. M., Doriguzzi C., Fagerlund T. H., Berg K., Ording H., et al. Mutations in the ryanodine receptor gene in central core disease and malignant hyperthermia. Nat. Genet. 1993;5:51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Chen H. S., Khanna V. K., De Leon S., Phillips M. S., Schappert K., Britt B. A., Browell A. K., MacLennan D. H. A mutation in the human ryanodine receptor gene associated with central core disease. Nat. Genet. 1993;5:46–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mickelson J. R., Louis C. F. Malignant hyperthermia: excitation-contraction coupling, Ca2+ release channel, and cell Ca2+ regulation defects. Physiol. Rev. 1996;76:537–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loke J., MacLennan D. H. Malignant hyperthermia and central core disease: disorders of Ca2+ release channels. Am. J. Med. 1998;104:470–486. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy T. V., Quane K. A., Lynch P. J. Ryanodine receptor mutations in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum. Mutat. 2000;15:410–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200005)15:5<410::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurkat-Rott K., McCarthy T., Lehmann-Horn F. Genetics and pathogenesis of malignant hyperthermia. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:4–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200001)23:1<4::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dirksen R. T., Avila G. Altered ryanodine receptor function in central core disease: leaky or uncoupled Ca(2+) release channels? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2002;12:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galli L., Orrico A., Cozzolino S., Pietrini V., Tegazzin V., Sorrentino V. Mutations in the RYR1 gene in Italian patients at risk for malignant hyperthermia: evidence for a cluster of novel mutations in the C-terminal region. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis M. R., Haan E., Jungbluth H., Sewry C., North K., Muntoni F., Kuntzer T., Lamont P., Bankier A., Tomlinson P., et al. Principal mutation hotspot for central core disease and related myopathies in the C-terminal transmembrane region of the RYR1 gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2003;13:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monnier N., Ferreiro A., Marty I., Labarre-Vila A., Mezin P., Lunardi J. A homozygous splicing mutation causing a depletion of skeletal muscle RYR1 is associated with multi-minicore disease congenital myopathy with ophthalmoplegia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zorzato F., Yamaguchi N., Xu L., Meissner G., Muller C. R., Pouliquin P., Muntoni F., Sewry C., Girard T., Treves S. Clinical and functional effects of a deletion in a COOH-terminal lumenal loop of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:379–388. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tammaro A., Bracco A., Cozzolino S., Esposito M., Di Martino A., Savoia G., Zeuli L., Piluso G., Aurino S., Nigro V. Scanning for mutations of the ryanodine receptor (RYR1) gene by denaturing HPLC: detection of three novel malignant hyperthermia alleles. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:761–768. doi: 10.1373/49.5.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du G. G., Sandhu B., Khanna V. K., Guo X. H., MacLennan D. H. Topology of the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (RyR1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:16725–16730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012688999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Censier K., Urwyler A., Zorzato F., Treves S. Intracellular calcium homeostasis in human primary muscle cells from malignant hyperthermia-susceptible and normal individuals. Effect of overexpression of recombinant wild-type and Arg163Cys mutated ryanodine receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1233–1242. doi: 10.1172/JCI993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wehner M., Rueffert H., Koenig F., Meinecke C. D., Olthoff D. The Ile2453Thr mutation in the ryanodine receptor gene 1 is associated with facilitated calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum by 4-chloro-m-cresol in human myotubes. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsu K., Nishida K., Kimura Y., Kuzuya T., Hori M., Kamada T., Tada M. The point mutation Arg615→hCys in the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum is responsible for hypersensitivity to caffeine and halothane in malignant hyperthermia. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9413–9415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treves S., Larini F., Menegazzi P., Steinberg T. H., Koval M., Vilsen B., Andersen J. P., Zorzato F. Alteration of intracellular Ca2+ transients in COS-7 cells transfected with the cDNA encoding skeletal-muscle ryanodine receptor carrying a mutation associated with malignant hyperthermia. Biochem. J. 1994;301:661–665. doi: 10.1042/bj3010661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong J., Oyamada H., Demaurex N., Grinstein S., McCarthy T. V., MacLennan D. H. Caffeine and halothane sensitivity of intracellular Ca2+ release is altered by 15 calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and/or central core disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26332–26339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang T., Ta T. A., Pessah I. N., Allen P. D. Functional defects in six ryanodine receptor isoform-1 (RyR1) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and their impact on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25722–25730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong J., McCarthy T. V., MacLennan D. H. Measurement of resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and Ca2+ store size in HEK-293 cells transfected with malignant hyperthermia or central core disease mutant Ca2+ release channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:693–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacLennan D. H., Phillips M. S., Zhang Y. The genetic and physiological basis of malignant hyperthermia. In: Schultz S. G., Andreoli T. E., Brown A. M., Fambrough D. J. H., Welsh M. J., editors. Molecular Biology of Membrane Transport Disorders, chapter 10. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avila G., Dirksen R. T. Functional effects of central core disease mutations in the cytoplasmic region of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;118:277–290. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avila G., O'Brien J. J., Dirksen R. T. Excitation-contraction uncoupling by a human central core disease mutation in the ryanodine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4215–4220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071048198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avila G., O'Connell K. M., Dirksen R. T. The pore region of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor is a primary locus for excitation-contraction uncoupling in central core disease. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;121:277–286. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch P. J., Tong J., Lehane M., Mallet A., Giblin L., Heffron J. J., Vaughan P., Zafra G., MacLennan D. H., McCarthy T. V. A mutation in the transmembrane/luminal domain of the ryanodine receptor is associated with abnormal Ca2+ release channel function and severe central core disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monnier N., Romero N. B., Lerale J., Nivoche Y., Qi D., MacLennan D. H., Fardeau M., Lunardi J. An autosomal dominant congenital myopathy with cores and rods is associated with a neomutation in the RYR1 gene encoding the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2599–2608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tilgen N., Zorzato F., Halliger-Keller B., Muntoni F., Sewry C., Palmucci L. M., Schneider C., Hauser E., Lehmann-Horn F., Muller C. R., et al. Identification of four novel mutations in the C-terminal membrane spanning domain of the ryanodine receptor 1: association with central core disease and alteration of calcium homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2879–2887. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao L., Balshaw D., Xu L., Tripathy A., Xin C., Meissner G. Evidence for a role of the lumenal M3–M4 loop in skeletal muscle Ca(2+) release channel (ryanodine receptor) activity and conductance. Biophys. J. 2000;79:828–840. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76339-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du G. G., Guo X., Khanna V. K., MacLennan D. H. Functional characterization of mutants in the predicted pore region of the rabbit cardiac muscle Ca(2+) release channel (ryanodine receptor isoform 2) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31760–31771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen S. R., Ebisawa K., Li X., Zhang L. Molecular identification of the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ sensor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14675–14678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du G. G., Imredy J. P., MacLennan D. H. Characterization of recombinant rabbit cardiac and skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors) with a novel [3H]ryanodine binding assay. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33259–33266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du G. G., Oyamada H., Khanna V. K., MacLennan D. H. Mutations to Gly2370, Gly2373 or Gly2375 in malignant hyperthermia domain 2 decrease caffeine and cresol sensitivity of the rabbit skeletal-muscle Ca2+-release channel (ryanodine receptor isoform 1) Biochem. J. 2001;360:97–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruyama K., MacLennan D. H. Mutation of aspartic acid-351, lysine-352, and lysine-515 alters the Ca2+ transport activity of the Ca2+-ATPase expressed in COS-1 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:3314–3318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fabiato A. Computer programs for calculating total from specified free or free from specified total ionic concentrations in aqueous solutions containing multiple metals and ligands. Methods Enzymol. 1988;157:378–417. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boehning D., Joseph S. K. Functional properties of recombinant type I and type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms expressed in COS-7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:21492–21499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleischer S., Ogunbunmi E. M., Dixon M. C., Fleer E. A. Localization of Ca2+ release channels with ryanodine in junctional terminal cisternae of sarcoplasmic reticulum of fast skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:7256–7259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meissner G. Ryanodine activation and inhibition of the Ca2+ release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6300–6306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu L., Tripathy A., Pasek D. A., Meissner G. Ruthenium red modifies the cardiac and skeletal muscle Ca(2+) release channels (ryanodine receptors) by multiple mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32680–32691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong J., Du G. G., Chen S. R., MacLennan D. H. HEK-293 cells possess a carbachol- and thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store that is responsive to stop-flow medium changes and insensitive to caffeine and ryanodine. Biochem. J. 1999;343:39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meissner G., Darling E., Eveleth J. Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides. Biochemistry. 1986;25:236–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herrmann-Frank A., Luttgau H. C., Stephenson D. G. Caffeine and excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle: a stimulating story. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1999;20:223–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1005496708505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao M., Li P., Li X., Zhang L., Winkfein R. J., Chen S. R. Molecular identification of the ryanodine receptor pore-forming segment. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25971–25974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.25971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block B. A., Imagawa T., Campbell K. P., Franzini-Armstrong C. Structural evidence for direct interaction between the molecular components of the transverse tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum junction in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:2587–2600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klein M. G., Cheng H., Santana L. F., Jiang Y. H., Lederer W. J., Schneider M. F. Two mechanisms of quantized calcium release in skeletal muscle. Nature (London) 1996;379:455–458. doi: 10.1038/379455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shuaib A., Paasuke R. T., Brownell K. W. Central core disease. Clinical features in 13 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]