Abstract

All the archaeal genomes sequenced to date contain a single Type 2 RNase H gene. We found that the genome of a halophilic archaeon, Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, contains an open reading frame with similarity to Type 1 RNase H. The protein encoded by the Vng0255c gene, possessed amino acid sequence identities of 33% with Escherichia coli RNase HI and 34% with a Bacillus subtilis RNase HI homologue. The B. subtilis RNase HI homologue, however, lacks amino acid sequences corresponding to a basic protrusion region of the E. coli RNase HI, and the Vng0255c has the similar deletion. As this deletion apparently conferred a complete loss of RNase H activity on the B. subtilis RNase HI homologue protein, the Vng0255c product was expected to exhibit no RNase H activity. However, the purified recombinant Vng0255c protein specifically cleaved an RNA strand of the RNA/DNA hybrid in vitro, and when the Vng0255c gene was expressed in an E. coli strain MIC2067 it could suppress the temperature-sensitive growth defect associated with the loss of RNase H enzymes of this strain. These results in vitro and in vivo strongly indicate that the Halobacterium Vng0255c is the first archaeal Type 1 RNase H. This enzyme, unlike other Type 1 RNases H, was able to cleave an Okazaki fragment-like substrate at the junction between the 3′-side of ribonucleotide and 5′-side of deoxyribonucleotide. It is likely that the archaeal Type 1 RNase H plays a role in the removal of the last ribonucleotide of the RNA primer from the Okazaki fragment during DNA replication.

Keywords: archaea, catalytic mechanism, Halobacterium, Okazaki fragment, RNA–DNA junction, RNase H

Abbreviations: Halo-RNase HI, Halobacterium RNase HI; RT, reverse transcriptase; ts, temperature-sensitive

INTRODUCTION

RNase H endonucleolytically cleaves only the RNA strand of an RNA/DNA hybrid [1]. RNase H activity has been suggested to be involved in important cellular functions, such as DNA replication, repair and transcription [2–6]. The genes encoding RNase H enzymes have been found in all organisms whose genome sequences have been determined [7,8]. Some organisms have multiple RNase H genes in their genomes. For example, Escherichia coli has two RNase H genes, rnhA encoding RNase HI [9] and rnhB encoding RNase HII [10], which display little amino acid sequence similarity. The RNase HI and HII show differences in specific activities, divalent metal ion preferences and specificities for cleavage sites [7,10,11]. Because these two are not paralogous, RNases H are classified into two major families, Type 1 and Type 2 RNases H based on the amino acid sequence similarities with the two E. coli enzymes [8]. The Type 1 family (E. coli RNase HI orthologues) includes bacterial RNases HI, eukaryotic RNases H1 and retroviral RNase H domains of reverse transcriptases, and the Type 2 family (E. coli RNase HII orthologues) includes bacterial RNases HII and HIII, archaeal RNases HII and eukaryotic RNases H2. The Type 2 RNase H has been found in all of the three domains, whereas the Type 1 RNase H has not been found in archaeal genomes [7,8]. Therefore, the RNase H enzymes of the Type 2 family are more universal than those of the Type 1 family. Database searches carried out by Ohtani et al. [8] showed a single rnh gene encoding Type 2 RNase H per archaeal genome, suggesting that the RNase HII is the only RNase H in archaeal cells [8]. However, presence of multiple rnh genes in some bacterial and all eukaryotic genomes promoted us to investigate Type 1 RNase H genes in archaeal genomes.

As a result of searches on database, we found three hypothetical proteins what could be orthologues of Type 1 RNase H, Vng0255c of Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, PAE1792 of Pyrobaculum aerophilum and ST0753 of Sulfolobus tokodaii. However, amino acid sequences of these putative Type 1 RNase H homologues exhibit the highest similarity to that of Bacillus subtilis RNase HI homologue (YpdQ). Because RNase H activity of the YpdQ protein has never been detected, the activity of these three archaeal proteins remained to be determined. The Vng0255c gene from Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 was chosen for biochemical and enzymic analyses, because only this has a histidine residue in a position that would allow it to function in a manner similar to His124 of E. coli RNase HI. We report here that Vng0255c from Halobacterium exhibits RNase H activity in vivo and in vitro, and is the first Type 1 RNase H gene cloned from archaea.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cells, plasmids and materials

The genome of a halophilic archaeon, Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, was kindly donated by Professor A. Yamagishi (Department of Molecular Biology, Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Science, Hachioji, Japan). The E. coli mutant strains MIC2067 [12] and MIC2067(DE3) [11] have been described elsewhere. The plasmid pET-11a was purchased from Novagen (Madison, WI, U.S.A.). The plasmid pHASH117, which is a derivative from pBR322 [13], and B. subtilis 168 genomic DNA solution were kindly donated by Dr Y. Ohashi and Dr H. Ohshima (Institute for Advanced Biosciences, Keio University, Tsuruoka, Japan). Restriction enzymes and modifying enzymes were from TaKaRa Bio (Kyoto, Japan). Crotalus atrox phosphodiesterase I was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Recombinant E. coli RNase HI was prepared according to the method described by Kanaya et al. [14].

DNA manipulations

PCR was performed for 30 cycles using a GeneAmp PCR system 2700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Reagents for PCR, Ex-Taq HotStart version (TaKaRa Bio) or KOD-Plus (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA sequences were determined by using a Prism 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

In vivo complementation assay for RNase H activity

Plasmid pHASH-Halo1 was constructed for complementation assays by ligating the DNA fragment containing the Halobacterium Vng0255c gene (Halo-rnhA) to the EcoRV site of pHASH117. The DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 genome as a template. The primer sequences were 5′-TATGCCAGTCGTCGAGTGCGACATCCAGAC-3′ for the 5′-primer and 5′-TTCAGGCATCGTCGAGGGCCTCGTTGGCGA-3′ for the 3′-primer. The E. coli mutant strain MIC2067 [12] can form colonies at 30 °C, but not at 42 °C. The temperature-sensitive (ts) growth phenotype can be relieved by introduction of a functional RNase H gene. This strain was transformed with the plasmid pHASH-Halo1, spread on Luria–Bertani medium plates containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and incubated at 30 °C and 42 °C. The plasmid pBR860, which carries the E. coli rnhA gene [15], was used as a positive control, and the pHASH117 was used as a negative control for the complementation experiment.

Plasmid construction, over-expression and purification of Halo-RNase HI (Halobacterium RNase HI)

Plasmid pET-Halo1 for over-expression was constructed by ligating the DNA fragment containing the Halo-rnhA gene to the NdeI–BamHI site of pET-11a. The DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 genomic DNA as a template. The primer sequences were 5′-CGGGGTGACCTGACTCATATGCCAGTCGTCGAGTGC-3′ for the 5′-primer and 5′-GCCGCGTCGGATCCCTTATCAGGCATCGTCGAGGGCCTCGTTGGC-3′ for the 3′-primer, where underlined bases show the positions of the NdeI (5′-primer) and BamHI (3′-primer) sites. For overproduction, E. coli MIC2067(DE3) was transformed with pET-Halo1 and grown in Luria–Bertani medium containing 0.1% glucose, 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, at 30 °C. When the D600 of the culture reached around 0.5, isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside was added to the culture medium (final concentration, 0.3 mM) and induction was continued for an additional 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 g for 5 min. The following protein purification was carried out at 4 °C. Cells were suspended in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA (TE buffer), disrupted by sonication with an ultrasonic disruptor UD-201 from Tomy Corp. (Tokyo, Japan), and centrifuged at 30000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was applied to a column (4 ml) of DE52 (Whatman, Fairfield, NJ, U.S.A.) equilibrated with TE buffer. The protein was eluted from the column by a linear gradient of NaCl from 0 to 0.5 M in TE buffer. The Vng0255c protein-containing fractions at an NaCl concentration of 0.2 M were pooled and dialysed against 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). The dialysed solution was applied to a column (4 ml) of hydroxyapatite Bio-Gel HT gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.) equilibrated with 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), followed by elution from the column by a linear gradient of sodium phosphate from 5 to 200 mM. Fractions containing the protein were pooled, dialysed against 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and applied to a column (4 ml) of Toyopearl SuperQ-650M (Tosoh Corp., Yamaguchi, Japan) equilibrated with 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5). Fractions at around 0.2 M NaCl, eluted by a 0–0.5 M linear NaCl gradient, contained the pure protein. They were combined, concentrated and used for further analyses.

Plasmid construction, over-expression and purification of a B. subtilis RNase HI homologue

The plasmid pET-Bsu1 used for the over-expression studies was constructed by ligating the DNA fragment containing the ypdQ gene to the NdeI–BamHI site of pET-11a. The DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using B. subtilis 168 genomic DNA as a template. The primer sequences were 5′-AAGGAGTTCCATATGCCTACAGAAATATAT-3′ for the 5′-primer and 5′-GCGCGCGGATCCTTATTAATTCTTTTCATTCAG-3′ for the 3′-primer, where underlined bases show the positions of the NdeI (5′-primer) and BamHI (3′-primer) sites. Overproduction of the B. subtilis RNase HI homologue (YpdQ) in E. coli MIC2067(DE3) and sonication lysis were carried out by a procedure similar to that described above for Halo-RNase HI. The supernatant obtained after sonication lysis was applied to a column (4 ml) of DE52 (Whatman) equilibrated with TE buffer (pH 8.0). The flow-through fraction containing the protein was dialysed against 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) and applied to a column (4 ml) of hydroxyapatite Bio-Gel HT gel (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). The protein was eluted from the column by a linear gradient of sodium phosphate from 5 to 200 mM. Fractions around 70 mM sodium phosphate containing the pure YpdQ protein were combined, concentrated and used for further analyses.

Cleavage of oligomeric substrates

The end-labelled RNA strands and the complementary DNAs were chemically synthesized by Proligo (Paris, France). A fluorescent tag (6-carboxy-fluorescein) was used for the end-labelling of the RNA strands. The RNA/DNA duplexes (0.5 μM) were prepared by hybridizing the end-labelled RNA strands with a 2.0 molar equivalent of complementary DNA oligomers. The sequences of substrates are shown in Table 1. Hydrolysis of the substrate was carried out at 37 °C for 15 min in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) containing 10 mM MnCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μg/ml BSA for Halo-RNase HI and B. subtilis YpdQ, and in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μg/ml BSA for E. coli RNase HI. The effect of divalent metal ions on the cleavage activity was analysed in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2, CoCl2, NiCl2, CuCl2, CaCl2 and ZnCl2 in place of MnCl2. The activity at different pH values was measured in a reaction buffer solution containing 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.1–5.2), 10 mM Pipes (pH 6.1–7.3), 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.1–8.8) or 10 mM glycine/NaOH (pH 8.3–10.0). Products were analysed on a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and quantified using the Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad). When the hybrid duplex in which RNA is 5′-end labelled was used as a substrate, products were identified by comparing their patterns of migration on the gel with those of the oligonucleotides generated by partial digestion of RNA with snake venom phosphodiesterase [16]. One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme required to hydrolyse 1 μmol substrate per min at 37 °C. The specific activity was defined as the enzymic activity per mg of protein.

Table 1. Oligomeric RNA/DNA substrates.

Deoxyribonucleotides and ribonucleotides are shown by uppercase and lowercase letters respectively. The asterisk indicates the fluorescently-labelled site.

| Substrate | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 12-bp RNA/DNA | 5'-*cggagaugacgg-3' |

| 3'-GCCTCTACTGCC-5' | |

| RNA9–DNA/DNA | 5'-uugcaugccTGCAGGTCG*-3' |

| 3'-AACGTACGGACGTCCAGC-5' | |

| RNA1–DNA/DNA | 5'-cTGCAGGTCG*-3' |

| 3'-AACGTACGGACGTCCAGC-5' |

Substrate specificity

The 12-bp double-stranded RNA and DNA, and the RNA/DNA duplex with 5′-end-labelled DNA for DNase H activity which cleaves a DNA strand of the RNA/DNA hybrid, were prepared as described for the construction of the RNA/DNA hybrid. The sequences of the 5′-end-labelled strands of all substrates are the same as that of the RNA of the 12-bp RNA/DNA hybrid. The reactions and product analyses were carried out as described above.

Mutagenesis

The genes encoding the mutant proteins were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis, as described previously [17]. They were designed to alter the codon for histidine (CAC) to that for tryptophan (TGG) or alanine (GCA) for Halo-RNase HI mutant proteins, and the codon for Trp109 (TGG) to that for histidine (CAT) for B. subtilis YpdQ-W109H. Plasmids for the over-expression of mutant proteins were constructed by ligating the DNA fragments to the NdeI–BamHI site of pET-11a. The Halo-RNase HI and B. subtilis YpdQ mutant proteins were overproduced and purified as described for the wild-type proteins.

Protein purity and concentration

The purity of each protein was determined by SDS/PAGE on 15% polyacrylamide gel followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The protein concentrations were determined from the extent of UV absorption with A2800.1% values of 1.22 for Halo-RNase HI wild-type, 1.47 for Halo-H179W (Halo-RNase HI where His124→Trp), 0.57 for B. subtilis YpdQ, 0.22 for YpdQ-W109H and 2.02 for E. coli RNase HI. The value for E. coli RNase HI was experimentally determined [18]. Other values were calculated by using ε values of 1576 M−1·cm−1 for tyrosine and 5225 M−1·cm−1 for tryptophan at 280 nm [19].

RESULTS

RNase HI homologue from Halobacterium sp. NRC-1

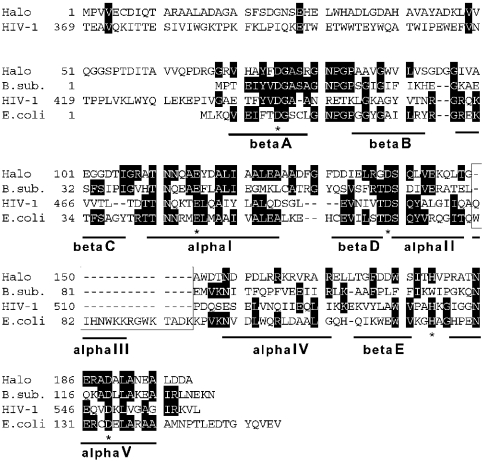

When RNase H homologue genes were searched by BLASTP from the genomic database of Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 [20], two genes with high scores were found. One was the rnh gene encoding an archaeal RNase HII (Type 2 RNase H) orthologue, which is typically found in other archaeal genomes. The other was the Vng0255c gene that has been annotated as a hypothetical protein. The protein encoded by the Vng0255c gene, comprising 199 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of 20980 Da and an isoelectric point (pI) of 4.20, shows significant identity in amino acid sequence with those of Type 1 RNases H, for example, 33% with E. coli RNase HI (Figure 1). Detailed comparison with that of E. coli RNase HI revealed two unusual sequence characteristics, an N-terminal extension and lack of the region corresponding to the basic protrusion [21]. Although Vng0255c has an N-terminal extension as found in eukaryotic RNases H1 [22], the amino acid sequence similarity between the extended regions is negligible. The basic protrusion is important for substrate binding in E. coli RNase HI [23]. In addition, absence of the basic protrusion renders the proteins inactive, as observed in the RNase H domains of retroviral reverse transcriptases (RTs) [24–26] and in an inactive RNase HI homologue (YpdQ) from B. subtilis [7]. The Vng0255c from Halobacterium showed 34% amino acid sequence identities with B. subtilis YpdQ. The amino acid residues involved in divalent metal-ion binding and catalytic function, corresponding to Asp10, Glu48, Asp70, His124 and Asp134 of E. coli RNase HI [27], were all conserved in the Vng0255c (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Multiple alignments of Type 1 RNase H sequences.

Halo, B.sub., HIV-1, and E.coli represent Halobacterium Vng0255c (Halo-RNase HI), B. subtilis YpdQ, an RNase H domain of HIV-1 RT and E. coli RNase HI respectively. Numbers represent the positions of amino acid residues that start from the initiator methionine for each protein. The asterisks indicate the conserved amino acid residues, which are involved in catalytic function of E. coli RNase HI. Lines below the sequences indicate the secondary structure of E. coli RNase HI [42]. The boxed region forms a basic protrusion in the E. coli RNase HI structure.

Complementation assay

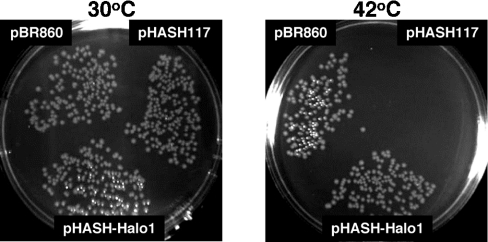

E. coli MIC2067 shows an RNase H-dependent ts growth defect [12]. It grows normally at 30 °C, but is unable to form colonies at 42 °C. To examine whether the Halobacterium Vng0255c gene complements the ts phenotype of this strain, MIC2067 was transformed with pHASH-Halo1, in which the expression level of the Vng0255c was controlled by the promoter Pspac and the SD sequence (AAAGGAGG) of the parental plasmid [13]. As shown in Figure 2, the resultant MIC2067 transformants formed colonies at 42 °C, suggesting that the Halo-RNase HI exhibits enzymic activity in vivo. Because the Vng0255c protein also exhibited an RNase H activity in vitro, as described below, we will refer to this protein as RNase HI (Halo-RNase HI), while the Vng0255c gene is designated rnhA.

Figure 2. Effect of Halo-rnhA on the ts growth of E. coli mutant MIC2067.

MIC2067 cells transformed with each plasmid were incubated on a Luria–Bertani plate containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, at either 30 °C or 42 °C. The plasmids pHASH-Halo1 and pBR860 contain Halo-rnhA and E. coli rnhA genes respectively. The plasmid pHASH117 was examined as a negative control.

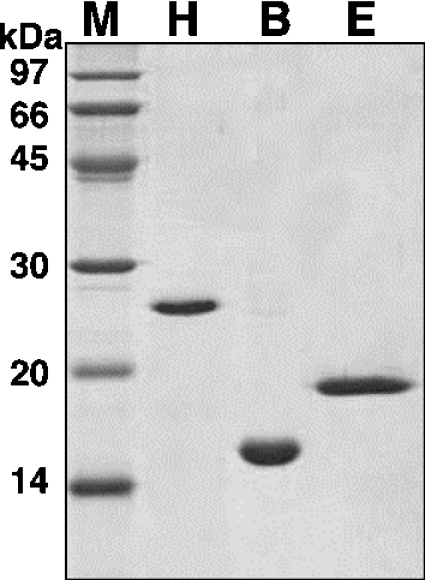

Over-expression and purification

We used E. coli MIC2067(DE3), in which λ(DE3) is integrated into the chromosome, to over-express a gene in the pET vector [11], as a host for overproduction of Halo-RNase HI or B. subtilis YpdQ. The λ(DE3) is a recombinant phage carrying the cloned T7 RNA polymerase gene for T7 promoter of the pET vector. The protein purified from this strain must be free from E. coli RNase HI and HII, because both the rnhA and rnhB genes of MIC2067(DE3) were disrupted. The production levels of the recombinant Halo-RNase HI and B. subtilis YpdQ were estimated to be roughly 25 and 30 mg/l of culture respectively, and these levels were sufficient for monitoring the purification steps. Most of each protein was accumulated intracellularly in a soluble form. The proteins were purified to apparent homogeneity (Figure 3), as described in the Experimental section. The amount of the protein purified from 1 litre of culture was approx. 10 and 14 mg for Halo-RNase HI and B. subtilis YpdQ respectively.

Figure 3. SDS/PAGE of the purified proteins.

All recombinant proteins were purified as described in the Experimental section. Samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE (15% gel) and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue: M, low-molecular-mass standards kit (Amersham); H, Halobacterium Vng0255c (Halo-RNase HI); B, B. subtilis YpdQ; E, E. coli RNase HI. Molecular masses are indicated on the left-hand side of the gel.

In vitro assay for RNase H activity

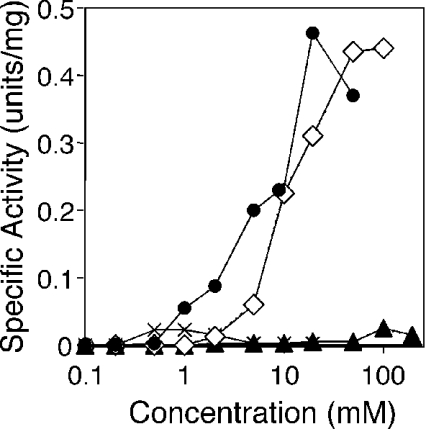

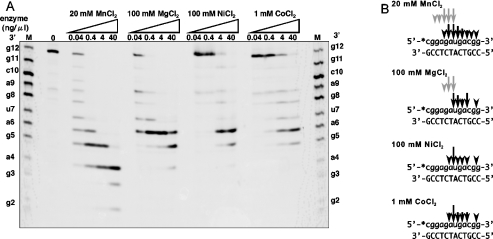

The assay for RNase H activity was carried out as described in the Experimental section using the 12-bp RNA/DNA hybrid molecule as a substrate. Halo-RNase HI exhibited activity in the presence of Mn2+, Mg2+, Co2+ and Ni2+, but not in the presence of Cu2+, Ca2+ or Zn2+ or in the absence of the divalent metal ions. As shown in Figure 4, Halo-RNase HI showed maximal activity at 20, 100, 1 and 100 mM in the presence of MnCl2, MgCl2, CoCl2 and NiCl2 respectively, and preferred MnCl2 and MgCl2 to CoCl2 and NiCl2. The specific activities determined in the presence of 20 mM MnCl2 or 100 mM MgCl2 were approx. 20-fold higher than those in the presence of 1 mM CoCl2 or 100 mM NiCl2 (Figure 4). Cleavage patterns in the presence of 20 mM MnCl2, 100 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CoCl2 or 100 mM NiCl2 are shown in Figure 5. Halo-RNase HI preferred to cleave the substrate at all cleavable sites from g5 to c10 in each of the metal ions tested. However, in the presence of MnCl2, cleavages were observed at all phosphodiester bonds, except for c1–g2. In the presence of MgCl2, CoCl2 or NiCl2, no cleavages were observed at c1–g2, g2–g3, g3–a4 and c10–g11. The same substrate was cleaved by E. coli RNase HI at a6–u7, u7–g8 and a9–c10, as described previously [7,28].

Figure 4. Effect of the divalent metal ion concentrations on the Halo-RNase HI activity.

The activities were determined at 37 °C for 15 min with Halo-RNase HI in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) containing 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 μg/ml BSA, and various concentrations of MnCl2 (•), MgCl2 (⋄), NiCl2 (▴), or CoCl2 (×), by using a 12-bp RNA/DNA hybrid as a substrate. The errors, which represent the 67% confidence limits, are within 30% of the values reported.

Figure 5. Cleavage of oligomeric RNA/DNA substrates in the presence of various divarent metal ions by Halo-RNase HI.

(A) A 12-bp RNA/DNA hybrid was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min with Halo-RNase HI in the presence of 20 mM MnCl2, 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NiCl2 or 1 mM CoCl2. The concentration of the substrate is 0.5 μM. Products were separated on a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea, as described in the Experimental section. M represents products resulting from partial digestion of the 12-bp RNA with snake venom phosphodiesterase. (B) Cleavage sites of the substrates are denoted by arrows. Differences in the size of the arrows reflect the relative cleavage intensities at the indicated position. Black and grey arrows represent the first cleavage sites and the following cleavage sites respectively. Deoxyribonucleotides and ribonucleotides are denoted with uppercase and lowercase letters respectively.

The cleavage activities of Halo-RNase HI in the presence of 10 mM MnCl2 or 100 mM MgCl2 increased exponentially as the pH increased from 4 to 10. The activity seemed to be almost proportional to the concentration of hydroxyl ions. The activity of Halo-RNase HI remained between 70 and 100% at concentrations of NaCl or KCl ranging from 0 to 2.5 M. Because the solubility of divalent metal ions decreased and RNA/DNA substrates might be destabilized at high pH conditions, a pH of 8.5 in the presence of 10 mM MnCl2 was adopted as the standard cleavage reaction.

The specific activities of Halo-RNase HI in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ are compared with those of E. coli RNase HI in Table 2. In the presence of Mg2+, the specific activity of the Halo-RNase HI was 40-fold lower than that of E. coli RNase HI.

Table 2. Comparison of the specific activities of the enzymes in the presence of either Mg2+ or Mn2+ ions.

The hydrolysis of the 12-bp RNA/DNA hybrids with enzyme was carried out at 37 °C for 15 min under the conditions described in the Experimental section. The concentrations of the metal ions were optimal values for RNase H activities of enzymes. B. subtilis YpdQ exhibited no RNase H activity under any examined conditions. Errors, which represent the 67% confidence limits, are within 30% of the values reported.

| Enzyme | Metal | Specific activity (units/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Halo-RNase HI | MgCl2 (100 mM) | 0.44 |

| MnCl2 (20 mM) | 0.46 | |

| E. coli RNase HI | MgCl2 (10 mM) | 17.4 |

| MnCl2 (1 μM) | 0.68 | |

| B. subtilis YpdQ | MgCl2 (10 mM) | <0.0001 |

| MnCl2 (10 mM) | <0.0001 |

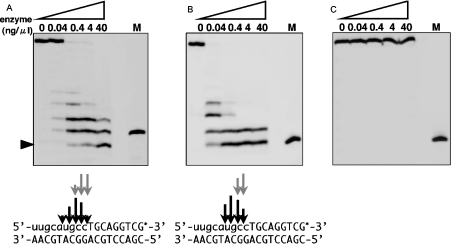

The 3′-end-labelled RNA–DNA/DNA substrates containing one or nine ribonucleotide(s) were also examined. These substrates were used as a model substrate of the RNA primer of the Okazaki-fragment during lagging strand synthesis in DNA replication. When the substrate containing one ribonucleotide was used, neither Halo-RNase HI nor E. coli RNase HI cleaved its RNA–DNA junction (data not shown). When the substrate containing 9-mer ribonucleotides was used, Halo-RNase HI cleaved the RNA–DNA junction in contrast to no cleavage by E. coli RNase HI (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Cleavage of Okazaki fragment-like substrate.

Hydrolysis of the 3′-end-labelled RNA–DNA containing 9-mer RNA hybridized to the cDNA by Halo-RNase HI (A), E. coli RNase HI (B) or B. subtilis YpdQ (C). The RNA–DNA/DNA hybrids were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min with Halo-RNase HI or B. subtilis YpdQ in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) containing 10 mM MnCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μg/ml BSA, or with E. coli RNase HI in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μg/ml BSA. Product separation was carried out as described in the legend for Figure 5. M represents the 3′-end-labelled RNA–DNA containing one ribonucleotide. Then, one base shorter product (black arrowhead) than M shows that the RNA–DNA junction of the RNA9–DNA/DNA substrate has been cleaved. Cleavage sites are shown as described in Figure 5(B).

Substrate specificities

A series of 12-mer single-stranded RNA and DNA, double-stranded RNA and DNA, and RNA/DNA hybrid labelled at the 5′-end of DNA, were incubated with the enzyme in the presence of 10 mM MnCl2 or 100 mM MgCl2. No cleavage for these substrates by the Halo-RNase HI (results not shown) indicated that Halo-RNase HI specifically cleaves the RNA strand of the RNA/DNA hybrid.

Comparison with B. subtilis RNase HI homologue

Although B. subtilis YpdQ shows 34% amino acid sequence identity with Halo-RNase HI, it exhibited neither RNase H nor other nuclease activity [7]. Re-examination of the highly purified recombinant B. subtilis YpdQ used in the present study confirmed the previous results [7] under all reaction conditions (Table 2 and Figure 6C). The all-or-none RNase H activity between Halo-RNase HI and B. subtilis YpdQ could be attributed to the replacement of the histidine residue at the position equivalent to His124 for E. coli RNase HI. His124 is part of the active site and is conserved in other active Type 1 RNases H, including the Halo-RNase HI, but replaced by tryptophan in B. subtilis YpdQ (Figure 1). Mutant proteins Halo-RNase HI H179W and B. subtilis YpdQ W109H (Trp109→His in B. subtilis YpdQ) were constructed and purified to examine the effect of the His→Trp replacement on RNase H activity. B. subtilis YpdQ-W109H showed no gain of RNase H activity. The far- and near-UV CD spectra of the YpdQ-W109H and those of the wild-type protein showed little difference, suggesting that both proteins are similarly folded (results not shown). In contrast, conversion of histidine into tryptophan for Halo-H179W resulted in a level of RNase H activity similar to that of the wild-type Halo-RNase HI. Because the difference of RNase H activity between the wild-type E. coli RNase HI and H124A mutant increased dramatically as the pH decreased [29], the influence of pH on the RNase H activities of the wild-type Halo-RNase HI and H179W mutant was also analysed. However, their activity-pH profiles were almost the same (results not shown). This suggested that the histidine residue at this position is not important for the catalytic mechanism of Halo-RNase HI. Halo-RNase HI contains four more His residues, His29, His33, His40 and His71, at its N-terminal extension (Figure 1). Although we examined a possible contribution of other histidine residues to RNase H activity in vitro using five constructed His→Ala mutant proteins containing H179A, the results suggested that none of these histidine residues were likely to be involved in the catalytic function for Halo-RNase HI (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

Halo-RNase HI

Vng0255c, a Type 1 RNase H homologue, was identified in the Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 genome, and its gene product exhibited RNase H activity both in vivo and in vitro. The Vng0255c product is an RNase H, and the gene designated as rnhA is the first archaeal Type 1 RNase H gene to produce an active enzyme. This result suggests that, in addition to bacterial and eukaryotic genomes, some archaeal genomes also contain the Type 1 RNase H gene. Halo-RNase HI cleaved the 12-bp RNA/DNA substrate at multiple sites, and appeared to be an exonuclease, as shown in Figure 5. However, it was able to cleave the RNA region of a DNA–RNA–DNA/DNA substrate (results not shown), suggesting that it cleaves the RNA in an endonucleolytic manner. Halo-RNase HI can cleave the RNA–DNA junction of an RNA–DNA/DNA substrate containing a 9-mer ribonucleotides, but cannot cleave the junction of the substrate containing a single ribonucleotide (Figure 6A). Probably, it requires an upstream double-stranded foothold of moderate length to access the RNA–DNA junction. The presence of only a single ribonucleotide at the 5′-side of the RNA–DNA junction will not be sufficient for Halo-RNase HI to access the RNA–DNA junction. However, E. coli RNase HI never cleaves the RNA–DNA junction (Figure 6B). This junction cleavage activity is unique for Halo-RNase HI.

Physiological functions

The physiological function of Halo-RNase HI remains to be determined. One of the proposed functions of RNase H is the removal of RNA primers from the Okazaki fragment during lagging-strand DNA synthesis. It has been reported that the known cellular RNases H could not cleave an RNA–DNA junction, and left one or several ribonucleotide(s) at the 5′-end of the DNA strand in Okazaki fragment-like substrates [3,30,31]. Many studies have indicated that the RNA primers can be completely removed by DNA polymerase I in bacteria [32] or by flap endonuclease in archaea [33] and eukarya [3]. However, the substrate specificity of Halo-RNase HI for cleavage on the RNA–DNA junction was clearly defined as shown in Figure 6(A). This suggests that the enzyme possesses a potential activity to remove the RNA primer completely from the Okazaki fragment.

Why is B. subtilis YpdQ inactive?

Our results showed that the B. subtilis RNase HI homologue (YpdQ) was inactive. Despite its similarity to YpdQ, Halo-RNase HI was active. The major differences between these two proteins are an amino acid substitution at the position corresponding to an active-site His124 for E. coli RNase HI and an N-terminal extension in Halo-RNase HI. However, B. subtilis YpdQ W109H did not exhibit RNase H activity in vitro, but its CD spectra suggested that the wild-type YpdQ and W109H mutant proteins were folded into similar structures. In addition, the B. subtilis ypdQ W109H-mutated gene cannot complement an RNase H-dependent ts growth phenotype of E. coli MIC3001 (N. Ohtani and S. Kanaya, unpublished work). The results of site-directed mutagenesis suggested that a His179 residue in Halo-RNase HI is not involved in catalytic function, unlike that in E. coli RNase HI. Consequently, we conclude that the replacement of histidine by tryptophan was not responsible for the difference in activity between the two proteins.

We constructed a Halo-RNase HI mutant, the first 60 amino acid residues of which are deleted, to examine whether the N-terminal extension is important for its activity. However, the mutant protein was not overproduced in E. coli cells and did not complement the ts growth of E. coli MIC2067 (results not shown). Although the N-terminal extension may be important for the stability of Halo-RNase HI, it remained unclear whether it is important for its activity.

Catalytic mechanism

The amino acid residues (Asp10, Glu48, Asp70, His124 and Asp134) involved in the divalent metal-ion binding and catalytic function of E. coli RNase HI were also conserved in Halo-RNase HI (Figure 1). The results of site-directed mutagenesis on Halo-RNase HI suggested that none of the histidine residues, containing His179 corresponding to the His124 for E. coli RNase HI, influenced RNase H activity. Interestingly, the histidine residue corresponding to the His124 for E. coli RNase HI is not conserved in the RNase H domain of RT of the Gypsy family of retro-elements [34,35] and the recently cloned Corynebacterium glutamicum RNase HI [36]. However, both the RTs of the Gypsy family and C. glutamicum RNase HI exhibit RNase H activity. In E. coli RNase HI, the catalytic mechanisms in the one Mg2+-form [37], one Mn2+-form and two Mn2+-form [38] have been proposed. In the two Mn2+-form (attenuation form), the second metal ion, instead of His124, is proposed to facilitate the formation of an attacking hydroxide ion [38], because the His124→Ala mutation does not seriously affect the activity of E. coli RNase HI at high Mn2+ concentrations allowing the attenuation form [39]. In the case of Halo-RNase HI, the effect of 10 mM MnCl2 in the standard reaction condition was not attenuation, but activation, as shown in Figure 4. Therefore the catalytic mechanism for Halo-RNase HI may be slightly different from that proposed for E. coli RNase HI.

Substrate binding

The RNase H domain of HIV-1 RT is inactive [25,26]. The most notable difference between the inactive domain from HIV-1 and the active E. coli protein is a basic protrusion region, which is present in E. coli, but absent from the HIV-1 homologue. The basic protrusion region has been reported to be important for substrate binding for E. coli RNase HI [23]. However, the basic protrusion-deletion mutant exhibits no Mg2+-dependent RNase H activity, while it maintains an Mn2+-dependent RNase H activity, suggesting that the basic protrusion region is not essential for RNase H activity [40]. Halo-RNase HI also lacked a region corresponding to the basic protrusion and exhibited an RNase H activity both in the presence of MnCl2 and in the presence of MgCl2. Hence, the basic protrusion region is not crucial for the RNase H activity of Type 1 enzymes. In Halo-RNase HI, a region corresponding to an αIV helix of E. coli RNase HI forms a positive-charge cluster consisting of five arginines and one lysine residues (Figure 1). This region may be important for substrate binding for Halo-RNase HI.

Halo-RNase HI homologues and their evolutional relationship

Two archaeal genomes also contain Type 1 RNase HI homologue genes. These are the ST0753 gene from S. tokodaii and PAE1792 gene from P. aerophilum. Furthermore, the Halo-RNase HI homologue genes could be also found in the bacterial and eukaryotic genomes (Table 3). A common feature among them is the lack of a basic protrusion region as in the RNase H domain of retroviral RT. This led us to speculate that these Type 1 RNase H homologues might be derived by horizontal gene transfer through a retrovirus. The working hypothesis may explain the clear contrast that cellular Type 1 RNases H cannot cleave the Okazaki fragment-like substrate at the RNA–DNA junction, but Halo-RNase HI possesses similar activity to that of HIV-1 RT [41]. Further analyses of other Type 1 RNase H homologues containing archaeal RNase HI (as listed in Table 3) will help to clarify their origins and their relationship with retrovirus RT.

Table 3. Halo-RNase HI homologues.

| Organism | Gene name |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| B. subtilis | ypdQ* |

| Enterococcus faecalis | ebsB |

| Leptospira interrogans | rnhA |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Rv2228c† |

| Mycobacterium leprae | ML1637† |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | SCO2299† |

| Streptomyces avermitilis | SAV5877† |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | rnhA (Cgl2236)†‡ |

| Corynebacterium efficiens | CE2133† |

| Thermobifida fusca | Tfus2822† |

| Archaea | |

| Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 | Halo-rnhA (Vng0255c) |

| Sulfolobus tokodaii | ST0753 |

| Pyrobaculum aerophilum | PAE1792 |

| Eukarya | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | At3g01410 (putative RNase H) |

| Oryza sativa | OSJNBb0011A08.1 (putative RNase) |

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Dr R.J. Crouch, Dr S. Cerritelli and Dr M. Haruki for useful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr A. Kanai and Dr A. Itoh for helpful discussions; Ms. T. Sugawara for technical assistance; and all Institute for Advanced Biosciences members for encouragement. This research was partially supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, grant-in-aid for the 21st Century Center of Excellence (COE) Program entitled ‘Understanding and Control of Life's Function via Systems Biology (Keio University)’ and a grant from New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan (Development of a Technological Infrastructure for Industrial Bioprocesses Project).

References

- 1.Crouch R. J., Dirksen M.-L. Ribonucleases H in Nuclease. In: Linn S. M., Crouch R. J., editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kogoma T., Foster P. L. Physiological function of E. coli RNase HI. In: Crouch R. J., Toulme J. J., editors. Ribonucleases H. Paris: INSERM; 1998. pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu J., Qian Y., Frank P., Wintersberger U., Shen B. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase H(35) functions in RNA primer removal during lagging-strand DNA synthesis, most efficiently in cooperation with Rad27 nuclease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:8361–8371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumbaugh J. A., Murante R. S., Shi S., Bambara R. A. Creation and removal of embedded ribonucleotides in chromosomal DNA during mammalian Okazaki fragment processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22591–22599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drolet M., Phoenix P., Menzel R., Masse E., Liu L. F., Crouch R. J. Overexpression of RNase H partially complements the growth defect of an Escherichia coli Δ topA mutant: R-loop formation is a major problem in the absence of DNA topoisomerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:3526–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arudchandran A., Cerritelli S., Narimatsu S., Itaya M., Shin D. Y., Shimada Y., Crouch R. J. The absence of ribonuclease H1 or H2 alters the sensitivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to hydroxyurea, caffeine and ethyl methanesulphonate: implications for roles of RNases H in DNA replication and repair. Genes Cells. 2000;5:789–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtani N., Haruki M., Morikawa M., Crouch R. J., Itaya M., Kanaya S. Identification of the genes encoding Mn2+-dependent RNase HII and Mg2+-dependent RNase HIII from Bacillus subtilis: classification of RNases H into three families. Biochemistry. 1999;38:605–618. doi: 10.1021/bi982207z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtani N., Haruki M., Morikawa M., Kanaya S. Molecular diversities of RNases H. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 1999;88:12–19. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanaya S., Crouch R. J. DNA sequence of the gene coding for Escherichia coli ribonuclease H. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:1276–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itaya M. Isolation and characterization of a second RNase H (RNase HII) of Escherichia coli K-12 encoded by the rnhB gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:8587–8591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohtani N., Haruki M., Muroya A., Morikawa M., Kanaya S. Characterization of ribonuclease HII from Escherichia coli overproduced in a soluble form. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2000;127:895–899. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itaya M., Omori A., Kanaya S., Crouch R. J., Tanaka T., Kondo K. Isolation of RNase H genes that are essential for growth of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:2118–2123. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2118-2123.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi Y., Ohshima H., Tsuge K., Itaya M. Far different levels of gene expression provided by an oriented cloning system in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;221:125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanaya S., Kohara A., Miyagawa M., Matsuzaki T., Morikawa K., Ikehara M. Overproduction and preliminary crystallographic study of ribonuclease H from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:11546–11549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haruki M., Noguchi E., Akasako A., Oobatake M., Itaya M., Kanaya S. A novel strategy for stabilization of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI involving a screen for an intragenic suppressor of carboxyl-terminal deletions. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26904–26911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jay E., Bambara R., Padmanabham P., Wu R. DNA sequence analysis: a general, simple and rapid method for sequencing large oligodeoxyribonucleotide fragments by mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 1974;1:331–353. doi: 10.1093/nar/1.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaya S., Oobatake M., Nakamura H., Ikehara M. pH-dependent thermostabilization of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI by histidine to alanine substitutions. J. Biotechnol. 1993;28:117–136. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(93)90129-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanaya S., Kimura S., Katsuda C., Ikehara M. Role of cysteine residues in ribonuclease H from Escherichia coli. Site-directed mutagenesis and chemical modification. Biochem. J. 1990;271:59–66. doi: 10.1042/bj2710059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodwin T. W., Morton R. A. The spectrophotometric determination of tyrosine and tryptophan in proteins. Biochem. J. 1946;40:628–632. doi: 10.1042/bj0400628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng W. V., Kennedy S. P., Mahairas G. G., Berquist B., Pan M., Shukla H. D., Lasky S. R., Baliga N. S., Thorsson V., Sbrogna J., et al. Genome sequence of Halobacterium species NRC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:12176–12181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190337797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katayanagi K., Miyagawa M., Matsushima M., Ishikawa M., Kanaya S., Nakamura H., Ikehara M., Matsuzaki T., Morikawa K. Structural details of ribonuclease H from Escherichia coli as refined to an atomic resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;223:1029–1052. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90260-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerritelli S. M., Fedoroff O. Y., Reid B. R., Crouch R. J. A common 40 amino acid motif in eukaryotic RNases H1 and caulimovirus ORF VI proteins binds to duplex RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1834–1840. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanaya S., Katsuda-Nakai C., Ikehara M. Importance of the positive charge cluster in Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI for the effective binding of the substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11621–11627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies J. F., 2nd, Hostomska Z., Hostomsky Z., Jordan S. R., Matthews D. A. Crystal structure of the ribonuclease H domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1991;252:88–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1707186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becerra S. P., Clore G. M., Gronenborn A. M., Karlstrom A. R., Stahl S. J., Wilson S. H., Wingfield P. T. Purification and characterization of the RNase H domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase expressed in recombinant Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1990;270:76–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81238-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hostomsky Z., Hostomska Z., Hudson G. O., Moomaw E. W., Nodes B. R. Reconstitution in vitro of RNase H activity by using purified N-terminal and C-terminal domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:1148–1152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanaya S. Enzymatic activity and protein stability of E. coli ribonuclease HI. In: Crouch R. J., Toulme J. J., editors. Ribonucleases H. Paris: INSERM; 1998. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanaya E., Kanaya S. Kinetic analysis of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI using oligomeric DNA/RNA substrates suggests an alternative mechanism for the interaction between the enzyme and the substrate. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;231:557–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0557d.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kashiwagi T., Jeanteur D., Haruki M., Katayanagi K., Kanaya S., Morikawa K. Proposal for new catalytic roles for two invariant residues in Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI. Protein Eng. 1996;9:857–867. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.10.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eder P. S., Walder R. Y., Walder J. A. Substrate specificity of human RNase H1 and its role in excision repair of ribose residues misincorporated in DNA. Biochimie. 1993;75:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90033-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chai Q., Qiu J., Chapados B. R., Shen B. Archaeoglobus fulgidus RNase HII in DNA replication: enzymological functions and activity regulation via metal cofactors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;286:1073–1081. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa T., Okazaki T. Function of RNase H in DNA replication revealed by RNase H defective mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1984;193:231–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00330673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato A., Kanai A., Itaya M., Tomita M. Cooperative regulation for Okazaki fragment processing by RNase HII and Fen-1 purified from a hyperthermophilic archaeon, P. furiosus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;309:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lener D., Budihas S. R., Le-Grice S. F. Mutating conserved residues in the ribonuclease H domain of Ty3 reverse transcriptase affects specialized cleavage events. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26486–26495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin H. L. An unusual mechanism of self-primed reverse transcription requires the RNase H domain of reverse transcriptase to cleave an RNA duplex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:5645–5654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirasawa T., Kumagai Y., Nagai K., Wachi M. A Corynebacterium glutamicum rnhA recG double mutant showing lysozyme-sensitivity, temperature-sensitive growth, and UV-Sensitivity. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003;67:2416–2424. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanaya S., Oobatake M., Liu Y. Thermal stability of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI and its active site mutants in the presence and absence of the Mg2+ ion. Proposal of a novel catalytic role for Glu48. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32729–32736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsunaka Y., Haruki M., Morikawa M., Oobatake M., Kanaya S. Dispensability of Glu48 and Asp134 for Mn2+-dependent activity of E. coli ribonuclease HI. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3366–3374. doi: 10.1021/bi0205606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keck J. L., Goedken E. R., Marqusee S. Activation/attenuation model for RNase H. A one-metal mechanism with second-metal inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34128–34133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keck J. L., Marqusee S. The putative substrate recognition loop of Escherichia coli ribonuclease H is not essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19883–19887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotte M., Maier G., Onori A. M., Cellai L., Wainberg M. A., Heumann H. Temporal coordination between initiation of HIV+-strand DNA synthesis and primer removal. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11159–11169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katayanagi K., Miyagawa M., Matsushima M., Ishikawa M., Kanaya S., Ikehara M., Matsuzaki T., Morikawa K. Three-dimensional structure of ribonuclease H from E. coli. Nature (London) 1990;347:306–309. doi: 10.1038/347306a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]