Abstract

Morphological analysis of a conditional yeast mutant in acetyl-CoA carboxylase acc1ts/mtr7, the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid synthesis, suggested that the synthesis of C26 VLCFAs (very-long-chain fatty acids) is important for maintaining the structure and function of the nuclear membrane. To characterize this C26-dependent pathway in more detail, we have now examined cells that are blocked in pathways that require C26. In yeast, ceramide synthesis and remodelling of GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol)-anchors are two pathways that incorporate C26 into lipids. Conditional mutants blocked in either ceramide synthesis or the synthesis of GPI anchors do not display the characteristic alterations of the nuclear envelope observed in acc1ts, indicating that the synthesis of another C26-containing lipid may be affected in acc1ts mutant cells. Lipid analysis of isolated nuclear membranes revealed the presence of a novel C26-substituted PI (phosphatidylinositol). This C26-PI accounts for approx. 1% of all the PI species, and is present in both the nuclear and the plasma membrane. Remarkably, this C26-PI is the only C26-containing glycerophospholipid that is detectable in wild-type yeast, and the C26-substitution is highly specific for the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone. To characterize the biophysical properties of this lipid, it was chemically synthesized. In contrast to PIs with normal long-chain fatty acids (C16 or C18), the C26-PI greatly reduced the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition of liposomes composed of 1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DEPE). The biophysical properties of this lipid are thus consistent with a possible role in stabilizing highly curved membrane domains.

Keywords: 1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; fatty acid; membrane curvature; nuclear pore complex; subcellular membrane; yeast

Abbreviations: DCC, dicyclohexylcarbodi-imide; DEPE, 1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ESI, electrospray ionization; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; LCFA, long-chain fatty acid; nano-ESI-MS/MS, nano-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry; NPC, nuclear pore complex; PI, phosphatidylinositol; C26-PI, sn-1-O-hexacosanoyl-sn-2-O-palmitoyl-PI; PMB, 3-p-methoxybenzyl; PS, phosphatidylserine; TH, bilayer to hexagonal phase transition temperature; TM, Lβ to Lα phase transition temperature; (V)LCFA, (very-)long-chain fatty acid

INTRODUCTION

Cell membranes are complex macromolecular assemblies of lipids and proteins. Although the various possible functions of lipids in this assembly are yet to be completely understood, work from the last decade indicates that lipids serve a more organizing function than had initially been supposed [1]. For example, different subcellular membranes have different lipid compositions and even within the same membrane, different types of lipids may be asymmetrically distributed between the two halves of the lipid bilayer [2]. Moreover, within the plane of the membrane different lipids can display a surprising degree of lateral organization [3]. These domain-forming properties of different types of lipids appear to be functionally important, as indicated, for example, by the observation that microdomains formed by the association of sphingolipids and cholesterol can serve to concentrate interacting proteins and thereby might assist in the sorting of membrane-anchored proteins along their trafficking pathways [4].

The physicochemical membrane parameters more generally affect the function of integral membrane proteins. For example, protein transmembrane domains are thought to interact preferentially with lipids of matching acyl chain length [5]. Such protein–membrane interactions are thus sensitive to subtle changes in the lipid composition of the membrane. Thus, in vivo, the fatty acid acyl chain length, degree of unsaturation and the nature of the lipid head group are important parameters that can modify the structure and function of integral membrane proteins [6].

The NPC (nuclear pore complex) is a giant protein-aqueous channel that spans the outer and inner nuclear membranes of eukaryotic cells [7]. The NPC itself is anchored to the nuclear envelope by integral membrane proteins that define the ‘pore membrane’ domain of the NPC [8]. Even though the precise organization of the membrane around the NPC is not known, it is generally assumed that inner and outer nuclear membranes are continuous with each other and that they form a 180° turn at the NPC [9].

A connection between fatty acid synthesis and the structure of the nuclear envelope in yeast is suggested by the observation that a conditional yeast acetyl-CoA carboxylase mutant, acc1ts/mtr7, affects the structure and function of the nuclear envelope/NPC [10–12]. acc1ts/mtr7 mutant cells are defective in nuclear mRNA transport and display a severe perturbation of the nuclear envelope, characterized by the separation of the inner and outer nuclear membranes and the formation of vesicles within the inter-membrane space. Similar structural defects were observed in mutants in NPC protein (nucleoporins), such as members of the Nup84 complex [13–15].

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Acc1p, is the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid synthesis. It catalyses the ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which then serves as the two-carbon-unit donor for the synthesis of LCFAs (long-chain fatty acids). The fact that the temperature-sensitive growth phenotype of acc1ts and the lethality of an acc1Δnull allele are not rescued by LCFA supplementation indicated that malonyl-CoA is required for a second essential function that is independent of the synthesis of LCFAs [10–12,16]. This second function of Acc1 is to provide malonyl-CoA for the elongation of LCFAs to VLCFAs (very-LCFAs) by an ER (endoplasmic reticulum)-bound elongation complex [17]. Since neither fatty acid auxotrophic acc1 mutant cells nor wild-type cells treated with cerulenin, an inhibitor of the fatty acid synthetase, display the nuclear envelope alteration characteristic of acc1ts, we proposed that VLCFA synthesis is required for a functional nuclear envelope [10–12,16]. This proposition is supported by the observation that supplementation of acc1ts mutant cells with C16 and/or C18 LCFAs does not rescue the defect in mRNA transport. Taken together, these observations indicate that an as-yet-uncharacterized VLCFA-dependent process might be important to maintain the structure and function of the yeast nuclear membrane, and that a block in this process, as caused by acc1ts, results in the phenotypic alterations of the nuclear membrane [10,11].

C26 is the major VLCFA in yeast. It comprises 1–2% of the total fatty acid composition. The C26 acyl chain is an important structural component of the ceramide moiety of sphingolipids and GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol)-anchored proteins, of which the synthesis of both is essential in yeast. The significance of the very long acyl chain of ceramide is underlined by the observation that strains with a dominant allele in an acyl transferase (SLC1-1; sphingolipid compensation) bypass the essential requirement for ceramide by synthesizing novel inositol glycerophospholipids substituted with a C26 fatty acid in the sn-2 position of the glycerol. In addition, this PI (phosphatidylinositol) acquires head group modifications typically found only on sphingolipids, and thus structurally and functionally mimics sphingolipids [18,19]. Apart from ceramide, the C26 VLCFA is also present in the lipid moiety of GPI-anchored proteins [20] and the two storage lipids, steryl esters and triacylglycerol [21]. In contrast with GPI anchors [22], neutral lipids are not essential in yeast [23]. An overview of these possible C26-dependent processes is shown in Scheme 1. The aim of the present study was to identify and characterize the C26-dependent processes that may account for the phenotypic alteration of the nuclear envelope in acc1ts mutant cells.

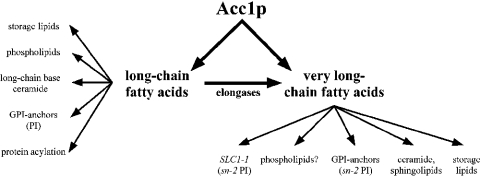

Scheme 1. C26-dependent pathways in yeast.

Schematic overview of pathways that require LCFAs and VLCFAs, and are thus dependent on the function of Acc1p. See the Introduction for more details.

EXPERIMENTAL

Isolation of yeast subcellular membranes

The wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain used for these experiments was YPH259 (MATα ade2-101 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801 trp1-Δ63). The lcb1-100 conditional mutant was RH2607, MATa end8-1 leu2 ura3 his4 bar1 [24]. gpi2-5A (his4 ura3) was kindly given by Dr P. Orlean (Department of Microbiology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, U.S.A.) [25]. Fermenter cultures (10 litre flasks) of YPH259 were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract/2% bactopeptone/2% glucose) at 30 °C to early-exponential phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and were converted into spheroplasts. Nuclei were then enriched by sucrose density-gradient centrifugation as described previously [26]. Plasma membranes were isolated following a procedure described previously [27].

Protein analysis

Before quantification, proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and solubilized in 0.1% (w/v) SDS/0.1 M NaOH. Quantification was performed using the Folin phenol reagent and BSA as the standard. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters (Hybond-C; Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Bucks., U.K.). Relative enrichment and degree of contamination of subcellular fractions was determined by Western blot analysis using the antibodies against the marker proteins (shown in Table 2). Antisera against yeast plasma-membrane ATPase, carboxypeptidase Y and Kar2p were kindly given by: Dr R. Serrano (Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology of Plants, Polytechnic University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain); Dr D. Wolf (Institute of Biochemistry, Stuttgart University, Germany); Dr R. Fuller (Department of Biochemistry, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, U.S.A.); and Dr R. Schekman (Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA, U.S.A.). The antibody against the nucleolar protein Nop1p was obtained from Dr J. Aris (Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, U.S.A.), and the antibody against porin was obtained from Dr G. Daum (Institute of Biochemistry, Technical University of Graz, Graz, Austria).

Table 2. Mild-base-sensitive and mild-base-resistant pools of C26 fatty acids in nuclear and plasma membrane fractions.

Release of C26 fatty acids from isolated nuclear and plasma membrane fractions after mild (0.1 M NaOH, 30 °C, 1 h) or strong (2 M KOH, 80 °C, 16 h) alkaline hydrolysis. The relative amount of C26 is given as mol % of the total fatty acids. Values represent means±S.D. for three independent determinations.

| Membrane | Mild alkaline treatment | Strong alkaline treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma membrane | 1.3±0.3 | 5.6±0.9 |

| Nuclear membrane | 1.6±0.4 | 1.5±0.3 |

Lipid and fatty acid analyses

Lipids were extracted and individual phospholipids were separated by two-dimensional TLC using chloroform/methanol/25% ammonia (65:35:5, v/v) for the first and chloroform/acetone/methanol/acetic acid/water (50:20:10:10:5, v/v) for the second direction. Spots detected after exposure to iodine vapour were scraped off and lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (1:4). Total and individual phospholipids were quantified as described previously [28].

The positional distribution of fatty acids was determined by phospholipase A2 cleavage of individual phospholipids. The lipid was resuspended in a solution containing 100 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100 and 15 units of phospholipase A2 [from the spectacled cobra (Naja naja); Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, U.S.A.] and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Lysophospholipids were then separated from free fatty acids by TLC with chloroform/methanol/water (65:25:4, v/v).

After mild (0.1 M NaOH for 1 h at 30 °C) or strong [2 M KOH in methanol/water (2:1, v/v) for 18 h at 80 °C] alkaline hydrolysis of lipids, fatty acids were converted into methyl esters by BF3-catalysed methanolysis, and separated by GLC on a Hewlett–Packard 5890 equipped with an ultra 2 capillary column (5% diphenyl/95% dimethylpolysiloxane) and FID (flame ionization detector), as described previously [10]. C13 and C23 fatty acids added to each sample before alkaline hydrolysis served as an internal standard. In every experiment, blank samples containing no lipids were processed through all steps of manipulation. Fatty acids were identified using commercial methyl ester standards (NuCheck Inc., Elysian, MN, U.S.A.) and, in selected cases, by GLC–MS analysis using a Hewlett–Packard 8590 II Plus GLC coupled with a Hewlett–Packard 5972 mass selective detector. Samples (1 μl) were injected in the splitless mode; the injector temperature was set to 230 °C, and the detector temperature to 280 °C. Other details were as follows: ionization, 70 eV; scan mode, 35–400 amu; oven temperature was 150 °C for 1 min, followed by a temperature ramp of 10 °C/min to 290 °C for 10 min; helium 5.0 was used as the carrier gas [0.81 bar (1 bar≡105 Pa) at 150 °C, constant flow]; the column was an HP-5MS.

Mass spectrometry

After solvent evaporation, samples were resuspended in methanol and processed further for MS, as described previously [28]. Nano-ESI-MS/MS (nano-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry) analysis performed on a Micromass QII triple-stage quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, U.S.A.) was operated equipped with a nano-ESI source (Z spray) from Micromass. Argon was used as the collision gas at a nominal pressure of 2.5×10−3 mbar. The cone voltage was set to 30 V. Resolution of Q1 and Q3 was set to achieve isotope resolution. Detection of PI was performed by parent ion scanning for fragment ion m/z 241 at collision energy 50 eV; scanning for hexacosanoic acid-containing lipid species was performed by parent ion scanning for fragment ion 395 at a collision energy of 50 eV. Product ion scanning of synthetic PI (26:0/C16:0) was performed by applying a collision energy of 50 eV.

Electron microscopy

For ultrastructural examination, cells were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0, and 1 mM CaCl2 for 90 min at room temperature. Then, cells were washed in buffer with 1 mM CaCl2 for 1 h and incubated for 1 h with a 2% aqueous solution of KMnO4. Fixed cells were washed in distilled water for 30 min and incubated in 1% sodium metaperjodate for 20 min. Samples were rinsed in distilled water for 15 min and post-fixed for 2 h in 2% OsO4 buffered with 0.1 M cacodylate at pH 7.0. After another wash with buffer for 30 min, the samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (50–100%, with en bloc staining in 2% uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol overnight) and embedded in Spurr resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate and viewed with a Philips CM 10 electron microscope.

Synthesis of C26-PI (sn-1-O-hexacosanoyl-sn-2-O-palmitoyl-PI)

Selective acylation and phosphoramidite synthesis was performed as described previously [29]. A mixture of PMB (3-p-methoxybenzyl) glycerol (21 mg, 0.10 mmol), hexacosanoic acid (47 mg, 0.12 mmol) and 4,4-dimethylaminopyridine (1 mg, catalytic amount) were suspended in CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml) and cooled to 0 °C. A solution of DCC (dicyclohexylcarbodi-imide; 27 mg, 0.13 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred overnight slowly, warming to room temperature. The mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite, concentrated, and the 1-acylglyceryl ether was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 25% ethyl acetate/hexane) to obtain a white solid (26 mg, 45%). Next, 16 mg (0.027 mmol) palmitic acid (13 mg, 0.051 mmol) and 4,4-dimethylaminopyridine were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml). DCC (9.0 mg, 0.044 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo and purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 15% ethyl acetate/hexane) to give 21 mg (95%) of the PMB-protected diacylglycerol. Then, oxidative removal of the PMB ether was achieved by dissolving the ether in wet CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml), adding dichlorodicyanoquinone (16 mg, 0.07 mmol) and stirring the mixture overnight at room temperature. The solution was washed with 10% NaHCO3, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated to give the diacylglycerol as a crude white solid (44 mg) in quantitative yield.

Finally, the phosphoramidite was prepared according to literature protocols described previously [29]. Thus sn-1-O-hexacosanoyl-sn-2-O-palmitoylglycerol (25 mg, 0.035 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1.25 ml) and cooled to 0 °C. Di-isopropyl-ethylamine (10 μl, 0.056 mmol) was added, followed by a solution of benzyloxychlorodi-isopropylamine phosphine (26 mg, 0.095 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml). The mixture was stirred for 3 h, while slowly warming to room temperature. It was then diluted with CH2Cl2, extracted with 10% NaHCO3 and then dried over MgSO4. The solution was concentrated to leave an orange oil that was purified by column chromatography [silica gel, hexanes/ethyl acetate/triethylamine (60:10:1)] to leave a white solid (22.5 mg, 68%), which was used within 1 week.

For synthesis of C26-PI, coupling was performed following known protocols [29–31]. Thus 2,3,4,5,6-pentakisbenzyl-1-D-myo-inositol (9.4 mg, 0.015 mmol), which had been resolved as the camphanate ester [32], was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (0.5 ml), tetrazole (5.6 mg, 0.08 mmol) was added, and the solution was cooled to 0 °C. To this cooled solution was added a solution of the diacylglycerol phosphoramidite (22 mg, 0.023 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.5 ml). The mixture was stirred for 2 h, slowly warming to room temperature. The mixture was then cooled to −40 °C (acetonitrile/dry ice) and m-chloroperbenzoic acid (50–80%, 11 mg, 0.04 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred at −40 °C for 30 min, 0 °C for 1 h and then room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2, washed with aqueous NaHCO3, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo and purified twice on silica gel (20% acetone/hexanes) to give 15 mg of a homogeneous protected PI derivative (68%). The purified pentakisbenzyl ester (15 mg, 0.010 mmol) was dissolved in THF:H2O (1.0 ml), palladium-on-carbon (10%, 14.7 mg) was added, and the mixture was stirred under a hydrogen atmosphere for 19 h at room temperature. The mixture was filtered, concentrated, redissolved in water, and lyophilized to give a C26-PI in the phosphoric acid form as a white solid (8 mg, 84%).

Biophysical characterization of the C26-PI

Lipid films for differential scanning calorimetry were prepared from DEPE (1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), with or without the addition of increasing molar fractions of other lipids. The solvent was removed by evaporation with nitrogen. Final traces of organic solvent were removed in a vacuum chamber attached to a liquid nitrogen trap for 2–3 h. The lipid films were hydrated at room temperature by vortex-mixing with 20 mM Pipes buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.14 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.002% sodium azide. The final lipid concentration was 5 mg/ml. Buffer and lipid suspensions were degassed under vacuum before being loaded into the sample or the reference cell, respectively, of a NanoCal high-sensitivity calorimeter (CSC; American Forks, UT, U.S.A.). A heating scan rate of 0.75 K/min was employed. The observed phase transition was fitted with parameters describing an equilibrium with a single van’t Hoff enthalpy and the transition temperature reported as that for the fitted curve. The shift of the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition temperature, occurring at 65 °C for the pure DEPE, provides a measure of the effect of an additive on the curvature properties of the lipid. Data were analysed with the program Origin 5.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A block in ceramide and GPI-anchor biosynthesis does not affect the morphology of the nuclear envelope

Our previous observation of an altered nuclear envelope phenotype in the conditional acc1ts mutant suggested that fatty acid elongation and hence the synthesis of C26 fatty-acid-containing lipids might be important for maintaining a functional nuclear envelope [18]. As ceramide is the major known C26-containing lipid in yeast, we first examined whether a block in ceramide synthesis would result in an altered morphology of the nuclear envelope. Therefore a mutant with a conditional defect in the rate-limiting enzyme of long-chain base synthesis, serine palmitoyltransferase, lcb1-100 [24], was incubated in permissive or non-permissive conditions for 4 h and the cells were examined by transmission electron microscopy. This analysis revealed that lcb1-100 mutant cells had a normal nuclear morphology irrespective of whether they were incubated at permissive or non-permissive conditions, indicating that a block in long-chain-base synthesis does not result in the structural alterations characteristic of acc1ts mutant cells (Figure 1). These observations suggest that ongoing ceramide synthesis is not required for maintaining a functional nuclear envelope, which is consistent with the fact that cells lacking the capacity to synthesize ceramide, due to mutations in LAG1 and LAC1, display no aberrant nuclear morphology [33].

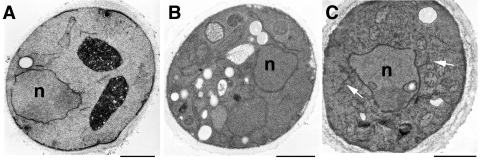

Figure 1. Electron microscopic analysis of cells that are blocked in ceramide- and GPI-anchor-biosynthesis.

Wild-type (YPH259; A), lcb1-100 (B) and gpi2-5A (C) conditional mutant cells were cultivated in minimal media and shifted to 37 °C for 4 h before fixation and processing for electron microscopy. White arrows in (C) point to abnormal membrane extensions. n, nucleus; the scale bar represents 1 μm.

To examine whether a block in GPI-anchor biosynthesis would affect the morphology of the nuclear envelope, a conditional gpi2-5A mutant, which blocks an early step in GPI-anchor biosynthesis (the synthesis of N-acetylglucosaminyl PI [25]), was incubated in permissive or non-permissive conditions for 4 h and the cells were examined by transmission electron microscopy. In approx. 30% of the gpi–5A mutant cells that were shifted to non-permissive conditions, abnormal membrane profiles were observed (Figure 1). Extensions of what appear to be ER membranes were frequently seen to emanate from the nuclear membrane shown by arrows in Figure 1C). However, the clear separation of inner and outer nuclear membrane, that is characteristic of acc1ts, was not observed in the gpi2-5A mutant, indicating that a block in GPI synthesis does not account for the nuclear envelope phenotype observed in acc1ts. Similar extensions of the ER membrane were observed previously in another conditional mutant in GPI synthesis, mcd4-174 [34]. Thus elongated fatty acids, but not sphingolipids or GPI-anchors with elongated fatty acids, appear to be required for a normal nuclear morphology in yeast.

A mild-base-sensitive C26-containing lipid is present in the nuclear and the plasma membranes

In a next step towards examining a possible role of a C26-containing lipid in nuclear membrane integrity, we asked whether yeast nuclear membranes contain any C26-substituted lipids apart from ceramide. Therefore nuclei from wild-type cells were isolated by sucrose density-gradient centrifugation [26]. This nuclear fraction was enriched approx. 14-fold for the nuclear/nucleolar protein Nop1p, and 11-fold for the soluble ER-resident protein Kar2p (Table 1). The major contaminating organelles in these preparations were mitochondria, vacuoles and the plasma membrane, as judged by the 2-fold enrichments for porin, a major protein of the outer mitochondrial membrane, for carboxypeptidase Y, a vacuolar hydrolase, and for the plasma-membrane proton-pumping ATPase (Pma1p). The isolated nuclei appeared to be intact, as visualized by epifluorescence microscopy of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained samples (results not shown).

Table 1. Characterization of yeast nuclear fraction.

Nuclear membranes were isolated from YPH259 wild-type cells. Relative enrichment of marker proteins in the homogenate was set at 1. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: Kar2p, Nop1p, porin, Kex2p, carboxypeptidase Y and plasma membrane ATPase. Values represent averages of six independent preparations.

| Subcellular compartment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear membrane/ER | Mitochondria | Golgi | Vacuole | Plasma membrane | ||

| Marker protein | Kar2p | Nop1p | Porin | Kex2p | Carboxypeptidase Y | ATPase |

| Fold enrichment | 11 | 14 | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 2 |

Lipid extracts prepared from the nuclear fraction were then analysed for the presence of a mild-base-sensitive and mild-base-resistant pool of the C26 fatty acid. Mild alkaline treatment releases hydroxy esterified fatty acids, and is thus an indication that the respective acyl chain is hydroxyl-bound. Hydrolysis of amide-linked acyl groups as typically found in ceramides, on the other hand, requires more stringent hydrolysis conditions (see the Experimental section). Using mild and strong alkaline hydrolysis of lipid extracts from nuclear membranes, we could thus distinguish between ceramide-bound C26 and a mild-base-sensitive, possibly glycerophospholipid-bound, pool of C26. This analysis revealed the presence of a small pool of mild-base-sensitive C26 in the nuclear membrane of yeast, comprising approx. 1.6% of the total mild-base-sensitive fatty acid pool (Table 2). The proportion of C26 did not significantly increase upon strong alkaline hydrolysis, indicating that the pools of ceramide-bound C26 in the nuclear membrane are not significantly greater than in the mild-base-sensitive fraction. This is consistent with a low abundance of ceramide and sphingolipids in the ER/nuclear membrane.

To determine whether this mild-base-sensitive pool of C26 is unique to the nuclear fraction, we compared the fatty acid profiles of isolated plasma membrane lipids to that of the nuclear membrane after mild or strong alkaline hydrolysis. Plasma membranes were isolated and were typically enriched more than 100-fold for the plasma-membrane proton-pumping ATPase (Pma1p), as judged by Western blot analysis (results not shown) [27]. GLC analysis of fatty acids released after mild base treatment of plasma membrane lipids revealed the presence of a small mild-base-sensitive pool of C26, comprising 1.3% of the released fatty acids. While essentially no mild-base-resistant pool of C26 was detected in the nuclear fraction, the plasma membrane contained a significant fraction of mild-base-resistant C26. These results are consistent with the predominant plasma membrane localization of ceramide-containing sphingolipids and the presence of mild-base-sensitive C26-containing lipid in both the nuclear and the plasma membranes [35].

The mild-base-sensitive C26 is linked to the sn-1 position of PI

The observation that mild base treatment resulted in release of C26 suggested that the fatty acid could be bound to a glycerolipid. To identify the nature of this lipid, individual glycerolipid classes present in the lipid extract of nuclear membranes were separated by two-dimensional TLC and analysed for the presence of the mild-base-releasable C26 fatty acid. In this analysis, the mild-base-sensitive C26 fatty acid could exclusively be detected in the inositol-containing glycerophospholipid fraction. C26 was not detectable in the more abundant glycerophospholipids, phosphatidylcholine or phosphatidylethanolamine.

To determine the positional distribution of the C26 fatty acid in PI, phospholipids from the nuclear fraction were subjected to sn-2 specific cleavage by phospholipase A2. The released fatty acids were separated from the lyso-lipids by TLC, and the chain-length distribution of the released fatty acid and the one that remained bound to the lyso-lipid was determined by GLC. This analysis revealed that the C26 fatty acid was not released by phospholipase A2 digestion and remained in the lyso-lipid fraction, indicating that C26 is bound to the sn-1 position of PI (Table 3). Control experiments with phospholipase A2 digestion of a synthetic sn-2 C26-substituted PC were performed to ascertain that the lipase can cleave C26 if present in the sn-2 position and hence that the observed sn-1 specificity is not due to a chain-length preference of the enzyme (results not shown).

Table 3. Fatty acid distribution in individual phospholipid classes in yeast nuclear membrane.

Relative proportion of the major phospholipid classes PC (phosphatidylcholine), PE (phosphatidylethanolamine), and PI in the nuclear membrane fraction and the positional distribution of fatty acids in sn-1 and sn-2 positions of these phospholipid classes (in mol %). The relative abundance of fatty acids is given as percentage of total. Values represent means±S.D. of three independent determinations. nd, not detected.

| PC (42%) | PE (32%) | PI (22%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Position | Position | |||||||

| Fatty acid | Total (%) | sn-1 | sn-2 | Total (%) | sn-1 | sn-2 | Total (%) | sn-1 | sn-2 |

| C16:0 | 23.2±2.3 | 88 | 35.8±4.7 | 90 | 38.3±4.3 | 76 | |||

| C16:1 | 45.6±6.4 | 50 | 50 | 27.5±3.9 | 56 | 17.1±2.8 | 86 | ||

| C18:0 | 5.4±0.9 | 79 | 4.6±0.8 | 54 | 14.8±2.5 | 69 | |||

| C18:1 | 25.5±2.9 | 94 | 31.4±4.1 | 83 | 28.0±3.4 | 89 | |||

| C26 | nd | nd | 1.4±0.3 | 92 | |||||

To determine whether the mild-base-sensitive pool of C26 identified in the plasma membrane is bound to the same lipid as the one in the nuclear membrane, the analysis was repeated with lipids isolated from the plasma membrane. As observed for the nuclear membrane, the mild-base-sensitive pool of C26 in the plasma membrane is also esterified to PI (Table 4).

Table 4. Fatty acid distribution in individual phospholipid classes in the yeast plasma membrane.

Relative proportion of the major phospholipid classes PC (phosphatidylcholine), PE (phosphatidylethanolamine), PI and PS (phosphatidylserine) in isolated yeast plasma membrane fractions. Relative abundance of fatty acids are given as mol % of the total. Values represent means±S.D. for three independent determinations. nd, not detected.

| Fatty acid | PC (17%) | PE (20%) | PI (18%) | PS (33%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C16:0 | 53.8±4.3 | 67.6±6.1 | 58.3±4.9 | 62.0±2.9 |

| C16:1 | 18.6±1.1 | 8.1±1.3 | 4.5±0.7 | 5.5±0.7 |

| C18:0 | 9.0±0.8 | 4.7±0.8 | 26.1±1.3 | 3.6±0.4 |

| C18:1 | 18.1±2.2 | 19.2±2.1 | 9.7±1.3 | 28.2±2.1 |

| C26:0 | nd | nd | 1.1±0.3 | nd |

The product of the ER-bound elongation reaction is likely to be C26-CoA; the synthesis of the C26-PI is thus predicted to require an acyltransferase that is highly specific for the transfer of C26 to the sn-1 position of PI. Interestingly, VLCFAs of higher plants are only found in phosphatidylserine [36], whereas in mammals, they are predominately found esterified in the sn-1 position of phosphatidylcholine [37]. Yeast contains two glycerol-3-phosphate/dihydroxyacetone phosphate acyltransferases, SCT1 and GPT2, which together account for the major sn-1-specific acyltransferase activity [38]. Deletion of either one or the other leaves the synthesis of the C26-PI intact (A. Conzelmann, personal communication).

MS analysis of C26-substituted lipid molecular species

At this stage of the analysis of the mild-base-sensitive pool of C26, it was still possible that the C26-substituted lipid was not a genuine PI, but another lipid that co-migrates with PI in our two-dimensional TLC experiment. We thus decided to analyse the distribution of C26 by nano-ESI-MS/MS, which allows the rapid and very sensitive qualitative and quantitative analysis of complex membrane lipid mixtures [39]. Precursor ion scan analysis for the presence of an ion fragment of a mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of 395, corresponding to the C26 fatty acid, revealed five peaks with m/z ratios of 975, 947, 921, 893 and 865. These correspond to PI lipids with a sum of carbon atoms and double bonds of 44:1, 42:1, 40:0, 38:0 and 36:0 (Figure 2). Product ion analysis of these three PI species revealed that PI of m/z 975 is composed of C26:0 and C18:1. The PI of m/z 947 is composed of two molecular species, one with C26:0 and C16:1, and the other with C24:0 and C18:1. This second species is less abundant and accounts for approx. 20–30% of the PI 42:1. The PI of m/z 921 is again composed of two molecular species: the major one containing C26:0 and C14:0 (approx. 50–90%), and a minor one containing C24:0 and C16:0. The fourth peak at m/z 893 (PI 38:0) is composed of approximately equal quantities of a species with C26:0 and C12:0 and another species with C24:0 and C14:0. The fifth peak at m/z 865 (PI 36:0), finally, is composed of three species, with a fatty acid composition of C18:0/C18:0, C26:0/C10:0 (≈20%), and C24:0/C12:0 (≈10%).

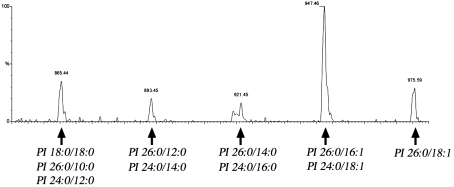

Figure 2. ESI MS/MS analysis of C26-containing molecular species of PI in the yeast nuclear membrane.

Precursor ion scan analysis for the C26 fatty acid (m/z 395) of total lipids extracted from the nuclear fraction. Peak assignment to molecular species of PI is indicated.

This MS analysis is thus consistent with the notion that yeast membranes contain PI as the sole C26-containing glycerophospholipid. MS analysis of lipids from the plasma membrane revealed the presence of the same five VLCFA-containing PI species that were also observed in the nuclear fraction (results not shown). In good agreement with the abundance of this lipid estimated by GLC analysis, the C26-PIs comprise approx. 1% of all the inositol-containing lipids, as determined by MS.

The specificity of the C26 substitution for the sn-1 position is interesting, and must be discussed in the context of the unusual sn-2 C26-PIs that are synthesized in the SLC1-1 yeast mutant. This strain bypasses a ceramide requirement by synthesizing novel sn-2 C26-PIs that structurally and functionally mimic sphingolipids, at least under standard growth conditions [18,19]. The fact that the sn-2 C26-PI in the SLC1-1 mutant is glycosylated to mannosyl-PIs and inositol-phosphate-mannosyl-PIs, whereas the sn-1 C26-PI that we identified in this study appears not to be glycosylated, as indicated by the lack of detectable amounts of mannosylated C26-PI species (at m/z 947+162 for mannose; results not shown), suggests that sorting/glycosylation and/or lipid remodelling is sensitive to the position of the C26 fatty acid.

The existence of a remodelling system that operates on inositol-containing lipids in yeast is indicated by the observation that GPI anchors containing LCFA-PI are remodelled in the ER to either ceramide or an sn-2 C26-PI [20]. These VLCFA-containing anchors are then remodelled further, resulting in the introduction and exchange of defined ceramides [20].

Synthesis of C26-PI

Having identified a novel C26-containing lipid in the nuclear membrane of yeast that might be important for maintaining a functional and morphological intact nuclear envelope, we wondered whether this lipid has any distinct biophysical properties that could not be provided by the abundant LCFA-substituted glycerophospholipid. Thus, to characterize the biophysical properties of the sn-1 C26-PI, synthetic C26-PI was prepared by a convergent synthesis (Scheme 2). First, the required sn-1-O-hexacosanoyl-sn-2-O-palmitoylglyceryl phosphoramidite was prepared from chiral solketal in six steps (not shown): (i) protection of the sn-3 hydroxy group as the PMB ether; (ii) hydrolysis of the acetal; (iii, iv) sequential introduction of the sn-1 hexacosanoyl and sn-2 palmitoyl groups; (v) oxidative deprotection of the 3-hydroxy group; and finally (vi) coupling with benzyloxychlorodi-isopropylphosphine. Coupling of the resulting diacylglycerylphosphoramidite to 1-hydroxy-2,3,4,5,6-pentakisbenzyloxy-D-myo-inositol followed by oxidation gave the protected C26-PI in a 68% yield after purification on silica gel. Catalytic hydrogenolysis removed the benzyl ethers and benzyl esters to give the homogeneous product, C26-PI, as a white solid in an 84% yield.

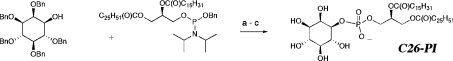

Scheme 2. Synthesis of C26-PI.

Steps (a–c) represent: (a) 5 equiv. tetrazole, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (b) m-chloroperbenzoic acid, −40 °C to 20 °C; (c) H2, 10% Pd/C, THF-H2O, 20 °C.

Biophysical characterization of C26-PI

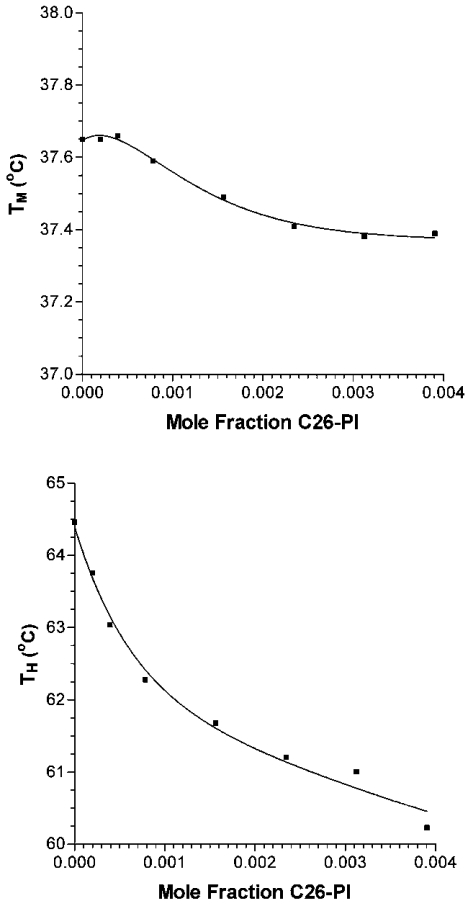

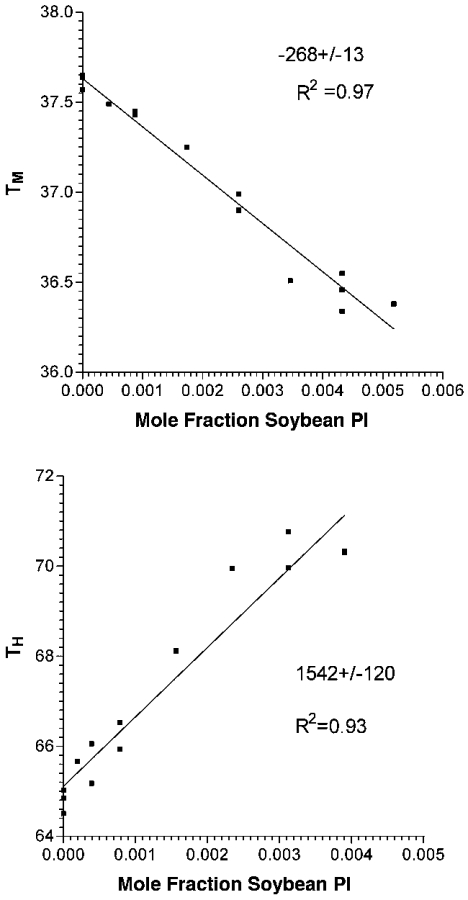

The effects of the C26-PI on membrane curvature were then assessed by examining the TH (bilayer to hexagonal transition temperature) of liposomes composed of DEPE. When added to DEPE liposomes at low mole fraction (0.1%), the C26-PI was among the most potent agents to lower TH (Figure 3). Over the linear portion of the first three points, the addition of C26-PI lowers TH by 3.03±0.03 °C per mole fraction additive. Compared with diacylglycerols or alkanes, the effect of the C26-PI on TH is approximately three or more times greater [40]. On the other hand, the effect of C26-PI on the TM (Lα to Lβ phase transition temperature) is approx. 10-fold smaller (Figure 3). A lowering of TM is commonly found upon addition of amphiphiles to bilayers, and has been interpreted as the effects of a ‘contaminant’ on the pure DEPE [41]. However, substances that reduce the hydration of the membrane interface are found to raise TM even though they lower TH [42]. Thus the effect of C26-PI is a consequence of its effect on hydrocarbon packing, rather than on the membrane interfacial properties. This is also likely to be the case since PI is an anionic lipid, and should inhibit hexagonal phase formation by preventing bilayer–bilayer contact. We can compare the action of C26-PI with other amphiphiles. In general, amphiphiles, even as long as 24 carbon atoms, raise TH [41]. This includes phosphatidylcholine, studied up to acyl-chain lengths of 22 carbon atoms [41]. Thus C26-PI is unusual, perhaps because of the mismatch between the two acyl chains. In comparison, a natural mixture of PI from soya bean, not having a high content of VLCFAs (33.2% C16:0, 46.8% C18:2), raises TH, as does lyso-PI from bovine liver (Figure 4, and results not shown). The effect of lyso-PI is smaller, possibly because it does not completely partition into the membrane (results not shown).

Figure 3. Dependence of TM and TH on the mole fraction of C26-PI added to DEPE liposomes.

Figure 4. Dependence of TM and TH of DEPE on the mole fraction of soya bean PI added to DEPE liposomes.

The upper-placed numbers in each panel indicate the slopes, and the lower-placed numbers show the regression coefficients (R2) of the linear plots.

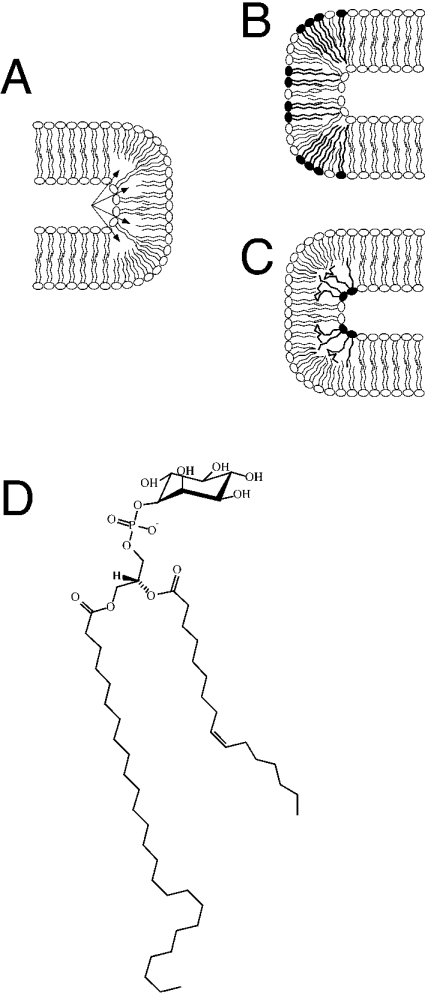

The biophysical properties of the C26-PI are thus consistent with a possible role of this lipid in stabilizing highly curved membrane structures, i.e. structures that are likely to be present in the nuclear envelope (Figure 5). The potent lowering of TH by C26-PI indicates that it can stabilize structures with negative curvature of a lipid monolayer, which might affect the morphology of a bilayer membrane if the C26-PI clusters at particular domains (Figure 5C). The NPC spans the nuclear envelope within a specialized pore membrane domain that is generally thought to be formed by a fusion of the inner and outer nuclear membrane, resulting in a tight 180° turn of the membrane. Based on electron microscopy, the membrane at this domain has been estimated to have a diameter of approx. 30 nm [43,44], which is considerably smaller than the ≈60 nm diameter typically observed in COP (coatamer protein) II coated vesicles [45].

Figure 5. Model of highly curved membrane domains and their possible stabilization by VLCFA-containing lipids: structure of the highly asymmetric C26-PI.

A schematic drawing of a 180° membrane bend with lipids containing LCFAs is shown in (A). A possible formation of a ‘void volume’ within the hydrophobic core of the membrane is indicated by arrows. VLCFA lipids (filled-in head groups) in either the outer (B) or the luminal (C) layer of the membrane could occupy this volume, and thereby stabilize the curved domain. (D) shows the structure of the highly asymmetric C26-PI that was identified in the present study.

Even though this C26-PI is present only in small amounts (approx. 1 mol% of all PIs), the local concentration of the lipid in a membrane domain may be higher and sufficient to exert the proposed stabilizing function on curved domains. The likelihood of C26-PI sequestering to specific domains in the membrane is made stronger by the finding that the shift of TM with increasing mole fraction of C26-PI is non-linear (Figure 3). This would be consistent with the lipid not distributing uniformly in the bilayer. This non-linearity is not seen with the mixed PI from soya bean (Figure 4).

The fact that this lipid is not restricted to the nuclear membrane does not preclude a possible role of this lipid in stabilizing curved membrane domains, as such domains are also found in the form of finger-like invaginations at the plasma membrane of yeast [46]. Direct experimental evidence for a possible structural function of this lipid in vivo, however, must await the availability of mutants that more specifically affect the synthesis of this lipid.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Aris, G. Daum, R. Fuller, P. Orlean, H. Riezman, R. Schekman, R. Serrano, and D. Wolf for kindly giving antisera or yeast strains used in this study, and A. Conzelmann for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB352, C6 and Z3; and grant Wi654/7-1 to B.B. and F.T.W.), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MT7654 to R.M.E.), the National Institutes of Health (NS29632 to G.D.P.), by support of the University of Utah for the Chemical Synthesis Facility (G.D.P.), the Austrian Science Fond (P13767 to R.S.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (631-065925 to R.S.).

References

- 1.Singer S. J., Nicolson G. L. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science. 1972;175:720–731. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meer G. Lipid traffic in animal cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1989;5:247–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgart T., Hess S. T., Webb W. W. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature (London) 2003;425:821–824. doi: 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munro S. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell. 2003;115:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouritsen O. G., Bloom M. Mattress model of lipid–protein interactions in membranes. Biophys. J. 1984;46:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdanov M., Heacock P. N., Dowhan W. A polytopic membrane protein displays a reversible topology dependent on membrane lipid composition. EMBO J. 2002;21:2107–2116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wente S. R. Gatekeepers of the nucleus. Science. 2000;288:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marelli M., Lusk C. P., Chan H., Aitchison J. D., Wozniak R. W. A link between the synthesis of nucleoporins and the biogenesis of the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:709–724. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worman H. J., Courvalin J. C. The inner nuclear membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;177:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002320001096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneiter R., Hitomi M., Ivessa A. S., Fasch E. V., Kohlwein S. D., Tartakoff A. M. A yeast acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase mutant links very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis to the structure and function of the nuclear membrane-pore complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:7161–7172. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneiter R., Kohlwein S. D. Organelle structure, function, and inheritance in yeast: a role for fatty acid synthesis? Cell. 1997;88:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Feel W., DeMar J. C., Wakil S. J. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant strain defective in acetyl-CoA carboxylase arrests at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:3095–3100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538069100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aitchison J. D., Blobel G., Rout M. P. Nup120p: a yeast nucleoporin required for NPC distribution and mRNA transport. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:1659–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein A. L., Snay C. A., Heath C. V., Cole C. N. Pleiotropic nuclear defects associated with a conditional allele of the novel nucleoporin Rat9p/Nup85p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:917–934. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siniossoglou S., Wimmer C., Rieger M., Doye V., Tekotte H., Weise C., Emig S., Segref A., Hurt E. C. A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell. 1996;84:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasslacher M., Ivessa A. S., Paltauf F., Kohlwein S. D. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase from yeast is an essential enzyme and is regulated by factors that control phospholipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:10946–10952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohlwein S. D., Eder S., Oh C. S., Martin C. E., Gable K., Bacikova D., Dunn T. Tsc13p is required for fatty acid elongation and localizes to a novel structure at the nuclear-vacuolar interface in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:109–125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.109-125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lester R. L., Dickson R. C. Sphingolipids with inositol phosphate-containing head groups. Adv. Lipid Res. 1993;26:253–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lester R. L., Wells G. B., Oxford G., Dickson R. C. Mutant strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking sphingolipids synthesize novel inositol glycerolipids that mimic sphingolipid structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:845–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sipos G., Reggiori F., Vionnet C., Conzelmann A. Alternative lipid remodelling pathways for glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1997;16:3494–3505. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zweytick D., Leitner E., Kohlwein S. D., Yu C., Rothblatt J., Daum G. Contribution of Are1p and Are2p to steryl ester synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:1075–1082. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leidich S. D., Drapp D. A., Orlean P. A conditionally lethal yeast mutant blocked at the first step in glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:10193–10196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandager L., Gustavsson M. H., Stahl U., Dahlqvist A., Wiberg E., Banas A., Lenman M., Ronne H., Stymne S. Storage lipid synthesis is non-essential in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6478–6482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sütterlin C., Doering T. L., Schimmöller F., Schröder S., Riezman H. Specific requirements for the ER to Golgi transport of GPI-anchored proteins in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:2703–2714. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leidich S. D., Kostova Z., Latek R. R., Costello L. C., Drapp D. A., Gray W., Fassler J. S., Orlen P. Temperature-sensitive yeast GPI anchoring mutants gpi2 and gpi3 are defective in the synthesis of N-acetylglucosaminyl phosphatidylinositol. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13029–13035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurt E. C., McDowall A., Schimmang T. Nucleolar and nuclear envelope proteins of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1988;46:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serrano R. H+-ATPase from plasma membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Avena sativa roots: purification and reconstitution. Methods Enzymol. 1988;157:533–544. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneiter R., Brügger B., Sandhoff R., Zellnig G., Leber A., Lampl M., Athenstaedt K., Hrastnik C., Eder S., Daum G., et al. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis of the lipid molecular species composition of yeast subcellular membranes reveals acyl chain-based sorting/remodeling of distinct molecular species en route to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:741–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J., Profit A. A., Prestwich G. D. Synthesis of photoactivatable 1,2-O-diacyl-sn-glycerol derivatives of 1-L-phosphatidyl-D-myo-inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdInsP2) and 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdInsP3) J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:6305–6312. doi: 10.1021/jo960895r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prestwich G. D. Touching the bases: inositol polyphosphate and phosphoinositide affinity probes from glucose. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J., Feng L., Prestwich G. D. Asymmetric total synthesis of diacyl- and head-group phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and 4-phosphate derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6511–6522. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billington D. C. Recent developments in the synthesis of myo-inositol phosphates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1989;18:83–122. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barz W. P., Walter P. Two endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane proteins that facilitate ER-to-Golgi transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:1043–1059. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaynor E. C., Mondesert G., Grimme S. J., Reed S. I., Orlean P., Emr S. D. MCD4 encodes a conserved endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein essential for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:627–648. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton J. L., Lester R. L. The phosphoinositol sphingolipids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are highly localized in the plasma membrane. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3101–3108. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3101-3108.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murata N., Sato N., Takahashi N. Very-long-chain fatty acids in phosphatidylserine from higher plant tissue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;795:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulos A. Very long chain fatty acids in higher animals – a review. Lipids. 1995;30:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02537036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Z., Zou J. The initial step of the glycerolipid pathway: identification of glycerol 3-phosphate/dihydroxyacetone phosphate dual substrate acyltransferases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41710–41716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brügger B., Erben G., Sandhoff R., Wieland F. T., Lehmann W. D. Quantitative analysis of biological membrane lipids at the low picomole level by nano-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2339–2344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epand R. M. Diacylglycerols, lysolecithin, or hydrocarbons markedly alter the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition temperature of phosphatidylethanolamines. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7092–7095. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epand R. M., Robinson K. S., Andrews M. E., Epand R. F. Dependence of the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition on amphiphile chain length. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9398–9402. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epand R. M., Bryszewska M. Modulation of the bilayer to hexagonal phase transition and solvation of phosphatidylethanolamines in aqueous salt solutions. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8776–8779. doi: 10.1021/bi00424a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fahrenkrog B., Hurt E. C., Aebi U., Pante N. Molecular architecture of the yeast nuclear pore complex: localization of Nsp1p subcomplexes. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:577–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Q., Rout M. P., Akey C. W. Three-dimensional architecture of the isolated yeast nuclear pore complex: functional and evolutionary implications. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barlowe C., Orci L., Yeung T., Hosobuchi M., Hamamoto S., Salama N., Rexach M. F., Ravazzola M., Amherdt M., Schekman R. COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1994;77:895–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulholland J., Preuss D., Moon A., Wong A., Drubin D., Botstein D. Ultrastructure of the yeast actin cytoskeleton and its association with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:381–391. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]