Abstract

Background

In nephrotic syndrome, protein leaks from the blood into the urine through the glomeruli, resulting in hypoproteinaemia and generalised oedema. While most children with nephrotic syndrome respond to corticosteroids, 80% experience a relapsing course. Corticosteroids have reduced the death rate to around 3%; however, corticosteroids have well‐recognised potentially serious adverse events such as obesity, poor growth, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, cataracts, glaucoma and behavioural disturbances. This is an update of a review first published in 2000 and updated in 2002, 2005, 2007, 2015 and 2020.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the benefits and harms of different corticosteroid regimens in children with steroid‐sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS). The benefits and harms of therapy were studied in two groups of children: 1) children in their initial episode of SSNS and 2) children who experience a relapsing course of SSNS.

Search methods

We contacted the Information Specialist and searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 9 July 2024 using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) performed in children (one to 18 years) during their initial or subsequent episode of SSNS, comparing different durations, total doses or other dose strategies using any corticosteroid agent.

Data collection and analysis

Summary estimates of effects were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Confidence in the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

In this 2024 update, we included five new studies, resulting in 54 studies randomising 4670 children.

Risk of bias methodology was often poorly performed, with only 31 studies and 28 studies respectively assessed to be at low risk for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Ten studies were at low risk of performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), and 12 studies were at low risk of detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment); nine of these studies were placebo‐controlled RCTs. Twenty‐seven studies (fewer than 50%) were at low risk for attrition bias, and 26 studies were at low risk for reporting bias (selective outcome reporting).

In studies at low risk of selection bias evaluating children in their initial episode of SSNS, there is little or no difference in the number of children with frequent relapses when comparing two months of prednisone with three months or more (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.10; 755 children, 5 studies; I2 = 0%; high certainty evidence) or when comparing three months with five to seven months of therapy (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.33; 376 children, 3 studies; I2 = 35%; high certainty evidence). In analyses of studies at low risk of selection bias, there is little or no difference in the number of children with any relapse by 12 to 24 months when comparing two months of prednisone with three months or more (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.06; 808 children; 6 studies; I2 = 47%) or when comparing three months with five to seven months of therapy (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.11; 377 children, 3 studies; I2 = 53%). Little or no difference was noted in adverse events between the different treatment durations.

Amongst children with relapsing SSNS, four small studies (177 children) utilising lower doses of prednisone compared with standard regimens found little or no differences between groups in the numbers with relapse (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.20; I2 = 0%). A fifth study (117 children) reported little or no difference between two weeks and four weeks of alternate‐day prednisone after remission with daily prednisone.

A recent large, well‐designed study with 271 children found that administering daily prednisone compared with alternate‐day prednisone or no prednisone during viral infection did not reduce the risk of relapse. In contrast, four previous small studies in children with frequently relapsing disease had reported that daily prednisone during viral infections compared with alternate‐day prednisone or no treatment reduced the risk of relapse.

Authors' conclusions

There are four well‐designed studies randomising 823 children, which have demonstrated that there is no benefit of prolonging prednisone therapy beyond two to three months in the first episode of SSNS. Small studies in children with relapsing disease have identified no differences in efficacy using lower induction doses or shorter durations of prednisone therapy. Large, well‐designed studies are required to confirm these findings. While previous small studies had suggested that changing from alternate‐day to daily prednisone therapy at the onset of infection reduced the likelihood of relapse, a much larger and well‐designed study found no reduction in the number relapsing when administering daily prednisone at the onset of infection.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant; Adrenal Cortex Hormones; Adrenal Cortex Hormones/therapeutic use; Bias; Dexamethasone; Dexamethasone/therapeutic use; Glucocorticoids; Glucocorticoids/therapeutic use; Nephrotic Syndrome; Nephrotic Syndrome/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Recurrence

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of using steroids for treating nephrotic syndrome in children?

Key messages

• Nephrotic syndrome (a condition where the kidneys leak protein from the blood into the urine) is usually treated with steroid medication (powerful anti‐inflammatory medicines).

• Children experiencing nephrotic syndrome for the first time only need two to three months of prednisone (a type of steroid medication), as longer durations do not reduce the risk of a repeat episode or reduce the risk that the child will have frequent repeat episodes.

• Although the risk of side effects may be low, many of the studies did not report information that we could analyse.

What is nephrotic syndrome, and why should you treat it with steroids?

Nephrotic syndrome is a condition where the kidneys leak protein from the blood into the urine. When left untreated, children can suffer from serious infections. In most children with nephrotic syndrome, this protein leak is stopped with steroid therapy. Steroids are powerful anti‐inflammatory medicines and can be used for a wide range of conditions, but they can also have serious side effects. These side effects can include depression and anxiety, high blood pressure, eye disorders such as cataracts, increased risk of infection, weight gain and reduced growth. Children can also have repeat episodes of nephrotic syndrome, which is often triggered by viral infection.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out the best treatment options for children with nephrotic syndrome to stop the leaking of protein from the blood into the urine and to avoid the harmful side effects of steroids.

What did we do?

We searched for all studies that compared the benefits and harms of randomly allocating steroid medicines to:

• children who experience nephrotic syndrome for the first time; or

• children who have frequent repeat episodes of nephrotic syndrome.

We compared and summarised the studies' results and rated our confidence in the information based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 54 studies randomising 4670 children looking at a wide variety of steroid treatment options. Studies were conducted in countries around the world, and most were done in South Asia (23 studies). Twenty‐three studies compared giving the steroid prednisone for two or three months with longer durations (three to seven months) to children who experience nephrotic syndrome for the first time. The remaining studies looked at children who had frequent repeat episodes of nephrotic syndrome.

We found longer durations of prednisone (three to seven months) made little to no difference in the risk of children experiencing repeat episodes of nephrotic syndrome or in the number of children who have frequent repeat episodes compared to shorter durations of prednisone (two to three months). There may be no differences in the type and number of side effects with either longer or shorter durations of steroids; however, these were often not reported by the studies.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We are confident that children experiencing nephrotic syndrome for the first time only need two to three months of prednisone, as longer durations do not reduce the risk of a repeat episode or reduce the risk that the child will have frequent repeat episodes.

We are less confident in the risk of side effects because many of the studies did not report information that we could use.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

The evidence is current to July 2024.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Steroid therapy for the first episode of nephrotic syndrome in children: 3 months or more versus 2 months of therapy.

| Steroid therapy for the first episode of nephrotic syndrome in children: 3 months or more versus 2 months of therapy | |||||

| Patient or population: children with nephrotic syndrome Setting: paediatric or paediatric nephrology services Intervention: 3 months or more of steroid therapy Comparison: 2 months of steroid therapy | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (RCTs) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Risk with 2 months of therapy | Risk with 3 months or more of therapy | ||||

| Frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months | 450 per 1,000 | 387 per 1,000 (319 to 477) | RR 0.86 (0.71 to 1.06) | 976 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝1 MODERATE |

| Relapsing by 12 to 24 months | 637 per 1,000 | 509 per 1,000 (433 to 611) | RR 0.80 (0.68 to 0.96) | 1279 (12) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1,2 LOW |

| Frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months: low risk of selection bias | 480 per 1,000 | 461 per 1,000 (339 to 528) | RR 0.96 (0.83 to 1.10) | 756 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months: unclear or high risk of selection bias | 333 per 1,000 | 150 per 1,000 (87 to 257) | RR 0.45 (0.26 to 0.77) | 220 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ 1,2 LOW |

| Adverse events: psychological disorders Median follow up: 2 years |

470 per 1,000 | 470 per 1,000 (249 to 894) | RR 1.00 (0.53 to 1.90) | 456 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝2,3 LOW |

| Adverse events: hypertension Median follow up: 1.5 years |

50 per 1,000 | 89 per 1,000 (28 to 287) | RR 1.78 (0.55 to 5.73) | 548 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ 1 MODERATE |

| Adverse events: Cushingoid facies Median follow up: 2 years |

402 per 1,000 | 450 per 1,000 (305 to 663) | RR 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) | 547 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝1 MODERATE |

| Adverse events: eye disorders Median follow up: 2 years |

32 per 1,000 | 13 per 1,000 (3 to 48) |

RR 0.41 (0.11 to 1.52) |

623 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝2,3 LOW |

| Adverse events: infections Median follow up: 1.75 years |

408 per 1,000 | 323 per 1,000 (216 to 478) |

RR 0.79 (0.53 to 1.17) |

172 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝2,3 LOW |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Significant heterogeneity between studies

2 Some studies at high or unclear risk of bias

3 Few studies/events included in analyses

Summary of findings 2. Steroid therapy for the first episode of nephrotic syndrome in children: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months of therapy.

| Steroid therapy for the first episode of nephrotic syndrome in children: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months of therapy | |||||

| Patient or population: nephrotic syndrome in children Setting: paediatric or paediatric nephrology services Intervention: 5 to 7 months of steroid therapy Comparison: 3 months of steroid therapy | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (RCTs) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with 3 months | Risk with 5 to 7 months | ||||

| Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months | 387 per 1,000 | 282 per 1,000 (190 to 422) | RR 0.73 (0.49 to 1.09) | 706 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 |

| Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months | 738 per 1,000 | 472 per 1,000 (369 to 598) | RR 0.64 (0.50 to 0.81) | 912 (8) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 2 |

| Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months: low risk of selection bias | 679 per 1,000 | 598 per 1,000 (469 to 754) | RR 0.88 (0.69 to 1.11) | 376 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Number of children relapsing by 12 to 24 months: unclear of high risk of selection bias | 778 per 1,000 | 412 per 1,000 (319 to 537) | RR 0.53 (0.41 to 0.69) | 536 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 2 |

| Adverse events: psychological disorders Median follow up: 2 years |

53 per 1,000 | 16 per 1,000 (3 to 96) |

RR 0.30 (0.05 to 1.83) |

505 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 |

| Adverse events: hypertension Median follow up: 1.75 years |

126 per 1,000 | 140 per 1,000 (90 to 220) | RR 1.11 (0.71 to 1.74) | 752 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 |

| Adverse events: Cushingoid appearance Median follow up: 1.75 years |

375 per 1,000 | 323 per 1,000 (225 to 461) |

RR 0.86 (0.60 to 1.23) |

762 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 |

| Adverse events: eye complications Median follow up: 1.5 years |

36 per 1,000 | 17 per 1,000 (6 to 42) | RR 0.46 (0.18 to 1.17) | 614 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 |

| Adverse events: infections Median follow up: 1.5 years |

185 per 1,000 | 181 per 1,000 (120 to 270) | RR 0.98 (0.65 to 1.46) | 702 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 2 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Significant heterogeneity between studies

2 Some studies at high or unclear risk of bias

Background

Description of the condition

Nephrotic syndrome is the most common acquired childhood kidney disease. Its characteristic features, including oedema, proteinuria, and hypoalbuminaemia, result from alterations in the selectivity of the permeability barrier of the glomerular capillary wall.

Based on a comprehensive meta‐analysis of 27 studies, the overall incidence of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome was 2.92 (95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.00 to 6.51) per 100,000 children per year (Veltkamp 2021), with no significant variation in incidence between 1945 and 2011. There are marked differences in the incidence of nephrotic syndrome depending on ethnicity, with proportions ranging from 1.15 to 16.9/100,000 children, with the highest incidence in children from South Asia (Noone 2018). Most children have minimal change disease, in which changes seen on light microscopy are minor or absent, and respond to corticosteroid agents. The histological variant seen and the response to immunosuppressive treatment varies with ethnicity. Steroid‐sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) is less common in African and African‐American children, and in South Africa, only 6.7% of 236 African children had SSNS compared with 65% of 286 Indian children (Bhimma 1997). The pathogenesis of SSNS remains unknown but appears to be related to abnormalities in T‐cell and B‐cell regulation, leading to injury of the podocyte, a key component of the glomerular filtration barrier.

Many children who respond to corticosteroids experience a relapsing course with recurrent episodes of oedema and proteinuria (Koskimies 1982; Tarshish 1997). While the incidence of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome has not changed, the risk of relapse between 1945 and 2011 has fallen from 87.4% to 66.2% based on the meta‐analysis of 54 studies (Veltkamp 2021). The complications of nephrotic syndrome are related to the effects of the disease itself and to adverse effects related to corticosteroid therapy and corticosteroid‐sparing agents. Children with nephrotic syndrome with frequent relapses, steroid dependence, or late resistance to therapy are at increased risk of bacterial infection (characteristically resulting in peritonitis, cellulitis, or septicaemia), thromboembolic phenomena and acute kidney injury. Before antibiotics became available, two‐thirds of children with nephrotic syndrome died. Death rates fell to 35% with the introduction of sulphonamides and penicillin (Arneil 1971) and fell further with the use of corticosteroid medications (Arneil 1956).

Description of the intervention

Corticosteroids have been used to treat childhood nephrotic syndrome since 1950 when large doses of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and cortisone given for two to three weeks were found to induce diuresis with loss of oedema and proteinuria (Arneil 1956; Arneil 1971). Corticosteroid usage has reduced the death rate in childhood nephrotic syndrome to around 3%, with infection remaining the most important cause of death (ISKDC 1984). Of children who present with their first episode of nephrotic syndrome, approximately 80% will achieve remission with corticosteroid therapy (Koskimies 1982). Because of this dramatic before‐after treatment evidence, oral corticosteroids are the first‐line treatment of a child presenting with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of corticosteroids compared to placebo were carried out. The achievement of remission with corticosteroid therapy determines long‐term prognosis for kidney function irrespective of kidney histology (Niaudet 2009). However, corticosteroids have well‐documented adverse effects in children. Major complications related to prolonged corticosteroid use in nephrotic syndrome include growth impairment, particularly with steroid therapy administered daily (Hyams 1988), cataracts (Aydin 2019; Ng 2001), arterial hypertension (Aydin 2019) and excessive weight gain or obesity (Ruth 2005). Two studies (Mishra 2010; Neuhaus 2010) highlight the impact of psychological and behavioural abnormalities related to corticosteroid therapy. Anxiety, depression, emotional lability, aggressive behaviour and attention problems had already developed with the completion of 12 weeks of therapy (Mishra 2010). Neuhaus 2010 demonstrated that family background, particularly maternal distress, reduced the quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial adjustment. Patients and families report challenges in living with the disease because the condition is poorly understood and the clinical course is uncertain (Beanlands 2017). Adverse effects are particularly prevalent in those children who relapse frequently and require multiple courses of corticosteroids.

How the intervention might work

Glucocorticoids are potent anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressant drugs. The effects of glucocorticoids are known to be mediated by both genomic and non‐genomic mechanisms (Schijvens 2019). It is widely believed the main effect is through the regulation of nuclear gene expression via the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor, which activates genes for anti‐inflammatory cytokines and suppresses genes for pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Kadmiel 2013; Kirshcke 2014; Ponticelli 2018). Glucocorticoids are lipid soluble and can easily pass through cell membranes. This process takes several hours. More recently, research has identified corticosteroid effects, which are independent of nuclear gene transcription and occur earlier (Ramamoorthy 2016). These are mediated via interactions of various kinases with cytosolic or membrane‐bound glucocorticoid receptors and do not require protein synthesis. At high glucocorticoid doses, suppression of T‐cell function occurs. Corticosteroids also act directly to stabilise the podocyte cytoskeleton (Guess 2010; Ohashi 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

The original treatment schedules for childhood nephrotic syndrome were developed in an ad hoc manner more than 50 years ago. The International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) was established in 1966 and determined by consensus a regimen of daily corticosteroids for four weeks followed by corticosteroids given on three consecutive days out of seven for four weeks (Arneil 1971). Since then, many physicians have used regimens involving periods of daily followed by alternate‐day or intermittent therapy, and RCTs have investigated different durations and total corticosteroid therapy doses in an effort to delineate the optimal doses and durations of corticosteroid therapy, balancing efficacy and toxicity. These have been evaluated in previous versions of this systematic review. However, despite these data, there remains no consensus on the most appropriate corticosteroid regimen to achieve and maintain remission with the least adverse effects. Observational data (Raja 2017) and small RCTs (Borovitz 2020; Kansal 2019; Kainth 2021; Sheikh 2019; Tu 2022) suggest that children can be successfully treated with smaller doses and durations of corticosteroid therapy. Therefore, this 2024 update was undertaken to identify whether new RCTs, which evaluate different corticosteroid regimens in the initial episode of SSNS and in relapsing disease, provide additional information on the most effective corticosteroid therapy regimens for SSNS in children.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the benefits and harms of different corticosteroid regimens in children with SSNS. The benefits and harms of therapy were studied in two groups of children:

Children in their initial episode of SSNS

Children who experience a relapsing course of SSNS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) were included in which different doses, dose strategies, routes of administration and durations of treatment with prednisone, prednisolone or other corticosteroid agents are compared in the treatment of SSNS in children.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Children aged one to 18 years with SSNS (i.e. become oedema‐free with urine protein ≤ 1+ on dipstick, urinary protein‐creatinine ratio (UPCR) ≤ 20 mg/mmol or ≤ 4 mg/m2/hour for three consecutive days while receiving corticosteroid therapy). A kidney biopsy diagnosis of minimal change disease was not required for inclusion in the study.

Children with an initial episode of SSNS

Children with relapsing SSNS.

Exclusion criteria

Children with steroid‐resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) (failure to achieve remission following four weeks or more of prednisone at 60 mg/m2/day) or congenital or infantile nephrotic syndrome

Children with other kidney or systemic forms of nephrotic syndrome defined on kidney biopsy, clinical features or serology (e.g. idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritis, mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, post‐infectious glomerulonephritis, IgA vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus).

Types of interventions

Prednisone, prednisolone, or other corticosteroid medication given orally or intravenously (IV) without additional non‐corticosteroid medications, including but not limited to alkylating agents, calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolic acid derivatives, levamisole, Chinese medications, montelukast and monoclonal Anti‐CD20 antibodies.

The following aspects of the corticosteroid regimens were considered.

Shorter durations compared with two months or more of corticosteroid treatment

Longer durations compared with two months or less of corticosteroid treatment

Comparisons of different doses of corticosteroid medication given for induction of a remission

Comparisons of other regimens of corticosteroid therapy

Different corticosteroid agents (e.g. deflazacort, methylprednisolone) compared with standard agents (e.g. prednisone, prednisolone)

Comparisons of daily, alternate‐day or intermittent administration of corticosteroid medication. Intermittent administration refers to the administration of corticosteroids on three consecutive days out of seven days

Single daily dose compared with divided daily doses of corticosteroid medication.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The numbers of children with and without relapse at six to 24 months or more after completion of treatment.

The number of children who developed frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome (FRNS) or steroid‐dependent nephrotic syndrome (SDNS).

Secondary outcomes

Mean relapse rates

Serious adverse events, including psychological disturbances, hypertension, Cushing's Syndrome, eye complications (e.g. cataracts, glaucoma), infections, reduced growth rates, thromboses and osteoporosis

Cumulative corticosteroid dosage.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 9 July 2024 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Monthly searches of the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Conference proceedings of meetings of the International Pediatric Nephrology Association and European Society for Paediatric Nephrology.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The initial review was undertaken by four authors. The titles and abstracts were screened by two authors who discarded studies that were not relevant (i.e. studies of lipid‐lowering agents), although studies and reviews that could have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Three authors independently assessed abstracts and, if necessary, the full text to determine which studies satisfied the characteristics required for inclusion. Updates in 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2015 were undertaken by three or four authors (DH, EH, NW, JC). The 2020 update was undertaken by three authors (DH, SS, EH), with a final review by two other authors (NW and JC). This 2024 update was undertaken by three authors (EH, DH, NW), with a final review by two authors (SS, JC).

Data extraction and management

Two authors used standardised data extraction forms to extract data and assess the risk of bias. Studies in languages other than English were translated before data extraction. Where more than one report of a study was identified, data were extracted from all reports. Where there were discrepancies between reports, data from the primary source was used. Study authors were contacted for additional information about studies where possible.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, the following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2022) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Was incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. relapse or no relapse, adverse events), the risk ratio (RR) for individual studies was calculated with 95% CI. Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. cumulative steroid therapy, relapse rate), these data were analysed as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. The time to relapse was not included since many children did not experience relapse, so the data would be biased.

Unit of analysis issues

Data from cross‐over studies were included in the meta‐analyses if separate data for the first part of the study were available. Otherwise, the results of cross‐over studies were reported in the text only.

Dealing with missing data

We aimed to analyse available data in meta‐analyses using intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data. However, where ITT data were not provided or additional information could not be obtained from authors, available published data were used in the analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). The following is a guide to the interpretation of I2 values.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi2 test or a 95% CI for I2) (Higgins 2022).

Assessment of reporting biases

The search strategy used aimed to reduce publication bias caused by lack of publication of studies with negative results. Where there were several publications of the same study, all reports were reviewed to ensure that all details of methods and results were included to reduce the risk of selective outcome reporting bias.

Data synthesis

Data were combined using the random‐effects model for dichotomous and continuous data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to investigate between‐study differences based on the risk of bias, differences between definitions of FRNS and different durations of treatment in the experimental group in studies of initial treatment with different durations of prednisone.

Sensitivity analysis

Where a single study differed considerably from the other studies in the meta‐analysis, it was temporarily excluded to determine whether its removal altered the meta‐analysis's results.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We have presented the main results of the review in summary of findings tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2022a). The summary of findings tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2022b). We presented the following outcomes in the summary of findings tables.

Number with relapse

Number with frequent relapse (total and stratified for risk of bias)

Adverse effects (psychological disturbances, hypertension, Cushing's Syndrome, eye complications, infections).

Results

Description of studies

The following section contains broad descriptions of the studies considered in this review. For further details on each individual study, see, Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

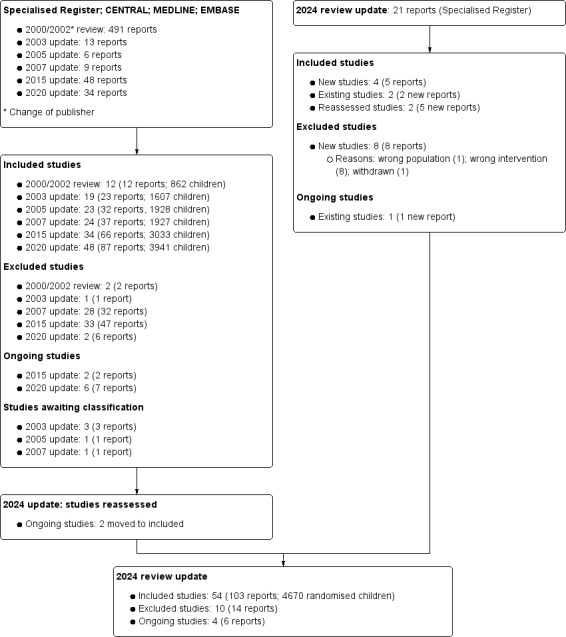

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies (up to 9 July 2024) and identified 21 new reports. Four new studies (five reports) were included, and eight studies (eight reports) were excluded. We also identified two new reports of two existing included studies and one report of an existing ongoing study. We reassessed and reclassified two ongoing studies (five new reports) as included studies (Kainth 2021; PREDNOS 2 2022).

A total of 54 studies were included (103 reports, 4670 randomised children), 10 studies were excluded, and there are four ongoing studies.

Search results are shown in Figure 1.

1.

Flow diagram for 2024 review update study selection

Included studies

The majority of the studies were performed in South Asia (23 studies), Europe (14 studies), Asia (9 studies), and other regions, including the Middle East, South America and the USA (8 studies).

The number of children randomised ranged from 11 to 271 (median number: 66).

The 54 included studies were divided into groups according to the comparisons of corticosteroid regimens. Most studies used prednisone or prednisolone. For ease of reading, the term "prednisone" has been used in the text for both medications.

Three months or more versus two months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Thirteen studies (1465 randomised children) compared durations of two months with three months or more of prednisone therapy (APN 1993; Bagga 1999; Jayantha 2000; Ksiazek 1995 (groups 1 and 3); Moundekhel 2012; Norero 1996; Paul 2014; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; Satomura 2001; Ueda 1988; Yoshikawa 1998; Yoshikawa 2015). Except for Satomura 2001, all these studies increased the duration of treatment, resulting in an increased total prednisone dose compared with the control group. Satomura 2001 compared three months of treatment with two months using the same total dose of prednisone in each group. In Ksiazek 1995, which compared three different regimens, data from the two‐month therapy group (group 3) and the group treated for six months (group 1) were included in the meta‐analysis. Norero 1996 excluded children who became steroid‐dependent. In this update, Yoshikawa 1998, which compared two months of prednisone with 4.5 months with both groups receiving the Chinese herb, Sairei‐to, was included in this analysis on the assumption that the effect of the herb would be the same in both treatment groups. Data from Paul 2014 could not be included in meta‐analyses because of differential loss to follow‐up, with loss to follow‐up of 15/47 children (33%) in the 12‐week treatment group compared with 6/46 children (13%) in the eight‐week treatment group.

Five to seven months versus three months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Ten studies (1142 randomised children) compared five to seven months with three months of prednisone therapy (Al Talhi 2018; Anand 2013; Hiraoka 2003; Jamshaid 2022; Ksiazek 1995 (groups 1 and 2); Mishra 2012; Pecoraro 2003; Sharma 2002; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013). Anand 2013 (60 children) did not report the number of children treated in each group, so data from only nine studies could be included in the meta‐analyses. Increased duration of prednisone treatment led to increased total prednisone dose compared with the three‐month group in all studies except Teeninga 2013, who compared three months with six months therapy, using the same total dose of prednisone in both groups. From Ksiazek 1995, data from the groups treated for three months (group 2) and six months (group 1) were included in this analysis. Pecoraro 2003 included three groups ‐ a control group treated for three months and two groups treated for six months with different total doses of prednisone. Only the control group and treatment group 1 (total prednisone dose 5235 mg/m2) were included in the meta‐analysis.

Daily prednisone treatment during viral infections in children with relapsing SSNS

Five studies (503 randomised children) evaluated the effect of daily prednisone for five to seven days at the onset of infection to prevent relapse (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; Gulati 2011; Mattoo 2000; PREDNOS 2 2022). Three studies (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Gulati 2011; Mattoo 2000) compared daily with alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse during viral infections in children with SSNS. Abeyagunawardena 2017 compared daily prednisone with a placebo to prevent relapse during viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) in children not receiving prednisone. PREDNOS 2 2022 included four groups of children with SSNS, as shown below.

Not on alternate‐day prednisone

Receiving alternate‐day prednisone

Receiving alternate‐day prednisone and other immunosuppressive agents

Receiving other immunosuppressive agents but not alternate‐day prednisone.

Deflazacort versus prednisone therapy in children with relapsing or an initial episode of SSNS

Four studies (118 randomised children) explored different deflazacort regimens versus prednisone.

Agarwal 2010 compared deflazacort with prednisone in children with the initial episode of SSNS, but the details of the intervention were not reported.

Broyer 1997 compared deflazacort with an equivalent dose of prednisone with reducing doses over 12 months in children with steroid‐dependent SSNS.

Liern 2008 compared deflazacort with methylprednisolone for 12 weeks in children with relapsing SSNS in a cross‐over study.

Singhal 2015 compared deflazacort with prednisone for 12 weeks in children with the initial episode of SSNS.

Oral methylprednisolone regimens in children with the initial episode of SSNS

Three studies (113 randomised children) compared different regimens of methylprednisolone with prednisone.

Imbasciati 1985 compared six months of treatment commencing with methylprednisolone and then prednisone with six months of prednisone.

Mocan 1999 compared 14 days of high‐dose methylprednisolone with six months of prednisone.

Zhang 2007d compared six months of treatment involving methylprednisolone with six months of prednisone. The details of interventions were not reported.

One versus two months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

APN 1988 (61 randomised children) compared less than two months of prednisone with two months.

Five versus 12 months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Kleinknecht 1982 (58 randomised children) compared five months of prednisone with 12 months; the timing of the follow‐up period in relation to the duration of initial therapy was not reported.

Different total doses of prednisone given for three months in the initial episode of SSNS

Hiraoka 2000 (68 randomised children) compared a higher dose of prednisone given for three months with a conventional dose.

Alternate‐day versus intermittent therapy in relapsing SSNS

APN 1981 (64 randomised children) compared an alternate‐day prednisone regimen with a three out of seven‐day regimen to maintain remission.

Daily versus intermittent therapy in relapsing SSNS

ISKDC 1979 (64 randomised children) compared a daily prednisone regimen with a three out of seven‐day regimen to maintain remission.

Intravenous then oral therapy versus oral therapy alone

Imbasciati 1985 (64 children) compared IV methylprednisolone for three days, then oral prednisone (daily for four weeks, then alternate‐day for four months) with oral prednisone alone.

Single versus multiple daily doses in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Ekka 1997, Khan 2023, Li 1994 and Weerasooriya 2023 (314 randomised children) compared a single daily dose of prednisone with two or three times/day dosing to achieve remission.

Low versus conventional dose prednisone in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Five studies (303 randomised children) compared low versus conventional dose prednisone in relapsing nephrotic syndrome.

Borovitz 2020 compared two reduced daily doses (1 mg/kg/day; 1.5 mg/kg/day) with conventional daily dose of prednisone (2 mg/kg/day) to achieve remission.

Sheikh 2019 compared a reduced daily dose (1 mg/kg/day) of prednisone with a conventional daily dose (2 mg/kg/day) to achieve remission.

Tu 2022 compared a reduced daily dose (30 mg/m2/day) of prednisone with a conventional daily dose of prednisone (60 mg/m2/day) to achieve remission.

Kansal 2019 compared different alternate‐day prednisone doses in the second month of initial treatment to maintain remission.

Kainth 2021 compared two weeks of alternate‐day prednisone (40 mg/m2) with four weeks after participants achieved remission with a conventional daily dose of prednisone (60 mg/m2/day).

Daily versus alternate‐day prednisone in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Yadav 2019 (62 randomised children) compared daily with alternate‐day prednisone for one year in children with frequently relapsing SSNS

Weight‐based versus body surface area‐based dosing of prednisone in the initial episode of SSNS

Two studies (160 randomised children) compared weight‐based dosing with body surface area (BSA)‐based dosing in children with their initial episode of SSNS and with a relapse of SSNS (Basu 2020; Raman 2016).

Alternate‐day prednisone for four weeks versus an eight‐week weaning regimen in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

PROPINE 2020 (78 randomised children) compared 18 doses of prednisone (40 mg/m2) given on alternate days over 36 days with a tapering dose (36 doses) over 72 days using the same cumulative prednisone dose in each group.

Three months or more versus two months of therapy in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Jayantha 2002b (129 randomised children) compared two months of prednisone with seven months in children with relapsing nephrotic syndrome.

Cortisol addition to prednisone regimen versus no cortisol addition in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Leisti 1978 (13 randomised children) compared the addition of cortisol supplementation with no cortisol in children with relapsing nephrotic syndrome and a subnormal response to a 2‐hour ACTH test one to 12 days after completing prednisone.

Excluded studies

In this update, eight (eight reports) new studies were excluded. One study (Xu 2020b) was abandoned due to a lack of funding. Five studies investigated prednisone therapy together with Chinese medications (Hou 2021; Wu 2022; Yang 2022a), montelukast (Javidi 2021) or vitamin D (Zhou 2021). Two studies (Zhang 2021b; Zhu 2021a) used intensive regimens in difficult‐to‐manage children, including children with SRNS.

In total, 10 studies were excluded (APN 2006; Hou 2021; Javidi 2021; Wu 2022; Xu 2020b; Yang 2022a; Zhang 2014; Zhang 2021b; Zhou 2021; Zhu 2021a).

Ongoing studies

There are four ongoing studies.

CTRI/2018/05/013634 will compare alternate‐day prednisone (1 mg/kg versus 1.5 mg/kg) for relapse in children with nephrotic syndrome.

CTRI/2018/05/014075 will compare 1 mg/kg/day versus 2 mg/kg/day till remission in children with SSNS presenting with relapse.

RESTERN 2017 will compare daily prednisone till remission, then alternate days for two weeks versus six weeks in children with SSNS presenting with relapse.

Sinha 2016 will compare tapering prednisone over 12 weeks versus stop therapy in children initially treated with standard therapy for 12 weeks.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessments were performed using Cochrane's risk of bias assessment tool (Appendix 2). Figure 2 summarises the overall risks of bias in the studies, and Figure 3 reports the risks of bias in each individual study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randon sequence generation

Random sequence generation was considered at low risk of bias in 31 studies (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; Agarwal 2010; APN 1993; Bagga 1999; Basu 2020; Broyer 1997; Gulati 2011; Hiraoka 2003; Imbasciati 1985; Jayantha 2000; Jayantha 2002b; Kainth 2021; Khan 2023; Kleinknecht 1982; Liern 2008; Mishra 2012; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; PROPINE 2020; Raman 2016; Sharma 2002; Sheikh 2019; Singhal 2015; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013; Weerasooriya 2023; Yadav 2019; Yoshikawa 1998; Yoshikawa 2015) and high risk in seven studies (Borovitz 2020; Li 1994; Mattoo 2000; Mocan 1999; Moundekhel 2012; Pecoraro 2003; Satomura 2001). Sequence generation methods were assessed as unclear in the remaining 16 studies.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was considered to be at low risk of bias in 28 studies (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; Al Talhi 2018; APN 1981; APN 1988; APN 1993; Bagga 1999; Basu 2020; Broyer 1997; Gulati 2011; Hiraoka 2003; Imbasciati 1985; Kainth 2021; Khan 2023; Kleinknecht 1982; Liern 2008; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; PROPINE 2020; Raman 2016; Sheikh 2019; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013; Weerasooriya 2023; Yadav 2019; Yoshikawa 1998; Yoshikawa 2015) and at high risk of bias in nine studies (Borovitz 2020; Ksiazek 1995; Li 1994; Mattoo 2000; Mocan 1999; Moundekhel 2012; Norero 1996; Pecoraro 2003; Satomura 2001). Ksiazek 1995 stated that parents could influence which treatment group their child was assigned. Allocation concealment methods were assessed as unclear in the remaining 17 studies.

Blinding

Ten studies were considered to be at low risk of performance bias because they were placebo‐controlled studies (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; Broyer 1997; Leisti 1978; Liern 2008; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013). These ten studies, together with Basu 2020 and Yoshikawa 2015 were at low risk of detection bias. Basu 2020 and Yoshikawa 2015 were open‐label studies, so they were at high risk of performance bias but were at low risk of detection bias. For Kansal 2019, the risk for both performance and detection bias was unclear. The remaining studies were at high risk of both performance and detection bias. Most studies reported the primary outcome of relapse using the ISKDC definition of relapse (ISKDC 1970).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed 27 studies to be at low risk of attrition bias because they reported fewer than 10% of participants lost to follow‐up or excluded from analysis (Al Talhi 2018; APN 1993; Bagga 1999; Basu 2020; Borovitz 2020; Broyer 1997; Hiraoka 2000; Hiraoka 2003; Imbasciati 1985; Kainth 2021; Khan 2023; Ksiazek 1995; Leisti 1978; Mattoo 2000; Mishra 2012; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PROPINE 2020; Raman 2016; Sheikh 2019; Singhal 2015; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013; Tu 2022; Yadav 2019; Yoshikawa 2015). Fourteen studies were considered at high risk of attrition bias because 10% or more of participants were lost to follow‐up or excluded from the analysis (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; APN 1981; APN 1988; Ekka 1997; Gulati 2011; ISKDC 1979; Jayantha 2000; Jayantha 2002b; Mocan 1999; Norero 1996; Paul 2014; Sharma 2002; Yoshikawa 1998). The remaining 13 studies were considered to be unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Studies were deemed to be at risk of reporting bias if outcome data did not include one or more outcomes of FRNS, relapse rate and adverse events. Studies were also considered to be at high risk of bias if data were provided in a format which could not be entered into the meta‐analyses. Cross‐over studies were considered to be at high risk of bias if data from the first and second parts of the study were not separable. Twenty‐six studies were at low risk of reporting bias (Al Talhi 2018; APN 1981; APN 1993; Bagga 1999; Basu 2020; Broyer 1997; Ekka 1997; Gulati 2011; Hiraoka 2000; Hiraoka 2003; Imbasciati 1985; Jayantha 2000; Kainth 2021; Norero 1996; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PROPINE 2020; Sharma 2002; Singhal 2015; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013; Tu 2022; Yadav 2019; Yoshikawa 2015; Ueda 1988). There were 22 studies at high risk of selective reporting bias (Abeyagunawardena 2008; Abeyagunawardena 2017; APN 1988; Borovitz 2020; ISKDC 1979; Jamshaid 2022; Jayantha 2002b; Khan 2023; Kleinknecht 1982; Ksiazek 1995; Leisti 1978; Li 1994; Liern 2008; Mattoo 2000; Mocan 1999; Moundekhel 2012; Paul 2014; Pecoraro 2003; Raman 2016; Sheikh 2019; Weerasooriya 2023; Yoshikawa 1998). The remaining six studies were at unclear risk of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Nineteen studies were considered at low risk of potential bias as they were funded by educational or philanthropic organisations or stated that they received no funding (Abeyagunawardena 2008; APN 1981; APN 1988; Bagga 1999; Basu 2020; Gulati 2011; Kainth 2021; Khan 2023; Leisti 1978; Norero 1996; PREDNOS 2019; PREDNOS 2 2022; PREDNOS PILOT 2019; PROPINE 2020; Sinha 2015; Teeninga 2013; Ueda 1988; Yadav 2019; Yoshikawa 2015). One study was considered to be at high risk of bias as it was funded by industry, and no full‐text publication was identified 10 years after the first conference abstract (Pecoraro 2003). The remaining 34 studies were deemed unclear of other risks of bias as no information on funding sources was provided.

In Ueda 1988, the calculated total protocol dose (4620 mg/m2) exceeded the dose administered (3132 ± 417 mg/m2), suggesting that the protocol was not adhered to in all patients. In three studies (Jayantha 2000; Ksiazek 1995; Ueda 1988), the numbers of children in the treatment and control groups differed markedly.

Effects of interventions

Three months or more versus two months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Therapy for three months or more probably makes little or no difference to the number of children with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months compared to two months of therapy (Analysis 1.1: RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.06; 976 children, 8 studies; I2 = 33%; moderate certainty evidence).

-

Therapy for three months or more may reduce the number of children relapsing by 12 to 24 months (Analysis 1.2: RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.96; 1279 children, 12 studies; I2 = 70%; low certainty evidence).

In subgroup analysis of studies at low risk of selection bias, there is little or no difference in the number with frequent relapses between the two groups (Analysis 1.3.1: RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.10; 755 children; 5 studies; I2 = 0%) or the number of children relapsing by 12 to 24 months (Analysis 1.4.1: RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.06; 808 children; 6 studies; I2 = 36%) (high certainty evidence) (Figure 4).

In contrast, in subgroup analysis of studies at unclear or high risk of selection bias, longer duration of prednisone therapy probably reduces the number of children with frequent relapses (Analysis 1.3.2: RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77; 220 children, 3 studies; I2 = 0%) (moderate certainty evidence) and the number of children relapsing by 12 to 24 months (Analysis 1.4.2: RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.98; 471 children, 6 studies; I2 = 72%).

Similar differences in results were shown when data were stratified according to risk of bias for detection and performance bias or for attrition bias (data not shown).

There may be little or no difference in adverse events between the two groups (Analysis 1.5) (low or moderate certainty evidence). In Yoshikawa 2015, results were reported as events, not patients, so they could not be included in the meta‐analyses. The authors reported that the frequency and severity of adverse events were similar in both groups.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months, Outcome 1: Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months, Outcome 2: Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months, Outcome 3: Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months: stratified by risk of selection bias

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months, Outcome 4: Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months: stratified by risk of selection bias

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months therapy, outcome: 1.3 Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months stratified by risk of bias for selection bias.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Steroid therapy in first episode: ≥ 3 months versus 2 months, Outcome 5: Adverse events

Results were downgraded for medium to high levels of heterogeneity between studies and for risk of bias issues (Table 1). The heterogeneity between studies was explained by the risk of bias issues (Analysis 1.3.1; Analysis 1.3.2; Analysis 1.4.1; Analysis 1.4.2) but not by the inclusion or exclusion of patients with steroid‐dependent disease, different durations of prednisone (two months versus three months or more) or different definitions of FRNS (ISKDC definition compared with other definitions) (data not shown).

Five to seven months versus three months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Five to seven months of therapy probably makes little or no difference to the number of children with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months compared to three months of therapy (Analysis 2.1: RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.09; 707 children, 6 studies; I2 = 68%; moderate certainty evidence).

-

Five to seven months of therapy may reduce the number of children relapsing by 12 to 24 months compared to three months of therapy (Analysis 2.2: (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.81; 912 children; 8 studies; I2 = 80%; low certainty evidence).

In subgroup analysis of studies at low risk of selection bias, there is little or no difference in the number with frequent relapses (Analysis 2.3.1: RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.33; 376 children, 3 studies; I2 = 35%; high certainty evidence) or in the number relapsing by 12 to 24 months (Analysis 2.4.1: RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.11; 376 children, 3 studies; I2 = 53%) (Figure 5).

In contrast, in subgroups of studies at high or unclear risk of selection bias, five to seven months of therapy probably reduces the risk of FRNS (Analysis 2.3.2: RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.72; 330 children, 3 studies; I2 = 0% moderate certainty evidence) and the number relapsing by 12 to 24 months (Analysis 2.4.2: RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.69; 536 children; 5 studies; I2 = 60%).

Similar differences in results were shown when data were stratified according to risk of bias for detection and performance bias or for attrition bias (data not shown).

There may be little or no difference in adverse events, including psychological disorders, growth retardation, hypertension, cataracts/glaucoma, osteoporosis, infections or Cushingoid features (Analysis 2.5; low or moderate certainty evidence).

Anand 2013 reported that the number relapsing at 12 months was lower with six months of prednisone compared with three months. Data could not be included in the meta‐analysis as the numbers in each group were not provided.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, Outcome 1: Number with frequent relapses by 12 to 24 months

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, Outcome 2: Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, Outcome 3: Number with frequent relapses: stratified by risk of selection bias

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, Outcome 4: Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months: stratified by risk of selection bias

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, outcome: 2.3 Number with frequent relapses stratified by risk of selection bias.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Steroid therapy in first episode: 5 to 7 months versus 3 months, Outcome 5: Adverse events

Results were downgraded for medium to high levels of heterogeneity between studies and for risk of bias issues (Table 2). The heterogeneity between studies was explained by the risk of bias issues (Analysis 2.3.1; Analysis 2.3.2; Analysis 2.4.1; Analysis 2.4.2) but not by inclusion or exclusion of patients with steroid‐dependent disease, different durations of prednisone (three months versus five to seven months), or different definitions of FRNS (ISKDC definition compared with other definitions) (Data not shown).

One versus two months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

APN 1988 reported two months of therapy compared to one month may reduce the risk of relapse at six to 12 months (Analysis 3.1: RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.54; 61 children) and 12 to 24 months (Analysis 3.2: RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.12; 60 children).

APN 1988 reported two months of therapy compared to one month had uncertain effects on the number of children with frequent relapses (Analysis 3.3: RR 1.48, 95%CI 0.85 to 2.59; 61 children).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Steroid therapy in the first episode: 1 month versus 2 months, Outcome 1: Number relapsing by 6 to 12 months

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Steroid therapy in the first episode: 1 month versus 2 months, Outcome 2: Number relapsing by 12 to 24 months

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Steroid therapy in the first episode: 1 month versus 2 months, Outcome 3: Number with frequent relapses

Twelve versus five months of therapy in the initial episode of SSNS

Ksiazek 1995 reported that 12 months of therapy compared to five months had uncertain effects on the number of children relapsing (Analysis 4.1: RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.13; 58 children).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Steroid therapy in the first episode: 12 months versus 5 months, Outcome 1: Number with relapse

Different total doses of prednisone given for three months in the initial episode of SSNS

Hiraoka 2000 reported a higher dose may reduce the number of children relapsing by 12 months (Analysis 5.1: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.98; 60 children) but may make little or no difference to the number with frequent relapses (Analysis 5.2: RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.37; 60 children).

Hiraoka 2000 reported psychological disorders, hypertension, and Cushing's Syndrome may not differ between the groups (Analysis 5.3).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Steroid therapy in the first episode: different total doses given over the same duration, Outcome 1: Relapse at 12 months

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Steroid therapy in the first episode: different total doses given over the same duration, Outcome 2: Number with FRNS

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Steroid therapy in the first episode: different total doses given over the same duration, Outcome 3: Adverse events

Oral methylprednisolone in children with relapsing or initial episodes of SSNS

Methylprednisolone, compared with prednisolone, may reduce the time to remission (Analysis 6.1: MD ‐5.54 days, 95% CI ‐8.46 to ‐2.61; 38 children, 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

Imbasciati 1985 reported methylprednisolone, compared with prednisolone, may make little or no difference to the number of children who relapse (Analysis 6.2: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.52; 62 children).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Steroid therapy in first episode: methylprednisone versus prednisolone, Outcome 1: Time to remission [days]

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Steroid therapy in first episode: methylprednisone versus prednisolone, Outcome 2: Number with relapse

Daily prednisone treatment during viral infections in children with relapsing or initial episodes of SSNS

Daily prednisone at the onset of URTI compared with placebo probably makes little or no difference to the risk of relapse (Analysis 7.1.1: RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.49; 310 children; 2 studies; I2 = 45%) (moderate certainty evidence).

-

Subgroup analyses

PREDNOS 2 2022 reported that in those not initially receiving any prednisone, administering daily prednisone at the onset of URTI may make little or no difference to the risk of relapse (Analysis 7.1.2: RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.71; 60 children).

In children receiving alternate‐day prednisone, changing to daily prednisone at the onset of URTI may make little or no difference to the risk of relapse (Analysis 7.1.3: RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.19; 110 children; 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

PREDNOS 2 2022 reported that in those receiving alternate‐day prednisone and other immunosuppressive agents, changing to daily prednisone at the onset of URTI may make little or no difference to the risk of relapse (Analysis 7.1.4: RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.50; 89 children).

PREDNOS 2 2022 reported that in those receiving other immunosuppressive agents without prednisone, commencing daily prednisone at the onset of URTI may make little or no difference to the risk of relapse (Analysis 7.1.5: RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.28; 43 children).

Gulati 2011 reported daily prednisone therapy, administered at the onset of URTI, may reduce the infection‐related relapses/patient‐years (Analysis 7.2.1: MD ‐0.70, 95% CI ‐0.87 to ‐0.53; 95 children) and the total number of relapses/patient/year (Analysis 7.2.2: MD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐1.08 to ‐0.72; 95 children).

Mattoo 2000 reported daily prednisone, administered at the onset of URTI, may reduce total relapse episodes/patient at two years compared with alternate‐day prednisone (Analysis 7.3: MD ‐3.30, 95% CI ‐4.03 to ‐2.57; 36 children).

In a cross‐over study in children who had not received alternate‐day prednisone for at least three months, Abeyagunawardena 2017 reported daily prednisone administered at the onset of URTI resulted in 11 relapses associated with 115 episodes of URTI in 33 children compared with 25 relapses associated with 101 episodes of URTI in 33 children completing two years.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Daily prednisolone treatment during viral infections, Outcome 1: Number with relapse with infection

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Daily prednisolone treatment during viral infections, Outcome 2: Number of relapses/patient

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Daily prednisolone treatment during viral infections, Outcome 3: Number of relapses/patient at 2 years

Deflazacort versus prednisone therapy in children with relapsing or initial episodes of SSNS

Deflazacort, compared with prednisone, may make little or no difference to the number of children achieving remission (Analysis 8.1: RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.24; 67 children, 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

Deflazacort, compared with prednisone, may reduce the number of children with relapses by nine to 12 months (Analysis 8.2: RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.78; 63 children, 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

No differences in time to remission or time to relapse in 11 children treated with deflazacort or methylprednisolone were found in a cross‐over study by Liern 2008.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Deflazacort versus prednisolone, Outcome 1: Number with remission

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Deflazacort versus prednisolone, Outcome 2: Number with relapse by 9 to 12 months

Alternate‐day or daily therapy versus intermittent therapy in relapsing SSNS

-

Number relapsing during therapy.

APN 1981 reported uncertain effects between alternate‐day therapy and intermittent therapy on the number of children relapsing during therapy (Analysis 9.1.1: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.02; 48 children).

ISKDC 1979 reported daily therapy may reduce the number of children relapsing during therapy compared to intermittent therapy (Analysis 9.1.2: RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.82; 50 children)

-

Number with relapses by nine to 12 months.

APN 1981 reported little or no difference in the number of children with relapses by nine to 12 months between alternate‐day and intermittent therapy (Analysis 9.2.1: RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.55; 48 children).

ISKDC 1979 reported little or no difference in the number of children with relapses by nine to 12 months between daily and intermittent therapy (Analysis 9.2.2: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.12; 50 children).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9: Alternate‐day or daily steroid regimens versus intermittent dosing to prevent relapse, Outcome 1: Number relapsing during therapy

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9: Alternate‐day or daily steroid regimens versus intermittent dosing to prevent relapse, Outcome 2: Number with relapses by 9 to 12 months

Intravenous then oral therapy versus oral therapy alone

Imbasciati 1985 reported little or no difference in the number of children relapsing by six months between IV then oral therapy and oral therapy alone (Analysis 10.1: RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.52; 64 children).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10: Intravenous then oral therapy versus oral therapy alone, Outcome 1: Relapse by 6 months

Single versus multiple daily doses in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

There may be little or no difference between single daily doses versus divided daily dosing in the number with relapse (Analysis 11.1: RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.42; 151 children; 2 studies; I2 = 0%)

Ekka 1997 reported little or no difference between single daily doses versus divided daily dosing in the mean relapse rate (Analysis 11.2: MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.64 to 0.24; 94 children).

There may be little or no difference in the mean time to remission between single daily doses and divided daily dosing (Analysis 11.3: MD 0.70 days, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 1.96; 242 children; 3 studies; I2 = 60%).

There may be little or no difference in the mean time to remission between single daily and divided daily dosing according to age group (Analysis 11.4)

Serious adverse events may be less common with single daily doses compared with divided daily dosing (Analysis 11.5: RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.91; 138 children, 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

Ekka 1997 reported no differences in the cumulative steroid dose between single daily doses versus divided daily dosing (Analysis 11.6: MD ‐0.05 mg/kg, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.58; 94 children).

Khan 2023 reported that the number of children with HPA suppression did not differ between groups (Analysis 11.7)

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 1: Number with relapse

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 2: Mean relapse rate

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 3: Number of days to remission

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 4: Number of days to remission according to age group

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 5: Serious adverse events

11.6. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 6: Cumulative steroid dose [mg/kg]

11.7. Analysis.

Comparison 11: Single versus divided daily doses of prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 7: Number with HPA suppression

Reduced versus standard prednisone doses in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

There may be little or no difference in time to remission between reduced (1 mg/kg) and standard prednisone doses (2 mg/kg) (Analysis 12.1: MD 0.72 days, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 1.88; 75 children; 2 studies; I2 = 11%).

There may be little or no difference in the number relapsing between reduced and standard prednisone doses (Analysis 12.2: RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.20; 177 children; 4 studies; I2 = 0%).

Kainth 2021 reported there may be little or no difference in the number developing FRNS or SDNS between reduced duration (two weeks) and standard duration (four weeks) of alternate‐day prednisone (Analysis 12.3: RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.91; 117 children).

Borovitz 2020 reported that compared to a dose of 2 mg/kg/day, the cumulative dose of prednisone to achieve remission may be less in children treated with a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (Analysis 12.4: MD ‐20.60 mg/kg, 95% CI ‐25.65 to ‐15.55; 20 children).

-

Adverse events

Tu 2022 reported that there may be no difference in growth or steroid adverse events with low versus conventional dose prednisone (Analysis 12.5).

Borovitz 2020 reported that none of the included children had treatment‐related complications.

Kansal 2019 reported that prednisone adverse events were more common in the standard dose group compared with the low dose group.

Kainth 2021 identified no differences in the number of days to relapse or in steroid adverse effects between reduced duration and standard duration of alternate‐day prednisone.

Sheikh 2019 did not provide any information on adverse effects.

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12: Reduced versus standard steroid doses to prevent relapse, Outcome 1: Time to remission

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12: Reduced versus standard steroid doses to prevent relapse, Outcome 2: Number with relapse

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12: Reduced versus standard steroid doses to prevent relapse, Outcome 3: Number with FRNS or SDNS at 12 months

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12: Reduced versus standard steroid doses to prevent relapse, Outcome 4: Cumulative prednisone dose to achieve remission [mg/kg]

12.5. Analysis.

Comparison 12: Reduced versus standard steroid doses to prevent relapse, Outcome 5: Adverse events

Daily versus alternate‐day prednisone in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Yadav 2019 reported daily, compared with alternate‐day prednisone, may reduce the number of relapses during 12 months of therapy (Analysis 13.1: MD ‐0.90 relapses/year, 95% CI ‐1.33 to ‐0.47; 62 children).

Yadav 2019 reported there may be little or no difference in the frequency of Cushingoid facies or cataracts (Analysis 13.2).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13: Daily versus alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 1: Number of relapses in 12 months [number/year]

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13: Daily versus alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 2: Adverse events

Short‐duration alternate‐day prednisone without taper of dose versus long‐duration alternate‐day prednisone with tapering dose in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

PROPINE 2020 reported administering alternate‐day prednisone for 36 days compared with a tapering dose given over 72 days using the same cumulative prednisone dose in each group may make little or no difference to the risk of relapsing during treatment (Analysis 14.1: RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.19; 78 children) or at six months (Analysis 14.2: RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.16; 78 children).

PROPINE 2020 reported there may be little or no difference in the frequency of viral infection, bacterial infection, or urticaria (Analysis 14.3).

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14: Short (36 days) versus long (72 days) duration alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 1: Number with relapse during treatment

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14: Short (36 days) versus long (72 days) duration alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 2: Number with relapse by 6 months

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14: Short (36 days) versus long (72 days) duration alternate‐day prednisone to prevent relapse, Outcome 3: Adverse events

Weight‐based versus body surface area‐based dosing of prednisone in relapsing nephrotic syndrome

Weight‐based dosing may make little or no difference to the number relapsing at six months compared to BSA‐based dosing (Analysis 15.1: RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.49; 146 children; 2 studies; I2 = 0%).

Weight‐based dosing may make little or no difference to the risk of adverse events compared to BSA‐based dosing (Cushingoid features, serious infections, eye changes, hypertension) (Analysis 15.2: 144 children; 2 studies).

Basu 2020 reported that the mean prednisone dose for both the induction dose over six months and the cumulative dose over six months was lower in the weight‐based dosing group compared with the BSA‐based dosing group (Analysis 15.3.1: ‐32.00 g/kg, 95% CI ‐57.21 to ‐6.79; Analysis 15.3.2: ‐30.00 g/kg, 95% CI ‐54.34 to ‐5.66).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15: Weight‐based versus body surface area (BSA)‐based dosing of prednisolone, Outcome 1: Relapse at 6 months

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15: Weight‐based versus body surface area (BSA)‐based dosing of prednisolone, Outcome 2: Adverse events

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15: Weight‐based versus body surface area (BSA)‐based dosing of prednisolone, Outcome 3: Prednisone dose

Prolonged steroid therapy for children with relapsing SSNS

Jayantha 2002b reported seven months of prednisone may reduce the number of relapses at six months (Analysis 16.1.1: RR 0.04, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.25; 90 children), 12 months (Analysis 16.1.2: RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.65; 76 children) and 24 months (Analysis 16.1.3: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.80; 64 children) compared to two months of therapy.

Jayantha 2002b reported the relapse rate/patient/year was lower with seven months of prednisone compared to two months at 12 months (Analysis 16.2.1: MD ‐1.78, 95% CI ‐2.30 to ‐1.26; 72 children), 24 months (Analysis 16.2.2: MD ‐1.79, 95% CI ‐2.39 to ‐1.19; 55 children), and 36 months (Analysis 16.2.3: ‐RR 1.74, 95% CI ‐2.39 to ‐1.09; 41 children).

Jayantha 2002b reported the number with FRNS or SDNS was lower with seven months of prednisone (Analysis 16.3: RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.95; 72 children) compared to two months of prednisone.

Jayantha 2002b reported the cumulative prednisone dose was lower at one year with two months of treatment (Analysis 16.4.1: MD 0.59 g/kg, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.16; 72 children), but there was little or no difference at two years (Analysis 16.4.2: MD ‐0.32 g/kg, 95% CI ‐1.52 to 0.88; 55 children) or three years (Analysis 16.4.3: MD ‐1.13, 95% CI ‐3.08 to 0.82; 41 children) compared to seven months of prednisone.

Jayantha 2002b reported there may be little or no difference in hypertension or growth failure between seven months and two months of prednisone (Analysis 16.5).

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16: Prolonged steroid therapy (7 months) for relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Outcome 1: Number with relapses

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16: Prolonged steroid therapy (7 months) for relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Outcome 2: Relapse rate/patient/year

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16: Prolonged steroid therapy (7 months) for relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Outcome 3: Number with FRNS or SDNS

16.4. Analysis.

Comparison 16: Prolonged steroid therapy (7 months) for relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Outcome 4: Cumulative steroid dose

16.5. Analysis.

Comparison 16: Prolonged steroid therapy (7 months) for relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Outcome 5: Adverse events

Cortisol supplementation in children with relapsing nephrotic syndrome and adrenocortical suppression