Abstract

Background

Adherence to complex regimens for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes is often poor. Interventions to enhance adherence require intensive education and behavioural counselling. However, whether the existing evidence is scientifically rigorous and can support recommendations for routine use of educational programmes in people with CKD and diabetes is still unknown. This is an update of a review first published in 2011.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of education programmes for people with CKD and diabetes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 19 July 2024 using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs investigating the benefits and harms of educational programmes (information and behavioural instructions and advice given by a healthcare provider, who could be a nurse, pharmacist, educator, health professional, medical practitioner, or healthcare provider, through verbal, written, audio‐recording, or computer‐aided modalities) for people 18 years and older with CKD and diabetes.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened the literature, determined study eligibility, assessed quality, and extracted and entered data. We expressed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and continuous data as mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. Data were pooled using the random‐effects model. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

Eight studies (13 reports, 840 randomised participants) were included. The overall risk of bias was low for objective outcomes and attrition bias, unclear for selection bias, reporting bias and other biases, and high for subjective outcomes.

Education programmes compared to routine care alone probably decrease glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (4 studies, 467 participants: MD ‐0.42%, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.31; moderate certainty evidence; 13.5 months follow‐up) and may decrease total cholesterol (179 participants: MD ‐0.35 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐00.07; low certainty evidence) and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (179 participants: MD ‐0.40 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.14; low certainty evidence) at 18 months of follow‐up.

One study (83 participants) reported education programmes for people receiving dialysis who have diabetes may improve the diabetes knowledge of diagnosis, monitoring, hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, medication with insulin, oral medication, personal health habits, diet, exercise, chronic complications, and living with diabetes and coping with stress (all low certainty evidence). There may be an improvement in the general knowledge of diabetes at the end of the intervention and at the end of the three‐month follow‐up (one study, 97 participants; low certainty evidence) in people with diabetes and moderately increased albuminuria (A2).

In participants with diabetes and moderately increased albuminuria (A2) (one study, 97 participants), education programmes may improve a participant’s beliefs in treatment effectiveness and total self‐efficacy at the end of five weeks compared to routine care (low certainty evidence). Self‐efficacy for in‐home blood glucose monitoring and beliefs in personal control may increase at the end of the three‐month follow‐up (low certainty evidence). There were no differences in other self‐efficacy measures.

One study (100 participants) reported an education programme may increase change in behaviour for general diet, specific diet and home blood glucose monitoring at the end of treatment (low certainty evidence); however, at the end of three months of follow‐up, there may be no difference in any behaviour change outcomes (all low certainty evidence). There were uncertain effects on death, serious hypoglycaemia, and kidney failure due to very low certainty evidence. No data was available for changes in kidney function (creatinine clearance, serum creatinine, doubling of serum creatinine or proteinuria).

For an education programme plus multidisciplinary, co‐ordinated care compared to routine care, there may be little or no difference in HbA1c, kidney failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), systolic or diastolic blood pressure, hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, and LDL and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (all low certainty evidence in participants with type‐2 diabetes mellitus and documented advanced diabetic nephropathy). There were no data for death, patient‐orientated measures, change in kidney function (other than eGFR and albuminuria), cardiovascular disease morbidity, quality of life, or adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

Education programmes may improve knowledge of some areas related to diabetes care and some self‐management practices. Education programmes probably decrease HbA1c in people with CKD and diabetes, but the effect on other clinical outcomes is unclear. This review only included eight studies with small sample sizes. Therefore, more randomised studies are needed to examine the efficacy of education programmes on important clinical outcomes in people with CKD and diabetes.

Keywords: Humans; Bias; Diabetes Mellitus; Diabetes Mellitus/therapy; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/therapy; Glycated Hemoglobin; Glycated Hemoglobin/metabolism; Medication Adherence; Patient Education as Topic; Patient Education as Topic/methods; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic/therapy

Plain language summary

Do education programmes improve outcomes in people with both chronic kidney disease and diabetes?

Key messages

• For people with both chronic kidney disease (a long‐term condition where the kidneys do not work effectively) and diabetes (a lifelong condition that causes a person's blood sugar level to become too high), education programmes (planned activities designed to improve a person's ability to manage their condition) may improve their knowledge of diabetes, their ability to manage their condition, and self‐management behavioural changes.

• However, the small number of people enrolled in these studies and the wide range of outcomes reported means our findings must be interpreted cautiously. Larger, well‐designed studies with common outcomes and longer follow‐ups are needed.

Why is improving diabetes care important for people with kidney disease?

Chronic kidney disease (a long‐term condition where the kidneys do not work effectively) and diabetes (a lifelong condition that causes a person's blood sugar level to become too high) are chronic conditions that bring on many challenges for people, particularly when they have to manage both at the same time. Diabetes can accelerate the development of kidney disease and is the leading cause of kidney failure (a condition where the kidneys no longer function well enough to keep a person alive). While sticking to complex treatment plans can be challenging, successful self‐management in the early stages of kidney disease can improve outcomes later in life and delay the need for dialysis or a kidney transplant.

What are education programmes?

Education programmes are any set of planned activities designed to improve a person's ability to manage their condition and delay the progression of their kidney disease. These activities can aim to improve a person's knowledge of their disease, self‐care activities, and their ability to self‐monitor the disease, thus encouraging and motivating them to create healthy lifestyle changes, improve their treatment compliance, and improve quality of life.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out whether an education programme designed for people with both kidney disease and diabetes helps them understand their condition and recognise the importance of strategies aimed at slowing its progression and preventing long‐term complications.

What did we do?

We searched for randomised studies (studies in which participants are assigned randomly to two or more treatment groups) that compared education programmes to usual care for people with both kidney disease and diabetes. We compared and summarised the results and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We included eight studies involving 840 people 18 years or older with both kidney disease and diabetes. Four studies were undertaken in multiple centres, and four studies were performed in single centres. The duration of follow‐up ranged from 12 weeks to four years. Most of the education programmes were designed to increase a person's knowledge of their condition and improve self‐management behaviours. One study focused on reducing stress using mindfulness (a person's ability to be aware of where they are and what they are doing), and it was adapted to include practices for complex thoughts and feelings related to diabetes, and one study used a co‐ordinated medical care approach with multiple practitioners involved in a person's care.

Overall, education programmes probably lower blood glucose levels and may lower total cholesterol and blood pressure, but may make little or no difference to kidney function, abnormally low or high blood sugar, and cardiovascular disease (disorders of the heart and blood vessels).

For people with diabetes on dialysis (a procedure to remove waste products and excess fluid from the blood when the kidneys stop working properly), an education programme may improve their knowledge of diabetes, self‐management behaviour for checking their feet, using lotion, wearing appropriate shoes and socks, and coping with stress.

For people with moderately increased protein in the urine, there may be an improvement in their general knowledge of diabetes, their confidence in monitoring their blood sugar levels at home, their beliefs in their personal control, as well as behavioural changes to their diet. There may be no behavioural changes to exercise, foot care, or quitting smoking.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We have low confidence in education programmes improving the understanding of diabetes in people with kidney disease. This is because the number of studies reporting outcomes of interest was low, and the education programmes varied, so we were unable to properly analyse the results.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

The evidence is current to July 2024.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Education programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone for people with chronic kidney disease and diabetes.

| Education programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone for people with CKD and diabetes | |||||

| Patient or population: people with CKD and diabetes Settings: multiple settings Intervention: education programmes plus routine care Comparator: routine care alone | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect 95% CI |

No. of participants (RCTs) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Routine care alone | Education programmes plus routine care | ||||

| All‐cause death Follow‐up: 9 months |

41 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (13 to 91) | 0.83 (0.31 to 2.19) | 424 (4) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW 1,2 |

| Serious hypoglycaemia Follow‐up: 18 months |

67 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 90) | 0.08 (0.0 to 1.33) | 179 (1) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW 1,3 |

| HbA1c (%) Mean follow‐up: 13.5 months |

The mean HbA1c was 0.42% lower with education programmes plus routine care (0.53% lower to 0.31% lower) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 467 (4) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ MODERATE 1 | |

| Behaviour change: home blood glucose monitoring (SDSCA) (higher score better) Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention | The mean change in home blood glucose monitoring score was 2.13 higher with education programmes plus routine care (1.18 higher to 3.08 higher) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 100 (1) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW 1,3 | |

| Behaviour change: home blood glucose monitoring (SDSCA) (higher score better) Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean change in home blood glucose monitoring score was 11.28 higher with education programmes plus routine care (1.92 higher to 20.64 higher) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 79 (1) | ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ ⊖ VERY LOW 3,4 |

|

| Quality of life: PHQ stress score (lower score better) Follow‐up: 12 months |

The mean PHQ stress score was ‐1.70 lower with education programmes plus routine care (‐3.09 lower to ‐0.31 lower) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 103 (1) | ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ ⊖ VERY LOW3,4 | |

| General knowledge of diabetes (ADDQoL) (higher score better) Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean ADDQoL general knowledge score was 14.39 higher with education programmes plus routine care (7.45 higher to 21.33 higher) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 97 (1) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW 1,3 | |

| Self‐efficacy at the end of education intervention (ADDQoL) (higher score better) Follow‐up: 5 weeks |

The mean ADDQoL self‐efficacy total score was 19.00 higher with education programmes plus routine care (12.58 higher to 25.42 higher) compared to routine care alone | ‐ | 97 (1) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊖ ⊖ LOW1,3 |

|

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADDQoL: Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life; CI: Confidence interval; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; MD: Mean difference; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; RR: Risk ratio; SDSCA: Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities | |||||

| GRADE Working User Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Due to serious risk of bias

2 Due to serious imprecision (due to low events)

3 Due to serious imprecision

4 Due to very serious risk of bias

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health problem affecting 5% to 10% of the global population, contributing to over 1.1 million deaths worldwide in 2015 (GBD 2015; KDIGO 2009). Diabetes mellitus (DM) can accelerate CKD development, and it is recognised as the leading cause of kidney failure and results in a poorer prognosis for patients (AIHW 2024; Chantrel 1999; Kasper 2005; KDOQI 2007; KDOQI 2012; KHA 2010; Narres 2016; Shen 2016; Toto 2002; USRDS 1998; USRDS 2005; USRDS 2009). Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a progressive disease revealed by clinical assessment, including measurement of albuminuria, reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), or both. Patients ordinarily have the presence of severely elevated albuminuria > 300 mg/24 hours (or > 200 μg/min) or a urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio (UACR) > 300 mg/g (confirmed in at least two of three samples), as well as diabetic retinopathy and the absence of signs of other forms of kidney disease. Patients will usually have raised blood pressure (BP) and more significant cardiovascular morbidity and death (De Boer 2011; Persson 2018). More than 90% of people with DM have type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and the annual growth rate of DM‐related CKD is expected to grow dramatically due to an increase in people with T2DM. In 2020, within a primary care setting, the estimated prevalence of CKD stages 3 to 5 (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) in T2DM patients was estimated at 24.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 21.9 to 27.0) (Jitraknatee 2020).

The clinical manifestations of DKD have changed over recent years, and the definition of DKD has expanded. Typically, the first clinical signs of DKD were an increase in urine albumin excretion, worsening to albuminuria, followed by a loss of GFR. In comparison, it is now not uncommon to see patients who have a steady decline in GFR without albuminuria (approximately 6% of DKD patients); this is possibly due to advancement in early detection and treatment (Afkarian 2016; Foley 2009; Gheith 2016; Selvin 2007; White 2014). Alarmingly, approximately 20% to 50% of T2DM patients and nearly half of patients with type 1 DM (T1DM) develop DKD throughout their lifetime, and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data found approximately 8.2 million adults with DM (95% CI 6.5 to 9.9 million adults) had albuminuria, reduced eGFR, or both from 2009 to 2014 (Afkarian 2016; Gheith 2016; Ritz 1999).

Recent evidence suggests that the overall prevalence of DKD has not significantly changed over time from 28.4% (95% CI 23.8% to 32.9%) between 1988 and 1994 to 26.2% (95% CI 22.6% to 29.9%) between 2009 and 2014 (prevalence ratio, 0.95, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.06; adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity; P = 0.39 for trend). However, the population of existing patients whose kidney failure was caused by DM (tripled from 1990 to 2000) is expected to grow 10‐fold by 2030, to 1.3 million (Collins 2005). This significant burden will further stress already struggling healthcare systems worldwide (Aziz 2018). In the USA, DKD accounts for 50% of kidney failure, up from 18% in 1980 (De Boer 2011; KDOQI 2007). It is estimated that 10% of deaths in T2DM patients are attributable to kidney failure (van Dieren 2010). DM and CKD are common and are synergistically associated with premature death in the general population (Middleton 2006; Narres 2016; Shen 2016). The survival of patients with DKD decreases once kidney failure occurs and is estimated as low as 40% in five years (Shen 2016). Furthermore, data from studies conducted in the USA show a high economic burden associated; the medicare costs spent on the kidney failure programme were about 26.8 billion US dollars in 2008 (De Boer 2011; USRDS 2000; USRDS 2001).

Description of the intervention

People who are well‐equipped to self‐manage their condition are likely to be more empowered to make better health‐related decisions (Anekwe 2018; Chen 2016; Slama‐Chaudhry 2019). Education interventions can potentially reduce the economic burden and demand for health service provision (Chen 2016). These factors justify the intensive efforts needed to prevent CKD and DM progression through education to improve self‐management. The success of strategies to promote glycaemic control and minimise the progression of DKD depends on patients' ability and willingness to change and subsequently maintain appropriate lifestyle behaviours regarding diet, physical activity, adjusting to psychological and social demands, managing complex medication regimens, self‐monitoring, and engaging in effective interactions with health care providers and medical follow‐up visits (Anekwe 2018; Captieux 2018; Slama‐Chaudhry 2019). Adherence to complex regimens remains challenging, and a multifactorial treatment approach that includes patient education can support self‐management for people with both CKD and diabetes (Persson 2018). For this review's purpose, education programmes are defined as any set of planned educational activities designed to improve the person's ability to manage and delay the progression of their CKD.

How the intervention might work

Behaviour can be modified in many ways to minimise disease burden across all stages of DM and CKD. A well‐designed education programme is a vital resource to support behaviour change and may provide advice to help people make more informed health choices and adhere to recommended medical regimes (Aziz 2018; Kim 2019). Education interventions may improve knowledge of their disease and empower and motivate them to create healthy preventative strategies that ultimately slow the progression of CKD and DM.

Other education interventions might be more hands‐on, involving training for self‐care activities or disease self‐monitoring. This may include the patient's caregivers or a multidisciplinary care team (Baig 2015; Shi 2016). For some people, having more responsibility for day‐to‐day disease management makes them feel more in control of their condition. It may improve their quality of life (QoL), emotional well‐being, and other DM and CKD outcomes (Windrum 2016). Similar interventions might be more directed at improving medication adherence. Patients with a good grasp of their condition have better compliance and satisfaction with their medical regimen and fewer missed appointments (Kaplan‐Lewis 2013).

The efficacy of educational programmes for those with DM has been studied comprehensively for several decades (ADA 2001; Boulton 1998; Calman 1994; Captieux 2018; Duke 2009; Hawthorne 2008; KDOQI 2007; Norris 2002; Pecoraro 1990). Several meta‐analyses and systematic reviews of education interventions have demonstrated that they are effective in producing positive patient outcomes in terms of glycaemic control, weight management, adherence to medications, and improvement of psychological well‐being and QoL in diverse socio‐economic and ethnic communities (Brown 1990; Captieux 2018; Dorresteijn 2014; Ellis 2004; Gary 2003; Norris 2002; Steed 2003). Similar findings have been found in systematic reviews in the general CKD population, with the addition of improvement in knowledge, self‐efficacy, lifestyle modification (exercise and diet), death, dialysis therapy initiation, and important clinical outcomes (serum albumin, proteinuria, and haemoglobin) (Lopez‐Vargas 2016; Persson 2018).

Overall, DM is primarily a self‐managed disease, and in turn, so is having both CKD and DM, particularly in the early stages of CKD progression (Windrum 2016). Given the complex nature of managing both CKD and DM concurrently, it is likely that interventions will need to be tailored to each patient's circumstances to meet the needs of patients with diverse ethnic, cultural, literacy, and geographical backgrounds, particularly when other co‐morbidities are taken into account. Other essential factors that must be considered include ethnic, cultural, literacy, cognitive, and geographical factors, as recognised in recent guidelines (KDIGO 2022). In many cases, patients will work together with several healthcare professionals, and the overall care plan for the patient is usually dynamic. The healthcare professionals may include a general practitioner, nephrologist, diabetes specialist, health care navigator, nurse‐educator, dietician, psychologist, podiatrist, family member or caregiver, and social worker. The type of education conveyed may also influence how effective the intervention is. Evidence from the DM population has suggested that having “patient‐centred education”, where self‐management plans are developed and maintained through a collaboration between patients and their health care providers, is more effective at improving glycaemic control, changing behaviours, and maintaining compliance compared to when the patient has little involvement (Windrum 2016). Background knowledge of both CKD and DM helps patients understand their disease and recognise the importance of strategies aimed at secondary and tertiary prevention of DKD, hyperglycaemia and hypertension.

Why it is important to do this review

Evidence suggests that educational programmes aimed at lifestyle modification might be effective in slowing down the progression of coexisting CKD and DM. Early intervention and advice to patients about regular screening and medical adherence are important to stop DM and CKD from accelerating and leading to kidney failure. There is the potential to reduce the risk of death and other clinical outcomes and improve the QoL. Whether the existing evidence is scientifically rigorous and can support recommendations for the routine use of educational programmes in coexisting CKD and DM is still unknown.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of education programmes for people with both CKD and DM.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at the benefits and harms of educational programmes for people with both CKD and DM were included. In randomised cross‐over studies, only the first period before cross‐over was included.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

People aged 18 years or over with both CKD and T1DM or T2DM, or DKD were included.

Definition of CKD

Participants with CKD stages G1 to G5 (people with G1 required moderately (A2) to severely (A3) increased albuminuria, including kidney replacement therapy (KRT) or transplant) as outlined in KDIGO 2022a.

Definition of DM

According to WHO criteria (WHO 1999), fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and two‐hour plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L.

Definition of DKD

DKD is defined by albuminuria (urinary albumin excretion (UAE) ≥ 3.4 mg/mmol (30 mg/g)) and progressive reduction in estimated (e)GFR in the setting of a long duration of diabetes (> 10 years' duration of T1DM diabetes; may be present at diagnosis in T2DM) and is typically associated with retinopathy.

Exclusion criteria

People with kidney damage due to DM other than T1DM or T2DM, such as gestational diabetes, were excluded.

Types of interventions

Any educational programme (or programmes that include education) used for people with both CKD and DM to prevent the progression of CKD, improve diabetic control, and improve QoL.

Educational programmes have to comprise information and behavioural instructions and advice given by a healthcare provider, who could be a nurse, pharmacist, educator, health professional, medical practitioner, or healthcare provider, through verbal, written, audio‐recording, or computer‐aided modalities.

The educational intervention could occur in the emergency department, hospital, the person's home, or in the community.

Interventions that included pharmacological therapies in the intervention arm alone were excluded. Standard care across both arms, including pharmacological interventions, was included.

The mode of delivery and reach of the intervention depended on the aim of the intervention, but all types were included in this review. Examples of delivery modes may include but were not limited to, face‐to‐face, over the phone, group sessions, computer, DVD, mobile application, or a mix.

Interventions that compare technology, such as medical device aids, were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The time intervals at which outcome assessment takes place may affect the outcomes of educational programmes. If the data were available, we considered six months, one, and two years as standard time intervals.

Primary outcomes

Death: (including all causes of death; DKD‐related death (total and specific death rates from causes attributable to DKD); cardiovascular‐related death)

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c); attaining a HbA1c target

Kidney failure

Patient‐oriented measures of knowledge, self‐management, and behavioural changes: attitude scales; knowledge of DKD/DM; patient empowerment and self‐efficacy; patient behavioural changes (including smoking cessation, increased exercise, diet modification, and adherence to medications); any other self‐management measures.

Secondary outcomes

Kidney function measures during follow‐up: creatinine clearance, eGFR, serum creatinine (SCr), doubling SCr, proteinuria, and albuminuria

BP (changes in or mean): total, systolic (SBP), and diastolic (DBP)

Glycaemic events: hypoglycaemia, severe hypoglycaemia (measured as having low blood glucose levels that require assistance from another person to treat)

Cardiovascular (CV) morbidity (non‐fatal): total CV disease events (stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, any other reported CV events); the incidence of peripheral heart disease

Measures of QoL (any scale); health‐related QoL (any scale)

Lipids: total cholesterol; low‐density lipoprotein (LDL); high‐density lipoprotein (HDL); triglycerides

Adverse events: any adverse events related to the educational programmes (e.g. deteriorating QoL or biomedical parameters).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 19 July 2024 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources:

Monthly searches the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Hand searching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's scope. Details of search strategies and a list of hand‐searched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

The previous version of the review (Li 2011) searched the following databases and resources for the initial review. Please note the databases listed below were not searched for this 2024 update.

Four Chinese medicine databases: CBM‐disc (1979 to December 2009), Chinese Science and Technique Journals Database (VIP) (until December 2009), China National Infrastructure (CNKI) (until December 2009) and the WanFang database (until December 2009)

Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC) (www.eric.ed.gov) (July 2010)

Campbell Collaboration's Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Trials Register (geb9101.gse.upenn.edu)

European Medicines Agency (EMEA) (www.emea.europa.eu/index/indexh1.htm) (July 2010).

The previous version of the review (Li 2011) and the 2024 update also sought information from the following.

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies were sent to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was performed to identify eligible studies. Two authors (BC, TC) independently determined each study's eligibility, identified by the search, by reading the title, abstract, and, if necessary, the full text. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author (DT). Studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. The review authors then independently eliminated studies that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria and obtained full copies of the remaining studies.

Two review authors (BC, TC) independently read these reports to select relevant studies. We included studies regardless of whether measured outcome data were reported in a 'usable' way.

Where duplication reports of the same study were confirmed, the initial first complete publication (index publication) was selected. It was the primary data source, but additional prior or subsequent reports were also included. These other prior or subsequent reports containing supplementary outcome data (e.g. longer‐term follow‐up or different outcomes) also contributed to the meta‐analysis.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (BC, TC) independently extracted data using a standard form and checked for agreement before entry into Review Manager. Unclear data were clarified by contacting the author of the study report, and any relevant data obtained in this manner were included in the review.

We included information about the type of education intervention, the number of participants treated, the study design (standard of care or active control), the study duration and follow‐up, important kidney function, diabetic, cardiovascular, and QoL outcome measures and results, withdrawals, and adverse events.

We collected the studies' characteristics in sufficient detail to complete the table of the included studies' characteristics. In the event of disagreement, a third review author adjudicated (DT).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors (BC, TC) using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2022) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Was incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. incidence of all‐cause death, DKD‐related death, CV disease‐related death, incidence of kidney death during follow‐up, kidney failure, CV disease events, self‐management, behavioural change, adverse events), results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with a 95% CI.

Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of educational programmes (e.g. eGFR, SCr, albuminuria, UACR, proteinuria, BP, lipids, blood glucose, QoL, behaviour change), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales were used with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

If non‐standard designs were found, such as cluster RCTs and cross‐over studies, then the analysis would have been conducted following the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook to avoid unit‐of‐analysis errors (Higgins 2022).

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by correspondence, and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Where a study reported outcome data after excluding some randomised participants from the denominator, further information required from the original author was requested by email, and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients, as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol population, were carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example, drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. the last observation carried forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2022). We used a modified ITT analysis where the ITT population consisted of participants who were randomised, received at least one dose of the assigned study treatment and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. We assigned missing participants zero improvements wherever possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed for statistical heterogeneity visually by inspecting forest plots of standardised mean effect sizes and risk ratios. Furthermore, we applied a Chi2 test to assess heterogeneity. With P < 0.10 used to denote statistical significance and with I2 calculated to measure the proportion of total variation in the estimates of treatment effect due to heterogeneity beyond chance (Higgins 2022), we used conventions of interpretation that were defined by Higgins 2003. However, the limited amount of study data published did not enable meaningful interpretation. We had also planned to conduct subgroup analysis and meta‐regression to evaluate potential sources of heterogeneity, but this was not possible because of the small number of studies of paired interventions.

Assessment of reporting biases

If sufficient RCTs were identified, an attempt was made to examine for publication bias using a funnel plot (Higgins 2022). We planned to assess publication bias using a method designed to detect the amount of unpublished data with a null effect required to make any result clinically irrelevant (usually taken to mean a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10 or higher) (Higgins 2022). Insufficient studies were identified to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

Data were abstracted from individual studies and then pooled using random‐effects meta‐analysis. The random‐effects model was chosen because it provides a more conservative estimate of effect in the presence of known or unknown potential heterogeneity (Deeks 2001). The statistical method used was Mantel‐Henzel meta‐analysis for dichotomous data and generic inverse variance meta‐analysis for continuous data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was to be used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants, interventions and study quality). Heterogeneity amongst participants could be related to age, type of diabetes, and CKD (e.g. pre‐dialysis patients, patients on dialysis, and transplant patients). Heterogeneity in educational programme interventions could be related to educational content (e.g. BP programmes, diabetes programmes, weight control programmes), the healthcare providers, mode, and administration duration. Adverse effects were to be tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques as they were likely different for the various educational programmes used. The risk difference (RD) with 95% CI was to be calculated for each adverse effect, compared with no administration of education programmes. There were insufficient studies identified to undertake subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses were considered.

Repeating the analysis, excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis, taking account of the risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis, excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country the study was conducted in.

However, insufficient data were available to determine the influence of the effect size.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We have presented the main results of the review in the summary of findings tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2022a). The summary of findings tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the certainty of the evidence as to the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves considering the within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), the directness of evidence, heterogeneity, the precision of effect estimates, and publication bias (Schünemann 2022b).

In the summary of findings table for the comparison of an education programme plus routine care versus routine care, we presented the following outcomes.

Death (all causes)

Glycaemic events: serious hypoglycaemia

HbA1c (%)

Behaviour change at the end of treatment (five weeks): home blood glucose monitoring (HBGM)

Behaviour change at three months follow‐up: home blood glucose monitoring

QoL: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) stress score

Self‐efficacy at the end of education intervention

General knowledge of diabetes at the end of education intervention

No summary of findings tables were presented for other comparisons due to insufficient data.

Results

Description of studies

The following section contains broad descriptions of the studies considered in this review. For further details on each individual study, please see Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

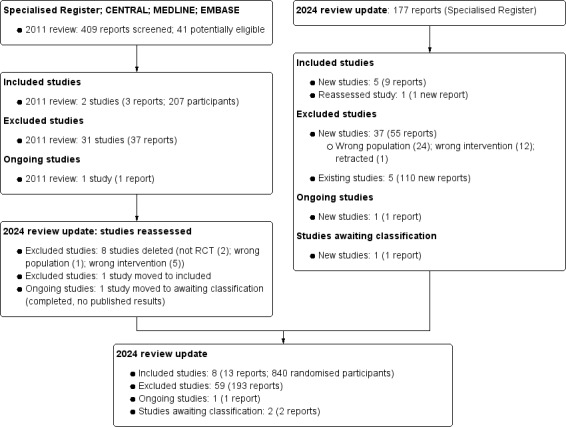

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies (up to 19 July 2024) and identified 177 reports. Five new studies (nine reports) were included, 37 studies (55 reports) were excluded, and one ongoing study (one report) was identified. One new study is awaiting classification (recently completed; no data available). We also identified 110 new reports of existing excluded studies.

We reassessed and reclassified one excluded study as an included study (Fogelfeld 2017), and one ongoing study has now been completed and moved to Studies awaiting classification as no data have been published (NCT00782847). Finally, eight excluded studies have been deleted (not randomised, wrong population or intervention).

Eight studies were included (13 reports, 840 randomised participants), 59 were excluded, two are awaiting classification, and one study is ongoing (Figure 1).

1.

Flow chart showing study selection

Included studies

Eight studies were included (13 reports, 840 randomised participants) (C‐DIRECT 2019; Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; McMurray 2002; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010; Steed 2005).

See Characteristics of included studies.

All studies enrolled adults. C‐DIRECT 2019 reported participants older than 21 years, Fogelfeld 2017 included participants between 18 and 70 years, Kopf 2012 included participants between 30 and 70 years, MESMI 2010 included participants > 18 years, and Steed 2005 included adults < 70 years of age. Guo 2022, McMurray 2002, and MEMO 2011 did not report the age range.

C‐DIRECT 2019, McMurray 2002, MEMO 2011 and Steed 2005 were multicentre studies, while the remaining were single‐centre studies.

There was some variation between the type of DM, albuminuria and CKD stage included in the studies. All studies included T2DM participants, while McMurray 2002 and MESMI 2010 also included participants with T1DM. MEMO 2011 included participants with moderately increased albuminuria or overt proteinuria with a SCr < 180 µmol/L. Fogelfeld 2017 included participants with a documented advanced diabetic nephropathy defined as impaired kidney function (eGFR calculated by the Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation) corresponding to CKD stages 3 to 4 (moderate‐severe, i.e. eGFR > 15 and < 60 mL/min) and presence of proteinuria or albuminuria as follows:

The current presence of severely increased albuminuria (A3)

The current presence of moderately increased albuminuria (A2) and documentation of previous severely increased albuminuria (A3)

The current presence of moderately increased albuminuria (A2) and documentation of diabetic retinopathy or laser therapy

If only moderately increased albuminuria (A2) and A, B, or C criteria are not fulfilled, then renal ultrasound should be done to demonstrate normal‐sized kidneys.

Participants from Kopf 2012 had albuminuria (> 20 mg/L in two separate spot urines) and a documented history of moderate albuminuria (A2) in at least two separate urine samples (UAE > 30 mg/24 hours or > 20 mg/L). In addition to having DM, McMurray 2002 included participants with kidney failure who required KRT with either haemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) for more than 30 months. Steed 2005 included participants with moderately increased albuminuria (A2) (indicated by two or more UACR > 3.0 mg/mmol or 24 hours UAE > 30 mg/24 h) and stage 3 DKD. MESMI 2010 included participants with an eGFR > 15 and < 60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 or DKD (moderately increased UACR > 2.0 mg/mmol for men, > 3.5 mg/mmol for women) and systolic hypertension >130 mm Hg treated with prescribed antihypertensive medication. Finally, Guo 2022 included DKD participants who met the diagnostic criteria of DKD in the uraemic phase.

Interventions and comparisons

C‐DIRECT 2019, MESMI 2010, MEMO 2011, Fogelfeld 2017 and Guo 2022 were described in the text as multifactorial interventions focusing on improving self‐management. In addition to being multifactorial, Fogelfeld 2017 and Guo 2022 used a co‐ordinated medical care approach. Multiple practitioners from various disciplines were present at the participants' appointments and shared the decision‐making for their treatments. For this reason, this comparison was analysed separately. The Fogelfeld 2017 and Guo 2022 comparison was "Multidisciplinary, multifactorial education programmes versus routine care". The C‐DIRECT 2019 intervention delivered education sessions at the bedside while participants underwent HD and were delivered by nurses, typically taking 30 to 60 minutes. The intervention was modelled on the (HED‐SMART) renal programme (Griva 2018). However, its context and delivery were tailored to the needs and context of co‐existing DM and kidney failure, as identified in a previous mixed methods study (Griva 2011; Griva 2015).

In MESMI 2010, the participants received standard care offered to participants with both CKD and DM attending diabetes and nephrology outpatient clinics at the hospital. BP control was the most important aspect of routine care, and treatment was provided depending on the patient’s circumstances and morbidity. Data were collected from the control group at the same time as the intervention group. The multifactorial intervention consisted of the following:

Self‐monitoring of BP, individualised medication review, 20‐minute DVD, and fortnightly motivational interviewing follow‐up telephone contact for 12 weeks (to support BP control and optimal medication self‐management).

Delivered by an intervention nurse with a kidney specialist and doctoral qualifications and trained in motivational interviewing using a checklist and standing script for fidelity purposes.

Participants in the intervention group were taught how to take their BP, which involved sitting every morning after breakfast and taking their medications using their non‐dominant arm with an A&D Medical Pty. Ltd. A digital BP monitor (Model UA‐787, Saitama, Japan), which was supplied for the study.

Participants recorded their daily BP for approximately three months in a specific booklet issued for this purpose. The individualised medication review involved the intervention nurse drawing up a chart of the participant’s prescribed medications, including the drug's generic name, what the medication was for, the dose and when to take it, and targets for which to aim.

The 20‐minute DVD involved an interactive, psychosocial approach to motivating people to take medication, appealing to knowledge, thoughts and feelings underpinned by the modified Health Belief Model.

In MEMO 2011, both treatment groups received a similar routine of care by their own clinician according to local guidelines, consistent with the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on managing individuals with T2DM and DKD. It also provides additional information on managing individuals with T2DM of South Asian ethnicity. Participants in the control group were not seen or treated by the study physician or team and had usual access to education provided as part of standard diabetes care in either primary or secondary care. Like MESMI 2010, the intervention focused on self‐monitoring and followed up on goal setting for medical adherence and lifestyle changes during individual three‐month visits. The participants discussed and recorded lifestyle changes and medication adherence in record books, including general information on DM. It is unclear how or if these differed between the groups.

Kopf 2012 was the only mindfulness‐based stress reduction education intervention study. It was adapted to include practices for complex thoughts and feelings related to DM. It consisted of an eight‐week programme based on body and meditation practices to increase openness, awareness and acceptance of all internal and external experiences. A psychologist and a resident in internal medicine led this.

McMurray 2002 and Steed 2005 also focused on improving self‐management through education, diabetes care monitoring, and management, and both were led face‐to‐face by a diabetes specialist and dietician. To guarantee standardised medical treatment as usual according to diabetes guidelines in both arms, all participants were seen regularly by a physician in the outpatient clinic.

The routine treatment group for McMurray 2002 included diet control, glycaemic control (e.g. insulin injection), antihypertensive drugs, and HD or PD therapy. The diabetes care manager provided the education and care management programme for the participants in the treatment group, which lasted for 12 months.

In Steed 2005, the routine treatment group received no additional education or attention other than completing assessments and receiving 'routine treatment' (not reported in detail).

Excluded studies

Fifty‐nine studies were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were:

Wrong population (42 studies)

Wrong intervention (16 studies)

Study retracted (one study).

Ongoing studies

One ongoing study (NCT03413215) plans to compare additional counselling and education by a diabetes nurse educator and medical social worker over 12 months with standard care.

Studies awaiting classification

Two studies (NCT00782847; Suvamat 2023) have been completed and are awaiting classification, as there are currently no published results.

NCT00782847 compared the DiaNE consultation and support programme given over four weeks with standard care.

Suvamat 2023 compared face‐to‐face group activities with motivational interviews with usual care.

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 summarises the risks of bias for the studies overall, and Figure 3 reports the risks of bias in each individual study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

One study was judged to be a high risk of bias for random sequence generation (McMurray 2002) due to an inadequate randomisation method. The HD participants were randomised to the treatment or control groups according to the date of undergoing HD therapy (patients who underwent HD on Monday, Wednesday and Friday were assigned to the study group; Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday patients were assigned to the control group). Insufficient detail was reported for PD patients, and patients were deemed "numerically randomised". No details of the randomisation sequence were provided.

Five studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias. The studies were described as RCTs and reports randomly assigning participants to one of two groups. However, the methods used to carry out the randomisation process were not described sufficiently (McMurray 2002; Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; MEMO 2011; Steed 2005).

Two studies were judged to have a low risk of bias and provided sufficient details on how the randomisation process was carried out. These included a random assignment to one of the two groups (1:1 ratio) and stratified block randomisation (Kopf 2012; MESMI 2010).

Allocation concealment

Seven studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. Methods used to ensure the allocation of treatment groups were concealed and were not mentioned in six studies (C‐DIRECT 2019; Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; McMurray 2002; MEMO 2011). One study provided insufficient information about allocation concealment (Steed 2005).

One study was judged to have a low risk of bias by providing sufficient details on how the allocation of treatment groups was concealed. Following recruitment, participants were allocated code numbers before enrolment and randomised to the intervention or control group (1:1 ratio) by an off‐site statistician. The people collecting data and assessing outcomes were blinded to group assignment. The identity of all enrolled and randomised participants to receive the intervention was kept in a locked cabinet in the chief researcher’s office (MESMI 2010).

Blinding

Performance bias

The blinding of participants and personnel was assessed separately based on whether the outcomes were subjective or objective. Objective outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by the blinding of participants and personnel compared to subjective outcomes.

For objective outcomes, six studies were judged to have a low risk of bias for blinding participants and personnel (Fogelfeld 2017; Kopf 2012; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010; Steed 2005; McMurray 2002), and two judged unclear (C‐DIRECT 2019; Guo 2022).

For subjective outcomes, all but one study (McMurray 2002) were judged to be at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel (C‐DIRECT 2019; Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; Steed 2005; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010). McMurray 2002 judged a low risk of bias, as cross‐over of participants and study personnel was maintained throughout the study.

Detection bias

The blinding of outcome assessors was assessed separately based on whether the outcomes were subjective or objective. Compared to subjective outcomes, the blinding of outcome assessors is unlikely to influence some objective outcomes.

For objective outcomes, seven studies were judged to have a low risk of bias detection bias for blinding outcome assessors (C‐DIRECT 2019; Kopf 2012; Fogelfeld 2017; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010; Steed 2005; McMurray 2002). Guo 2022 was judged to have an unclear risk of detection bias.

For subjective outcomes, five studies were judged to have a high risk of bias for blinding outcome assessors (Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; McMurray 2002; Steed 2005). C‐DIRECT 2019, MEMO 2011 and MESMI 2010 were judged to have a low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies were judged to have a high risk for attrition bias (Kopf 2012; Steed 2005). There was low to moderate loss‐to‐follow‐up at 12 months. Loss to follow‐up was 2% in the intervention group and 11% in the control group. No reasons were provided for loss‐to‐follow‐up (Kopf 2012). Kopf 2012 also had a higher proportion of patients in the intervention group with a history of myocardial infarction compared to the control group at baseline (22.0% versus 4.26%). The attrition rate for Steed 2005 was high (28%); however, they reported the individuals who did and did not complete follow‐up assessments did not differ significantly at baseline. The self‐management programme's efficacy reported that drop‐outs had significantly higher baseline HbA1c than people who completed the education programme.

Fogelfeld 2017 had an unclear risk of bias for incomplete data. Each group had low to moderate attrition rates: the multifactorial education intervention group (23%) and the usual care control group (12%).

Five studies were judged to have a low risk of bias for incomplete data (C‐DIRECT 2019; Guo 2022; McMurray 2002; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010). McMurray 2002 had no loss to follow‐up. MEMO 2011 and Guo 2022 accounted for all participants from the start to the end of the studies. The attrition rate was low (< 10% in each treatment arm). MESMI 2010 accounted for all participants from the start to the end of the study. Overall, the attrition rates of both arms were low: education (7.7%) and usual care (4.8%). Not all participants had their blood test results included for eGFR and SCr because tests conducted in primary care were not always recorded in the participant’s hospital medical history. According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we recalculated ITT using 'Case Available Analysis' (dichotomous data) or 'Last Observation Carried Forward' (continuous data) (Higgins 2022).

Selective reporting

Six studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias for selective reporting (Fogelfeld 2017; Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; McMurray 2002; MESMI 2010; Steed 2005). Kopf 2012 had some results missing for outcomes recorded at baseline (anxiety and eating disorder components of the PHQ). All planned outcomes (as reported in the methods section) were reported in the results for all eight studies. However, no trial registration or a priori‐published protocols were available. McMurray 2002 had some clinically important outcomes missing, such as the incidence of CV disease.

One study was judged to have a low risk of bias. All outcomes planned in the trial registration and a priori‐published protocol were reported methods for MESMI 2010.

C‐DIRECT 2019 had a high risk of bias because some outcomes in the protocol were not reported in the study publication.

Other potential sources of bias

Fogelfeld 2017 was judged to be at high risk of bias. Conflicts of interest or disclosures were not reported, the study received pharmaceutical funding from Sanofi, and the management of this potential conflict was not made explicit.

C‐DIRECT 2019 had a low risk of bias.

The risk of bias for the remaining six studies was judged to be unclear (Guo 2022; Kopf 2012; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010; McMurray 2002; Steed 2005).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Education programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone

Death

All‐cause death

Education programmes plus routine care compared to routine care alone may make little or no difference to all‐cause death at a mean of nine months follow‐up (Analysis 1.1.1 (4 studies, 424 participants): RR 0.83 95% CI 0.31 to 2.19; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) (C‐DIRECT 2019; Kopf 2012; MEMO 2011; MESMI 2010).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 1: Death

McMurray 2002 (83 participants) reported that the all‐cause death was not different at 12 months, but the specific number of events was not reported. We attempted to contact the authors for details but received no response.

DKD‐related death (total and specific death rates from causes attributable to DKD)

Kopf 2012 (110 participants) reported zero DKD‐related deaths in the intervention and routine care group at 12 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.1.2)

CV disease‐related death

We are uncertain if the education programmes made any difference to CV disease‐related death at a mean of 12 months follow‐up due to very low certainty evidence (Analysis 1.1.3 (2 studies, 289 participants): RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.73; I2 = 0%) (Kopf 2012; MEMO 2011).

HbA1c

HbA1c (%)

C‐DIRECT 2019, Kopf 2012, MEMO 2011, MESMI 2010 and Steed 2005 reported HbA1c (%).

Education programmes, compared to routine care alone, probably decrease HbA1c (%) at a mean of 13.5 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.2 (4 studies, 467 participants): MD ‐0.42%, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.31; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence) (Kopf 2012; MEMO 2011; Steed 2005; C‐DIRECT 2019).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 2: HbA1c [%]

MESMI 2010 (80 participants) reported the median and interquartile range for HbA1c (%). In the education programme plus routine care group, the median HbA1c was 7% at three months, 7.5% at six months, and 7% at nine months follow‐up. For the routine care group, it was 7% at three months, 7% at six months, and 8% at nine months.

McMurray 2002 (83 participants) reported that HbA1c levels declined from 6.9% to 6.2% in the education programmes group, whereas the routine care group results were unchanged at 7% (P < 0.005). They also reported that the reduction in blood glucose and HbA1c levels wasn't associated with increased hypoglycaemia. We attempted to contact the authors for the mean and standard deviation but received no reply.

Attaining a HbA1c ≤ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol)

MEMO 2011 reported that attaining an HbA1c ≤ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) at 18 months may be decreased with routine care, compared to the education programmes (Analysis 1.3 (179 participants): RR 2.43, 95% CI 1.37 to 4.32; low certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 3: Attaining HbA1c < 6.5%

Kidney failure

Kopf 2012 reported the incidence of kidney failure, but the effect is unclear due to few reported events (Analysis 1.4 (110 participants): RR 3.22, 95% CI 0.13 to 77.41) (very low certainty evidence).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 4: Kidney failure

Patient‐orientated measures of knowledge, self‐management, and behavioural changes

Attitude scales

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported a MD in participants' attitude scales for seriousness, treatment effectiveness and personal control in participants who had an education programme plus routine care group compared to routine care at five weeks (end of treatment) and three months follow‐up.

Education programmes compared to routine care may make little or no difference in the attitude toward the seriousness of disease at the end of treatment (Analysis 1.5.1: MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.42) and at the end of follow‐up (Analysis 1.6.1: MD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.46) (low certainty evidence). However, a difference was reported between the groups for the attitude scale for treatment effectiveness at the end of treatment (Analysis 1.5.2: MD 0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.43) and at the end of follow‐up (Analysis 1.6.2: MD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.48) (low certainty evidence).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 5: Patient‐oriented measures: beliefs at the end of treatment (attitude scales)

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 6: Patient‐oriented measures: beliefs at the end of follow‐up (attitude scales)

Education programmes, compared to routine care, may make little or no difference in attitude (personal control) at the end of treatment (Analysis 1.5.3: MD 0.31, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.65). However, personal control at three months follow‐up may be slightly increased with the education programmes compared to routine care (Analysis 1.6.3: MD 0.31 95% CI 0.01 to 0.61) (low certainty evidence).

Knowledge of diabetes

McMurray 2002 (83 participants) reported that after 12 months of follow‐up, education programmes compared to routine care may increase all 11 items related to specific diabetes knowledge in people receiving dialysis (Analysis 1.7) (all low certainty evidence).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 7: Patient‐oriented measures: knowledge of diabetes at the end of treatment

Diagnosis (MD 0.80, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.06)

Monitoring (MD 1.30, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.68)

Hypoglycaemia (MD 1.10, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.39)

Hyperglycaemia (MD 0.50, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.78)

Medication (insulin) (MD 1.40, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.90)

Oral medication (MD 0.70, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.02)

Personal health habits (MD 1.40, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.74)

Diet (MD 0.40, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.73)

Exercise (MD 0.80, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.11)

Chronic complications (MD 0.90, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.21)

Living with diabetes and coping with stress (MD 0.60, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.99).

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported that education programmes plus routine care may improve general knowledge of diabetes at the end of the five‐week intervention (Analysis 1.8.1: MD 15.82, 95% CI 8.39 to 23.25) and after three months of follow‐up (Analysis 1.8.2: MD 14.39, 95% CI 7.45 to 21.33) (low certainty evidence) compared to routine care alone.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 8: Patient‐oriented measures: general knowledge of diabetes

Measures of patient empowerment and self‐efficacy

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported education programmes plus routine care may improve patient total self‐efficacy at the end of the five‐week intervention (Analysis 1.9.1: MD 19.00, 95% CI 12.58 to 25.42), but no difference was reported at the end of the three‐month follow‐up (Analysis 1.10.1: MD 2.97, 95% CI ‐3.43 to 9.37) (low certainty evidence).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 9: Patient‐oriented measures: self‐efficacy at the end of treatment

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 10: Patient‐oriented measures: self‐efficacy at the end of follow‐up

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported education programmes may make little or no difference to self‐efficacy related to HBGM compared to routine care at the end of the five‐week intervention (Analysis 1.9.2: MD 6.96, 95% CI ‐2.87 to 16.79). However, education programmes may increase self‐efficacy related to HBGM after three months of follow‐up Analysis 1.10.2: MD 11.28, 95% CI 1.92 to 20.64) (low certainty evidence).

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported education programmes may make little or no difference to diet after five weeks of education programmes (Analysis 1.9.3: MD 0.74, 95% CI ‐7.51 to 8.99) or after three months of follow‐up compared to routine care (Analysis 1.10.3: MD 3.46, 95% CI ‐4.32 to 11.24) (low certainty evidence).

Steed 2005 (97 participants) reported education programmes may make little or no difference to exercise after five weeks of education programmes (Analysis 1.9.4: MD 3.64, 95% CI ‐7.04 to 14.32) or after three months of follow‐up compared to routine care (Analysis 1.10.4: ME 8.28, 95% CI ‐2.04 to 18.60) (low certainty evidence).

C‐DIRECT 2019 (42 participants) reported there may be little or no difference between education programmes and routine care with the diabetes self‐efficacy scale after three months of follow‐up (Analysis 1.10.5: MD ‐0.57 95% CI ‐1.65 to 0.51) (low certainty evidence).

Patient behavioural changes

McMurray 2002 (83 participants) reported that education programmes compared to routine care may improve self‐management of checking feet (Analysis 1.11.1: RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.63), using lotion (Analysis 1.11.2: RR 9.71, 95% CI 2.45 to 38.56) and wearing appropriate shoes and socks (Analysis 1.11.3: RR 4.39, 95% CI 1.87 to 10.32), after 12 months of treatment. However, there may be little or no difference in HDGM (Analysis 1.11.4: RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.79), carrying carbohydrate (Analysis 1.11.5: RR 1.90, 95% CI 0.93 to 3.87) or eye examination (Analysis 1.11.6: RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.29).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 11: Patient‐oriented measures: self‐management behaviour changes at the end of treatment

Steed 2005 (100 participants) reported there may be beneficial effects of educational programmes on behaviour change at the end of treatment for general diet (Analysis 1.12.1: MD 0.73, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.36), specific diet (Analysis 1.12.2: MD 1.02, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.62), and HBGM (Analysis 1.12.4: MD 2.13, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.08), but not for exercise (Analysis 1.12.3: MD 0.76, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 1.63), foot care (Analysis 1.12.5: MD 0.19, 95% CI ‐0.72 to 1.10) or quitting smoking (Analysis 1.11.7: RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.09 to 7.58).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 12: Patient‐oriented measures: behavioural changes at the end of treatment

The benefits were no longer seen at the end of follow‐up for general diet (Analysis 1.13.1 (2 studies, 142 participants): MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.64; I2 = 0%), specific diet (Analysis 1.13.2 (2 studies, 142 participants): MD 0.46 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.93; I2 = 0%) or HBGM (Analysis 1.13.4 (2 studies, 142 participants): MD 0.62 95% CI ‐1.23 to 2.48; I2 = 76%). There may be little or no difference between the groups at the end of follow‐up for either exercise (Analysis 1.13.3 (2 studies, 142 participants): MD 0.45 95% CI ‐0.28 to 1.18; I2 = 0%) or foot care (Analysis 1.13.5 (2 studies, 142 participants): MD 0.06 95% CI ‐0.70 to 0.83; I2 = 0%) (all low certainty evidence).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 13: Patient‐oriented measures: behavioural changes at the end of follow‐up

Kidney function measures

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported there may be little or no difference in eGFR between the groups at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.14: MD 0.46 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐3.71 to 4.63; low certainty evidence).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 14: Estimated GFR [mL/min/1.73 m2]

Kopf 2012 reported a median eGFR of 85.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 (interquartile range (IQR) 83.0 to 88.7; 52 participants) in the education programme group at one‐year follow‐up. The reported median for the routine care group was 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 83.7 to 90.3; 48 participants) (P = 0.08). At the two‐year follow‐up, a median eGFR of 82.7 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 79.0 to 86.5; 51 participants) was reported in the education programme group, and 84.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 80.0 to 88.7; 43 participants) in the routine care group (P = 0.09).

MESMI 2010 reported at three months follow‐up, the median eGFR was 53 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 35 to 64; 39 participants) in the education programme group and 40 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 27 to 56; 41 participants) in the routine care group. At nine months follow‐up, the median eGFR was 48 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 38 to 76; 39 participants) in the education programme group and 46 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 32 to 72; 41 participants) in the routine care group.

Serum creatinine

Kopf 2012 reported a median SCr of 0.086 mmol/L (IQR 0.080 to 0.092; 47 participants) in the education programme group and 0.084 mmol/L (IQR 0.076 to 0.091; 42 participants) in the routine care group, at three years follow‐up (P = 0.10).

MESMI 2010 reported a median SCr of 0.117 mmol/L (IQR 0.082 to 0.144; 39 participants) in the education programme group and 0.108 mmol/L (IQR 0.089 to 0.171; 41 participants) in the routine care group at three years follow‐up.

Urinary albuminuria‐creatinine ratio

MEMO 2011 (189 participants) reported there may be little or no difference in UACR between the education programme group and routine care at 18 months of follow‐up (Analysis 1.15: MD 0.35 mg/g, 95% CI ‐1.01 to 1.71; low certainty evidence).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 15: Urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio [mg/g]

Kopf 2012 reported a median UACR of 32.2 mg/g (IQR 9.8 to 76.3; 47 participants) in the education programme group and 31.6 mg/g (IQR 12.1 to 83.0; 42 participants) in the routine care group, at three years follow‐up (P = 0.05).

Blood pressure

Systolic blood pressure

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported that SBP may be lower in the education programme group compared to the routine care group at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.16.1: MD ‐11.12 mm Hg, 95% CI ‐16.38 to ‐5.86; low certainty evidence).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 16: Blood pressure [mm Hg]

Diastolic blood pressure

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported that DBP may be lower in the education programme group compared to the routine care group at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.16.2: MD ‐5.43 mm Hg, 95% CI ‐9.12 to ‐1.74; low certainty evidence).

Glycaemic events

Hypoglycaemia

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes compared to routine care alone may make little or no difference to hypoglycaemia at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.17.1: RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.08; low certainty evidence).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 17: Glycaemic events

Serious hypoglycaemia

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes compared to routine care alone may make little or no difference to serious hypoglycaemia at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.17.2: RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.33; low certainty evidence).

McMurray 2002 reported no severe hypoglycaemic episodes in the education programme group, and it is unclear if this extends to the control group. We contacted the authors for the specific numbers, as these were not reported, but received no response.

Non‐fatal cardiovascular events

Kopf 2012 (110 participants) reported education programmes, compared to routine care alone, may make little or no difference to total cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.18.1: RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.45 to 3.49).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 18: Non‐fatal cardiovascular events

Education programmes compared to routine care alone may make little or no difference to stroke (Analysis 1.18.2 (2 studies, 289 participants): RR 4.06, 95% CI 0.45 to 36.26; I2 = 0%) or MI (Analysis 1.18.3 (2 studies, 289 participants): RR 1.18 95% CI 0.41, 3.43; I2 = 0%).

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes, compared to routine care alone, may make little or no difference to heart failure (Analysis 1.18.4: RR 1.98, 95% CI 0.18 to 21.42).

Quality of life

The PHQ was used to assess levels of stress, depression and other psychiatric co‐morbidities, with a lower score indicating less stress. Kopf 2012 (103 participants) reported a lower score with the education programme compared to routine care (Analysis 1.19.1: MD ‐1.70, 95% CI ‐3.09 to ‐0.31; 1 study, 103 participants) at 12 months follow‐up.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 19: Quality of life

C‐DIRECT 2019 (42 participants) reported CKD‐related QoL at three months follow‐up using the KDQoL questionnaire, with higher scores indicating better QoL. C‐DIRECT 2019 reported there may be no differences between the education programme group and the routine care group for the physical composite summary (Analysis 1.19.2: MD 2.13, 95% CI ‐5.14 to 9.40), the mental composite summary (Analysis 1.19.3: MD ‐8.43, 95% CI ‐22.69 to 5.83), the kidney disease composite summary (Analysis 1.19.4: MD ‐4.55, 95% CI ‐12.19 to 3.09), and the general health composite summary (Analysis 1.19.5: MD ‐0.63, 95 % CI‐5.31 to 4.05) (all low certainty evidence).

A questionnaire to evaluate the patient's QoL based on diabetes condition and complications was adapted from the standardised Diabetes Form 2.1 (Hoogwerf 1992). McMurray 2002 reported strong evidence for the improvement in the QoL assessment domains of diabetic symptoms (P < 0.001) and health perception (P < 0.002) in the education programme plus routine care group, compared to routine care. There was no improvement in the categories of social functioning, role limitations and mental health score reported.

Steed 2005 reported that diabetes‐specific QoL, using the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life measure (ADDQoL) (Bradley 1999), and generic QoL using the UK SF‐36 (Jenkinson 1996). Patients who received the education programme only demonstrated improved diabetes‐specific QoL during follow‐up (for three months after the end of treatment) (ANCOVA = 9.33; P < 0.01) compared to the routine care group. UK SF‐36 data on general QoL was not reported.

We contacted the authors of McMurray 2002 and Steed 2005 for the data to include in our meta‐analysis but were unsuccessful.

See Appendix 3 for the assessment tools used.

Lipids

Total cholesterol

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported total cholesterol may be lower in the education programme group at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.20.1: MD ‐0.35 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐0.07; low certainty evidence), compared to the routine care group.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational programmes plus routine care versus routine care alone, Outcome 20: Lipids [mmol/L]

HDL cholesterol

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes, compared to routine care, may make little or no difference to HLD cholesterol at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.20.2: MD ‐0.03 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.03; low certainty evidence).

LDL cholesterol

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported LDL cholesterol may be lower in the education programme group at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.20.3: MD ‐0.40 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.14; 179 participants; low certainty evidence) compared to the routine care group.

Triglycerides

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes, compared to routine care, may make little or no difference to triglycerides at 18 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.20.4: MD 0.07 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.52; low certainty evidence).

Adverse events

Non‐fatal adverse events

MEMO 2011 (179 participants) reported education programmes, compared to routine care, may make little or no difference to non‐fatal adverse events at 13.5 months follow‐up (Analysis 1.21: RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.18; low certainty evidence).