Significance

In most cases of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), the promyelocytic leukemia-retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML/RARα) fusion protein disrupts PML nuclear bodies and forms PML/RARα microspeckles. However, the assembly mechanism and its role in APL development remain unknown. Here, we elucidate how the biophysical process of liquid–liquid phase separation is a critical mechanism driving the assembly of PML/RARα microspeckles. We demonstrate that PML/RARα forms phase-separated condensates, recruiting bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) through the intrinsically disordered region. At the chromatin level, PML/RARα and BRD4 coassembled condensates preferentially target super-enhancer and broad-promoter regions, exerting transactivation functions that contribute to APL malignancy. This work highlights the functional significance of PML/RARα-mediated transcriptional activation by phase separation, providing biophysical insights into the oncogenic activity of PML/RARα.

Keywords: liquid–liquid phase separation, acute promyelocytic leukemia, PML/RARα, BRD4, transcriptional dysregulation

Abstract

In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), the promyelocytic leukemia-retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML/RARα) fusion protein destroys PML nuclear bodies (NBs), leading to the formation of microspeckles. However, our understanding, largely learned from morphological observations, lacks insight into the mechanisms behind PML/RARα-mediated microspeckle formation and its role in APL leukemogenesis. This study presents evidence uncovering liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) as a key mechanism in the formation of PML/RARα-mediated microspeckles. This process is facilitated by the intrinsically disordered region containing a large portion of PML and a smaller segment of RARα. We demonstrate the coassembly of bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) within PML/RARα-mediated condensates, differing from wild-type PML-formed NBs. In the absence of PML/RARα, PML NBs and BRD4 puncta exist as two independent phases, but the presence of PML/RARα disrupts PML NBs and redistributes PML and BRD4 into a distinct phase, forming PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles. Genome-wide profiling reveals a PML/RARα-induced BRD4 redistribution across the genome, with preferential binding to super-enhancers and broad-promoters (SEBPs). Mechanistically, BRD4 is recruited by PML/RARα into nuclear condensates, facilitating BRD4 chromatin binding to exert transcriptional activation essential for APL survival. Perturbing LLPS through chemical inhibition (1, 6-hexanediol) significantly reduces chromatin co-occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4, attenuating their target gene activation. Finally, a series of experimental validations in primary APL patient samples confirm that PML/RARα forms microspeckles through condensates, recruits BRD4 to coassemble condensates, and co-occupies SEBP regions. Our findings elucidate the biophysical, pathological, and transcriptional dynamics of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles, underscoring the importance of BRD4 in mediating transcriptional activation that enables PML/RARα to initiate APL.

Abnormal nuclear morphologies are frequently observed in cancer cells (1) and are implicated in key biological reactions such as gene regulation and DNA damage repair (2, 3). However, the molecular components and functions of altered nuclear structures, particularly their specificity, regulatory functions, and oncogenic activity, remain largely unexplored. In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), the PML/RARα fusion oncoprotein, which is produced by the t(15;17) translocation, has long been observed under the microscope for its ability in destroying promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) nuclear bodies (NBs) and subsequently forming microspeckles (4). Restoration of PML NBs has been reported during the treatment with retinoic acid (RA) or arsenic trioxide (ATO) (5, 6). However, our knowledge of PML/RARα-mediated microspeckles remains at the level of morphological observations, and how these aberrant organelles function in the context of APL remains obscure. The constituent components and cellular functions of these PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles during APL pathophysiology are yet to be elucidated.

Recent advancements in condensate biology have revealed that PML NBs are membraneless condensates (7). Without loss of generality, condensates can evolve to compartmentalize and concentrate intracellular molecules in eukaryotic cells, providing a spatial-temporal regulatory mechanism beyond conventional molecular biology (8). The biophysical process called liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) drives the assembly of membraneless condensates (9, 10). LLPS is governed by multivalent interactions among modular biomacromolecules and/or intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of proteins (11), with the importance demonstrated in driving cellular functions (12, 13) and dysfunction in cancer (13–15). PML NBs have been reported to inhibit proliferation and promote cell apoptosis and/or senescence, establishing PML as a tumor suppressor (16, 17). While the destruction of PML NBs is considered crucial for leukemogenesis (18, 19), PML knockout mice (i.e., disrupting PML NBs) only develop certain types of solid tumors, but not APL or myeloid leukemia (20). This observation suggests that the destruction of PML NBs alone is insufficient for APL leukemogenesis. Based on the findings described above, we propose that PML/RARα microspeckles per se might contribute to APL leukemogenesis through unexplored mechanisms.

The physiological and pathological importance of LLPS in the nucleus is increasingly recognized, mainly due to its involvement in the formation, function, and vulnerability of super-enhancers (SEs) (14, 21). SEs are the clusters of enhancer regulatory elements that act together with bound transcriptional regulators to control the expression of genes important for cell identity and cancer malignancy (22, 23). At SEs, epigenetic regulators such as bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) and many other transcription factors (TFs) have been proposed to form phase-separated condensates (24–26), which compartmentalize and concentrate the transcription apparatus to activate gene expression.

As an initiating factor, PML/RARα binds to chromatin regulatory elements to interfere with normal hematopoietic transcriptional programs and promote the development of APL (27, 28). It has been long viewed that PML/RARα primarily exerts a transcriptional repressive effect on the target genes of master hematopoietic TFs, retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα), and/or PU.1, by recruiting corepressors (18, 29). However, our recent study has added an activation dimension to the transcriptional activity of PML/RARα (30). In addition to the classic transcriptional repression activity, we have demonstrated that PML/RARα also induces the formation of APL-specific SEs, increases the frequency of transcription bursts, and determines the characteristics and fate of APL cells. The activation of gene expression in the nucleus requires specific spatial-temporal conditions, but whether the PML/RARα microspeckles provide biophysical environments and spatial organizations for its transcriptional activity is still elusive.

This study presents compelling evidence demonstrating the crucial role of PML/RARα in establishing LLPS-driven microspeckles, with BRD4 contributing to the functional properties of these structures. Our findings provide pathological and transcriptional insights into the function of PML/RARα and add a biophysical dimension to our understanding of APL leukemogenesis.

Results

Evidence Reveals the Importance of LLPS in the Formation of PML/RARα-Assembled Nuclear Microspeckles.

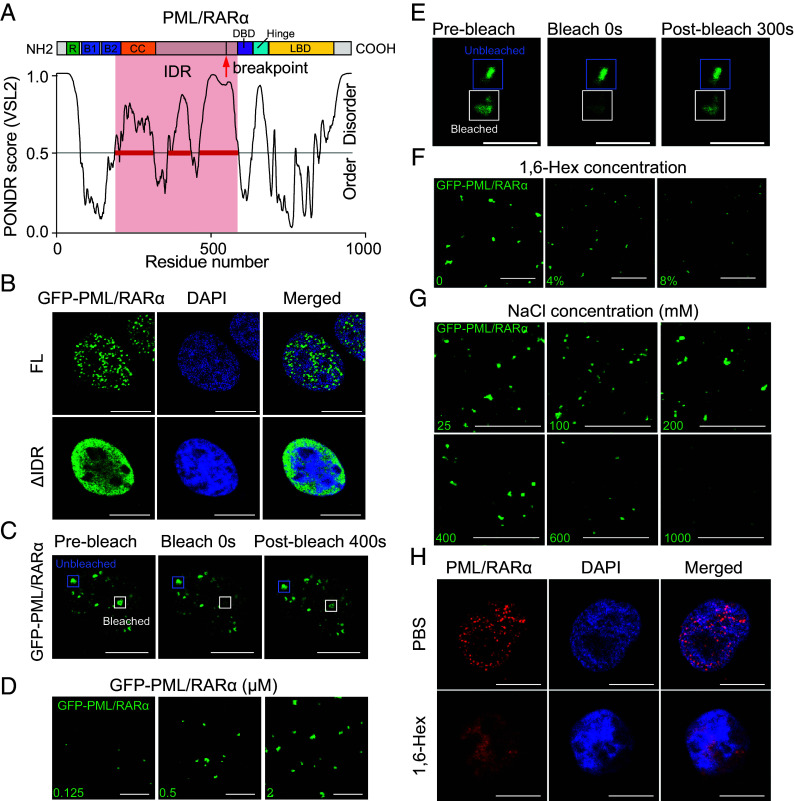

Sequence-based analysis using the PONDR program (31) identified the IDR within PML/RARα that includes a large portion of PML and a smaller segment of RARα (Fig. 1A), suggesting the LLPS-driven formation of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles. Immunofluorescence assays confirmed that overexpressing PML/RARα led to the nuclear microspeckle formation, which was abolished upon deleting the IDR of PML/RARα (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we employed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), a widely used assay for assessing liquidity, to characterize the molecular dynamics of PML/RARα within individual droplets. We demonstrated that PML/RARα condensates exhibited liquid-like properties, with a significant recovery of bleached fluorescence observed within 100 to 400 s (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Moreover, both in cellular extracts and in living cells, our experimental results supported the spontaneous LLPS of PML/RARα. In cellular extracts, droplet formation assays showed that PML/RARα formed micrometer-sized spherical droplets, with the droplet size increasing with the PML/RARα concentration (Fig. 1D). FRAP analysis indicated a moderate exchange of PML/RARα molecules between surrounding solutions and droplets (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), suggesting viscous liquidity of PML/RARα droplets. The LLPS nature was further confirmed by disrupting its hydrophobic interactions using 1,6-hexanediol (1,6-Hex) (25) or its electrostatic interactions using high salt concentrations (Fig. 1 F and G). In living cells, immunofluorescence assays in NB4 cells bearing the t(15;17) translocation showed that the treatment with 1,6-Hex led to the disruption of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles (Fig. 1H). Overall, these observations underscored the significance of LLPS in the formation of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles, which motivated us to further investigate their co-phase-separated partners and cellular functions in the pathogenesis of APL.

Fig. 1.

PML/RARα undergoes LLPS. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the IDR domain of the long-form PML/RARα protein, derived from PML/RARα bcr1 fusion. The exact coordinates of RBCC domains, IDR domain, DBD domain, Hinge domain, and LBD domain were indicated: Ring domain (49 to 104 aa), B1 box (124 to 166 aa), B2 box (183 to 229 aa), coiled-coil domain (230 to 368 aa), IDR domain (205 to 589 aa), DBD domain (590 to 640 aa), Hinge domain (646 to 691 aa), and LBD domain (692 to 911 aa). The breakpoint of PML/RARα was also indicated with a red arrow (552 aa). (B) Representative confocal images illustrating the presence of microspeckles for the full-length (FL) PML/RARα and diffuse distribution for the IDR domain deletion mutant in transfected U2OS cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) Representative images of FRAP assays in living cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Representative images of droplet formation at different protein concentrations. (E) Representative images of FRAP assay in cellular extracts. (Scale bar, 3 μm.) (F) Representative images of droplet formation assays at different 1,6-Hex concentrations. (G) Representative images of droplet formation assays at different salt concentrations. (H) Immunofluorescence images demonstrating the sensitivity of PML/RARα microspeckles to 1,6-Hex in the nucleus. PML/RARα was immunostained using a customized antibody in NB4 cells treated with 8% 1,6-Hex (Lower) or PBS (Upper) for 2 min.

Coassembling with BRD4 Distinguishes PML/RARα-Mediated Microspeckles from PML NBs.

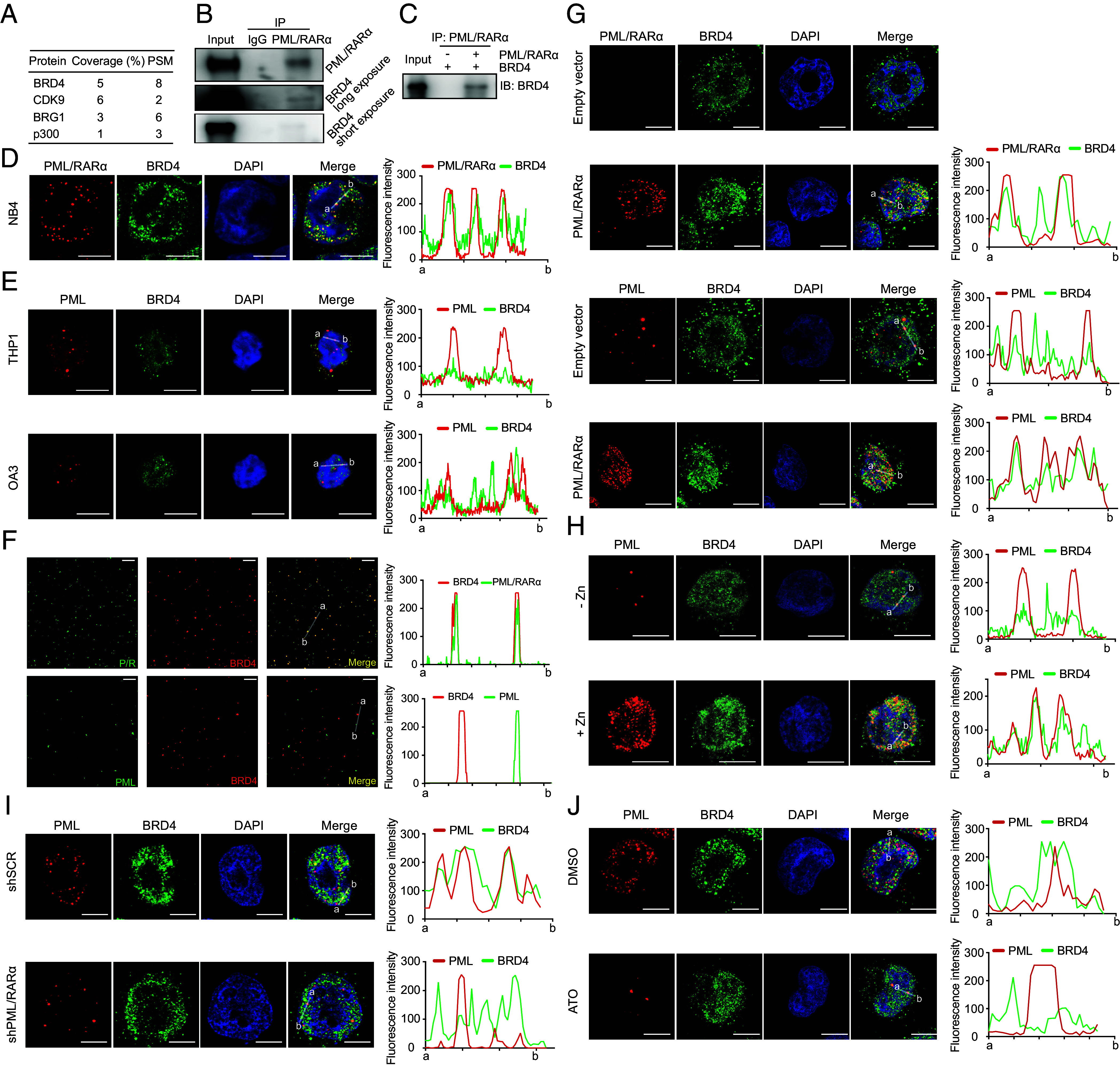

Despite evidence supporting the LLPS-driven formation of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles, their unique properties compared to wild-type PML NBs remained unclear. Immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (IP-MS) revealed a significant enrichment of components associated with phase-separated transcriptional hubs in PML/RARα microspeckles, including BRD4 (25), CDK9 (32), BRG1 (33), and P300 (34) (Fig. 2A). Among them, BRD4, known for regulating SEs and promoting LLPS (21, 25), was of particular interest, especially considering our recent findings of PML/RARα binding to SEs (30, 35). Further investigation into BRD4 through coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed its interaction with both ectopically overexpressed and endogenous PML/RARα in 293T and NB4 cells, respectively (Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

Colocalization with BRD4 is a unique characteristic of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles rather than PML NBs. (A) Top PML/RARα-interacting partners enriched over IgG and associated with phase-separated transcriptional hubs. PSM for the peptide spectrum match and Coverage% for the percentage of the protein sequence covered by the identified peptide in MS. (B) The interaction between endogenous PML/RARα and BRD4 in NB4 cells. (C) The interaction between ectopically expressed PML/RARα and BRD4 in HEK-293T cells. (D) Colocalization of PML/RARα microspeckles with BRD4 in NB4 cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (Right) fluorescence intensity of PML/RARα and BRD4 from a to b. (E) Absence of colocalization between PML NBs and BRD4 in non-APL cell lines THP1 and OCI-AML3. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (F) Overlap of PML/RARα droplets with BRD4 droplets in cellular extracts. In contrast, absence of colocalization between PML droplets and BRD4 droplets. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (G) Ectopic expression of PML/RARα leading to the disruption of PML NBs and redistribution of BRD4 into PML/RARα-assembled condensates in U937 cells. (H) De novo expression of PML/RARα induced by ZnSO4 leading to the disruption of PML NBs and redistribution of BRD4 into microspeckles in PR9 cells. (I and J) Depletion of PML/RARα resulting in the restoration of PML NBs and BRD4 puncta in NB4 cells. PML/RARα downregulation was achieved using shRNA (I) or ATO (J) degradation.

We then explored the spatial colocalization of BRD4 with PML/RARα condensates in the nucleus using coimmunostaining assays with BRD4 antibody and a customized PML/RARα-specific antibody (30, 35), revealing a high degree of spatial overlap between BRD4 and PML/RARα-assembled condensates in NB4 cells (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). These observations prompted an investigation into whether such spatial colocalization is unique to PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles per se or a general feature of PML NBs. Coimmunostaining of wild-type PML and BRD4 in AML cell lines without PML/RARα (THP1 and OCI-AML3) showed no colocalization (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), suggesting a unique interaction within PML/RARα microspeckles. In cellular extracts, droplet partition assays further confirmed the specificity of forming spherical droplets between PML/RARα and BRD4, unlike the mutually exclusive droplets between PML and BRD4 (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Next, we investigated the spatial dynamics of PML, PML/RARα, and BRD4 during APL development and treatment. We performed coimmunostaining assays using specific antibodies targeting PML/RARα and wild-type PML under the presence of PML/RARα or degrading/inhibiting PML/RARα. In the absence of PML/RARα, we observed minimal colocalization between PML NBs and BRD4 puncta (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). However, upon overexpression of PML/RARα, PML NBs were disrupted, and BRD4 became concentrated and localized within PML/RARα-assembled condensates (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Interestingly, we also found that PML was colocalized within PML/RARα-assembled condensates (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). This pattern was consistent across various cell models, including PR9 cells with ZnSO4-induced PML/RARα expression (Fig. 2H) and NB4 cells with endogenous PML/RARα expression (Fig. 2 I and J and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 E and F). In contrast, suppressing PML/RARα expression through shRNA or ATO treatment led to the loss of PML and BRD4 localization within microspeckles, the restoration of PML NBs, and the distribution of BRD4 (Fig. 2 I and J and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 E and F). These results highlight the critical role of PML/RARα in the formation and maintenance of these unique structures.

Targets of PML/RARα and BRD4 Coassembled Condensates Are Characteristic of Both Super-enhancers and Broad-promoters (SEBPs), Crucial for APL Leukemogenesis.

We proceeded to identify genomic regions and their target genes where PML/RARα and BRD4 form coassembled condensates. To achieve this, we performed integrative chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis using a BRD4-specific antibody in NB4 cells, combined with our previously generated PML/RARα ChIP-seq data (30). We identified a total of 3,862 binding sites where PML/RARα and BRD4 cooccupied, corresponding to 2,381 genes (Fig. 3A, SI Appendix, Fig. S3A, and Datasets S1). Motif analysis of these cobound regions revealed significant enrichment for recognition sequences of key master hematopoietic TFs such as PU.1, CEBPE, and RUNX1 (Fig. 3B), which was confirmed using previously reported ChIP-seq data for these TFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). In contrast, we observed that the classical RA response elements (RAREs), such as DR2 and DR5, which are the characteristic DNA binding sites for wild-type RARα, were not enriched in these regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). These findings suggest that PML/RARα and BRD4 colocalize with master TFs involved in hematopoiesis.

Fig. 3.

PML/RARα and BRD4 coassembled condensates tend to occupy on SEs and BPs, targeting genes crucial for APL leukemogenesis. (A) Heatmap showing PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding in 3,862 genomic regions. (B) Enrichment of hematopoietic master TFs motif in PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound regions. (C) Higher binding signals of BRD4 at PML/RARα directly activated genes than PML/RARα directly repressed genes (30). (D) Distribution of PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding sites in NB4 cells. (E) Reduced binding of BRD4 to promoter regions in the absence of PML/RARα. NB4 was PML/RARα positive cell line and K562, OCI-AML3, MOLM-13, MOLM-14, A375, and Jurkat were PML/RARα negative cell lines. (F) Preferential cobinding of PML/RARα and BRD4 to BPs compared to typical promoters (TPs) in NB4 cells, with a fourfold higher likelihood. The bar above depicts the distribution of PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding among promoters, in which yellow represents the peaks with PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding and blue for the peaks without PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding. The bar graph shows the percentages of PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding within BP regions and TP regions. (G) Preferential cobinding of PML/RARα and BRD4 to SEs over fourfold more likely than typical enhancers (TEs) in NB4 cells. (H) GSEA showing the enrichment of BP genes among genes most likely targeted by SEs with PML/RARα and BRD4 cobinding. (I) GSEA showing the tendency of PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound SEBP genes to be essential for the survival of APL cells. Representative genes at the leading edge are labeled. (J) PML/RARα and BRD4 IF with concurrent RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH) demonstrating coassembly of PML/RARα and BRD4 condensates at MYC and GFI1gene loci. (Right) depiction of MYC and GFI1 gene loci, PML/RARα and BRD4 ChIP-seq, and location of RNA-FISH probes.

In addition to co-occupancy with master TFs, we observed a much higher chromatin occupancy of BRD4 at PML/RARα binding sites for directly activated genes than those for directly repressed genes (30) (Fig. 3C), including known PML/RARα-activated target genes, such as GFI1, MYB, MPO, and IKZF1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that genes cobound by PML/RARα and BRD4 were of functional relevance to neutrophil degranulation, myeloid cell differentiation, and regulation of leukocyte proliferation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E).

Next, we examined the genomic distribution of PML/RARα and BRD4 colocalized regions, revealing that the co-occupied peaks were mostly located at promoter regions, introns, and distal intergenic regions (Fig. 3D). Despite BRD4 predominantly binding to enhancers to elevate the transcriptional activity of its target genes (36, 37), our findings suggested a significant presence in the promoter regions when cobound with PML/RARα (Fig. 3D). We thus hypothesized that PML/RARα might induce the redistribution of BRD4 across the genome. To test this hypothesis, we compared the genomic distribution of BRD4 between PML/RARα-positive and PML/RARα-negative cells and found that BRD4 occupancy was more clustered in promoter regions and less prevalent in intronic and distal intergenic regions in PML/RARα-positive cells compared to PML/RARα-negative cells (Fig. 3E). Further analysis of BRD4 ChIP-seq experiments in PML/RARα-degraded cells versus control (Dataset S2) confirmed our finding, with an observed shift of BRD4 binding from promoters to intronic and distal intergenic regions in PML/RARα-depleted cells (Fig. 3E). This provided evidence that PML/RARα influenced the redistribution of BRD4 to promoter regions.

Given the predominant co-occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4 in promoter regions, we further examined their distribution across two types of promoters: BPs and typical promoters (TPs), defined by the length of H3K4me3 domains and indicative of transcriptional elongation rates (38, 39). Interestingly, both PML/RARα and BRD4 exhibited the highest binding signals at BPs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F). Notably, the co-occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4 was approximately fourfold higher at BPs than at TPs (30.03% versus 7.56%; P = 1.10e-7, the two-sided Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that PML/RARα and BRD4 coassembled condensates likely exert their function at BPs.

In parallel, considering the involvement of PML/RARα in SEs and the preferential enrichment of BRD4 at SEs (30, 40), we explored whether PML/RARα and BRD4 worked together to regulate SEs. Integration of PML/RARα, BRD4, and H3K27ac ChIP-seq data in NB4 cells revealed that PML/RARα and BRD4 were over fourfold more likely to co-occupy SEs than typical enhancers (83.11% versus 19.50%; P < 1e-10, the two-sided Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3G), suggesting their concerted action at SEs. Remarkably, we found that a significant number of genes cobound by PML/RARα and BRD4 at SEs also exhibited BPs (n = 151; Fig. 3H and Datasets S3). Recent studies have emphasized the importance of genes with both SEs and BPs in cell identity and tumorigenesis (41–43), and our study demonstrated that most of SEBP genes in NB4 cells were cobound by PML/RARα and BRD4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3G). This implies that PML/RARα and BRD4 assembled condensates target genes with SEBP characteristics.

To assess the functional significance of these target genes, we leveraged a previously published CRISPR-Cas9 screening dataset in NB4 cells (44) for gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), revealing that most of these targets were essential for sustaining leukemic cell survival, including GFI1, IRF2BP2, JUNB, ZBTB7B, IKZF, and MYC (30, 45, 46), as indicated at the leading edge (i.e., the right-most gray region in Fig. 3I). Immunofluorescence combined with concurrent nascent RNA in situ hybridization (RISH) assays further confirmed the spatial association of PML/RARα and BRD4 coassembled condensates with key leukemogenic genes that were regulated by SEs and BPs, such as GFI1 and MYC (Fig. 3J).

PML/RARα Recruits BRD4 into Nuclear Condensates for Enhanced Chromatin Binding of BRD4.

To characterize the role of PML/RARα and BRD4 in the formation of their coassembled condensates, we performed immunofluorescence staining experiments following the perturbation of either PML/RARα or BRD4 in NB4 cells. Knockdown of PML/RARα resulted in the disruption of PML/RARα-assembled condensates and a significant decrease in the size of BRD4 puncta from an average of 0.24 ± 0.02 μm2 to 0.18 ± 0.01 μm2 (Fig. 4A). Conversely, shRNA-mediated knockdown of BRD4 had minimal impact on the integrity of PML/RARα-assembled condensates (Fig. 4A). Similarly, treatment with ATO, known to degrade PML/RARα through the proteasome pathway (27), resulted in the dissolution of PML/RARα-assembled condensates and the subsequent loss of BRD4 incorporation within these condensates (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). Conversely, treatment with JQ1, an inhibitor of the BET family proteins including BRD4, significantly reduced the colocalization of BRD4 and PML/RARα while leaving the integrity of PML/RARα condensates largely unaffected (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). These results indicate that the formation of condensates relies on the presence of PML/RARα, which facilitates the recruitment of BRD4 into the PML/RARα-assembled condensates.

Fig. 4.

Recruitment of BRD4 within PML/RARα-assembled condensates facilitates the chromatin targeting of BRD4. (A) Immunofluorescence of PML/RARα and BRD4 upon PML/RARα or BRD4 knockdown in NB4 cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) Low, analysis were performed on 6 to 10 cells, with ns denoting no significance. (B) Immunofluorescence of FL PML/RARα or ΔIDR-PML/RARα and BRD4 in transiently transfected U2OS cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) Low, analysis performed on 6 to 10 cells. ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Representative images of droplet formation assays of red fluorescent protein tagged BRD4 (RFP-BRD4) at 0.5 μM mixed with FL GFP-PML/RARα or ΔIDR mutant GFP-PML/RARα at 4 μM each. Low, quantification of the area of BRD4 droplets. ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t test). (D) ChIP-seq signal of PML/RARα and BRD4 on their cobound regions in NB4 cells treated with DMSO, ATO, or JQ1. (E) Metaplots showing the average BRD4 (Top) or PML/RARα (Bottom) ChIP-seq signals at PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound regions in NB4 cells treated with DMSO, ATO, or JQ1. (F) IGV tracks displaying the indicated ChIP-seq signals at GFI1 and IKZF1 in NB4 cells. (G) PML/RARα degradation had no influence on the protein levels of BRD4 in NB4 cells.

Next, we found that experimental evidence, both in living cells and in cellular extracts, supported the role of PML/RARα phase separation in concentrating BRD4 within PML/RARα-mediated condensates. First, we cotransfected FL PML/RARα or its IDR-deleted form along with BRD4 in U2OS cells and detected their nucleic localization. We observed that BRD4 aggregated and incorporated into PML/RARα-assembled condensates (Fig. 4B). In contrast, deleting the IDR of PML/RARα disrupted the formation of microspeckles, subsequently abolishing the condensation of BRD4 (Fig. 4B). Consistent with these findings obtained in living cells, droplet partition assays showed that FL PML/RARα could augment BRD4 phase separation, whereas the IDR-deleted (ΔIDR) mutant lost the capacity to condense BRD4 into larger droplets (Fig. 4C). These results support the view that PML/RARα condensates enhance the phase separation of BRD4, promoting its further condensation within PML/RARα microspeckles.

To provide further evidence at the chromatin level, we conducted PML/RARα and BRD4 ChIP-seq assays before and after perturbing either PML/RARα or BRD4 in NB4 cells. Analysis of PML/RARα occupancy across the genome revealed that treatment with ATO led to a substantial reduction in PML/RARα binding to chromatin, as well as a decrease in BRD4 ChIP-seq signal (Fig. 4 D–F, SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D, and Datasets S4). These results indicate that BRD4 binding depends on the chromatin targeting of PML/RARα, with BRD4 recruited to chromatin by PML/RARα. In contrast, analysis of BRD4 occupancy across the genome indicated that treatment with JQ1 significantly reduced the density and width of BRD4 binding peaks, while the release of BRD4 from chromatin had minimal impact on PML/RARα binding (Fig. 4 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 E and F). These findings suggest that PML/RARα binding is independent of BRD4 recruitment to chromatin. To rule out the possibility that reduced BRD4 binding to chromatin was due to decreased BRD4 expression, we observed that ATO treatment did not affect the protein expression of BRD4 (Fig. 4G), consistent with our immunofluorescence findings (Fig. 4A).

Blockage of the Condensate-Mediated Coactivator BRD4 Activity Suppresses PML/RARα-Mediated Transcriptional Activation and Impairs APL Leukemogenesis.

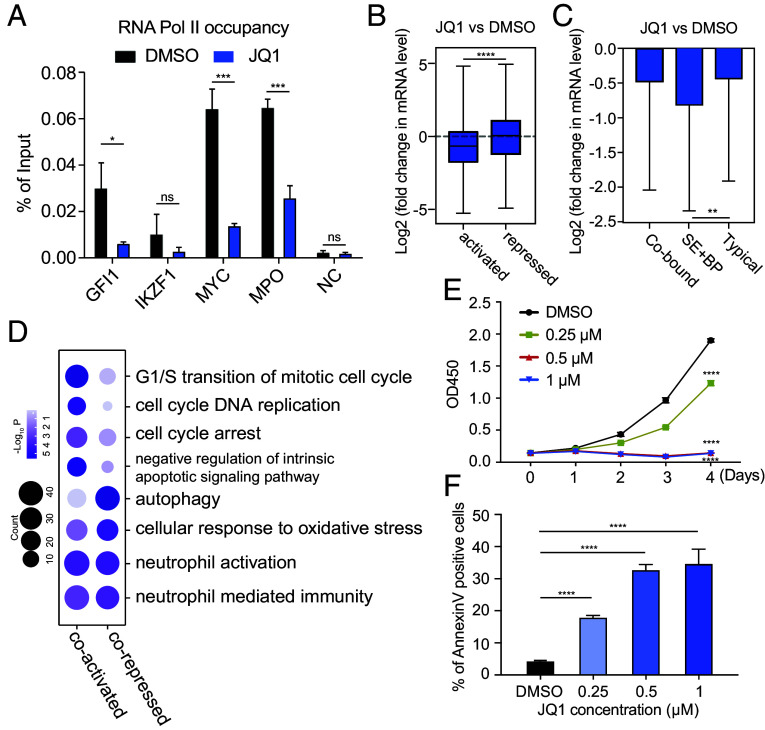

Next, we aimed to explore the function of BRD4 within PML/RARα-assembled condensates. BRD4 is known to regulate transcriptional elongation via phosphorylating RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) (25, 47), leading us to hypothesize that BRD4 is recruited into PML/RARα-assembled condensates to promote RNA pol II dependent transcriptional elongation. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the effect of BRD4 inhibition on the RNA pol II occupancy in the target gene bodies. Inhibiting BRD4 significantly blocked RNA pol II recruitment to the gene bodies of targets regulated by SEBPs (Fig. 5A). To determine the contribution of BRD4 to PML/RARα-mediated transcription, we performed RNA-seq analysis comparing the transcriptional profiles of control and BRD4-inhibited NB4 cells (Datasets S5). Remarkably, treatment with JQ1 led to a significant decrease in the expression of PML/RARα-activated genes (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), while the expression of PML/RARα-repressed genes was minimally affected (Fig. 5B). This transcriptional repression was also observed in genes cobound by PML/RARα and BRD4 (Fig. 5C). More importantly, the transcriptional activity of genes cobound by PML/RARα and BRD4 at SEBP regions was more vulnerable to BRD4 perturbation than that of typical genes (Fig. 5C), consistent with the phase-separating properties of SE condensates (21). These findings provide evidence that BRD4 promotes the transcriptional activation of PML/RARα target genes, especially those regulated by SEBPs.

Fig. 5.

Blockage of BRD4 activity hinders PML/RARα-mediated transcriptional activation and impairs APL leukemogenesis. (A) Decreased RNA pol II binding signals on PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound SE+BP gene bodies upon BRD4 inhibition. NC, negative control. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns no significance. (B) Significant downregulation of PML/RARα directly activated targets (n = 424) upon JQ1 treatment and a lesser impact on PML/RARα directly repressed genes (n = 363). ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Much more reduced mRNA levels of SE+BP genes upon BRD4 suppression compared to TP genes. Typical genes are defined as those nearest to TEs and promoters, and SE+BP genes for those nearest to SEBPs. (D) Functional enrichment analysis revealing significant GO terms among PML/RARα and BRD4 coregulated genes. (E and F) BRD4 inhibition decreased proliferation and induced apoptosis in APL cells. Cell proliferation ability was measured by the CCK8 assay (E). Apoptosis (F) was analyzed on day 2 after DMSO or JQ1 treatment. ****P < 0.0001; ns for no significance.

To determine functional pathways influenced by BRD4, we performed GO enrichment analysis for PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound genes that exhibited differential expression upon JQ1 treatment. The most significantly enriched pathways included those related to the cell cycle G1/S phase transition and negative regulation of intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathways (Fig. 5D), highlighting the involvement of BRD4 in modulating cell proliferation and apoptosis in APL cells. Notably, among the BRD4-activated genes are well-known growth-promoting genes, including MYC, CCND2, E2F8, PRMT1, HOXA10, and MCM7 (45, 48, 49), and apoptosis-regulating genes, such as BCL2, BCL2L2, CD44, ENO1, and MDM2 (50, 51).

We next performed functional experiments to elucidate the biological significance of BRD4 in APL cells. Interestingly, we found that the phenotypic effects of BRD4 inhibition resembled those caused by ATO treatment rather than ATRA treatment. First, we conducted CCK8 assays to evaluate the effects on the cell proliferation, finding that JQ1 treatment dramatically attenuated the growth of NB4 cells (Fig. 5E). Second, we evaluated cell apoptosis using Annexin V and PI staining, finding that BRD4 inhibition led to a significant increase in the percentage of apoptosis in NB4 cells (Fig. 5F and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Third, we found that JQ1 treatment had a limited influence on the expression levels of CD11b and CD14 in NB4 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Additionally, JQ1 treatment did not influence the mRNA expression of neutrophil differentiation markers, such as secondary granule proteins (including LTF, MMP8, ITGB2, and LCN2), which were highly induced by ATRA (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Collectively, these findings highlight the crucial role of BRD4 in PML/RARα-mediated transcriptional activation through phase separation in the context of APL.

Perturbation of LLPS Disrupts PML/RARα and BRD4 Chromatin Occupancy and Attenuates Their Ability to Regulate Target Gene Transcription.

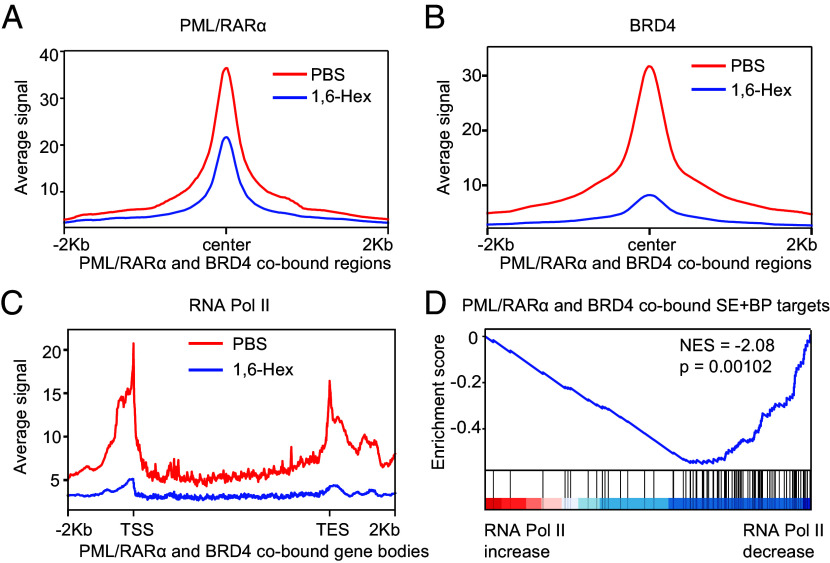

To explore the impact of LLPS on PML/RARα-mediated transcriptional regulation, we carried out perturbation analyses on phase separation. First, we examined the impact of phase separation perturbation using 1,6-Hex on the co-occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4 in NB4 cells. ChIP-seq analysis showed that treatment with 1,6-Hex significantly attenuated the signals of PML/RARα and BRD4 on their cobound regions compared to PBS treatment (Fig. 6 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–D). This indicated that inhibition of phase separation prevented the targeting of PML/RARα and BRD4 to chromatin in APL cells. Second, we compared the chromatin coverage of RNA Pol II before and after the 1,6-Hex treatment. Analysis of ChIP-seq data revealed that the decrease in PML/RARα and BRD4 occupancy on chromatin caused by phase separation perturbation correlated with a reduction of RNA Pol II coverage across target gene bodies (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A, B, and E). When genes were ranked by the extent of RNA Pol II depletion after the 1,6-Hex treatment, PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound SEBP targets showed a high enrichment for genes exhibiting the most significant decrease in RNA Pol II occupancy (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these findings demonstrated the essential role of phase separation in facilitating the chromatin occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4, thereby promoting the transcriptional activation of their target genes.

Fig. 6.

Disrupting LLPS abolishes PML/RARα and BRD4 chromatin coverage and suppresses transcription of their target genes. (A and B) Metaplots illustrating the reduction of average PML/RARα (A) or BRD4 (B) ChIP-seq signals at PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound regions in NB4 cells following treatment with 1,6-Hex. (C) Metaplots demonstrating the attenuation of average RNA Pol II ChIP-seq signals at PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound gene bodies in NB4 cells following 1,6-Hex treatment. TSS, transcription start site. TES, transcription end site. (D) GSEA indicates a high enrichment for PML/RARα and BRD4 cobound SEBP targets among genes exhibiting the most significant decrease in RNA Pol II occupancy after 1,6-Hex treatment. Enrichment score profile is shown, together with the position of SEBP target genes. Genes are ranked by their log2 fold change in RNA Pol II ChIP-seq density within the gene body.

Evidence from Primary APL Patients Confirms the Recruitment of BRD4 by PML/RARα for Coassembly in Condensates at SEBP Regions.

To validate our findings in primary APL patients, we collected bone marrow samples from four newly diagnosed APL patients, two with the long type of PML/RARα and the other two with the short type. First, we observed that both types of PML/RARα formed discrete and numerous microspeckle structures within the nuclei of APL blast cells through immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 7A). Second, further examination of the spatial relationship between PML/RARα and BRD4 revealed a similar overlap ratio for both PML/RARα types with BRD4, averaging 0.55 ± 0.089 (Fig. 7A). This similar capacity was supported by predictions indicating that the short type of PML/RARα retains an IDR, albeit shorter than that in the long type (Fig. 7B). Third, immunofluorescence combined with concurrent nascent RISH assays revealed coassembled PML/RARα and BRD4 condensates at genes located nearby SEBP regions in APL blast cells, regardless of PML/RARα types (Fig. 7C). Fourth, sequential ChIP (re-ChIP) experiments targeting selected SEBP regions demonstrated that PML/RARα indeed formed a protein complex with BRD4, cooccupying on these regulatory regions (Fig. 7D). Taken together, experimental validations from primary APL patients reinforced our findings that PML/RARα recruited BRD4 to coassemble condensates at SEBP regions, elucidating crucial regulatory mechanisms underlying APL pathogenesis.

Fig. 7.

Coassembly of both long- and short-type PML/RARα with BRD4 to form condensates at SEBP regions on APL blast cells. (A) Colocalization of both types of PML/RARα and BRD4 in primary APL blasts assessed by coimmunostaining. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) Low, the overlap ratio of BRD4 with PML/RARα condensates in APL blast cells expressing long-form or short form of PML/RARα, respectively. Analysis was conducted on 10 cells. (B) Schematic diagram illustrating the IDR domain of the short-type PML/RARα. The exact coordinate of the IDR domain was indicated: 205 to 431 aa. The breakpoint of PML/RARα was also indicated with a red arrow (394 aa). (C) IF with concurrent RNA-FISH demonstrating coassembly of both types of PML/RARα with BRD4 forming condensates at MYC and GFI1 gene loci in primary APL blasts. (D) Validation of the co-occupancy of PML/RARα and BRD4 on the same regulatory genomic regions in APL blasts through re-ChIP assays. NC, negative control.

Discussion

In this study, we have provided a comprehensive analysis of PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles, shedding light on their driving forces, constituent components, and regulatory functions. We have demonstrated that PML/RARα forms de novo phase-separated condensates, selectively recruiting the coactivator BRD4 to gene loci with SEBPs. This aberrant recruitment leads to dysregulated transcriptional programs and the malignant phenotypes of APL. Therefore, our study provides valuable biophysical insights into the molecular basis of PML/RARα exerting its oncogenic activity.

Our findings demonstrate that PML/RARα forms de novo microspeckles at ectopic sites primarily through a mechanism involving LLPS. Normally, PML forms macromolecular structures known as PML NBs with tumor-suppressive functions (16), while RARα is reported to be dispersed throughout the nucleus, interacting with DNA at specific response elements (52–54). The fusion of PML with RARα is known to disrupt the normal assembly of PML NBs, leading to an aberrant microspeckled pattern that impairs the tumor-suppressive function of PML NBs and thereby exerts oncogenic effects in a dominant-negative manner (4, 5). Our findings highlight that PML/RARα microspeckles not only achieve oncogenic effects via dominant-negative mechanisms but also confer unique regulatory activities essential for APL pathogenesis. Specifically, our study details how PML/RARα microspeckles accumulate and recruit BRD4 at SEBPs, thereby enhancing the transcriptional efficiency of genes characteristic of APL. Interestingly, this phenomenon is consistent with previous observations where wild-type NPM1 contributes to the formation of membraneless nucleolus (55), while the aberrant cytoplasmic mutant NPM1 forms ectopic transcriptional condensates through phase separation, driving oncogenic transcriptional programs (56). This suggests that there may exist a general mechanism by which mutant proteins acquire oncogenic activities through the formation of ectopic de novo membraneless structures via phase transition, leveraging their inherent phase separation capability.

Our findings highlight the regulatory function of PML/RARα-mediated microspeckles. In PML/RARα-negative cells, PML NBs and BRD4 puncta represent two unrelated phases with different localization and biological functions. More specifically, PML NBs are localized at heterochromatin regions and associated with transcriptional repression (57, 58), while BRD4 puncta preferentially localize at SE regions and are associated with transcriptional activation (25, 26). However, during APL leukemogenesis, PML/RARα can disrupt these two distinct phases, leading to the redistribution and reorganization of protein components to ultimately form a neomorphic phase. Notably, the involvement of BRD4 in PML/RARα-mediated microspeckles confers a new function of transcriptional activation, distinguishing them from PML NBs. In summary, our study reveals a newly defined transactivation function underlying PML/RARα-assembled microspeckles.

Our study also provides unique insights into the physical interaction, spatial colocalization, and chromatin-level interplay between BRD4 and PML/RARα. PML/RARα is capable of redistributing the genome-wide binding profile of BRD4 and recruiting it to promoter regions in addition to its known occupancy at enhancers (36, 47). We and others have previously reported that PML/RARα is oligomerized to facilitate promoter–enhancer looping (30, 58), which may explain the recruitment of BRD4 to both promoters and enhancers. Taken together, we propose a model in which PML/RARα binds to promoters and enhancers to establish a higher-order chromatin conformation and subsequently recruits coactivators such as BRD4 to the transcriptional hub.

Equally interesting in our study is the coenrichment of PML/RARα and BRD4 at gene loci characterized by both SEBPs. These regions exhibit the highest enrichment of PML/RARα and BRD4, indicating the formation of coassembled condensates at these unique regulatory elements. Genes associated with SEBPs generally exhibit higher expression levels than genes regulated by other elements (41). Among PML/RARα-interacting partners, we identified several histone methylation regulators. This suggests a possible mechanism where PML/RARα binds to enhancers and promoters, followed by histone methylation and acetylation enzymes recruitment to these regions, promoting the formation of SEBPs.

However, this study has limitations. First, the expression levels of both nuclear RARα and BRD4 are low in normal hematopoietic cells, including hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), which limits the feasibility of effectively assessing their interaction. Hence, although we demonstrate that BRD4 interacts with PML/RARα and not with normal PML, we were not able to assess whether the BRD4 interaction with PML/RARα i) reflects a neomorphic activity, which we favor, or ii) intensifies a potential function of RARα and BRD4 that is normally undetectable due to the low baseline expression levels. Second, motifs enriched in the PML/RARα and BRD4 co-occupied regions were recognition sequences for master hematopoietic TFs such as PU.1, CEBPE, and RUNX1, rather than the canonical RAREs. This suggests that PML/RARα most likely binds indirectly to these co-occupied regions. Future research is needed to identify factors determining the chromatin binding of the PML/RARα-BRD4 regulatory complex.

Our observations, alongside those from other studies, have demonstrated that fusion oncoproteins containing LLPS-prone IDRs and chromatin binding domains can similarly undergo LLPS and form condensates at nearby target genes (14, 26, 59). This is in stark contrast to the classical model where fusion proteins exert a dominant-negative effect on the transcriptional activity of their wild-type counterparts (18, 60). We thus propose that the fusion of IDR-containing proteins with TFs represents a general mechanism for abnormal activation of oncogenes. Chromatin binding domains determine genomic regions targeted by fusion proteins, while IDR domains promote enrichment and concentration of cofactors for signal amplification.

In conclusion, our study provides biophysical insights into how PML/RARα fusion oncoprotein condensates form and how they contribute to transcriptional activation, a critical characteristic of biomolecular condensates. Our findings provide the rationale for developing targeted therapeutics to disrupt aberrant condensates formed by fusion oncoproteins and potentially counteract their oncogenic effects. Furthermore, the identification of key factors involved in the assembly and disaggregation of condensates by oncogenic fusion proteins opens avenues for developing drugs that target a wide range of IDR-containing molecules with LLPS competency. Such therapeutic strategies hold promise for future interventions in APL as well as in other diseases that are associated with dysregulated phase separation processes.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

The authenticity of NB4, U937, HEK-293T, and U2OS was validated by short tandem repeat (STR) sequencing. Details are available in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

FRAP and Droplet Formation Assay.

FRAP analysis was conducted using a Leica microsystem fitted with a 561 nm laser. Image data were processed by using ImageJ v. 2.1.0. Purified GFP-PML/RARα protein was incubated in the droplet formation buffer and observed under the confocal microscope. Details are available in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

ChIP.

ChIP assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's guideline (53040, Active Motif) with modifications. ChIP-seq libraries were prepared with the NEBNext Ultra II kit (E7645L, New England biolabs (NEB)) and following by high-throughput sequencing at Illumina NovaSeq 6000. See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Immunofluorescence, RT-qPCR, Western Blot, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), and Functional Experiments.

Primers utilized in these assays were presented in Datasets S6 and details were outlined in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Concurrent Nascent RISH Experiments.

RISH was performed using RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent v2 Assay Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA). See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for details.

Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis.

Detailed bioinformatic and statistical processes and methods were available in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (XLSX)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to Prof. Pier Giuseppe Pelicci for the PR9 cell line. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82350710226, 82370178 and 32170663), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1800401), and Young Reserve Talent Program for the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University (dy2yhbrc202002).

Author contributions

Y.Z., J.L., Y.T., H.S., H.F., S.C., Z.C., and K.W. designed research; Y.Z., J.L., Y.L., P.J., W.J., D.W., F.D., S.W., H.F., S.C., Z.C., and K.W. performed research; Y.Z., Y.L., and P.J. analyzed data; and Y.Z., J.L., H.F., S.C., Z.C., and K.W. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: S.C.K., University of California San Francisco; and M.D.M., University Health Network.

Contributor Information

Hai Fang, Email: fh12355@rjh.com.cn.

Saijuan Chen, Email: sjchen@stn.sh.cn.

Zhu Chen, Email: zchen@stn.sh.cn.

Kankan Wang, Email: kankanwang@shsmu.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

High-throughput sequencing data supporting our findings have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), with the accession number GSE232371 (61) for ChIP-seq data and GSE232294 (62) for RNA-seq data.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Mitrea D. M., Mittasch M., Gomes B. F., Klein I. A., Murcko M. A., Modulating biomolecular condensates: A novel approach to drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 21, 841–862 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu C., Kim A., Corbin J. M., Wang G. G., Onco-condensates: Formation, multi-component organization, and biological functions. Trends Cancer 9, 738–751 (2023), 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei M., Huang X., Liao L., Tian Y., Zheng X., SENP1 decreases RNF168 phase separation to promote DNA damage repair and drug resistance in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 83, 2908–2923 (2023), 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyck J. A., et al. , A novel macromolecular structure is a target of the promyelocyte-retinoic acid receptor oncoprotein. Cell 76, 333–343 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weis K., et al. , Retinoic acid regulates aberrant nuclear localization of PML-RAR alpha in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell 76, 345–356 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeanne M., et al. , PML/RARA oxidation and arsenic binding initiate the antileukemia response of As2O3. Cancer Cell 18, 88–98 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banani S. F., et al. , Compositional control of phase-separated cellular bodies. Cell 166, 651–663 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boija A., Klein I. A., Young R. A., Biomolecular condensates and cancer. Cancer Cell 39, 174–192 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeynaems S., et al. , Protein phase separation: A new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 420–435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao Y., Li X., Li P., Lin Y., A brief guideline for studies of phase-separated biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 1307–1318 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergeron-Sandoval L. P., Safaee N., Michnick S. W., Mechanisms and consequences of macromolecular phase separation. Cell 165, 1067–1079 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., et al. , Phase separation of OCT4 controls TAD reorganization to promote cell fate transitions. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1868–1883.e11 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta S., Zhang J., Liquid-liquid phase separation drives cellular function and dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22, 239–252 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn J. H., et al. , Phase separation drives aberrant chromatin looping and cancer development. Nature 595, 591–595 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng Y., et al. , N(6)-Methyladenosine on mRNA facilitates a phase-separated nuclear body that suppresses myeloid leukemic differentiation. Cancer Cell 39, 958–972.e8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y. T., et al. , Ubiquitination of tumor suppressor PML regulates prometastatic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 2982–2997 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lallemand-Breitenbach V., de The H., PML nuclear bodies: From architecture to function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 52, 154–161 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de The H., Pandolfi P. P., Chen Z., Acute promyelocytic leukemia: A paradigm for oncoprotein-targeted cure. Cancer Cell 32, 552–560 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voisset E., et al. , Pml nuclear body disruption cooperates in APL pathogenesis and impairs DNA damage repair pathways in mice. Blood 131, 636–648 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strudwick S., Borden K. L., Finding a role for PML in APL pathogenesis: A critical assessment of potential PML activities. Leukemia 16, 1906–1917 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hnisz D., Shrinivas K., Young R. A., Chakraborty A. K., Sharp P. A., A phase separation model for transcriptional control. Cell 169, 13–23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gartlgruber M., et al. , Super enhancers define regulatory subtypes and cell identity in neuroblastoma. Nat. Cancer 2, 114–128 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam H., et al. , KMT2D deficiency impairs super-enhancers to confer a glycolytic vulnerability in lung cancer. Cancer Cell 37, 599–617.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamudio A. V., et al. , Mediator condensates localize signaling factors to key cell identity genes. Mol. Cell 76, 753–766.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabari B. R., et al. , Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science 361, eaar3958 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X., et al. , Nuclear condensates of YAP fusion proteins alter transcription to drive ependymoma tumourigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 323–336 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de The H., Chen Z., Acute promyelocytic leukaemia: Novel insights into the mechanisms of cure. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 775–783 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villiers W., et al. , Multi-omics and machine learning reveal context-specific gene regulatory activities of PML::RARA in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 14, 724 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang K., et al. , PML/RARalpha targets promoter regions containing PU.1 consensus and RARE half sites in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell 17, 186–197 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan Y., et al. , A PML/RARalpha direct target atlas redefines transcriptional deregulation in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 137, 1503–1516 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun M., et al. , NuMA regulates mitotic spindle assembly, structural dynamics and function via phase separation. Nat. Commun. 12, 7157 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y., et al. , Phase separation of TAZ compartmentalizes the transcription machinery to promote gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 453–464 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y., et al. , Phase transition and remodeling complex assembly are important for SS18-SSX oncogenic activity in synovial sarcomas. Nat. Commun. 13, 2724 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma L., et al. , Co-condensation between transcription factor and coactivator p300 modulates transcriptional bursting kinetics. Mol. Cell 81, 1682–1697.e7 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu S., et al. , Interplay between hypertriglyceridemia and acute promyelocytic leukemia mediated by the cooperation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha with the PML/RAR alpha fusion protein on super-enhancers. Haematologica 107, 2589–2600 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sooraj D., et al. , MED12 and BRD4 cooperate to sustain cancer growth upon loss of mediator kinase. Mol. Cell 82, 123–139.e7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J., Vakoc C. R., The mechanisms behind the therapeutic activity of BET bromodomain inhibition. Mol. Cell 54, 728–736 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benayoun B. A., et al. , H3K4me3 breadth is linked to cell identity and transcriptional consistency. Cell 158, 673–688 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen K., et al. , Broad H3K4me3 is associated with increased transcription elongation and enhancer activity at tumor-suppressor genes. Nat. Genet. 47, 1149–1157 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gryder B. E., et al. , PAX3-FOXO1 establishes myogenic super enhancers and confers BET bromodomain vulnerability. Cancer Discov. 7, 884–899 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quevedo M., et al. , Mediator complex interaction partners organize the transcriptional network that defines neural stem cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 2669 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhar S. S., et al. , MLL4 is required to maintain broad H3K4me3 peaks and super-enhancers at tumor suppressor genes. Mol. Cell 70, 825–841 e826 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki H. I., Young R. A., Sharp P. A., Super-enhancer-mediated RNA processing revealed by integrative microRNA network analysis. Cell 168, 1000–1014.e15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T., et al. , Gene essentiality profiling reveals gene networks and synthetic lethal interactions with oncogenic Ras. Cell 168, 890–903 e815 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pulikkan J. A., et al. , CBFbeta-SMMHC inhibition triggers apoptosis by disrupting MYC chromatin dynamics in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell 174, 172–186.e21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aubrey B. J., et al. , IKAROS and MENIN coordinate therapeutically actionable leukemogenic gene expression in MLL-r acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Cancer 3, 595–613 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donati B., Lorenzini E., Ciarrocchi A., BRD4 and Cancer: Going beyond transcriptional regulation. Mol. Cancer 17, 164 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He X., et al. , PRMT1-mediated FLT3 arginine methylation promotes maintenance of FLT3-ITD(+) acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 134, 548–560 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park S. A., et al. , E2F8 as a novel therapeutic target for lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, djv151 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang E., et al. , Modulation of RNA splicing enhances response to BCL2 inhibition in leukemia. Cancer Cell 41, 164–180.e8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dai J., et al. , Alpha-enolase regulates the malignant phenotype of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells via the AMPK-Akt pathway. Nat. Commun. 9, 3850 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geoffroy M. C., Esnault C., de The H., Retinoids in hematology: A timely revival? Blood 137, 2429–2437 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang H., et al. , Location of NLS-RARalpha protein in NB4 cell and nude mice. Oncol. Lett. 13, 2045–2052 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ying M., et al. , The E3 ubiquitin protein ligase MDM2 dictates all-trans retinoic acid-induced osteoblastic differentiation of osteosarcoma cells by modulating the degradation of RARalpha. Oncogene 35, 4358–4367 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitrea D. M., et al. , Self-interaction of NPM1 modulates multiple mechanisms of liquid-liquid phase separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 842 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X. Q. D., et al. , Mutant NPM1 hijacks transcriptional hubs to maintain pathogenic gene programs in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 13, 724–745 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H., et al. , Sequestration and inhibition of Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 1784–1796 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y., Ma X., Wu W., Chen Z., Meng G., PML nuclear body biogenesis, carcinogenesis, and targeted therapy. Trends Cancer 6, 889–906 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuo L., et al. , Loci-specific phase separation of FET fusion oncoproteins promotes gene transcription. Nat. Commun. 12, 1491 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gelmetti V., et al. , Aberrant recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor-histone deacetylase complex by the acute myeloid leukemia fusion partner ETO. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 7185–7191 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang K. K., et al. , Genome-wide studies identify genes directly regulated by PML_RARα fusion protein and co-activator BRD4. GEO. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE232371. Deposited 12 May 2023.

- 62.Wang K. K., et al. , Genome-wide studies identify genes regulated by co-activator BRD4 in APL cells. GEO. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE232294. Deposited 12 May 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (XLSX)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

High-throughput sequencing data supporting our findings have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), with the accession number GSE232371 (61) for ChIP-seq data and GSE232294 (62) for RNA-seq data.