Abstract

T1 and Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) are evolving as substrates for quantifying the progressive nature of knee osteoarthritis.

Objective

To evaluate the effects of spin lock time combinations on depth-dependent T1 estimation, in adjunct to QSM, and characterize the degree of shared variance in QSM and T1 for the quantitative measurement of articular cartilage.

Design

Twenty healthy participants (10 M/10F, 22.2 ± 3.4 years) underwent bilateral knee MRI using T1 MAPPS sequences with varying TSLs ([0–120] ms), along with a 3D spoiled gradient echo for QSM. Five total TSL combinations were used for T1 computation, and direct depth-based comparison. Depth-wide variance was assessed in comparison to QSM as a basis to assess for depth-specific variation in T1 computations across healthy cartilage.

Results

Longer T1 relaxation times were observed for TSL combinations with higher spin lock times. Depth-specific differences were documented for both QSM and T1, with most change found at ∼60% depth of the cartilage, relative to the surface. Direct squared linear correlation revealed that most T1 TSL combinations can explain over 30% of the variability in QSM, suggesting inherent shared sensitivity to cartilage microstructure.

Conclusions

T1 mapping is subjective to the spin lock time combinations used for computation of relaxation times. When paired with QSM, both similarities and differences in signal sensitivity may be complementary to capture depth-wide changes in articular cartilage.

Keywords: Articular cartilage, T1ρ, QSM, Magnetic resonance imaging, Microstructural integrity, Arthritis

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive joint disease whereby co-localized intra-articular inflammation, subchondral bone remodeling, and loss of articular cartilage can lead to chronic pain, functional limitations, and decreases in quality of life [1]. At the microstructural level, the cartilage thinning process of OA is characterized by depth-wise degeneration of the collagen-proteoglycan matrix [2]. These changes induce alterations of the mechanical and biochemical properties that characterize articular cartilage, subsequently weakening knee joint loading capacity. Unfortunately, the onset of OA is subclinical in nature and lacks quantitative measurement for progression, until loss of the articular cartilage has led to chronic pain and functional limitations. This limited capacity to quantify the degenerative process of OA, especially in early onset stages, has limited the identification of mechanistic underpinnings that could inform best treatment and ultimately preventative strategies.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers the most promising approach for non-invasive evaluation of articular cartilage and monitoring the progression of OA in vivo. [3] Specialized sequences, such as T1 or T2 imaging, can provide indirect measures that estimate underlying tissue composition and potentially identify OA-based cartilage degeneration [4]. For instance, T1 relaxation times have been shown to reflect changes inversely proportional to cartilaginous glycosaminoglycan content, both in vivo and in vitro [5,6], in conjunction with confounding effects from local collagen network properties such as collagen anisotropy and cartilage hydration [7,8]. Increases in T1 relaxation times have been documented in patients with advanced radiographic stages of OA, when compared to patients in early stages of OA, or controls, suggesting that T1 may be sensitive to the degradation of cartilaginous matrix including, changes in proteoglycan content, as well as alterations in collagen structure and cartilage water content [6,[8], [9], [10]]. A lack of correlation between T1 and glycosaminoglycan content has also been reported, emphasizing that such signal is driven my multifactorial components making up the cartilage structure [7,11]. In individuals at high-risk of developing post traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA), such as those who suffer anterior cruciate ligament injury, longitudinal changes in tibiofemoral cartilage T1 relaxation times have also been documented and related to the adoption of joint-protective movement strategies (e.g., underloading of the involved limb during gait) [12], growing the clinical utility of such imaging to understand the clinical trajectory of articular pathology.

Despite efforts toward standardizing T1 imaging for articular cartilage, there remains large variability in the duration of the spin lock time (TSL) combinations used for acquisition [4,13]. Specific to the study of articular cartilage in clinical knee pathologies, differences in T1 relaxation times suggesting higher risk for OA have been documented using TSL combinations ranging between [0–125] ms [4], creating discrepancies on the effects of spin lock time choice toward resulting MR cartilage maps. Furthermore, as noted by Pfeiffer et al. [12], mean estimated T1 values using shorter spin lock time combinations (i.e., up to 40 ms in their work, relative to mean T1 estimates between 40 and 60 ms) may underestimate T1 relaxation, warranting further study of the effects of TSL combination on resulting T1 measurements. This is especially relevant in the context of improving the prospective identification and monitoring of knee OA and PTOA, where T1 is expected to increase with pathology.

Aside from the lack of standardized MRI acquisition parameters, post-processing of T1 imaging generally consists of extracting relaxation times from the whole anatomical cartilage, precluding insight into vertical, depth-specific differences in structure, or content, that may underlie focal depth-wise disease progression and severity [14]. Healthy articular cartilage is comprised of four primary zones that are each characterized by unique cartilaginous tissue and mechanical loading properties [15,16]. For instance, collagen fibers within the radial zone (2nd deepest layer) are aligned perpendicular to the orientation of the underlying bone, allowing for optimal resistance against compressive axial loading forces. The calcified (deepest) and radial zones also contain thicker collagen fibers, along with higher proteoglycan content, which allows for modulation of compressive forces within the deeper cartilaginous tissue [15]. In comparison, the superficial zone contains collagen fibers running primarily parallel to the underlying bone, allowing for resistance to shear stress [15]. Given that structural factors like collagen fiber orientation, or anisotropy, likely influence the estimation of tissue composition, including T1 measurements [10], complementary imaging techniques that are also sensitive to both tissue content and organizational properties of tibiofemoral cartilage may help to better characterize articular microstructural integrity.

In recent years, Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) has emerged as an additional imaging method used to study OA-related structural alterations in articular cartilage. QSM captures local changes in calcification and provides depth-specific estimates of the microstructural cellular arrangement within the collagen fiber network [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. QSM is well-suited for this purpose as both differences in collagen fiber structure [20,22], and changes in the amount of calcification [23], induce specific changes in local susceptibility, which affect the QSM contrast [24]. Clinically, decreases in the predictable variation of local susceptibility across the depth of the tibiofemoral cartilage has been related to OA severity [21,24], suggesting the potential for QSM to provide complementary insight about depth-wise changes in the collagen network microstructure that underlie the degenerative sequalae on articular cartilage, and its correlation to clinical symptoms.

Conceptually, QSM and T1 imaging may provide complementary assessments for quantifying healthy and pathologic knee cartilage, each offering valuable insights and sensitivities to tissue organization and composition. Therefore, the purposes of this study were to 1) evaluate the effects of spin lock time combinations on resulting depth-dependent T1 estimation within healthy articular cartilage of the knee, in adjunct to QSM, and 2) characterize the shared variance of QSM and T1 for the quantitative measurement of articular cartilage. We hypothesized that changing the spin lock time combinations would affect the resulting T1 computation in ways that would highlight the need for standardizing acquisition methodology in T1 mapping of articular cartilage. Given that both T1 and QSM signal contrasts are influenced by T2 relaxation time [25], we further hypothesized some degree of shared variation between both signals throughout the depths of the cartilage.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and ethical approval

Twenty healthy subjects (10 M/10F; 22.2 ± 3.4 years; 78.0 ± 13.0 kg; 176 ± 12 cm) without history of prior traumatic knee injuries or pain (self-reported) underwent sequential unilateral imaging of their right and left knees, respectively (40 total imaging datasets). The present observational study (within-subjects design; level of evidence 3; clinicaltrials.gov: N/A) was approved by the institutional review board at Emory University and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to commencement of any study activities. Data were collected at the Emory Sports Performance and Research Center (SPARC; Flowery Branch, GA, USA).

2.2. Magnetic resonance imaging acquisition

All MRI sequences were acquired on a 3.0 T GE SIGNA Premier scanner (General Electric; Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using an 18-channel T/R knee coil (Quality Electrodynamics, Mayfield Village, OH, USA). QSM data was acquired using a sagittal 3D spoiled gradient echo sequence with fat saturation to reduce the effects of chemical shift between fat and water [21,24]. Global shimming was done prior to the QSM acquisition to homogenize the magnetic field (see Table 1 for specific details regarding the QSM acquisition parameters).

Table 1.

Summary of MR acquisition parameters.

| MRI modality | T1 - SHORT | T1 - EXTENDED | QSM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition type | MAPSS | spoiled | |

| Acquisition | 3D; sagittal | 3D; sagittal | |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 3 | 2 | |

| In slice resolution (mm3) | 0.3125 x 0.3125 | 0.3125 x 0.3125 | |

| TR (ms) | 4.5 | 26 | |

| TE (ms) | [Min, 1–5] | 5.1 | |

| Bandwidth (Hz/pixel) | 244 | 488 | |

| Flip angle (deg.) | 70 | 15 | |

| Acquisition matrix | 192 x 192 | 512 x 512 | |

| Reconstruction matrix | 512 x 512 | 512 x 512 | |

| Spin lock frequency (Hz) | 500 | – | |

| TSL (ms) | [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50] | [0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120] | – |

| Number of slices | 32 | 72 | |

| Parallel imaging factor | – | – | 2 |

| Scan time | 7 min 49 s | 7 min 11 s | |

MAPSS = magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned-k-space SPGR sequence, QSM = quantitative susceptibility mapping, TSL = time of spin lock.

Two sagittal 3D MAPSS (magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned-k-space SPGR sequence) sequences with identical parameters, except for the TSL combination, were acquired to estimate T1 relaxation times [21]. One T1 sequence was acquired using a shorter TSL combination (V-SHORT; TSL = [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50] ms) [12,26]. A second T1 sequence was acquired using extended TSL with longer maximum spin lock time durations (V-EXTENDED; TSL = [0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120] ms). Table 1 summarizes specific acquisition parameters for the MAPSS acquisitions.

2.3. Voxelwise susceptibility mapping

All data manipulations were accomplished in MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc., Version 2022b; MA, USA) using a mixture of modified scripts developed in-house and functions from the FSL toolbox (FMRIB group, FSL, version 6.01; https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/) [27].

Prior to QSM computation, the native magnitude image was aligned to an anatomical template using linear (FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool, FLIRT) and non-linear (FMRIB's Non-Linear Image Registration Tool, FNIRT) transformations [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. Linear and non-linear transformations were inverted and resampled back to native magnitude space allowing for partial volume classification of the bony structures (i.e., femur, fibula, patella, and tibia) and articular cartilages (i.e., femoral condyle, lateral tibial condyle, medial tibial condyle, patellofemoral), which informed manual segmentation in native space (Fig. 1A1). Segmentation was completed using the magnitude map from the QSM acquisition as it provides the best anatomic contrast.

Fig. 1.

Sampled voxelwise QSM and T1computation output within the knee articular cartilage. (A) Voxel-by-voxel Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) of the articular cartilage was derived using the phase and magnitude images, for each knee. Prior to voxelwise QSM computation (2), the magnitude image for each knee was co-aligned with an atlas using a series of linear and non-linear registrations to augment manual segmentation (1) of the bony (black; fibula, femur, patella, tibia) and cartilaginous structures (femoral, red; lateral tibial condyle, green; medial tibial condyle, cyan blue; patellofemoral, yellow). (B–E) Voxel-by-voxel T1 mapping was done in alignment with the magnitude image to allow for co-localized sampling of region-of-interest measurements post pre-processing. A sample matching sagittal slice for each spin lock time (TSL) combination (i.e., T1-short (B), T1-extended (C), T1-extended plus (D), T1-extended minus (E) and T1-chalian-like (F)), is shown on the left-hand side, as well as the resultant voxelwise T1 maps on the right-hand side.

The following steps were done in sequence based on recommendations from the STISuite (https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/∼chunlei.liu/software.html), which consists of MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc., Version 2021a; MA, USA) scripts to compute voxelwise magnetic susceptibility, adapted for the knee by Wei et al. [21,24] Briefly, results from the segmentation were used to create a mask that covers the knee joint while excluding the bone regions (Fig. 1A). The mask was input into STISuite along with the native magnitude and phase images for Laplacian-based phase unwrapping of the GRE phase (Fig. 1A). The use of such mask is specific to data acquired using the 3D GRE sequence with fat saturation, since saturation within the bone regions can introduce error in the estimation of field maps, related to the ill-posed inverse problem associated with QSM computation [24]. The isolated mask thus provides edge information for local field calculation using background phase removal [24] via variable kernel sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data [31]. Voxelwise susceptibility QSM map are then obtained by inputting the local field maps into a two-level STAR (streaking artifacts reduction) algorithm for QSM, as per the original method [19,32], using the mean QSM of masked region within the field of view as reference. [24] The resulting QSM maps were then masked to the articular cartilage (Fig. 1A2).

2.4. Voxelwise T1 computation using different spin lock time combinations

To assess the effects of TSL combination on resulting T1 computation within the articular cartilage, a total of five spin lock time sets were created using the acquired MAPPS echoes. Common alignment across both T1 acquisitions were ensured by linear co-registration of the baseline 0-ms TSL echo from each acquisition (e.g., T1-SHORTTSL = 0 and T1-EXTENDEDTSL = 0) with the matching high-resolution magnitude map from QSM (FLIRT, 6 DOF) (Fig. 1.3). The resultant transformations were then applied to the remaining respective spin lock echoes (TSLV-SHORT = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50] ms; TSLV-EXTENDED = [ 10, 30, 60, 90, 120] ms), allowing for all images to be co-registered within a respective participant's knee.

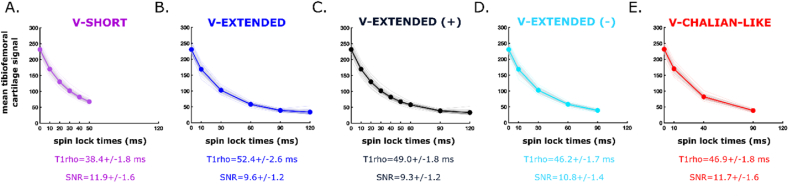

A total of five TSL combinations were set to compute voxelwise T1 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). These included V-SHORT (TSL = [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50] ms), V-EXTENDED (TSL = [0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120 ms]), V-EXTENDED (+) (TSL = [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, 120] ms), V-EXTENDED (−) (TSL = [0, 10, 30, 60, 90] ms) and a V-CHALIAN-LIKE (TSL = [0, 10, 40, 90] ms) [13] V-SHORT served as the experimental version for a shorter TSL combination. V-EXTENDED, V-EXTENDED (+) and V-EXTENDED (−) served as the experimental versions for longer TSL combinations. V-EXTENDED (+) maximized the number of echoes for a potentially better exponential fit (Fig. 2), at the cost of requiring two acquisitions (i.e., longer scan time). V-EXTENDED (−) on the other hand depended on a single acquisition, with longer end spin lock times, and less weighted effects from noise data, which increases at higher TSL (i.e., 120 ms). Lastly, the V-CHALIAN-LIKE combination was closely similar to recommendations from the Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) to standardize T1 mapping, for direct comparison [13]. Echoes that were present from both acquisitions (i.e., 0, 10, 30 ms) were averaged once aligned, prior to voxelwise T1 fitting.

Fig. 2.

Resultant mono-exponential regression forrelaxation time (ms) computation based on the combination of spin lock times selected. (A-E) show the averaged mean articular cartilage signal within the knee per echoes (y) plotted against their respective spin lock times (x; ms) for all 40 acquired datasets (20 participants with bilateral knee dataset acquired sequentially), for each spin lock time combination studied; (A) V-SHORT (spin locks = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 ms), (B) V-EXTENDED (spin locks = 0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120 ms), (C) V-EXTENDED(PLUS) (spin locks = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, 120 ms), (D) V-EXTENDED(MINUS) (spin locks = 0, 10, 30, 60, 90 ms), and (E) V-CHALIAN-LIKE (spin locks = 0, 10, 40, 90 ms). A patch faded over the mean curve represents one standard deviation for each group averages. The individual mono-exponential regressions for each dataset are also plotted in the background. The group averaged whole cartilage and signal to noise quotient is listed under each plot.

The segmented articular cartilage mask was used to compute voxelwise T1 relaxation times (Fig. 1.4) using a standard mono-exponential two parameter equation:

| Eq. (1) |

where, TSL corresponds to the duration of the TSL (ms), represents the signal intensity for the corresponding TSL, S0 is the signal intensity when TSL equals 0, and T1 is the constant relaxation time in the rotating frame (ms) (Fig. 1B–F.5). Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for each TSL echoes was also measured for comparison. SNR was computed as the ratio between the mean signal within the tibiofemoral cartilage over mean of the background. Background signal was extracted using a 10 mm sphere region-of-interest over the field-of-view where no anatomical part of the knee was present, for each participant.

2.5. Distance-based segmentation of tibiofemoral weight-bearing articular cartilage

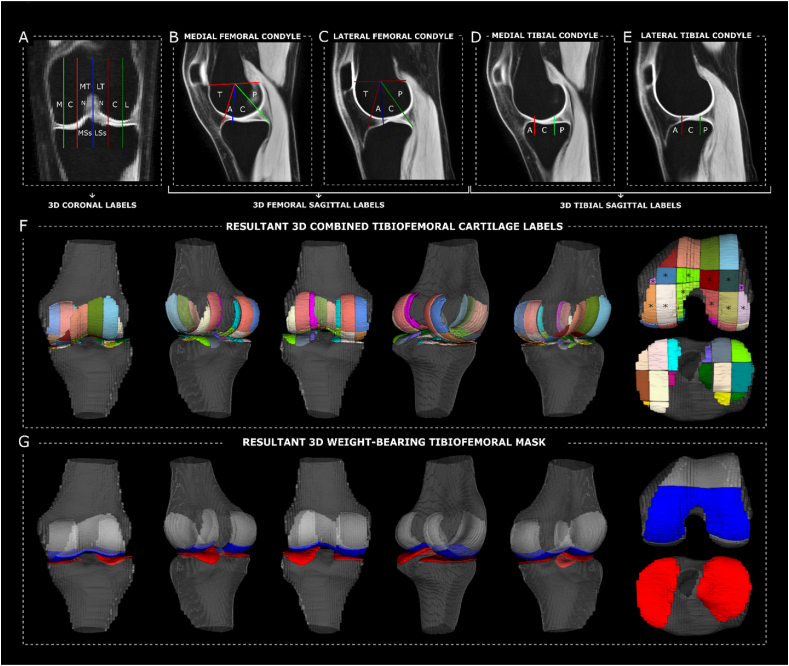

The tibiofemoral weight-bearing cartilage within the knee joint was isolated using a modified systematic anatomical mapping approach described by Moran et al. [33] First, referenced anatomical landmarks (Fig. 3A–E) derived from the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) and the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scoring (WORMS) mapping system were converted to three-dimensional volumes [34]. Those were then combined to create three-dimensional anatomical tibiofemoral labels for cartilage that separate the knee joint into medial/lateral, central and trochlear-notch sub-compartments along the left-right axis of the knee (sagittal plane), and posterior, central, anterior and trochlea sub-compartments along the posterior-anterior axis (coronal plane) (Fig. 3F). From there, articular cartilage regions within the femoral and tibia weight-bearing surfaces could be isolated (Fig. 3F) and masked (Fig. 3G). The above was completed on the template atlas, and then resampled to each participant's native imaging space using the aforementioned inverted warping fields.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional anatomical landmarking for tibiofemoral cartilage parcellation and definition of weight-bearing region-of-interest. Combined anatomical landmarks described in Moran et al., 2022 for the systematic mapping of knee magnetic resonance imaging (A-E) were combined in three dimension to create a three-dimensional anatomical labelling system for articular cartilage of the knee (F). These include coronal (A) and sagittal (B-E) labels from the Whole-Organ MRI Scoring mapping system, as well as the International Cartilage Repair Society method for mapping cartilaginous lesions. The anatomical labels associated with weight-bearing areas of the distal femur (F∗) were combined to mask in weight-bearing articular cartilage overlying the femoral condyles (G, blue). This was combined with the whole tibial cartilage (G, red) to create the resultant three-dimensional tibiofemoral weight bearing region of interest for layer-based analysis. A = anterior; C = central; L = lateral; LSs = lateral subspine; LT = lateral trochlea; M = medial; MSs = medial subspine; MT = medial trochlea; N = notch; P = posterior; T = trochlear.

Depth-based segmentation of the femoral cartilage was done using a modified angular binning approach, as previously described [35,36]. First, a point cloud from the cartilage mask was used to fit circles using a least-square approach along the sagittal slices. This was done to create a cylinder with a resulting two-dimensional centroid that was weighted by all valid coordinates within the femoral cartilage mask, accounting for in-plane rotations due to patient positioning (Fig. 4A and B). From there, each sagittal slice was separated into 360 angular bins by fitting angular rays at 1 increments extending from the centroid to 1.5 times the distance between the centroid and the most anterior proximal point within the cartilage mask, ensuring all valid coordinates were captured (Fig. 4C). The computed distance from the articular cartilage to the cortical edge of the bone was then computed using signed distance between the contained pixels within an angular bin, stepped by 5 (Fig. 4D) [15,16]. The resulting distance-based mask was combined with the weight-bearing mask (Fig. 3G) to assess for depth-wise differences in T1 and QSM (discussed next), within the weight-bearing cartilage region of the knee.

Fig. 4.

Depth-based subject-specific sign-distance segmentation of the articular cartilage. Circles were fit along the sagittal slices of segmented articular cartilage (femur sampled here) using least-square fits (A-B) to establish the three-dimensional centroid (B∗) and most anterior-proximal point (B+), which became the minimum radius of the overall three-dimensional cylinder covering whole cartilaginous structure. From there, linear rays were extended in a circular fashion with increments of 1° (green) to establish equal angular bins (C). For each angular bin, the contained voxels were tagged based on the signed distance function between it and the cortical edge of the bone (D), to approximate the depth within cartilage.

Depth-based segmentation for tibial cartilage was less intensive as the tibia plateau lays relatively flat in the axial plane, unlike the complex three-dimensional anatomical curvature of the femoral condyles. Thus, depth segmentation was done by taking the intersection between the sagittal and coronal planes, for each sagittal slices, and splitting the contained pixels using the same sign-based distance mapping described above, relative to the cortical edge of the bone. Because the tibial cartilage is largely weight-bearing in nature, no further masking was done for data extraction.

2.6. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were completed in MATLAB using the statistical toolbox. First, the average SNR for all TSL combination were compared using a one-way between-subjects analysis of variance followed by post-hoc testing with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Average SNR were computed as the average of TSL SNRs, for each participant, based on the set of TSL combination selected.

Average T1 relaxation times for each TSL combination, in each subject, across both knees, were computed based on the binned distance from the cortex. Prior to averaging, the contained data was filtered for possible outliers using Tukey's method and a G-factor of 1.5 [37]. Measurements from the femur and tibia weightbearing portion were combined in the average computation. The same approach was done to estimate mean QSM at each distance bin. Depth-wise T1 times were compared across TSL combinations using a Kullback-Leibler divergence index to assess for similarities across the datasets, with a value of 0 meaning no perceived difference. The mean signal [38,39] for each distance bin across subjects was also analyzed for all TSL combinations and QSM to compute the inflection point at which the statistical property of the signal curve was most abrupt, as another way to assess change in measurement distribution across depth of the cartilage.

To assess differences in T1 at each depth bin for the varying TSL combinations, separate between-subjects analyses of variances were performed. Follow up, Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc t-tests were used to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05/10). Lastly, the linear correlation coefficient between T1 relaxation times from each TSL combination and QSM were squared to determine the proportion of variance in susceptibility across the cartilage that is predicted by T1, according to TSL choice.

3. Results

Differences in SNR were documented across the TSL combinations for T1 computation (Fig. 2). In general, V-SHORT and V-CHALIAN showed higher averaged SNR compared to both V-EXTENDED and V-EXTENDED (+) (p < 0.0001), as well as V-EXTENDED (−) (p < 0.008), although the two were not statistically different from one another (p = 1.00). Averaged SNR for V-EXTENDED (−) was also higher than both V-EXTENDED and V-EXTENDED (+) (p < 0.0001). V-EXTENDED and V-EXTENDED (+) did not differ from one another (p = 0.9132).

Kullback-Leibler indices for depth-wide distributions of T1 relaxation times showed varying degrees of divergence between the TSL combination with V-SHORT and V-EXTENDED showing the greatest degree of relative entropy (Table 2). Comparisons of V-EXTENDED(+), V-EXTENDED(−) and V-CHALIAN all showed similar distributions (low Kullback-Leibler indices, [0.04–0.2]; Table 2). V-EXTENDED(−) and V-CHALIAN were noted to be most similar with a resulting Kullback-Leibler of 0.04.

Table 2.

Kullback-Leibler divergence index across TSL depth-based T1 distributions.

| V-SHORT | V-EXTENDED | V-EXTENDED (+) | V-EXTENDED (−) | V-CHALIAN-LIKE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V-SHORT | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| V-EXTENDED | 14.8 | 0 | – | – | – |

| V-EXTENDED (+) | 6.2 | 1.9 | 0 | – | – |

| V-EXTENDED (−) | 3.8 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0 | – |

| V-CHALIAN-LIKE | 4.9 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0 |

The include signal from the femur and tibia combined.

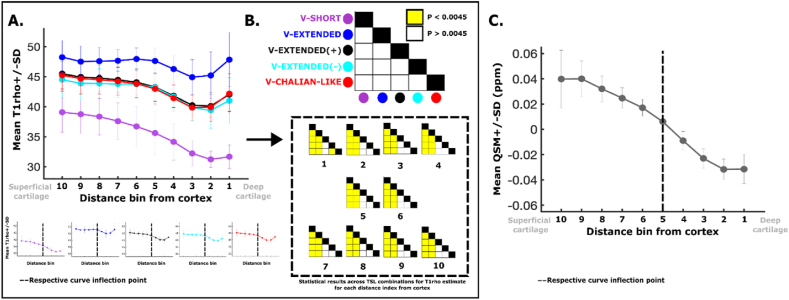

T1 averages across distance bins from the bone cortex showed similar trends across the depth of the cartilage, although clear differences in the magnitude of computed T1 were noted (Fig. 5A). For instance, T1 was higher in the more superficial cartilage with downward trending toward deeper cartilage layers. The inflection point across all TSL combinations, as well as QSM, was found to be at ∼60% of the cartilage depth, from the superficial layer (Fig. 5A, bottom). Except for the deepest bin (voxels closest to cortical bone, 1), depth-specific average T1 times were not statistically different for V-EXTENDED(+), V-EXTENDED(−) and V-CHALIAN (white squares, Fig. 5B). In contrast, T1 relaxation times estimated directly from V-SHORT, and V-EXTENDED were significantly shorter, and longer (p < 0.0045), respectively, across all depth bins, in comparison to V-EXTENDED(+), V-EXTENDED(−) and V-CHALIAN (yellow squares, Fig. 5B). Depth-based susceptibility measurements showed a similar but more definite trend with respect to changes from superficial to deep bins making up the cartilage mask, where values were noted to transition from paramagnetic (positive) to diamagnetic (negative) susceptibility near the inflection point (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Depth-based T1and QSM measurements within the healthy knee cartilage and associated statistical analysis. (A) The mean T1 for each depth bin is plotted for each TSL combination along with its respective group standard deviation. All curves transition from higher distance (ie, superficial cartilage) to low (ie, deep cartilage). Each curve is shown individually below, with its matching labelled inflection point (dotted line). (B) The statistical matrices showing the results from the follow up t-test comparing the resulting T1 across TSL combinations for each bin distance (number), respectively. Yellow represents statistical significance. (C) Mean (with standard deviation) QSM signal across depth bins of the articular cartilage. Inflection point landmarked (dotted line).

Lastly, a ranging degree of squared correlation coefficients were documented between T1 relaxation times and QSM, according to the TSL combination (Fig. 6). Specifically, V-SHORT and V-EXTENDED explained the most (65%), and least (7%), percent variance within QSM measurements, respectively, followed by V-EXTENDED(+) (44%), V-CHALIAN (38%) and V-EXTENDED(−) (32%).

Fig. 6.

Direct linear correlation between T1and QSM. The individual T1 (x) and susceptibility (y) for each subject and bin distance are plotted, along with a linear best fit line for which the squared correlation coefficient is labelled.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of spin lock time combinations on resulting depth-specific T1 relaxation times, in adjunct to co-localized quantitative susceptibility. We further characterized the shared variance in QSM and T1, which provided insight into the complementary yet distinct nature of both T1 and QSM for measuring articular cartilage in vivo. The key findings from this study are threefold: (1) Significant differences in resulting T1 computations were noted according to the chosen TSL combination, with the greatest discrepancy in resulting relaxation times documented between V-SHORT and V-EXTENDED. (2) Decreasing T1 and QSM were observed across the depth of the articular cartilage from superficial to deep with all signals showing changes at ∼60% of the cartilage depth. (3) More than a third of the variance in quantitative susceptibility can be explained by changes in T1 relaxation times (unless using V-EXTENDED) suggesting that the two sequences share inherent mutual sensitivity to microstructural properties of the articular cartilage matrix, as well as underlying differences that may render their combined use fruitful for imaging knee cartilage pathology.

Many iterations of TSL combination have been implemented for the study of cartilage using T1 mapping [4,13], creating limitations for comparison and interpretation of data. In this study, varying combinations of TSL for T1 computations were compared, showing a dependence for the residual relaxation time extracted within healthy cartilage because of the voxelwise fit for T1 exponential decay. This was consistent across the documented average SNR, depth-wide T1 measurements, and residual relationship to QSM, emphasizing the sensitive nature of T1 computation to the choice of spin lock time used for image acquisition. Despite all combinations showing similar trends across the depth of the cartilage, significant differences in the residual T1 measurement were observed between V-SHORT and V-EXTENDED, with the more pronounced discrepancy in terms of TSL combination. The application of shorter maximum TSLs may underestimate T1 relaxation times [12], which is particularly relevant in the context of arthritis progression, where T1 is expected to increase secondary to the degenerative sequalae of the disease [40]. In contrast, minimal gross differences in T1 computation were noted across the majority of the depth bins for TSL combination V-EXTENDED(+), V-EXTENDED(−) and V-CHALIAN, suggesting that some spin lock time combinations may lead to homogenous results, in healthy cartilage.

In this study, both T1 and QSM were evaluated to look for changes across the depth of the cartilage, given their respective sensitivity to changes in microstructural organization and content. A depth-based analysis approach was utilized to leverage sign distance mapping to segment articular cartilage without requiring oversimplified assumptions about superficial and deep layer stratification. Results within healthy knee cartilage showed down-trending T1 relaxation from superficial to deep, with an inflection point at ∼60% of the depth, from the surface. When compared to T1, QSM also showed down trending changes from superficial to deep, transitioning from paramagnetic (positive) to diamagnetic (negative) susceptibility, with an identical inflection point at ∼60%, crossing neutral (QSM ∼ 0). The lower T1 findings in the deeper cartilage is in line with existing literature that suggests a possible inverse relationship between T1 times and proteoglycan content [5,9,[41], [42], [43]], acknowledging that co-localized parameters including collagen orientation, cartilage hydration, and overall matrix organization would also influence the voxelwise signal. To date, proteoglycan content is known to vary across the depth of the cartilage with usual peaks around 50–80% of tissue depth relative to cartilage surface [44].

When correlated against one another, varying degrees of variance predictability was observed according to TSL combinations. Across those, except for V-EXTENDED, over 30% of the variance in QSM could be explained by T1 which suggest some inherent mutual sensitivity to the biological properties that make up the cartilage matrix. This also indicates that some degree of independent effects modulates both the T1 and QSM signals, independently, supporting the notion that the two may be complementary in nature with respect to quantitively characterizing cartilage using MRI. Whether these are differences in sensitivity to the effects of collagen network organization, collagen anisotropy water content, or proteoglycan content, this may suggest that studying pathologic cartilage using both T1 and QSM together may capture microstructural disruptions in articular cartilage that advances the understanding of degenerative OA [44], similar to previous studies using multimodal imaging. In this study of healthy subjects, the V-SHORT acquisition was found to explain the highest variance in QSM (65%) compared to the other tested TSL combinations. This may be due to the constrained limits of the T1 computation bounded by the shorter spin lock times that, in turn, prevent the introduction of higher T1 relaxation times from more superficial areas within the cartilage, which are noted in the extended TSL combinations (Fig. 6B–E, bottom right). As we implement the proposed approach into the study of pathologic cartilage, such discrepancy in the variance explained by T1 against QSM may provide insight about the sensitivity of combined sequences to highlight underlying changes in the cartilage structure, inviting follow-up investigations that explore the effects of TSL combinations in OA using a similar framework. Altogether, combined with the proposed method, this approach may yield opportunities to study gradual changes within superficial cartilage early and monitor transitions to advanced OA features including collagen disorganization [2], as indices for OA severity. As shown by Wei et al. [21], the loss of variability in susceptibility across layers may also be of interest to indicate of degenerative sequela of OA, setting up future studies to consider the addition of QSM to assess changes in cartilage structure [35,36], along with T1 and conventional T2/T2∗ imaging [4,13].

4.1. Limitations

Considering the data presented in this study, several limitations warrant acknowledgment when interpreting these findings for clinical practice, as well as for future study designs. First, the recruited sample was limited to healthy adults with no history of knee injury or pain. We strategically recruited a healthy cohort to evaluate the effects of manipulating spin lock time durations in conjunction with QSM. Future research will aim to assess the effects of such changes in acquisition on pathological cartilage, specifically comparing the different TSL combinations in knees of individuals with differing OA grade severity (i.e., grade 0 vs. grade 5) or at differing risk of PTOA development (i.e., patients with ACLR 1 year vs. 10 years post-surgical reconstruction). The addition of T2 mapping will also improve the proposed imaging protocol, as the use of ultra-short T2∗ mapping can probe cartilage composition within deeper layers, also shown to be susceptible to increase in intensity secondary to tissue degeneration [45,46]. Here, multiple TSL combinations were assessed to evaluate the effects of changing spin lock time on T1. Despite showing that T1 estimates are sensitive to changing TSL, the present study does not provide an optimal combination of spin lock times, as no formal ground truth for the “real” T1 relaxation time was available for direct comparison. This may be addressed in future research using simulation-based methods. Of note, QSM is direction-dependent, like other T2-weighted signals [47], and thus is limited to the assessment of the studied regions within the knee, as those are parallel axially to B0. QSM also requires more advanced computational steps to solve the ill-posed field-to-source-inversion problem [24]. Additionally, a single echo QSM acquisition was implemented to match existing literature studying OA in the knee at 3T. However, in-vitro and in-vivo studies of cartilage have shown that multi-orientation susceptibility tensor imaging is required to properly characterize and distinguish microstructural difference in collagen network structure [18,20,48,49]. The authors also acknowledge that no intra-subject analysis was performed, given existing literature demonstrating adequate test-retest reproducibility for both T1 and QSM [13,21]. Lastly, the analysis in this study was limited to weight-bearing regions within the femoral cartilage given the orientation-dependent nature of QSM [24], as well as T1 [7], which is affected by the changing collagen-related anisotropy in cartilage, in relationship to the magnetic induction field [47,50].

5. Conclusions

The current study provides supporting evidence that T1 mapping is subjective to the choice of spin lock time combination used for acquisition and computation of relaxation times. In the context of studying cartilage degeneration in conditions like OA, or PTOA, where T1 is expected to increase, clinical studies must weigh the benefits of shorter spin lock time durations like higher SNR against the possibility to underestimate T1. Altogether, the current study provides a framework for further investigation aiming to characterize articular cartilage using advanced MRI-based imaging, as well as an exploratory hypothesis related to the complementary relationship between T1 and QSM to characterize knee cartilage health. Specifically, the integration of both T1 and QSM imaging, along with T2 mapping and depth-based analysis, may allow for improving the ways by which degenerative changes in knee articular cartilage tissue composition and organization can be evaluated, respectively. Such approach may in turn provide avenues for earlier identification and classification of OA, as a mean to improve the early detection pathological disease and monitoring of interventions.

Author contributions statement

All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript. Contributions of each author listed after appropriate categories below (using initials).

Substantial contributions to research design, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: AAC, TMZ, DRS, ABS, SMW, SM, LMS, MER, HW, DDB, JAD.

Drafting the paper or revising it critically: AAC, TMZ, DRS, ABS, SMW, MER, LMS, JDL, GDM, JAD.

Approval of the submitted and final versions: AAC, TMZ, DRS, ABS, SMW, MER, LMS, SM, HW, DDB, JDL, GDM, JAD.

Declaration of competing interest

Dr. Myer consults with commercial entities to support commercialization strategies and applications to the US Food and Drug Administration but has no direct financial interest in the products. Dr. Myer's institution receives current and ongoing grant funding from National Institutes of Health/NIAMS Grants U01AR067997, R01 AR070474, R01AR055563, R01AR076153, R01 AR077248 and industry sponsored research funding related to injury prevention and sport performance to his institution. Dr. Myer receives author royalties from Human Kinetics and Wolters Kluwer. Dr. Myer is an inventor of biofeedback technologies (Patent No: US11350854B2, Augmented and Virtual reality for Sport Performance and Injury Prevention Application, Approval Date: July 06, 2022, Software Copyrighted) designed to enhance rehabilitation and prevent injuries and receives licensing royalties. Dr. Myer and Dr. Diekfuss receive inventor-related royalties resultant from biofeedback technologies (Include Health: LIC1907082014-0706). Dr. Diekfuss also receives author royalties from Kendall Hunt Publishing Company. Dr. Mandava is an employee of GE HealthCare.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to thank Maggie Fung (GE Healthcare) for her support with MR imaging sequences. We also thank Jake M. Slaton (Emory University) for his support with recruiting study participants.

Handling Editor: Professor H Madry

Contributor Information

Allen A. Champagne, Email: allen.champagne@duke.edu.

Taylor M. Zuleger, Email: taylor.zuleger@emory.edu.

Daniel R. Smith, Email: daniel.ryan.smith@emory.edu.

Alexis B. Slutsky-Ganesh, Email: alexis.ganesh@emory.edu.

Shayla M. Warren, Email: shayla.warren@emory.edu.

Mario E. Ramirez, Email: mario.e.ramirez@emory.edu.

Lexie M. Sengkhammee, Email: lexie.marie.sengkhammee@emory.edu.

Sagar Mandava, Email: sagar.mandava@gehealthcare.com.

Hongjiang Wei, Email: hongjiang.wei@sjtu.edu.cn.

Davide D. Bardana, Email: davide.bardana@kingstonhsc.ca.

Joseph D. Lamplot, Email: jlamplot@campbellclinic.com.

Gregory D. Myer, Email: greg.myer@emory.edu.

Jed A. Diekfuss, Email: jed.a.diekfuss@emory.edu.

References

- 1.Pinto Barbosa S., et al. Predictors of the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in SF-36 in knee osteoarthritis patients: a multimodal model with moderators and mediators. Cureus. 2022;14(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.27339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saarakkala S., et al. Depth-wise progression of osteoarthritis in human articular cartilage: investigation of composition, structure and biomechanics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link T.M., et al. Establishing compositional MRI of cartilage as a biomarker for clinical practice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(9):1137–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.02.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson H.F., et al. MRI T2 and T1rho relaxation in patients at risk for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Muscoskel. Disord. 2019;20(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duvvuri U., et al. T(1rho) relaxation can assess longitudinal proteoglycan loss from articular cartilage in vitro. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10(11):838–844. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regatte R.R., et al. 3D-T1rho-relaxation mapping of articular cartilage: in vivo assessment of early degenerative changes in symptomatic osteoarthritic subjects. Acad. Radiol. 2004;11(7):741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casula V., et al. Does T1ρ measure proteoglycan concentration in cartilage? J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2024;59(5):1874–1875. doi: 10.1002/jmri.28981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kajabi A.W., et al. Evaluation of articular cartilage with quantitative MRI in an equine model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 2021;39(1):63–73. doi: 10.1002/jor.24780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duvvuri U., et al. T1rho-relaxation in articular cartilage: effects of enzymatic degradation. Magn. Reson. Med. 1997;38(6):863–867. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hänninen N., et al. Orientation anisotropy of quantitative MRI relaxation parameters in ordered tissue. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):9606. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Tiel J., et al. Is T1ρ mapping an alternative to delayed gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging of cartilage in the assessment of sulphated glycosaminoglycan content in human osteoarthritic knees? An in vivo validation study. Radiology. 2016;279(2):523–531. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeiffer S.J., et al. Gait mechanics and T1rho MRI of tibiofemoral cartilage 6 Months after ACL reconstruction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019;51(4):630–639. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalian M., et al. The QIBA profile for MRI-based compositional imaging of knee cartilage. Radiology. 2021;301(2):423–432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021204587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A., et al. High resolution T1rho mapping of in vivo human knee cartilage at 7T. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sophia Fox AJ., et al. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sport Health. 2009;1(6):461–468. doi: 10.1177/1941738109350438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eschweiler J., et al. The biomechanics of cartilage-an overview. Life. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.3390/life11040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimov A.V., et al. Bone quantitative susceptibility mapping using a chemical species-specific R2∗ signal model with ultrashort and conventional echo data. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018;79(1):121–128. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nykänen O., et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of articular cartilage: ex vivo findings at multiple orientations and following different degradation treatments. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018;80(6):2702–2716. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei H., et al. Streaking artifact reduction for quantitative susceptibility mapping of sources with large dynamic range. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(10):1294–1303. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei H., et al. Susceptibility tensor imaging and tractography of collagen fibrils in the articular cartilage. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017;78(5):1683–1690. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei H., et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of articular cartilage in patients with osteoarthritis at 3T. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2019;49(6):1665–1675. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J., et al. Sensitivity of MRI resonance frequency to the orientation of brain tissue microstructure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107(11):5130–5135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910222107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W., et al. Intracranial calcifications and hemorrhages: characterization with quantitative susceptibility mapping. Radiology. 2014;270(2):496–505. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei H., et al. Investigating magnetic susceptibility of human knee joint at 7 Tesla. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017;78(5):1933–1943. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X., et al. Spatial distribution and relationship of T1rho and T2 relaxation times in knee cartilage with osteoarthritis. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009;61(6):1310–1318. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer S.J., et al. Association of jump-landing biomechanics with tibiofemoral articular cartilage composition 12 Months after ACL reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(7) doi: 10.1177/23259671211016424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkinson M., et al. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith S.M., et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkinson M., et al. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson M., et al. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med. Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu B., et al. Whole brain susceptibility mapping using compressed sensing. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012;67(1):137–147. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei H., et al. Joint 2D and 3D phase processing for quantitative susceptibility mapping: application to 2D echo-planar imaging. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(4) doi: 10.1002/nbm.3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran J., et al. A novel MRI mapping technique for evaluating bone bruising patterns associated with noncontact ACL ruptures. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(4) doi: 10.1177/23259671221088936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterfy C.G., et al. Whole-organ magnetic resonance imaging score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(3):177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monu U.D., et al. Cluster analysis of quantitative MRI T(2) and T(1rho) relaxation times of cartilage identifies differences between healthy and ACL-injured individuals at 3T. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(4):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nozaki T., et al. T1rho mapping of entire femoral cartilage using depth- and angle-dependent analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2016;26(6):1952–1962. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3988-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salgado C.M., et al. Secondary Analysis of Electronic Health Records. 2016. Noise versus outliers; pp. 163–183. Cham (CH) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavielle M. Using penalized contrasts for the change-point problem. Signal Process. 2005;85(8):1501–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Killick R., et al. Optimal detection of changepoints with a linear computational cost. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2012;107(500):1590–1598. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y.X., et al. T1rho magnetic resonance: basic physics principles and applications in knee and intervertebral disc imaging. Quant. Imag. Med. Surg. 2015;5(6):858–885. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.12.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regatte R.R., et al. T 1 rho-relaxation mapping of human femoral-tibial cartilage in vivo. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2003;18(3):336–341. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keenan K.E., et al. Prediction of glycosaminoglycan content in human cartilage by age, T1ρ and T2 MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(2):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akella S.V., et al. Proteoglycan-induced changes in T1rho-relaxation of articular cartilage at 4T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001;46(3):419–423. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rautiainen J., et al. Multiparametric MRI assessment of human articular cartilage degeneration: correlation with quantitative histology and mechanical properties. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015;74(1):249–259. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams A., et al. Assessing degeneration of human articular cartilage with ultra-short echo time (UTE) T2∗ mapping. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(4):539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams A.A., et al. MRI UTE-T2∗ shows high incidence of cartilage subsurface matrix changes 2 years after ACL reconstruction. J. Orthop. Res. 2019;37(2):370–377. doi: 10.1002/jor.24110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn T.C., et al. T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology. 2004;232(2):592–598. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nykänen O., et al. T2∗ and quantitative susceptibility mapping in an equine model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis: assessment of mechanical and structural properties of articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(10):1481–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu T., et al. Nonlinear formulation of the magnetic field to source relationship for robust quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013;69(2):467–476. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kantola V., et al. Anisotropy of T(2) and T(1ρ) relaxation time in articular cartilage at 3 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2024;92(3):1177–1188. doi: 10.1002/mrm.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]