Abstract

Over a hundred risk genes underlie risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) but the extent to which they converge on shared downstream targets to increase ASD risk is unknown. To test the hypothesis that cellular context impacts the nature of convergence, here we apply a pooled CRISPR approach to target 29 ASD loss-of-function genes in human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells, glutamatergic neurons, and GABAergic neurons. Two distinct approaches (gene-level and network-level analyses) demonstrate that convergence is greatest in mature glutamatergic neurons. Convergent effects are dynamic, varying in strength, composition, and biological role between cell types, increasing with functional similarity of the ASD genes examined, and driven by cell-type-specific gene co-expression patterns. Stratification of ASD genes yield targeted drug predictions capable of reversing gene-specific convergent signatures in human cells and ASD-related behaviors in zebrafish. Altogether, convergent networks downstream of ASD risk genes represent novel points of individualized therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Human induced pluripotent stem cells, CRISPR screen, neural progenitor cells, glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons, autism spectrum disorder, psychiatric genomics, convergence, precision medicine

INTRODUCTION

The diverse common1 and rare2 genetic variants linked to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show coordinated3 and convergent4–6 effects. In fact, overlapping downstream impacts7 are widely hypothesized to explain how similar clinical phenotypes result from heterogeneous gene mutations4. The 102 highly penetrant risk genes now associated with ASD2,8–13 are typically expressed at high levels in the human cortex and early in development14,15, enriched in excitatory and inhibitory neuronal lineages2,16, co-expressed17–19 in the post-mortem brain, and result in highly interconnected protein-protein interactomes20–22. Knockdown of subsets of ASD genes in human neural progenitor cells (NPCs)23–25, cerebral organoids26–28, and developing mouse29, tadpole30 and zebrafish31 brains reveal overlapping impacts on neurogenesis. Given that excitatory-inhibitory (E:I) imbalance is widely believed to underlie ASD32–34, the extent to which ASD genes subsequently converge in mature neurons to cause functional deficits is largely unknown.

ASD genes are enriched for roles in gene expression regulation (e.g., chromatin regulators and transcription factors) and neuronal communication (e.g., synaptic function)2,8–13. The first chromatin modifier unequivocally associated with ASD was the chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8 (CHD8)35, with temporally specific roles in regulating chromatin compaction, histone modification, gene expression, and splicing36–38, concomitant with effects on neurodevelopmental excitatory and inhibitory trajectories26,39–41. Given the large number of other chromatin remodeling genes now linked to ASD5, and extending upon our recent finding that psychiatric risk genes with shared biological function and brain co-expression result in stronger convergent networks42,43, here we focus on a subset of ASD genes with overlapping function (i.e., chromatin regulators) and test how differences across developmental time points and neural cell types alter the nature of convergence resolved.

Precision medicine seeks to tailor treatments to individual patients44; for example, cancer45 and monogenic disease46 patients with defined molecular subtypes receive targeted treatments. Patient stratification in ASD has proven challenging. Gene classification (e.g., regulatory versus neuronal communication genes) does not predict clinical outcomes such as differential47 or co-occuring2 diagnosis of neurodevelopmental delay or disparities in IQ2. Although subgroups of ASD genes demonstrate opposing effects on telencephalon size in vivo30 or abnormal WNT/βcatenin responses in vitro23, this has not resulted in advances in patient stratification or treatment. The extent to which convergent downstream targets of ASD genes can be manipulated to prevent or ameliorate disorder signatures and phenotypes remains unclear.

Many ASD genes have distinct phenotypes across cell types, regulating proliferation and patterning in neural progenitor cells (SYNGAP148, NRXN149,50, CHD826,39, ARID1B51,52), excitatory transmission by glutamatergic neurons (SYNGAP153, NRXN154, CHD837,55, SHANK356), and inhibitory transmission by GABAergic neurons (NRXN157, CHD855, ARID1B58, SHANK359). Here we test the hypothesis that the cellular context in which ASD genes are evaluated will impact the nature of convergence. We report a pooled CRISPR-knockout (KO) strategy targeting 29 ASD genes (ANK3, ARID1B, ASH1L, ASXL3, BCL11A, CHD2, CHD8, CREBBP, DPYSL2, FOXP2, KMT5B (SUV420H1), KDM5B, KDM6B, KMT2C, MBD5, MED13L, NRXN1, PHF12, PHF21A, POGZ, PPP2R5D, SCN2A, SETD5, SHANK3, SIN3A, SKI, SLC6A1, SMARCC2, WAC) for loss-of-function (LoF) mutations across human neurodevelopment, resolving shared and distinct effects in induced NPCs, glutamatergic neurons, and GABAergic neurons. Two distinct methods (gene-level and network-level) demonstrated the greatest convergence in mature glutamatergic neurons. Overall, the strength and composition of the convergent networks reflected the co-expression patterns of the specific ASD genes considered, varied across cell types, and informed unique aspects of disease biology. Stratification of ASD genes yielded targeted drug predictions capable of reversing gene-specific convergent signatures in human cells and ASD-related behaviors in zebrafish. Altogether, cell-type-specific convergence of ASD genes informed disease mechanisms and prioritized novel therapies that predicted pharmacological responses in vivo. We tested the extent to which convergence informs genetic stratification of cases, asking which subsets of diverse ASD risk genes converge on a smaller number of target genes.

RESULTS

We49,60–62 and others54,56,63–68 demonstrated that iGLUTs (induced via transient overexpression of NGN2) are >95% glutamatergic neurons, robustly express excitatory genes, and show spontaneous excitatory synaptic activity by three-to-four weeks in vitro. Likewise, we57,69,70 and others63,71 reported that iGABA neurons (generated via transient overexpression of ASCL1 and DLX2) are >95% GABAergic neurons, robustly express inhibitory genes, and show spontaneous inhibitory synaptic activity by five-to-six weeks. Neural progenitor cells are rapidly generated by 48-hour induction with NGN272,73. iGLUTs, iGABA and iNPCs express most ASD genes, including all genes prioritized herein60.

A systematic comparison of ASD gene effects across neuronal cell types

From the 102 highly penetrant loss-of-function (LoF) gene mutations associated with ASD (58 gene expression regulation, 24 neuronal communication genes, cytoskeletal, and 10 misc.)2, we used gene ontology and primary literature to identify 21 epigenetic modifiers specifically involved in chromatin organization, rearrangement, and modification (ASH1L, ARID1B, ASXL3, BCL11A, CHD2, CHD8, CREBBP, PPP2R5D, KDM5B, KDM6B, KMT2C, KMT5B (SUV420H1), MBD5, MED13L, PHF12, PHF21A, SETD5, SIN3A, SKI, SMARCC2, WAC), as well as two transcription factors with putative roles as chromatin regulators (FOXP2, POGZ). Gene regulatory transcription factors, general transcription factors, and DNA replication genes were excluded, while three extensively studied synaptic genes (NRXN1, SCN2A, SHANK3) and three under-explored neuronal communication genes (ANK3, DPYSL2, SLC6A1) strongly associated with ASD were added (SI Fig. 1). Of these 29 ASD genes, many also have LoF gene mutations associated with neurodevelopmental delay, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and epilepsy (Fig. 1A, bold as most significant with ASD2) and/or general associations with GWAS for many neuropsychiatric disorders (MAGMA74) (Fig. 1B), indicating a pleotropic effect and consistent with the shared genetic liability across neuropsychiatric disorders75.

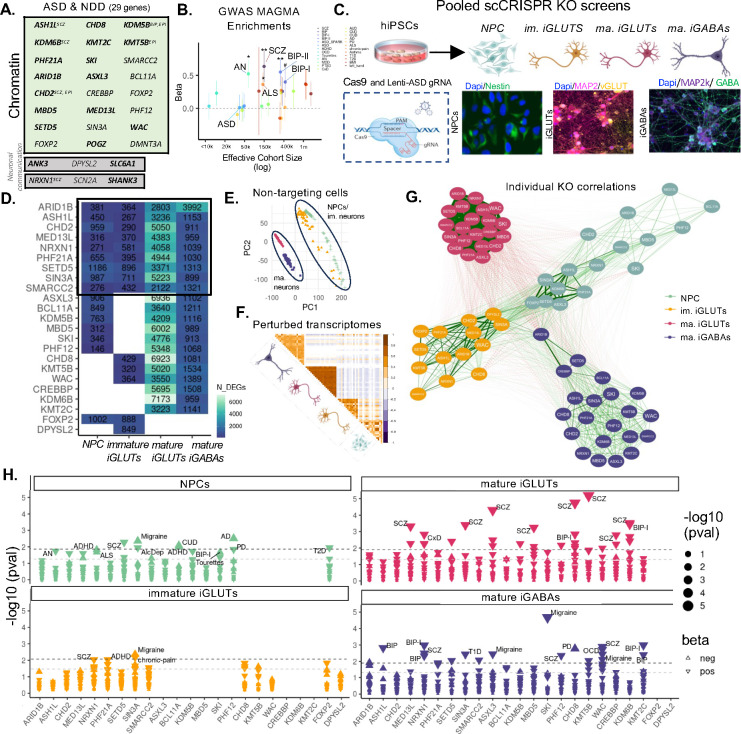

Figure 1. ASD gene knockout (KO) effects have stronger within cell-type correlations than within gene correlations.

(A) List of targeted risk genes associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD). The boldest of the name indicates the strength of ASD correlation and genes are annotated if they are also rare variant targets of SCZ, BIP, and epilepsy (EPI) (B) MAGMA enrichments of targeted ASD genes across psychiatric GWAS. (C) Illustration of hiPSC derived cell-type specific scCRISPR-KO screen. Representative immunofluorescence for cell type markers for NPCs (DAPI/Nestin), mature iGLUTs (DAPI/MAP2/vGLUT), and mature iGABAs (DAPI/MAP2/GABA). (D) Transcriptomic impact of ASD/NDD gene KO across cell-type specific screens represented as the number of nominally significant (p<0.01) differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The degree of KO as indicated by gene expression (logFC) is not correlated with the proportion of significant DEGs (SI Fig. 8F,i–ii). (E) PCA of transcriptomic similarity between scramble controls across cell-types shows clustering based on cellular maturity, with mature iGLUTs and iGABAs and immature iGLUTs and NPCs clustering together respectively. (F) Pearson’s correlation matrix of log2FC across all KOs and cell-types demonstrated greater transcriptomic similarity within cell-types across distinct KOs compared to between cell-types and the same KO. (G) Cross cell-type correlation network diagram across KO perturbations demonstrates greater clustering between NPCs, immature iGLUTs, and surprisingly mature iGABAs, with KO signatures in mature GLUTs the most distinct and most strongly correlated. (H) GWAS disorder enrichments of KO DEGs across cell-types reveal unique KO-by-cell type common variant associations. (#nominal p-value<0.05, *FDR<0.05, **FDR<0.01, *FDR<0.001).

Although regulatory ASD genes showed a bias for prenatal expression, whereas neuronal communicational genes had highest expression in infancy, there were no significant differences in cell type specific expression patterns between either2. Towards resolving whether regulatory genes confer a continuous or distinct period of ASD susceptibility across neurodevelopment, we endeavored to knockout (KO) regulatory ASD genes in donor-matched neural progenitor cells, immature glutamatergic neurons, and mature glutamatergic neurons, contrasting effects across the glutamatergic lineage to effects in mature GABAergic neurons. A pooled CRISPR-KO approach (ECCITE-seq76) combined direct detection of sgRNAs and single-cell RNA sequencing to compare loss-of-function effects across 29 ASD genes. The CRISPR-KO library was generated from pre-validated gRNAs (three to four gRNAs per gene). Sequencing of the gRNA library confirmed the presence of gRNAs targeting 24 genes (ANK3, ARID1B, ASH1L, ASXL3, BCL11A, CHD2, CHD8, DPYSL2, FOXP2, KMT5B (SUV420H1), KDM5B, KDM6B, KMT2C, MBD5, MED13L, NRXN1, PHF12, PHF21A, SCN2A, SETD5, SIN3A, SKI, SMARCC2, WAC), but three were present at lower frequency and less likely to be detected (DPYSL2, FOXP2, SCN2A) (SI Fig. 2). Control hiPSCs were induced to iNPCs (here SNaPs)72, iGLUTs65, and iGABAs71, transduced with lentiviral-Cas9v2 (Addgene #98291) and subsequently with the pooled lentiviral gRNA library three days before harvest at day 7 (iNPC and immature iGLUT), day 21 (iGLUT), and day 36 (iGABA) (Fig. 1C). The gene expression patterns of non-perturbed iNPCs and iNeurons (>30% of all pooled cells) were significantly correlated with fetal brain cells and cortical adult neurons (SI Fig. 9).

Successful ASD gene perturbations were identified for 23 ASD genes (Fig. 1A,B,D): 16 in iNPCs, 15 in immature iGLUT neurons, and 21 in mature iGLUT and iGABA neurons. Nine ASD genes were perturbed in all four cell types (SI Fig. 8F,iii, Fig. 1D). We identified the sgRNA and resolved the transcriptome of 36,016 cells (12,107 iNPC, 3,310 d7 iGLUT, 11,802 d21 iGLUT, and 8,797 d36 iGABA). An average of 474 cells per sgRNA were successfully perturbated by a single gRNA (712 iNPC, 220 d7 iGLUT, 536 d21 iGLUT, 399 d36 iGABA), for a total of 33,389 perturbed cells and 2,627 controls (SI Fig. 3). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs, pFDR<0.05) across multiple individual KOs shared significant gene ontology enrichments in extracellular matrix structural constituents conferring tensile strength in NPCs (downregulated, FDR<0.05), NADH dehydrogenase activity in iGABAs (upregulated, FDR<0.01), and translation initiation factor activity, ATP hydrolysis activity, and microtubule plus-end binding, and others in mature iGLUTs (upregulated, FDR<0.05) – notably, mature iGLUT and iGABA neurons had the greatest number of shared enrichments across individual KOs, suggesting that diverse ASD genes indeed impacted similar neural processes and pathways, but that these impacts were cell-type and developmentally specific (SI Fig. 10, SI Data 1).

Across individual ASD genes, KO typically resulted in the greatest overall transcriptomic impact in mature iGLUTs, which typically also showed the largest number of DEGs (p<0.05), an effect that was not driven by differences in the extent of perturbation of the ASD gene between cell types (Fig. 1D, SI Fig. 8Fi–ii). Moreover, the transcriptomic effects of individual ASD gene KOs cluster by cell type, with the strongest correlations between distinct ASD KOs in mature iGLUTs and the weakest between ASD KOs in iNPCs (Fig. 1E). ASD KO transcriptomic signatures in mature iGLUTs were more distinct, least correlated with other cell types, and most highly correlated with each other (Fig. 1G). The transcriptomic effects of ASD genes within each cell type revealed unique disorder enrichments. Whereas transcriptomic effects of ASD KO in iNPCs and immature iGLUTs resulted in limited overlap with psychiatric GWAS, many ASD KOs in mature iGLUTs (13 of 21) resulted in significant GWAS associations, overwhelmingly to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Fig. 1H). Such clear associations between rare and highly penetrant gene mutations with more common and small effect GWAS targets are widely speculated to exist75,77,78, but supported by only limited evidence to date.

ASD gene knockouts result in cell-type-specific convergent genes and networks.

“Convergent genes” are the common DEGs with significant and shared direction of effect across all ASD gene perturbations (FDR adjusted pmeta<0.05, Cochran’s heterogeneity Q-test pHet > 0.05), as we previously described for the perturbation of schizophrenia GWAS target genes42,43 (Fig. 2A). Individual ASD KO effects rarely converged between iNPCs, iGLUTs, and iGABAs. In fact, frequently the only significant gene (FDR p<0.05) with concordant dysregulation between cell types was the targeted ASD gene itself (SI Fig. 11). The cell type specific nature of KO effects has rarely been tested systematically but given that the ASD epigenetic modifiers tested were expressed in all cell types, this lack of overlap might be considered unexpected. Moreover, the unique cross-cell-type convergent gene list generated by each ASD KO showed distinct enrichments for psychiatric disorder GWAS risk genes (SI Fig. 11).

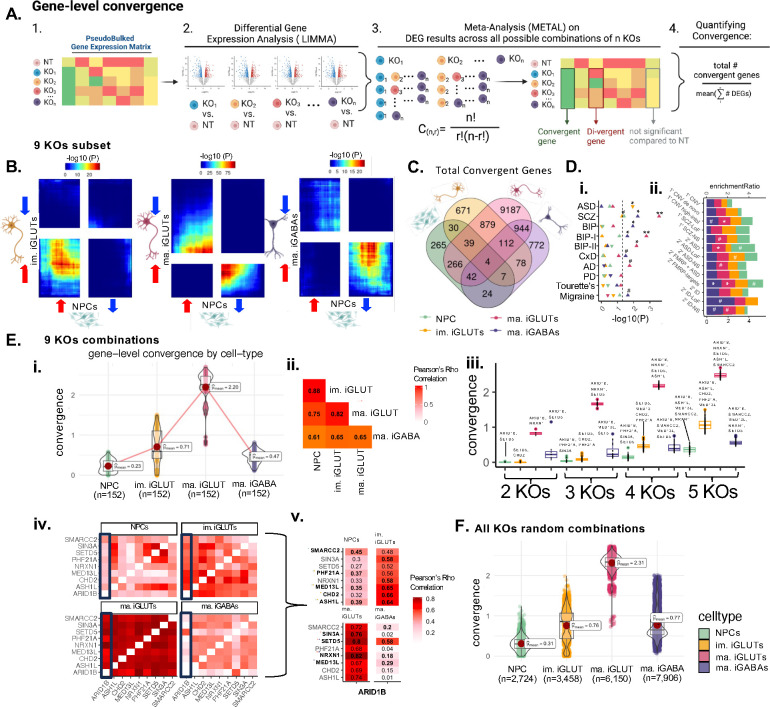

Figure 2. Cell-type-specific gene-level convergence resulting from ASD LoF genes is greatest in mature glutamatergic neurons.

(A) Schematic explaining cross-KO cell-type specific convergence at the individual gene level using differential gene expression meta-analysis. (B) Convergence across 9 ASD gene KO perturbations is largely unique to a given neuronal cell type. Rank-rank hypergeometric (RRHO) test exploring correlation of convergent genes shared across 9 KO perturbations (RRHO score = −log10*direction of effect) between cell-types. The top right quadrant represents up-regulated genes (meta-analysis z-score >0) for the y-axis and x-axis cell-type. The bottom left quadrant represents down-regulated convergent genes (meta-analysis z-score <0) for the y-axis and x-axis cell-type. Significance is represented by color with red regions representing significantly convergent gene expression. (C) Venn diagram representing the absolute overlap (regardless of direction of dysregulation) of cell-type specific convergent genes shared across 9 KOs. (D) (i) Cell-type specific convergence across these 9 KOs is uniquely enriched for neuropsychiatric GWAS-risk associated genes by, ASD common variants only enriched in immature iGLUT convergence (direction of triangle represents beta direction and significance annotation FDRs from two-sided enrichment testing with MAGMA). (ii) ORA of cross-KO cell-type specific convergence and rare variant target genes related to SCZ, ASD, and ID. (#unadjusted p-value=<0.05, *FDR<=0.05, **FDR<0.01, ***FDR<0.001) (E) (i) Across all combinations of 2–5 genes across 9 KOs, the average magnitude of convergence was highest in iGLUTs. (ii) The magnitude of convergence between the same KOs tested in different cells was highly correlated – with the strongest relationship between NPCs, immature, and mature iGLUTs. (iii) Despite strong significant correlation between convergence degree, the top-most convergent KO combinations were unique to each cell-type. (iv) Gene-level convergence based on significant DEGs often corresponds with the cell-type specific strength of correlation between KO effects on the transcriptomic – with the strongest correlations in mature iGLUTs. (F) Expanding the convergence analysis across random subsets of 2–5 genes across 16,14, 21, and 21 KOs for NPCs, immature iGLUTs, mature iGLUTs, and mature iGABAs respectively, the average magnitude of convergence was still highest in iGLUTs.

There were much greater shared effects observed between distinct ASD genes within the same cell type, than for the same ASD gene between cell types, with substantial convergent gene expression observed between different ASD gene KOs within the same cell type. Convergent genes downstream of the nine ASD genes with KO effects resolved across all four cell types were most similar between iNPCs and immature iGLUTs, particularly amongst up-regulated convergent genes, and least similar between iNPCs and mature iGLUTs or iGABAs (weighted correlations, Fig. 2B). Specifically, for these nine ASD KOs, we report 670, 1820, 11473, and 1983 significantly convergent genes in iNPCs, immature iGLUTs, mature iGLUTs, and mature iGABAs, respectively (FDR meta p-value<=0.05), with only four convergent genes overlapping across all cell types (Fig. 2C), and unique pathway enrichments by cell type (SI Fig. 12–13, SI Data 1). In terms of absolute number of convergent genes, the extent of convergence varied by cell type, with the largest number of convergent genes evident in the mature iGLUTs and iGABAs (Fig. 2C). Whereas convergent targets of immature iGLUTs were significantly (FDR <0.05) enriched for the gene targets of ASD GWAS loci (MAGMA74), the convergent targets of mature iGLUTs (FDR <0.01) and iGABAs (FDR <0.05) were most enriched for schizophrenia and bipolar GWAS (Fig. 2Di). The convergent targets of iGLUTs were most enriched for rare variant risk genes associated with ASD and schizophrenia (FDR <0.05, FDR<0.08) (Fig. 2D,ii). Across all possible combinations of these nine ASD genes (combinations of 2–5 genes across all nine KOs equaling 152 unique combinations), the average strength of convergence (measured at the ratio of convergent genes to the average number of DEGs in a set, Fig. 2A,4) was highest in iGLUTs (Fig. 2E,i), but highly correlated between neural cell types, particularly between iNPCs, immature, and mature iGLUTs (Fig. 2E,ii). Top convergent sets (Fig. 2E,iii) frequently included ARID1B, and were influenced, in part and as expected, by the transcriptomic similarity between ASD KOs unique to each cell-type (Fig. 2E,iv–v). Expanding the analyses across 2–5 gene combinations using all 23 perturbed ASD genes (2,724 to 7,906 random combinations) likewise confirmed that the average magnitude of convergence was highest in iGLUTs (Fig. 2F).

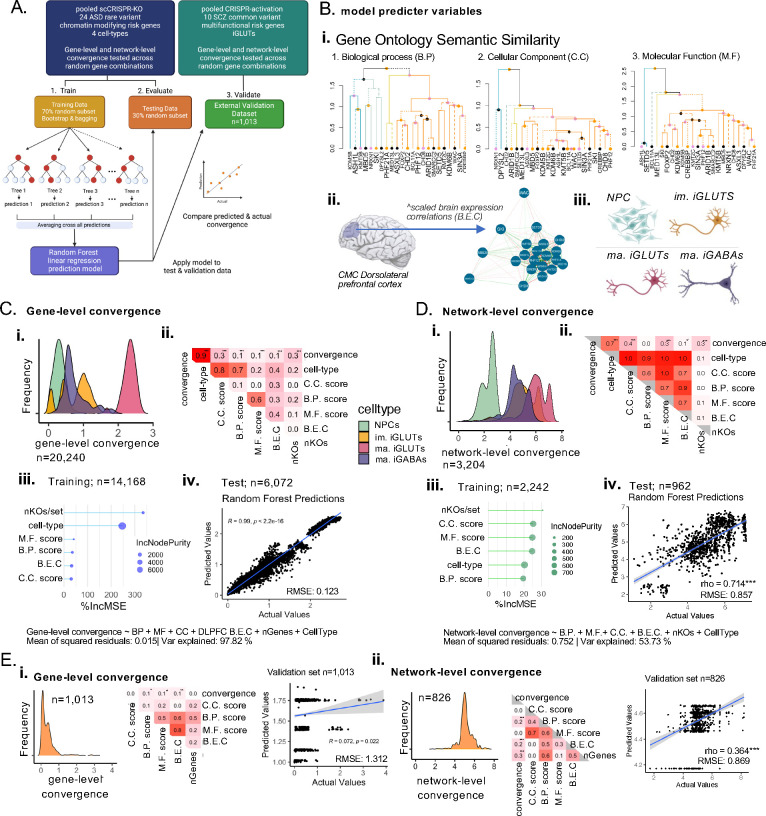

Figure 4. Functional similarity and brain co-expression between ASD/NDD genes predict gene-level and network-level convergence, with unique influences by cell-type.

(A) Training random forest models for gene and network-level convergence - the proportion of cell-types was confirmed as balanced across the training sets and the testing sets and is representative the full data (SI Fig. 15). (B) Predictors included in the model include (i) semantic similarity scores based on gene ontology cellular component (C.C), biological process (B.P.) and molecular function (M.F) geneset membership, (ii) the scaled brain expression correlation of ASD genes in the adult dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), (iii) the cell-type, and (iv) the number of KOs represented in a convergent set, (C) (i) Distribution of gene-level convergence scores show cell-type specific distributions as described in Fig. 2 (n=20,240) – (ii) convergence is significantly correlated with functional similarity and brain co-expressions scores (FDR<0.001). (iii) Functional similarity, brain co-expression, cell-type, and the number of KOs assayed strongly predicted gene-level convergence (nTrees=500, 98% variance explained; mean of squared residuals<0.01) with cell-type as the most important predictor base on percent increase in mean error (%IncMSE) and the increase in node purity (IncNodePurity). (iv) Evaluation of the model in the testing set (n=6072) showed that predicted gene-level convergence by the model strongly correlated with the actual convergence (Pearson’s rho=0.99; Bonferroni p<0.001; root mean squared error (RMSE) =0.12); distribution of the number of nodes and error per tree in the random forest models reported in SI Fig. 15. (D) (i) Distribution of network-level convergence scores show cell-type specific distributions as described in Fig. 3 (n=3,204) – (ii) convergence is significantly correlated with CC and MF functional similarity (Holm’s adjP<0.001) nominally correlated with brain co-expressions scores (Holm’s adjP <0.08) (iii) Functional similarity, brain co-expression, cell-type, and the number of KOs assayed moderately predicted gene-level convergence (nTrees=500, 54% variance explained; mean of squared residuals=0.752) with the number of KOs/set and the C.C scores as the most important predictors. (iv) Evaluation of the model in the testing set (n=962) showed that predicted gene-level convergence by the model strongly correlated with the actual convergence (Pearson’s rho=0.714; Bonferroni p<0.001; RMSE=0.857). (E) Validation of predictor models in an independent scCRISPRa screen of 10 multifunctional SCZ common variant genes (eGenes) perturbed in iGLUTs demonstrated that network-level convergence model had greater predictive power. (i,ii) gene-level and network-level convergence distribution across 1,013 and 826 sets of 2–10 SCZ eGenes – convergence was significantly correlated with B.P (Holm’s adjP<0.05). M.F (Holm’s adjP<0.08), and BEC scores (Holm’s adjP <0.01) at the gene level and the number of KOs/set, B.EC and BP scores (Holm’s adjP<0.001) at the network level. While the gene-level convergence model has more predictive power within our data, it performed more poorly in external validation (RMSE=1.312, rho=0.07, Bonferroni P<0.02,) compared to the network-level model (RMSE=0.87, rho=0.364, Bonferroni P<0.001). (B.P score = semantic similarity of gene ontology: Biological Process membership between KO genes; C.C. score = semantic similarity of gene ontology: Cellular Component membership between KO genes; M.F score = semantic similarity of gene ontology: Molecular functions membership between KO genes; B.E.C = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex expression correlations between KO genes; nKOs = number of KO genes tested for convergence) (#nominal p-value<0.05, *adjP <0.05, **adjP <0.01, ***adjP <0.001).

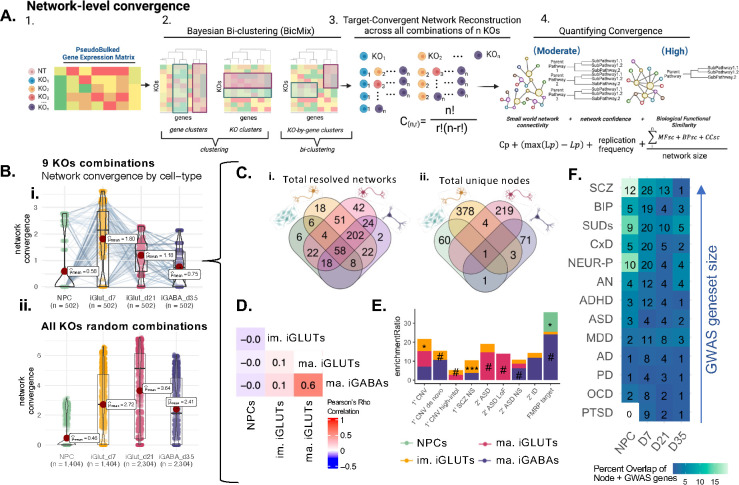

“Convergent networks” are co-expressed genes that share similar expression patterns across ASD gene perturbations42,43 (Fig. 3A). The network connectivity score (“network convergence”) informs the strength and composition of convergent networks across cell types (i.e., networks with more interconnectedness and containing genes with greater functional similarity have increased convergence). Convergent networks generated from either just the 9 ASD genes perturbed in all cell types (502 unique ASD network sets per cell type) (Fig. 3B,i) or across a subset of random combinations of all 23 ASD genes (1,404 to 2,306 sets per cell type) (Fig. 3B,ii) revealed that the strength of the ASD convergent networks was greatest in iGLUTs. By considering just the nine ASD KOs, we observed that while network convergence was generally stronger in iGLUTs, this was not true for all possible networks; although many individual networks increased in strength over the course of differentiation from iNPCs to mature iGLUTs; there was a subset of networks that weakened from iNPCs to immature iGLUTs. Altogether, the number of convergent networks (Fig. 3C,i) and unique (Fig. 3C,ii) network nodes resolved was greatest in iGLUTs, and largely distinct across cell types. Unlike gene-level convergence, network-level convergence showed greater cell-type specificity and magnitude, indicated by the lack of overlapping node genes between cell types (Fig. 3C,ii) as well as the weak correlations of convergence strength between immature and mature cell-types (Fig. 3D; Tables 2,3). The node genes of the convergent networks generated in immature and mature iGLUTs were significantly over-represented for rare variants linked to schizophrenia and ASD (Fig. 3E) and many nodes were annotated common GWAS genes associated with schizophrenia (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3. Network-level convergence resulting from ASD LoF genes is cell-type-specific, greatest in glutamatergic neurons, largely reflects unique hub genes in each cell type, and is enriched for rare and common psychiatric risk in glutamatergic neurons.

(A) Schematic explaining cross-KO cell-type specific convergence at the network level using Bayesian bi-clustering and undirected network reconstruction. (B) Testing the strength of network convergence across all possible combinations of 9 ASD/NDD KO perturbations, (i) the mean strength of network convergence is significantly different by cell-type, with the highest convergence present in immature iGLUTs. However, the same KO combinations test in one cell type may not resolve convergence in another cell type – indicating cell-type specificity. Each point represents the calculated convergence strength of one resolved network. Dots that represent the same combinations of KO perturbations, but tested in each cell type, are connected by a line. (ii) Testing the strength of network convergence across a subset of random combinations of 2–10 genes from the total 23 ASD/NDD KO perturbations, The mean strength of network convergence is significantly different by cell-type, with the highest convergence present in immature and mature iGLUTs, confirming the pattern seen with gene-level convergence (B) Venn diagrams of (i) the total number of networks resolved of the 502 combinations tested across 9 KOs further demonstrate that some KO combinations are only convergent in one cell-type – for example 6 are unique to NPCs. (ii) While overlap of the total number of unique node genes within those networks by cell-type demonstrate that even if the same combination of KOs resolve convergence, the node genes within their networks will be cell-type specific.(E) Enrichment of cell-type specific convergent node genes for rare variant targets revealed significant associations of immature iGLUTs with SCZ non-synonymous (NS) targets and nominal enrichments of mature iGLUTs and ASD LoF targets. (F) Although not significantly enriched, many node genes overlapped with GWAS common variant targets; heatmap representing the percent overlap of unique node genes for each cell-type that are targets of. Number in the center of each tile represent the absolute number of overlapping genes.

Table 2.

Disorder and behavioral associations of top nodes by cell-type.

| Celltype | Top Protein-coding Node | Rare Disorders | GWAS and behavioral associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPCs | KIAA2012 | ADHD/conduct disorder (rs1521882), educational attainment (rs12623702, rs4675248, rs2160317, rs2177083, rs34189321,rs58100125), migraine/T2D (rs6748072), amygdala volume (rs72936662) | |

| Im. iGLUTs | MYH15 | Deafness (AR); de novo SCZ CNV | Social interaction measurement (rs13082569), cognitive function (rs3860537), unipolar depression (rs1531188), MDD (rs113689582), insomnia (rs62266174, rs6768511, rs6786515, rs6795280), BIP (rs1531188) , ANX (rs4855559), educational attainment (rs115910830, rs2290601, rs3860537, rs60785803) |

| Ma. iGLUTs | GALNTL5 | ASD, Spastic paraplegia 48 (AR) | |

| Ma. iGABAs | EREG | Epilepsy, Immune Deficiency Disease | ADHD (rs1350666), wellbeing measurement (rs112444088), learning & memory (pathway) |

Autosomal recessive (AR), Anxiety disorder (ANX) Bipolar Disorder (BIP), Type-2 diabetes (T2D)

Table 3.

Convergent nodes that overlap with CNV and rare variant target genes for each cell-type.

| Celltype | Rare variant gene targets |

|---|---|

| NPCs | AATK, DLC1, PAK6 |

| Int. iGLUTs | ACMSD, HCST, MYH15, PAH, RSP01, SFTPC, SH3RF2, SLC28A2, SNAI2, AC0T6, CSPG4, PYCARD, SLC5A7, SULT1B1, TBXA2R, TEKT5, TEX15, ARG1, ASB14, CACNA1D, OPLAH, GRM4, KCNT1, FKBP6, NPAP1, OCA2, ATP10A |

| Mat. iGLUTs | S100G, TRIM50, FOLR1, COX7B2, KIF23 |

| Mat. iGABAs | CHRND, RETN, PAX6, RIMBP3, SPDYE5, TSKS |

We asked if the functional similarity and brain co-expression between ASD genes predicted convergence. To test this, we trained a prediction model (random forest linear regression)79 using 70% of our data, evaluated it using 30% of our data, and validated in an external dataset43 (Fig. 4A). Functional similarity based on gene ontology membership (Fig. 4B,i), brain co-expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Fig. 4B,ii), cell-type (Fig. 4B,iii), and the number of KOs assayed strongly predicted gene-level convergence (98% variance explained; mean of squared residuals<0.02) (Fig. 4C) and moderately predicted network-level convergence (54% variance explained; mean of squared residuals=0.75) (Fig. 4D). Cell type was the most important predictor of gene-level convergence (Fig. 4C,iii), while cell-type and functional similarity of the individual ASD genes perturbed were of generally equal importance in predicting network-level convergence (Fig. 4C,iii). Our trained model accurately predicted gene-level (Pearson’s rho=0.99, Holm’s adjP<0.001, RMSE=0.12) (Fig. 4C,iv) and network-level convergence in our testing set (Pearson’s rho=0.714, Bonferroni <0.001, RMSE=0.86) (Fig. 4D,iv), and performed moderately well in predicting network-level convergence (RMSE=0.87, rho=0.364, Bonferroni P<0.001) (Fig. 4E,ii) but not gene-level convergence (RMSE=1.3, rho=0.072, Holm’s adjP<0.02 (Fig. 4E,ii) in the external dataset. This inability to predict gene-level convergence may reflect fundamental differences in the training and validation data – specifically that the prediction model was based on CRISPR-KO of large-effect rare variant ASD target genes while the external dataset resulted from CRISPR-activation of small-effect common variant schizophrenia target genes. Altogether, although cell-type, functional similarity and co-expression were sufficient to predict the extent of convergence at the network and gene-level, the magnitude and direction of the perturbation and/or whether the perturbation genes were rare or common variant targets may also be important contributors.

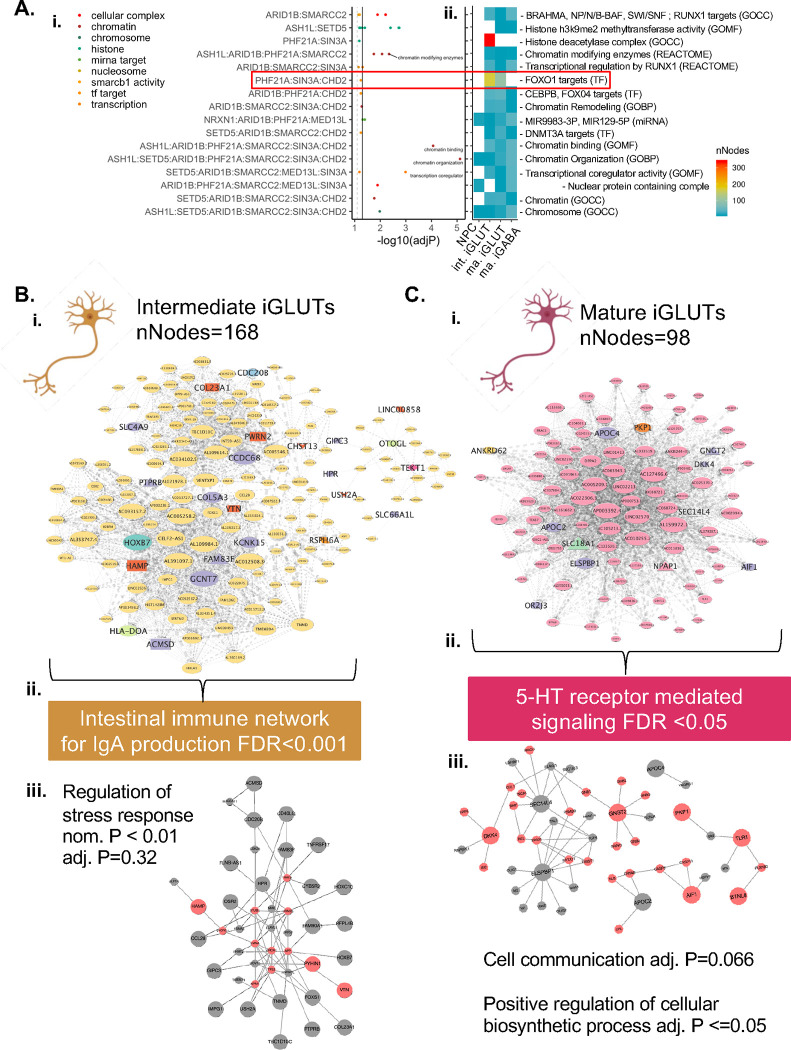

Functional mapping of gene annotations (FUMA80) for the nine ASD genes perturbed in each cell-type allowed for finer resolution of shared function. With the majority involved in chromatin biology and genetic regulation, few were targets of specific TFs and miRNAs, yet convergence based on these functionally informed subsets of ASD KOs was cell-type specific (Fig. 5A). For example, ASD targets of miRNA129–5P resolved networks across all cell-types, but with the strongest convergence in mature iGABAs (SI Fig. 14) while ASD genes targeted by FOXO1 (PHF21A, SIN3A, CHD2), convergent networks were only resolved in immature and mature iGLUTs (Fig 5A,i–ii), distinct between these two cell types (Fig. 5B,C), and comprised of non-overlapping node genes that contained many targets of common and rare variants associated with psychiatric diagnoses. The FOX01-target convergent network in immature iGLUTs (Fig. 5B,i) was significantly enriched for immune networks (FDR<0.001), whereas in mature iGLUTs it was significantly enriched for serotonin (5-HT) receptor mediated signaling (FDR<0.05) (Fig. 5C,ii). Moreover, PPI networks between node genes were enriched for stress response (p <0.01) in immature iGLUTs and cell communication (FDR=0.066) and positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic processes in mature iGLUTs (FDR <=0.05) (Fig. 5C,iii). Although convergent networks generated between cell types were largely unique and non-overlapping, they shared common biological and disorder enrichments, hinting at novel processes that were not predicted by ASD risk genes alone.

Figure 5. Distinct cell-type-specific networks converge on FOXO1 targets in immature and mature glutamatergic neurons.

(A) Functional gene annotation (FUMA) identified sets of KOs with more specific shared function, beyond chromatin organization, and shared regulation by transcription factor and miRNAs. Network convergence across KOs based on functional annotation showed cell-type specificity and resolved networks with variable convergence and gene membership (i-ii). Convergent networks between targets of FOXO1 (PHF21A, SIN3A, and CHD2) were resolved in iGLUTs, but not NPCs and iGABAs. FOXO1 target convergent networks were unique in immature (B,i) and mature (C,i) iGLUTs. Central nodes in immature and mature iGLUTs included non-overlapping gene targets of psychiatric common and rare variants. The convergent network in immature iGLUTs was significantly enriched for immune networks related to IgA production (FDR<0.001) (B,ii) – network expansion using FunMap identified protein-protein connection between node genes that were nominally enriched for the regulation of stress response in immature iGLUTs (B,iii) (nom. P<0.01, adj. P=0.32). The convergent network in mature iGLUTs was significantly enriched 5-HT receptor mediated signaling (FDR<0.05) (C,ii) – network expansion identified a PPI network nominally enriched for cell communication (adj. P=0.066) and significantly enriched for positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic processes in mature iGLUTs (C,iii) (adj. P <=0.05).

Stratification of ASD genes by zebrafish behavior, brain structure, and circuit function.

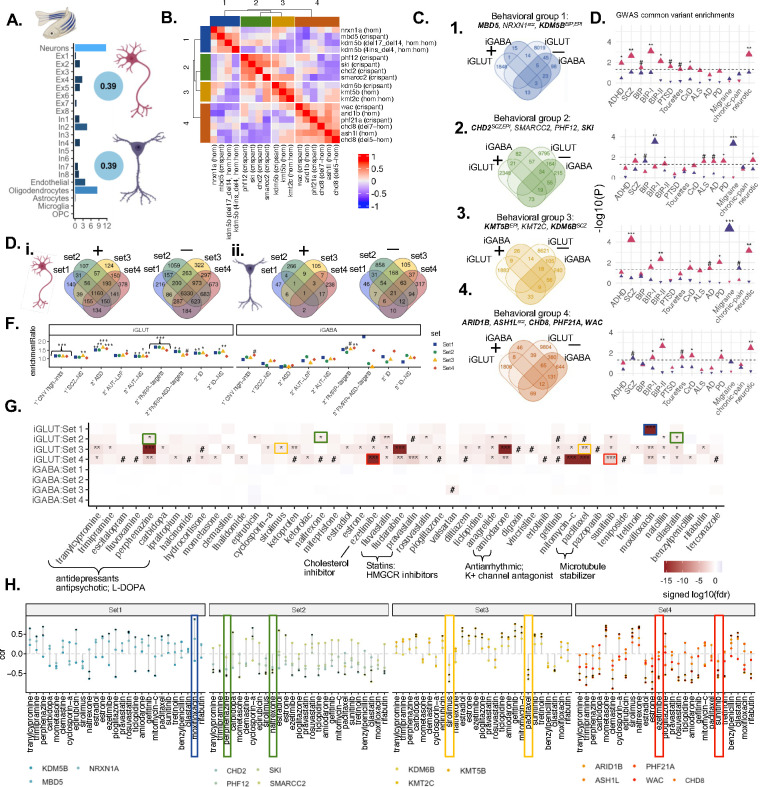

A comprehensive in vivo high-throughput, automated behavioral analysis in zebrafish31 recently revealed clear stratification of ASD genes based on basic arousal and sensory processing behaviors in the developing vertebrate brain. Leveraging zebrafish behavioral data for fifteen ASD genes for which we have iGLUT and iGABA analyses, we asked to what extent molecular convergence underlies this behavioral stratification. Notably, the cell-type deconvolution of the zebrafish brain using human single-cell reference data highlighted neurons as the highest represented cell type; zebrafish brain gene expression was robustly correlated with in vitro human-derived mature neurons (Fig. 6A). Correlation of zebrafish KOs based on behavioral effects yielded four clear groups of genes: set 1 (MBD5, NRXN1, KDM5B), set2 (CHD2, SMARCC2, PHF12, SKI), set 3 (KMT5B, KMT2C, KDM6B), and set 4 (ARID1B, ASH1L, CHD8, PHF21A, WAC) (Fig. 6B; Table 4). Gene-level convergence between genes in these sets was distinct, largely non-overlapping between cell-types, and stronger in mature iGLUTs than mature iGABAs (Fig. 6C–D). Likewise, neuropsychiatric GWAS (Fig. 6C) and rare LoF genes (Fig. 6D), showed unique risk-associations by set, and stronger risk associations in the iGLUTs.

Figure 6. ASD/NDD genes clustered based on behavioral phenotypes in zebrafish resolve unique gene-level convergent signatures in mature human glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons that are uniquely enriched for psychiatric risk and predicted drug reversers.

(A) Gene expression in human mature iGLUTs and iGABAs correlate with expression in the zebrafish brain. Cellular deconvolution of wild-type (wt) zebrafish brain expression based on an adult single-cell brain reference identified neurons as the largest proportion of cells in the fish brain. Gene expression in wt zebrafish brain significantly positively correlate with gene expression of human-induced mature iGLUTs (rho=0.39, Holm’s adj.P<0.001) and iGABAs (rho=0.39, Holm’s adj.P <0.001) (SI Fig. 9). (B) ASD/NDD risk genes uniquely cluster based on wake/startle behavioral responses in zebrafish KOs. Based on correlations between 24 phenotypic measurements related to sleep, wake, and startle response in zebrafish KOs, ASD/NDD risk genes clustered into four behavioral sets. Set 1: MBD5, NRXN1, KDM5B; Set 2: CHD2, SMARCC2, PHF12, SKI; Set 3: KMT5B, KMT2C, KDM6B; Set 4: ARID1B, ASH1L, CHD8, PHF21A, WAC. (C) Gene-level convergence within these sets is largely non-overlapping between mature iGLUTs and iGABAs and (D) show unique enrichments for common psychiatric risk gene targets. (E) Within each cell-type, behavioral sets have both shared and unique convergent genes (i-ii). (F) In both iGABAs and iGLUTs, all four behavioral sets were enriched for FMRP targets. Gene targets of neurodevelopmental rare variants were only significantly enriched for convergent signature in mature iGLUTs – with behavioral set 4 uniquely significantly enriched for secondary targets of ASD loss-of-function variant and set 3 uniquely enriched for primary targets of SCZ non-synonymous variants (iii). (F). Prediction of drugs “reversers” from the LiNCs database targeting these convergent signals in mature neurons identify shared and unique drugs enriched across the sets (i.e., antipsychotic perphenazine in iGLUTs) and some specific to unique convergence (i.e., valsartan only in in Set 3 iGABAs, and sirolimus in Set 3 iGLUTs). (G) Top predicted drugs show opposing effects on zebrafish behavior compared to individual ASD KOs – these signatures do not always correspond with their predicted direction of effect on transcriptomic convergence. (#nominal p-value<0.05, *FDR<0.05, **FDR<0.01, *FDR<0.001)

Table 4.

Disorder and behavioral associations of top nodes by cell-type and behavioral set.

| Cell type | Top Node | Gene name | Meta P | Z-score | Rare Disorders | GWAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature H3LUT | 1 | CNBP | Sterol-mediated transcriptional repression | 2.9e-16 | 8.18 | Myotonic Dystrophy, Neuromyotonia & axonal neuropathy (AR), Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Deafness (AR), FragMe-X tremor/ataxia, ALS | |

| ANKRD36 | 1.95e-18 | 8.8 | |||||

| 2 | FOXJ3 | 1.7e-17 | 8.5 | ||||

| SOX12 | 5.3e-44 | −13.9 | ASD, Epilepsy, NDO | ||||

| 3 | FOXJ3 | Gene expression regulation/chromatin | 1.9e-19 | 9.02 | EA (rs35011283) | ||

| S0X12 | Implicated in cell fate decisions during development | 1.6e-17 | −8.52 | Microphtalmia Syndromic 12 (neurological) | Memory performance (rs78532272) | ||

| 4 | FOXJ3 | 7.9e-22 | 9.6 | ||||

| ANKRD36 | Ankyrin Repeat Domain 36 | 6.6-e26 | −10.5 | Neuropathy, Giant Axonal Nonsyndromic Deafness (AR) | SCZ (rs9631085), neuroimaging (rs11692435, rs167684, +6) | ||

| Mature iGABA | 1 | UBE2D4 | Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme E2 D4 | 1.2e-09 | 6.1 | ||

| PRKAG2 | Protein Kinase AMP-Actrvated Non-Catalytic Subunit | 6.7e-7 | −4.97 | Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, Neuromuscular Disease, Specific Language Impairment, Microencephaly, Epilepsy | EA (rs1860735, rs2538046, rs4726070), ASD/SCZ (rs115136442), impulse control (rs2302532), BIP (rs7795096), memory (rs2536058) | ||

| 2 | MYL3 | BBB & immune cell trasnmigration | 4e-12 | 6.9 | Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, Microencephaly, Epiliepsy | ||

| TNFSF11 | 3.6e-10 | −6.3 | ID, NDD, developmental & epileptic encephalopathy, IBS, | ||||

| 3 | KIF1A | Axonal Transporter Of Synaptic Vesicies | 8.8e-12 | 6.8 | ID, ASD, neuropathy, Epilepsy, Spastic Ataxia, Cortical Dysplasta, Alacrima, Achala sia, and Impaired ID Syndrome | Insomnia (rs10196604, rs4455151) | |

| UNC5C | Netrin Receptor | 3.98e-8 | −5.5 | Alzheimer Disease. Familial 1 | Insomnia (rs371745379), wellbeing (rs116984513), OCO (rs17384439), cognition (rs3846455), unipolar depression (rs6822806) | ||

| 4 | UBE2D4 | 8.5e-13 | 7.2 | ||||

| UBC | 1.7e-10 | −6.4 | Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, muscular dystrophy | Sleep duration (rs10773112), AD (rs78184510), |

Restricting to (cMAP)81 drugs with human clinical and experimental zebrafish data31, the drugs predicted to reverse convergent signatures in iGLUTs and iGABAs included targets of glucocorticoid, androgen, and serotonin receptors, as well as drugs regulating inflammatory signaling (statins, immunomodulatory chemo-therapy drug, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) (Fig. 6F). While some drugs were predicted to have broad genotype-independent effects reversing ASD signatures (e.g., antipsychotic perphenazine in iGLUTs), others were predicted to yield more precise clinical responses (e.g., sirolimus only in Set 3 iGLUTs. Notably, mirroring the lack of significant disorder enrichments, few of these drugs significantly reversed convergent signatures in iGABAs. By considering existing pharmacological effects of the top drugs on zebrafish behavior31, some of the predicted drug reversers were shown to oppose effects on ASD related phenotypes in zebrafish. Yet, the direction of effect predicted based on transcriptomic convergence in human neurons did not always align with anti-correlating behavioral effects in zebrafish. For example, perphenazine was significantly indicated as a reverser of transcriptomic convergence in iGLUTs sets 2,3 and 4, but only reversed the behavioral phenotypes associated with set 2 genes (CHD2, SMARCC2, PHF12, SKI). The mechanisms resulting in transcriptomic convergence in vitro only partially explain behavioral convergence in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Towards empirically resolving the extent that ASD risk gene effects converge upon a smaller number of common pathways7, we applied a pooled CRISPR-KO strategy targeting 29 highly penetrant ASD genes across neural cell types. Convergence was dynamic, driven by co-expression patterns, and yielded networks of varied strength and composition between cell types and across neurodevelopment, overall greatest in mature glutamatergic neurons. Both molecular and phenotypic stratification of ASD genes resulted in unique cell-type-specific patterns of convergence that regulate different biological processes. Distinct cell-type-specific convergent patterns predict drugs capable of reversing both gene expression and phenotypic effects.

Our findings add to a wealth of recent studies examining the convergent impact of LoF ASD genes during neurogenesis23–31. Transcriptomic and epigenomic analyses of post-mortem brain from ASD cases likewise indicate convergent molecular signatures82 and subtypes of ASD83. But how to connect convergent causes during neurogenesis with differences in social communication, restricted interests, and repetitive behavior? One possibility is that temporal dysregulation of neurodevelopmental gene networks84 results in asynchronous neurodevelopment of cortical glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons26 leading to excitation-inhibitory imbalance32. Our data suggests additional mechanisms, demonstrating that, across ASD genes, studying loss of expression specifically in postmitotic neurons also resolves convergent networks, but of distinct size and composition from those identified during neurogenesis. Put simply, the same ASD genes resulted in different convergent effects across cell types. This observation may inform the etiology of other complex genetic disorders with diverse risk genes and pathophysiological evidence indicating effects in multiple cell types.

Although rare LoF ASD gene mutations tend to confer large effects in the individuals who carry them, the small effects of common variants account for much of the genetic risk for ASD at the population level1,85. The differences in expressivity and incomplete penetrance of high effect-size rare variants is frequently attributed to diversity across polygenic backgrounds86; in vitro, ASD gene effects are indeed influenced by the individual genomic context26. In psychiatry, common genetic variants are more associated with cross-disorder behavioral dimensions87 and rare variants with co-occurring intellectual disability88. Common risk variants interact with rare mutations to determine individual-level liability in ASD3,89,90, schizophrenia91,92, epilepsy93, Huntington’s disease94 and more95. Our results, highlighting that convergence downstream of ASD gene effects are enriched for cross-disorder GWAS variants and rare LoF genes, inform pleiotropy of genetic risk for psychiatric disorders. Moving forward, we argue that it is critical that empirical functional genomic studies systematically consider the impact of common and rare variants together, including screening the impact of LoF genes in hiPSC lines derived from donors with high and low polygenic risk scores96. Intriguingly, even susceptibility to environmental risk factors for ASD (e.g., valproic acid97) seems to be mediated by genetic background98. Deeper phenotypic characterization of ASD effects across donors will be critical in determining how complex genetic (or environmental) interactions shape cellular phenotypes, circuit function, and human behavior in the clinic.

In the post-mortem brain, ASD gene signatures are not just associated with downregulation of co-expression modules involving synaptic signalling99, but also upregulation of microglial and astrocyte gene modules83,99–105. The extent to which increased neuroimmune activity in ASD is a response to cellular or environmental sources of inflammation, or indicative of a non-cell autonomous role for glia cells in risk is unclear; evidence supports both possibilities. Consistent with a model of maternal immune activation during neurodevelopment106, glucocorticoids and inflammatory cytokines perturb the expression of psychiatric risk genes107,108, altering the regulatory activity of psychiatric risk loci109, and interfering with neuronal maturation in brain organoids110. Yet, in vivo analysis of ASD genes in zebrafish revealed global increases in microglia31 and in vitro screening in human microglia uncovered roles in endocytosis and uptake of synaptic material111. Indeed, given the reciprocal relationships between neuronal activity and glial function, epigenetic state, and gene expression112–115, it seems probable that both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous effects underlie and/or exacerbate ASD gene effects.

In summary, we demonstrate that convergent effects of ASD risk genes are dynamic across cell-type-specific contexts. These signatures can be leveraged for translational insights into precision medicine, with top predicted pharmacological reversers of convergent networks including drugs with known anti-psychotic, anti-anxiety, and anti-depressive effects, as well as novel points of individualized therapeutic intervention. If the convergence of diverse risk genes on common molecular pathways indeed explains how genetically heterogeneous variants result in similar clinical features, then achieving precision medicine will ultimately entail genetic stratification of cases, whereby clinical decisions are informed based on shared genetic risk factors between individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of neural cells:

Informed consent was obtained at the National Institute of Mental Health, under the review of the Internal Review Board of the NIMH. hiPSC work was reviewed by the Internal Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai as well as by the Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Yale University. Fibroblasts were genotyped by IlluminaOmni 2.5 bead chip genotyping116,117, PsychChip118, and exome sequencing118; hiPSCs118 were validated by G-banded karyotyping (Wicell Cytogenetics) and genome stability monitored by Infinium Global Screening Array v3.0 (lllumina). SNP genotype was inferred from all RNAseq data using the Sequenom SURESelect Clinical Research Exome (CRE) and Sure Select V5 SNP lists to confirm that neuron identity matched donor. Control hiPSCs were cultured in StemFlex media (Gibco, #A3349401) supplemented with Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco, #15240062) on Geltrex-coated plates (Gibco, #A1413302). Cells were passaged at 80–90% confluence with 5mM EDTA (Life Technologies #15575–020) for 3 min at room temperature (RT). EDTA was aspirated and cells dissociated in fresh StemFlex media. Media was replaced every 48–72 hours for 4–7 days until the next passage.

Transient transcription factor overexpression from stable clonal hiPSCs was used to induce control hiPSCs to iNPCs (here SNaPs)72, iGLUTs65, and iGABAs71. We transduced hiPSCs from two control donors (553–3, male; 3182–3, female) with lentiviral pUBIQ-rtTA (Addgene #20342) and tetO-NGN2-eGFP-NeoR (Addgene #99378) for iNPCs and iGLUTs, or pUBIQ-rtTA (Addgene #20342), tetO-ASCL1-PuroR (Addgene #97329), and tetO-DLX2-HygroR (Addgene #97330) for iGABAs. Following transduction by spinfection at 1000g for 1 hour at 37°C, hiPSCs were subjected to 48-hour antibiotic selection (1mg/mL neomycin G418 (Thermo #10131027), 0.5μg/mL puromycin (Thermo #A1113803), and/or 250μg/mL hygromycin (Thermo, #10687010) and then clonalized by expansion from single colonies. Ultimately, clonal and inducible iNPC/iGLUT 3182–3-clone5 and iGABA 553–3-clone34 hiPSCs were validated lentiviral genome integration by PCR, doxycycline induced transcription factor expression by qPCR, and robust and consistent neuronal induction confirmed by RNA-seq and immunocytochemistry for relevant cell type markers. Analyses throughout reflect data from iGLUT 3182–3-clone5 (iNPC, d7 iGLUT and d21 iGLUT) and iGABA 553–3-clone34 (d36 iGABA) (SI Fig 2A–B).

iNPCs:

At DIV0, 3182–3-clone5 hiPSCs were dissociated and plated at 1.5 × 106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 6-well plates (1:250 dilution coating) in SNaP Induction Media (DIV0): DMEM/F12 with Glutamax (ThermoFisher, 11320082), Glucose (0.3% v/v), N2 Supplement (1:100, ThermoFisher, 17502048), Doxycycline (2 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, D9891), LDN-193189 (200 nM; Stemgent, 04–0074), SB431542 (10 μM; Tocris, 1614), and XAV939 (2 μM; Stemgent, 04–00046) supplemented with 25 ng/mL Chroma I ROCK2 Inhibitor. After 24 hours, DIV2, cells were fed with Selection Media: DMEM/F12 with Glutamax, Glucose (0.3% v/v), N2 Supplement (1:100), Doxycycline (2 μg/mL), Geneticin (0.5 mg/mL; Thermofisher, 10131035), LDN-193189 (100 nM), SB431542 (5 μM), and XAV939 (1 μM). After 48 hours post induction (DIV2), SNaPs were dissociated with Accutase for 10 minutes at 37°C, quenched in DMEM, pelleted at 800g for 5 minutes, and replated at 1.5×106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 6-well plates in SNaP Selection Media supplemented with Geneticin (0.5 mg/mL). After 16–18 hr (DIV3), medium was switched to SNaP maintenance Medium: DMEM/F12 with Glutamax, Penn/Strep (1:100), MEM-NEAA (1:100; Life Technologies, 10370088), B27 minus Vitamin A (1:50; Life Technologies, 12587010), N2 Supplement (1:100; Life Technologies, 17502048), recombinant human EGF (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems, 236-EG-200), recombinant human basic FGF (10 ng/mL; Life Technologies, 13256029), Geneticin (0.5 mg/mL), and Chroman I (25 ng/mL). Cells were fed every 48 hours with SNaP maintenance medium lacking Chroman I and Geneticin. Cells were dissociated and seeded weekly at a density of 1.25–1.5×106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 6-well plates until NPC morphology was observed and persistent. Cells were expanded and cryofrozen.

DIV7 iGLUTs:

3182–3-clone5 iNPCs were thawed and seeded at 1× 106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 12-well plates. NGN2 expression was induced with Doxycycline (2 μg/mL) for 24 hrs (DIV0) with antibiotic selection for 48 hrs (DIV1–3) in SNaP maintenance medium. At DIV 4 SNaPs were dissociated with Accutase, switched into Neuronal Medium: Brainphys (Stemcell, 05790), Glutamax (1:100), Sodium Pyruvate (1 mM), Anti-Anti (1:100), N2 (1:100), B27 without vitamin A (1:50), BDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 248-BD-025), GDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 212), dibutyryl cAMP (500 μg/mL; Sigma, D0627), L-ascorbic acid (200 μM; Sigma, A4403), Natural Mouse Laminin (1.2 μg/m; Thermofisher, 23017015) and seeded in Geltrex-coated (1:120 dilution coating) 12-well plates. Medium was changed every 24 hrs until DIV7 harvest.

D21 iGLUTs:

hiPSCs were harvested in Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, AT-104) for 5 minutes 37°C, dissociated into a single-cell suspension, quenched in DMEM, pelleted via centrifugation for five minutes at 1000 rcf and resuspended in StemFlex containing 25 ng/mL Chroma I ROCK2 Inhibitor and 2.0 μg/mL doxycycline (DIV0), seeded 1 × 106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 6-well plates (1:250 dilution coating), and incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day, DIV1, hiPSCs were subjected to 48-hour antibiotic selection by medium replacement with Induction Media: DMEM/F12 (Thermofisher, 10565018), Glutamax (1:100; Thermofisher, 10565018), N-2 (1:100; Thermofisher, 17502048), B27 without vitamin A (1:50; Thermofisher, 12587010), Antibiotic-Antimycotic (1:100) with 1.0μg/mL doxycycline and 0.5mg/ml Geneticin. At DIV3, cells were treated with 4.0μM cytosineβ-D-arabinofuranoside hydrochloride (Ara-C) and 1.0μg/mL doxycycline to arrest proliferation and eliminate non-neuronal cells in the culture. At DIV4 immature neurons were dissociated with Accutase and 5 units/mL DNAse I at 37°C for 7–10 min, quenched in DMEM, centrifuged for five minutes at 1,500 rpm and resuspended in 25 ng/mL Chroma I ROCK2 Inhibitor, 1.0 μg/mL doxycycline and 4.0μM Ara-C and switched to Neuron Medium: Brainphys (Stemcell, 05790), Glutamax (1:100), Sodium Pyruvate (1 mM), Anti-Anti (1:100), N2 (1:100), B27 without vitamin A (1:50), BDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 248-BD-025), GDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 212), dibutyryl cAMP (500 μg/mL; Sigma, D0627), L-ascorbic acid (200 μM; Sigma, A4403), Natural Mouse Laminin (1.2 μg/mL; Thermofisher, 23017015) and seeded 7 × 105 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated (1:60 dilution coating) 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day, DIV 6, Chroman I was removed from culture and Ara-C lowered to 2.0 μM with a full Neuronal medium change. At DIV 7 a full Neuronal Medium change was performed to remove doxycycline and Ara-C from culture, to allow for antibiotic resistant genes silencing. From DIV7 onwards, half neuronal medium changes were performed every 72 – 96 hrs until mature DIV 21 for harvest.

DIV36 iGABAs:

hiPSCs were harvested in Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, AT-104) for 5 minutes 37°C, dissociated into a single-cell suspension, quenched in DMEM, pelleted via centrifugation for five minutes at 1000 rcf and resuspended in StemFlex containing 25 ng/mL Chroma I ROCK2 Inhibitor and 2.0 μg/mL doxycycline (DIV0), seeded 1.5–2× 106 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated 6-well plates (1:250 dilution coating), and incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day, DIV1, hiPSCs were subjected to 48-hour antibiotic selection by medium replacement with Induction Media: DMEM/F12 (Thermofisher, 10565018), Glutamax (1:100; Thermofisher, 10565018), N-2 (1:100; Thermofisher, 17502048), B27 without vitamin A (1:50; Thermofisher, 12587010), Antibiotic-Antimycotic (1:100) with 1.0μg/mL doxycycline, 1.0 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma, P7255) and 250 μg/mL hygromycin (Sigma, 10687010). At DIV3, cells were treated with 4.0μM cytosineβ-D-arabinofuranoside hydrochloride (Ara-C) and 1.0μg/mL doxycycline to arrest proliferation and eliminate non-neuronal cells in the culture. At DIV5 immature neurons were dissociated with Accutase and 5 units/mL DNAse I at 37°C for 7–10 min, quenched in DMEM, centrifuged for five minutes at 1,500 rpm and resuspended in 25 ng/mL Chroma I ROCK2 Inhibitor, 1.0 μg/mL doxycycline and 4.0μM Ara-C and switched to Neuron Medium: Brainphys (Stemcell, 05790), Glutamax (1:100), Sodium Pyruvate (1 mM), Anti-Anti (1:100), N2 (1:100), B27 without vitamin A (1:50), BDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 248-BD-025), GDNF (20 ng/mL; R&D, 212), dibutyryl cAMP (500 μg/mL; Sigma, D0627), L-ascorbic acid (200 μM; Sigma, A4403), Natural Mouse Laminin (1.2 μg/mL; Thermofisher, 23017015) and seeded 7 × 105 cells per well onto Geltrex-coated (1:60 dilution coating) 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day, DIV 6, Chroman I was removed from culture and Ara-C lowered to 2.0 μM with a full Neuronal medium change. At DIV 7 a full Neuronal Medium change was performed to remove doxycycline and Ara-C from culture, to allow for antibiotic resistant genes silencing. From DIV7 onwards, half neuronal medium changes were performed every 72–96 hrs until mature DIV 36 for harvest.

CRISPR knockout gRNA library design (Thermofisher) and validation

From the 102 highly penetrant loss-of-function (LoF) gene mutations associated with ASD (58 gene expression regulation, 24 neuronal communication genes, 9 cytoskeletal genes, and 11 multifunction genes)2, gene ontology and primary literature research identified 26 epigenetic modifiers specifically involved in chromatin organization, rearrangement, and modification. ASD gene expression (RNA-seq RPKM in iGLUTs) was plotted against significance of ASD association (TADA FDR Values), to ensure selection of top ASD genes with the highest expression and highest ASD association. ASD gene expression was confirmed across development in the brain (BrainSpan119), and in bulk and scRNA-seq (SI Fig. 1B–C). 21 epigenetic modifiers (ASH1L, ASXL3, ARID1B, CHD2, CHD8, CREBBP, KDM5B, KDM6B, KMT2C, KMT5B, MBD5, MED13L, PHF12, PHF21A, POGZ, PPP2R5D, SETD5, SIN3A, SKI, SMARCC2, WAC,) as well as two transcription factors with putative roles as chromatin regulators (FOXP2, BCL11A) were selected (SI Fig. 1A). Gene regulatory transcription factors, general transcription factors, and DNA replication genes were excluded. Three extensively studied synaptic genes (NRXN1, SCN2A, SHANK3) with roles in ASD were included as positive controls and three under-explored genes for ASD role in neuronal communication genes (ANK3, DPYSL2, SLC6A1) were also included in the library.

Individual DNA from glycerol stocks of Invitrogen™ LentiArray™ Human CRISPR Library gRNAs-PuroR (ThermoFisher, A31949) (3–4 individual gRNAs per gene, see SI Table 1) were prepared using GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (K0503) and pooled at an equimolar ratio and a 5-fold ratio of scramble control gRNA plasmid. Library quality was confirmed by restriction enzyme digest (10x Cutsart NEB), agarose gel purification using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (#28706) to check library purity, followed by Mi-seq for gRNA count distribution (SI Fig. 2D). Based on the abundance of gRNAs from Mis-seq, 4 ASD gene targets were highly unlikely to be resolved in the final experiments – POGZ, PP2R5D, SHANK3, SLC6A1 – and 3 with low abundance and less likely to be resolved (SCNA2, FOXP2, DYPSL2) (SI Fig. 2E).

Lentiviral Cas9v2-HygroR (Addgene, 98291) and pooled LentiArray-gRNA-PuroR CRISPR-KO library were packaged as high-titer lentiviruses (Boston Children’s Hospital Viral Core) and experimentally titrated in each cell type. Highest viable MOI was used for Cas9v2 and MOI < 0.5 for lentivirus gRNAs pool library.

CRISPR and gRNA delivery:

Lentiviral Cas9v2-HygroR (Addgene #98291) transduction of iNPCs, day 4 (iGLUTs), or day 5 (iGABAs) occurred via spinfection (one hour at 1,000 g) and followed by 72 hr hygromycin (250 μg /mL) (except for iGABAs, which express inducible hygromycin resistance at this stage). Pooled Invitrogen™ LentiArray™ Human gRNA-PuroR CRISPR-KO Library gRNAs (ThermoFisher #A31949) (MOI 0.3–0.5) were transduced via spinfection three days prior to harvest (e.g., d4 for D7 iGLUTs, d18 for D21 iGLUTs, d33 for d36 iGABA), with fresh medium containing puromycin (1 μg/mL) added 16–24 hours post transduction of gRNAs. For mature iGLUTs and iGABAs, as doxycycline was removed from medium at DIV7, and by DIV18 neurons had lost transcription factor linked antibiotic resistance, at 24 hours post-transduction (DIV19 or DIV34) puromycin (1 μg/mL) and hygromycin (250 μg /mL) were added to media for 48-hr antibiotic selection prior to harvest (SI Fig. 3A,i).

Dissociation to single cells:

Cells were dissociated 72 hrs post gRNA library delivery for single cell sequencing, as iNPCs, DIV7 and DIV21 iGLUTs, or DIV36 iGABAs as follows:

iNPCs and DIV7 iGLUTs were dissociated in accutase for 5min @37°C, washed with DMEM/10%FBS, centrifuged at 1,000xg for 5 min, gently resuspended, and counted.

DIV21 iGLUTs and DIV36 iGABAs were dissociated with papain. Papain was pre-warmed (39°C) for 30 minutes in HBSS (ThermoFisher, 14025076), HEPES (10 mM, pH 7.5) EDTA (0.5 mM), Papain (0.84 mg/mL; Worthington-Biochem, LS003127). The cells were washed with PBS-EDTA (0.5 mM) and 300 uL of papain solution and 5 units of DNAse I was added per well of 12-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 10–15 minutes, 125 rpm. Dissociation was quenched with DMEM-10%FBS. Detached neurons were broken by gentle manual pipetting, pelleted at 600 g for 5 minutes, resuspended in DMEM-10%FBS, filtered through a cell strainer and counted and submitted for 10X sequencing.

Cells were loaded into 10X in 4 lanes per cell type, targeting 20,000 cells per lane for a total of ~80,000 targeted cells per cell type. scRNA-seq was performed at Yale Genomics Core with the 10X single cell 5’ v2 HT with CRISPR barcode kit (SI Fig. 3A,ii).

Analysis of single-cell CRISPRko screens in NPCs, DIV 7, DIV 21 iGLUTs and DIV 36 iGABAs.

mRNA sequencing reads were mapped to the GRCh38 reference genome using the Cellranger Software. To generate count matrices for GDO (gRNA) libraries, the kallisto indexing and tag extraction (kite) workflow were used. Count matrices were used as input into the R/Seurat package120 to perform downstream analyses, including QC, normalization, cell clustering, GDO demultiplexing, and covariate regression76,121.

Normalization and downstream analysis of RNA data were performed using the Seurat R package (v.2.3.0), which enables the integrated processing of multimodal single-cell datasets. CRISPR-screen experiments in each cell-type were processed independently. Within each cell-type, ~100–80,000 cells were sequenced across 4 lanes. gRNA and RNA UMI feature counts were filtered removing the top and bottom decile of cells based on distribution of counts in each cell-type. The percentage of all the counts belonging to the mitochondrial, ribosomal, and hemoglobin genes calculated using Seurat::PercentageFeatureSet were filtered with cell-type specific thresholds, given the relatively high proportion of mitochondrial genes expressed in neurons. Mitochondrial, ribosomal, and hemoglobin genes as well as MALAT1 were removed (^RP[SL][[:digit:]]|^RPLP[[:digit:]]|^RPSA|ĤB[AEGQ][[:digit:]]|ĤB[ABDMQ]|^MT-|^MALAT1$). Lowly expressed genes, those that had at fewer than 2 read counts in 90% of samples were also removed. Hashtag and guide-tag raw counts were normalized using centered log ratio transformation, where counts were divided by the geometric mean of the corresponding tag across cells and log-transformed. gRNA demultiplexing was performed using the Seurat::MULTIseqDemux function for each lane individually and then counts were merged across lanes (SI Fig. 3B). In NPCs, 94,363 cells were retained after filtering and removal of negatively assigned cells with 62,7% classified as doublets and 37.3% classified as singlets. In DIV7 and DIV21 iGLUTs, 57,685 and 31,473 cell were retained with 34% and 9.8% doublets and 66% and 90.2% singlets respectively. In DIV35 iGABAs, 64,462 cells were retained with 48.3% doublets and 51.7% singlets. For all downstream analysis only cells with “singlet” gRNA classification were used (26,549–38,097 cells per experiment) (SI Fig. 3C–E).

Cell-type specific population heterogeneity correction.

Gene-expression based clustering was largely driven by cellular heterogeneity, cell quality, and sequencing lane effects. We found that gRNA identity was not correlated with these covariates and thus sought to remove transcriptomic variability to analyze the data as a more homogenous cell population (SI Fig. 4–7). To adjust for cellular heterogeneity driving clustering within a cell population we developed maturity and cellular subtype scores across both perturbed and non-perturbed cells. First, variation related to cell-cycle phase of individual cells was accounted for by assigning cell cycle scores using Seurat::CellCycleScoring which uses a list of cell cycle markers122 to segregate by markers of G2/M phase and markers of S phase. Second, to address variance due to cellular heterogeneity within a single experiment, we adapted the method applied by Seurat::CellCycleScoring to calculate a “Maturity. Score” and “Subtype.Score” for each cell based on cellular subtype (more variable in mature GABAergic neurons) and developmental time-point specific markers (mora variable in NPCs and immature iGLUTs) (SI Table 2). Cells with outlier maturity scores and subtype scores were removed from downstream analyses. RNA UMI count data were then normalized, log-transformed and the percent mitochondrial, hemoglobulin, and ribosomal genes (markers of cell quality), lane, cell cycle scores (Phase), and maturity scores regressed out using Seurat::SCTransform. The scaled residuals of this model represent a ‘corrected’ expression matrix, that was used for all downstream analyses.

Although demultiplexing assigned the correct guide identity to each cell, we next sought to remove “false positives” whereby gRNAs were assigned but gene expression was unperturbed by evaluating the transcriptomes of gRNA clusters relative to scramble gRNAs. While successful CRISPR-KOs may not result in significant down-regulation of the targeted gene 76 gene, their overall transcriptomic profile should be distinct from scramble populations. To ensure that cells assigned to a guide-tag identity class demonstrated successful perturbation of the targeted ASD gene, we performed ‘weighted-nearest neighbor’ (WNN) analysis123 to assign clusters based on both guide-tag identity class and gene expression. To test that the transcriptome of these gRNA clusters were distinct form Scramble-gRNA control clusters we performed differential gene expression analysis (Wilcoxon Rank Sum) comparing each cluster to all other clusters. We then filtered non-targeting clusters and KO gRNA clusters by setting a quantile base average expression threshold of target genes based on the distribution of target gene average expression across all other clusters. Clusters were the collapsed by gRNA identity and gRNAs with less than 75 cells removed from analysis (SI Fig. 8A). These cells were then used for downstream differential gene-expression analyses124. For each cell-type individually, single-cell gene expression matrices were PseudoBulked using scuttle::aggregateAcrossCells function across lanes (4 pseudo-bulk samples per perturbation), lowly-expressed genes were removed (leaving 18–22,000 genes) followed by edgeR/limma differential gene expression analysis. Concordance between Wilcox-rank sum differential gene expression analysis using single-cell data and limma:voom using PseudoBulked data was assessed for each gene (SI Fig. 8D–E).

Meta-analysis of gene expression across perturbations43.

Across ASD KOs, DEGs were meta-analyzed (METAL125), and “convergent” genes were defined as those with significant and shared direction of effect across all ASD gene perturbations and with non-significant heterogeneity (FDR adjusted pmeta<0.05, Cochran’s heterogeneity Q-test pHet > 0.05). To test convergence between ASD-KOs, meta-analyses were performed across all possible combinations of 2–5 KO perturbations with and without sub-setting for those shared across cell types (>40,000 combinations across cell-types) (SI Fig 15C, SI Data 1).

Bayesian Bi-clustering to identify Convergent Networks43.

Across ASD KOs, convergent networks were generated by Bayesian bi-clustering126 and undirected gene coexpression network reconstruction from the ASD KOs. Not constrained by statistical cut-offs, and able to capture the effect of more lowly expressed genes, convergent networks may be a more sensitive measure of convergence. Networks were built based on bi-clustering (BicMix)127 using log2CPM expression data from all the replicates across each of the ASD gene sets and Scramble gRNA jointly. We performed 40 runs of BicMix on these data and the output from iteration 400 of the variational Expectation-Maximization algorithm was used. Target Specific Network reconstruction128 was performed to identify convergent networks across all possible combinations of the 9 ASD gene KO perturbations shared across cell-types (n=502 combinations/cell-type) and randomly sampled combinations of 2–21 KO perturbations without sub-setting for those shared across cell types (n=1400–2300 combinations) (SI Fig 15C).

Influence of Functional Similarity on Convergence Degree.

To test the influence of functional similarity and brain co-expression between KOs on convergence and compare the degree of convergence between the same KOs in different cell-types we established two methods for defining and measuring convergence. First, gene-level convergence using meta-analysis as described above, with the strength of convergence for each set defined as ratio of convergent genes to the average number of DEGs.

Second, network-level convergence based on undirected network reconstruction from Bayesian bi-clustering as described above. Bi-clustering identifies co-expressed genes shared across the downstream transcriptomic impacts of any given set of KO perturbations, thus, the resolved networks are the transcriptomic similarities between distinct perturbations (convergence). We calculated the “degree of convergence” for each network based on previously described metric43. Briefly, convergence scores are based on (1) network connectivity as defined by the sum of the clustering coefficient (Cp) and the difference in average length path (Lp) from the maximum average length path resolved across all possible sets [(max)Lp-Lp] and (2) similarity of network genes based on biological pathway membership scored by taking the sum of the mean semantic similarity scores 129 between all genes in the network and (3) minimum percent duplication rate across 40 runs. Duplication thresholds are network-dependent and a metric of confidence in the connections.

Functionally similarity scores across the ASD KO genes represented in each set was calculated using (1) Gene Ontology Semantic Similarity Scores: the average semantic similarity score based on Gene Ontology pathway membership within Biological Pathway (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF) (SI Fig. 1D) between ASD genes in a set129 and (2) brain expression correlation (BEC) score: based on the strength of the correlation in ASD gene expression in the CMC (n=991 after QC) post-mortem dorsa-lateral pre-frontal cortex (DLPFC) gene expression data,.

We performed Pearson’s correlation analysis (Holm’s adjusted P) on similarity scores and the degree of network convergence to determine the influence of the similarity of the initial KO genes on downstream convergence. We compared the average strength of convergence across cell-types using a parametric Welch’s F-test and pairwise Games-Howell test.

Enrichment analysis of convergence for risk loci using MAGMA.

We intersected cross cell-type perturbation specific and cross perturbation cell-type-specific gene-level convergence with genetic risk of eleven psychiatric and neurological disorders/traits [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)130, anorexia nervosa (AN)131, autism spectrum disorder (ASD)1, alcohol dependence (AUD)132, bipolar disorder (BIP)133, cannabis use disorder (CUD)134, major depressive disorder (MDD)135, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)136, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)137, and schizophrenia (SCZ)138, Cross Disorder (CxD)139, Alzheimer disease (AD)140, Parkinson disease (PD)141, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)142, Tourette’s143, migraine144, chronic pain145, and neurotic personality traits146 GWAS summary statistics] using multi-marker analysis of genomic annotation (MAGMA)74. SNPs were mapped to genes based on the corresponding build files for each GWAS summary dataset using the default method, snp-wise = mean (a test of the mean SNP association). A competitive gene set analysis was then used to test enrichment in genetic risk for a disorder across gene sets with an FDR<0.05.

Over-representation analysis, functional enrichment annotation, and biological theme comparison.

To identify pathway enrichments unique to individual KOs, we performed biological theme comparison and GSEA using ClusterProfiler129. Using FUMAGWAS: GENE2FUNC, the 102 ASD genes were functionally annotated and overrepresentation gene-set analysis for each convergent gene set was performed80. Using WebGestalt (WEB-based Gene SeT AnaLysis Toolkit)147, over-representation analysis (ORA) was performed on all convergent gene sets against publicly available genset lists GeneOntology, KEGG, DisGenNet and a curated gene list of rare-variant targets associated with ASD,SCZ, and ID60.

Random forest prediction model of convergence strength.

To determine how well functional similarity between KOs can predict gene-level and network-level convergence we trained a random forest model79 (randomForest package in R) for each type of convergence, evaluated the model in an independent internal dataset, and validated the model in an external CRISPRa activation screen43. Data from randomly tested gene combinations (2–5 KO sets at the gene level and 2–10 KO sets at the network level) tested across cell-types were randomly down-sampled into a training set (70%) and testing set (30%) – all with comparable proportions of data by cell-type (SI Fig 15). The random forest model was trained with bootstrap aggregation using C.C, M.F, B.P semantic similarity scores, brain expression correlation, number of genes, and cell-type as predictors. The Random Forest linear regression model was evaluated in the testing data by comparing actual values to predicted values, estimating the root mean squared error and performing Pearson’s correlations. Predictor models were validated using an external dataset of 10 CRISPR-activation perturbations of SCZ common variant target genes with multifunctional annotations broadly grouped as signaling/cell communication (CALN1, NAGA, FES, CLCN3, PLCL1) and epigenetic/regulatory (SF3B1, TMEM219, UBE2Q2L, ZNF804A, ZNF823)43, and assessed based the root mean squared error and Pearson’s correlation between actual and predicted convergence strength.

Behavioral phenotyping of ASD knockouts in zebrafish

We performed automated, high-throughput, quantitative behavioral profiling of larval zebrafish to measure arousal and sensorimotor processing as a readout of circuit-level deficits resulting from gene perturbation31. We quantified 24 parameters across sleep-wake activity and visual-startle responses in 15 stable homozygous or F0 CRISPant KO lines. Stable zebrafish line (ARID1B, ASH1L, CHD8, KDM5B, KMT2C, KMT5B, NRXN1) s were previously generated31,148; new CRISPant mutants (CHD2, KDM6B, MBD5, PHF12, PHF21A, SKI, SMARCC2, WAC) were generated according to149. We identified unique behavioral fingerprints for each ASD gene mutant, revealing convergent and divergent phenotypes across mutants. To classify convergent behavioral subgroups that may share circuit-level functions, we performed correlation analyses across mutants. We identified four distinct subgroups of ASD genes with highly correlated behavioral features (Fig. 6B).

Larvae were placed into individual wells of a 96 well plate containing 650 mL of standard embryo water per well within a Zebrabox. Locomotion was quantified with automated video-tracking system. The visual-startle assay was conducted at 5 days post fertilization (dpf). To assess larval responses to lights-off stimuli (VSR-OFF), larvae were acclimated to white light for 1 hour, and baseline activity was tracked for 30 minutes followed by five 1-second dark flashes with intermittent white light for 29 seconds. To evaluate larval responsivity to lights-on stimuli (VSR-ON), the assay was revered, where larvae were acclimated to darkness for 1 hour, and baseline activity was tracked for 30 minutes followed by five 1-second white light flashes with intermittent darkness for 29 seconds. For VSR-OFF and VSR-ON, six behavioral parameters were quantified using custom MATLAB code31: (i) average intensity of all startle responses, (ii) average post-stimulus activity (iii) average activity after first stimulus, (iv) stimulus versus post-stimulus activity, (v) intensity of responses to the first stimulus, (vi) intensity of responses to the final stimulus. The sleep-wake paradigm was executed between 5–7 dpf, following VSR-OFF and VSR-ON assays. During a 14h:10h white light:darkness cycle, larvae activity and sleep patterns were tracked within the Zebrabox and analyzed with custom MATLAB code31. Six behavioral parameters were quantified for daytime and nighttime: (i) total activity, (ii) total sleep, (iii) waking activity (iv) rest bouts (v) sleep length (vi) sleep latency. Across VSR-OFF, VSR-ON, and sleep-wake assays, we analyzed 24 parameters.

Linear mixed models (LMM) were used to compare phenotypes of each behavioral parameter between homozygous mutant versus wild-type or CRISPant versus scramble-injected fish for each gene of interest. Variations of behavioral phenotypes across experiments were accounted for by including the date of the experiment as a random effect in LMM. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to cluster mutants and behavioral parameters based on signed −log10-transformed p-values from LMM, where sign indicates direction of the difference in behavioral phenotype when comparing stable mutant to wild-type or CRISPant to scrambled-injected. Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess correlations between mutants based on the difference in the 24 parameters. Difference was evaluated using signed −log10-transformed p-values.

Drug screen for behavioral phenotyping in zebrafish