Abstract

In contemporary society, the increasing number of pet-owning households has significantly heightened interest in companion animal health, expanding the probiotics market aimed at enhancing pet well-being. Consequently, research into the gut microbiota of companion animals has gained momentum, however, ethical and societal challenges associated with experiments on intelligent and pain-sensitive animals necessitate alternative research methodologies to reduce reliance on live animal testing. To address this need, the Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model (FIMM) is being investigated as an in vitro tool designed to replicate gastrointestinal conditions of living animals, offering a means to study gut microbiota while minimizing animal experimentation. The FIMM system explored interactions between intestinal microbiota and probiotics within a simulated gut environment. Two strains of commercial probiotic bacteria, Enterococcus faecium IDCC 2102 and Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301, along with a newly isolated strain from domestic dogs, Lactobacillus acidophilus SLAM AK001, were introduced into the FIMM system with gut microbiota from a beagle model. Findings highlight the system’s capacity to mirror and modulate the gut environment, evidenced by an increase in beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Faecalibacterium and a decrease in the pathogen Clostridium. The study also verified the system’s ability to facilitate accurate interactions between probiotics and commensal bacteria, demonstrated by the production of short-chain fatty acids and bacterial metabolites, including amino acids and gamma-aminobutyric acid precursors. Thus, the results advocate for FIMM as an in vitro system that authentically simulates the intestinal environment, presenting a viable alternative for examining gut microbiota and metabolites in companion animals.

Keywords: in vitro culturomics, lactic acid bacteria, canines, Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model (FIMM), microbiome

Introduction

The gut microbiome, an intricate community of microorganisms inhabiting the gastrointestinal tracts of animals, exerts a profound influence on the health and well-being of its hosts. The critical role of the gut microbiome in human health has been well-documented, leading to a parallel increase in research focusing on the microbiological aspects of both industrial and domestic animal health (Lee et al., 2023; Song et al., 2023). This burgeoning field, situated at the intersection of microbiology and veterinary science, explores how dietary components, particularly probiotics, influence the gut microbiota, contributing to enhanced health and growth in animals (Lee et al., 2023; Quinn et al., 2015). The incorporation of probiotics into pet diets aims not only to maintain a balanced microbial ecosystem but also to enhance immune function and provide therapeutic benefits in various conditions, including gastrointestinal disorders and resistance to antibiotics. The rising awareness of these benefits has spurred a notable expansion in the probiotics market, tailored to meet the nutritional needs of companion animals, with a significant emphasis on gram-positive bacterial strains like Bacillus, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, and Streptococcus (Harel and Tang, 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Mugwanya et al., 2021).

Despite the valuable insights gained from animal-based microbiological research, such studies are fraught with ethical, logistical, and financial challenges (Lee et al., 2022; Mun et al., 2021). The ethical debate surrounding animal experimentation, especially with animals that exhibit high levels of intelligence and sensitivity to pain, underscores the necessity for humane and sustainable research methodologies. Additionally, the limitations inherent in animal models, particularly in their ability to accurately replicate complex human diseases or conditions, highlight the need for innovative research approaches that can offer reliable and ethically sound alternatives.

In response to these challenges, this study introduces the Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model (FIMM), an advanced in vitro tool engineered to replicate the physiological conditions of the animal gastrointestinal tract, including optimal pH, temperature, and resistance time. The FIMM system offers a distinctive platform for examining the interactions between probiotics and gut microbiota under controlled conditions, allowing for the exploration of these intricate relationships without the ethical and logistical complexities associated with live animal testing.

In this study, a meticulous selection of probiotic strains was employed to elucidate the operational dynamics of the FIMM system. Two commercial probiotic strains, Enterococcus faecium IDCC 2102 and Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301 (Kang et al., 2024), along with Lactobacillus acidophilus SLAM AK001 (Kang et al., 2022), a strain newly isolated from domestic dogs, were integrated into the FIMM system. This integration was performed alongside gut microbiota sourced from a laboratory beagle model, selected for its uniform living conditions, diet, and species consistency, which are crucial for minimizing experimental variability. The incorporation of diverse probiotic species aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the FIMM’s capability to simulate the canine gastrointestinal environment accurately. This approach is designed to not only test the system’s efficacy in replicating complex gut microbial interactions but also to evaluate the potential influence of these probiotics on the gut microbiota within a controlled, in vitro setting. Through this strategic selection of probiotic strains and a well-defined animal model, the study endeavors to enhance the precision and applicability of the FIMM, contributing valuable insights into the interplay between probiotics and gut microbiota, and ultimately facilitating the development of more targeted and effective strategies for animal health and nutrition.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial cultivation and study design

In this study, fecal samples were collected from domestic canines (n=3; Maltese and Jindo) aged between 6–8 years old. These samples were subsequently pooled for analysis. The strain L. acidophilus SLAM AK001 (LA), isolated from domestic canines, was identified in a prior investigation (Kang et al., 2022). Additionally commercial strains E. faecium IDCC 2102 and B. lactis IDCC 4301 were supplied by ILDONG Bioscience (Pyeongtaek, Korea). To culture these probiotic strains, de Man, Rogosa & Sharpe (MRS; BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) medium was utilized. The culturing process lasted 48 hours at a temperature of 37°C under aerobic conditions. The collection of samples and subsequent experimentation involving domestic canines and laboratory-raised beagles were carried out with the endorsement of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Chungnam National University (202109A-CNU-149).

Culturomic analysis

In this research, culturomic and metagenomic techniques were employed to identify prevalent lactic acid bacteria within the gut microbiota of domestic dogs, specifically Maltese and Jindo breeds (n=3), aged between 6 to 8 years. Fecal samples were meticulously collected, with 10 grams from each sample being aseptically transferred into a sample bag (3 M, St. Paul, MN, USA). Each sample was then diluted with 90 mL of 0.1% buffered peptone water (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) and subjected to homogenization by stomaching for two minutes at speed level 10. The resulting homogenate was serially diluted and inoculated onto various selective media, including MRS (BD Difco), phenylethyl alcohol agar (PEA; BD Difco), and Bifidobacterium selective agar (BS; BD Difco) plates, which were further enriched with 7.5% BactoTM Agar medium (BD Difco). These plates were incubated under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 48 hours to promote bacterial growth (Cho et al., 2022; Choi et al., 2016; Sornplang and Piyadeatsoontorn, 2016). The lactic acid bacteria isolated were then prepared for further experimental use, underpinning the study’s objective to explore the gut microbiota dynamics and probiotic interactions within the FIMM system.

Fermenter for Intestine Microbiota Model

The FIMM is an advanced in vitro system designed to simulate the canine gastrointestinal environment, facilitating detailed studies of gut microbiota interactions. This system was developed based on methodologies outlined in our previous study (Kang et al., 2022), and took inspiration from the well-established Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME) model (Van de Wiele et al., 2015). For the incubation of canine fecal samples within the FIMM system, pooled feces of laboratory raised beagles (n=6) were aseptically homogenized in filter bags using a stomacher (JumboMix, Interscience, Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche, France). Following homogenization, the supernatant was collected and introduced into the FIMM medium at a 10% inoculation rate. Concurrently, the selected probiotics—L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301—were inoculated to achieve a final concentration of 1% within the system. The FIMM medium employed in these experiments was based on a modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium (mGAM; HiMedia, Maarn, The Netherlands), recognized for its suitability in cultivating anaerobic bacteria (Javdan et al., 2020). To closely mimic the conditions of the canine gut, the medium’s pH was adjusted to 7.3, and the temperature was maintained at 38°C, aligning with the physiological parameters noted in canine intestinal research (Sagawa et al., 2009; Tochio et al., 2022). Through this meticulous replication of the canine gut environment, the FIMM system provides a robust platform for investigating the complex dynamics of gut microbiota and the impact of probiotics on gastrointestinal health.

Metagenomic analysis

After the FIMM incubation, the cultivates were collected, and genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 16S rRNA gene (Edgar, 2018), including the V4 region, was amplified, and the PCR product was sequenced using iSeq 100 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The amplicon primer sequences were as follows: 515F, TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTGCCAGCMGCCGCG GTAA; 806R, GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT for the 16S rRNA gene including the V4 region. The correlations and taxonomy of the obtained pair-end sequences were analyzed using Mothur v. 4.18.0 following the standard operating procedure suggested by the Schloss laboratory (Kozich et al., 2013; Son et al., 2021) and demonstrated using GraphPad Prism v. 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For the comparative analysis, the study utilized alpha diversity metrics, notably the Chao and Shannon indices, to reveal patterns of relative abundance across different groups. This approach provided a deeper understanding of microbial diversity. Additionally, Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) diagrams, based on both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances, were developed to illustrate the spatial distribution of the fecal microbiome samples.

Metabolomic analysis

The samples were cultivated in triplicate on FIMM medium before being separated into pellets for metagenomics analysis and supernatants for metabolite analysis. A PVDF syringe filter with a pore size of 0.2 m was used to filter the supernatants. Samples of 200 μL of the filtered supernatant were dried in a vacuum concentrator and kept at –81°C for GC-MS analysis. Derivatization of the extract involved 30 μL of 20 mg/mL methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 30°C for 90 min, followed by 50 μL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA; Sigma-Aldrich) at 60°C or 30 min. The internal standard fluoranthene was added to the extract. A Thermo Trace 1310 GC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Thermo ISQ LT single quadrupole mass spectrometer were used for GC-MS analysis. A 60-m DB-5MS column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 0.2-mm i.d. A 0.25-μm film thickness was utilized for separation. The sample was injected at 300°C with a 1:60 split ratio and 90 mL/min helium split flow for analysis. The metabolites were separated using 1.5 mL continuous flow helium in an oven ramp from 50°C (2 min hold) to 180°C (8 min hold) at 5°C/min, 210°C at 2.5°C/min, and 325°C (10 min hold) at 5°C/min. The mass spectra were obtained at 5 spectra per second from 35–650 m/z. Electron impact and 270°C ion source temperature were used in ionization mode. The metabolites were identified by comparing the mass spectra and retention indices of the NIST Mass spectral search tool (version 2.0, NIST, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with Thermo Xcalibur software’s automatic peak detection. The fluoranthene internal standard intensity standardized the metabolite data (Jung et al., 2023; Ku et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024; Muhizi et al., 2022).

Isolation of primary intestinal epithelial cells and adhesion assay

The experiment began with the retrieval of intestines, which were then placed in ice-cold HBSS devoid of Mg and Cl ions (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). These intestines underwent meticulous cleaning to eliminate mesenteric fat and external mucus. Subsequently, the duodenal tract was harvested, longitudinally opened, cut into 1–2 mm pieces, and rinsed in ice-cold HBSS. The prepared tissue pieces underwent a 30-minute digestion at 37°C using digestion medium. After the digestion process, the tissue was subjected to centrifugation at 100×g for 3 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in a 37°C washing medium. The resuspended pellet was subsequently filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer, followed by a second filtration using a 40 μm cell strainer in reverse. The aggregates recovered from the filtration were resuspended in basal medium. These aggregates were then diluted to a concentration of 0.8 mg/mL, with a density of 1,000 aggregates per well, and plated in 24-well plates coated with a Matrigel matrix (Corning, New York, NY, USA). The cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. During this time, the cell clusters were identified, and the degree of endothelial cell contamination was assessed. The cultures were meticulously washed with HBSS to eliminate unattached and dead cells, and any foci of proliferating enterocytes were replenished with fresh medium. Different growth factors were introduced at specific time points following seeding. For passaging, trypsin-EDTA was employed, and the cells were seeded into newly coated wells at a density of 3.5×105 cells per cm² (Ghiselli et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2022).

Before the adhesion assay, primary cell monolayers were washed 3 times with PBS to remove culture medium and nonattached cells. Bacterial strains were treated with medium without FBS and incubated at 37°C for 2 h in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 2 h, the monolayers were washed 5 times with PBS to remove the nonattached bacteria. The attached cells were lysed using trypsin-EDTA. Serial dilutions of the mixture were plated on MRS agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The adhesion ability was determined by counting colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG was used as a positive control.

Statistics

This study used triplicate data points, expressed as the mean±SD, and determined significant differences using Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA, and SigmaPlot 13 (GraphPad Software), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The abundance of metabolites of each sample was analyzed using the M2IA server (http://m2ia.met-bioinformatics.cn/) and MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca).

Results and Discussion

Metagenomic and culturomic analysis of domestic canines

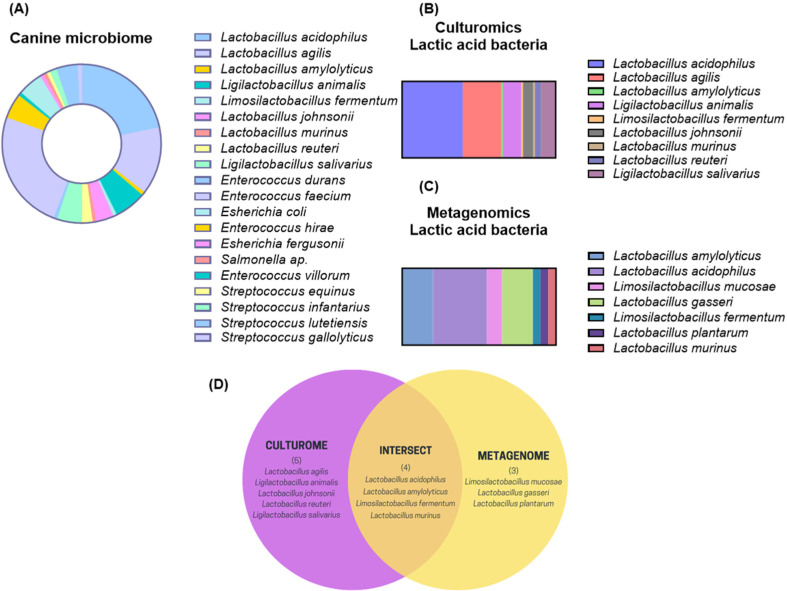

To identify prospective probiotic candidates that may be beneficial to canines, we compared the culture-dependent and culture-independent gut microbiota of domestic canines. In pursuit of practical insights in culturomic analysis, an assortment of 138 distinct lactic acid bacteria was collected from three distinct media types. These isolates belonged to twenty different species. Fig. 1A illustrates that the four predominant bacterial species were as follows: Enterococcus hirae (5.1%), L. acidophilus (21.7%), Lactobacillus agilis (13.8%), and Ligilactobacillus animalis (6.5%). We determined that the potential spectrum of probiotics should be restricted to Lactobacillus species, as they comprised the majority of the bacteria that were isolated (Figs. 1B and C). To achieve this, we monitored the number of Lactobacillus species that overlapped between the culturomic and metagenomics methodologies. As shown in a Venn diagram (Fig. 1D), four species of Lactobacillus (L. acidophilus, L. amylolyticus, L. fermentum, and L. murinus) were identified through both culturomic and metagenomics analyses. In light of this result, we sought to investigate what probiotic changes L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, which has the highest proportion, could make through FIMM incubation.

Fig. 1. The comparison of culturomic and metagenomic characterization of domestic canine fecal microbiota.

(A) This list presents the bacteria isolated from canine feces, utilizing the aforementioned medium. Subsequent to the isolation, the compositions specific to Lactobacillus were subjected to further examination employing (B) culturomic and (C) metagenomic analyses. (D) A Venn diagram elucidates the distribution of Lactobacillus species, categorized by those identified through culturomics (purple), metagenomics (yellow), and the species identified by both methods (orange).

Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model incubation increased the microbial diversity

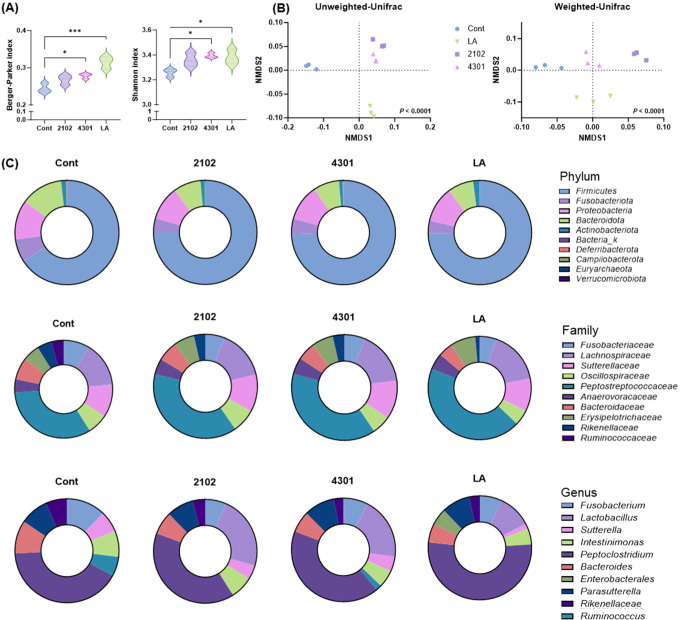

The study meticulously analyzed the effects of FIMM incubation on microbial diversity by integrating specific canine-derived probiotics, L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, and marketed probiotics, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301 were integrated into the FIMM system with fecal samples from laboratory-raised beagles to simulate the gut environment and assess the ensuing microbial alterations. Utilizing next-generation sequencing, the research identified a comprehensive array of 46,016 operational taxonomic units and 872 distinct taxonomic bacterial entities. Through the application of the alpha-diversity index, specifically the Chao and Shannon indices, a significant elevation in species diversity was observed (Chao and Shen, 2003). The Chao index revealed a 46.9±7.4% enhancement in mean species diversity attributable to the FIMM incubation, with an additional increase of 103.6±31.6% following probiotic supplementation. Concurrently, the Shannon index recorded a 23.83±5.1% rise in diversity post-FIMM incubation, and a further augmentation of 66.1±1.8% with the introduction of probiotics (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the diversified microbiota was found to be unique to each other according to the beta diversity analysis. Unweighted and weighted UniFrac used in beta diversity represent qualitative and quantitative variants, respectively. Each plot represents a relative abundance of species of a group, and the distance between the plots represents distinctiveness (Koleff et al., 2003). From our study, the beta diversity analysis, employing both unweighted and weighted UniFrac methods, illustrated distinctive microbial assemblages resulting from FIMM incubation relative to the control, and a unique microbial configuration associated with the probiotic intervention (Fig. 2B). These results highlight the FIMM system’s capability to not only enhance microbial diversity but also to cultivate specific microbial community contingent on the introduced probiotic strains.

Fig. 2. The diversity and richness of fecal microbiota was altered through FIMM incubation with probiotics.

The metagenomic analysis was utilized to elucidate the alterations in bacterial relative abundance subsequent to FIMM cultivation. Comparative analysis was conducted between FIMM cultivations subjected to probiotic interventions (LA, 2102, and 4301) and a control cohort devoid of any treatment (cont). (A) Indices of alpha diversity and (B) Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) diagrams were constructed to elucidate the spatial distribution of fecal microbiome samples. These diagrams plot individual samples, with axes representing the principal dimensions capturing the maximal variance in microbial community structure across the groups. (C) The comparative representation of bacterial relative abundance at phylum, family, and genus levels across all groups was meticulously quantified. All values are expressed as the mean±SD; significant differences were determined using Student’s t test and ANOVA compared to the cont at * p<0.05 and *** p<0.001. 2102, Enterococcus faecium IDCC 2102; 4301, Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301; LA, Lactobacillus acidophilus SLAM AK001; NMDS, non-metric multidimensional scaling; FIMM, Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

The supplementation with probiotics plays a pivotal role in enhancing the diversity of gut microbiota, a factor that is intrinsically linked to the overall health of the host. The gut microbiota’s diversity is crucial, starting with its fundamental role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients. The myriad of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract play a critical role in breaking down a broad spectrum of dietary fibers and nutrients, leading to enhanced nutrient uptake and improved digestive efficiency (Yu et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2023). This microbial diversity extends its benefits beyond digestion to bolster the immune system. It orchestrates a range of immune responses, strengthening the host’s defense mechanisms against opportunistic and pathogenic microbes. The balanced interplay among various microbial strains is also vital for regulating inflammatory processes, potentially reducing the incidence of inflammation-related disorders and supporting metabolic health and weight management (Kim et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Ritchie and Romanuk, 2012; Sánchez et al., 2017). The FIMM experiments provided insightful data, demonstrating that the in vitro fermentation process could enrich the diversity of bacterial strains within the canine gut microbiota. This enhancement closely mirrors the beneficial effects observed with probiotic consumption in vivo. The distinctive clustering patterns observed in the FIMM system, which varied with each bacterial strain, offer evidence of the system’s ability to foster specific interactions and associations within the microbial community. These findings underscore the potential of FIMM as a valuable model for exploring the intricate dynamics of gut microbiota and the impact of probiotics, offering a deeper understanding of how probiotic supplementation can modulate microbial ecosystems to support host health.

Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model incubation altered the microbial composition

The investigation into the impact of the FIMM incubation on microbial composition revealed significant alterations in the fecal microbiota, which might have been affected during sample collection. An in-depth examination of the 15 most abundant genera demonstrated that FIMM incubation induced notable changes in microbial composition. Specifically, when the FIMM system was supplemented with probiotics L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301, there was a substantial shift in microbial communities compared to the control group. Probiotics significantly increased the populations of Ruminococcus, Blautia, Dorea, and lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Faecalibacterium (Grześkowiak et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2022). These genera are recognized as beneficial commensal probiotics in canines. Concurrently, there was a reduction in the abundance of potential opportunistic pathogens, including Clostridium (Ghose, 2013), Streptococcus (Xu et al., 2007), and Prevotella (Larsen, 2017; Fig. 2C), showcasing the probiotics’ ability to modulate the gut microbiota favorably. Noteworthy is the observation that the microbial changes induced by L. acidophilus SLAM AK001 were in alignment with those noted in an in vivo canine model previously studied by our group (Kang et al., 2022, Kang et al., 2024), suggesting that this strain’s effects are consistent across different experimental settings. This consistency enhances the validation of the FIMM system as a reliable model for studying probiotic effects.

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Enterococcus are well-established probiotics. In a prior study, supplementation with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium was found to reduce Clostridium and increase commensal bacteria such as Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus in individuals with conditions such as diarrhea, inflammatory bowel diseases, and colorectal cancer (Alcon-Giner et al., 2020; Gerasimov et al., 2016; Lopez-Siles et al., 2017). While research in canines is relatively limited compared to human studies, the administration of E. faecium and Bifidobacterium in canines also resulted in an increase in Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Enterobacteriaceae while reducing the presence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Clostridium (Sabbioni et al., 2016; Vahjen and Männer, 2003). The FIMM cultivation method employed in this study mimics the probiotic effects of L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301, as observed in real-life scenarios where they are administered to mammals. This underscores the reliability of the FIMM in vitro cultivation system.

Overall, the FIMM system’s ability to mimic real-life probiotic effects in an in vitro setting underscores its potential as a valuable tool for exploring the intricate dynamics of gut microbiota and assessing the impacts of various probiotic strains on microbial communities. This system offers a promising avenue for advancing our understanding of probiotic interactions within the gut ecosystem, providing insights that could inform the development of targeted probiotic therapies for canines.

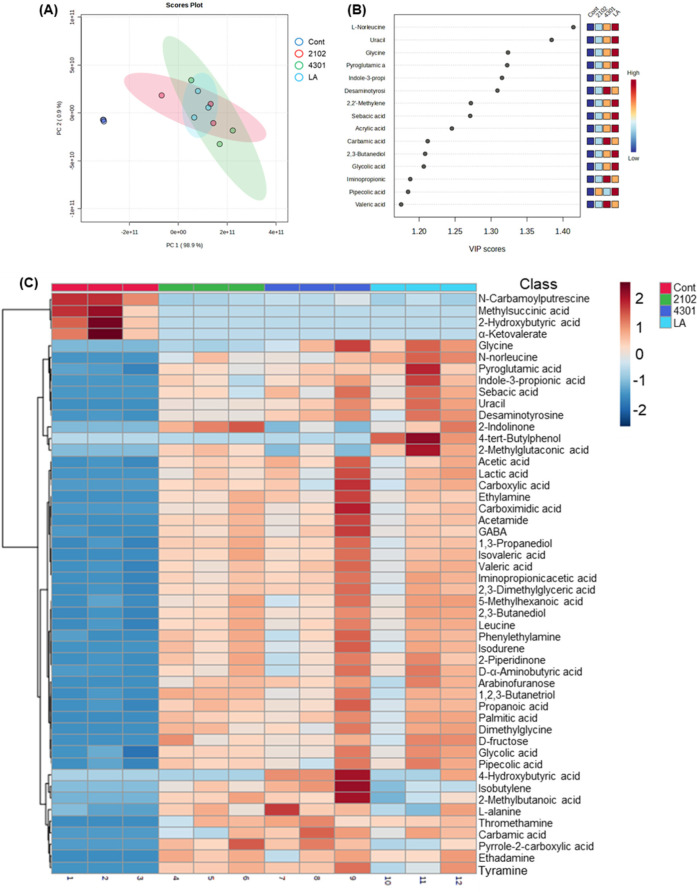

Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model incubation can imply changes in intestinal robustness

Additionally, the FIMM incubation process not only influenced the microbial composition but also significantly impacted the metabolic profile within the system, suggesting changes in intestinal robustness. Detailed metabolic analysis categorized nine distinct types of metabolites: alcohols, alkylamines, amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acids, indoles, lipids, nucleotides, organic acids, and others. Remarkably, compared to the control group, the introduction of probiotics led to an overall increase in these metabolites, with notable surges in amino acids and organic acids, including 4-hydroxybutyric acid, L-norleucine, and isovaleric acid. This metabolic enhancement, particularly in essential amino acids such as isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, and valine, underscores the broad-reaching impact of probiotics on metabolic processes. These amino acids are vital for protein synthesis across all living organisms, indicating a systemic effect of probiotic treatment on fundamental biological functions (Amorim Franco and Blanchard, 2017; Neis et al., 2015; Oh et al., 2021; Yoo et al., 2022). Organic acids, integral to primary metabolism, play pivotal roles in various biochemical pathways (Ramachandran et al., 2006; Sauer et al., 2008; Vasquez et al., 2022). The FIMM incubation results showed that probiotic administration could influence the production of key organic acids like propionic acid, acetic acid, and lactic acid (Fig. 3). These acids are crucial for numerous metabolic processes, including energy production and regulatory functions within the gut environment.

Fig. 3. Comparative analysis of unique metabolite production by probiotics in FIMM.

Following the FIMM cultivation, variations in metabolite profiles across different groups were examined. (A) In the PCA score plots, the analysis revealed that fecal samples from groups subjected to probiotic interventions (LA, 2102, and 4301) clustered together, indicating a shared metabolic response. In contrast, the control group was distinctly clustered, highlighting significant metabolic differentiation from the treated groups. (B) The partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) further analyzed these differences, identifying metabolites that drove the separation between treated and untreated groups. Additionally, the colored boxes in (B) and (C) categorized the top 50 abundant metabolites, with varying colors denoting concentration levels, offering an understanding of metabolite fluctuations resulting from FIMM cultivation and probiotic treatments. 2102, Enterococcus faecium IDCC 2102; 4301, Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301; LA, Lactobacillus acidophilus SLAM AK001; PC, principle component; VIP, variable importance plots; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; FIMM, Fermenter for Intestinal Microbiota Model; PCA, principle component analysis.

Bifidobacterium plays a significant role in the fermentation of dietary fibers and carbohydrates, resulting in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs offer various health benefits, including serving as an energy source for colonocytes, promoting gastrointestinal health, and exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties (Kim et al., 2022). Bifidobacterium, as a type of lactic acid bacteria, generates lactic acid as a metabolic byproduct, which contributes to the maintenance of an acidic gut environment, thereby restraining the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms (de Souza Oliveira et al., 2012; Pokusaeva et al., 2011). Moreover, select strains of Bifidobacterium have the capacity to synthesize gamma-aminobutyric acid, a neurotransmitter with potential anxiolytic and calming effects on the central nervous system (Duranti et al., 2020).

Likewise, E. faecium, another beneficial gut bacterium, also generates lactic acid as a predominant metabolic byproduct, reinforcing the acidic conditions of the gut, which can inhibit the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. In addition, E. faecium can participate in the production of various SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, each of which has multiple health advantages, particularly in the context of gut health. E. faecium is also involved in the digestion and metabolic breakdown of dietary proteins, giving rise to the production of diverse amino acids (Allameh et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020).

Finally, L. acidophilus primarily produces lactic acid as part of its metabolic processes, supporting the creation of an acidic gut environment that impedes the growth of detrimental bacteria and pathogens. While L. acidophilus SLAM AK001 may not be as widely recognized for its SCFA production as certain other bacterial strains, it does contribute to the production of SCFAs, particularly acetate and propionate (Chamberlain et al., 2022; Hossain et al., 2021). These findings underscore the significance of the metabolites generated within the FIMM cultivation system, demonstrating that the in vitro cultivation system provides the conditions necessary for proper metabolite production by different bacterial species.

The observed metabolic changes within the FIMM system, prompted by probiotic supplementation, mirror the potential enhancements in intestinal robustness and metabolic activity, which could have significant implications for gut health and overall organismal well-being. This insight into the metabolic alterations provides a deeper understanding of the multifaceted impacts of probiotics, extending beyond microbial diversity to include metabolic function, thereby offering a comprehensive view of the probiotic influence on the gut ecosystem.

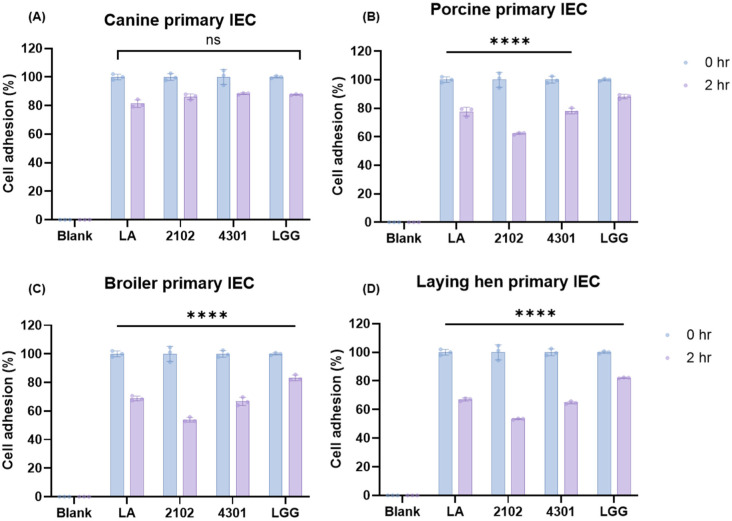

Probiotics for canines were very specific for canine primary intestinal epithelial cells

In the conclusive segment of the study, an in-depth evaluation was conducted to ascertain the host specificity of the lactic acid bacteria used, a factor that is paramount in determining their potential effectiveness as probiotics in canine hosts. Host specificity is a critical attribute that influences a bacterium’s ability to colonize and thrive within a specific host, impacting its probiotic efficacy and interaction with the host’s gut microbiome (Chaib De Mares et al., 2017; Dogi and Perdigón, 2006). To assess this, a series of host specificity tests were carried out using primary intestinal epithelial cells derived from a diverse array of species, including but not limited to dogs, chickens, laying hens, humans, and pigs. The aim was to investigate the cell adhesion capabilities of the probiotic strains, which is indicative of their potential to colonize and establish within the host’s gastrointestinal tract effectively. The study utilized the control strain, L. rhamnosus GG, known for its broad host specificity, as a comparative baseline, exhibiting an 88.3±0.7% specificity rate across various cell types. A significant affinity for primary intestinal epithelial cells sourced from canines was observed among the probiotic strains, an insight depicted in Fig. 4. This pronounced host specificity suggests these probiotics are well-suited for adherence and potential colonization within the canine gut. Specifically, L. acidophilus SLAM showcased the most substantial host specificity, with a rate of 81.3±2.7% when interacting with canine cells. Similarly, E. faecium IDCC 2102 and B. lactis IDCC 4301 exhibited host specificity rates of 86.2±1.9% and 88.3±0.6%, respectively, with canine cells (Fig. 4A). Notably, these strains maintained cell counts comparable to the original CFU before inoculation, underscoring their strong adherence capabilities to canine primary intestinal cell lines. Further analysis revealed that beyond canine cells, L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301 displayed host specificity rates of 74.5±6.2%, 64.4±13.4%, and 75.0±9.5%, respectively, towards other primary intestinal epithelial cells. A marked decrease in cell adhesion capacity was noted in avian primary enterocytes compared to the initial CFU counts, highlighting a more constrained host specificity in these cell types (Figs. 4B, C, and D). This detailed examination underlines the significant host specificity of canine-derived probiotics, positioning them as potent candidates for in-depth in vivo studies. Their targeted adherence to canine intestinal cells intimates that these probiotics may confer specific health benefits tailored to canines, underscoring their potential value in veterinary care and probiotic formulation development.

Fig. 4. Canine probiotics were highly selective to canine primary intestinal epithelial cells.

To investigate the host specificity of the probiotics, a cell adhesion assay was performed utilizing (A) canine primary intestinal epithelial cells, (B) porcine primary intestinal epithelial cells, and (C, D) avian primary intestinal epithelial cells. The assay determined host specificity by comparing the percentage of bacterial colony-forming units (CFUs) before and after a two-hour exposure to the seeded cells in 24-well plates. The blue bars in the graphical representation denote the CFU count of bacteria prior to exposure to each type of cell, while the purple bars indicate the CFU count of bacteria retrieved after the exposure. Each cell adhesion assay was conducted in triplicate wells. All values are expressed as the mean±SD; significant differences were determined using Student’s t test and ANOVA, with each treatment’s data at 2 hours compared to the baseline at 0 hour by **** p<0.0001. IEC, intestinal epithelial cells; LA, Lactobacillus acidophilus SLAM AK001; 2102, Enterococcus faecium IDCC 2102; 4301; Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301; LGG, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study was initiated with the objective of mitigating the limitations associated with microbial research in live animals while identifying potential probiotics beneficial for canines. Although animal studies are pivotal in scientific discovery and pharmaceutical advancements, they are fraught with ethical dilemmas and practical challenges. There’s a pronounced emphasis on animal welfare, emphasizing the reduction of animal distress and the pursuit of alternatives to circumvent the need for animal sacrifice, a subject of considerable ethical discourse. Yet, the development of in vitro methodologies capable of fully emulating the living conditions of organisms remains nascent, with a clear demand for further exploration and standardization in this domain.

Thus, the core ambition of this research was to introduce and validate a standardized in vitro cultivation approach, termed the FIMM system. This research effectively showcased the FIMM system’s capability to replicate the complex interactions between gut bacteria and their host, reflecting the dynamics observed when probiotics, specifically L. acidophilus SLAM AK001, E. faecium IDCC 2102, and B. lactis IDCC 4301, derived from canine fecal samples, were introduced into the system. To claim that the FIMM system perfectly emulates the canine gut microbiota system, it would have been ideal to administer these strains to actual canines and observe the resultant effects, a step that represents a limitation in this study. Nonetheless, the findings highlight the FIMM system’s efficacy as a potent tool for in-depth gut microbiota research, enhancing our comprehension of probiotics’ impacts on animal health. This advancement not only facilitates a more nuanced understanding of the gut microbiome but also opens avenues for developing targeted and efficacious probiotic interventions in veterinary practice.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Ildong Bioscience Co., Ltd. (2022) and the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant, funded by the Korean government (MEST) (NRF-2021R1A2C3011051) and by the support of the “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (RS-2023-00230754)” Rural Development Administration, Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Oh S, Kim Y. Data curation: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY, Song M, Kim MK, Kim JN, Yang J, Lee M, Oh S, Kim Y. Formal analysis: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY. Methodology: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY. Software: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY. Validation: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY, Song M, Kim MK, Kim JN, Yang J, Lee M, Oh S, Kim Y. Investigation: Oh S, Kim Y. Writing - original draft: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Oh S, Kim Y. Writing - review & editing: Kang A, Kwak MJ, Choi HJ, Son S, Lim S, Eor JY, Song M, Kim MK, Kim JN, Yang J, Lee M, Kang M, Oh S, Kim Y.

Ethics Approval

This animal experiment was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Chungnam National University (202109A-CNU-149).

References

- Alcon-Giner C, Dalby MJ, Caim S, Ketskemety J, Shaw A, Sim K, Lawson MAE, Kiu R, Leclaire C, Chalklen L, Kujawska M, Mitra S, Fardus-Reid F, Belteki G, McColl K, Swann JR, Simon Kroll J, Clarke P, Hall LJ. Microbiota supplementation with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus modifies the preterm infant gut microbiota and metabolome: An observational study. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100077. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allameh SK, Ringø E, Yusoff FM, Daud HM, Ideris A. Dietary supplement of Enterococcus faecalis on digestive enzyme activities, short‐chain fatty acid production, immune system response and disease resistance of javanese carp (Puntius gonionotus, bleeker 1850) Aquac Nutr. 2017;23:331–338. doi: 10.1111/anu.12397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim Franco TM, Blanchard JS. Bacterial branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis: Structures, mechanisms, and drugability. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5849–5865. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaib De Mares M, Sipkema D, Huang S, Bunk B, Overmann J, Van Elsas JD. Host specificity for bacterial, archaeal and fungal communities determined for high- and low-microbial abundance sponge species in two genera. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2560. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain M, O’Flaherty S, Cobián N, Barrangou R. Metabolomic analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. gasseri, L. Crispatus, and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus strains in the presence of pomegranate extract. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:863228. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.863228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A, Shen TJ. Nonparametric estimation of Shannon’s index of diversity when there are unseen species in sample. Environ Ecol Stat. 2003;10:429–443. doi: 10.1023/A:1026096204727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HW, Choi S, Seo K, Kim KH, Jeon JH, Kim CH, Lim S, Jeong S, Chun JL. Gut microbiota profiling in aged dogs after feeding pet food contained Hericium erinaceus. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:937–949. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Jin HY, Yang HS, Lee SC, Huh CK. Quality and storage characteristics of yogurt containing Lacobacillus sakei ALI033 and cinnamon ethanol extract. J Anim Sci Technol. 2016;58:16. doi: 10.1186/s40781-016-0098-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Oliveira RP, Perego P, de Oliveira MN, Converti A. Growth, organic acids profile and sugar metabolism of Bifidobacterium lactis in co-culture with Streptococcus thermophilus: The inulin effect. Food Res Int. 2012;48:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dogi CA, Perdigón G. Importance of the host specificity in the selection of probiotic bacteria. J Dairy Res. 2006;73:357–366. doi: 10.1017/S0022029906001993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranti S, Ruiz L, Lugli GA, Tames H, Milani C, Mancabelli L, Mancino W, Longhi G, Carnevali L, Sgoifo A, Margolles A, Ventura M, Ruas-Madiedo P, Turroni F. Bifidobacterium adolescentis as a key member of the human gut microbiota in the production of gaba. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14112. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70986-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Updating the 97% identity threshold for 16s ribosomal rna otus. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2371–2375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov SV, Ivantsiv VA, Bobryk LM, Tsitsura OO, Dedyshin LP, Guta NV, Yandyo BV. Role of short-term use of L. acidophilus DDS-1 and B. lactis UABLA-12 in acute respiratory infections in children: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:463–469. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselli F, Rossi B, Felici M, Parigi M, Tosi G, Fiorentini L, Massi P, Piva A, Grilli E. Isolation, culture, and characterization of chicken intestinal epithelial cells. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:12. doi: 10.1186/s12860-021-00349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose C. Clostridium difficile infection in the twenty-first century. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e62. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grześkowiak Ł, Endo A, Beasley S, Salminen S. Microbiota and probiotics in canine and feline welfare. Anaerobe. 2015;34:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel M, Tang Q. Protection and delivery of probiotics for use in foods. In: Sobel R, editor. In Microencapsulation in the food industry: A practical implementation guide. 2nd ed. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2023. (ed) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MI, Kim K, Mizan MFR, Toushik SH, Ashrafudoulla M, Roy PK, Nahar S, Jahid IK, Choi C, Park SH. Comprehensive molecular, probiotic, and quorum-sensing characterization of anti-listerial lactic acid bacteria, and application as bioprotective in a food (milk) model. J Dairy Sci. 2021;104:6516–6534. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-19034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javdan B, Lopez JG, Chankhamjon P, Lee YCJ, Hull R, Wu Q, Wang X, Chatterjee S, Donia MS. Personalized mapping of drug metabolism by the human gut microbiome. Cell. 2020;181:1661–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HY, Lee HJ, Lee HJ, Kim YY, Jo C. Exploring effects of organic selenium supplementation on pork loin: Se content, meat quality, antioxidant capacity, and metabolomic profiling during storage. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023 doi: 10.5187/jast.2023.e62. (in press). doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang A, Kwak MJ, Lee DJ, Lee JJ, Kim MK, Song M, Lee M, Yang J, Oh S, Kim Y. Dietary supplementation with probiotics promotes weight loss by reshaping the gut microbiome and energy metabolism in obese dogs. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12:e0255223. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02552-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang AN, Mun D, Ryu S, Lee JJ, Oh S, Kim MK, Song M, Oh S, Kim Y. Culturomic-, metagenomic-, and transcriptomic-based characterization of commensal lactic acid bacteria isolated from domestic dogs using Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for aging. J Anim Sci. 2022;100:skac323. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Kim JY, Kim H, Moon EC, Heo K, Shim JJ, Lee JL. Immunostimulatory effects of dairy probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. Lactis HY8002 and Lactobacillus plantarum HY7717. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:1117–1131. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Choi K, Ji Y, Holzapfel WH, Jeon MG. Anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus reuteri LM1071 via map kinase pathway in IL-1β-induced HT-29 cells. J Anim Sci Technol. 2020;62:864–874. doi: 10.5187/jast.2020.62.6.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleff P, Gaston KJ, Lennon JJ. Measuring beta diversity for presence–absence data. J Anim Ecol. 2003;72:367–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00710.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku MJ, Miguel MA, Kim SH, Jeong CD, Ramos SC, Son AR, Cho YI, Lee SS, Lee SS. Effects of Italian ryegrass silage-based total mixed ration on rumen fermentation, growth performance, blood metabolites, and bacterial communities of growing Hanwoo heifers. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023;65:951–970. doi: 10.5187/jast.2023.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JM. The immune response to prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology. 2017;151:363–374. doi: 10.1111/imm.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Goh TW, Kang MG, Choi HJ, Yeo SY, Yang J, Huh CS, Kim YY, Kim Y. Perspectives and advances in probiotics and the gut microbiome in companion animals. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:197–217. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim S, Kim ES, Keum GB, Doo H, Kwak J, Pandey S, Cho JH, Ryu S, Song M, Cho JH, Kim S, Kim HB. Comparative analysis of the pig gut microbiome associated with the pig growth performance. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023;65:856–864. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang K, Zhao L, Li Y, Li Z, Li C. Investigation of supplementation with a combination of fermented bean dregs and wheat bran for improving the growth performance of the sow. J Anim Sci Technol. 2024;66:295–309. doi: 10.5187/jast.2023.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tran DQ, Marc Rhoads J. Probiotics in disease prevention and treatment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58:S164–S179. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Siles M, Duncan SH, Jesús Garcia-Gil L, Martinez-Medina M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: From microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J. 2017;11:841–852. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks H, Grześkowiak Ł, Martinez-Vallespin B, Dietz H, Zentek J. Porcine and chicken intestinal epithelial cell models for screening phytogenic feed additives: Chances and limitations in use as alternatives to feeding trials. Microorganisms. 2022;10:629. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10030629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugwanya M, Dawood MAO, Kimera F, Sewilam H. Updating the role of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for tilapia aquaculture as leading candidates for food sustainability: A review. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2021;14:130–157. doi: 10.1007/s12602-021-09852-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhizi S, Cho S, Palanisamy T, Kim IH. Effect of dietary salicylic acid supplementation on performance and blood metabolites of sows and their litters. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:707–716. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun D, Kim H, Shin M, Ryu S, Song M, Oh S, Kim Y. Decoding the intestinal microbiota repertoire of sow and weaned pigs using culturomic and metagenomic approaches. J Anim Sci Technol. 2021;63:1423–1432. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neis EPJG, Dejong CHC, Rensen SS. The role of microbial amino acid metabolism in host metabolism. Nutrients. 2015;7:2930–2946. doi: 10.3390/nu7042930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JK, Vasquez R, Kim SH, Hwang IC, Song JH, Park JH, Kim IH, Kang DK. Multispecies probiotics alter fecal short-chain fatty acids and lactate levels in weaned pigs by modulating gut microbiota. J Anim Sci Technol. 2021;63:1142–1158. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokusaeva K, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Carbohydrate metabolism in bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr. 2011;6:285–306. doi: 10.1007/s12263-010-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PJ, Leonard FC, Markey BK, Fanning S, Fitzpatrick ES. Concise review of veterinary microbiology. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Fontanille P, Pandey A, Larroche C. Gluconic acid: Properties, applications and microbial production. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2006;44:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ML, Romanuk TN. A meta-analysis of probiotic efficacy for gastrointestinal diseases. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e34938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbioni A, Ferrario C, Milani C, Mancabelli L, Riccardi E, Di Ianni F, Beretti V, Superchi P, Ossiprandi MC. Modulation of the bifidobacterial communities of the dog microbiota by zeolite. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1491. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa K, Li F, Liese R, Sutton SC. Fed and fasted gastric pH and gastric residence time in conscious beagle dogs. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:2494–2500. doi: 10.1002/jps.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez B, Delgado S, Blanco-Míguez A, Lourenço A, Gueimonde M, Margolles A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61:1600240. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer M, Porro D, Mattanovich D, Branduardi P. Microbial production of organic acids: Expanding the markets. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S, Lee R, Park SM, Lee SH, Lee HK, Kim Y, Shin D. Complete genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus c5 as a potential canine probiotics. J Anim Sci Technol. 2021;63:1411–1422. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Lee J, Yoo Y, Oh H, Chang S, An J, Park S, Jeon K, Cho Y, Yoon Y, Cho J. Effects of probiotics on growth performance, intestinal morphology, intestinal microbiota weaning pig challenged with Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023 doi: 10.5187/jast.2023.e119. (in press). doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sornplang P, Piyadeatsoontorn S. Probiotic isolates from unconventional sources: A review. J Anim Sci Technol. 2016;58:26. doi: 10.1186/s40781-016-0108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tochio T, Makida R, Fujii T, Kadota Y, Takahashi M, Watanabe A, Funasaka K, Hirooka Y, Yasukawa A, Kawano K. The bacteriostatic effect of erythritol on canine periodontal disease–related bacteria. Pol J Vet Sci. 2022;25:75–82. doi: 10.24425/pjvs.2022.140843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahjen W, Männer K. The effect of a probiotic Enterococcus faecium product in diets of healthy dogs on bacteriological counts of Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and Clostridium spp. in faeces. Arch Anim Nutr. 2003;57:229–233. doi: 10.1080/0003942031000136657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Wiele T, Van den Abbeele P, Ossieur W, Possemiers S, Marzorati M. The simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem (SHIME®) In: Verhoeckx K, Cotter P, López-Expósito I, Kleiveland C, Lea T, Mackie A, Requena T, Swiatecka D, Wichers H, editors. In The impact of food bioactives on health: In vitro and ex vivo models. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2015. pp. 305–317. (ed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez R, Oh JK, Song JH, Kang DK. Gut microbiome-produced metabolites in pigs: A review on their biological functions and the influence of probiotics. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:671–695. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Cai H, Zhang A, Chen Z, Chang W, Liu G, Deng X, Bryden WL, Zheng A. Enterococcus faecium modulates the gut microbiota of broilers and enhances phosphorus absorption and utilization. Animals. 2020;10:1232. doi: 10.3390/ani10071232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Alves JM, Kitten T, Brown A, Chen Z, Ozaki LS, Manque P, Ge X, Serrano MG, Puiu D, Hendricks S, Wang Y, Chaplin MD, Akan D, Paik S, Peterson DL, Macrina FL, Buck GA. Genome of the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus sanguinis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3166–3175. doi: 10.1128/JB.01808-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J, Lee J, Zhang M, Mun D, Kang M, Yun B, Kim YA, Kim S, Oh S. Enhanced γ-aminobutyric acid and sialic acid in fermented deer antler velvet and immune promoting effects. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:166–182. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu DY, Oh SH, Kim IS, Kim GI, Kim JA, Moon YS, Jang JC, Lee SS, Jung JH, Park J, Cho KK. Intestinal microbial composition changes induced by Lactobacillus plantarum GBL 16, 17 fermented feed and intestinal immune homeostasis regulation in pigs. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022;64:1184–1198. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Zuo B, Li J, Zhai Y, Mudarra R. Effects of paraformic acid supplementation, as an antibiotic replacement, on growth performance, intestinal morphology and gut microbiota of nursery pigs. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023 doi: 10.5187/jast.2023.e95. (in press). doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]