Abstract

Following on from our pilot studies, this study aimed to test the efficacy of a combination of probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus), magnesium orotate and coenzyme 10 for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) through a double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial. The participants were 120 adults diagnosed with MDD randomised to daily oral administration, over 8 weeks, of either the intervention or placebo, with a 16-week follow-up period. Intent-to-treat analysis found a significantly lower frequency of the presence of a major depressive episode in the intervention group compared with placebo at the end of the 8-week treatment phase, with no difference between the two conditions at 8-week follow-up. Both the categorical and continuous measure of depressive symptoms showed a significant difference between the two conditions at 4 weeks, but not 8 and 16 weeks. The secondary end-point was demonstrated with an overall reduction in self-rated symptoms of anxiety and stress in the active treatment group compared with placebo. These findings suggest that the combination of probiotics, magnesium orotate and coenzyme 10 may be an effective treatment of MDD over an 8-week period.

Subject terms: Clinical microbiology, Psychology

Globally, major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the leading causes of disability1. Lifetime prevalence rates range between 10%2 and 20%3, with incidence rates surging worldwide during COVID-194. While treatment guidelines recommend antidepressant medication and psychotherapy standardised interventions for MDD5,6, these interventions have consistently shown only a small beneficial treatment effect compared with placebo7. Specifically, 37% of MDD patients who receive first-line pharmacological treatment do not achieve a response within 6 to 12 weeks, and 53% do not achieve remission8. Similarly, while 62% of MDD patients treated with psychotherapy no longer meet criteria for MDD after treatment, when compared with control conditions, psychotherapy only adds advantage to 19% of MDD patients9. In addition, adverse events can be high. For example, greater than a third of individuals taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression report adverse events10. Such findings indicate the need to explore alternative treatment options for MDD.

One promising alternative treatment for depression is the use of probiotics. However, while there is meta-analytic evidence to support the use of probiotics to reduce depressive symptoms in subclinical populations11, there have only been a small number of randomised clinical trials to determine the utility of probiotics for the treatment of MDD resulting in meta-analyses with mixed results12,13. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis examined 13 studies found that probiotics have a positive effect on depression, with a stronger effect size in clinical samples than community samples, although the authors noted the dearth of published studies using clinical samples14. Another recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated while many trials show positive outcomes there is considerable variability in the results and highlighted the need for more empirical research15. To date, most probiotic interventions for depression have included strains of the Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species of bacteria15,16. However, given the mixed findings for the treatment of MDD, there is a need for further exploration of effective probiotic formula for this condition. Our team has previously found promising results for the addition of magnesium orotate to a probiotic intervention for the treatment of MDD17. It has been proposed that magnesium orotate (Mg Orotate) may enhance the effectiveness of probiotic interventions by both a direct influence on intestinal peristaltic and metabolic functions as well as by modulating the gut microbiota18. As such the aim of this study was to extend our team’s previous published pilot work by investigating the efficacy of a combined therapy using magnesium orotate and probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus) in the management of MDD by means of a double blind RCT comparing NRGBiotic™ with a placebo. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) was included in the NRGBiotic™ formulation given that previous studies suggest that low levels of the coenzyme may have a role in the pathophysiology of depression and in particular in treatment resistant depression and chronic fatigue syndrome that can accompany depression19,20. Our hypotheses for this study are as follows.

Hypothesis 1:

The administration of Mg Orotate, CoQ10 and probiotics, over an 8-week period, will result in a greater reduction in the primary outcome measures (frequency of diagnosis of MDD and levels of self-rated depressive symptoms) compared with placebo at 8 weeks. In addition, we anticipate that these differences will be maintained at the subsequent 8-week follow-up period.

Hypothesis 2:

The administration of Mg Orotate, CoQ10 and probiotics, over an 8-week period, will result in greater changes in the secondary outcome measures (reduction in self-rated levels of anxiety and stress) compared with placebo at 8 weeks, and that these differences will be maintained at the subsequent 8-week follow-up period.

Methods

Study design

This was a 16-week double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial with two conditions (treatment and placebo). The trial was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee from the University of Queensland (UQ) (2017000186) and Queensland University of Technology (QUT) (1700001111) and was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials (ACTRN12617000419369) on the 23rd March 2017. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

Participants were over 18 years old with no upper limit, and a current diagnosis of MDD. The exclusion criteria included: (1) a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or current substance misuse disorder, (2) current high suicide risk, (3) current or recent use over the previous 4 weeks of antibiotics, (4) current use of Warfarin, (5) current pregnancy or planning pregnancy over 16 weeks, (6) serious physical illness (e.g., serious life threatening illness or palliative care), (7) current use of antidepressant medication other than SSRIs, or, SNRIs, 8) current or recent use over the previous 4 weeks of probiotics, (9) established or suspected obstructive/central sleep apnoea. Potential participants were also excluded if they were currently taking herbal remedies or medication on the exclusion list (see Supplementary Material A). The significant life events experienced by the participants are reported in Supplementary Material B.

Measures

Major depressive disorder

The presence of a MDD was assessed by a clinical psychologist using the research version of the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID-5-RV) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)7,21. The SCID’s diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for current MDD has been shown to be very good with good inter-rater reliability22.

Depressive symptoms

The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory—II (BDI-II)23. The BDI-II has been shown to have good validity and reliability24. The internal consistency was very good in this study (α = 0.88).

Anxiety symptoms

The severity of anxiety symptoms was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)25. The scale has been shown to have good criterion, construct, factorial, and procedural validity, as well as good internal consistency and test–retest reliability24. The internal consistency was good in this study (α = 0.80).

Stress symptoms

Self-report levels of stress were measured using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)26. The PSS has good factorial and criterion validity, good internal consistency, and adequate test–retest reliability26. The internal consistency was adequate in this study (α = 0.71).

Screening for personality disorders

Participants were also asked to complete the Standardized Assessment of Personality (SAPAS)—Abbreviated Scale. The SAPAS is an 8-item dichotomised (Yes/No) self-report screening measure. A score of 3/8 or higher is suggestive of a DSM-5 personality disorder27.

Participant dosage log

Adherence to the study protocol was recorded via documenting daily dosage. Any missed doses, changes to prescribed medication, or notable side effects were also recorded by the research team.

Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment into the trial. Participants completed three stages of screening. The first two stages were completed online and via a telephone interview to determine eligibility. At the final stage, a clinical psychologist administered the research version of the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID-5-RV) to confirm diagnosis of a MDD and obtain a diagnostic profile of current, past, and comorbid psychiatric disorders.

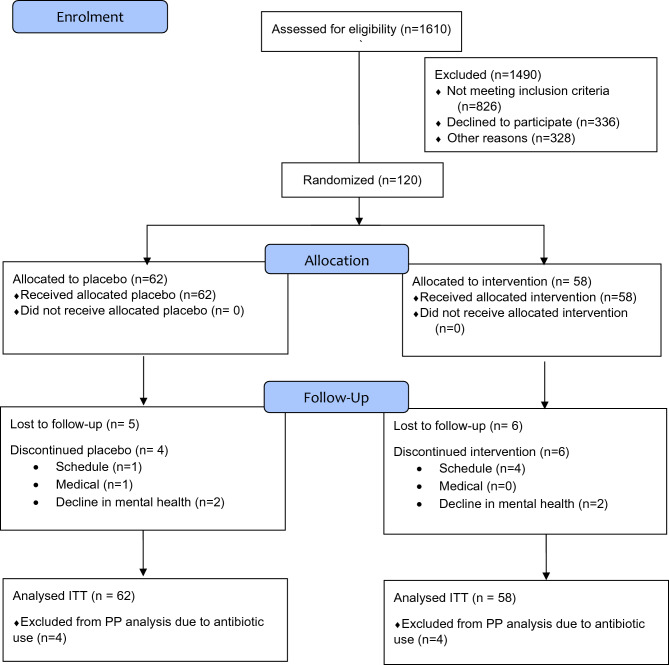

Of the 1610 participants initially assessed for eligibility, 120 participants met the criteria for the study and were randomly allocated to a treatment or placebo condition. The randomisation sequence was generated and stratified by gender (male, female, other) and medication class (no antidepressant, SSRI, SNRI) with a 1:1 allocation using random block sizes of 4 and 6. Participants who met criteria for the study had their details entered into Goji, a web-based trial management system developed at Queensland University of Technology, which utilised a fully automated process for randomisation. All research staff and participants were blinded to group allocation until data collection was completed. The active treatment and placebo capsules were stored separately in amber PET jars with white tamper-evident lids and labelled ‘A’ or ‘B’. Data was collected from the participants at the Queensland University of Technology’s Kelvin Grove Campus in Brisbane Australia. Data collection began July 2018 and ended in May 2020 due to a combination of meeting the minimum sample size required and COVID restrictions and lockdowns making further data collection unfeasible.

Participants were provided with 112 capsules divided evenly across two bottles and a paper dosage log to track adherence and report changes to physical or mental health symptoms, lifestyle, or medication. Participants were instructed to store the bottles in the fridge, administer four capsules daily (two morning and two evening doses with food) and begin administration on the evening of the baseline assessment. At the end of week 4 participants returned the study bottles and remaining capsules were counted and recorded. Participants were given two new bottles of product containing in total 112 capsules of the same condition and returned the remaining capsules at the end of week 8. Between weeks 8 and 16 the intervention ceased, and participants were advised to adhere to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the duration of this washout period. See Fig. 1 for Consort Flow Diagram. Financial incentives were provided at the screening assessment ($10) and baseline, week 4 and 8 assessments ($20 each). On completion of the week 16 assessment participants were posted one bottle of NRGbiotic™ and a $25 store voucher.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Study intervention and placebo

NRGBiotic™ is a combination of probiotics with Mg Orotate and CoQ10 (developed and supplied by Medlab Pty Ltd., Botany, NSW, Australia) and was the study intervention. Capsules contained a combination of lyophilized probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus) total CFU of 2 × 1010, Mg Orotate 1600 mg and CoQ10 150 mg. A pharmacist external to the research team developed the placebo in identical capsules to the NRGbiotic™. These capsules were matched for colour, size, taste, and smell, and consisted of lake carmoisine (red), exalake quinolone (yellow) and rice flour.

Statistical analysis plan

Baseline differences between the two groups on demographics and descriptive variables were checked using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical data. Chi-square analyses were run to compare the two groups on the number of participants meeting criteria for MDD post-intervention. Participants who no longer met the criteria for MDD were combined with those who had some subclinical features of MDD but did not meet all the criteria. In addition, chi-square analyses were used to compare the two groups on whether or not they reported at least mild symptoms of depression (i.e., BDI-II > 13). These analyses were conducted using SPSS v26.

The sample size calculation was based on Beck Depression Inventory pre and post scores from our pilot data using the same intervention17. The within-subject pooled standard deviation of the difference in responses from baseline to post-intervention was 21 units, and that alpha = 0.05. To identify a clinically important between-treatment difference of 5 units or greater on the BDI-II, with 80% power, we need to obtain complete outcome data on 115 individual participants. Assuming a notional dropout rate or difficulties in collecting later interval measurement data the recruitment target was expanded to at least n = 120 participants.Differences between the two groups in changes over time in the continuous measures of depression, anxiety, stress, and general wellbeing were tested separately using linear mixed models adjusted for baseline values of the relevant dependent variable. Models also included the group assigned (intervention vs placebo) and each follow-up time period (at week 4, 8 and 16) to allow for non-linear patterns. Two model forms were run: one with interactions between the group assigned and follow-up weeks, and one without interactions. Adjusting for antibiotic usage in the 12 months prior to the trial commencing was shown to not improve the model, so was not included. Robust standard errors were used to overcome any misspecification of residual structures.

These analyses were conducted with both intent-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses using Stata v16.0 (StataCorp, USA). The ITT analysis for the categorical data involved the last observation carried forward, whereas for the linear mixed models the 5 participants with no outcome data (i.e. no measurements at weeks 4, 8 and 16) could not be included. The PP analyses involved the removal of 8 participants (4 in the intervention group and 4 in the placebo group) who took antibiotics during the 8 week intervention period.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample as well as scores on the mental health questionnaires at baseline are reported in Tables 1 and 2. Compared with the participants in the placebo group, the participants in the intervention group were significantly older, experienced later age of onset of first major depressive episode (MDE), drank more caffeinated drinks per day, and had experienced a smaller number of previous psychological conditions. There were no other significant differences between groups for these variables.

Table 1.

Comparisons between conditions on continuous baseline variables, shown as mean(standard deviation).

| Continuous demographic | Placebo n = 62 | Intervention n = 58 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.76 (12.95) | 40.58 (13.39)* |

| BMI | 28.13 (6.90) | 29.01 (6.82) |

| Number of comorbid diagnoses | 1.58 (1.10) | 1.47 (1.21) |

| Number of past psych conditions | 0.89 (0.94) | 0.47 (0.66)** |

| Number of past suicide attempts | 0.26 (0.87) | 0.27 (0.57) |

| Number of subthreshold psych conditions | 0.24 (0.56) | 0.29 (0.59) |

| Age onset of first MDE | 17.60 (10.57) | 21.88 (12.96)* |

| Number of sig negative life events | 3.39 (1.45) | 3.84 (1.71) |

| Number of current stressors | 1.82 (1.00) | 1.64 (1.06) |

| Physical activity METS (in minutes) | 2455.15 (2558.04) | 2292.38 (2477.69) |

| Minute spending sitting during week | 373.75 (185.08) | 435.54 (228.04) |

| Global Sleep Score (PSQI) | 10.08 (3.17) | 10.00 (3.56) |

| Number of dysbiosis symptoms endorsed | 4.23 (2.01) | 4.24 (2.11) |

| Personality Disorder Score (SAPA) | 4.06 (1.69) | 4.16(1.67) |

| Standard drinks per day | 0.62 (1.00) | 0.72 (1.31) |

| Cigarettes per day | 0.75 (3.59) | 0.53 (2.36) |

| Caffeinated drinks per day | 1.73 (1.25) | 2.05 (1.54)** |

| Antidepressant dose (mg) | 81.00 (67.27) | 79.60 (15.41) |

| Number of weeks on current antidepressant dose | 81.91(108.26) | 183.14 (323.28) |

| Number of antibiotic prescriptions in last 12 months | 0.71 (.837) | 0.72 (1.06) |

| Depression (BDI-II) | 29.81 (10.35) | 30.78 (9.55) |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 10.95 (4.12) | 11.84 (4.96) |

| Stress (PSS) | 25.85 (4.81) | 27.12 (4.84) |

| Diet Energy (kilojoules) | 10,688.29 (8121.24) | 36,715.85 (212,707.34) |

| Diet Protein (grams) | 101.92 (37.92) | 163.96 (559.99) |

| Diet Total Fat (grams) | 98.43 (55.18) | 89.34 (28.93) |

| Diet Carbohydrates (grams) | 232.76 (109.90) | 641.85 (3296.20) |

| Diet Total Fibre (grams) | 23.19 (11.42) | 22.76 (12.17) |

Groups compared using t-tests.

*p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01.

Table 2.

Comparisons between conditions on baseline categorical demographics.

| Categorical demographic | Placebo n = 62 | Intervention n = 58 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 20 | 17 |

| Female | 41 | 40 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | |

| Relationship status | Married | 16 | 24 |

| De facto | 10 | 5 | |

| Divorced | 6 | 6 | |

| Dating | 12 | 5 | |

| Single | 17 | 18 | |

| Other | 1 | 0 | |

| Current antidepressant | None | 37 | 33 |

| SSRI | 15 | 17 | |

| SNRI | 10 | 8 | |

| Antibiotics in past 12 months | Yes | 32 | 26 |

| No | 30 | 32 | |

| Appendectomy | Yes | 4 | 9 |

| No | 58 | 49 | |

| Intestinal dysbiosis | Yes | 52 | 45 |

| No | 10 | 13 | |

| Previous suicide attempt | No | 49 | 39 |

| Yes | 9 | 10 | |

| Current use of analgesics | Yes | 12 | 13 |

| No | 50 | 45 | |

| Allergies | Yes | 33 | 26 |

| No | 29 | 32 | |

| Physical Activity | Inactive | 17 | 13 |

| Minimal | 26 | 26 | |

| Health enhancing | 19 | 17 | |

| Poor Sleep Quality | Yes | 55 | 52 |

| No | 1 | 4 | |

| History of nicotine use | No | 50 | 46 |

| Yes | 12 | 12 | |

| History of drug use | None | 50 | 44 |

| Cannabis | 7 | 8 | |

| MDMA | 0 | 1 | |

| More than one | 5 | 4 | |

Groups compared using chi-square tests; no significant differences were found.

Randomization

In addition to the minimal baseline differences between the two groups, successful randomisation was demonstrated by there being no difference between the two groups at week 4 on their belief as to whether they were in the probiotic or placebo group (χ2(2) = 4.76, p = 0.12). Similarly, the groups were equivalent in the frequency of participants experiencing a significant medical or life event during the trial (χ2(1) = 0.24, p = 0.63).

Adherence

There was no significant difference between the two groups on the number of capsules consumed during the 8 week trial (t(1, 103) = -0.49, p = 0.62 [placebo mean (SD) = 201.71 (23.79), probiotic mean (SD) = 204.48 (32.87)]. There were no significant differences between the two groups on any of the other adherence measures listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparisons between conditions on adherence variables during trial.

| Adherence variables | Placebo n = 62 | Intervention n = 58 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did participant commence, modify, or cease dose of antidepressant during trial? | No | 61 | 56 |

| Yes | 1 | 2 | |

| Medication (other than antidepressant) change during trial | No | 31 | 24 |

| Yes | 31 | 34 | |

| Did participant withdraw prior to completing trial? | No | 53 | 46 |

| Weeks 1–4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Weeks 5–8 | 3 | 4 | |

| Weeks 9–16 | 3 | 5 | |

| No | 55 | 53 | |

Groups compared using chi-square tests; no significant differences were found.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported after randomisation. Adverse events (AEs) were reported by participants daily to the clinical staff and were rated in terms of grade, attribution, and outcome and are presented in Supplementary Material C. The placebo group reported 13 adverse events while the intervention group reported 9 adverse events. Some patients experienced multiple AEs. Of the 22 AEs reported, 82% were mild, 18% were moderate and 0% were severe. All AEs were deemed to be possibly attributed to participation in the study. Fifty percent of the AEs were reported to be resolved during the study.

Changes in major depressive episode diagnosis

All participants met criteria for a current MDE at baseline as an inclusion-criteria for the study. At weeks 8 and 16, the participants were diagnosed as either meeting criteria for a current MDE, or not meeting criteria for MDE using the SCID-5-RV (see Table 4). Using ITT analysis, at week 8 the intervention group had a significantly lower rate of meeting the criteria for a current MDE than the placebo group (χ2 (df=1) = 3.91, p = 0.048) but there was no significant difference between the two groups at week 16 (χ2 (df=1) = 0.70, p = 0.40). However, using the PP analysis, there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of diagnosis at week 8 (χ2 (df=1) = 4.43, p = 0.11) nor at week 16 (χ2 (df=1) = 1.88, p = 0.39).

Table 4.

Comparisons between conditions on MDE criteria at week 8 and 16.

| Met criteria for MDE | Placebo | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 8 | Yes | 43 (2.0) | 30 (− 2.0) |

| No | 19 (− 2.0) | 28 (2.0) | |

| Week 16 | Yes | 47 (0.8) | 40 (− 0.8) |

| No | 15 (− 0.8) | 18 (0.8) | |

Note: Placebo n = 62, Intervention n = 58. Adjusted standardised residuals shown in brackets.

Changes in depressive symptoms

Changes in both categorical and continuous measures of depressive symptoms were examined. When the presence of symptoms of depression were dichotomised into either minimal symptoms (BDI-II < = 13) or at least mild symptoms of depression (BDI-II > 13), then the intervention group had fewer participants reporting the presence of depressive symptoms at week 4 (χ2 (df=1) = 4.40, p = 0.036). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups at week 8 (χ2 (df=1) = 2.42, p = 0.120) or at week 16 (χ2 (df=1) = 0.91, p = 0.763). See Table 5 for frequencies. The results did not change when using the PP analysis at week 4 (χ2 (df=1) = 3.91, p = 0.048), week 8 (χ2 (df=1) = 1.57, p = 0.210) or week 16 (χ2 (df=1) = 0.77, p = 0.781).

Table 5.

Comparisons between conditions on presence of depressive symptoms (BDI-II > 13).

| Presence of depressive Symptoms | Placebo | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | Yes | 43 (2.0) | 30 (− 2.0) |

| No | 19 (− 2.0) | 28 (2.0) | |

| Week 8 | Yes | 37 (1.3) | 28 (− 1.3) |

| No | 25 (− 1.3) | 30 (1.3) | |

| Week 16 | Yes | 40 (0.3) | 36 (− 0.3) |

| No | 22 (− 0.3) | 22 (0.3) |

Placebo group n = 62 Intervention group n = 58. Adjusted standardised residuals shown in brackets.

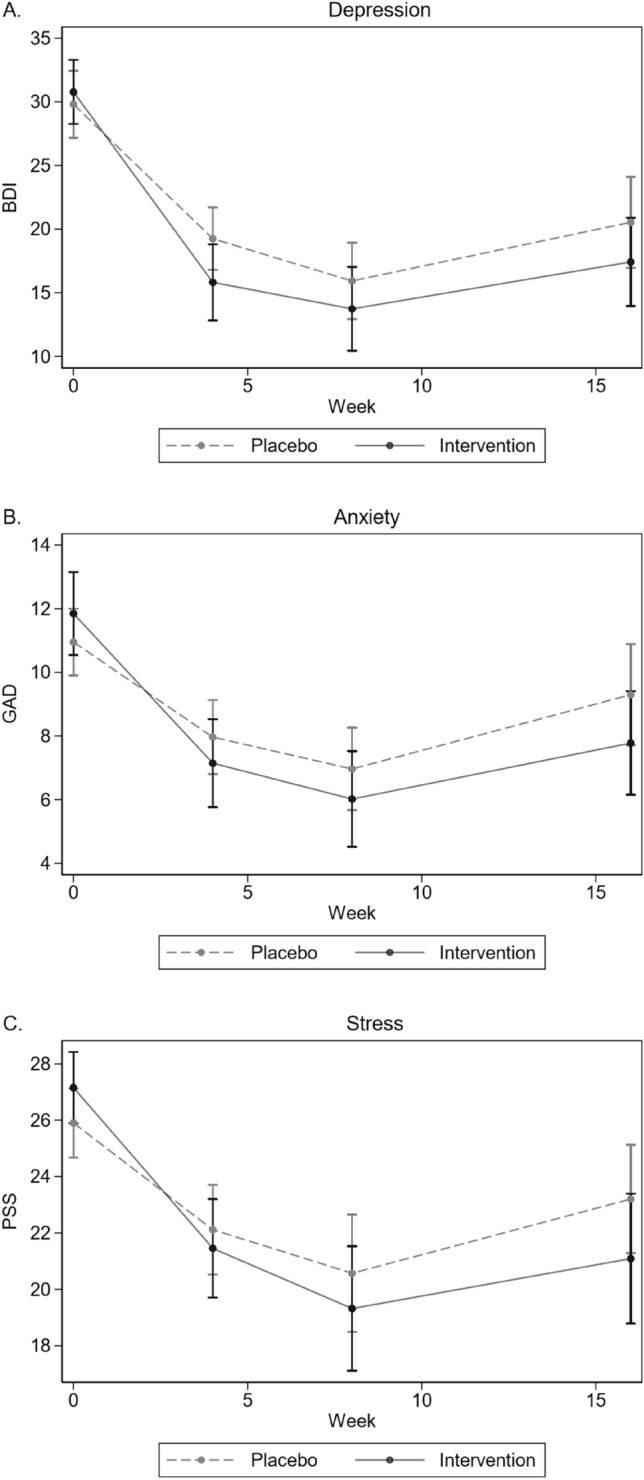

A similar pattern of results emerged when using the continuous measure of the BDI-II. Including all participants with at least a baseline measurement (n = 120), depressive symptoms reduced in both the placebo and intervention group within the first eight weeks of the trial, and the intervention group had consistently lower symptoms at all follow-up weeks (Fig. 2a). Nonetheless, using ITT modelled analysis (n = 115), the overall intervention effect of 3.3 BDI points below placebo on average over time was non-significant (Table 6, Fig. 2). At week 4 the intervention group was a significant 3.8 BDI points lower than the control group, but by week 8 this difference had reduced to 2.3 below and was non-significant. At week 16 this difference remained a non-significant 3.5 points lower (Table 6). The per protocol (PP) analysis (n = 108) was conducted by repeating the analysis after removing the eight participants who consumed antibiotics during the 8-week trial (note one of these participants also had no outcome measurements). Results were consistent in the PP analysis, except the overall effect was a significant 3.7 lower on average over time among the intervention group.

Fig. 2.

Changes in unadjusted depression scores (BDI-II) over time per group (Placebo n = 62; Intervention n = 58).

Table 6.

Modelled intervention versus placebo.

| d | ITT analysis (N = 115) | PP analysis (N = 108) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. [95% CI] | p-value | Coef. [95% CI] | p-value | |

| BDI | ||||

| Overall | − 3.26 [− 6.56, 0.04] | 0.053 | − 3.68 [− 7.11, − 0.24] | 0.036 |

| Week 4 | − 3.82 [− 7.41, − 0.24] | 0.037 | − 4.07 [− 7.79, − 0.35] | 0.032 |

| Week 8 | − 2.35 [− 6.38, 1.69] | 0.255 | − 2.62 [− 6.79, 1.55] | 0.218 |

| Week 16 | − 3.53 [− 7.92, 0.85] | 0.114 | − 4.36 [− 8.85, 0.14] | 0.057 |

| GAD | ||||

| Overall | − 1.41 [− 2.78, − 0.04] | 0.044 | − 1.63 [− 3.06, − 0.21] | 0.025 |

| Week 4 | − 1.30 [− 2.86, 0.25] | 0.101 | − 1.54 [− 3.09, 0.02] | 0.053 |

| Week 8 | − 1.20 [− 2.93, 0.52] | 0.171 | − 1.29 [− 3.04, 0.47] | 0.151 |

| Week 16 | − 1.76 [− 3.63, 0.12] | 0.066 | − 2.04 [− 3.97, − 0.11] | 0.039 |

| PSS | ||||

| Overall | − 2.18 [− 4.11, − 0.24] | 0.027 | − 2.08 [− 4.06, − 0.10] | 0.040 |

| Week 4 | − 1.72 [− 3.86, 0.41] | 0.113 | − 1.56 [− 3.73, 0.62] | 0.160 |

| Week 8 | − 2.05 [− 4.64, 0.54] | 0.121 | − 1.71 [− 4.33, 0.91] | 0.201 |

| Week 16 | − 2.89 [− 5.42, − 0.37] | 0.025 | − 3.12 [− 5.73, − 0.52] | 0.019 |

BDI Beck Depression Inventory II, GAD Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, Coef. coefficient and represents the modelled average difference between placebo and intervention groups.

Overall estimates obtained from models adjusted for baseline score and follow-up weeks. By follow-up week estimates obtained from models further including an interaction between intervention/placebo groups and follow-up weeks.

Changes in anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms reduced during the first 8 weeks of the trial for both the placebo and intervention group, and the intervention group had consistently lower symptoms at all follow-up weeks (Fig. 2b). While overall intervention effects on average over time were significantly lower (− 1.4 GAD-7 points) compared to placebo, under ITT there were no significant differences observed at week 4, 8 or 16 (Table 6). This differed from the per-protocol analyses which had a significantly lower GAD-7 score among the intervention group at week 16.

Changes in stress symptoms

Again, both the placebo and intervention group showed decreases in stress symptoms within the first eight weeks of the trial, with consistently lower symptoms at all follow-up weeks in the intervention group (Fig. 2c). Under both ITT (-2.2 PSS points) and per protocol analysis (-2.1 PSS), overall effects on average over time were significantly lower among the intervention group compared to placebo (Table 6). The only specific week with significantly lower estimates for the intervention group was in week 16.

Discussion

This study aimed to test the hypotheses that an eight-week intervention involving the daily administration of probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus), magnesium orotate and coenzyme Q10, would result in a significant reduction in the diagnosis of MDD and depressive symptoms, as well as in the secondary outcomes of symptoms of anxiety and stress, with gains being maintained over a subsequent 8-week follow-up period. The results of this study were mixed.

Using ITT analysis, the intervention group demonstrated a significant reduction in frequency of participants maintaining a diagnosis of MDD at 8 weeks compared to the placebo group. However, this difference was not maintained at the week 16 follow-up period indicating that the effect of the intervention was not sustained. The PP analysis found no significant difference between the two conditions in terms of frequency of diagnosis of MDD at 8 or 16 weeks—possibly due to the reduced sample size reducing the power of the analyses. Interestingly, both the categorical measure of the presence or absence of depressive symptoms, and the continuous measure of depressive symptoms (using the BDI-II), found a significant difference between the two conditions at week 4 but not at weeks 8 and 16, indicating that the strongest effect of the intervention may have occurred at week 4.

When considering the secondary outcome measures, both the ITT and PP analyses found an overall significant reduction in anxiety and stress symptoms in the intervention group compared with the placebo group across time. However, the strength of this effect was not strong enough to identify statistically significant differences between the two conditions at weeks 4, 8 and 16; with the exception of the intervention group reporting lower stress at week 16 (using both ITT and PP analyses) and lower anxiety at week 16 (using PP analyses) than the placebo group.

While our results are consistent with the majority of studies examining the effectiveness of probiotics upon depression and anxiety, a recent systematic review found that a third of studies included failed to find an effect which the authors attributed to the heterogeneity of strains included in the interventions28. It is of note therefore that the results of this study are consistent with a similar but smaller RCT by Nikolova et al., which examined effects of a probiotic supplementation adjunctive to antidepressant medication for participants with MDD29. This study is particularly interesting to compare results with given that it utilized a similar methodology, and while their intervention involved a wider range of strains of bacteria, it included the three strains of bacteria used in our intervention. Moreover, patients with depression appear to differentiate with healthy controls on the abundance of Streptococcaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae, while there is emerging evidence from intervention trials that changes in depressive symptoms may be associated with increase in the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium30.

While we postulate that the key active components of the intervention were the probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus), it is important to acknowledge that the Mg Orotate and CoQ10 may also have contributed to the effect identified in this study. We have previously demonstrated in an exploratory pilot study that magnesium orotate may have antidepressive actions31. Furthermore, in a second pilot study we demonstrated that the combination of Mg Orotate plus CoQ10 plus probiotics also showed efficacy in reducing major depression symptoms17. Therefore, given the results observed in our previous pilot studies we do acknowledge that the combination of compounds could have an add-on effect in improving major depression symptoms. We also note that other smaller studies have found an effect for probiotics without the inclusion of Mg Orotate and CoQ1029,30.

To-date, our study is the largest double-blind RCT to examine the efficacy of probiotics for the treatment of MDD. Given the small number of RCTs into probiotics and MDD and the mixed findings from current meta-analyses, the results of our study strengthen the literature that probiotic interventions can produce short term improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in adults with MDD. Moreover, our results indicate that the intervention group did not experience any significant AEs compared with the control group. However, given the effects upon depressive symptoms were not maintained at the week16 follow-up, our results also suggest a few possible reasons for the lack of maintenance that need to be investigated in future trials. First, it is possible that a dosage of 8 weeks is not long enough to support long term colonisation. Second, it is possible that colonisation may be improved by symbiotic intervention of both prebiotics and probiotics32. Third, it is possible that treatment with the probiotics may only be needed for the first 8 weeks, but that a longer dosage of magnesium orotate is needed to enhance its proposed effects upon the effectiveness of probiotis33. Fourth, given that adults with MDD with and without high levels of anxiety demonstrate differences in relative abundance of particular species of gut microbiota34, it is possible that the intervention had a differential impact upon the MDD participants with and without high anxiety.

While our study demonstrated significant reductions in depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms in our intervention group compared with placebo, there are limitations that affect the interpretation of the findings. First, the placebo group also experienced significant improvements on our mental health measures reducing the effect size between the intervention and control group. This, however, is consistent with the commonly observed strong placebo effect in RCTs trialling the efficacy of antidepressants for both depression35 and treatment resistant depression36. Another limitation of the study is rigorous exclusion criteria resulting in the exclusion of many potential participants. These exclusion criteria aimed to reduce the possible noise in the data from factors that could have potentially interfered with the effectiveness of the intervention. However, these strict exclusion criteria also limit the generalisability of the findings of this study and further effectiveness trials are warranted.

In conclusion, this study presents the findings from the largest randomised double blind control trial examining the effectiveness of a combination of probiotics and magnesium orotate for the treatment of MDD. Overall, the results indicate that compared with placebo, the intervention resulted in a significant short-term reduction in depression that was not maintained over an 8-weeks follow-up period. However, the significant reductions in comorbid anxiety and stress do generally appear to be maintained after the cessation of the probiotic supplement. While the results of this trial need to be replicated, they do provide evidence that a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus, Mg Orotate and CoQ10 may be a beneficial and safe treatment for MDD.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

The study was designed by MB, LV and ES. The study was implemented by SP and GR. Data was collected by SP, GR and ES. Data entry and cleaning was performed by SP and GR. Data analysis was conducted by GR, ES and SC. Data interpretation was performed by ES, SC, GR, MB, LV, and SP. The manuscript was written by ES and revised by LV, MB, SC, GR and SP. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

This study was funded by a grant from Medlab Clinical. LV was a previous employee of Medlab Clinical. All other authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Esben Strodl, Email: e.strodl@qut.edu.au.

Luis Vitetta, Email: luis.vitetta@sydney.edu.au.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-71093-z.

References

- 1.James, S. L. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet392(10159), 1789–1858 (2018). 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim, G. Y. et al. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep.8, 2861–2961 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasin, D. S. et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry75, 336–346 (2018). 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santomauro, D. F. et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet398(10312), 1700–1712 (2021). 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhi, G. S. et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Austr. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatry49(12), 1087–1206 (2015). 10.1177/0004867415617657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kendrick, T. et al. Management of depression in adults: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ20, 378 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gartlehner, G. et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for major depressive disorder: Review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open7(6), e014912 (2017). 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gartlehner, G. et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: An updated meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med.155(11), 772–785 (2011). 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuijpers, P. et al. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord.159, 118–126. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.026 (2014). 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cascade, E., Kalali, A. H. & Kennedy, S. H. Real-world data on SSRI antidepressant side effects. Psychiatry (Edgmont)6(2), 16 (2009). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musazadeh, V. et al. Probiotics as an effective therapeutic approach in alleviating depression symptoms: An umbrella meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.63(26), 8292–8300 (2023). 10.1080/10408398.2022.2051164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanada, K. et al. Gut microbiota and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord.266, 1–3 (2020). 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng, Q. X. et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on gut microbiota in patients with major depressive disorders: A systematic review. Nutrients15(6), 1351 (2023). 10.3390/nu15061351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, R. T., Walsh, R. F. L. & Sheehan, A. E. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry23(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12888-023-04685-w (2023).36593442 10.1186/s12888-023-04685-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, J. et al. The effect and safety of probiotics on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr.62(2), 1–19. 10.1007/s00394-022-02910-5 (2023). 10.1007/s00394-022-02910-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, L. et al. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: from pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine90, 104527 (2023). 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bambling, M., Edwards, S. C., Hall, S. & Vitetta, L. A combination of probiotics and magnesium orotate attenuate depression in a small SSRI resistant cohort: An intestinal anti-inflammatory response is suggested. Inflammopharmacology25(2), 271–274 (2017). 10.1007/s10787-017-0311-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiopu, C. et al. Magnesium orotate and the microbiome–gut–brain axis modulation: New approaches in psychological comorbidities of gastrointestinal functional disorders. Nutrients14(8), 1567 (2022). 10.3390/nu14081567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maes, M. et al. Lower plasma Coenzyme Q 10 in depression: A marker for treatment resistance and chronic fatigue in depression and a risk factor to cardiovascular disorder in that illness. Neuroendocrinol. Lett.30(4), 462–469 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majmasanaye, M., Mehrpooya, M., Amiri, H. & Eshraghi, A. Discovering the potential value of coenzyme Q10 as an adjuvant treatment in patients with depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.44(3), 232–239 (2024). 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.First, M.B., Williams, J.B., Karg, R.S., Spitzer, R.L. American Psychiatric Association. Arlington. VA, American Psychiatric Association. (2015).

- 22.Osório, F. L. et al. Clinical validity and intrarater and test–retest reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5–Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci.73(12), 754–760 (2019). 10.1111/pcn.12931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. Beck Depression Inventory–II [Internet]. PsycTESTS Dataset (American Psychological Association (APA), 1996). 10.1037/t00742-000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, Y. P. & Gorenstein, C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Braz. J. Psychiatry35(4), 416–431 (2013). 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. [Internet]166(10), 1092. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006). 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. [Internet]24(4), 385. 10.2307/2136404 (1983). 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran, P. et al. Standardised Assessment of Personality—Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): Preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry [Internet]183(3), 228–32. 10.1192/bjp.183.3.228 (2003). 10.1192/bjp.183.3.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mörkl, S., Butler, M. I., Holl, A., Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Probiotics and their impact on the gut-brain axis with a focus on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials from 2014 to 2023. Microorganisms11(4), 1–20. 10.3390/microorganisms11040085 (2023). 10.3390/microorganisms11040085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikolova, Y. S., Worry, K. & Hayes, R. Effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms and emotional cognition: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry80(7), 677–685. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.1817 (2023). 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.1817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alli, S. R. et al. The gut microbiome in depression and potential benefit of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics: A systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23(9), 4494 (2022). 10.3390/ijms23094494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bambling, M., Edwards, S. C., Coulson, S. & Vitetta, L. S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) and Magnesium Orotate as adjunctives to SSRIs in sub-optimal treatment response of depression in adults; a pilot study. Adv. Integr. Med.2, 56–62 (2015). 10.1016/j.aimed.2015.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.You, S. et al. The promotion mechanism of prebiotics for probiotics: A review. Front. Nutr.9, 1000517 (2022). 10.3389/fnut.2022.1000517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitetta, L., Bambling, M. & Strodl, E. Probiotics and commensal bacteria metabolites trigger epigenetic changes in the gut and influence beneficial mood dispositions. Microorganisms11(5), 1334 (2023). 10.3390/microorganisms11051334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritchie, G. et al. An exploratory study of the gut microbiota in major depression with anxious distress. J. Affect. Disord.320, 595–604 (2023). 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rief, W. et al. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J. Affect. Disord.118(1–3), 1–8 (2009). 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones, B. D. et al. Magnitude of the placebo response across treatment modalities used for treatment-resistant depression in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open4(9), e2125531 (2021). 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.