Abstract

Eradication of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is therapeutically challenging; many patients succumb to AML despite initially responding to conventional treatments. Here, we showed that the imipridone ONC213 elicits potent antileukemia activity in a subset of AML cell lines and primary patient samples, particularly in leukemia stem cells, while producing negligible toxicity in normal hematopoietic cells. ONC213 suppressed mitochondrial respiration and elevated alpha-ketoglutarate by suppressing alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) activity. Deletion of OGDH, which encodes α-KGDH, suppressed AML fitness and impaired oxidative phosphorylation, highlighting the key role for α-KGDH inhibition in ONC213-induced death. ONC213 treatment induced a unique mitochondrial stress response and suppressed de novo protein synthesis in AML cells. Additionally, ONC213 reduced translation of MCL-1, which contributed to ONC213-induced apoptosis. Importantly, a patient-derived xenograft from a relapsed AML patient was sensitivity to ONC213 in vivo. Collectively these findings support further development of ONC213 for treating AML.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common adult and second-most common pediatric acute leukemia (1). For >40 years, the standard care for AML was an intensive regimen of cytarabine and anthracycline-based chemotherapy. This regimen has produced a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 30% for adults (2). The U.S. FDA has approved new therapies for patients with AML (e.g., glasdegib, venetoclax), but overall survival remains disappointing. To improve long-term survival of patients, new less toxic and efficacious drugs aiming at AML vulnerabilities are needed.

The imipridone family of compounds have shown efficacy with reduced toxicity in AML therapy (3). One member, ONC201, is a TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) inducing agent effective against solid tumors (4). In Phase I and II clinical trials, ONC201 had good safety and efficacy (5). Subsequent studies indicated that ONC201 also activated the mitochondrial serine protease ClpP to elicit death (5–7). Refinement of imipridones resulted in a second generation of these agents. Among them is ONC213, having greater potency than ONC201 (8). We found in biological systems that ONC213 has a mechanism that is distinct from ONC201. ONC213 displays low toxicity to normal hematopoietic cells and is broadly efficacious against leukemia progenitor cells, leukemia stem cells (LSCs), and orthotopic murine models of human AML. We show through biochemistry and genetic studies that alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH, coding gene is OGDH) inhibition is coupled with mitochondrial respiratory suppression and that loss of OGDH sensitized AML cells to ONC213.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

MV4–11, U937, THP-1, HL-60 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA), OCI-AML3, ML-2 (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany), MOLM-13 (AddexBio, San Diego, CA, USA), and CTS (gift from Dr. A Fuse, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) cell lines were cultured as described (9, 10). The cell lines were authenticated at the Genomics Core at Karmanos Cancer Institute using the PowerPlex® 16 System from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Monthly mycoplasma testing was performed using the PCR method (11).

Clinical Samples

Diagnostic bone marrow blast samples, obtained from the First Hospital of Jilin University, were purified by standard Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation, then cultured as described (12). Normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were donated by healthy individuals. Written informed consent was provided, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Jilin University. Patient characteristics are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Normal human CD34+ hematopoietic cells with >90% viability and 95% purity were purchased from Novo Biotechnology (Beijing, China).

Drugs

ONC213, ONC201, and ONC212 were provided by Chimerix, Inc. (Durham, NC, USA). Z-VAD-FMK was purchased from AbMole (Houston, TX, USA). Cycloheximide and ISRIB were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. MG132 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA).

MTT Assays

MTT (3-[4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl]-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich) assays were performed as previously described (13, 14).

Annexin V-FITC/PI Staining and Flow Cytometry

Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate/propidium iodide (FITC/PI) staining (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and flow cytometry analyses were performed as described (13, 15). AML cell line experiments were performed three times in triplicate independently. Primary patient sample and normal PBMC experiments were preformed once in triplicate due to limited sample. Apoptotic events are shown as the mean percentage of Annexin V+/PI- (early apoptotic) and Annexin V+/PI+ (late apoptotic and/or dead) cells ± the SEM from one representative experiment.

Western Blot

Western blots were performed as previously described (16). Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Fisher Inc., Rockford, IL, USA), and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies (see Supplementary Data for details). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Seahorse Analysis

Cellular oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured using a Seahorse XFe24 flux analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), as described (17).

Mitochondrial Fractionation

Mitochondria were isolated using the Mitochondria Extraction Kit (Solarbio Science & Technology), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described (18).

RNAseq

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNAseq analyses were performed as described (17). Differentially expressed mRNA were identified at a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.05 and fold-change ≥ 2. GO and Pathway enrichment analysis were performed based on the differentially expressed mRNAs. The RNAseq data has been deposited into GEO (accession #: GSE137249).

Targeted Metabolomics

Metabolites were extracted using 80% methanol, cellular concentrations of metabolites (normalized to cellular proteins) were quantitatively determined using an LC-MS/MS based targeted metabolomics platform, and data analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst (www.MetaboAnalyst.ca, version 4.0), as described (12, 19). Differences in metabolites among the control and treatment groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Fisher’s least-significant differences post hoc analysis. An FDR < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Puromycin Pulse Labeling Assay

Cells were treated with indicated drugs for 8 (MV4–11) or 16 h (THP-1), after which the cells were treated with 1 μM puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Cells were pelleted at 1000 × g for 5 min, washed in cold PBS, and lysed by sonication in M-Per lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 1X protease inhibitor cocktail. Thirty μg of protein of each sample was analyzed by western blot using mouse anti-puromycin antibody (1:1000, clone 12D10, EMD Biosciences). For controls, cells were prepared without puromycin treatment or with 30-min preincubation with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide prior to puromycin labeling.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific), cDNAs were prepared using random hexamer primers and a RT-PCR kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), as described (9, 15, 16, 20). Transcripts were quantitated using TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a LightCycler 480 real-time PCR machine (Roche Diagnostics), based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold changes were calculated using the comparative Ct method (21). Results are normalized to GAPDH transcripts and presented as means from three independent experiments.

MCL-1 Overexpression and BAK/BAX Double Knockdown

Lentivirus production and transduction were carried out as previously described (22). The pMD-VSV-G and delta 8.2 plasmids were gifts from Dr. Dong (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA). RFP and MCL-1 cDNA lentiviral constructs were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). Non-template negative control (NTC)-, BAX-, and BAK-shRNA lentiviral constructs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Colony Formation Assay

Colony formation assays were carried out as described (10, 23, 24). Briefly, cells were treated with ONC213 (48 h), washed thrice with PBS, plated in MethoCult (catalog number 04434; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and incubated for 10–14 days. Colonies containing >50 cells were counted. Colony formation assays using mouse lineage-negative Mycn-transduced HPCs were performed as described (25). Mycn-transduced cells were plated in Methocult M3434 (Stem Cell Technologies) and incubated for six days with indicated concentrations of ONC213 (MC1). The colonies were counted (duplicates), and the cells from the vehicle treated plates were harvested. These cells were then replated in M3434 with or without ONC213 and cultured for another 6 days (MC2). The colonies were counted and replated for MC3.

Engraftment of Primary AML Cells Treated with ONC213 Ex Vivo

Primary AML cells were treated ex vivo, washed, and then 1×107 cells were injected into the tail vein of female B-NDG (NOD-Prkdcscid IL2rgtm1/Bcgen; Biocytogen, Beijing, China) mice (n=5). Twelve weeks later, bone marrow (BM) cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for human CD45+ cells. These mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the School of Life Sciences, Jilin University, Changchun, China. This experiment was approved by the Animal Research Committee at School of Life Sciences, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

Genetic Dependency Data

The OGDH dependency data were obtained from the Public 22Q4 dataset that contains dependency data from 1078 cancer cell lines covering 27 lineages (https://depmap.org/portal/). The Chronos scores from myeloid and lymphoid cancers and other cancers were plotted.

Leukemia Xenograft Model

Eight-week-old immunocompromised triple transgenic NSG-SGM3 female mice (NSGS, JAX#103062; non-obese diabetic SCID gamma (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg(CMV-IL3, CSF2, KITLG)1Eav/MloySzJ (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor ME, USA) were injected intravenously with MV4–11 cells (1×106 cells/mouse; 0.2 mL/inj.; Day 0). On Day 3, mice were randomized (5 mice/group) into the following groups: vehicle control, 75 mg/kg ONC213 daily by p.o., and 125 mg/kg ONC213 daily by p.o. in the vehicle [3% ethanol (200 proof), 1% Tween-80 (polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monooleate) and sterile water; all USP grade; v/v]. Mice were treated daily for 8 days. The 75 mg/kg ONC213 group was given 2 days off and treated for an additional 8 days (total of 16 days). Body weight and condition were assessed 1–2 times a day for the duration of study. Experimental endpoints and efficacy response were determined for each group based on median day for developing leukemic symptoms (hindleg weakness, >15% weight loss, metastatic spread to internal organs).

PDX model J000106565 was purchased from Jackson Laboratory. This model is positive for FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD, and NPM1 mutations, classified as AML M4/M5, and the patient had undergone induction chemotherapy with consolidation high-dose cytarabine and allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J000106565 cells were passaged in NSGS female mice and spleens were harvested from mice at the time of euthanasia. J000106565 cells were isolated from splenic tissue, resuspended in sterile PBS and confirmed to be human AML cells by staining for hCD45 and detection via flow cytometry. Cells were injected into the tail-vein of NSGS female mice (1×106 cells/mouse, n = 5). Human cell engraftment was verified in mice 23 days later with flow cytometry for hCD45+ cells in their peripheral blood (submandibular vein) and randomized into vehicle control or ONC213 (65–75 mg/kg, p.o., daily) group. Mice were monitored daily for weight changes, signs of leukemia, or signs of toxicity during the duration of treatment. Treatment was halted at the first signs of leukemia (hindleg weakness, >5–10% weight loss, ruffled fur), and they were thereon monitored twice daily for progressing signs of leukemia. On day 36, peripheral blood was collected (submandibular vein). Cells were stained with hCD45, hCD34, hCD38 (Beckman Coulter), and hCD123 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

All mice were provided food and water ad libitum, given supportive fluids and supplements as needed, and housed within an AAALAC-accredited animal facility with 24/7 veterinary care. These in vivo experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wayne State University.

Gene Expression Database Screening and Analysis

Log2 RMA-normalized CCLE data were downloaded from GSE36133 (26, 27). The plotPCA function from DESeq2 was used for principal component analysis (28). The pheatmap function from the pheatmap R package was used to generate heatmaps (29). Unsupervised pathway activity was assessed using gene set variation analysis (30). Hallmark OXPHOS and glycolysis gene sets were used from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) to define their respective pathways (31, 32).

Mitochondrial Enzyme Activity Assays

Citrate synthase activity was measured, as previously described (33), with modifications. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.5% β-dodecyl maltoside). Respiratory enzyme activity assays were performed according to Spinazzi et al. (34), with some modifications. Cells were lysed by sonication in PBS, and then resuspended in 0.5% β-dodecyl maltoside. Bovine heart mitochondria were used as a positive control. NADH dehydrogenase (Complex I) and succinate dehydrogenase (Complex II) were assayed by following the reduction of 2,6 dichlorophenoindophenol (DCPIP; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) at 600 nM. The specificity of the succinate dehydrogenase assay was confirmed by testing with 1 mM 2-thenoyltrifluoroactone. Calculations for complexes I and II were done using an extinction coefficient of 21 mM−1cm−1 for DCPIP. Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically by following the changes in cytochrome c absorbance after the sample was added. The decrease of absorbance at 550 nm was measured for 1 min. Cytochrome c oxidase activity was calculated using an extinction coefficient of 19.6 mM−1cm−1 for reduction/oxidation of cytochrome c. For each treatment condition, equal volumes of freshly prepared MV4–11 lysate, corresponding to 2 million cells, were added to each well of a 96-well plate. Three replicate data points and controls were prepared for each treatment. Substrate, 1.5 μl of α-ketoglutarate (1 M, pH 7.4 in water) was added to the lysates, the volume brought to 150 μl with Reaction Buffer, and were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then developed after the addition of 50 μl of freshly prepared Developer Buffer, incubated for 5 min to allow color to develop before reading at 500 nm. Controls without α-ketoglutarate, but otherwise identical, were subtracted as background and activities were calculated as nmol NADH formed per min per mg protein. The α-KGDH activity was normalized by citrate synthase activity and normalized to the untreated control in each experiment. For additional details, see Supplementary Data.

OGDH Knockdown

OGDH-edited pooled MV4–11 cells were generated by CAGE core facility at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. In brief, the cells were transfected with an OGDH-specific gRNA (TGTCGAGGTCAGACTCATCCNGG) using nucleofection. The cells were expanded, and the gene editing was verified by next generation sequencing. The pooled cells were then exposed to the indicated concentrations of ONC213 for 72 h. Genomic DNA was collected from these cells and analyzed for the presence of deletion at the gene locus where the gRNA targeted.

Mitochondrial ROS

Invitrogen MitoSox Red Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicator was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide production. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle for 8 h, or 250 nM ONC213 for 8, 4, or 2 h, or with 50 uM antimycin A for 15 minutes, as a positive control. Cells were stained with 5 uM MitoSox for 30 minutes, washed with PBS, resuspended in 2% FBS in PBS, and MitoSox fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Geometric mean was graphed and calculated using FlowJo version 10.8.1.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between treatment groups and/or untreated cells were compared by unpaired two-sample t-test, unless otherwise noted above. Overall survival probability was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Error bars represent mean ± SEM; Significance level was set at P<0.05.

Data Availability

The RNAseq data has been deposited into GEO (accession #: GSE137249). The metabolomics data are available within the article and its supplementary data files. The data analyzed in this study were obtained from CCLE at www.broadinstitute.org/ccle (GSE36133) and depmap at https://depmap.org/portal/ (Public 22Q4 dataset). All other data reported in this paper are available within the article or will be provided upon request to either Yubin Ge (gey@karmanos.org) or John Schuetz (john.schuetz@stjude.org).

Results

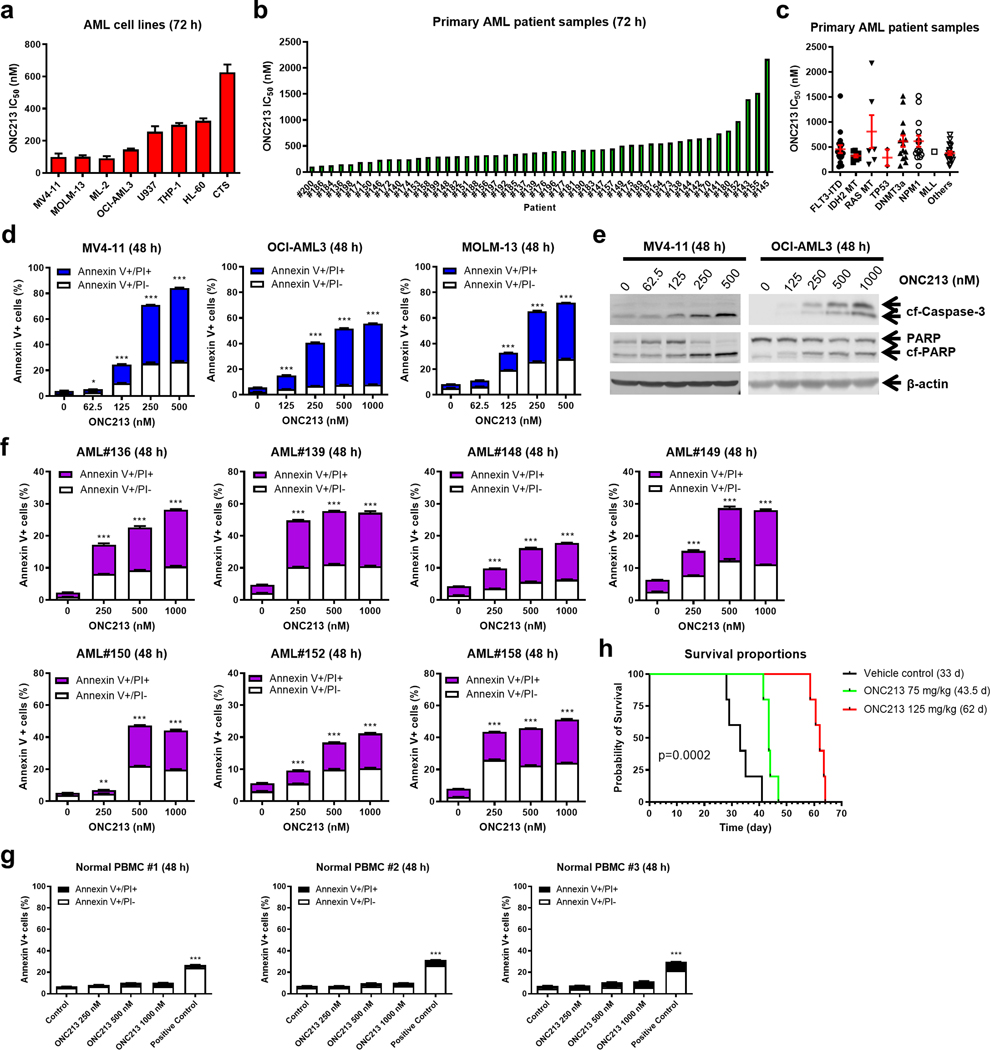

ONC213 Decreases Viable AML Cells but Induces Cell Death in a Case-Specific Fashion

To study the activity of ONC213 against AML cells, we used AML cell lines with various FAB subtypes and genetic lesions (Supplemental Table S2). MTT assays showed a 7-fold range of ONC213 IC50, from 91.7–626.0 nM (Fig. 1a; Supplemental Fig. S1a). Known genetic lesions in AML cell lines do not appear to be associated with ONC213 sensitivity. Primary AML patient samples showed a similar range of ONC213 sensitivities (n=48; 106.0–2173.0 nM; median IC50=374.2 nM; 20.5-fold range; Fig. 1b; Supplemental Fig. S1b; Supplemental Table S1), which also appeared independent of AML subtypes (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. ONC213 shows potent in vitro and in vivo antileukemic activity against AML cell lines and primary patient samples.

a. AML cell lines (n=8) were treated with variable concentrations of ONC213 for 72 h. Viable cells were determined using the MTT assay. IC50s were calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Data are graphed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. b&c. Primary AML patient samples (n=48) were treated with variable concentrations of ONC213 for 72 h. Viable cells were determined using the MTT assay. IC50s were calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Data are graphed as mean ± SEM in panel c. The data presented are means of duplicates from one experiment due to limited sample availability. d&e. MV4–11, OCI-AML3, and MOLM-13 cell lines were treated with ONC213 for 48 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and western blot, respectively. Mean percent Annexin V+/PI- and Annexin V+/PI+ cells ± SEM are shown. * P<0.05; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control (panel d). Representative western blots of whole cell lysates probed with the indicated antibodies are shown (panel e). Abbreviations: cf-PARP, cleaved PARP; cf-Caspase 3, cleaved Caspase-3. f. Primary AML patient samples (n=7) were treated with ONC213 for 48 h. Annexin V-FITC/PI staining was assessed by flow cytometry analysis. Mean percent Annexin V+/PI- and Annexin V+/PI+ cells ± SEM are shown. *** P< 0.001 compared to vehicle control. g. PBMCs from healthy donars were treated with ONC213 for 48 h. Annexin V-FITC/PI staining was assessed by flow cytometry analysis. Mean percent Annexin V+/PI- and Annexin V+/PI+ cells ± SEM are shown. h. MV4–11 cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) were injected intravenously through the tail vein of immunocompromised NSGS mice. Three days later, the mice were randomized (n=5 mice/group) and treated daily with vehicle control (3% 200-proof ethanol, 1% polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monooleate, and USP water), 75 mg/kg ONC213 by p.o., or 125 mg/kg ONC213 by p.o. The mice were treated for 8 consecutive days. The 75 mg/kg ONC213 group was given 2 days off and then treated for another 8 days. The overall survival probability was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

ONC213-treated MV4–11, OCI-AML3, and MOLM-13 cells showed concentration-dependent increases in apoptotic/dead cells, accompanied by cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP (Fig. 1d–e). However, several ONC213-treated cell lines (U937, THP-1, CTS, and HL-60) showed only small changes in Annexin V+ cells (Supplemental Fig. S1c). Primary AML patient cells showed a similar dichotomy (Fig. 1f; Supplemental Fig. S1d). In contrast, none of the PBMCs from healthy controls (n=3) showed apoptosis post ONC213 treatment (up to 1000 nM) for 48 hours (Fig. 1g).

Cell Death Induced by ONC213 Appears Independent of TRAIL and DR5

Unlike ONC201, which has multiple mechanisms of cell killing (4), ONC213-treated cells showed no evidence for induction of either TRAIL or death receptor 5 (DR5). ONC213 treatment also had no effect on AKT phosphorylation (Supplemental Fig. S1e–f). This is in marked contrast to ONC201 which substantially reduces AKT-phosphorylation in AML cells (35). These results indicate that ONC213-induced AML cell death is distinct from ONC201 in that it is not associated with either TRAIL and/or DR5 induction.

Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of ONC213 in AML Xenograft Mouse Models

The pharmacokinetic profile of ONC213 in BALB/c mice treated with one oral dose of 50 mg/kg showed a half-life of 4.4 h, Tmax=0.5 h, and maximum plasma concentration of 1882.5 μg/L (3.77 μM) (Supplemental Fig. S1g–h). Using MV4–11 cells which harbor FLT3-ITD, a high-risk and difficult-to-treat AML subtype, the in vivo efficacy of ONC213 was tested (Supplemental Fig. S1i–j). Mice received either 75 mg/kg, but showed almost no weight loss, or 125 mg/kg and exhibited a transient but completely reversible weight loss (Supplemental Fig. S1k). Necropsy indicated that all deaths were due to leukemia with no evidence of death due to drug induced toxicity. In this AML xenograft model, the low ONC213 dose (75 mg/kg) increased median survival to 43.5 days from 33 days (32% increase in lifespan). Importantly, the 125 mg/kg dose nearly doubled survival from 33 to 62 days (88% increase in lifespan) (Fig. 1h) which establishes ONC213 efficacy in vivo.

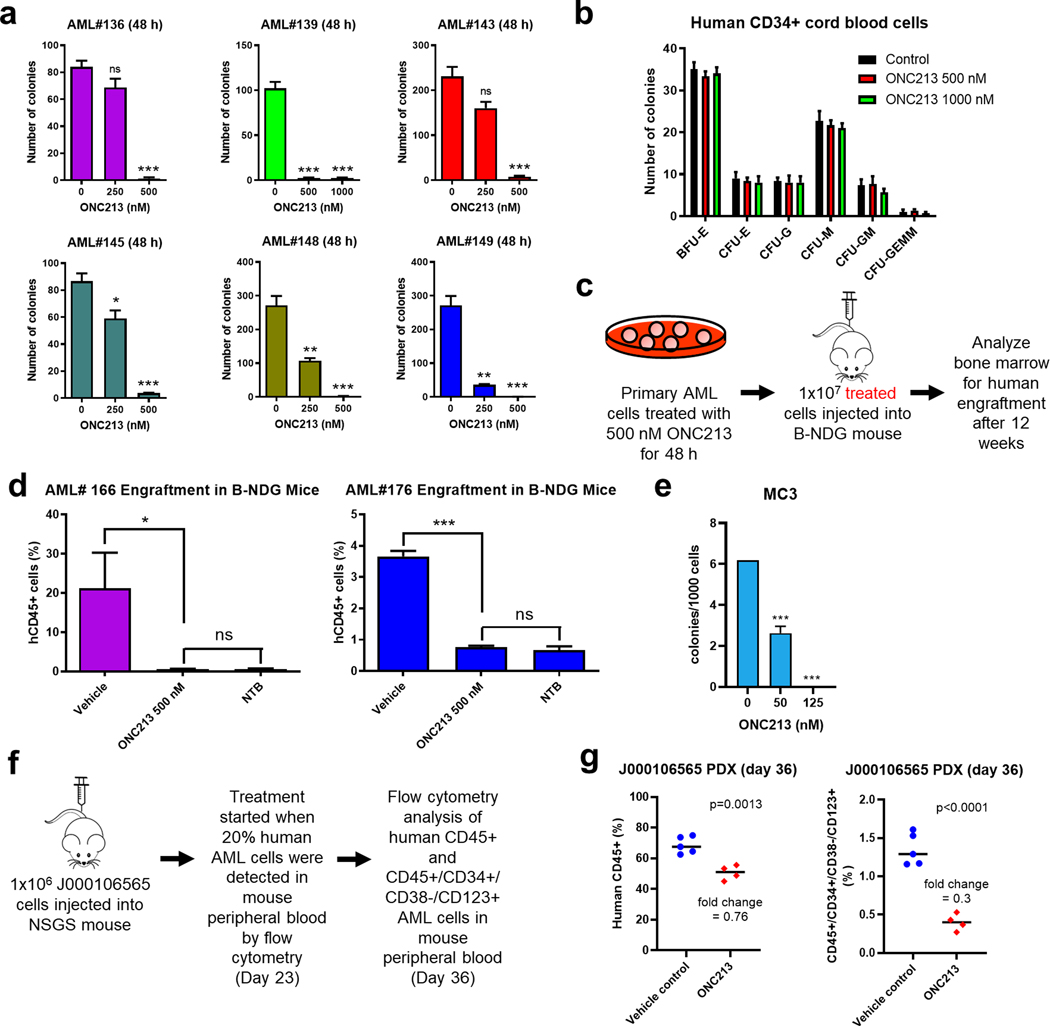

ONC213 Has Potent Cytotoxic Effects on AML Progenitor and Stem Cells

We next used AML patient samples (n=6) to assess if ONC213 effected colony formation using methylcellulose culture to determine impact on leukemic stem cells (36). 250 nM ONC213 treatment strongly reduced clonogenicity in some samples, with the variation in colony number survival likely related to the number of initial leukemic progenitors present in the samples. At 500 nM, ONC213 strongly suppressed colony numbers to less than 5% for all primary AML samples tested compared to vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 2a). This effect on colony formation contrasts with the Annexin V/PI data (Fig. 1f and Supplemental Fig. S1d). This discrepancy likely is due to differences between these assays. Importantly, ONC213 treatment (up to 1000 nM) had no significant effect on clonogenicity of normal human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. ONC213 has potent activity against leukemia progenitor cells and leukemia-initiating stem cells.

a. Primary AML samples from patients were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 48 h and then plated in methylcellulose. After incubation for 10–14 days, the number of surviving AML cells capable of generating leukemia colonies (AML-CFUs) were enumerated. Technical triplicates were performed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control. b. Normal human CD34+ cord blood cells were maintained in culture with vehicle or ONC213 for 48 h and then plated in methylcellulose. After incubation for 10–14 days, the number of surviving HPCs capable of generating leukemia colonies were enumerated. The number of BFU-E, CFU-E, CFU-G, CFU-M, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM colonies are presented as mean ± SEM. c&d. Scheme of experimental set-up is shown in panel c. Primary AML samples from patients (AML#166 and AML#176) were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 48 h in vitro and then injected into B-NDG mice (5 mice/group). Human AML BM engraftment was quantified by measuring human CD45+ cells via flow cytometry. NTB indicates nontumor-bearing mice. ns, not significant compared to NTB; * P<0.05 and *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control. e. Mouse lineage-negative hematopoietic cells were transduced with Mycn-containing retrovirus. The sorted cells were plated in M3434 methylcelluose media containing indicated concentration of ONC213. Resulting colonies were counted after 6 days, which reflect the number of myeloid progenitors. The vehicle treated cells were then harvested and replated in the presence or absence of ONC213 for MC2 and MC3 to determine the number of leukemia initiating cells that survive. Mycn-induced transformation occurs at MC3 (vec transduced cells do not replate past MC2), and ONC showed selective toxicity at this stage. f-g. J000106565 cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) were injected intravenously through the tail vein of immunocompromised NSGS mice to generate a patient-derived xenograft model. Human cell engraftment was verified in three randomly selected mice 23 days later by flow cytometry for hCD45+ cells in their peripheral blood (average 20.23%). The mice were randomized (n=5 mice/group) and treated daily with 60–75 mg/kg ONC213 by p.o. or vehicle control (3% 200-proof ethanol, 1% polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monooleate, and USP water). The mice were treated with 10 doses of ONC213. Peripheral blood was collected on day 36 and the percentage of bulk AML cells (hCD45+) and LSCs (hCD45+/hCD34+/hCD38-/hCD123+) were assessed by flow cytometry analyses (panel g).

We hypothesized that ONC213’s effect on colony formation was related to its effect on ONC213 on leukemic stem cells. To interrogate this, primary AML patient cells were treated with 500 nM ONC213 and then injected into the tail vein of B-NDG mice. After 12 weeks, the proportion of human CD45+ (hCD45+) cells in the mouse BM was assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2c). ONC213 treatment reduced engraftment to the baseline levels observed in non-tumor-bearing (NTB) mice (Fig. 2d). Similarly, serial re-plating (a measure of leukemia stem cell self-renewal) of Mycn overexpressing mouse hematopoietic progenitor cells revealed strongly reduced colony formation in these mouse AML LSCs (Fig. 2e). These results demonstrate that ONC213 targets AML LSCs ex vivo.

Likely due to surviving leukemic stem cells, relapsed AML represents a therapeutic challenge. We next tested the in vivo efficacy of ONC213 against LSCs derived from a relapsed AML patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, J000106565. These cells were poorly responsive to ONC213 ex vivo (Supplemental Fig. S1d). J000106565 cells were injected into the tail vein of NSGS mice (day 0) followed by treatment with ONC213 (60–75 mg/kg, p.o., daily), which began when the mouse peripheral blood contained 20% human AML cells. On day 36, the percentage of bulk AML cells (hCD45+) and LSCs (hCD45+/hCD34+/hCD38-/hCD123+) were assessed in the peripheral blood (Fig. 2f). While ONC213 modestly suppressed bulk AML cells, it potently decreased LSCs (Fig. 2g), demonstrating that ONC213 can target relapsed AML LSCs in vivo.

Cumulatively, these results show that ONC213 has activity against bulk AML and stem cells both in vitro and in vivo.

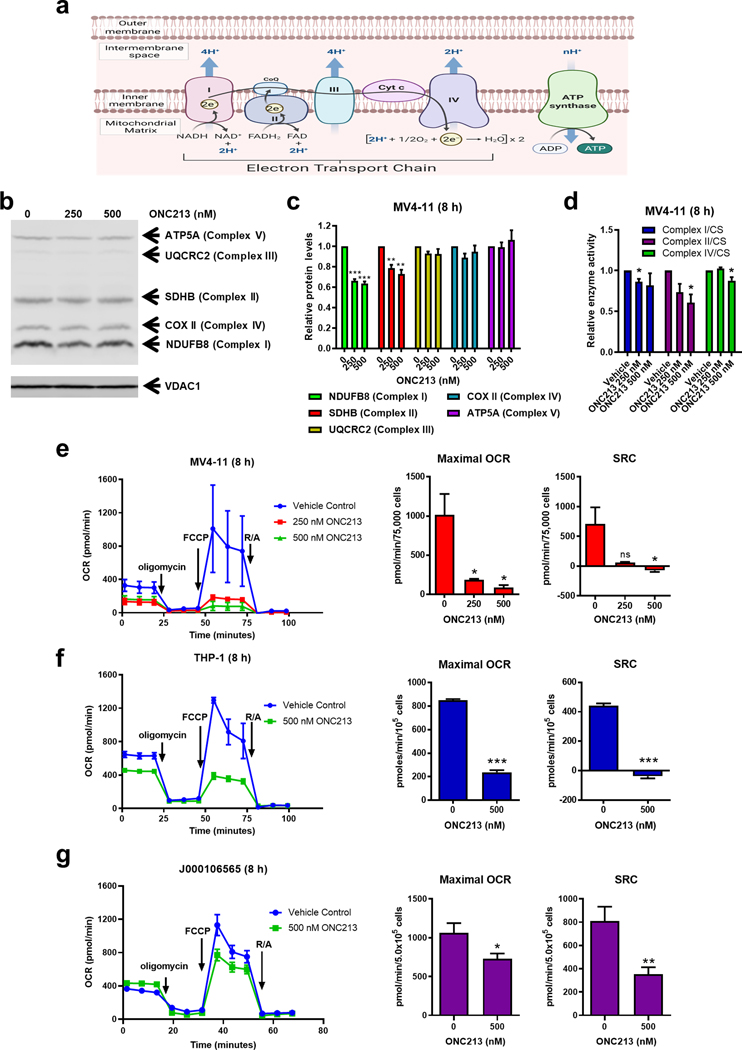

ONC213 Suppresses Mitochondrial Respiration

ONC201 and ONC212 treatment in AML has been reported to reduce electron transport chain (ETC; Fig. 3a) proteins through ClpP activation (6). ONC213 also activated ClpP in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S2a–d), but in cellulo it only modestly reduces some ETC proteins in AML cells (Fig. 3b–c; Supplemental Fig. S3a–b). This is consistent with the modest effect on the activities of Complexes I and II and negligible effect on Complex IV activity (Fig. 3d). This indicates that ClpP activation by ONC213 in cellulo is trivial compared to ONC201 (6).

Fig. 3. ONC213 suppresses mitochondrial respiration.

a. Diagram of OXPHOS (created with BioRender.com). b&c. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h. Protein lysates from mitochondrial extracts were analyzed by western blot and probed with a human OXPHOS antibody cocktail [complex I, NDUFB8; complex II, SDHB; complex III, UQCRC2; complex IV, cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COX II); and complex V, ATP synthase subunit alpha (ATP5A); panel b]. VDAC1 was used as a loading control. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to VDAC1 and then compared to vehicle control, are graphed as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (panel c). ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to control. d. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h. Cells were then lysed and assayed for complex I, II, IV, or citrate synthase (CS) activity. Activity was normalized by the total cell number. The ratio of complex I, II, or IV activity to CS activity was determined and normalized to the vehicle control. * P<0.05 compared to vehicle control. e-g. MV4–11, THP-1, and J000106565 cells were treated for 8 h with ONC213. Basal OCR was assessed, and then oligomycin (final concentration, 1 μM), FCCP (0.5 or 1 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM each) were added at the indicated times. OCR was measured using a Seahorse flux analyzer. Results of maximal OCR and SRC from 2–4 independent experiments are summarized. ns, not significant; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control.

Surprisingly, treatment of MV4–11 and THP-1 cells with ONC213 for 8 h (a duration which does not detectably affect their viability) strongly suppressed maximal OCR and spare respiratory capacity (SRC), with a minimal effect on basal respiration (Fig. 3e–f). ONC213 treatment of the PDX cells (isolated from mice inoculated with passaged primary AML patient cells (J000106565)) also significantly reduced maximal OCR and SRC (Fig. 3g). Here we demonstrate that ONC213 treatment reduces mitochondrial respiration with minimal effect on ETC complex levels and activities. Interestingly, ONC213-treated MV4–11 and THP-1 cells had a compensatory increase in glycolysis (ECAR; Supplemental Fig. S3c).

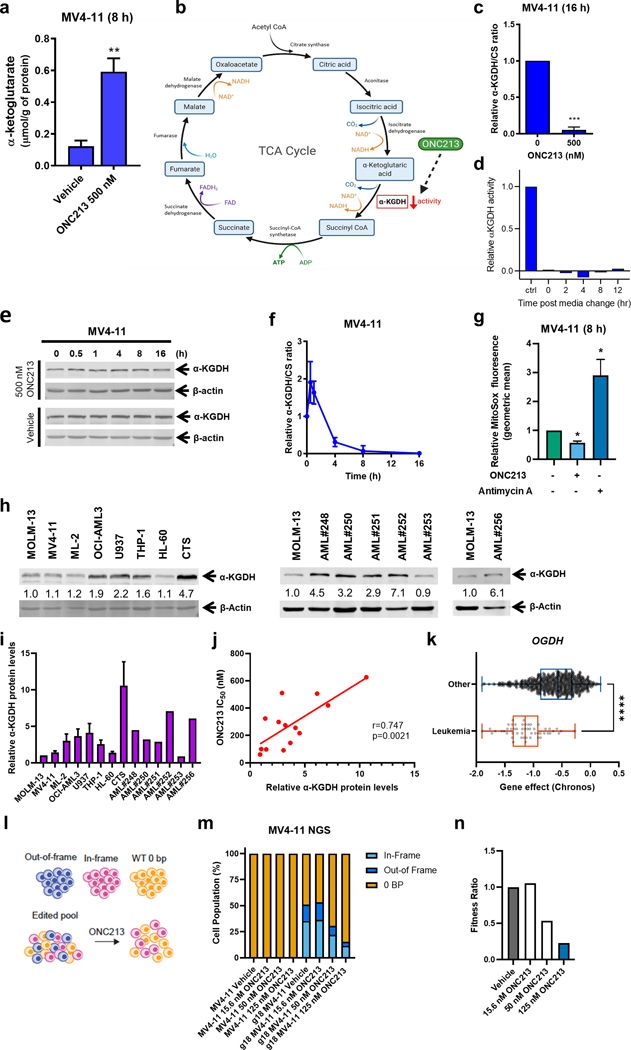

ONC213 Inhibits the Activity of α-KGDH

The citric acid (TCA) cycle intimately connects to the ETC. Thus, we measured TCA cycle intracellular metabolites (α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), succinyl-CoA, succinate, fumarate, malate, and oxaloacetate) in vehicle- and ONC213-treated MV4–11 and THP-1 cells for 8 h. The only TCA cycle metabolite with a significant change was a 2-to-~5-fold increase in α-KG (Fig. 4a; Supplemental Fig. S4a), which is formed downstream of isocitrate dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the TCA cycle (Fig. 4b). In MV4–11 cells, ONC213 treatment completely suppressed α-KGDH activity (Fig. 4c), which was maintained even after resuspension in drug-free medium (Fig. 4d). In contrast, ONC201 had no effect on α-KGDH activity in the same cell line (Supplemental Fig. S4b). ONC213 treatment did not affect the amount of α-KGDH protein for intervals up to 16 h (Fig. 4e). MV4–11 cells co-treated with ONC213, and the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK showed identical suppression of α-KGDH activity, thus ruling out loss of viability as an explanation for reduced activity (Supplemental Fig. S4c). ONC213 treatment of MV4–11 cells strongly suppressed α-KGDH activity by 93% within 4 h and completely suppressed α-KGDH activity by 8 h (Fig. 4f). ONC213 exposure suppressed mitochondrial superoxide (Fig. 4g), a finding consistent with the suppression of TCA activity by α-KGDH inhibition. No change in mitochondrial membrane potential or total cellular ROS occurred in MV4–11 cells, thus indicating a specific effect on mitochondrial TCA activity (Supplemental Fig. S4d–f). The strong positive and significant correlation (r=0.747, p=0.0021) between ONC213 IC50 and α-KGDH protein level (Fig. 4h–j) and the α-ketoglutarate elevation suggested that α-KGDH was the ONC213 target. To genetically assess the contribution of α-KGDH (OGDH encodes α-KGDH), we assessed OGDH dependency data from 27 cancer lineages (depmap.org/portal). Chronos scores below −1 imply cell line dependence on OGDH for survival. The mean Chronos score for leukemia cells was below −1 which indicates more OGDH dependence for survival than that of the other cancer cell lines (Fig. 4k). To genetically determine if ONC213 targets α-KGDH, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to delete OGDH from a population of MV4–11 cells. The resulting cell population had a range of OGDH gene status from those with either no deletion, an out-of-frame OGDH or an in-frame OGDH deletion. This genetically heterogeneous population of OGDH gene-edited cells were exposed to various ONC213 concentrations (Fig. 4l). Subsequently among surviving cells, next generation sequencing (ngs) was conducted. Analysis of the ngs sequencing revealed that ONC213 treatment strongly and concentration-dependently depleted cells in which OGDH had been edited (Fig. 4m). This result was affirmed by calculating the “fitness ratio” (the proportion of OGDH gene indels in the original population compared to after ONC213 treatment; Fig. 4n). In total, these findings confirm that α-KGDH is required to optimally survive an ONC213 challenge. Isolated single cell clones from the OGDH edited pool confirmed that the CRISPR edited cells have reduced α-KGDH levels and exhibit impaired oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS; Supplemental Fig. S4g–i).

Fig. 4. ONC213 treatment suppresses α-KGDH activity.

a. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h. Cells were collected, washed with PBS, and cell pellets were stored at −80 °C. Metabolites were quantitatively profiled using LC-MS/MS-based targeted metabolomics platform at the Karmanos Cancer Institute Pharmacology Core. Data were analyzed using www.MetaboAnalyst.ca, version 4.0. α-ketoglutarate is graphed as mean ± SEM. ** P<0.01. b. TCA cycle diagram (created with BioRender.com). c. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 16 h. α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) activity was measured. The ratio of α-KGDH activity to CS activity was determined and normalized to the vehicle control. *** P<0.001 compared to control. d. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or 500 nM ONC213 for 16 h. The cells were resuspended in drug-free medium and α-KGDH activity was measured at 0–12 h post media change. e. Whole cell lysates from MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for up to 16 h were analyzed by western blot. Representative western blots are shown. f. α-KGDH activity to CS activity was determined in MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or 500 nM ONC213 for various intervals up to 16 h. g. MV4–11 cells were treated with either vehicle or 250 nM ONC213 for 8 h. MV4–11 cells were treated with the Complex III inhibitor antimycin A (50 uM, 15 minutes before MitoSox addition) as a positive control for mitochondrial ROS induction. Cells were stained with 5 uM MitoSox for 30 minutes. Samples were collected, washed with PBS, and flow cytometry was used to measure MitoSox fluorescence. Geometric mean was calculated using FlowJo version 10.8.1. Relative MitoSox fluorescence was determined with respect to the vehicle treated group. ONC213 decreased superoxide production. * P<0.05 h-j. Whole cell lysates from AML cell lines and primary patient samples were analyzed by western blot. Representative western blots are shown. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to MOLM-13, are indicated. Normalized densitometry measurements are shown in panel i (cell line data was generated from three independent experiments, while primary patient samples were from one experiment due to limited sample). Relative α-KGDH protein levels were graphed against ONC213 IC50s in panel j. The relationship between protein levels and IC50s was determined by nonparametric Spearman rank correlation coefficient. k. Chronos scores from the OGDH dependency data derived from the Public 22Q4 dataset were plotted for leukemia and other cancer cell lines. l-n. MV4–11 cells were transfected with gRNA specific to OGDH and the gene editing was confirmed by next generation sequencing. The cells were then treated with the indicated concentration of ONC213 for 72 h and harvested. Genomic DNA was harvested and sequenced to determine the extent of gene editing in the cells that survived. In the pooled cells, there are three groups of cells: out-of-frame deletion resulting in a loss of functional gene, in-frame-deletion that may not result in a loss of function, and a 0-bp deletion representing WT cells. There was a specific fitness defect after ONC213 treatment for MV4–11 cells with out-of-frame deletion in OGDH gene. A fitness ratio was calculated by dividing the percentage of out-of-frame indels in ONC213 treated groups by the percentage of out-of-frame indels in the vehicle treated sample. The dose-dependent decrease in fitness ratio further indicates a fitness defect in MV4–11 cells lacking functional OGDH.

ONC213 Sensitivity is Determined by Reliance on OXPHOS

Because of OGDH being an ONC213 target and OXPHOS reliance as a determinant of ONC213 sensitivity, we assessed if switching the carbon sugar source in cell culture medium from glucose to galactose, which forces cells to rely on OXPHOS rather than glycolysis affected ONC213 sensitivity (37). Sensitivities of MV4–11 and MOLM-13 to ONC213 were virtually unchanged in glucose versus galactose, indicating that these AML cells more generally use OXPHOS than glycolysis for generating ATP (Supplemental Fig. S5a). In contrast, THP-1 and U937 cells were strongly sensitized to ONC213 only during culture in galactose-containing media (Supplemental Fig. S5b). This disparate “sugar-dependent” ONC213 cytotoxicity was also observed in primary AML cells from patients #231, #235, and #237 (Supplemental Fig. S5c) indicating this is not an AML cell line phenomenon. Together with Supplemental Fig. S3c, these findings indicate that AML cells with preference for OXPHOS are more sensitive to ONC213.

Inherent Differences in OXPHOS Gene Expression in AML

We hypothesized that AML cells sensitive to ONC213-induced cell death might exhibit higher expression levels for genes encoding critical proteins in the OXPHOS pathway. We queried the CCLE database (www.broadinstitute.org/ccle) for gene expression datasets for MOLM-13, MV4–11, THP-1, HL-60, and U937 cell lines. These datasets were normalized, permitting interrogation of glycolytic and OXPHOS pathways. The PCA plot revealed that MOLM-13 and MV4–11 are most similar in their first and second principal components versus other cell lines (Supplemental Fig. S6a). Importantly, when OXPHOS was assessed as a gene set versus the AML FAB subtype, no significant differences were revealed (Supplemental Fig. S6b). An unsupervised analysis of the top 50 most variable genes revealed independent clustering of MOLM-13 and MV4–11 (Supplemental Fig. S6c) and that these two cell lines were most similar in their OXPHOS pathway genes (Supplemental Fig. S6d). Glycolytic genes did not distinguish the cell lines (Supplemental Fig. S6e).

ONC213 Induces a Mitochondrial Stress Gene Expression Signature Related to Suppressed de novo Protein Synthesis

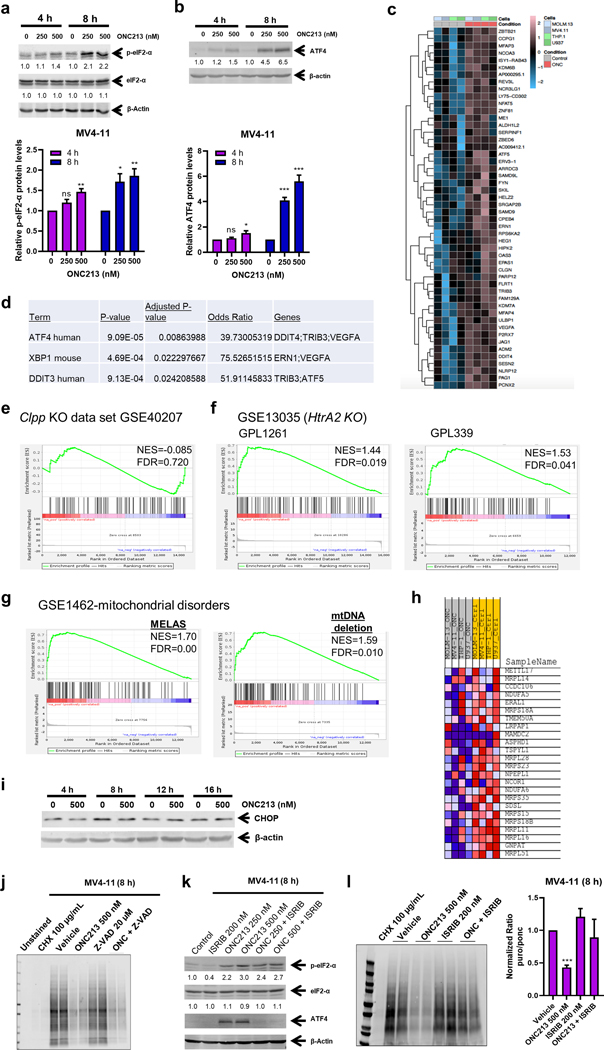

We next hypothesized that reduced mitochondrial respiration might induce mitochondrial stress. eIF2-α phosphorylation is frequently associated with mitochondrial stress (38, 39). Treatment of MV4–11 cells with ONC213 resulted in concentration- and time-dependent increase in eIF2-α phosphorylation (Fig. 5a). Increased eIF2-α phosphorylation is sometimes accompanied by enhanced expression of the transcription factor ATF4 (40–42) due to the switch in ORF use. Western blotting revealed strong induction of ATF4 after exposure to ONC213 (Fig. 5b and Supplemental Fig. S7a–b). To obtain a “fingerprint” of the mitochondrial stress (43–46), RNA-seq analysis of MV4–11, MOLM-13, U937, and THP-1 cells was performed. This analysis revealed that 100 genes were upregulated in common and these genes readily distinguished ONC213-treated from untreated cells, with the heat map depicting the top 50 of these genes (Fig. 5c). Interactive pathway analysis of these genes using Enrichr (47–49) showed that ATF4 was the most significantly increased (Fig. 5d). The integrated stress response (ISR) is often associated with eIF2-α phosphorylation which can affect mTORC kinases. Importantly, ONC201 has been found to suppress phosphorylation of p70S6K, an mTOR substrate (7). However, GSEA of the PI3K/mTOR pathway genes using the databases from HALLMARK, KEGG, and BIOCARTA revealed no significant enrichment of the P13K/mTOR or pathway genes among those increased by ONC213. This finding further differentiates ONC213 from ONC201 (Supplemental Fig. S7c).

Fig. 5. ONC213 induces a mitochondrial stress gene expression signature and suppresses protein synthesis.

a&b. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 4 or 8 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with the indicated antibodies. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are indicated below the corresponding blots (upper panels). Densitometry results from 3 independent experiments are graphed and shown in the lower panels. ns, not significant; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control. c-g. MV4–11, MOLM-13, U937 and THP-1 cells were treated with vehicle or 500 nM ONC213 for 48 h and then RNAseq gene expression profiling was performed. The top 50 differentially expressed upregulated genes are shown in panel c as a heat map. Activated transcription factors were determined by unbiased interrogation by the interactive pathway analysis tool, Enrichr, using the 100 upregulated differentially expressed genes (panel d). GSEA of the 100 upregulated genes by ONC213 compared to genes associated with Clpp knockout is shown in panel e. GSEA of ONC213 upregulated genes overlapping with HtrA2 knockout is shown in panel f. GSEA of ONC213 upregulated genes overlapping with mitochondrial disorders is shown in panel g. Enrichr analysis of the ONC213 signature genes affecting translation is shown in panel h. i. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for up to 16 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot. j. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, cycloheximide (CHX; as a positive control for inhibition of protein synthesis), ONC213, ZVAD-FMK, or ONC213 + ZVAD-FMK for 8 h and then 1 μM puromycin was added for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with anti-puromycin antibody. k. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, ISRIB, ONC213, or in combination for 8 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with the indicated antibodies. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are indicated below the corresponding blots. l. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, cycloheximide, ONC213, ISRIB, or ONC213 combined with ISRIB for 8 h and then 1 μM puromycin was added for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with anti-puromycin antibody. One representative blot is shown (left panel). Densitometry measurements (normalized to vehicle control) are graphed and shown (right panel). *** P<0.001.

Next, we hypothesized that these genes upregulated by ONC213 treatment might have a mitochondrial stress gene signature unique to ONC213. We next determined if ONC213-induced genes were similar to those that occur secondary to CLPP deficiency (CLPP knockout). The GSEA plot of this gene set showed that ONC213-activated genes were not among those significantly enriched (NES=−0.085) in the CLPP dataset (Fig. 5e). This analysis was extended to genes activated in response to loss of the inner mitochondrial membrane serine protease HTRA2 (45). Intriguingly, ONC213-upregulated genes were significantly enriched among the HTRA2 gene set (enrichment scores of 1.44 and 1.53) (Fig. 5f). Importantly, ONC213-upregulated genes were also significantly enriched among gene sets typifying additional mitochondrial pathologies such as encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and MELAS, especially those with mitochondrial deletions (Fig. 5g). Collectively, these data indicate that ONC213 activates genes that resemble diseases with defects of mitochondrial origin but remain distinct from CLPP. Further, Enrichr analysis of ONC213 induced genes revealed a significant enrichment of genes related to mitochondrial translation initiation, elongation, and termination (Fig. 5h; Supplemental Fig. S7d). The CHOP transcription factor can be induced as part of the ISR (50); however, unlike ONC201 which increases CHOP, CHOP was not induced by ONC213 (Fig. 5i; Supplemental Fig. S7e).

Based on the latter and an understanding that activation of the stress response can alter protein translation, we used puromycin-pulse labeling (51) to assess if de novo protein synthesis was altered in MV4–11 cells treated with either of the following: vehicle, cycloheximide (protein synthesis inhibitor), ONC213, Z-VAD-FMK, or ONC213 + Z-VAD-FMK (to eliminate potential effects of ONC213-induced cell death on protein synthesis). As expected, cycloheximide treatment abrogated de novo protein synthesis. ONC213 also strongly suppressed new protein synthesis (Fig. 5j). In contrast, new protein synthesis in THP-1 cells was unaffected by ONC213 (Supplemental Fig. S7f). However, THP-1 cells cultured in OXPHOS promoting media (galactose) showed strong reduction in new protein synthesis (Supplemental Fig. S7g). Importantly, MV4–11 cells treated with ONC201 showed no reduction in new protein synthesis (Supplemental Fig. S7h). Next, we determined if protein synthesis inhibition induced by ONC213 is overcome by the ISR inhibitor, ISRIB (52). ISRIB is a molecular staple, pinning together octameric subcomplexes of eIF2B, the translation initiation factor, to form an active complex that can restore protein synthesis despite eIF2-α phosphorylation (52). As expected, ISRIB addition did not affect the extent of eIF2-α phosphorylation but did relieve stress induction of ATF4 (Fig. 5k) and restored protein synthesis in ONC213-treated MV4–11 cells (Fig. 5l).

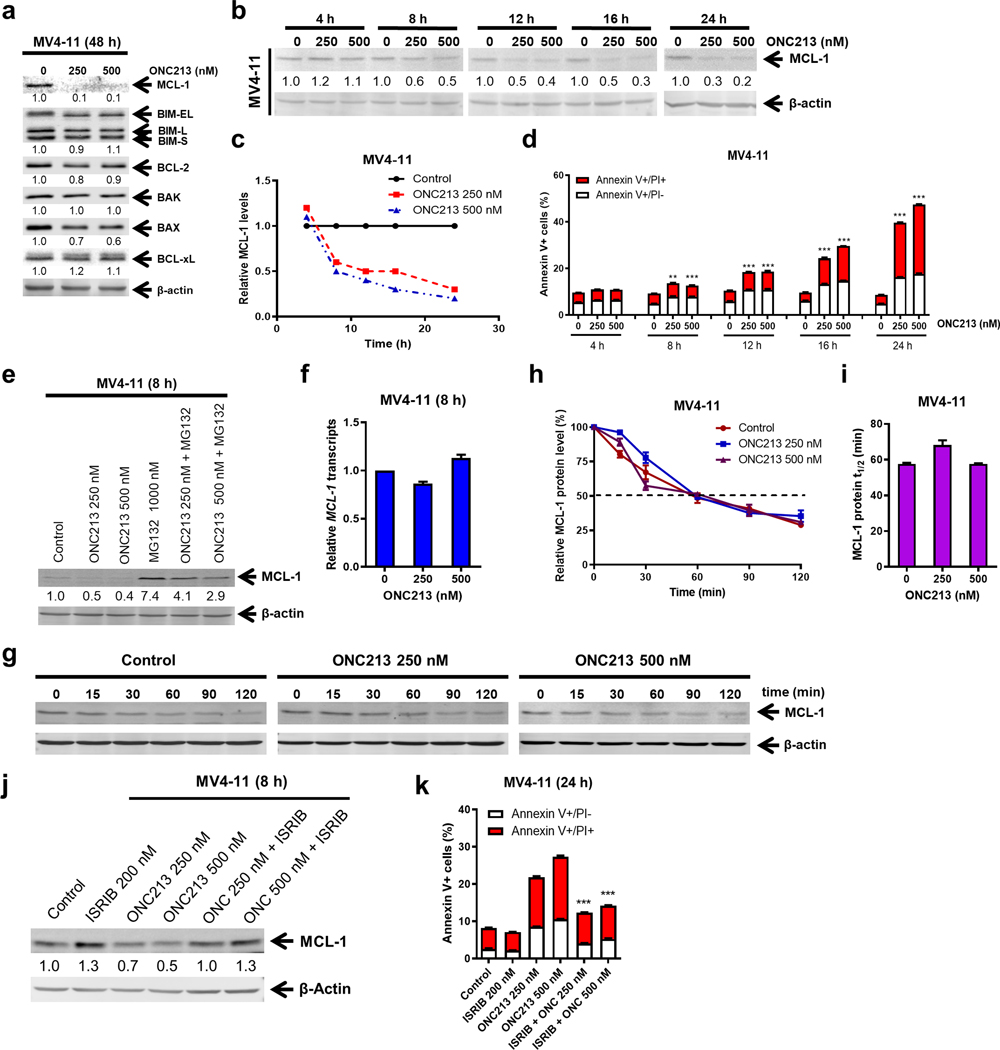

MCL-1 Plays an Important Role in ONC213-Induced Cell Death

Protein synthesis inhibition can reduce the level of proteins with short half-lives, such as MCL-1, which regulates mitochondrial function (53, 54) and cell death (55). Because reduction in MCL-1 translation might instigate ISR, we determined MCL-1 levels. Western blot analysis showed that ONC213 treatment strongly reduced MCL-l levels. Noteworthy other BCL-2 family members such as BIM, BCL-2, BAK, BAX, and BCL-xL were unaffected (Fig. 6a). ONC213 treatment reduced MCL-1 protein by up to 50% within 8 h (Fig. 6b–c) which correlated with the initiation of apoptosis suggesting a survival threshold was crossed when combined with suppression of respiration (Fig. 6d). Downregulation of MCL-1 protein by ONC213 was also detected in THP-1 cells (Supplemental Fig. S8a–c). Despite blockade of the proteasomal degradation of MCL-1 with MG132, ONC213 treatment reduced MCL-1 protein (Fig. 6e; Supplemental Fig. S8d) but not MCL-1 transcripts (Fig. 6f; Supplemental Fig. S8e). MCL-1 degradation appears unaffected by ONC213 as its half-life was virtually identical between vehicle- and ONC213-treated cells (Fig. 6g–i; Supplemental Fig. S8f–h). These results suggest that translation inhibition by ONC213 impacts MCL-1. Overriding translation inhibition with ISRIB restored MCL-1 protein levels in ONC213-treated cells (Fig. 6j; Supplemental Fig. S8i) and ISRIB treatment mostly rescued MV4–11 cells from ONC213-induced cell death (Fig. 6k).

Fig. 6. MCL-1 plays an important role in ONC213-induced cell death.

a-c. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 48 h (panel a) or up to 24 h (panels b&c). Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with the indicated antibodies. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are shown below the corresponding blots. Relative MCL-1 protein levels are graphed in panel c. d. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for up to 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control at the same timepoint. e. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, ONC213, MG132, or ONC213 + MG132 for 8 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are indicated. f. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h. Total RNA was extracted, and real-time RT-PCR was performed. The relative changes in MCL-1 transcripts, normalized to GAPDH, in comparison to control samples were quantified. The displayed results represent the mean of three independent experiments, with fold changes calculated via the comparative Ct method. g-i. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h, washed and then treated with 10 μg/mL cycloheximide for up to 2 h. Western blots were generated utilizing whole cell lysates and representative blots are shown in panel g. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to 0 min, are graphed in panel h. MCL-1 protein half-life was calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.0 and graphed in panel i. j. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, ISRIB, ONC213, or ISRIB combined with ONC213 for 8 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blot. The fold changes for the densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are indicated. k. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle, ONC213, ISRIB, or ONC213 combined with ISRIB for 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. *** P<0.001 compared to ONC213 treatment alone.

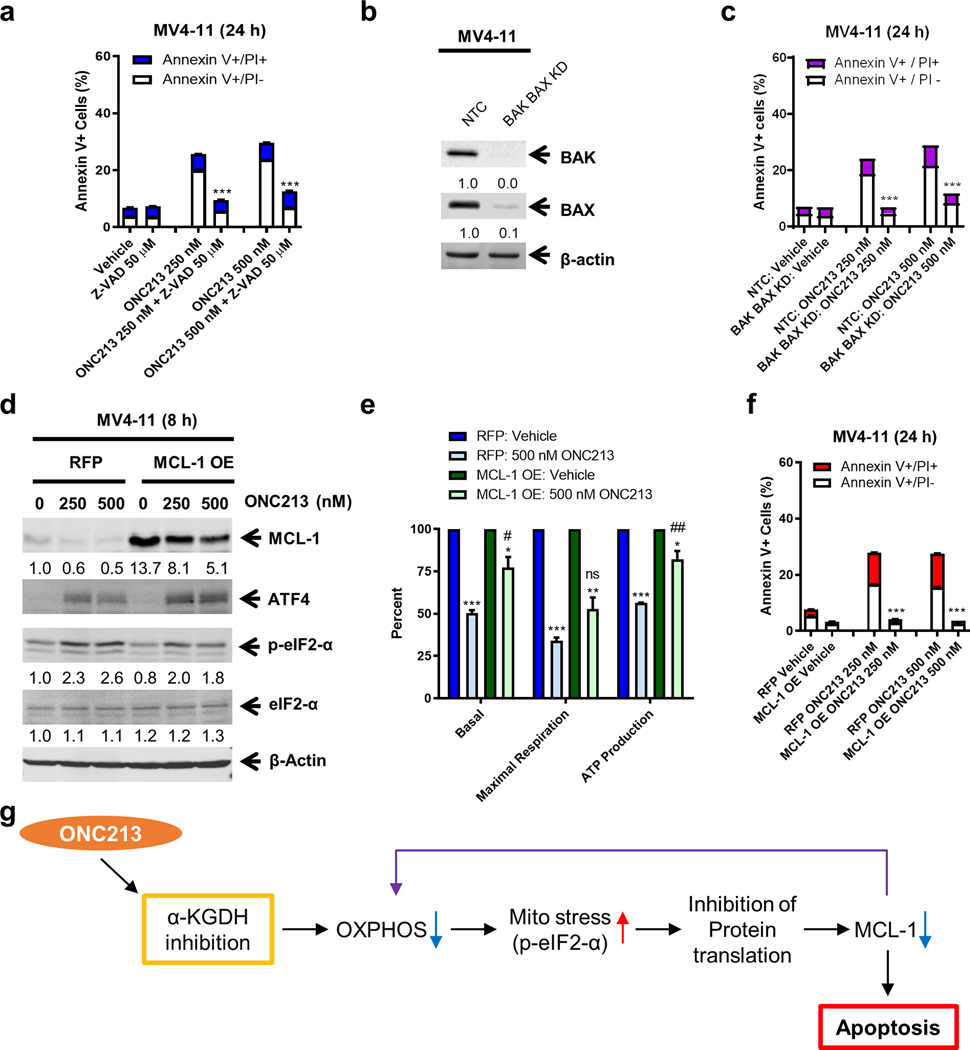

MCL-1 has a valuable role in mitochondrial respiration (54). This coupled with ONC213’s suppression of both mitochondrial respiration and MCL-1 led to the hypothesis that there was a relationship between MCL-1 amount and ONC213 sensitivity. Among eight different AML cell lines, we determined the relationship between ONC213 IC50 and MCL-1 levels (Supplemental Fig. S8j–l). The negative correlation between the ONC213 IC50 and MCL-1 level (r=−0.762, p=0.0388) suggests that the level of MCL-1 in AML is a factor in ONC213 sensitivity. Given the important role MCL-1 plays in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, we tested whether this pathway impacts ONC213 cytotoxicity. The pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and double knockdown of BAK and BAX significantly rescued MV4–11 cells from ONC213 treatment (Fig. 7a–c), confirming that ONC213 induced death relies on the intrinsic pathway to induce apoptosis. Overexpression of MCL-1 did not prevent ONC213-induced mitochondrial stress, as ATF4 was still induced (Fig. 7d). Consistent with its reported role in mitochondrial respiration (54), overexpression of MCL-1 resulted in recovery of basal OCR and OCR related to ATP production (Fig. 7e) and abolished ONC213-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7f), suggesting that MCL-1 contributes to ONC213 sensitivity in AML cells.

Fig. 7. Relationship between MCL-1 and ONC213 sensitivity.

a. MV4–11 cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 in the presence or absence of Z-VAD-FMK for 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. *** P<0.001 compared to ONC213 treatment. b. Lentiviral shRNA double-knockdown of BAK and BAX was performed in MV4–11 cells (designated as BAK/BAX KD cells). Non-template negative-control shRNA was used as the control (designated as NTC cells). BAK and BAX double knockdown was confirmed by western blot. c. BAK/BAX KD and NTC cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. *** P<0.001. d. Lentiviral overexpression of RFP (red fluorescent protein) and MCL-1 (designated MCL-1 OE) was performed in MV4–11 cells. RFP control and MCL-1 OE cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h and then whole-cell lysates were analyzed by western blot and probed with the indicated antibodies. The fold changes for the MCL-1 densitometry measurements, normalized to β-actin and then compared to vehicle control, are indicated. e. The RFP control and MCL-1 OE cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 8 h. Basal OCR, maximal respiration, and ATP production were measured using a Seahorse flux analyzer. * P<0.05; ** P <0.01; *** P<0.001 compared to vehicle control. ns, not significant; # P<0.05; ## P <0.01 compared to RFP treated with 500 nM ONC213. f. The RFP control and MCL-1 OE cells were treated with vehicle or ONC213 for 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. Results are shown as mean Annexin V+ cells ± SEM. *** P<0.001 compared to RFP under the same treatment conditions. g. Proposed mechanism of action of ONC213. ONC213 inhibits α-KGDH, leading to reduced OXPHOS and mitochondrial stress (increase of eIF2α phosphorylation) in AML cells. This stress response leads to inhibition of protein translation, resulting in decrease of a key antiapoptotic protein, MCL-1. Decrease of MCL-1 results in further decrease of OXPHOS, leading to death of AML cells that are reliant on OXPHOS.

Discussion

Here we show that ONC213 uniformly reduces AML cell viability related to suppression of α-KGDH. Importantly, ONC213 is broadly lethal to AML progenitors and LSCs and displays favorable pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and efficacy against AML cells in vivo. There is little similarity between cellular response to ONC213 and its predecessor, ONC201, with the salient feature being ONC213 has a novel stress response profile and genetic and biochemistry studies indicate that the target is the TCA cycle enzyme, α-KGDH. Our studies show that dependencies upon α-KGDH render leukemias marked sensitive to its inhibition.

ONC213-induced cell death seems to be elicited by an early suppression of α-KGDH activity and mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 4a; Supplemental Fig. S4a). Besides ONC213 producing strong sustained α-KGDH inhibition, genetic studies show that AML cells lacking or with OGDH insufficiency were highly sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of ONC213 (Fig. 4l–n). These results highlight the importance of α-KGDH to ONC213’s mechanism of action. ONC213 induction of mitochondrial stress occurs in multiple AMLs and is characterized by suppression of de novo protein synthesis which appears after suppression of α-KGDH activity. We noted that AML cells that are more reliant on OXPHOS for energy generation were much more sensitive to ONC213.

CLPP is responsible for maintenance of protein quality control by degrading misfolded or denatured mitochondrial proteins (56–59). Both activation and inhibition of CLPP in AML cells lead to drastic cellular changes including decreases in OXPHOS, activation of ISR, inhibition of protein translation and changes in metabolism that promote cell death (6, 60). ONC201 and ONC212 are potent CLPP activators (6) with potent effects on the ETC enzymes. We demonstrate that although ONC213 activates CLPP in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S2), ONC213 treated cells have minimal reductions in ETC proteins and activities which is unlike the ETC effects on AML cells treated with ONC201. ONC213 treatment produces both eIF2-α phosphorylation and ATF4 induction, which is coupled to a massive reduction in de novo translation of cellular proteins and increased AML cell death (Fig. 5). When cells were co-treated with ISRIB, an agent that reverses the protein synthesis inhibiting effects of eIF2-α phosphorylation (52), protein synthesis was restored, and cells were rescued from death. Induction of ATF4 via ONC201 is reportedly independent of eIF2-α phosphorylation (7) and here we demonstrate that ATF4 induction via ONC213 is reliant on eIF2-α phosphorylation. Notably, ONC201 inhibits mTOR activation and activates CHOP (Fig. 5i; Supplemental Fig. S7c, e). CHOP is not induced by ONC213 which further distinguishes it from ONC201.

MCL-1 is an important protein in promoting AML cell survival and regulating mitochondrial function (54, 55, 61, 62). MCL-1 was strongly reduced by ONC213, which coincided with the onset of apoptosis in AML cells (Fig. 6b–d). Further, suppression of mitochondrial respiration by ONC213 was temporally coupled with a profound alteration in the morphology of mitochondria (Supplemental Fig. S9a–b), which strongly resembles the aberrant mitochondrial morphology produced by absence of MCL-1 (54). In addition, activation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway contributes to ONC213-induced cell death because BAK and BAX knockdown significantly reduced apoptosis induction in ONC213-sensitive AML cells (Fig. 7b–c). Moreover, MCL-1 overexpression rescued cells from ONC213 induced cell death and attenuated the suppression of OXPHOS in response to ONC213. The retention of a mitochondrial stress response despite MCL-1 overexpression (Fig. 7d), highlights a key feature of ONC213-induced cell death.

In summary, ONC213 induces a unique mitochondrial stress response in AML cells that likely initiates after suppression of α-KGDH activity and mitochondrial respiration, as depicted (Fig 7g). We propose that the mitochondrial stress response promotes phosphorylation of eIF2α and inhibition of protein translation, which affects the amount of the antiapoptotic protein MCL-1. Thus, suppression of α-KGDH, combined with reduction in MCL-1 strongly associates with decreased OXPHOS, resulting in death of OXPHOS-reliant cells (Fig. 7g). It is unlikely that the lack of toxicity of ONC213 to normal hematopoietic progenitors is due to α-KGDH expression as they express lower levels than AML. Moreover, previous studies have shown that normal hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells preferentially employ glycolysis for energy metabolism, contrary to LSCs which rely heavily on OXPHOS with little ability to utilize glycolysis (53, 63). These findings reveal the potential of ONC213 towards AML progenitors and LSCs. The reduction in leukemia progenitors and LSCs by ONC213 treatment is likely due to strong suppression of OXPHOS and this also accounts for the minimal toxicity of ONC213 toward normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. When combined with our in vivo studies in a murine xenograft and PDX model of AML, our findings suggest that ONC213 will likely be well tolerated with minimal myelotoxicity, a key advantage in future clinical development which might extend possible use in other cancers beside AML. Furthermore, because LSCs and progenitor cells can evade frontline therapy (64) and can drive relapse, ONC213 seems like a valuable potential addition to the frontline chemotherapy armamentaria.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

In AML cells, ONC213 suppresses α-KGDH, which induces a unique mitochondrial stress response, and reduces MCL-1 to decrease oxidative phosphorylation and elicit potent antileukemia activity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University School of Medicine, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Jilin University, Changchun, China, and by grants from Kids Without Cancer, Children’s Hospital of Michigan Foundation, LaFontaine Family/U Can-Cer Vive Foundation, Decerchio/Guisewite Family, Justin’s Gift, Elana Fund, Ginopolis/Karmanos Endowment and the Ring Screw Textron Endowed Chair for Pediatric Cancer Research. Aaron D. Schimmer holds the Ronald N. Buick Chair in Oncology Research. The Animal Model and Therapeutics Evaluation Core, Pharmacology Core, and Genomics Core are supported, in part, by NIH Center Grant P30 CA022453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University. The National Institutes of Health T32 grant (CA009531) to the Cancer Biology Graduate Program at Wayne State University School of Medicine. The Cell & Tissue Imaging Center is supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), NCI P30 CA021765 (SJCRH), and NIH grants R01 CA194057, CA21865, and CA96832 to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The other funders also had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

JEA and VVP are employees and stockholders of Chimerix, Inc. ADS has received honorariums or consulting fees from Novartis, Jazz, Otsuka, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals and research support from Medivir AB and Takeda. He owns stock in Abbvie Pharmaceuticals and is named on a patent application for the use of DNT cells for the treatment of leukemia. YG has received research support from MEI Pharma, Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

YS, JLC, XL, JL, YF, HE, JM, PS, LP, JK, SHD, SAB, AG, SMP-M, KH-H, CR, XQ, SL, SW, GW, JLi, DJ, SK-M, IDGW, RM, MBI, RA-A, JWT, HL, and JDS declare no competing or conflicting interests, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1684–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson PM, Scott J. Imipridone family on successful TRAIL. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:1487–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen JE, Krigsfeld G, Mayes PA, Patel L, Dicker DT, Patel AS, et al. Dual inactivation of Akt and ERK by TIC10 signals Foxo3a nuclear translocation, TRAIL gene induction, and potent antitumor effects. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:171ra17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhu VV, Morrow S, Rahman Kawakibi A, Zhou L, Ralff M, Ray J, et al. ONC201 and imipridones: Anti-cancer compounds with clinical efficacy. Neoplasia. 2020;22:725–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishizawa J, Zarabi SF, Davis RE, Halgas O, Nii T, Jitkova Y, et al. Mitochondrial ClpP-Mediated Proteolysis Induces Selective Cancer Cell Lethality. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:721–37 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishizawa J, Kojima K, Chachad D, Ruvolo P, Ruvolo V, Jacamo RO, et al. ATF4 induction through an atypical integrated stress response to ONC201 triggers p53-independent apoptosis in hematological malignancies. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner J, Kline CL, Ralff MD, Lev A, Lulla A, Zhou L, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the imipridone family, analogs of clinical stage anti-cancer small molecule ONC201, reveals potent anti-cancer effects of ONC212. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:1790–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu X, Wang G, Wang Y, Caldwell JT, Edwards H, Xie C, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia cells harboring MLL fusion genes or with the acute promyelocytic leukemia phenotype are sensitive to the Bcl-2-selective inhibitor ABT-199. Leukemia. 2014;28:1557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su Y, Li X, Ma J, Zhao J, Liu S, Wang G, et al. Targeting PI3K, mTOR, ERK, and Bcl-2 signaling network shows superior antileukemic activity against AML ex vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;148:13–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uphoff CC, Drexler HG. Detection of mycoplasma contaminations. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiao X, Ma J, Knight T, Su Y, Edwards H, Polin L, et al. The combination of CUDC-907 and gilteritinib shows promising in vitro and in vivo antileukemic activity against FLT3-ITD AML. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie C, Edwards H, Xu X, Zhou H, Buck SA, Stout ML, et al. Mechanisms of synergistic antileukemic interactions between valproic acid and cytarabine in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Niu X, Li X, Edwards H, Wang G, Wang Y, et al. Inhibition of CHK1 enhances cell death induced by the Bcl-2-selective inhibitor ABT-199 in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:34785–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards H, Xie C, LaFiura KM, Dombkowski AA, Buck SA, Boerner JL, et al. RUNX1 regulates phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway: role in chemotherapy sensitivity in acute megakaryocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2744–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Su Y, Hege K, Madlambayan G, Edwards H, Knight T, et al. The HDAC and PI3K dual inhibitor CUDC-907 synergistically enhances the antileukemic activity of venetoclax in preclinical models of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2021;106:1262–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hege Hurrish K, Qiao X, Li X, Su Y, Carter J, Ma J, et al. Co-targeting of HDAC, PI3K, and Bcl-2 results in metabolic and transcriptional reprogramming and decreased mitochondrial function in acute myeloid leukemia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;205:115283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Kalpage HA, Wang D, Edwards H, Huttemann M, Ma J, et al. Cotargeting of Mitochondrial Complex I and Bcl-2 Shows Antileukemic Activity against Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Reliant on Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao X, Wu J, Kim S, LoRusso P, Li J. Pharmacometabolomics Reveals Irinotecan Mechanism of Action in Cancer Patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59:20–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X, Xie C, Edwards H, Zhou H, Buck SA, Ge Y. Inhibition of histone deacetylases 1 and 6 enhances cytarabine-induced apoptosis in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal SK, Salem AH, Danilov AV, Hu B, Puvvada S, Gutierrez M, et al. Effect of ketoconazole, a strong CYP3A inhibitor, on the pharmacokinetics of venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Su Y, Madlambayan G, Edwards H, Polin L, Kushner J, et al. Antileukemic activity and mechanism of action of the novel PI3K and histone deacetylase dual inhibitor CUDC-907 in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:2225–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luedtke DA, Su Y, Liu S, Edwards H, Wang Y, Lin H, et al. Inhibition of XPO1 enhances cell death induced by ABT-199 in acute myeloid leukaemia via Mcl-1. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:6099–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuda Y, Wang Y, Lian S, Lynch J, Nagai S, Fanshawe B, et al. Upregulated heme biosynthesis, an exploitable vulnerability in MYCN-driven leukemogenesis. JCI Insight. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolde R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R Package. 2015:790. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li-Harms X, Milasta S, Lynch J, Wright C, Joshi A, Iyengar R, et al. Mito-protective autophagy is impaired in erythroid cells of aged mtDNA-mutator mice. Blood. 2015;125:162–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinazzi M, Casarin A, Pertegato V, Salviati L, Angelini C. Assessment of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymatic activities on tissues and cultured cells. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1235–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prabhu VV, Talekar MK, Lulla AR, Kline CLB, Zhou L, Hall J, et al. Single agent and synergistic combinatorial efficacy of first-in-class small molecule imipridone ONC201 in hematological malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:468–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutherland H, Blair A, Vercauteren S, Zapf R. Detection and clinical significance of human acute myeloid leukaemia progenitors capable of long-term proliferation in vitro. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aguer C, Gambarotta D, Mailloux RJ, Moffat C, Dent R, McPherson R, et al. Galactose enhances oxidative metabolism and reveals mitochondrial dysfunction in human primary muscle cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humeau J, Leduc M, Cerrato G, Loos F, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha (eIF2alpha) in autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khoutorsky A, Sorge RE, Prager-Khoutorsky M, Pawlowski SA, Longo G, Jafarnejad SM, et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation controls thermal nociception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:11949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crimi M, Bordoni A, Menozzi G, Riva L, Fortunato F, Galbiati S, et al. Skeletal muscle gene expression profiling in mitochondrial disorders. FASEB J. 2005;19:866–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhl I, Miranda M, Atanassov I, Kuznetsova I, Hinze Y, Mourier A, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic landscape of mitochondrial dysfunction reveals secondary coenzyme Q deficiency in mammals. Elife. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moisoi N, Klupsch K, Fedele V, East P, Sharma S, Renton A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction triggered by loss of HtrA2 results in the activation of a brain-specific transcriptional stress response. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:449–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quiros PM, Prado MA, Zamboni N, D’Amico D, Williams RW, Finley D, et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies ATF4 as a key regulator of the mitochondrial stress response in mammals. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:2027–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weger M, Alpern D, Cherix A, Ghosal S, Grosse J, Russeil J, et al. Mitochondrial gene signature in the prefrontal cortex for differential susceptibility to chronic stress. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xie Z, Bailey A, Kuleshov MV, Clarke DJB, Evangelista JE, Jenkins SL, et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr Protoc. 2021;1:e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishitoh H. CHOP is a multifunctional transcription factor in the ER stress response. J Biochem. 2012;151:217–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:275–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anand AA, Walter P. Structural insights into ISRIB, a memory-enhancing inhibitor of the integrated stress response. FEBS J. 2020;287:239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagadinou ED, Sach A, Callahan K, Rossi RM, Neering SJ, Minhajuddin M, et al. BCL-2 inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:329–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perciavalle RM, Stewart DP, Koss B, Lynch J, Milasta S, Bathina M, et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:575–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei AH, Roberts AW, Spencer A, Rosenberg AS, Siegel D, Walter RB, et al. Targeting MCL-1 in hematologic malignancies: Rationale and progress. Blood Rev. 2020;44:100672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nouri K, Feng Y, Schimmer AD. Mitochondrial ClpP serine protease-biological function and emerging target for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mirali S, Schimmer AD. The role of mitochondrial proteases in leukemic cells and leukemic stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9:1481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fischer F, Langer JD, Osiewacz HD. Identification of potential mitochondrial CLPXP protease interactors and substrates suggests its central role in energy metabolism. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deepa SS, Bhaskaran S, Ranjit R, Qaisar R, Nair BC, Liu Y, et al. Down-regulation of the mitochondrial matrix peptidase ClpP in muscle cells causes mitochondrial dysfunction and decreases cell proliferation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;91:281–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cole A, Wang Z, Coyaud E, Voisin V, Gronda M, Jitkova Y, et al. Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Protease ClpP as a Therapeutic Strategy for Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:864–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carter BZ, Mak PY, Tao W, Warmoes M, Lorenzi PL, Mak D, et al. Targeting MCL-1 dysregulates cell metabolism and leukemia-stroma interactions and resensitizes acute myeloid leukemia to BCL-2 inhibition. Haematologica. 2022;107:58–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glaser SP, Lee EF, Trounson E, Bouillet P, Wei A, Fairlie WD, et al. Anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 is essential for the development and sustained growth of acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Dev. 2012;26:120–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, Deberardinis RJ, Mahmoud AI, Olson EN, et al. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Craddock C, Quek L, Goardon N, Freeman S, Siddique S, Raghavan M, et al. Azacitidine fails to eradicate leukemic stem/progenitor cell populations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Leukemia. 2013;27:1028–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNAseq data has been deposited into GEO (accession #: GSE137249). The metabolomics data are available within the article and its supplementary data files. The data analyzed in this study were obtained from CCLE at www.broadinstitute.org/ccle (GSE36133) and depmap at https://depmap.org/portal/ (Public 22Q4 dataset). All other data reported in this paper are available within the article or will be provided upon request to either Yubin Ge (gey@karmanos.org) or John Schuetz (john.schuetz@stjude.org).