Abstract

Background

The literature on gun violence is broad and variable, describing multiple legislation types and outcomes in observational studies. Our objective was to document the extent and nature of evidence on the impact of firearm legislation on mortality from firearm violence.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted under PRISMA-ScR guidance. A comprehensive peer-reviewed search strategy was executed in several electronic databases from inception to March 2024. Grey literature was searched for unpublished sources. Data were extracted on study design, country, population, type of legislation, and overall study conclusions on legislation impact on mortality from suicide, homicide, femicide, and domestic violence. Critical appraisal for a sample of articles with the same study design (ecological studies) was conducted for quality assessment.

Findings

5057 titles and abstracts and 651 full-text articles were reviewed. Following full-text review and grey literature search, 202 articles satisfied our eligibility criteria. Federal legislation was identified from all included countries, while state-specific laws were only reported in studies from the U.S. Numerous legislative approaches were identified including preventative, prohibitive, and more tailored strategies focused on identifying high risk individuals. Law types had various effects on rates of firearm homicide, suicide, and femicide. Lack of robust design, uneven implementation, and poor evaluation of legislation may contribute to these differences.

Interpretation

We found that national, restrictive laws reduce population-level firearm mortality. These findings can inform policy makers, public health researchers, and governments when designing and implementing legislation to reduce injury and death from firearms.

Funding

Funding is provided by the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Evidence Alliance and in part by St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto.

Scoping review registration:

Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/sf38n.

Keywords: Firearms, Scoping review, Firearm mortality, Legislation

1. Introduction

Firearm violence is a growing public health concern. Mortality from firearms contributes more than 250,000 deaths each year worldwide [1]. The global burden of firearms receives less attention despite the concentration of gun violence in higher-income countries[1]. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention demonstrate that total gun deaths in the U.S. increased from 39,707 (2019) to 45,222 (2020), an increase per capita from 12.09/100,000 (2019) to 13.73/100,000 (2020). In 2021, total gun deaths increased further to 48,830, reflecting a crude rate of 14.6/100,000 and a 23 % increase since 2019 [2], [3]. Firearm mortality rates in Canada are increasing as well, with firearm-related violent crime now 25 % higher in 2021 compared to 2012 (27.4/100,000 versus 21.9/100,000). This is substantially higher than the annualized injury rate of 3.54/100,000 between 2002 and 2016[4].

Trends in firearm mortality are multifactorial, with firearm legislation being one potentially impactful, population-level etiology. There are multiple types of legislation with various outcomes evaluated by studies with differing methodologies[5]. Legislation at multiple levels of government often creates a series of laws in response, which can have significant implications individually and collectively. The variability behind gun legislation internationally demonstrates the importance of identifying policies and their impact on mortality. Furthermore, understanding how firearm legislation is designed and implemented can help elucidate why certain strategies might be more effective than others.

Previous reviews have been primarily U.S.-focused; therefore, we sought to review international studies. To our knowledge, only one review has included countries other than the US and its search ended in 2014[6]. Our review is intended to expand upon this body of knowledge by (1) including more recent, international studies; (2) reviewing relevant implications in a public health context; and (3) characterizing features of legislation that may show association with improved firearm mortality. Given the breadth of literature on firearm violence, a scoping review methodology was chosen because it provides a systematic overview of the evidence, enabling knowledge gaps to be identified and analyzed. A scoping review enables us to form an evidenced-based foundation of information that could be used to guide further, more targeted systematic reviews or prospective research on specific law types and their outcomes, which could be helpful for guiding policy makers with the design and implementation of effective legislation in the future. This scoping review aims to answer the following key questions (KQ):

-

a)

KQ1. What international firearm legislations have been evaluated for their impact on firearm-related suicide, femicide, homicide, and mass shooting rates in Canada and internationally?

-

b)

What has been the impact of Canadian and international firearms legislation on rates of death by firearm-related suicide, femicide, homicide, and mass shootings?

KQ2. What factors have improved or hindered the uptake of Canadian and international firearm legislation?

2. Methods

We report this scoping review in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Appendix 1) [7], [8]. We followed guidance from Levac and colleagues’ update of the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework and the Joanna Briggs Institute manual for scoping reviews [9], [10], [11]. The protocol and associated materials are registered on the Open Science Framework. Deviations from our protocol include using one reviewer to analyze and chart data, which was then verified by a second reviewer, and conducting a methodological appraisal on a of 20 % purposive random sample of studies of the most frequently used study design to gain initial insight on the quality of the evidence in firearm legislation.

2.1. Information sources and search strategy

An information specialist developed a detailed search strategy in consultation with the review team. The MEDLINE strategy was peer reviewed prior to execution using the PRESS Checklist [12]. Using the Ovid platform, we searched Ovid MEDLINE® ALL (n = 2725), Embase Classic + Embase (n = 784), and APA PsycINFO (n = 944). We also searched PAIS Index on Proquest (n = 604). The strategies used a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “Firearms”, “Homicide”, “Government Regulation”) and keywords (e.g., “gun”, “murder”, “laws”); vocabulary and syntax were adjusted across the databases. No language or date restrictions were applied but animal-only and conference papers were removed where possible. We conducted the databases searches on November 4, 2021 (Appendix 2) and updated these on March 19, 2024. Results were downloaded and deduplicated using EndNote version 9.3.3 (Clarivate Analytics) and uploaded to Covidence. A targeted search of the grey literature was subsequently performed to identify any relevant non-indexed and unpublished literature using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) Grey Matters checklist [13] as a guide and other relevant websites identified by the research team (Appendix 3).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined by the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework[11] (Table 1). Eligible studies for inclusion were any experimental studies, observational studies, systematic reviews or grey literature reports that evaluated the impact of firearm legislation on the rates of death by suicide, domestic violence, homicide, femicide, or mass shootings in any population. Studies that included policy initiatives led by industry, or any non-governmental organization were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion Criteria as defined by Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework[11].

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Any individual (all ages) or group that have been a victim of firearm violence. Some examples include gun owners, public, third parties such as gun businesses, and police. We will also include studies that evaluate specific populations (e.g., Indigenous populations, racial/ethnic minorities, individuals with disabilities). | N/A |

| Concept |

KQ1) The impact of firearm legislation on rates of suicide, domestic violence, homicide, and mass shootings in different populations, disease states, and/or environmental exposures. Firearm-related death by suicide, homicide, gun injuries associated with non-fatal suicide attempt, non-fatal homicide attempt will be included. KQ2) Any factors that have been evaluated for their impact on legislation uptake or implementation. We will define factors by any of the five domains outlined in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Some examples of factors may include, but are not limited to, cost, local firearm ideology, or law enforcement culture. Firearm legislation will be limited to local and federal laws, policies, and regulations for both KQs. |

Initiatives led by industry or any non-governmental organization (NGO). Any study evaluating accidental firearm injury. |

| Context (Setting) | Urban, rural, and remote settings internationally. | N/A |

| Study designs | Any experimental or observational study design (e.g., RCTs, quasi-randomized, controlled clinical trials, cohort studies, case-control, cross-sectional, time-series) and systematic reviews.Any relevant grey literature sources (e.g., government reports) and preprints. | Case reports, case series, narrative reviews, editorials, news articles, commentaries, letters, and conference proceedings. |

| Language | English | N/A |

| Dates of publication | No date limitations. | N/A |

2.3. Study selection

Search results were screened using Covidence[14]. To ensure inter-rater reliability between reviewers, we conducted pilot exercises on a random sample of 50 titles and abstracts and 25 full-text articles. Screening for title and abstracts and full-text studies was completed independently and in duplicate by reviewers using the study eligibility criteria listed in Table 1[14]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. All included articles were cross-checked against the Retraction Watch database and were removed if any articles were identified.

2.4. Data charting, extraction and synthesis

The charting process is an iterative process and consists of organizing and interpreting data by sifting, categorizing, and sorting material according to key issues and themes [10]. One independent reviewer charted included full-text studies using a pilot-tested standardized data abstraction form in Covidence., which was then verified by a second independent reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved with a third reviewer. Data extracted included study design, country, population, type of legislation, and overall study conclusions on legislation impact on outcome rates (e.g., suicide, homicide, femicide, and domestic violence). Results are presented as a narrative synthesis organized by country and grouped by law type for KQ1. For KQ2, we used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to organize implementation factors identified[15].

2.5. Critical appraisal

We critically assessed a purposive random sample of 20 % of included ecological studies to evaluate the quality of evidence (Appendix 4). We used and adapted the checklist proposed by Dufault et al. [16] previously used in two published systematic reviews [17], [18].

3. Role of funding source

Funding for this protocol and subsequent scoping review including study design and data extraction, collection and interpretation is provided by the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Evidence Alliance and in part by St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto.

4. Results

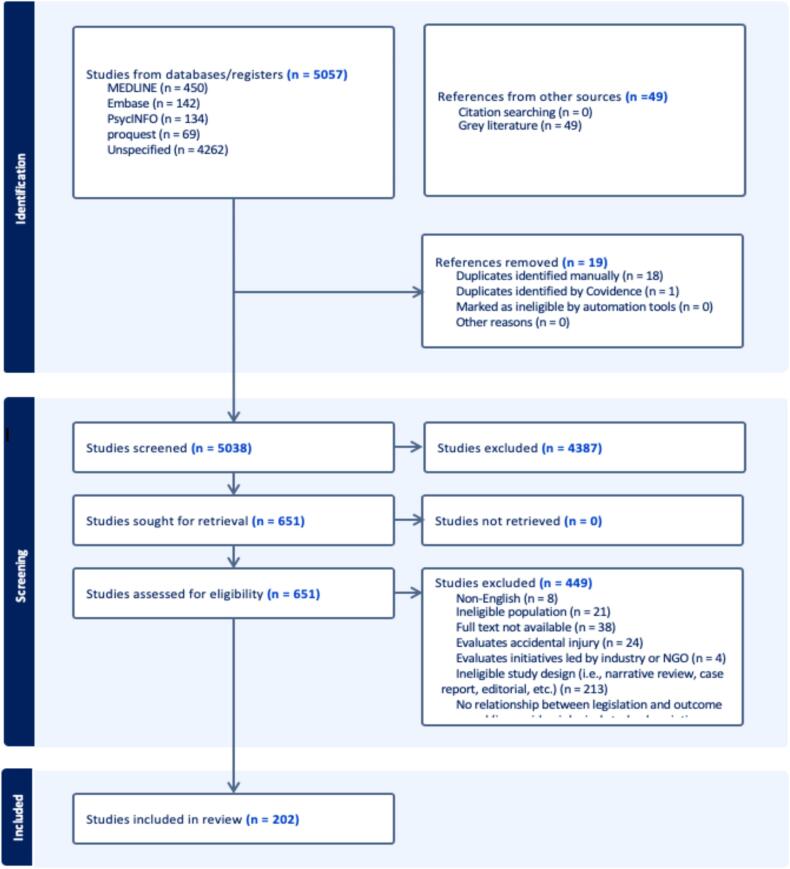

A total of 5057 titles and abstracts and 651 full-text articles was reviewed. Following full-text review, 202 articles were included, of which one was identified from our grey literature search [19] (Fig. 1)(Appendix 5). Sixty-seven percent of studies (n = 136) were published after 2015. Legislation was identified from 13 different countries including Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Israel, Montenegro, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Switzerland, and the U.S. Study designs included ecological studies (n = 93), time-trend analyses (n = 65), cross-sectional studies (n = 17), systematic reviews (n = 8), cohort studies (n = 6), qualitative studies (n = 7), non-randomized experimental studies (n = 4) and mixed methods studies (n = 1). No retracted articles were identified or removed following search of the Retraction Watch database.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). Full text studies (n = 202) and grey literature sources (n = 49) were analyzed separately.

We assessed the quality of 18 randomly selected ecological studies and found that the quality was generally acceptable (Appendix 4). Data in these 18 studies were usually aggregated at the national level. Some studies did not clearly indicate whether the ecological study was a longitudinal or cross-sectional design. Also, studies usually did not elaborate on the individual components of the study design. The sources of data included were usually appropriate. While most studies utilized basic descriptive and inferential statistics to analyse their data, four out of 18 studies failed to account for confounding variables. The quality of reporting was assessed to be “fair” overall. However, two studies did not address the cross-level bias or have a detailed write-up of the limitations.

4.1. Firearm legislation (KQ1)

Table 2 summarizes identified firearm legislations and their impact on the rates of suicide, femicide, homicide, and mass shootings. Most studies came from the U.S. (n = 151), Canada (n = 17), and Australia (n = 14). Legislation was primarily federal except in the U.S., which included both federal and state-specific laws. Most studies evaluated one law type, however we also included studies that combined the effect of multiple firearm laws together or used an index of strictness to measure rates of homicide and/or suicide. Due to the extreme variability in the methodology of these studies, we did not summarize them in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of firearm legislation organized by country and by legislation type.

| Law | Year | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | ||

| The National Firearms Agreement (NFA) | 1996 | An agreement restricting access to some classes of firearms, regularizing, and tightening state-level licensing laws, and introducing a gun buyback scheme in response to the Port Arthur massacre. Some studies didn’t find an association between the NFA and homicide and suicide, while other studies noted a decrease in rates of homicide and suicide[20], [21], [22], [23], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. |

| National Suicide Prevention Strategy (NSPS) | 1999 | The Australian Government took a nationally coordinated approach to suicide prevention by adopting a whole-of-community approach to suicide prevention to enhance public understanding of suicide and its causes. One study evaluated the NSPS policy impacts on youth suicide and found no support to suggest significant impacts on rand educing youth suicides in Australia[30]. |

| The Weapons Act | 1990 | The Weapons Act requires owners of long arms (rifles and shotguns) to be licensed. One study evaluated the effect of the Weapons Act on firearm suicide rates and noted a reduction in suicide rates, however it is difficult to assess whether the Act was the reason for this decrease[114] |

| Canada | ||

| Bill C-17 | 1991 | Bill C-17 enforced stricter restrictions for firearm purchases (e.g., mandatory waiting periods, screening checks, photographs, personal references) and increased penalties for firearm-related crimes. Overall, studies noted a decrease in homicide and suicide rates following the implementation of Bill C-17, however reduction of firearm suicides was not accompanied by a decrease in overall suicide rates[31], [32], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. |

| Bill C-51 | 1977 | Bill C-51 included requirements for Firearms Acquisition Certificates and Firearms and Ammunition Business Permits. Other changes included search and seizure powers, increased penalties, and new definitions for prohibited and restricted weapons. Overall, studies noted a decrease in rates of firearm-related homicide and suicide following Bill C-51 [31], [32], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42] |

| Bill C-68 | 1995 | Bill C-68 included Criminal Code amendments to enact harsher penalties for serious firearm crimes, the creation of the Firearms Act, a new licensing system, and registration of all firearms, including shotguns and rifles. One study evaluated whether Bill C-68 had a significant impact on female firearm homicide victimization and found that the highest rate of firearm homicide happened among males[31], [32], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42] |

| Gunshot Wounds Reporting Act | 2007 | Nova Scotia act that mandated the reporting of all gunshot wounds by any hospital, facility or individual that treats the victim[25]. |

| USA | ||

| Indiana Gun Removal Law | 2006 | The Indiana Gun Removal Law was enacted to prevent firearm mortality by authorizing police officers to separate firearms from individuals who present imminent or future of injury to self or others. These studies suggested that removal laws were associated with decreases in firearm suicide and homicide[43], [44]. |

| California Ban | 2012 | Since 1967, it has been illegal to openly carry a loaded firearm in public except when engaged in hunting or law enforcement in California, however in 2012, public open carry of unloaded guns became illegal. One study evaluated the effect of the ban on fatal and non-fatal firearm injuries and noted a decrease in homicide rates however, when comparing between-group differences, the rate of change was not statistically different. In comparing California with the controls, there was a statistically significant difference in suicide attempts, with a slight fall in the control states compared with essentially no change in California[45]. |

| National Defense Authorization Act | 2013 | The National Defense Authorization Act allows commanders and clinicians to ask service members about personal firearms and encourage the use of gun locks. One study noted mixed results in that firearms were not used less in suicide attempts within the military post-law change, however, the ratio of non-lethal to lethal suicide attempts increased[46]. |

| Arizona Senate Bill 1108 | 2010 | Bill 1108 modified the existing statutes and permits individuals to carry concealed weapons without a permit and without completion of a training course. One study assessed whether the enactment of Bill 1108 resulted in an increase in gun-related injuries and death, and following the bill, the proportion of gun-related homicides increased by 27 %[47]. |

| Background checks | 1993a | Background checks have been implemented to limit firearm ownership among individuals who would be considered at an elevated risk of violence. Currently, 22 states and the District of Columbia have implemented a policy for background checks for the sale and purchase of firearms. 10 studies evaluated the impact of background check policies on firearm homicides and suicides and all studies noted a reduction in firearm homicide and suicide, especially states with more comprehensive background checks[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58]. |

| The Brady Handfirearm mortality Prevention Act | 1993 | The Brady Hand firearm mortality Prevention Act mandates federal background checks and waiting periods for the purchase of handguns from federally licensed firearm dealers. One study evaluated the impact of the Brady Bill on homicide and suicide rates and did not find any statistically significant changes in homicide or suicide measures when comparing control states with partial treatment states[59], [60]. |

| Child Access Prevention Laws | 1989b | Child access prevention (CAP) laws are state-level laws that govern how firearms are stored in households with minors. Six studies looked at CAP laws and their effect on youth suicide and firearm fatalities and found that states with CAP laws had lower youth suicide rates, however some studies noted an increased risk of adolescent suicide associated with household firearm ownership[61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67]. |

| Comprehensive Anti-Gang Initiative | 2006 | The U.S Department of Justice through the Project Safe Neighborhoods program provided funding to develop an anti-gang initiative to reduce and prevent firearm mortality. One study evaluated the initiative’s impact on gang related firearm mortality and found that cities that implemented the initiative experienced a significant decline in firearm homicide rates post-intervention[68]. |

| Concealed carry laws | 2008 | Concealed carry laws permit civilians to carry a firearm in a concealed manner. Every state in the US allows for concealed carry of a handgun either with or without a permit, however how these permits are obtained vary by jurisdiction. There were many studies that looked at how concealed carry or right-to-carry laws impacted homicide and suicide in multiple states and the conclusions vary[45], [47], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82]. |

| Detroit Gun Ordinance | 1986 | The Detroit City Council enacted an ordinance that created mandatory jail sentence on any individual convicted of illegally concealing a pistol or firearm in the city. An interrupted time-series study noted that the incidence of homicide increased in general after the law was passed and changes in the incidence of firearm homicides was not statistically significant[69]. |

| District of Columbia's Firearms Control Regulations Act | 1976 | The District of Columbia’s Firearms Control Regulations Act restricts the possession of firearms to individuals who hold registration certificates and bans the purchase, sale, transfer, or possession of handguns by civilians[6], [8]. One study noted that the mean frequency of both suicides and homicides by firearms declined by approximately one-quarter in the period following the enactment of the law[83]. |

| Domestic Violence Restraining Orders (DVRO) | 1968 | In response to an increase in firearm use in intimate partner homicide, state and federal laws have been enacted to prohibit the purchase and possession of firearms for those who are subject to an active domestic violence restraining order or convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. Two studies evaluated the impact of intimate partner violence-related firearm restrictive laws on intimate partner homicide. One study found that state level restriction laws are associated with reduction in intimate partner violence among the White population, however this relationship is unclear in among the Black population due to confounding variables[84], while the others found these laws were associated with substantial reductions in homicide of pregnant and postpartum women, especially when coupled with relinquishment law[85]. |

| Federal Assault Weapons Ban | 1994 | The Federal Assault Weapons Ban is a U.S federal law that prohibits the manufacture for civilian use certain semi-automatic firearms (assault weapons) and certain ammunition magazines defined as large capacity. Three studies evaluated the impact of the Federal Assault Weapon ban on mass-shootings in the U.S and all three noted a statistically significant reduction in mass-shooting related homicides during the years the federal ban was in place[86], [87], [88]. |

| Federal Gun Control Act | 1968 | The Gun Control Act prohibits groups (e.g., minors, felons) from possessing or purchasing firearms. One study evaluated the impact of the Federal Gun Control Act of domestic homicides and found that intimate partner gun homicide rate was significantly reduced[89]. |

| Extreme risk protection orders (“red flag” laws) and gun-seizure laws | 1999c | Extreme risk protection orders, also known as firearm mortality restraining orders or “red flag” laws, have been enacted to allow law enforcement and/or families to petition a judge for a removal of firearms from an individual who is deemed a danger to themselves or others. Four studies evaluated the association of state laws with the incidence of firearm-related suicides and three studies found that seizure laws resulted in a decrease in firearm-related suicide and homicide, however, one study noted that firearm removal at the scene of intimate partner violence appeared to increase the likelihood of subsequent intimate violent partner reports[90], [91], [92], [93] |

| Involuntary civil comment statute provisions | 1970 s | Involuntary civil comment (ICC) statutes are the involuntary admission of individuals into mental health care. One study sought to assess whether statutes based solely upon dangerousness criteria versus broad criteria have differential associations related to reducing homicide. The study found that broader ICC criteria were associated with 1.42 less homicides per 100,000 and dangerousness criteria has the strongest association with state homicide rates[94]. |

| Graves Amendment | 1981 | New Jersey's minimum sentencing law mandates a minimum sentence of imprisonment without parole for an individual convicted of a crime. One study examined the percentage of homicides before and after the enactment of the Graves Amendment and noted a decrease in the proportion of homicides[95] |

| Permit to purchase | 1968 | Permit to purchase laws are put in place as a requirement for prospective handgun purchasers to obtain a permit or license prior to purchasing a handgun. This includes a background check, and in some states, a firearm safety training course. Seven studies examined the effects of permit to purchase laws on rates of homicide and suicide and varied in their conclusions. Two studies found no relationship between permit to purchase laws and homicide, one study noted an increase, while the remaining four observed a decrease[96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [82] |

| Saturday Night Special Handgun ban | 1987 | Maryland enacted laws that limited the sales of “Saturday Night Specials, or small handguns. Two studies assessed firearm fatalities following the introduction of the handgun ban, one study noted an overall increase in firearm fatalities in children under 16 and another study modeled the effects of the law and noted a predicted 15 % increase in firearm homicides[101], [105], [106], [107] |

| Stand Your Ground laws | 1994 | Stand Your Ground laws were enacted to provide individuals the option to use deadly force in self-defence so long as they reasonably believe it to be necessary to defend themselves against violent crimes. There were several studies that examined the impact of Stand Your Ground laws on rates of homicide and found an increase in firearm related homicide[96], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117] |

| Waiting period laws | 1994 | Handgun waiting period laws are in place to force a delay between the initiation of the purchase of a handgun and the final acquisition of a firearm, to provide law enforcement with additional time to perform background checks and to prevent acts of violence or suicide attempts. Results were varied with most demonstrating a decrease, either on its own or part of a multi-law study[51], [97], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132]. Two studies, however, noted an increase in firearm-related suicide when Wisconsin repealed the 48-hour waiting period for handgun purchases in 2015[121], [119]. |

| Other countries | ||

| Austria − Legislation reform | 1997 | The Austrian firearms law was enacted following the European Council Directive 91/477/EEC and imposed more strict changes on the acquisition and possession of firearms. Two studies evaluated the impact of the Austrian legislation reform on suicide and homicide rates and both studies concluded an overall decrease in firearm suicide and homicide rates[133], [134]. |

| Colombia − Firearm carry laws | 1993d | In the early 90 s, Columbia enacted laws to set standards and requirements regarding the possession and carrying of firearms, ammunition, explosives, and accessories. Two studies evaluated the effect of firearm restriction on carrying guns on gun-related homicides in Columbia and both studies noted a decrease in firearm-related homicides when the restrictions were in place[135], [136]. |

| Denmark − Firearms Act | 1986 | The Firearms act took effect and implemented stricter laws including requiring licensing for shotguns. One study examined the effect of Danish legislation on homicide and suicide rates and noted that the number of suicides and homicides both decreased following the introduction of the new law, however this decrease could not be attributed to the effect of the law because the number of fatal shotgun cases was similar. The authors noted that it might have been more preventive[137]. |

| Israel − Military policy | 2006 | In 2006, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) changed their policy as part of a suicide prevention program to mandate that soldiers must leave their weapons at their bases when heading home for weekend leave. One study assessed the effect of reduced firearm access on suicide and found a 40 % decline in the number of suicide after the policy change when reducing access to firearms during the weekend[138]. |

| Montenegro − Montenegrin Law | 2007 | A new law in Montenegro enforced that firearms are only permitted in homes or bought from individuals who have expressed written permission from the police. A time-trend analysis evaluated the effects of this new law comparing firearm and knife homicides and found a significant decrease in firearm homicides but saw an increase in homicides committed with a knife[139]. |

| New Zealand − Amendment to the Arms Act | 1992 | The Amendment to the Arms Act changed regulations surrounding access to firearms from liberal to more restrictive, including licensing, knowledge of the Firearms Code test, and assessment by police as “fit” to hold a firearms license. One study examined the impact of introducing more restrictive legislation and found that the mean annual rate of firearm related suicides decreased by 46 % for the total population[140]. |

| South Africa − Firearms Control Act | 2000 | The Firearms Control Act aimed to address firearm violence by removing illegally owned firearms from circulation, stricter regulation of legally owned firearms, and stricter firearm licensing requirements. One time-trend analysis found that firearm homicide increased at 13 % annually from 1994 through 2000, and decreased by 15 % from 2003 through 2006, corresponding with changes in firearm availability in 2001, 2003, 2007 and 2011[141]. |

| Switzerland − Army XXI Reform | 2003 | The Army XXI Reform was enacted to reduce military troops by discharging military personnel early, impacting the availability of military guns, as well as increasing the fee for solider to purchase their military gun following their service and licensing requirements for gun owners. One study assessed the patterns of overall suicide and homicide rates following the reform and found an overall reduction in both overall suicide rate and firearm suicide rate. The authors estimated 22 % of reduction in firearm suicide rate was substitute by other suicide methods[142]. |

– following enactment of the Brady Act.

– first Child Access Prevention (CAP) law was passed in Florida, US.

– First Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) was passed in Connecticut, US.

– DESEPAZ − Development, Security, and Peace Program.

4.2. Gun removal/seizure laws

Two cross-sectional studies[43], [44] and one mixed-method report[143] reviewed Indiana and Connecticut’s risk-based seizure laws on firearm mortality. These studies suggested that removal laws were associated with decreases in firearm suicide and homicide. Indiana’s firearm seizure law was associated with a 7.5 % reduction in firearm suicides in the ten years post-enactment. Connecticut’s law was associated with an immediate 1.6 % reduction in firearm suicides and then a 13.7 % reduction in the post Virginia Tech period, referring to the mass shooting at Virginia Tech in Aril 2007[43]. A California study looked at Gun Violence Restraining Orders (GVRO) and although found a decrease in firearm-violence, the placebo comparison showed the same result, and therefore felt not to be due to the GVRO[144]. A 2022 observational study evaluated the impact of nullifying SB-1487, which was an Arizona law put in place in 2016 that required confiscated firearms to be destroyed. Instead, these firearms were getting auctioned off to the public, which resulted in a 1.13/100,000 increase in annual firearm deaths by suicide[90]. A Canadian study looked at firearm injury rates before and after mandating a Gunshot Wounds Reporting Act and found no association[145]. In Montenegro, a 2007 law that restricted firearm access and allowed removal from property unless there was police permission was associated with a decrease in firearm homicides[139]. Finally, the Australian buy-back laws were evaluated recently and were estimated to prevent 35 firearm-related homicides and 77 firearm-related suicides per year[146].

4.3. Firearm carry laws

There were many studies analyzing concealed carry weapon (CCW) state laws in the U.S[45], [47], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82]. A time-trend analysis found no statistically significant changes in incidence of firearm homicides in Michigan after introducing the Detroit Gun Ordinance[69], while one cohort study noted an increase in gun-related incidents in Arizona following Arizona’s Senate Bill[47]. An older study looked at the 1981 ‘Graves Amendment, which enforced a minimum sentence without parole for subjects committing crimes with a firearm, and found a decrease in homicides and suicides after enforcement[95]. One study noted a decrease in suicide and homicide rates following the California Ban using a time-trend analysis[45] and two cross-sectional studies that evaluated gun-carrying restrictions in Colombia noted a decrease in rates of homicide following restrictions[135], [136]. Another time-trend analysis evaluated the impact of switching from “shall-issue’ to ‘permitless’ CCW laws on officer involved shootings and noted a 12.9 % increase in firearm violence victims[76]. A reciprocal county analysis found that an increase in CCW licenses issued was associated with an increase in total firearm homicides[80]. Shall-issue CCW laws were found to be associated with a 9.5 % increase in firearm assault rates, which increased further if CCW licenses were issued to previous misdemeanants[77]. When comparing ‘open carry’ states to ‘permitless open carry’ states, ‘permitless open carry’ states were found to have a significantly higher firearm death rate[78], [79]. It was also noted that transitioning from ‘open carry’ to ‘permitless open carry’ was associated with an increase in total suicide rate[34]. A study from West Virginia looked at the impact of HB4145, a law that legalized permitless CCW and found that homicides and suicides increased by 48 % and 22 %, respectively[81]. In contrast, twelve studies evaluated Stand Your Ground (SYG) laws in the U.S. and all noted an increase in rates of suicide and homicide [96], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], however one study noted an increase across all states despite enactment of SYG laws[114].

4.4. Firearm acquisition laws

Studies evaluating firearm acquisition laws included permit to purchase laws [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [82], Saturday night special laws [101], [105], [106], [107], waiting period laws[51], [97], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], background checks[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act [59], [60], Federal Gun Control Act[89], [147], intimate partner violence restrictive laws[84], [85], and the District of Columbia’s Firearm Control Regulations Act[83]. Most studies evaluating firearm acquisition laws noted a decrease in rates of homicide and suicide, apart from three studies that noted an increase [101], [105], [119] or four noting no association[60], [103], [107], [52]. A Wisconsin study looking at repeal of waiting period laws noted an increase in suicide by handgun by 6.4 %[121].

In Australia, thirteen cross-sectional and time-trend analyses looked at the National Firearms Agreement[20], [21], [22], [23], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29] and the Weapons Act[148], where all studies observed a decrease in rates of homicide and suicide except for one which used structural break testing – an abrupt change during a time-series – and found no association[20].

4.5. Firearm storage laws

Five cross-sectional[61], [62], [63], [64], [65] and two time-trend analyses[66], [67] evaluated the impact of child access prevention (CAP) laws in the U.S. and found lower rates of suicide and homicide among youth in states that had enacted safe storage laws.

4.6. Military firearm laws

Three studies looked at laws targeting access to military-issued firearm use among military personnel when not on duty in the U.S. (National Defence Authorization Act) [46], Israel (Military policy) [138], and Switzerland (Army Reform) [142] on suicide rates. The American study found a 5 % decrease in firearm suicide deaths from 2011 to 2015[46]. This effect was expected to be greater and could have been contaminated by high rates of personal firearm ownership. The studies from Israel and Switzerland also noted a decrease in suicide rates[138], [142].

4.7. Multi-component laws

We found 40 studies that either evaluated federal laws that target multiple components of firearm legislation or looked at multiple laws at once, such as background checks, waiting periods, and/or firearm carry laws. In Canada, 12 studies looked at the impact of Bill C-17, Bill C-51, and Bill C-68 on rates of suicide and homicide and all studies noted a decrease apart from one[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. In Austria, two studies analyzed the impact of the legislation reform on firearm suicides and homicide and both noted a decrease in rates in both men and women[133], [134]. Studies examining firearm legislation in Denmark[137], New Zealand[140], and South Africa[141] noted a decrease in rates of homicide and suicide after enactment of stronger laws.

There were many studies from the U.S. that analyzed various combinations of laws and their collective impact of firearm violence[19], [104], [106], [122], [124], [125], [18], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153]. One study from The RAND Corporation synthesized available data from 18 state firearm policies and found a reduction in firearm homicide associated with CAP and safe storage laws[19], although few policies had been the subject of methodologically rigorous investigation. Five studies evaluated several types of restrictive laws and found an association with reduction in homicides and suicides by firearm[104], [106], [124], [151], [152]. Alternatively, another study analyzed the permissiveness of legislation and concluded that a 10-point increase in permissiveness correlated with a 2 % increase in suicides by firearm[150]. One study examined specific firearm laws and their impact on adjacent states, and found that permit, record keeping, and prohibition laws were associated with reduced firearm-related deaths in adjacent states[104]. Another study instead identified potential gaps in firearm legislation by comparing multiple restrictive and access-related laws across the U.S. CAP laws, assault weapons and large-capacity magazines restrictions, anticipatory laws, and CCW permit laws were found to be the most effective law types[149].

Three studies found mixed results[106], [122], [125] and one found no association[123]. Of these three, one was a systematic review specifically assessing for racial differences in firearm policy effects, which found mixed results based on law-type and baseline racial disparities[125]. The second was a cross-sectional study analyzing by firearm type, and found that the impact of background checks, waiting periods, and Saturday Night Bans individually was influenced by firearm-type, however overall found no significant difference in mean assault mortality rate by all firearms[106]. Finally, the third study included external factors, again finding mixed results across law-types[122].

4.8. Government firearm prevention strategies

Three studies looked at government initiatives and their impact on preventing firearm violence. Involuntary civil comment (ICC) statutes are the involuntary admission of individuals into mental health care. One study sought to assess whether statutes based solely upon dangerousness criteria versus broad criteria have differential associations related to reducing homicide. The study found that broader ICC criteria were associated with 1.42 less homicides per 100,000 and dangerousness criteria had the strongest association with state homicide rates[94].

One study in the U.S. analyzed whether the Comprehensive Anti-Gang Initiative impacted homicide associated with gang violence and found a significant decline in gun homicide rates post-initiative[68]. However, in Australia, one study evaluated the impact of the government’s National Suicide Prevention Strategy and found no support to suggest significant impacts on reducing youth suicides[30].

4.9. Strictness of legislation

There were 21 studies that evaluated legislative strength related to state-level firearms laws in the US[5], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173]. Some studies used a pre-defined scale or index such as the Guttman scale of strictness, Brady Campaign scorecard, or the Giffords Law scorecard, while other studies created their own measure of strictness, usually based on the number of firearm laws in a particular state. Almost all studies observed a decrease in homicide and suicide rates in states that have stricter firearm legislation. Cross-sectional studies published in 2021, noted a significant association between states with more restrictive gun laws and a reduction in suicide and homicide rates[172], [173].

4.10. Barriers and facilitators (KQ2)

We found eleven studies that directly evaluated factors that impacted the uptake of legislation in different jurisdictions across the U.S. [79], [90], [91], [92], [93], [120], [143], [144], [174], [175], [176]. One study noted funding as the largest barrier to the implementation of GVROs[144]. Other barriers to implementation included risk of violence, interagency coordination, local firearm ideology/normative practice, readiness for implementation, and law enforcement culture[144]. Four studies evaluated barriers to implementing extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws[90], [91], [92], [93]. One found that state legislators’ believed that ERPO laws violated civil liberties, demonstrating how ideologies can impact the design and implementation of firearm legislation[91]. Other barriers included lack of knowledge, strong opinions from politicians, implementation process and petitioner distress, among others[90], [92], [93]. Another study suggested that community education may be important for reducing local, specific risk[174], while another study suggested focusing on addressing societal issues, such as crime and poverty to reduce firearm violence in African American communities[175]. Stakeholders noted gun storage as a significant barrier to acting on Connecticut’s gun removal law and concerns surrounding the cumbersome aspects of the risk-warrant process[143]. Finally, another study found that adjacent states tend to adopt similar firearm laws. This same study also found that permissive laws are more likely to be enacted than restrictive laws yet both will diffuse across state borders and that this enactment is influenced by government ideology[120].

5. Discussion

This scoping review found numerous legislative approaches to addressing firearm morbidity and mortality, including preventative, prohibitive, and more tailored strategies focused on identifying high risk individuals, both in the U.S. and internationally. Overall findings suggest that different law types can have various effects on rates of firearm homicide, suicide, and femicide. Differences in observed outcomes can be attributed to a lack of robust design, uneven implementation, and poor evaluation of legislation. We found that in the U.S., similar law types were associated with varying outcomes depending upon the state in which they were implemented, as seen with gun removal and concealed carry state laws[43], [44], [45], [47], [69], [135], [136], [177]. State-specific amendments, such as additional penalties or permit requirements, were found to contribute to the desired effect of reducing firearm violence [45], [69]. Permit to purchase laws [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [82], waiting periods [51], [97], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [178], [179], and background checks[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58] more consistently were associated with reductions in firearm violence [6], [180]. These policies aim to reduce firearm access to high-risk individuals[101], [181] however, despite these laws, prohibited offenders can still access firearms[154], from within the same home [182] or through underground markets [183], undermining the original intent of these laws.

Promising in firearm legislation are ERPOs, which aim to prevent firearm deaths through seizing firearms from high-risk individuals. Studies on ERPOs demonstrated an association with decreases in firearm suicide and homicide[184], [185], [186]. As of March 2024, 21 states and Washington DC had enacted ERPOs[187]. A descriptive study analyzed 662 ERPO cases in response to the threat of killing at least three people and found that in 84 % of cases, ERPOs may have prevented mass shooting events[188].

SYG laws [96], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117] and ‘Sunset Provisions’[86], [87], [88] are the only laws repeatedly associated with increased mortality. SYG laws legally allow firearm violence in self-defence as a first, rather than last, resort[189]. States with SYG laws appear to be more tolerant of guns for self defense and demonstrated the largest increase in firearm mortality[190], [191]. A ‘sunset provision’ is an expiry date on legislation, whereby after a specific date, the legislation or part thereof is repealed. The most often cited example of this is the 2004 lift on the US Federal Assault Weapon (FAW) Ban of 1994[86], [87], [88]. One study demonstrated that mass-shooting fatalities were 70 % less likely to occur during the federal ban period. It has been estimated that without this sunset provision, 70 % of subsequent mass shooting deaths may have been prevented [86]. In the US a FAW ban is currently under review[192].

Most studies on restrictive, federal-level legislation were associated with a reduction in firearm mortality. We identified several Canadian studies[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41] looking at homicide and suicide rates after implementation of Bills C-51, 17 and 68, enacted in 1977, 1991 and 1995, respectively, that showed a trend toward reduced mortality. One study noted a decrease in suicide by firearm but an increase in suicide attempts by other methods (called method substitution) [193]. Notably, the majority of suicide attempts without a gun did not result in death[193], implying that means restriction is an effective, population-level intervention that reduces lethality from suicide attempts through method substitution[41]. In Canada, Bill C-21 is currently under review and proposes clearer definitions of prohibited assault-style firearms, red flag laws similar to ERPOs and a national freeze on the legal sale of handguns[194].

Legislation resulting after the Port Arthur Massacre (Australia, 1996), the Dunblane Massacre (Scotland, 1996) and more recently, the Christchurch Mosque shootings (New Zealand, 2019) and Nova Scotia shooting of April 2020 are historic examples of the strength of restrictive, national bans. These massacres led to the National Firearms Agreement of Australia [29], the Firearms (Amendment) No 2 Act of 1997 [195], and the Arms Amendment Act of 2019 [196], and the Canadian Mass Casualty Commission (MCC) report[197]. Amendments included stricter registries, mandatory buyback programs and inclusion of semi-automatic and privately-owned firearms as prohibited. After implementing the NFA, with mass shootings defined as four victims, none had occurred in Australia until the 2019 Darwin shooting. We acknowledge that establishing clear causality is challenging as these laws are often examined in their entirety without a control group for comparison. Particularly for the NFA, trends were already decreasing prior to implementation. Notwithstanding this limitation, inflection points in the data demonstrate changes in rate of mortality corresponding with implementation of these laws[23].

Firearm legislation can reflect ideology and normative practice of the jurisdiction[198], [199]. This results in policies or amendments in response to anti- or pro-gun federal and sub-federal laws. Examples include Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986 [200] and the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act of 2005[201], compared to the ‘Equal Access to Justice for Victims of Gun Violence Act’ of 2021, currently under review [202].

We identified that competing firearm legislation implemented from different levels of government is far less effective than national level legislation. For example, the Federal Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1994 was designed to delay sales by Federal Firearm Licensees through a mandatory five-day waiting period and background check prior to purchase[60]. State-level exemptions and replacement of waiting periods with the National Instant Criminal Background Check system, which private sellers could not access[60], weakened the effect of this federal law. The Brady Act had the greatest impact in states that still had mandatory waiting periods and background checks[118], [119]. Similarly in Australia, states with unregulated unlicensed gun clubs, regional age requirements and ‘cooling-off’ periods undermine the strength of the national ban[203].

Finally, the impact of federal legislation is as strong as its’ ‘weakest state’, defined by strength or strictness of legislation[154]. This can be seen both in ‘illegal firearm transfer’ whereby states with stricter legislation experience an influx of firearms from states with weaker legislation[204], and with higher rates of firearm ownership, whereby stricter legislation is associated with lower household firearm ownership[154].

A public health approach requires a multidisciplinary, coordinated strategy, supported by high quality research. This principle has been emphasized by the Canadian Mass Casualty Commission (MCC) report and the American College of Surgeons Summit report. These reports give recommendations for firearm access, specific weapons prohibitions, license control, and revocation[197]. They also included recommendations for interventions related to risk factor screening, education around injury prevention, and addressing societal factors in higher-risk communities disproportionately impacted by violence[205]. The perspective that legislation should include gun ownership as a conditional privilege and requirement for a shift in culture around gun safety were included in the MCC report[197].

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD has suggested frameworks to evaluate legislation[206]. There are several barriers impeding strong legislative design and uptake including poor enforcement of existing laws, limited funding for research, ideological contentions, constitutional challenges, and a lack of public education[144], [207], [208]. A high-quality law must have clear outcomes that target well-established public health concerns and account for these barriers. High quality evidence should inform legislative process and on-going iterative research to test outcomes will result in evidence-informed policy[206], [207], [209].

The presence of a firearm in the home makes it five times more likely that a woman will die in the setting of domestic violence[210] and about three to four times more likely that a youth will die in a suicide attempt than if a gun were not present[211]. The presence of assault style rifles makes mass shootings far more lethal and injurious than if other weapons are used[212]. Most countries outside of the U.S. enact federal restrictive firearm laws which in many studies have been found to decrease rates of firearm mortality[133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [139], [140], [141], [142]. These laws include restrictions on the sale and possession of the most lethal types of weapons, including background checks and safe storage rules. These countries tend to have far lower per capita firearm injury and mortality rates, and often a single catastrophic shooting is sufficient to invoke new, federal legislation[29]. It is imperative these nations continue to guard the policy advancements and cultural changes that make societies safer. International firearm violence research is essential for developing effective firearm policy as part of a collective attempt to reduce gun violence globally. It is essential that all legislative bodies globally view gun violence through the lens of public health.

We acknowledge limitations of our scoping review. We identified many laws for which we could not determine effectiveness due to poor study quality or heterogeneity in study design, poor law quality, implementation, and uptake. Temporal changes in normative practice and legislation further complicate our ability to interpret the findings. These limitations highlight the need for future research to define firearm legislation, regulation and implementation that reduces firearm mortality.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the evidence from this review demonstrates several key points:

-

1.

Firearm mortality is influenced by law type, national or sub-national implementation, cultural practices, and the quality and durability of the law.

-

2.

Restrictive, national level bans without sunset provisions seem to be most effective for reducing firearm mortality.

-

3.

Prioritizing prevention with revocation of firearms or suspension of licenses from high-risk perpetrators may reduce deaths from suicides, mass shooting, and domestic violence, particularly once barriers to implementation are addressed.

-

4.

In the U.S., state laws are sometimes designed to undermine federal laws including those revering background checks and waiting periods. Safe storage laws and negligent CAP laws are also often state-specific and instead aim to support the effect of restrictive, federal gun laws.

-

5.

Notably, there were far fewer non-U.S. studies identified in our review. This observation could be explained by the fact that non-U.S. countries have significantly lower rates of firearm violence making this a less-studied public health topic.

Like the study of major illnesses, the study of firearm injury and mortality requires prospective, long-term, reliable data collection through the collaboration of multiple professional disciplines. Epidemiological research and evaluation of legislation is a dynamic process that is fundamental to understanding outcomes of firearm violence. Quality data collection will result in high quality research which will drive effective legislation. High quality research will inform public health science and drive policy and legislation that will reduce the largely preventable burden of injury and death from guns.

Funding

Funding for this protocol and subsequent scoping review is provided by the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Evidence Alliance and in part by St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto.

Declaration of competing interest

Dr. Najma Ahmed is the founder of Canadian Doctors for Protection from Guns (CDPG), a group dedicated to preventing death from firearms by advocating for means restriction through the introduction of legislation and by encouraging research on the epidemiology of firearm injury and effectiveness of reduction strategies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Brianna Greenberg: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Alexandria Bennett: . Asad Naveed: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Raluca Petrut: Data curation. Sabrina M. Wang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Niyati Vyas: Data curation. Amir Bachari: Data curation. Shawn Khan: Data curation. Tea Christine Sue: Data curation. Nicole Dryburgh: Writing – review & editing. Faris Almoli: Data curation. Becky Skidmore: Writing – review & editing. Nicole Shaver: Writing – review & editing. Evan Chung Bui: Data curation. Melissa Brouwers: Writing – review & editing. David Moher: Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. Julian Little: Writing – review & editing. Julie Maggi: Writing – review & editing. Najma Ahmed: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kaitryn Campbell, MLIS, MSc (St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton/ McMaster University) for peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy. We also thank Peter Masiakos, MS, MD, FACS, FAAP (Mass General and Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School) for his guidance regarding post-legislation scrutiny and sunset provisions in the U.S.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2024.100127.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Werbick M., Bari I., Paichadze N., Hyder A.A. Firearm violence: a neglected “Global Health” issue. Glob Health. 2021;17:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00771-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All Injuries [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/injury.htm.

- 3.Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. United States Gun Deaths: 2020 [Internet]. The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://efsgv.org/state/united-states/.

- 4.Government of Canada. Firearms and violent crime in Canada, 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-005-x/2022001/article/00002-eng.htm.

- 5.Kalesan B., Mobily M.E., Keiser O., Fagan J.A., Galea S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: a cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1847–1855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santaella-Tenorio J., Cerdá M., Villaveces A., Galea S. What do we know about the association between firearm legislation and firearm-related injuries? Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):140–157. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015.

- 12.McGowan J., Sampson M., Salzwedel D.M., Cogo E., Foerster V., Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CADTH. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 25]; Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence.

- 14.Covidence. Better systematic review management [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.covidence.org.

- 15.The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research – Technical Assistance for users of the CFIR framework [Internet]. [cited 2021 Dec 16]. Available from: https://cfirguide.org/.

- 16.Dufault B., Klar N. The quality of modern cross-sectional ecologic studies: a bibliometric review. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(10):1101–1107. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendez-Brito A., El Bcheraoui C., Pozo-Martin F. Systematic review of empirical studies comparing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19. J Infect. 2021;83(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betran A.P., Torloni M.R., Zhang J., Ye J., Mikolajczyk R., Deneux-Tharaux C., et al. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart R, Morral AR, Ramchand R, Charbonneau A, Williams J, Smucker S, et al. The Science of Gun Policy: A Critical Synthesis of Research Evidence on the Effects of Gun Policies in the United States, Third Edition [Internet]. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2023. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA243-4.html.

- 20.Lee W.S., Suardi S. The australian firearms buyback and its effect on gun deaths. Contemp Econ Policy. 2010;28(1):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ukert B., Andreyeva E., Branas C.C. Time series robustness checks to test the effects of the 1996 Australian firearm law on cause-specific mortality. J Exp Criminol. 2018;14(2):141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilmour S., Wattanakamolkul K., Sugai M.K. The effect of the australian national firearms agreement on suicide and homicide mortality, 1978–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):1511–1516. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPhedran S. An evaluation of the impacts of changing firearms legislation on australian female firearm homicide victimization rates. Violence Women. 2018;24(7):798–815. doi: 10.1177/1077801217724450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snowdon J., Harris L. Firearms suicides in australia. Med J Aust. 1992;156(2):79–83. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb126416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozanne-Smith J., Ashby K., Newstead S., Stathakis V.Z., Clapperton A. Firearm related deaths: the impact of regulatory reform. Inj Prev. 2004;10(5):280–286. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.004150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman S., Alpers P., Agho K., Jones M. Australia’s 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings. Inj Prev. 2006;12(6):365–372. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klieve H., Barnes M., De Leo D. Controlling firearms use in Australia: has the 1996 gun law reform produced the decrease in rates of suicide with this method? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(4):285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapman S., Alpers P., Jones M. Association between gun law reforms and intentional firearm deaths in australia, 1979–2013. JAMA. 2016;316(3):291–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman S., Stewart M., Alpers P., Jones M. Fatal firearm incidents before and after australia’s 1996 national firearms agreement banning semiautomatic rifles. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):62–64. doi: 10.7326/M18-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPhedran S., Baker J. Suicide prevention and method restriction: evaluating the impact of limiting access to lethal means among young Australians. Arch. 2012;16(2):135–146. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leenaars A.A., Lester D. Effects of gun control on homicide in Canada. Psychol Rep. 1994;75(1 Pt 1):81–82. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leenaars A.A., Lester D. The impact of gun control on suicide and homicide across the life span. Can J Behav Sci Rev Can Sci Comport. 1997;29(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leenaars A.A., Lester D. Gender and the impact of gun control on suicide and homicide. Arch Suicide Res. 1996;2(4):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lester D., Leenaars A. Suicide rates in Canada before and after tightening firearm control laws. Psychol Rep. 1993;72(3 Pt 1):787–790. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrington P.J., Moyer S. Gun control and suicide in Ontario. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(4):606–608. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridges F.S. Gun control law (Bill C-17), suicide, and homicide in Canada. Psychol Rep. 2004;94(3 Pt 1):819–826. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.819-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung A.H., Dewa C.S. Current trends in youth suicide and firearms regulations. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(2):131–135. doi: 10.1007/BF03403676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caron J. Gun control and suicide: possible impact of Canadian legislation to ensure safe storage of firearms. Arch. 2004;8(4):361–374. doi: 10.1080/13811110490476752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gagne M., Robitaille Y., Hamel D., St-Laurent D. Firearms regulation and declining rates of male suicide in Quebec. Inj Prev. 2010;16(4):247–253. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.022491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caron J., Julien M., Huang J.H. Changes in suicide methods in Quebec between 1987 and 2000: the possible impact of bill C-17 requiring safe storage of firearms. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(2):195–208. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McPhedran S., Mauser G. Lethal firearm-related violence against Canadian women: did tightening gun laws have an impact on women’s health and safety? Violence Vict. 2013;28(5):875–883. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett N., Karkada M., Erdogan M., Green R.S. The effect of legislation on firearm-related deaths in Canada: a systematic review. CMAJ Open. 2022 Jun;10(2):E500–E507. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kivisto A.J., Phalen P.L. Effects of risk-based firearm seizure laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):855–862. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swanson J.W., Easter M.M., Alanis-Hirsch K., Belden C.M., Norko M.A., Robertson A.G., et al. Criminal Justice and Suicide Outcomes with Indiana’s Risk-Based Gun Seizure Law. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):188–197. doi: 10.29158/JAAPL.003835-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Callcut R.A., Robles A.M.J., Mell M.W. Banning open carry of unloaded handguns decreases firearm-related fatalities and hospital utilization. Trauma Surg. 2018;3(1):e000196. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anestis M.D., Daruwala S.E., Carey N. Suicide attempt trends leading up to and following gun lock changes in the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2019;11(2):100–108. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ginwalla R., Rhee P., Friese R., Green D.J., Gries L., Joseph B., et al. Repeal of the concealed weapons law and its impact on gun-related injuries and deaths. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(3):569–574. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruddell R., Mays G. State background checks and firearms homicides. J Crim Justice. 2005;33(2):127–136. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumner S.A., Layde P.M., Guse C.E. Firearm death rates and association with level of firearm purchase background check. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sen B., Panjamapirom A. State background checks for gun purchase and firearm deaths: an exploratory study. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anestis M.D., Selby E.A., Butterworth S.E. Rising longitudinal trajectories in suicide rates: The role of firearm suicide rates and firearm legislation. Prev Med. 2017;100:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kagawa R.M.C., Castillo-Carniglia A., Vernick J.S., Webster D., Crifasi C., Rudolph K.E., et al. Repeal of comprehensive background check policies and firearm homicide and suicide. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):494–502. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crifasi C.K.M.F.M. Association between Firearm Laws and Homicide in Urban Counties. J Urban Health. 2018;95:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0273-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castillo-Carniglia A.K.R. California’s comprehensive background check and misdemeanor violence prohibition policies and firearm mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;30:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goyal M.K., Badolato G.M., Patel S.J., Iqbal S.F., Parikh K., McCarter R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):08. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCourt A.D.C.C. Purchaser licensing, point-of-sale background check laws, and firearm homicide and suicide in 4 US states, 1985–2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1546–1552. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaufman E.J., Morrison C.N., Olson E.J., Humphreys D.K., Wiebe D.J., Martin N.D., et al. Universal background checks for handgun purchases can reduce homicide rates of African Americans. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(6):825–831. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kagawa R., Charbonneau A., McCort C., McCourt A., Vernick J., Webster D., et al. Effects of comprehensive background-check policies on firearm fatalities in 4 states. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192(4):539–548. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwon I.W.G., et al. The effectiveness of gun control laws: multivariate statistical analysis. Am J Econ Sociol. 1997;56:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ludwig J., Cook P.J. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA. 2000;284(5):585–591. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gius M. The impact of minimum age and child access prevention laws on firearm-related youth suicides and unintentional deaths. Soc Sci J. 2015;52(2):168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cummings P., Grossman D.C., Rivara F.P., Koepsell T.D. State gun safe storage laws and child mortality due to firearms. JAMA. 1997;278(13):1084–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kappelman J., Fording R.C. The effect of state gun laws on youth suicide by firearm: 1981–2017. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(2):368–377. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kivisto A.J., Kivisto K.L., Gurnell E., Phalen P., Ray B. Adolescent suicide, household firearm ownership, and the effects of child access prevention laws. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(9):1096–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chammas M., Byerly S., Lynde J., Mantero A., Saberi R., Gilna G., et al. Association between child access prevention and state firearm laws with pediatric firearm-related deaths. J Surg Res. 2023;281:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2022.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster D.W., Starnes M. Reexamining the association between child access prevention gun laws and unintentional shooting deaths of children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1466–1469. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azad H.A., Monuteaux M.C., Rees C.A., Siegel M., Mannix R., Lee L.K., et al. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 years, 1991–2016. Jama Pediatr. 2020;174(5):463–469. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McGarrell E.F., Corsaro N., Melde C., Hipple N.K., Bynum T., Cobbina J. Attempting to reduce firearms violence through a Comprehensive Anti-Gang Initiative (CAGI): An evaluation of process and impact. J Crim Justice. 2013;41(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Carroll P.W., Loftin C., Waller J.B., Jr, McDowall D., Bukoff A., Scott R.O., et al. Preventing homicide: an evaluation of the efficacy of a Detroit gun ordinance. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(5):576–581. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carter J.G., Binder M. Firearm violence and effects on concealed gun carrying: Large debate and small effects. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(19):3025–3052. doi: 10.1177/0886260516633608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crandall M., Eastman A., Violano P., Greene W., Allen S., Block E., et al. Prevention of firearm-related injuries with restrictive licensing and concealed carry laws: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5):952–960. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doucette M.L., Crifasi C.K., Frattaroli S. Right-to-carry laws and firearm workplace homicides: A longitudinal analysis (1992–2017) Am J Public Health. 2019;109(12):1747–1753. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamill M.E., Hernandez M.C., Bailey K.R., Zielinski M.D., Matos M.A., Schiller H.J. State level firearm concealed-carry legislation and rates of homicide and other violent crime. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.08.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hepburn L., Miller M., Azrael D., Hemenway D. The effect of nondiscretionary concealed weapon carrying laws on homicide. J Trauma. 2004;56(3):676–681. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000068996.01096.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siegel M., Xuan Z., Ross C.S., Galea S., Kalesan B., Fleegler E., et al. Easiness of legal access to concealed firearm permits and homicide rates in the united states. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1923–1929. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doucette M.L., Ward J.A., McCourt A.D., Webster D., Crifasi C.K. Officer-involved shootings and concealed carry weapons permitting laws: analysis of gun violence archive data, 2014–2020. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2022 Jun;99(3):373–384. doi: 10.1007/s11524-022-00627-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doucette M.L., McCourt A.D., Crifasi C.K., Webster D.W. Impact of changes to concealed-carry weapons laws on fatal and nonfatal violent crime, 1980–2019. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192(3):342–355. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grimsley E.A., Torikashvili J.V., Janjua H.M., Read M.D., Kuo P.C., Diaz J.J. Transition to permitless open carry and association with firearm-related suicide. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238(4):681–688. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grimsley E.A., Read M.D., McGee M.Y., Torikashvili J.V., Richmond N.T., Janjua H.M., et al. Association of state-level factors with rate of firearm-related deaths. Surg Open Sci. 2023;14:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.sopen.2023.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stansfield R., Semenza D., Silver I. The relationship between concealed carry licenses and firearm homicide in the US: A reciprocal county-level analysis. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2023;100(4):657–665. doi: 10.1007/s11524-023-00759-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lundstrom E.W., Pence J.K., Smith G.S. Impact of a permitless concealed firearm carry law in west virginia, 1999–2015 and 2016–2020. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(11):1163–1166. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]