Abstract

Background

There has been a significant surge in animal studies of stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) therapy for the treatment of premature ovarian failure (POF) but its efficacy remains unknown and a comprehensive and up-to-date meta-analysis is lacking. Before clinical translation, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the overall impact of stem cell-derived EVs on POF.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science were searched up to February 18, 2024. The risk of bias was evaluated according to Cochrane Handbook criteria, while quality of evidence was assessed using the SYRCLE system. The PRISMA guidance was followed. Trial sequential analysis was conducted to assess outcomes, and sensitivity analysis and publication bias analysis were performed using Stata 14.

Results

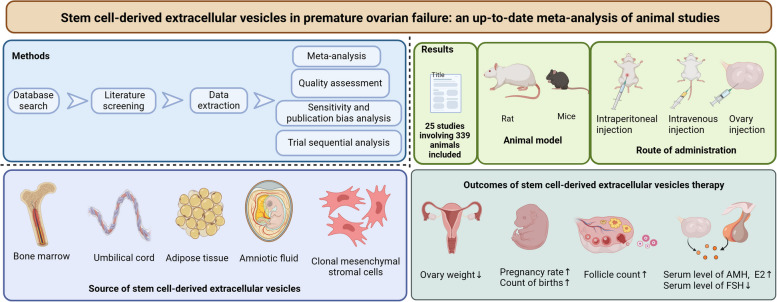

Data from 25 studies involving 339 animals were extracted and analyzed. The analysis revealed significant findings: stem cell-derived EVs increase ovary weight (SMD = 3.88; 95% CI: 2.50 ~ 5.25; P < 0.00001; I2 = 70%), pregnancy rate (RR = 3.88; 95% CI: 1.94 ~ 7.79; P = 0.0001; I2 = 0%), count of births (SMD = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.31 ~ 3.04; P < 0.00001; I2 = 69%) and counts of different types of follicles. In addition, it elevates the level of AMH (SMD = 4.15; 95% CI: 2.75 ~ 5.54; P < 0.00001; I2 = 88%) and E2 (SMD = 2.88; 95% CI: 2.02 ~ 3.73; P < 0.00001; I2 = 80%) expression, while reducing FSH expression (SMD = -5.05; 95% CI: -6.60 ~ -3.50; P < 0.00001; I2 = 90%). Subgroup analysis indicates that the source of EVs, animal species, modeling method, administration route, and test timepoint affected efficacy. Trial sequential analysis showed that there was sufficient evidence to confirm the effects of stem cell-derived EVs on birth counts, ovarian weights, and follicle counts. However, the impact of stem cell-derived EVs on pregnancy rates needs to be further demonstrated through more animal experimental evidence.

Conclusions

Stem cell-derived EVs demonstrate safety and efficacy in treating POF animal models, with potential improvements in fertility outcomes.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42024509699.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13048-024-01489-y.

Keywords: Premature ovarian failure, Extracellular vesicles, Stem cell, Meta-analysis, Trial sequential analysis

Background

Premature ovarian failure (POF), or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), is the cessation of ovarian function before the age of 40, affecting approximately 1% of women within this age group. More recently, a global incidence of about 3.7% of women of reproductive age were reported diagnosed with POF/POI [1–4]. POF is among the leading causes of female infertility prior to 40 years of age, and is characterized by lack of mature follicle, amenorrhea, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism [5]. Additionally, it is associated with an increased risk of long-term complications such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, sexual dysfunction and psychological distress. While the etiology of POF remains unidentified in most cases, it has been linked to genetic disorders [6, 7], autoimmunity [8, 9], chemotherapy and radiotherapy [10, 11], and environmental factors. POF is a devastating diagnosis for reproductive-aged women, and currently, preventive and therapeutic options are limited. Although hormone replacement therapy (HRT) remains the mainstay of management, it primarily alleviates symptoms without effectively restoring ovarian function [12]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for novel and effective therapeutics for POF.

In recent years, stem cell therapy has shown great promise in wide-ranging clinical applications and regenerative medicine, showing potential in restoring ovarian function in numerous pre-clinical studies [13, 14]. However, it has been suggested that stem cells do not directly differentiate into granulosa cells but instead exert their effects through paracrine mechanisms, at least in part by secretion of extracellular vesicles (EVs), representing a more robust therapeutic product than intact cells [15–19]. EVs are nano-sized, lipid bilayer-enclosed structures capable of carrying and transferring proteins, lipids, RNAs, metabolites, growth factors and cytokines, playing a critical role in cell–cell communication [20, 21]. Compared with their parental cells, stem cell-derived EVs not only retain similar functions but also exert higher biological stability, lower immunogenicity and are easier to obtain, making them a promising alternative therapeutic option [22–24].

Over the past decade, the growing interest in EVs therapies has brought them to the forefront of medical research, however accompanied by challenges and unanswered questions. There exists high heterogeneity in the source of EVs (embryonic stem cell, mesenchymal stem cell, etc.), EVs isolation methods, administration routes, and treating methods, etc., all of which influence therapeutic outcomes [25, 26]. Particularly in 2023, a notable surge in studies within this the field has been observed, yet a comprehensive and up-to-dated meta-analysis is currently lacking. The diverse research landscape, with its numerous variables, requires a detailed exploration of experimental nuances. A thorough understanding the overall impact of stem cell-derived EVs on POF are essential prior to clinical translation.

In the clinical realm, rigorous meta-analysis is considered a gold standard for the objective and comprehensive evaluation of intervention efficacy. By applying systematical meta-research methods in preclinical EVs research, our study aims to assess the effectiveness of stem cell-derived EVs in treating POF across diverse literature. We conducted subgroup analyses to uncover specific EV characteristics and methodology influencing treatment outcomes, aiming to identify knowledge gaps. Notably, we utilized trial sequential analysis (TSA) to enhance control over random errors in cumulative meta-analyses, thereby assessing the reliability of current evidence. Our work aligns with the growing number of evidence from preclinical animal research, assessing the efficacy of EVs in POF and providing insights into the prospects of clinical translation.

Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines and PRISMA 2020 [27, 28]. This meta-analysis has been registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42024509699). Our study strictly adhered to the protocol without deviations, and it did not involve patients or the public.

Search strategy

Two authors (Yan Luo and Jinyao Ning) independently conducted literature searches in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and EMBASE database from inception to February 18, 2024. The search utilized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “extracellular vesicles” or “exosomes” and “premature ovarian failure”, alone with corresponding free words and Boolean operators to construct a comprehensive literature search strategy (Please refer to the Supplementary Materials for detailed search strategies).

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Studies using animal models of POF and providing detailed modeling methods to investigate the efficacy of stem cell-derived EVs therapy; (2) The treatment/experimental group receiving EVs therapy alone or in combination with adjuvants, while the control/untreated group receiving phosphate buffered saline (PBS), physiological saline, no treatment or the same adjuvant as treatment group; (3) Provided detailed methods for the extraction and identification of EVs; (4) Reporting one or more of the following results: ovary weight, pregnancy rate, birth count, follicle count, levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), estradiol (E2) or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Studies have been published repeatedly or contain duplicated or redundant data; (2) Document types including letters, case reports, reviews, conference abstracts, etc.; (3) Studies where data are not provided or cannot be obtained from the original author; (4) EVs originating from non-stem cells.

Study selection and data extraction

Two researchers (Yan Luo and Jinyao Ning) independently conducted the study selection process after the literature search. Duplicates were firstly removed, followed by a first round of screening involving browsing titles and abstracts. A second round of screening involved evaluating the full text of all eligible articles. Subsequently, two researchers (Jingjing Chen and Jinyao Ning) extracted data from the retained studies, including first author, publication year, country, animal model characteristics, disease model, EVs therapy characteristics, experimental design, and outcome evaluation indicators. In case where key research data and information were not mentioned in the paper, the corresponding author was contacted for details via email. The extracted data were then collated and checked. In instances of disagreement, a third author (Hui Li) conduct a discussion with all author together for the final decision.

Outcome evaluation indicators

The primary outcome evaluation indicators extracted in this meta-analysis include ovary weight, pregnancy rate, birth count, and follicle count, which serve as the measures of animal fertility and regenerative potential of the ovary. Secondary outcomes encompassed serum levels of AMH, E2, and FSH, which indicate ovarian reserve capacity.

Quality assessment and statistical analysis

Two authors (Jingjing Chen and Jinyao Ning) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) risk of bias tool (a 10-item risk assessment tool for preclinical studies) [29]. In cases of discrepancies, a third author (Yan Luo) participated in the discussion and collaborated on reaching a final decision. Dichotomous variables were evaluated with risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while continuous variables were presented as standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CI. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied to determine significant difference. Heterogeneity among selected studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic. Given the methodological variation across studies leading to significant heterogeneity, a random effects model was utilized [30]. Sensitivity analyses was conducted by sequentially excluding one article at a time to assess the impact on the overall effect. Egger’s test was employed to detect publication bias, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. In case where publication bias was detected and sufficient data were available, the trim-fill method developed by Duval and Tweedie was used to adjust for bias [31]. Data analysis was performed using RevMan software (Version 5.4) and Stata 14.0.

Trial sequential analysis

We employed TSA to evaluate the risk of random error and determine the conclusiveness of cumulative results in the meta-analysis [32, 33]. For continuous results, we set alpha value to 5% and the beta value to 20% (80% power), utilizing the heterogeneity correction method based on model variance. For dichotomous outcomes, a predefined relative risk reduction of 20% was applied, with alpha set to 5% and beta set to 20% (80% power). Control event rates were calculated from either the placebo or control group. TSA Viewer version 0.9 beta software was used for analysis (http://www.ctu.dk/tsa).

Bibliometric analysis

The Bibliometrics method is usually used to study the development of a field and predict future hot spots. In this study, we use the Web of Science database, which is the one that is most frequently utilized in bibliometrics, as the source of relevant literature. Please refer to Sect. " Search strategy" for specific search strategies. VOSviewers (Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands) software was used for keyword analysis and citation tracking.

Results

Study selection

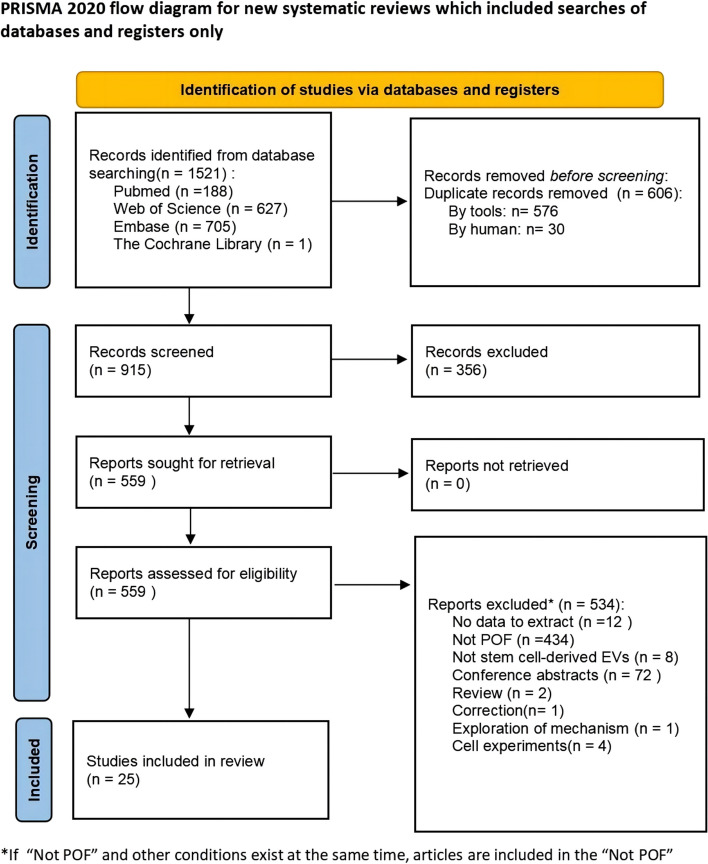

The literature search yielded a total of 1521 potentially relevant publications. Among them, 606 studies were removed due to duplication. Subsequently, 356 articles were excluded based on the initial screening. Upon examination of the full text of 534 research articles, 25 studies [22, 25, 26, 34–55] met the inclusion criteria and were finally included in this meta-analysis. The literature screening flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram. (Abbreviation: POF: premature ovarian failure)

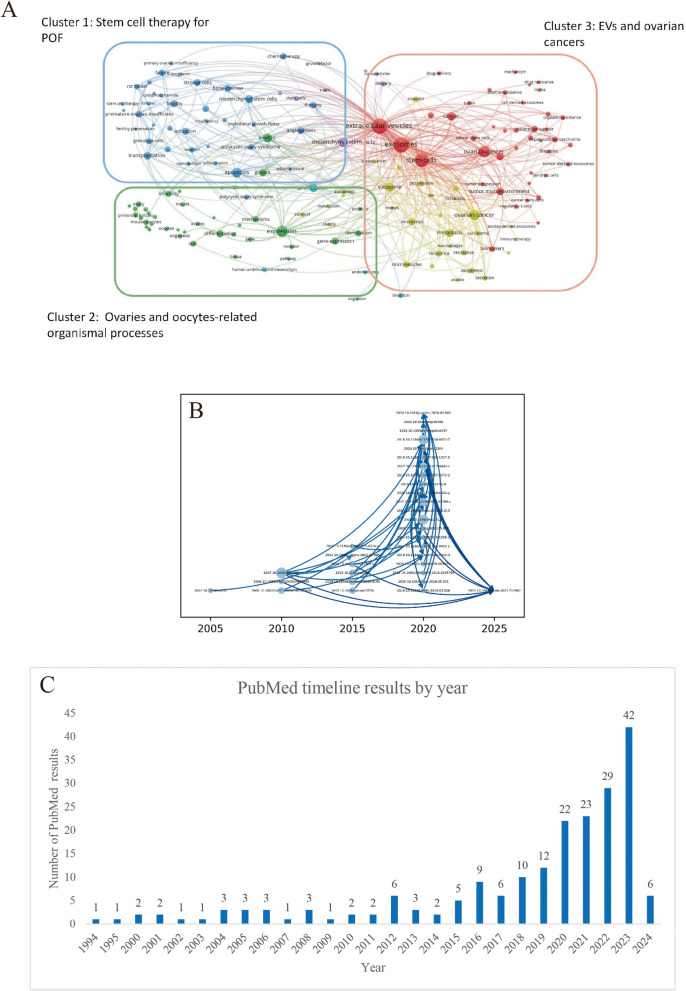

Connection between keywords

The visual mapping showed that keywords were divided into 3 clusters: “Stem cell therapy for POF”, “Ovaries and oocytes-related organismal processes”, “EVs and ovarian cancers” (Fig. 2A). Research focuses include studying the pathophysiological mechanisms of POF and exploring stem cell-based EV therapies and innovative bioengineering methods. The citation track map in Web of Science database depicts the citation between important works of the research field (Fig. 2B). This field experienced an outburst between the year 2015–2020. We also found that in the PubMed database, published documents related to EVs and POF are gradually increasing (Fig. 2C). It indicates that research in this field has developed rapidly and is in a rapid rising stage, highlighting the necessity of such meta-studies.

Fig. 2.

Bibliometric analysis. A Connection between keywords map. Cluster 1 (blue): “Stem cell therapy for POF”. Cluster 2 (green): “Ovaries and oocytes-related organismal processes”. Cluster 3 (red): “EVs and ovarian cancers”. B Citation track map. Each circle represents documents (including DOI numbers) that have been cited more than 20 times, and are defined as representative documents in the field. The larger the circle, the more times it has been cited. C Analysis of annual publishing trends in PubMed database. (Abbreviation: EVs: extracellular vesicles; POF: premature ovarian failure; DOI: digital object identifier)

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The 25 studies spanned from 2016 to 2023 (Fig. 3A), with the majority (21 trials) conducted in China [25, 26, 34–39, 41–44, 46–51, 53–55], followed by 2 trials in Iran [45, 52], one in the United States [22], and one in Egypt [40] (Fig. 3B). The total sample size across studies was 339 animals, with 173 allocated to the EVs treatment group and the remaining to the control group. Seventeen studies utilized mice as the animal model, while the remainder employed rats (Fig. 3C). Various methods were employed for disease modeling, include cyclophosphamide (CTX), CTX + busulfan (BUS), cisplatin, 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD), and D-galactose (D-gal) (Fig. 3D). The EVs utilized in the trials were derived from different stem cells sources, including umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) and adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs), etc. Despite EVs being derived from cells of different species, each study independently demonstrated their effectiveness against POF in animal models. The route of drug administration primarily involved intravenous injection, although ovary and intraperitoneal injections were also used (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

An overview of studies characteristics, including distribution of (A) publications by year (B) region (C) animal model (D) disease model (E) route of administration

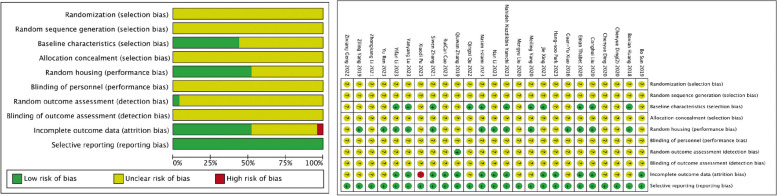

Risk of bias in the eligible studies

The included articles did not specify whether animal groups were randomly generated, nor did they provide details on randomization and allocation concealment methods, resulting in an unclear risk of selection bias (Fig. 4). While these studies did not extensively discuss blinding of personnel, it is evident that the animals were unaware of the group assignment, thus ensuring blinding of participants. Overall, the risk of reporting bias in these articles was low. Thirteen studies demonstrated a low risk of attrition bias, while one study had incomplete outcome data, resulting in a high risk of attrition bias.

Fig. 4.

Risk of bias summary

Outcomes of the meta-analysis

Ovary weight

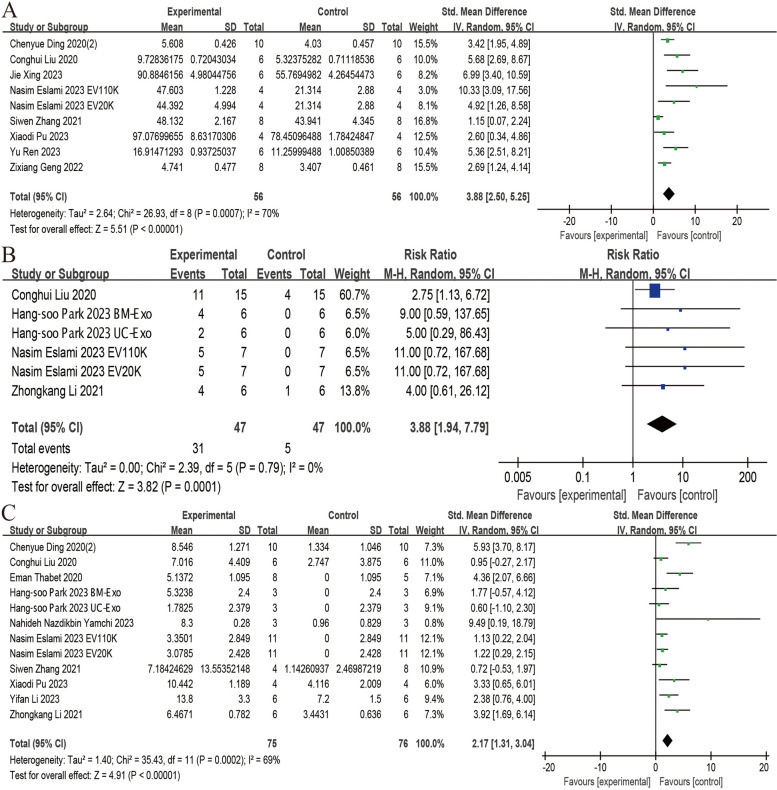

Eight studies reported the effect of stem cell-derived EVs on ovary weight [34, 38, 42, 44, 48, 51, 52, 54]. The meta-analysis revealed a significant increase in ovary weight following the administration of stem cell-derived EVs (SMD = 3.88; 95% CI: 2.50 ~ 5.25; P < 0.00001; I2 = 70%, P = 0.0007) (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots depicting the comparison between the stem cell-derived EVs and control groups: A Ovary weight; B Pregnancy rate; C Count of births. (Abbreviation: EVs: extracellular vesicles)

Pregnancy rate

Four studies, encompassing 6 trials, examined the efficacy of stem cell-derived EVs on pregnancy rate, demonstrating a significantly improvement with EV administration (RR = 3.88; 95% CI: 1.94 ~ 7.79; P = 0.0001; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 5B) [22, 48, 49, 52].

Count of births

Analysis of data from 12 trials revealed that administration of stem cell-derived EVs significantly increased the count of births in POF animals (SMD = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.31 ~ 3.04; P < 0.00001; I2 = 69%) (Fig. 5C) [22, 25, 34, 40, 44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 54].

Follicle count

The effects of stem cell-derived EVs on primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicle counts were assessed across 16, 14, 14, and 15 included trials, respectively. The results demonstrate that administration of stem cell-derived EVs significantly increased primordial follicle count (SMD = 3.75; 95% CI: 2.30 ~ 5.19; P < 0.00001; I2 = 86%), primary follicle count (SMD = 2.99; 95% CI: 1.83 ~ 4.14; P < 0.00001; I2 = 78%), secondary follicle count (SMD = 3.21; 95% CI: 2.03 ~ 4.38; P < 0.00001; I2 = 81%), antral follicle count (SMD = 3.41; 95% CI: 2.31 ~ 4.51; P < 0.00001; I2 = 81%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plots depicting the comparison between the stem cell-derived EVs and control groups: A Primordial follicle count; B Primary follicle count; C Secondary follicle count; D Antral follicle count. (Abbreviation: EVs: extracellular vesicles)

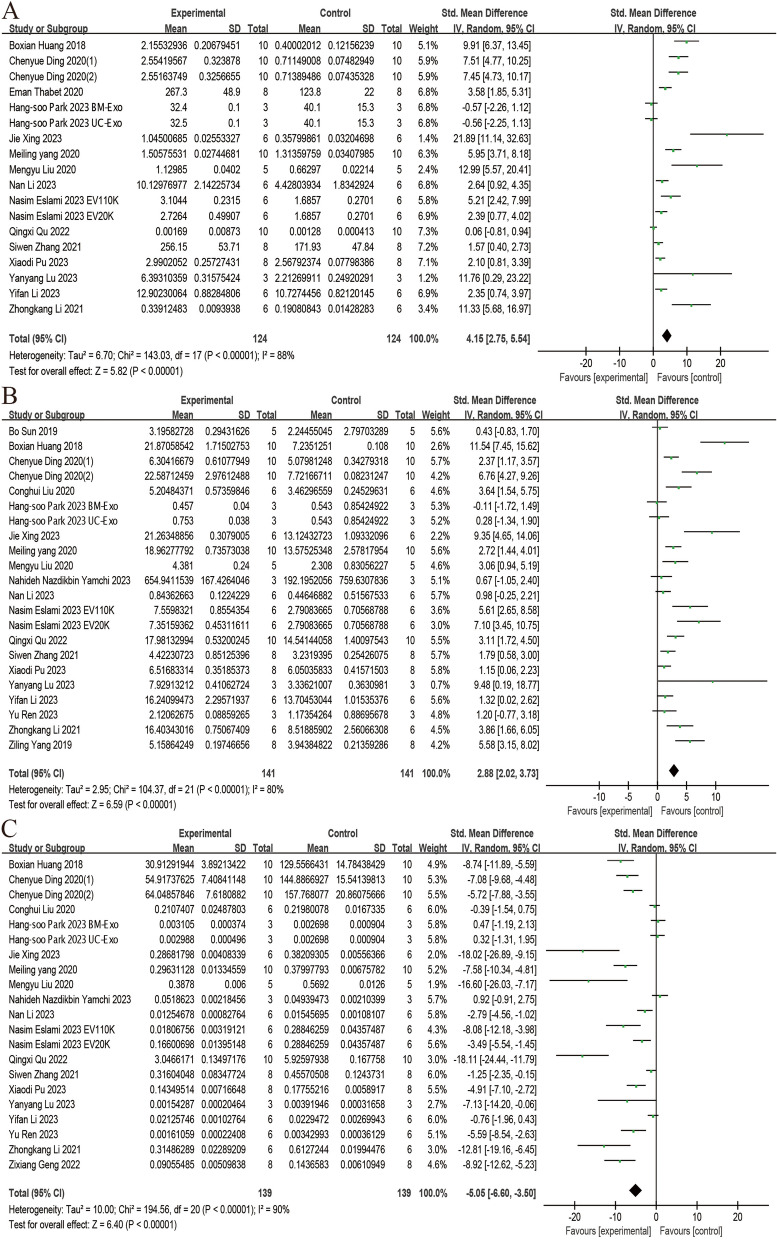

The serum levels of FSH, E2 and AMH

We analyzed data from 18, 22 and 21 trials, respectively, to evaluate the effect of stem cell-derived EVs on the serum level of AMH, E2, and FSH. All studies employed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection. The analysis showed that administration of stem cell-derived EVs significantly increased the level of AMH (SMD = 4.15; 95% CI: 2.75 ~ 5.54; P < 0.00001; I2 = 88%) and E2 (SMD = 2.88; 95% CI: 2.02 ~ 3.73; P < 0.00001; I2 = 80%), while reducing the level of FSH (SMD = -5.05; 95% CI: -6.60 ~ -3.50; P < 0.00001; I2 = 90%) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Forest plots depicting the comparison between the stem cell-derived EVs and control groups: A AMH; B E2; C FSH. (Abbreviation: EVs: extracellular vesicles; AMH: anti-Müllerian hormone; E2: estradiol; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone)

Subgroup analysis results

The efficacy of EVs and heterogeneity in meta-analysis may be influenced by various factors including the source of EVs, animal species, disease model, EVs administration route, and test timepoint. Therefore, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses on the primary outcome indicators based on these conditions (Supplementary Table 2).

Based on the source of EVs, the main subgroups included UC-MSCs, clonal mesenchymal stromal cells (cMSCs), BMSCs, amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells (AFSCs), ADSCs. UC-MSCs, and cMSCs were found to significantly increase ovary weight, count of births and pregnancy rate. Additionally, UC-MSCs demonstrated an increase in the follicle count. However, the effects of BMSCs, cMSCs, and AFSCs on different types of follicles showed unstable statistical differences.

The animal species utilized in the study comprised mice and rats. Subgroup analyses indicated statistical differences in all outcome indicators, except for the rat subgroups of primordial follicles and antral follicles, which showed no statistical difference (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the heterogeneity was reduced in these analyses.

The disease models of POF primarily involved CTX and CTX + BUS. Subgroup analyses based on disease models showed statistical differences in all outcome indicators. However, heterogeneity was not consistently reduced across the analyses.

The main methods of EVs administration route include ovary injection, tail vein injection, and intraperitoneal injection. The results of subgroup analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference between ovarian injection + tail vein injection on primary follicle and antral follicle count, and there was also no statistical difference on the effect of tail vein injection on primary follicle count. Additionally, the EVs administration route showed statistical differences in increasing ovary weight and count of births, accompanied by reduced heterogeneity.

The follow-up period and testing timepoint, mainly ranging from 1 day to 12 weeks after the last transplantation, was analyzed in subgroup analyses. Results indicated that when the test timepoint was 1 day, subgroup analysis outcomes were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), whereas significant statistical differences were observed for the remaining timepoints.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Table 1 summarizes the sensitivity analysis and publication bias of this meta-analysis. Each study was individually excluded to assess its impact on the final effect, with results remaining consistent with those of all included studies, indicating the stability and reliability (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, in Egger’s test, only primary follicle count did not exhibit publication bias (p > 0.05). Subsequent trim and fill method analysis showed that ovary weight, count of births, primary follicle count, secondary follicle count, level of FSH were not trimmed, and the data in the funnel plot remained unchanged, suggesting no significant publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 2–4). Pregnancy rate, antral follicle count, level of AMH and E2 were trimmed using the trim and fill method (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Sensitivity and publication bias analysis

| Outcome | SMD/RR fluctuation | 95% CI fluctuation | Publication bias (P value) | Pooling model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovary weight | 4.02–4.80 | 2.52–3.40 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Pregnancy rate | 3.61–6.62 | 1.76–20.11 | 0.008 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Count of births | 2.10–2.72 | 1.24–3.84 | 0.005 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Primordial follicle count | 3.84–4.51 | 2.33–6.06 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Primary follicle count | 2.90–3.62 | 1.69–4.71 | 0.232 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Secondary follicle count | 3.16–3.88 | 1.99–5.25 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| Antral follicle count | 3.48–4.03 | 2.35–5.26 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| AMH | 4.21–4.99 | 2.75–6.61 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| FSH | (-5.98) -(-5.04) | (-7.79) -(-3.45) | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

| E2 | 2.86–3.36 | 2.09–4.31 | 0.000 | Random (I-V heterogeneity) |

Abbreviations: FSH Follicle-stimulating hormone, E2 Estradiol, AMH Anti-Mullerian hormone, RR Risk ratio, SMD Standardized mean difference

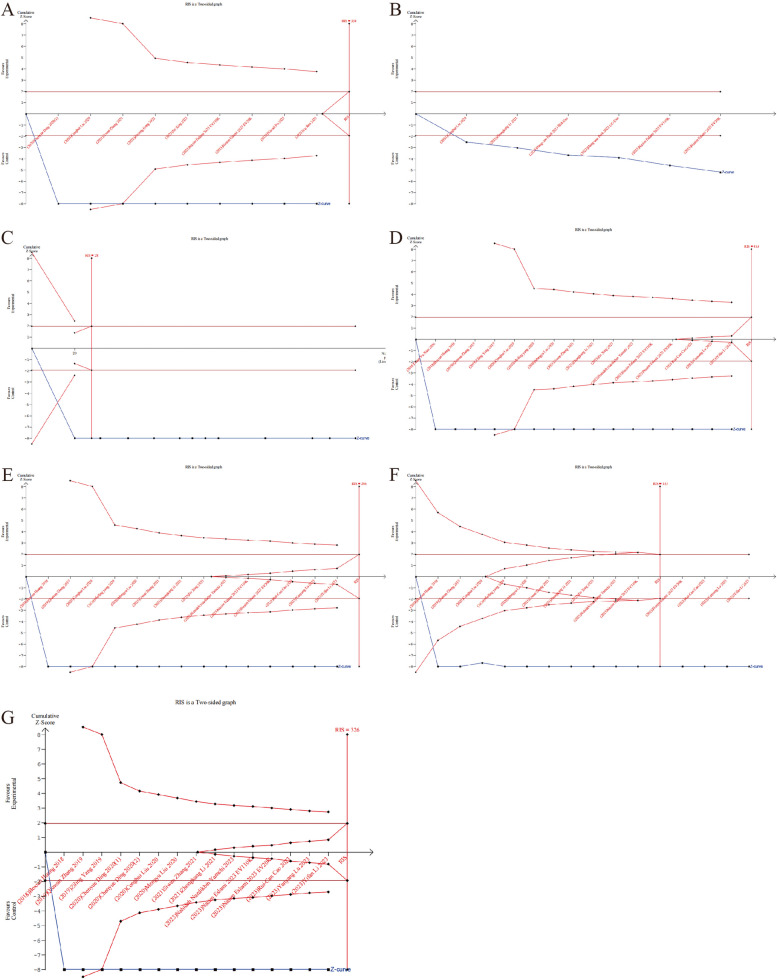

Trial sequential analysis

TSA can assess whether results are supported by sufficient data. The TSA results indicate that there is enough data to draw definite conclusions about the count of births, ovary weight, as well as primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicle counts. However, regarding pregnancy rate, the evidence is inconclusive according to TSA. This uncertainty may result in false negative or false positive conclusions due to the small number of experimental animals. Therefore, more animal experiments are warranted in the future to further validate these findings (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Trial sequential analysis results depicting the comparison between the stem cell-derived EVs and control groups. A Ovary weight. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional line, but did not reach the RIS. B Pregnancy rate. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional line, but did not reach the RIS. C Count of births. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional and reached the RIS. D Primordial follicle count. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional, but did not reach the RIS. E Primary follicle count. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional, but did not reach the RIS. F Secondary follicle count. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional and reached the RIS. G Antral follicle count. The cumulative Z curve crossed the conventional, but did not reach the RIS. (Abbreviation: EVs: extracellular vesicles; RIS, required information size)

Safety of stem cell-derived EVs

In the 25 studies included, the safety of EVs is mentioned in 6 of them [22, 34, 40, 48, 50, 55]. Two studies explicitly mention experiments on the safety of EVs, reporting safety outcomes, and indicating that none of the participants treated with EVs during the study period experienced EVs-related adverse events or complications [22, 48]. In the other 4 studies, EVs are generally accepted as safe [34, 40, 50, 55]. The incidence of serious adverse drug reactions was not recorded or reported.

Discussion

Principal findings

This meta-analysis comprised 25 studies involving a total of 368 experimental animals. The analysis demonstrates that administration of EVs can improve the ovary function of POF rat/mouse model. Specifically, it increases ovary weight, pregnancy rate, count of births, and follicle count. In addition, it elevates the serum level of AMH and E2 while reducing the expression of FSH. The source of EVs, animal species, disease model, EVs administration route and test timepoint are identified as important factors influencing the efficacy of EVs in POF.

As stem cell-derived EVs are increasingly recognized for their therapeutic potential in treating POF, their intricate mechanism of action, demonstrated in preclinical mouse models, involves attenuating fibrotic changes [45], reducing oxidative injury and apoptosis in granulosa cells [38, 46], inhibiting autophagy [42], and promoting angiogenesis [43]. The actions effectively prevent follicular atresia and normalize sex-related hormones, contributing to the restoration of ovarian function. The identified effects are mediated through the activation of specific pathways, including PI3K/Akt pathway [26], TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway [50], Hippo pathway [49] and AMPK/mTOR pathway [42]. Additionally, key miRNAs have been identified as playing crucial roles in the above processes. Both miRNA-145-5p [46], carried by hUC-MSC-EVs, and miR-369-3p [52], carried by AFSC-EVs, specifically attenuated GC apoptosis, while knockdown these miRNAs partly abolished the therapeutic effects. Furthermore, transfection of parental stem cells with specific miRNA mimics/inhibitors effectively regulated the expression in cell-derived EVs. Delivery of circLRRC8A-enriched exosomes [38] and miR-144-5p [37] overexpressed in BMSCs-EVs enhanced efficacy in protecting cellular senescence and POF. These findings demonstrate modified EVs as effective carriers and pave the way for establishing of a cell-free therapeutic approach for POF.

Comparison with existing literature

Instead of performing a meta-analysis, Liao et al. [56] conducted a review focusing on the therapeutic role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs (MSC-EVs) in female reproductive diseases, such as intrauterine adhesions (IUA), POF, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). They highlighted various therapeutic effects, include repairing damaged endometrium, inhibiting endometrial fibrosis, regulating immune response, and resisting inflammation, as well as inhibiting apoptosis of granulosa cells in the ovary. Additionally, they summarized the potential mechanism of action. On the other hand, Zhou et al. [57] performed a meta-analysis specifically exploring the impact of MSC-EVs in the animal model of female reproductive diseases (IUA, POF, PCOS). Their analysis, involving 15 studies, demonstrated that treatment with MSC-EVs significantly improved AMH at 2 and 4 weeks compared with control. Subgroup analysis indicated that factors such as animal type, modeling method, MSC source, EVs isolation method, number of injections, route of administration, and outcome measurement unit did not contribute to heterogeneity. It is worth noticing that our meta-analysis centered on the effect of whole stem cell-derived EVs on POF, encompassing not only MSC-EVs but also other sources of EVs. We conducted detailed subgroup analyses on factors such as animal types, modeling methods, stem cell sources, administration routes, etc. Additionally, we employed sensitivity analysis, assessed publication bias and conducted TSA to evaluate the stability and reliability of the results.

Strengths of this meta-analysis

(1) We conducted a comprehensive and systematic literature search, rigorous screening and data extraction, ultimately including 25 animal studies, with the majority published within the past two years (12 of 25). This resulted in relatively abundant number of documents, with most publications being recent. (2) Detailed subgroup analyses were performed to explore the heterogeneous sources and role factors of EVs in POF animal models. Factors examined included the source of EVs, animal species, disease model, EVs administration route and test timepoint, etc. (3) Various methods, including sensitivity analysis, egger’s test, SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool, and TSA, were employed to assess the quality and accuracy of the results, enhancing the credibility and convincingness of our finding.

Limitations

(1) Although we included a lot of literature, the overall quality of the included literature was deemed low due to numerous risks of bias being unclear, and the presence of some publication. (2) The data of our meta-analysis is derived from animal experiments, primarily utilizing mice and rats as experimental subjects. It’s important to acknowledge that there are inherent differences between animal models and humans, which may impact the translation of findings to clinical practice. (3) The number of animals in the included studies was relatively small, and there was considerable variation in experimental protocols, including the source of EVs, EVs injection dose, number of injections, EVs isolation methods, etc. Consequently, we were unable to determine an optimal EVs treatment option. (4) Due to differences in EVs composition between human-derived and animal-derived stem cells, as well as species differences, there may be some differences in therapeutic efficacy which require more experimental research to prove in the future.

Implications for clinical practice and research

Collectively, our study rigorously evaluated the evidence and scrutinized the risks associated with the current studies, providing a solid foundation for future research and subsequent clinical translation. However, because existing studies provide limited data on fertility status (such as pregnancy rates, number of births, etc.), the results of the analysis are therefore limited. Future studies would benefit from providing comprehensive data on pregnancy status, hormone levels, and follicle counts to better evaluate the efficacy of EVs in POF. While there are unresolved issues that necessitate further investigation, stem cell-derived EVs holds significant promise as a cell-free therapeutic approach capable of enhancing ovarian function and fertility. Continued research in this area has the potential to significantly impact clinical practice and improve outcomes for patients with POF.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis compared the efficacy of stem cell-derived EVs in POF animal models using indicators such as pregnancy rate, ovary weight, count of births, counts of different types of follicles, serum level of AMH, E2, FSH. The overall results indicate that stem cell-derived EVs therapy has beneficial effects in the treatment of POF animal models. However, the potential use of stem cell-derived EVs to treat human POF remains to be explored in larger, more biologically relevant animal models or clinical trials.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Reproductive Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. We would like to thank the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation, and the Xiangya Hospital Foundation for their support.

Abbreviations

- POF

Premature ovarian failure

- POI

Premature ovarian insufficiency

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy

- EVs

Extracellular vesicles

- TSA

Trial sequential analysis

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- AMH

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- E2

Estradiol

- FSH

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- SYRCLE

Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory animal Experimentation

- RR

Risk ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- SMDs

Standardized mean differences

- CTX

Cyclophosphamide

- BUS

Busulfan

- VCD

4-Vinylcyclohexene diepoxide

- D-gal

D-galactose

- UC-MSCs

Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

- BMSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ADSCs

Adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- cMSCs

Clonal mesenchymal stromal cells

- AFSCs

Amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells

- MSC-EVs

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs

- IUA

Intrauterine adhesions

- PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Authors’ contributions

YL: Conceptualization, project administration, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing- review and editing. JC: Conceptualization, project administration, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing- review and editing. JN: Supervision, methodology, resources, writing—review and editing. YS: Methodology, formal analysis, software, writing—review and editing. YC: Supervision, resources, methodology, software, writing—review and editing. FX: Data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. BH: Data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. GL: Data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. FT: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. JH: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. HS: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. QZ: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. JZ: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. YLi: Supervision, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. HL: Conceptualization, financial acquisition, data curation, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Funding

This project was supported by the Science Foundation For Excellent Young Scholars of Hunan Province, China (No. 2024JJ4091); Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82301835); Science Foundation for Young Scholars of Hunan Province, China (No. 2023JJ40956); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation(General Program) (No. 2022M713522); China Postdoctoral Foundation (No. 2021TQ0372); Young Investigator Grant of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (No.2021Q03); National Natural Science Foundation of China(General Program) (No. 82371682); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (1053320222496).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yan Luo and Jingjing Chen contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, Cartwright B, et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):926–37. 10.1093/humrep/dew027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golezar S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Khazaei S, Ebadi A, Keshavarz Z. The global prevalence of primary ovarian insufficiency and early menopause: a meta-analysis. Climacteric. 2019;22(4):403–11. 10.1080/13697137.2019.1574738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulam CB, Adamson SC, Annegers JF. Incidence of premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(4):604–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jankowska K. Premature ovarian failure. Prz Menopauzalny. 2017;16(2):51–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shareghi-Oskoue O, Aghebati-Maleki L, Yousefi M. Transplantation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to treat premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):454. 10.1186/s13287-021-02529-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachelot A, Rouxel A, Massin N, Dulon J, Courtillot C, Matuchansky C, et al. Phenotyping and genetic studies of 357 consecutive patients presenting with premature ovarian failure. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(1):179–87. 10.1530/EJE-09-0231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bussani C, Papi L, Sestini R, Baldinotti F, Bucciantini S, Bruni V, Scarselli G. Premature ovarian failure and fragile X premutation: a study on 45 women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;112(2):189–91. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forges T, Monnier-Barbarino P, Faure GC, Béné MC. Autoimmunity and antigenic targets in ovarian pathology. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(2):163–75. 10.1093/humupd/dmh014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novosad JA, Kalantaridou SN, Tong ZB, Nelson LM. Ovarian antibodies as detected by indirect immunofluorescence are unreliable in the diagnosis of autoimmune premature ovarian failure: a controlled evaluation. BMC Womens Health. 2003;3(1): 2. 10.1186/1472-6874-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sukumvanich P, Case LD, Van Zee K, Singletary SE, Paskett ED, Petrek JA, et al. Incidence and time course of bleeding after long-term amenorrhea after breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. Cancer. 2010;116(13):3102–11. 10.1002/cncr.25106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spears N, Lopes F, Stefansdottir A, Rossi V, De Felici M, Anderson RA, Klinger FG. Ovarian damage from chemotherapy and current approaches to its protection. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25(6):673–93. 10.1093/humupd/dmz027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webber L, Anderson RA, Davies M, Janse F, Vermeulen N. HRT for women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a comprehensive review. Hum Reprod Open. 2017;2017(2):hox007. 10.1093/hropen/hox007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Mei Q, Xie Q, Li H, Su P, Zhang L, et al. A comparative study of Mesenchymal Stem Cells transplantation approach to antagonize age-associated ovarian hypofunction with consideration of safety and efficiency. J Adv Res. 2022;38:245–59. 10.1016/j.jare.2021.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Sun Y, Zhang XX, Liu YB, Sun HY, Wu CT, et al. Comparison of CD146 +/- mesenchymal stem cells in improving premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):267. 10.1186/s13287-022-02916-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng X, Ling L, Zhang W, Liu X, Wang Y, Luo Y, Xiong Z. Effects of human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cell (hAD-MSC) transplantation in situ on primary ovarian insufficiency in SD rats. Reprod Sci. 2020;27(7):1502–12. 10.1007/s43032-020-00147-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling L, Feng X, Wei T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, et al. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS)-pretreated human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cell (hAD-MSC) transplantation on primary ovarian insufficiency in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):283. 10.1186/s13287-017-0739-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling L, Feng X, Wei T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang Z, et al. Human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cell (hAD-MSC) transplantation improves ovarian function in rats with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) at least partly through a paracrine mechanism. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):46. 10.1186/s13287-019-1136-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshtkar S, Azarpira N, Ghahremani MH. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):63. 10.1186/s13287-018-0791-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Wang Y, Yang T, Li J, Yang X. Study of the reparative effects of menstrual-derived stem cells on premature ovarian failure in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):11. 10.1186/s13287-016-0458-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batrakova EV, Kim MS. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2015;219:396–405. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Pinilla-Macua I, Ouyang Y, Sadovsky E, Kajiwara K, Sorkin A, Sadovsky Y. Internalization of trophoblastic small extracellular vesicles and detection of their miRNA cargo in P-bodies. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1812261. 10.1080/20013078.2020.1812261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park HS, Chugh RM, Seok J, Cetin E, Mohammed H, Siblini H, et al. Comparison of the therapeutic effects between stem cells and exosomes in primary ovarian insufficiency: as promising as cells but different persistency and dosage. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):165. 10.1186/s13287-023-03397-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rani S, Ryan AE, Griffin MD, Ritter T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: toward cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 2015;23(5):812–23. 10.1038/mt.2015.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teixeira FG, Carvalho MM, Sousa N, Salgado AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: a new paradigm for central nervous system regeneration? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(20):3871–82. 10.1007/s00018-013-1290-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Zhang H, Cai C, Mao J, Li N, Huang D, et al. Microfluidic encapsulation of exosomes derived from lipopolysaccharide-treated mesenchymal stem cells in hyaluronic acid methacryloyl to restore ovarian function in mice. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;13:e2303068. 10.1002/adhm.202303068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Fan X, Liu L, Liu Y. Therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles on ovarian functions through the PI3K/Akt cascade in mice with premature ovarian failure. Eur J Histochem. 2023;67(3):3506. 10.4081/ejh.2023.3506. 10.4081/ejh.2023.3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:43. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naaktgeboren CA, van Enst WA, Ochodo EA, de Groot JA, Hooft L, Leeflang MM, et al. Systematic overview finds variation in approaches to investigating and reporting on sources of heterogeneity in systematic reviews of diagnostic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(11):1200–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wetterslev J, Jakobsen JC, Gluud C. Trial Sequential Analysis in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):39. 10.1186/s12874-017-0315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Y, Sun Y, Huang B, Chen J, Xu B, Li H. Effects and safety of hyaluronic acid gel on intrauterine adhesion and fertility after intrauterine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;231:36–50. 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S, Huang B, Su P, Chang Q, Li P, Song A, et al. Concentrated exosomes from menstrual blood-derived stromal cells improves ovarian activity in a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):178. 10.1186/s13287-021-02255-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q, Sun J, Huang Y, Bu S, Guo Y, Gu T, et al. Human amniotic epithelial cell-derived exosomes restore ovarian function by transferring MicroRNAs against apoptosis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;16:407–18. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Z, Du X, Wang C, Zhang J, Liu C, Li Y, Jiang H. Therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles on premature ovarian insufficiency in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):250. 10.1186/s13287-019-1327-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang M, Lin L, Sha C, Li T, Zhao D, Wei H, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-144-5p improves rat ovarian function after chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure by targeting PTEN. Lab Invest. 2020;100(3):342–52. 10.1038/s41374-019-0321-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing J, Zhang M, Zhao S, Lu M, Lin L, Chen L, et al. EIF4A3-induced exosomal circLRRC8A alleviates granulosa cells senescence via the miR-125a-3p/NFE2L1 axis. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2023;19(6):1994–2012. 10.1007/s12015-023-10564-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao GY, Cheng CC, Chiang YS, Cheng WT, Liu IH, Wu SC. Exosomal miR-10a derived from amniotic fluid stem cells preserves ovarian follicles after chemotherapy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23120. 10.1038/srep23120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thabet E, Yusuf A, Abdelmonsif DA, Nabil I, Mourad G, Mehanna RA. Extracellular vesicles miRNA-21: a potential therapeutic tool in premature ovarian dysfunction. Mol Hum Reprod. 2020;26(12):906–19. 10.1093/molehr/gaaa068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun B, Ma Y, Wang F, Hu L, Sun Y. miR-644-5p carried by bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes targets regulation of p53 to inhibit ovarian granulosa cell apoptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):360. 10.1186/s13287-019-1442-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren Y, He J, Wang X, Liang H, Ma Y. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells alleviate premature ovarian failure via blockage of autophagy and AMPK/mTOR pathway. PeerJ. 2023;11: e16517. 10.7717/peerj.16517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu Q, Liu L, Cui Y, Liu H, Yi J, Bing W, et al. miR-126-3p containing exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenesis and attenuate ovarian granulosa cell apoptosis in a preclinical rat model of premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):352. 10.1186/s13287-022-03056-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pu X, Zhang L, Zhang P, Xu Y, Wang J, Zhao X, et al. Human UC-MSC-derived exosomes facilitate ovarian renovation in rats with chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian insufficiency. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1205901. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1205901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nazdikbin Yamchi N, Ahmadian S, Mobarak H, Amjadi F, Beheshti R, Tamadon A, et al. Amniotic fluid-derived exosomes attenuated fibrotic changes in POI rats through modulation of the TGF-beta/Smads signaling pathway. J Ovarian Res. 2023;16(1):118. 10.1186/s13048-023-01214-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Y, Wei Y, Shen X, Tong Y, Lu J, Zhang Y, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles improve ovarian function in rats with primary ovarian insufficiency by carrying miR-145-5p. J Reprod Immunol. 2023;158: 103971. 10.1016/j.jri.2023.103971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Qiu Y, Xue Z, Wu R, Li J, Niu X, et al. Small extracellular vesicles derived from embryonic stem cells restore ovarian function of premature ovarian failure through PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):3. 10.1186/s13287-019-1508-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Yin H, Jiang H, Du X, Wang C, Liu Y, et al. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Recover Fertility of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency Mice and the Effects on their Offspring. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720923575. 10.1177/0963689720923575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Z, Zhang M, Zheng J, Tian Y, Zhang H, Tan Y, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes improve ovarian function and proliferation of premature ovarian insufficiency by regulating the hippo signaling pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 711902. 10.3389/fendo.2021.711902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang B, Lu J, Ding C, Zou Q, Wang W, Li H. Exosomes derived from human adipose mesenchymal stem cells improve ovary function of premature ovarian insufficiency by targeting SMAD. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):216. 10.1186/s13287-018-0953-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geng Z, Chen H, Zou G, Yuan L, Liu P, Li B, et al. Human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes inhibit apoptosis in ovarian granulosa cell via miR-369-3p/YAF2/PDCD5/p53 Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3695848. 10.1155/2022/3695848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eslami N, Bahrehbar K, Esfandiari F, Shekari F, Hassani SN, Nazari A, et al. Regenerative potential of different extracellular vesicle subpopulations derived from clonal mesenchymal stem cells in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian failure. Life Sci. 2023;321: 121536. 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao RC, Lv Y, Lu G, Liu HB, Wang W, Tan C, et al. Extracellular vesicles from iPSC-MSCs alleviate chemotherapy-induced mouse ovarian damage via the ILK-PI3K/AKT pathway. Zool Res. 2023;44(3):620–35. 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2022.340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding C, Qian C, Hou S, Lu J, Zou Q, Li H, Huang B. Exosomal miRNA-320a Is Released from hAMSCs and Regulates SIRT4 to prevent reactive oxygen species generation in POI. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;21:37–50. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding C, Zhu L, Shen H, Lu J, Zou Q, Huang C, et al. Exosomal miRNA-17-5p derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improves ovarian function in premature ovarian insufficiency by regulating SIRT7. Stem Cells. 2020;38(9):1137–48. 10.1002/stem.3204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liao Z, Liu C, Wang L, Sui C, Zhang H. Therapeutic role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in female reproductive diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 665645. 10.3389/fendo.2021.665645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Y, Li Q, You S, Jiang H, Jiang L, He F, Hu L. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the animal model of female reproductive diseases: a meta-analysis. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2023;19(7):2299–310. 10.1007/s12015-023-10576-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.