Abstract

Oleate hydratase (OhyA) is a bacterial peripheral membrane protein that catalyzes FAD-dependent water addition to membrane bilayer-embedded unsaturated fatty acids. The opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus aureus uses OhyA to counteract the innate immune system and support colonization. Many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in the microbiome also encode OhyA. OhyA is a dimeric flavoenzyme whose carboxy terminus is identified as the membrane binding domain; however, understanding how OhyA binds to cellular membranes is not complete until the membrane-bound structure has been elucidated. All available OhyA structures depict the solution state of the protein outside its functional environment. Here, we employ liposomes to solve the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the functional unit: the OhyA•membrane complex. The protein maintains its structure upon membrane binding and slightly alters the curvature of the liposome surface. OhyA preferentially associates with 20–30 nm liposomes with multiple copies of OhyA dimers assembling on the liposome surface resulting in the formation of higher-order oligomers. Dimer assembly is cooperative and extends along a formed ridge of the liposome. We also solved an OhyA dimer of dimers structure that recapitulates the intermolecular interactions that stabilize the dimer assembly on the membrane bilayer as well as the crystal contacts in the lattice of the OhyA crystal structure. Our work enables visualization of the molecular trajectory of membrane binding for this important interfacial enzyme.

Keywords: oleate hydratase (OhyA), phospholipid, membrane, lipid-protein interaction, liposome, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria encode oleate hydratase (OhyA) to catalyze the hydration of 9-cis double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids to produce hydroxylated fatty acids using flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor (Radka et al., 2021b). The OhyA reaction is a key step in the symbiotic metabolism of dietary fatty acids (Yang et al., 2017a) and cell culture experiments have shown OhyA products blunt immune cell cytokine production in response to toll-like receptor activation (Ikeguchi et al., 2018; Miyamoto et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017b). OhyA is a key virulence factor that promotes colonization of the opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus aureus in the skin (Radka et al., 2021a; Subramanian et al., 2019) and in the heart (Malachowa et al., 2011), demonstrating the importance of OhyA in the host–microbe relationship.

Recent progress on elucidating the OhyA molecular mechanism has provided a structural basis for the mechanism of action. OhyAs are soluble enzymes (generally dimers) that must access the inner leaflet of the cell membrane to acquire their substrate. OhyA protomers consist of bilobed structures, comprising fatty acid and FAD lobes, along with a carboxy terminus lipid binding domain (CTD). This CTD contains amphipathic helices, structural elements renowned for stabilizing membrane binding in soluble proteins (Fig. 1) (Cornell et al., 1995; Falzone and MacKinnon, 2023; Kalmar et al., 1990; Peter et al., 2004; Richnau et al., 2004; Takei et al., 1999; Wang and Kent, 1995). X-ray crystallography on OhyA–substrate/product complexes showed OhyA uses the enzymatic mechanism of substrate-assisted acid-catalyzed water addition for catalysis (Radka et al., 2021b). A biophysical hybrid methods study using super resolution microscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance, surface plasmon resonance, and molecular dynamics showed OhyA is an interfacial enzyme that uses its carboxy terminus to directly interact with the membrane bilayer and acquire substrate (Radka et al., 2024). These studies identified amphipathic helix α−19 in the carboxy terminus as a key binding site for membrane interaction and predicted the OhyA crystal structure does not reflect the membrane-bound conformation. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) reconstruction of the OhyA solution structure superimposes with the crystal structure (Radka et al., 2024), which is consistent with the crystal structure depicting the solution state. The membrane bilayer is typically viewed as an allosteric effector causing subtle or large conformational changes that induce interfacial enzymes to achieve an additional functionally important structural level (Tatulian, 2017). The focus of this study is to find the next structural level of OhyA.

Figure 1. Stabilization of the OhyA dimer.

A, The OhyA protomer contains three functional domains: fatty acid lobe (green), FAD lobe (yellow), and membrane binding domain (blue). OhyA forms a dimer (opposite protomer shown in gray) with a 2-fold noncrystallographic symmetry axis P. The OhyA dimer interface is made up of interacting helices α1, α3, and α4. B–C, The amino acids that are predicted to engage in the highest affinity interactions (KD ≤ 10−4 M) that stabilize the OhyA dimer are in (B) the interface between the membrane binding domain and the fatty acid lobe and (C) the FAD lobe that contains the dimer interface. Zoomed-in views show the high affinity interactions consist of salt bridges and hydrogen bonds (black dashed lines), and π-stacking interactions (green dashed lines).

Liposomes are artificial lipid-based bilayered vesicles that mimic the native membranes of biological cells (Sforzi et al., 2020). Liposomes are useful bioassay reagents and drug delivery vehicles because of their biocompatibility with physiological systems (Ambati et al., 2019; Bulbake et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2004; Feng et al., 2019; Sercombe et al., 2015), and commonly used to investigate protein interaction with a phospholipidic membrane (Besenicar et al., 2006). Liposomes are convenient tools for reconstituting membrane proteins for biochemical experiments and cryo-EM reconstructions of varying resolution of integral membrane protein in liposomes (Yao et al., 2020) or soluble proteins associated with liposomes (Falzone and MacKinnon, 2023; Leung et al., 2014; Lukoyanova et al., 2015; Pang et al., 2019; Sengupta et al., 2021). We used liposomes to obtain the molecular structure of the peripheral assembly of OhyA dimers on the membrane bilayer. Cryo-EM reconstructions of the OhyA dimer of dimers and an OhyA•membrane complex provide structural insight into the molecular assembly of an interfacial enzyme on the membrane surface. These structures provide the framework to understand the cooperativity and increasing complexity of intermolecular interactions that stabilize the transition from a dimer to a polymer of dimers on the membrane surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM)

OhyA-bound liposome preparation

A 1:1 mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-glycerol (POPG):1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipids were dissolved in chloroform and dried under N2. The lipids were dissolved in pentane and dried again. The lipids were further dried under vacuum for 3 h, resuspended in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl to a concentration of 18 mg/ml (23.5 mM) lipids, and then sonicated in a water bath to clarity. Sodium cholate was added to 40 mM and the mixture was sonicated again briefly. The sample was incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. Detergent was removed using four exchanges of 200 mg/ml Bio-Beads for 3 h, 3 h, 16 h, and 3 h at 4 °C. OhyA was then added to the liposomes at a protein-to-lipid ratio of 1:4 (wt/wt) with a final lipid concentration of 11.5 mg/ml (15 mM) and a final OhyA concentration of 2.9 mg/ml (20.8 μM assuming dimers). OhyA-bound liposomes were then used to prepare grids.

Cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Grid preparation

OhyA was purified using Ni2+ affinity and gel filtration chromatography as described previously (Radka et al., 2024). The gel filtration buffer contained 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, and 150 mM KCl. Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG) detergent was added at 1 mM to 3 mg/ml OhyA before grid preparation. The samples were applied to freshly glow discharged UltrAufoil R 1.2/1.3 300 mesh grids before freezing in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI). 3.5 μl of the sample was applied to the grids and blotted for 3 s while exposed to 100% humidity at 10 °C.

For the OhyA-bound liposome reconstruction, the sample was applied to freshly glow discharged UltrAufoil R 0.6/1.0 300 mesh grids before freezing. 3.5 μl of the sample was applied to the grids prior to a 20 s wait time and blotted using a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) for 3 s while exposed to 100% humidity at 12 °C.

Data collection

For the dimer of dimers and the OhyA bound liposome reconstructions, cryo-EM data were collected using a Talos Arctica electron microscope (FEI) operated at 200 kV with a K3 direct electron detector (Gatan) operated in super-resolution mode at a magnification of 79,000 (0.522 Å/pixel). Data acquisition was automated through EPU (ThermoFisher Scientific). The electron dose rates were 50 and 54 e−/pixel/sec, respectively, divided into 50 subframes.

Data processing

All data processing, refinements, and volume modifications were done in cryoSPARC version 3 (Punjani et al., 2017). Movies were binned by two for a pixel size of 1.044 Å/pixel before patch motion correction. Patch contrast transfer functions (CTF) were estimated for each summed micrograph. These micrographs were manually curated for ice quality, CTF fit, and severity of in-frame motion. Templates low pass filtered to 20 Å were prepared from a generated model map at 1.044 Å/pix from 25 differently oriented projections generated from a model map of a previously reported dimeric crystal structure of OhyA (PDB ID: 7KAV) (Radka et al., 2021b).

For the dimer of dimers reconstruction, 372,852 particles were initially picked from 276 micrographs (Fig. S1) using template picking. After two rounds of 2D classification, in which only junk particles were discarded, the selected classes accounted for 226,781 particles. Four ab initio classes were generated from the selected 2D classified particles. Hetero refinement with these ab initio maps, yielded four classes comprised of a dimer of dimers class, two dimer classes, and a fourth junk class. Particles from the dimer of dimers class were aligned using non-uniform refinement with C2 symmetry applied. The remaining particles corresponding to the dimer classes were not used since a dimer reconstruction from a larger dataset obtained from an OhyA sample in 50 μM LMNG had been characterized (PDB ID: 8UR3) (Radka et al., 2024). A mask around the reconstruction padded by 6 Å was used in subsequent CTF refinement and local refinement resulting in a final reconstruction resolution of 2.97 Å.

For the OhyA-bound liposome reconstruction, a total of 15,784 micrographs were used (Fig. S2). Templates low pass filtered to 20 Å were prepared from a generated model map at 1.044 Å/pix from 25 differently oriented projections of the previously reported dimeric cryo-EM reconstruction of OhyA (PDB ID: 8UR3) (Radka et al., 2024). OhyA particles were picked comprising OhyA-bound liposomes, multimer OhyA ring structures in the absence of liposomes, and free OhyA protein. The picked particles were first inspected by Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC) score and local power to help partially discriminate OhyA bound to liposome patches from that of multimer ring structures and free protein. The particles were then extracted using a box size of 288 pixels to allow discrimination of OhyA bound to small liposome patches in a subsequent 2D classification. Six ab initio reconstructions were generated from the selected 2D classification particles. Hetero refinement was performed on the OhyA-bound liposome patch class. Particles from this class were aligned using non-uniform refinement. Templates were prepared from the OhyA-bound liposome patch reconstruction low pass filtered to 20 Å to pick particles from the complete data set. Duplicate particles picked from the same liposome were removed and then the remaining particles were extracted with a box size of 640 pixels. Three ab initio reconstructions were generated following 2D classification of the complete OhyA-bound liposomes. Hetero refinement was performed on the OhyA-bound complete liposome class. Particles from this class were again aligned using non-uniform refinement. 3D classification was again performed to further remove OhyA multimer ring structure particles in the absence of liposomes.

The resolution of the dimer of dimers and OhyA-bound liposome reconstructions were determined from two halves of the data from a gold standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of reconstructions generated at the cutoff criterion of 0.143 (Figs. S3, S4). The final maps were locally masked and sharpened using DeepEMhancer (Sanchez-Garcia et al., 2021). Estimation of local resolution were performed using Blocres (Heymann, 2018).

Model building, refinement, and validation

The coordinates for dimeric OhyA (PDB ID: 7KAV) were docked into the dimer of dimers and OhyA-bound liposome reconstructions using rigid body fitting in Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). For the dimer of dimers OhyA structure a real space refinement was performed using one of the half maps in PHENIX (Afonine et al., 2018). For the OhyA-bound liposome structure, refinement was performed in Refmac in CCPEM (Burnley et al., 2017) using the half maps and ProSMART restraints for the lower resolution OhyA dimers at both ends of the partial oligomeric rings. The final models were validated using MolProbity (Williams et al., 2018). Figures were created in ChimeraX (Meng et al., 2023) and PyMOL (DeLano, 2002).

Prediction of Gibbs binding free energy

The cryo-EM structures of the OhyA dimer (PDB ID: 8UR3) and OhyA dimer of dimers (PDB ID: 8UR8) were uploaded to the HawkDock server (http://cadd.zju.edu.cn/hawkdock/) for an unbiased analysis of the intermolecular contacts between protomers, as described previously (Radka and Rock, 2024). Molecule A in the OhyA dimer and molecules A and B in the OhyA dimer of dimers were defined as the receptor in the MM/GBSA HawkDock jobs. HawkDock predicted the Gibbs binding free energies and ranked key residues that play an essential role in the protein-protein interactions (Weng et al., 2019).

The Gibbs binding free energy is calculated using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) methodology (Gohlke and Case, 2004). MM/GBSA estimates hydrophobic interactions/nonpolar contributions from changes in solvent accessible surface area, and electrostatic solvation energy/polar contributions from the finite-difference Poisson-Boltzmann equation (Hou et al., 2011). Normal-mode analysis is used for entropy calculations that are computed independently of the internal dielectric constant (Hou et al., 2011). The entropy calculations estimate conformational and vibrational entropy, but do not account for anharmonic effects (Hou et al., 2011).

To relate Gibbs binding free energy to binding affinity, the Gibbs binding free energies (ΔG in kcal/mol) were converted to equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) using the formula: ΔG = R×T×ln(KD) where R is the gas constant 1.98722 × 10−3 kcal/mol•K and T is the temperature (298.15 K). Rearranged, the formula is KD=eΔG/R×T.

Data availability

The cryo-EM reconstructions and associated maps of the OhyA dimer of dimers and OhyA•membrane complex are deposited in the EMDB with accessions EMD-42487 and EMD-43965 respectively, in the Protein Data Bank with accessions 8UR8 and 9AXE, respectively.

RESULTS

Cryo-EM structure of the OhyA dimer of dimers

In our initial cryo-EM experiments to determine the cryo-EM OhyA dimer structure (Radka et al., 2024), we observed particles that were instead dimer of dimers that accumulated at the air-water interface (Fig. S5). Addition of 50 μM LMNG detergent partially dispersed these particles into freely oriented OhyA dimers and a subset of dimer of dimers still oriented towards the air-water interface. Increasing amounts of LMNG up to 1 mM LMNG shifted the particle distribution from dimeric OhyA towards more freely oriented dimer of dimers (Fig. S1), enabling structure determination of the OhyA dimer of dimers to 2.97 Å (Table 1, Figs. 2, S1, S3). In the presence of 1 mM LMNG, higher oligomeric species of OhyA coils were also occasionally observed (Fig. S1). The OhyA dimer of dimers reconstruction was solved using C2 point group symmetry, which matches the C2 symmetry in the cryo-EM OhyA dimer structure (Radka et al., 2024) and the OhyA crystal structure (Radka et al., 2021b). The OhyA subunits in the dimer of dimers reconstruction had the same completeness as the original crystal structure (PDB ID: 7KAV) and cryo-EM dimer reconstruction (PDB ID: 8UR3), only lacking residues 61–74 from the FAD lobe in each subunit (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, model composition, refinement, and validation parameters

| Structure | OhyA dimer of dimers | OhyA•membrane complex |

|---|---|---|

| EMDB ID | EMD-42487 | EMD-43965 |

| PDB ID | 8UR8 | 9AXE |

| Data collection | ||

| Microscope | Talos Arctica (FEI) | Talos Arctica (FEI) |

| Voltage (kV) | 200 | 200 |

| Detector | K3 BioQuantum (Gatan) | K3 BioQuantum (Gatan) |

| Magnification | 79,000 | 79,000 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.044 | 1.044 |

| Defocus range (μM) | −0.5 to −2.0 | −0.5 to −2.25 |

| Movies | 276 | 15.784 |

| Frames/movie | 50 | 50 |

| Total dose (electrons/Å2) | 50 | 54 |

| Model composition | ||

| Chains | 4 | 14 |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 18752 | 65632 |

| Protein residues | 2316 | 8106 |

| Refinement | ||

| Initial model (PDB ID) | 7KAV | 8UR3 |

| Number of particles | 73,589 | 87,806 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.97 | 3.09 |

| RMS deviations | ||

| Bond length (Å) (# > 4σ) | 0.006 (0) | 0.004 (0) |

| Bond angles (°) (# > 4σ) | 0.635 (0) | 0.812 (0) |

| Validation | ||

| MolProbity score | 1.39 | 1.49 |

| Clash score | 4.88 | 6.46 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Allowed | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Favored | 97.3 | 97.3 |

| Rotamers (%) | ||

| Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Favored | 99.7 | 99.8 |

| Cβ outliers (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Peptide plane (%) | ||

| Cis proline/general | 0.0/0.2 | 0.0/0.2 |

| Twisted proline/general | 0/0 | 0/0 |

Figure 2. Stabilization of the OhyA dimer of dimers.

A, The OhyA protomer contains three functional domains: fatty acid lobe (green), FAD lobe (yellow), and membrane binding domain (blue). OhyA is dimeric, and the OhyA dimers can form a higher oligomer dimer of dimers. Only one interaction between amino acids was predicted to yield a free energy contribution with a KD ≤ 10−4 M (Fig. 1). This interaction is at the base of the structure (indicated by black boxes), and a zoomed-in view shows a salt bridge (black dashed lines) between Arg-324 in the FAD lobe of one dimer and Glu-362′ and Asp-368′ in the fatty acid lobe of the opposite dimer. The van der Waals surfaces (dots) show the residues make van der Waals contacts. B, Orthogonal views of the expanded OhyA crystal lattice (PDB ID: 7KAV). Superimposition of the dimer of dimers onto OhyA molecules (gray) in the center of the lattice shows the dimer of dimers maintains the same intermolecular contacts as the OhyA molecules in the crystal lattice.

Stabilization of OhyA oligomerization

We used the cryo-EM structure of the OhyA dimer (PDB ID: 8UR3) (Radka et al., 2024) to compute the overall Gibbs binding free energy for the dimerization of protomers, and found a favorable association that is estimated to occur with −190.8 kcal/mol. Decomposition of the free energy contribution on a per residue basis (Fig. 3) found residues in the interacting α-helices of the dimerization interface (Radka et al., 2021b) form the most favorable interactions. A Gibbs binding free energy change of −5.5 kcal/mol corresponds to an interaction with a micromolar dissociation constant and was investigated in greater detail. This energy change is created by hydrogen bonds, two guanidinium cation-π interactions (Blanco et al., 2011), and a four-membered π-teeing perpendicular T-shaped (edge-to-face) interaction that stabilize the dimerization interface. Arg-13 is the only residue whose interactions produces a Gibbs free energy change (−10.38 kcal/mol) that corresponds to a nanomolar dissociation constant. An additional hydrogen bond and three membered π-teeing perpendicular T-shaped interaction connecting the carboxy terminus and fatty acid lobe contribute favorable interactions that support dimerization.

Figure 3. Decomposition of the predicted Gibbs binding free energy of OhyA oligomerization by amino acid residue.

The free energy contributions of each amino acid to the binding free energy of an OhyA dimer (cyan) or dimer of dimers (purple and gray) were predicted using the HawkDock MM/GBSA server (http://cadd.zju.edu.cn/hawkdock/). The receptor protomer molecule for the dimer was chain A (cyan), and the receptor dimer molecule for the dimer of dimers were chains A (purple) and B (gray). The dissociation constant (KD) was calculated from the Gibbs binding free energy (ΔG) using the formula ΔG=RTln(KD) (see Materials and Methods). Free energy contributions with a KD ≤ 10−4 M are indicated by a transparent orange box, and free energy contributions with a KD ≤ 10−7 M are indicated by a transparent red box. Secondary structural elements containing the amino acids that engage in the highest affinity interactions are indicated.

We computed the overall Gibbs binding free energy change for the formation of the OhyA dimer of dimers cryo-EM structure, and found an unfavorable association with +142.2 kcal/mol. Decomposition of the free energy contribution on a per residue basis (Fig. 3) found only a single residue (Arg-324) produced an interaction with a Gibbs free energy change (−7.64 kcal/mol) that corresponded to a micromolar dissociation constant. The Arg-324 side chain in the FAD lobe of one protomer forms a salt bridge and is in van der Walls contact with the side chains of Glu-362 and Asp-368 in the fatty acid lobe from the opposite protomer (Fig. 2A).

Cryo-EM reconstruction of the OhyA dimer of dimers shows the same intermolecular contacts that are observed in the expanded OhyA C2 crystal lattice with an RMSD of 0.676 Å (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the intermolecular association of the OhyA dimer of dimers is seemingly concentration-dependent (e.g., via crystallography) or chemically-dependent in solution (e.g., via detergent). In sum, each domain of the protein plays a role in assembly – the lobes stabilize dimer contacts and the overall fold, while the carboxy terminus stabilizes membrane binding (Radka et al., 2024) and contributes an interaction that supports dimerization.

Cryo-EM structure of the OhyA•membrane complex

We previously measured an OhyA•membrane binding affinity of KD = 125.6 nM (ΔG≈ −9.4 kcal/mol) and observed an OhyA•liposome association by cryo-EM (Radka et al., 2024), which indicated achieving an OhyA•membrane bilayer complex structure was feasible.

In our preparation of POPC:POPG liposomes, most liposomes had 20–30 nm diameters with a smaller fraction of larger liposomes with sizes approaching 100 nm diameter (Fig. S2). OhyA was found to only bind the smallest liposomes with no indication that OhyA could bind larger liposomes as formed nor induce a bud on these larger liposomes. The total number of lipids in a liposome (Ntot) with a 25 nm diameter (d) and bilayer width (h) of 4 nm, comprised of lipids with phosphatidylcholine headgroups with a square area (a) of 0.71 nm2, is approximately 4000 lipids (Nanosciences, 2009) according to the following formula, adapted from (Nanosciences, 2009).

Our final OhyA•liposome sample had a 0.015 M lipid concentration (Mlipid), suggesting that if all the liposomes were approximated with 25 nm diameters, then the effective liposome concentration (Clipid) would be 3.7 μM according to the following formula.

Our final OhyA•liposome sample had an OhyA concentration of 20.8 μM (assuming dimers), thus if all OhyAs are membrane associated then each 25 nm liposome would bind 5–6 OhyA dimers. Micrographs collected on the OhyA•liposome sample showed most of the smallest liposomes were bound to multiple copies of OhyA (Fig. S2). At these lipid and protein concentrations, there were also OhyA particles that were found as free dimers and oligomeric rings (Figs. S2, S6). A three-fold reduction of OhyA to 6.9 μM protein while keeping lipids constant at 15 mM showed a near complete reduction in OhyA-bound liposomes (data not shown), suggesting the association of OhyA dimers into higher assemblies on the membrane bilayer is highly cooperative.

The OhyA-bound liposome reconstruction allows the docking of seven OhyA dimers comprising a partial polymeric assembly (Figs. 4A, S3, S4) although OhyA-bound liposomes with a complete polymeric assembly around the entirety of the liposome circumference are observed in the micrographs and 2D classification projections (Figs. 4C, S2). The OhyA-bound liposome reconstruction at low contour also suggests an extension of the assembly around the periphery of the liposome (Figs. S2, S4). The limitation of docking seven OhyA dimers in the partial assembly is likely the consequence of differences at the edges of the assemblies when aligning liposomes that vary in size from 20–30 nm. The partial OhyA polymeric assembly has a slight twist with a displacement of roughly 110 Å per revolution assuming a perfect spheroid (Fig. S7). This displacement is about 10 Å larger than the dimension of the OhyA dimer. A complete revolution would employ ≈16 OhyA dimers, the majority of whose CTDs would be in close contact with the prolate liposome. Following a complete revolution, the 20–30nm liposomes would be unable to accommodate additional OhyA binding given this displacement (Fig. S7). Some liposomes in the micrographs and 2D classification projections appear to bind two partial polymeric assemblies that are oriented orthogonal to each other. Indeed, evidence of an orthogonal partial polymeric assembly can be seen in the 2D projections (Fig. S2) and as diffuse density in a low contour rendering of the reconstruction (Fig. S7); however, the diffuse density of an additional polymeric assembly is likely the consequence of combining particles with one or to partial assemblies.

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the OhyA•membrane complex.

A, View of the OhyA-bound liposome from above the protein assembly. OhyA dimers are colored by chain alternating between green/purple and blue/gold. B, Orthogonal slab through A. C, Representative 2D classification projection corresponding to the view in B. Scale bar corresponds to 25 nm. D, zoomed-in view of the reconstruction showing CTD intercalation into the phosphate head group region of the liposome outer leaflet. A lower contour rendering of the map is included in gray mesh to show the liposome. E, Orthogonal slab of the reconstruction perpendicular to the protein assembly showing the deviation of spheroid symmetry. F, Representative 2D classification projection corresponding to the view in E. Scale bar corresponds to 25 nm.

The CTD of each OhyA subunit does not insert into the membrane leaflet but instead intercalates at the top edge of the bilayer where it would be surrounded by the phosphate head groups of the lipids (Fig. 4D). This aligns with our previous findings, indicating that phosphate increases the helicity observed in the circular dichroism spectra of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the OhyA CTD sequence (Radka et al., 2024). Additionally, it corresponds to the behavior of the same peptide when interacting with the phosphate layer of the membrane leaflet in molecular dynamics simulations (Radka et al., 2024). Diffuse low-resolution densities can also be seen in the cleft formed between the two CTDs of each OhyA dimer. Presumably, this region can be bound weakly to lipid molecules with implications of fatty acid substrate uptake. The poorer density of the bilayer edge as compared to the OhyA polymer suggests that the interaction of the lipid head groups to the OhyA CTDs are not fixed (Fig. 4D). Intercalation of the OhyA dimer CTD in the outer leaflet of the liposome bilayer forms a ridge that causes a local deviation of spherical symmetry (Fig. 4E, F).

DISCUSSION

Biophysical and computational experiments have provided insight into the interactions between soluble proteins and membrane bilayers (Radka, 2023; Radka et al., 2024); however, empirical structures of their protein•membrane complexes have been elusive. The limited examples in the literature have revealed distinct trajectories of how proteins interact with the membrane surface.

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins are pore-forming monomers that use a carboxy terminus lipid binding domain for initial interaction with the membrane bilayer (Czajkowsky et al., 2004; Hotze and Tweten, 2012; Ramachandran et al., 2005; Shatursky et al., 1999; Tilley et al., 2005). The monomers assemble into a higher order oligomer on the membrane surface, and the protomers undergo a conformational change that inserts amphipathic β-hairpins into the membrane to disrupt the bilayer (Czajkowsky et al., 2004; Hotze and Tweten, 2012; Ramachandran et al., 2005; Shatursky et al., 1999). The monomers of Vibrio cholerae β-pore-forming cytolysins assemble into heptameric ring-like pores on the membrane with their β-hairpins forming a β-barrel with 14 antiparallel β-strands (De and Olson, 2011; Harris et al., 2002). The Photorhabdus luminescens toxin complex is an α-pore-forming cytolysin that uses a pentameric subunit (TcA) that assembles in the cytosol and then undergoes a conformational change after docking on the membrane surface to expose hydrophobic α helices that combine to form a transmembrane pore (Gatsogiannis et al., 2016). Phospholipase C-β contains a distal carboxy terminus lipid binding domain containing amphipathic helices (Lyon and Tesmer, 2013) but low resolution of a cryo-EM reconstruction of a protein•liposome complex could not resolve the atomic structure of the lipid binding domain on the membrane (Falzone and MacKinnon, 2023). Inclusion of lipid-anchored G protein (Gβγ) yielded a tripartite phospholipase•Gβγ•liposome complex that showed a conformational change that brings the phospholipase active site to the lipid binding domain and membrane surface without disrupting the bilayer (Falzone and MacKinnon, 2023).

Our cryo-EM analysis indicates the first cryo-EM structure of oligomeric OhyA bound to the near-physiological membrane lipid environment at an atomic resolution. Our study provides detailed structural information of the OhyA macromolecular ensemble on the membrane bilayer, where we notice intriguing parallels between the cryo-EM structure and the crystal structure (Radka et al., 2021b). OhyA dimer is the soluble unit (Radka et al., 2021b; Radka et al., 2024; Subramanian et al., 2019) and the carboxy terminus lipid binding domain enables initial interaction with the membrane bilayer. This study shows additional dimers are recruited to productively associate into higher order oligomers on the membrane surface after the initial interaction. The formation of an OhyA dimer and dimer of dimers in solution compared to higher order oligomers on liposomes suggest oligomer size is dependent on the assembly surface area. The 3D reconstruction shows the intermolecular contacts between dimers in the context of the membrane assembly are the same contacts that occur between dimers in the OhyA crystal lattice (Fig. 2B). This observation indicates these biophysical interactions are a thermodynamic solution for minimizing the entropy and free energy cost of eliminating rotational and diffusional degrees of freedom from the molecule. Moreover, the stability of oligomer complexes in the membrane may also be significantly influenced by the multi-valent avidity effect of near-native, membrane-bound OhyA oligomers. The structural conservation of the membrane-binding domain across orthologs within the OhyA protein family suggests that the current observation provides a general explanation of how OhyA uses amphipathic helices to bind to membranes.

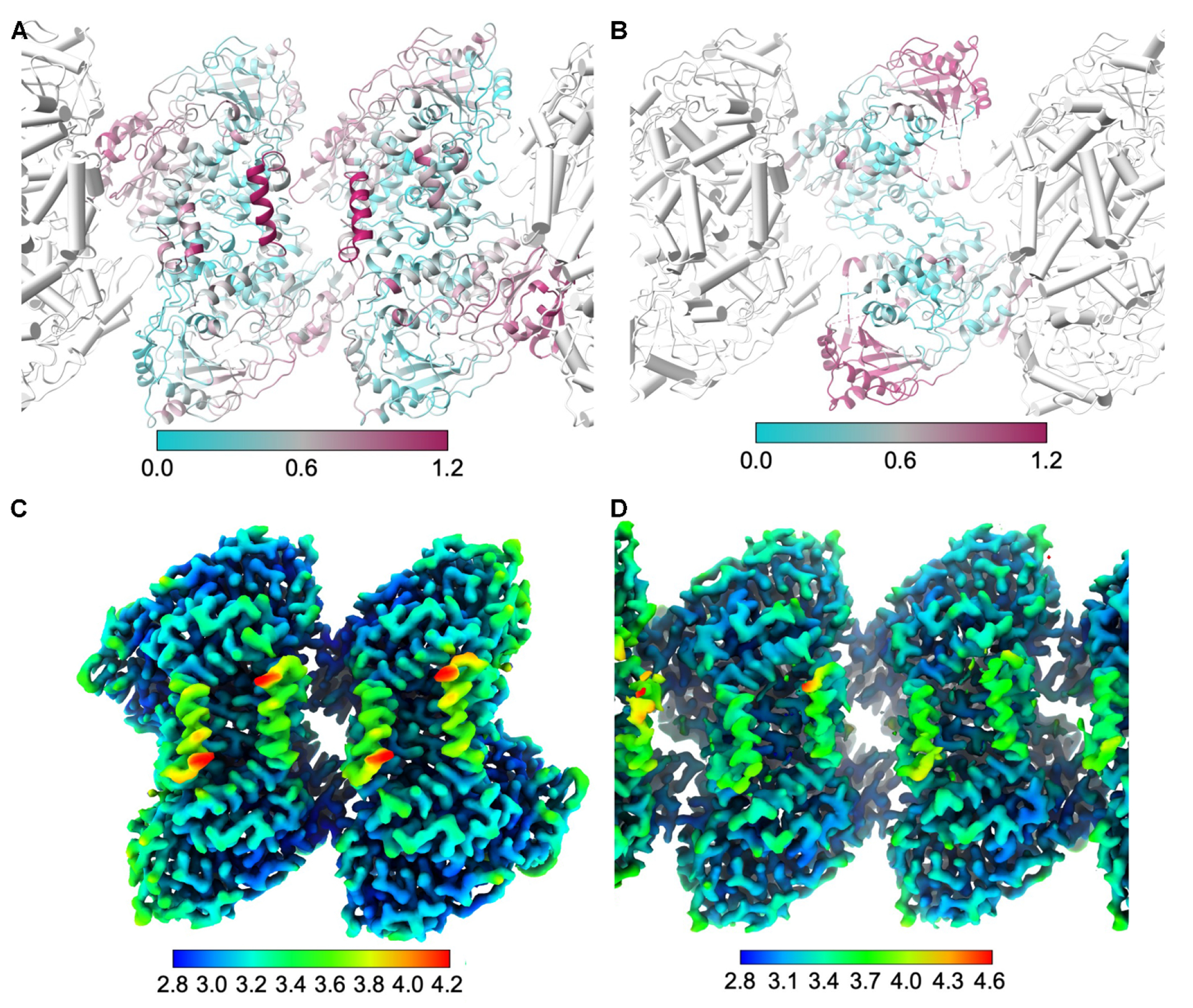

An open question is how OhyA takes up fatty acid substrate and releases hydroxy fatty acid product while remaining bound to the membrane bilayer. Previously we used cryo-EM 3D variability analysis to show the free dimeric form of OhyA is comprised of species with either fully ordered domains or a disordered CTD/partially disordered FAD lobe (Radka et al., 2024). This disordering could enable fatty acid substrate uptake; however, it is unclear how the CTD could become disordered while OhyA is bound to the membrane bilayer or how/if the CTD communicates with the FAD lobe to influence catalysis. OhyA assembly along the membrane bilayer might allow temporary disordering of the CTD of one OhyA dimer while it remains fixed on the membrane bilayer by its association with other neighboring OhyA dimers employing fully ordered CTDs (Fig. 5). The intermolecular interactions between dimers in the OhyA-bound liposome reconstruction are the same as those between dimers in the dimer of dimers state with an average RMSD of 0.427 Å (Fig. 6A). The 3D variable disordered CTD/partially disordered FAD lobe form of OhyA also fits well when superposed within the OhyA-bound liposome structure with no significant clashes in dimer-to-dimer contacts (Fig. 6B). In both states of OhyA, free and membrane-bound, the CTD has lower resolution than the bulk of the reconstruction (Fig. 6C, D) likely due to its position at the periphery of the molecule and innate flexibility.

Figure 5. Visualization of a dynamic OhyA dimer in the OhyA•membrane complex.

Top row, Different views of the OhyA dimer within the OhyA•membrane complex from above (A), side (B), and underneath (C). The central OhyA dimer is indicated by a dashed black box. Middle row (D–F), Depiction of the central OhyA dimer in the same views as the top row. Bottom row (G–I), Replacement of the central OhyA dimer with the superposed disordered CTD form of the free OhyA dimer (PDB ID: 8UR6). FAD molecules (spheres) are placed using superposition of the OhyA•18:1/h18:0•FAD crystal structure (PDB ID: 7KAZ). Oleic acid (OLA) molecules (spheres) are placed using superposition of the OhyA•18:1 crystal structure (PDB ID: 7KAY). Arrows depict regions of the disordered CTD and partially disordered FAD lobe.

Figure 6. Comparison of liposome-bound OhyA with other forms of OhyA.

A, Superposition of the OhyA dimer of dimers structure onto the liposome-bound OhyA structure (colored by RMSD). Unaligned liposome-bound OhyA protomers (gray) are rendered with cylindrical helices. B, Superposition of the OhyA dimer structure with a disordered CTD (PDB ID: 8UR6) onto the liposome-bound OhyA structure (colored by RMSD). C, Sharpened dimer of dimers reconstruction colored by estimated local resolution. D, Sharpened liposome-bound OhyA assembly reconstruction, focused on the central dimer and colored by estimated local resolution.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

OhyA carboxy terminus is a membrane binding domain used for interfacial activation

Cryo-EM dimer of dimers structure matches cryo-EM dimer and crystal structure packing

OhyA interaction with liposomal membrane drives dimer to high order oligomer switch

Acknowledgements–

We thank Sagar Chittori and Syed Asfarul Haque in the SJCRH Cryo-Electron Microscopy Center for assistance with cryo-EM data collection. We also thank Maria Falzone from the Laboratory of Molecular Neurobiology and Biophysics at Rockefeller University for helpful discussions in sample preparation.

Funding and additional information–

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-GM034496 (C.O.R.) and R00-AI166116 (C.D.R.), Cancer Center Support Grant CA21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The abbreviations used are:

- OhyA

oleate hydratase

- Cryo-EM

cryo-electron microscopy

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol)

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- LMNG

lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol

- CTD

carboxy terminus domain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest–The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

- Afonine PV, Klaholz BP, Moriarty NW, Poon BK, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Adams PD, Urzhumtsev A, 2018. New tools for the analysis and validation of cryo-EM maps and atomic models. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 814–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambati S, Ferarro AR, Kang SE, Lin J, Lin X, Momany M, Lewis ZA, Meagher RB, 2019. Dectin-1-targeted antifungal liposomes exhibit enhanced efficacy. mSphere 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besenicar M, Macek P, Lakey JH, Anderluh G, 2006. Surface plasmon resonance in protein-membrane interactions. Chem. Phys. Lipids 141, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco F, Kelly B, Alkorta I, Rozas I, Elguero J, 2011. Cation-π interactions: complexes of guanidinium and simple aromatic systems. Chem Phys Lett 511, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bulbake U, Doppalapudi S, Kommineni N, Khan W, 2017. Liposomal formulations in clinical use: An updated review. Pharmaceutics 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnley T, Palmer CM, Winn M, 2017. Recent developments in the CCP-EM software suite. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 73, 469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Davidson N, Juozaityte E, Erdkamp F, Pluzanska A, Azarnia N, Lee LW, 2004. Phase III trial of liposomal doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide compared with epirubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol 15, 1527–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RB, Kalmar GB, Kay RJ, Johnson MA, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, 1995. Functions of the C-terminal domain of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Effects of C-terminal deletions on enzyme activity, intracellular localization and phosphorylation potential. Biochem. J 310 (Pt 2), 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowsky DM, Hotze EM, Shao Z, Tweten RK, 2004. Vertical collapse of a cytolysin prepore moves its transmembrane β-hairpins to the membrane. EMBO J. 23, 3206–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Olson R, 2011. Crystal structure of the Vibrio cholerae cytolysin heptamer reveals common features among disparate pore-forming toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 7385–7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL, 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K, 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzone ME, MacKinnon R, 2023. Gβγ activates PIP2 hydrolysis by recruiting and orienting PLCβ on the membrane surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 120, e2301121120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Xu W, Li Z, Song W, Ding J, Chen X, 2019. Immunomodulatory nanosystems. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 6, 1900101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatsogiannis C, Merino F, Prumbaum D, Roderer D, Leidreiter F, Meusch D, Raunser S, 2016. Membrane insertion of a Tc toxin in near-atomic detail. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 23, 884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H, Case DA, 2004. Converging free energy estimates: MM-PB(GB)SA studies on the protein-protein complex Ras-Raf. J. Comput. Chem 25, 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Bhakdi S, Meissner U, Scheffler D, Bittman R, Li G, Zitzer A, Palmer M, 2002. Interaction of the Vibrio cholerae cytolysin (VCC) with cholesterol, some cholesterol esters, and cholesterol derivatives: a TEM study. J. Struct. Biol 139, 122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann JB, 2018. Guidelines for using Bsoft for high resolution reconstruction and validation of biomolecular structures from electron micrographs. Protein Sci. 27, 159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotze EM, Tweten RK, 2012. Membrane assembly of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin pore complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 1028–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Wang J, Li Y, Wang W, 2011. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model 51, 69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeguchi S, Izumi Y, Kitamura N, Kishino S, Ogawa J, Akaike A, Kume T, 2018. Inhibitory effect of the gut microbial linoleic acid metabolites, 10-oxo-trans-11-octadecenoic acid and 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic acid, on BV-2 microglial cell activation. J. Pharmacol. Sci 138, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar GB, Kay RJ, Lachance A, Aebersold R, Cornell RB, 1990. Cloning and expression of rat liver CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: an amphipathic protein that controls phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87, 6029–6033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C, Dudkina NV, Lukoyanova N, Hodel AW, Farabella I, Pandurangan AP, Jahan N, Pires Damaso M, Osmanovic D, Reboul CF, Dunstone MA, Andrew PW, Lonnen R, Topf M, Saibil HR, Hoogenboom BW, 2014. Stepwise visualization of membrane pore formation by suilysin, a bacterial cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. Elife 3, e04247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanova N, Kondos SC, Farabella I, Law RH, Reboul CF, Caradoc-Davies TT, Spicer BA, Kleifeld O, Traore DA, Ekkel SM, Voskoboinik I, Trapani JA, Hatfaludi T, Oliver K, Hotze EM, Tweten RK, Whisstock JC, Topf M, Saibil HR, Dunstone MA, 2015. Conformational changes during pore formation by the perforin-related protein pleurotolysin. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AM, Tesmer JJ, 2013. Structural insights into phospholipase C-β function. Mol. Pharmacol 84, 488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malachowa N, Kohler PL, Schlievert PM, Chuang ON, Dunny GM, Kobayashi SD, Miedzobrodzki J, Bohach GA, Seo KS, 2011. Characterization of a Staphylococcus aureus surface virulence factor that promotes resistance to oxidative killing and infectious endocarditis. Infect. Immun 79, 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng EC, Goddard TD, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Pearson ZJ, Morris JH, Ferrin TE, 2023. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 32, e4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto J, Mizukure T, Park SB, Kishino S, Kimura I, Hirano K, Bergamo P, Rossi M, Suzuki T, Arita M, Ogawa J, Tanabe S, 2015. A gut microbial metabolite of linoleic acid, 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic acid, ameliorates intestinal epithelial barrier impairment partially via GPR40-MEK-ERK pathway. J. Biol. Chem 290, 2902–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanosciences E 2009. The number of lipid molecules per liposome.

- Pang SS, Bayly-Jones C, Radjainia M, Spicer BA, Law RHP, Hodel AW, Parsons ES, Ekkel SM, Conroy PJ, Ramm G, Venugopal H, Bird PI, Hoogenboom BW, Voskoboinik I, Gambin Y, Sierecki E, Dunstone MA, Whisstock JC, 2019. The cryo-EM structure of the acid activatable pore-forming immune effector macrophage-expressed gene 1. Nat. Commun 10, 4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter BJ, Kent HM, Mills IG, Vallis Y, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT, 2004. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science 303, 495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA, 2017. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radka CD, 2023. Interfacial enzymes enable Gram-positive microbes to eat fatty acids. Membranes (Basel) 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radka CD, Rock CO, 2024. Crystal structures of the fatty acid biosynthesis initiation enzymes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Struct. Biol 216, 108065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radka CD, Batte JL, Frank MW, Rosch JW, Rock CO, 2021a. Oleate hydratase (OhyA) is a virulence determinant in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr 9, e0154621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radka CD, Batte JL, Frank MW, Young BM, Rock CO, 2021b. Structure and mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus oleate hydratase (OhyA). J. Biol. Chem 296, 100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radka CD, Grace CR, Hasdemir HS, Li Y, Rodriguez CC, Rodrigues P, Oldham ML, Qayyum MZ, Pitre A, MacCain WJ, Kalathur RC, Tajkhorshid E, Rock CO, 2024. The carboxy terminus causes interfacial assembly of oleate hydratase on a membrane bilayer. J. Biol. Chem 300, 105627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Tweten RK, Johnson AE, 2005. The domains of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin undergo a major FRET-detected rearrangement during pore formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 7139–7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richnau N, Fransson A, Farsad K, Aspenstrom P, 2004. RICH-1 has a BIN/Amphiphysin/Rvsp domain responsible for binding to membrane lipids and tubulation of liposomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 320, 1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Garcia R, Gomez-Blanco J, Cuervo A, Carazo JM, Sorzano COS, Vargas J, 2021. DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun. Biol 4, 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta N, Mondal AK, Mishra S, Chattopadhyay K, Dutta S, 2021. Single-particle cryo-EM reveals conformational variability of the oligomeric VCC β-barrel pore in a lipid bilayer. J. Cell. Biol 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sercombe L, Veerati T, Moheimani F, Wu SY, Sood AK, Hua S, 2015. Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front. Pharmacol 6, 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforzi J, Palagi L, Aime S, 2020. Liposome-based bioassays. Biology (Basel) 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatursky O, Heuck AP, Shepard LA, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, Tweten RK, 1999. The mechanism of membrane insertion for a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin: a novel paradigm for pore-forming toxins. Cell 99, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian C, Frank MW, Batte JL, Whaley SG, Rock CO, 2019. Oleate hydratase from Staphylococcus aureus protects against palmitoleic acid, the major antimicrobial fatty acid produced by mammalian skin. J. Biol. Chem 294, 9285–9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei K, Slepnev VI, Haucke V, De Camilli P, 1999. Functional partnership between amphiphysin and dynamin in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol 1, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatulian SA, 2017. Interfacial enzymes: Membrane binding, orientation, membrane insertion, and activity. Methods. Enzymol 583, 197–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley SJ, Orlova EV, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Saibil HR, 2005. Structural basis of pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. Cell 121, 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kent C, 1995. Identification of an inhibitory domain of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem 270, 18948–18952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng G, Wang E, Wang Z, Liu H, Zhu F, Li D, Hou T, 2019. HawkDock: a web server to predict and analyze the protein-protein complex based on computational docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W322–W330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, Jain S, Lewis SM, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Adams PD, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, 2018. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Gao H, Stanton C, Ross RP, Zhang H, Chen YQ, Chen H, Chen W, 2017a. Bacterial conjugated linoleic acid production and their applications. Prog. Lipid Res 68, 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HE, Li Y, Nishimura A, Jheng HF, Yuliana A, Kitano-Ohue R, Nomura W, Takahashi N, Kim CS, Yu R, Kitamura N, Park SB, Kishino S, Ogawa J, Kawada T, Goto T, 2017b. Synthesized enone fatty acids resembling metabolites from gut microbiota suppress macrophage-mediated inflammation in adipocytes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Fan X, Yan N, 2020. Cryo-EM analysis of a membrane protein embedded in the liposome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117, 18497–18503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM reconstructions and associated maps of the OhyA dimer of dimers and OhyA•membrane complex are deposited in the EMDB with accessions EMD-42487 and EMD-43965 respectively, in the Protein Data Bank with accessions 8UR8 and 9AXE, respectively.