Summary

Efficient methods of stacking genes into plant genomes are needed to expedite transfer of multigenic traits to crop varieties of diverse ecosystems. Over two decades of research has identified several DNA recombinases that carryout efficient cis and trans recombination between the recombination sites artificially introduced into the plant chromosome. The specificity and efficiency of recombinases make them extremely attractive for genome engineering. In plant biotechnology, recombinases have mostly been used for removing selectable marker genes and have rarely been extended to more complex applications. The reversibility of recombination, a property of the tyrosine family of recombinases, does not lend itself to gene stacking approaches that involve rounds of transformation for integrating genes into the engineered sites. However, recent developments in the field of recombinases have overcome these challenges and paved the way for gene stacking. Some of the key advancements include the application of unidirectional recombination systems, modification of recombination sites and transgene site modifications to allow repeated site‐specific integrations into the selected site. Gene stacking is relevant to agriculturally important crops, many of which are difficult to transform; therefore, development of high‐efficiency gene stacking systems will be important for its application on agronomically important crops, and their elite varieties. Recombinases, by virtue of their specificity and efficiency in plant cells, emerge as powerful tools for a variety of applications including gene stacking.

Keywords: gene stacking, site‐specific recombination, multigene transformation, genome engineering, cre‐lox, FLP‐FRT

Introduction

Continuous improvement of crops by incorporating new genes in plant varieties is extremely important for ensuring agricultural productivity in optimal and adverse climactic conditions. Often multiple genes are required to manage a single trait that may need to be deployed over a period of time; for example, multiple genes of insect resistance or herbicide tolerance are needed to manage evolving resistance against chemicals used to suppress pests and weeds in the field (Keweshan et al., 2015; Que et al., 2010; Storer et al., 2012). On the other hand, many important traits are encoded by more than one gene, requiring incorporation of multiple loci. For example, salt tolerance is a complex trait involving multiple genes for osmotic adjustment, ion exclusion and compartmentalization (Munns and Tester, 2008).

Trait transfer from the donor parent to cultivars involves chromosomal recombination; therefore, transfer of multiple genes through plant breeding is exponentially complex. The projected number of F2 plants derived from a self‐fertilized F1 hybrid increases from 16 to >1 million with the increase in genes from 2 to 10 (4^n, n = number of genes). Further, as the transfer of undesirable alleles from the parent plant cannot be avoided, plant selection is practically more complex.

Planting of genetically engineered (GE) crops with stacked traits is rapidly increasing, a trend that is expected to continue with the increasing number of triple and quadruple stacks potentially made available through plant breeding (http://www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/pocketk/42/). Combining traits by breeding could be extremely challenging to practice with a high number of genes, in which multiple donor (transgenic) lines will have to be crossed with cultivars to develop GE varieties for diverse environments or production systems. However, if the transgenes are stacked in a single chromosomal site, plant breeding and variety development will be greatly simplified due to co‐inheritance of the stacked transgenes. Therefore, practical approaches for gene stacking through genetic engineering are urgently needed to expedite variety development. In the continuous improvement of crops, not only multigene engineering may be needed to express complex traits, but also an incremental approach will be useful to introduce new transgenes into the previously engineered crops. Introduction of multiple genes (or gene cassettes) in a single transformation and to iteratively add new genes to the engineered sites are some of the bottlenecks in plant biotechnology. Targeted gene insertion approaches that enable the insertion of genes to a specified genomic site are the primary components of the gene stacking technology. Currently, two distinct approaches for targeted gene insertion are available, broadly classified as DNA double‐stranded break (DSB) and site‐specific recombination (SSR) technologies. Enhanced rates of DNA insertion into the DSB sites in plant genomes via homologous recombination (HR) or nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) serve as the basis of targeted gene insertion (Chilton and Que, 2003; Puchta et al., 1996; Tzfira et al., 2003), and the development of designer nucleases has been critical in the implementation of this approach (Ainley et al., 2013). This review focuses on the SSR technologies, their mechanisms, precision and efficiencies, and potential for targeted gene insertion and gene stacking for plant biotechnology.

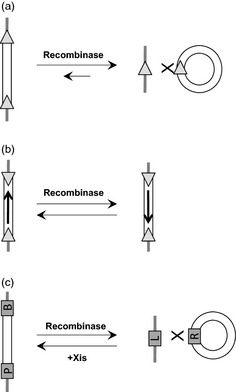

Site‐specific recombination (SSR) systems carry out a conservative DNA recombination between specific target sites leading to a precise outcome such as integration, excision or inversion of the DNA where orientation of the recognition sites determines the mode of action (Figure 1a–c) (Gaj et al., 2014; Grindley et al., 2006; Ow, 2002; Sauer, 1994). These recombination outcomes are generally reversible, but some SSR systems require a helper protein to reverse the reaction, allowing control over the reversibility (Figure 1c). Further, as SSR systems carry out a specific biological function in the host cells, they have evolved to be highly specific to their target sites, thereby allowing recombination only between the specific sites introduced in the heterologous genomes or between the pseudo‐sites that are occasionally found in plant or animal genomes (Corneille et al., 2003; Thyagarajan et al., 2000, 2001). A number of SSR applications have been developed for plant biotechnology that include marker gene excision and transgene integration. A detailed review on the development of SSR systems and their application in plants is given in the accompanying article in this issue of Plant Biotechnology Journal. The first application, developed 25 years ago, is the excision of selectable marker gene from the transgene locus (Dale and Ow, 1991; Russell et al., 1992), quickly followed by site‐specific integration (SSI) to develop precise single‐copy transgene locus (Albert et al., 1995; Vergunst et al., 1998), and resolving complex locus to a single copy (De Buck et al., 2007; Srivastava and Ow, 2001, 2015; Srivastava et al., 1999). These applications were initially developed by the use of Cre‐lox system and later expanded to other SSR systems including FLP‐FRT, R‐RS, phiC31, ParA, CinH and Bxb1 (Li et al., 2009; Lyznik et al., 1996; Moon et al., 2011; Nanto et al., 2005; Sugita et al., 2000; Thomson et al., 2009, 2010, 2012). The toolbox of SSR systems continues to expand, and their applications in DNA excisions and integrations are seminal to recombinase‐mediated gene stacking in plants and other organisms.

Figure 1.

Site‐specific recombination of bidirectional and unidirectional recombination systems. (a–b) Bidirectional recombination systems such as Cre‐lox, FLP‐ FRT and R‐ RS carry out a freely reversible recombination between two identical recombination sites (grey triangles), and the recombination outcome depends on their relative orientation. (a) The recombination between two cis‐positioned sites, in the same orientation, results in excision of the intervening DNA fragment, while the reverse recombination leads to DNA integration. The recombination efficiency between two cis sites (forward reaction) is, however, much greater than between trans sites (reverse reaction), favouring excision over integration. (b) Recombination between two cis sites, in opposite orientation, results in the inversion of the intervening DNA fragment. As the product contains the same orientation and the position of the two sites, this reaction is freely reversible. (c) Unidirectional recombination systems that include phiC31 and Bxb1 systems consist of two distinct recombination sites, attP (P) and attB (B), which recombine to specific outcomes such as DNA excision (forward reaction) and integration (reverse reaction), leading to the formation of two distinct hybrid sites, attL (L) and attR (R). The reversibility of the reaction depends on the presence of a helper protein, excisionase (Xis), which assists the recombinase in catalysing a reaction between attL and attR.

Site‐specific recombination (SSR) systems

Site‐specific recombination systems have been discovered in bacteria and lower eukaryotes such as yeast, and found to promote biological functions, including the phase variation of bacterial virulence factors and the integration of bacteriophage into the host genome during a lysogenic life cycle. The recombinases can be split into two fundamental groups, the tyrosine and serine recombinases where the division is based on the active amino acid (Tyr or Ser) of the catalytic domain of each family. Both families can be further subdivided into unique members based on either size or mode of recombinase action (Table 1). The best characterized members of the tyrosine family include the Cre‐lox (Sauer and Henderson, 1990), FLP‐FRT (Golic and Lindquist, 1989) and R‐RS (Onouchi et al., 1991) systems, where Cre, FLP and R are tyrosine recombinase enzymes and lox, FRT and RS are the respective DNA recognition sites (Figure 2a). Because of the identical nature of the two recognition sites, the recombination reaction is fully reversible, although intramolecular recombination (excision) is highly favoured over intermolecular reactions (integration) (Figure 1a–b); therefore, these systems are bidirectional for recombination. Unidirectional tyrosine recombinases have nonidentical recognition sites typically known as attB (attachment site bacteria) and attP (attachment site phage) (Figure 2b) and perform irreversible recombination in the absence of a helper protein, termed an excisionase (Figure 1c). The unidirectional tyrosine recombinases that have been shown to be useful for genome manipulation include HK022 (Gottfried et al., 2005) and a modified form of lambda integrase (Chilton et al., 2002; Christ and Droge, 2002).

Table 1.

Site‐specific recombination systems and their applications in plants

| SSR system | Origin | Group | Applications in plantsa | SSI / RMCE efficiencyb | FTOc | Key references | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSE | SSI | RMCE | Stacking | ||||||

| Cre‐lox | P1 phage | Tyr | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | >50% | Yes | Albert et al. (1995), Dale and Ow (1991), Day et al. (2000), Chawla et al. (2006), Louwerse et al. (2007), Russell et al. (1992), Srivastava et al. (1999) |

| FLP‐FRT | Yeast 2‐μm plasmid | Tyr | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 20–30% | No, Pioneer | Li et al. (2009, 2010), Lyznik et al. (1996), Nandy and Srivastava (2011, 2012) |

| R‐RS | Yeast pSR1 plasmid | Tyr | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | ~5% | No, Japan Tobacco | Ebinuma et al. (2015), Nanto et al. (2005), Sugita et al. (2000) |

| Bxb1 | Mycobacteria | Ser‐Large | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | ~3% | Yes | Hou et al. (2014), Thomson et al. (2012) |

| phiC31 | Streptomyces | Ser‐Large | Yes | – | – | – | No, USDA & UC Berkeley | Dafhnis‐Calas et al. (2005), De Paepe et al. (2013), Kapusi et al. (2012), Thomson et al. (2010) | |

| CinH‐RS2 | pKLH plasmids | Ser‐Small | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | Moon et al. (2011) | |

| ParA‐MRS | pRP4 plasmid | Ser‐Small | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | Thomson et al. (2009) | |

Demonstrated applications in plants: site‐specific excision (SSE), site‐specific integration (SSI), cassette exchange (RMCE) and repeated site‐specific integrations (stacking).

% recovery of SSI and/or RMCE reported in individual studies that may be specific to selection strategy and plant species.

Freedom‐to‐operate in plants (patent holders or exclusive licensees given).

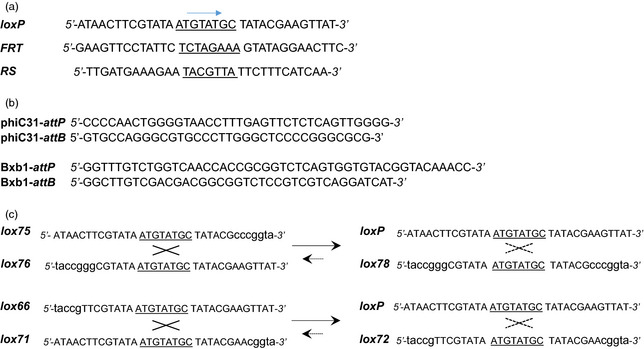

Figure 2.

Sequences of the recombination sites commonly used in the genome engineering applications. (a) Recombination sites of commonly used tyrosine recombinases, Cre‐lox, FLP‐ FRT and R‐ RS systems; underlined sequence is the spacer sequence flanked by inverted repeats. Arrow indicates the direction of the sites. (b) Recombination sites, attP and attB, of the serine recombinases, phiC31 and Bxb1. (c) Mutant lox sites that recombine to generate wild‐type loxP and double‐mutant lox sites, a principle used for stabilizing site‐specific integration. Lower‐case letters represent mutations. Lox sites containing mutations in the right element (RE, lox75, lox71) or left element (LE, lox76, lox66) recombine to produce loxP and double‐mutant sites (lox78, lox72). Dashed lines indicate greatly reduced interactions.

The serine recombinase family has two distinct members, the small serine subfamily, which contains β‐six (Diaz et al., 2001), γδ‐res (Schwikardi and Droge, 2000), CinH‐RS2 (Thomson and Ow, 2006) and ParA‐MRS (Thomson et al., 2009). While recombination mediated by these small serine recombinases (β, γδ, CinH and ParA) utilizes identical recognition sites (six, res, RS2 and MRS), only intramolecular excision events are observed. It has been determined that due to conformational strain imposed by the small serine recombinases during synaptonemal complex formation that intermolecular integration cannot be achieved (Mouw et al., 2008). Therefore, an excision event mediated by the small serine recombinases is considered irreversible. The large serine subfamily is represented by phiC31 (Rubtsova et al., 2008), TP901‐1 (Stoll et al., 2002), R4 (Olivares et al., 2001) and Bxb1 (Thomson and Ow, 2006) and have been considered an extremely useful group for genomic modification. Their two recognition sites differ in sequence, typically known as recognition sites attB and attP (Figure 2b), and yield hybrid product sites known as attL and attR after a recombination event. Excision, inversion or integration reactions are all possible with equal efficiency because the recognition site sequences of attB and attP are changed to attL and attR, making reverse reaction impossible without the addition of a second protein, the corresponding excisionase (Figure 1c) (Ghosh et al., 2006; Thorpe et al., 2000).

Recombinase‐mediated gene integration

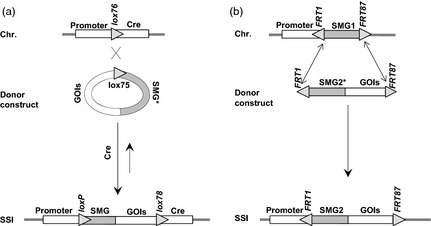

Plant transformation mostly involves random DNA integrations, resulting in the insertion of the introduced DNA into undetermined chromosomal sites. This nontargeted insertion mechanism is unsuitable for gene stacking. SSR systems can integrate DNA into predetermined sites by recombining specific DNA sequences located in the donor (vector) DNA and the chromosome (founder line). Two formats, involving single or double reciprocal crossovers that either insert a circular DNA into the chromosomal site (Figure 3a) or exchange a specific DNA fragment (Figure 3b), have been developed. The latter is popularly referred to as recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) that was first developed using Cre‐lox system in mouse cell line (Bouhassira et al., 1997), and since applied to plant biotechnology (discussed below).

Figure 3.

Strategies of recombinase‐mediated site‐specific integration of foreign gene into the plant chromosome (chr.). (a) Single reciprocal crossover or (b) double reciprocal crossover (also known as recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange or RMCE) between the recombination sites placed in plant chromosome and the introduced vector (donor construct) results in site‐specific integration (SSI) of the gene‐of‐interest (GOI). Three approaches are used for enhancing the SSI recovery rates: promoter trap that involves transcriptional fusion of the promoterless selectable marker gene (SMG*) with the promoter in the chromosomal target site (a‐b), use of mutant sites such as lox75 and lox76 that recombine (X) to produce the wild‐type loxP and the inert lox78 in the SSI site (a), and the use of heterospecific recombination sites such as FRT1 and FRT87 that facilitate two exclusive recombination reactions (up–down arrow) to exchange the fragment such as SMG1 with that of the donor construct to produce a selectable SSI structure due to SMG2 insertion. The reverse orientation of the FRT sites prevents excision due to infrequent interaction between the two heterospecific FRT sites.

Cre‐lox and FLP‐FRT are arguably the most efficient SSR systems that function exceptionally well in mammalian cells and plants (Gidoni et al., 2008; Schnütgen et al., 2006; Srivastava and Gidoni, 2010; Wang et al., 2011). The majority of the studies on Cre‐lox and FLP‐FRT applications have analysed their efficiency in excising a specified DNA fragment, for example excision of loxP‐flanked marker gene. However, as these SSR systems carryout a freely reversible recombination (bidirectional), they are also efficient at driving DNA integration into the chromosome (Srivastava and Ow, 2010; Table 1). It is, however, critical to include strategies to prevent the reversible recombination and stabilize the recombination outcome, that is gene integration. Two strategies have worked well in this regard: first, the use of mutant lox sites that recombine with each other to integrate DNA into the chromosome, and generate doubly mutated lox sites to halt the reversal (Figure 2c), and second, the use of transient gene expression to recede recombinase activity and stabilize the integration structure (Albert et al., 1995; Vergunst and Hooykaas, 1998).

Lox and FRT consist of inverted repeats, also called as ‘arms’ or ‘elements’ flanking a short spacer sequence (Figure 2a). The inverted repeats are the binding sites of Cre and FLP, respectively, while the spacer is the site for DNA nicking, the first step in DNA crossover. The lox sites containing 4‐ to 7‐bp mutation in one of the arms (LE: left element or RE: right element) can be used in site‐specific integration (SSI) of foreign DNA into plant chromosomes (Albert et al., 1995; Srivastava and Ow, 2001). Owing to the cooperativity in binding of Cre monomers to a lox site (Guo et al., 1997; Mack et al., 1992; Ringrose et al., 1998), the RE and LE mutants recombine efficiently to produce a doubly mutated lox (RE:LE) site and a wild‐type loxP site (Figure 2c). The RE:LE mutants, however, have greatly reduced binding with Cre, making them practically inactive (Figure 2c). This principle has worked well for site‐specific integrations in rice and tobacco, where, for example, lox76 placed in the plant genome recombined with lox75 located in the donor DNA to generate the SSI structure in 80–90% of the transformed clones (Albert et al., 1995; Srivastava et al., 2004). The resulting SSI structure was found to be stable in the plants despite the presence of Cre activity, with only occasional excisions observed in the mature leaves, indicating inertness of the double mutant, lox78 (Figure 3a). Similarly, lox66 recombines with lox71 to produce the double mutant, lox72, and the wild‐type loxP (Albert et al., 1995; Araki et al., 1997). Other mutant lox sites that have shown promise in other systems, yet to be tested in plants, include the two unique sites loxJTZ17 and loxKR3 (Araki et al., 2010; Thomson et al., 2003).

The FRT mutants that contain a single point mutation in either left or right FLP binding site (FRT46A and FRT46T) have also been described and found to be suitable for controlling the reversibility of recombination in E. coli, as the forward reaction was found to occur efficiently but the reverse reaction was undetectable (Huang et al., 1991). However, in rice cells FRT46A and FRT46T recombined reversibly (Nandy and Srivastava, unpublished data) and therefore deemed unsuitable for controlling recombination reversibility in plants. Additional point mutations or stretch of mutations in the arms of FRT sites have not been described, but there is no reason why ‘arm’ mutant FRT sites will not be useful, as FLP‐FRT recombination is mechanistically similar to Cre‐lox and FLP also shows cooperativity in binding to FRT sites (Ringrose et al., 1998). Transient FLP expression approach, in the meantime, has worked extremely well as co‐transformation of the donor DNA with FLP gene produced site‐specific integrations through FRT x FRT recombination at 20–30% efficiency (SSI events per experiment), and each recovered clone completely lacked the presence of FLP gene (Nandy and Srivastava, 2011). Similarly, transient Cre expression approach works well in stabilizing site‐specific integrations produced by lox x lox recombination in plants (Albert et al., 1995; Vergunst and Hooykaas, 1998). In summary, both Cre‐lox and FLP‐FRT systems, in combination with simple strategies to control their reversibility, generate impressive rates of site‐specific integrations in the plant genomes. The use of the thermostable FLP variant, FLPe, was, however, found to be important for generating high‐efficiency recombination in rice (Akbudak and Srivastava, 2011; Buchholz et al., 1998; Nandy and Srivastava, 2011).

Precision and efficiency of recombinase‐mediated gene integration

Precision and efficiency are the two most important criteria for the real‐world application of gene stacking approaches. In the targeted transformation approaches, precision is defined as the single‐copy integration of the specific DNA fragment, bordered by a set of recombination sites, without unpredictable gain or loss of DNA sequences within the SSI structure. This level of accuracy in SSI events has been observed in several studies on plants and mammalian cells, indicating high fidelity of SSR systems (Ow, 2002; Sauer, 2002). Earlier studies used PCR and Southern blotting methods to analyse SSI loci and found the presence of the predictable SSI structure in the vast majority of the recovered clones (Albert et al., 1995; Louwerse et al., 2007; Srivastava et al., 2004). More than 80% of the SSI lines of tobacco and rice, transformed by Cre‐lox‐mediated gene integration, were found to contain precise SSI locus (Day et al., 2000; Srivastava et al., 2004). High rates of precise SSI events are also generated by FLP‐FRT system as reported in the studies on FLP‐FRT‐mediated rice and soya bean transformations in which the donor DNA was delivered by the gene gun (Li et al., 2009; Nandy and Srivastava, 2011). Recent studies have used DNA sequencing methods to analyse SSI locus and frequently found high‐quality SSI lines that contain the predictable sequence (Hou et al., 2014; Li et al., 2009; Nandy and Srivastava, 2011).

It is important to note that extra copies of the donor DNA often integrate along with the SSI copy, due to random integrations, showing multicopy insertion patterns on Southern blots. Two studies reported the presence of extra integrations in about 50% of tobacco and rice SSI lines (Day et al., 2000; Srivastava et al., 2004). Random integrations, in the recovered clones, generally, do not disrupt the SSI structure and are located distant from the SSI locus (Chawla et al., 2006; Louwerse et al., 2007). The follow‐up analysis of the rice SSI lines revealed the segregation of extra copies through a single meiotic cycle, leading to the recovery of single‐copy SSI lines in the next generation (Chawla et al., 2006). These studies indicate that SSR systems carryout highly precise recombination between the specific sites located in the chromosome and the donor DNA. Hence, the recovery rate of precise SSI events mostly depends on the DNA sequence in the donor construct. Although tandem DNA sequences can be inserted by plant genomes, their stability in cell culture and plant life cycle is questionable. Akbudak et al. (2010) reported insertion of 3 tandem copies of transgenes in rice through Cre‐lox recombination that generated dosage‐dependent gene expression; however, transformation efficiency sharply declined with the increase in copy number in the donor construct. Li et al. (2010) reported the loss of a DNA fragment in soya bean SSI lines developed through FLP‐FRT recombination in one of the five recovered lines. Therefore, by avoiding repetitive sequences in the donor construct, which have the tendency to loop out as extra‐chromosomal circular copies (Cohen et al., 2008; Navrátilová et al., 2008), stability of SSI locus could be improved.

The efficiencies of site‐specific integrations (number of SSI events recovered per experiment) are determined by a number of factors including DNA delivery, target sites and SSR systems. First, the characteristics of the delivered DNA appear to be important; specifically, delivery of the purified DNA usually generates higher efficiencies than the delivery of T‐DNA by Agrobacterium (Srivastava and Gidoni, 2010), likely due to complex T‐strand processing in plant cells (Gelvin, 2012). Hooykaas and colleague, however, recovered a high rate of Cre‐mediated RMCE promoter‐trap events (44% of transformants) in Agrobacterium‐meditated transformation of Arabidopsis root explants (Louwerse et al., 2007). As expected, choice of SSR system is also an important determinant in the observed efficiencies of site‐specific integrations. Although the studies on the direct comparison of SSR systems are limited, generally higher site‐specific integration efficiencies have been reported with Cre‐lox and the optimized version of FLP‐FRT that utilizes FLPe (Buchholz et al., 1998; Raymond and Soriano, 2007). Other SSR systems that show a workable efficiency of site‐specific integrations in plants include R‐RS, Bxb1 and phiC31 systems (De Paepe et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2014; Nanto et al., 2005). Site‐specific gene integration in tobacco or Arabidopsis by R‐RS, phiC31 and Bxb1 systems was found in 3–9% of the recovered clones (De Paepe et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2014; Nanto et al., 2005). These levels may be improved by optimizing recombinase activity, for example through codon optimization. Hou et al. (2014) used the wild‐type version of the Bxb1 recombinase with C‐terminal NLS for enhancement. Thomson et al. (unpublished data) have shown that through codon optimization of the Bxb1, SSI recovery can be raised to 30% in tobacco. Finally, molecular strategy of site‐specific integration is an important consideration; specifically, strategies for selecting SSI events over random integrations significantly enhance SSI recovery rates. Mostly, promoter trapping is used as the selection strategy that involves activation of marker gene upon targeted integration of the gene coding fragment of the marker gene to capture a promoter located in the chromosomal site (see Figure 3a–b). On the other hand, if the donor DNA contains a functional selection marker gene (SMG), the vast majority of the transformants show random integrations, unless a negative‐selection strategy, in combination with positive selection, is employed for excluding random integrations. Ebinuma and colleagues have effectively used this strategy to isolate RMCE events using R‐RS system in tobacco (Ebinuma et al., 2015; Nanto et al., 2005). The importance of SSI selection in Cre‐lox‐mediated site‐specific integration was revealed in a study on rice that utilized a donor DNA capable of producing selectable clones regardless of site‐specific integration as it contained a functional SMG. Only 1 SSI event in >200 transformants was obtained, and nearly all selected clones contained random integrations (Srivastava et al., unpublished data). The use of promoter or gene trap approach, however, greatly enhances the SSI recovery as demonstrated in the studies on Cre‐lox‐ and FLP‐FRT‐mediated plant transformations. Plant transformation efficiencies utilizing the promoter‐trap approach to generate SSI by Cre‐lox or FLP‐FRT are similar to the transformation efficiencies observed in the nontargeted approaches. Site‐specific integrations in rice are recovered at 1–4 events per bombarded plate with Cre‐lox, and at 0.3–0.7 events per bombarded plate with FLP‐FRT, which are similar to the reported efficiencies of rice transformation (Nandy and Srivastava, 2011; Srivastava et al., 2004). Li et al. (2009) reported high RMCE rate by FLP‐FRT in soya bean that ranged from 0.5 to 1 event per bombarded plate. Ebinuma et al. (2015) used negative selection to isolate SSI events over random integrations and recovered SSI at the rates similar to standard transformation efficiencies in tobacco. These studies either involved promoter trapping during site‐specific insertion of the donor DNA or negative selection to suppress non‐RMCE events. The resulting SSI structure, in case of promoter trapping, contains 34‐bp lox or FRT site between the promoter and the gene ORF, indicating that the presence of these recombination sites in the leader sequence of SMG is tolerated during gene expression. While promoter trapping is a popular positive‐selection approach in recombinase‐mediated gene integrations in plants and mammalian cells, it appears to be less critical in recovering SSI events with unidirectional SSR systems. Two recent studies found site‐specific integrations to occur in 9–10% of transformants of Arabidopsis and tobacco by donor constructs containing a functional SMG (De Paepe et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2014). In these studies, serine family recombinases, phiC31 or Bxb1, were used that carryout unidirectional recombination between attP and attB sites. Such high rates of SSI recovery by the donor constructs that are capable of producing selectable clones, regardless of site‐specific integration, indicate feasibility of extending recombinase applications to other species beyond model systems.

Gene expression from site‐specific integration sites

Owing to the precision in the recombination mechanisms underlying site‐specific integrations, gene expression from SSI sites is generally stable in plants through successive generations (Chawla et al., 2006; Day et al., 2000; Nanto et al., 2009). Extensive research done in the past 20 years revealed that single‐copy integrations are important for transgene stability. Integration of full‐length DNA constructs whether containing a single gene or a multigene cassette is the most important criteria in the stability of gene expression from SSI locus as each transcription unit remains intact, and aberrant transcription is avoided. Additionally, gene dosage‐dependent expression has been observed from SSI lines containing allelic gene copies or from an array of genes in the chromosome (Akbudak et al., 2010; Chawla et al., 2006; Nandy and Srivastava, 2012). The presence of random integrations, as expected, frequently causes gene silencing in SSI line, which is mostly reversed upon their segregation of the unwanted gene fragments in the progeny (Chawla et al., 2006). Occasionally, however, irreversible gene silencing could occur due to epigenetic modifications of the SSI site (Day et al., 2000). Overall, site‐specific integration approaches are extremely effective in generating stable transgenic lines that (a) show similar levels of gene expression among independent transgenic events and (b) consistently transmit stable SSI locus to the progeny.

Marker‐free site‐specific integration

Continuous crop improvement would require multiple rounds of transformations to add new genes into the pre‐existing transgene locus. Due to the limited availability of SMGs, their removal and reuse will be an important feature of gene stacking technologies. SMG removal can be achieved by genetic segregation or DNA excision; the latter being more suitable for the targeted integration approaches as donor constructs contain both SMG cassette and genes‐of‐interest. Further, as SMG excision is generally a nonselectable process, high efficiencies to allow rapid recovery of marker‐free plants are desirable. Recombinases have been very successful in SMG excisions in plants and transmitting the marker‐free locus to progeny (Srivastava et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Yau and Stewart, 2013). Additionally, inducible expression of recombinases for controlled SMG excisions led to streamlined approaches of recombinase‐mediated SMG excisions (Gidoni et al., 2008; Hare and Chua, 2002; Wang et al., 2011). SMG excisions and site‐specific gene integrations were first demonstrated by the use of Cre‐lox system (Albert et al., 1995; Dale and Ow, 1991), which has remained until today a popular genomic tool, due to its exceptional efficiency in a number of plant species. However, it is not possible to use a single SSR system for two separate applications (integration followed by excision) in the same cell as the mechanisms to prioritize integration over the excision are currently not available. In the RMCE approach, SMG is exchanged along with the genes‐of‐interest, allowing sequential exchange of one cassette for another without size limitation – in theory. However, the size of the donor cassette and the difficulty in multigene cloning may become technical bottlenecks. One solution is to use mutant recombination sites that do not interact with the wild‐type or other mutant sites, known as heterotypic or heterospecific sites, to sequentially exchange one SMG with the second SMG and the new genes. As only the SMG is exchanged from the SSI locus, new genes are effectively stacked with the previously integrated genes. This strategy was demonstrated by stacking 7 genes through two rounds of FLP‐mediated RMCE in soya bean using 3 heterospecific FRT sites (Li et al., 2010). The heterospecific lox and FRT sites are based on mutations in the 8‐bp spacer sequence (Figure 2a). Due to its short length, only a limited number of strictly heterospecific sites can possibly be generated. However, by adding 1–6 point mutations within the FRT spacer, 8 different heterospecific FRT sites have been developed (Turan et al., 2010) that expand the repertoire of FLP‐FRT toolbox needed for sequential gene stacking. Nevertheless, rounds of RMCE in gene stacking will be limited by the availability of heterospecific sites, and the efficiency of each round will vary based on the reactivity of the FRT mutants. Finally, the transgenic plants would still contain a marker gene that might not be desirable in a breeding line.

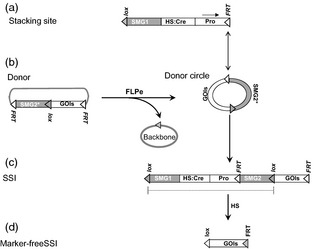

Strategies of marker‐free site‐specific integration (MF‐SSI) were designed long ago (Darbani et al., 2007; Fladung and Becker, 2010; Srivastava and Ow, 2004; Wang et al., 2011), but their experimental demonstration awaited the development of new SSR systems (Figure 4). A combination of Cre‐lox and R‐RS or FLP‐FRT or phiC31 or Bxb1 has been successfully used for developing marker‐free SSI lines of tobacco or rice (De Paepe et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2014; Nandy and Srivastava, 2012; Nanto and Ebinuma, 2008). In these studies, Cre‐lox was dedicated to SMG excision due to its efficiency in allowing the recovery of marker‐free lines without applying selection pressure. Cre activity was either introduced by cross‐fertilization or by inducing through heat treatment for a few hours. Heat‐inducible Cre is emerging as a highly effective tool for producing marker‐free lines in a single generation by heat treatments of regenerated shoots or even tissue culture (Figure 4) (Khattri et al., 2011; Nandy and Srivastava, 2012; Zhang et al., 2003). In summary, streamlined methods for marker‐free site‐specific integrations are available that are foundational for gene stacking technologies.

Figure 4.

Use of two site‐specific recombination systems for developing marker‐free site‐specific integrations in plants. (a) The stacking site in the plant cell contains a construct flanked by loxP and FRT , and designed for promoter (Pro) trapping to select site‐specific integrations, heat‐shock (HS) cre for inducible marker gene excision and a selectable marker gene (SMG1) for selection of the transformed cells. FRT serves as the site of gene integrations. (b) Donor vector contains FRT ‐flanked construct consisting of promoterless marker gene (SMG2*), loxP, and the gene‐of‐interest (GOI). Co‐introduction of the donor vector and FLPe gene results in the formation of a vector‐backbone‐free donor circle, which integrates into the stacking site through FRT x FRT recombination (up down arrow) to generate the selectable site‐specific integration (SSI) structure (c). The SSI structure contains loxP‐flanked SMG and the heat‐inducible cre gene, which can be induced by heat treatment to generate marker‐free SSI structure (d).

Gene stacking by recombinases

Freely reversible or bidirectional SSR systems such as Cre‐lox and FLP‐FRT, in their natural forms, are not fit for gene stacking through serial site‐specific gene integrations as they incorporate two cis‐positioned recombination sites in the integration structure, which will recombine at greater efficiency to revert the SSI structure. Development of heterospecific lox or FRT sites paved the way for gene stacking by allowing exclusive recombination between identical sites without reacting with other spacer mutants or the wild‐type loxP. However, as discussed above, the rounds of transformations, in a gene stacking project, would be restricted by the limited availability of the heterospecific sites. The first generation of heterospecific lox sites contained 1–2 point mutations (Hoess et al., 1986; Lee and Saito, 1998) and showed significant cross‐reactivity with loxP and other mutant lox sites (Feng et al., 1999; Mlynárová et al., 2002), limiting their application in genome engineering. Later, lox mutants containing 3 point mutations were developed (Langer et al., 2002; Missirlis et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2005), some of which are promising in driving exclusive recombination in vivo (Kameyama et al., 2009; Toledo et al., 2006). Heterospecific FRT sites have also been developed (Saito and Saito, 2009; Schlake and Bode, 1994; Turan et al., 2010) that are suitable for stacking multiple genes through serial site‐specific integrations (Baszczynski et al., 2003; Li et al., 2010). In a study on soya bean, three heterospecific FRT sites were used to stack 7 genes through two rounds of transformations; the SSI efficiency in the second round, however, declined sharply (Li et al., 2010). While a number of factors could be associated with the reduced SSI rate in the second round, cross‐reactivity among heterospecific FRT sites and the variable reactivity of each site cannot be ruled out.

Cross‐reactivity in the heterospecific sites would be problematic in gene stacking as recombination among the inserted sites would destabilize the stacked locus. Kamihira and colleagues have developed a clever approach to solve this problem. By combining the spacer and arm mutations in lox sites, they generated a new type of heterospecific lox sites that recombine to form inactive sites in the SSI structure (Kameyama et al., 2009). Lox66 and lox71 mutations represent 5‐bp mutations in the right and left arm of the lox site, respectively (Figure 2c). Heterospecific lox sites containing lox66 or lox71 mutations in their arms would exclusively recombine to generate the double‐mutant (inactive) lox. This approach was used in generating 4 rounds of gene stacking in mammalian cells through Cre‐lox recombination, each resulting in the formation of lox66:lox71 double mutant (lox72), suppressing cross‐reactivity between the inserted lox sites (Obayashi et al., 2012). These studies show how bidirectional SSR systems can be tamed for gene stacking through rounds of site‐specific integrations.

Unidirectional SSR systems are derived from the serine family of recombinases that carryout mechanistically distinct recombination involving nonidentical sites, attP and attB, to produce hybrid sites, attL and attR (Figure 2c). By sequentially adding attP or attB sites into the SSI locus, unlimited rounds of gene stacking could potentially be done (Ow, 2007, 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Yau et al., 2011), resulting in the incorporation of attL or attR in the SSI locus. Further, as plant cells are expected to lack the helper protein (excisionase) required for attL x attR recombination, reversal of SSI is not a concern. In a recent study, Ow and co‐workers have used this principle to stack 3 genes in tobacco through two rounds of Bxb1‐mediated attP x attB recombination into the predetermined chromosomal site in tobacco (Hou et al., 2014). Remarkably, high rates of site‐specific integrations (10–13% of transformants) were recovered through PCR screening of transformants to distinguish SSI events from the random integration events. As the molecular strategy did not involve promoter trapping, irreversibility of site‐specific integration generated by the unidirectional SSR system was likely an important factor in the high rate of SSI recovery. Further, the efficiency of Bxb1‐mediated gene integration was more or less the same in each round of transformation. Therefore, Bxb1 appears to generate high‐efficiency intermolecular recombination in plants and stable SSI structures.

In another study, Depicker and colleagues used a combination of phiC31‐att and Cre‐lox systems for gene stacking through iterative attP x attB recombination in Arabidopsis (De Paepe et al., 2013). While only one round of transformation was done, and the experimental design could not distinguish which SSR system drove gene integration, the resulting SSI structure contained essential features for iterative gene stacking, loxP and attB sites. This iterative site‐specific integration approach was initially described by Brown and colleagues for assembling large DNA fragments into minichromosomes in chicken cells (Dafhnis‐Calas et al., 2005). Their strategy employed Cre‐lox for DNA integrations, and phiC31 for marker excision for its reuse in the subsequent rounds of transformation.

Although acceptable rates of site‐specific integration, without employing SSI selection strategy, were observed in both phiC31/Cre and Bxb1‐mediated gene integration in plants, it is reasonable to assume that the recovery rate will increase if a selection strategy such as promoter trapping is employed. This might be important for gene stacking in crops that are difficult to transform as the current SSI recovery rates (3–10% of transformants) for model plants would likely translate to 0.1–0.5% overall efficiency in wheat, maize or soya bean and in the elite varieties of many crops. Promoter trapping has been demonstrated to greatly enhance the recovery of SSI events in phiC31‐ or Bxb1‐mediated site‐specific integrations in mammalian cells (Belteki et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2014) and involves incorporation of attR or attL site in the leader sequence of SMG. In plants, however, some conflicting reports on the optimum expression of such fusion constructs were made, raising concern about the efficacy of promoter trapping in selecting SSI through phiC31 and Bxb1 recombination. In a study on barley, the fusion construct containing attR site in the leader sequence of the GUS reporter gene was found to express well (Kapusi et al., 2012), while a similar construct was reported to show weak or no expression in Arabidopsis (Thomson et al., 2010, 2012). Clearly, the presence of attR or attL in the leader sequence of genes is not inhibitory to their expression, and careful construct designing and use of short att sequences will be important.

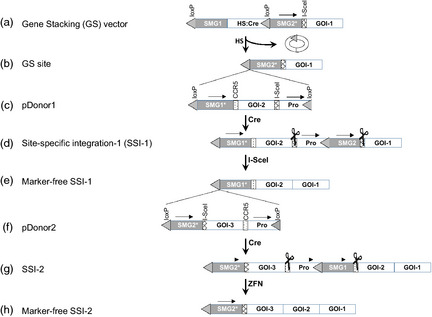

Gene stacking by Cre‐lox recombination

While the work on serine recombinases is relatively new, their efficiencies in heterologous systems appear to be lower than that of Cre‐lox. Cre is generally the recombinase of choice for complex genome engineering in mice (Branda and Dymecki, 2004; Schnütgen et al., 2006). It is therefore desirable to develop gene stacking approaches using this widely utilized robust SSR system. As discussed above, high rates of site‐specific integration are recovered in plants by Cre‐mediated recombination. Gene stacking through RMCE between heterospecific lox or FRT sites can be done to add new genes and swap SMG; however, availability of heterospecific sites will limit the rounds of gene stacking. Srivastava and colleagues developed a novel approach for gene stacking that involves Cre‐mediated site‐specific integration followed by nuclease‐mediated SMG excision (Figure 5a–d; Srivastava, unpublished). Nucleases such as rare‐cutting I‐SceI or designed ZFN could be used in this strategy. Along the marker gene, one of the two cis‐positioned lox sites is deleted (Figure 5e), leaving the second lox for subsequent site‐specific integration (Figure 5f–h). Through these steps of gene integration and marker excision, potentially unlimited rounds of transformations can be done to stack genes into the selected chromosomal site. The concomitant DSBs around SMG can be repaired by either NHEJ or intrachromosomal homologous recombination (HR), if DNA homologies are provided on each end (Swoboda et al., 1994). Although NHEJ could generate unpredictably repaired site, a number of studies indicate that in the majority of clones only short indels are incorporated at the cut ends (Antunes et al., 2012; Petolino et al., 2010; Nandy and Srivastava, unpublished data). Further, inducible expression of nucleases such as I‐SceI or PB1 is also effective in generating DNA excision (Antunes et al., 2012; Ayar et al., 2013), and the majority of repaired clones either contain no loss of DNA or a short indel (1–20 bp) (Lloyd et al., 2012). Therefore, nucleases could serve as alternative tools for marker excision (Lee et al., 2010; Siebert and Puchta, 2002; Yau and Stewart, 2013), and inducible expression could be used to streamline the process. By placing the inducible nuclease gene in the donor construct, marker excision could be accomplished in the SSI clones without genetic crosses. Therefore, marker excision step could easily follow the site‐specific integration step and the whole process completed in the tissue culture phase or a single generation of the plant.

Figure 5.

Gene stacking by Cre‐lox. (a) The gene stacking ( GS ) site contains gene(s)‐of‐interest (GOI‐1), the nuclease site (I‐SceI site), promoterless marker gene ( NPT*) and loxP. Arrows above blocks indicate transcriptional orientation. To develop GS cell lines, a self‐excising fragment consisting of selectable marker gene (SMG1) and heat‐shock (HS) cre is located between loxP sites (grey triangles). (b) Heat‐shock treatment of the cells results in the excision of the fragment between loxP, leaving the GS site at the chromosome. (c) The structure of pDonor1 that contains loxP‐flanked construct consisting of promoter (Pro) positioned to drive SMG2 transcription upon integration into the GS site, I‐SceI site, GOI‐2, the second nuclease site ( CCR5) and the first marker gene (recycling SMG1*). (d) Delivery of pDonor1 with cre gene results in the formation of site‐specific integration (SSI‐1) that is selectable due to SMG2 expression, contains a stack of GOI‐1 and GOI‐2, and I‐SceI sites (scissors) flanking the SMG2 gene. (e) Introduction of I‐SceI activity generates marker‐free SSI‐1, which contains the GS site (loxP‐ SMG1*) for the next round of gene stacking. (f) The structure of pDonor2 that contains GOI‐3, and SMG2 is similar to pDonor1 except that the positions of the two nuclease sites are swapped. (g) Delivery of pDonor2 with the cre gene results in the formation of SSI‐2 that is selectable due to SMG1 expression, and contains three GOIs, and CCR5 sites flanking SMG1. (h) Introduction of CCR5‐ZFN activity leads to the excision of marker gene, and formation of an array of GOIs. Thus, the use of the two donor vectors and two nucleases enables potentially unlimited rounds of gene stacking.

Prospects

Plant transformation techniques are integral parts of gene stacking technology, the efficiency of which greatly varies between plant species and plant varieties. Therefore, wide acceptance of gene stacking technologies will depend on whether plant transformation efficiencies are maintained to a practical level. Two distinct technologies are now available that enable gene stacking, synthetic or natural nucleases to induce DNA insertion into DSB, and recombinases to insert DNA via site‐specific recombination. While nucleases can be designed to cut the native genomic sequences, recombinases would require placement of the recombination site first. However, gene stacking via nucleases requires redesign of each and every construct while recombinase strategies allow recycling of existing constructs with high‐efficiency targeting. As the nuclease technology is expanding, the recombinase toolbox is also getting richer with many new recombinases being isolated and functionally validated in eukaryotic cells (Gaj et al., 2014; Thomson and Ow, 2006; Table 1). Their real‐world application will mostly depend on their efficiency and fidelity. Recombinases are highly specific to their target sites. The rare pseudo‐sites that may be present in a plant genome would be expected to have lower affinity to the recombinase (Thyagarajan et al., 2000), limiting trans recombination with such pseudo‐sites during gene stacking. More importantly, strong recombinase expression is mostly tolerated in plants, suggesting minimal or rare recombination between pseudo‐sites (Ream et al., 2005; Rubtsova et al., 2008; Srivastava and Ow, 2001; Srivastava et al., 1999). Further, as backcrossing is a standard practice in plant breeding, if genetic alterations were produced, they could be segregated in the progeny. Cre is considered the most efficient recombinase and therefore preferred for complex genome engineering. Improved FLP recombinase, FLPe, and Bxb1 serve as other efficient recombinases and found to be suitable for gene stacking. A number of other recombinases have also shown promise in plant genome engineering. It is noteworthy that most of the recombinases have been used in their native form, except for the addition of nuclear localization signal in the large serine recombinases to facilitate entry of these large proteins into nucleus. Thus, the prospects of further improving them are bright, for example by codon optimization or mutagenesis. Recombinases are undoubtedly capable of complex genome engineering, including gene stacking; a more important issue is where to stack the genes? Over 20 years of research on transgenic plants indicates there are many ‘safe harbours’ in the plant genomes that support the stability of transgene through generations without imposing undesirable phenotypic effects. Alternatively, transgenes could be segregated from the main genome by placing them on minichromosomes (Birchler, 2014). In any case, targeted insertions will be needed to repeatedly direct the genes into the dedicated sites. The efficiency, fidelity and precision of a number of recombinases make them highly attractive for gene stacking. Designer nucleases could be used to place the recombination sites in the chosen chromosomal sites or minichromosome for practicing gene stacking by a more efficient approach such as recombinases. Finally, some of the recombinases, including Cre‐lox and Bxb1, have the freedom‐to‐operate, and therefore, the products developed by their use will not be impacted by the burden of intellectual property issues. By virtue of their robust activity and high specificity, combined with minimal/undetectable toxicity in plant cells, these recombinases are unparalleled tools for gene stacking whether it is used for developing the prototypes or the commercial products.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by USDA‐NIFA‐BRAP grant #2010‐33522‐21715 and Arkansas Bioscience Institute‐Division of Agriculture grant to VS, and USDA‐ARS project 5325‐21000‐020‐00D to JT. We are grateful to David Ow, Hiroyasu Ebinuma, Matthias Fladung and Frank Yau for useful discussions. A patent has been filed by the University of Arkansas on the technology described in Figure 5.

References

- Ainley, W.M. , Sastry‐Dent, L. , Welter, M.E. , Murray, M.G. , Zeitler, B. , Amora, R. , Corbin, D.R. , Miles, R.R. , Arnold, N.L. , Strange, T.L. , Simpson, M.A. , Cao, Z. , Carroll, C. , Pawelczak, K.S. , Blue, R. , West, K. , Rowland, L.M. , Perkins, D. , Samuel, P. , Dewes, C.M. , Shen, L. , Sriram, S. , Evans, S.L. , Rebar, E.J. , Zhang, L. , Gregory, P.D. , Urnov, F.D. , Webb, S.R. and Petolino, J.F. (2013) Trait stacking via targeted genome editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 11, 1126–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbudak, M.A. and Srivastava, V. (2011) Improved FLP recombinase, FLPe, efficiently removes marker gene from transgene locus developed by Cre‐lox mediated site‐specific gene integration in rice. Mol. Biotech. 49, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbudak, M.A. , More, A.B. , Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2010) Dosage‐dependent gene expression from direct repeat locus in rice developed by site‐specific gene integration. Mol. Biotech. 45, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert, H. , Dale, E.C. , Lee, E. and Ow, D.W. (1995) Site‐specific integration of DNA into wild‐type and mutant lox sites placed in the plant genome. Plant J. 7, 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, M.S. , Smith, J.J. , Jantz, D. and Medford, J.I. (2012) Targeted DNA excision in Arabidopsis by a re‐engineered homing endonuclease. BMC Biotech. 12, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki, K. , Araki, M. and Yamamura, K. (1997) Targeted integration of DNA using mutant lox sites in embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 868–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki, K. , Okada, Y. , Araki, M. and Yamamura, K. (2010) Comparative analysis of right element mutant lox sites on recombination efficiency in embryonic stem cells. BMC Biotechnol. 10, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayar, A. , Wehrkamp‐Richter, S. , Laffaire, J.B. , Le Goff, S. , Levy, J. , Chaignon, S. , Salmi, H. , Lepicard, A. , Sallaud, C. , Gallego, M.E. , White, C.I. and Paul, W. (2013) Gene targeting in maize by somatic ectopic recombination. Plant Biotechnol. J. 11, 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baszczynski, C.L. , Gordon‐ Kamm, W.J. , Lyznik, L.A. , Peterson, D.J. and Zhao, Z.Y. (2003) Site‐specific recombination systems and their uses for targeted gene manipulation in plant systems. In Transgenic Plants: Current Innovations and Future Trends ( Neal Stewart, C. , ed.), pp. 157–178. Norfolk, England: Horizon Scientific Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belteki, G. , Gertsenstein, M. , Ow, D.W. and Nagy, A. (2003) Site‐specific cassette exchange and germline transmission with mouse ES cells expressing phiC31 integrase. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler, J.A. (2014) Engineered minichromosomes in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 19, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira, E.E. , Westerman, K. and Leboulch, P. (1997) Transcriptional behavior of LCR enhancer elements integrated at the same chromosomal locus by recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange. Blood, 90, 3332–3344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branda, C.S. and Dymecki, S.M. (2004) Talking about a revolution: the impact of site‐specific recombinases on genetic analyses in mice. Dev. Cell 6, 7–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, F. , Angrand, P.O. and Stewart, A.F. (1998) Improved properties of FLP recombinase evolved by cycling mutagenesis. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, R. , Ariza‐Nieto, M. , Wilson, A.J. , Moore, S.K. and Srivastava, V. (2006) Transgene expression produced by biolistic‐mediated, site‐specific gene integration is consistently inherited by the subsequent generations. Plant Biotechnol. J. 4, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, M.D. and Que, Q. (2003) Targeted integration of T‐DNA into the tobacco genome at double‐stranded breaks: new insights on the mechanism of T‐DNA integration. Plant Physiol. 133, 956–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, M.‐D. , Deframond, A. , Que, Q. and Suttie, J.L. (2002) Lambda integrase mediated recombination in plants. Patent applic. No. PCT/US2003/010124, publ. no. WO2003083045 A3.

- Christ, N. and Droge, P. (2002) Genetic manipulation of mouse embryonic stem cells by mutant lambda integrase. Genesis, 32, 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , Houben, A. and Segal, D. (2008) Extrachromosomal circular DNA derived from tandemly repeated genomic sequences in plants. Plant J. 53, 1027–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneille, S. , Lutz, K.A. , Azhagiri, A.K. and Maliga, P. (2003) Identification of functional lox sites in the plastid genome. Plant J. 35, 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafhnis‐Calas, F. , Xu, Z. , Haines, S. , Malla, S.K. , Smith, M.C. and Brown, W.R. (2005) Iterative in vivo assembly of large and complex transgenes by combining the activities of phiC31 integrase and Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, E.C. and Ow, D.W. (1991) Gene transfer with subsequent removal of the selection gene from the host genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 10558–10562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbani, B. , Eimanifar, A. , Stewart, C.N. Jr and Camargo, W.N. (2007) Methods to produce marker‐free transgenic plants. Biotechnol. J. 2, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.D. , Lee, E. , Kobayashi, J. , Holappa, L.D. , Albert, H. and Ow, D.W. (2000) Transgene integration into the same chromosome location can produce alleles that express at a predictable level, or alleles that are differentially silenced. Genes Dev. 14, 2869–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Buck, S. , Peck, I. , De Wilde, C. , Marjanac, G. , Nolf, J. , De Paepe, A. and Depicker, A. (2007) Generation of single‐copy T‐DNA transformants in Arabidopsis by the CRE/loxP recombination‐mediated resolution system. Plant Physiol. 145, 1171–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe, A. , De Buck, S. , Nolf, J. , Van Lerberge, E. and Depicker, A. (2013) Site‐specific T‐DNA integration in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by the combined action of CRE recombinase and ϕC31 integrase. Plant J. 75, 172–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, V. , Servert, P. , Prieto, I. , Gonzalez, M.A. , Martinez, A.C. , Alonso, J.C. and Bernad, A. (2001) New insights into host factor requirements for prokaryotic beta‐recombinase‐mediated reactions in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16257–16264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebinuma, H. , Nakahama, K. and Nanto, K. (2015) Enrichments of gene replacement events by Agrobacterium‐mediated recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange. Mol. Breed. 35, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.Q. , Seibler, J. , Alami, R. , Eisen, A. , Westerman, K.A. , Leboulch, P. and Bouhassira, E.E. (1999) Site‐specific chromosomal integration in mammalian cells: highly efficient CRE recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fladung, M. and Becker, D. (2010) Targeted integration and removal of transgenes in hybrid aspen (Populus tremula L. x P. tremuloides Michx.) using site‐specific recombination systems. Plant Biol (Stuttg). 12, 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaj, T. , Sirk, S.J. and Barbas, C.F. 3rd . (2014) Expanding the scope of site‐specific recombinases for genetic and metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 111, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin, S.B. (2012) Traversing the cell: Agrobacterium T‐DNA's journey to the host genome. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, P. , Wasil, L.R. and Hatfull, G.F. (2006) Control of Phage Bxb1 Excision by a Novel Recombination Directionality Factor. PLoS Biol. 4, e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidoni, D. , Srivastava, V. and Carmi, N. (2008) Site‐specific excisional recombination strategies for elimination of undesirable transgenes from crop plants. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 44, 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Golic, K.G. and Lindquist, S. (1989) The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site‐specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell, 59, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, P. , Lotan, O. , Kolot, M. , Maslenin, L. , Bendov, R. , Gorovits, R. , Yesodi, V. , Yagil, E. and Rosner, A. (2005) Site‐specific recombination in Arabidopsis plants promoted by the Integrase protein of coliphage HK022. Plant Mol. Biol. 57, 435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindley, N.D. , Whiteson, K.L. and Rice, P.A. (2006) Mechanisms of site specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 567–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F. , Gopaul, D.N. and van Duyne, G.D. (1997) Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site‐specific recombination synapse. Nature, 389, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare, P.D. and Chua, N.H. (2002) Excision of selectable marker genes from transgenic plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoess, R.H. , Wierzbicki, A. and Abremski, K. (1986) The role of the loxP spacer region in P1 site‐specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 2287–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L. , Yau, Y.Y. , Wei, J. , Han, Z. , Dong, Z. and Ow, D.W. (2014) An open source system for in planta gene stacking by Bxb1 and Cre recombinases. Mol. Plant 7, 1756–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.C. , Wood, E.A. and Cox, M.M. (1991) A bacterial model system for chromosomal targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama, Y. , Kawabe, Y. , Ito, A. and Kamihira, M. (2009) An accumulative site‐specific gene integration system using Cre Recombinase‐Mediated Cassette Exchange. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 105, 1106–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusi, E. , Kempe, K. , Rubtsova, M. , Kumlehn, J. and Gils, M. (2012) phiC31 integrase‐mediated site‐specific recombination in barley. PLoS ONE 7, e45353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keweshan, R.S. , Head, G.P. and Gassmann, A.J. (2015) Effects of pyramided bt corn and blended refuges on Western Corn Rootworm and Northern Corn Rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 108, 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattri, A. , Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2011) Heat‐inducible Cre‐lox system for marker excision in transgenic rice. J. Biosci. 36, 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, S.J. , Ghafoori, A.P. , Byrd, M. and Leinwand, L. (2002) A genetic screen identifies novel non‐compatible loxP sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3067–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. and Saito, I. (1998) Role of nucleotide sequences of loxP spacer region in Cre‐mediated recombination. Gene 216, 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J. , Kim, E. and Kim, J.S. (2010) Site‐specific DNA excision via engineered zinc finger nucleases. Trends Biotechnol. 28, 445–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Xing, A. , Moon, B.P. , McCardell, R.P. , Mills, K. and Falco, S.C. (2009) Site‐specific integration of transgenes in soybean via recombinase‐mediated DNA cassette exchange. Plant Physiol. 151, 1087–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Moon, B.P. , Xing, A. , Liu, Z.B. , McCardell, R.P. , Damude, H.G. and Falco, S.C. (2010) Stacking multiple transgenes at a selected genomic site via repeated recombinase‐mediated DNA cassette exchanges. Plant Physiol. 154, 622–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A.H. , Wang, D. and Timmis, J.N. (2012) Single molecule PCR reveals similar patterns of non‐homologous DSB repair in tobacco and Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 7, e32255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwerse, J.D. , van Lier, M.C. , van der Steen, D.M. , de Vlaam, C.M. , Hooykaas, P.J. and Vergunst, A.C. (2007) Stable recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange in Arabidopsis using Agrobacterium tumefaciens . Plant Physiol. 145, 1282–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyznik, L.A. , Rao, K.V. and Hodges, T.K. (1996) FLP‐mediated recombination of FRT sites in the maize genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 3784–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack, A. , Sauer, B. , Abremski, K. and Hoess, R. (1992) Stoichiometry of the Cre recombinase bound to the lox recombining site. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 4451–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missirlis, P.I. , Smailus, D.E. and Holt, R.A. (2006) A high‐throughput screen identifying sequence and promiscuity characteristics of the loxP spacer region in Cre‐mediated recombination. BMC Genom. 7, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynárová, L. , Libantová, J. , Vrba, L. and Nap, J.P. (2002) The promiscuity of heterospecific lox sites increases dramatically in the presence of palindromic DNA. Gene, 296, 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H. , Abercrombie, L. , Eda, S. , Blanvillain, R. , Thomson, J. , Ow, D. and Stewart, C.N. Jr . (2011) Transgene excision in pollen using a codon optimized serine resolvase CinH‐RS2 site‐specific recombination system. Plant Mol. Biol. 75, 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouw, K.W. , Rowland, S.J. , Gajjar, M.M. , Boocock, M.R. , Stark, W.M. and Rice, P.A. (2008) Architecture of a serine recombinase‐DNA regulatory complex. Mol. Cell. 30, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R. and Tester, M. (2008) Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2011) Site‐specific gene integration in rice genome mediated by the FLP‐FRT recombination system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2012) Marker‐free site‐specific gene integration in rice based on the use of two recombination systems. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10, 904–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. and Ebinuma, H. (2008) Marker‐free site‐specific integration plants. Transgenic Res. 17, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. , Yamada‐Watanabe, K. and Ebinuma, H. (2005) Agrobacterium‐mediated RMCE approach for gene replacement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 3, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. , Sato, K. , Katayama, Y. and Ebinuma, H. (2009) Expression of a transgene exchanged by the recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) method in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 28, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navrátilová, A. , Koblížková, A. and Macas, J. (2008) Survey of extrachromosomal circular DNA derived from plant satellite repeats. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi, H. , Kawabe, Y. , Makitsubo, H. , Watanabe, R. , Kameyama, Y. , Huang, S. , Takenouchi, Y. , Ito, A. and Kamihira, M. (2012) Accumulative gene integration into a pre‐determined site using Cre/loxP . J. Biosci. Bioeng. 113, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, E.C. , Hollis, R.P. and Calos, M.P. (2001) Phage R4 integrase mediates site‐specific integration in human cells. Gene, 278, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onouchi, H. , Yokoi, K. , Machida, C. , Matsuzaki, H. , Oshima, Y. , Matsuoka, K. , Nakamura, K. and Machida, Y. (1991) Operation of an efficient site‐specific recombination system of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii in Tobacco cells. Nucleic Acid Res. 19, 6373–6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow, D.W. (2002) Recombinase‐directed plant transformation for the post‐genomic era. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 183–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow, D.W. (2007) GM maize from site‐specific recombination technology, what next? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow, D.W. (2011) Recombinase‐mediated gene stacking as a transformation operating system. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petolino, J.F. , Worden, A. , Curlee, K. , Connell, J. , Strange Moynahan, T.L. , Larsen, C. and Russell, S. (2010) Zinc finger nuclease‐mediated transgene deletion. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta, H. , Dujon, B. and Hohn, B. (1996) Two different but related mechanisms are used in plants for the repair of genomic double‐strand breaks by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5055–5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que, Q. , Chilton, M.D. , de Fontes, C.M. , He, C. , Nuccio, M. , Zhu, T. , Wu, Y. , Chen, J.S. and Shi, L. (2010) Trait stacking in transgenic crops: challenges and opportunities. GM Crops, 1, 220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.S. and Soriano, P. (2007) High‐Efficiency FLP and PhiC31 Site‐Specific Recombination in Mammalian Cells. PLoS ONE, 2, e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream, T.S. , Strobel, J. , Roller, B. , Auger, D.L. , Kato, A. , Halbrook, C. , Peters, E.M. , Theuri, J. , Bauer, M.J. , Addae, P. , Dioh, W. , Staub, J.M. , Gilbertson, L.A. and Birchler, J.A. (2005) A test for ectopic exchange catalyzed by Cre recombinase in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111, 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose, L. , Lounnas, V. , Ehrlich, L. , Buchholz, F. , Wade, R. and Stewart, A.F. (1998) Comparative kinetic analysis of FLP and cre recombinases: mathematical models for DNA binding and recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 284, 363–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsova, M. , Kempe, K. , Gils, A. , Ismagul, A. , Weyen, J. and Gils, M. (2008) Expression of active Streptomyces phage phiC31 integrase in transgenic wheat plants. Plant Cell Rep. 27, 1821–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.H. , Hoopes, J.L. and Odell, J.T. (1992) Directed excision of a transgene from the plant genome. Mol. Gen. Genet. 234, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, I. and Saito, Y. (2009) DNA containing variant FRT sequences. Patent no US 7476539 B2.

- Sauer, B. (1994) Site‐specific recombination: developments and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 5, 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, B. (2002) Cre/lox: one more step in the taming of the genome. Endocrine, 19, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, B. and Henderson, N. (1990) Targeted insertion of exogenous DNA into the eukaryotic chromosome by the cre recombinase. New Biol. 2, 441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlake, T. and Bode, J. (1994) Use of mutated FLP recognition target (FRT) sites for the exchange of expression cassettes at defined chromosomal loci. Biochemistry, 33, 12746–12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnütgen, F. , Stewart, A.F. , von Melchner, H. and Anastassiadis, K. (2006) Engineering embryonic stem cells with recombinase systems. Methods Enzymol. 420, 100–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwikardi, M. and Droge, P. (2000) Site‐specific recombination in mammalian cells catalyzed by gammadelta resolvase mutants: implications for the topology of episomal DNA. FEBS Lett. 471, 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, R. and Puchta, H. (2002) Efficient repair of genomic double‐strand breaks by homologous recombination between directly repeated sequences in the plant genome. Plant Cell, 14, 1121–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Gidoni, D. (2010) Site‐specific gene integration technologies for crop improvement. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 46, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Ow, D.W. (2001) Single‐copy primary transformants of maize obtained through the co‐introduction of a recombinase‐expressing construct. Plant Mol. Biol. 46, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Ow, D.W. (2004) Marker‐free site‐specific gene integration in plants. Trends Biotechnol. 22, 627–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Ow, D. (2010) Site‐specific recombination for precise and clean transgene integration in plant genome. In Plant Transformation Technologies ( Neal Stewart Jr, C. , Touraev, A. , Citovsky, V. and Tzfira, T. , eds), pp. 197–209. W. Sussex, England: Blackwell publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Ow, D.W. (2015) Simplifying transgene locus structure through Cre‐lox recombination. In Plant Gene Silencing, Methods in Molecular Biology ( Mysore, K.S. and Senthil‐Kumar, M. , eds), pp. 95–103. New York, USA, Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Anderson, O.D. and Ow, D.W. (1999) Single‐copy transgenic wheat generated through the resolution of complex integration patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11117–11121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Ariza‐Nieto, M. and Wilson, A.J. (2004) Cre‐mediated site‐specific gene integration for consistent transgene expression in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Akbudak, M.A. and Nandy, S. (2011) Marker‐free plant transformation. In Plant Transformation Technology Revolution in Last Three Decades ( Dan, Y. and Ow, D.W. , eds), pp. 108–122. Bentham e‐Books; [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, S. , Ginsburg, D.S. and Calos, M.P. (2002) Phage TP901‐1 site‐specific integrase functions in human cells. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3657–3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer, N.P. , Thompson, G.D. and Head, G.P. (2012) Application of pyramided traits against Lepidoptera in insect resistance management for Bt crops. GM Crops Food, 3, 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita, K. , Kasahara, T. , Matsunaga, E. and Ebinuma, H. (2000) A transformation vector for the production of marker‐free transgenic plants containing a single copy transgene at high frequency. Plant J. 22, 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda, P. , Gal, S. , Hohn, B. and Puchta, H. (1994) Intrachromosomal homologous recombination in whole plants. EMBO J. 13, 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J.G. and Ow, D.W. (2006) Site‐specific recombination systems for the genetic manipulation of eukaryotic genomes. Genesis, 44, 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J.G. , Rucker, E.B. and Piedrahita, J.A. (2003) Mutational analysis of loxP sites for efficient Cre‐mediated insertion into genomic DNA. Genesis, 36, 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J.G. , Yau, Y.Y. , Blanvillain, R. , Chiniquy, D. , Thilmony, R. and Ow, D.W. (2009) ParA resolvase catalyzes site‐specific excision of DNA from the Arabidopsis genome. Transgenic Res. 18, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J.G. , Chan, R. , Thilmony, R. , Yau, Y.Y. and Ow, D.W. (2010) PhiC31 recombination system demonstrates heritable germinal transmission of site‐specific excision from the Arabidopsis genome. BMC Biotechnol. 10, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J.G. , Chan, R. , Smith, J. , Thilmony, R. , Yau, Y.Y. , Wang, Y. and Ow, D.W. (2012) The Bxb1 recombination system demonstrates heritable transmission of site‐specific excision in Arabidopsis. BMC Biotechnol. 12, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, H.M. , Wilson, S.E. and Smith, M.C. (2000) Control of directionality in the site‐specific recombination system of the Streptomyces phage phiC31. Mol. Microbiol. 38, 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan, B. , Guimarães, M.J. , Groth, A.C. and Calos, M.P. (2000) Mammalian genomes contain active recombinase recognition sites. Gene, 244, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan, B. , Olivares, E.C. , Hollis, R.P. , Ginsburg, D.S. and Calos, M.P. (2001) Site‐specific genomic integration in mammalian cells mediated by phage phiC31 integrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3926–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, F. , Liu, C.W. , Lee, C.J. and Wahl, G.F. (2006) RMCE‐ASAP: a gene targeting method for ES and somatic cells to accelerate phenotype analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, S. , Kuehle, J. , Schambach, A. , Baum, C. and Bode, J. (2010) Multiplexing RMCE: versatile extensions of the Flp‐recombinase‐mediated cassette‐exchange technology. J. Mol. Biol. 402, 52–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. , Frankman, L.R. , Vaidya, M. and Citovsky, V. (2003) Site‐specific integration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T‐DNA via double‐stranded intermediates. Plant Physiol. 133, 1011–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergunst, A.C. and Hooykaas, P.J. (1998) Cre/lox‐mediated site‐specific integration of Agrobacterium T‐DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana by transient expression of cre . Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergunst, A.C. , Jansen, L.E. and Hooykaas, P.J. (1998) Site‐specific integration of Agrobacterium T‐DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2729–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Yau, Y.Y. , Perkins‐Balding, D. and Thomson, J.G. (2011) Recombinase technology: applications and possibilities. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 267–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E.T. , Kolman, J.L. , Li, Y.C. , Mesner, L.D. , Hillen, W. , Berens, C. and Wahl, G.M. (2005) Reproducible doxycycline‐inducible transgene expression at specific loci generated by Cre‐recombinase mediated cassette exchange. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Y.Y. and Stewart, C.N. Jr . (2013) Less is more: strategies to remove marker genes from transgenic plants. BMC Biotechnol. 13, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Y.Y. , Wang, Y. , Thomson, J.G. and Ow, D.W. (2011) Method for Bxb1‐mediated site‐specific integration in planta. Methods Mol. Biol. 701, 147–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Subbarao, S. , Addae, P. , Shen, A. , Armstrong, C. , Peschke, V. and Gilbertson, L. (2003) Cre/lox‐mediated marker gene excision in transgenic maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. , Farruggio, A.P. , Bjornson, C.R. , Chavez, C.L. , Geisinger, J.M. , Neal, T.L. , Karow, M. and Calos, M.P. (2014) Recombinase‐mediated reprogramming and dystrophin gene addition in mdx mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS ONE, 9, e96279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]