Abstract

The heteromeric amino acid transporter glycoprotein subunits rBAT and 4F2hc (heavy chains) form, with different catalytic subunits (light chains), functional heterodimers that are covalently stabilized by a disulphide bridge. Whereas rBAT associates with b0,+AT to form the cystine and cationic amino acid transporter defective in cystinuria, 4F2hc associates with other homologous light chains, for instance with LAT1 to form a system L neutral amino acid transporter. To identify within the heavy chains the domain(s) involved in recognition of and functional interaction with partner light chains, chimaeric and truncated forms of rBAT and 4F2hc were co-expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes with b0,+AT or LAT1. Heavy chain–light chain association was analysed by co-immunoprecipitation, and transport function was tested by tracer uptake experiments. The results indicate that the cytoplasmic tail and transmembrane domain of rBAT together play a dominant role in selective functional interaction with b0,+AT, whereas the extracellular domain of rBAT appears to facilitate specifically L-cystine uptake. For 4F2hc, functional interaction with LAT1 was mediated by the N-terminal part, comprising cytoplasmic tail, transmembrane segment and neck, even in the absence of the extracellular domain. Alternatively, functional association with LAT1 was also supported by the extracellular part of 4F2hc comprising neck and glycosidase-like domain linked to the complementary part of rBAT. In conclusion, the cytoplasmic tail and the transmembrane segment together play a determinant role for the functional interaction of rBAT with b0,+AT, whereas either cytoplasmic or extracellular glycosidase-like domains are dispensable for the functional interaction of 4F2hc with LAT1.

Keywords: amino acid influx, amino acid transporter, coimmunoprecipitation, glycoprotein, subunit association, Xenopus laevis oocyte

Abbreviations: 2-ME, 2-mercaptoethanol; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TEA, triethanolamine

INTRODUCTION

Heterodimeric amino acid transporters (for reviews, see [1–6]) are composed of two different subunits, a catalytic subunit called the light chain and a glycoprotein heavy chain. These heterodimers function in the plasma membrane as antiporters, exchanging amino acids.

The heavy-chain subunit is a type II glycoprotein (SLC3A), the extracellular C-terminal domain of which resembles α-amylases and belongs to the glycosyl hydrolase family 13 [7]. This domain is thus expected to be composed of a TIM barrel with a protruding β strand structure and a C-terminal Greek key β-motif [2]. However, no glycosidase activity associated with this domain has been detected so far [8]. Two structurally related heavy chains have been identified, rBAT and 4F2hc, that share 30% identity and 50% similarity [9].

The light chains are non-glycosylated, approx. 500 amino acids long polytopic proteins that resemble other amino acid transporters, have 12 predicted transmembrane segments and intracellular termini. They represent the catalytically active part of the heterodimers, as shown for b0,+AT by reconstitution in liposomes [10]. Correspondingly, the characteristics of the transport mediated by the heterodimers are determined by the light chain that alone, however, does not reach the plasma membrane [11,12]. The light chains identified so far display at least 40% identity with each other, but only one (b0,+AT) is a physiological partner of rBAT, whereas six (LAT1, LAT2, y+LAT1, y+LAT2, asc-1, xCT) functionally associate with 4F2hc.

Under overexpression conditions, 4F2hc was shown to interact also with b0,+AT in mammalian cells and in Xenopus laevis oocytes [13,14] and, conversely, rBAT was co-precipitated with LAT2 when co-expressed in Xenopus oocytes [15]. The association of the two subunits is stabilized by a covalent bond between two highly conserved cysteine residues. In the heavy chains, this cysteine is localized in the extracellular neck, a few amino acids away from the membrane. In the light chains, the interacting cysteine is located in the second putative extracellular loop. The role of this disulphide bond appears to be the stabilization of the subunit interaction, since it has been shown, in overexpression systems, that it is neither necessary for the formation of the heterodimer nor for the expression of its transport function [16].

To identify within the glycoprotein subunits the structural determinants that mediate the recognition of and the functional association with the corresponding light chains, chimaeric and truncated forms of rBAT and 4F2hc were generated and co-expressed with light chains in X. laevis oocytes. Association of these chimaeric and truncated heavy chains with co-expressed light chains and resulting amino acid transport at the cell surface were investigated.

EXPERIMENTAL

cDNAs and constructs

The cDNAs of wild-type h4F2hc, hrBAT and of all chimaeric and truncated constructs were inserted in the pSPORT-1 vector (h4F2hc [17], hrBAT [18]) hLAT1 cDNA was in pcDNA1/Amp-pSP64T [19] and mb0,+AT in pSD5easy [20].

Chimaeric constructs were made using the recombination PCR method [21]. As a first step, the DNA segment that had to be inserted into a recipient construct and the recipient construct itself were amplified from the corresponding templates in two separate amplification reactions. PCR was performed with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Cambridge, U.K.) with the following cycling parameters: 1 min at 94 °C followed by 24 cycles; 30 s at 94 °C; 30 s at optimized annealing temperature; 1 min (for the insert) or 12 min (for the recipient construct) at 72 °C. The final elongation was for 7 (insert) or 15 min (recipient construct) at 72 °C. Primers were designed such that the two blunt-end fragments (insert and recipient vector) had at least 30 identical base-pairs at each end. Primers used are listed in Table 1. Table 2 indicates primers and templates used for the two amplification reactions made for each construct. PCR products were separated from the template by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified with the Qiagen gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, U.K.). Mixtures of purified insert and recipient vector DNA segments (in different ratios) were used to transform Epicurian Coli™ XL1-Blue supercompetent cells (Stratagene). Bacteria mediated the recombination of the linear PCR fragments with homologous ends. Correct recombination was checked by DNA sequencing (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland).

Table 1. Primers used for recombination PCR.

s, sense; as, antisense. In longer primers, a hyphen indicates the limit between the part of the primer complementary with the template and the over-hang (in italic). The overhang sequence is complementary to one shorter primer.

| Primers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Direction | Length (bp) | Sequence |

| 1 | s | 51 | AGGCACTCCGAAGACATAAGTCGGTGAGAC-ATGAGCCAGGACACCGAGGTG |

| 2 | as | 51 | GTAGATCTGGTACATGGGCCCCTCCTGCCA-CCACTTCTGCGCCGGTAGCTC |

| 3 | s | 30 | TGGCAGGAGGGGCCCATGTACCAGATCTAC |

| 4 | as | 30 | GTCTCACCGACTTATGTCTTCGGAGTGCCT |

| 5 | s | 51 | CTGCGTCGTGTCGCCGGTTCTGCAGGCACC-ATGGCTGAAGATAAAAGCAAG |

| 6 | as | 51 | GCCGATGCGGTAGAGGGCGCCCGTGTGCCA-CCAGTCTAGGCACTTTGGAGA |

| 7 | s | 30 | TGGCACACGGGCGCCCTCTACCGCATCGGC |

| 8 | as | 30 | GGTGCCTGCAGAACCGGCGACACGACGCAG |

| 9 | s | 51 | CTGCGTCGTGTCGCCGGTTCTGCAGGCACC-ATGAGCCAGGACACCGAGGTG |

| 10 | as | 51 | CGTGTGCCACCAGTCTAGGCACTTTGGAGA-CACGATTATGACCACGGCACC |

| 11 | s | 30 | TCTCCAAAGTGCCTAGACTGGTGGCACACG |

| 12 | as | 51 | CAGCACAGAAGCCACTGTGAGCCAGAAGAG-GCGGGTGCGTACCCAGCCGGG |

| 13 | s | 30 | CTCTTCTGGCTCACAGTGGCTTCTGTGCTG |

| 14 | s | 57 | AGGCACTCCGAAGACATAAGTCGGTGAGAC-ATGGCTGAAGATAAAAGCAAGAGAGAC |

| 15 | as | 51 | CGCCGGTAGCTCGCGACAACGCGGCGCTCG-GAGGGCAATGATGGCTATGGT |

| 16 | s | 24 | CGAGCGCCGCGTTGTCGCGAGCTA |

| 17 | as | 51 | GCCGAGCCAGAAGAGCAGCAGCAGTGCCCA-GATCTCCCGAGGTATGCGGTA |

| 18 | s | 24 | TGGGCACTGCTGCTGCTCTTCTGG |

Table 2. PCR products used for each heavy-chain construct.

Primers (indicated by numbers, see Table 1) and template used for each PCR are indicated. Recombination of PCR products reported in the same lane resulted in the corresponding construct.

| PCR products | ||

|---|---|---|

| Insert | Recipient vector | Construct |

| 1+2 on h4F2hc-pSPORT | 3+4 on hrBAT-pSPORT | 444B |

| 1+10 on h4F2hc-pSPORT | 4+11 on hrBAT-pSPORT | 44BB |

| 9+10 on 444B-pSPORT | 8+11 on BBB4-pSPORT | 44B4 |

| 9+12 on 444B-pSPORT | 8+13 on BBB4-pSPORT | 4BB4 |

| 5+6 on hrBAT-pSPORT | 7+8 on h4F2hc-pSPORT | BBB4 |

| 5+15 on hrBAT-pSPORT | 8+16 on h4F2hc-pSPORT | BB44 |

| 14+15 on BBB4-pSPORT | 4+16 on 444B-pSPORT | BB4B |

| 14+17 on BBB4-pSPORT | 4+18 on 444B-pSPORT | B44B |

To obtain the truncated forms of 4F2hc (117 and 133 amino acids) and of rBAT (117 amino acids), site-directed mutagenesis was performed to introduce stop codons at the desired positions of the cDNA. Complementary primers with mutated nucleotide(s) at their centre were used to amplify the complete template cDNA plasmid. PCR amplification was performed using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and the following cycling parameters: 30 s at 95 °C; 16 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C; 1 min at 55.2 °C for 4F2hcΔ117, 59.7 °C for 4F2hcΔ133 and 57.5 °C for rBATΔ117; 13 min at 68 °C. Selective DNA template digestion was made with DpnI. Plasmids isolated from transformed bacteria were sequenced to verify the presence of the desired point mutation.

The following sense primers were used (mutated bases underlined, antisense oligonucleotides complementary): 4F2hc Trp118→stop: 5′-GCAGAAGTGGTAGCACACGGGCGCCCTC-3′; 4F2hc Gly134→stop: 5′-CAGGCCTTCCAGTGACACGGCGCGGGCAAC-3′; rBAT Trp118→stop: 5′-AAGTGCCTAGACTGGTAGCAGGAGGGGCCCATG-3′.

cRNA synthesis

Constructs made in pSPORT-1 and pcDNA1/Amp-pSP64T vectors were linearized with HindIII and EcoRV respectively. T7 RNA polymerase, reagents and method for the RNA synthesis reaction were taken from the MEGAscript™ T7 kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.). Linearization of plasmid containing the vector pSD5easy was done with PvuII, and Sp6 RNA polymerase (MEGAscript™ SP6 kit; Ambion) was used for cRNA synthesis. cRNAs were purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). RNA integrity was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and concentration determined by the measurement of absorbance at 260 nm.

Immunoprecipitation, SDS/PAGE and fluorography

cRNAs (10 ng each) of the heavy-chain constructs and/or of the light chain were injected into oocytes that were then incubated at 16 °C in ND96 buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mCi/ml L-[35S]methionine for 2–3 days of expression. After extensive washing with ND96, oocytes were lysed using 20–30 μl of lysis buffer [120 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8) and 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), supplemented with 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and 200 mM PMSF] per oocyte, vortex-mixed for 20 s, incubated briefly on ice and then centrifuged at 16000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Incorporated radioactivity was determined in trichloroacetic acid precipitates.

For immunoprecipitation, rabbit serum anti-human rBAT number 564 (N-terminal epitope MAEDKSKRDSIEMSMKGC) [22] and rabbit serum anti-human LAT1 number 555 (C-terminal TVLCQKLMQVVPQET; amino acids 493–507) were used.

Lysates containing an equal quantity of incorporated labelled L-[35S]methionine were made up to a final volume of 200 μl with lysis buffer, 50 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.02% sodium azide] and 15 μl of serum. Samples were rotated overnight at 4 °C. UltraLink™ Immobilized Protein A (50 μl; Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.) was then added and samples were rotated for two additional hours. Beads were washed six times with 0.5 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer and the bound antigen–antibody complex was eluted in 40 μl of SDS/PAGE loading buffer, by heating at 65 °C for 15 min. Samples were reduced by adding 2.5% (v/v) 2-ME (2-mercaptoethanol) and heating again as above. After migration, gels were stained with Coomassie Blue, treated with Amplify Fluorographic Reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Bucks, U.K.) for 20 min, dried and exposed to Kodak X-OmatAR Film XAR-5 at −80 °C.

Cell-surface biotinylation and streptavidin precipitation

After washing 20 oocytes per reaction 5 times for 5 min in ND96-TEA solution [96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM TEA (triethanolamine) and 5 mM Hepes, pH 8.8], they were incubated for 30 min with biotinylation reagent [Sulpho-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce), 1.5 mg/ml in ND96-TEA buffer]. They were then washed five times in ND96-TEA buffer containing glycine (100 mM) and homogenized in a sucrose-based buffer (4 μl/oocyte) containing 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.9), 1 mM PMSF and 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma) by passing them ten times through a 25-G needle. All steps were performed at 4 °C. After two centrifugation steps at 100 g (4 °C) for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and protein concentration determined by the Bradford assay using Bio-Rad reagents. For Western blot, approx. 50 μg of total protein mixed with SDS/PAGE sample buffer (final concentration 50 mM Tris/Cl, pH 6.8, 2%, w/v, SDS, 10%, v/v, glycerol and 2.5% 2-ME) was loaded on to SDS/10% polyacrylamide gel. For streptavidin precipitation, approx. 500 μg of proteins from biotinylated oocytes were diluted in 1 ml Tris-buffered saline (100 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, and 1% Triton X-100) and 25 μl of streptavidin agarose beads (Immunopure; Pierce) were added. Samples were rolled at 4 °C overnight. Beads were then washed once with buffer A (5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4), twice with buffer B (500 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) and once with buffer C (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) with a 2 min centrifugation (1000 g) between washes. After the final wash, buffer C was replaced with 30 μl of SDS/PAGE sample buffer, the samples were heated at 65 °C for 15 min and run on SDS/10% polyacrylamide gel.

Western blotting

For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred electrophoretically from unstained gels to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). After blocking with 5% (w/v) milk powder in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20 for 60 min, the blots were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse b0,+AT (number 400, 1: 2000) overnight at 4 °C [22]. After washing and subsequent blocking, blots were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (goat anti-rabbit; 1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature (∼22 °C). Antibody binding was detected with the CDP Star kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) and exposure to an X-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.). One out of three similar blots are shown.

Deglycosylation

Lysates of oocytes labelled with L-[35S]methionine were prepared as described above. Lysates containing an equal quantity of incorporated labelled L-[35S]methionine were heated at 65 °C for 15 min in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma), 2.5% 2-ME and 0.33% protease inhibitors cocktail (Sigma). Subsequently, each sample was divided into three equal aliquots and 1 m-unit of endoglycosidase H (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 1 unit of glycopeptidase F (Sigma) or no enzyme was added. The aliquots were incubated overnight at 37 °C, before proceeding with the immunoprecipitation.

Uptake rate of labelled amino acids

cRNAs (10 ng) of the glycoprotein constructs and/or of the light chain were injected into oocytes that were then kept at 16 °C in ND96 buffer for the indicated expression time. Oocytes were washed six times in a Na+-free solution (100 mM choline chloride, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5) and incubated for 2 min at 25 °C, before performing uptakes of 10 min in 100 μl of Na+-free solution containing the amino acid at the indicated concentration and radioactive tracer. For L-[14C]cystine, an excess of diamide (10 mM) was added to the uptake solution to prevent its reduction. When measuring LAT1 function, an excess of unlabelled L-arginine (10 mM) was added to the L-[14C]isoleucine uptake solution to inhibit the potential uptake of L-isoleucine by the endogenous Xenopus b0,+ light chain. Trans-stimulation of L-[14C]isoleucine influx was achieved by the injection of 1 nmol of unlabelled L-phenylalanine (in 33 nl of water) 4–5 h before the uptake measurement [23]. Oocytes were washed after the uptake five times with 3 ml Na+-free solution and then separately lysed by shaking in 250 μl of 2% SDS for 30 min. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry in 3 ml of Emulsifier-Safe™ (Packard Bioscience, Pangbourne, Reading, Berks., U.K.).

Transport rates were calculated as pmol·h−1·oocyte−1. L-[3H]Arginine and L-[14C]cystine transport rates measured with heavy-chain constructs (see Figure 4) were normalized in each experiment to the mean obtained for rBAT (after subtracting the mean of non-injected oocytes). The normalized data from different experiments were pooled. Data given in Figure 6 represent the function of the heavy-chain constructs together with exogenous LAT1. Transport activity of putative endogenous light chains associated with the same heavy-chain construct expressed alone, or background activity of non-injected oocytes for LAT1 (see Figures 6A and 6B) and rBAT-LAT1 (Figure 6A), were subtracted before normalization to the transport rate observed for 4F2hc expressed with LAT1.

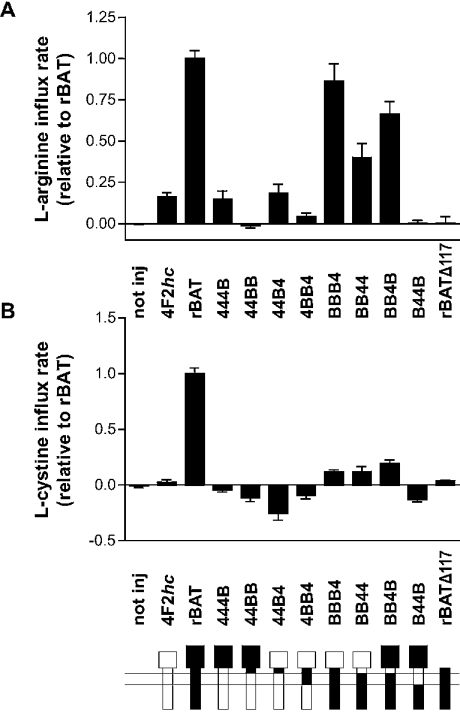

Figure 4. b0,+-like transport activity induced by heavy-chain constructs with endogenous oocyte light chain.

Oocytes were injected with 10 ng of each cRNA, with the exception of rBATΔ117 in (A) where 30 ng was used. After 2–3 days of expression, uptake (10 min in Na+-free solution) of (A) L-[3H]arginine (100 μM) or (B) L-[14C]cystine (50 μM, in the presence of 10 mM diamide) were measured. When compared with the L-arginine transport rate induced by 4F2hc, that induced by BBB4 and BB4B were significantly higher by ANOVA post-test. For L-cystine, the uptake by none of the chimaeras was statistically different from that with 4F2hc according to ANOVA post-tests, whereas the t test analysis was positive for BBB4, BB44 and BB4B.

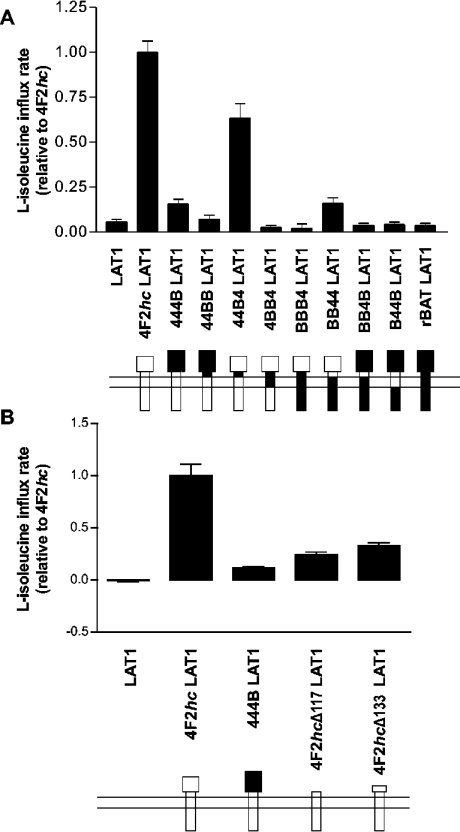

Figure 6. L-type transport activity of LAT1 co-expressed with heavy chain constructs.

Oocytes were injected with 10 ng of the indicated cRNAs. After 1 day of expression (4 days for truncations), uptakes of L-[14C]isoleucine (100 μM) were measured (10 min, in Na+-free buffer supplemented with 10 mM L-arginine to block b0,+AT) after injecting 1 nmol of unlabelled L-phenylalanine for trans-stimulation. Transport rates are given as described in the Experimental section. When compared with the L-isoleucine transport rate induced by LAT1 alone, the rate induced by 44B4 and by both truncations, together with LAT1, was significantly higher according to the ANOVA post-test (Bonferroni), whereas that induced by 444B and BB44 reached a level of significance only according to t test analysis.

Statistics

Error bars indicate the S.E.M. Significance was evaluated using ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test and Student's t test (two-tailed, unpaired).

RESULTS

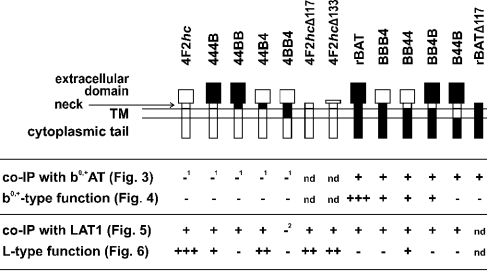

The glycoprotein heavy-chain subunits 4F2hc and rBAT selectively interact with related catalytic light-chain subunits that differ in their amino acid transport selectivity. We have divided the glycoprotein subunits, 4F2hc (529 amino acids) and rBAT (685 amino acids), into four domains, (1) the cytoplasmic N-terminal tail (1–81 in 4F2hc, 1–88 in rBAT), (2) the transmembrane segment (82–104 and 89–110 respectively), (3) the neck (105–117 and 111–117 respectively) and (4) the C-terminal glycosidase-like ectodomain (118–529 and 118–685 respectively) [2,8]. A conserved pair of tryptophan residues at positions 117 and 118 marks, in both glycoproteins, the transition from the neck to the glycosidase-like domain. It is at the level of this short neck that the light chain is covalently attached to the heavy chain by a disulphide bridge [16]. The structure of the heavy-chain chimaeras and deletion constructs used in the present study is schematically represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic drawing of heterodimeric amino acid transporter glycoprotein subunits (heavy chains) constructs and summarized results.

The domains derived from 4F2hc and rBAT are represented as white and filled rectangles respectively. The summary shows that the intracellular and transmembrane domains of the glycoprotein subunits play a central role in determining the selectivity of the functional association with light chain subunits. TM, transmembrane domain; IP, immunoprecipitation; nd, not determined; 1, immunoprecipitation with antibody against b0,+AT 2, low expression level/stability.

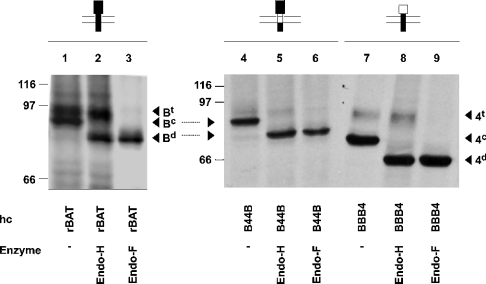

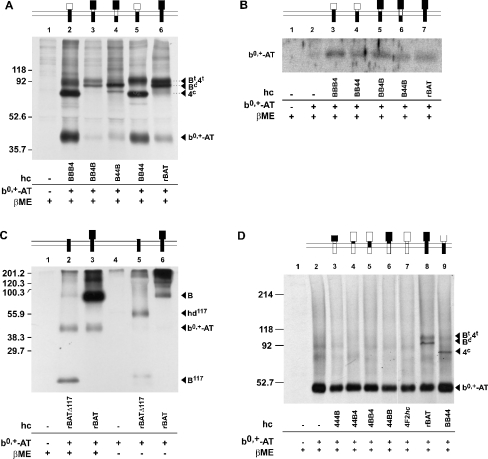

To clarify the nature of the glycosylation pattern of the heavy-chain constructs, we performed deglycosylation experiments using endoglycosidase H (inactive on terminally processed N-glycans) and N-glycosidase F (Figure 2). Untreated rBAT (coexpressed with b0,+AT; lanes 1–3) appeared on SDS/PAGE fluorography as a doublet (lane 1), the lower band of which was shifted to a lower molecular mass by endoglycosidase H treatment (lane 2) and thus corresponds to a core-glycosylated but not terminally glycosylated form. For B44B (co-expressed with b0,+AT; lanes 4–6), the endoglycosidase H-resistant band was quite weak, suggesting that, although B44B has the same glycosidase-like domain as rBAT, the maturation of the construct was somewhat compromised. Lanes 7–9 show a construct (BBB4) that contains the extracellular domain of 4F2hc (co-expressed with b0,+AT). As already known for 4F2hc, the band corresponding to the terminally processed form (endoglycosidase H-resistant) migrates at the same rate as the corresponding band of rBAT, whereas the other forms (core-glycosylated and deglycosylated) migrate relatively faster, as expected from their lower molecular mass. For BBB4, only a relatively small fraction was endoglycosidase H-resistant (lane 8) and thus fully mature.

Figure 2. N-glycosylation pattern of rBAT and the chimaeras B44B and BBB4.

Deglycosylation reactions with endoglycosidase H (Endo-H) and N-glycosidase F (Endo-F) were performed on lysates of oocytes expressing rBAT or the indicated chimaera and that were biosynthetically labelled with L-[35S]methionine. Immunoprecipitation was with anti-rBAT antibody. hc, heavy chain; Bt, terminally glycosylated rBAT; Bc, core-glycosylated rBAT; Bd, deglyco-sylated rBAT; 4t, terminally glycosylated 4F2hc; 4c, core-glycosylated 4F2hc; 4d, deglycosylated 4F2hc. Molecular mass markers (kDa) are shown on the left (in this and subsequent figures).

Covalent interaction of heavy-chain constructs with b0,+AT

In vivo, the catalytic light chain b0,+AT associates with the glycoprotein rBAT but not with 4F2hc. In the small intestine and the proximal kidney tubule, this heterodimeric complex, b0,+AT–rBAT, is localized at the apical side of epithelial cells and mediates the uptake of cationic amino acids and L-cystine. The association of these two proteins has been shown previously in expression systems to be required for their surface expression [11,12]. To investigate the role of the different heavy-chain domains in this association, heavy-chain chimaeras and truncated constructs were co-expressed with b0,+AT in Xenopus oocytes and immuno-precipitated after biosynthetic labelling. Figure 3(A) shows the SDS/PAGE fluorography of an immunoprecipitation performed with an antibody directed against the N-terminus of rBAT. As above in Figure 2, wild-type heavy chain rBAT appeared as a doublet band at 80–90 kDa (Figure 3A, lane 6; Figure 3C, lane 3), the lower band corresponding to the core-glycosylated and the higher to the terminally glycosylated form of the protein [12,24].

Figure 3. Co-immunoprecipitation and cell-surface expression of light-chain subunit b0,+AT and glycoprotein subunit constructs.

Oocytes were injected with the indicated cRNAs and, for (A, C, D), the newly synthesized proteins biosynthetically labelled with L-[35S]methionine. (A, C) Immunoprecipitations of the biosynthetically labelled material using an antibody raised against the N-terminus of rBAT. (B) Western blot of cell-surface proteins with an antibody raised against the light chain b0,+AT. (D) Immunoprecipitation of biosyntethically labelled material using the anti-b0,+AT antibody. SDS/PAGE was performed under reducing conditions where indicated (βME; =2-ME). hc, heavy chain; Bt, rBAT terminally glycosylated; 4t, 4F2hc terminally glycosylated; Bc, rBAT core glycosylated; 4c, 4F2hc core glycosylated; B, rBAT; hd117, heterodimer of rBATΔ117 and b0,+AT; B117, rBATΔ117.

The chimaera BB4B that has only the neck of 4F2hc showed the same pattern of bands (Figure 3A, lane 3). In both cases, co-precipitated b0,+AT was detected, after reduction of the samples, as a relatively weak 40 kDa band (Figure 3A, lanes 3 and 6). The fact that co-precipitated b0,+AT appeared relative to the glycoprotein subunit as a weak band, may be due to the excess of pre-existing non-labelled endogenous b0,+AT. When considered relative to the associated glycoprotein construct, the intensity of the different b0,+AT bands appears roughly equal. In contrast, the labelling intensity of the different heterodimers was variable, most probably due to their differential activity as L-[35S]methionine transporter, and stability.

For B44B (transmembrane + neck segments of 4F2hc, Figure 3A, lane 4), the main band was at the level of the core-glycosylated rBAT, whereas the band at the level of the terminally glycosylated form was quite weak. A lower and much thinner band visible below the core-glycosylated form corresponded probably to the unglycosylated form of the protein (predicted molecular mass of 78.8 kDa) that migrates at the level of the band observed after N-glycosidase F treatment (see Figure 2). This pattern suggests that B44B was mostly correctly inserted in the membrane but was to a large extent retained in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) or not correctly glycosylated in the Golgi apparatus. A band corresponding to co-precipitated b0,+AT indicates that an interaction with the light chain took place (Figure 3A, lane 4).

Co-precipitation of b0,+AT was also observed with both chimaeras that contain the extracellular domain of 4F2hc, BBB4 and BB44 (Figure 3A, lane 2 and 5). The two constructs have a predicted molecular mass that is similar to that of 4F2hc and thus the terminally glycosylated form is expected to migrate at approximately the same level as mature rBAT, whereas the stronger bands of approx. 70 kDa represent a core-glycosylated form (see Figure 2). A confusing factor for the interpretation of the bands is that b0,+AT forms, probably by dimerization, a second weaker band that migrates just below the terminally glycosylated form of the heavy chains.

To address the question of how much b0,+AT reaches the surface when associated with these different glycoprotein constructs, we performed cell-surface biotinylations followed by precipitation of the surface labelled proteins using streptavidin beads. The Western blot performed on the total oocyte lysates revealed that there were similar total amounts of b0,+AT in the different samples (results not shown). Interestingly, the Western blots on streptavidin-precipitated cell-surface proteins revealed the presence of roughly similar amounts of cell-surface-expressed b0,+AT, whichever construct containing the intracellular part of rBAT was co-expressed (Figure 3B).

For oocytes co-expressing the truncation rBATΔ117 and b0,+AT, the truncated protein alone and a heterodimer with b0,+AT (60 kDa) were visible under non-reducing conditions (Figure 3C, lane 5). The reducing treatment disrupted the heterodimer, leading to the appearance of b0,+AT and to an increase in the amount of non-bound rBATΔ117 (Figure 3C, lane 2). None of the chimaeric constructs containing the intracellular tail of 4F2hc associated with b0,+AT, as shown by co-immunoprecipitations made with anti b0,+AT antibody (Figure 3D).

In conclusion, all constructs containing the intracellular domain of rBAT interacted at least to some extent with b0,+AT. However, only the continuity of the intracellular tail and the transmembrane segment of rBAT were compatible with an efficient terminal glycosylation, irrespective of the combination of neck and glycosidase-like ectodomain.

Functional association of heavy-chain constructs with b0,+AT

The b0,+AT catalytic subunit that is normally associated with rBAT mediates the high-affinity uptake of cationic amino acids and L-cystine in exchange for neutral amino acids, whereas the catalytic subunit y+LAT1 that is normally associated with 4F2hc exchanges preferentially intracellular cationic amino acids against extracellular neutral amino acids and Na+. Xenopus oocytes express endogenously a b0,+AT-like and, to a lesser extent, a y+LAT-like light chain that might both interact with heavy-chain chimaeras [14]. First, the induction of L-[3H]arginine uptake by the chimaeras was compared with that induced by rBAT (associating with endogenous b0,+AT) and 4F2hc (associating with endogenous y+LAT). As shown in Figure 4(A), three constructs induced an L-[3H]arginine influx rate that appeared to be clearly higher than that induced by 4F2hc alone. A small L-arginine uptake above background (non-injected oocytes) was detected also for 444B (only glycosidase-like domain from rBAT) and 44B4 (only neck from rBAT), but the transport activity was of the same order of magnitude as that induced by 4F2hc that is known to associate with endogenous y+LAT. However, no transport was induced by 44BB, 4BB4 and B44B (see below). To discriminate further between transport mediated by endogenous b0,+AT or y+LAT, the uptake of L-[14C]cystine, a substrate of b0,+AT excluded by y+LAT, was tested. A small L-[14C]cystine uptake (not significant by ANOVA post-test) was observed for BBB4, BB44 and BB4B expressing oocytes (Figure 4B) that was, however, clearly lower than that measured for L-[3H]arginine. Together, the L-[3H]arginine and L-[14C]cystine uptake results indicate that the three heavy-chain chimaeras that contain the cytoplasmic tail and the transmembrane domain of rBAT associate functionally with (endogenous) b0,+AT.

Truncation rBATΔ117 was also investigated for its possible functional association with endogenous b0,+AT. Despite several attempts with various amounts of cRNA and expression times, no significant influx of L-[3H]arginine, L-[14C]cystine or L-[3H]leucine could be observed.

Covalent interaction of heavy-chain constructs with LAT1

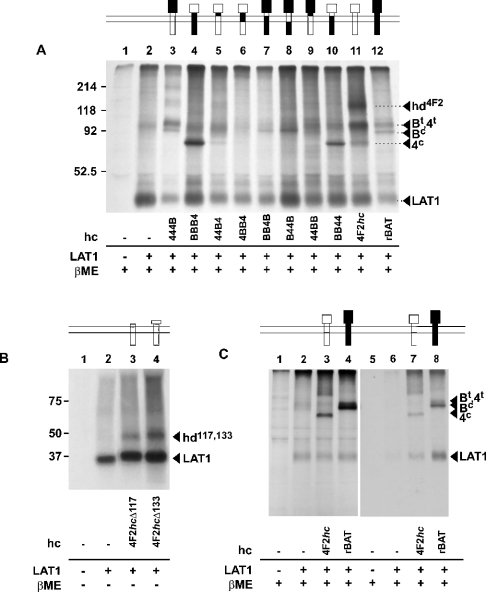

Figure 5 shows the SDS/PAGE (reducing conditions) fluorographies of immunoprecipitations of LAT1 co-expressed with different heavy-chain constructs. Human LAT1 was detected as an approx. 40 kDa band. Co-precipitated 4F2hc (Figure 5A, lane 11) appeared as two bands that correspond to its mature form (∼90 kDa) and its core-glycosylated form (∼70 kDa) respectively. It has to be mentioned that the relative intensity of these two bands was quite variable between experiments. The additional band visible around 130 kDa corresponds probably to a non-separated heterodimer. Human rBAT is not a physiological partner of LAT1, but it was co-precipitated from oocytes overexpressing both proteins (Figure 5A, lane 12). rBAT showed the typical doublet band, corresponding to the core- and terminally glycosylated forms, as previously seen in expression experiments also with LAT2 [15]. The co-precipitation of terminally glycosylated rBAT with LAT1 indicates that this ‘non-physiological’ heterodimer passes, in Xenopus oocytes, at least in part through the Golgi apparatus and might thus reach the oocyte cell surface.

Figure 5. Co-immunoprecipitation and cell-surface expression of light-chain subunit LAT1 and glycoprotein subunit constructs.

Oocytes were injected with the indicated cRNAs and the newly synthesized proteins biosynthetically labelled with L-[35S]methionine. An antibody against the light chain LAT1 was used for immunoprecipitation. (C) Cell-surface proteins were first labelled with biotin and lanes 2–4 show the immunoprecipitation with anti-LAT1 antibody. This immunoprecipitate was then submitted to streptavindin precipitation to select the cell surface biotinylated proteins (lanes 5–8). SDS/PAGE was performed under reducing conditions where indicated (βME; =2-ME). hc, heavy chain; hd4F2, heterodimer 4F2hc-LAT1; Bt, rBAT terminally glycosylated; 4t, 4F2hc terminally glycosylated; Bc, rBAT core glycosylated; 4c, 4F2hc core glycosylated; hd117 and hd133, heterodimers of LAT1 and 4F2hcΔ117 or 4F2hcΔ133 respectively.

Considering that both wild-type heavy chains can associate with LAT1, it is not surprising that mostly all chimaeras were co-precipitated to some extent with this exogenous light chain. Chimaeras 444B and 44BB that contain the entire glycosidase-like extracellular domain of rBAT appeared on gels as rBAT in two bands, a band corresponding to a core-glycosylated form and a second band corresponding to the terminally glycosylated form (Figure 5A, lanes 3 and 9). In contrast, BB4B and B44B, which beside the extracellular part also have the cytoplasmic domain of rBAT, appeared mostly as relatively weak bands at the level of the core-glycosylated form of rBAT (Figure 5A, lanes 7 and 8). Chimaeras BBB4, 44B4 and BB44 contain the extracellular glycosidase-like part of 4F2hc and showed the same bands as wild-type 4F2hc (Figure 5A, lanes 4, 5 and 10). However, for BBB4 and BB44, the 70 kDa band of the core-glycosylated form was stronger than the approx. 90 kDa band (terminally glycosylated form), suggesting that a substantial part of the heterodimer did not exit the ER.

Immunoprecipitation using antibodies directed against the light chain was also performed on oocytes expressing the truncated 4F2hc together with LAT1 (Figure 5B). 4F2hcΔ117 and 4F2hcΔ133 have a predicted molecular mass of 12 and 14 kDa respectively. Complexes of the truncated 4F2hc and LAT1 were visible as bands of approx. 60 kDa, under non-reducing conditions (Figure 5B, lanes 3 and 4). These bands disappeared after sample reduction (results not shown), indicating the presence of a disulphide bond linking the truncated heavy-chain to the light-chain subunit.

To test whether rBAT when associated with LAT1 reaches the cell surface, we performed cell-surface biotinylation reactions on oocytes expressing LAT1 alone or together with either 4F2hc or rBAT (Figure 5C). Western blotting of the total oocyte lysate showed that similar amounts of LAT1 were expressed in the three cases (Figure 5C, lanes 2–4). Western blotting of the streptavidin-precipitated proteins revealed that LAT1 reached the surface together with core- and terminally glycosylated 4F2hc and, surprisingly, also with rBAT (core- and terminally glycosylated forms) (Figure 5C, lanes 7 and 8).

Functional association of heavy-chain constructs with LAT1

To examine the function of heterodimers of LAT1 formed with chimaeric or truncated heavy chains, transport of L-[14C]isoleucine was measured. To increase this uptake by trans-stimulation, unlabelled L-phenylalanine (1 nmol) was injected into oocytes 4 h before the influx measurement [23]. An excess of unlabelled L-arginine was added to the uptake solution, to inhibit competitively the endogenous b0,+ transport system.

As shown in Figure 6(A), 44B4 strongly increased and 444B and BB44 weakly increased (not significantly by ANOVA post-test) the uptake of L-[14C]isoleucine when co-expressed with LAT1. No L-[14C]isoleucine uptake was measured in oocytes co-expressing rBAT and LAT1. Truncated forms of 4F2hc (4F2hcΔ117 and 4F2hcΔ133) co-expressed with LAT1 induced a significant import of L-[14C]isoleucine at rates slightly higher than the one promoted by 444B, but clearly lower than wild-type 4F2hc (Figure 6B).

DISCUSSION

Intracellular and transmembrane domains of rBAT determine functional interaction with b0,+AT

The co-immunoprecipitation experiments show that association with b0,+AT requires the presence of the intracellular domain of rBAT and that, in contrast, chimaeras lacking the intracellular rBAT tail do not associate with b0,+AT (Figure 3). This shows that the three other domains (transmembrane domain, neck and glycosidase-like domain) are neither necessary nor sufficient for association with b0,+AT. For a surface-expression of functional heteromeric transporter containing b0,+AT, the transmembrane domain of rBAT is necessary in association with its cytoplasmic tail, whereas the construct B44B that lacks this transmembrane domain appears to reach the cell surface with b0,+AT but does not support its function. This suggests that the continuity between rBAT intracellular tail and TM domain is important for permitting the transporting function of the b0,+AT heterodimer. The truncated rBAT that associates with b0,+AT did not induce any detectable b0,+-type transport but substitution of the extracellular domain with that of 4F2hc prevented this loss of function (Figure 4).

Taken together, these results suggest that the cytoplasmic tail of rBAT is required for the association of this glycoprotein subunit to its catalytic subunit b0,+AT, whereas the continuity of the rBAT cytoplasmic tail and transmembrane domains, but not the rBAT extracellular domain that can be replaced by the equivalent domain of 4F2hc, is required for the cell surface transport function of the heterodimers containing b0,+AT.

Other studies on progressive C-terminal truncations of rBAT have suggested a possible role of the C-terminal extracellular domain for the recognition of the light chain b0,+AT [25,26]. However, these contrasting conclusions were based only on transport measurements and did not directly address the question of subunit association and cell-surface expression.

It is interesting that all functional b0,+AT heterodimers containing a chimaeric heavy-chain construct supported the transport of L-cystine proportionally less efficiently compared with that of L-arginine. We do not know why substituting at the level of heavy-chain domains has a selective effect on L-cystine transport. It suggests, however, the possibility that efficient L-cystine transport requires some specific functional co-operation of rBAT with the light chain or between heterodimers. This co-operation would be disrupted by the substitution and would be less important for L-arginine compared with that for L-cystine transport.

In contrast with the observations made in the present study, other authors have measured, on overexpression of exogenous 4F2hc in Xenopus oocytes [14] or 4F2hc and b0,+AT in human retinal pigment epithelial cells [13], some b0,+-type activity. It is thus probable that some physical and functional interaction between 4F2hc and b0,+AT can take place in overexpressing systems, but at a quantitative level below our detection limit in co-immunoprecipitation and transport studies [22]. Whether this led to the surface expression of functional heterodimer or just allowed b0,+AT monomers to escape the ER was not investigated.

Functional interaction of 4F2hc with LAT1 is not limited to a specific domain of 4F2hc

Unlike b0,+AT, the 4F2 light chain LAT1 formed a disulphide bond with either co-expressed wild-type heavy chain in Xenopus oocytes (Figure 5). Therefore it is not surprising that most of the chimaeras were found to associate with LAT1. Although non-physiological, the interaction with rBAT was not unexpected, since Rossier et al. had already shown the co-precipitation of rBAT together with LAT2 co-expressed in Xenopus oocytes [15]. However, no L-type transport activity for rBAT-LAT1 expressing oocytes was detectable. In fact, for surface function of the construct heterodimers, a substantial part of the heavy-chain chimaeras needs to originate from 4F2hc, either from its N-terminal or from its extracellular part (in both cases comprising the neck). The present results are compatible with the seemingly conflicting results published previously by others on 4F2hc–LAT1 interaction [27,28]. Indeed, concerning the structural requirements on the glycoprotein subunit for supporting the amino acid transport function of LAT1, the first publication stressed the importance of the N-terminal part of 4F2hc (truncated construct corresponding to our Δ133), whereas the second showed the role of the extracellular part of 4F2hc (neck and glycosidase-like domain linked to cytoplasmic tail and transmembrane segment of CD69). The sole common part of these two minimal constructs is the extracellular neck that is known to form the S–S bridge with the light chain and is shown here to be interchangeable with that of rBAT. We thus deduce that the interaction of the heavy chain 4F2hc with the light chain LAT1 involves structures at the level of all four domains.

Taken together, the major selective determinants of the rBAT–b0,+AT interaction are localized at the level of the intracellular tail. For a maturation leading to functional surface expression of such heterodimers containing b0,+AT, the continuity of the rBAT tail with its corresponding transmembrane segment is required in the heavy chain. The extracellular domain of rBAT might play a role in facilitating the transport of L-cystine. The selective interaction of the 4F2hc heavy chain with LAT1 that allows the functional surface expression of this heteromeric transporter, requires either the N-terminal part (cytoplasmic tail, transmembrane segment and neck), or the extracellular part (neck and glycosidase-like domain) of 4F2hc. This indicates that selective interactions of the subunits involve all tested intra- and extracellular domains of 4F2hc.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Gasser for the artwork. F.V. was supported by the Swiss NSF grant 31-59141.99 and 02.

References

- 1.Wagner C. A., Lang F., Broer S. Function and structure of heterodimeric amino acid transporters. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1077–C1093. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chillaron J., Roca R., Valencia A., Zorzano A., Palacin M. Heteromeric amino acid transporters: biochemistry, genetics, and physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F995–F1018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.6.F995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deves R., Boyd C. A. Surface antigen CD98(4F2): not a single membrane protein, but a family of proteins with multiple functions. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;173:165–177. doi: 10.1007/s002320001017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verrey F., Jack D. L., Paulsen I. T., Saier M. H., Pfeiffer R. New glycoprotein-associated amino acid transporters. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;172:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s002329900595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verrey F., Closs E. I., Wagner C. A., Palacin M., Endou H., Kanai Y. CATs and HATs: the SLC7 family of amino acid transporters. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2004;447:532–542. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanai Y., Endou H. Heterodimeric amino acid transporters: molecular biology and pathological and pharmacological relevance. Curr. Drug Metab. 2001;2:339–354. doi: 10.2174/1389200013338324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janecek S., Svensson B., Henrissat B. Domain evolution in the alpha-amylase family. J. Mol. Evol. 1997;45:322–331. doi: 10.1007/pl00006236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells R. G., Hediger M. A. Cloning of a rat kidney cDNA that stimulates dibasic and neutral amino acid transport and has sequence similarity to glucosidases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:5596–5600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertran J., Magagnin S., Werner A., Markovich D., Biber J., Testar X., Zorzano A., Kuhn L. C., Palacin M., Murer H. Stimulation of system y+-like amino acid transport by the heavy chain of human 4F2 surface antigen in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:5606–5610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reig N., Chillaron J., Bartoccioni P., Fernandez E., Bendahan A., Zorzano A., Kanner B., Palacin M., Bertran J. The light subunit of system b0,+ is fully functional in the absence of the heavy subunit. EMBO J. 2002;21:4906–4914. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauch C., Verrey F. Apical heterodimeric cystine and cationic amino acid transporter expressed in MDCK cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F181–F189. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00212.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pineda M., Wagner C. A., Broer A., Stehberger P. A., Kaltenbach S., Gelpi J. L., Martin Del Rio R., Zorzano A., Palacin M., Lang F., et al. Cystinuria-specific rBAT(R365W) mutation reveals two translocation pathways in the amino acid transporter rBAT-b0,+AT. Biochem. J. 2004;377:665–674. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajan D. P., Huang W., Kekuda R., George R. L., Wang J., Conway S. J., Devoe L. D., Leibach F. H., Prasad P. D., Ganapathy V. Differential influence of the 4F2 heavy chain and the protein related to b0,+ amino acid transport on substrate affinity of the heteromeric b0,+ amino acid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14331–14335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broer A., Hamprecht B., Broer S. Discrimination of two amino acid transport activities in 4F2 heavy chain-expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem. J. 1998;333:549–554. doi: 10.1042/bj3330549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossier G., Meier C., Bauch C., Summa V., Sordat B., Verrey F., Kuhn L. C. LAT2, a new basolateral 4F2hc/CD98-associated amino acid transporter of kidney and intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34948–34954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeiffer R., Spindler B., Loffing J., Skelly P., Shoemaker C., Verrey F. Functional heterodimeric amino acid transporters lacking cysteine residues involved in disulfide bond. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teixeira S., Di Grandi S., Kuhn L. C. Primary structure of the human 4F2 antigen heavy chain predicts a transmembrane protein with a cytoplasmic NH2 terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:9574–9580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertran J., Werner A., Chillaron J., Nunes V., Biber J., Testar X., Zorzano A., Estivill X., Murer H., Palacin M. Expression cloning of a human renal cDNA that induces high affinity transport of L-cystine shared with dibasic amino acids in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14842–14849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastroberardino L., Spindler B., Pfeiffer R., Skelly P. J., Loffing J., Shoemaker C. B., Verrey F. Amino acid transport by heterodimers of 4F2hc/CD98 and members of a permease family. Nature (London) 1998;395:288–291. doi: 10.1038/26246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puoti A., May A., Rossier B. C., Horisberger J. D. Novel isoforms of the beta and gamma subunits of the Xenopus epithelial Na channel provide information about the amiloride binding site and extracellular sodium sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:5949–5954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones D. H., Winistorfer S. C. Use of polymerase chain reaction for making recombinant constructs. Met. Mol. Biol. Series. 1993;15:241–250. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-244-2:241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer R., Loffing J., Rossier G., Bauch C., Meier C., Eggermann T., Loffing-Cueni D., Kuhn L. C., Verrey F. Luminal heterodimeric amino acid transporter defective in cystinuria. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:4135–4147. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier C., Ristic Z., Klauser S., Verrey F. Activation of system L heterodimeric amino acid exchangers by intracellular substrates. EMBO J. 2002;21:580–589. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chillaron J., Estevez R., Samarzija I., Waldegger S., Testar X., Lang F., Zorzano A., Busch A., Palacin M. An intracellular trafficking defect in type I cystinuria rBAT mutants M467T and M467K. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9543–9549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deora A. B., Ghosh R. N., Tate S. S. Progressive C-terminal deletions of the renal cystine transporter, NBAT, reveal a novel bimodal pattern of functional expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32980–32987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyamoto K., Segawa H., Tatsumi S., Katai K., Yamamoto H., Taketani Y., Haga H., Morita K., Takeda E. Effects of truncation of the COOH-terminal region of a Na+-independent neutral and basic amino acid transporter on amino acid transport in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16758–16763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broer A., Friedrich B., Wagner C. A., Fillon S., Ganapathy V., Lang F., Broer S. Association of 4F2hc with light chains LAT1, LAT2 or y+LAT2 requires different domains. Biochem. J. 2001;355:725–731. doi: 10.1042/bj3550725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenczik C. A., Zent R., Dellos M., Calderwood D. A., Satriano J., Kelly C., Ginsberg M. H. Distinct domains of CD98hc regulate integrins and amino acid transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8746–8752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]