Abstract

The mouse nuclear receptor CAR (constitutively active receptor) is a transcription factor that is activated by phenobarbital-type inducers such as TCPOBOP {1,4 bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene} in liver in vivo. However, CAR is constitutively active in cell-based transfection assays, the molecular mechanism for which has not been elucidated yet. In the model structure of CAR, Thr176 constitutes a part of the ligand-binding surface, but its side chain is not directed toward the surface, instead it forms a hydrogen bond with Thr350 in the AF2 (activation function 2) domain of CAR. Thr350 is known to regulate CAR activity [Ueda, Kakizaki, Negishi, and Sueyoshi (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 1284–1288]. Thr176 was mutated to various amino acids to examine whether this interaction played a role in conferring the constitutive activity. Hydrophobic and positively charged amino acids at position 176 abrogated the constitutive activity, whereas polar and negatively charged amino acids retained it. When one of the small hydrophobic amino acids, such as alanine or valine, was substituted for threonine, the mutants were fully activated by TCPOBOP. The co-activator SRC-1 (steroid receptor co-activator-1) regulated the activity changes associated with the mutations. Thr248 and Ser230 are the Thr176-corresponding residues in human pregnane X receptor and mouse vitamin D3 receptor respectively, interacting directly with the conserved threonine in the AF2 domains. Thr248 and Ser230 also regulated the ligand-dependent activity of these receptors by augmenting binding of the receptors to SRC-1. Thr176, Thr248 and Ser230 are conserved residues in the NR1I (nuclear receptor 1I) subfamily members and determine their activity.

Keywords: activation function 2 (AF2) domain, constitutively active receptor (CAR), nuclear receptor, pregnane X receptor, xenobiotic, vitamin D3 receptor

Abbreviations: AF2, activation function 2; CAR, constitutively active receptor; GST, glutathione S-transferase; h, human; m, mouse; NR1I, nuclear receptor 1I; PXR, pregnane X receptor; RXR, retinoid x receptor; SMRT, silencing mediator for retinoic acid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor; SRC-1, steroid receptor co-activator-1; TCPOBOP, 1,4 bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene; VDR, vitamin D3 receptor; XREM, xenobiotic-responsive enhancer module

INTRODUCTION

Liver cells are endowed with regulatory mechanisms for activating the transcription of genes that encode xenobiotic/steroid-metabolizing enzymes in response to therapeutic drugs and environmental chemicals. The activation results in an adaptive induction of the enzymes, thus increasing cellular metabolic capability. CAR (constitutively active receptor), one of the so-called xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptors, co-ordinates induction of the set of genes, including cytochrome P450 2B and 3A, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and aldehyde dehydrogenase [1–6]. In addition, the receptor may regulate cholesterol, oestrogen, glucose, thyroid and bilirubin metabolism [5,7–10]. Although the roles of CAR in regulating biological activity have become evident, the molecular mechanism of the xenobiotic-dependent activation still remains elusive. One major difficulty in investigating this activation mechanism comes from the fact that CAR loses its xenobiotic-dependent characteristics in cell-based in vitro assay and, instead, exhibits high constitutive activity. With respect to the molecular mechanism of receptor activation, it is generally understood that nuclear receptors undergo a conformational change to convert α-helix 12 [i.e. AF2 (activation function 2) domain] into the so-called active conformation upon binding to agonist, leading the receptors to associate with co-activators such as SRC-1 (steroid receptor co-activator-1) [11–13]. Whereas PXR (pregnane X receptor), a closely-related nuclear receptor to CAR, exhibited low constitutive activity, its X-ray crystallography structure revealed that the AF2 domain was already in the active conformation in the absence of agonistic chemicals [14]. Apparently, the structural basis underlying the constitutive activity of nuclear receptors cannot be understood by the X-ray crystallography structure alone. Site-directed mutagenesis is employed in the present study to examine the molecular basis underlying the constitutive activity of CAR in cell-based transfection assays.

Androstenol represses mCAR (mouse CAR) in HepG2-based transient transfection assays. A target of this repression was previously delineated to residue Thr350 on α-helix 12 of mCAR [15]. When an mCAR structure was modelled from the X-ray crystal structure of the closely related PXR [14], Thr176 on α-helix 3 resided next to residues that interact directly with ligand in the PXR structure, but directed its side chain opposite from a surface of the ligand-binding pocket to form a hydrogen bond with Thr350. In light of these structural observations, Thr176 was mutated to various different amino acids to examine whether the residue was involved in the regulation of the mCAR activity. Then transient transfection, mammalian two-hybrid and GST (glutathione S-tranferase) pull-down assays were used to determine the properties of the mutated receptors. The present study reveals that Thr176 is positioned so that it is capable of regulating the constitutive, as well as TCPOBOP {1,4 bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene}-dependent, activities of CAR by altering the interaction with the co-activator SRC-1. Moreover, similar mutation analysis was extended to the Thr176-corresponding residues in the other NR1I (nuclear receptor 1I) subfamily members PXR and VDR (vitamin D3 receptor), demonstrating that these residues also determine their activity. Thus we identified the Thr176 residue of mCAR as a conserved determinant for the activity of receptors within the NR1I subfamily.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals

TCPOBOP, phenobarbital, chlorpromazine, β-oestradiol, rifampicin and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). 5α-Androsten-3α-ol was purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI, U.S.A.). Methoxychlor was purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, U.S.A.). Stock solution of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 was prepared in ethyl alcohol and the others were in DMSO.

Plasmids

pSG5-hPXR [16], XREM-3A4-Luc [where XREM is xenobiotic-responsive enhancer module; p3A4-362(7836/7208ins)] [17] and pM-SRC-1 [18] plasmids were kindly provided by Steven Kliewer (Department of Molecular Biology, University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.), Bryan Goodwin (High Throughput Biology, Discovery Research, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, U.S.A.) and Anton Jetten (Cell Biology Section, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, NC, U.S.A.) respectively. The following plasmids were constructed previously [2,15,19]: pcDNA3.1-mSRC-1 and pCR3-mCAR that contained the full-length mouse CAR and (NR1)5-tk-luciferase reporter. The mVDR expression vector pCDNA3.1-mVDR was constructed by cloning the entire coding sequence, including the stop codon, into pCDNA3.1-V5-His plasmid. The full-length mCAR, mVDR and hPXR (human PXR) cDNAs were cloned into pACT plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) at the BamHI and XbaI (or KpnI) sites to generate pACT-mCAR, pACT-mVDR and pACT-hPXR respectively. SMRT (silencing mediator for retinoic acid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor) cDNA encoding residues 981 to 1450 was cloned into the pBIND plasmid (Promega) using the BamHI and the XbaI sites to construct pBIND-SMRT. A fragment that encoded residues 632 to 754 of SRC-1 between the BamHI and XhoI sites was inserted into pGEX-4T3 to create the bacterial expression vector pGEX-SRC-1. The pG5luc plasmid was obtained from Promega.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Base mutations were introduced using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) according to the manufacture's instructions using the wild-type pCR3-mCAR, pSG5-hPXR and pCDNA3.1-mVDR plasmids as the templates and appropriate nucleotide primers. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture and transient transfection

HepG2 cells were cultured in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum. HepG2 cells were plated in 24-well plates 1 day before transfection by calcium phosphate co-precipitation using the CellPhect Transfection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.) or Lipofectamine 2000™ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.). The medium was changed 16 h later, and the transfected cells were treated for another 24 h with chemicals or hormones. For transfection with VDR, the medium was changed to one supplemented with 0.5% of charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum. Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and normalized against Renilla reniformis luciferase activity from pRL-SV40 control reporter vector. The results are expressed as the means±S.D. and the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Nuclear protein isolation and Western blotting

Nuclear proteins were extracted as described previously [20] from HepG2 cells that were transfected with the expression plasmids pCR3 bearing mCAR or its mutants. Protein (4 μg) from each extract was separated by SDS/PAGE (NuPage 4–12% gel, Invitrogen), transferred on to a PVDF membrane and the protein was revealed with anti-CAR polyclonal antibody [1,19] and Lumigen PS-3 ECL detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

Gel-shift assays

Gel-shift assays were performed as described previously [1]. mCAR, its mutants and hRXR (human retinoid X receptor) were produced by an in vitro transcription/translation system (TNT T7 quick-coupled system, Promega). 32P-labelled NR1 (40000 c.p.m.) [1] was incubated with a mixture of translated mCAR and hRXR in 10 μl of binding reaction buffer [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.6, containing 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM NaCl and 1.5 μg of poly(dI–dC)]. The mixtures were separated on a 5% acrylamide gel in 7 mM Tris/acetic acid buffer, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM EDTA at 180 V for 1.5 h. The shifted NR1 bands were detected by autoradiography at −70 °C.

GST pull-down assays

GST–SRC-1 was expressed in Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) and was bound to glutathione–Sepharose beads. Various CAR proteins were labelled with [35S]methionine using the TNT T7 quick-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega). Each wild-type or mutant [35S]methionine-labelled mCAR and the beads were mixed in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.6, containing 0.1 M NaCl and 0.1% Triton X (HBST buffer). The mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature with gentle mixing. The beads were washed with HBST buffer three times and re-suspended in 20 μl of 2×NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Samples were separated by electrophoresis on a 4–12% gradient acrylamide Bis/Tris gel (Invitrogen) and proteins were revealed by autoradiography.

Modelling and alignment

A three-dimensional structure of mCAR was modelled using the program O [21]. The respective sequences were obtained from the NCBI website: mCAR (NM_009803), hCAR (NM005122), mPXR (AF031814), hPXR (AF061056), mVDR (NM_009504) and hVDR (AF026260). Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package version 10.3 Unix was used to align the sequences.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Possible interaction of Thr176 with Thr350

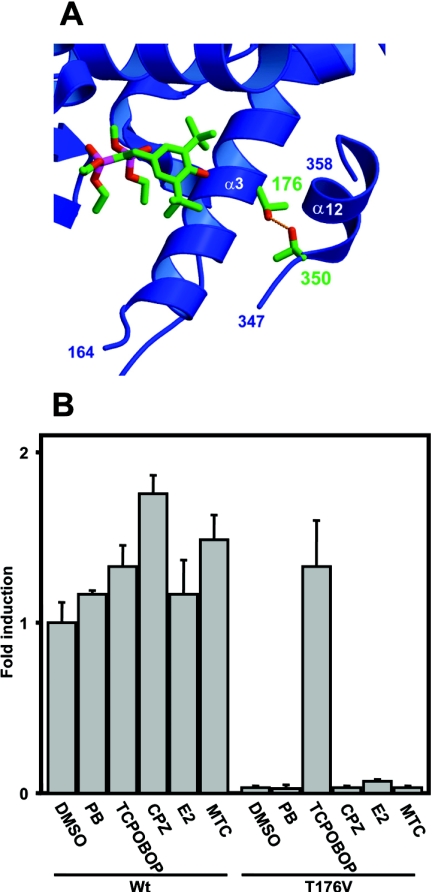

In a model structure of mCAR, based on the X-ray crystallography structure of hPXR, the AF2 domain is in the active conformation, as is the corresponding domain in the PXR structure. Thus CAR and PXR resembled the relative orientations and positions of the AF2 domain, despite the differences in the level of their constitutive activities. The Thr176 residue of mCAR, superimposed with Thr248 of the hPXR, orientates the side chain hydroxy group away from the surface of the ligand-binding pocket to reside within hydrogen bonding distance to Thr350 in the AF2 domain (Figure 1A). To investigate the interaction between Thr176 and Thr350, Thr176 was mutated to the similar size hydrophobic residue valine, and the activity of the mutant was examined (Figure 1B). The Val176 mutant exhibited extremely low constitutive activity, less than 5% of the activity of wild-type mCAR. When various mCAR activators (TCPOBOP, β-oestradiol, phenobarbital, chrolpromazine and methoxychlor) were examined for their ability to activate the Val176 mutant, only TCPOBOP was successful. In fact, TCPOBOP activated the mutated receptor more than 30-fold (Figure 1B). As a result, the valine substitution of Thr176 converted the constitutively activated mCAR into a receptor capable of being directly activated by TCPOBOP, indicating that the position of Thr176 is critical for determining both the constitutive and TCPOBOP-dependent activities.

Figure 1. Thr176 of mCAR and its valine substitution.

(A) Interaction of Thr176 with Thr350 in the model structure of mCAR. The ligand molecule in the PXR structure [14] is shown by superimposing it with the CAR structure. Numbers indicate the two conserved threonine residues. (B) The wild-type mCAR (Wt) and the Thr176→Val (T176V) mutant were co-transfected into HepG2 cells with (NR1)5-tk-luciferase plasmid (0.1 μg) and pRL-SV40 (0.01 μg), which is an R. reniformis luciferase expression plasmid for normalization of transfection efficiency. After 16 h, cells were subsequently treated with phenobarbital (PB; 1 mM), TCPOBOP (250 nM), chlorpromazine (CPZ, 10 μM), oestradiol (E2, 10 μM) or methoxychlor (MTC, 10 μM) for an additional 24 h before preparation of lysates for luciferase assay. The fold activation was calculated relative to the activity with DMSO for the wild-type receptor as 1. The results are expressed as the means±S.D. from three independent experiments.

Residue 176-dependent alteration of mCAR activity

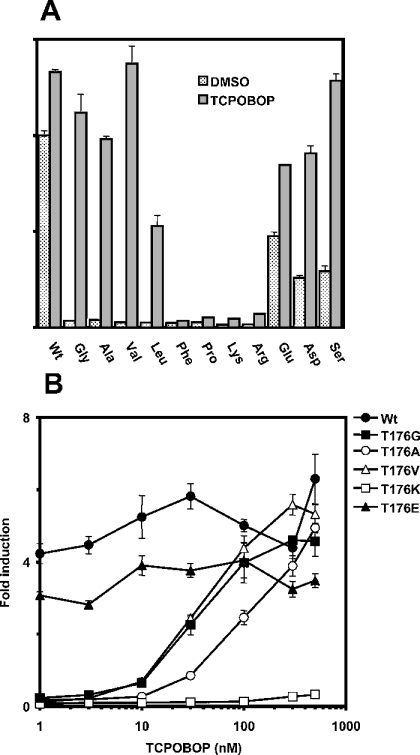

To examine the underlying structural basis of Thr176 determining mCAR activity, the residue was subsequently mutated to various hydrophobic amino acids (glycine, alanine, leucine, phenylalanine and proline), positively charged amino acids (lysine and arginine), negatively charged amino acids (glutamic acid and aspartic acid) and a polar amino acid (serine). Each of these mutated receptors was co-transfected into HepG2 cells, and its ability to activate an NR1–luciferase reporter gene was examined. The mutations of Thr176 to any of the hydrophobic amino acids abolished the receptor's constitutive activity (Figure 2A). Although the constitutive activity was also abolished when Thr176 was mutated to the positively charged amino acids, it was reduced only modestly when serine or one of the negatively charged amino acids was substituted at position 176. These results suggested that the interaction of Thr176 with Thr350 may, in fact, be present and is involved in conferring the high constitutive activity on mCAR. Among the mCAR mutants having hydrophobic amino acids at position 176, the Gly176, Ala176 and Val176 mutants could be fully activated by 250 nM TCPOBOP. The Leu176 mutant was activated only to 50% of the wild-type activity, whereas the Phe176 and Pro176 mutants were no longer activated. Therefore, substitution with small hydrophobic amino acids converted mCAR into the receptor that was directly activated by TCPOBOP.

Figure 2. Activities of various mCAR mutants at position 176.

(A) A given expression plasmid containing each mCAR mutant (0.2 μg) was co-transfected into HepG2 cells with (NR1)5-tk-luciferase plasmid (0.1 μg) and pRL-SV40 (0.01 μg) for 16 h. Then cells were treated with DMSO or TCPOBOP (250 nM) for an additional 24 h and subjected to luciferase assay. Activity was expressed as fold activation relative to the activity with DMSO for the wild-type receptor as 1. (B) Transfected cells were treated with DMSO or 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 and 500 nM TCPOBOP under the same conditions as described above. The results are expressed as the means±S.D. from three independent experiments.

The Ser176 mutant and those having the negatively charged amino acids at position 176 were also activated by TCPOBOP, although their constitutive activities marginalized the degree of the activation (Figure 2A). On the other hand, the mCAR mutants with the positively charged residues at 176 were not activated by TCPOBOP at all.

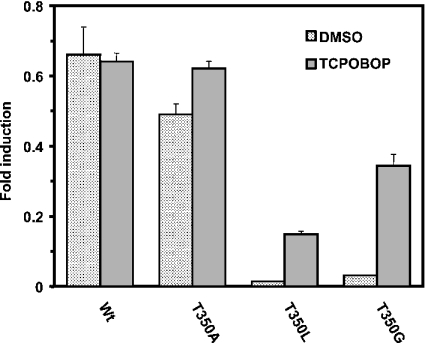

In our previous work, the substitution of Thr350 with methionine retained the constitutive activity of mCAR [15], raising a question about the functional significance of the observed hydrogen bonding interaction of Thr176 with Thr350 in the model structure (Figure 1A). To further investigate this question, we mutated Thr350 of mCAR to glycine, alanine or leucine, and examined their transactivation activity of the reporter gene in HepG2 cells (Figure 3). The Ala350 mutant exhibited a high constitutive activity similar to wild-type mCAR, whereas the Gly350 and Leu350 mutants decreased the activity to the same levels observed with the Gly176 and Leu176 mutants. Moreover, similar to the corresponding mutations at position 176, both Gly350 and Leu350 mutants were activated by TCPOBOP. Thus the hydrogen bond appeared to be favourable for the high constitutive activity of mCAR, but non-essential for its maintenance. However, a hydrophobic residue at positions 176 and 350 could play the same functional role in regulating the activity of mCAR, suggesting that a given mutation either at position 176 or 350 could be similarly accommodated in a certain conformation necessary for the receptor activity. In addition to the hydrophobicity and size, alanine characteristically has the highest α-helix propensity, which may be a reason for the mutant retaining the high constitutive activity, by preventing flexibility of the receptor's α-helix 12.

Figure 3. Activity of mCAR mutants at position 350.

A given expression plasmid containing each mCAR mutant (0.2 μg) was co-transfected into HepG2 cells with (NR1)5-tk-luciferase plasmid (0.1 μg) and pRL-SV40 (0.01 μg) for 16 h. Then cells were treated with DMSO or TCPOBOP (250 nM) for an additional 24 h and subjected to luciferase assay. The results are expressed as the means±S.D. from three independent experiments.

The mutated receptors can be categorized into three distinct groups on the basis of their phenotypes. The first group included receptors that exhibited high constitutive activity, but poor or no TCPOBOP activation. The second one comprised those that had low constitutive activity and were activated effectively by TCPOBOP, whereas the last group had the receptors with low constitutive activity and no TCPOBOP activation. Representing the first, second and third groups respectively, the Glu176, Val176, Gly176 and Ala176 and Lys176 mutants were further examined for their concentration dependency of TCPOBOP activation (Figure 2B). Similar to the wild-type receptor, the Glu176 mutant was not activated by TCPOBOP at any concentration. The Val176, Gly176 and Ala176 mutants were activated in a concentration-dependent manner with EC50 values of approx. 50 (Val, Gly) and 100 nM (Ala). On the other hand, the Lys176 mutant was a truly inactive receptor and was not activated by TCPOBOP at all. These results indicated that Thr176 was a structural factor that could determine the activity of mCAR.

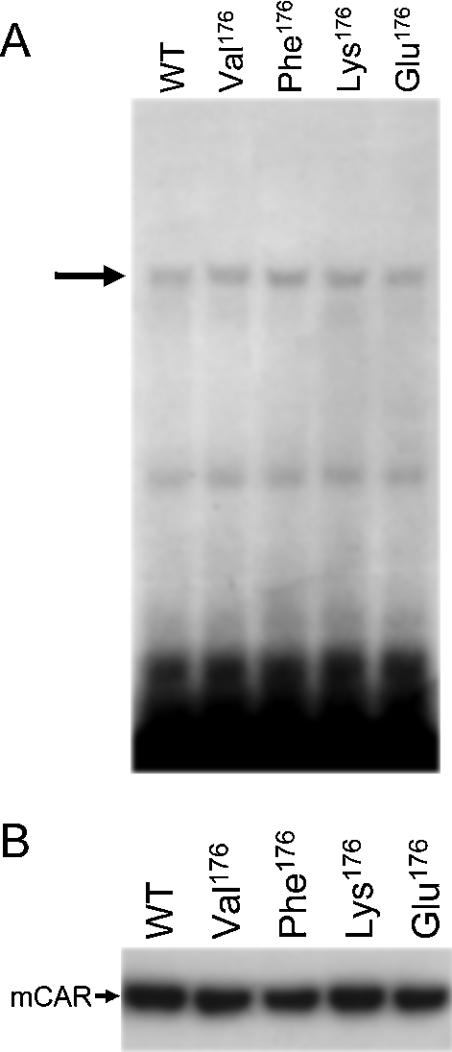

Nuclear accumulation and DNA binding of receptors

Since the activity of nuclear receptors could be affected by their nuclear accumulation and binding to DNA elements in cell-based transactivation assays, we selected the Val176, Phe176, Lys176 and Glu176 mutants to represent their groups of side chains, and performed Western blotting to examine their levels in the transfected HepG2 cells and gel-shift assays to determine their binding ability to NR1 probe (Figure 4). All the mutants tested were capable of binding to an NR1 probe to the same degree as wild-type mCAR (Figure 4A). As is known for wild-type mCAR, all the mutants were spontaneously accumulated in the nucleus of the transfected cells (Figure 4B). Moreover, the levels of their accumulation were nearly identical with and no different to the wild-type mCAR. These results indicated that the ability of these mutants to accumulate in the nucleus or to bind to the response element NR1 is not a defining factor in the functional phenotypes of the mutants.

Figure 4. Intracellular localization and DNA-binding activity of mCAR and its mutants.

(A) Gel-shift analysis of mCAR and mutants. In vitro translated wild-type mCAR (WT) and various mutants (Val176, Phe176, Lys176 and Glu176) were incubated with 32P-labelled NR1. Mobility-shifted bands of NR1 caused by the formation of a complex between mCAR–hRXR are indicated by an arrow. (B) Western blotting detection of mCAR and its mutants (Val176, Phe176, Lys176 and Glu176) in nuclear extracts from HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were transfected as described in the Experimental section, from which nuclear proteins were extracted and separated on an SDS/PAGE gel. Wild-type mCAR (WT) and the mutants were detected with anti-CAR polyclonal antibody.

Co-regulation of mCAR mutants

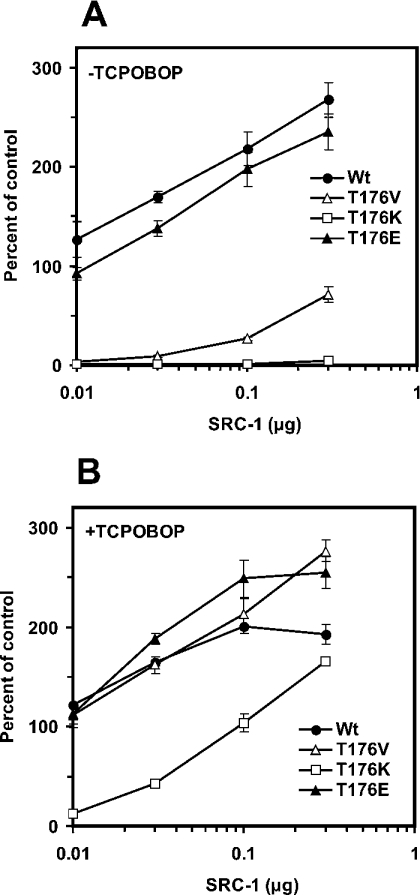

We examined whether co-regulators, such as SRC-1 and SMRT, affected the activity of the mCAR mutants differently. First, transient transfection assays were performed under increasing amounts of pCDNA3.1-SRC-1. Whereas wild-type mCAR and the Glu176 mutant activated (NR1)5-tk-Luc without the additional co-transfection of SRC-1, the activity was enhanced further as the amount of SRC-1 increased (Figure 5A). The Val176 mutant began to exhibit activity at 0.1 μg of the SRC-1 plasmid, but the maximum level of activity reached only 25% of that of wild-type mCAR and the Glu176 mutant. Thus SRC-1 augmented differently the constitutive activities, depending on the type of residue at position 176. The Lys176 mutant displayed no constitutive activity, even at the highest SRC-1 concentration (0.3 μg) tested it was fully activated by TCPOBOP to the levels observed with the wild-type (Figure 5B). These results indicate that position 176 could regulate the interaction of mCAR with SRC-1 in the presence and absence of TCPOBOP.

Figure 5. Co-activation by SRC-1 of mCAR and its mutants.

Expression vectors of the wild-type and each mutant were co-transfected with (NR1)5-tk-luciferase plasmid (0.1 μg), pRL-SV40 (0.01 μg) and various amounts of the SRC-1-expression plasmid (0.01, 0.03, 0.1 and 0.3 μg) into HepG2 cells. Then cells were treated with DMSO (A) or 250 nM TCPOBOP (B) for 24 h, harvested, lysed and subjected to luciferase assay. The NR1–luciferase activities (means±S.D.) were determined as described in the previous Figure legends.

Mammalian two-hybrid assays were performed to provide further evidence to support the hypothesis that Thr176 regulates the interaction of mCAR with SRC-1. The relative binding to the various mutants was calculated, using the binding of SRC-1 to wild-type mCAR as 100% (Figure 6A). No SRC-1 binding was detected with the Val176 and Lys176 mutants, whereas SRC-1 bound to the Glu176 mutant at a similar level to that observed with wild-type mCAR. The degrees of SRC-1 binding correlated with those of the NR1 activation of the corresponding mutants that were shown in Figure 2(A). In addition to the Val176 mutant, the Gly176 and Ala176 mutants were examined with respect to their ability to interact with SRC-1. The Gly176 mutant did not show binding to SRC-1, whereas the Ala176 mutant decreased the binding by only 50%, suggesting that the size of the hydrophobic side chain is a factor reflecting the ability to interact with SRC-1 constitutively.

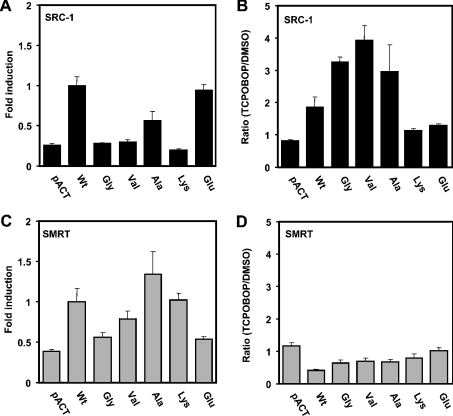

Figure 6. Interaction with the co-regulators SRC-1 and SMRT.

Mammalian two hybrid assays were performed as described in the Experimental section. The VP16-fused wild-type (Wt) and mutant receptors (0.2 μg) were co-transfected with Gal–SRC-1 (A, B) or Gal–SMRT (C, D) (0.2 μg) in the presence of pCMX-RXR (0.2 μg) and pG5luc vector (0.2 μg) into HepG2 cells. Then cells were treated with DMSO (A, C) or TCPOBOP (B, D) for 24 h, harvested, lysed and subjected to luciferase assay. The results are expressed as the means±S.D. from three experiments. In (A) and (C) the fold induction was calculated by taking the binding of SRC-1 to wild-type mCAR as 100% in the absence of TCPOBOP, whereas (B) and (D) show the ratio of the luciferase activities (TCPOBOP against DMSO) of a given receptor.

In the presence of TCPOBOP, the Val176 mutant exhibited a 4-fold increase in binding to SRC-1 compared with the same interaction in the absence of TCPOBOP, followed by the Gly176 and Ala176 mutants that exhibited 3.5-fold and 2-fold increased binding respectively (Figure 6B). The Lys176 mutant, as well as the Glu176 mutant, which retained constitutive activity, did not exhibit increased interaction in the presence of TCPOBOP. Thus the ability of the various mutants to activate the NR1 was, by and large, reflected in their capabilities to interact with SRC-1 in both the absence and presence of TCPOBOP, substantiating the hypothesis that Thr176 dictates SRC-1 binding to regulate mCAR activity. The interaction of mCAR and its mutants with the co-repressor SMRT were also examined in the mammalian two-hybrid assays. Although some of them appeared to interact with SMRT in the presence or absence of TCPOBOP, no correlation was observed between their binding and activity (Figures 6C and 6D).

GST pull-down assays were also performed to show the direct binding specificity of SRC-1 to the mutants. The in vitro translated SRC-1 bound to GST–mCAR. The binding was repressed by androstenol and was fully restored by TCPOBOP, as reported previously [22]. However, the mutants Val176 and Lys176 exhibited the same binding pattern as wild-type mCAR (results not shown). This was perhaps due to the GST-pull down assay not being sensitive enough to detect the subtle differences in the SRC-1 binding that were observed in the two-hybrid and luciferase reporter assays.

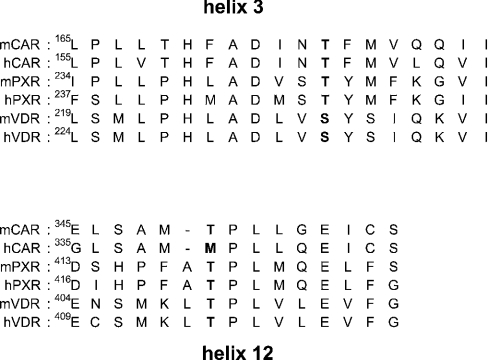

Mutation of the Thr176-corresponding residues in PXR and VDR

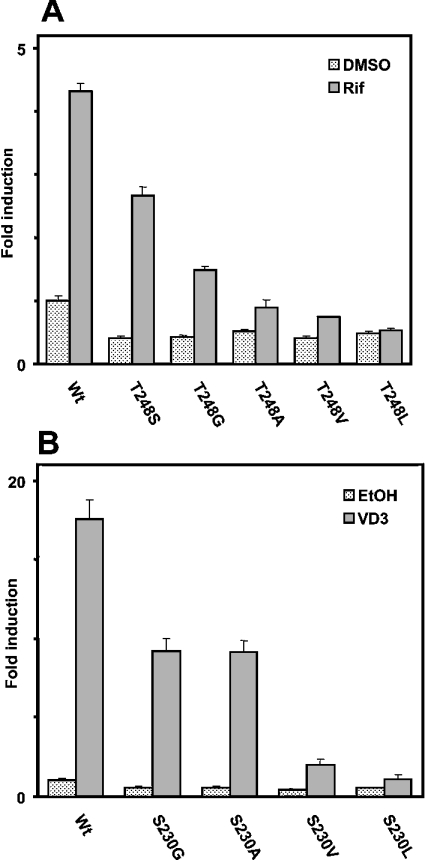

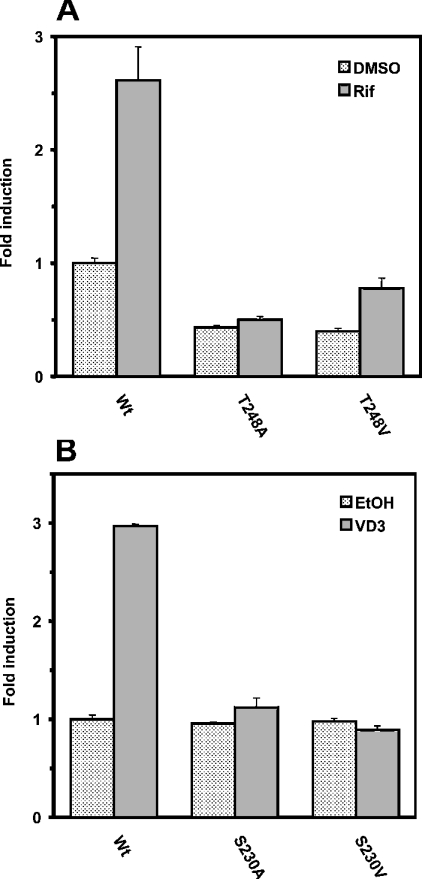

A sequence alignment revealed that Thr176 of mCAR is conserved in the other NR1I subfamily members PXR and VDR; Thr248 and Ser230 in human PXR and mouse VDR respectively (Figure 7). In the crystal structure of human PXR [14], similar to the interaction of Thr176 with Thr350 of mCAR, the side chain of Thr248 is hydrogen bonded to Thr422 in α-helix 12. We mutated Thr248 of PXR to serine and found that the Ser248 mutant was activated by rifampicin to approx. 70% of the level observed with the wild-type PXR (Figure 8A). Due to the lower constitutive activity, activation of this mutant by rifampicin was nearly 6-fold compared with the 3.3-fold of wild-type PXR. Then Thr248 was mutated to various hydrophobic amino acids (glycine, alanine, valine and leucine) to examine any correlation between the size of side chain and activation by rifampicin. The mutated receptor with the smallest side chain Gly248 was still activated by rifampicin, but only to 40%. PXR sharply decreased its activation capability as the size of side chain became larger, and it was abrogated when leucine was placed at position 248 (Figure 8A). Thus these results indicated that the hydrogen-bonding interaction of Thr248 with Thr422 is critical for PXR, if not essential, to retain the activation by rifampicin.

Figure 7. Sequence alignments of α-helices 3 and 12 of CAR, PXR and VDR.

The conserved threonine/serine residues in α-helices 3 and 12 are in bold.

Figure 8. Regulation of the hPXR and mVDR activity by residues aligned with Thr176.

(A) The expression plasmid containing each human PXR and its mutants (0.2 μg) was co-transfected with XREM-3A4-Luc (0.1 μg) and pRL-SV40 (0.0 1μg) into HepG2 cells for 16 h. Subsequently cells were treated with DMSO or rifampicin (Rif; 10 μM) for an additional 24 h. (B) The expression plasmid containing mouse VDR and its mutants (0.2 μg) was co-transfected with XREM-3A4-Luc (0.1 μg) and pRL-SV40 (0.01 μg) into HepG2 cells for 16 h. Then cells were treated with ethanol (EtOH) or vitamin D3 (VD3; 100 nM) for an additional 24 h. Luciferase activities (means±S.D.) were determined as described for previous experiments.

The X-ray crystallography structure of human VDR revealed that Ser235 is also hydrogen bonded with Thr415 in α-helix 12 [23]. Ser235 and Thr415 correspond to Ser230 and Thr410 of mouse VDR (Figure 7). Thus Ser230 was mutated to glycine, alanine, valine and leucine, and the mutated receptors were subjected to XREM-3A4-Luc reporter assays. Both the Gly230 and Ala230 mutants remained activated by vitamin D3, but only to 50% of the level observed with the wild-type VDR (Figure 8B). Thus the hydrogen bond of Ser230 with Thr410 appeared not to be so critical for retaining the activation capacity of VDR by vitamin D3. However, a bulky hydrophobic side chain at position 230 was destructive to the activity, since the Val230 and Leu230 mutants were virtually inactive. Finally, the mammalian two-hybrid assay was employed to examine whether the inactivation of VDR and PXR by bulky hydrophobic side chains reflected the interaction of the receptors with SRC-1. Alanine or valine at position 248 abrogated the SRC-1 interaction of the PXR mutants (Figure 9A), consistent with the fact that the same mutations inactivated PXR-mediated XREM activation by rifampicin (Figure 8A). Also, both Ala230 and Val 230 mutants of VDR did not interact with SRC-1 (Figure 9B). This two-hybrid assay did not detect the large difference in the interactions, as did the XREM-3A4-Luc reporter assay showing that the Ala230 mutant possessed higher activity than the Val230 mutant (Figure 9B). Although a reason for the discrepancy was not known, it could result from a limited sensitivity of this particular two-hybrid assay. The mutations clearly affected the ability of PXR and VDR to interact with SRC-1. Our present study demonstrated that Thr176 of mCAR, and the corresponding Thr248 and Ser230 in hPXR and mVDR respectively, are the conserved residues that can determine the activities of these NR1I receptors. The side chain of these residues interacts with the conserved threonine residues in the AF2 domains of these receptors, thus regulating the binding to the co-activator SRC-1. This hydrogen-bond interaction appeared to be essential for the ligand-dependent recruitment of SRC-1, thus activating the receptor.

Figure 9. Interaction of hPXR and mVDR with SRC-1.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay was performed as described in the Experimental section. The VP16-fused wild-type (Wt) and mutated receptors (0.2 μg) were co-transfected with Gal–SRC-1 (0.2 μg) and pG5luc vector (0.2 μg) into HepG2 cells for 16 h. Cells were treated with DMSO or rifampicin (Rif; 10 μM) for hPXR (A) and EtOH or vitamin D3 (VD3; 100 nM) for mVDR (B) for further 24 h. Luciferase activities (means±S.D.) were determined as described for previous experiments.

Although the lack of a X-ray crystal structure for CAR limits our interpretation of the present studies, the CAR model structure suggests that the AF2 domain is always in an active conformation, consistent with the constitutively active nature of this receptor. The predicted hydrogen-bond interaction between Thr176 and Thr350 is required for the constitutive activity, indicating that the hydrogen bond is involved in constraining the binding of SRC-1 in the absence of ligand. Therefore, the receptor loses its constitutive activity, once this interaction is eliminated by mutating Thr176 to the various hydrophobic amino acids. A small hydrophobic amino acid at position 176 can be accommodated in an interface between α-helices 3 and 12, after the receptor is bound to TCPOBOP. Thus the binding of TCPOBOP strengthens the interaction of the hydrophobic residues at position 176 and Thr350, which is sufficient to constrain the AF2 domain in the active conformation. Thr166 in hCAR corresponds to Thr176 of mCAR, whereas Met340 substitutes for Thr350 of mCAR in hCAR (Figure 7). Unlike the case of mCAR, the mutations of Thr166 did not alter the constitutively active nature of hCAR (results not shown). Noticeably, among the NR1I receptors CAR, PXR and VDR, hCAR is the only receptor in which the corresponding threonine residue in the AF2 domain is not conserved. Since the corresponding hydrogen-bond interactions are conserved in the X-ray crystal structures of PXR and VDR, and because these interactions had an effect on the activity of the receptors, it is reasonable to predict the interaction of Thr176 with Thr350 in mCAR and to speculate that the interaction may also be play a role in regulating mCAR activity. However, the possibility remains that Thr176 regulates the activity of mCAR, although not through this interaction. A more detailed investigation into whether the Thr176–Thr350 interaction is the sole regulatory factor should be conducted when an X-ray crystal structure of mCAR becomes available in the future.

The side chains of Thr248 and Ser235 are not oriented toward the surface of the ligand-binding site in the PXR and hVDR structures respectively, so that they do not interact directly with ligand [14,23]. However, the side chains of the nearest residues, Ser247 (in PXR) and Val234 (in VDR), interact directly with the ligand molecules, but are not in a position to interact with the AF2 domain. The Ser247 and Thr248 of PXR (or the Val234 and Ser235 of hVDR) may play different roles in the regulation of the receptors' activity: the hPXR Ser247 and hVDR Val234 serve for ligand binding, whereas the hPXR Thr248 and hVDR Ser235 may affect AF2 domain configuration through the hydrogen bond between these residues with the counterparts in α-helix 12. In conclusion, we have identified Thr176 of mCAR as the conserved residue within the NR1I subfamily receptors, which plays a key role in the binding to SRC-1, thus determining the receptors' activities. Although this Thr residue is also found in numerous other nuclear receptors [24], whether the conserved threonine residues may play a general role in regulating the activities beyond the NR1I subfamily remains unexplored.

References

- 1.Honkakoski P., Zelko I., Sueyoshi T., Negishi M. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5652–5658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sueyoshi T., Kawamoto T., Zelko I., Honkakoski P., Negishi M. The repressed nuclear receptor CAR responds to phenobarbital in activating the human CYP2B6 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6043–6046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei P., Zhang J., Egan-Hafley M., Liang S., Moore D. D. The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature (London) 2000;407:920–923. doi: 10.1038/35038112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugatani J., Kojima H., Ueda A., Kakizaki S., Yoshinari K., Gong Q.-H., Owens I. S., Negishi M., Sueyoshi T. The phenobarbital response enhancer module in the human bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A1 gene and regulation by the nuclear receptor CAR. Hepatology. 2001;33:1232–1238. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda A., Hamadeh H. K., Webb H. K., Yamamoto Y., Sueyoshi T., Afshari C. A., Lehmann J. M., Negishi M. Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61:1–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sueyoshi T., Negishi M. Phenobarbital response elements of cytochrome P450 genes and nuclear receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:123–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamoto T., Kakizaki S., Yoshinari K., Negishi M. Estrogen activation of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR (constitutive active receptor) in induction of the mouse Cyp2b10 gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1898–1905. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.11.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto Y., Kawamoto T., Negishi M. The role of the nuclear receptor CAR as a coordinate regulator of hepatic gene expression in defense against chemical toxicity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;409:207–211. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang W., Zhang J., Chua S. S., Qatanani M., Han Y., Granata R., Moore D. D. Induction of bilirubin clearance by the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4156–4161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630614100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maglich J. M., Watson J., McMillen P. J., Goodwin B., Willson T. M., Moore J. T. The nuclear receptor CAR is a regulator of thyroid hormone metabolism during caloric restriction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19832–19838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., Cobb J. E., Lambert M. H., Kurokawa R., Rosenfeld M. G., Willson T. M., Glass C. K., Milburn M. V. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature (London) 1998;395:137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiau A. K., Barstad D., Loria P. M., Cheng L., Kushner P. J., Agard D. A., Greene G. L. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1998;23:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins R. E., Wisely G. B., Moore L. B., Collins J. L., Lambert M. H., Williams S. P., Willson T. M., Kliewer S. A., Redinbo M. R. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR: structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science (Washington, D.C.) 2001;292:2329–2333. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda A., Kakizaki S., Negishi M., Sueyoshi T. Residue threonine 350 confers steroid hormone responsiveness to the mouse nuclear orphan receptor CAR. Mol. Phamacol. 2002;61:1284–1288. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.6.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann J. M., McKee D. D., Watson M. A., Willson T. M., Moore J. T., Kliewer S. A. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1016–1023. doi: 10.1172/JCI3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin B., Hodgson E., Liddle C. The orphan human pregnane X receptor mediates the transcriptional activation of CYP3A4 by rifampicin through a distal enhancer module. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1329–1339. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurebayashi S., Nakajima T., Kim S.-C., Chang C.-Y., McDonnell D. P., Renaud J.-P., Jetten A. M. Selective LXXLL peptides antagonize transcriptional activation by the retinoid-related orphan receptor RORγ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;315:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamoto T., Sueyoshi T., Zelko I., Moore R., Washburn K., Negishi M. Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6318–6322. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta. Crystallogr. Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forman B. M., Tzameli I., Choi H. S., Chen J., Simha D., Seol W., Evans R. M., Moore D. D. Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-β. Nature (London) 1998;395:612–615. doi: 10.1038/26996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tocchini-Valentini G., Rochel N., Wurtz J. M., Mitschler A., Moras D. Crystal structures of the vitamin D receptor complexed to superagonist 20-epi ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:5491–5496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091018698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giguere V. Orphan nuclear receptors: from gene to function. Endcrinol. Rev. 1999;20:689–725. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]