Abstract

Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting prolong the lifespan and healthspan of model organisms and improve human health. The natural polyamine spermidine has been similarly linked to autophagy enhancement, geroprotection and reduced incidence of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases across species borders. Here, we asked whether the cellular and physiological consequences of caloric restriction and fasting depend on polyamine metabolism. We report that spermidine levels increased upon distinct regimens of fasting or caloric restriction in yeast, flies, mice and human volunteers. Genetic or pharmacological blockade of endogenous spermidine synthesis reduced fasting-induced autophagy in yeast, nematodes and human cells. Furthermore, perturbing the polyamine pathway in vivo abrogated the lifespan- and healthspan-extending effects, as well as the cardioprotective and anti-arthritic consequences of fasting. Mechanistically, spermidine mediated these effects via autophagy induction and hypusination of the translation regulator eIF5A. In summary, the polyamine–hypusination axis emerges as a phylogenetically conserved metabolic control hub for fasting-mediated autophagy enhancement and longevity.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Macroautophagy, Metabolomics, Autophagy

Hofer et al. show that fasting promotes the synthesis of spermidine, which stimulates eIF5A hypusination to induce autophagy and increase lifespan in various species in a conserved manner.

Main

Continuous caloric restriction (CR) remains the gold standard for extending the lifespan and healthspan of model organisms1,2. Recently, intermittent fasting (IF) interventions, often combined with CR, emerged as alternatives for clinical implementation3. However, to date, it remains uncertain whether IF offers health benefits due to the temporary cessation of caloric intake (without CR) or due to a net reduction of total calories de facto resulting in CR4–6. IF, like CR, delays hallmarks of aging in yeast, worms, insects and mice3,7–9. In humans, intermittent7 and long-term10 fasting, as well as continuous CR11, are associated with favourable effects on multiple health-relevant parameters that may share a common mechanistic basis. Strong evidence exists that macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as ‘autophagy’) mediates these effects12.

In mammals, an age-associated reduction in autophagic flux13 contributes to the accumulation of protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles, failing pathogen elimination and exacerbated inflammation14. Genetic autophagy inhibition accelerates aging processes in mice13 and loss-of-function mutations of genes that regulate or execute autophagy have been causally linked to cardiovascular, infectious, neurodegenerative, metabolic, musculoskeletal, ocular and pulmonary diseases, many of which resemble premature aging15–18. Conversely, genetic autophagy stimulation promotes healthspan and lifespan in model organisms, including flies19 and mice20,21. Besides nutritional interventions, administering the natural polyamine spermidine (SPD) to yeast, worms, flies and mice is another strategy to extend the lifespan in an autophagy-dependent fashion22–26. Moreover, SPD restores autophagic flux in circulating lymphocytes from aged humans25,27, coinciding with the observation that increased dietary SPD uptake is associated with reduced overall mortality in human populations28.

Hence, fasting, CR and SPD extend the lifespan of model organisms and activate phylogenetically conserved, autophagy-dependent geroprotection. Intrigued by these premises, we investigated whether the geroprotective effects of IF might be connected to, or depend on, SPD.

Results

Fasting elevates spermidine levels

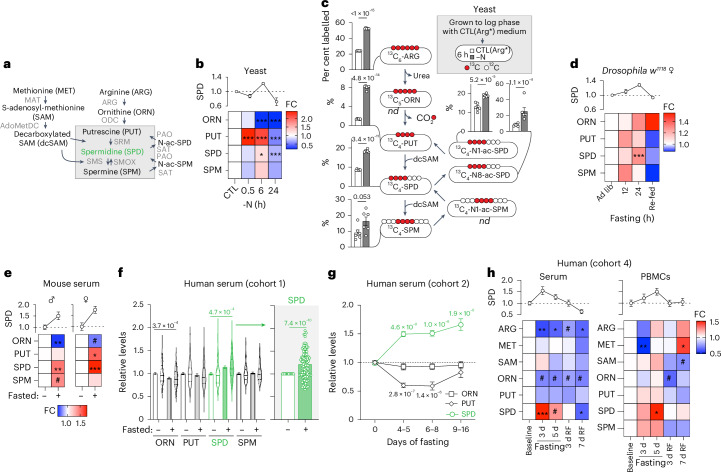

To investigate polyamine metabolism during IF, we subjected four different organisms to acute fasting stimuli. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantification of SPD, the primary biologically active polyamine and its precursors ornithine (ORN), putrescine (PUT), as well as its metabolite spermine (SPM) (Fig. 1a) revealed a uniform increase in polyamine content upon fasting across various species.

Fig. 1. Fasting induces polyamine synthesis in various species.

a, Schematic overview of the polyamine pathway and adjacent metabolites. AdoMetDC, adenosylmethionine decarboxylase; ARG, arginase; MAT, methionine adenosyltransferase; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; SAT, SPD/SPM acetyltransferase, SRM, spermidine synthase; SMOX, spermine oxidase; SMS, spermine synthase; PAO, polyamine oxidase. b, Polyamine levels of WT BY4741 yeast shifted to nitrogen-deprived medium (−N) for the indicated times. Data are normalized to the mean of the control (CTL) condition at every time point. Note that the statistics were performed together with additional groups as indicated in Supplementary Fig. 1a. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). c, WT BY4741 yeast cells were pre-labelled with 13C6-arginine [CTL(Arg*)] and shifted to CTL(Arg*) or −N medium for 6 h. MS-based analysis of labelled products revealed a uniform increase in percentage of labelled polyamines in N-starved cells. nd, not detected. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). d, Polyamine levels of young female w1118 flies fasted for 12 or 24 h (starting at 20:00 upon lights turned off). Data are normalized to the ad libitum (ad lib) group at every time point. Re-fed, 12 h re-feeding after 24 h fasting. n = 5 (re-fed, 24 h ad lib ORN), 6 (24 h ad lib PUT, SPD and SPM), 7 (rest) biologically independent samples (groups of flies). e, Serum polyamine levels of young male and female C57BL/6 mice fasted or kept ad lib for 14–16 h overnight, starting at 16:00–17:00). n = 5 (male), 8 (female) mice. f, Relative polyamine levels in human serum from cohort 1 after fasting (9 (7–13) days) depicted as mean with s.e.m. and violin plots, showing median and quartiles as lines. The extra panel depicts the individual increase in SPD levels for every volunteer. n = 104 (PUT), 109 (SPD baseline), 100 (SPM baseline), 105 (SPD fasted), 94 (SPM fasted) volunteers. g, Relative polyamine levels in human serum from cohort 2 after increasing numbers of fasting days. n = 61 (baseline PUT), 62 (baseline ORN and SPD), 22 (4–5 d PUT and SPD), 25 (4–5 d ORN, 6–8 d ORN), 19 (6–8 d PUT), 20 (6–8 d SPD), 9 (9–16 d PUT and SPD), 13 (9–16 d ORN) volunteers. h, Relative polyamine and precursor levels in human serum and PBMCs from cohort 4 after increasing numbers of fasting days. BL, baseline, RF = days 3 or 7 after re-introduction of food. N (serum) = 7 (BL SAM), 11 (3 d SAM), 12 (7d RF SAM), 13 (5d SAM), 14 (BL PUT and SPD), 15 (BL ARG and MET; 5 d ARG; 3d RF SAM), 16 (BL ORN; 5 d MET, ORN, PUT and SPD), 17 (3 d ARG, MET, ORN, PUT and SPD; 7 d RF ARG, MET, ORN, PUT and SPD), 18 (3 d RF ARG, MET, ORN, PUT and SPD) volunteers. N (PBMCs) = 6 (5 d ORN), 7 (5 d rest), 9 (BL SPD), 10 (BL rest), 11 (3 d RF SPD) 12 (3 d SPD and SPM; 3 d RF rest), 13 (3 d rest; 7 d RF) volunteers. Statistics used were two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (b,d,f,h) and two-tailed Student’s t-tests (c). For every analyte (e) two-way ANOVA with false discovery rate (FDR) correction (two-stage step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, Q = 0.05) together with data depicted in Extended Data Fig. 1f–i (male) and Extended Data Fig. 1k–n (female). Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (f). Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test (g). FC, fold change to control. Heatmaps show means. Bar and line graphs show mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, #P < 0.2. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Starving Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) cells in water increased the levels of SPD and SPM (Extended Data Fig. 1a), similar to glucose restriction (Extended Data Fig. 1b), while ORN generally decreased. Nitrogen starvation (−N), a classical autophagy-inducing intervention29,30, elicited a fast and transient increase in polyamines, mainly PUT, accompanied by a drastic decrease in the precursor ORN (Fig. 1b). To shed light on the dynamics under −N, we studied metabolic flux in yeast using 13C6-labelled arginine (ARG). We found that the cellular levels of ARG-derived polyamines after 6 h of nitrogen deprivation were higher than in N-containing control medium (Fig. 1c). Thus, despite the elimination of extracellular nitrogen, polyamine flux remained active, favouring the utilization of residual ARG molecules for polyamine synthesis.

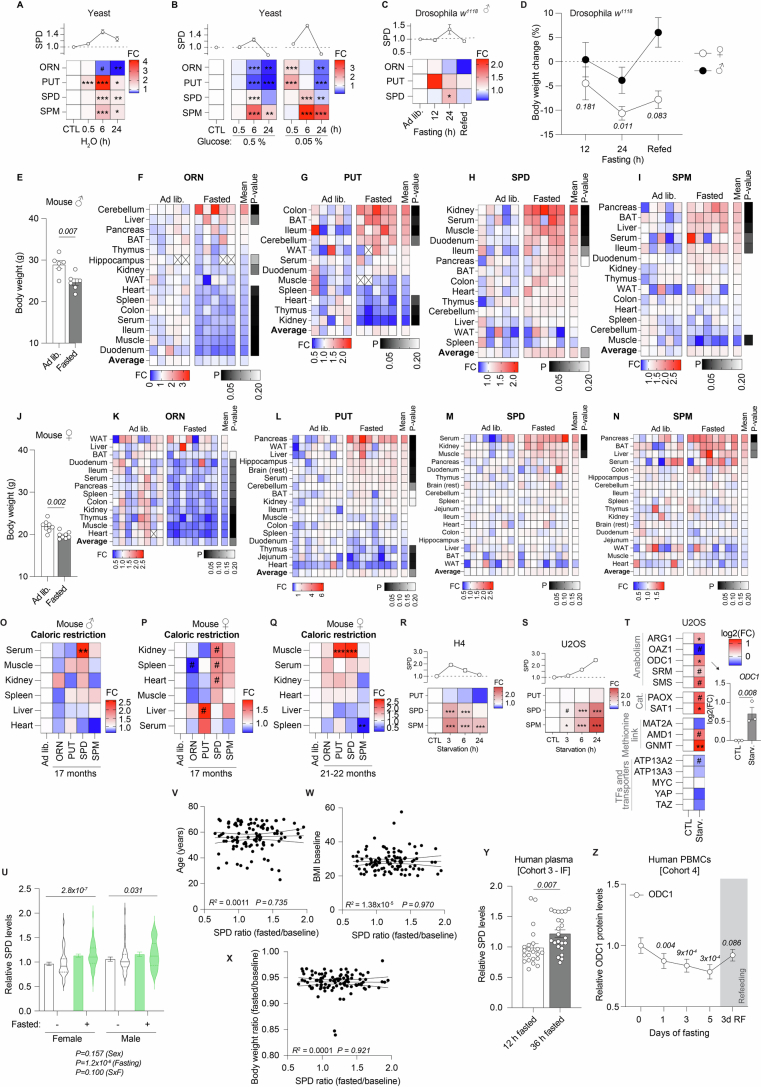

Extended Data Fig. 1. Changes in polyamine levels in starving organisms.

(a) Polyamine levels of WT BY4741 yeast shifted to water for the indicated times. Data normalized to the mean of the control group at every time point. N = 5 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (b) Polyamine levels of glucose-restricted WT BY4741 after the indicated times. Data normalized to the mean of the control group at every time point. N = 5 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (c) Polyamine levels of young male w1118 flies fasted for 12 or 24 hours (starting at 20:00). Data normalized to the ad libitum group at every time point. Refed = 12 hours refeeding after 24 hours of fasting. N = 7 biologically independent samples (groups of flies). (d) Changes in body weight of young female and male w1118 flies fasted or kept ad lib for the indicated times, starting at 20:00. Data normalized to each ad lib group. P values against each sex’s ad lib group. Refed = 12 hours refeeding after 24 hours of fasting. N = 5(Refed female fasted), 6(24 h female ad lib; Refed female ad lib; Refed male ad lib), 7(12 h, 24 h female fasted; 12 h, 24 h male; Refed male fasted) biologically independent samples (groups of flies). (e) Changes in body weight of young male C57BL/6 mice fasted or kept ad lib for 14-16 hours overnight. N = 6 mice. (f-i) Relative polyamine levels of young male C57BL/6 mice fasted or kept ad lib for 14-16 hours overnight. BAT = brown adipose tissue, WAT = white adipose tissue. FC = fold change to means of ad lib N = 3(ORN Hippocampus; PUT Muscle fasted), 4(PUT WAT fasted), 5(rest) mice. (j) Changes in body weight of young female C57BL/6 mice fasted or kept ad lib for 14-16 hours overnight. N = 8 mice. (k-n) Relative polyamine levels of young female C57BL/6 mice fasted or kept ad lib for 14-16 hours overnight. BAT = brown adipose tissue, WAT = white adipose tissue. FC = fold change to means of ad lib. N = 7(ORN Heart ad lib), 8(rest) mice. (o-q) Relative polyamine levels of male and female C57BL/6 mice kept ad lib or calorie-restricted (30 %), starting at 9 months of age, until the age of 17 or 21 months. (o) N = 4(Fasted Spleen), 6(Fasted Kidney, Serum, Heart; SPM Fasted Liver), 7(Ad lib Spleen; Fasted Muscle, Liver rest), 8(Ad lib Kidney, Liver), 10(Ad lib Serum), 11(Ad lib Heart, Muscle) mice. (p) N = 3(CR Serum SPM), 4(CR Liver, Serum rest), 5(CR Kidney, Spleen), 6(Ad lib Serum; CR Heart, Muscle), 7(), 8(Ad lib Liver, Muscle), 9(Ad lib Kidney, Heart, Spleen) mice. (q)N = 3(Ad lib Liver), 4(Ad lib Kidney, Spleen), 6(Ad lib Serum, Heart, Muscle; CR Kidney, Spleen), 7(CR Heart, Muscle), 8(CR Liver, Serum) mice. (r-s) Polyamine levels in HBSS-starved human U2OS and H4 cells. N = 4 biologically independent samples. (t) Relative mRNA expression levels of polyamine-relevant genes in 6 hours starved U2OS cells. N = 3(ARG1, OAZ1, ODC1, SAT1, ATP13A2, ATP13A3, MYC, YAP, TAZ), 4(SRM, SMS, PAOX, MAT2A, AMD1, GNMT) biologically independent samples. (u) Serum SPD levels after fasting in cohort 1, stratified by sex, depicted as mean with S.E.M and violin plots, showing median and quartiles as lines. N = 67(female), 38(male). (v-x) Serum SPD levels after fasting in cohort 1 do not correlate with age, pre-fasting baseline body mass index (BMI) or body weight loss (body weight ratio). N = 99(Body weight ratio), 102(BMI), 105(Age) volunteers. (y) Relative SPD levels in human plasma from cohort 3 during IF. N = 22(12 h), 23(36 h) volunteers. (z) ODC1 protein levels in human PBMCs after increasing fasting times, measured by capillary electrophoresis. Refeeding = day 3 after re-introduction of food. N = 15(5 d), 16(3d RF), 17(rest) volunteers. Statistics: [A-D,R-S,U,Z] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [E,J,T] Two-tailed Student’s t-tests. [F-I, K-Q] Two-way ANOVA with FDR correction (Two-stage step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, Q = 0.05). [Y] Two-tailed Student’s t-test. [V-X] Simple linear regression analysis. Bar and line graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Heatmaps show means. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, # P < 0.2. Source numerical data are available in source data.

SPD increased in female and male Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) fasted for 24 h (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1c), which caused a body weight loss of 10% and 5%, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1d). This SPD increase was reversed by 12 h re-feeding (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1c). Similarly, young male and female C57BL6/J mice fasted for 14–16 h, which caused significant weight loss (Extended Data Fig. 1e,j), had higher SPD levels (but not PUT nor SPM) in the serum than their ad libitum-fed controls, whereas ORN content was reduced (Fig. 1e). Moreover, the abundance of ORN and polyamines changed significantly in several organs of acutely fasted mice in a tissue-specific manner (Extended Data Fig. 1f–i,k–n), favouring an increase of SPD in multiple tissues. We next asked whether these alterations in polyamine content would also occur during long-term CR, starting at 9 months of age31. We found increased serum SPD at 17 months of age in male, but not female, mice (Extended Data Fig. 1o,p). At later time points (21 months), female CR mice also showed significantly elevated PUT and SPD levels in skeletal muscle (Extended Data Fig. 1q).

Furthermore, starvation elevated SPD and SPM levels uniformly in human U2OS osteosarcoma and H4 glioblastoma cells (Extended Data Fig. 1r,s). Accordingly, in nutrient-depleted U2OS cells, the expression of arginase (ARG1), ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1), spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1) and glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT) increased compared with cells cultured in control medium, whereas the polyamine-associated transcription factors MYC and YAP/TAZ, as well as two recently identified polyamine transporters, ATPase cation transporting 13A2/13A3 (ATP13A2/3), were unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 1t).

In human volunteers, long-term therapeutic fasting with a daily caloric intake of approximately 250 kcal (Supplementary Table 1) under clinical supervision for 7–13 days, SPD levels (but not PUT nor SPM) significantly increased in the serum (Fig. 1f). This increase in SPD content was similarly found in men and women (Extended Data Fig. 1u), and was independent of age and body mass index (BMI) before the intervention or body weight loss (Extended Data Fig. 1v–x).

We analysed an independent cohort of volunteers fasting for variable periods (Supplementary Table 1; cohort 2). SPD levels increased by ~50% after 4–5 days and remained elevated during long-term fasting (Fig. 1g). In a third cohort (Supplementary Table 1), we analysed plasma SPD of individuals who voluntarily followed an IF routine (12-h eating periods followed by 36-h zero-calorie periods for several months). Again, we observed an elevation in SPD levels (Extended Data Fig. 1y). Finally, SPD increased in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of a separate, fourth cohort of volunteers during fasting and reverted to baseline levels after re-feeding (Fig. 1h). Notably, in these PBMCs, ODC1 protein levels decreased during fasting (Extended Data Fig. 1z), suggesting that elevated SPD levels either caused a feedback repression of ODC1 or, at least in these cells, might stem from increased uptake rather than intracellular synthesis.

In conclusion, nutrient starvation (yeast and human cell lines), overnight fasting (flies, mice and humans), long-term CR (mice) or long-term fasting (humans) induced SPD elevation.

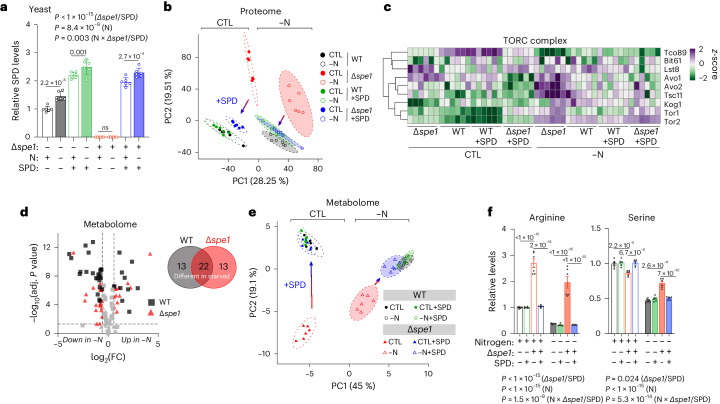

Polyamine synthesis is required for efficient metabolic remodelling and TORC1 inhibition during fasting

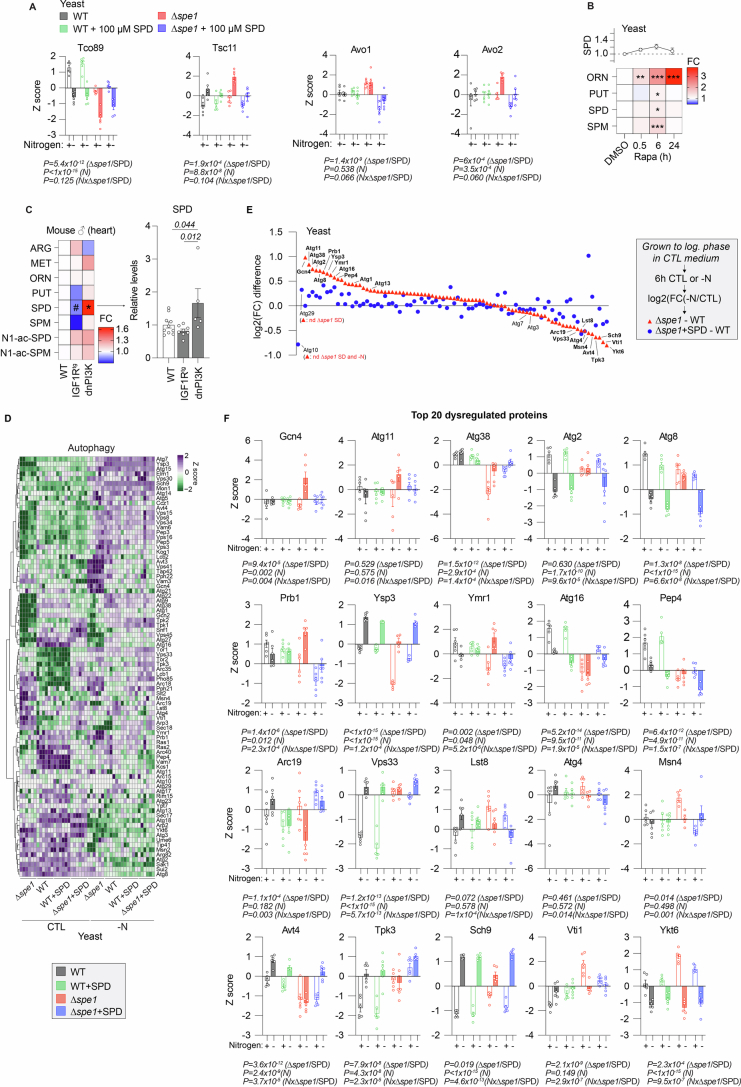

Next, we investigated the cellular consequences of impaired polyamine anabolism on acute fasting responses. We generated yeast lacking the rate-limiting enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1; yeast Spe1), which are characterized by polyamine depletion (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This strain (∆spe1) showed no elevation of polyamines upon starvation, and SPD supplementation (100 µM) fully replenished the intracellular SPD pool (Fig. 2a). We subjected ∆spe1 cells with and without SPD to proteomic analyses after 6 h nitrogen starvation (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Principal-component analysis (PCA) of the proteome revealed a clear distinction between the genotypes and that SPD could revert ∆spe1-associated global differences, whereas it did not affect the wild-type (WT) proteome (Fig. 2b). Mapping the identified proteins to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) terms, we found several pathways that have been implicated in the starvation response dysregulated in ∆spe1 (Supplementary Fig. 1c). This included, for example, the metabolism of several amino acids (including ARG), lipids and fatty acids, as well as energy-relevant pathways (tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation). Notably, we also found a disturbed starvation response of the proteostasis-associated pathways autophagy and TORC1/2, the yeast homologues of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1/2 (mTORC1/2), in ∆spe1 versus WT cells (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Fig. 2. Spermidine synthesis is required for the cellular adaptation to starvation.

a, Relative SPD levels of WT and ∆spe1 yeast cells after SPD treatment (100 µM) and N starvation. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). b, PCA depicting the proteome change in WT and Δspe1 cells under specified condition treatments following a 6-h culture in control or −N medium with or without 100 µM SPD. PCA was performed on a singular-value decomposition of centred and scaled protein groups (n = 4,684) displays a comparison between PC1 and PC2, along with the representation of a 95% confidence interval for each group. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). c, Differential expression (z-score) of proteins involved in the TORC complex, from the proteome analysis shown in b. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). d, Volcano plot showing significantly different intracellular metabolites in WT or ∆spe1 after 6 h −N compared with control conditions. Venn diagram showing exclusive and overlapping significantly regulated metabolites. FDR-corrected P value < 0.05, FC > 1.5. n = 4 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). e, Metabolomic disturbances in ∆spe1 cells are rescued by SPD (100 µM) supplementation. The PCA displays a comparison between PC1 and PC2, along with the representation of a 95% confidence interval for each group. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). f, SPD (100 µM) corrects ∆spe1-associated amino acid disturbances. Relative arginine and serine levels from metabolomics analysis shown in e. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). Statistics were two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (a,f) and two-tailed Student’s t-tests with FDR correction (d). Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data are available in source data.

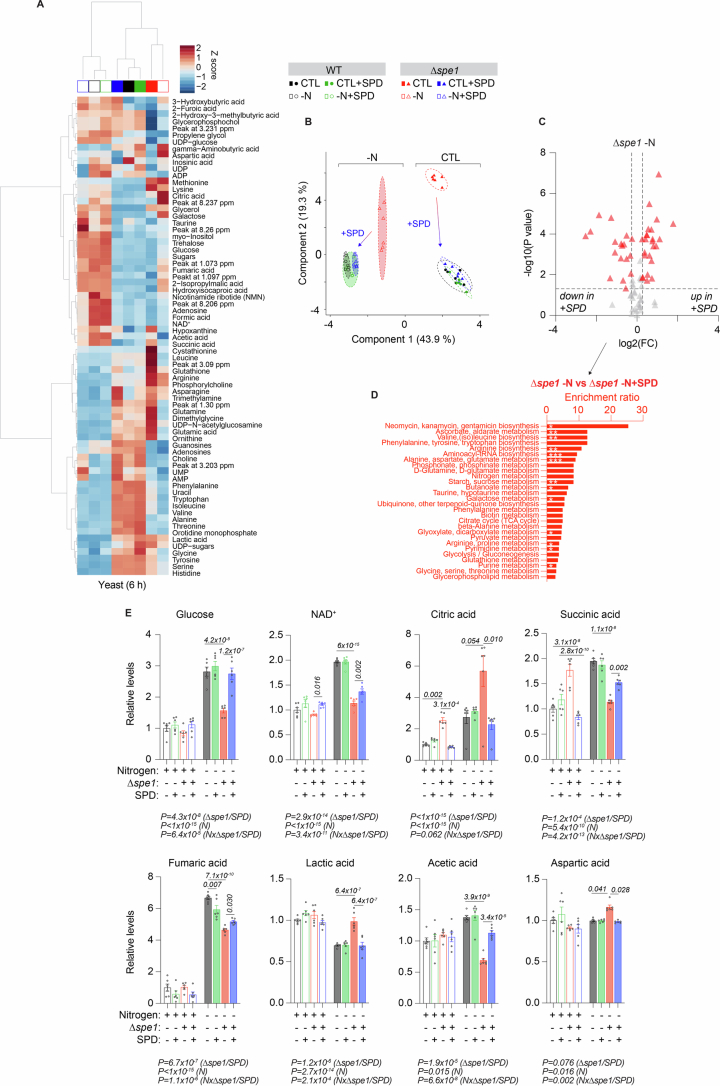

The prominent dysregulation in metabolic pathways was supported by unbiased metabolomic profiling by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, revealing substantial differences in the intracellular metabolomes after nitrogen deprivation (Supplementary Fig. 2). The metabolic disturbances affecting starved ∆spe1 cells (Fig. 2d) confirmed findings from the proteome analysis, including increased citric acid and reduced levels of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and adenosine/guanosine-X-phosphate (AXP/GXP; where X stands for mono-, di- or triphosphate), suggesting a disrupted energy metabolism secondary to the loss of intracellular polyamine synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Our analysis also indicated dysregulated amino acid homoeostasis, which is normally maintained by autophagy in starving yeast32–34.

Notably, exogenously supplemented SPD reversed the metabolic dysregulations in ∆spe1 cells, both in control and nitrogen-starvation medium, whereas it hardly affected the general WT metabolomes (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). This included normalized amino acid metabolism (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 2c,d), which has been critically linked to TOR and autophagy regulation (for example, for arginine35 and serine33) and metabolites central to energy metabolism (glucose, NAD+ and citric acid, among others) (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 2e). Overall, Spe1 was required for the metabolic switch from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation, a key event in the cellular adaptation to nitrogen starvation, which partly depends on functional autophagy36. For instance, glucose levels were less increased under −N, and the ratios of TCA cycle metabolites were heavily dysregulated (for example, citric acid to succinic acid) (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Spermidine supplementation corrects metabolome disturbances in ∆spe1 yeast cells.

(a, b) Heatmap (group means) and PCA of S. cerevisiae WT and ∆spe1 metabolomes after 6 hours -N, with or without 100 µM SPD. Unassigned NMR signals are labelled according to their NMR chemical shift. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (c) Volcano plot showing significantly different metabolites in ∆spe1 after 6 hours -N, with or without 100 µM SPD. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests with FDR-corrected P values < 0.05, FC (fold change) >1.2. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (d) Metabolite set enrichment analysis based on KEGG pathways of significantly different metabolites from [C] (raw P-values < 0.2). (e) Selected metabolites from [A], focusing on amino acid metabolism and the TCA cycle. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). Statistics: [E] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Bar graphs show the mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate raw P-values. *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001. Source numerical data are available in source data.

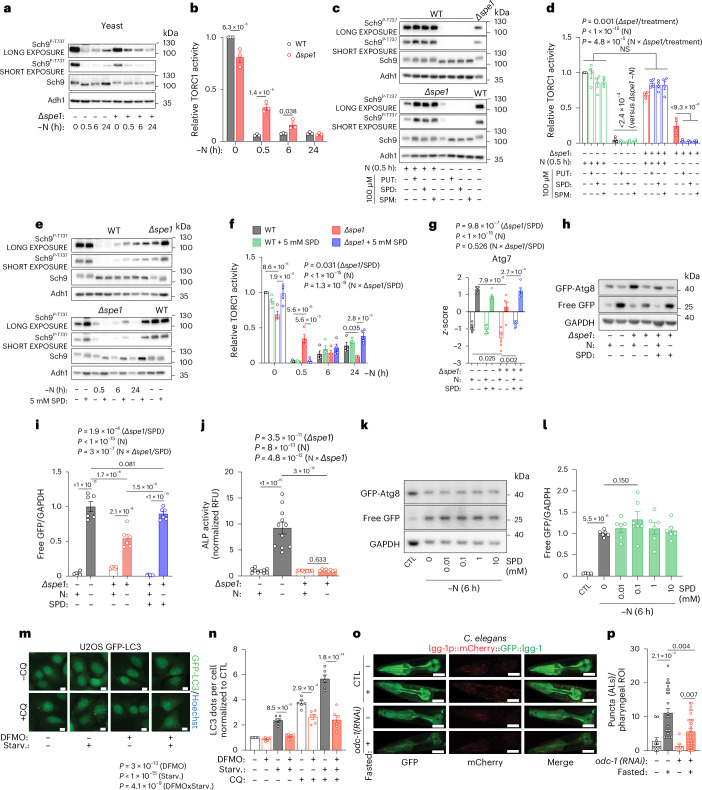

Given the implication of TORC1 in the fasting response of ∆spe1 yeast cells, we next asked whether ∆spe1 cells would functionally alter the nitrogen deprivation-induced inhibition of TORC1. Sch9 (the yeast equivalent of mammalian p70S6K) dephosphorylation, was significantly delayed in ∆spe1 cells (Fig. 3a,b). Focusing on TORC-associated proteins in our proteome data, we found dysregulated TORC subunits, including Tco89, Avo1/2 and Tsc11, under both conditions in the ∆spe1 strain (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Of note, low levels of polyamines (100 µM) completely reverted the delayed TORC1 inhibition in ∆spe1 cells (Fig. 3c,d). On the other hand, high levels of additional SPD (5 mM) did not affect TORC1 activity in the WT strain (Fig. 3e,f). Similar to −N, acute pharmacological inhibition of TORC1 with rapamycin led to a rapid increase of ORN (likely due to the known activation of arginase expression37,38) as well as elevated SPD and SPM levels (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Thus, the efficient shutdown of yeast TOR signalling upon −N, a key event for autophagy induction39, requires intact polyamine metabolism, whereas TOR inhibition promotes the anabolism of polyamines.

Fig. 3. Autophagy induction is blunted by lack of polyamine synthesis.

a, Decrease of TORC1 activity as inferred by Sch9-phosphorylation during -N in WT and ∆spe1 cells. Representative immunoblot. b, Quantification of immunoblots as shown in a. n = 3 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). c, Polyamine supplementation (100 µM) corrects the delayed decrease of TORC1 activity during −N in ∆spe1 cells. Representative immunoblot. d, Quantification of immunoblots as shown in c. n = 4 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). e, Supplementation of high SPD levels (5 mM) corrects the delayed decrease of TORC1 activity in ∆spe1 cells but does not affect TORC1 activity in WT cells. Representative immunoblot. f, Quantification of immunoblots as shown in e. n = 4 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). g, SPD supplementation (100 µM) corrects decreased Atg7 protein levels ∆spe1 cells in both control and −N medium, as detected in proteome analysis shown in Fig. 2b. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). h, Representative immunoblots of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 cells after 6 h −N with and without 100 µM SPD, assessed for GFP and GAPDH. i, Quantifications of h. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). j, ALP activity (RFU per µg) from Pho8∆N60 assay normalized to each CTL group after 6 h −N. n = 10 (WT CTL, ∆spe1 CTL), 11 (WT -N), 8 (∆spe1 −N) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). k, Representative immunoblots of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 after 6 h −N, with or without ascending concentrations of SPD, assessed for GFP and GAPDH. l, Quantifications of k. n = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). m, Representative images of human U2OS GFP-LC3 cells starved for 6 h in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) (with or without chloroquine (CQ) for 3 h before fixation) after 3 days of 100 µM DFMO treatment. For quantifications see also Extended Data Fig. 5c. Scale bar, 10 µm. n, Quantification of cytosolic GFP-LC3 dots from l, normalized to the average number of GFP-LC3 dots in the control condition. n = 6 biologically independent experiments. o, Representative images of the head region of young control and odc-1(RNAi) C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) (LGG-1 is the C. elegans orthologue of LC3) fasted for two days. Autolysosomes (ALs) appear as mCherry-positive puncta. Autophagic activity is indicated by a shift to the red spectrum due to fluorescence quenching of the pH-sensitive-GFP by the acidic environment of the autolysosome. Scale bar, 50 μm. p, Quantification of ALs as depicted in o. Note that the statistics were performed together with additional groups as indicated in Extended Data Fig. 10c. n = 11 (CTL ad lib), 26 (CTL fasted), 8 (Odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 30 (Odc-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. Statistics used were two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (b,d,f,g,h,j,n), one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (l) and Kruskal–Wallis test with FDR correction (two-stage step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, Q = 0.05) (p). Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data. NS, not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Spermidine is required for the correct shutdown of TORC1 and autophagy regulation in N-starving yeast.

(a) Proteome change in S. cerevisiae WT BY4741 and Δspe1 strains under specified condition treatments following a 6-hour culture in control or -N media with or without 100 µM SPD supplementation. Differential expression (Z-score) of proteins involved in the TORC complex, from the proteome analysis. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (b) Polyamine levels of WT BY472 treated with rapamycin (40 nM) for the indicated times. Data normalized to the mean of the DMSO control group at every time point. N = 5 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (c) Polyamine and precursor levels in cardiac tissue of young, male control, transgenic IGF1tg or dnPI3K mice. N = 5(WT), 8(IGF1Rtg), 11(dnPI3K) mice. (d) Yeast WT and Δspe1 strains under specified condition treatments following a 6-hour culture in control or -N media with or without 100 µM SPD. Differential expression (Z-Score) of proteins involved in autophagy, from the proteome analysis in Supplementary Fig. 1c. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (e) Differential regulation of autophagy-relevant proteins in ∆spe1 cells. The averaged log2-transformed fold change (FC) of individual proteins (-N compared to control medium) was calculated for all conditions. The graph depicts the differences of these log2(FC) between ∆spe1 and WT cells (red triangles), as well as ∆spe1 treated with 100 µM SPD and WT cells (blue dots). nd=not detected. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (f) Z-scores of the top 20 dysregulated proteins, as identified in [E]. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). Statistics: [A,B,F] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [C] Two-way ANOVA with FDR correction (Two-stage step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, Q = 0.05). Heatmaps show means. Bar and line graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, # P < 0.2. Source numerical data are available in source data.

To translate these findings in vivo, we measured polyamines and precursors in hearts from young male mice overexpressing the human insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1Rtg)40 or carrying a dominant negative phosphoinositide 3-kinase mutant (dnPI3K)41 specifically in cardiomyocytes. IGF1Rtg causes increased IGF1R signalling, leading to elevated mTOR activity and autophagy inhibition, as well as age-associated heart failure, which can be overridden by SPD42. Conversely, the cardiomyocyte-specific dnPI3K mutation inhibits mTOR and enhances autophagic flux42. We observed a trend towards lower cardiac SPD levels in IGF1Rtg mice (P = 0.222) and significantly elevated levels of SPD in dnPI3K mice (Extended Data Fig. 3c).

Collectively, blocking polyamine synthesis caused a defective cellular response to −N in yeast, thus compromising, inter alia, energy metabolism and amino acid homoeostasis, both of which interface with TOR signalling, an integral hub for sensing and relaying nutrient information to cellular responses and functional autophagy. SPD supplementation reversed the metabolic inflexibility of ∆spe1 cells.

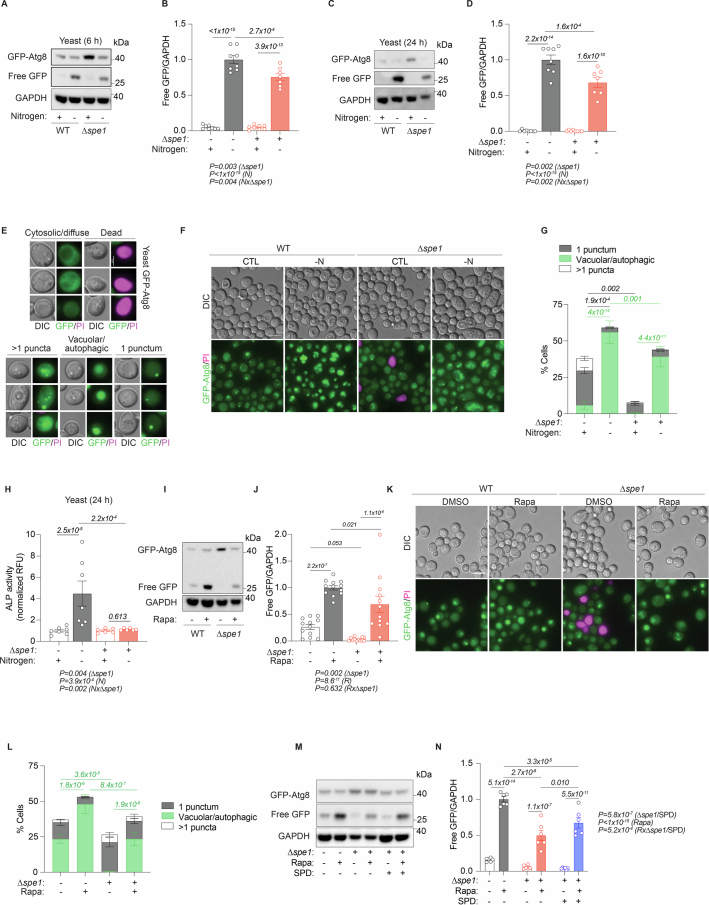

Spermidine is vital for autophagy induction during fasting

mTOR is a major repressor of autophagic flux and proteomics revealed a profound dysregulation of autophagy-relevant proteins upon SPE1 loss (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). SPD has been previously shown to induce ATG7 expression in yeast23, and accordingly, SPE1 knockout caused reduced Atg7 protein expression (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, several autophagy-relevant proteins were differently modulated in the ∆spe1 strain upon −N (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). This included the transcription factors Gcn4 (for amino acid biosynthesis), Msn4 (stress response), several autophagy-related proteins (Atg2/8/11/16/38), as well as vacuolar proteinases (Prb1, Ysp3 and Pep4) and proteins involved in intracellular vesicle trafficking (Vps33, Arc19, Vti1 and Ykt6), among others.

As a functional consequence, ∆spe1 cells exhibited reduced autophagy induction in response to −N. We observed a diminished autophagy-dependent proteolytic liberation of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from GFP fused to autophagy-related protein 8 (GFP-Atg8, Atg8 being the yeast orthologue of the mammalian LC3 family) (Extended Data Fig. 4a–d), which was rescued by SPD supplementation (Fig. 3h,i). This was confirmed with additional autophagy assays, including the reduced redistribution of GFP-Atg8 towards autophagic vacuoles, compared with WT cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e–g) and the Pho8∆N60 assay43 (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 4h). However, supplementing SPD could not further elevate autophagic flux under −N in WT cells (Fig. 3k,l). Similarly, rapamycin-induced autophagy was significantly curtailed in ∆spe1 cells (Extended Data Fig. 4i–l), which again could be partly rescued by SPD (Extended Data Fig. 4m,n).

Extended Data Fig. 4. SPE1, the yeast ODC1 homologue, is required for starvation- and rapamycin-induced autophagy.

(a) Representative immunoblots of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 after 6 hours -N, assessed for GFP and GAPDH. (b) Quantifications of [B]. N = 7(∆spe1 -N), 8 (rest) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (c) Representative immunoblots of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 after 24 hours -N, assessed for GFP and GAPDH. (d) Quantifications of [C]. N = 7(∆spe1 -N), 8(rest) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (e) Representative images of the categories used for categorization of GFP-Atg8 signals as shown and quantified in [F-G]. DIC = differential interference contrast, PI = propidium iodide staining for dead cells. (f) Representative images of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 cells 6 hours after -N. Scale bar = 5 µm. (g) Blinded manual quantification of the autophagic status in microscopy images of WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 cells 6 hours after -N. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (h) ALP activity (RFU/µg) from Pho8∆N60 assay normalized to each CTL group after 24 hours -N. N = 7(WT), 6(∆spe1) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (i) Representative immunoblots of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 after 6 hours rapamycin treatment (40 nM), assessed for GFP and GAPDH. (j) Quantifications of [I]. N = 12 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (k) Representative images of yeast WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 cells 6 hours after rapamycin (40 nM) treatment. Scale bar = 5 µm. (l) Blinded manual quantification of the autophagic status in microscopy images of WT and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 cells 6 hours after rapamycin (40 nM) treatment. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (m) Representative immunoblots of yeast WT BY4742 and ∆spe1 GFP-Atg8 after 6 hours rapamycin treatment (40 nM), with and without 100 µM SPD, assessed for GFP and GAPDH. (n) Quantifications of [M]. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). Statistics: Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

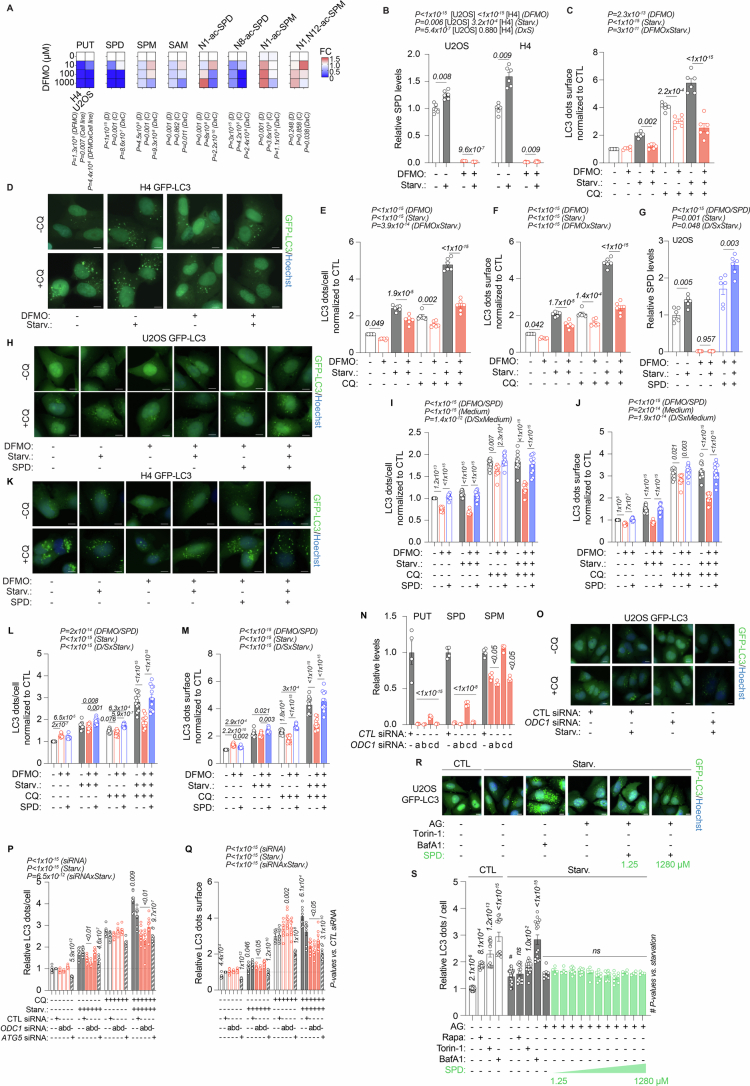

The ODC1 inhibitor difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) depleted polyamines in human U2OS and H4 in nutrient-rich (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and starved (Extended Data Fig. 5b) conditions to <5% of control levels, hence excluding the possibility that ODC1-independent mechanisms (such as uptake of exogenous SPD) would account for the starvation-induced elevation of SPD. DFMO reduced the translocation of GFP–LC3 to autophagosomes and autolysosomes in response to starvation in the presence of the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine (CQ), indicating that polyamine synthesis is required for autophagic flux (Fig. 3m,n and Extended Data Fig. 5c–f). These phenotypes could be rescued by co-treatment with 10 µM SPD (Extended Data Fig. 5g–m). Three siRNAs targeting ODC1 phenocopied the effects of DFMO, hence depleting intracellular polyamines from U2OS cells (Extended Data Fig. 5n) and dampening starvation-induced autophagic flux similar to ATG5 siRNA (Extended Data Fig. 5o–q). As found in yeast, SPD supplementation failed to further enhance autophagy in starved U2OS GFP–LC3 cells (Extended Data Fig. 5r,s). Moreover, mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin or torin-1 induced DFMO-inhibitable autophagy in U2OS and H4 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a–f), which was rescued by SPD (Supplementary Fig. 3g–l).

Extended Data Fig. 5. ODC1 is required for starvation-induced autophagy in H4 and U2OS cells.

(a) DFMO treatment (48 hours, 100 µM) affects the polyamine profile of H4 and U2OS cells in vitro. Polyamine levels normalized to cell line-specific control (0 µM DFMO). N = 5(H4 0, 100 µM DFMO), 4(rest) biologically independent samples. (b) SPD levels in DFMO-treated (48 hours, 100 µM) U2OS and H4 cells after 6 hours starvation. N = 6 biologically independent samples. (c) Quantification of surface area covered by GFP-LC3 dots in 6 hours starved U2OS GFP-LC3 cells treated with or without 100 µM DFMO for 3 days, as depicted in Fig. 3m, normalized to the control condition. N = 6 biologically independent experiments. (d) Representative images of human H4 GFP-LC3 cells starved for 3 hours in HBSS (with or without chloroquine [CQ] for 1.5 hours before fixation) after three days of 100 µM DFMO treatment. Scale bar = 10 µm. (e, f) Quantification of cytosolic GFP-LC3 dots and surface area covered by GFP-LC3 dots from [D], normalized to the control condition. N = 6 biologically independent experiments. (g) SPD levels in U2OS cells treated with DFMO (100 µM) and SPD (10 µM) after 6 hours of starvation. Aminoguanidine (1 mM) was added to all conditions. N = 6 biologically independent samples. (h-j) Representative images and quantifications of human U2OS GFP-LC3 cells starved for 6 hours in HBSS (with or without chloroquine [CQ] for 3 hours before fixation) after three days of 100 µM DFMO treatment in combination with or without 10 µM SPD. Aminoguanidine (1 mM) was added to all conditions. Scale bar = 10 µm. N = 12 biologically independent experiments. (k-m) Representative images and quantifications of human H4 GFP-LC3 cells starved for 3 hours in HBSS (with or without CQ for 1.5 hours before fixation) after three days of 100 µM DFMO treatment in combination with or without 10 µM SPD. Aminoguanidine (1 mM) was added to all conditions. Bar = 10 µm. N = 12 biologically independent experiments. (n) Polyamine levels are depleted 48 hours after ODC1 knockdown via siRNAs in U2OS cells. N = 4 biologically independent samples. (o-q) Representative images and quantifications of human U2OS GFP-LC3 cells starved for 6 hours in HBSS (with or without CQ for 3 hours before fixation) after three days of ODC1 knockdown. Scale bar = 10 µm. N = 8 biologically independent experiments. (r, s) Representative images and quantifications of human U2OS GFP-LC3 cells starved for 6 hours in HBSS or treated with Rapamycin (10 µM) or Torin-1 (300 nM). SPD was added in ascending concentrations to test for synergistic effects with starvation. AG = aminoguanidine (1 mM). N = 4(Starv.+AG + 1.25, 2.5, 320, 640, 1280 µM SPD), 8(Starv.+AG; Starv+AG + 5-160 µM SPD), 16(Rapa, Torin-1, BafA1), 32(CTL) biologically independent samples. Statistics: [A-C,E-G,I-J,L-N,P-Q] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [S] One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test Heatmaps show means. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data are available in source data.

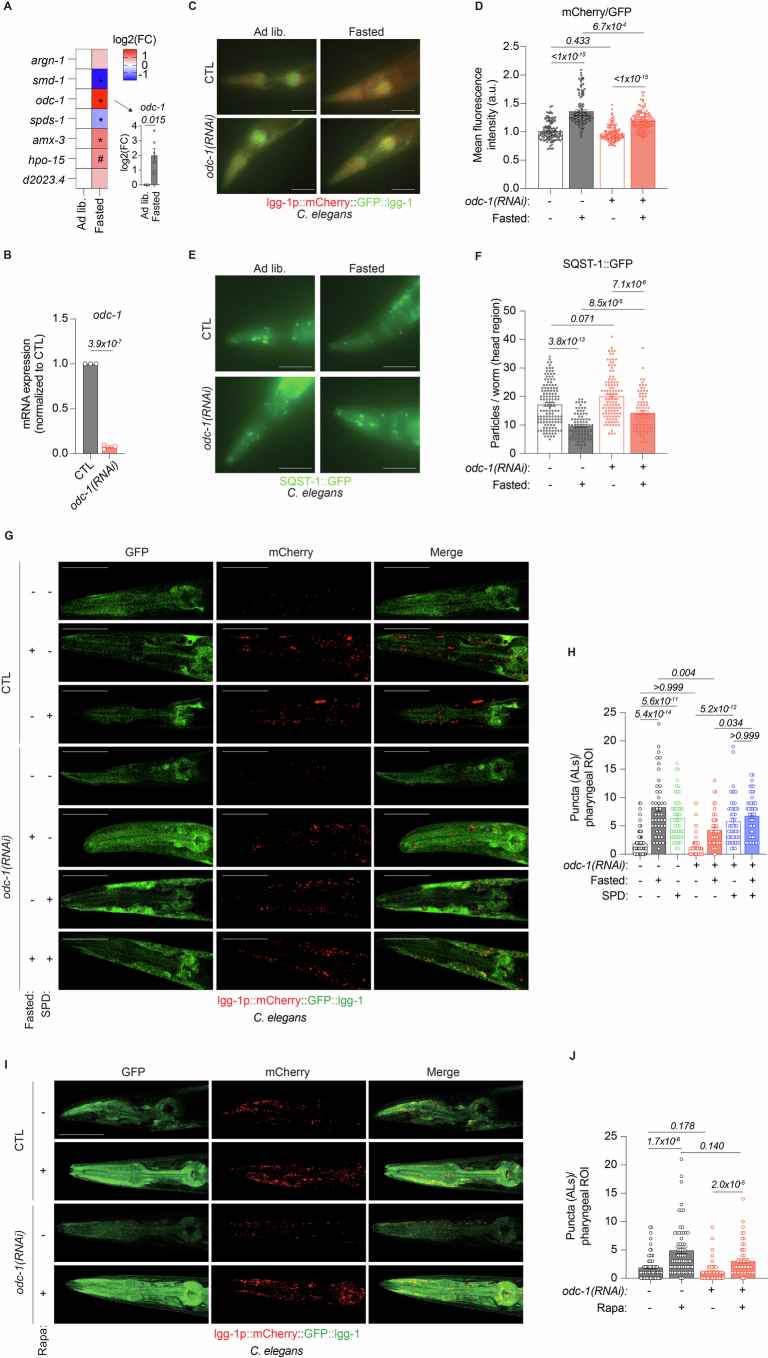

C. elegans subjected to acute fasting exhibited elevated messenger RNA levels of odc-1, amx-3 and hpo-15 (PAOX and SMOX orthologues), whereas spermidine synthase (spds-1) and the AMD1 orthologue smd-1 decreased. Among the tested polyamine-relevant genes, argn-1 (ARG1/2 orthologue) and d2023.4 (SAT1/2) remained unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Knockdown of odc-1 by RNA interference (Extended Data Fig. 6b) reduced fasting-induced autophagic flux assessed by a tandem-tagged (mCherry/GFP) LGG-1 fluorescent reporter, the worm equivalent of yeast Atg8 and human LC3 (Fig. 3o,p and Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). This was confirmed in a strain expressing an alternative autophagy-sensitive biosensor, GFP-fused SQST-1 (the worm orthologue of human sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1)/p62, an autophagy substrate), which was less degraded in fasted odc-1 knockdown worms than in control nematodes (Extended Data Fig. 6e,f). Notably, SPD feeding reverted the autophagic deficit of odc-1 worms (Extended Data Fig. 6g,h). Similar to yeast, odc-1 knockdown also caused a trend (P = 0.140) towards reduced number of rapamycin-induced autolysosomes (Extended Data Fig. 6i,j).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Fasting-induced autophagy in worms requires odc-1.

(a) Relative mRNA expression levels of polyamine-relevant genes in 24 hours fasted C. elegans. N = 4(hpo-15), 5(argn-1, smd-1, amx-3, d2023.4), 6(odc-1, spds-1) biologically independent experiments. (b) Knockdown efficiency of odc-1 mRNA by feeding bacteria expressing odc-1(RNAi) for 3 days in C. elegans. N = 3 biologically independent experiments. (c) Representative fluorescence images of the head region of young C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) fasted for two days and fed control or odc-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria. Autophagic activity is indicated by a shift to the red spectrum due to fluorescence quenching of the pH-sensitive-GFP by the acidic environment of the autolysosome. Scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Quantification of the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity of mCherry/GFP signals, as depicted in [C]. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the dhps-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 10e. N = 121(CTL ad lib), 127(CTL fasted), 113(Odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 125(Odc-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. (e) Representative fluorescence images of the head region of young C. elegans SQST-1::GFP fasted for two days and fed control or odc-1(RNAi). Autophagic activity is indicated by a decrease in the number of GFP-positive particles. Scale bar = 50 μm. (f) Quantification of the SQST-1::GFP particles in the head region, as depicted in [E]. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the dhps-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 10g. N = 133(CTL ad lib), 86(CTL fasted), 109(odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 86(odc-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. (g) Representative images of the head region of young C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) fasted for two days and fed control or odc-1(RNAi) with and without 0.2 mM SPD. Autolysosomes (ALs) appear as mCherry-positive puncta. Scale bar = 50 μm. (h) Quantification of ALs as depicted in [G]. N = 63(CTL), 42(CTL fasted), 52(CTL + SPD), 54(odc-1(RNAi)), 48(odc-1(RNAi) fasted), 50(odc-1(RNAi)+SPD, odc-1(RNAi)+SPD fasted) worms. (i) Representative images of the head region of young C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) with or without 50 µM rapamycin and fed control or odc-1(RNAi). Autolysosomes (ALs) appear as mCherry-positive puncta. Scale bar = 50 μm. (j) Quantification of ALs as depicted in [I]. N = 63(CTL), 62(CTL+Rapa), 54(odc-1(RNAi)), 53(odc-1(RNAi)+Rapa) worms. Statistics: [A] Mann-Whitney with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [B] Two-tailed Student’s t-test. [D,F,H,J] Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Heatmaps show means. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05, # P < 0.2. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Altogether, these findings indicate that ODC1 is required for optimal fasting-induced autophagy across species.

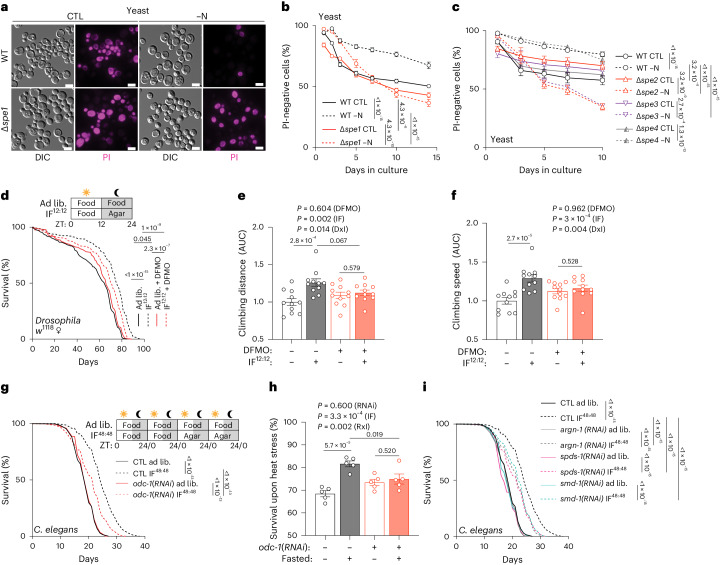

Spermidine is required for fasting-mediated lifespan extension

Nitrogen deprivation reduces the fraction of dead cells in chronological aging experiments performed on yeast, a model for post-mitotic aging44, in an autophagy-dependent manner45. This longevity-extending effect was abolished in ∆spe1 cells, indicating that polyamine synthesis is required for longevity upon −N (Fig. 4a,b). The knockout of spermidine synthase (∆spe3) and that of SAM decarboxylase (∆spe2), which are both required for SPD generation, phenocopied ∆spe1 with respect to the loss of the longevity during −N (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the knockout of spermine synthase (∆spe4) failed to affect survival under nitrogen-deprived conditions (Fig. 4c). Of note, survival deficits triggered by the loss of Spe1 could be fully rescued by the addition of PUT, SPD or SPM (P > 0.05 against each other under nitrogen starvation) (Supplementary Fig. 4b). However, increasing concentrations of SPD only improved the nitrogen starvation-prolonged chronological lifespan of WT cells on early time points (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. Intermittent fasting-mediated lifespan extension depends on SPD synthesis.

a, Representative microscopy images on day 5 of chronological lifespan experiments of yeast WT and ∆spe1 in control and −N medium, stained with propidium iodide (PI). Scale bar, 5 µm. b, PI-negative (live) cells during chronological aging of yeast WT and ∆spe1 in control and −N medium. n = 36 (WT), 26 (∆spe1 CTL), 24 (∆spe1 −N) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). c, PI-negative (live) cells during chronological aging yeast WT and ∆spe2, ∆spe3 and ∆spe4 cells grown to the log phase and shifted to CTL or −N. n = 8 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). d, Lifespan of female w1118 flies fed standard food with or without 10 mM DFMO and subjected to IF12:12. n = 315 (ad lib), 313 (IF), 327 (ad lib + DFMO), 348 (IF + DFMO) flies. e, Flies from d were assessed for their climbing ability, measured as covered walking distance after a negative geotaxis stimulus, between days 53–60. n = 11 biologically independent samples. f, Flies from d were assessed for their climbing ability, measured as speed after a negative geotaxis stimulus, between days 53–60. n = 11 biologically independent samples. g, Lifespan of C. elegans N2 fed control (CTL) or odc-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria during IF48:48. The worms were transferred every other day. IF groups were transferred to agar plates without bacteria every second day. Note that the statistics and experiments were performed together with the groups depicted in i and Fig. 6p. n = 913 (CTL ad lib), 750 (CTL IF), 794 (odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 779 (odc-1(RNAi) IF) worms. h, The susceptibility of worms to heat stress is reduced by IF48:48 in control, but not in worms fed odc-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria. Young worms (after the first round of fasting) were placed at 37 °C for 6 h. Survival was assessed after overnight recovery at 20 °C. n = 5 biologically independent experiments. i, Lifespan of C. elegans N2 fed bacteria expression control (CTL) or RNAi against argn-1, spds-1 or smd-1 during IF48:48. Note that the experiments and statistics were performed together with the groups depicted in g and Fig. 6p. n = 913 (CTL ad lib), 750 (CTL IF), 899 (argn-1(RNAi) ad lib), 797 (argn-1(RNAi) IF), 820 (smd-1(RNAi) ad lib), 803 (smd-1(RNAi) IF), 881 (spds-1(RNAi) ad lib), 746 (spds-1(RNAi) IF) worms. Statistics used were two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (b,c,e,f,h) and log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (d,g,i). Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data are available in source data. AUC, area under the curve.

We next investigated the involvement of SPE1 in other lifespan-increasing interventions in yeast. Inhibition of TOR with rapamycin extends yeast lifespan in an autophagy-dependent fashion46,47, and this effect was diminished in the ∆spe1 strain (Supplementary Fig. 4d) but rescued by polyamine supplementation (Supplementary Fig. 4e). The extension of chronological lifespan by glucose restriction was partially compromised by the spe1 knockout (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Replicative aging, which reflects the diminished replicative capacity of aging mother cells44, is especially responsive to glucose restriction. Knockout of SPE1 diminished the survival, median (WT 23 versus ∆spe1 19 days) and maximal replicative lifespan (68 versus 44 days) in low-glucose (0.05%) cultures but did not affect replicative lifespan when glucose concentrations were kept at standard levels (2%) (Supplementary Fig. 4g). In summary, SPE1 and SPD are essential for longevity induction by nitrogen starvation, rapamycin and glucose depletion.

Testing these findings’ relevance, we subjected fruit flies to an IF regime that improves healthspan and lifespan. We followed the survival of female and male w1118 flies under IF12:12, during which increased daytime food intake compensated for the nightly calorie loss after 10 cycles and at later time points (Extended Data Fig. 7a). DFMO lowered whole-body SPD levels (Extended Data Fig. 7b) and reduced the effects of IF12:12 on improved survival in both sexes (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 7c, Supplementary Table 2). Generally, IF12:12 seemed more effective in female flies, which we further tested for age-sensitive locomotor capacity with a modified negative geotaxis assay. DFMO prevented locomotion improvement by IF12:12 (Fig. 4e,f). Of note, DFMO did not affect food consumption during the first cycles of IF12:12 (Extended Data Fig. 7d) or body weight during acute fasting (Extended Data Fig. 7e) and generally seemed to be non-toxic for flies. Female flies lacking one functional copy of Odc1 (Odc1MI10996 mutant) were also unresponsive to IF12:12, and nightly SPD feeding could re-instate IF12:12-mediated longevity in such flies (Extended Data Fig. 7f and Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Polyamine synthesis is important for IF-induced benefits in flies and worms.

(a) Daily and nightly food consumption of D. melanogaster w1118 after 10, 30 and 50 days of IF12:12. N = 11(Day 30 IF Day), 12(Day 30 Ad lib), 16(Day 50 Ad lib Night), 18(Day 10), 20(Day 50 IF Day), 22(Day 50 Ad lib Day) biologically independent samples (groups of flies). (b) DFMO feeding affects the polyamine profile of female w1118 flies during ad lib and 24 hours fasting. N = 6(Ad lib 10 µM DFMO; Fasted 0, 10 µM DFMO), 7(Ad lib 0, 0.1, 1 µM DFMO; Fasted 0.1, 1 µM DFMO) biologically independent samples (groups of flies). (c) Lifespan of male w1118 flies fed standard food with or without 10 mM DFMO and subjected to IF. N = 210(Ad lib), 206(IF), 199(Ad lib+DFMO), 212(IF + DFMO) flies. (d) Food consumption of 10-day old female and male w1118 flies, fed control or food containing 10 mM DFMO, during the first 7 cycles of IF. N = 8(0 mM Day IF), 9(rest) biologically independent samples (groups of 5 flies per N). (e) DFMO feeding does not influence body weight changes after 24 hours fasting. N = 7 biologically independent samples (groups of flies). (f) Lifespan of heterozygous Odc1MI10996/+ flies subjected to IF. The IF + SPD group received 5 mM SPD via agar during the night. N = 119(Odc1MI10996/+ ad lib), 117(Odc1MI10996/+ IF), 113(Odc1MI10996/+ IF + SPD) worms. (g) Knockdown of odc-1 does not affect worm size under ad lib or IF48:48 conditions, compared to CTL RNAi. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the dhps-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 10h. N = 56(CTL ad lib), 66(CTL IF), 63(Odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 78(Odc-1(RNAi) IF) worms. (h) Knockdown efficiency of respective mRNAs by feeding bacteria expressing argn-1, spds-1, or smd-1 RNAi in C. elegans. N = 2(argn-1, smd-1), 3(spds-1) biologically independent experiments. (i) Lifespan of C. elegans N2 fed control (CTL) or RNAi against odc-1, with or without continuous 0.2 mM SPD feeding during IF. Note that the experiments and statistics were performed together with the groups depicted in [J]. N = 429(CTL ad lib), 523(CTL IF), 437(CTL ad lib+SPD),466(IF + SPD), 330(odc-1(RNAi) ad lib), 575(odc-1(RNAi) IF), 497(odc-1(RNAi) ad lib+SPD), 605(odc-1(RNAi) IF + SPD) worms. (j) Lifespan under 50 µM rapamycin treatment of C. elegans N2 fed control (CTL) or RNAi against odc-1. Note that the experiments and statistics were performed together with the groups depicted in [I]. N = 429(CTL), 423(Rapa), 330(odc-1(RNAi), 330(odc-1(RNAi) Rapa) worms. Statistics: [A,D] Two-tailed Student’s t-test (per time point). [B,E,G] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [F,I,J] Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. [H] Two-tailed Student’s t-test. Heatmaps show means. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data are available in source data.

In C. elegans, genetic inhibition of odc-1 reduced the lifespan extension (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Table 2) and heat stress resistance (Fig. 4h) conferred by IF48:48, but did not affect the body size of fasted worms (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Knockdown of spds-1 (spermidine synthase) or smd-1 (adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1), which are critical for SPD synthesis, as well as argn-1 (Extended Data Fig. 7h) reduced the lifespan extension elicited by IF48:48 in worms (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Table 2). Notably, SPD significantly extended the lifespan of intermittently fasted odc-1 knockdown worms towards that of WT controls (Extended Data Fig. 7i and Supplementary Table 2). However, SPD did not modulate the IF48:48 effect on the lifespan of WT worms and was less potent than IF alone when fed ad libitum (Extended Data Fig. 7i and Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, rapamycin-triggered longevity was blunted upon odc-1 knockdown in worms (Extended Data Fig. 7j and Supplementary Table 2).

Altogether, these findings unravel a pathway in which endogenous polyamine biosynthesis mediates the lifespan-extending effects of nitrogen starvation in yeast and IF in flies and worms.

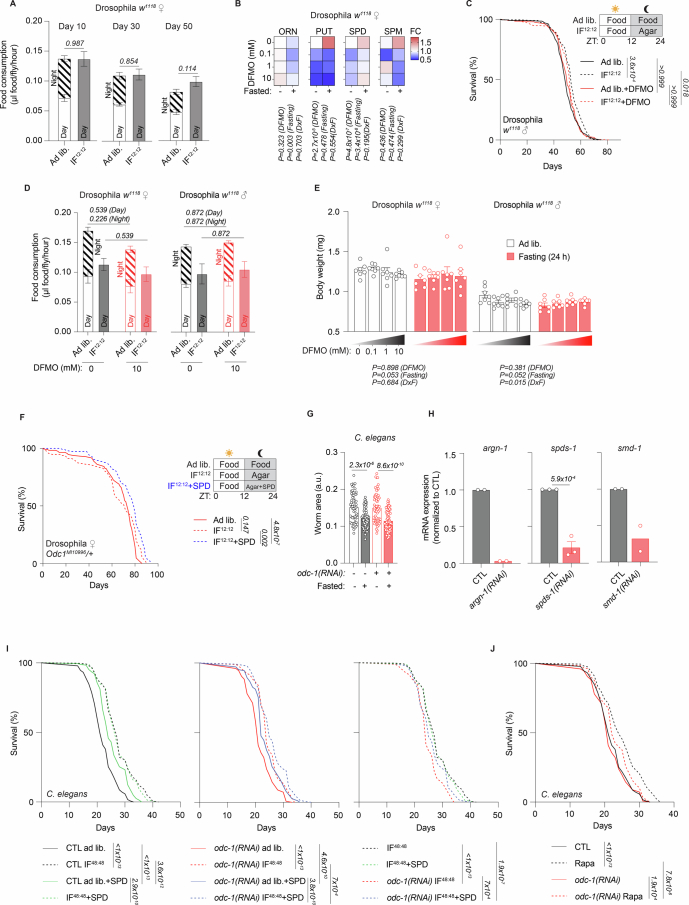

Cardioprotective and antiarthritic effects of intermittent fasting are blunted by DFMO feeding in mice

We next determined whether endogenous SPD biosynthesis in mice was essential for IF-induced healthspan improvements, focusing on cardioprotection and suppression of inflammation, knowing that both are elicited by SPD supplementation24,48.

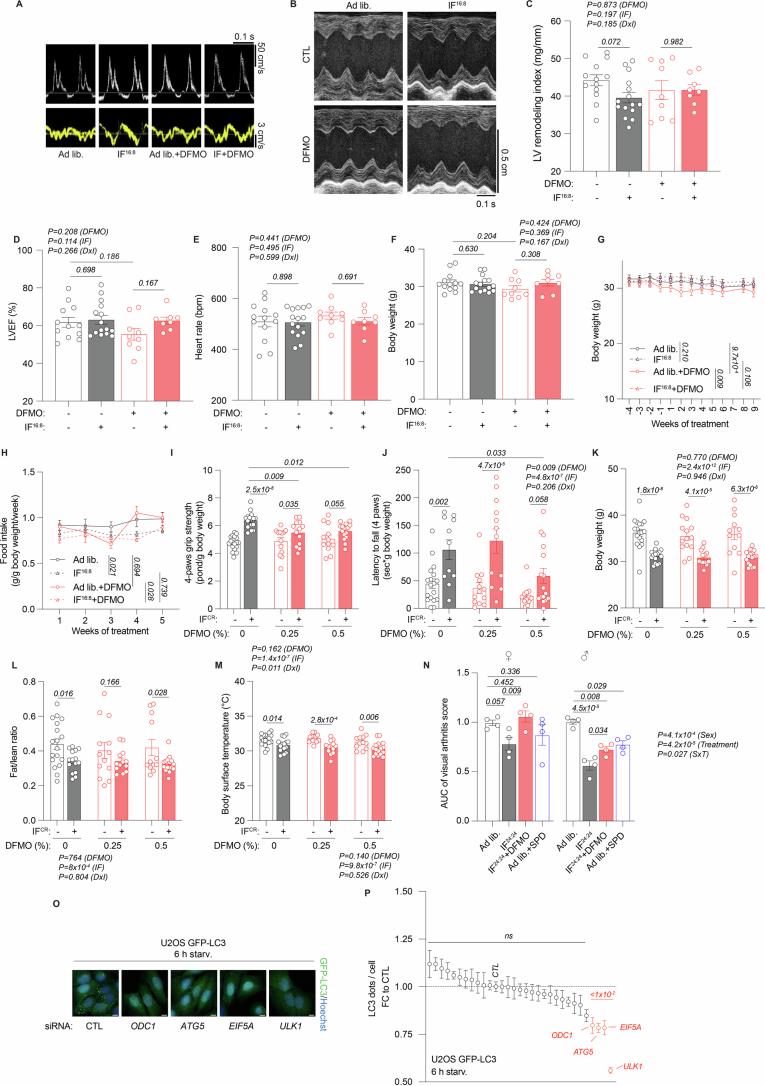

In aged male mice, DFMO abolished favourable cardiac effects of an IF16:8 protocol (daily 16 h fasting and 8 h ad libitum food access during the light phase) (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). This concerned improvements in cardinal signs of cardiac aging49, including left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction (E/e′) (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 3; P = 0.042, ad libitum versus IF), LV hypertrophy (Fig. 5c; P = 0.043) and LV remodelling index (P = 0.072) (Extended Data Fig. 8c and Supplementary Table 3), whereas other cardiac parameters remained unaffected by DFMO and IF16:8 (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e and Supplementary Table 3). DFMO did not alter the IF16:8-induced reduction of body weight and food intake (Extended Data Fig. 8f–h). In a second cohort of aged male mice, we tested the effects of DFMO on general and muscular healthspan improvements elicited by an IF + CR (30%) combination (IFCR; one meal a day, provided shortly before the dark phase) (Fig. 5d)50. DFMO prevented IFCR-mediated improvements in a visual frailty index51 (Fig. 5e), grip strength (Fig. 5f and Extended Data Fig. 8i) and wire hanging ability (Extended Data Fig. 8j), whereas it did not affect body weight (Extended Data Fig. 8k), body composition (Extended Data Fig. 8l) or body surface temperature (Extended Data Fig. 8m). Additionally, in young mice, both IF24:24 and oral SPD supplementation (Fig. 5g) ameliorated the progression of autoantibody-induced arthritis, and the antiarthritic effects of IF24:24 were blunted by parallel DFMO administration (Fig. 5h,i), with comparable results in female and male mice (Extended Data Fig. 8n).

Fig. 5. DFMO blunts the healthspan-promoting effects of IF in mice.

a, Experimental layout to study the effects of DFMO feeding on IF16:8-mediated cardioprotection in 17–18-month-old male C57BL/6J mice. Mice were fasted from 15:00 to 7:00 (16 h daily, excluding weekends). A subset of aged mice received DFMO in the drinking water. After 10 weeks, cardiac function and structure were assessed by echocardiography. Data are shown in b,c, Extended Data Fig. 8a–h and Supplementary Table 3. b, Ratio of peak early Doppler transmitral flow velocity (E) to myocardial tissue Doppler velocity (e′), a measure of diastolic dysfunction, in aged male mice treated with IF16:8, with or without DFMO (n = 13, 15, 9 and 8 mice per group, respectively). c, LV mass normalized to body surface area (LV massi). n = 13 (ad lib), 15 (IF), 9 (ad lib + DFMO), 8 (IF + DFMO) mice. d, Experimental layout to study the effects of DFMO feeding on IFCR-mediated healthspan improvements in 20-month-old male C57BL/6J mice. Mice were given a single meal per day (30% CR) shortly before the dark phase. A subset of mice received 0.25% or 0.5% DFMO in the drinking water. After 3 months, healthspan was assessed. Data are shown in e,f and Extended Data Fig. 8i–m. e, Visual frailty index of aged male mice treated with IFCR, with or without DFMO. n = 12 (ad lib 0.5%), 13 (IF 0.25%), 14 (ad lib 0.25%), 15 (IF 0%), 16 (IF 0.5%), 18 (ad lib 0%) mice. f, Grip strength of fore limbs in gram-force (gf) normalized to body weight of aged male mice treated with IFCR, with or without DFMO. n = 12 (ad lib 0.5%), 13 (IF 0.25%), 14 (ad lib 0.25%), 15 (IF 0%), 16 (IF 0.5%), 18 (ad lib 0%) mice. g, Experimental layout to study the effects of DFMO feeding on IF-mediated anti-inflammatory effects in young BALB/cJRj mice of both sexes. DFMO and 3 mM SPD were supplemented via drinking water. Mice were fasted every other day. IF24:24 and SPD treatments were started 3 weeks before serum transfer and continued until the end of the experiment. Data are shown in h,i and Extended Data Fig. 8n. h, Development of arthritis upon injection of serum from K/BxN mice in young male and female BALB/cJRj mice treated as outlined in g. n = 8 mice. i, AUC analysis of h. n = 8 mice. Statistics used were two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (b,c,e,f), log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (c,e) and one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (i). Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. M, months of age. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Cardiac profiling by echocardiography of aging mice during IF, with and without DFMO.

(a) Representative echocardiography-derived mitral pulsed wave and tissue Doppler tracings in aged mice treated as outlined in Fig. 5a. (b) Representative echocardiography derived left ventricular (LV) M-mode tracings. (c) LV remodelling index. N = 13(Ad lib), 15(IF), 9(Ad lib + DFMO), 8(IF + DFMO) mice. (d) LV ejection fraction (LVEF). N = 12(Ad lib), 15(IF), 9(Ad lib + DFMO), 8(IF + DFMO) mice. (e) Heart rate. N = 13(Ad lib), 15(IF), 9(Ad lib + DFMO), 8(IF + DFMO) mice. (f) Body weight at the time of cardiac profiling. N = 13(Ad lib), 15(IF), 9(Ad lib + DFMO), 8(IF + DFMO) mice. (g) Body weight throughout the intervention. N = 15(Ad lib; Ad lib + DFMO),16(IF; IF + DFMO IF) mice (at week 0). (h) Food intake per mouse throughout the intervention. N = 3(Week 4 IF + DFMO), 4(rest) cages. (i) Grip strength (all limbs) normalized to body weight. N = 18(CTL ad lib), 15(CTL IF), 13(0.25% DFMO), 12(0.5% DFMO ad lib), 16(0.5% DFMO IF) mice. (j) Latency to fall in a 4-limb grid hanging test. N = 18(CTL ad lib), 11(CTL IF), 13(0.25% DFMO ad lib), 12(0.25% DFMO IF), 12(0.5% DFMO ad lib), 16(0.5% DFMO IF) mice. (k) Body weight. N = 18(CTL ad lib), 15(CTL IF), 14(0.25% DFMO ad lib), 13(0.25% DFMO IF), 12(0.5% DFMO ad lib), 16(0.5% DFMO IF) mice. (l) Fat-to-lean mass ratio. N = 18(CTL ad lib), 15(CTL IF), 13(0.25% DFMO), 12(0.5% DFMO ad lib), 16(0.5% DFMO IF) mice. (m) Abdominal surface temperature. N = 18(CTL ad lib), 15(CTL IF), 14(0.25% DFMO ad lib), 13(0.25% DFMO IF), 12(0.5% DFMO ad lib), 16(0.5% DFMO IF) mice. (n) Sex-stratified arthritis scoring of data presented in Fig. 5h-i upon injection of serum from K/BxN mice in young male and female BALB/cJRj mice treated as outlined in Fig. 5g. N = 4 mice. (o) Genes previously connected to the cellular effects of SPD were knocked out via siRNAs in U2OS GFP-LC3 cells and tested for starvation-induced autophagy. Selected representative images after 6 hours of starvation. (p) 48 hours after siRNA knockdown, U2OS GFP-LC3 cells were starved for 6 hours. The graph depicts the normalized individual FC to control conditions of GFP-LC3 dots for every gene knockdown or control condition (means ± S.E.M.). FC 1 represents the starvation-induced increase in GFP-LC3 dots in the control condition. Highlighted genes were significantly different from the control. N = 17(CTL), (Dharmafect control), 9(rest) biologically independent samples. Statistics: [C-N] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [P] One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Line graph shows the mean ± s.e.m. Bar and line graphs show the mean ± S.E.M. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Collectively, genetic or pharmacologic ODC1 inhibition attenuated or abolished the healthspan-promoting, cardioprotective and inflammation-regulating effects of IF regimens in multiple distantly related species. Therefore, SPD is probably a dominant pro-autophagic and anti-aging effector metabolite accounting for the beneficial effects of various forms of IF.

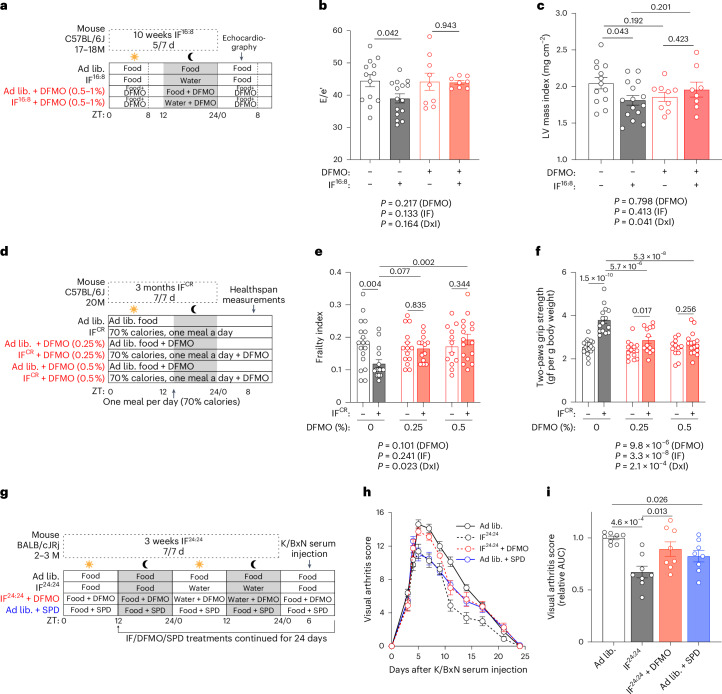

Increased eIF5A hypusination is required for fasting-induced longevity

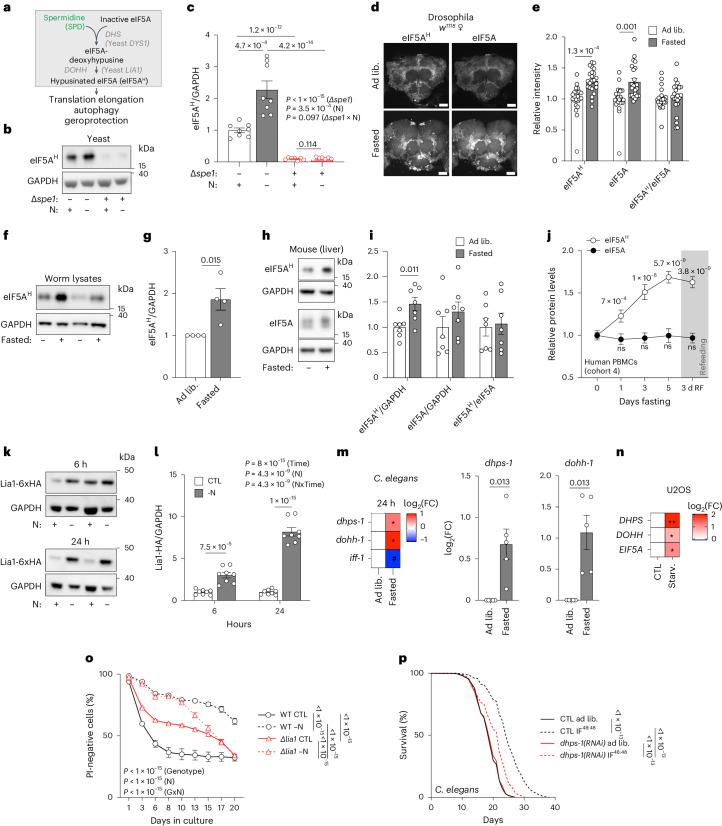

U2OS GFP–LC3 cells were screened for the effects of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting genes previously linked to SPD effects that hence might modulate starvation-induced autophagy. Besides the knockdown of ODC1 and the autophagy-essential genes ATG5 and ULK1, we found that depletion of EIF5A (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A) significantly reduced the number of GFP–LC3 dots after starvation (Extended Data Fig. 8o,p). SPD is required to hypusinate eIF5A via a conserved reaction involving deoxyhypusine synthase (DHS) and deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (DOHH)52. The resulting covalently modified and active hypusinated eIF5A (eIF5AH) is involved in the pro-autophagic and antiaging effects of SPD administration53,54 (Fig. 6a). We thus investigated whether the polyamine–eIF5AH axis played a role in autophagy and lifespan regulation during −N and IF.

Fig. 6. Hypusination of eIF5A acts downstream of spermidine to mediate IF-associated longevity.

a, Scheme of the hypusination pathway. DHS, deoxyhypusine synthase; DOHH, deoxyhypusine hydroxylase; eIF5A, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1. b, Representative immunoblot of hypusinated eIF5A (eIF5AH) levels in yeast GFP-Atg8 WT and ∆spe1 after 6 h of −N. c, Quantification of b. n = 8(WT), 7(∆spe1) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). d, Representative maximum projection images of confocal microscopy images of female w1118 fly central brain regions probed for eIF5A and hypusine by immunofluorescence. Before dissection, the flies were fasted for 0 h (ad lib) or 12 h, starting at 20:00. Scale bar, 50 µm. e, Quantification of signal intensities in d. n = 22 (ad lib), 23 (fasted) fly brains. f, Immunoblots of 48 h fasted C. elegans assessed for hypusine and GAPDH. g, Quantification of f. n = 4 biologically independent samples (worm lysates). h, Representative immunoblot of eIF5AH, eIF5A and GAPDH signals of liver samples from ad lib and fasted (14–16 h) young, male C57BL/6 mice. i, Quantification of h. n = 7 mice. j, eIF5AH and total eIF5A levels in human PBMCs after increasing fasting times, measured by capillary immunoblotting. RF, 3 days after re-introduction of food. n = 17 (days 0, 1 and 3), 15 (day 5), 16 (day 7 and RF) volunteers. k, Representative immunoblot of yeast Lia1-6xHA, assessed for HA-tags and GAPDH after 6 and 24 h −N. l, Quantification of Lia1-6xHA levels as depicted in k. n = 8 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). m, Quantification of relative mRNA expression of dhps-1, dohh-1 and iff-1 in 24 h fasted C. elegans. n = 3 (iff-1), 5 (dhps-1 and dohh-1) biologically independent experiments. n, Quantification of relative mRNA expression of DHPS, DOHH and EIF5A in 6 h starved U2OS cells. n = 3 (DOHH), 4 (DHPS and EIF5A) biologically independent experiments. o, PI-negative (live) yeast cells during chronological lifespan analysis of WT and ∆lia1 yeast in control and −N medium. n = 12 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). p, Lifespan of C. elegans N2 fed control (CTL) or dhps-1(RNAi) (homologue of DHS) expressing bacteria during IF48:48. Note that the experiments and statistics were performed together with the groups depicted in Fig. 4g,i. n = 913 (CTL ad lib), 750 (CTL IF), 862 (dhps-1(RNAi) ad lib), 776 (dhps-1(RNAi) IF) worms. Statistics used were two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (c,j,l,o), two-tailed Student’s t-tests with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (e,i,m,n), two-tailed Student’s t-test (h) and log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (p). Bar and line graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

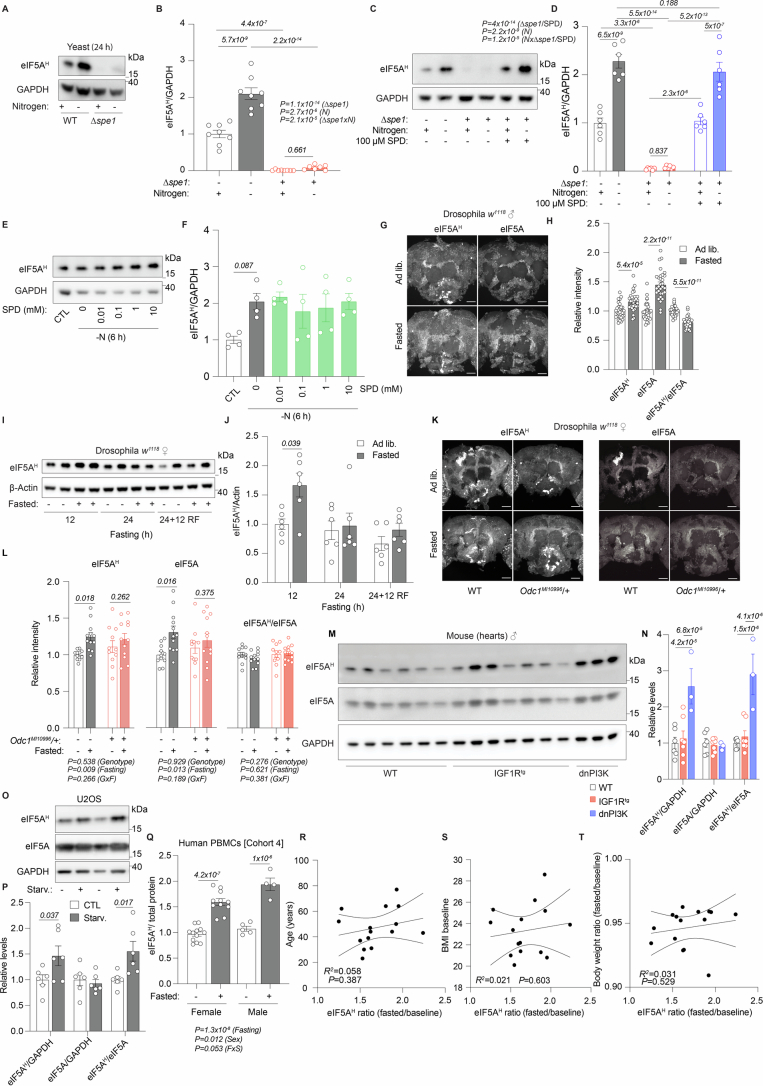

Nitrogen deprivation of yeast enhanced eIF5AH (Hyp2 in yeast) in a Spe1-dependent fashion (Fig. 6b,c and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). The hypusination defect observed in Spe1-deficient cells was reversed by SPD (Extended Data Fig. 9c,d), which had no additional impact on hypusine levels in starved WT cells (Extended Data Fig. 9e,f).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Fasting increases hypusination of eIF5A.

(a) Hypusine levels are increased after 24 hours -N in yeast BY4741 GFP-Atg8 cells, but not in ∆spe1. Representative immunoblot. (b) Quantification of [A]. N = 7(∆spe1 -N), 8(rest) biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (c) Representative immunoblot of WT and ∆spe1, with and without 100 µM SPD after 6 hours -N, assessed for hypusine and GAPDH. (d) Quantification of [C]. N = 6 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (e) SPD supplementation does not further increase hypusination in BY4741 GFP-Atg8 yeast. Representative immunoblot. (f) Quantification of [E]. N = 4 biologically independent samples (yeast cultures). (g) Representative maximum projection images of confocal microscopy images of male w1118 fly central brain regions probed for eIF5A and hypusine by immunofluorescence. Prior to dissection, the flies were fasted for 0 (ad lib) or 12 hours, starting at 8 pm. Scale bar = 50 µm. (h) Quantification of signal intensities as shown in [G]. N = 30 fly brains. (i) Representative immunoblot of female Drosophila w1118 head extracts, assessed for hypusine and actin after 12 and 24 hours overnight fasting. RF = 12 hours refeeding. (j) Quantification of [I]. N = 6 biologically independent samples (fly head lysates). (k) Representative immunostaining microscopy images against hypusine after 12 hours fasting of female WT w1118 and Odc1MI10996/+ fly brains. Scale bar = 50 µm. (l) Quantification of [K]. N = 11(ad lib), 12(fasted) fly brains. (m) Immunoblots of cardiac tissue from young male transgenic IGF1Rtg or dnPI3K mice and their age-matched WT controls. Heart lysates were assessed for hypusine, total eIF5A and GAPDH. (n) Quantification of [M]. N = 6(WT), 7(IGF1Rtg), 3(dnPI3K) mice. (o) Representative immunoblot of human U2OS cells starved for 6 hours and assessed for hypusine, total eIF5A and GAPDH. (p) Quantification of [O]. N = 6 biologically independent samples. (q) Hypusine levels after five days of fasting in isolated human PBMCs of cohort 4, stratified by sex. N = 12(female baseline), 11(female fasted), 5 (male baseline), 4(male fasted) volunteers. (r-t) eIF5AH levels after five days of fasting in isolated human PBMCs of cohort 4 do not correlate with age, pre-fasting baseline BMI or body weight loss (body weight ratio). N = 15 volunteers. Statistics: [B,D,L,NP,Q] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [F] One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [H,J] Two-tailed Student’s t-test with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. [R-T] Simple linear regression. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

Similarly, immunostaining of brains revealed increased eIF5AH and total eIF5A in female and male flies after 12 h fasting (Fig. 6d,e and Extended Data Fig. 9g,h), as confirmed by immunoblotting of whole-head lysates from female flies (Extended Data Fig. 9i,j). Notably, female heterozygous Odc1MI10996 mutants, which failed to show lifespan extension upon IF12:12, also lost their eIF5AH fasting response (Extended Data Fig. 9k,l).

We also found elevated eIF5AH in lysates from fasted worms (Fig. 6f,g) and livers from fasted male mice (Fig. 6h,i). Of note, dnPI3K hearts, which had increased SPD levels, showed highly upregulated eIF5AH levels, while the IGF1Rtg mutation caused no alterations in eIF5AH or SPD levels (Extended Data Fig. 9m,n).

Increased eIF5AH, but not total eIF5A, levels were similarly detected in starved human U2OS cells (Extended Data Fig. 9o,p), as well as in PBMCs from healthy human volunteers over several days of fasting, which persisted after food re-introduction (Fig. 6j). Fasting enhanced eIF5AH indistinguishably in male and female volunteers, and this effect was not affected by age, BMI or weight loss (Extended Data Fig. 9q–t).

We next explored the mechanisms of increased eIF5AH levels. In yeast, protein levels of Dys1 (DHS) tendentially, but not significantly (P = 0.077), increased after 6 h and decreased after 24 h nitrogen deprivation, whereas Lia1 (yeast DOHH) was elevated significantly at both time points (Fig. 6k,l and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b), suggesting a superior role for DOHH in driving or maintaining the observed effects on eIF5AH. Compared with WT cells, ∆spe1 cells exhibited increased Lia1 protein levels in control but not −N conditions, and this phenotype could be corrected by SPD (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d). In double knockout ∆spe1∆lia1 cells, SPD failed to enhance eIF5AH levels in control and −N medium (Supplementary Fig. 5e,f), indicating that Lia1 is indeed responsible for the hypusination response.

Similarly, increased mRNA transcript levels of dohh-1 (C. elegans DOHH) and dhps-1 (DHS), but not iff-1 (EIF5A) were found in worms after 24 h fasting (Fig. 6m). Only DOHH levels stayed elevated after prolonged 48 h fasting (Supplementary Fig. 5g). In U2OS cells, 6 h starvation increased the abundance of mRNAs transcribed from all three genes (Fig. 6n).

Next, we compared the proteomic landscape during nitrogen deprivation in yeast cells treated with GC7, a specific pharmacological inhibitor of DHS/DYS1, and/or lacking SPE1. As previously observed, proteins involved in autophagy, TOR signalling, translation and amino acid metabolism were dysregulated when polyamine synthesis or hypusination were suppressed (Supplementary Fig. 5h–k), implying a multipronged effect of intracellular polyamine metabolism on these processes. Targeting hypusination directly with GC7 phenocopied many of the proteomic perturbations observed in the ∆spe1 strain, supporting a role of eIF5AH as a major downstream mediator of polyamine effects on energy and amino acid metabolism, as well as on TOR signalling and autophagy (Supplementary Fig. 5h–k). Additionally, ribosomal processes, which are known to require polyamines55,56, were strongly decreased when SPE1 was lacking and/or eIF5AH was inhibited by GC7 (Supplementary Fig. 5h,j). Accordingly, deleting the starvation-responsive LIA1 gene significantly decreased the long-term survival benefits conferred by nitrogen deprivation (Fig. 6o). Similarly, a temperature-sensitive mutation of eIF5A (hyp2-1) entirely abolished the beneficial effect of nitrogen deprivation on chronological lifespan at the restrictive temperature (28 °C), when eIF5AH was blocked (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b), but only partially at the permissive temperature (20 °C) (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Moreover, GC7 reduced eIF5AH (Supplementary Fig. 6d,e) and chronological lifespan extension by nitrogen depletion (Supplementary Fig. 6f,g).

A heterozygous point mutation in eIF5A mutating lysine 51, which is the target of hypusination in flies (eIF5AK51R), has previously been shown to render SPD supplementation ineffective on the climbing ability of aging flies53. Likewise, IF12:12 conferred lifespan extension was lost in female and male eIF5AK51R/+ flies (Supplementary Fig. 6h,i), while not affecting food consumption during the first cycles of IF12:12 (Supplementary Fig. 6j). Similarly to SPD supplementation53, IF12:12 did not improve the climbing ability of aged female eIF5AK51R/+ flies (Supplementary Fig. 6k–m).

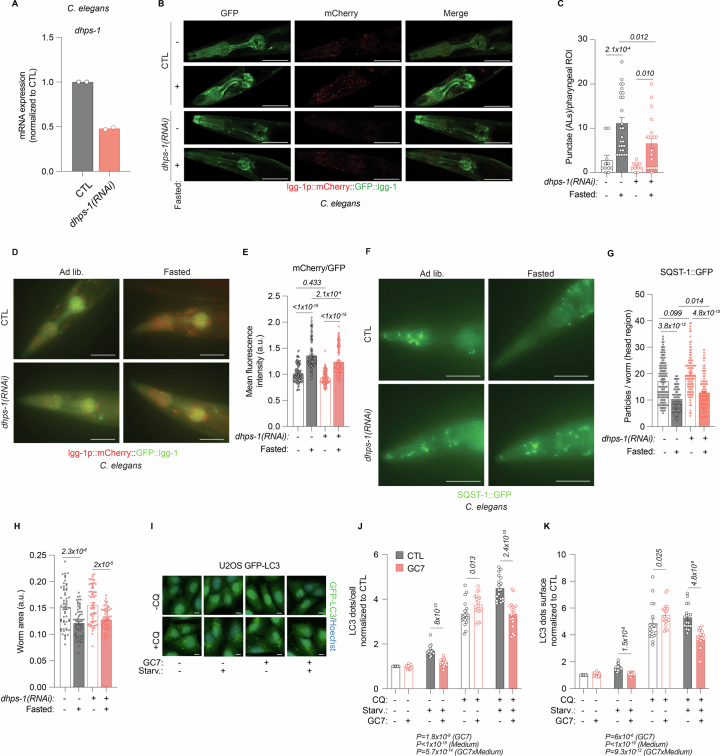

In C. elegans, the knockdown of dhps-1 (Extended Data Fig. 10a) attenuated the induction of autophagy (Extended Data Fig. 10b–g) and strongly reduced the beneficial effect of IF48:48 on lifespan (Fig. 6p) without affecting body size (Extended Data Fig. 10h). Similarly, GC7 reduced autophagic flux in starved U2OS cells (Extended Data Fig. 10i–k).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Hypusination is important for fasting-induced autophagy in worms and human cells.

(a) Feeding of dhps-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria reduces dhps-1 mRNA expression in C. elegans N2 worms. N = 2 biologically independent experiments. (b) Representative confocal images of the head region of young C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) fasted for two days and fed control or dhps-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria. Autolysosomes (ALs) appear as mCherry-positive puncta. Scale bar = 50 μm. (c) Quantification of ALs as depicted in [B]. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the odc-1(RNAi) groups in Fig. 3p. N = 11(CTL ad lib), 26(CTL fasted), 10(dhps-1(RNAi) ad lib), 21(dhps-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. (d) Representative fluorescence images of the head region of young C. elegans MAH215 (sqIs11 [lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) (LGG-1 is the C. elegans ortholog of LGG-1/Atg8) fasted for two days and fed control or dhps-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria. Autophagic activity is indicated by a shift to the red spectrum due to fluorescence quenching of the pH-sensitive-GFP by the acidic environment of the autolysosome. Scale bar = 50 μm. (e) Quantification of the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity of mCherry/GFP signals, as depicted in [D]. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the odc-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 6d. N = 121(CTL ad lib), 127(CTL fasted), 107(Dhps-1(RNAi) ad lib), 143(Dhps-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. (f) Representative fluorescence images of the head region of young C. elegans SQST-1::GFP fasted for two days and fed control or dhps-1(RNAi) expressing bacteria. Autophagic activity is indicated by a decrease in the number of GFP-positive particles. Scale bar = 50 μm. (g) Quantification of the SQST-1::GFP particles in the head region, as depicted in [F]. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the odc-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 6f. N = 133(CTL ad lib), 86(CTL fasted), 108(dhps-1(RNAi) ad lib), 100(dhps-1(RNAi) fasted) worms. (h) Knockdown of dhps-1 does not affect worm size under ad lib or IF conditions. Note that the experiment and statistics were performed together with the odc-1(RNAi) groups in Extended Data Fig. 7g. N = 56(CTL ad lib), 66(CTL IF), 62(dhps-1(RNAi) ad lib), 59(dhps-1(RNAi) IF) worms. (i) Representative images of U2OS GFP-LC3 cells starved in HBSS with or without 100 µM GC7 for 6 hours. CQ was added for 3 hours before fixation. (j-k) Quantifications of [I]. N = 18 biologically independent samples. Statistics: [C,E,G] Kruskal-Wallis-test with Dunn’s correction. [H,J,K] Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. Source numerical data are available in source data.

In summary, fasting induced SPD-dependent increases in eIF5AH in multiple species and this effect on eIF5AH was required for the pro-longevity effects of nitrogen starvation or IF in yeast, worms and flies.

Discussion

Acute fasting stimulates autophagy by inhibiting nutrient sensors (such as TORC1 and EP300) and activating signal transducers for nutrient scarcity (such as AMPK and SIRT1)4,57. Adult-onset IF with CR represents a translatable tool to improve age-associated diseases and systemic health of humans. Still, mechanistic details into the molecular and metabolic relay of nutritional information to lifespan regulation are missing but mandatory for successful clinical implementation. Here, we focused on closing a major gap in our understanding of the metabolic control of fasting-induced autophagy and longevity that apparently involves an increase in SPD-dependent hypusination of eIF5A.

Although fasting reduces the levels of amino acids, including ARG (together with its product ORN) and MET (and its product SAM), it also stimulates metabolic flux through the polyamine synthesis pathway, favouring an increase in SPD levels across different species, which requires ODC1. SPD is needed to hypusinate and activate eIF5A, a translation factor known to stimulate autophagy58. Indeed, we detected fasting-induced eIF5A hypusination across all analysed species, supporting the concept that SPD is universally implicated in the fasting response. Accordingly, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of SPD elevation or eIF5A hypusination curbed autophagy induction by fasting, and the longevity-promoting, cardioprotective and antiarthritic effects of IF across the phylogenetic spectrum.

Among the three ODC1-dependent polyamines, SPD seems to be crucial for mediating many fasting responses, mainly because it represents the sole co-factor for eIF5A hypusination. Nevertheless, supplementation with PUT or SPM also reversed ODC1 deficiencies, likely because they are interconvertible with SPD. However, PUT and SPM may partly function by other, yet-to-be-identified mechanisms.

We also found that autophagy induction by pharmacological mTOR inhibition partly depends on SPD synthesis in yeast and human cells, arguing in favour of a general role of SPD in autophagy stimulation. Notably, in yeast, nitrogen deprivation-induced inhibition of TORC1 was partially delayed in ∆spe1 cells, indicating a reciprocal relationship between polyamines and TOR signalling. Reflecting a complex crosstalk between polyamines and mTOR, SPD treatment was previously shown to activate mTORC1 in the white adipose tissue (WAT) of young mice, but to inhibit mTORC1 in the WAT of aged mice fed a high-fat diet, and not to affect liver mTOR signalling59, suggesting organ- or cell type-specific circuitries that remain to be explored.

Of note, in long-lived dilp2-3,5 mutant flies (which lack three of the seven insulin-like peptides), autophagy is induced as a result of enhanced levels of glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT), which also results in enhanced synthesis of the pro-autophagic metabolite SPD60. GNMT overexpression is sufficient to increase lifespan in flies, and lifespan extension via dietary restriction partially depends on GNMT in flies61. Similarly, ODC-1 is highly upregulated in the well-studied long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutant62, which encodes for the IGF1 receptor63,64, further suggesting that the polyamine and insulin signalling pathways are intertwined. Moreover, the liver-specific knockout of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) causes an increase in GNMT levels in mice60, pointing to a phylogenetically conserved pathway linking reduced trophic signalling to SPD elevation. However, it remains to be determined whether this pathway is active in response to fasting. Recently, the longevity effects of IF were linked to the circadian regulation of autophagy in flies65. As polyamines are subject to, and regulate, circadian rhythms66, this adds yet another possible intersection of lifespan regulation by SPD and hypusination in the context of fasting regimes.