Abstract

Background

This randomized placebo-controlled study examined the effect of ashwagandha root and leaf extract 60 mg (AE60) and 120 mg (AE120) (35 % withanolide glycosides, Shoden) in physically healthy subjects with higher stress and anxiety. It is hypothesized that a low dose extract with higher withanolide glycosides would decrease cortisol and increase testosterone thereby reducing stress and anxiety.

Methods

This parallel arm study recruited 60 subjects with an allocation ratio of 1:1:1 (AE60:AE120: placebo) for 60 days. Subjects who fulfilled the DSM –IV Criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) with a Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, HAMA score >20, and morning serum cortisol >25 mcg/dl were included in the study. The participants did not have depression symptoms and were screened using Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. The primary outcome measure was HAMA and the secondary measures were morning serum cortisol, testosterone, perceived stress scale (PSS), clinical global impressions scale (CGI), and patient's global impression of change scale (PGIC).

Results

After 60 days, significant differences were observed between the treatment groups and placebo. HAMA scores decreased by 59 % in both AE60 and AE120 groups compared to a negligible increase of 0.83 % in the placebo group (p < 0.0001). Morning serum cortisol levels decreased by 66 % in AE60 and 67 % in AE120, compared to a 2.22 % change in the placebo group (p < 0.0001). Testosterone levels increased by 22 % in AE60 and 33 % in AE120, compared to a 4 % increase in males in the placebo group (p < 0.0001). PSS scores decreased by 53 % in AE60 and 62 % in AE120, CGI-severity scores decreased by 72 % in AE60 and 68 % in AE120, and PGIC scores improved by 60 % in both AE60 and AE120 groups, all showing significant differences compared to the placebo group.

Conclusion

Ashwagandha extract with 35 % withanolide glycosides (Shoden) at 60 mg and 120 mg was significantly effective in reduced morning serum cortisol and increasing total testosterone. Therefore, it can be recommended for reducing high stress and anxiety.

Clinical trial registration

The study was prospectively registered in Clinical Trial Registry, India with registration number CTRI/2022/04/042133 [Registered on: April 25, 2022].

Keywords: Generalized anxiety disorder, HAMA, Morning serum cortisol, Testosterone, Withanolide glycosides, Ashwagandha

1. Introduction

High stress and anxiety are now common conditions in the post-COVID19 world. An excessive, persistent, and unrealistic worry about daily matters, with high stress and anxiety often referred to as Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is difficult to control and can lead to various non-specific psychological and physical symptoms. High stress and anxiety is a useful measure of this condition. The anxiety is associated with three or more of the given symptoms – restlessness & being on edge, easily fatigued, concentration difficulties or mind going blank, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and irritability. However, it does not include panic attacks which are considered the hallmark of all anxiety disorders [1].

About 3.1 % of the U.S. population are prone to GAD in any given year, yet only 43.2 % receive treatment [2]. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India from 1990 to 2017 study found that 197·3 million (95 % UI 178·4–216·4) people had mental disorders in 2017, with 45·7 million (42·4–49·8) with depressive disorders and 44·9 million (41·2–48·9) with anxiety disorders [3].

The biochemical basis of GAD is complex and not yet fully understood. One of the key neurotransmitters implicated in it is gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that plays a critical role in regulating anxiety and stress. It works by reducing the activity of excitatory neurons in the brain and promoting a state of relaxation. Studies have shown that individuals with this condition have lower levels of GABA in certain areas of the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex, and amygdala. This suggests that GABA deficiency may contribute to the development of anxiety and other symptoms of this condition [4].

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps to regulate mood, appetite, and sleep. Research has shown that individuals with high and prolonged anxiety may have lower serotonin levels or decreased sensitivity to serotonin in certain areas of the brain [5]. This may contribute to the anxiety, worry, and negative thoughts characteristic of this condition.

Finally, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is involved in the body's stress response, has also been implicated in generalized anxiety disorder [6]. In individuals with this condition, the HPA axis may be overactive, leading to increased levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. Cortisol inhibits serotonin [7] and GABAergic signalling by reducing the expression of GABA receptors and transporters [4]. This disrupts GABA's ability to induce a calm, relaxed state. This can result in various physical and psychological symptoms, including anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbances. This can exacerbate anxious thoughts and worries. Lowering cortisol may help rebalance serotonin for better mood and less anxiety. Normalizing cortisol with interventions like ashwagandha may help restore appropriate GABAergic tone and decrease anxiety.

Ashwagandha, or Withania somnifera is an herb used traditionally in India for various ailments. Several studies have demonstrated its use as an adaptogen best known for reducing stress and promoting sleep quality [8,9]. The phytochemicals in ashwagandha consists of withanolides, alkaloids, saponins, and other minor constituents. Withanolides, are the main phytochemicals present in the plant with reported anxiolytic, anticancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties [[10], [11], [12]]. Withanolides consists of withanolide aglycones and withanolide glycosides [13].

Withanolide glycosides have been found to modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity [14]. Clinical Studies have shown that withanolide glycosides can reduce cortisol levels which is involved in stress response and can counteract some of the negative effects of cortisol [14,15]. Withanolides can increase the activity of certain neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and acetylcholine, which can help regulate the HPA axis and reduce stress. It thus seems that the withanolide glycosides in ashwagandha may be able to help address the non-depression stress and anxiety symptoms.

Various ashwagandha extracts flood the market, each with its own standardization. Studies examining the effects of commercially available ashwagandha supplements on cortisol concentrations have utilized dosages ranging from 250 mg to 600 mg daily. These investigations reveal the effect of ashwagandha in reducing morning serum cortisol concentrations, in individuals experiencing stress and anxiety [14]. Moreover, efficacy studies supporting the use of ashwagandha extract standardized with 35 % withanolide glycosides highlight its potency in improving vitality, reducing stress, and modulating immunity [[15], [16], [17], [18]].

Given these insights, the present study seeks to investigate the potential stress-reducing effects of low-dose ashwagandha extract containing 35 % withanolide glycosides. Administering doses of 60 mg and 120 mg to physically healthy, non-depressed individuals with elevated stress and anxiety levels, we aim to test the hypothesis that Shoden ashwagandha, renowned for its high concentration of withanolide glycosides, may retain therapeutic efficacy even at lower doses. This exploration becomes crucial in light of the considerable variability in dosage and standardization across available ashwagandha extracts. By focusing on a standardized extract with a known potency of 35 % withanolide glycosides, this study aims to elucidate the potential benefits of Shoden ashwagandha across a spectrum of dosages, providing valuable insights into its optimal utilization for stress reduction and cortisol modulation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled, parallel arm study was conducted at Nirmal Hospital, Jhansi, UP from May to August 2022 with a sample size of 60. The allocation ratio was 1:1:1 (AE60:AE120: placebo), and the study duration was 60 days. The study population were recruited from the outpatient department at the hospital. The study used a prospectively approved protocol from the institutional ethics committee of Nirmal Hospital (ECR/325/Inst/UP/2013/RR-19) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the declaration of Helsinki (2013) and ICH-GCP E6 R2 (2016). The study was prospectively registered in CTRI with registration number CTRI/2022/04/042133 [Registered on: April 25, 2022].

2.2. Study inclusion/Exclusion criteria

The study procedures were explained in detail to the subjects by the principal investigator, and queries were clarified to the subject's satisfaction. After giving sufficient time to think it over, voluntary signed informed consent was procured before commencing the screening for the study. Males or females of age 18–60 years were screened for GAD using the self-diagnosing questionnaire based on the DSM–IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—fourth edition), having a Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, HAM-A score of greater than 20 with item #1 & #2 ≥ 2, a serum cortisol greater than 25 mcg/dl and a CGI-S score greater than or equal to 4 was considered for the study. In order to exclude depression volunteers with MADRS (Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale) total score greater than 12 with apparent and reported sadness ≥2, Item 10 (suicidal thoughts) score >1 or suicide attempt were excluded from the study [19,20]. Night shift workers were not considered for this study. Serum total testosterone was not an inclusion criterion in the study as the primary outcome biomarker in the study was cortisol.

2.3. Intervention and dosing

The investigational products (IP) used in this study were ashwagandha extract (AE) 60 mg and 120 mg standardized to 35 % withanolide glycosides (Shoden) referred herein respectively as AE60 and AE120 (Arjuna Natural Pvt. Ltd, Kerala, India). The placebo (PL) was 120 mg microcrystalline cellulose (Arjuna Natural Pvt. Ltd, Kerala, India). The dosing was one capsule with or after breakfast with a glass of water, for 60 days.

2.4. Standardization

The dried roots and leaves of the plant Withania somnifera obtained from contracted farmers was identified by qualified botanist, and the voucher specimen was maintained at the herbarium with the herbarium ID: AE-HBRS-021. The powdered dried roots and leaves were extracted using water and alcohol in 30:70 ratio with raw material to solvent ratio of 1:10. Using a proprietary process, the extract was standardized to contain 35 % withanolide glycosides (WG) with a herb to extract ratio of 40:1. The total WG was quantified using a Reversed-Phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) method [21]. The HPLC instrument was equipped with a PDA detector and a C18 column. The solvent system used for the analysis consisted of a gradient of potassium dihydrogen phosphate buffer and acetonitrile, and the wavelength used was 227 nm.

2.5. Randomization, blinding and unblinding

The randomization sequence was generated using the balanced randomization program in the software WinPepi version 11.65 by an independent statistician. The allocation ratio was 1:1:1, with 20 subjects in each group. This was concealed using alphanumeric codes by the statistician and the allocation concealed randomization list was given to the pharmacist for dispensation serially.

The investigator, study staff, and subjects were blinded toward the identity of the investigational products (IP). Both the test and the placebo capsules were opaque and indistinguishable in terms of their color, size, and shape, and were packaged and sealed in bottles of similar size and labelling. The only way to differentiate between them was through their allocation concealment codes.

The unblinding procedures were implemented using a pre-prepared sealed opaque envelope with only the allocation code written on the front. In case of an emergency, the principal investigator was instructed to notify the pharmacist, who would open the envelope and reveal the insert, which has the identity of the IP.

2.6. Outcome assessments

The primary outcome was a mean change in the HAM-A total score from baseline to day 60. The HAMA has 14 items scored according to the severity of anxiety on a five-point ratio scale. A total score of 17 or less indicates mild anxiety severity, 18 to 24 indicates mild to moderate anxiety severity, and 25 to 30 indicates moderate to severe anxiety severity [22]. HAM-A scoring was assessed at baseline and every 15 days until the end of the study.

The secondary outcomes included morning serum cortisol (8.00–9.00 a.m.) taken at baseline and every 15 days until the end of the study, and serum total testosterone at baseline and every 30 days. Serum cortisol was measured using chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) analyzer MAGLUMI (Shenzhen New Industries Biomedical Engineering Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China). Serum testosterone was measured using the ELFA technique (Enzyme Linked Fluorescent Assay) with VIDAS, BioMerieux company, France.

The clinical global impression scores (CGI), perceived stress scale scores (PSS), and patient global impression of change (PGIC) were taken at the baseline, day 30, and day 60. The 10-item PSS used a scoring system ranging from 0 to 4 (0 – never, 1 - almost never, 2 – sometimes, 3 - fairly often and 4 - very often). Total PSS Scores ranged from 0 to 13 is considered low stress; 14–16 moderate stress, and 27–40 high perceived stress [23]. The CGI is a clinician-rated scale that measures illness severity (CGI-S). The CGI-S is rated on a 7-point scale, with the severity of illness scale using a range of responses from 1 (normal) to 7 (amongst the most severely ill patients) [24]. PGIC is a 7-point scale depicting a rating of overall improvement of the participant. Participants rate their change as “very much improved (marked as 1),” “much improved,” “minimally improved,” “no change,” “minimally worse,” “much worse,” or “very much worse (marked as 7) [25].

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data analysis included all the data sets in the Intent to Treat (ITT) population and was analysed by an independent statistician. The data was analysed using non-parametric longitudinal factorial design (nparLFD) using nparLD package in R 4.0 [26]. The nparLD is a robust statistical method that is not sensitive to the distribution of the data or the presence of outliers. This makes it a good choice for analysing longitudinal data of the three treatments. The longitudinal analysis controls for correlation between measures on the same subjects over time, and factorial analysis (here time and treatment are taken as factors) can test if the effect of the interventional group depends on time or irrespective of it. This gives more precise results than running several conventional within and between group analysis, leading to increased type I error. In nparLFD there is little chance of falsely concluding there is a difference between groups or timepoints.

In nparLFD, the Wald test is used to evaluate the significance of the effects of the intervention, time, and interaction between intervention and time factors. The between group effects are given by the main intervention effect (denoted as IP (interventional product) in Table 2). A significant Wald test here indicates that the interventional groups do not have the same effect. The within group effects are given by the main effect of time (denoted as Time in Table 2). A significant Wald test here indicates that the time profile is not flat (ie: scores change with time). A significance in the interaction effect of time and intervention (denoted as IP:Time) indicates that the treatment profiles are not parallel (ie: not similar over time).

Table 2.

Mean value and percentage change of study outcomes in three groups.

| Parameter | Time point | Placebo |

AE 60 |

AE120 |

% change |

p value |

P value |

p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | % change from Baseline | Mean ± SD | % change from Baseline | Mean ± SD | % change from Baseline | PL-AE60# | PL-AE120$ | Time& | IP* | Time * IP¥ | ||

| HAMA (total score) | Baseline | 24 ± 1.49 | NA | 24.25 ± 2.20 | NA | 23.5 ± 2.33 | NA | −1.04 | 2.08 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| D15 | 23.55 ± 1.79 | 1.88 | 20 ± 1.78 | 17.53 | 19.5 ± 2.33 | 17.02 | 15.07 | 17.2 | ||||

| D30 | 23.6 ± 1.50 | 1.67 | 16.4 ± 1.85 | 32.37 | 16.45 ± 1.88 | 30 | 30.51 | 30.3 | ||||

| D45 | 23.9 ± 1.45 | 0.42 | 15.3 ± 2.00 | 36.91 | 14.55 ± 2.86 | 38.09 | 35.98 | 39.12 | ||||

| D60 | 24.2 ± 1.64 | −0.83 | 9.95 ± 2.46 | 58.97 | 9.65 ± 2.11 | 58.94 | 58.88 | 60.12 | ||||

| PSS (total score) | Baseline | 23 ± 1.65 | NA | 24.2 ± 1.79 | NA | 23.75 ± 2.99 | NA | −5.22 | −3.26 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| D30 | 21.45 ± 2.87 | 6.74 | 17.5 ± 1.79 | 27.69 | 15.8 ± 2.19 | 33.47 | 18.41 | 26.34 | ||||

| D60 | 21.9 ± 2.55 | 4.78 | 11.3 ± 2.58 | 53.31 | 9.05 ± 3.46 | 61.89 | 48.4 | 58.68 | ||||

| PGIC (total score) | Baseline | 4.25 ± 0.44 | NA | 4.1 ± 0.31 | NA | 4.15 ± 0.37 | NA | 3.53 | 2.35 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| D30 | 4.05 ± 0.22 | 4.71 | 2.45 ± 0.51 | 40.24 | 2.7 ± 0.47 | 34.94 | 39.51 | 33.33 | ||||

| D60 | 3.75 ± 0.79 | 11.76 | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 59.76 | 1.65 ± 0.59 | 60.24 | 56 | 56 | ||||

| Cortisol -(μg/dl) |

Baseline | 26.11 ± 0.63 | NA | 26.21 ± 0.86 | NA | 26.3 ± 0.81 | NA | −0.38 | −0.73 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| D15 | 25.53 ± 0.86 | 2.22 | 20.94 ± 2.9 | 20.11 | 20.58 ± 2.91 | 21.75 | 17.98 | 19.39 | ||||

| D30 | 25.19 ± 1 | 3.52 | 14.34 ± 2.98 | 45.29 | 12.16 ± 3.37 | 53.76 | 43.07 | 51.73 | ||||

| D45 | 25.38 ± 0.78 | 2.8 | 10.24 ± 2.35 | 60.93 | 9.45 ± 4.56 | 64.07 | 59.65 | 62.77 | ||||

| D60 | 25.53 ± 0.61 | 2.22 | 8.97 ± 1.89 | 65.78 | 8.76 ± 4.04 | 66.69 | 64.86 | 65.69 | ||||

| Testosterone - Male (ng/ml) | Baseline | 3.08 ± 0.95 | NA | 3.5 ± 0.94 | NA | 3.35 ± 0.64 | NA | −13.64 | −8.77 | <0.0001 | 0.0165 | <0.0001 |

| D30 | 3.26 ± 1.28 | 5.84 | 3.79 ± 0.85 | 8.29 | 4 ± 0.79 | 19.4 | −16.26 | −22.7 | ||||

| D60 | 3.21 ± 1.11 | 4.22 | 4.26 ± 1.07 | 21.71 | 4.47 ± 0.95 | 33.43 | −32.71 | −39.25 | ||||

| Testosterone -Female (ng/ml) | Baseline | 0.33 ± 0.09 | NA | 0.42 ± 0.21 | NA | 0.39 ± 0.12 | NA | −27.27 | −18.18 | <0.0001 | 0.343 | 0.0887 |

| D30 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 6.06 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 4.76 | 0.44 ± 0.12 | 12.82 | −25.71 | −25.71 | ||||

| D60 | 0.36 ± 0.16 | 9.09 | 0.5 ± 0.15 | 19.05 | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 15.38 | −38.89 | −25 | ||||

| CGI-S (total score) | Baseline | 5.15 ± 0.59 | NA | 5 ± 0.86 | NA | 5 ± 0.65 | NA | 2.91 | 2.91 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| D30 | 4.9 ± 0.55 | 4.85 | 2.45 ± 0.51 | 51 | 2.7 ± 0.47 | 46 | 50 | 44.9 | ||||

| D60 | 4.05 ± 1.1 | 21.36 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 72 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 68 | 65.43 | 60.49 | ||||

#, $ percentage change of AE60 and AE120 from placebo. &, *, ¥, 95 % significance p values of within group time factor, between groups treatment factor, and interaction of time and treatment from the Wald type statistics calculated from the nonparametric longitudinal factorial design analysis.

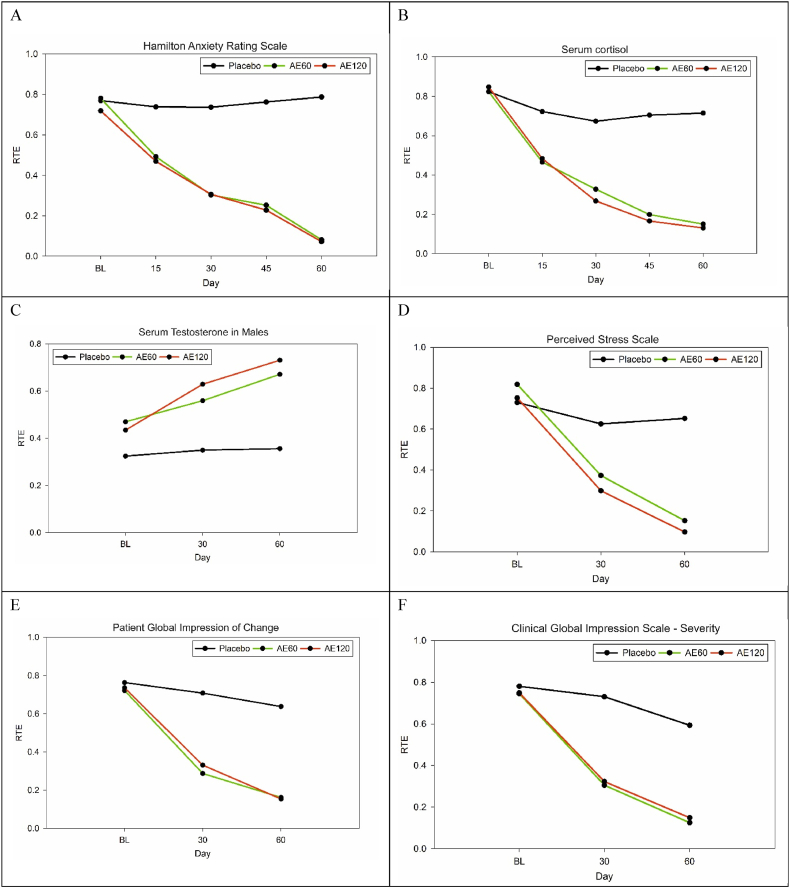

The relative treatment effect (RTE) [26] table that is part of the nparLD package contains rank means, RTE, bias, variance, and the upper and lower estimates of RTE. The RTE lies within the range of 0 and 1. In this study values below and above 0.5 indicates a decrease and increase in the outcome variable, respectively [[27], [28], [29]], and are interpreted along with the RTE plot. Bias is the difference between the expected value of the estimated relative treatment effect (RTE) and the true value of the RTE. Variance is the spread of the estimated RTE around its expected value. If the estimated RTE has a high variance, then it will be less precise and less reliable. The RTE plot's x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents the estimated RTE. Parallel lines indicate no difference in outcome between the test and control groups. If the lines diverge early and remain separated, it suggests that the intervention effect is immediate and sustained. If the lines converge over time, it suggests that the intervention effect may be delayed or temporary.

3. Results

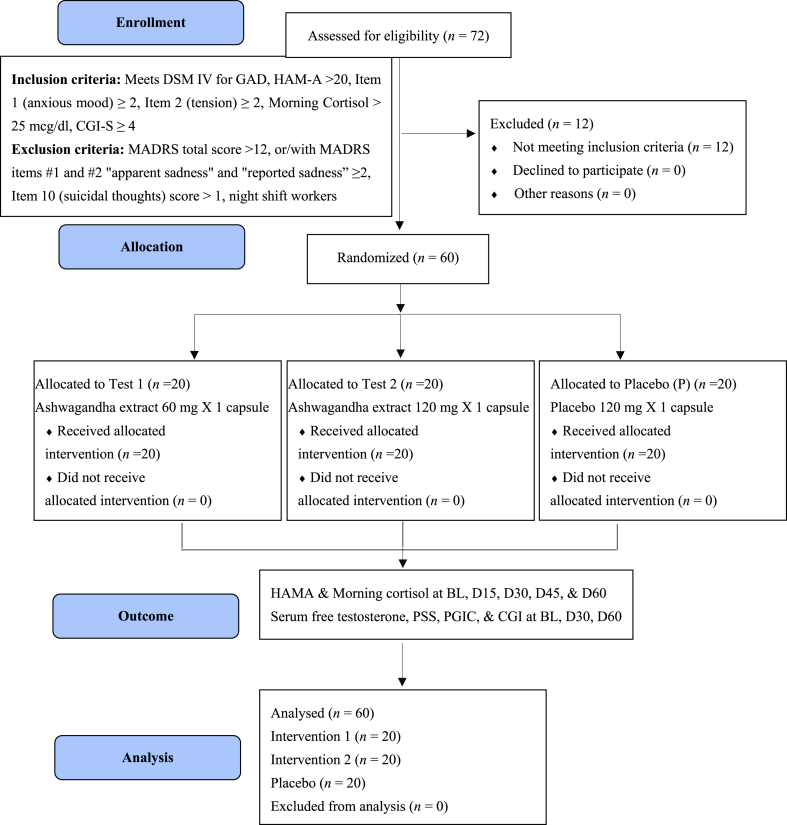

The study screened 72 participants and enrolled 60. There were 12 screen failures and no dropouts or withdrawals during the study. The study flow chart is given in Fig. 1. This 60-day study showed 100 % IP compliance, and no adverse events were reported. The demographic data are given in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Participants flowdiagram.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data of the three groups.

| Placebo | AE60 | AE120 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No:of participants | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Male | 14 | 14 | 13 |

| Female | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Age (mean)a | 35.5 ± 8.32 | 36.8 ± 10.29 | 36.35 ± 11.39 |

| Height (mean)a | 159.35 ± 9.65 | 160.05 ± 8.42 | 158.7 ± 4.99 |

| Weight (mean)a | 60.45 ± 10.17 | 60.75 ± 10.54 | 59.6 ± 8.06 |

No significant baseline differences among the groups.

p > 0.05 for age, height and weight.

There was a 59 % decrease in the HAMA total scores in AE60 and AE120 groups, whereas placebo groups had negligible change (−0.83 %) (Table 2). A non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis to test the intervention and time factors showed that intervention (IP) (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between intervention and time (p < 0.0001), variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable of anxiety score (Table 3). The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 A.

Table 3.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for HAMA from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | Rank Means | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Placebo | BLa | 20 | 231.4 | 0.7697 | 6.00E-04 | 0.0152 | 0.7367 | 0.799 |

| 2 | Placebo | D15 | 20 | 222.125 | 0.7388 | −9.00E-04 | 0.0242 | 0.6972 | 0.7758 |

| 3 | Placebo | D30 | 20 | 221.6 | 0.737 | −4.00E-04 | 0.0162 | 0.7033 | 0.7677 |

| 4 | Placebo | D45 | 20 | 229.425 | 0.7631 | 4.00E-04 | 0.0169 | 0.7283 | 0.794 |

| 5 | Placebo | D60 | 20 | 236.75 | 0.7875 | 4.00E-04 | 0.0256 | 0.7435 | 0.8245 |

| 6 | AE120 | BLa | 20 | 216.25 | 0.7192 | 4.00E-04 | 0.076 | 0.6435 | 0.7824 |

| 7 | AE120 | D15 | 20 | 141.35 | 0.4695 | −3.00E-04 | 0.0413 | 0.4186 | 0.5211 |

| 8 | AE120 | D30 | 20 | 92.375 | 0.3062 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0182 | 0.2734 | 0.3416 |

| 9 | AE120 | D45 | 20 | 68.875 | 0.2279 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0218 | 0.1932 | 0.2679 |

| 10 | AE120 | D60 | 20 | 22.05 | 0.0718 | −2.00E-04 | 0.0035 | 0.0594 | 0.0899 |

| 11 | AE60 | BLa | 20 | 234.75 | 0.7808 | 2.00E-04 | 0.0761 | 0.7013 | 0.841 |

| 12 | AE60 | D15 | 20 | 148.225 | 0.4924 | −3.00E-04 | 0.0266 | 0.4513 | 0.5336 |

| 13 | AE60 | D30 | 20 | 91.425 | 0.3031 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0183 | 0.2702 | 0.3385 |

| 14 | AE60 | D45 | 20 | 76.1 | 0.252 | 2.00E-04 | 0.0141 | 0.2234 | 0.2835 |

| 15 | AE60 | D60 | 20 | 24.8 | 0.081 | −2.00E-04 | 0.005 | 0.066 | 0.1023 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably reduce the HAMA scores whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

Fig. 2.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) Plot for the outcome variables (A) Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (B) Serum cortisol (C) Serum Testosterone in Males (D) Perceived Stress Scale (E) Patient Global Impression of Change (F) Clinical Global Impression Scale – Severity. The RTE was generated from the nonparametric longitudinal factorial analysis. The plot indicates a significant change and it can be seen that the treatment effect of the AE60 and AE120 is immediate and sustained.

Cortisol stress levels decreased significantly in the AE60 and AE120 groups by 66 % and 67 %, whereas the placebo had only a 2.22 % change (Table 2). (Fig. 2). IP (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable cortisol (Table 4). The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 B.

Table 4.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for the morning serum cortisol from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | Rank Means | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Placebo | BLa | 20 | 247.375 | 0.8229 | 9.00E-04 | 0.0207 | 0.7826 | 0.8557 |

| 2 | Placebo | D15 | 20 | 217.4 | 0.723 | −6.00E-04 | 0.0332 | 0.6742 | 0.7662 |

| 3 | Placebo | D30 | 20 | 202.55 | 0.6735 | −4.00E-04 | 0.0471 | 0.616 | 0.7255 |

| 4 | Placebo | D45 | 20 | 211.875 | 0.7046 | −3.00E-04 | 0.028 | 0.6603 | 0.7448 |

| 5 | Placebo | D60 | 20 | 215.025 | 0.7151 | 3.00E-04 | 0.0242 | 0.6739 | 0.7524 |

| 6 | AE120 | BL | 20 | 254.7 | 0.8473 | 2.00E-04 | 0.0423 | 0.785 | 0.8905 |

| 7 | AE120 | D15 | 20 | 145.525 | 0.4834 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0328 | 0.4379 | 0.5292 |

| 8 | AE120 | D30 | 20 | 80.9 | 0.268 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0195 | 0.2345 | 0.3051 |

| 9 | AE120 | D45 | 20 | 50.275 | 0.1659 | 4.00E-04 | 0.068 | 0.1125 | 0.2464 |

| 10 | AE120 | D60 | 20 | 39.65 | 0.1305 | −8.00E-04 | 0.0276 | 0.0958 | 0.1813 |

| 11 | AE60 | BL | 20 | 247.575 | 0.8236 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0444 | 0.7619 | 0.8692 |

| 12 | AE60 | D15 | 20 | 140.2 | 0.4657 | 2.00E-04 | 0.0143 | 0.4356 | 0.496 |

| 13 | AE60 | D30 | 20 | 98.775 | 0.3276 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0139 | 0.2986 | 0.3582 |

| 14 | AE60 | D45 | 20 | 60.1 | 0.1987 | 2.00E-04 | 0.019 | 0.1666 | 0.2365 |

| 15 | AE60 | D60 | 20 | 45.575 | 0.1503 | −4.00E-04 | 0.0158 | 0.122 | 0.1859 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably reduce the morning serum cortisol whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

Testosterone levels showed a 22 % and 33 % increase in the AE60 and AE120 groups, respectively, whereas in the placebo, there was a 4 % increase in males (Table 2). IP (p = 0.0165), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable Testosterone in males. The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 C. In females, there was no IP effect seen (p = 0.343), while there is significance in the time factor (p < 0.0001), but the interaction between IP and time was not significant (p = 0.0887) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for male testosterone from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | RankMeans | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE120 | BLa | 13 | 53.8846 | 0.434 | −0.0021 | 0.1548 | 0.321 | 0.5563 |

| AE120 | D30 | 13 | 77.8462 | 0.6288 | −0.0014 | 0.1352 | 0.5098 | 0.7308 |

| AE120 | D60 | 13 | 90.3462 | 0.7305 | 0.0035 | 0.154 | 0.5901 | 0.8279 |

| AE60 | BL | 14 | 58.25 | 0.4695 | −0.0048 | 0.1615 | 0.3518 | 0.5917 |

| AE60 | D30 | 14 | 69.25 | 0.5589 | 0 | 0.1146 | 0.454 | 0.6576 |

| AE60 | D60 | 14 | 83 | 0.6707 | 0.0048 | 0.1558 | 0.538 | 0.7751 |

| Placebo | BL | 14 | 40.3214 | 0.3238 | −0.0039 | 0.1314 | 0.2271 | 0.4455 |

| Placebo | D30 | 14 | 43.4643 | 0.3493 | 0.0031 | 0.1337 | 0.2497 | 0.4697 |

| Placebo | D60 | 14 | 44.2143 | 0.3554 | 0.0008 | 0.1304 | 0.2564 | 0.4737 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably increase the total testosterone whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

In the perceived stress scale, the AE60 group had a 53 % decrease, the AE120 group had a 62 % decrease, whereas placebo had a 5 % decrease (Table 2). IP (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable PSS (Table 6). The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 D.

Table 6.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for PSS from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | RankMeans | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | BLa | 20 | 131.95 | 0.7303 | 5.00E-04 | 0.0317 | 0.6821 | 0.7721 |

| Placebo | D30 | 20 | 113.075 | 0.6254 | −6.00E-04 | 0.0546 | 0.5642 | 0.6818 |

| Placebo | D60 | 20 | 117.9 | 0.6522 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0457 | 0.5958 | 0.7036 |

| AE120 | BL | 20 | 136 | 0.7528 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0697 | 0.6777 | 0.8112 |

| AE120 | D30 | 20 | 54.25 | 0.2986 | 4.00E-04 | 0.0114 | 0.2725 | 0.3266 |

| AE120 | D60 | 20 | 17.925 | 0.0968 | −4.00E-04 | 0.0113 | 0.0768 | 0.1338 |

| AE60 | BL | 20 | 147.925 | 0.819 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0523 | 0.7494 | 0.8666 |

| AE60 | D30 | 20 | 67.575 | 0.3726 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0167 | 0.3407 | 0.4061 |

| AE60 | D60 | 20 | 27.9 | 0.1522 | −1.00E-04 | 0.0138 | 0.1263 | 0.1862 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably reduce the PSS scores whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

In the patient global impression of change the AE60 & AE120 groups reported a 60 % change whereas placebo had a 12 % decrease (Table 2). IP (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable PGIC (Table 8). The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 E.

Table 8.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for PGIC from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | Rank Means | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | BLa | 20 | 137.875 | 0.7632 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0282 | 0.717 | 0.8021 |

| Placebo | D30 | 20 | 127.975 | 0.7082 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0104 | 0.6815 | 0.7331 |

| Placebo | D60 | 20 | 115.325 | 0.6379 | −1.00E-04 | 0.0761 | 0.5649 | 0.7035 |

| AE120 | BL | 20 | 132.925 | 0.7357 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0255 | 0.6926 | 0.7734 |

| AE120 | D30 | 20 | 60.05 | 0.3308 | −1.00E-04 | 0.0164 | 0.2996 | 0.3642 |

| AE120 | D60 | 20 | 28.175 | 0.1538 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0188 | 0.1241 | 0.1941 |

| AE60 | BL | 20 | 130.45 | 0.7219 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0164 | 0.688 | 0.7528 |

| AE60 | D30 | 20 | 52.175 | 0.2871 | 1.00E-04 | 0.0207 | 0.2526 | 0.3253 |

| AE60 | D60 | 20 | 29.55 | 0.1614 | −2.00E-04 | 0.0526 | 0.1157 | 0.2344 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably reduce the PGIC scores whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

The clinical global impression of change-severity had a 72 % and 68 % decrease for the AE60 and AE120 groups, respectively, with a 21 % change in placebo (Table 2). IP (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) variables all have a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable severity (Table 7). The RTE plot is given in Fig. 2 F.

Table 7.

Relative treatment effects (RTE) table for CGI-S from the non-parametric longitudinal factorial analysis.

| Group | Time | Count | Rank Means | RTE | Bias | Variance | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | BLa | 20 | 141.05 | 0.7808 | 5.00E-04 | 0.0185 | 0.7436 | 0.8125 |

| Placebo | D30 | 20 | 132 | 0.7306 | −1.00E-04 | 0.0236 | 0.6893 | 0.767 |

| Placebo | D60 | 20 | 107.25 | 0.5931 | −3.00E-04 | 0.0579 | 0.5307 | 0.6518 |

| AE120 | BL | 20 | 135.4 | 0.7494 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0508 | 0.6865 | 0.8005 |

| AE120 | D30 | 20 | 58.55 | 0.3225 | −1.00E-04 | 0.0144 | 0.2932 | 0.3538 |

| AE120 | D60 | 20 | 27.275 | 0.1488 | 1.00E-04 | 0.017 | 0.1206 | 0.1872 |

| AE60 | BL | 20 | 134.575 | 0.7449 | 0.00E+00 | 0.0736 | 0.6681 | 0.8052 |

| AE60 | D30 | 20 | 55.4 | 0.305 | 3.00E-04 | 0.0139 | 0.2763 | 0.3359 |

| AE60 | D60 | 20 | 23 | 0.125 | −3.00E-04 | 0.0091 | 0.1044 | 0.1534 |

BL: Baseline; RTE tending below 0.5 means that AE60 and AE120 were able to considerably reduce the CGI-S scores whereas placebo can be seen with minimal change to the RTE. The systematic deviation of the estimated treatment effect from the true treatment effect is given as the bias. How much the estimated treatment effects vary across different samples or iterations of the analysis is given by the variance.

4. Discussion

Ashwagandha, in traditional medicine systems for centuries, has garnered renewed interest in contemporary research for its potential health benefits [30]. Historically, emphasis was placed on utilizing the roots of ashwagandha for therapeutic purposes. However, modern extraction methods have unveiled the potential benefits residing in other parts of the plant, particularly the leaves [31,32]. Studies have revealed significant concentrations of withanolides, the bioactive compounds in ashwagandha, in both leaves and roots, expanding our understanding of the plant's diverse chemical composition [31,33]. Notably, the leaf exhibits similar withanolide composition to the root but in higher concentrations [31,34], along with a richer profile of primary and secondary metabolites [35]. The study by Kim et al. (2023) reported the enhanced bioavailability of ashwagandha root and leaf extract with 35 % withanolide glycosides compared to a regular ashwagandha extract demonstrating superior efficacy and emphasizing the significance of withanolide glycosides standardization in ashwagandha extracts. This study aims to delve into the therapeutic potential of root and leaf of Ashwagandha extract with total withanolides NLT 40 % comprising NLT 35 % withanolide glycosides, contributing to the expanding knowledge base on ashwagandha's holistic effects.

The primary outcome of this randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study was to investigate the effect of Shoden 60 mg and 120 mg (35 % withanolide glycosides ) in subjects with generalized anxiety disorder with HAMA. Both AE60 and AE120 groups significantly reduced their total score of HAMA by 59 % (p < 0.0001). A nonparametric longitudinal factorial analysis (nparLFD) on the interaction of time and IP was highly significant (p < 0.0001) indicating that the decrease in anxiety scores was definitely due to the intervention. The relative treatment effects (RTE) show that the outcome variable (HAMA score) was significantly decreased compared to the placebo. The plot of RTE shows that the lines diverge early and remain separated, indicating that the IP effect was immediate and sustained. The lines of AE60 and AE120 converge over time, indicating no apparent intervention difference between the two, based on HAM-A scores.

Adrenal glands, in response to stress, produce cortisol, and prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol can have a significant effect on mental and physical health, contributing to the symptoms of GAD. Studies have shown that individuals with high stress and anxiety have higher cortisol levels than normal individuals, particularly in response to stressors, and have been associated with increased anxiety symptoms and decreased quality of life [36,37]. The HPA axis has an inbuilt cortisol negative feedback system, but chronically elevated levels can lead to a decrease in the sensitivity of the HPA axis, which can result in a blunted response to stressors. Cortisol has been shown to interact with neurotransmitters involved in regulating anxiety, such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). It decreases the availability of serotonin and increases the activity of the enzyme responsible for breaking down GABA. These interactions may further contribute to the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders. High cortisol levels have been shown to negatively affect the hippocampus, which is a region of the brain involved in memory and emotion regulation, and impairing its functioning. This may contribute to the cognitive deficits and emotional dysregulation observed in individuals with high stress and elevated cortisol levels.

In this study, there was a significant reduction in serum morning cortisol as a measure of stress in the AE60 and AE120 groups by 66 % and 67 %, whereas the placebo had only a 2.22 % change. The significant interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) indicates that the change observed in all five timepoints was due to the effect of AE60 and AE120. Research suggests that withanolide glycosides may have a modulating effect on cortisol levels.

Ashwagandha has been shown to enhance GABAergic activity and modulate neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, which may help to alleviate anxiety symptoms. High stress levels and negative thoughts correlate negatively with Serotonin Receptor 5HT1a, and perception of stress is a predictive model of the expression of 5HT1a [38]. In the present study, the perceived stress scale score was significantly decreased by 53 % in the AE60 group and 62 % in the AE120 group. The placebo response showed only about a 5 % decrease. The IP (p < 0.0001), time (p < 0.0001), and interaction between IP and time (p < 0.0001) all had a statistically significant effect on the outcome variable of perceived stress.

Elevated levels of cortisol can have an inhibitory action on testosterone production leading to decreased sex drive, muscle mass, and bone density, in turn affecting the quality of life [39]. Even though testosterone level was not an inclusion criterion in this study, the baseline mean values (3.08–3.21 ng/mL) were at the lower end of normal range (3–10 ng/mL). In this study, serum total testosterone had a 22 % and 33 % increase in AE60 and AE120, respectively, whereas in the placebo, there was only a 4 % increase in males. There was no clinically significant increase in female testosterone. Another study conducted by Adrian et al., in 2019, involving aging, overweight males, with a 16-week regimen of Shoden delivering 21 mg withanolide glycosides daily resulted in a notable 14.7 % increase in testosterone levels [40]. This increase in male testosterone levels might be related to the cortisol lowering effect of ashwagandha.

A 2021 study on the effect of the comedication of ashwagandha root extract with SSRIs on GAD found that after 6 weeks of intake of 1g per day of ashwagandha extract, HAMA scores decreased from 29.11 at baseline to 15.27, representing a 47.6 % reduction [41]. In comparison, our study examined the effects of a standardised extract of 35 % WG in 60 mg and 120 mg AE with naïve GAD subjects. It was found that after 60 days, subjects taking 60 mg/day of AE had HAMA scores decrease from 24.25 to 9.95, a 59.1 % decrease, while those on 120 mg/day had decreased from 23.5 to 9.65, representing 58.9 % reduction. Although the study by Fuladi et al. used a higher dose of whole root extract, our study demonstrated that lower doses can bring about even greater anxiety reductions of 59 % (for both AE60 and AE120) which can be attributed to the increase in the concentration of withanolide glycosides.

A 60-day study of the anxiolytic effect of 240 mg ashwagandha with 35 % WG reported a 41 % reduction in HAMA [15]. The inclusion criteria in the Lopresti study was a HAMA score of 6–17 and hence the mean baseline value was 10.27 which decreased to 6.07. In the present study the inclusion criteria were specifically for GAD with HAMA score of greater than 20 with a mean baseline of 24.25 and 23.5 for AE60 and AE120 respectively.

A study by Chandrashekar et al. examining the effect of a 300 mg twice a day of high-concentration full-spectrum ashwagandha root extract (5 % WG) for 60days on stress and anxiety found that there was a 44 % change in the PSS score [42]. It was noted that there was a 53 % change in AE60 and 62 % change in AE120 in the present study for the PSS stress score.

The CGI which is a clinician's view of the subjects overall functioning before and after the intervention is well correlated with HAMA. In the present study, the investigators were able to see 72 % and 68 % decrease in the severity of anxiety for AE60 and AE120 respectively while placebo had a 21 % change. The analysis of interaction between IP and time was highly significant (p < 0.0001). This implies that the benefit seen is actually due to the effect of the intervention rather than a normal reduction of symptoms with time.

Anxiety and depression are highly comorbid. NESDA study reported that of depressive people 67 % had a current and 75 % had a lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder. Without controlling for depression, it can be difficult to determine if changes in anxiety symptoms are due to the treatment or just reflecting changes in depressed mood. Depression can influence anxiety ratings and reports. Feeling depressed can exacerbate negative perceptions and worries, causing anxiety scores and reports to increase [43]. Conversely, reducing depression may make anxiety feel more tolerable, leading to lower anxiety reports even if actual anxiety symptoms do not change. Many of the studies on anxiety and stress did not control for and may have included depression along with anxiety which may influence the results. In this study we have excluded depressed subjects with a MADRS total score greater than 12 and with apparent and reported sadness ≥2, Item 10 (suicidal thoughts) score >1 or suicide attempt in the 6 months prior to screening. Additionally, we have excluded night shift workers who have a disrupted circadian rhythm due to their sleep schedules. This can alter the normal diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion, including morning cortisol levels. This disruption could obscure the effects of ashwagandha or produce misleading results. Many studies could produce misleading results when not accounting for this. Limitations of the present study are its small sample size, lack of a 1:1 gender ratio, and shorter duration. These limitations can be addressed in future research through placebo-controlled studies of longer duration, larger size, broader populations, and careful control of confounders that will help expand the evidence base and enhance the validity and applicability of findings.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, ashwagandha extract standardized to contain 35 % withanolide glycosides (Shoden) at doses of 60 mg (AE60) and 120 mg (AE120) significantly reduced anxiety and stress in physically healthy subjects with elevated stress and anxiety levels. The AE60 and AE120 groups demonstrated substantial decreases in anxiety by 59 % as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), and in stress levels by 53 % and 62 %, respectively, as indicated by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Additionally, morning serum cortisol levels significantly decreased by 66 % and 67 %, and male testosterone levels increased by 22 % and 33 % in the AE60 and AE120 groups, respectively, compared to the placebo group. Although there was a non-significant trend favouring the higher dosage of 120 mg over the 60 mg dose in reducing stress and anxiety, the overall results suggest that both doses are effective. Ashwagandha extract with 35 % withanolide glycosides can be recommended for individuals seeking to reduce high levels of stress and anxiety.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and got approved by Nirmal Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh (Protocol Code AN-11SHO0322H3-WES08 and date of approval April 19, 2022)

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Deo Nidhi Mishra: Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Manoj Kumar: Writing – original draft, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Arjuna Natural Pvt. Ltd., Kerala, India, for providing Ashwagandha (Shoden) and placebo capsules for this trial.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36885.

Contributor Information

Deo Nidhi Mishra, Email: mishradeonidhi@gmail.com.

Manoj Kumar, Email: drmanoj.nirmal@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Bandelow B., Boerner R., Kasper S., Linden M., Wittchen H.-U., Möller H.-J. The diagnosis and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:300. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ADAA Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) 2022. https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/generalized-anxiety-disorder-gad Adaa.Org/Understanding-Anxiety/Generalized-Anxiety-Disorder-Gad.

- 3.Sagar R., Dandona R., Gururaj G., Dhaliwal R.S., Singh A., Ferrari A., Dua T., Ganguli A., Varghese M., Chakma J.K. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:148–161. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lydiard R.B. The role of GABA in anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2003;64:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutt D.J. Neurobiological mechanisms in generalized anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2001;62:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds J.A., Sanchez E.R. The role of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) Axis in test-induced anxiety: assessments, physiological responses, and molecular details. Stresses. 2022;2:146–155. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowen P.J. Cortisol, serotonin and depression: all stressed out? Br. J. Psychiatr. 2002;180:99–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshpande A., Irani N., Balkrishnan R., Benny I.R. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract on sleep quality in healthy adults. Sleep Med. 2020;72:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy S.V., Fathima S.N., Mote R. Hydroalcoholic extract of ashwagandha improves sleep by modulating GABA/histamine receptors and EEG slow-wave pattern in in vitro - in vivo experimental models. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2022;27:108–120. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2022.27.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bashir A., Nabi M., Tabassum N., Afzal S., Ayoub M. An updated review on phytochemistry and molecular targets of Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha) Front. Pharmacol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1049334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White P.T., Subramanian C., Motiwala H.F., Cohen M.S. Natural withanolides in the treatment of chronic diseases. Anti-Inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. 2016:329–373. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budhiraja R.D., Krishan P., Sudhir S. Biological activity of withanolides. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 13.AOAC SMPR 2015 007, standard method performance requirements SM (SMPRs) for withanolide glycosides and aglycones of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) 2015. https://www.aoac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SMPR202015_007.pdf

- 14.Lopresti A.L., Smith S.J., Drummond P.D. Modulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis by plants and phytonutrients: a systematic review of human trials. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022;25:1704–1730. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2021.1892253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopresti A.L., Smith S.J., Malvi H., Kodgule R. An investigation into the stress-relieving and pharmacological actions of an ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Medicine. 2019;98 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tharakan A., Shukla H., Benny I.R., Tharakan M., George L., Koshy S. Immunomodulatory effect of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) extract—a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial with an open label extension on healthy participants. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:3644. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshpande A., Irani N., Balkrishnan R., Benny I.R. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract on sleep quality in healthy adults. Sleep Med. 2020;72:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopresti A.L., Drummond P.D., Smith S.J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study examining the hormonal and vitality effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) in aging, overweight males. Am. J. Men's Health. 2019;13 doi: 10.1177/1557988319835985. 1557988319835985–1557988319835985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery S.A., Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery S.A, Asberg M.A, Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Https://Www.Veale.Co.Uk/Wp-Content/Uploads/2010/10/MADRS.Pdf (1978).

- 21.Antony B., Benny M., Kuruvilla B.T., Sebastian A., Aravindakshan Pillai A.A., Joseph B., Edappattu Chandran S. Development and validation of an RP-HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of total withanolide glycosides and Withaferin A in Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) Curr Chromatogr. 2020;7:106–120. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maier W., Buller R., Philipp M., Heuser I. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 1988;14:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E.-H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012;6:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padhi A., Fineberg N. Clinical global impression scales. Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. 2010:303. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin R.H., Turk D.C., Wyrwich K.W., Beaton D., Cleeland C.S., Farrar J.T., Haythornthwaite J.A., Jensen M.P., Kerns R.D., Ader D.N. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J. Pain. 2008;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noguchi K., Gel Y.R., Brunner E., Konietschke F. nparLD: an R software package for the nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. 2012. http://www.jstatsoft.org/

- 27.Schneider A.M., Weghuber D., Hetzer B., Entenmann A., Müller T., Zimmermann G., Schütz S., Huber W.D., Pichler J. Vedolizumab use after failure of TNF-α antagonists in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0868-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nardone R., Höller Y., Langthaler P.B., Lochner P., Golaszewski S., Schwenker K., Brigo F., Trinka E. RTMS of the prefrontal cortex has analgesic effects on neuropathic pain in subjects with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:20–25. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillett J.L., Duff J., Eaton R., Finlay K. Psychological outcomes of MRSA isolation in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020;6 doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joshi V.K., Joshi A. Rational use of ashwagandha in ayurveda (traditional Indian medicine) for health and healing. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021;276 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaul S.C., Ishida Y., Tamura K., Wada T., Iitsuka T., Garg S., Kim M., Gao R., Nakai S., Okamoto Y., Terao K., Wadhwa R. Novel methods to generate active ingredients-enriched ashwagandha leaves and extracts. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166945. 0166945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nile S.H., Nile A., Gansukh E., Baskar V., Kai G. Subcritical water extraction of withanosides and withanolides from ashwagandha (Withania somnifera L) and their biological activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019;132 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.110659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Zhang H., Kaul A., Li K., Priyandoko D., Kaul S.C., Wadhwa R. Effect of Ashwagandha Withanolides on muscle cell differentiation. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1454. doi: 10.3390/biom11101454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wadhwa R., Konar A., Kaul S.C. Nootropic potential of Ashwagandha leaves: beyond traditional root extracts. Neurochem. Int. 2016;95:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatterjee S., Srivastava S., Khalid A., Singh N., Sangwan R.S., Sidhu O.P., Roy R., Khetrapal C.L., Tuli R. Comprehensive metabolic fingerprinting of Withania somnifera leaf and root extracts. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantella R.C., Butters M.A., Amico J.A., Mazumdar S., Rollman B.L., Begley A.E., Reynolds C.F., Lenze E.J. Salivary cortisol is associated with diagnosis and severity of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenze E.J., Mantella R.C., Shi P., Goate A.M., Nowotny P., Butters M.A., Andreescu C., Thompson P.A., Rollman B.L. Elevated cortisol in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder is reduced by treatment: a placebo-controlled evaluation of escitalopram. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2011;19:482–490. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ec806c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandoval-Valerio A.K., Pérez-Vielma N.M., Miliar-García Á., Gómez-López M., García-García C., Aguilera-Sosa V.R. Negative thoughts and stress associated with the serotonin 5HT1a receptor in women with fibromyalgia. Acta Investig Psicol. 2020;10:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly D.M., Jones T.H. Testosterone: a metabolic hormone in health and disease. J. Endocrinol. 2013;217:R25–R45. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopresti A.L., Drummond P.D., Smith S.J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study examining the hormonal and vitality effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) in aging, overweight males. Am. J. Men's Health. 2019;13 doi: 10.1177/1557988319835985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuladi S., Emami S.A., Mohammadpour A.H., Karimani A., Manteghi A.A., Sahebkar A. Assessment of the efficacy of Withania somnifera root extract in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Current Reviews in Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology Formerly Current Clinical Pharmacology. 2021;16:191–196. doi: 10.2174/1574884715666200413120413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandrasekhar K., Kapoor J., Anishetty S. A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2012;34:255–262. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamers F., van Oppen P., Comijs H.C., Smit J.H., Spinhoven P., van Balkom A.J.L.M., Nolen W.A., Zitman F.G., Beekman A.T.F., Penninx B.W.J.H. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2011;72:3397. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.