Abstract

The current burden associated to multidrug resistance, and the emerging superbugs, result in a decreased and even loss of antibiotic efficacy, which poses significant challenges in the treatment of infectious diseases. This situation has created a high demand for the discovery of novel antibiotics that are both effective and safe. However, while antibiotics play a crucial role in preventing and treating diseases, they are also associated with adverse effects. The emergence of multidrug-resistant and the extensive appearance of drug-resistant microorganisms, has become one of the major hurdles in healthcare. Addressing this problem will require the development of at least 20 new antibiotics by 2060. However, the process of designing new antibiotics is time-consuming. To overcome the spread of drug-resistant microbes and infections, constant evaluation of innovative methods and new molecules is essential. Research is actively exploring alternative strategies, such as combination therapies, new drug delivery systems, and the repurposing of existing drugs. In addition, advancements in genomic and proteomic technologies are aiding in the identification of potential new drug targets and the discovery of new antibiotic compounds. In this review, we explore new sources of natural antibiotics from plants, algae other sources, and propose innovative bioinspired delivery systems for their use as an approach to promoting responsible antibiotic use and mitigate the spread of drug-resistant microbes and infections.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Natural antibiotics, Plant-based antibiotics, Algae-based antibiotics, Bioinspired delivery systems

Introduction

Over time, many bacteria develop ability to tolerate antibiotics, well before humans start mass-producing them as a means to prevent and treat infectious diseases [1, 2]. Currently, there is a great need to find new antibiotics that are effective and safe for society, due to the problems that have arisen related to the decrease and even loss of effectiveness of antibiotics due to an increase in bacterial resistance. While antibiotics are effective in preventing and treating infections in both humans and animals, they are also linked to negative side effects. The emergence of multi-drug resistant and extensively drug-resistant microorganisms poses a significant problem in the treatment of bacterial infections and related co-morbidities [3]. As a result of the concerning emergence and widespread dissemination of antibiotic resistance, coupled with the slow development of novel antibiotics, conventional treatments are progressively becoming less effective [4]. To address this problem, there is a need for new antibiotics and new treatments, but this discovery is a lengthy and time-consuming [5]. Therefore, innovative methods and new molecules are being proposed and evaluated constantly.

Multiple causes contribute to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including: (i) excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics [6], sometimes as the result of lack of new ones [7], (ii) inadequate infection control strategies [8], (iii) genetic variables, and (iv) environmental factors [9] and (v) natural resistance of the individual that occurs due to natural selective pressure, even with the correct use of the antibiotic.

The highest priority is to look for some alternative that might prevent the development of this drug resistance, and various natural antimicrobial molecules have been identified and explored for their application [10].

Unlike conventional antibiotics, natural bioactive compounds are not chemically modified secondary metabolites extracted from plants, fungi, microbes, or animals, that play an important role in the treatment of diverse pathologies. It is predicted that natural sources harbor a very large number of bioactive molecules that are yet to be discovered, particularly in plants.

One significant benefit of using phytochemicals for antimicrobial treatments is their ability to interact with several classes or subtypes of molecules, known as molecular promiscuity [11]. Traditional antibiotics usually have a specific bacterial molecular target, whereas phytochemicals usually show a multi-targeting capacity, i.e., the same compound showing a significant affinity to several protein targets [11]. The presence of promiscuity or multitarget affinity in bacteria can hamper the development of potential resistance mechanisms [12].

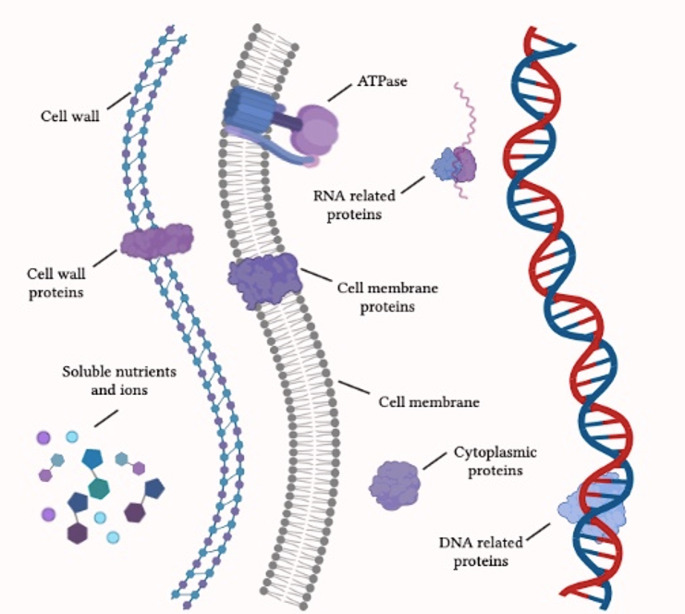

As shown in Fig. 1, phytochemicals have the potential to target various bacterial structures, such as the cell wall [13] and the components of the cell membrane [14]. They can also interact with proteins that are placed in different parts of the microorganism and have multiple activities [15]. This demonstrates their capability to interfere with nutrition metabolism and motility [16]. Besides their direct pharmacological effects, certain phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, have demonstrated the ability to enhance the susceptibility of antibiotic resistant bacteria. This is achieved by reversing their resistance mechanisms and by increasing their sensitivity to conventional drugs [17, 18].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the main bacterial molecular targets of phytochemicals with antibacterial activity

Since ancient times, plant extracts have been used by humans even when scientific evidence was practically nil and knowledge was limited to trial-and-error screenings [19]. Currently, advancement of modern technology can maximize the use of these phytochemicals and amplify their advantages for human health, as exemplified by nanotechnology [11, 20, 21].

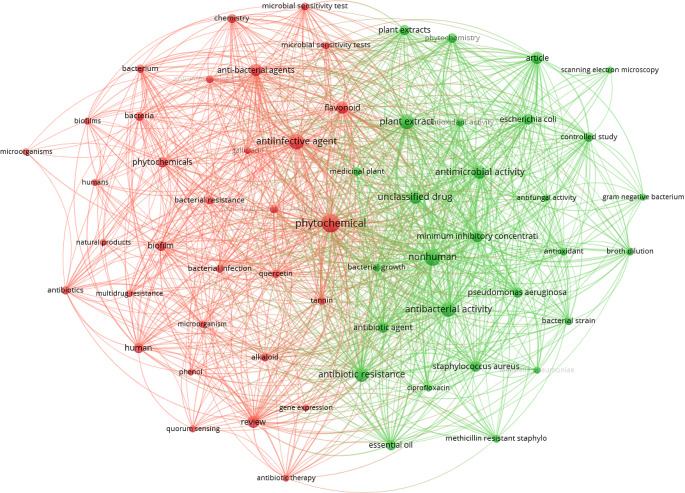

In this work, we propose to discuss the use of non-chemically modified natural antibiotics obtained from different sources that show evidence of potential use as alternative anti-microbial compounds to overcome antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and present potential nanotechnological alternatives for a synergistic treatment. To highlight the relevance of this scientific field, a search on Scopus database was conducted, using a combination of terms, i.e., “phytochemicals” and “antimicrobial”, which resulted in a total of 11,926 documents, almost half (5,233) published only since 2021. Refining our search to include the term “bacterial resistance”, a total of 47 papers were retrieved and their abstract and keywords analysed by VOSviewer software to generate the bibliometric map shown in Fig. 2 [22]. Two clusters were generated from this data analysis, the dominating red cluster linking terms such as alkaloid, antibiotic therapy, biofilms, bacterial resistance, microbial sensitive testing and multidrug resistance. The green cluster linked terms such as antibacterial activity, bacterial growth, phytochemicals and minimum inhibitory concentration. The recorded outputs highlight the importance of discussing the potential uses of phytochemicals obtained from e.g., plantae, algae and from other sources, and how they can be exploited to overcome the burdens associated to antibiotic resistance.

Fig. 2.

Bibliometric map obtained by VOSviewer software version 1.6.16 (https://www.vosviewer.com), using “phytochemicals” AND “antimicrobial” AND “bacterial resistance” as keywords, recorded from Scopus database limiting the search to documents published from 2021 onwards (recorded on the 3rd May 2024)

Antimicrobials from plant sources

One of the primary benefits of utilizing phytochemicals for antimicrobial purposes is their ability to interact with several factors or their molecular promiscuity [11]. This multi-target affinity makes it difficult to generate possible resistance mechanisms in bacteria [12].

Medicinal plants are rich in a range of phytochemical compounds, namely alkaloids, coumarins, essential oils, flavonoids, lectin, phenolic, polypeptides, polyacetylenes terpenoids and tannins [23, 24]. These bioactive chemicals have the potential to exhibit bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects on bacteria that are resistant to several drugs. Additionally, these compounds may serve as precursors for the development of antibiotics that can be used to treat such infections [25–27].

The prevalence of antimicrobial resistance is increasing globally, posing a significant challenge to the effective management of numerous infectious diseases [28]. The rise of multidrug-resistance among clinically important bacterial species, and their propensity to form biofilms, is causing a significant public health concern [28]. Treating infections caused by biofilm-forming microorganisms is proving to be a challenging task as eradicating biofilms with conventional antibiotics is becoming increasingly difficult [29]. Several reports have demonstrated that antibiotics frequently fail to eliminate biofilms [30]. Therefore, innovative strategies capable of overcoming the limitations of conventional antibiotics are in demand. Natural chemicals, particularly those derived from plants, have been demonstrating potential uses for antimicrobial treatments [28]. Plant secondary metabolites show antibiofilm properties due to their many modes of action, that are distinct from those of conventional antibiotics. These mechanisms include the suppression of quorum-sensing, motility, adhesion, and reactive oxygen species generation, among others. The combined use of several phytochemicals and antibiotics has demonstrated synergistic or additive effects in the control of biofilms [28].

Biofilms are made of complex microbial communities connected to biological or abiotic surfaces and included in the matrix generated by proteins and polysaccharides [31]. Biofilm creation contributes to the set-up of antibiotic resistance and the generation of persistent cells which are accountable for the uncontrolled persistence of microbial infections [32]. The resistance of biofilms can be attributed to the simultaneous presence of various mechanisms, including limited penetration or deactivation of antimicrobial substances within the biofilm matrix, slow bacterial growth, the existence of persister cells, programmed cell death, and the positive regulation of efflux pumps, among others [33–35]. This inherited characteristic becomes increasingly challenging to eradicate, and is accountable for a serious of problems related to environment, agriculture, industry, and medicine [36].

Different studies describe the antimicrobial activity of Aloe vera and its main components, focusing on its antibacterial activity. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) biofilms growth was reduced by Aloe vera aqueous extract [37]. Moreover, these bacteria, along with oral pathogens sampled from patients with periodontal and periapical abscess (e.g., Clostridium bacilli, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Streptococcus mutans) could also be inhibited by Aloe vera gel [38]. Aloe vera composed-chitosan films were produced to promote antimicrobial effects in wound dressings [39]. Aloe-emodin is a molecule that has been identified as having antibacterial properties against S. aureus. It works by preventing the formation of biofilms and the generation of proteins outside the cells [40]. Aloe vera extracts also show the ability to counteract the growth of drug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in burned patients with wounds infections [41]. Aloe vera gel was successfully applied to reduce the growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa, as well as other Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Helicobacter pylori) and fungi (e.g., Candida albicans) [42].

Phytochemicals can enhance the effectiveness of antibiotics by acting e.g., as adjuvants [43], to promote their antimicrobial activity. This synergistic effect may result in the reduction the dose of antibiotic needed for the treatment [44], and thus minimizing their adverse effects and ultimately the impact on the environmental [45]. In addition, phytochemicals have the potential to enhance the immune system and the individual’s overall health, thus facilitating defense against infection [46]. An illustration of this phenomenon is the efficacy of utilizing reduced dosages of active compounds from plants for the treatment of infectious disorders. This can be attributed to the presence of a range of active ingredients in plant extracts, which enhances the therapeutic impact in comparison to isolated compounds [47], increasing the plant defense due to their synergistic action. One example of this synergistic effect occurs with tomatoes. When the fruit is attacked by an insect, alkaloids, oxidative enzymes, phenolics and proteinase inhibitors and act synergistically to ingest the threat, with subsequent digestion and metabolism. Likewise, in the species of wild tobacco Nicotiana attenuata, inhibitors of nicotine expression and trypsin proteinase act synergistically towards a defensive response against Spodoptera exigua (Hub) pest infections [48].

An example of a plant that provides numerous phytochemicals that are beneficial to human health is Psidium guajava L., of the plant family Myrtaceae. This plant is a native American shrub that grows in tropical environments worldwide [49]. The many components of the guava tree, such as bark, fruits, leaves, roots and stem, have been utilized in numerous countries for the treatment of stomachache, diabetes, diarrhea, and various other health conditions [50, 51]. The chemical composition of Psidium guajava L. includes alkaloids, carbohydrates, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, sterols, tannins and terpenoids [51, 52]. The published literature reports phenolics as the major components of this plant, being capable of interacting with bacterial cell walls, resulting in their rupture and in the leakage of cellular components [53]. This leads to the suppression of a variety of microbial virulence factors (such as toxin production and biofilm formation), and to the inhibition of the synthesis of nucleic acids and the activity of enzymes [54].

Undoubtedly, the leaves of Psidium guajava L. are the most analyzed component. These are an abundant reservoir of essential nutrients, including minerals (such as calcium, iron, magnesium, potassium, sodium, sulfur), as well as vitamin B and C [55]. In addition to these compounds, Guava leaves are also rich in essential oils, and the major constituent includes 1,8-cineole and trans-caryophyllene [56]. These essential oils display strong cytotoxic and antimicrobial properties against Bacillus subtilis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus faecalis and S. aureus [57].

Guava leaves are recognized for their antibacterial properties because of the presence of various inorganic and organic antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds [58].

Our knowledge of the exact mechanism by which antibacterial activity occurs is currently inaccurate, mostly due to the widely diverse structures of phytochemicals, which give rise to numerous potential mechanisms of action. Furthermore, plant extracts consist of an intricate combination of chemicals that can affect their interaction [53]. The mechanism of action is therefore governed by the type of extract or essential oil and the type of microorganism involved in the infection [59].

Antimicrobials from algae sources

In pursuit of an alternative to conventional antibiotics, many studies are driving their focus on the use of marine sources [60]. Marine organisms are being described as an inexhaustible source of biologically active compounds, producing interesting bioactive molecules useful for treating diverse diseases [61].

Marine algae, a highly abundant oceanic resource, plays a crucial role in the marine ecosystem by serving as a primary food source for marine organisms and offering potentially renewable resources for humans [62]. Marine algae, encompassing both macroalgae and microalgae, inhabit diverse settings and are found in all Earth’s ecosystems [63]. Macroalgae are very suitable for exploiting novel alternative antimicrobials. The global diversity of micro and macroalgae is estimated to be roughly 164,000 species, with around 9,800 of them being marine algae [64].

Algae are photosynthetic organisms that exhibit a wide spectrum of adaptability to unfavorable environmental conditions. They produce vast quantities of secondary metabolites that are effective against a wide range of pathogenic bacteria. Algae from rivers, lakes, and the ocean have been found to possess antibacterial properties against harmful bacteria and fungi [65].

Algae present in the marine environment have a plentiful supply of natural substances that can be used for therapeutic purposes and several other applications. These algae can be found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic forms, and they inhabit a diverse range of environments, including shallow waters, coastal areas, and backwaters [60, 66]. Many scientific studies have demonstrated that substances extracted from these marine species exhibit antimicrobial properties against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, both in laboratory settings (in vitro) and in living beings (in vivo) [67, 68].

Marine algae can be categorized according to their pigment composition into three types, namely, green (Chlorophyta), brown (Phaeophyta), and red (Rhodophyta) [69, 70]. In recent years, interest on isolating and identifying bioactive chemicals from marine algae, particularly brown macroalgae, has been increasingly growing. A wide range of substances, including specific minerals and phytochemicals, have already been identified for their potential therapeutic properties in the management and prevention of many diseases [71, 72]. Brown seaweeds produce polysaccharides, such as alginates, fucoidans, and laminarins, which have been described for their numerous health advantages. Alginates are known to regulate hunger and have favorable effects on the gastrointestinal tract. They also exhibit antidiabetic and antihypertensive properties [73]. Fucoidans have been associated with the reduction of inflammation, tumor growth inhibition, regulation of the immune system, and with antioxidant and antiviral properties [73]. Laminarins are classified as dietary fibers that can enhance digestive health, and have a crucial role in preventing many disorders, such as colorectal cancer and gastrointestinal inflammation [74, 75].

Because of their numerous biological properties, such as their ability to regulate metabolic diseases, fight cancer, reduce inflammation, and act as an antioxidant, polyphenols are regarded as one of the most promising bioactive substances among other phytochemicals [76]. Marine algae can provide a range of polyphenols, including anthraquinones, benzoic acid, catechins, cinnamic acid, flavonoids, isoflavones, lignans, phenolic acids, phlorotannins and quercetin [67, 77].

Powerful poultry-associated foodborne pathogens responsible for salmonellosis are Salmonella species, in particular S. Typhimurium S. Enteritidis. New drug resistant Salmonella strains have also been described attributed to the excessive use of antibiotics [78]. Methanolic extract of Padina gymnospora (brown algae) displayed large inhibition zones (27 mm) against S. typhimurium [67], while red seaweeds aqueous extracts, Chondrus crispus and Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii, potentially inhibit the growth of S. Enteritidis at the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 15 µg/mL [78].

Extracts from Padina and Ulva sp. revealed antibacterial activity against Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes and S. aureus at concentrations below 500 µg/mL [79]. Srikong et al. (2017) [80] showed that crude extracts derived from the marine alga Ulva intestinalis exhibit strong antibacterial properties against B. cereus, S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and L. monocytogenes. The registered MIC and MBC values ranged from 256 to 512 µg/mL.

Marine algae exhibit antimicrobial activity against both bacterial cells and the production of biofilms. A study conducted in 2019, by the Waterford Institute of Technology in Ireland, examined the antibiofilm properties of extracts derived from two types of brown algae, Fucus serratus and Fucus vesiculosus, against MRSA. The results showed that these extracts were able to completely inhibit bacterial growth and reduce biofilm formation by over 80%. The MIC and MBC values for these extracts were found to be 3.125 and 25 mg/mL, respectively [81].

Antimicrobials from other sources

The use of natural products as a form of complementary treatment is currently receiving more attention. Propolis, a natural product, has gained attention for its several advantageous properties, making it a valuable option [82–84]. Propolis is a naturally occurring resinous substance that is gathered by several species of bees from diverse plant sources.

Bees collect resins and beeswax from many plant sources, including buds, exudates, flowers, gums, leaf resins, and mucilage found near their hive. They then enhance these substances with their β-glucosidase enzymatic saliva [85–88].

Bee products, particularly propolis, are extensively used in both traditional and alternative medicine. Propolis has been extensively mentioned in ancient medicine due to its manifold health advantages [89].

More than 500 types of compounds are found in propolis, including amino acids, aromatic acids, coumarins, essential oils, esters, flavonoids, minerals, polyphenols, sugars, terpenes, terpenoids, steroids, and vitamins have been identified in propolis [85, 90–92]. Its vitamins (A, B complexes, C and E), and important minerals, such as aluminum, calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, potassium, sodium and zinc [93, 94], play important roles in propolis biological activity [95]. Various factors can modify the composition of propolis. Changes in texture, fragrance, and color of honey occurs as a result of the specific plant parts collected by bees and the bee species involved [92]. Moreover, the antibacterial effects differ significantly across the bacterial strains and is dependent upon the specific propolis sample employed [96]. The medicinal benefits of propolis are mostly ascribed to its volatile components [97, 98], i.e., flavonoids and phenolic compounds. These chemicals are widely recognized for their antioxidant and antibacterial characteristics [99, 100]. Flavonoids present in propolis function by scavenging free radicals and by stimulating antioxidant enzymes. As a result, they protect the cell membrane from oxidative stress, including cellular aging, and against cardiovascular and brain disorders [101]. Many scientific studies describe the antibacterial activity of propolis and its derivatives against several Bacillus, Enterococcus and Streptococcus species, as well as against E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella typhi and Pseudomonas [88, 102, 103]. The anticancer and cytotoxicity properties of propolis mostly stem from chrysin, a plant flavone derived from Passiflora caerulea leaves. Several reports describe that this flavone possesses antibacterial effects due to its capacity to disrupt the structural integrity of the microbial cell wall and cell membrane [104, 105]. Furthermore, its ability to combat pathogenic yeasts, such as Candida sp., through its antifungal activities, presents a potential alternative for treating [106]. Propolis has been demonstrated to possess antiviral properties, as shown by Yildirim et al. (2016) [107]. Specifically, it has been shown to reduce the reproduction of the Herpes simplex virus in vitro, which is responsible for causing orofacial and genital infections. Red propolis hydroalcoholic extract was formulated in mucoadhesive polymeric membranes developed wound healing. These membranes, composed of collage, chitosan, polyethylene glycol and bearing 0.5% (m/V) of red propolis showed MIC values as low as 7.8 and 1.9 µg//mL for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, respectively [108].

Bioinspired delivery systems

New strategies proposed to overcome antibiotic resistance against bacterial infections include the development of nanotechnology-based delivery systems for selected phytochemicals with antimicrobial properties. Besides promoting targeted drug delivery and enhanced bioavailability [109–111], these nanomaterials also offer advantages related to mechanical, physicochemical, biopharmaceutical and modified-release properties [11, 20, 21].

Nanomaterials, that include nanoparticles (NPs) and nanofibers (NFs), can deal with limitations related to traditional strategies [112], offering the opportunity to be surface-tailored to show site-specific targeting approaches and reduce the risk of systemic drug exposure [113]. Besides the advantages related to their size and high surface-to-volume ratio, shape, composition and morphological properties, their mechanical, biological, and physicochemical properties can also be adjusted to meet the required needs [114]. The raw materials composing NPs should be biocompatible [115] and can be selected to be improve the biopharmaceutical properties (i.e., permeability and solubility) of antimicrobial drugs and increase their bioavailability for a certain administration route of selected phytochemicals [116]. Additionally, these characteristics can enhance the biopharmaceutical properties of the end products, particularly focusing on molecules with low bioavailability [117].

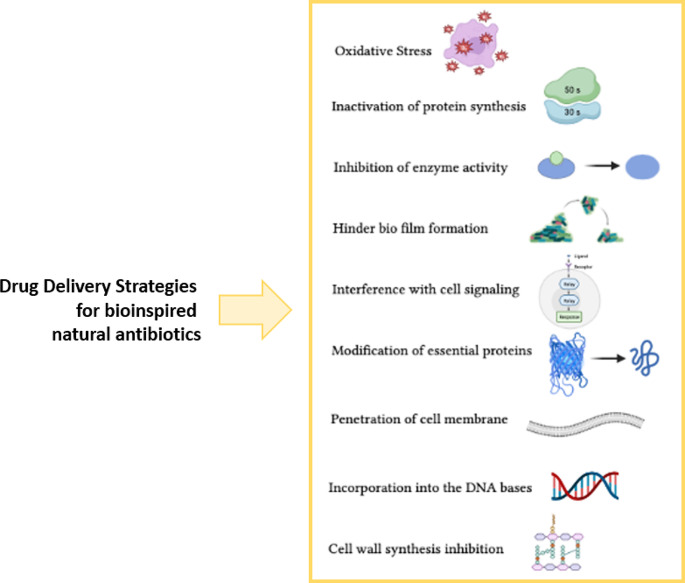

The potential to reduce the administered dose of drug [118], the enhanced half-life of loaded drug to be kept longer in the circulatory system for longer periods [119] and customization for precision medicine [120] are additional advantages attributed to NPs. Figure 3 depicts examples of drug delivery strategies that can be applied for bioinspired natural antibiotics. Table 1 summarizes recent applications of the use of drug delivery systems for these bioactives.

Fig. 3.

Examples of delivery strategies that can be applied for bioinspired natural antibiotics

Table 1.

Examples of polymeric nanoparticles loaded with phytochemicals against antibiotic resistant bacteria (reproduced after Díaz-Puertas et al. (2023) [11], under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

| Type of Polymer | Phytochemical | Synthesis | Mean Diameter (nm)* | Antibacterial Activity* | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Cardamom essential oil | Ionic gelation | 50–100 | Growth control for 2 days (E. coli, MRSA, ESBL) | [121] |

| Chitosan | Eucalyptus globulus leaf extract | Green synthesis | 7–10 | Zone of inhibition of 12–30 (multi drug- resistant Acinetobacter baumannii) | [122] |

| Chitosan / hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | Schinopsis brasiliensis leaf extract /Ceftriaxone | Polyelectrolytic complexation (coacervation) | 150–500 | MIC of 15 µg/mL (KPC, ESBL) | [123] |

| Polylactic acid / polyvinyl alcohol | Pistacia lentiscus var. chia essential oil | Solvent evaporation | 240–665 | MIC higher than 3.4 mg/mL (drug-resistant Bacillus subtilis sub. Spizizenii) | [124] |

Captions: ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; *Mean values or a range of values are indicated in studies employing various conditions or concentrations

Metal nanoparticles (MNPs) composed of elemental metals (such as Au, Ag, Cu, Fe, Pt, Pd, Ti, or Zn) or their corresponding compounds (such as CuO, Fe3O4, TiO2, ZnO). These particles have sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers. MNPs exhibit distinct physical and chemical characteristics that deviate from those of larger metal structures, owing to the impact of their reduced dimensions and elevated surface area-to-volume ratio [125]. These nanomaterials are being currently exploited in the fields of biomedical sciences and engineering because of their unique characteristics, including exceptional mechanical and thermal stability, large surface area, and remarkable optical and magnetic properties [126].

The nano-scale dimensions, morphology, surface charges, surface functionalization, and drug delivery capabilities of MNPs, which also possess antimicrobial activity [127], serve as a synergistic approach against multidrug-resistance bacterial infections [128, 129]. The main function of these MNPs is to reduce the capacity resistance of bacteria. This is achieved by disrupting membrane potential and bacterial cells integrity, inhibiting biofilms, promoting the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), boosting the immune responses of the host, and inhibiting RNA and protein synthesis through the induction intracellular processes [127, 129]. Moreover, the combination of conventional antibiotics with MNPs demonstrates a synergistic impact in decreasing drug-resistant bacterial infections [130, 131]. Table 2 summarizes some examples of green-synthesized MNPs using phytochemicals against antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Table 2.

Examples of green-synthesized metal nanoparticles using phytochemicals against antibiotic resistant bacteria (reproduced after Díaz-Puertas et al. (2023) [11], under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

| Metal Nanoparticles | Phytochemical | Mean diameter (nm) | MIC (µg/mL) * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs | Aloe vera extract | 38.9 | 4.9–9.8 (KPC) | [132] |

| Cinnamomum tamala LE | 10–12 | 12.5 (MDR E. coli), 10 (MDR K. pneumoniae, 12.5 (MDR S. aureus) | [133] | |

| Cotyledon orbiculate LE | 106–137 | 40 (MRSA) | [134] | |

| Flavopunctelia flaventior powder | 69 | 0.156 (MRSA), 0.078 (VRE), 0.019 (MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa), 0.078 (MDR E. coli) | [135] | |

| Mespilus germanica LE | 17.6 | 6.25–100 (MDR K. pneumoniae) | [136] | |

| Momordica charantia extract | 9.6–16.4 | 4 (CR A. baumannii), 4 (IR A. baumannii) | [137] | |

| Periploca hydaspidis extract | 68.6–114.2 | 10 (MDR K. pneumoniae), 10–20 (MDR S. aureus), 10 (MDR E. coli), 5 (MRSA) | [138] | |

| Stenocereus queretaroensis PE | 60–200 | 0.313 (MRSA) | [139] | |

| Syzygium cumini LE | 10–15 | 8 (MRSA), 20 (VRSA) | [140] | |

| Xanthoria parietina powder | 145 | 0.078 (MRSA), 0.156 (VRE), 0.039 (MDR P. aeruginosa), 0.156 (MDR E. coli) | [135] | |

| AuNPs | Anabaena spiroides extract | 80 | 25 (MDR Klebsiella oxytoca), 30 (MDR Steptococcus pyogenes), 20 (MRSA) | [141] |

| Punica granatum extract | 39.4 | 15.6 (MRSA) | [142] | |

| CuNPs | Syzygium cumini LE | 30–31 | 14 (MRSA), 16 (VRSA) | [140] |

| CuONPs | Camellia sinensis extract | 61 | 125 (CREC), 125 (CRKP), 30 (MRSA) | [143] |

| Prunus africana BE | 68 | 125 (CREC), 125 (CRKP), 30 (MRSA) | [143] | |

| FeNPs | Syzygium cumini LE | 40–46 | 11 (MRSA), 13 (VRSA) | [140] |

| PdNPs | Padina boryana extract | 8.7 | 125 (MDR S. aureus), 62.5 (MDR E. fergusonii), 62.5 (MDR A. pittii), 62.5 (MDR P. aeruginosa), 62.5 (MDR A. enteropelogenes), 125 (MDR P. mirabilis) | [144] |

| TeNPs | Aloe vera extract | 20–60 | 11.61 (MRSA), 3.53 (MDR E. coli) | [145] |

| ZnONPs | Acacia nilotica extract | 94 | 0.45 (KPC) | [146] |

Captions: BE, bark extract; CR, colistin-resistant; CREC, carbapenem-resistant E. coli; CRKP, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae; FE, flower extract; IR, imipenem-resistant; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; LE, leaf extract; MDR, multi-drug-resistant; MREC, methicillin-resistant E. coli; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; NPs, nanoparticles; PE, peel extract; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci; VRSA, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus. * Mean values or a range of values are indicated in studies employing various conditions or concentrations

Conclusions

The use of nanotechnology combined with phytochemical compounds from natural sources i.e., non-chemically modified antimicrobials obtained from different sources (e.g., plant, algae and others) offers several advantages to overcome the serious threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Nanomaterials can address limitations associated with traditional approaches and provide beneficial morphologies and surface features against bacterial infections. The characteristics of nanomaterials, such as size, shape, composition, and surface properties, can be adjusted to match the specific requirements of antimicrobial therapy. For example, polymeric matrices can result in small size and high surface-to-volume ratio, enhancing the permeability and solubility of loaded phytochemicals. This property is particularly advantageous for drug delivery, as it can improve the bioavailability of phytochemicals and enhance their antimicrobial effects with less drug systemic exposure. Polymeric nanoparticles offer several desirable properties for the encapsulation of antimicrobial drugs of natural origin. They enable controlled release of the loaded antimicrobial agents, allowing for sustained, prolonged or extended activity against bacteria. Nanoparticles also offer the possibility of targeted delivery, where the encapsulated drugs can be directed specifically to the site of infection, thereby minimizing systemic exposure and potential side effects minimizing the risk of toxicity. Properties, such as biocompatibility and tolerability, are instrumental for their safe use in biomedical applications. Nanoparticles can circulate in the bloodstream for longer periods, providing an extended duration of action. This feature is particularly beneficial for chronic or persistent bacterial infections. The possibility to customize their properties, i.e., tailoring nanoparticles to specifically meet the therapeutic needs, allows the development of precision medicine strategies. The same applies for metal nanoparticles, which became popular as they can be produced from natural sources using different types of phytochemicals. These nanoparticles naturally exhibit antibacterial properties that can further be exploited as novel types of antibiotics. Overall, the use of nanotechnology in combination with antibacterial phytochemicals holds promise to overcome the challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. By leveraging the unique properties of nanomaterials, it is possible to enhance the antibacterial capacity against resistant strains and develop more effective strategies for treating bacterial infections. The need to find new antibacterial agents that are effective against antibiotic resistant bacteria is in demand and nanotechnology is showing significant advancements for this purpose.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., Lisbon, Portugal. Faezeh Fathi is grateful to Laboratório Associado para a Química Verde - Tecnologias e Processos Limpos - UIDB/50006/2020 that supports her grant REQUIMTE 2020-20.

Funding

This work received financial support and help from (FCT/MCTES, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior) through the projects LA/P/0008/2020 DOI 10.54499/LA/P/0008/2020, UIDP/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDP/50006/2020 and UIDB/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50006/2020).

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Data availability

This work does not contain authors own data.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics issues

This work does not raise any specific ethics issues.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Faezeh Fathi, Email: ffathi@ff.up.pt.

Eliana B. Souto, Email: ebsouto@ff.up.pt

References

- 1.Bhullar K, Waglechner N, Pawlowski A, Koteva K, Banks ED, Johnston MD, Barton HA, Wright GD (2012) Antibiotic resistance is prevalent in an isolated cave microbiome. PLoS ONE 7:e34953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW, Schwarz C, Froese D, Zazula G, Calmels F, Debruyne R (2011) Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477:457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinemerem Nwobodo D, Ugwu MC, Oliseloke Anie C, Al-Ouqaili MTS, Chinedu Ikem J, Victor Chigozie U, Saki M (2022) Antibiotic resistance: the challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J Clin Lab Anal 36:e24655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huemer M, Mairpady Shambat S, Brugger SD, Zinkernagel AS (2020) Antibiotic resistance and persistence—implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep 21:e51034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miethke M, Pieroni M, Weber T, Brönstrup M, Hammann P, Halby L, Arimondo PB, Glaser P, Aigle B, Bode HB, Moreira R, Li Y, Luzhetskyy A, Medema MH, Pernodet J-L, Stadler M, Tormo JR, Genilloud O, Truman AW, Weissman KJ, Takano E, Sabatini S, Stegmann E, Brötz-Oesterhelt H, Wohlleben W, Seemann M, Empting M, Hirsch AKH, Loretz B, Lehr C-M, Titz A, Herrmann J, Jaeger T, Alt S, Hesterkamp T, Winterhalter M, Schiefer A, Pfarr K, Hoerauf A, Graz H, Graz M, Lindvall M, Ramurthy S, Karlén A, van Dongen M, Petkovic H, Keller A, Peyrane F, Donadio S, Fraisse L, L.J.V., Piddock IH, Gilbert HE, Moser R, Müller (2021) Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics, Nature Reviews Chemistry5: 726–749

- 6.Malik B, Bhattacharyya S (2019) Antibiotic drug-resistance as a complex system driven by socio-economic growth and antibiotic misuse. Sci Rep 9:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hays JP, Ruiz-Alvarez MJ, Roson-Calero N, Amin R, Murugaiyan J, van Dongen MB, G.A.I.A. Network (2022) Perspectives on the Ethics of Antibiotic Overuse and on the implementation of (New) antibiotics. Infect Dis Therapy 11:1315–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avershina E, Shapovalova V, Shipulin G (2021) Fighting antibiotic resistance in hospital-acquired infections: current state and emerging technologies in disease prevention, diagnostics and therapy, Frontiers in Microbiology 12:707330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Larsson DJ, Flach C-F (2022) Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:257–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisa M, Dar RA, Fomda BA, Nazir R (2023) Combating food spoilage and pathogenic microbes via bacteriocins: a natural and eco-friendly substitute to antibiotics. Food Control 149:109710 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Díaz-Puertas R, Álvarez-Martínez FJ, Falco A, Barrajón-Catalán E, Mallavia R (2023) Phytochemical-Based Nanomaterials against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: An Updated Review, Polymers 15:1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Álvarez-Martínez FJ, Barrajón-Catalán E, Encinar JA, Rodríguez-Díaz JC, Micol V (2020) Antimicrobial capacity of plant polyphenols against gram-positive bacteria: a comprehensive review. Curr Med Chem 27:2576–2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimech GS, Soares LAL, Ferreira MA, de Oliveira AGV, Carvalho MdC, Ximenes EA (2013) Phytochemical and antibacterial investigations of the extracts and fractions from the stem bark of Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne and effect on ultrastructure of Staphylococcus aureus induced by hydroalcoholic extract, The Scientific World Journal2013:862763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Meng X, Li D, Zhou D, Wang D, Liu Q, Fan S (2016) Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and related mechanism of the essential oil from the leaves of Juniperus rigida Sieb. Et zucc against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Ethnopharmacol 194:698–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari V (2019) Molecular insight into the therapeutic potential of phytoconstituents targeting protein conformation and their expression. Phytomedicine 52:225–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim G, Xu Y, Zhang J, Sui Z, Corke H (2022) Antibacterial activity and multi-targeting mechanism of dehydrocorydaline from corydalis turtschaninovii bess. Against listeria monocytogenes. Front Microbiol 12:3957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatano T, Kusuda M, Inada K, Ogawa T-o, Shiota S, Tsuchiya T, Yoshida T (2005) Effects of tannins and related polyphenols on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytochemistry 66:2047–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sousa V, Luís Â, Oleastro M, Domingues F, Ferreira S (2019) Polyphenols as resistance modulators in Arcobacter butzleri, Folia Microbiologica. 64:547–554 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Tapsell LC, Hemphill I, Cobiac L, Sullivan DR, Fenech M, Patch CS, Roodenrys S, Keogh JB, Clifton PM, Williams PG, Fazio VA, Inge KE (2006) Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future. Med J Aust 185:S1–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos TS, Silva TM, Cardoso JC, Albuquerque-Júnior RLCd, Zielinska A, Souto EB, Severino P, Mendonça MdC (2021) Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by Entomopathogenic Fungi: Antimicrobial Resistance, Nanopesticides, and Toxicity.Antibiotics 10:852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Santos T.S., de Souza Varize C, Sanchez-Lopez E, Jain S.A., Souto E.B., Severino P, Mendonça M.d.C. (2022) Entomopathogenic Fungi-mediated AgNPs: synthesis and Insecticidal Effect against Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Materials 15:7596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84:523–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva AM, Félix LM, Teixeira I, Martins-Gomes C, Schäfer J, Souto EB, Santos DJ, Bunzel M, Nunes FM (2021) Orange thyme: phytochemical profiling, in vitro bioactivities of extracts and potential health benefits. Food Chemistry: X 12:100171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sharifi-Rad J, Quispe C, Durazzo A, Lucarini M, Souto EB, Santini A, Imran M, Moussa AY, Mostafa NM, El-Shazly M, Sener B, Schoebitz M, Martorell M, Dey A, Calina D (2022) Cruz-Martins, Resveratrol’ biotechnological applications: enlightening its antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. J Herb Med 32:100550 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossiter SE, Fletcher MH, Wuest WM (2017) Natural products as platforms to overcome antibiotic resistance. Chem Rev 117:12415–12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gadisa E, Weldearegay G, Desta K, Tsegaye G, Hailu S, Jote K, Takele A (2019) Combined antibacterial effect of essential oils from three most commonly used Ethiopian traditional medicinal plants on multidrug resistant bacteria. BMC Complement Altern Med 19:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khameneh B, Iranshahy M, Soheili V (2019) Fazly Bazzaz, Review on plant antimicrobials: a mechanistic viewpoint. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8:1–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonçalves ASC, Leitão MM, Simões M, Borges A (2023) The action of phytochemicals in biofilm control. Nat Prod Rep 40:595–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arciola CR, Campoccia D, Montanaro L (2018) Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daikh A, Segueni N, Dogan NM, Arslan S, Mutlu D, Kivrak I, Akkal S, Rhouati S (2020) Comparative study of antibiofilm, cytotoxic activity and chemical composition of Algerian propolis. J Apic Res 59:160–169 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Somma A, Recupido F, Cirillo A, Romano A, Romanelli A, Caserta S, Guido S, Duilio A (2020) Antibiofilm properties of temporin-l on Pseudomonas fluorescens in static and in-flow conditions. Int J Mol Sci 21:8526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin T-J, Cheng Z (2019) Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv 37:177–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borges A, Saavedra MJ, Simões M (2015) Insights on antimicrobial resistance, biofilms and the use of phytochemicals as new antimicrobial agents. Curr Med Chem 22:2590–2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czaczyk K, Myszka K (2007) Biosynthesis of Extracellular Polymeric substances (EPS) and its role in Microbial Biofilm formation. Pol J Environ Stud 16:799–806 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena P, Joshi Y, Rawat K, Bisht R (2019) Biofilms: Architecture, Resistance, Quorum Sensing and Control mechanisms. Indian J Microbiol 59:3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satpathy S, Sen SK, Pattanaik S, Raut S (2016) Review on bacterial biofilm: an universal cause of contamination. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 7:56–66 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saddiq AA, Al-Ghamdi H (2018) Aloe vera extract: a novel antimicrobial and antibiofilm against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Pak J Pharm Sci 31:2123-2130 [PubMed]

- 38.Jain S, Rathod N, Nagi R, Sur J, Laheji A, Gupta N, Agrawal P, Prasad S (2016) Antibacterial effect of Aloe vera gel against oral pathogens: an in-vitro study. J Clin Diagn Research: JCDR 10:ZC41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genesi BP, de Melo Barbosa R, Severino P, Rodas ACD, Yoshida CMP, Mathor MB, Lopes PS, Viseras C, Souto EB (2023) Ferreira Da Silva, Aloe vera and copaiba oleoresin-loaded chitosan films for wound dressings: microbial permeation, cytotoxicity, and in vivo proof of concept. Int J Pharm 634:122648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang H, Cao F, Ming D, Zheng Y, Dong X, Zhong X, Mu D, Li B, Zhong L, Cao J (2017) Aloe-Emodin inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilms and extracellular protein production at the initial adhesion stage of biofilm development. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:6671–6681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goudarzi M, Fazeli M, Azad M, Seyedjavadi SS, Mousavi R (2015) Aloe vera gel: effective therapeutic agent against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates recovered from burn wound infections. Chemother Res Pract 2015:639806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Cataldi V, Di Bartolomeo S, Di Campli E, Nostro A, Cellini L (2015) Di Giulio, in vitro activity of Aloe vera inner gel against microorganisms grown in planktonic and sessile phases. Int J ImmunoPathol Pharmacol 28:595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright GD (2016) Antibiotic adjuvants: rescuing antibiotics from resistance. Trends Microbiol 24:862–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khameneh B, Eskin NM, Iranshahy M (2021) Fazly Bazzaz, Phytochemicals: a promising weapon in the arsenal against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics 10:1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar M, Jaiswal S, Sodhi KK, Shree P, Singh DK, Agrawal PK (2019) Shukla, Antibiotics bioremediation: perspectives on its ecotoxicity and resistance. Environ Int 124:448–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharya S, Paul SMN (2021) Efficacy of phytochemicals as immunomodulators in managing COVID-19: a comprehensive view. Virusdisease 32:435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borges A, Abreu AC, Dias C, Saavedra MJ, Borges F, Simões M (2016) New Perspectives on the Use of Phytochemicals as an Emergent Strategy to Control Bacterial Infections Including Biofilms, Molecules 21:877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.War AR, Paulraj MG, Ahmad T, Buhroo AA, Hussain B, Ignacimuthu S, Sharma HC (2012) Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal Behav 7:1306–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajan S, Hudedamani U, Rajasekharan P, Rao V (2019) In: Resources PE, Rajasekharan V, Ramanatha Rao (eds) Conservation and utilization of Horticultural Genetic. Springer. 10.1007/978-981-13-3669-0

- 50.Kumar M, Tomar M, Amarowicz R, Saurabh V, Nair MS, Maheshwari C, Sasi M, Prajapati U, Hasan M, Singh S, Changan S, Prajapat RK, Berwal MK, Satankar V (2021) Guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves:Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, and Health-Promoting Bioactivities. Foods 10:752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amaral VA, de Souza JF, Alves TFR, de Oliveira Junior JM, Severino P, Aranha N, Souto EB, Chaud MV (2024) Psidium guajava L. phenolic compound-reinforced lamellar scaffold for tracheal tissue engineering. Drug Delivery Translational Res 14:62–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Millones-Gómez PA, Maurtua-Torres D, Bacilio-Amaranto R, Calla-Poma RD, Requena-Mendizabal MF, Valderrama-Negron AC, Calderon-Miranda MA, Calla-Poma RA, Huauya_Leuyacc ME (2020) Antimicrobial activity and antiadherent effect of Peruvian Psidium guajava (guava) leaves on a cariogenic biofilm model. J Contemp Dent Pract 21:733–740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Efenberger-Szmechtyk M, Nowak A, Czyzowska A (2021) Plant extracts rich in polyphenols: antibacterial agents and natural preservatives for meat and meat products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 61:149–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takó M, Kerekes EB, Zambrano C, Kotogán A, Papp T, Krisch J, Vágvölgyi C (2020) Plant phenolics and phenolic-enriched extracts as antimicrobial agents against food-contaminating microorganisms. Antioxidants 9:165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adrian JAL, Arancon NQ, Mathews BW, Carpenter JR (2015) Mineral composition and soil-plant relationships for common guava (Psidium guajava L.) and yellow strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum var. Lucidum) tree parts and fruits. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 46:1960–1979 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee WC, Mahmud R, Pillai S, Perumal S, Ismail S (2012) Antioxidant activities of essential oil of Psidium guajava L. leaves. APCBEE Procedia 2:86–91 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soliman FM, Fathy MM, Salama MM, Saber FR (2016) Comparative study of the volatile oil content and antimicrobial activity of Psidium guajava L. and Psidium cattleianum Sabine leaves. Bull Fac Pharm Cairo Univ 54:219–225 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naseer S, Hussain S, Naeem N, Pervaiz M, Rahman M (2018) The phytochemistry and medicinal value of Psidium guajava (guava), clinical phytoscience. 4:1–8

- 59.Guimarães AC, Meireles LM, Lemos MF, Guimarães MCC, Endringer DC, Fronza M, Scherer R (2019) Antibacterial activity of terpenes and terpenoids present in essential oils. Molecules 24:2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song C, Yang J, Zhang M, Ding G, Jia C, Qin J, Guo L (2021) Marine natural products: the important resource of biological insecticide. Chem Biodivers 18:e2001020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han P, Li J, Zhong H, Xie J, Zhang P, Lu Q, Li J, Xu P, Chen P, Leng L (2021) Anti-oxidation properties and therapeutic potentials of spirulina. Algal Res 55:102240 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hannan MA, Sohag AAM, Dash R, Haque MN, Mohibbullah M, Oktaviani DF, Hossain MT, Choi HJ, Moon IS (2020) Phytosterols of marine algae: insights into the potential health benefits and molecular pharmacology. Phytomedicine 69:153201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wei N, Quarterman J, Jin Y-S (2013) Marine macroalgae: an untapped resource for producing fuels and chemicals. Trends Biotechnol 31:70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Beltagi HS, Mohamed AA, Mohamed HI, Ramadan KM, Barqawi AA, Mansour AT (2022) Phytochemical and potential properties of seaweeds and their recent applications: a review. Mar Drugs 20:342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Afzal S, Yadav AK, Poonia AK, Choure K, Yadav AN, Pandey A (2023) Antimicrobial therapeutics isolated from algal source: retrospect and prospect. Biol (Bratisl) 78:291–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhalodia NR, Shukla V (2011) Antibacterial and antifungal activities from leaf extracts of Cassia fistula l.: an ethnomedicinal plant. J Adv Pharm Tech Res 2:104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pina-Pérez MC, Rivas A, Martínez A, Rodrigo D (2017) Antimicrobial potential of macro and microalgae against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms in food. Food Chem 235:34–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lauritano C, Ianora A (2018) Grand challenges in marine biotechnology: overview of recent EU-funded projects, in: "Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology", P. H. Rampelotto, A. Trincone (eds.), Springer, Chapter 11, 10.1007/978-3-319-69075-9_11

- 69.El-Shenody RA, Ashour M, Ghobara MME (2019) Evaluating the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of three Egyptian seaweeds: Dictyota dichotoma, Turbinaria decurrens, and Laurencia obtusa. Braz J Food Technol 22:e2018203

- 70.de Borba Gurpilhares D, Cinelli LP, Simas NK, Pessoa A Jr, Sette LD (2019) Marine prebiotics: polysaccharides and oligosaccharides obtained by using microbial enzymes. Food Chem 280:175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Afonso NC, Catarino MD, Silva AM, Cardoso SM (2019) Brown macroalgae as valuable food ingredients. Antioxidants 8:365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Çelenk FG, Özkaya AB, Sukatar A (2016) Macroalgae of Izmir Gulf: Dictyotaceae exhibit high in vitro anti-cancer activity independent from their antioxidant capabilities. Cytotechnology 68:2667–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martić A, Čižmek L, Ul’yanovskii NV, Paradžik T, Perković L, Matijević G, Vujović T, Baković M, Babić S, Kosyakov DS, Trebše P, Čož-Rakovac R (2023) Intra-species variations of Bioactive compounds of two Dictyota species from the Adriatic Sea: antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Dermatological, Dietary, and Neuroprotective potential. Antioxidants [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Bogaert KA, Delva S, De Clerck O (2020) Concise review of the genus Dictyota JV Lamouroux. J Appl Phycol 32:1521–1543 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ganesan AR, Tiwari U, Rajauria G (2019) Seaweed nutraceuticals and their therapeutic role in disease prevention. Food Sci Hum Wellness 8:252–263 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hussain G, Huang J, Rasul A, Anwar H, Imran A, Maqbool J, Razzaq A, Aziz N, Makhdoom EUH, Konuk M (2019) Putative roles of plant-derived tannins in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatry disorders: an updated review. Molecules 24:2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gómez-Guzmán M, Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Gálvez J (2018) Potential role of seaweed polyphenols in cardiovascular-associated disorders. Mar Drugs 16:250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kulshreshtha G, Critchley A, Rathgeber B, Stratton G, Banskota AH, Hafting J, Prithiviraj B (2020) Antimicrobial effects of selected, cultivated red seaweeds and their components in combination with tetracycline, against poultry pathogen Salmonella enteritidis. J Mar Sci Eng 8:511 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dussault D, Vu KD, Vansach T, Horgen FD, Lacroix M (2016) Antimicrobial effects of marine algal extracts and cyanobacterial pure compounds against five foodborne pathogens. Food Chem 199:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Srikong W, Bovornreungroj N, Mittraparparthorn P, Bovornreungroj P (2017) Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of differential solvent extractions from the green seaweed Ulva intestinalis, ScienceAsia. 43:88–95

- 81.Higgins Hoare A, Tan SP, McLoughlin P, Mulhare P, Hughes H (2019) The screening and evaluation of Fucus serratus and Fucus vesiculosus extracts against current strains of MRSA isolated from a clinical hospital setting. Sci Rep 9:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zullkiflee N, Taha H, Usman A (2022) Propolis: its role and efficacy in Human Health and diseases.Molecules27: 6120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Batista CM, de Queiroz LA, Alves AVF, Reis ECA, Santos FA, Castro TN, Lima BS, Araujo ANS, Godoy CAP, Severino P, Cano A, Santini A, Capasso R, de Albuquerque Junior RLC, Cardoso JC, Souto EB (2022) Photoprotection and skin irritation effect of hydrogels containing hydroalcoholic extract of red propolis: a natural pathway against skin cancer. Heliyon 8:e08893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Carvalho FMA, Schneider JK, de Jesus CVF, de Andrade LN, Amaral RG, David JM, Krause LC, Severino P, Soares CMF, Bastos EC, Padilha FF, Gomes SVF, Capasso R, Santini A, Souto EB, de Albuquerque-Junior RLC (2020) Brazilian Red Propolis: Extracts Production, Physicochemical Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Profile for Antitumor Activity. Biomolecules 10:726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Wagh VD (2013) Propolis: a wonder bees product and its pharmacological potentials. Adv Pharmacol Sci2013:308249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Salatino A, Salatino MLF, Negri G (2021) How diverse is the chemistry and plant origin of Brazilian propolis? Apidologie, 1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Pascoal A, Feás X, Dias T, Dias LG, Estevinho LM (2014) The role of honey and propolis in the treatment of infected wounds, in: "Microbiology for surgical infections ", Chapter 13, Elsevier (, pp. 221–234

- 88.Anjum SI, Ullah A, Khan KA, Attaullah M, Khan H, Ali H, Bashir MA, Tahir M, Ansari MJ, Ghramh HA (2019) Composition and functional properties of propolis (bee glue): a review. Saudi J Biol Sci 26:1695–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.de Almeida-Junior S, Ferraz MVF, de Oliveira AR, Maniglia FP, Bastos JK, Furtado RA (2023) Advances in the phytochemical screening and biological potential of propolis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 37:886-899 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Fokt H, Pereira A, Ferreira A, Cunha A, Aguiar C (2010) How do bees prevent hive infections? The antimicrobial properties of propolis. Curr Res Technol Educ Top Appl Microbiol Microb Biotechnol 1:481–493 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Toreti VC, Sato HH, Pastore GM, Park YK (2013) Recent progress of propolis for its biological and chemical compositions and its botanical origin. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013:697390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Ahangari Z, Naseri M, Vatandoost F (2018) Propolis: Chemical composition and its applications in endodontics. Iran Endodontic J 13:285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pasupuleti VR, Sammugam L, Ramesh N, Gan SH (2017) Honey, propolis, and royal jelly: a comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits.Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017:1259510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Abdullah NA, Ja’afar F, Yasin HM, Taha H, Petalcorin MI, Mamit MH, Kusrini E, Usman A (2019) Physicochemical analyses, antioxidant, antibacterial, and toxicity of propolis particles produced by stingless bee Heterotrigona itama found in Brunei Darussalam.Heliyon 5:e02476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Abdullah NA, Zullkiflee N, Zaini SNZ, Taha H, Hashim F, Usman A (2020) Phytochemicals, mineral contents, antioxidants, and antimicrobial activities of propolis produced by Brunei stingless bees Geniotrigona thoracica, Heterotrigona itama, and Tetrigona binghami. Saudi J Biol Sci 27:2902–2911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Almuhayawi MS (2020) Propolis as a novel antibacterial agent. Saudi J Biol Sci 27:3079–3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bankova V, Popova M, Trusheva B (2014) Propolis volatile compounds: chemical diversity and biological activity: a review. Chem Cent J 8:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jihene A, Karoui IJ, Ameni A, Hammami M, Abderrabba M (2018) Volatile compounds analysis of Tunisian propolis and its antifungal activity. J Biosci Med 6:115–131 [Google Scholar]

- 99.da Silva JFM, de Souza MC, Matta SR, de Andrade MR, Vidal FVN (2006) Correlation analysis between phenolic levels of Brazilian propolis extracts and their antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Food Chem 99:431–435 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kurek-Górecka A, Rzepecka-Stojko A, Górecki M, Stojko J, Sosada M (2013) Świerczek-Zięba, structure and antioxidant activity of polyphenols derived from propolis. Molecules 19:78–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang J, Song Y, Chen Z, Leng SX (2018) Connection between systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation underlies neuroprotective mechanism of several phytochemicals in neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev2018:1972714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Przybyłek I, Karpiński TM (2019) Antibacterial properties of propolis. Molecules 24:2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rufatto LC, dos Santos DA, Marinho F, Henriques JAP, Ely MR, Moura S (2017) Red propolis: Chemical composition and pharmacological activity. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 7:591–598 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Celińska-Janowicz K, Zaręba I, Lazarek U, Teul J, Tomczyk M, Pałka J, Miltyk W (2018) Constituents of propolis: Chrysin, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, and ferulic acid induce PRODH/POX-dependent apoptosis in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell (CAL-27). Front Pharmacol 9:336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mani R, Natesan V (2018) Chrysin: sources, beneficial pharmacological activities, and molecular mechanism of action. Phytochemistry 145:187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mutlu Sariguzel F, Berk E, Koc AN, Sav H, Demir G (2016) Antifungal activity of propolis against yeasts isolated from blood culture: in vitro evaluation. J Clin Lab Anal 30:513–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yildirim A, Duran GG, Duran N, Jenedi K, Bolgul BS, Miraloglu M, Muz M (2016) Antiviral activity of hatay propolis against replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2.Med Sci Monit22:422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Loureiro KC, Barbosa TC, Nery M, Chaud MV, da Silva CF, Andrade LN, Correa CB, Jaguer A, Padilha FF, Cardoso JC, Souto E, Severino P (2020) Antibacterial activity of chitosan/collagen membranes containing red propolis extract. Pharmazie 75:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC (2016) Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev 116:2602–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xia W, Tao Z, Zhu B, Zhang W, Liu C, Chen S, Song M (2021) Targeted delivery of drugs and genes using polymer nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci 22:9118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Umerska A, Gaucher C, Oyarzun-Ampuero F, Fries-Raeth I, Colin F, Villamizar-Sarmiento MG, Maincent P, Sapin-Minet A (2018) Polymeric nanoparticles for increasing oral bioavailability of curcumin. Antioxidants 7:46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Barani M, Zeeshan M, Kalantar-Neyestanaki D, Farooq MA, Rahdar A, Jha NK, Sargazi S, Gupta PK, Thakur VK (2021) Nanomaterials in the management of gram-negative bacterial infections. Nanomaterials 11:2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hamdan N, Yamin A, Hamid SA, Khodir WKWA, Guarino V (2021) Functionalized antimicrobial nanofibers: design criteria and recent advances. J Funct Biomaterials 12:59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Spizzirri UG, Aiello F, Carullo G, Facente A, Restuccia D (2021) Nanotechnologies: an innovative tool to release natural extracts with antimicrobial properties. Pharmaceutics 13:230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Calzoni E, Cesaretti A, Polchi A, Di Michele A, Tancini B, Emiliani C (2019) Biocompatible polymer nanoparticles for drug delivery applications in cancer and neurodegenerative disorder therapies. J Funct Biomaterials 10:4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zielińska A, Carreiró F, Oliveira AM, Neves A, Pires B, Venkatesh DN, Durazzo A, Lucarini M, Eder P, Silva AM (2020) Polymeric nanoparticles: production, characterization, toxicology and ecotoxicology. Molecules 25:3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mira A, Rubio-Camacho M, Alarcón D, Rodríguez-Cañas E, Fernández-Carvajal A, Falco A, Mallavia R (2021) L-Menthol-Loadable Electrospun Fibers of PMVEMA Anhydride for Topical Administration. Pharmaceutics 13:1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Feczko T (2021) Polymeric nanotherapeutics acting at special regions of body. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 64:102597 [Google Scholar]

- 119.Skourtis D, Stavroulaki D, Athanasiou V, Fragouli PG, Iatrou H (2020) Nanostructured polymeric, liposomal and other materials to control the drug delivery for cardiovascular diseases. Pharmaceutics 12:1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 120.Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R (2021) Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 20:101–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jamil B, Abbasi R, Abbasi S, Imran M, Khan SU, Ihsan A, Javed S, Bokhari H, Imran M (2016) Encapsulation of cardamom essential oil in chitosan nano-composites: In-vitro efficacy on antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens and cytotoxicity studies. Front Microbiol 7:1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.El-Naggar NE-A, Shiha AM, Mahrous H, Mohammed AA (2022) Green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles, optimization, characterization and antibacterial efficacy against multi drug resistant biofilm-forming Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep 12:19869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.de Oliveira MS, Oshiro-Junior JA, Sato MR, Conceição MM, Medeiros ACD (2020) Polymeric nanoparticle associated with ceftriaxone and extract of schinopsis brasiliensis engler against Multiresistant enterobacteria. Pharmaceutics. 12:695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 124.Vrouvaki I, Koutra E, Kornaros M, Avgoustakis K, Lamari FN, Hatziantoniou S (2020) Polymeric nanoparticles of Pistacia lentiscus var. chia essential oil for cutaneous applications. Pharmaceutics 12:353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 125.Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I (2019) Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem 12:908–931 [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yaqoob AA, Ahmad H, Parveen T, Ahmad A, Oves M, Ismail IM, Qari HA, Umar K (2020) Mohamad Ibrahim, recent advances in metal decorated nanomaterials and their various biological applications: a review. Front Chem 8:341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Correa MG, Martínez FB, Vidal CP, Streitt C, Escrig J, de Dicastillo CL (2020) Antimicrobial metal-based nanoparticles: a review on their synthesis, types and antimicrobial action. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 11:1450–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Garcia-Torra V, Cano A, Espina M, Ettcheto M, Camins A, Barroso E, Vazquez-Carrera M, Garcia ML, Sanchez-Lopez E, Souto EB (2021) State of the Art on Toxicological Mechanisms of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Strategies to Reduce Toxicological Risks. Toxics 9:195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 129.Sanchez-Lopez E, Gomes D, Esteruelas G, Bonilla L, Lopez-Machado AL, Galindo R, Cano A, Espina M, Ettcheto M, Camins A, Silva AM, Durazzo A, Santini A, Garcia ML, Souto EB (2020) Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Nanomaterials 10:292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 130.Lee N-Y, Ko W-C, Hsueh P-R (2019) Nanoparticles in the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. Front Pharmacol 10:1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang L, Hu C, Shao L (2017) The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed 12:1227–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Chuy GP, Muraro PCL, Viana AR, Pavoski G, Espinosa DCR, Vizzotto BS, da Silva WL (2022) Green nanoarchitectonics of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial activity against resistant pathogens. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater 32:1213-1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 133.Dash SS, Samanta S, Dey S, Giri B, Dash SK (2020) Rapid green synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles using Cinnamomum tamala leaf extract and its potential antimicrobial application against clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacterial strains. Biol Trace Elem Res 198:681–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tyavambiza C, Elbagory AM, Madiehe AM, Meyer M, Meyer S (2021) The antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of silver nanoparticles synthesised from Cotyledon orbiculata aqueous extract. Nanomaterials 11:1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 135.Alqahtani MA, Al Othman MR, Mohammed AE (2020) Bio fabrication of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial and cytotoxic abilities using lichens. Sci Rep 10:16781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Foroohimanjili F, Mirzaie A, Hamdi SMM, Noorbazargan H, Hedayati Ch M, Dolatabadi A, Rezaie H, Bishak FM (2020) Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antiquorum sensing activities of phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles fabricated from Mespilus germanica extract against multidrug resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical strains. J Basic Microbiol 60:216–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Moorthy K, Chang K-C, Wu W-J, Hsu J-Y, Yu P-J, Chiang C-K (2021) Systematic evaluation of antioxidant efficiency and antibacterial mechanism of bitter gourd extract stabilized silver nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 11:2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.Ali S, Khan MR, Khan R (2021) Green synthesized AgNPs from Periploca Hydaspidis Falc. And its biological activities. Microsc Res Tech 84:2268–2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Padilla-Camberos E, Sanchez-Hernandez IM, Torres-Gonzalez OR, Ramirez-Rodriguez P, Diaz E, Wille H, Flores-Fernandez JM (2021) Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Stenocereus queretaroensis fruit peel extract: study of antimicrobial activity. Materials 14:4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Asghar MA, Zahir E, Asghar MA, Iqbal J, Rehman AA (2020) Facile, one-pot biosynthesis and characterization of iron, copper and silver nanoparticles using Syzygium cumini leaf extract: as an effective antimicrobial and aflatoxin B1 adsorption agents. PLoS ONE 15:e0234964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 141.Mandhata CP, Sahoo CR, Mahanta CS, Padhy RN (2021) Isolation, biosynthesis and antimicrobial activity of gold nanoparticles produced with extracts of Anabaena spiroides. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 44:1617–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hussein MAM, Grinholc M, Dena ASA, El-Sherbiny IM, Megahed M (2021) Boosting the antibacterial activity of chitosan–gold nanoparticles against antibiotic–resistant bacteria by Punicagranatum L. extract. Carbohydr Polym 256:117498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ssekatawa K, Byarugaba DK, Angwe MK, Wampande EM, Ejobi F, Nxumalo E, Maaza M, Sackey J, Kirabira JB (2022) Phyto-mediated copper oxide nanoparticles for antibacterial, antioxidant and photocatalytic performances. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:820218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sonbol H, Ameen F, AlYahya S, Almansob A, Alwakeel S (2021) Padina boryana mediated green synthesis of crystalline palladium nanoparticles as potential nanodrug against multidrug resistant bacteria and cancer cells. Sci Rep 11:5444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Medina-Cruz D, Vernet-Crua A, Mostafavi E, Gonzalez MU, Martinez L, Iii A-ADJ, Kusper M, Sotelo E, Gao M, Geoffrion LD, Shah V, Guisbiers G, Cholula-Díaz JL,, Guillermier C, Khanom F, Huttel Y, García-Martín JM, Webster TJ (2021) Aloe vera-mediated Te nanostructures: highly potent antibacterial agents and moderated anticancer effects. Nanomaterials 11:514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 146.Rasha E, Monerah A, Manal A, Rehab A, Mohammed D, Doaa E (2021) Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from Acacia nilotica (L.) extract to overcome carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Molecules 26: 1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This work does not contain authors own data.