Abstract

Background and Aims:

NAFLD is a major disease burden and a foremost cause of chronic liver disease. Presently, nearly 300 trials evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of > 20 drugs. Remarkably, the majority of drugs fail. To better comprehend drug failures, we investigated the reproducibility of fatty liver genomic data across 418 liver biopsies and evaluated the interpatient variability of 18 drug targets.

Approach and Results:

Apart from our own data, we retrieved NAFLD biopsy genomic data sets from public repositories and considered patient demographics. We divided the data into test and validation sets, assessed the reproducibility of differentially expressed genes and performed gene enrichment analysis. Patients were stratified by disease activity score, fibrosis grades and sex, and we investigated the regulation of 18 drug targets across 418 NAFLD biopsies of which 278 are NASH cases. We observed poor reproducibility of differentially expressed genes across 9 independent studies. On average, only 4% of differentially expressed genes are commonly regulated based on identical sex and 2% based on identical NAS disease score and fibrosis grade. Furthermore, we observed sex-specific gene regulations, and for females, we noticed induced expression of genes coding for inflammatory response, Ag presentation, and processing. Conversely, extracellular matrix receptor interactions are upregulated in males, and the data agree with clinical findings. Strikingly, and with the exception of stearoyl-CoA desaturase, most drug targets are not regulated in > 80% of patients.

Conclusions:

Lack of data reproducibility, high interpatient variability, and the absence of disease-dependent drug target regulations are likely causes of NASH drug failures in clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

NAFLD is defined by the presence of primarily macrovesicular LDs in > 5% of hepatocytes1 and is divided into NAFL and steatohepatitis/NASH. While NAFL is a benign and reversible condition, NASH is characterized by moderate to marked lobular inflammation, ballooned hepatocytes, and fibrosis of different grades.2 Recently, the NAFLD nomenclature consensus group suggested replacement of the term NAFLD by metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease.

An understanding of the molecular events in NAFLD improved significantly over the last decade,3–6 and overnutrition is a common cause. However, genetic polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and other genes play a role as well.4 Note the prevalence of NAFLD increased significantly from about 25% before 2005 to 37.8% in 2016, and the incidence is greater for men than women.7 Today, NASH with cirrhosis is a leading indication for liver transplantation.8

Although there are no approved medications to treat fatty liver disease, a range of drug candidates targeting insulin resistance and lipid metabolism, lipotoxicity and oxidative stress, inflammation and immune activation, lipoapoptosis and cell death, fibrogenesis, and collagen turnover entered clinical trials.9

Given the complex nature of NAFLD, genomic studies have been instrumental in an understanding of the cellular responses to excessive fat deposition in hepatocytes and alerted to a plethora of potential drug targets for therapeutic interventions.10

Based on our own research11,12 and the growing knowledge from independent studies, we questioned genomic data reproducibility for liver biopsies of patients with NAFLD. We collected genomic data for 111 unrelated patients, and the data were generated with the Affymetrix/Illumina platform. Moreover, we considered 307 individual patient data from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) studies. This enabled cross-validation of results by independent methods. In total, we assessed 418 liver biopsies for which genomic data are available.

Overall, we aimed at identifying common NAFLD-associated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different cohorts based on identical sex and disease scores. The nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score (NAS) measures disease activity by considering grades of steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning and ranges from 0 to 8. Additionally, we analyzed genomic data based on identical fibrosis grades and compared cases with identical NAS and fibrosis scores. Finally, we explored possible reasons for drug failures by considering transcriptional regulations of drug targets across different patient cohorts.

METHODS

Human liver biopsy genomic data

We queried public repositories (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) for MIAME-compliant data submissions and applied the following criteria: (1) human liver with NAFLD histology and disease activity scores; (2) medical records with sufficient information on patient characteristics; (3) no history of liver disease before the diagnosis of NAFLD; (4) a cohort size of ≥ 10 individuals; (5) patients > 18 years.

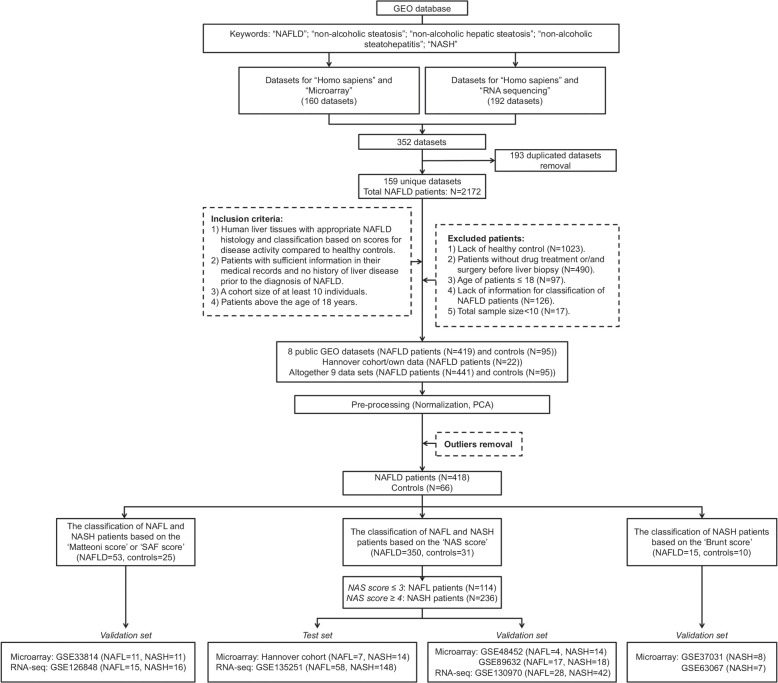

Based on eligibility criteria (Figure 1), we selected 419 cases. Additionally, we added 22 cases of our own research,11 and after the removal of outliers, 418 NAFLD and 66 controls entered the study (Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of data sets associated NAFL biopsies selection. Abbreviations: GEO, gene expression omnibus; PCA, principal component analysis; LDs, lipid droplets; SAF, steatosis, activity and fibrosis; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

We divided the data into independent test and validation sets and evaluated whole genome microarray data for 111 patients and RNA-seq data for 307 patients. For the microarray studies, we used our own data11 as a test set and GSE33814, GSE37031, GSE48452, GSE63067, and GSE89632 as validation sets. In regards to RNA-seq data, we used GSE135251 as the test set and GSE126848 and GSE130970 as the validation set (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263).

NAFLD disease scores

The histological classifications are based on the NAS metric and fibrosis grades according to Kleiner13, Brunt,14 steatosis, activity, fibrosis (SAF),15 and Matteoni et al16 (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). NAFL and NASH, respectively, are defined by NAS ≤ 3 and NAS ≥ 4, and there are 5 different fibrosis grades (F = F0-F4). The Hannover cohort/own data, GSE48452, GSE89632, GSE135251, and GSE130970 are classified by NAS and fibrosis grades. GSE37031 and GSE63067 are classified by Brunt grade 2 and 3 and GSE126848 and GSE33814 are scored by SAF and the Matteoni classification.

Data preprocessing and DEGs analysis

We uploaded the Hannover cohort, GSE37031, GSE63067 and GSE48452 files onto the GeneXplain platform version 7.1 (http://genexplain.com/genexplain-platform-1) and processed the data with the robust multi-array average method. We performed R computing for background-adjusted, normalized, and log-transformed perfectly matched probes and considered the signal intensity of annotated probe sets only. In the same way, we processed the Illumina data (GSE33814 and GSE89632) and used R for quantile normalization of log2-transformed data. Additionally, we uploaded GSE135251, GSE130970, and GSE126848 as text files into the GeneXplain platform, converted the Ensemble/Entrez ID into gene symbols, and selected the “DESeq2” package to normalize RNA-seq counts.

Principle component analysis and hierarchical clustering

We assessed NAFLD genomic data by comparing it to healthy controls and removed ~5% of cases due to their ambiguous behavior in the principal component analysis (Supplemental Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Additionally, we performed a hierarchical gene cluster analysis. The clustering is based on the Euclidean distance with complete linkage and enabled an assessment of co-regulated genes across different pathways in patients with NAFLD. Based on the dendrogram, we identified outliers, which appeared intermingled with controls. Such data were dismissed and included samples labelled as controls but reported pathology findings.

DEG analysis

We used LIMMA and the hypergeometric test to determine significantly regulated genes (Supplemental Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Similarly, for RNA-seq, we selected the “DESeq2” package, which estimates variance-mean dependence in count data. DEGs were defined by negative binomial distribution.17 We considered DEGs corrected for false discovery rate < 0.05 and p-value < 0.05 and computed fold change of DEGs. We compared DEGs with fold change ≥ 2 across different platforms and regarded the percentage of overlapping DEGs between independent studies as a measure of reproducibility.

Functional enrichment analysis

We employed Metascape (https://metascape.org/)18 to search for enriched gene ontology terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. We evaluated enriched terms with a p-value < 0.01 for upregulated and downregulated DEGs separately.

Hepatic steatosis-associated gene regulations

We reported 284 mechanistically linked lipid droplet (LD)-associated gene regulations,11 which code for lipogenesis, lipid transport, LD growth and/or endoplasmic reticulum stress, fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial stress, inflammation, glucose metabolism, and biomarkers. We compared the genomic data of 418 liver biopsies against the LD-associated DEGs.

RESULTS

Figure 1 depicts the workflow and we summarize basic patient characteristics in Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263. The average age is 44.5 and 49.8 years for males and females and the body mass index is 29.4 and 38.5. For 249 patients, the body mass index was not reported, and for 68 cases information regarding histological grades of NAFLD was missing. Finally, we considered 350 patients based on NAS-scores, of which 114 and 236 cases, respectively, are NAFL and NASH cases (Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Additionally, we considered cases with divergent disease scores (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263), and addressed the question of whether different scoring systems would have an inference on genomic data reproducibility. Additionally, we compared liver biopsy findings based on identical grades of fibrosis (Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263).

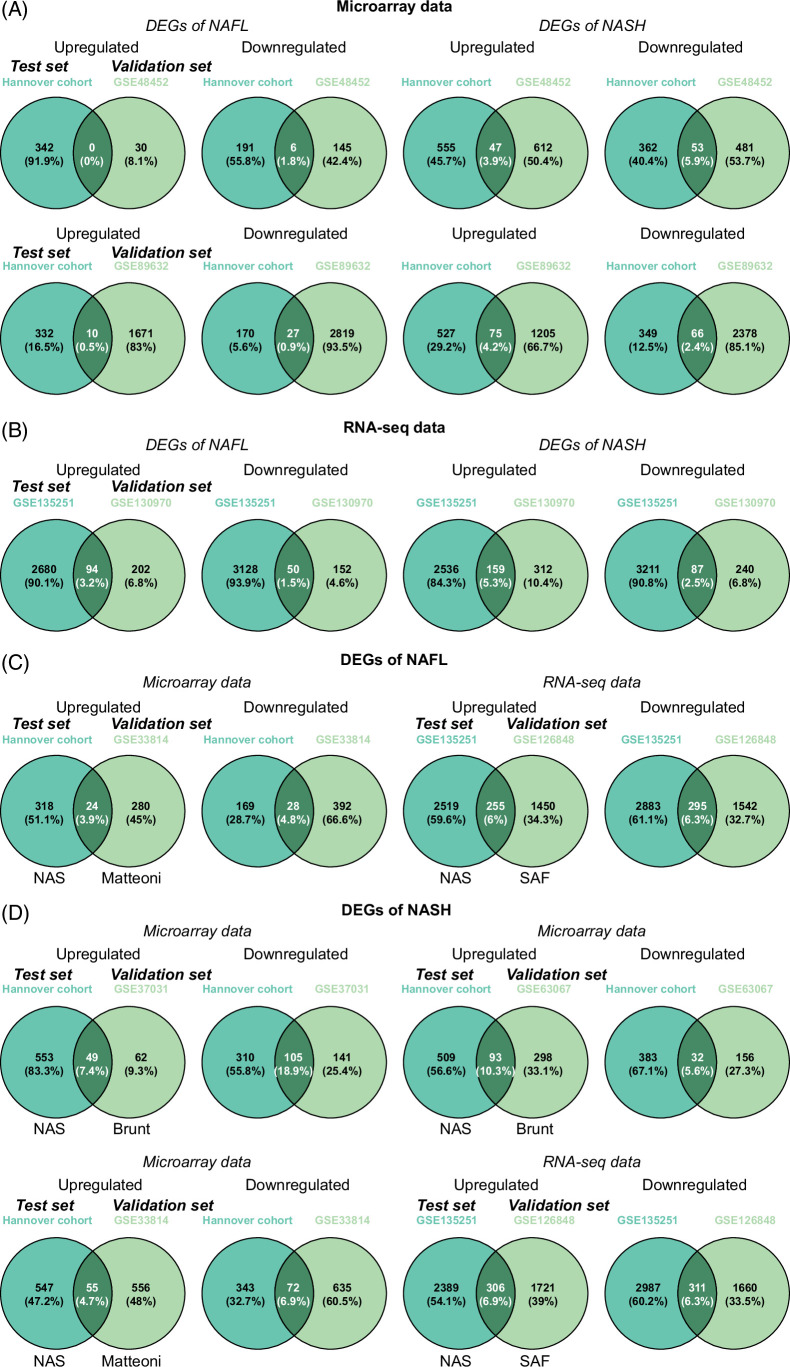

Genomic data reproducibility across independent studies

We evaluated data reproducibility by 2 independent methods. To exclude platform bias, we considered data reproducibility for each platform separately, that is, Affymetrix/Illumina microarrays and RNA-seq. Figure 2 shows Venn diagrams for test and validation sets, and for patients with NAFL, 0% and 0.5% for upregulated and 1.8% and 0.9% for downregulated DEGs are reproducible between the different studies (Figure 2A). Similarly, there are 3.9 and 4.2% for upregulated and 5.9 and 2.4% for downregulated DEGs in common between test and validation sets among patients with NASH (Figure 2A). The results show a lack of reproducibility among 74 patients with NAFLD (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Likewise, we considered the reproducibility of DEGs based on RNA-seq data for 276 cases. We observed 3.2% and 5.3% for upregulated and 1.5% and 2.5% for downregulated genes in common for NAFL and NASH cases (Figure 2B). Therefore, and irrespective of the technology used, the reproducibility of NAFLD-regulated genes is extremely low across 350 patients.

FIGURE 2.

Reproducibility of DEGs in patients with NAFL and NASH, respectively. (A) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in microarray data between test and validation sets. (B) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in RNA-seq data between test and validation sets. (C) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs between test and validation sets in patients with NAFL based on the different disease scoring systems. (D) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs between test and validation sets in patients with NASH based on the different disease scoring systems. Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed genes; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

Additionally, we addressed the question whether different scoring systems but comparable disease activity would have an inference on genomic data reproducibility. First, we compared patients graded by Matteoni type I and II and NAS ≤ 3. Similarly, we evaluated SAF < 2 and NAS ≤ 3 cases. As shown in Figures 2C, 3.9% and 6% of upregulated and 4.8% and 6.3% of downregulated DEGs are common between the 2 data sets. Additionally, we examined Brunt grade 2 and 3, Matteoni type III and IV, and NAS ≥ 4 in addition to SAF = 2 and 3 and NAS ≥ 4. As shown in Figure 2D, the reproducibility ranged between 4.7% and 10.3% for upregulated and 5.6% to 18.9% for downregulated DEGs. Given the overall poor reproducibility of DEGs, we considered differences due to histological classifications as of little relevance for data reproducibility.

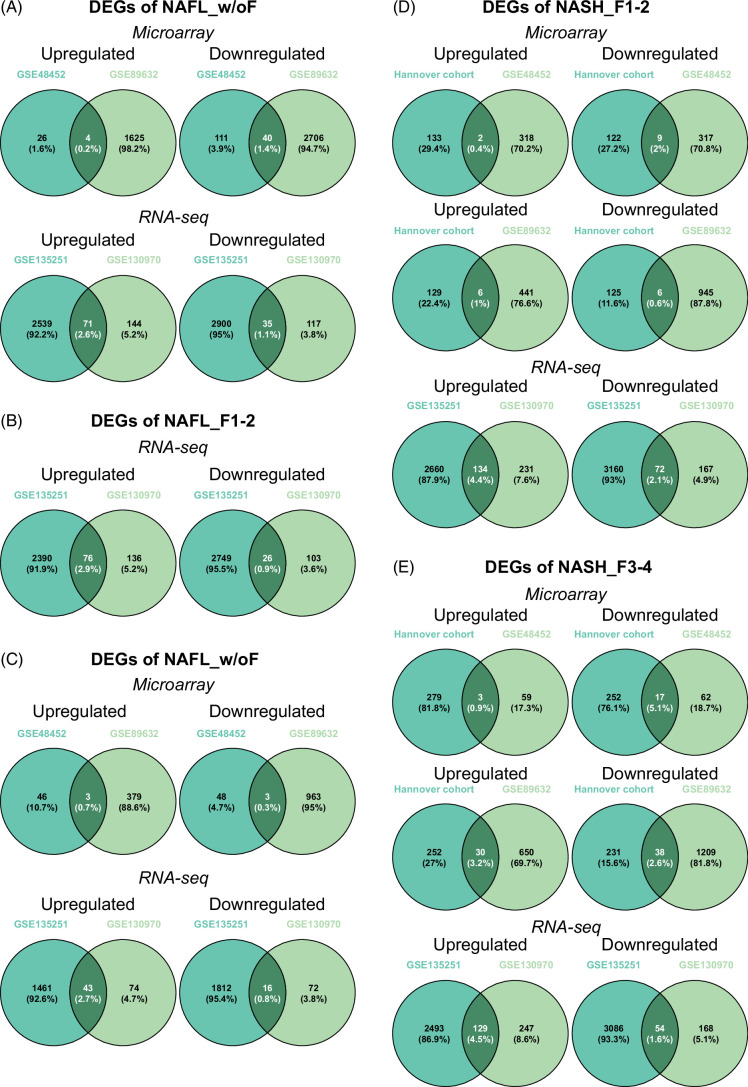

Next, we searched for commonalities between comparable fibrosis cases. For NAFL without fibrosis (NAFL_w/oF), there are 0.2% and 2.6% of upregulated and 1.4% and 1.1% of downregulated DEGs in common between microarray and RNA-seq studies (Figure 3A). Similarly, there are 2.9% for up and 0.9% for downregulated DEGs in common among NAFL fibrosis grades 1 and 2 (NAFL_F1-2, Figure 3B), while for NASH without fibrosis (NASH_w/oF) only 0.7% and 2.7% for up and 0.3% and 0.8% for repressed DEGs are in common (Figure 3C). Subsequently, we compared NASH cases with grades 1-2 (NASH_F1-2) and 3-4 (NASH_F3-4). For F1-2 cases, DEGs commonly upregulated are 0.4% to 4.4%, and for repressed ones, 0.6% to 2.1%. Equally, for F3-F4 cases, 0.9% to 4.5% of upregulated and 1.6% to 5.1% of downregulated DEGs are in common (Figure 3D-E). Overall, the reproducibility of disease-associated gene regulations is very poor, irrespective of fibrosis grades.

FIGURE 3.

Reproducibility of DEGs in NAFL and NASH with identical stages of fibrosis. (A) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in NAFL without fibrosis (NAFL_w/oF) between 2 independent studies. (B) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in NAFL with fibrosis=1–2 (NAFL_F1–2) between 2 independent studies. (C) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in NASH without fibrosis (NASH_w/oF) between 2 independent studies. (D) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in NASH with fibrosis=1–2 (NASH_F1–2) among different independent studies. (E) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in NASH with fibrosis=3–4 (NASH_F3–4) among different independent studies. Abbreviation: DEG, differentially expressed genes.

Supplemental Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264, shows the reproducibility of DEGs across NAS ≤ 3 and NAS ≥ 4 with different fibrosis grades. We compared 235 patients with NAS ≥ 4 of which 154 are staged F ≥ 2 while the remining 81 are F ≤ 1. Furthermore, we evaluated 112 patients with NAS ≤ 3 of which 55 and 57, respectively, are F ≥ 1 or F = 0. Overwhelmingly, we noted poor reproducibility of genomic data across 5 independent studies, even though the comparisons are based on identical NAS-scores and fibrosis grades.

We also investigated data reproducibility based on gender (Figure 4A and B). For females, 0.9%–10.4% of upregulated and 0.9%–5.7% of downregulated genes are common based on 36 microarray and 52 RNA-seq data. Similar results were obtained for males, that is, 0.4%–9% of upregulated and 2.1%–4.8% of repressed DEGs are common. While this comparison is based solely on sex, we also considered data reproducibility among NAFL and NASH cases separated by sex (Supplemental Figure S4A and B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Among females, 0.5% to 1% of upregulated and 0.8% to 3.9% of downregulated genes are common in NAFL and NASH cases. The results for males are very similar (Supplemental Figure S4B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Collectively, the reproducibility of DEGs between patients is extremely poor, irrespective of sex and disease scores.

FIGURE 4.

Gender difference in gene expression of NAFLD biopsies. (A) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in female patients with NAFLD between 2 independent studies, separately by microarray and RNA-seq. (B) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs in male patients with NAFLD between 2 independent studies, separately by microarray and RNA-seq. (C) Venn diagrams of regulated DEGs between male and female patients with NAFLD. (D) The bar chart shows the patient size of the top 10 high-frequent commonly upregulated/downregulated DEGs in male and female patients with NAFLD. (E) The bar chart shows the patient size of oppositely regulated DEGs between male and female patients with NAFLD. (F) The heatmap represents gender-specific regulated DEGs with > 3-fold changes in > 10% of patients with NAFLD. Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed genes; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

Sex-specific gene regulations

For 175 patients, the sex was reported. Therefore, irrespective of DEG reproducibility and disease score, we compared genomes of 86 males and 89 females. Figure 4C shows that 53.4% and 61.7% of upregulated and downregulated DEGs are common between both genders. Next, we applied the rule that ≥ 50% of patients must express the same DEG with ≥ 3-fold change. This defined 20 commonly regulated genes (Figure 4D). Meanwhile, we considered sex-specific gene regulations and found 25.7% and 20.9% of upregulated and 23.2% and 15.1% of downregulated DEGs as male and female specific (Figure 4C). We describe their function in file Supplemental S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I265.

Second, we searched for disease score and sex-specific gene regulations separated by disease severity and requested genes to be commonly regulated in ≥ 2 independent studies. For NAFL, none of the sex-specific DEGs qualified (Supplemental Figure S4D, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Notwithstanding, expression of CCL19, ITGBL1, and nexilin was specifically upregulated in NASH-females, while complement C1QA and VSIG4 were explicitly downregulated in NASH-males.

CCL19 is of key importance in chronic inflammation.19 It binds to chemokine receptor 7 and mice lacking CCL19-CCR7 signaling are protected from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance.20 CCL19 is produced by macrophages, dendritic, and other immune cells21 and stimulates homing of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.22 Blocking its activity improved NAFLD by inhibiting TLR4/NF‑κB‑p65 signaling,23 while upregulation of ITGBL1 promotes inflammation in NASH.24 Furthermore, nexilin facilitates cell adhesion and cytoskeleton organization, and its regulation was independently confirmed for severe NAFLD.25

Conversely, mice lacking C1AQ are protected from high-fat diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance and impaired glucose homeostasis.26 Moreover, inhibition of Vsig4 attenuated macrophage-mediated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in high-fat diet-challenged mice.27 Together, we observed gender differences in immune gene regulations, and the results are relevant in the pathogenic sequelae of NASH.

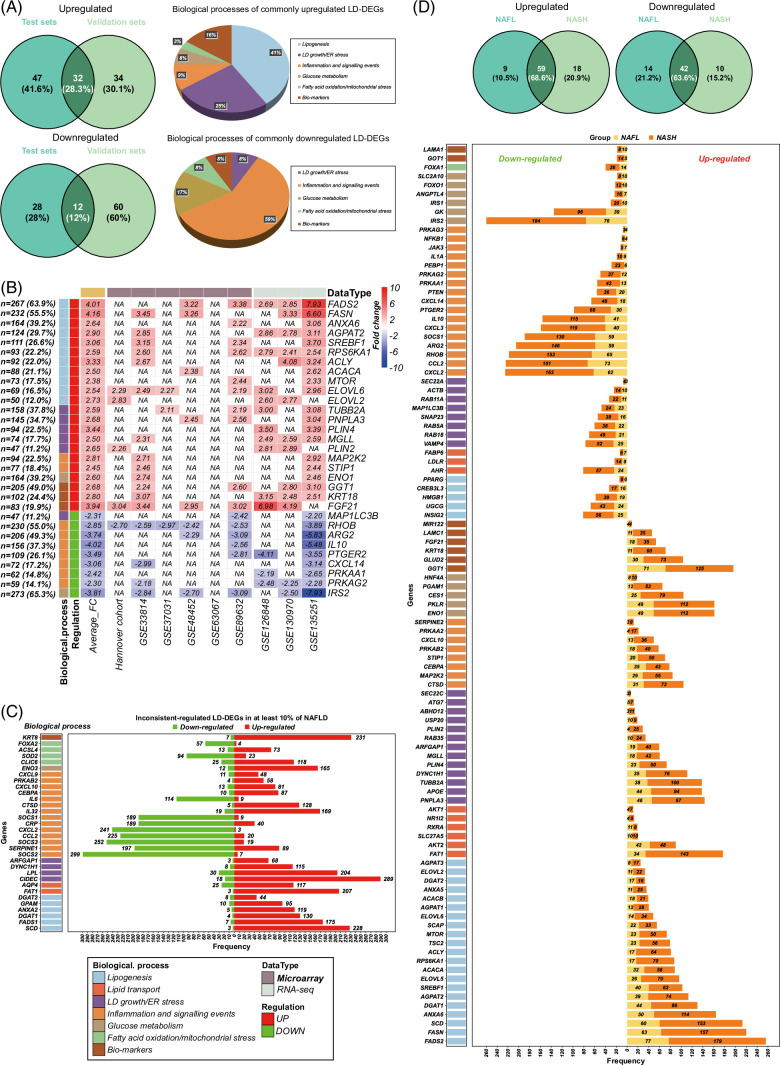

LD-associated DEGs

As shown in Figure 5A, and based on 284 LD-associated genes11 (Supplemental Table S4, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263), we identified 28% of upregulated and 12% of downregulated DEGs as commonly regulated. Figure 5B shows examples of LD-associated DEGs in > 10% of patients. For instance, fatty acid desaturase 2, fatty acid synthase, RAS homolog family member B, and insulin receptor substrate 2 are regulated in > 50% of patients and function in lipid metabolism and insulin signaling. Notwithstanding, 32 LD-associated DEGs are inconsistently regulated in > 10% of patients, as exemplified for suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, C motif chemokine ligand 2, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (Figure 5C). Moreover, we searched for LD-DEGs between NAFL and NASH (Figure 5D) and found 66% in common between them. Together, we obtained better reproducibility of genomic data based on mechanistically linked and LD-associated gene regulations.

FIGURE 5.

Lipid droplets associated DEGs (LD-DEGs) in patients with NAFLD. (A) Venn diagrams of upregulated and downregulated LD-DEGs in patients with NAFLD. Compare are test and validation sets and the pie plots show biological processes of commonly upregulated and downregulated LD-DEGs in both sets. (B) The heatmap shows the commonly regulated LD-DEGs in both sets with significant changes in > 10% of patients. (C) The bar chart represents the size of patients of inconsistently regulated LD-DEGs in patients with NAFLD. (D) Venn diagrams of upregulated and downregulated LD-DEGs in patients with NAFL and NASH, respectively. The bar chart shows the common LD-DEGs in patients with NAFL and NASH. Abbreviations: FADS2, fatty acid desaturase 2; FASN, fatty acid synthase; DEG, differentially expressed genes; IRS2, insulin receptor substrate 2; LDs, lipid droplets; RHOB, RAS homolog family member B; SREBF1, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1.

Validation of a NASH fibrosis gene signature

Recently, Govaere and colleagues reported 25 gene signatures for NASH and fibrosis28 whose expression changed with progressive disease. The authors entrained the signature on 58 NAS ≤ 3 and 158 NAS ≥ 4 cases and reported a gradual increase for 24 genes. To independently confirm the results, we evaluated the signature genes across 87 NAS ≥ 4 cases and different fibrosis grades (Supplemental Figure S5B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Based on the paradigm of ≥ 50% of patients showing changes in signature genes, and except for AKR1B10 and CCL20, none were regulated. In other words, 23 genes failed, and therefore > 90% of signature genes cannot be validated in an independent cohort of 87 NASH cases. By relaxing the threshold to ≥ 10%, we observed 10 signature genes; however, some are oppositely regulated (Supplemental Figure S5B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Together, only 2 NASH signature genes were confirmed in > 50% of patients.

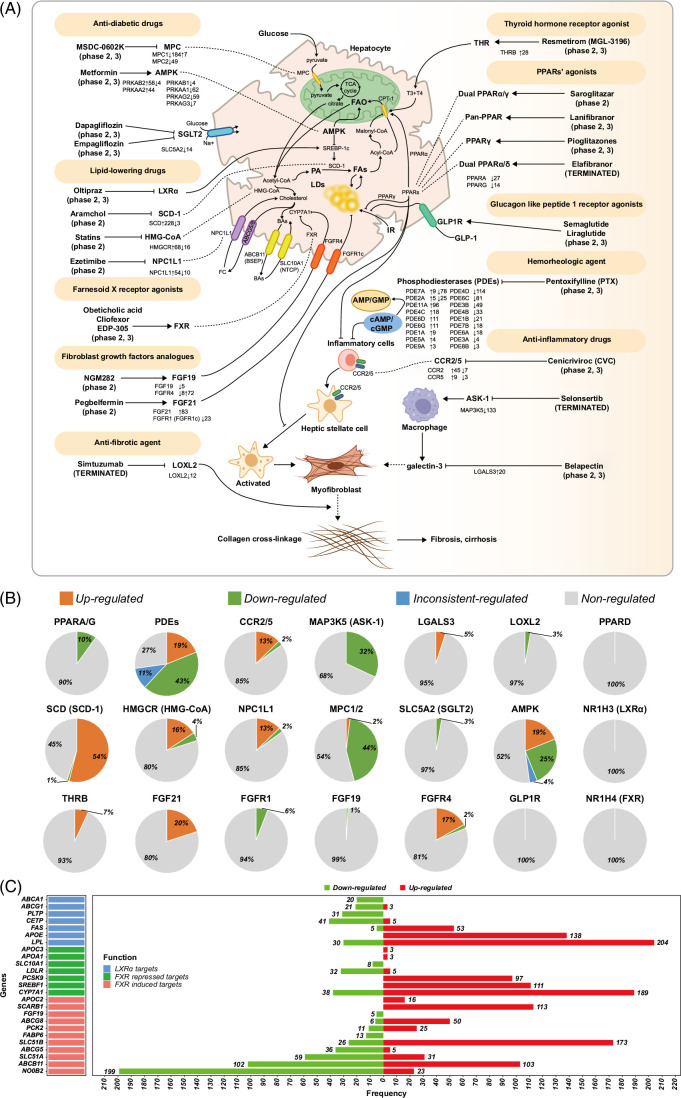

Regulation of drug targets

At present, > 20 drugs are evaluated in nearly 300 clinical trials. Strikingly, most drug candidates fail.29,30 To better comprehend drug failures, we considered transcriptional regulation of drug targets and compiled results for 18 drug targets in Supplemental Tables S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263 & S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263. We use the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier to report study findings.

Figure 6A depicts principal drug targets and Figure 6B informs on their regulation across 418 cases. Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264 & S7, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264, informs on their regulation in NASH. Outstandingly, the majority of drug targets are not regulated. For instance, Figure 6C depicts genes targeted by the farnesoid-X receptor (FXR). Cilofexor, EDP-305, and obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) are FXR-agonists. Although FXR itself is not regulated (Figure 6B), some of its target genes, that is, the nuclear orphan receptor SHP (nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 2) and ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 11 are significantly upregulated in 199 and 102 patients. Therefore, FXR is functional (Figure 6C). However, for 23 and 103 patients, we observed downregulation of nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 2 and ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 11 with important implications for drug treatment responses. There is strong evidence for nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 2 repression to reduce diet-induced liver steatosis; however, it exacerbates liver inflammation and fibrosis31 while repression of the bile salt transporter ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 11 causes cholestasis and impairs fatty acid β-oxidation.32 Importantly, obeticholic acid improved NASH fibrosis grades F=2 and 3 but its treatment-emergent serious adverse events were higher as compared to placebo (NCT02548351, Supplemental Table S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Apart from safety concerns, obeticholic acid did not meet the primary end point of NASH resolution, and the Food and Drug Administration warns of serious liver injury in patients with primary biliary cholangitis for which the drug has been approved.

FIGURE 6.

Drug targets regulation in patients with NAFLD (A) The role of drug candidates and differential regulation of targeted genes in patients with NAFLD across 18 drug targets. (B) Pie plots represent the percentage of patients with upregulated, downregulated, inconsistently regulated, and nonregulated drug targets in patients with NAFLD. (C) The bar plot shows the size of patients with significant regulation of LXR and FXR target genes in patients with NAFLD. Abbreviations: BA, bile acids; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; FC, free cholesterol; FXR, farnesoid-X receptor; IR, insulin resistance; LD, lipid droplet; LXR, liver X receptor; MAP3K5, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; PA, palmitic acid; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, tetraiodothyronine; SLC5A2, solute carrier family 5 member 2.

Given that FXR also functions as a transcriptional repressor, we analyzed the expression of genes typically repressed by FXR, that is, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, cytochrome P450 family 7 subfamily A member 1, and sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1; however, we found them upregulated in 97, 189, and 111 cases (Figure 6C). Obviously, the results are highly variable with inconsistent regulation of FXR target genes. Meanwhile, liver X receptor alpha inhibitors are explored, but we did not observe its disease-associated regulation. Nonetheless, some of its target, that is, lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein E, were upregulated in 204 and 138 cases (Figure 6C). We also examined regulation of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1R), which is the target of semaglutide and liraglutide, and observed its expression in 43% of cases. However, GLP1R is not significantly regulated. Note that GLP1R functional activity in hepatocytes is the subject of an ongoing debate33; nonetheless, its disease-associated regulation was reported34,35. Semaglutide failed in patients with NASH and compensated cirrhosis (NCT03987451, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Neither did the drug improve fibrosis nor NASH resolution. Another example relates to the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-agonists lanifibranor, saroglitazar, and pioglitazones, which entered phase 2/3 clinical trials. As shown in Figure 6A & B, only a few patients showed altered PPARα and PPARγ expression levels and PPARβ/δ was unchanged. Interestingly, the dual PPARα/δ agonist elafibranor proved beneficial for some patients with NASH (NCT01694849, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) but did not meet the primary end point of the GOLDEN-505 Investigator Study Group (NCT02704403, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Despite lack of efficacy in NASH, the drug received breakthrough designation for primary biliary cholangitis, and phase 3 results are positive.

A further example relates to phosphodiesterase (PDEs) inhibitors. Pentoxifylline inhibits PDEs, which causes increases in intracellular cAMP levels. The expression of PDE genes varied greatly (Figure 6A & B), and clinical studies failed to demonstrate therapeutic benefit (NCT00267670, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). There are 21 PDE genes, and due to alternate splicing code for > 100 proteins.36 Clearly, this demonstrates the complexity of this target. Nonetheless, Pentoxifilline is approved for occlusive arterial disease and intermittent claudication.

We evaluated the expression of chemokine receptor type-2 and 5 (CCR2/5), and cenicriviroc inhibits its signaling in macrophages and T cells. Preclinical studies provided strong evidence for CCR2/CCR5 inhibition to ameliorate alcohol-induced steatohepatitis and liver damage.37 However, the AURORA trial was prematurely terminated due to a lack of efficacy (NCT03028740, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Here, we show for a subset of patients, that is, 13% and 2%, respectively upregulation and downregulation of CCR2 and 5 (Figure 6B).

Clinical trials with selonsertib, that is, an inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5) failed because of lack efficacy (NCT03053050, NCT03053063, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) We solely observed repression of ASK1 while for 68% of cases it was unchanged (Figure 6A & B). Likewise, belapectin targets galectin-3, and this lectin and death-associated molecular pattern signal is secreted by monocytes and macrophages.38 It supports inflammatory responses. Galectin-3 is upregulated in 5% of mainly NASH cases (Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264) but unchanged in 95% of patients (Figure 6B). Our findings provide a rational for its failure in clinical trials (NCT02462967, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263).

Simtuzumab inhibits lysyl oxidase-like 2, which blocks the cross-linkage of collagen fibers.39 Lysyl oxidase-like 2 is regulated in 3% of cases, and its consistent downregulation is counterintuitive given its mode of action. Simtuzumab failed in clinical trials in cases with bridging fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis (NCT01672879, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263)

Moreover, lipid-lowering drugs targeting liver X receptor alpha, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD-1), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase, and Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 (NPC1L1) are evaluated (Figure 6A). We found stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD/SCD-1) induced in 54% (228/418) of cases (Figure 6A & B). Importantly, the SCD/SCD-1 inhibitor arachidyl amido cholanoic acid (Aramchol) proofed beneficial at the 600mg dose (NCT02279524, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) and entered phase 3 trials (NCT04104321, Supplemental Table S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Our results agree with clinical findings.

Likewise, inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA) and cholesterol transporter NPC1L1 were explored, but only 13% and 16%, respectively, of patients showed upregulation of NPC1L1 and HMG-CoA. Moreover, we identified 2% and 4% of patients with repressed expression levels (Figure 6A & B). Simvastatin failed in NASH as judged by histology of repeat liver biopsies following treatment periods of 12 months.40 Conversely, the NPC1L1 inhibitor ezetimibe improved liver histology but impaired hepatic long-chain fatty acid oxidation. Moreover, ezetimibe caused insulin resistance and significantly elevated HbA1c.41

Given the interrelationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and NAFLD, metformin is an interesting drug candidate, especially in patients with diabetes. However, metformin itself does not directly affect hepatic steatosis and inflammation. In fact, the drug stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase for glucose and cellular energy sensing.42 Several subunits of AMP-activated protein kinase are repressed, whereas protein kinase AMP-activated non-catalytic subunit beta 2 and protein kinase AMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha 2 are upregulated in about 10% of cases (Figure 6A). Importantly, the latter gene codes for the catalytic subunit. Although 1 study reported improved liver histology and alanine transaminase serum biochemistry in 30% of NASH cases, other studies failed to demonstrate metformin therapeutic benefit (NCT00303537, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). So far, larger clinical trials are missing, and the complex regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase in NAFLD is a substantial hurdle. Even so, there may be a role for metformin in preventing disease progression, especially in NASH-related HCC.43 Moreover, the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibitor MSDC-0602K failed to improve liver histology in biopsy-proven NASH cases following 1-year treatment periods (NCT02784444, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). With the exception of very few cases (1.6%), we observed repression of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 (44%) and mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 (12%) (Figure 6A).

Dapagliflozin and empagliflozin inhibit sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter solute carrier family 5 member 2, and the drugs are approved for the treatment of T2DM, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. We found solute carrier family 5 member 2 transcript expression unchanged in 97% of cases (Figure 6B). Nonetheless, clinical trials reported improvement in liver biochemistry readings of patients with T2DM with NAFLD (NCT02686476, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Unfortunately, liver histology was not examined, and therefore the findings remain inconclusive, but ongoing phase 4 trials include biopsies (NCT05254626, NCT04639414, Supplemental Table S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) for histological endpoints.

We investigated the expression of FGF, and NGM282 demonstrated improved liver histology of NASH cases following 12 weeks of treatment (NCT02443116, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). FGF19 signals through the FGFR4, and we identified 72 and 8 patients, respectively, with induced and repressed expression of this receptor. As shown in Figure 6A, most patients do not change FGF19 expression even though there are 5 cases with repressed transcript levels, and for these patients, FGFR4 was unchanged. Furthermore, NGM282 effectively suppressed toxic bile acid production with obvious implications for its use in PSC.44 It also reduced liver fat content (NCT02443116, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263). Pegbelfermin is a synthetic FGF21 that signals through FGFR1c, and 20% of patients showed induced FGF21 expression (range 2–21-fold), but FGFR1c was repressed among 23 cases (Figure 6A). Clinical data demonstrated reduced liver fat content (NCT02413372, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) but did not include liver histology. The FALCON trial defines ≥ 1 stage improvement in fibrosis without NASH worsening at week 48 (NCT03486899, NCT03486912, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263) as the efficacy end point and the publication of findings is pending.

Lastly, the thyroid hormone receptor-β-selective agonist resmetirom received breakthrough therapy designation. We observed upregulation in 7% of cases (Figure 6B). Clinical trials demonstrated safety and reduced liver fat content of resmetirom at 80 and 100 mg in patients with NASH (NCT02912260, NCT03900429, Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263 & 6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I263)

DISCUSSION

Our study followed 2 aims, first, an assessment of data reproducibility of genomic findings across 9 independent studies, and second, consistency of drug target regulation in patients with NAFLD.

Overwhelmingly, the reproducibility of DEGs in patients with similar histology is exceptionally low, even though we carefully controlled bias for sex and disease scores. Furthermore, we cross-validated results by 2 independent methods. Therefore, a major challenge lies in the confirmation of DEGs across diverse patient populations, which are characterized by heterogeneity of the disease and a range of comorbidities, notably T2DM and the metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, as well as “host” factors, that is, lifestyle patterns. Remarkably, when we compared 284 mechanistically linked and LD-associated DEGs, the data became more reproducible across different studies, and this underscores the importance of considering mechanistically linked DEGs. In the past, we already demonstrated the utility of such an approach.10–12,45

Importantly, the lack of data reproducibility is primarily influenced by interpatient variability. We compared patients based on identical disease scores and discovered important gender-dependent differences in lipid metabolism and immune response. The importance of gender differences in NAFLD is the subject of a recent review.46 With females, we noticed induced inflammatory response, Ag presentation and processing while several immune response genes are downregulated in males. Notwithstanding, extracellular matrix receptor interactions are specifically upregulated in males (Supplemental Figure S8, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264). Our findings agree with histological features of NAFLD whereby premenopausal women present more severe hepatocyte injury and inflammation when compared to men but have a lower risk of fibrosis.47 Together, high interpatient variability is a major reason for the lack of consistency of data, and the gene expression changes are not fully related to the severity of liver disease but the pathogenic phenotype. Our findings validate clinical observations with high variability in patient presentations, disease courses, and outcomes.

Regulation of drug targets

A recent commentary in Gastroenterology addressed the question of why so many clinical trials in NASH fail.30 Several reasons contributed to the poor success of the many drug candidates entering clinical trials, and the authors clearly defined them. In regards to preclinical studies, inappropriate animal models, poor understanding of pathogenesis, and redundant mechanisms compensating for drug target modulation are important reasons for the high risk of selecting the “wrong” drug candidate. Likewise, difficulties to extrapolate animal data to human disease, underpowered clinical studies and high false discovery rates in phase 2 studies, heterogeneous patient population with multiple pathogenic processes, lack of complete disease understanding, and the specific role of drug targets in the pathogenic process of NAFLD are significant constrains.

We investigated 18 drug targets across 418 liver biopsies. Overwhelmingly, most drug targets are not regulated or show opposite regulation in subpopulations. For instance, the regulation of PPARs’ isoforms was unchanged in ≥ 90% of cases and similar results were obtained for FGF19 and FGF21 and its receptors (Figure 6). A further example relates to liver X receptor and FXR, both of which are unchanged, and for some patients, downstream target genes of the receptors are oppositely regulated (Figure 6C). Given the vast heterogeneity in drug target expression, and without biomarkers, it will be extremely difficult to identify patients who will benefit from a given treatment, that is, drug “responders” from “nonresponders”. In fact, the current diagnostic possibilities, that is, ultrasound imaging and blood biochemistries are unable to identify eligible patients for a given drug treatment and to predict treatment response.

Consequently, it is of no surprise, that selonsertib failed in clinical trials. The drug target is repressed in > 30% of patients, which is counterintuitive for an inhibitor of the coded protein. In fact, we did not identify a single patient with upregulated expression of this ASK1-inhibitor. We also predict cenicriviroc to fail in larger trails, given that CCR2 and CCR5 are only upregulated in 10% and 2% of patients. The only target which was > 50% regulated is SCD1 (Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264 & S7, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I264).

Study limitations

We wish to highlight the following caveats: First, the pathophysiology and etiology of NAFLD are complex, and the patient population is heterogeneous. Second, NAFLD is a dynamic disease, and therefore, a single liver biopsy may not capture the dynamic changes and may not even be representative of an entire liver.

Third, we evaluated 18 drug targets, and with the exception of SCD, most drug targets are not regulated in the majority of patients. While the lack of disease-dependent drug target regulations is an important finding, we did not establish a direct link between drug target regulations and drug failures. In fact, the molecular hepatic effects of drugs need to be related to the sum of metabolic effects, which, in turn, could have direct or indirect effects on the liver. Obviously, molecular stratification of patients can only be one aspect in clinical trials, and drugs can elicit extrahepatic effects, which might lead to hepatic benefits. Nonetheless, we and others demonstrated a direct link between hepatic steatosis, drug treatment, and outcomes in preclinical studies.10,12 Fourth, it would be highly desirable to confirm results based on liver biopsy from patients participating in clinical trials. This would allow us to establish a direct link between drug treatment, target response, and clinical outcome. For instance, GLP1R was not regulated in liver biopsies of patients with NAFLD; yet, its clinical benefits may be indirect through weight loss. Similarly, drugs like FGF21 and pan-PPAR agents can have extrahepatic effects which overall may result in hepatic benefits in clinical trials.

Fifth, the demonstration of drug target regulation by immunohistochemistry and posttranslational modifications, as exemplified for the ASK1 kinase inhibitor, are worthwhile. However, liver biopsies carry the risk of bleeding, and the competing interests for a tiny amount of tissue are important constraints.

In conclusion, the lack of genomic data reproducibility, the high interpatient variability, and the lack of disease-dependent drug target regulation provide a molecular rational for drug failures in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shifang Tang: Data acquisition and analysis; data interpretation and preparation of artworks. Jürgen Borlak: Conception and design of the study; data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Chinese Scholarship Council for their financial support.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) to Shifang Tang.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; CCR2, chemokine receptor type-2; CCR5, chemokine receptor type-5; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FXR, farnesoid-X receptor; GLP1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; HMG, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl; LD, lipid droplet; NAS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score; NPC1, Niemann-Pick C1-Like Protein 1; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; SAF, steatosis, activity, fibrosis; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Shifang Tang, Email: tang.shifang@mh-hannover.de.

Jürgen Borlak, Email: Borlak.Juergen@mh-hannover.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Carpenter DH, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Loomba R, et al. NAFLD: Reporting histologic findings in clinical practice. Hepatology. 2021;73:2028–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, Natarajan Y, Chayanupatkul M, Richardson PA, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1828–1837 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson N, Borlak J. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets in steatosis and steatohepatitis. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:311–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahini N, Borlak J. Recent insights into the molecular pathophysiology of lipid droplet formation in hepatocytes. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;54:86–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pouwels S, Sakran N, Graham Y, Leal A, Pintar T, Yang W, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD: A multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burra P, Becchetti C, Germani G. NAFLD and liver transplantation: Disease burden, current management and future challenges. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufour JF, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E, Harrison S, Loomba R, Paradis V, et al. Current therapies and new developments in NASH. Gut. 2022;71:2123–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breher-Esch S, Sahini N, Trincone A, Wallstab C, Borlak J. Genomics of lipid-laden human hepatocyte cultures enables drug target screening for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med Genomics. 2018;11:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahini N, Borlak J. Genomics of human fatty liver disease reveal mechanistically linked lipid droplet-associated gene regulations in bland steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Transl Res. 2016;177:41–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahini N, Selvaraj S, Borlak J. Whole genome transcript profiling of drug induced steatosis in rats reveals a gene signature predictive of outcome. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedossa P, Poitou C, Veyrie N, Bouillot JL, Basdevant A, Paradis V, et al. Histopathological algorithm and scoring system for evaluation of liver lesions in morbidly obese patients. Hepatology. 2012;56:1751–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matteoni C, Younossi Z, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu Y, McCullough A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luther SA, Bidgol A, Hargreaves DC, Schmidt A, Xu Y, Paniyadi J, et al. Differing activities of homeostatic chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 in lymphocyte and dendritic cell recruitment and lymphoid neogenesis. J Immunol. 2002;169:424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sano T, Iwashita M, Nagayasu S, Yamashita A, Shinjo T, Hashikata A, et al. Protection from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice lacking CCL19-CCR7 signaling. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:1460–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanagawa Y, Onoé K. CCL19 induces rapid dendritic extension of murine dendritic cells. Blood. 2002;100:1948–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan Y, Chen R, Wang X, Hu K, Huang L, Lu M, et al. CCL19 and CCR7 expression, signaling pathways, and adjuvant functions in viral infection and prevention. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Wang Y, Wu X, Tong P, Yue Y, Gao S, et al. Inhibition of CCL19 benefits non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB-p65 signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:4635–4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munger JS, Sheppard D. Cross talk among TGF- signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moylan CA, Pang H, Dellinger A, Suzuki A, Garrett ME, Guy CD, et al. Hepatic gene expression profiles differentiate presymptomatic patients with mild versus severe nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59:471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillian AD, McMullen MR, Sebastian BM, Rowchowdhury S, Kashyap SR, Schauer PR, et al. Mice lacking C1q are protected from high fat diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance and impaired glucose homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22565–22575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Sun JP, Wang J, Lu WH, Xie LY, Lv J, et al. Expression of Vsig4 attenuates macrophage-mediated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in high fat diet (HFD)-induced mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516:858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Govaere O, Cockell S, Tiniakos D, Queen R, Younes R, Vacca M, et al. Transcriptomic profiling across the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease spectrum reveals gene signatures for steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaba4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JYS, Chua D, Lim CO, Ho WX, Tan NS. Lessons on drug development: A literature review of challenges faced in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) clinical trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratziu V, Friedman SL. Why do so many nonalcoholic steatohepatitis trials fail? Gastroenterology. 2023;165:5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magee N, Zou A, Ghosh P, Ahamed F, Delker D, Zhang Y. Disruption of hepatic small heterodimer partner induces dissociation of steatosis and inflammation in experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:994–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Li F, Patterson AD, Wang Y, Krausz KW, Neale G, et al. Abcb11 deficiency induces cholestasis coupled to impaired β-fatty acid oxidation in mice. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24784–24794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Targher G, Mantovani A, Byrne CD. Mechanisms and possible hepatoprotective effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and other incretin receptor agonists in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta NA, Mells J, Dunham RM, Grakoui A, Handy J, Saxena NK, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is present on human hepatocytes and has a direct role in decreasing hepatic steatosis in vitro by modulating elements of the insulin signaling pathway. Hepatology. 2010;51:1584–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokomori H, Ando W. Spatial expression of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor and caveolin-1 in hepatocytes with macrovesicular steatosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7:e000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azevedo MF, Faucz FR, Bimpaki E, Horvath A, Levy I, de Alexandre RB, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of the phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Endocr Rev. 2014;35:195–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ambade A, Lowe P, Kodys K, Catalano D, Gyongyosi B, Cho Y, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of CCR2/5 signaling prevents and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and inflammation in mice. Hepatology. 2019;69:1105–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kram M. Galectin-3 inhibition as a potential therapeutic target in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis liver fibrosis. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puente A, Fortea J, Cabezas J, Arias Loste M, Iruzubieta P, Llerena S, et al. LOXL2-A new target in antifibrogenic therapy? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson A, Torres DM, Morgan AE, Fincke C, Harrison SA. A pilot study using simvastatin in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:990–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeshita Y, Takamura T, Honda M, Kita Y, Zen Y, Kato K, et al. The effects of ezetimibe on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and glucose metabolism: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2014;57:878–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK: Sensing glucose as well as cellular energy status. Cell Metab. 2018;27:299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wang H, Xiao H. Metformin actions on the liver: Protection mechanisms emerging in hepatocytes and immune cells against NASH-related HCC. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanyal AJ, Ling L, Beuers U, DePaoli AM, Lieu HD, Harrison SA, et al. Potent suppression of hydrophobic bile acids by aldafermin, an FGF19 analogue, across metabolic and cholestatic liver diseases. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Wang Y, Borlak J, Tong W. Mechanistically linked serum miRNAs distinguish between drug induced and fatty liver disease of different grades. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Ballestri S, Fairweather D, Win S, Than TA, et al. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: State of the art and identification of research gaps. Hepatology. 2019;70:1457–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang JD, Abdelmalek MF, Guy CD, Gill RM, Lavine JE, Yates K, et al. Patient sex, reproductive status, and synthetic hormone use associate with histologic severity of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:127–131.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.