Abstract

Clinicians and researchers are exploring safer and novel treatment strategies for treating the ever-prevalent Parkinson’s disease (PD) across the globe. Several therapeutic strategies are used clinically for PD, including dopamine replacement therapy, DA agonists, MAO-B blockers, COMT blockers, and anticholinergics. Surgical interventions such as pallidotomy, particularly deep brain stimulation (DBS), are also employed. However, they only provide temporal and symptomatic relief. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is one of the secondary messengers involved in dopaminergic neurotransmission. Phosphodiesterase (PDE) regulates cAMP and cGMP intracellular levels. PDE enzymes are subdivided into families and subtypes which are expressed throughout the human body. PDE4 isoenzyme- PDE4B subtype is overexpressed in the substantia nigra of the brain. Various studies have implicated multiple cAMP-mediated signaling cascades in PD, and PDE4 is a common link that can emerge as a neuroprotective and/or disease-modifying target. Furthermore, a mechanistic understanding of the PDE4 subtypes has provided perceptivity into the molecular mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PDE4Is). The repositioning and development of efficacious PDE4Is for PD have gained much attention. This review critically assesses the existing literature on PDE4 and its expression. Specifically, this review provides insights into the interrelated neurological cAMP-mediated signaling cascades involving PDE4s and the potential role of PDE4Is in PD. In addition, we discuss existing challenges and possible strategies for overcoming them.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Neurodegeneration, PDE4, cAMP, PDE4 inhibitors, Allosteric modulation

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a movement disorder that primarily affects the geriatric population, 15 out of 100,000 individuals are affected worldwide annually (Tysnes and Storstein 2017). Postural instability is a significant symptom, along with other moderate-to-milder motor symptoms such as akinesia, bradykinesia, tremor, and rigidity (Kalia and Lang 2015; Moustafa et al. 2016). Various non-motor abnormalities such as apathy, anhedonia, depression, cognitive dysfunction, sleep problems, and hallucinosis are also diagnostic of PD (Poewe 2008). Degradation of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) is majorly characterized in PD, which culminates in striatal dopamine depletion and intracellular deposition of alpha-synuclein (α-synuclein). At the molecular level, several pathways and processes are involved in the pathogenesis of PD, including α-synuclein protein homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium homeostasis, oxidative stress, axoplasmic flow, and neuroinflammation (Poewe et al. 2017). Current anti-parkinsonian drug treatment options include dopamine replacement therapy, dopamine (DA) agonists, monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) blockers, catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) blockers, and anticholinergics. Other treatments include surgical interventions such as pallidotomy, especially of the internal globus pallidus which is a deep brain stimulation (DBS) or subthalamic nucleus in the subthalamus, and stem cell transplant surgery (Yuan et al. 2010). However, no anti-parkinsonian therapy can arrest disease progression, whether administered alone or in combination. Hence, developing disease-modifying and neuroprotective agents is essential to halt PD. Currently, various strategies are being investigated for the treatment of PD. The inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes is one such approach (Martinez and Gil 2013; Nthenge-Ngumbau and Mohanakumar 2018; Erro et al. 2021). Hydrolysis of 3’ cyclic nucleotides, namely, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) are catalyzed by these enzymes and regulate their intracellular levels. Hence, the overexpression of PDEs in PD decreases intracellular cAMP levels and consequently affects dopamine receptor signaling. This is because dopamine receptors use cAMP, a second messenger, to transmit signals to effector proteins. PDEs are a superfamily of enzymes and 11 PDE isoenzymes have been identified, with PDE4 being the most abundant and widely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) (Lakics et al. 2010; Gavaldà and Roberts 2013).

PDE4 isoenzymes have been targeted to alleviate the pathophysiological causes of several neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (Kumar and Singh 2017; Sims et al. 2017; Kinoshita et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2019). In the present day, PDE4 inhibition has received increasing attention, and numerous Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PDE4Is) have been investigated in neurological and neurodegenerative experimental models and clinical trials (Prickaerts et al. 2017; Blokland et al. 2019a). By extensively analyzing and assessing the existing studies on the overall characteristics and expression of PDE4, its role in the multiple interrelated cAMP-mediated signaling pathways that contribute to PD pathophysiology, and a summary of investigational PDE4Is in PD as well as challenges and their overcome strategies; this review explores the prospect of inhibiting PDE4 isoenzyme as a potential disease-modifying target for PD.

Overview of PDE4 Isoenzymes

The PDE4 isoenzyme family contains four genes that mediate intracellular signaling: PDE4A, PDE4B, PDE4C, and PDE4D (Titus et al. 2014). The kinetic characteristics of PDE4s differentiate them from other cyclic nucleotide PDE enzymes, explicitly demonstrating their susceptibility to inhibition by rolipram, the first drug in the class of PDE4 inhibitors (Wachtel 1982). The discovery of rolipram has improved our understanding of the activities of PDE4 in the brain, generating massive lines of evidence and prompting significant research on neurological disorders, including schizophrenia and intracranial injury (Millar et al. 2005; Atkins et al. 2007). Therefore, exploring PDE4 concentrations and their role in neural activity throughout the CNS's neurogenesis, growth, and pathology is crucial for both fundamental and translational research (Reyes-Irisarri et al. 2007; Mcgirr et al. 2016; Tibbo et al. 2019).

PDE4 inhibitors have been extensively studied for therapeutic potential for against neurological diseases (Heckman et al. 2016; Kinoshita et al. 2017; Bhat et al. 2020). PDE4 inhibitors such as roflumilast (Rhee and Kim 2020), apremilast (Young and Roebuck 2016), and crisaborole (Paton 2017) are currently endorsed by the US FDA for the management of inflammatory ailments, like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), psoriatic arthritis, and atopic dermatitis. Studies have shown that PDE4 inhibitors extend the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL17 and IL-23) and interferon- gamma (IFN-γ), while augmenting the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 during the inflammation (Schafer et al. 2010; Keating 2017; Li et al. 2018; Nguyen et al. 2022). Neuroinflammation involved in the progression of PD (Troncoso-Escudero et al. 2018). Therefore, PDE4 inhibitors appear to be effective in attenuating neuroinflammation. (Ghosh et al. 2012).

PDE4 Isoenzyme Genetics

The Drosophila dunce gene in D. melanogaster was the first cyclic nucleotide PDE gene to be characterized as the PDE4 enzyme family (Chen et al. 1986). Subsequently, the discovery of rodent orthologous genes (Swinnen et al. 1989) revealed four PDE4 paralogous genes in mammalian genomes on specific chromosomes (Colicelli et al. 1989). The human PDE4 paralogous genes PDE4A, PDE4B, PDE4C, and PDE4D have been reported in distinct chromosomes, such as chr19p13.2, chr1p31, chr19p13.11, and chr5q12, respectively.

The PDE4 genes in Drosophila and mammals have numerous transcriptional units. For example, the human PDE4D locus mapping to 5q12 with a 150 kb genomic sequence has transcription units of a minimum of four. PDE4 isoenzymes are significant complex genes of approximately 50 kb, each with approximately 18 exons and introns that act as promoters, with a genomic sequence of 20 kb (Houslay 2001). Of these, seven exons are encoded in the core catalytic unit (Sullivan et al. 1999), regulatory domains are encoded by subsequent exons, and the N-terminal portions indicate their specific or unique isoforms (Houslay et al. 2007). In humans, because of their vast architecture, PDE4A, 4B, 4C, and 4D may consist of four or five transcripts, four transcripts, three transcripts, and five or more transcripts, respectively, totaling up to a minimum of 16 open reading frames (Conti et al. 2003).

Structural Characterization and Functionality of PDE4 Isoenzymes

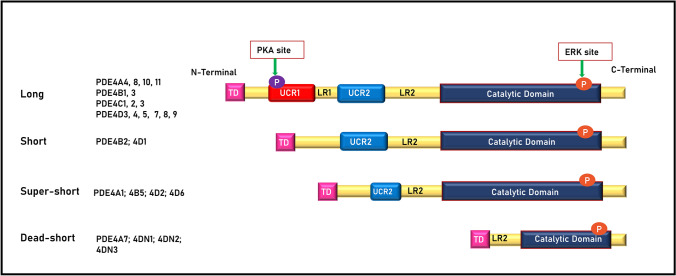

Structurally, PDE4s comprised a catalytic domain and a domain that exhibits regulatory functions. PDE4 produces three significant isoforms: long, short, and super-short. Based on the upstream conserved regions 1 and 2 (UCR1 with 55 amino acids and UCR2 with 76 amino acids (MacKenzie et al. 2002)) present in the N-terminal region, these three isoforms are produced, which are called targeting domains (TDs). UCR1 and 2 in the TDs are linked by linker region 1 (LR1) and TDs to the catalytic domain by LR2 (Bolger 1994). The PDE4 genes produce another isoform (fourth isoform), which has a dormant catalytic unit, truncated N- and C-terminals, and lacks UCRs. Hence, it was termed dead-short isoform (PDE4A7). Diverse isoforms result from alternative mRNA splicing using several promoters (Houslay 2001), and at least 20–25 protein variants have been reported (Conti et al. 2003). In humans, long isoforms have both UCR1 and UCR2 regions which are encoded by almost every PDE4 gene: PDE4A4 [named PDE4A5 in rodents (Naro et al. 1996)], PDE4A8, PDE4A10, PDE4A11, PDE4B1, and PDE4B3 [PDE4B4 long isoform is present in rodents but not functional in humans because of stop codons (Shepherd et al. 2003)]; PDE4C1, PDE4C2, PDE4C3, PDE4D3 PDE4D4, PDE4D5, PDE4D7, PDE4D8, and PDE4D9. The short isoforms consist of only UCR2, and PDE4 genes only encode subsets of them. The human PDE4 short isoforms are PDE4B2 and PDE4D1, and the super-short isoforms comprise the shortened UCR2, which are PDE4A1, PDE4B5, PDE4D2, and PDE4D6 (Johnston et al. 2004; Houslay et al. 2005). The variants such as PDE4DN1, PDE4DN2, and PDE4DN3 are dead-short forms due to the lack of a catalytic domain. (Paes et al. 2021). The structural highlights of the isoforms are shown in Fig. 1. The presence or absence of UCR1 causes structural differences between the long and short forms. In addition, functional differences between them have been reported, which include oligomerization, regulation of enzyme activity by allosteric binding of the ligands or post-translational modifications, and sensitivity to PDE4 inhibitors. Long PDE4 isoforms are mainly oligomerized by the UCR1 and UCR2 domains, whereas short PDE4 isoforms are monomers, and variations in their tetrad structures are sensitive to PDE4 inhibitors (rolipram) (Richter and Conti 2002, 2004).

Fig. 1.

Different isoforms of PDE4; long, short, super-short, and dead-short in humans. ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, LR1 and 2: Linker regions 1 and 2, PKA: Protein kinase A, TD: Targeting domains, UCR1 and 2: Upstream conserved regions 1 and 2

In PDE4, both UCR1 and UCR2 interact via ionic interactions to establish regulatory functions and modulate the operating output of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation (Baillie et al. 2000; Beard et al. 2000; MacKenzie et al. 2002). The cAMP-dependent PKA phosphorylation site preserved within the UCR1 domain is substantially consistent in all long isoforms, and phosphorylation activates long PDE4s, which in turn participate in the hydrolysis of cAMP (MacKenzie et al. 2002). Furthermore, all variants, except PDE4A, have a phosphorylation site for ERK in the catalytic domain that modulates hydrolysis in a variant-specific manner. Phosphorylation of ERK suppresses long-isoform PDE4 activity, inhibits or does not have any impact on super-short isoform PDE4 activity, and enhances short-isoform PDE4 activity (Zhang 2009). By altering ERK phosphorylation, an inhibitory effect on the N-terminal activation of the catalytic unit of PDE4 (PDE4D3) leads to the downstream PI3 kinase pathway, thus modulating the PDE4 long isoform activity. However, activation of ERK by oxidative stress causes the phosphorylation of Ser239Ala-PDE4D3, a mutant PDE4D3, at Ser579 and inhibits the long PDE4. Activation of the PI3 kinase pathway by oxidative stress leads to the phosphorylation of PDE4D3 at Ser239 via the involvement of an unknown kinase (Hill et al. 2006).

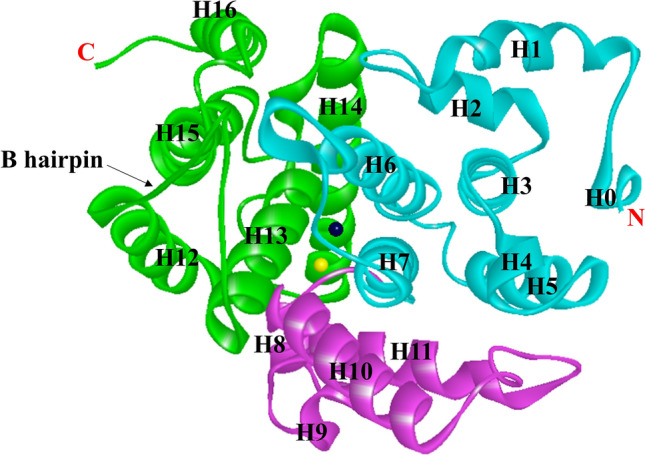

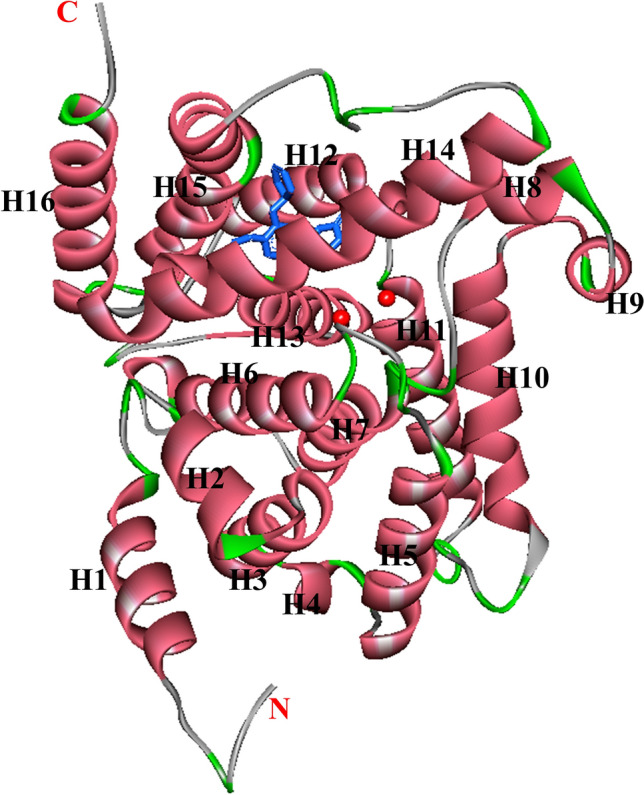

The catalytic domain of the PDE4B crystal structure consists of 17 helices interlinked by loops, with residues 152–528 being vital for binding to a substrate (Xu et al. 2000). The α-helices H1–H7, H8–H11, and H12–H16 are packed into three subdomains, allowing for distinct catalytic center conformational states. The α-helices (H-12 and H-13) in the third subdomain have an expanded loop of a β-hairpin (Fig. 2). In the asymmetric unit of PDE4B, two molecular residues, 496–508, form an additional α-helix, H17, which is packed against a neighboring molecule in the crystal (Xu et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2007). These subdomains combine to create a close-packed pouch that includes the cAMP binding active site. The catalytic bag has a capacity of 450 Å and accommodates 250 Å of cAMP molecules. In the rolipram-bound PDE4D crystalline structure analysis, the monomeric PDE4D2 molecule of 16 helices has a folding pattern similar to that of PDE4B, and the helical structural arrangement of residues: 496–508 in PDE4B coincides with 422–434 in PDE4D2, indicating that the active constituent of the PDE4 enzyme is the PDE4D2 tetramer (Huai et al. 2003b) (Fig. 3). The conformational alteration in the C-terminal residues of the PDE4 isoenzyme family and sequencing heterogeneity in all PDE isoenzymes suggest the paramount importance of the C-terminus in PDE hydrolytic activity (Huai et al. 2003b). The Hx3Hx24–26E sequences are two conserved regions that are zinc-binding motifs identified by sequencing the PDEs at the amino-terminal and are involved in catalysis (Vallee and Auld 1990; Wilcox 1996).

Fig. 2.

Ribbon presentation of the secondary structure of the catalytic unit of PDE4B2B (PDB ID, 1f0j) with residues 152–489. Cyan: 1st subdomain; magenta: 2nd subdomain, green: 3rd subdomain, dark grey: Zn, and yellow: Mg

Fig. 3.

Ribbon presentation of the catalytic unit of monomeric PDE4D2 (PDB ID, 1q9m). Rolipram: blue sticks, divalent metals: red balls

According to various biochemical studies, PDE's catalytic activity requires a divalent metal ion. Low amounts of these ions, notably nickel (Ni2 +), cobalt (Co2 +), manganese (Mn2 +), zinc (Zn2 +), and magnesium (Mg2 +), act as catalytic metal ions for PDE enzymatic activity. However, the number of zinc atoms that are essential for binding remains unclear. According to available reports, each PDE4A monomer requires one Zn2 + , Vibrio fischeri PDE, PDE4A requires two Zn2 + , and PDE5 requires three Zn2 + for activation (Ke 2004). Indeed, the interaction of two metal ions participating in the PDE4B catalytic reaction occurs in α-helices H6–H13. In addition, firmly bound Zn2 + and loosely bound Mg2 + are involved in establishing a catalytic pouch in the PDE4B crystal structure, both of which are critical for catalytic activity (Xu et al. 2000; Houslay and Adams 2003). [Mg2 +], along with the connections that clasp Mg2 + ions, are dominant and linked to amino acids on α-helices 10 and 11, which influences PDE4 activation during cAMP-dependent PKA phosphorylation (Conti et al. 2003). PDE4’s enzymatic site includes two metal ions separated by a distance of 3.9 Å, indicating that it interacts with both metal-binding regions concomitantly (Xu et al. 2000). The primary metal ion, along with His164 and His200 in the PDE4D2 isoform and Asp201 and Asp318 residues, is found at the base of the catalytic pouch (Corbin and Francis 1999). Since these metal-binding residues are part of all three PDE4 subdomains, it is evident that metal ions are involved in protein structure stabilization.

In the AMP-bound PDE4 structural study, the metal ions in PDE4 formed two different coordinates that were primarily involved in catalysis. One interacts with histidine: His164 and His200; aspartic acid residues: Asp201 and Asp318; and AMP's phosphate oxygen atoms of two, whereas the other interacts with aspartic acid residue: Asp318; AMP's phosphate oxygen atoms of two, and attached water molecules of three. Their interaction with phosphate oxygen plays a critical role in catalytic activity. Zinc is considered the first divalent metal ion to activate the enzyme at low concentrations, as it is dispersed in the reflective absorption range of the wavelength. The second divalent metal ion in PDE4D2 is associated with the D318 interaction, water molecule binding, and perhaps binding to the phosphate group of the substrate. Although the secondary divalent metal ion is unknown owing to its poor binding affinity at this site, biochemical studies imply that Mg2 + or Mn2 + is more likely to be one (Alvarez et al. 1995).

In the un-ligated PDE4B and PDE4D2 crystalline structures, cAMP's phosphate group forms hydrogen bonds with histidine (His160) and interacts with either one or both metal ions. These interactions polarize the phosphodiester bond, providing a phosphorus atom with a partial positive charge. Aspartic acid (Asp318) acts as a universal base to activate the bridging hydroxide ions for nucleophilic attack. Aspartic acid (Asp201) is close to nucleophilic attack and participates in the coordination of both metal ions. Hence, it plays a role in activation. Histidine (His160), which is approximately 4 Å away from AMP’s O3′ in the structure of PDE4D2-AMP, contributes a proton to O3′, thereby enhancing the polarization of the phosphodiester bond and facilitating nucleophilic attack. Moreover, the hydroxide ion on a metal-bound water molecule is activated via nucleophilic attack on the phosphor atom by the aspartic acid residues to assist catalysis. (Huai et al. 2003a).

PDE4 Isoforms’ Expression and Distribution in Periphery and CNS

In the human brain, the PDE4 isoenzyme predominates, is highly expressed, and can be a possible target in CNS disorders (Lakics et al. 2010; Maurice et al. 2014). They are ubiquitous in humans. All PDE4 isoforms are expressed in the brain, immunological cells, heart, lungs, and testes. PDE4A, PDE4B, and PDE4D subtypes are widely distributed in the human brain, with modest PDE4C levels in the cortex and cerebellar granule cells (Pérez-Torres et al. 2000) (Table 1). PDE4B plays an important role in striatal function. Its expression is highest in the substantia nigra compared to all existing PDEs and may be related to the etiology of PD in its dysfunctional state (Bateup et al. 2008; Lakics et al. 2010). Interestingly, in the 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-treated human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cell line, PDE4B overexpression was found to accelerate the progression of PD caused by elevated expression of nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) (Chen et al. 2021). PDE4B2, a variant of PDE4B, is also involved in neuroinflammation and is highly expressed in neutrophils, leukocytes, astrocytes, and monocytes (Wang et al. 1999).

Table 1.

Expression levels of PDE4 isoforms in various regions of the human body

| PDE4 Isoform | Expression levels | Peripheral regions | Brain regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDE4A | High | – | – |

| Moderate | – | Parietal cortex, temporal cortex | |

| Low | Skeletal muscle, stomach, thyroid gland | Cerebellum, frontal cortex, Basal ganglia, hypothalamus | |

| Very low | Urinary bladder, heart, kidney, lung, pancreas, intestine, spleen | Spinal cord, substantia nigra | |

| PDE4B | High | Spleen | Basal ganglia, Cerebral cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, substantia nigra, thalamic region |

| Moderate | Bladder, lung | Temporal cortex | |

| Low | Heart, skeletal muscle, thyroid gland | – | |

| Very low | Adrenal gland, kidney, liver, pancreas, small intestine, stomach | Dorsal root ganglia | |

| PDE4C | High | – | – |

| Moderate | – | – | |

| Low | – | – | |

| Very low | Heart, lung, skeletal muscle, skeletal muscle, spleen, stomach | Basal ganglia, hippocampus, hypothalamus, parietal cortex, temporal cortex | |

| PDE4D | High | – | – |

| Moderate | Bladder, skeletal muscle | – | |

| Low | Heart, kidney, thyroid gland | Frontal cortex, parietal cortex | |

| Very low | Liver, lung, pancreas, small intestine, spleen, stomach | Basal ganglia, Cerebral cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, substantia nigra, thalamic region |

mRNA expression range for very low is below 20%, low (20–40%), moderate (40–60%), and high (above 60%). Adapted from Lakics et al. (Lakics et al. 2010)

Different Neuronal Signaling Cascades Involving PDE4 Isoenzymes in PD

Several mechanisms are associated with the development of PD. These include lysosomal dysfunction, neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, and genetic mutations in SNCA, protein deglycase DJ-1, PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PARKIN), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase 1 (UCHL1), and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) (Klein and Westenberger 2012). Here, we discuss multiple interrelated cAMP-mediated signaling pathways involving PDE4 at the molecular level, whose disruption contributes to and promotes the progression of PD pathogenesis. The possible role of PDE4 inhibition in PD is further discussed in this section.

cAMP/PKA/CREB Signaling

PDE4s are cAMP-specific, meaning that they hydrolyze cAMP to AMP, thus regulating their intracellular accumulation. cAMP plays an essential part in synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP) (Menniti et al. 2006). The second messenger, cAMP, activates protein kinase A (PKA) and Epac1/2. cAMP has been reported to have equal binding affinities for PKA and Epac in vitro studies (Cheng et al. 2008). The activation of PKA leads to the phosphorylation of cAMP-binding response element protein (CREB) at ser133. The phosphorylation of this site enhances CREB target gene expression. Expressed Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a significant role in neuronal plasticity (Finkbeiner et al. 1997; Jabaris et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018). Studies by in vitro models have shown that dysregulation of cAMP-PKA signaling transduction is evident in PD (Sandebring et al. 2009; Dagda et al. 2011) as well as in vivo models (Mucignat and Caretta 2017), and post-mortem PD brain tissue (Howells et al. 2000). PKA-regulated gene dysregulation is associated with reduced levels of BDNF mRNA in neurons of the substantia nigra before degeneration (Howells et al. 2000). The mislocalization of phosphorylated-CREB (p-CREB) is associated with the etiology of PD, which is evident from numerous studies. For instance, a post-mortem PD brain tissue study showed some undesirable accumulation of p-CREB granules in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. This indicated the hindrance of pro-survival gene transcription, which is mediated by PKA, compared to age-matched controls (Chalovich et al. 2006). Other PD cellular models like 6-hydroxy dopamine (6-OHDA)-treated B65 and SH-SY5Y cells have also shown CREB dysregulation (Chalovich et al. 2006). Moreover, stable PINK1 knockdown cells have highlighted a link between decreased total PKA activity and nuclear p-CREB (Dagda et al. 2014). In another study, the expression of human uncoupling protein 2 (hUCP2), a mitochondrial membrane transport protein, rescued dopamine neurons against rotenone (ROT)-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and cytotoxicity by elevating intracellular cAMP levels in adult flies. Furthermore, PKA inhibitor therapy reduced the hUCP2 expressing DA neurons’ mitochondrial integrity, mobility, and cell survival exposed to ROT (Hwang et al. 2014). In addition, PDE4 inhibition by rolipram increases activated CREB levels in striatal spiny neurons in Huntington’s disease (HD) rat models (DeMarch et al. 2007). Hence, the above findings highlight the potential role of PDE4 inhibitors in upregulating CREB phosphorylation via the cAMP/PKA-mediated pathway and may be repositioned in PD (Fig. 4) (the proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

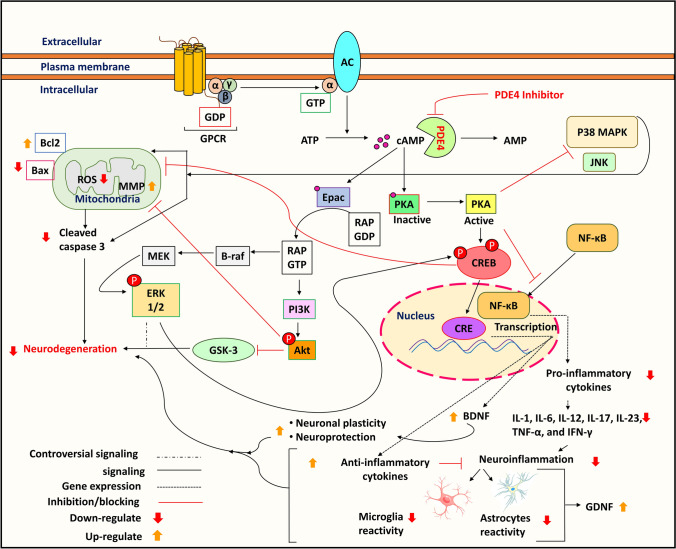

Fig. 4.

Signaling cascades (illustration of cAMP/CREB/BDNF, MAPKs, Epac/Akt, and NF-κB) involving PDE4 isoenzyme in PD and the potential of PDE4 inhibitors. AC: Adenyl cyclase, Akt: Protein kinase B, AMP: Adenosine monophosphate, ATP: Adenosine triphosphate, Bax: Bcl2 associated X, Bcl2: B-cell lymphoma 2, BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, B-raf: Serine/threonine-protein kinase B-raf, cAMP: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, CRE: cAMP response element, CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein, Epac: Exchange factor directly activated by cAMP, ERK 1/2: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, GDNF: Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, GDP: Guanosine diphosphate, GPCR: G protein-coupled receptor, GSK-3: Glycogen synthase kinase 3, GTP: Guanosine triphosphate, IL: Interleukins, IFN-γ: Interferon gamma, JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase, MEK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, MMP: Mitochondrial membrane potential, NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, P38MAPK: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, PDE4: Phosphodiesterase-4, PKA: Protein kinase A, PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Rap: Member of the Ras superfamily of GTP-binding protein, ROS: Reactive oxygen species

MAPK Signaling

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) regulate several physiological processes and, including gene expression, metabolism, mitosis, cellular proliferation and mobility, stress response, survival, and apoptosis. Stress, growth factors, cytokines, mitogens, infections, and toxins activate MAPK pathways, including MAPKKK and MAPKK, resulting in the phosphorylation of downstream effectors such as c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), p38MAPKs, and ERK1/2 (Zhang and Liu 2002). In addition, JNK (Brecht et al. 2005; Crocker et al. 2011) p38MAPK (Choi et al. 2004; Tong et al. 2018) activation promotes oxidative stress and apoptosis, leading to microglial activation and chronic inflammation in the brain cells, which contributes to PD development.

The MAPK/ERK pathway plays an important role in memory and synaptic plasticity. ERK activation increases long-term potentiation (Peng et al. 2010). Various studies have reported that ERK1/2 can phosphorylate CREB, promoting neuroprotection via BDNF transcription in PD (Luo et al. 2018; Bilge et al. 2020). However, strong indications from several studies provide conflicting insights. These studies have reported that ERK1/2 also contributes to brain cell death by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STATs), which leads to the activation of p53, pro-inflammatory markers, and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (Zhu et al. 2003; Li 2021). ERK1/2 and JNKs have also been reported to cause neurodegeneration in PD by activating the mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling (Bohush et al. 2018). Furthermore, in the oligodendroglial CG4 cell line, the function of ERK1/2 in neurodegeneration was demonstrated using PD98059 (an ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor), which inhibits hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced cell death (Bhat and Zhang 1999).

Another MAPK family member that is majorly implicated in PD is P38MAPK. In a previous study, the overexpression of α-synuclein A53T activated p38MAPK in SN4741 cells. Subsequently, p38MAPK activation caused direct phosphorylation of parkin at serine 131, disrupting the protective role of parkin (Chen et al. 2018a). In another α-synuclein A53T model, p38MAPK suppression or induction of a kinase death variant of p38MAPK decreased dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1)-mediated mitochondrial fission, which leads to the restoration of mitochondrial dysfunction (Gui et al. 2020). The cAMP/PKA cascade interacts with MAPK/ERK signaling (Qiu et al. 2000; Dumaz and Marais 2005), which is crucial for synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus cornu ammonis-1 (CA1) region. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) inhibits PDE4 by activating ERK and increasing cAMP levels (Hoffmann et al. 1999). However, cAMP can inhibit or activate MAPK signaling depending on the cell type (Qiu et al. 2000), and their interaction can be cell stage-specific (Vogt Weisenhorn et al. 2001). Hence, the regulation of cAMP by PDE4 depicts a common link in regulating MAPK signaling in an indirect manner, which is also evident in PD (Fig. 4) (Zhong et al. 2022) (the proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

Epac/Akt Signaling

Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor is directly activated by cAMP (Epac). Epac activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent and Akt (protein kinase B) (De Rooij et al. 1998). It has been observed that Akt and phosphorylated Akt (P-Akt) levels are considerably lower in the SNpc of PD patients (Luo et al. 2019). Several in vitro and indirect in vivo studies have revealed that Akt activation and the subsequent inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) stimulates the dopamine receptor (Brami-Cherrier et al. 2002; Svenningsson et al. 2003; Rau et al. 2011). In the 6-OHDA-induced PD mice model, reduced PI3K/Akt levels have been studied (Yan et al. 2019). Furthermore, disruption of the PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a pathway causes oxidative stress in PD (Gong et al. 2018). Moreover, during the pathogenesis of PD, GSK-3 activation upregulates caspase-3 in the dopaminergic nerve., culminating in dopaminergic neuronal death (Hernandez-Baltazar et al. 2013). Interestingly, activation of Akt-phosphorylated Ser21 of GSK-3α or Ser9 of GSK-3β inhibits GSK-3 activity (Yang et al. 2018). PDE4 inhibition by rolipram modulates Epac activity, which promotes neurite outgrowth and myelination in spinal cord injury (SCI) in vitro model assessed by immunohistochemistry (Boomkamp et al. 2014). In addition, PDE4 inhibition by roflumilast attenuates nitric oxide (NO)-induced cell death by activating the cAMP/PKA and Epac/Akt pathways (Kwak et al. 2008). This suggests that the co-expression of PDE4 mediates the regulation of the Epac/Akt signaling cascade and might aid in the neuroprotection and treatment of PD (Fig. 4) (the proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

NF-κB Signaling

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) represents a family of inducible transcription factors that are well known for their roles in inflammatory responses along with controlling cell division and death. This family comprises five members which are structurally related, including NF-κB1/p50, NF-κB2/p52, RelA/p65, RelB, and c-Rel, which mediates target gene transcription by binding to a specific DNA element, the κB enhancer, as various heterodimers or homodimers (Sun et al. 2013). Dysregulation of the NF-κB pathway has been implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases (Mattson and Camandola 2001). Post-mortem investigations have revealed that the brains of PD patients have increased RelA nuclear translocation in substantia nigra melanized neurons, which supports NF-κB activation in PD (Hunot et al. 1997). In addition, an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) performed on the substantia nigra of an MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) mouse model showed activated NF-κB (Ghosh et al. 2007). Microglia internalize α-synuclein aggregates and induce nuclear RelA accumulation (Cao et al. 2010, 2012). Another NF-κB-associated c-Rel gene was found to increase significantly in the substantia nigra and striatum of mice subjected to MPTP induction (Wang et al. 2020). These findings suggest that NF-κB is upregulated during the pathogenesis of PD, which promotes neuroinflammation. Blocking NF-κB signaling in the rat MPTP model drastically decreased histone 3 acetylation in the α-synuclein promoter region, blunting α-synuclein in the substantia nigra and enabling motor deficit recovery (Liu et al. 2014). The crosstalk between cAMP and NF-κB is well known, and cAMP has been reported to modulate NF-κB transcription (Shirakawa et al. 1989; Bomsztyk et al. 1990). However, several studies have reported that elevation of cAMP levels by PDE4 inhibition negatively affects NF-κB transcription. For instance, PDE4 inhibition by rolipram reduces TNF-α production and inhibits the activation of three NF-κB complexes in LPS-induced human chorionic cells (Hervé et al. 2008).

Moreover, as discussed in the previous section, several PDE4 inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, and are known to alleviate pro-inflammatory cytokines by upregulating cAMP and blocking NF-κB transcription (Young and Roebuck 2016; Paton 2017; Rhee and Kim 2020). In addition, roflumilast was reported to significantly decrease the elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in neuroinflammation, such as TNF-α and NF-κB transcription, which were attenuated in a quinolinic acid-induced HD rat model, as assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (Saroj et al. 2021). Taken together, PDE4 inhibition may attenuate neuroinflammation in PD by downregulating NF-κB transcription (Fig. 4) (The proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

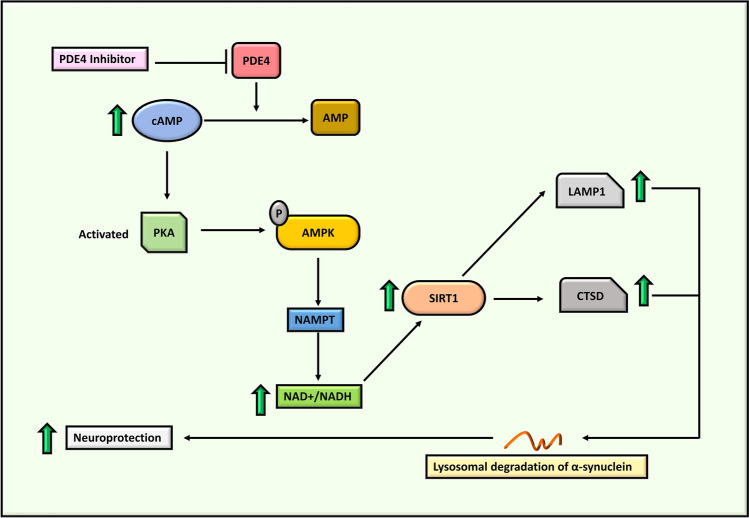

cAMP/AMPK/SIRT1 Signaling

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), also known as the fuel-sensing enzyme, is activated via cAMP-dependent pathways (Yin et al. 2003; Omar et al. 2009; Chung 2012). AMPK activation subsequently promotes the transcription of niacinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which activates Sirtuin1 (SIRT1) (Cantó et al. 2010). However, SIRT1 expression was significantly decreased in ROT-, MPP+-, and kainite (KA)-treated primary neurons in mice (Pallàs et al. 2008), which occurs as a result of low levels of AMPK in PD. An AMPK inhibitor (compound C) was reported to increase MPP+-induced cell death (Choi et al. 2010). Furthermore, the study showed that overexpression of AMPK increased cell viability after exposure to MPP+ in SH-SY5Y cells. In addition, Drosophila models are AMPK-deficient; thus, parkinsonian-like characteristics, including dopaminergic neuronal loss and climbing difficulties that worsen with age, have been observed (Hang et al. 2021).

SIRT1 is positively correlated with cathepsin D (CTSD) and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) (Zhong et al. 2016; Dong et al. 2021a). CTSD is a lysosomal enzyme linked to the lysosomal recycling and degradation of various substrates, including α-synuclein (Sevlever et al. 2008). Immunoblot analysis conducted in post-mortem nigral tissues of patients with PD reported significantly lower LAMP1 protein levels compared to age-matched control participants (Dehay et al. 2010). In a recent study, overexpression of SIRT1 protected diquat- and ROT-induced SH-SY5Y cells by downregulating the transcription of NF-κB and poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (cPARP-1), resulting in the reduction of phospho-α-synuclein aggregates (Singh et al. 2017). Thus, SIRT1 downregulation is involved in neuroinflammation during the progression of PD. Interestingly, rolipram activates the cAMP/AMPK/SIRT1 pathway and imparts neuroprotection in the pathology of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (Dong et al. 2021b). This suggests the potency of PDE4 inhibition in upregulating AMPK and SIRT1, which may help slow disease progression in PD (Fig. 5) (the proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

Fig. 5.

Illustration of cAMP/AMPK/SIRT1 pathway and the potential of PDE4 inhibition in α-synuclein degradation. AMP: Adenosine monophosphate, AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase, cAMP: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, CTSD: Cathepsin D, LAMP1: Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1, NADH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen, NAMPT: Niacinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, PDE4: Phosphodiesterase-4, PKA: Protein kinase A, SIRT1: Sirtuin1

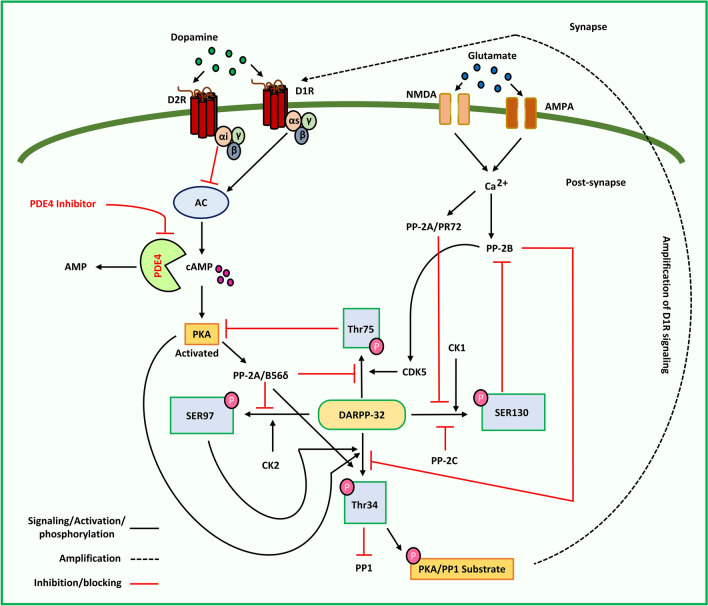

DARPP-32 Signaling

DARPP-32 (Dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 32 kDa) are found in striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) (Ouimet and Greengard 1990; Ivkovic and Ehrlich 1999; Tang and Bezprozvaany 2004; Yger and Girault 2011) and are also called phosphoprotein phosphatase-1 regulatory subunit 1B (PPP1R1B). Upon phosphorylation, DARPP-32 inhibits protein phosphatase-1 (PP-1) at Thr34 via PKA, thus playing a critical role in dopamine signaling (Hemmings et al. 1984). Phosphorylation at Thr34 influences dopamine transmission in both dopamine-1 receptor (D1R)-expressing striatonigral MSNs (direct) and D2R-expressing striatopallidal MSNs (indirect) (Bateup et al. 2008). This further results in enhanced phosphorylation of PKA/PP1 substrates and increases D1R signaling. cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5), casein kinase (CK2), and CK1 also phosphorylate DARPP-32 at Thr75, Ser97, and Ser130, respectively (Girault et al. 1989; Desdouits et al. 1995a; Bibb et al. 1999). Phosphorylation at Thr75 by Cdk5 is reported to inhibit PKA activity, and inhibits the phosphorylation of DARPP-32 at Thr34, resulting in decreased activation of D1R (Bibb et al. 1999). However, the dephosphorylation of P-Thr75 DARPP-32 by PP2A/B56δ through the activation of D1 receptor/PKA signaling has been reported to eliminate the inhibition of PKA by P-Thr75 DARPP-32 (Stipanovich et al. 2008). CK2 phosphorylation of DARPP-32 at Ser97 promotes PKA-mediated phosphorylation of DARPP-32 at Thr34 (Girault et al. 1989). Furthermore, because Ser97 is proximal to DARPP-32's nuclear export signal, DARPP-32 localization in the nucleus is regulated by P-Ser97 DARPP-32. Activation of D1R/PKA signaling causes PKA-activated PP2A/B56 to dephosphorylate P-Ser97 DARPP-32, which leads to the nuclear accumulation of P-Thr34 DARPP-32, inhibition of nuclear PP1, histone-3 phosphorylation, and enhanced gene expression (Stipanovich et al. 2008). CK1 phosphorylation of Ser130 inhibits calcineurin (PP2B) dephosphorylation of Thr34 (Desdouits et al. 1995b). Protein phosphatase activity significantly affects DARPP-32 phosphorylation (Yamada et al. 2016). PP-2B, activated by glutamate-stimulated Ca2+ signaling, dephosphorylates P-Thr34 DARPP-32 and inhibits D1 receptor/PKA/DARPP-32 signaling (Nishi et al. 1997). PP2A/B56δ (PKA-sensitive) dephosphorylates P-Thr75 DARPP-32 and PP2A/PR72 (CA2+-sensitive), which in turn dephosphorylate P-Ser97 DARPP-32 (Girault et al. 1989; Nishi et al. 2000; Ahn et al. 2007). The phosphatases PP2A/PR72 and PP2C dephosphorylate P-Ser130 DARPP-32 (Desdouits et al. 1995b; Yamada et al. 2016).

The phosphorylation state of DARPP-32 has been implicated in PD, along with hypofunctioning of D1R signaling. Lesioning with 6-OHDA does not significantly affect P-Thr34 DARPP-32 or total DARPP-32 levels but raises P-Thr75 DARPP-32 levels (Brown et al. 2005). The use of arsenic-containing pesticides is associated with an increased prevalence of PD and is known to induce α-synuclein accumulation (Cholanians et al. 2016). Both in vitro (Li et al. 2012) and in vivo (Srivastava et al. 2018) arsenic exposure resulted in a considerable increase in the expression of CDK5, which phosphorylates DARPP-32 at Thr75. In neostriatal sections of mice, rolipram administration did not cause D1 receptor/PKA-mediated phosphorylation of DARPP-32; however, increased adenosine A2a receptor-mediated phosphorylation of DARPP-32 has been reported (Bateup et al. 2008). Increased adenosine A2a receptor-mediated signaling is expected to counter the actions of the dopamine D2 receptor in striatopallidal neurons, implying that PDE4 is wholly expressed in the neurons of the indirect pathway. However, immunohistochemical investigation of these neostriatal slices indicated that PDE4B was present in both pathways, with higher expression levels in the neurons in the indirect pathway. Concerning dopaminergic signaling in the striatum, PDE4 inhibition of cAMP/PKA signaling is linked to adenosine A2a receptor signaling and has no significant impact on striatal dopamine signaling. Dopaminergic tone has been shown to increase upon PDE4 inhibition in striatal neurons by enhancing both synthesis and metabolism; however, it does not directly affect release. The functioning of the basal ganglia depends on specific levels of dopamine for optimal functioning. Movement difficulties are caused by low dopamine levels, whereas high dopamine levels induce involuntary movement. However, although PDE4 inhibition is not directly implicated in the release of dopamine, increased generation of the dopamine precursor levodopa in elevated cAMP-mediated tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene transcription may result in higher stimulus-driven dopamine release, which is known as levodopa-induced dyskinesia. (Heckman et al. 2016). PDE4Is may constitute an exciting treatment strategy for neurological disorders involving hypofunctioning striatal dopamine transmission systems such as PD. Interestingly, treatment with roflumilast restored the premature responding in 6-OHDA lesioned animals to the level observed in sham-lesioned animals, suggesting that PDE4 inhibition can reverse motor impulsivity induced by hypodopaminergia (Heckman et al. 2018). Moreover, Nishi et al. suggested that we may achieve a phosphorylation state with a right shift by altering intracellular dopamine/DARPP-32 signaling via PDE inhibition, which upregulates cAMP/PKA signaling (Nishi and Shuto 2017). DARPP-32-expressing neurons have been reported in the mouse frontal cortex with significant PDE4B levels (Nishi and Snyder 2010). It is well known that the dysfunction of dopamine signaling in the frontal cortex is associated with PD (Taylor et al. 1986). Therefore, the co-expression of PDE4B with DARPP-32 plays an indirect role in dopamine receptor signaling, which may be a possible target in PD (Fig. 6) (the proposed strategy is discussed further in the next section).

Fig. 6.

Illustration of signaling cascades involving PDE4 in DARPP-32 phosphorylation and the potential of PDE4 inhibitors. AC: Adenyl cyclase, AMP: Adenosine monophosphate, AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor, cAMP: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, CDK5: Cyclin-dependent kinase 5, CK1 and 2: Casein Kinase 1 and 2, D1R and D2R: Dopamine receptor 1 and 2, DARPP-32: Dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 32 kDa, NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, PDE4: Phosphodiesterase-4, PKA: Protein kinase A, PP1/2A/2C: Protein phosphatase-1/2A/2C, SER97/130: Serine 97/130, Thr34/75: Threonine 34/75

cAMP/UPS Signaling

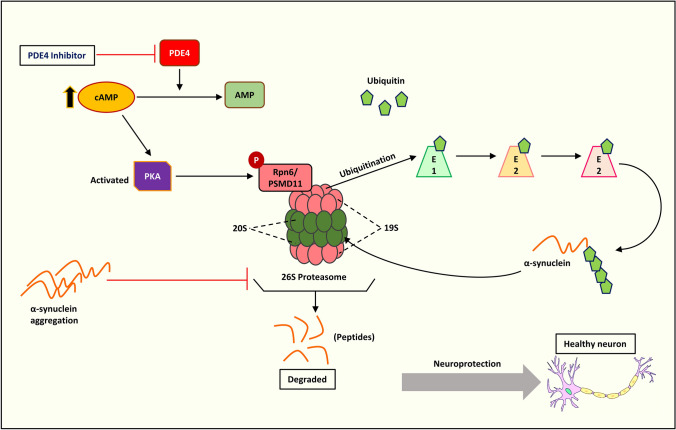

In eukaryotes, the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is an essential protein degradation mechanism that regulates several processes including signal transmission, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cellular differentiation (Hershko and Ciechanover 1998). The UPS machinery also degrades misfolded and damaged proteins, implicating its use in multiple diseases such as neurodegeneration, cancer, inflammation, and autoimmune disorders (Schwartz and Ciechanover 1999). The UPS functions via ubiquitination of proteins involving several enzymes, notably E1 ligase (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 ligase (conjugating enzyme), and E3 ligase (ubiquitin ligase). Ubiquitylated proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome, which is the central proteolytic machinery (Roos-Mattjus and Sistonen 2004). The incidence of impaired UPS has been reported in various neurodegenerative diseases such as AD (Oddo 2008), PD (Lim 2007), and HD (Bennett et al. 2007). Studies in the human post-mortem brain have shown that a fraction of α-synuclein accumulates in Lewy bodies in a ubiquitinated form, implying a role for ubiquitin ligases in α-synuclein turnover and clearance (Tofaris et al. 2003; Anderson et al. 2006). Several in vitro studies have indicated a reduction in proteasomal activity following exposure to pesticides and environmental chemicals (such as ROT, paraquat, and maneb) that produce PD-like conditions. These findings bolster the link between UPS dysfunction and sporadic PD (Wang et al. 2005, 2006; Betarbet et al. 2006). Additionally, in an in vivo MPTP-induced mouse model, osmotic minipumps were used to continuously infuse MPTP neurotoxins into mice for a month, resulting in a Parkinsonian-like phenotype, including striatal dopamine depletion and loss of neurons in both the SN and locus coeruleus, further forming α-synuclein aggregates and ubiquitin-positive inclusions (Fornai et al. 2005). Intriguingly, chronic administration of ROT in vivo manifests as oxidative modification of DJ-1, α-synuclein aggregation, and proteasomal dysfunction (Betarbet et al. 2006). Studies have demonstrated that protein kinases phosphorylate proteasome subunits (VerPlank and Goldberg 2017), particularly PKA, which promotes proteasome activity in mammalian cells (Lokireddy et al. 2015; Myeku et al. 2016). PKA activation by increasing cAMP promotes phosphorylation of the Rpn6/PSMD11 subunit of the 19S regulatory complex (Lokireddy et al. 2015). In addition, canthin-6-one (an indole alkaloid) promotes both wild-type and mutant α-synuclein degradation in a ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS)-dependent manner (Yuan et al. 2019). Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome-wide screening technology, RPN2/PSMD1, the 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1, was identified as the target gene of canthin-6-one, which enhances UPS by activating PKA. In a recent study using a natural alkaloid, harmine was found to promote α-synuclein degradation via PKA-UPS activation, both in vitro and in vivo (Cai et al. 2019). In particular, PDE4 inhibition by rolipram activates PKA-UPS and clears tau aggregation in Ub-G76V-GFP mice (Myeku et al. 2016). PDE4 inhibition also degrades α-synuclein via proteasomal degradation by activating PKA, as reported in a recent study (Chen et al. 2022) (details of this study are discussed further in the next section). PDE4 inhibition may emerge as a potential strategy to activate PKA-UPS and possibly treat PD (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Illustration of activation of PKA/UPS and α-synuclein degradation by PDE4 inhibition. AMP: Adenosine monophosphate, cAMP: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, E1/2/3: Ubiquitin-activating enzyme/ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme/ubiquitin ligase, PDE4: Phosphodiesterase-4, PKA: Protein kinase A, Rpn6/PSMD11: 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11, 19S: regulatory unit of 26S proteasome, 20S: The catalytic core of 26S proteasome

PDE4 Inhibition as a Potential Strategy in PD

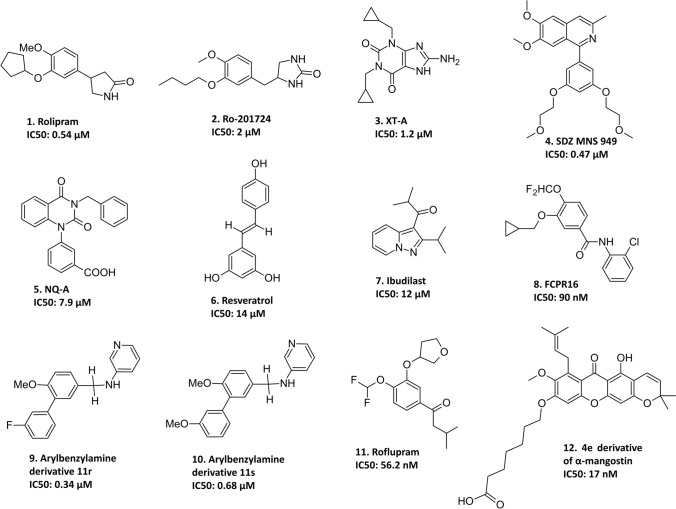

Reduced levels of the second messenger cAMP, numerous interrelated signaling cascades, and co-expression of cAMP-specific PDE4 have been associated with PD pathogenesis. Thus, PDE4 inhibition appears to be a promising therapeutic strategy for PD. Recently, in pursuit of promising neuroprotective and disease-modifying targets, PDE4 and the potential of several PDE4Is have been preclinically investigated in PD, with rolipram being the only drug to undergo a clinical trial (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

The chemical structures of PDE4 inhibitors investigated in PD. Rolipram is 4-(3-cyclopentyloxy-4-methoxyphenyl)pyrrolidin-2-one, Ro-201724 is 4-[(3-butoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)methyl]imidazolidin-2-one, XT-A is 1,3-dicyclopropylmethyl-8-aminoxanthine, SDZ MNS 949 is 1-[3,5-bis(2-methoxyethoxy)phenyl]-6,7-dimethoxy-3-methylisoquinoline, NQ-A is 1-(3-carbomethoxyphenyl)-3-benzyl-quinazoline-2,4-dione, resveratrol is 5-[(E)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]benzene-1,3-diol, ibudilast is 2-methyl-1-(2-propan-2-ylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-3-yl)propan-1-one, FCPR16 is N-(2-Chlorophenyl)-3-(cyclopropylmethoxy)-4-(difluoromethoxy)benzamide, arylbenzylamine derivative 11r is N-(Pyridin-3-yl)-3-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-methoxybenzylamine, arylbenzylamine derivative 11 s is N-(Pyridin-3-yl)-3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-4-methoxybenzylamine, roflupram is 1-[4-(difluoromethoxy)-3-(oxolan-3-yloxy)phenyl]-3-methylbutan-1-one, and 4e derivative of α-mangostin is 7-((5-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-7-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-6-oxo-2H,6H-pyrano[3,2-b]xanthen-9-yl)oxy)heptanoic Acid

Here, the different signaling pathways implicated in PD, as discussed in the previous section, and their successful/evident modulation and regulation by PDE4 inhibitors mediating cAMP levels to effectively treat PD have been summarized thoroughly by extensive analysis of all preclinical studies. For example, FCPR16, a PDE4 inhibitor, inhibits dopaminergic degeneration in human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) by restricting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and preventing alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). This effect is mediated by the cAMP/PKA/CREB and Epac/Akt signaling pathways, as evidenced by western blotting (Zhong et al. 2018). This study supports the role of PDE4 inhibition by FCPR16 in the attenuation of oxidative stress in a cellular model of PD. In another study, FCPR16 protected SH-SY5Y neuronal cells from MPP+-induced oxidative damage by activating AMPK autophagy and had no emetic side effects compared with other PDE4 inhibitors (Zhong et al. 2019). Treatment with FCPR16 increased the expression of LC3-II (a biomarker of autophagy) and decreased the level of p62 (a substrate of autophagy). The dysfunction of LRRK2 is majorly involved in PD and has been shown to influence PKA activity by affecting the activity of PDE4 in microglia, regulating cAMP degradation, and cAMP-dependent signaling (Russo et al. 2018).

PDE4B, the most highly expressed PDE4 in microglial cells, is a promising therapeutic target for neuroinflammation in PD. LRRK2 regulates microglial activation and plays a critical role in these cells (Russo et al. 2014). Microglia play crucial roles in the response to inflammatory stimuli. Although a well-regulated inflammatory response is essential for tissue repair and brain homeostasis, excessive and prolonged neuroinflammation can lead to the generation of toxic molecules, resulting in severe cellular damage, as observed in several neurodegenerative diseases including PD (Tansey and Goldberg 2010). In another study of LRRK2, PDE4 inhibition affected the phosphorylation of PKA-mediated NF-κB p50. Furthermore, treatment with a combination of PDE4 and LRRK2 inhibitors resulted in a similar increase in NF-κB p50 phosphorylation compared to that in cells treated with PDE4 inhibition alone, suggesting that the inhibition of LRRK2 increases cAMP levels by inhibiting PDE4 activity (Russo 2019). Therefore, PDE4 inhibition may attenuate neuroinflammation in PD patients.

PDE4 inhibitors have been proven to prevent motor deficits in the Batten disease mouse model, a lysosomal storage syndrome characterized by Parkinsonism (Aldrich et al. 2016). The prototype PDE4 inhibitor (rolipram) has been reported to increase dopamine levels and cause TH phosphorylation by promoting striatal dopamine synthesis without affecting dopamine release (Bateup et al. 2008). This effect was regulated by increased DARPP-32 Thr34 phosphorylation in striatopallidal neurons via activation of adenosine A2A receptor signaling in the striatum, which was found to be cAMP/PKA signaling mediated under normal conditions, concerning PD, PDE4 inhibition in MPP+-induced rat mesencephalic dopaminergic cultured cells elevated the forskolin-treated increase in dopamine uptake (Hulley et al. 1995b). In addition, in an MPTP-induced C57BL/6 mouse model, rolipram reduced dopamine depletion (Hulley et al. 1995a) and enhanced dopamine levels in the striatum by blocking metabolism and TH loss (Yang et al. 2008). Chronic ibudilast (IBD), a non-selective PDE4 inhibitor, reduces the reactivity of astroglial cells, enhances the synthesis of striatal glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and significantly reduces the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 in an MPTP model (Schwenkgrub et al. 2017). In a H2O2 reperfusion rat model, IBD exhibited a protective role in astrocytes by reducing the release of cytochrome c, causing caspase-3 activation and nuclear condensation via the cGMP pathway (Takuma et al. 2001).

Recently, arylbenzylamines were designed as potent PDE4 inhibitors. Preliminary screening revealed that arylbenzylamine derivatives bearing a pyridin-3-amine side chain exhibited inhibitory activity against the human PDE4B1 and PDE4D7 isoforms (Tang et al. 2019). Molecular docking results revealed possible interactions of arylbenzylamine derivatives 11r and 11 s with the UCR2 of PDE4B1, which may explain the partial inhibition of PDE4. Moreover, using a cell-based PD model, compounds 11r and 11 s were found to protected SH-SY5Y cells from MPP+-induced apoptosis. The neuroprotective effects of 11r and 11 s were greater than that of rolipram. A recently developed PDE4 inhibitor, roflupram, prevented MPP + /MPTP-induced dopaminergic degeneration, mitigated motor impairment, elevated TH expression, and recovered mitochondrial function via the CREB/PGC1 pathway (Zhong et al. 2020). PDE4 inhibition by roflupram also attenuated α-synucleinA53T-induced cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells via the PKA/p38MAPK/Parkin pathway (Zhong et al. 2022). Roflupram significantly inhibited the phosphorylation and interaction of p38MAPK and Parkin, while increasing the mitochondrial translocation of Parkin. However, this study reported that PDE4B knockdown reduced cellular apoptosis, but its overexpression decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and increased cellular apoptosis, which attenuated the protective role of roflupram. These results suggested that PDE4B overexpression enhanced α-synuclein-induced cytotoxicity and promoted neurodegeneration in PD. In another recent study, roflupram facilitated α-synuclein degradation in ROT-induced PD models both in vitro and in vivo. Roflupram significantly improved motor impairments, which were attributed to the increased expression of TH, SIRT1, mature CTSD, and LAMP1 as well as a decrease in α-synuclein in the SNpc. The neuroprotective mechanism of roflupram has been linked to NAD+/SIRT1-dependent activation of lysosomal activity (Dong et al. 2021a). Another compound, resveratrol, a polyphenol found in red wine, inhibits PDE4 more than the other PDEs (Park et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2016). This polyphenol showed protective effects against ROT-induced SH-SY5Y cell apoptosis and increased the degradation of aggregated α-synuclein in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell lines through activation of the AMPK/SIRT1/autophagy pathway (Wu et al. 2011). The PDE4 inhibitor 4e derivative of α-mangostin (phytoconstituent) promoted UPS activity, which was evident by the accelerated degradation of the UPS substrates Ub-G76V-GFP and Ub-R-GFP, as well as increased proteasomal enzyme activity (Chen et al. 2022). Treatment with this derivative reduced α-synuclein accumulation in the transgenic A53T mouse model, as validated by western blotting and immunohistochemistry. Additionally, in PC12 cells, 4e markedly enhanced the breakdown of inducibly expressed wild-type (WT) and mutant α-synuclein in a UPS-dependent manner. Furthermore, in primary neurons and mutant A53T mouse brains, 4e activates PKA, restores UPS dysfunction, and alleviates α-synuclein aggregation (Chen et al. 2022).

In most studies, inhibition of PDE4 ameliorated motor dysfunction and reversed Parkinsonism. However, in a double-blind clinical experiment in 1983, rolipram therapy failed to improve Parkinsonism in humans (Casacchia et al. 1983). This experiment was the first study of PDE4 inhibition in PD; however, it no longer has commercial value, as rolipram is a clinically failed drug owing to its adverse effects. Cognitive impairment has been reported to occur frequently in patients with PD (Watson and Leverenz 2010). In a previous study, the dentate gyrus (DG) of an MPTP mouse model showed decreased levels of cAMP, phosphorylated CREB, and cAMP/CREB signaling in the hippocampus. Rolipram therapy restores memory impairment while increasing cAMP and phosphorylated CREB levels, indicating that reduced cAMP/CREB signaling in the DG causes cognitive impairment in MPTP-induced mice (Kinoshita et al. 2017). A few clinical studies have provided substantial evidence that PDE4 is involved in the various pathological conditions of PD. For instance, recent positron emission tomography (PET) investigations employing [11C]rolipram have revealed loss of PDE4 expression in numerous brain locations, including the striato-thalamo-cortical circuit, in patients with PD. However, this study showed no association between PDE4 loss and the existence and severity of motor impairment, although working memory problems were affected (Niccolini et al. 2017). Intriguingly, another clinical investigation using [11C]rolipram PET and multimodal MRI scans found that the existence and severity of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in PD correlated with higher PDE4 expression (Wilson et al. 2020). It is important to note that these studies included patients with idiopathic PD without mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Additionally, the sample size of this study was very small. From another point of view, the enantiomer of the rolipram labeled with emitter [11C] was not specified. It has been shown that R(−)-rolipram exhibits a higher affinity for PDE4 than S( +)-rolipram (Parker et al. 2005). Furthermore, in one study, the regional brain uptake of R-[11C]rolipram was higher than that of R/S-[11C]rolipram, whereas S-[11C]rolipram retention rapidly subsided to levels below the blood level (Lourenco et al. 2001).

Altogether, PDE4 inhibition can result in a turnover of α-synuclein accumulation, TH and dopamine depletion, and the related pathophysiological causes of PD. Therefore, PDE4 inhibition may be a promising therapeutic strategy for PD. The preclinical investigations of PDE4 and PDE4Is in PD are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Preclinical investigations involving PDE4 and PDE4 inhibitors in PD

| Drug/molecule under investigation | Model | Results | Conclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ro-201724, SDZ-MNS949 XT-A, NQ-A (PDE4 inhibitors) | MPP+-induced rat mesencephalic dopaminergic cell culture | Survival of Dopaminergic neurons (assayed by counting TH-positive neurons stained with a mouse anti-TH antibody) | PDE4 inhibition via cAMP modulation protects cells from MPP+ toxicity | (Hulley et al. 1995b) |

| Ro-201724, SDZ-MNS949 XT-A, NQ-A (PDE4 inhibitors) | MPP+-induced rat mesencephalic dopaminergic cell culture and MPTP-treated C57BL/6 mice | Survival of dopaminergic neurons in the cell culture (determined by counting TH-positive neurons). SNc neurons of mice were more in number upon PDE4 inhibition (determined by TH immunocytochemistry and Nissl staining) | PDE4 inhibition protects cells from MPP+ toxicity | (Hulley et al. 1995a) |

| Rolipram (PDE4 inhibitor) | MPTP mouse model | Effectively reduced striatal dopamine depletion and TH-positive neuronal death in the substantia nigra of the mice | Inhibition of PDE4 may have therapeutic implications in PD | (Yang et al. 2008) |

| Resveratrol (non-selective PDE4 inhibitor) | ROT-treated SH-SY5Y and α-synuclein-expressing PC12 cells | Showed neuroprotection by up-regulating the AMPK/SIRT1/autophagy pathway | Activating AMPK or SIRT1 might be a potential neuroprotective approach for PD | (Wu et al. 2011) |

| Ibudilast (non-selective PDE4 inhibitor) | MPTP mouse model | Attenuated neuroinflammation by reducing the reactivity of astroglial cells and increasing the production of striatal GDNF | PDE inhibition could have an anti-inflammatory effect on PD | (Schwenkgrub et al. 2017) |

| Rolipram (PDE4 inhibitor) | MPTP mouse model | Improved memory deficits and restored cAMP and phosphorylated CREB levels | PDE4 inhibition could attenuate memory extinction in PD | (Kinoshita et al. 2017) |

| LRRK2 and PDE4 | LRRK2 G2019S knock-out mice model and transfected microglial cells | Altered PDE4 activity and modified the cAMP content | PDE4 would be a probable LRRK2 effector in microglia; the LRRK2 G2019S mutation may promote microglia activation, which might make a significant contribution to the pathophysiology of LRRK2-related PD | (Russo et al. 2018) |

| FCPR16 (PDE4 inhibitor) | MPP+-treated primary cultured dopaminergic neurons (SH-SY5Y) | Induced autophagy by inhibiting ROS formation and increased ΔΨm. Increased the Bcl2/Bax ratio in MPP+-treated cells | Inhibition of PDE4 may have therapeutic implications in PD | (Zhong et al. 2018) |

| Arylbenzylamine derivatives 11r and 11 s (PDE4 inhibitors) | MPP + -treated primary cultured dopaminergic neurons (SH-SY5Y) | 11r and 11 s protected MPP+-induced toxicity confirmed by MTT assay and PI staining | PDE4 inhibition protects MPP+-induced toxicity | (Tang et al. 2019) |

| FCPR16 (PDE4 inhibitor) | MPP+-treated primary cultured dopaminergic neurons (SH-SY5Y) | Activated AMPK, which enhanced the production of autophagosome as well as lysosome biogenesis | Inhibition of PDE4 may have therapeutic implications in PD | (Zhong et al. 2019) |

| LRRK2 and PDE4 | LRRK2 G2019S knock-in mice model | PDE4 inhibition affected NF-κB p50 phosphorylation mediated by PKA. Combined PDE4 and LRRK2 inhibitors also affected NF-κB p50 phosphorylation | LRRK2 kinase inhibition increases cAMP levels by inhibiting PDE4 activity, and PDE4 inhibition alone can alleviate neuroinflammatory NF-κB p50 phosphorylation in PD | (Russo 2019) |

| Roflupram (PDE4 inhibitor) | SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+ | Reduced phosphorylated CREB and PGC-1 in the substantia nigra and striatum, as well as dopaminergic neuronal loss. Improved motor dysfunctions, increased TH expression, and restored mitochondrial function | Inhibition of PDE4 may have therapeutic implications in PD | (Zhong et al. 2020) |

| Roflupram (PDE4 inhibitor) | ROT-treated SH-SY5Y cells and mice model | Massively improved motor impairments, imparted by increased expression of TH, SIRT1, mature CTSD, and LAMP1, as well as decreased α-synuclein in the SNpc | PDE4 inhibition could activate lysosomal function and reduce α-synuclein toxicity in PD | (Dong et al. 2021a) |

| Roflupram (PDE4 inhibitor) | Mutant human A53T α-synuclein overexpressed SH-SY5Y cells | Attenuated α-synuclein-induced cytotoxicity in the α-synucleinA53T model by PKA/p38MAPK/Parkin pathway. Inhibited the phosphorylation and interaction of p38MAPK and Parkin while increasing Parkin's mitochondrial translocation | PDE4 inhibition could attenuate α-synuclein toxicity in PD | (Zhong et al. 2022) |

| α‑mangostin derivative 4e (PDE4 inhibitor) | WT, mutant α-synuclein expressing PC12 cells, and transgenic A53T mice | Effectively stimulated the cAMP/PKA pathway and promoted UPS activity in neuronal cells. Degraded WT and mutant α-synuclein in PC12 cells. PKA activation was consistent in primary neurons in the A53T mouse brain | PDE4 inhibition activates UPS and degrades α-synuclein in PD | (Chen et al. 2022) |

Challenges and Strategies to Overcome

Owing to the sheer anti-inflammatory benefits found upon inhibition in vitro and in vivo studies, PDE4 isoforms have garnered significant attention (Banner and Trevethick 2004). Mechanism-associated adverse effects at efficacious concentrations, such as nausea and emesis, have limited the widespread use of first-generation PDE4 inhibitors, such as rolipram. Other adverse effects of repeated administration of PDE4 inhibitors include headache, diarrhea, fatigue, dyspepsia, nasopharyngitis, and gastroenteritis (Dietsch et al. 2006). Roflumilast, apremilast, and cilomilast, which are second-generation selective inhibitors, are typically better tolerated; however, this is likely due to the doses that do not produce persistent PDE4 inhibition (Spina 2008; Tashkin 2014; Abdulrahim et al. 2015). Most PDE4 inhibitors are non-specific to all four PDE4 subtypes and modulate cAMP concentrations above the normal physiological function limits (Burgin et al. 2010).

Mechanism of Adverse Effects

PDE4-related adverse effects and their molecular mechanisms are discussed in this section. For instance, PDE4 inhibition has been reported to cause hypothermia, as evidenced by several preclinical investigations in experimental rodent models (Wachtel 1983; McDonough et al. 2020b). This effect is regulated by dopamine signaling in the hypothalamus following PDE4 inhibition (McDonough et al. 2020b). PDE4 Inhibition is also known to cause dizziness (Blokland et al. 2019b). Among all PDE4 subtypes, PDE4D is highly expressed in the cochlear and vestibular nuclei of the brainstem (Pérez-Torres et al. 2000). The mRNA expression of PDE4D1, PDE4D2, and PDE4D3 has been observed in the dorsal cochlear and vestibular nuclei of rats (Miró et al. 2002). Because of the signal transmission of the cochlear and vestibular nuclei from the inner ear, modified cAMP regulation by PDE4 inhibition at these locations may cause dizziness, nausea, and emesis via subsequent transmission to other brainstem regions. Interestingly, the vestibular system in the inner ear expresses the PDE4D subtype and rolipram induces endolymphatic hydrops in mice, which is related to dizziness (Degerman et al. 2017). Diarrhea is a gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effect of PDE4 inhibition. Through PKA-dependent activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), diarrhea may be caused by PDE4 inhibition via elevation of intestinal Cl− secretion (Chao et al. 1994). PDE4D has been reported to be involved in CFTR by binding to Shank2 (scaffolding protein), indicating that PDE4D may be involved in mediating this effect through PDE4 inhibition (Ji et al. 2007). Moreover, PDE4 inhibition is known to cause serotonin receptor 5HT4–mediated Ach release, prompting contraction of circular smooth muscle in the large intestinal region (Pauwelyn et al. 2018). Owing to the diarrhea-related adverse effects of PDE4 inhibition, roflumilast in mice exhibited an anti-diarrheal effect, which might be correlated with the anti-spasmodic actions of the jejunum possessed by roflumilast (Rehman et al. 2020).

PDE4 appears to be involved in nausea and emesis in both CNS and GI systems. Intravenous administration of rolipram and Ro20-1724 In an early study conducted in anesthetized rats triggered an increase in gastric acid and pepsin secretion (Puurunen et al. 1978). Another study suggested that PDE4D subtypes are primarily expressed in pepsinogen-releasing chief cells present in the stomach, whereas PDE4A is expressed in acid-releasing parietal cells (Lamontagne et al. 2001). This adverse effect of PDE4 inhibition in the body (periphery), specifically in the GI system may be overcome by brain-specific drug delivery which has been discussed in the next section (Drug delivery modification techniques and brain-specific delivery). In addition, the binding of PDE4 inhibitors to the high-affinity rolipram binding site (HARBS) in gastric glands is strongly associated with the degree of gastric acid release (Barnette et al. 1995). First-generation non-specific PDE4 subtype inhibitors bind to HARBS, causing a tremendous increase in cAMP levels, causing unfavorable adverse effects of nausea and emesis (Jeon et al. 2005). However, second-generation PDE4 inhibitors, such as cilomilast, are known to bind to the low-affinity rolipram binding site (LARBS), yet they still cause emesis (Torphy et al. 1999). Interestingly, roflumilast strongly inhibited gastroparesis compared to a selective PDE4B inhibitor, suggesting that the contribution of PDE4B inhibition to gastric-related adverse effects is minimal (Suzuki et al. 2013). Recently, a study in mice showed that non-selective PDE4 inhibitors induce gastroparesis (McDonough et al. 2020a). Specifically, genetic deletion of one PDE4 subtype had no effect on gastroparesis or protected against PDE4 inhibitor-induced gastroparesis, as reported in this study. Therefore, two or more PDE4 subtypes may be involved in PDE4-mediated gastroparesis. The physiological effect of PDE4 inhibition requires additional exploration as a probable prognostic measure for the adverse effect profile of PDE4 inhibitors given that gastroparesis is highly related to nausea and emesis in humans (Grover et al. 2019). The emetogenic potential of PDE4 inhibitors may be due to the presence of PDE4 in the area postrema (AP) of the human brainstem which is considered the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) for emesis. The AP is located on the dorsal surface of the medulla oblongata at the caudal end of the fourth ventricle (Jovanović-Mićić et al. 1989). The presence of mRNAs encoding PDE4A, PDE4B and PDE4D in AP has been shown in rats (Takahashi et al. 1999; Pérez-Torres et al. 2000) and it has been suggested that cAMP signaling modification in this area could mediate the emetic effects of PDE4 inhibitors. In particular, one study using in situ hybridization histochemistry found that the hybridization signals for PDE4B and PDE4D mRNAs in the AP were stronger than those in any other nuclei such as the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsal vagal motor nucleus in the human brainstem which are also known to play an emetic role (Mori et al. 2010). However, the hybridization signal for PDE4D mRNAs was found higher in the AP compared to the signals of PDE4B mRNAs. Moreover, the high expression of PDE4D in the AP was correlated with a previous study where expression of PDE4D mRNA and immunoreactivity were detected in the medulla and nodose ganglion of squirrel monkeys (Lamontagne et al. 2001) and a study that reported the presence of PDE4D immunoreactivity in mouse area postrema PDE4D (Cherry and Davis 1999). However, the role of PDE4B in AP remains unclear and requires further investigation. Activation of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway in brainstem AP is involved in emesis. This was demonstrated by a study showing that microinjection of cAMP analogs such as 8-bromocAMP or forskolin in the AP of the brainstem induces emesis in dogs (Nestler et al. 2002). Therefore, this suggests that activation of cAMP/PKA through PDE4 inhibition in the AP may be responsible for the emetic effect of several PDE4 inhibitors such as rolipram. However, selective PDE4 subtype inhibition may not impart an emetic effect based on the specific expression of PDE4 subtypes in the AP of the brainstem. This information may thus help to develop PDE4-subtype specific inhibitors that do not display emetic potential by not causing cAMP modification in the AP of the brainstem. Moreover, it has also been suggested that PDE4 inhibitors produce a pharmacological response analogous to that of α2-receptor antagonists, which elevate intracellular levels of cAMP in noradrenergic neurons. The α2-receptor activation in turn decreases intracellular cAMP levels in noradrenergic neurons, which subsequently decreases neurotransmitter secretion in the synaptic cleft. Thus, PDE4 inhibitors are assumed to modulate the release of mediators, including 5-HT, substance P, and noradrenaline, which are involved in the onset of the emetic reflex mediated at emetic brainstem centers (Robichaud et al. 2001).

Strategies to Overcome Adverse Effects and Improve the Efficacy of PDE4Is to Treat PD

Allosteric Modulation and PDE4 Subtype Specificity

Studies have highlighted allosteric modulation and PDE4 subtype specificity as positive strategies to prevent the adverse effects associated with PDE4 inhibition. For instance, PDE4 is essential for anesthesia induced by α2-adrenoceptor activation. With the induction of ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, a behavioral observation model of emesis in non-vomiting species, PDE4D-knockout mice, but not PDE4B-knockout mice, was observed to sleep less than wild-type mice. The results showed that PDE4D inhibition was most likely responsible for emetogenic and other adverse effects (Robichaud et al. 2002). This emphasizes the importance of developing particularly effective PDE4 subtype inhibitors or allosteric modulators to alleviate the aforementioned adverse effects (Pagès et al. 2009; Page 2014). The X-ray crystallography approach has recently been beneficial for identifying binding modes and developing effective PDE4 subtype inhibitors (Xu et al. 2000). Within the UCR2 region, PDE4D contains phenylalanine (Phe) at position 196, whereas PDE4A, B, and C contain tyrosine at position 274. UCR2-directed allosteric modulators are known to reduce interactions or take advantage of PDE4 conformers by inhibiting one of the active sites and partially restricting cAMP hydrolysis, with a maximal PDE4 inhibition of more than 50%. Therefore, they are less likely to cause emesis and nausea, whereas their biological activities are conserved and unaffected (Burgin et al. 2010; Gurney et al. 2011). Interestingly, D159687, a UCR2-directed negative PDE4D allosteric modulator, bridged Phe196 of PDE4D and did not elicit emesis in mice, as projected by the anesthetic duration test (Titus et al. 2018). Therefore, allosteric modulation may provide a method for clinical application of PDE4 inhibitors.

Many a times the adverse effects are often assessed in non-primate species (for example, rodents, dogs, and ferrets); therefore, it is essential to note that these tests do not adequately represent PDE4 inhibitors as potentially emetogenic, as they target PDE4D subtype phenylalanine in the UCR2 region in primates. Interestingly, several PDE4Is, including the PDE4D-specific inhibitor BPN14770, which bind to HPDE4, are well tolerated in humans and have been used safely at higher doses than rolipram [NCT02648672] [NCT02840279] (Tetra Discovery Partners 2016). However, the desired therapeutic efficacy depends on the required dose. Thus, for any given disease indication, the final therapeutic window or dose range that produces therapeutic but no adverse effects might still be identical to that of rolipram (Paes et al. 2021). However, many recently developed PDE4 inhibitors have high affinities for specific subtypes and abated emetogenicity compared with rolipram. For example, PDE4 inhibition by FCPR16 did not elicit emesis in beagle dogs at a dose of 3 mg/kg, which was converted from 10 mg/kg in rats using the dosage conversion factor, indicating that FCPR16 has reduced emetogenic potential (Chen et al. 2018b). However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Moreover, FCPR16 displays approximately 600-fold selectivity for PDE4B and 1111-selectivity for PDE4D over other PDEs (Zhou et al. 2016b). Another PDE4 inhibitor, FCPR03, at 0.8 mg/kg, inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α, iNOS, and COX-2 production in microglial cells and did not trigger emesis in beagle dogs throughout 180 min of observation (Zhou et al. 2016a; Zou et al. 2017). Interestingly, two novel aminophenylketones (9C and 9H) were also generated by structure-based optimization of FCPR03 with low nanomolar potency, comparable activity to rolipram, adequate bioavailability, low emetogenicity, and improved blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Further research has indicated that 9H enhances memory and cognitive impairment in Aβ25–35-induced AD mouse models (Xia et al. 2022). Both FCPR03 and FCPR16, which show promising activity against neurodegenerative diseases, have low oral bioavailability. However, arylbenzylamine derivatives 11r and 11 s, as discussed in the previous section, have better oral bioavailability; specifically, 11r displays nearly sevenfold higher oral bioavailability (8.20%) than FCPR03 (1.23%) (Tang et al. 2019). These arylbenzylamines were designed using FCPR16 and FCPR03 as the lead compounds. Structure-based optimization of α-mangostin with a xanthone scaffold also led to the development of the potent PDE4 inhibitor 4e, with an IC50 of 17 nM against PDE4D2. The PDE4 inhibitor 4e showed a potential therapeutic effect in a vascular dementia (VaD) model and did not induce emesis in beagle dogs at a dose of 10 mg/kg compared to rolipram. 4e also displayed partial inhibitory behavior against the long PDE4B subtype (60% inhibition at high doses) (Liang et al. 2020). 4e is likely a PDE4B allosteric modulator that does not cause emesis. 4e was later shown to exhibit promising disease-modifying effects in PD, as discussed in the previous section. Thus, structure-based optimization techniques can be used to develop PDE4 subtype-specific inhibitors with improved oral bioavailability and reduced chances of adverse effects by choosing lead scaffolds with desired physicochemical characteristics to treat PD.

Drug Delivery Modification Techniques and Brain-Specific Delivery

Oral drug delivery of PDE4Is is the most common form of drug administration because of several advantages such as convenience, patient preference, cost-effectiveness, and ease of large-scale manufacturing of oral dosage forms. The compliance of patients with oral formulations was generally higher. However, orally administered PDE4Is must survive the harsh gastrointestinal environment, penetrate the enteric epithelia, and circumvent hepatic metabolism (including the first-pass effect) before reaching systemic circulation. Drug solubility also affects the oral bioavailability (Khan and Singh 2016). PDE4Is with low aqueous solubility have a low oral bioavailability. However, novel drug delivery techniques can overcome these disadvantages of orally administered PDE4Is. These techniques include micronization, nanosizing, co-crystallization, solid-lipid nanoparticles (SLN), microemulsions, self-emulsifying drug delivery systems, self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems, and liposomes (Alqahtani et al. 2021). Lipid-based drug delivery systems can enhance the lymphatic delivery of hydrophobic drugs by utilizing different lipid carriers, which can significantly improve the oral bioavailability (Khan et al. 2013).