Abstract

Background

Nearly half of patients diagnosed with cancer are in the middle of their traditional working age. The return to work after cancer entails challenges because of the cancer or treatments and associated with the workplace. The study aimed at providing more insight into the occupational outcomes encountered by workers with cancer and to provide interventions, programs, and practices to support their return to work.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using the Arksey and O’Malley framework and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for scoping review guidelines. Relevant studies were systematically searched in PubMed/MEDLINE, SCOPUS and Grey literature from 01 January 2000 to 22 February 2024.

Results

The literature search generated 3,017 articles; 53 studies were considered eligible for this review. Most of the studies were longitudinal and conducted in Europe. Three macroarea were identified: studies on the impact of cancer on workers in terms of sick leave, employment, return to work, etc.; studies reporting wider issues that may affect workers, such as the compatibility of treatment and work and employment; studies reporting interventions or policies aiming to promote the return to work.

Conclusion

There is a lack in the literature in defining multidisciplinary interventions combining physical, psycho-behavioural, educational, and vocational components that could increase the return-to-work rates. Future studies should focus on interdisciplinary return to work efforts with multiple stakeholders with the involvement of an interdisciplinary teamwork (healthcare workers and employers) to combine these multidisciplinary interventions at the beginning of sick leave period.

Keywords: Cancer, Intervention, Return to work, Scoping review, Work ability

1. Introduction

In industrialized countries, the number of cancer survivors (CSs) has increased over the past few decades, due to major advances in cancer care [1]. Nevertheless, cancer is still a major public health and economic issue; indeed, globally, there were an estimated 20 million new cases of cancer worldwide and 10 million deaths from cancer in 2020 [2]. Due to the aging population, 29 million cases by 2040 are expected [3]. On the base of GLOBOCAN estimates, the annual incidence of new cases is about 19 million [4]. In this regard, cancer has a remarkable economic, social, and health impact on individuals and the entire communities [5,6]. The disease has a serious impact on both life and working life of patients. Cancer patients often report high rates of financial hardship, also due to the expensive cancer treatment. Moreover, in many cases the disease brings inevitable repercussions to work activity of cancers patients due to the large limitations in their employability and making them no longer able to support themselves financially and their families [[7], [8], [9]].

Almost half of the patients diagnosed with cancer are in the middle of their traditional working age (20 and 65 years) [10,11]. The main physical, emotional, and cognitive fatigue, along with several other cancer-related symptoms and weakening, such as emotional strain, depression, anxiety, pain, reduced attention, and memory interfere with people’s ability to work, with an effect also on the employment status, job opportunities, work participation, and work capacity [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]]. Return to work (RTW) after cancer entails challenges associated with the recurrent effects of the cancer or treatments (e.g., fatigue, pain), as well as challenges associated with the workplace (e.g., lack of support, discrimination, being fired, stigmatization) [8,9,19]. In this context, a high rate of absenteeism occurs in the period following cancer diagnosis due to both physical and psychological impairments that influence the RTW and the employment rates [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]], with a mean RTW rate post-diagnosis of 63.5%, ranging from 24% to 94% [25].

RTW can be an important part of survivorship, in terms of economic contributions, sense of purpose and normality, increase in quality of life (QoL), and benefits to physical and mental health [6,7,26,27].

Sociodemographic factors (age, gender, education, etc.) and work-related factors (e.g., adjustment to work), are also associated with impaired RTW [16,28,29].

Therefore, it is a priority providing policies and practical interventions to support an earlier RTW and employability of cancer patients and survivors. In literature reviews, various types of strategies are described, aimed at guaranteeing workers specific and reasonable accommodations, reducing their working hours, foreseeing more flexible working hours, and providing paid sick leave, modifying workload, changing duties or working activities, informing about psycho-educational interventions and rehabilitation services [15].

2. Objectives

The aim of the present scoping review consists of providing more insight into the occupational outcomes associated with CSs encountered by workers affected by cancer and provide an extensive mapping on interventions, programs, and practices to support the RTW of workers affected by cancer, also gathering information on good practice examples of RTW interventions.

Furthermore, it will also examine the extent and scope of the pre-existent literature, in order to summarize the research results, to identify research gaps on this specific field and to provide a rationale for further relevant research in this area.

3. Methods

Scoping reviews are the types of studies in the field of systematic reviews that are increasingly widespread, due to the growing of scientific publications. The systematic reviews are typically focused on a well-defined question where appropriate study designs can be identified in advance; and they aimed at providing answers to questions from a relatively narrow range of quality-assessed studies. A scoping study is less likely to address the very specific research questions nor, consequently, to assess the quality of included studies. Furthermore, scoping studies tend to address broader topics where different study designs might be applicable, with the aim of mapping the scientific literature in a research area, evaluating its volume, characteristics, type of evidence available, key concepts, and gaps.

We performed this scoping review following the guidelines outlined by Arksey and O’Malley, the Joanna Briggs Institute recommendations and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [[30], [31], [32]].

The steps usually considered in a scoping review are: 1) identifying the research question; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) study selection; 4) charting the data; 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

3.1. Study selection/search strategy

Relevant studies were systematically searched in PubMed/MEDLINE and SCOPUS database from 01 January, 2000, to 22 February, 2024. Details of the search strategy are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| PubMed/MEDLINE | ((Neoplasms[MeSH Terms]) OR (Neoplasm∗)) OR (Cancer∗)) OR (Oncolog∗)) OR (Tumor)) OR (Malignan∗)) AND ((Return to work[MeSH Terms]) OR (Return to work)) OR (RTW)) OR (Employment[MeSH Terms])) OR (Employment)) OR (Unemployment[MeSH Terms])) OR (Unemployment)) OR (Unemployed)) OR (Retirement)) OR (Sick leave[MeSH Terms])) OR (Sick leave)) OR (Sickness absence)) OR (Absenteeism[MeSH Terms])) OR (Absenteeism)) OR (Work[MeSH Terms])) OR (Work adaptation)) OR (Job adaptation)) OR (Work-life balance[MeSH Terms])) OR (Work resumption)) OR ("Job retention")) OR ("Job integration")) OR ("Job reintegration")) OR ("Job maintenance")) OR (fitness work judgement))) AND ((Vocational rehabilitation[MeSH Terms]) OR (Rehabilitation [mh:noexp])) OR (Neoplasm rehabilitation)) OR (Vocational∗)) OR ("Work rehabilitation")) OR ("Reasonable accommodation")) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (((neoplasms) OR (neoplasm∗) OR (cancer∗) OR (oncolog∗) OR (tumor) OR (malignan∗))) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((return AND to AND work) OR (rtw) OR (employment) OR (unemployment) OR (unemployed) OR (retirement) OR (sick AND leave) OR (sickness AND absence) OR (absenteeism) OR ("Work") OR (work AND adaptation) OR (job AND adaptation) OR (work-life AND balance) OR (work AND resumption) OR ("Job retention") OR ("Job integration") OR ("Job reintegration") OR ("Job maintenance") OR (fitness AND for AND work AND judgement)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (((vocational AND rehabilitation) OR (rehabilitation) OR (neoplasm AND rehabilitation) OR (vocational∗) OR ("Work rehabilitation") OR ("reasonable accommodation"))) |

| Gray literature (Google Scholar/GreyLit) | Cancer AND return to work |

3.2. Criteria for considering relevant studies

We determined the information to extract a priori. We chose a comprehensive search methodology to describe an accurate picture of the relationship between the occupational outcomes and cancer. Studies that did not report the mentioned outcomes were excluded from this review as those focused on childhood CSs. We focused on the working age population (≥15 years old) who had been diagnosed with cancer and were employed at the time of diagnosis. We included studies conducted with people who had any type of cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, papers published before the year 2000 were excluded to ensure that the review results were based on sufficiently recent studies. Only articles written in English were considered in the study. Systematic reviews, literature reviews, scoping reviews, conference abstracts, commentaries, letters to the editor, expert opinions, case reports, case series, and editorials were excluded.

To summarize, the eligibility criteria were:

-

-

studies on working-age population (≥15 years) from any country and any occupational group or economic activity sector;

-

-

studies on worker CSs, any type of cancer;

-

-

studies reporting the impact of cancer on workers affected by cancer (days lost, absenteeism, sick leave, etc.);

-

-

studies reporting wider issues that may affect the worker, such as the compatibility of treatment and work and employment (work-life balance, adaption of equipment, reasonable accommodation, fitness for work judgement, etc.);

-

-

studies reporting interventions or policies aimed at promoting the RTW of CSs;

-

-

studies available in full text and in English.

After the removal of duplicates, performed using the EndNote X9.2 software, articles were identified and imported onto the Covidence. This is a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews, where we performed an initial screening of titles and abstracts to assess potential relevance and exclude those not focused on our area of interest. With the aim to increase the consistency among reviewers, all reviewers screened a sample of articles and discussed the results, adjusted the screening and data extraction criteria before beginning the screening phase. Four reviewers worked in pairs to evaluate the titles and abstracts. Relevant full-text articles were read and the evaluation on eligibility was carried out by two reviewers to determine their final inclusion or exclusion. One researcher resolved disagreements on study selection [32].

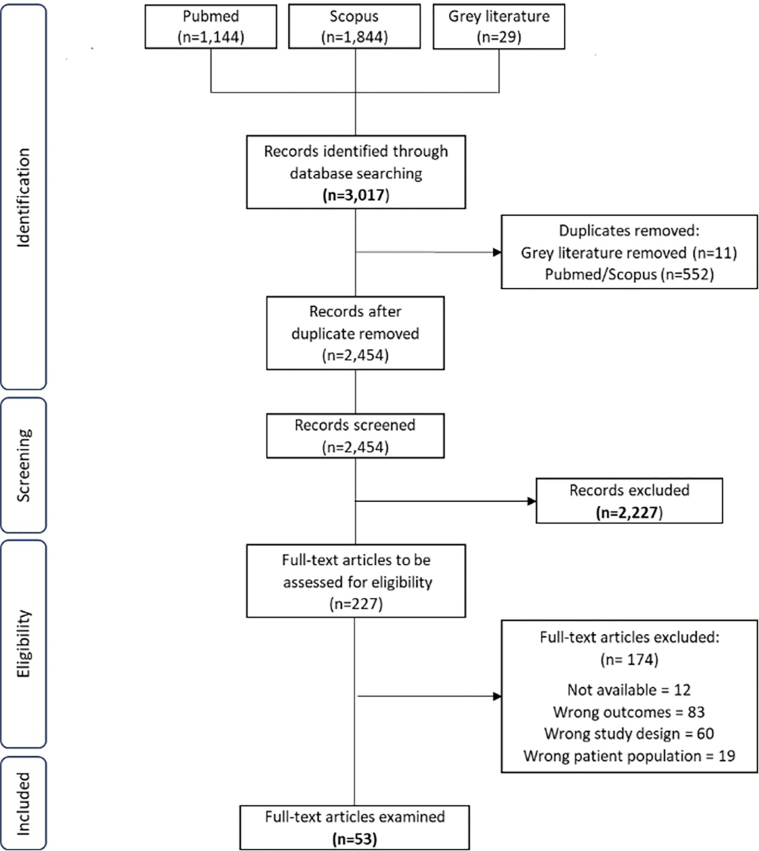

In case of lack of information or full text not being available, we tried to contact the corresponding author; in case our request failed, the paper was excluded. In Fig. 1, the PRISMA flow chart overview of the search and screening strategy is shown.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process, PRISMA flowchart. PRISMA - Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation.

3.3. Data charting process

To determine which variables to extract, a data-charting form was developed by the reviewers after an iterative process. Data from eligible studies were charted using an Excel file ad hoc previously prepared with information on the authorship, publication year, country, type of study, sample size and details summary, age, period/duration of the study, type of cancer, aims, outcomes, and main results.

Outcomes related to occupational context were related to employment status, RTW rate, changing work or type of work, sick leave period, early retirement, strategies of vocational rehabilitation, and job accommodations. Need for a change of employment due to cancer, difficulties perceived at work, work and working life in general, barriers to employment, degree of job satisfaction, the impact of work on social and private life were also included.

Regarding the types of interventions, we considered any type of intervention aiming to improve RTW, also focus on different factors which influence RTW, such as workplace adjustments (in vocational interventions), therapies, physical interventions, minimal surgery (in medical interventions), or a combination of those factors (in multidisciplinary interventions). We considered vocational interventions (modified work hours, modified work tasks, or modified workplace and improved communication with or between managers, colleagues, and health professionals), physical interventions (any type of physical training), and overall QoL measurements.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of the literature search

Our search strategy generated 3,017 articles. After duplicates were removed, a total of 2,454 papers were identified from searches of electronic databases and review article references. Based on the title and the abstract, 2,227 papers were excluded, with 227 full text articles to be retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 174 were excluded for the following reasons: 83 were not directly related to the selected outcomes; 60 studies were not considered to be original quantitative research (e.g., review articles, commentaries); 19 did not consider working population; we also excluded 12 studies because we were unable to retrieve it. The remaining 53 studies were considered eligible for this review. The results are described in Fig. 1.

4.2. Characteristics of the included studies

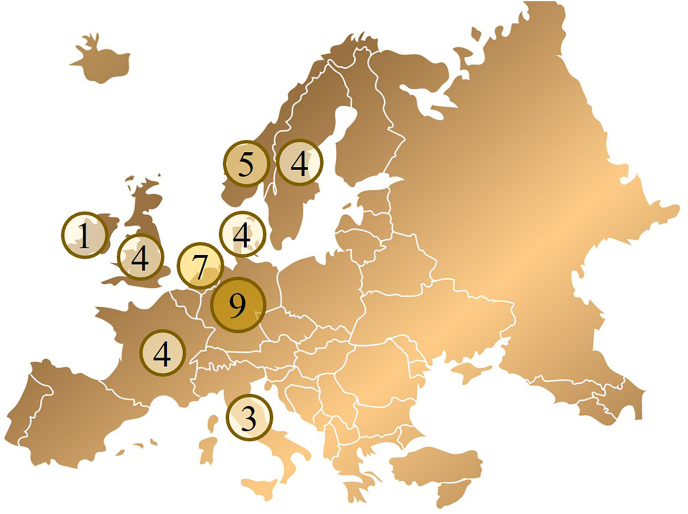

Thirteen studies were conducted in the period 2005–2011 [17,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]], 16 studies in 2012–2017 [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]] and 24 studies in 2018–2023 [[61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84]]. Most of the included studies were conducted in Germany (n = 9) [49,59,62,63,66,67,69,76,83], followed by the Netherlands (n = 7) [37,41,42,50,60,70,78], Norway (n = 5) [39,44,46,52,75], France [38,61,73,74], Sweden [36,40,55,65], Denmark [47,77,79,81], Korea [17,53,58,68], and UK [35,48,51,54] (n = 4), Italy [64,72,80] and USA [33,34,45] (n = 3), India [57,82] (n = 2), and one from Australia [71], Ireland [43], Taiwan [84], and Japan [56] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of studies in European countries. Extra European countries (n = 12): Korea (n = 4), USA (n = 3), India (n = 2), Australia, Japan, and Taiwan (n = 1).

Twenty-five are longitudinal studies [17,33,36,38,44,46,49,51,[54], [55], [56],[58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63],65,66,69,71,73,75,81,83], both prospectives and retrospectives (4 are case-control studies); 21 cross-sectional studies [34,35,37,39,40,43,45,48,53,57,64,67,68,70,72,74,76,79,80,82,84]; 4 register-based cohort studies [41,42,47,52] and 3 were randomized controlled trials [50,77,78]. Fifteen studies analyzed breast cancer, blood cancer (Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, myeloma, and others: n = 4), colorectal/rectal and prostate cancer (n = 2), head and neck cancer (n = 2), lung cancer (n = 1). All other studies analyzed several kinds of tumors (Appendix I).

As described in the methods section, studies were selected also according to the main identified macroarea:

-

1.

Studies reporting the impact of cancer on workers affected by cancer (e.g., days lost, absenteeism, sick leave, etc.). Most studies (n = 51) have analyzed these topics. Outcomes are mostly explained through quantitative measures, related to RTW rate, employment/unemployment characteristics, sick leave time, absenteeism, and sickness absence. The RTW rate was the most explored variable (n = 33, 47.1%); relative risk of RTW were mainly considered as outcome variables in case-control/intervention-control studies. Significant addressed issues were the employment/unemployment rate, employment type of wage, salary, type of contract, working hours, and disability pension (n = 14; 20.0%). Median/mean duration of sick leave, length of sickness absence, long sick leave (n = 11; 15.7%) were also considered in the selected studies.

Sociodemographic factors associated to the RTW of workers affected by cancer were also considered in many studies belonging to this macroarea, such as: gender, age at diagnosis, stage of disease, level of education, marital status, type of work (manual/non-manual work), type of contract, salary, etc. The foremost facilitation of RTW was related to male, younger age at diagnosis, less advanced stage of disease, higher education, being married, non-manual work, and higher income. Individuals who had undergone chemotherapy and those perceiving physical limitations had a higher risk of difficulty in the RTW process.

-

2.

Studies reporting wider issues that may affect the worker, such as the compatibility of treatment and work and employment (work-life balance, adaption of equipment, reasonable accommodation, etc.). Twelve studies belong to this matter, where qualitative outcomes/measures are analyzed. Changes in the type of job or in working hours, flexibility, less physical and mental effort were reported in five studies, while three papers considered issues related to health and QoL, work ability, and social support at work. More specific matters linked to work adjustments in the workplace, formal request for work accommodations, accommodations in work tasks or schedule were analyzed in three studies.

-

3.

Studies reporting interventions or policies aiming to promote the RTW of CSs were less commonly explored aspects in the studies (n = 7). Different type of support from the employer or from rehabilitation institutions were reported in three articles; employer-based policies and co-worker support (from supervisors and colleagues), the role and interventions of occupational physician and support in terms of feeling of discrimination aimed to facilitate the RTW process were also reported in three studies. Vocational rehabilitation intervention issues were also dealt only in one study. Intervention is especially focused on the collaboration between survivors, oncologists, and occupational health physicians and nurses on the opportunities to assist and improve the RTW process; in this context, the need for improved employer-based policies and programs and education about legal protection were suggested in the article.

5. Discussion

In industrialized countries, the number of patients who survive cancer has significantly increased in the recent decades; consequently, the interest on the part of institutions and research institutions in studying and analyzing the phenomenon of reintegration into employment of these patients is growing [1]. It is by now a shared opinion that the ability to remain, even partially, professionally actives represent an added value in maintaining a good QoL from both an economic and social point of view [6,7,26,85].

However, approximately 60% (ranging from 30% to 93%) of cancer patients return to work only after one or two years [86,87]. This data has been confirmed also by a more recent meta-analysis [88], in which the overall rate of RTW was at 57% (50%–65%). According to Spelten et al. [87], patients with head and neck cancer and breast cancer reported most problems upon their RTW. Patients with testicular cancer generally reported very few problems upon RTW and had a high rate of RTW.

Cancer patients who return to work, in many cases, face with barriers that affect their ability to work, including an inadequate work, lack of support and solidarity from colleagues and the employer, lack of cooperation between the employer and the occupational physician, the perception of being discriminated, etc. [64,67,72].

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health states that the potential RTW for persons with limited abilities depends not only on the disease itself but also on health planning skills and social reintegration policies [72].

In this perspective, a better knowledge of cancer and the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial consequences related to the disease could contribute to the development of policies and practical interventions for a faster RTW and employability of cancer patients and survivors.

Occupational physicians and general practitioners should consider the factors associated with reduced work capacity to promote work reintegration [64].

For this purpose, our study aims to contribute to the identification of research gaps regarding the RTW of CSs, with the final goal of providing a logical basis for further relevant research that can lead to the definition of specific interventions, practices and programs useful to support the RTW.

Our study shows that although the scientific literature on the occupational outcomes of cancer is considerable, several important gaps in knowledge exist. Indeed, some important factors that affect CSs’ RTW, such as sociodemographic, work and illness factors [16,28,59,63], have been investigated. However, studies aimed at identifying tools, practices, and policy interventions aimed at promoting rehabilitation and RTW are lacking. Therefore, studies that specifically examine the impact of reasonable accommodations on RTW are needed. Few studies carried out on this topic report that the main reasonable accommodations have concerned professional interventions such as the reduction of working hours, changes in the workstation, changes in working hours, tasks, and work activities. These solutions are mostly identified for CSs with permanent contracts and employees of large companies [80]. Only a few interventions are available for small and medium-sized enterprises and the self-employed affected by cancer [15].

The changes in working hours mainly affected patients with nervous system cancer and lymphoma, or patients treated with chemotherapy, as it deals with cancer diagnoses that lead to considerable side effects and disease-related disabilities with the ensuing greater flexibility of working hours to reconcile work and treatments.

Furthermore, some studies underline the key role of the employer in supporting workers affected by cancer during the disease and in their RTW. However, it arises on the part of the workers a lack of knowledge of work reintegration policies implemented by the employer, and some difficulty for CSs in finalizing a formal request for reasonable accommodation [45,48].

Another important issue is the lack of scientific evidence on the impact of the adopted interventions on the RTW of cancer patients. In particular, according to de Boer et al. [86], interventions can be psycho-educational (such as education, counseling, coping skills), vocational (such as vocational rehabilitation or workplace adjustments), and physical (any type of physical exercises). A combination of these interventions in a multidisciplinary approach can be desirable. The lack of evidence results in high psycho-educational interventions, while moderate scientific evidence is found in multidisciplinary interventions involving physical, psycho-educational, and/or vocational components.

However, there is adequate scientific evidence regarding the positive correlation between the probability of returning to work and vocational interventions, in particular, interventions that allow flexible working hours during and after work, or changes in the workstation [15,73,79].

With regards to future interventions to support CSs returning to work, one study suggests that lessons could be learned from the experience of vocational rehabilitation in other groups with long-term health problems [48].

An important aspect that emerges from our study is that multidisciplinary interventions to support the RTW of cancer patients have shown limited effectiveness. Instead, there is a need for interventions that are adapted to the needs and prognostic factors of individual patients, easily achievable and compatible with national legislation [80].

Occupational health professionals play a key role in the process of cancer patients RTW, given their clinical experience, knowledge of the workplace and awareness of the legal protections available for workers [45].

In recent years, studies based on literature reviews have been carried out on the topic of CSs and RTW. Our study is mostly in line with the results emerging from the main literature reviews on this topic. This study has some limitations due to the inherent characteristics of the study design. Indeed, the aim of scoping review is to provide breadth rather than the depth of information in a particular topic. Furthermore, only studies written in English were included, excluding possibly relevant papers in other languages. According to the scoping review approach, assessment of the quality of included studies was not performed; this leads to the inclusion of studies with different quality levels, limiting the reliability of the findings. However, given that our objective was to provide an extensive mapping of interventions and practices to support the RTW of workers affected by cancer, this study design is the most appropriate. The strength of our article lies, indeed, in the possibility of formulating a broad research question which allowed us to take into consideration a wide range of interventions to support the RTW of CSs. This broad research question led to the inclusion of a large number of articles in the review, that exceeded 50 studies included.

The literature review shows that white collar job, early tumor stage, self-motivation, normalcy, acceptance to maintain a normal life, support from the friends, family and workplace, and employment-related health insurance are the important factors that facilitate survivors’ RTW. Also, younger age, higher levels of education, continuity of care, absence of surgery, less physical symptoms, the length of sick leave, male gender, and ethnicity are considered as factors that facilitate the RTW [16,89]. Likewise, old age, low education, low income, and heavy work were negatively associated with employment [90].

Evidence from literature reviews pointed out the need in developing an intervention theory and a logic model, with stakeholders consistent with the RTW needs of CSs [7], due to the great heterogeneity among studies in terms of type of intervention and use of methodologically rigorous approach. The need for a better definition of the concept of RTW is also pointed out among the issue of the heterogeneity of interventions, through the use of an accurate approach also to define the outcome measures to evaluate RTW [91]. Future studies should have higher methodological quality. Efforts to reach more uniformity in design and methods are called for [92]. Reviews also pointed out that outcome measures depend on the country in which the study is realized [93]. An important issue is related to the fact that most studies come from high-income countries and only few from low- and middle-income countries and papers on factors that affect RTW among the CSs in low-and middle-income countries are scarce; in this respect, results could be very different [89].

Only few interventions are primarily aimed at enhancing RTW in patients with cancer and most do not fit the shared care model involving integrated cancer care. Future studies should be developed with well-structured work-directed components that should be evaluated in randomized controlled trials [94]. There is a need for more high-quality prospective studies to enhance interventions supporting the vocational rehabilitation of CSs.

As we already reported in our study, future studies should focus on interdisciplinary RTW efforts with multiple stakeholders. In this respect, it would be important to fill the lack in literature in defining multidisciplinary interventions that combine physical, psycho-behavioral, educational, and vocational components that could increase the RTW rates. All this could be achieved through the involvement of an interdisciplinary teamwork (healthcare workers and employers) to combine these multidisciplinary interventions at the beginning of the sick leave period [27].

Funding

No funding was obtained for this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Giuliana Buresti: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization. Bruna M. Rondinone: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization. Antonio Valenti: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Fabio Boccuni: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Grazia Fortuna: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Sergio Iavicoli: Validation, Conceptualization. Maria Cristina Dentici: Writing – review & editing. Benedetta Persechino: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2024.07.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bilodeau K., Tremblay D., Durand M.J. Exploration of return-to-work interventions for breast cancer patients: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1993–2007. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Burden of Cancer [Internet]. The cancer atlas. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: http://canceratlas.cancer.org/Xoh.

- 4.Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., Parkin D.M., Piñeros M., Znaor A., et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. 2021;5 doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garlasco J., Nurchis M.C., Bordino V., Sapienza M., Altamura G., Damiani G., et al. Cancers: what are the costs in relation to disability-adjusted life years? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blinder V.S., Gany F.M. Impact of cancer on employment. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(4):302–309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO report on cancer: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all [Internet]. [cited Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240001299.

- 8.Choi J.W., Cho K.H., Choi Y., Han K.T., Kwon J.A., Park E.C. Changes in economic status of households associated with catastrophic health expenditures for cancer in South Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(6):2713–2717. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.6.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leng A., Jing J., Nicholas S., Wang J. Catastrophic health expenditure of cancer patients at the end-of-life: a retrospective observational study in China. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0426-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boer A.G.E.M., Taskila T., Ojajärvi A., van Dijk F.J.H., Verbeek J.H.A.M. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301(7):753–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer A.G., Torp S., Popa A., Horsboel T., Zadnik V., Rottenberg Y., et al. Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(2):135–150. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00862-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M.E., Hermann S., Arndt V., Steindorf K. Prevalence and severity of long-term physical, emotional, and cognitive fatigue across 15 different cancer entities. Cancer Med. 2020;9(21):8053–8061. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feuerstein M., Todd B.L., Moskowitz M.C., Bruns G.L., Stoler M.R., Nassif T., et al. Work in cancer survivors: a model for practice and research. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(4):415–437. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silver J.K., Baima J., Newman R., Galantino M.L., Shockney L.D. Cancer rehabilitation may improve function in survivors and decrease the economic burden of cancer to individuals and society. Work. 2013;46(4):455–472. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehabilitation and return to work after cancer — instruments and practices | Safety and health at work EU-OSHA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/rehabilitation-and-return-work-after-cancer-instruments-and-practices.

- 16.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77(2):109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J.H., Park J.H., Kim S.G. Effect of cancer diagnosis on patient employment status: a nationwide longitudinal study in Korea. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):691–699. doi: 10.1002/pon.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahar K.K., BrintzenhofeSzoc K., Shields J.J. The impact of changes in employment status on psychosocial well-being: a study of breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26(3):1–17. doi: 10.1080/07347330802115400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S., Zhu W., Thompson P., Hannun Y.A. Evaluating intrinsic and non-intrinsic cancer risk factors. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3490. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakovljevic M., Malmose-Stapelfeldt C., Milovanovic O., Rancic N., Bokonjic D. Disability, work absenteeism, sickness benefits, and cancer in selected European OECD countries—forecasts to 2020. Front Public Health. 2017;5:23. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolvers M.D.J., Leensen M.C.J., Groeneveld I.F., Frings-Dresen M.H.W., De Boer A.G.E.M. Predictors for earlier return to work of cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(2):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0655-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leensen M.C.J., Groeneveld I.F., van der Heide I., Rejda T., van Veldhoven P.L.J., Berkel S van, et al. Return to work of cancer patients after a multidisciplinary intervention including occupational counselling and physical exercise in cancer patients: a prospective study in The Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsey S.D., Bansal A., Fedorenko C.R., Blough D.K., Overstreet K.A., Shankaran V., et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilligan A.M., Alberts D.S., Roe D.J., Skrepnek G.H. Death or debt? National estimates of financial toxicity in persons with newly-diagnosed cancer. Am J Med. 2018;131(10):1187–1199.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.So S.C.Y., Ng D.W.L., Liao Q., Fielding R., Soong I., Chan K.K.L., et al. Return to work and work productivity during the first year after cancer treatment. Front Psychol. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.866346. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.866346/full Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan R., Lewison G., Torode J., Kingham P.T., Brennan M., Shulman L.N., et al. Cancer research collaboration between the UK and the USA: reflections on the 2021 G20 Summit announcement. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(4):460–462. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sohn K.J., Park S.Y., Kim S. A scoping review of return to work decision-making and experiences of breast cancer survivors in Korea. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):1741–1751. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mujahid M.S., Janz N.K., Hawley S.T., Griggs J.J., Hamilton A.S., Katz S.J. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(1):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancer survivors and return to work: current knowledge and future research - duijts - 2017 - psycho-Oncology - wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.4235. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C.M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Short P.F., Vasey J.J., Tunceli K. Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1292–1301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley C.J., Oberst K., Schenk M. Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2006;15(8):739–747. doi: 10.1002/pon.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pryce J., Munir F., Haslam C. Cancer survivorship and work: symptoms, supervisor response, co-worker disclosure and work adjustment. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s10926-006-9040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnsson A., Fornander T., Rutqvist L.E., Vaez M., Alexanderson K., Olsson M. Predictors of return to work ten months after primary breast cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):93–98. doi: 10.1080/02841860802477899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mols F., Thong M.S.Y., Vreugdenhil G., van de Poll-Franse L.V. Long-term cancer survivors experience work changes after diagnosis: results of a population-based study. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1252–1260. doi: 10.1002/pon.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fantoni S.Q., Peugniez C., Duhamel A., Skrzypczak J., Frimat P., Leroyer A. Factors related to return to work by women with breast cancer in northern France. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):49–58. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gudbergsson S.B., Torp S., Fløtten T., Fosså S.D., Nielsen R., Dahl A.A. A comparative study of cancer patients with short and long sick-leave after primary treatment. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(3):381–389. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.500298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petersson L.M., Wennman-Larsen A., Nilsson M., Olsson M., Alexanderson K. Work situation and sickness absence in the initial period after breast cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):282–288. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.533191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roelen C.A., Koopmans P.C., Groothoff J.W., van der Klink J.J., Bültmann U. Sickness absence and full return to work after cancer: 2-year follow-up of register data for different cancer sites. Psychooncology. 2011;20(9):1001–1006. doi: 10.1002/pon.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roelen C.A.M., Koopmans P.C., Groothoff J.W., van der Klink J.J.L., Bültmann U. Return to work after cancer diagnosed in 2002, 2005 and 2008. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(3):335–341. doi: 10.1007/s10926-011-9319-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp L., Timmons A. Social welfare and legal constraints associated with work among breast and prostate cancer survivors: experiences from Ireland. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):382–394. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torp S., Gudbergsson S.B., Dahl A.A., Fosså S.D., Fløtten T. Social support at work and work changes among cancer survivors in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(6 Suppl):33–42. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nachreiner N.M., Ghebre R.G., Virnig B.A., Shanley R. Early work patterns for gynaecological cancer survivors in the USA. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62(1):23–28. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torp S., Nielsen R.A., Gudbergsson S.B., Fosså S.D., Dahl A.A. Sick leave patterns among 5-year cancer survivors: a registry-based retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horsboel T.A., Nielsen C.V., Nielsen B., Jensen C., Andersen N.T., de Thurah A. Type of hematological malignancy is crucial for the return to work prognosis: a register-based cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(4):614–623. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luker K., Campbell M., Amir Z., Davies L. A UK survey of the impact of cancer on employment. Occup Med (Lond) 2013;63(7):494–500. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqt104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noeres D., Park-Simon T.W., Grabow J., Sperlich S., Koch-Gießelmann H., Jaunzeme J., et al. Return to work after treatment for primary breast cancer over a 6-year period: results from a prospective study comparing patients with the general population. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(7):1901–1909. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1739-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamminga S.J., Verbeek J.H.A.M., Bos M.M.E.M., Fons G., Kitzen J.J.E.M., Plaisier P.W., et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-based work support intervention for female cancer patients - a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goss C., Leverment I.M.G., de Bono A.M. Breast cancer and work outcomes in health care workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2014;64(8):635–637. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hauglann B.K., Saltytė Benth J., Fosså S.D., Tveit K.M., Dahl A.A. A controlled cohort study of sickness absence and disability pension in colorectal cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(6):735–743. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.844354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee M.K., Yun Y.H. Working situation of cancer survivors versus the general population. J Cancer Surviv. giugno 2015;9(2):349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray K., Lam K.B.H., McLoughlin D.C., Sadhra S.S. Predictors of return to work in cancer survivors in the Royal Air Force. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L., Glimelius I., Neovius M., Ekberg S., Martling A., Eloranta S., et al. Work loss duration and predictors following rectal cancer treatment among patients with and without prediagnostic work loss. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(6):987–994. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Endo M., Haruyama Y., Takahashi M., Nishiura C., Kojimahara N., Yamaguchi N. Returning to work after sick leave due to cancer: a 365-day cohort study of Japanese cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(2):320–329. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agarwal J., Krishnatry R., Chaturvedi P., Ghosh-Laskar S., Gupta T., Budrukkar A., et al. Survey of return to work of head and neck cancer survivors: a report from a tertiary cancer center in India. Head Neck. 2017;39(5):893–899. doi: 10.1002/hed.24703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee M.K., Kang H.S., Lee K.S., Lee E.S. Three-year prospective cohort study of factors associated with return to work after breast cancer diagnosis. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(4):547–558. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ullrich A., Rath H.M., Otto U., Kerschgens C., Raida M., Hagen-Aukamp C., et al. Outcomes across the return-to-work process in PC survivors attending a rehabilitation measure-results from a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3007–3015. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3790-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Egmond M.P., Duijts S.F.A., van Muijen P., van der Beek A.J., Anema J.R. Therapeutic work as a facilitator for return to paid work in cancer survivors. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(1):148–155. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9641-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arfi A., Baffert S., Soilly A.L., Huchon C., Reyal F., Asselain B., et al. Determinants of return at work of breast cancer patients: results from the OPTISOINS01 French prospective study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartung T.J., Sautier L.P., Scherwath A., Sturm K., Kröger N., Koch U., et al. Return to work in patients with hematological cancers 1 Year after treatment: a prospective longitudinal study. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41(11):697–701. doi: 10.1159/000491589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heuser C., Halbach S., Kowalski C., Enders A., Pfaff H., Ernstmann N. Sociodemographic and disease-related determinants of return to work among women with breast cancer: a German longitudinal cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1000. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3768-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Musti M.A., Collina N., Stivanello E., Bonfiglioli R., Giordani S., Morelli C., et al. Perceived work ability at return to work in women treated for breast cancer: a questionnaire-based study. Med Lav. 2018;109(6):407–419. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v110i6.7241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petersson L.M., Vaez M., Nilsson M.I., Saboonchi F., Alexanderson K., Olsson M., et al. Sickness absence following breast cancer surgery: a two-year follow-up cohort study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(2):715–724. doi: 10.1111/scs.12502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ullrich A., Rath H.M., Otto U., Kerschgens C., Raida M., Hagen-Aukamp C., et al. Return to work in prostate cancer survivors - findings from a prospective study on occupational reintegration following a cancer rehabilitation program. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):751. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4614-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arndt V., Koch-Gallenkamp L., Bertram H., Eberle A., Holleczek B., Pritzkuleit R., et al. Return to work after cancer. A multi-regional population-based study from Germany. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):811–818. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1557341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee A., Lee J.E. Factors related to employment situation among Korean cancer survivors: results from a population-based study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(1):33–40. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmidt M.E., Scherer S., Wiskemann J., Steindorf K. Return to work after breast cancer: the role of treatment-related side effects and potential impact on quality of life. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2019;28(4) doi: 10.1111/ecc.13051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tamminga S.J., Coenen P., Paalman C., de Boer A.G.E.M., Aaronson N.K., Oldenburg H.S.A., et al. Factors associated with an adverse work outcome in breast cancer survivors 5-10 years after diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(1):108–116. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewis J., Mackenzie L., Black D. Workforce participation of Australian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2020;29(7):1156–1164. doi: 10.1002/pon.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paltrinieri S., Vicentini M., Mazzini E., Ricchi E., Fugazzaro S., Mancuso P., et al. Factors influencing return to work of cancer survivors: a population-based study in Italy. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2):701–712. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vayr F., Montastruc M., Savall F., Despas F., Judic E., Basso M., et al. Work adjustments and employment among breast cancer survivors: a French prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(1):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04799-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bellagamba G., Descamps A., Cypowyj C., Eisinger F., Villa A., Lehucher-Michel M.P. Cancer survivors’ efforts to facilitate return to work. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(7):845–852. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1795212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brusletto B., Nielsen R.A., Engan H., Oldervoll L., Ihlebæk C.M., Mjøsund N.H., et al. Labor-force participation and working patterns among women and men who have survived cancer: a descriptive 9-year longitudinal cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2021;49(2):188–196. doi: 10.1177/1403494820953330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rashid H., Eichler M., Hechtner M., Gianicolo E., Wehler B., Buhl R., et al. Returning to work in lung cancer survivors-a multi-center cross-sectional study in Germany. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(7):3753–3765. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05886-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stapelfeldt C.M., Momsen A.M.H., Jensen A.B., Andersen N.T., Nielsen C.V. Municipal return to work management in cancer survivors: a controlled intervention study. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(3):370–378. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1853227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zaman A.C.G.N.M., Tytgat K.M.A.J., Klinkenbijl J.H.G., Boer FC den, Brink M.A., Brinkhuis J.C., et al. Effectiveness of a tailored work-related support intervention for patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(2):323–338. doi: 10.1007/s10926-020-09920-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kollerup A., Ladenburg J., Heinesen E., Kolodziejczyk C. The importance of workplace accommodation for cancer survivors - the role of flexible work schedules and psychological help in returning to work. Econ Hum Biol. 2021;43 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paltrinieri S., Vicentini M., Mancuso P., Mazzini E., Fugazzaro S., Rossi P.G., et al. Return to work of Italian cancer survivors: a focus on prognostic work-related factors. Work. 2022;71(3):681–691. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Juul S.J., Rossetti S., Kicinski M., van der Kaaij M.A.E., Giusti F., Meijnders P., et al. Employment situation among long-term Hodgkin lymphoma survivors in Europe: an analysis of patients from nine consecutive EORTC-LYSA trials. J Cancer Surviv. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01305-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rai R, Malik M, Valiyaveettil D, Ahmed SF, Basalatullah M. Assessment of late treatment-related symptoms using patient-reported outcomes and various factors affecting return to work in survivors of breast cancer [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: http://staging.ecancer.org/en/journal/article/1533-assessment-of-late-treatment-related-symptoms-using-patient-reported-outcomes-and-various-factors-affecting-return-to-work-in-survivors-of-breast-cancer/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Baum J., Lax H., Lehmann N., Merkel-Jens A., Beelen D.W., Jöckel K.H., et al. Impairment of vocational activities and financial problems are frequent among German blood cancer survivors. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50289-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsai P.L., Wang C.P., Fang Y.Y., Chen Y.J., Chen S.C., Chen M.R., et al. Return to work in head and neck cancer survivors: its relationship with functional, psychological, and disease-treatment factors. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17(6):1715–1724. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01224-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boer AG de, Taskila TK, Tamminga SJ, Frings-Dresen MH, Feuerstein M, Verbeek JH. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients - de Boer, AGEM - 2011 Cochrane Liy. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub2/full. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.de Boer A.G.E.M., Taskila T.K., Tamminga S.J., Feuerstein M., Frings-Dresen M.H.W., Verbeek J.H. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(9):CD007569. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spelten E.R., Sprangers M.A.G., Verbeek J.H.A.M. Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pon.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tavan H., Azadi A., Veisani Y. Return to work in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25(1):147–152. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_114_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Islam T., Dahlui M., Majid H.A., Nahar A.M., Mohd Taib N.A., Su T.T., et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(Suppl. 3):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8. Suppl 3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van Muijen P., Weevers N.L.E.C., Snels I.a.K., Duijts S.F.A., Bruinvels D.J., Schellart A.J.M., et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22(2):144–160. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cocchiara R.A., Sciarra I., D’Egidio V., Sestili C., Mancino M., Backhaus I., et al. Returning to work after breast cancer: a systematic review of reviews. Work. 2018;61(3):463–476. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McQueen J., McFeely G. Case management for return to work for individuals living with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24(5):203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 93.den Bakker C.M., Anema J.R., Zaman A.G.N.M., de Vet H.C.W., Sharp L., Angenete E., et al. Prognostic factors for return to work and work disability among colorectal cancer survivors; A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tamminga S.J., de Boer A.G.E.M., Verbeek JH.a.M., Frings-Dresen M.H.W. Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(9):639–648. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.