Abstract

Brome mosaic virus (BMV), a positive-strand RNA virus in the alphavirus-like superfamily, encodes two RNA replication factors. Membrane-associated 1a protein contains a helicase-like domain and RNA capping functions. 2a, which is targeted to membranes by 1a, contains a central polymerase-like domain. In the absence of 2a and RNA replication, 1a acts through an intergenic replication signal in BMV genomic RNA3 to stabilize RNA3 and induce RNA3 to associate with cellular membrane. Multiple results imply that 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization reflects interactions involved in recruiting RNA3 templates into replication. To determine if 1a had similar effects on another BMV RNA replication template, we constructed a plasmid expressing BMV genomic RNA2 in vivo. In vivo-expressed RNA2 templates were replicated upon expression of 1a and 2a. In the absence of 2a, 1a stabilized RNA2 and induced RNA2 to associate with membrane. Deletion analysis demonstrated that 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2 was mediated by sequences in the 5′-proximal third of RNA2. The RNA2 5′ untranslated region was sufficient to confer 1a-induced membrane association on a nonviral RNA. However, sequences in the N-terminal region of the 2a open reading frame enhanced 1a responsiveness of RNA2 and a chimeric RNA. A 5′-terminal RNA2 stem-loop important for RNA2 replication was essential for 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2 and, like the 1a-responsive RNA3 intergenic region, contained a required box B motif corresponding to the TΨC stem-loop of host tRNAs. The level of 1a-induced membrane association of various RNA2 mutants correlated well with their abilities to serve as replication templates. These results support and expand the conclusion that 1a-induced BMV RNA stabilization and membrane association reflect early, 1a-mediated steps in viral RNA replication.

During infection, the genomic RNAs of positive-strand RNA viruses first must be translated to generate RNA replication factor(s) and other proteins and then must serve as templates for negative-strand RNA synthesis. One complication of these dual template functions is the ability of 5′-to-3′ processive ribosomes to block negative-strand RNA synthesis by 3′-to-5′ processive polymerase (11, 20). Therefore, positive-strand RNA viruses must have evolved mechanisms to regulate the alternate template functions of genomic RNA, including mechanisms to clear ribosomes from the RNA and allow transfer of the RNA template from translation to RNA replication (20, 25).

Brome mosaic virus (BMV), a member of the alphavirus-like superfamily of positive-strand RNA viruses, has three genomic RNAs with 5′ caps and tRNA-like 3′ ends (1, 51). RNA1 and RNA2 encode nonstructural proteins 1a and 2a, respectively, which direct RNA replication and contain domains conserved with other superfamily members (4, 19, 25). 1a contains an N-terminal domain with m7G methyltransferase and covalent GTP binding activities implicated in viral RNA capping (3, 30) and a C-terminal domain with all motifs of DEAD box RNA helicases (22). The central portion of 2a is similar to that of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (9). 1a localizes to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes in the absence of other viral factors (47). 2a is distributed throughout the cytoplasm when expressed alone but localizes to ER membranes by interacting with 1a (14). The ER sites where 1a and 2a colocalize are the sites of BMV RNA synthesis (46, 47).

RNA3 encodes the 3a cell-to-cell movement protein and the coat protein. Both are required for systemic infection of BMV's natural plant hosts but are dispensable for RNA replication (5, 36, 48). The 3′ proximal coat gene is translated from a subgenomic mRNA, RNA4, produced from the negative-strand RNA3 replication intermediate. RNA3 replication and subgenomic RNA synthesis depend on cis-acting signals in the RNA3 5′, 3′, and intergenic untranslated regions (UTRs) (17, 18, 32, 35). The intergenic region contains two overlapping cis signals: the subgenomic mRNA promoter (17) and an approximately 150-nucleotide (nt) replication enhancer, whose deletion reduces RNA3 negative-strand synthesis and replication in vivo approximately 100-fold (18, 44).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing BMV 1a and 2a, RNA3 is replicated and synthesizes subgenomic RNA4, reproducing all known features of RNA3 replication in plant cells (24, 25, 44, 47, 50). In yeast expressing RNA3 and 1a but not 2a, RNA3 is not replicated but its stability and accumulation increase dramatically (25, 50). Multiple observations imply that 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization reflects interactions involved in recruiting RNA3 from translation to RNA replication. Although 1a increases RNA3 stability and accumulation, the additional RNA3 is translated poorly if at all (25). Indeed, increased RNA3 stability may be a consequence of the 1a-induced inhibition of RNA3 translation, since many mRNAs are stabilized by inhibiting translation (40). 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization depends on the intergenic replication enhancer required for negative-strand synthesis in plant and yeast cells (50). Partial deletions in the enhancer cause parallel decreases or increases in 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization and 1a- and 2a-dependent negative- and positive-strand RNA3 production (50). Moreover, genetic exchanges show that 1a and the intergenic replication enhancer are the major trans and cis determinants of template specificity in BMV RNA3 replication (39, 53). The RNA3 replication enhancer contains a box B motif that is conserved with the TΨC loop of tRNAs and is essential for both 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization and RNA3 replication (33, 50). Highly conserved box B motifs are also found in the 5′ UTRs of BMV RNA1 and RNA2 (33, 34).

If, as these findings imply, 1a-induced RNA3 stabilization is related to selecting RNA3 templates for replication rather than translation, similar interactions might occur with the other BMV RNA replication templates, genomic RNA1 and RNA2. To further test this model and the roles of 1a in RNA replication, we have explored the interaction of 1a and RNA2. Here we show that BMV RNA2 is also replicated in yeast upon expression of 1a and 2a and that 1a stabilizes RNA2 in vivo independently of 2a and RNA replication. We also have identified RNA2 cis-acting sequences required for 1a responsiveness, shown that these 5′ proximal sequences are sufficient to make a nonviral RNA 1a responsive and found that these sequences also are required for RNA2 replication. As for RNA3, 1a responsiveness of RNA2 depends on a conserved box B motif and flanking sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strain and cell growth.

Yeast strain YPH500 (MATα ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1) was used throughout. Yeast cultures were grown at 30°C in defined synthetic medium containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose as indicated and lacking relevant amino acids to maintain selection for any DNA plasmids presents (10).

Plasmids and plasmid constructions.

Standard procedures were used for all DNA manipulations (49). DNA fragments generated by PCR were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the overall structures of all plasmids were confirmed by restriction analysis. Laboratory designations for plasmids are given in parentheses if different from plasmid names used in this report.

BMV 1a was expressed from pB1CT19 (26), a 2μm plasmid containing the HIS3 selectable marker gene and 1a open reading frame (ORF) flanked by the yeast ADH1 promoter and ADH1 polyadenylation site. In some experiments, BMV 2a was supplied in trans from pB2YT1 (generously provided by M. Ishikawa), a derivative of centromeric plasmid Ycplac22 (21) containing the TRP1 selectable marker and 2a ORF flanked by the yeast GAL1 promoter and ADH1 polyadenylation site. BMV RNA3 was expressed from pB3RQ39 (24), a centromeric plasmid containing the TRP1 selectable marker and an RNA3 cDNA flanked by the GAL1 promoter and a self-cleaving hepatitis delta virus ribozyme.

RNA2 was expressed from pB2 (pB2NR3), a centromeric plasmid containing the LEU2 selectable marker and a full-length RNA2 cDNA flanked by the yeast GAL1 promoter and a self-cleaving hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. To construct pB2, RNA2 nt 1 to 884 were amplified by PCR from pB2TP5 (27), using a 5′ primer that fused TAAAGTAC to the 5′ end of RNA2 cDNA (GTA …), creating a SnaBI site (TACGTA). The SnaBI-PflMI fragment from the PCR product and the PflMI-BsmI fragment from pB2TP5 were used collectively to replace the SnaBI-BsmI RNA3 region in pB3RQ39, thus fusing the GAL1 promoter, RNA2 cDNA, and ribozyme. In the resulting plasmid, pB2NR2, a portion of the 200-nt, tRNA-like 3′ end conserved on all BMV genomic RNAs was derived from RNA3. This region contained a single nucleotide substitution from RNA2, but this substitution has no effect on RNA2 replication (45). To obtain the promoter-cDNA-ribozyme cassette in a plasmid with the LEU2 selectable marker, the EcoRI-PstI fragment of pB2NR2 then was transferred to Ycplac111 (21), yielding pB2.

pB2ΔGDD (pB2NR3ΔGDD) is a pB2 derivative with RNA2 nt 1772 to 1780 deleted by two-step PCR (57). pB2fs1 (pB2NR3-M1) and pB2fs2 (pB2NR3-M2) are pB2 derivatives with 2- and 4-nt insertions, respectively, at nt 113 and 886. To make pB2fs1, pB2NR2 was digested with BstBI, blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase, and religated to yield pB2NR2-M1. The EcoRI-NcoI fragment in pB2 was replaced with the corresponding fragment from pB2NR2-M1 to generate pB2fs1. pB2fs2 was made by digesting pB2 with NcoI, blunt ending with T4 DNA polymerase, and religating.

pB2Δ5′ (pB2NR3-D1), pB2ΔM (pB2NR3-D3), and pB2Δ3′ (pB2NR3-D4) are the SnaBI-NcoI, NcoI-MluI, and MluI-BsmI, respectively, deletion derivatives of pB2.

pB2Δ5′-3 (pB2NR3-D20) and pB2Δ5′-4 (pB2NR3-D21) were made by PCR amplification of RNA2 fragments corresponding to nt 175 to 890 and 334 to 890, respectively. The 5′ PCR primers fused GATCTTCGAA, containing a BstBI site (underlined), to nt 175 or 334 at the 5′ end. The PCR products were digested with BstBI and NcoI and used to replace the equivalent BstBI-NcoI fragment in pB2. pB2Δ5′-5 (pB2NR3-D14) was made by PCR amplification of RNA2 fragments corresponding to nt 407 to 890 with the BstBI site-containing sequence GATCTTCGAAA added to the 5′ end. The PCR products were digested with BstBI and NcoI and used to replace the equivalent BstBI-NcoI fragment in pB2. Similarly, pB2Δ5′-6 (pB2NR3-D23), pB2Δ5′-7 (pB2NR3-D24), and pB2Δ5′-8 (pB2NR3-D25) were constructed by PCR amplification of RNA2 fragments corresponding to nt 104 to 761, 104 to 641, and 104 to 521, respectively, with the NcoI site-containing sequence CCATGGCTAG fused to nt 761, 641, and 521, respectively, at the 3′ end. The PCR products were digested with BstBI and NcoI and used to replace the equivalent BstBI-NcoI fragment in pB2.

pB2Δ5′-9 (pB2NR3-D7) contains the deletion previously characterized in pB2PT70 (54). The PflMI-MluI fragment from pB2PT70, encompassing this deletion, was subcloned and used to replace the corresponding fragment in pB2NR2 to yield pB2NR2-D5. The EcoRI-PstI fragment of pB2NR2-D5 was then transferred to Ycplac111 to generate pB2Δ5′-9. To make pB2Δ5′-10 (pB2NR3-D6), pB2NR2 was digested with PflMI and NcoI, blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase, and religated to generate pB2NR2-D4. The EcoRI-PstI fragment in pB2NR2-D4 was then transferred to Ycplac111 to generate pB2Δ5′-10.

Deletion and base substitution mutants pB2Δ5′-1 (pB2NR3ΔSL1), pB2Δ5′-2 (pAON43), pB2SL1 (pAON50), pB2SL2 (pAON39), pB2SL3 (pAON51), pB2SL4 (pAON38), pB2SL5 (pAON36), and pB2SL6 (pAON37) were made by PCR using 5′ primers extending from the first nucleotide of RNA2 through and beyond the desired mutations and a common 3′ primer complementary to RNA2 sequences 871 to 890. PCR products containing the desired mutations then were digested with NcoI and used to replace the SnaBI-NcoI fragment in pB2.

pB2glo1 (pB2JC1) was made by replacing the NcoI (blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase)-BamHI fragment in pB2 with a PstI (blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase)-BamHI fragment from pMS99 (50) containing a human β-globin ORF and ADH1 polyadenylation site. To make pB2glo2 (pB2JC1-3), pMS99 was digested with BamHI and HindIII, blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase, and religated to remove a small fragment containing a PstI site downstream of the ADH1 polyadenylation site to generate pMS99J. PCR then was performed using pB2 as the template to amplify a fragment corresponding to the GAL1 promoter and RNA2 5′ UTR sequences. EcoRI sequences were engineered at the 5′ end directly upstream of the GAL1 promoter, and PstI sequences were engineered at the 3′ end immediately downstream of RNA2 5′ UTR sequences. This PCR-generated fragment was digested with EcoRI and PstI and used to replace the EcoRI-PstI fragment in pMS99J to yield pB2glo2. pB2glo3 (pB2JC1-9) was made by replacing the EcoRI-PstI fragment in pB2glo2 with a corresponding PCR fragment generated from a pB2SL1 template.

RNA and protein analysis.

RNA decay assays, total yeast RNA isolation, Northern blot analysis, two-cycle RNase protection assays, primer extension, total protein extraction, and Western blot analysis were performed as described elsewhere (14, 24, 38, 50). For cell fractionation, yeast cells were grown in synthetic galactose medium to mid-log phase and converted to spheroplasts as described elsewhere (14). Spheroplasts were osmotically lysed by pipetting up and down in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 10 mM ribonucleoside vanadyl complex). The resulting lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was removed and retained, and the pellet was washed once with extraction buffer and resuspended to original lysate volume in extraction buffer. Nucleic acids were isolated from these fractions by phenol-chloroform extraction and analyzed by Northern blotting.

RESULTS

1a- and 2a-dependent RNA2 replication in yeast.

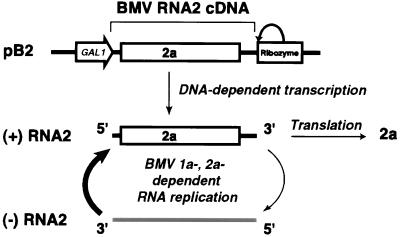

To test whether yeast would support BMV RNA2 replication, we constructed pB2 (Fig. 1), a yeast centromeric plasmid containing a full-length RNA2 cDNA. The 5′ end of RNA2 cDNA was linked to the galactose-inducible, glucose-repressible yeast GAL1 promoter, and the 3′ end was linked to a self-cleaving hepatitis delta virus ribozyme to generate RNA2 transcripts with the authentic RNA2 3′ end (24).

FIG. 1.

Pathway for initiating BMV RNA2 replication from DNA plasmid pB2. The bracket at the top indicates the RNA2 cDNA copy within pB2, with the 2a ORF boxed. The yeast GAL1 promoter fused to 5′ end of RNA2 cDNA allows galactose-inducible, glucose-repressible transcription of RNA2, and the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme cleaves the transcripts at the natural 3′ end of RNA2 as indicated. RNA2 transcripts serve as templates for translation of 2a protein and for synthesis of the negative-strand RNA2 replication intermediate.

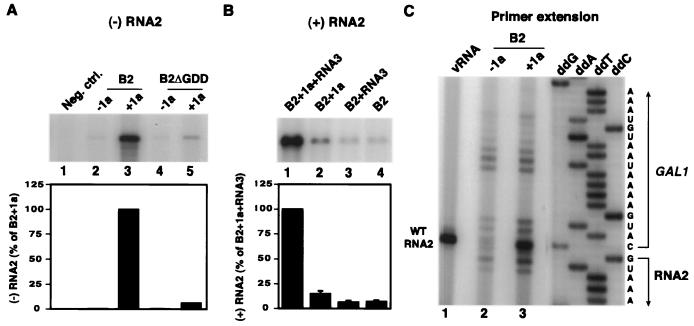

pB2 was introduced into yeast alone or with a plasmid expressing BMV RNA replication factor 1a. To assay for possible negative-strand RNA2 synthesis, total RNA extracted from yeast cells was hybridized with a 32P-labeled RNA probe complementary to 245 nt in the center of negative-strand RNA2 and treated with single-strand-specific RNases A and T1. This RNase protection assay produced a strong negative-strand signal in yeast coexpressing wt RNA2 and 1a (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Negative-strand RNA2 accumulation was suppressed by omitting 1a or mutating 2a. In yeast containing pB2 but lacking 1a, the background signal in this assay was only 1 to 2% of that in the presence of 1a (Fig. 2A, lane 2). This background signal was not reduced by mutating RNA2 to delete the 2a protein GDD residues (lane 4) that constitute the most conserved functional motif in RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (9, 29). Thus, the background signal resulted from 1a-, 2a-independent mechanisms such as cryptic promoter-initiated transcription of the pB2 RNA2 cDNA in the direction opposite to GAL1-promoted transcription. In 1a-expressing yeast, deleting the conserved 2a GDD motif reduced negative-strand RNA levels 15-fold (Fig. 2A, lane 5), showing that high-level RNA2 negative-strand production was 1a and 2a dependent. Nevertheless, even for yeast expressing RNA2 with the ΔGDD mutation, 1a produced a small increase in negative-strand RNA2 levels (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5). This might reflect low-level residual activity in the 2a ΔGDD mutant, low-level nonspecific effects of 1a on all RNAs (50), or both.

FIG. 2.

RNA2 replication in yeast. (A) Negative-strand RNA2 accumulation was assayed by a two-cycle RNase protection assay (38) using equal amounts of total RNA extracted from yeast expressing no BMV components (lane 1) or yeast expressing wt RNA2 (B2) or an RNA2 mutant with a deletion of the conserved GDD polymerase motif (B2ΔGDD), in the presence (+1a) or absence (−1a) of 1a as indicated. After initial hybridization and RNase treatment to remove excess positive-strand RNA2, the remaining double-stranded RNA was denatured, hybridized with a 32P-labeled RNA probe corresponding to nt 1441 to 1685 of positive-strand RNA2, and treated with RNases A and T1. The reaction products were electrophoresed and autoradiographed. Parallel strand-specific Northern blot analysis produced similar negative-strand RNA2 accumulation results, but with higher background signals apparently due to cross-hybridization. Neg. ctrl., negative control. (B) Positive-strand RNA2 accumulation in yeast expressing RNA2 alone, with 1a, with RNA3, or with both, as indicated. Total RNA was isolated from yeast and analyzed by Northern blotting with a probe specific for positive-strand RNA2. (C) Primer extension analysis of 5′ ends of RNA2 species in yeast expressing wt RNA2 with or without 1a. A 5′ 32P-labeled primer complementary to nt 47 to 73 of RNA2 was annealed with BMV virion RNA (vRNA) or total RNA from the indicated yeast. The primer was extended with reverse transcriptase, and the resulting cDNA products were analyzed in a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. A sequencing ladder prepared by extending the same labeled primer on pB2 plasmid DNA was coelectrophoresed, and sequence corresponding to the sense of the RNA product is shown at right. As previously demonstrated, the major primer extension bands from BMV positive-strand RNA replication products migrate one nucleotide above the end of the viral sequence due to cap-dependent incorporation of an additional nucleotide (2, 6).

Next, we compared positive-strand RNA2 accumulation in yeast expressing RNA2 by itself, with 1a, with BMV RNA3, or with both. Coexpressing RNA3 alone did not affect the accumulation of positive-stand RNA2 transcripts (Fig. 2B, lane 3 and 4). However, coexpressing 1a increased positive-stand RNA2 accumulation twofold over that produced by DNA transcription from the strong GAL1 promoter in pB2 (Fig. 2B, lane 2 versus lane 4). Coexpressing 1a and RNA3 increased positive-strand RNA2 accumulation 18-fold (Fig. 2B, lane 1). This is consistent with prior findings that BMV coat protein, which is produced by subgenomic mRNA synthesis in yeast expressing 1a, 2a, and RNA3, encapsidates and stabilizes RNA2 in yeast (31). Negative-strand RNA2 levels were unaffected by the presence or absence of RNA3, implying that RNA3 did not stimulate RNA2 replication.

In the absence of RNA3 and coat protein, the increased RNA2 accumulation in yeast coexpressing 1a could result from 1a-induced stabilization of DNA-derived RNA2 transcripts (see also below), from RNA-dependent RNA2 replication, or from both. To explore these possibilities, we used primer extension to examine the 5′ ends of RNA2 species in yeast expressing wild-type (wt) RNA2 alone or with 1a (Fig. 2C). Primer extension was used based on prior findings that GAL1-driven transcription starts at multiple sites, that 1a equally stabilizes RNA3 transcripts from all start sites, but that 1a- and 2a-driven, RNA-dependent RNA3 replication specifically amplifies RNA3 species with natural viral 5′ ends (24, 25).

As expected, GAL1-promoted RNA2 transcripts in yeast lacking 1a exhibited multiple 5′ ends (Fig. 2C, lane 2) (24, 28). Upon coexpression of 1a, we observed the same RNA2 species but overlaid with the intense, selective amplification of a single band corresponding to the 5′ end of natural BMV RNA2 replication products (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 3). Thus, RNA replication contributed substantially to increased RNA2 accumulation in the presence of 1a. Results presented below show that RNA2 replicated to even higher levels when higher levels of 2a were supplied in trans from a 2a mRNA unable to serve as a replication template.

1a stabilizes RNA2 and induces RNA2 association with membrane.

In the absence of 2a and RNA replication, 1a increases the stability and accumulation of DNA-derived RNA3 transcripts (25, 50). To determine if 1a similarly stabilized RNA2, we measured RNA2 decay with and without 1a by repressing the GAL1 promoter with glucose and monitoring surviving RNA2 levels by Northern blotting.

In the absence of 1a, RNA2 decayed rapidly, with an initial half-life of approximately 7 min (Fig. 3A). Decay slowed after 70% or more of the initial RNA2 had decayed. Similar biphasic decay patterns have been seen for BMV RNA3 and other RNAs containing the BMV tRNA-like 3′ end (50). In the presence of 1a, the level of surviving RNA2 was much higher for all time points after glucose repression. Sixty minutes after glucose repression, e.g., approximately 50% of the initial RNA2 survived in the presence of 1a, compared to less than 10% in the absence of 1a.

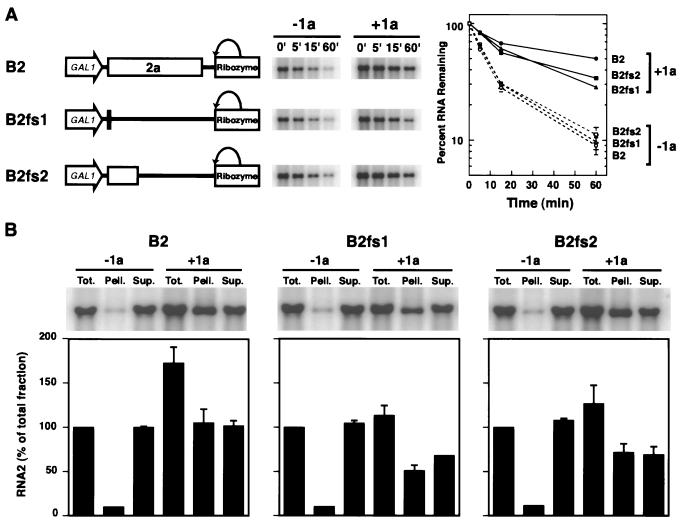

FIG. 3.

1a-induced stabilization and membrane association of wt RNA2 and RNA2 frameshift mutants. (A) On the left are diagrams of expression cassettes for wt RNA2, B2fs1, and B2fs2. In B2fs1, a 2-nt insertion after nt 110 results in translation of 3 wt 2a codons followed by 18 out-of-frame codons. In B2fs2, a 4-nt insertion after nt 882 results in translation of 261 wt 2a codons followed by 3 out-of-frame codons. The stabilities of these RNAs in the absence (−1a) and presence (+1a) of 1a were analyzed by transferring galactose-induced yeast to glucose to repress GALI-promoted RNA2 transcription. Equal amounts of total RNA prepared from yeast harvested at the indicated times following glucose repression were analyzed by Northern blotting to detect positive-strand RNA2 (middle). The results of three or more independent stability analyses of each RNA were averaged and plotted on a logarithmic scale (right). Standard error bars are included on all points but in some cases are obscured by the symbols used to plot the average values. (B) Effects of 1a on distribution of wt RNA2, B2fs1, and B2fs2 in cell fractionation. Yeast cells expressing these RNAs with or without 1a were spheroplasted and lysed osmotically to yield a total RNA fraction (Tot.). A portion of the lysate was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g to yield pellet (Pell.) and supernatant (Sup.) fractions. RNA was isolated from each fraction by phenol-chloroform extraction, and equal percentages of each fraction were analyzed by Northern blotting to detect positive-strand RNA2. For each RNA, the accumulation in each fraction was normalized to that in the total fraction for that RNA in the absence of 1a. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments were plotted.

Since wt RNA2 expressing 2a can replicate in yeast coexpressing 1a (Fig. 2), the higher RNA2 levels in the presence of 1a could be due to RNA2 replication, to increased RNA2 stability, or to both. To distinguish among these possibilities, we created two pB2 derivatives with frameshift mutations in the 2a gene (Fig. 3A). pB2fs1 bore a 2-nt insertion at RNA2 position 110, resulting in translation of 3 wt 2a codons followed by 18 out-of-frame codons. pB2fs2 bore a 4-nt insertion at RNA2 position 882, resulting in translation of 261 wt 2a codons followed by 3 out-of-frame codons. Western blotting with anti-2a antibodies showed that, as expected, yeast expressing B2fs1 RNA contained no detectable 2a-related peptide, while yeast expressing B2fs2 RNA contained a truncated 2a peptide of the predicted size (data not shown).

RNA2 decay assays showed that in the absence of 1a, B2fs1 and B2fs2 RNA decayed rapidly, with kinetics indistinguishable from those of wt RNA2 in the absence of 1a (Fig. 3A). In the presence of 1a, the levels of B2fs1 and B2fs2 RNA surviving after glucose repression were dramatically increased. Nevertheless, consistent with the ability of wt RNA2 to replicate in a 2a-dependent manner (Fig. 2), the levels of B2fs1 and B2fs2 RNA after glucose repression were lower than that of wt RNA2 (Fig. 3A). The results imply that in the absence of functional 2a protein and RNA2 replication, 1a increased the stability of DNA-derived transcripts of the B2fs1 and B2fs2 RNA2 derivatives, but that for wt RNA2, RNA replication also contributed to the 1a-dependent increase in RNA2 levels after glucose repression.

In plant and yeast cells, cell fractionation and confocal microscopy show that BMV RNA replication factors 1a and 2a and BMV RNA-dependent RNA synthesis colocalize on ER membranes (14, 46, 47). In the presence or absence of other viral factors, 1a localizes to ER membranes and remains membrane-associated upon cell fractionation (14, 47). In keeping with these findings, recent results show that 1a-dependent stabilization of RNA3 results in membrane association of RNA3 (M. Janda, M. Sullivan, and P. Ahlquist, unpublished results). To determine if 1a also induces RNA2 to associate with membranes, yeast expressing wt RNA2 in the presence or absence of 1a were spheroplasted, lysed, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g to produce soluble supernatant and membrane-associated pellet fractions, and the level of RNA2 in each fraction was determined by Northern blotting.

As shown in Fig. 3B, in the absence of 1a, nearly all wt RNA2 was found in the supernatant. When 1a was coexpressed, the level of RNA2 increased, and half of all RNA2 was found in the membrane-associated pellet. RNA2 mutants B2fs1 and B2fs2 showed similar behavior (Fig. 3B): without 1a, nearly all of the RNA was in the supernatant fraction, while 1a coexpression induced approximately half of the total RNA2 to associate with the membrane fraction. Thus, independently of 2a and RNA replication, the ER membrane-associated 1a protein stabilized RNA2 and induced RNA2 to associate with the pelletable membrane fraction. Because membrane association provided a more direct and easily quantified measure of 1a effects on RNA2 than the RNA decay assay, it was used in subsequent experiments.

The 5′ third of RNA2 is required for 1a-induced membrane association.

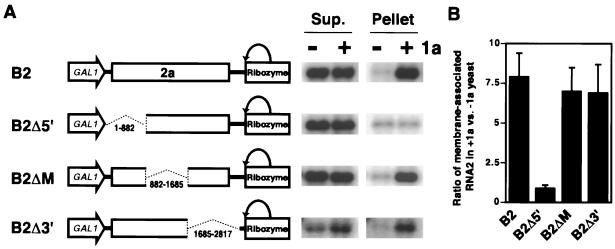

To identify the RNA2 cis signals required for 1a-induced membrane association, we created nonoverlapping deletion derivatives B2Δ5′, B2ΔM, and B2Δ3′, collectively spanning almost the complete RNA2 sequence, and tested their abilities to associate with membrane in the presence of 1a. In the absence of 1a, all three deletion derivatives were primarily found in the supernatant fraction, similar to wt RNA2 (Fig. 4). B2Δ3′, which lacked RNA2 nt 1685 to 2817 but retained the 3′ 48 nt, showed this same distribution pattern despite accumulating to lower levels than wt RNA2 or the other two derivatives, B2Δ5′ and B2ΔM. As found previously (44), this lower accumulation was presumably due to disruption of the 3′-terminal tRNA-like sequence of BMV RNAs, which confers a degree of 1a-independent stability on these nonpolyadenylated RNAs (50). B2Δ3′ retained the last 48 nt of RNA2 because deletions lacking this extreme 3′-terminal region accumulated to virtually undetectable levels.

FIG. 4.

RNA2 nt 1 to 882 contain sequences required for 1a-induced membrane association. (A) Expression cassettes for wt RNA2 and RNA2 deletion derivatives are diagrammed at the left. Membrane association of these RNAs with or without 1a was assessed by cell fractionation as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and representative Northern blots are shown at the right. Sup., supernatant. (B) As a quantitative measure of 1a responsiveness, the ratio of RNA accumulation in the membrane-associated pellet fraction in the presence and absence of 1a was calculated for each RNA. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown.

In the presence of 1a, the B2Δ3′ and B2ΔM RNAs showed 1a responsiveness equal to that of wt RNA2: 1a induced a seven- to eightfold increase in the accumulation of wt RNA2, B2Δ3′ RNA, and B2ΔM RNA in the membrane-containing pellet fraction (Fig. 4). By contrast, B2Δ5′ RNA, lacking RNA2 nt 1 to 882, completely lost 1a responsiveness, showing equally low accumulation in the membrane pellet in the presence and absence of 1a. Thus, the first 882 bases of RNA2 contain signals required for 1a-induced membrane association, while sequences 3′ to this region are dispensable. The independence of 1a responsiveness from the last 48 nt of RNA2 (the only region common to pB2Δ5′, pB2ΔM, and pB2Δ3′) is addressed below using a chimeric, 3′-polyadenylated RNA.

5′ noncoding and coding sequences influence 1a responsiveness.

To further map RNA2 sequences required for 1a-induced membrane association, smaller deletions within the first 882 nt were made and tested (Fig. 5). In the absence of 1a, all of these deletion derivatives behaved like wt RNA2, with the majority of the RNA recovered in the supernatant fraction of cell lysates (Fig. 5A, −1a lanes). However, the ability of 1a to stimulate accumulation of these RNAs in the pelletable membrane fraction varied considerably with the deletion boundaries (Fig. 5).

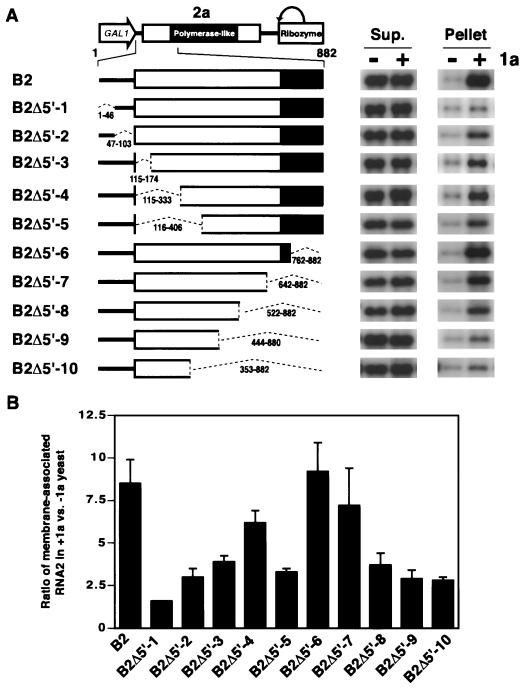

FIG. 5.

Deletion analysis of 5′ proximal RNA2 sequences required for 1a responsiveness. (A) Expression cassettes for wt RNA2 and the indicated RNA2 deletion derivatives are diagrammed at the left. Membrane association abilities of these RNAs in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1a were assessed by cell fractionation as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and representative Northern blots are shown at the right. Sup., supernatant. (B) As a measure of 1a responsiveness, the ratio of RNA accumulation in the membrane-associated pellet fraction in the presence and absence of 1a was calculated for each RNA. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown.

The first deletion derivative tested, B2Δ5′-1, lacked nt 1 to 46 of RNA2. This region was selected because these 5′-terminal nucleotides share sequence similarity and secondary structure potential with the 5′ ends of BMV RNA1 and RNA1 and RNA2 from other bromoviruses and cucumoviruses (see below). This deletion nearly abolished 1a responsiveness: 1a increased accumulation in the membrane-containing pellet fraction 8-fold for wt RNA2 but only 1.6-fold for B2Δ5′-1. Deleting 5′ UTR sequences 3′ of the first 46 bases (B2Δ5′-2) resulted in an intermediate (threefold) 1a stimulation of RNA2 accumulation in the pellet fraction.

Additional deletions were created throughout the 2a ORF up to nt 882. Nested deletions extending 3′ from the 2a start codon up to nt 406 all produced intermediate decreases in 1a responsiveness: for deletions extending to nt 174 (B2Δ5′-3), 333 (B2Δ5′-4), and 406 (B2Δ5′-5), 1a stimulated RNA accumulation in the membrane-containing pellet four-, six-, and threefold, respectively (Fig. 5). Nested deletions extending 5′ from nt 882 caused a progressive decline in 1a responsiveness. Deletion up to nt 762 (B2Δ5′-6) or 642 (B2Δ5′-7) showed wt or near wt RNA2 levels of 1a responsiveness, while extending the deletion endpoint to nt 522, 446, and 353 (B2Δ5′-8 to -10) again reduced 1a stimulation of pelletable RNA2 from eight- to threefold (Fig. 5B). Thus, the conserved 5′-terminal 46 nt of RNA2 appear to be the most important sequences for 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2, while flanking 5′ UTR sequences and a region in the 2a ORF (within RNA2 nt 333 to 642) also are required for full 1a responsiveness.

5′-terminal conserved sequences are essential for 1a responsiveness.

RNA2 nt 1 to 46 have the potential to form a structure consisting of a terminal loop (loop I) followed by a stem (stem I), a bulge loop region (loop II region), and a second stem (stem II) extending to the 5′-terminal nucleotide (Fig. 6A and B). Mutational analysis shows that this region and the predicted positive-strand RNA base pairing are important for RNA2 replication in plant cells (41, 42). A similar stem-loop structure is conserved at the 5′ ends of the RNA1 and RNA2 of other bromoviruses and cucumoviruses (Fig. 6A; see also references 33 and 34). For all of these RNAs, the apex of this structure including loop I and the adjoining nucleotide of stem I comprises an 11-base box B motif corresponding to the invariant residues of the TΨC stem-loop of host tRNAs (Fig. 6A and B). On either side of the box B motif, despite significant sequence divergence, the flanking sequences conserve the ability to form base-paired stems. The box B motif is also an essential part of the intergenic replication enhancer (RE) element required for 1a-induced stabilization and membrane association of RNA3 (reference 50 and unpublished results), where it is also presented at the apex of an extended stem-loop (T. Baumstark and P. Ahlquist, unpublished results).

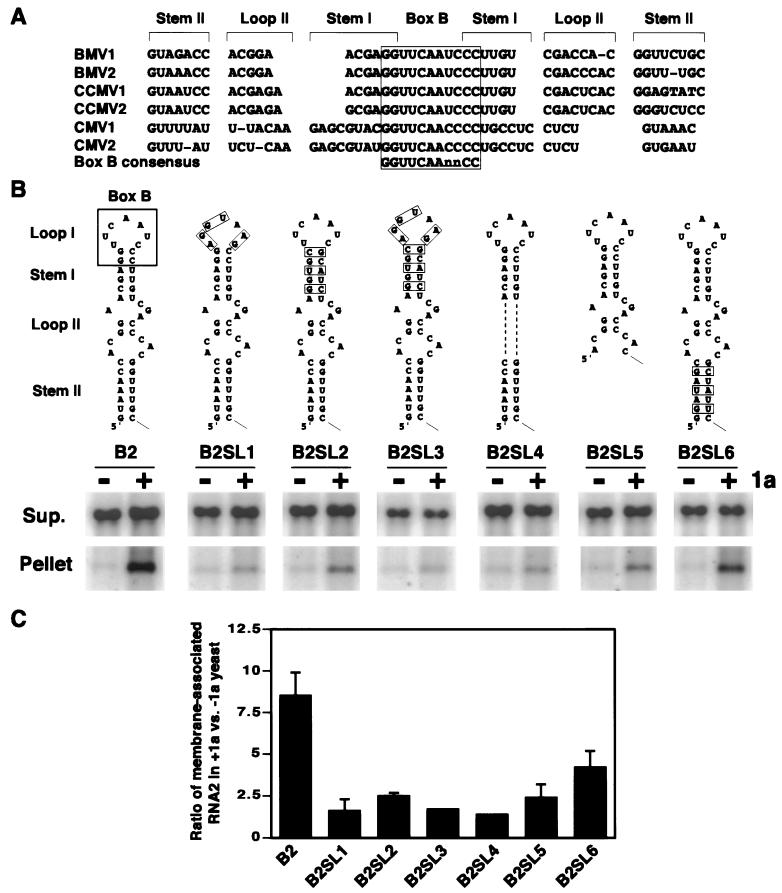

FIG. 6.

RNA2 5′ stem-loop is required for 1a-induced membrane association. (A) Alignment of BMV, cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV), and cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) RNA1 and RNA2 5′-terminal sequences, showing conservation of the box B motif and the potential for base pairing of the surrounding stem regions. (B) Predicted structure of the 5′-terminal stem-loop of BMV wt RNA2 and deletion or base substitution mutants within the stem-loop. Base substitutions are indicated by boxes, and deletions are indicated with dashes. Membrane association abilities of these RNA2 mutants in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1a were assessed by cell fractionation as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and representative Northern blots are shown below each derivative. Sup., supernatant. (C) As a measure of 1a responsiveness, the ratio of RNA accumulation in the membrane-associated pellet fraction in the presence and absence of 1a was calculated for each RNA. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown.

Accordingly, we created a series of RNA2 derivatives with deletions and base substitutions within nt 1 to 46 to test what sequences or structures of this region might be required for 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2 (Fig. 6B). In the absence of 1a, all RNA2 derivatives shown in Fig. 6B behaved like wt RNA2, with the majority of the RNA recovered in the supernatant fraction. However, in the presence of 1a, all of these derivatives were impaired in 1a responsiveness. Sequence changes in either terminal loop I (B2SL1), stem I (B2SL2), or both (B2SL3) largely abolished 1a responsiveness. The same was true for deleting the bulge loop region (B2SL4) or the second stem (B2SL5). Sequence changes in stem II designed to conserve base pairing (B2SL6) had lesser but still significant inhibitory effects on 1a responsiveness. Thus, the whole 5′-terminal stem-loop structure, including the box B motif and flanking elements, contributes to 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2.

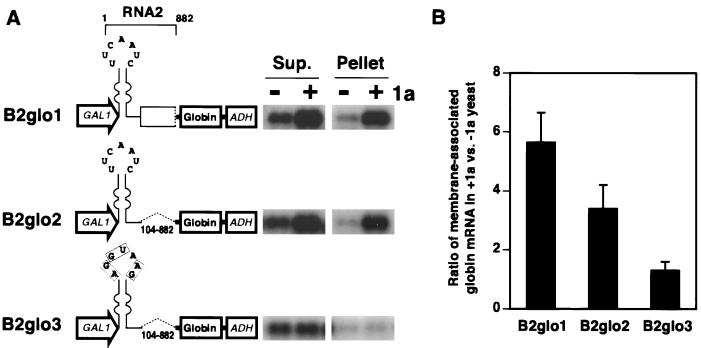

RNA2 5′ UTR confers 1a responsiveness on a nonviral RNA.

To test whether 5′ RNA2 sequences were sufficient for 1a-induced membrane association of RNA2, we constructed chimeric RNAs containing 5′ RNA2 sequences followed by a human β-globin ORF (37, 50) and the yeast ADH1 polyadenylation signal (Fig. 7A). As shown previously, a β-globin mRNA with the same 3′ UTR but a nonviral 5′ UTR lacks 1a responsiveness (50). In chimeras B2glo1 to -3 (Fig. 7A), the β-globin ORF was linked, respectively, to nt 1 to 882 of RNA2, to only the RNA2 5′ UTR (nt 1 to 103), and to the RNA2 5′ UTR with base substitutions in the box B motif. In the absence of 1a, all of these chimeric RNAs accumulated to similar levels and behaved similarly in cell fractionation, with most of the RNA recovered in the supernatant fraction (Fig. 7A). In the presence of 1a, approximately six- and fourfold accumulation increases in the pelletable membrane fraction were observed for β-globin RNA linked to the 5′ 882-nt RNA2 and to the RNA2 5′ UTR, respectively, while base substitutions of the box B motif in the 5′ UTR almost completely abolished 1a responsiveness (Fig. 7). Thus, the RNA2 5′ UTR is sufficient to confer 1a-induced membrane association on a nonviral RNA. However, sequences in the N-terminal region of the 2a ORF enhance this response, in agreement with the Fig. 5 results showing that sequences within RNA2 nt 333 to 642 are required for full 1a responsiveness of wt RNA2.

FIG. 7.

RNA2 5′ UTR and flanking 2a ORF sequences confer 1a responsiveness on a nonviral RNA. (A) Expression cassettes for chimeric RNAs containing the indicated RNA2 sequences, β-globin ORF, and the ADH1 3′ UTR and polyadenylation site are diagrammed at the left. Base substitutions within the box B motif are indicated with boxes. Membrane association abilities of these RNAs in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1a were assessed by cell fractionation as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and representative Northern blots are shown at the right. Sup., supernatant. (B) As a measure of 1a responsiveness, the ratio of RNA accumulation in the membrane-associated pellet fraction in the presence and absence of 1a was calculated for each RNA. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown.

RNA2 sequences required for 1a-induced membrane association are also required for RNA2 replication.

To determine whether the sequences responsible for 1a-induced membrane association were required for RNA2 replication in yeast, selected RNA2 derivatives from Fig. 2 to 6 were tested as replication templates (Fig. 8). Because 2a protein is required for RNA replication and many of these RNA2 derivatives had deletions in the 2a ORF, an additional plasmid was used to provide wt 2a in trans. This 2a expression plasmid produced an mRNA containing the 2a ORF but with the RNA2 5′ and 3′ UTRs replaced by nonviral sequences. Since the viral 5′ and 3′ UTRs contain signals required for RNA2 replication (26, 53), this modified 2a mRNA was unable to serve as a replication template.

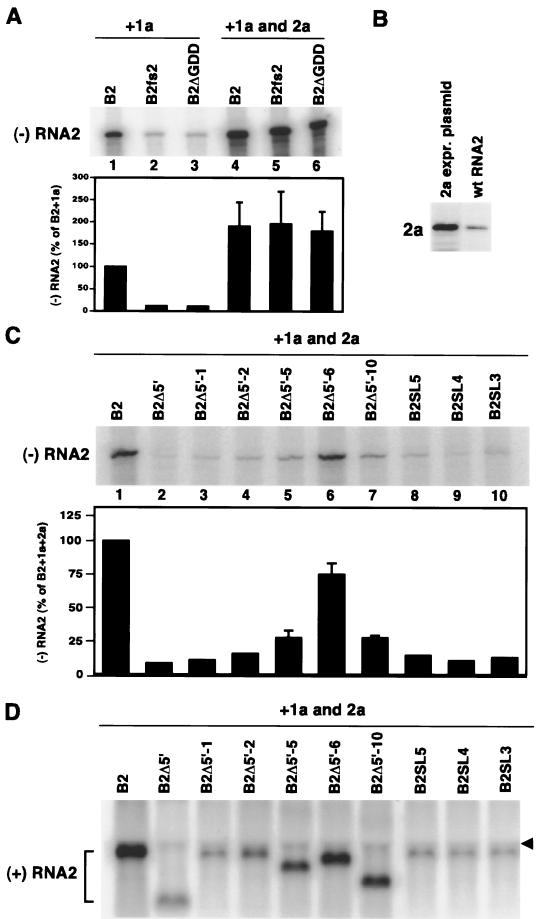

FIG. 8.

RNA2 sequences required for 1a-induced membrane association are also required in cis for RNA2 replication. (A) RNA2 derivatives unable to produce functional 2a are efficiently replicated by 2a provided in trans from pB2YT1, which expresses 2a from a nonreplicatable 2a mRNA with 5′ and 3′ UTR sequences replaced by nonviral sequences. Wt RNA2, B2fs2 (Fig. 3A), and B2ΔGDD (Fig. 2A) were expressed in yeast also expressing 1a or both 1a and 2a in trans. Total RNA was isolated from these yeast cells, and negative-strand RNA2 accumulation was assessed by RNase protection as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown. (B) Comparison of 2a protein accumulation in yeast expressing wt RNA2 from pB2 or expressing chimeric 2a mRNA from 2a expression plasmid pB2YT1. Equal amounts of total protein extract from each cell type were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-2a antibodies. (C) Negative-strand RNA2 accumulation in yeast expressing 1a, 2a, and the indicated RNA2 derivatives, determined by RNase protection as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. Averages and standard errors from three or more independent experiments are shown. (D) Positive-strand RNA2 accumulation in the same yeast as panel C, determined by Northern blotting with a single-stranded, 32P-labeled RNA probe complementary to the conserved 3′ 200 bases of positive-strand BMV RNAs, which hybridizes to wt RNA2 but not the 2a mRNA from pB2YT1. The arrowhead indicates the front edge of the yeast 25S rRNA band. The high concentration of RNA in this band tends to sweep background signals ahead of the rRNA, creating the observed discontinuity in the background.

To assess whether 2a provided by this plasmid could replicate RNA2 in trans, we used RNA2 derivatives whose 2a function was blocked by a frameshift mutation (B2fs2 in Fig. 3) or by deleting the conserved GDD motif of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (B2ΔGDD in Fig. 2). In the presence of 1a but absence of functional 2a provided in trans, only weak negative-strand RNA2 signals were detected for B2fs2 and B2ΔGDD (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 3), equivalent to the 2a-independent background seen previously (Fig. 2A). Supplying both 1a and 2a in trans produced two notable effects. First, the level of negative-strand RNA2 detected for wt RNA2 was twofold above that when 1a alone was provided in trans (Fig. 8A, lanes 1 and 4). Similarly, positive-strand RNA2 levels increased 2.5-fold over RNA2 replication from 2a provided in cis, reaching levels 5-fold over those of DNA-derived RNA2 transcripts (Fig. 8D and results not shown). These increases in RNA2 replication products coincided with and were presumably due to a fivefold increase in 2a protein expression relative to yeast containing wt RNA2 (Fig. 8B). Second, when 1a and 2a were provided in trans, negative-strand RNA2 levels for B2fs2 and B2ΔGDD were equivalent to those of wt RNA2 (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 to 6). Thus, when 2a was provided in trans, RNA2 templates unable to produce functional 2a in cis were replicated as efficiently as wt RNA2.

Next, selected RNA2 derivatives with various levels of 1a responsiveness were tested for their function as RNA replication templates when both 1a and 2a were supplied in trans. The level of 1a-induced membrane association of the various RNA2 mutants (Fig. 4 to 6) correlated well with their abilities to serve as replication templates to produce negative-strand RNA2 (Fig. 8C), and amplification of positive-strand RNA2 (Fig. 8D) paralleled negative-strand RNA2 production. For example, B2Δ5′ and B2Δ5′-1, which had little or no 1a responsiveness for membrane association (Fig. 4 and 5), produced only background levels of negative-strand RNA2 signal (Fig. 8C, lanes 2 and 3) and similarly low positive-strand RNA2 levels (Fig. 8D, lanes 2 and 3). By contrast, B2Δ5′-6, showing wt 1a responsiveness (Fig. 5), produced the highest levels of negative- and positive-strand RNA2 among the mutants (70 to 75% of wt; Fig. 8C and D, lanes 6). The other RNA2 mutants all showed intermediate levels of 1a responsiveness (Fig. 5 and 6), and their degree of 1a responsiveness correlated with their relative ranking in negative- and positive-strand levels. For example, B2Δ5′-5 and B2Δ5′-10, which had the second-highest 1a responsiveness among the tested mutants (after B2Δ5′-6), also had the second-highest levels of negative- and positive-strand RNA2 among the mutants (Fig. 8C and D, lanes 5 and 7). The results imply that 1a responsiveness, as measured by RNA2 stabilization and membrane association, is an important though not the only requirement for RNA2 replication.

DISCUSSION

Prior studies of BMV RNA replication in yeast have used templates derived from genomic RNA3. In this report, we demonstrated that yeast expressing viral replication factors 1a and 2a also replicate genomic RNA2, further validating yeast as a model host for studies of BMV RNA replication. In the absence of 2a protein and RNA replication, the ER-associated 1a protein stabilized RNA2 and induced it to associate with the rapidly sedimenting cellular membrane fraction (Fig. 3). As discussed further below, 1a-induced RNA2 stabilization and membrane association as well as 1a- and 2a-mediated-RNA2 replication in yeast required sequences previously identified as cis-acting signals for RNA2 replication in natural plant hosts (42, 53, 54). The results show close parallels to the 1a- and the 1a- and 2a-responsive behavior of RNA3 templates and imply that 1a-induced RNA stabilization and membrane association reflect general features of 1a action on BMV RNA replication templates.

RNA2 replication in yeast.

Simultaneous production of 1a and 2a-expressing wt RNA2 in yeast induced synthesis of negative-strand RNA2 and amplification of positive-strand RNA2 (Fig. 2 and 8). Out of the multiple 5′ ends generated by DNA transcription, RNA replication amplified the specific RNA2 5′ end of natural infection products (Fig. 2C). As in plant cells (41, 54), 2a functioned in trans to replicate RNA2 templates unable to produce functional 2a in cis (Fig. 8). This contrasts with another tripartite RNA plant virus, alfalfa mosaic virus, whose analogous RNA2 templates can be replicated only by a 2a homologue produced in cis (55). For BMV in yeast, an engineered 2a mRNA unable to function as a replication template produced higher levels of 2a protein than wt RNA2 and supported higher levels of RNA2 replication (Fig. 8). Similar or even greater increases in RNA replication were seen in plant cells when 2a was expressed from a DNA plasmid rather than from replicating RNA2 (16).

When 2a was supplied in cis or in trans under the conditions used here, RNA replication amplified positive-strand RNA2 two- and fivefold, respectively, over the level of DNA-derived RNA2 transcripts from the strong yeast GAL1 promoter (Fig. 2B and 8D). In the further presence of RNA3-expressed BMV coat protein, which encapsidates and stabilizes RNA2 in yeast (31), RNA replication amplified RNA2 18-fold over DNA-derived RNA2 transcripts (Fig. 2B). Thus, in the absence of coat protein, higher levels of RNA2 replication products were generated but turned over. 1a- and 2a-expressing yeast amplify wt RNA3 to higher levels than RNA2, viz., 45-fold over the levels of GAL1-promoted RNA3 transcripts (24). RNA3 also replicates to significantly higher levels than RNA2 in natural BMV infections of plants (39).

RNA2 sequences required in cis for 1a responsiveness.

The first 882 nt of RNA2 contained sequences essential for 1a-induced membrane association (Fig. 4) and conferred nearly wt RNA2 levels of 1a responsiveness on β-globin mRNA (Fig. 7). By contrast, deleting the middle third or 3′ third of RNA2 had little or no effect on 1a responsiveness (Fig. 4). Further mapping showed that the 103-nt 5′ UTR was essential for 1a-induced membrane association (Fig. 5 and 6), and this 5′ UTR alone transferred much of the 1a responsiveness of RNA2 to β-globin mRNA (Fig. 7).

The first 46 nt of the RNA2 5′ UTR were crucial for 1a responsiveness. These nucleotides are predicted to form a 5′-terminal stem-loop structure whose apical loop and flanking base pairs duplicate the arrangement of the conserved residues in the TΨC stem-loops of tRNAs (Fig. 6A and B). Prior mutational analysis supports the existence of this stem-loop (42). 1a responsiveness was abolished by mutations in the box B loop and was highly sensitive to deletions or substitutions in other features of the stem-loop, including the base-paired stem regions and two bulge loops (Fig. 6B and C).

In addition to this 5′ stem-loop, full 1a responsiveness required flanking 5′ UTR sequences and 5′ proximal sequences of the 2a ORF, particularly sequences within nt 333 to 762 (Fig. 5 and 7). However, while these sequences enhanced 1a responsiveness, they were unable to independently confer significant 1a responsiveness in the absence of the RNA2 5′ UTR (Fig. 5).

1a-responsive signals are required for RNA2 replication.

As with RNA3, the RNA2 regions responsible for 1a-induced membrane association were required in cis for RNA2 replication in yeast and in the natural plant hosts of BMV. In the 5′-terminal stem-loop, substitutions throughout the box B motif inhibit RNA2 replication in plant cells expressing 1a and 2a in trans, as do substitutions partially disrupting the predicted base pairing shown in Fig. 6B (41, 42). Substitutions or deletions in these same stem and loop regions also severely inhibited RNA2 replication in yeast expressing 1a and 2a in trans (Fig. 8). Efficient RNA2 replication in plant protoplasts also requires in cis a subset of 2a ORF sequences within nt 257 to 887 (54). This corresponds well to the 2a ORF segment that stimulated 1a responsiveness (Fig. 5) and RNA2 replication template activity in 1a- and 2a-expressing yeast (Fig. 8C and D). Thus, deletions and substitutions in the RNA2 5′ UTR and 2a ORF all had closely parallel cis effects on 1a responsiveness and RNA2 replication template activity in yeast and plant cells.

The parallel between the function of these RNA2 sequences in 1a responsiveness and RNA2 replication extends to the polarity of the RNA strand in which they act. 1a stabilized and induced membrane association of positive-strand RNA2 (Fig. 2). Similarly, 1a- and 2a-mediated RNA replication requires the 5′ stem-loop in positive-strand RNA2, not a complementary structure in negative-strand RNA2 (41). Specifically, the activity of RNA2 as a replication template in 1a- and 2a-expressing plant cells was inhibited 85 to 95% by mutations that disrupted base pairing in the positive-strand 5′ stem-loop while creating G · U base pairs to preserve the complementary negative-strand 3′ stem-loop. Conversely, RNA2 replication was not inhibited by mutations disrupting the negative-strand 3′ stem-loop while preserving the positive-strand 5′ stem-loop.

Relation to BMV RNA1, RNA3, and other viruses.

In addition to BMV RNA2, BMV RNA1, and RNA1 and RNA2 of other bromoviruses and cucumoviruses conserve the potential for similar 5′-terminal stem-loops, each equivalently presenting the conserved TΨC loop residues (box B motif) at its apex (7, 34, 41, 42) (Fig. 6A). Such conservation implies a conserved role or roles in infection.

For comparison, 1a-induced stabilization and membrane association of BMV RNA3 is mediated by an ∼150-nt intergenic RE segment that makes a nonviral mRNA fully responsive to 1a-induced stabilization (50; Sullivan et al., unpublished). As in RNA2, this RNA3 RE segment contains a tRNA-like box B motif that is required, together with flanking sequences, for 1a responsiveness (50). Moreover, RNA structure probing shows that the RNA3 box B motif is also presented in the apex of a stem-loop that mirrors the TΨC stem-loops of tRNAs (Baumstark and Ahlquist, unpublished). Like RNA2 sequences required for 1a responsiveness, the RE is required for efficient RNA3 replication in plant cells and yeast, and RE mutations inhibit or stimulate 1a responsiveness and RNA3 replication coordinately (18, 50). Thus, RNA2 replication and RNA3 replication require similar box B-containing signals that direct 2a-independent, 1a-induced RNA stabilization and related effects.

As noted in the introduction, 1a-induced stabilization and membrane association of RNA3 are closely linked to inhibition of RNA3 translation and stimulation of negative-strand RNA3 synthesis (25, 50). Assaying in vivo negative-strand synthesis in the absence of positive-strand synthesis shows that the RE enhances negative-strand RNA3 synthesis 50- to 100-fold (44). This duplicates the RE's stimulatory effect on full RNA3 replication (18, 50), suggesting that the RE may act primarily at or before negative-strand RNA synthesis. A possible analog to the action of 1a on RNA3 is found in poliovirus protein 3CD, which interacts with poliovirus positive-strand RNA to inhibit translation and promote negative-strand RNA synthesis. Interestingly, 3CD mediates these effects by interacting with a 5′ proximal cloverleaf structure in poliovirus RNA (20).

The extensive similarities between the roles of box B-containing elements in 1a responsiveness and replication of RNA2 and RNA3, as well as the role of 5′ sequences in poliovirus RNA, suggest that the 1a responsiveness of the positive-strand RNA2 5′ end also might be involved in inhibiting translation and stimulating negative-strand RNA synthesis. Such a role would not preclude the possibility that RNA2 5′ sequences or their complements in negative-strand RNA2 may also play a role in positive-strand RNA2 synthesis, as previously suggested from kinetic studies (43). Similarly, though involved in negative-strand RNA synthesis, poliovirus 5′ proximal sequences may also contribute to positive-strand initiation (8, 20).

Although the 1a-responsive intergenic RE is over 1 kb from the RNA3 5′ end, 1a action on RNA3 may also involve direct or indirect interaction with the 5′ end, suggesting possible similarities with poliovirus RNA and BMV RNA2. Efficient 1a-induced stabilization of RE-containing RNAs requires a 5′ UTR functional for translation initiation (50) and either host protein Lsm1p or a cis-linked 3′ poly(A) (15). Both poly(A) and Lsm1p mediate interactions with mRNA 5′ ends: poly(A) stabilizes the interaction of translation factors with mRNA 5′ ends, while Lsm1p stimulates the action of decapping factor Dcp1p on 5′ ends (12, 13, 52). Dcp1p recently was found to interact with poly(A)-stabilized translation initiation factor eIF4G (56), confirming an inferred linkage between these processes (15). For RNA3, as well as poliovirus RNA and perhaps BMV RNA2, involvement of the 5′ end may facilitate inhibiting translation preparatory to RNA replication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yuriko Tomita and Masayuki Ishikawa for generously providing pB1YT1; Michael Sullivan, Michael Janda, and Tilman Baumstark for sharing unpublished results; and additional members of our laboratory for helpful discussions throughout these experiments.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grant GM35072. P.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlquist P. Bromovirus RNA replication and transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1992;2:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlquist P, Janda M. cDNA cloning and in vitro transcription of the complete brome mosaic virus genome. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2876–2882. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahola T, Ahlquist P. Putative RNA capping activities encoded by brome mosaic virus: methylation and covalent binding of guanylate by replicase protein 1a. J Virol. 1999;73:10061–10069. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10061-10069.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahola T, den Boon J, Ahlquist P. Helicase and capping enzyme active site mutations in brome mosaic virus protein 1a cause defects in template recruitment, negative-strand RNA synthesis, and viral RNA capping. J Virol. 2000;74:8803–8811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8803-8811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison R, Thompson C, Ahlquist P. Regeneration of a functional RNA virus genome by recombination between deletion mutants and requirement for cowpea chlorotic mottle virus 3a and coat genes for systemic infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1820–1824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allison R F, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Infectious in vitro transcripts from cowpea chlorotic mottle virus cDNA clones and exchange of individual RNA components with brome mosaic virus. J Virol. 1988;62:3581–3588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.10.3581-3588.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allison R F, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Sequence of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus RNAs 2 and 3 and evidence of a recombination event during bromovirus evolution. Virology. 1989;172:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andino R, Rieckhof G E, Baltimore D. A functional ribonucleoprotein complex forms around the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA. Cell. 1990;63:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argos P. A sequence motif in many polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9909–9916. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton D J, Morasco B J, Flanegan J B. Translating ribosomes inhibit poliovirus negative-strand RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1999;73:10104–10112. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10104-10112.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boeck R, Lapeyre B, Brown C E, Sachs A B. Capped mRNA degradation intermediates accumulate in the yeast spb8–2 mutant. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5062–5072. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouveret E, Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Seraphin B. A sm-like protein complex that participates in mRNA degradation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1661–1671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Ahlquist P. Brome mosaic virus polymerase-like protein 2a is directed to the endoplasmic reticulum by helicase-like viral protein 1a. J Virol. 2000;74:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4310-4318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diez J, Ishikawa M, Kaido M, Ahlquist P. Identification and characterization of a host protein required for efficient template selection in viral RNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3913–3918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080072997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinant S, Janda M, Kroner P A, Ahlquist P. Bromovirus RNA replication and transcription require compatibility between the polymerase- and helicase-like viral RNA synthesis proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:7181–7189. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7181-7189.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.French R, Ahlquist P. Characterization and engineering of sequences controlling in vivo synthesis of brome mosaic virus subgenomic RNA. J Virol. 1988;62:2411–2420. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.7.2411-2420.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French R, Ahlquist P. Intercistronic as well as terminal sequences are required for efficient amplification of brome mosaic virus RNA3. J Virol. 1987;61:1457–1465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1457-1465.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.French R, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Bacterial gene inserted in an engineered RNA virus: efficient expression in monocotyledonous plant cells. Science. 1986;231:1294–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.231.4743.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamarnik A V, Andino R. Switch from translation to RNA replication in a positive-stranded RNA virus. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2293–2304. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restrictions sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicases: amino acid sequence comparisons and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haseloff J, Goelet P, Zimmern D, Ahlquist P, Dasgupta R, Kaesberg P. Striking similarities in amino acid sequence among nonstructural proteins encoded by RNA viruses that have dissimilar genomic organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4358–4362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa M, Janda M, Krol M A, Ahlquist P. In vivo DNA expression of functional brome mosaic virus RNA replicons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Virol. 1997;71:7781–7790. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7781-7790.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janda M, Ahlquist P. Brome mosaic virus RNA replication protein la dramatically increases in vivo stability but not translation of viral genomic RNA3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2227–2232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janda M, Ahlquist P. RNA-dependent replication, transcription, and persistence of brome mosaic virus RNA replicons in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1993;72:961–970. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90584-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janda M, French R, Ahlquist P. High efficiency T7 polymerase synthesis of infectious RNA from cloned brome mosaic virus cDNA and effects of 5′ extensions on transcript infectivity. Virology. 1987;158:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston M, Davis R W. Sequences that regulate the divergent GAL1-GAL10 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1440–1448. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamer G, Argos P. Primary structural comparison of RNA-dependent polymerases from plant, animal, and bacterial viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7269–7282. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong F, Sivakumaran K, Kao C. The N-terminal half of the brome mosaic virus 1a protein has RNA capping-associated activities: specificity for GTP and S-adenosylmethionine. Virology. 1999;259:200–210. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krol M A, Olson N H, Tate J, Johnson J E, Baker T S, Ahlquist P. RNA-controlled polymorphism in the in vivo assembly of 180- subunit and 120-subunit virions from a single capsid protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13650–13655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh L E, Dreher T W, Hall T C. Mutational analysis of the core and modulator sequences of the BMV RNA3 subgenomic promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:981–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh L E, Hall T C. Evidence implicating a tRNA heritage for the promoters of positive-strand RNA synthesis in brome mosaic and related viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:331–341. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh L E, Pogue G P, Hall T C. Similarities among plant virus (+) and (−) RNA termini imply a common ancestry with promoters of eukaryotic tRNAs. Virology. 1989;172:415–427. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller W A, Bujarski J J, Dreher T W, Hall T C. Minus-strand initiation by brome mosaic virus replicase within the 3′ tRNA-like structure of native and modified RNA templates. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:537–546. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mise K, Allison R F, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Bromovirus movement protein genes play a crucial role in host specificity. J Virol. 1993;67:2815–2823. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2815-2823.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman T C, Ohme-Takagi M, Taylor C B, Green P J. DST sequences, highly conserved among plant SAUR genes, target reporter transcripts for rapid decay in tobacco. Plant Cell. 1993;5:701–714. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak J E, Kirkegaard K. Improved method for detecting poliovirus negative strands used to demonstrate specificity of positive-strand encapsidation and the ratio of positive to negative strands in infected cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3384–3387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3384-3387.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacha R F, Ahlquist P. Use of bromovirus RNA3 hybrids to study template specificity in viral RNA amplification. J Virol. 1991;65:3693–3703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3693-3703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peltz S W, Jacobson A. mRNA turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Belasco J, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 291–328. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pogue G P, Hall T C. The requirement for a 5′ stem-loop structure in brome mosaic virus replication supports a new model for viral positive-strand RNA initiation. J Virol. 1992;66:674–684. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.674-684.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pogue G P, Marsh L E, Connell J P, Hall T C. Requirements for ICR-like sequences in the replication of brome mosaic virus genomic RNA. Virology. 1992;188:742–753. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90529-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pogue G P, Marsh L E, Hall T C. Point mutations in the ICR2 motif of brome mosaic virus RNAs debilitate (+)-strand replication. Virology. 1990;178:152–160. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quadt R, Ishikawa M, Janda M, Ahlquist P. Formation of brome mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in yeast requires coexpression of viral proteins and viral RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao A L N, Hall T C. Requirement for a viral trans-acting factor encoded by brome mosaic virus RNA-2 provides strong selection in vivo for functional recombinants. J Virol. 1990;64:2437–2441. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2437-2441.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Restrepo-Hartwig M, Ahlquist P. Brome mosaic virus helicase- and polymerase-like proteins colocalize on the endoplasmic reticulum at sites of viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:8908–8916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8908-8916.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Restrepo-Hartwig M, Ahlquist P. Brome mosaic virus RNA replication proteins 1a and 2a colocalize and 1a independently localizes on the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1999;73:10303–10309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10303-10309.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sacher R, Ahlquist P. Effects of deletions in the N-terminal basic arm of brome mosaic virus coat protein on RNA packaging and systemic infection. J Virol. 1989;63:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4545-4552.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan M, Ahlquist P. A brome mosaic virus intergenic RNA3 replication signal functions with viral replication protein 1a to dramatically stabilize RNA in vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:2622–2632. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2622-2632.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan M, Ahlquist P. Cis-acting signals in bromovirus RNA replication and gene expression: networking with viral proteins and host factors. Semin Virol. 1997;8:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tharun S, He W, Mayes A E, Lennertz P, Beggs J D, Parker R. Yeast sm-like proteins function in mRNA decapping and decay. Nature. 2000;404:515–518. doi: 10.1038/35006676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Traynor P, Ahlquist P. Use of bromovirus RNA2 hybrids to map cis- and trans-acting functions in a conserved RNA replication gene. J Virol. 1990;64:69–77. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.69-77.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Traynor P, Young B M, Ahlquist P. Deletion analysis of brome mosaic virus 2a protein: effects on RNA replication and systemic spread. J Virol. 1991;65:2807–2815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2807-2815.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Rossum C M A, Garcia M L, Bol J F. Accumulation of the alfalfa mosaic virus RNAs 1 and 2 requires the encoded proteins in cis. J Virol. 1996;70:5100–5105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5100-5105.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vilela C, Velasco C, Ptushkina M, McCarthy J E. The eukaryotic mRNA decapping protein Dcp1 interacts physically and functionally with the eIF4F translation initiation complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:4372–4382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]