Abstract

Abstract

Alcohol consumption is known to cause several brain anomalies. The pathophysiological changes associated with alcohol intoxication are mediated by various factors, most notable being inflammation. Alcohol intoxication may cause inflammation through several molecular mechanisms in multiple organs, including the brain, liver and gut. Alcohol-induced inflammation in the brain and gut are intricately connected. In the gut, alcohol consumption leads to the weakening of the intestinal barrier, resulting in bacteria and bacterial endotoxins permeating into the bloodstream. These bacterial endotoxins can infiltrate other organs, including the brain, where they cause cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation. Alcohol can also directly affect the brain by activating immune cells such as microglia, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neuroinflammation. Since alcohol causes the death of neural cells, it has been correlated to an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases. Besides, alcohol intoxication has also negatively affected neural stem cells, affecting adult neurogenesis and causing hippocampal dysfunctions. This review provides an overview of alcohol-induced brain anomalies and how inflammation plays a crucial mechanistic role in alcohol-associated pathophysiology.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Alcohol intoxication, Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, Adult neurogenesis, Toxicity

Introduction

Alcohol is considered the most abused psychoactive addictive substance worldwide. Consequently, alcohol intoxication contributes massively to the global disease burden (Rehm and Shield 2019). According to World Health Organization, three million deaths occur every year from the harmful use of alcohol, a whopping 5.3% of worldwide deaths (WHO 2019). Alcohol abuse affects multiple organs in the body, including the liver, gut and brain. Alcohol is known to have a direct toxic effect on the brain via several distinct mechanisms, the most notable among them being inflammation (Crews and Vetreno 2014).

Chronic and sustained ingestion of alcohol induces systemic and central inflammation and triggers cognitive impairment in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Chronic alcohol abuse decreases the serum levels of the anti-inflammatory immunoregulatory protein, cluster of differentiation-200 (CD200), with its levels rising only after alcohol abstinence (Chaturvedi et al. 2020). Alcohol intoxication increases the levels of serum pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, resulting in attention deficits and compromised executive functioning (Yun et al. 2021). Studies have observed detrimental and neuroinflammatory consequences of ethanol exposure in brain regions of rodents such as the hippocampus and frontal cortex (Schneider et al. 2017; Baradaran et al. 2021). Changes to gut microflora act as the primary source of alcohol-mediated inflammation following alcohol use. Several studies have reported that changes in the milieu of intestinal bacteria drive detrimental changes in the central nervous system (CNS) (Cannon et al. 2018). The alcohol-induced alterations in the gut microbiome are intricately related to cognitive dysfunction and activation of pro-inflammatory immune cells in the brain.

Alcohol consumption also affects the brain directly. Alterations in brain structure and associated behavioral dysfunctions are characteristic of alcohol abuse. Prolonged alcohol abuse can cause critical molecular changes in the brain, leading to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Clinical manifestations of alcohol-associated neuropathological changes include dendritic loss and neuronal atrophy of the cortices leading to enlarged lateral ventricles, thinning of the cortical lining in the temporal lobe, and glial cell reduction in the temporal and frontal cortices (Bühler and Mann 2011). Alcohol and its metabolites induce aberrant reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the brain. Neurons and glial cells respond to increased oxidative stress through neuroimmune responses by increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and heightened interaction between toll-like receptors (TLR) and High mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1). At the tissue level, chronic alcoholism induced cognitive impairment is an output of white matter atrophy, demyelination and axonal loss at various brain regions, including the frontal lobe, hippocampus, and corpus callosum. Additionally, impairments in lipid metabolism also contribute to myelin disintegration in chronic binge alcohol consumption (Kamal et al. 2020). Together these reactions force the alcohol-exposed cells towards neurodegeneration and associated consequences.

This review focuses on the detrimental effects of alcohol abuse, mediated primarily via neuroinflammation, on brain health. We have discussed the underlying molecular causes of alcohol-induced inflammation in the gut and the nervous system. The alcohol-induced pathological interventions in these two organ systems share an intimate bond that leads to several brain anomalies. Hence, we have touched upon the detrimental effect of alcohol on these two organ systems and how they are interconnected. We have discussed alcohol-induced neurodegeneration in detail and how it might be partly mediated or complemented by a compromised adult neurogenic machinery.

Mechanisms Underpinning Alcohol-Induced Neuroinflammation

The mechanisms underlying alcohol-associated neuroinflammation are complex and not fully deciphered, albeit many studies have attempted to elucidate the same. The chronic and binge ethanol intake mouse model of liver disease developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) closely mimics how humans consume alcohol (Bertola et al. 2013). Besides liver injury, this model induced neuroinflammation in the dorsal hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) by increasing gene expression levels of pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-β, IL-6, MCP-1) (King et al. 2020). Chronic alcohol consumption activates the pro-inflammatory phenotype of the neuroglial cells, particularly microglia and astroglia (Gómez et al. 2018; Melbourne et al. 2019; Crews et al. 2021; Villavicencio-Tejo et al. 2021). These glial cells present specific pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), TLRs and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) that recognize cellular damage signals called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in addition to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). When stimulated, these TLRs and NLRs activate signaling cascades associated with inflammation, mainly the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and interferon response factor 3 (IRF3) pathways.

The Role of TLR4 in Alcohol-Induced Neuroinflammation

Both invitro and invivo models suggest that ethanol activates NF-κB and promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced neuroinflammation in glial cells via TLR2/myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) and TLR3/NF-κB signaling (Qi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020). The microglial activity is upregulated in the hippocampal tissue of post-mortem alcoholic brains, coinciding with an increased expression of TLR7 (Coleman et al. 2017). Although chronic alcohol consumption activates several TLR subtypes, the focal subject of alcohol-induced TLR-dependent neuroinflammation is TLR4. TLR4 signaling seems crucial for alcohol-stimulated astroglia and microglial activation and overall neuroinflammation since deletion of TLR4 abolished these effects in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of TLR4-KO (knockout) mice (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2010; Li et al. 2019). In addition, alcohol increased the levels of MyD88, activated the NF-κB-65 subunit, and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, while no such observation occurred in TLR4-KO mice (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2010). Further, cognitive dysfunction in compromised motor functioning after alcohol consumption depends on TLR4-MyD88 signaling (Wu et al. 2012). The effects of binge drinking on TLR4-mediated inflammation in the brain appear to be sex-dependent and region-specific, with alcohol being able to elevate TLR4 expression in the medial PFC only in male rats. In contrast, TLR4 levels were increased in both sexes in the hippocampus (Silva-Gotay et al. 2021).

The Role of miRNAs in Alcohol-Induced Neuroinflammation

Mounting evidence has also shown an increased expression of other ligands that bind to TLR-4, including microRNA (miRNA)-155 (Lippai et al. 2013a). Recent studies suggest that female adolescents may be more vulnerable to the neuroinflammatory consequences of binge drinking-related to the serum content of circulating anti-inflammatory miRNAs in extracellular vesicles (EVs) (Ibáñez et al. 2020). In female mice, alcohol decreased brain-specific anti-inflammatory miRNAs like mir-146a-5p and mir-21-5p while concurrently boosting the expression levels of pro-inflammatory genes, implying that miRNAs could be potential alcohol-induced neuroinflammation biomarkers. Alcohol-induced NF-κB activation and upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators was not observed in miR-155 knockout mice, and inhibition of TLR4, in turn, prevented the activation of mir-155 (Lippai et al. 2013a). Alcohol-exposed immune cells, such as monocytes, communicate with naïve monocytes via EVs-enclosed miRNAs such as miR-27a (Saha et al. 2016). Similarly, alcohol-exposed astroglia may propagate and amplify neuroinflammation by communicating with naïve neurons via miRNAs in EVs. In vitro, ethanol treatment boosted the number of EVs secreted by astrocytes in a TLR-4-dependent fashion, and interestingly, these vesicles were internalized by neurons incubated with these astrocytes (Ibáñez et al. 2019). Further, this internalization caused elevated neuronal levels of IL-1β and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and subsequent neuronal death. Next-generation sequencing revealed that miRNAs are differentially expressed in the mouse cerebral cortex upon chronic alcohol exposure and are involved in TLR4-dependent neuroinflammatory signaling (Ureña-Peralta et al. 2018).

The Role of NLRP3 in Alcohol-Induced Neuroinflammation

NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) is a well-characterized inflammasome PRR involved in inflammatory processes. It is best known for mediating the activation of caspase-1 and subsequent generation of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Exposure to ethanol activates the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in vitro (De Filippis et al. 2016). In vivo, chronic alcohol consumption activated NLRP3 signaling and elevated IL-1β and IL-18 levels in the medial frontal cortex, which was averted in TLR4-KO mice (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2014). Similarly, alcohol-associated decreases in blood–brain barrier integrity, neuroinflammation, and overall brain insult occur through TLR4/NLRP3 signaling via astroglia and microglia activation (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2014). Deletion of NLRP3 protects against alcohol-associated increases in caspase-1 and IL-1β levels in the cerebellum and cerebrum of mice (Lippai et al. 2013a). Blocking the activity of NLRP3 using MCC950, an NLRP3 inhibitor, markedly reduced alcohol consumption in mice, with a sex-related difference in alcohol preference at least, with MCC950 failing to reduce alcohol preference in males (Lowe et al. 2020). Taken together, chronic alcohol consumption mediates inflammation by activating neuroglial cells, NF-κB signaling, increasing the expressions of TLR3/4 ligands, including microRNA and NLRP3.

Alcohol, Inflammation and Gut Dysbiosis

Several studies have reported that changes in the milieu of intestinal bacteria induce changes in the CNS gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and intestinal epithelium. These changes create an intestinal epithelial barrier by restricting the translocation of intestinal bacteria lumen while permitting selective absorption of essential nutrients. The intestinal barrier's humoral, immunological, and physical components get affected by alcohol. The intestinal epithelial barrier gets additionally supported by specialized cells like Goblet and Paneth cells that produce mucus secretions and antibacterial proteins that interact with and destroy any bacteria infiltrating the mucus layer. The intricate spatial arrangement of tight junctions also restricts the paracellular transport between epithelial cells (Ghosh et al. 2020). Studies have reported drastic changes in the intestinal microbiome composition following alcohol consumption. (Engen et al. 2015). The antibacterial proteins mostly kill Proteobacteria of the class Gamma proteobacteria and Firmicute of the class Bacilli, constituting about 85% to 90% of bacteria within the gut class (Mutlu et al. 2012). These antibacterial proteins provide low antibiotic activity and help intestinal host defense against the increase of harmful bacteria. The changes in the intestinal microbiome also include increased enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. This can exacerbate the already damaged intestinal barrier and propagate alcohol-induced injury to the gut-liver axis (Bajaj and Hepatology 2019). Chronic alcohol consumption may decrease the abundance of antimicrobial proteins Reg3b and Reg3g contributing to enteric dysbiosis (Hendrikx et al. 2019). The gut microbial changes also include intestinal hypoxia-induced factor 1α activity, which is crucial in developing alcohol-associated hepatic steatosis (Nath et al. 2011).

Alcohol consumption alone perturbs the intestinal barrier resulting in a leaky gut that allows the bacteria and other endotoxins from the gut to penetrate the mucosa and enter the systemic circulation (Ghosh et al. 2020). Alcohol consumption disrupts the integrity of intestinal epithelial cells by different mechanisms, thereby increasing gut leakage. The generation of ROS following alcohol consumption, especially nitric oxide (NO), disrupts the intestinal barrier, which otherwise, at its basal levels, regulates the normal function of the intestinal wall (Liu et al. 2020). Alcohol consumption causes disruptions at the apexes of the villi and hemorrhagic erosions at the lamina propria of the GALT by changing the intestinal microenvironment. This dysbiosis results in bacterial translocation out of the gut and circulation, resulting in systemic inflammation (Cannon et al. 2018). Alcohol also stimulates the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) within the gut microenvironment leading to degranulation of mast cells and triggering paracrine like secretions that increase gut permeability. This increased gut permeability allows bacteria and bacterial endotoxins like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to breach the gastrointestinal barrier stimulating the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α from myeloid cells into the lumen, causing systemic inflammation (Leclercq et al. 2014b). Following alcohol administration, myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK), a downstream target of TNF-α, is phosphorylated in the intestinal epithelial cells, redistributing the tight junction proteins, thereby increasing the intestinal permeability (Mutlu et al. 2012). Alcohol intoxication activates NF-kB following the disruption of I-kBα that causes dysregulation of the actin assembly and architecture, affecting the integrity of the epithelial barrier (Banan et al. 2007). Alcohol induces miR-212 over-expression resulting in gut leakiness by down-regulating ZO-1, a regulator of intestinal permeability. (Tang et al. 2015).

Alcohol and Gut–Liver Interactions

Alcohol consumption disrupts the epithelial barrier allowing bacteria and bacterial endotoxins to translocate into mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), acting as the primary firewalls. Following alcohol consumption, MLN are overwhelmed and fail to contain the bacteria and bacterial endotoxins which reach the liver via mesenteric and portal circulations. This infiltration results in the recruitment of systemic inflammatory cells like T-cells and monocytes, perpetuating liver inflammation (Ju and Mandrekar 2015). This alcohol-mediated inflammation results in hepatocyte cell death by apoptosis and necrosis, which further activates hepatic stellate cells leading to the development of liver fibrosis. Liver disease from dysbiosis and intestinal permeability disruptions also underlies other metabolic and neurological disorders. Alcohol intoxication causes persistent activation of the immune response and results in the dysregulation of hepatic hepcidin leading to redox imbalance and iron deficiency in the liver. These deficits in the liver metabolism collectively result in the developing of multiple diseases like type 2 diabetes Miletus, atherosclerosis, heart failure, and Alzheimer's disease (Puri et al. 2017).

Alcohol, Inflammation and the Gut–Brain Axis

It is a well-known fact that the brain helps control the physiological functions of the gut, which can reciprocally regulate the brain's functions. Previous reports suggest that alcohol-induced leaky gut and subsequent systemic inflammation can modulate brain functions in several ways. The composition of intestinal bacterial metabolites and their relative abundance is not restricted to the gut only but has also been reported in the liver and brain. Gut microbes also play a critical role in mediating brain function and, subsequently, behavior. Alcohol-induced intestinal microbiome imbalance induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), perpetuating the effects of alcohol on normal brain functioning (Banks et al. 2015). The unfiltered intestinal bacteria and bacterial endotoxins from the leaky gut interact with the brain via vagal afferents. Previous studies have attempted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of intestinal bacterial endotoxins and their role in brain-related disorders via the enteric nervous system and various metabolic pathways. Gut microbes can enter the BBB and communicate with the CNS and the enteric nervous system via vagal nerves that innervate the gastrointestinal tract. (Forsythe et al. 2014).

Alcohol, Gut-Inflammation-Induced Brain Atrophies

Alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis can have detrimental effects on brain regions like the thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids (BAs) are the primary intestinal bacterial metabolites that may modulate BBB by disrupting tight junctions. This bacterial and bacterial endotoxin translocation in the brain profoundly affects the brain's normal functioning. Studies have reported that alcohol-induced gut-derived bacterial metabolites can induce inflammation and directly influence neuronal activity in the hypothalamus and CNS (Stilling et al. 2014). The translocation of bacterial metabolites to the brain has been mechanistically correlated to impaired cognitive functions and dysregulations. Alcohol-mediated gut-derived systemic inflammation may affect brain plasticity and result in brain-related disorders like autonomic disturbances, symptoms like depression and alcohol withdrawal (Retson et al. 2015).

Reports suggest that alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis and imbalance in gut microbiota may result in the modifications of the vagal nerve, increasing neuroinflammation that may result in alcohol-associated behavioral disturbances and anxiety-like symptoms (Gorky et al. 2016). Alcohol-induced translocation of bacterial metabolites into the bloodstream and then to the brain can result in dysregulation of brain plasticity and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) responsiveness. Reports have correlated the intestinal microbiome to dysregulations in the HPA axis by demonstrating that the intestinal microbiome affected the postnatal development of the HPA stress response (Sudo et al. 2004). Previous studies have shown that gut-derived bacterial metabolites are related to the severity of psychological symptoms like depression and anxiety in patients with AUD (Leclercq et al. 2014b). These gut microbiota-mediated dysregulations in the brain may persist because of circadian mechanisms that regulate gut-brain interactions. Alcohol consumption could lead to disruptions in circadian rhythm that exacerbate alcohol-related gut leakiness and related brain disorders (Forsyth et al. 2015).

Previous evidence suggests a correlation between neuropsychiatric disorders and specific inflammation-mediated cognitive dysfunctions, including depression and dementia. AUD may also lead to prolonged liver dysfunction, leading to a potentially fatal brain disorder known as hepatic encephalopathy (HE). People with HE suffer from erratic sleep patterns, severe cognitive and motor dysfunctions, including flapping tremors of hands called asterixis (Rose et al. 2020). The gut-brain axis also serves as an essential connection between related liver disorders and hepatic encephalopathy in AUDs. In one such study, intestinal gut bacterial metabolites mediated hepatic encephalopathy (HE) correlated with cognitive dysfunctions following alcohol consumption (Bajaj et al. 2012). Patients with AUD-mediated HE also have characteristic changes in supporting cells like astrocytes (nuclei are enlarged and glassy-looking) other than typical neuronal damage (Jaeger et al. 2019). Alcohol-mediated liver dysfunction like HE results in impaired ammonia clearance produced by the intestinal microbiota. This impairment results in elevated levels of circulating ammonia which can cross BBB and may result in a cascade of neurological events leading to dysregulation of brain functions in alcoholic cirrhosis (Häussinger et al. 2000).

Ahluwalia et al. observed significant cortical damage, elevated ammonia levels, and lower brain reserve in alcohol cirrhosis patients (Ahluwalia et al. 2015). In another similar study, the relative abundance of gut bacterial microbiota like Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Lactobacillaceae positively correlated with altered neuronal integrity, oedema and hyperammonemia-related astrocyte dysfunction (Ahluwalia et al. 2016). Chronic alcohol intoxication induces a microbial imbalance in the gut, leading to dysregulation of vagal signaling, which causes neuroinflammation in the brain. Moreover, alcohol-induced intestinal dysbiosis may directly result in neuroinflammation in the brain or nutritional deficiencies impairing brain functions. Alcohol-induced chronic liver disease mediated by infiltrated bacterial metabolites has increased ammonia levels and decreased thiamine concentrations. These dysregulations reduce the activity of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, resulting in mitochondrial oxidative deficits and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain (Ahluwalia et al. 2016).

These poor brain reserves in alcoholic cirrhosis could further increase the patient's vulnerability towards further deterioration. Intriguing evidence suggests intestinal microbiota modulatory treatment with probiotics, fecal transplant, and abstinence from alcohol ameliorates cognitive dysfunctions and other brain-related disorders. For example, alcohol withdrawal in AUD patients improved cognitive functions by decreasing the levels of LPS in the gut and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain (Leclercq et al. 2012). Stimulation of the vagal nerve reduces gut-derived LPS-induced systemic and brain-specific inflammation as well as a decline in cognitive impairments. This strategy could be a novel approach to modulating the gut–brain axis at nerve interfaces affecting cognitive functions.

Alcohol-Induced Neurodegeneration

Despite being a hot topic, alcoholism and related diseases are impossible to study due to the variability in age of onset, duration, amount and pattern of alcohol consumption in humans. In this regard, animal models have provided a framework for manipulating and controlling these variables to understand the consequences and mechanisms of different alcoholism patterns systematically. Acute alcoholism, as modeled by single overdose administration of alcohol, profoundly increases neuronal necrosis, activates astrocytes and microglial cells, and attenuates oligodendrocytes and, ultimately, cognitive and motor deficits (Novier et al. 2013). Sub-chronic alcohol damage, modeled by 4-day binge ethanol exposure, also triggers microglial activation, oxidative stress, synaptic ultrastructure impairment and significant neuronal death (Zhao et al. 2013). The alcoholism pattern often encountered in human beings is chronic exposure to intermittent ethanol coinciding with long-term drinking habits. As reported in various studies, chronic alcoholism leads to neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and anxiety-related behavioral injury accompanied by other signs of mental disorders and dementia (Lippai et al. 2013b).

In alcohol-induced brain damage, neuronal loss does not account for complete volume loss of the brain, and instead, glial cells do contribute a lot in leaving a void in the alcoholic brain. Comparatively, glial cells are more sensitive to alcohol than neurons (Santos et al. 2013). Previous studies have found a significant loss of the glial cells in the post-mortem human hippocampus of alcoholics (Santos et al. 2013). An in vitro study on astrocyte culture has been shown acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol, to be highly toxic to astrocytes (Holownia et al. 1999). Additionally, rodent studies demonstrate that long-term alcohol exposure significantly reduces glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the cerebellum, a characteristic of the astrocytic population (Rintala et al. 2001). On the contrary, some studies also refute this observation of glial sensitivity to alcohol by reporting no such effect on the glial population (Fabricius et al. 2007). Findings seem to be more complicated with the concept of reactive gliosis, which suggests that in response to damage stimuli like alcohol exposure, glial cells tend to increase more in number to counter the stress signals (Gonca et al. 2005). Thus, the role of glial cells is dynamic in alcoholism which needs to be further delineated.

Numerous studies have reported excessive alcohol consumption as a major risk factor for neurocognitive impairment and neurodegenerative disorders such as dementia and Parkinson's disease (de la Monte 2014). Here, we have provided a brief account of the interplay between alcohol intake and neurodegenerative diseases.

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a complex neurological outcome of aberrantly aggregated amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. Studies on human samples have associated alcohol intake with an increased risk of developing AD and worsening cognitive deficits in AD patients (Venkataraman et al. 2017). Based on a retrospective cohort study in France (2008–2013), out of 57,353 patients with AUD, 38.9% were diagnosed with early-onset dementia, suggesting alcohol as the most potent modifiable risk factor for the onset of dementia (Schwarzinger et al. 2018). Findings from several preclinical studies have also established associations between alcohol consumption and AD. Chronic intragastric alcohol administration in adult rats induced spatial reference memory and memory consolidation deficits. Further, these cognitive alterations are accompanied by increased expression of hyperphosphorylated tau and its up-regulators like GSK-3β, MDA and Cdk5 in the hippocampus and cortex of alcohol-exposed rats (Das et al. 2006). Similarly, few other studies have also reported increased expression of other AD biomarkers like BACE1, APP, presenilin and nicastrin in the hippocampus of rats and human neuroblastoma cells exposed to prolonged ethanol stimulation (Kim et al. 2011; Gabr et al. 2017). Gene expression analysis of microglial cells exposed to alcohol has identified that alcohol affects the expression of genes responsible for phagocytosis of Aβ peptides, thus strengthening the implications of alcohol intake on AD risk (Kalinin et al. 2018). Moreover, common dysregulations in cellular signaling mechanisms like altered Akt/mTOR pathway and increased microglial activation triggered by hyperactivated let-7/TLR7/HMGB1 signaling, evident in both alcohol exposure as well as AD background, indicate converging mechanistic associations between the two (Lehmann et al. 2012; Coleman et al. 2017). Although alcohol emerges as a risk factor for AD, few studies have also suggested alcohol protects against neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. Upon consumption at a low to moderate amount, alcoholic beverages like beer containing lower ethanolic concentration and compounds like folic acid, niacin and purine lower the Aβ burden in the brain and reduce the risk of developing AD (Kok et al. 2016).

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder primarily characterized by neurological motor deficits associated with increased dopaminergic neuronal death in the Substantia nigra region of the brain. Epidemiological studies have correlated higher liquor consumption with an increased risk of developing PD owing to the pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory events induced by a higher content of alcohol (Liu et al. 2013). In a Swedish National cohort study conducted between 1978 to 2008, out of 1083 patients with AUD, 0.4% of the patients reportedly developed PD (Eriksson et al. 2013). α-Synuclein, an essential protein responsible for the seeding Lewy body aggregation in PD, is more highly expressed in patients with chronic alcoholism than healthy controls (Bönsch et al. 2005). Like many other drugs, alcohol also reinforces the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. Although there is an increase in dopamine release at the early stages of alcoholism, chronic drinking patterns significantly damage the nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. In line with this, a preclinical study on a rat model of Parkinsonism has illustrated that rats with chronic oral intake of alcohol for 60 days had the highest dopamine depletion accompanied by the highest lipid peroxidation in comparison to rats with frequent mating or cigarette inhalation (Ambhore et al. 2012). Identical to AD, low to moderate beer consumption is also found to correlate with a lower risk of PD. However, the protective effect of beer in PD is limited to males, which is perhaps mediated by elevating the serum uric acid, a factor associated with lowering the risk of PD (Weisskopf et al. 2007).

Neuroinflammation at the Heart of Alcohol-Induced Neurodegeneration

Abnormalities in cognitive ability, motor functions, decision-making, social interactions and attention deficits are highly prominent in chronic alcoholics. As described above, neuroinflammation has served as a crucial mechanism in alcoholism-associated pathologies, including neuropathological complications. Since the 1990s, microglial activation has been suggested to play a key role in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity. Depending on the pattern of alcohol consumption, the microglial activation and associated inflammatory response vary. Acute ethanol exposure induces microglial activation, which initially prevents toxicity by imparting a neuroprotective response, but later secretes inflammatory cytokines which are neurotoxic (Ward et al. 2009). In a rat model of sub-chronic ethanol treatment simulated by a 4-day binge, alcohol triggers microglial morphological changes rather than complete microglial activation in the hippocampus. However, the partial microglial activation triggered by adolescent binge ethanol exposure persists through early adulthood (McClain et al. 2011). Alcoholic pathologies associated with chronic alcohol abuse are also believed to be mediated by microglia and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, a study has shown a low level of microglial activation after a single binge ethanol exposure. However, subsequent alcohol exposures potentiate the activated microglial response. This highlights the role of initial alcohol exposure in priming the microglia for its hyperactivation in successive exposures (Marshall et al. 2016). A study involving a mice model of chronic ethanol exposure revealed that ethanol induces persistently increased expression of brain cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1, accompanied by elevated oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Mechanistically, chronic ethanol exposure potentiates the activation of TLR3-HMGB1 signaling, which contributes to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration (Qin and Crews 2012a).

Activated microglia cause the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the generation of free radicals, thus exacerbating neuroinflammation and subsequent cell death via caspase activation (Coleman and Crews 2018). In line with this, an in vitro study revealed that treatment of neuronal cells with media of microglial cells conditioned with ethanol or LPS induces neuronal apoptosis, indicating that pro-inflammatory factors released from activated microglia cause neural impairment (Boyadjieva and Sarkar 2013; Wang et al. 2014). Another study confirmed this, wherein apoptotic neuronal death was significantly reduced upon inhibiting microglial activation (Yune et al. 2009). Evidence for the involvement of neuroinflammation in alcohol-induced neurodegeneration also stems from a study wherein repeated ethanol intoxication in Wistar rats results in robust elevation of some key neuroinflammation-related proteins like phospholipase A2 and aquaporin-4, along with expression of apoptotic inducers like PARP-1 and caspase-3 in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Tajuddin et al. 2013).

Chronic ethanol treatment induces pro-inflammatory microglial activation and neurodegeneration via activation of TLR4. Mechanistically, TLR4 on microglia is activated by HMGB1 released by neuronal cells in the presence of alcohol, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines caspases via AP-1 and NF-κB mediated signaling pathways (Crews et al. 2006). In addition, TLR deficiency by siRNA or genetic KO protects alcohol-induced neurodegenerative processes (Crews et al. 2006). TLR4 and TLR2 deficiency inhibit ethanol-induced degeneration, thus implying a crucial mediatory role of these TLRs in ethanol neurotoxicity (Fernandez-Lizarbe et al. 2013). The neuroinflammatory role of TLR-7 in neurodegeneration during alcohol exposure has also been documented in some studies. Ethanol induces the release of miRNA let-7b/HMGB1 complexes in the micro-vesicles derived from activated microglia. These let-7b/HMGB1 acts as agonists for TLR7 activation leading towards the execution of hippocampal neurotoxicity like other TLRs (Coleman et al. 2017). Recently, a study by Qin et al. in alcoholic post-mortem human cortex samples and binge alcoholic mice models has illustrated that alcohol induces a significant increase in apoptotic neurons in the brain and an increase in TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptors downstream of TLR7 activation. The same study also corroborated these findings by showing that treatment of ethanol exposed organotypic brain cultures with TRAIL-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies blocked ethanol-induced neuronal apoptosis (Qin et al. 2021).

MCP-1 and its receptor C–C chemokine receptor type-2 (CCR2) form a crucial regulator of microglial activation in neuroinflammatory responses. Analysis of human alcoholic brain samples has revealed an abnormally increased concentration of this pro-inflammatory cytokine, MCP-1, in various brain regions, including the ventral tegmental area, hippocampus, amygdala and substantia nigra (He and Crews 2008). A study by Yang et al. using neuron/microglia co-culture systems has demonstrated that neuroinflammatory responses triggered by MCP-1 require the presence of microglia. In addition, treatment of the neuron/microglial co-culture with an MCP-1-neutralizing antibody inhibited microglial activation and neuronal death, which confirmed that MCP-1 mediates its responses via microglial activation (Yang et al. 2011). A study by Qin et al. proposed that MCP-1 primes the microglia for activation during initial exposures to alcohol by lowering the threshold sensitivity of microglia, which produces an activated microglial activity during subsequent insults (Qin et al. 2008). Besides, MCP-1/CCR2 signaling has also been implicated in alcohol-stimulated neuronal deficits during development. The findings from an alcohol exposure model in third-trimester mice revealed that MCP-1 mediates neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis under alcohol treatment. Further, inhibition of MCP-1/CCR2 activity by Bindarit (inhibitor of MCP-1 synthesis) or CCR2 antagonist RS504393 significantly reduced the alcohol-induced neuronal apoptosis in the developing brain (Ren et al. 2017). In terms of mechanism, MCP-1/CCR2 interacts with several downstream molecules like GSK-3β, JNK and TLR4. Interaction of MCP-1/CCR2 with GSK-3β or JNK regulates the expression of transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1, which stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 itself. On the other hand, activation of TLR4 directly by alcohol or by interaction with MCP-1/CCR2 stimulates the activation of downstream effectors MyD88, TRIF and JNK, which again leads to excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus amplifying this neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative process in a positive feedback loop manner (Zhang and Luo 2019). Alcohol exposure also directly induces increased expression of programmed death receptor (PDR) and its cognate ligand programmed death ligand-1 (PDL-1), responsible for immunomodulation, such as Th1/Th2 imbalance. This, in turn, releases pro-inflammatory cytokines and dampens the innate immune response, leading to neurodegeneration via an exacerbated neuroinflammatory response (Mishra et al. 2020).

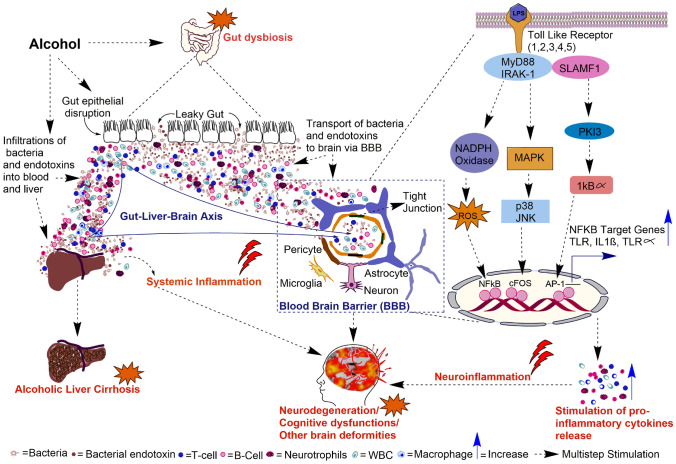

Neuroinflammation as a Potential Target for Alcohol-Induced Neurodegeneration

Neuroinflammation, being one of the early drivers of neurodegeneration during alcohol intoxication, has gained a lot of attention for its potential therapeutic target. In the last few decades, numerous attempts to target neuroinflammation for halting alcohol-induced neuropathological complications have served promising outcomes. Cannabidiol, an anti-inflammatory drug used for neuropsychiatric disorders, has been found to have beneficial effects on early alcohol exposure. Treatment with cannabidiol following prenatal and lactation alcohol exposure to mice offspring was found to ameliorate cognitive deficits and counteract neuroinflammatory responses triggered by early alcohol exposure (García-Baos et al. 2021). Ethanol-induced early brain neurotoxicity are also reportedly rescued by an acute dose of melatonin and Vitamin-C by abrogating ethanol-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the developing brains of rat pups (Ahmad et al. 2016; Ali et al. 2018). Previous studies have shown that alcohol exposure liberates neuroinflammatory ω-6 arachidonic acid in the brain via elevated expression levels of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and cPLA2. A study by Kouzoukas et al. revealed that treatment of alcohol-exposed adult rats with PARP inhibitor veliparib prevented alcohol-induced neurodegeneration in the ventral hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Kouzoukas et al. 2019). Natural dietary supplementation with compounds like curcumin and docosahexaenoic acid also protects against ethanol-induced neurodegeneration by suppressing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in an Nrf2/TLR4/RAGE signaling dependent manner and AQP4/PARP-1/PLA dependent manner, respectively (Tiwari and Chopra 2012; Tajuddin et al. 2014; Ikram et al. 2019). Co-treatment of neonatal mice with ethanol and pioglitazone exhibited a significant decrease in the expression of various cytokines and chemokines, like IL-1β, TNFα and CCL2, compared to neonatal mice treated only with alcohol (Drew et al. 2015). Pioglitazone rescued alcohol-induced neuronal and cognitive degeneration via suppression of suppression neuroinflammatory responses (Cippitelli et al. 2017). Minocycline, an antibiotic and inhibitor of microglial activation, is reported to protect neurons against ethanol exposure in a mice model of FASD. Minocycline reverses alcohol-induced damages by inhibiting caspase-3 activation, possibly through alleviating GSK-3β mediated neuroinflammation (Wang et al. 2018). In an in vitro study using human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y, it was observed that co-treatment of ethanol and glycine inhibits the expression of phosphorylated NF-κB and apoptosis marker caspase-3. Further, the same study confirmed these findings in 7-day-old male rat pups, wherein co-treatment with glycine lowered the ethanol-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, ROS production and associated neurodegeneration (Amin et al. 2016). In a recent study, in vivo treatment with benzimidazole, a compound containing acetamide derivatives, ameliorates ethanol-induced neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration, as demonstrated by improved cognitive function and suppressed expression of NF-κB, COX-2, and oxidative enzymes (Imran et al. 2020). Obestatin, a ghrelin associated peptide, has also exhibited protective effects by inhibiting neuronal apoptosis and neuroinflammation in a rat model of FASD (Toosi et al. 2019). The role of alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis followed by subsequent systemic/neuroinflammation and resulting neurodegeneration, cognitive dysfunctions and other brain-related deficits are given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Systematic representation of alcohol-induced inflammation-mediated gut dysbiosis, liver cirrhosis, neurodegeneration, and other brain deformities. Alcohol intoxication results in disruption of the gut epithelial barrier, which causes a leaky gut. This leakage results in the infiltration of bacteria and bacterial endotoxins into the blood circulation resulting in systemic inflammation. The bacteria and endotoxins like Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) cross the blood–brain barrier and activate Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascades. Stimulation of TLRs downstream activation of the transcription factors that induce pro-inflammatory gene expressions, neuroinflammation and neuronal death

Alcohol, Neural Stem Cells and Adult Neurogenesis

Functional Significance of Adult Neurogenesis

Adult neurogenesis occurs constitutively in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles and sub granular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) (Altman and Das 1965; Anand and Mondal 2017). It plays a significant role in hippocampal integrity and function (Bergmann et al. 2012; Toda et al. 2019). New neurons are constitutively being generated in the DG throughout life. The new neurons originate from the radial glia, like adult stem cells residing within the SGZ of DG (Zhao et al. 2008; Zhao and Moore 2018). Adult neurogenesis in the DG contributes to approximately 6% of the granular cell layer mass per month (Cameron and McKay 2001). But the functional role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis is poorly understood. In the past, the function of adult neurogenesis has been studied using the conditional and inducible transgenic animal models (Clelland et al. 2009; Nakashiba et al. 2012), revealing that hippocampal adult neurogenesis plays an important role in differentiating between similar experiences, a process known as pattern recognition (Clelland et al. 2009; Nakashiba et al. 2012). Spatial memory is also affected in the inducible KO and lentiviral transgene delivery models (Marín-Burgin and Schinder 2012). Decreased neurogenesis resulted in a prolonged hippocampal-dependent period of associative fear memory and increased neurogenesis inversely elevated the decay rate of HPC dependency of memory, without loss of memory in adult rodents (Kitamura et al. 2009). These findings suggest that adult hippocampal neurogenesis modulate the hippocampal-dependent period of memory. However, in contrast, some studies suggest that adult neurogenesis may also be related to forgetting memory during infancy and adulthood (Weisz and Argibay 2009; Akers et al. 2014; Epp et al. 2016; López-Oropeza et al. 2022). Often but not always the disruption of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus leads to impairment of contextual fear conditioning and spatial memory (Clelland et al. 2009; Drew et al. 2010), the enhancement of adult neurogenesis improves spatial memory and pattern separation (Sahay et al. 2011; Yook et al. 2016). In contrast, adult neurogenesis may also degrade previously acquired memory traces (Arruda-Carvalho et al. 2011). Nevertheless, these evidences suggest a vital role of adult neurogenesis in hippocampal-dependent behavior. Adult neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb is associated with odour interpretation and may thus influence behaviors governed by odour recognition, such as sexual behavior in rodents (Keller et al. 2006; Ishii and Touhara 2019).

In this section, we have discussed the effect of alcohol consumption on adult neurogenesis.

Effects of Alcohol Intoxication on Neural Stem Cells

The neuropathology associated with alcohol consumption has been mainly attributed to the death of neurons following alcohol exposure (Tateno and Saito 2008). However, a developing perception suggests that impairment of adult neurogenesis may, at least in part, contribute to alcohol-associated neuropathology (Geil et al. 2014). During adult neurogenesis, the neural stem cells (NSCs) have to go through four different stages: cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival (Geil et al. 2014). Theoretically, alcohol exposure may affect one or more of these stages (Geil et al. 2014). At the same time, the different stages of adult neurogenesis may be differentially modulated by alcohol intoxication, alcohol dependence and the aftereffects of alcohol exposure (Geil et al. 2014). Alcohol intoxication leads to an overall decrease in adult neurogenesis by affecting NSC proliferation and newborn neuron survival (Crews and Nixon 2009; Richardson et al. 2009). NSC proliferation is decreased in a concentration-dependent manner by alcohol intoxication in the brain of adolescents and adult mammals, including humans (Crews et al. 2006; Richardson et al. 2009; Golub et al. 2015; Le Maître et al. 2018). On the other hand, abstinence from alcohol following alcohol dependence leads to the recovery of hippocampal mass and hippocampus-dependent cognitive functions, apparently due to enhanced adult neurogenesis (Hoefer et al. 2014; Zou et al. 2018; Toda et al. 2019; Nawarawong et al. 2021). In the SGZ region, the proliferation of NSCs increases after one week of abstinence (Nixon and Crews 2004; Hayes et al. 2018). As a result, the number of newborn neurons increases significantly in the SGZ region around 14 days after the cessation of binge alcohol consumption (Nixon and Crews 2004; Hayes et al. 2018; Nawarawong et al. 2021). Interestingly, the proliferation of NSCs comes back to the baseline level about two weeks after the last ethanol exposure (Nixon et al. 2008). This indicates that the reactive neurogenesis after abstinence from alcohol may have a transient nature. Prolonged exposure consumption resulted in transient suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis and long-lasting in the SVZ forebrain of rats (Hansson et al. 2010). The extent to which each stage of adult neurogenesis is affected by alcohol intoxication may depend on multiple factors: the dose of alcohol, its exposure pattern, and the animal subjects' age (Goodlett et al. 2005; Nixon 2006).

Interplay Between Neuroinflammation and NSC Activity

Not much is known about the mechanisms by which alcohol intoxication affects adult neurogenesis. Alcohol-induced inflammation may be a potential mechanism by which alcohol exerts its effects on NSC proliferation and neuronal survival. Inflammation in a particular tissue disturbs its homeostatic state, affecting nearby cells. Alcohol-induced inflammation is no exception. Therefore, it is highly probable that alcohol-induced inflammation may target the NSCs in the brain and alter their activity. Apart from the intrinsic regulatory mechanisms, stem cell activity is also modulated by extrinsic cues such as inflammation. Previous studies have shown that in non-neural tissues, inflammation negatively affects tissue restoration (Mourkioti and Rosenthal 2005; Keshav 2006; Rigby et al. 2007; Koning et al. 2013). Hence, elucidating the connection between inflammation and NSC activity is necessary to understand how the NSCs respond to alcohol intoxication.

Previous studies have demonstrated a close link between inflammation and neurogenesis (Whitney et al. 2009). Inflammation in the brain is executed by specialized glial cells like microglia, which have been shown to influence NSC activity and neurogenesis (Whitney et al. 2009). The initial studies focusing on the intimacy of inflammation and NSCs demonstrated that inflammation might disturb the neurophysiological attributes of NSCs and the cells derived from them, as is evident from the attenuation of demyelination in various regions of the brain of a murine model of multiple sclerosis and autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Einstein et al. 2002; Pluchino et al. 2003). The precise effect of inflammation on NSC activity could not be determined because of the dual nature of inflammation: it is both beneficial and detrimental (Crutcher et al. 2006; Kyritsis et al. 2014). It may imply that the interaction between inflammation and NSCs is context-dependent. During high levels of inflammation, phagocytic microglia have been shown to affect neurogenesis negatively (Monje et al. 2003). On the contrary, activated microglia increase NSC proliferation and promoted neurogenesis (Battista et al. 2006; Butovsky et al. 2006; Ziv et al. 2006).

Several studies have demonstrated the negative regulation of NSCs by inflammation. In the mouse model, chronic immunosuppression increases the number of newborn neurons in the DG (Liu et al. 2007). Similarly, cell proliferation is significantly increased in the DG, and the number of newborn neurons is elevated in the SGZ region of TNFR1 null mice (Iosif et al. 2006). This indicates that TNF-α, a well-known pro-inflammatory cytokine, may have an inhibitory effect on NSC activity. Another pro-inflammatory cytokine, IFN-γ, has been demonstrated to hamper the proliferative potential of NSCs through STAT-1 signaling (Ben-Hur et al. 2003a; Mäkelä et al. 2010). Previous studies have also reported the potential role of the complement system in suppressing NSC activity, as is evident from increased basal adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus of Complement receptor 2 (Cr2) null mice (Moriyama et al. 2011). Interestingly, after an injury in the rodent brain, the NSCs in the SVZ region react to brain damage by increasing their proliferation, but reactive neurogenesis does not occur (Ben-Hur et al. 2003b). One of the reasons behind this phenomenon could be the maintenance of the undifferentiated proliferative state of the NSCs of the SVZ region by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Perez-Asensio et al. 2013). Leukotriene, an arachidonic acid metabolite, has also been implicated in the negative regulation of NSC activity. This is evident from the fact that antagonism of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 increases NSC proliferation in cultured rat neurospheres (Huber et al. 2011). It is believed that suppression of NSC activity and adult neurogenesis by inflammation may be one of the underlying causes of neurodegenerative diseases (Glass et al. 2010). Alcohol has detrimental effects on levels of neurotransmitters, their receptors and ion channels in CNS. The prime pharmacodynamic targets for alcohol include GABA and glutamate which exhibit excitatory effects during the development of new neurons (Geil et al. 2014). This suggests that alcohol may modulate neurogenesis by influencing the levels of these neurotransmitters. Alcohol may also influence neurogenesis by regulating cAMP-responsive element binding (CREB) protein and its downstream effector molecules like neuropeptide Y (NPY) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) that promote adult neurogenesis (Malva et al. 2012). Also, alcohol may activate microglia and directly affect the neurogenic niche and therefore, neurogenesis (Marshall et al. 2013).

Inflammation enhances the transplantation efficiency of NSC grafts in a mouse model (Park et al. 2009; Mathieu et al. 2010). When presented with tissue cytokines, grafted NSCs can migrate to the site and activate the CCR2 signaling cascade (Belmadani et al. 2006). Inflammation milieu may also play a key role in neuroblast migration, as evident from the deficiency of migration of NSCs observed in the MCP1 knockout mice model (Belmadani et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2007). Similarly, stromal cell-derived inflammatory chemoattractant SDF1/CXCR4 signaling serves as an essential element for migration of NSCs to the brain areas affected by injury or neurodegeneration (Imitola et al. 2004; Widera et al. 2006). Inflammation also promotes the proliferation of NSCs both in vivo (Pluchino et al. 2003; Wolf et al. 2009) and in vitro (Widera et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2007) models. In some instances, such as in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model, chronic inflammation may be a fate determinant for NSCs (Covacu et al. 2014). Some reports also suggest a protective effect of inflammatory cells on NSCs by systematically resolving acute inflammation (Schwartz et al. 2013; Schwartz and Baruch 2014).

In addition, alcohol consumption also causes chronic thiamine deficiency called Korsakoff syndrome, resulting in confabulations behavior and false memories due to a deficit in source memory and executive functioning (Kessels et al. 2008). In such syndrome, alcohol consumption causes thiamine deficiency by impairing its absorption in the duodenum, leading to inadequate production of energy for brain cell functioning, impairing memory, damaging the communication between the hippocampus and the mammillary nuclei, a core connection within the Papez circuit (Wang et al. 2020).

As described in this review, alcohol intoxication induces inflammation, and theoretically, inflammation may alter the activity and survival of NSCs, thereby affecting the process of adult neurogenesis (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, studies reporting the direct effect of alcohol-induced inflammation on NSCs are scarce. Also, studies focusing on microglia activation by alcohol intoxication are limited (Crews et al. 2006b; Nixon et al. 2008) and therefore, the precise role of alcohol-induced inflammation in modulating adult NSCs has not been established. Although inflammation has been reported in animal models of alcohol exposure (Pascual et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2008), microglia activation evidence is (Qin and Crews 2012b). Historically, it has been suggested that brain damage in chronic alcohol exposure is too low to account for significant changes in the activation state of microglia (Kalehua et al. 1992). However, excessive consumption of alcohol has been shown to enhance inflammation significantly and the involvement of activated microglia is highly probable (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proposed mechanism of alcohol-mediated inhibition of NSC activity. Adult neurogenesis occurs in several steps, namely proliferation of NSCs, migration of neuroblasts and differentiation into new neurons. If the new neurons survive, they are integrated into the existing neural circuitry. Alcohol is known to negatively affect NSCs proliferation and new neuron survival. Here, we propose that alcohol may exert its effects by activation of microglia and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, both of which are known to inhibit NSCs proliferation

Conclusion

Alcohol consumption causes several detrimental effects on the nervous system. These effects can be direct or indirect (through the gut–brain axis). But in any case, neuroinflammation seems to have a critical mechanistic role in executing alcohol-associated pathology. Alcohol consumption may result in neurodegeneration in different brain parts, including the hippocampus, and negatively regulates adult NSCs. Emerging theories suggest an essential contribution to adult neurogenesis disruption in alcohol-mediated neurodegeneration and hippocampal shrinkage. We propose targeting neuroinflammation to design therapies against alcohol intoxication and associated brain anomalies. However, that may require a thorough understanding of the role of inflammation in alcohol pathogenicity. Hence deeper investigation of the molecular mechanisms and regulatory pathways associated with alcohol-induced inflammation is warranted.

Acknowledgements

ACM acknowledges the financial supports from DBT (Grant No. BT/PR32907/MED/122/227/2019), DBT-BUILDER (Level-III) and DST-FIST-II to School of Life Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. SKA acknowledges the financial support from CSIR-HRDG, (Grant No. 09/263(1101)/2016-EMR-I) New Delhi. MHA acknowledges the financial support from ICMR-SRF (Grant No. 45/7/2019/MP/BMS) New Delhi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SKA, MHA, MRS, RS, ACM; Writing-Original draft preparation: SKA, MHA, MRS, RS; Writing-Review and editing: SKA, MHA, MRS, RS, ACM; Supervision: ACM.

Funding

Funding from DBT (BT/PR32907/MED/122/227/2019), CSIR-HRDG, (09/263(1101)/2016-EMR-I) and ICMR-SRF (45/7/2019/MP/BMS).

Data Availability

No data and material are available as it is a review article.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

No ethical approval is required as no data were generated and used in the review.

Consent for Publication

All the authors have consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahluwalia V, Wade JB, Moeller FG, White MB, Unser AB, Gavis EA, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Sanyal AJ, Siddiqui MS, Puri P, Luketic V, Heuman DM, Fuchs M, Matherly S, Bajaj JS (2015) The etiology of cirrhosis is a strong determinant of brain reserve: a multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study. Liver Transpl 21(9):1123–1132. 10.1002/lt.24163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia V, Betrapally NS, Hylemon PB, White MB, Gillevet PM, Unser AB, Fagan A, Daita K, Heuman DM, Zhou H, Sikaroodi M, Bajaj JS (2016) Impaired gut–liver-brain axis in patients with cirrhosis. Sci Rep 26(6):26800. 10.1038/srep26800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Shah SA, Badshah H, Kim MJ, Ali T, Yoon GH, Kim TH, Abid NB, Rehman SU, Khan S, Kim MO (2016) Neuroprotection by vitamin C against ethanol-induced neuroinflammation associated neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 15(3):360–370. 10.2174/1871527315666151110130139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang HL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, Ohira K, Richards BA, Miyakawa T, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 344(6184):598–602. 10.1126/science.1248903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Loeches S, Pascual-Lucas M, Blanco AM, Sanchez-Vera I, Guerri C (2010) Pivotal role of TLR4 receptors in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and brain damage. J Neurosci 30(24):8285–8295. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Loeches S, Ureña-Peralta JR, Morillo-Bargues MJ, Oliver-De La Cruz J, Guerri C (2014) Role of mitochondria ROS generation in ethanol-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death in astroglial cells. Front Cell Neurosci 8:216. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali T, Rehman SU, Shah FA, Kim MO (2018) Acute dose of melatonin via Nrf2 dependently prevents acute ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in the developing rodent brain. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):119. 10.1186/s12974-018-1157-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD (1965) Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol 124(3):319–335. 10.1002/cne.901240303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambhore N, Antony S, Mali J, Kanhed A, Bhalerao A, Bhojraj S (2012) Pharmacological and biochemical interventions of cigarette smoke, alcohol, and sexual mating frequency on idiopathic rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Young Pharm 4(3):177–183. 10.4103/0975-1483.100026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin FU, Shah SA, Kim MO (2016) Glycine inhibits ethanol-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and apoptotic neurodegeneration in postnatal rat brain. Neurochem Int 96:1–12. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand SK, Mondal AC (2017) Cellular and molecular attributes of neural stem cell niches in adult zebrafish brain. Dev Neurobiol 77(10):1188–1205. 10.1002/dneu.2250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Sakaguchi M, Akers KG, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2011) Posttraining ablation of adult-generated neurons degrades previously acquired memories. J Neurosci 31(42):15113–15127. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj JS (2019) Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16(4):235–246. 10.1038/s41575-018-0099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj JS, Ridlon JM, Hylemon PB, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, Smith S, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM (2012) Linkage of gut microbiome with cognition in hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302(1):G168–G175. 10.1152/ajpgi.00190.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banan A, Keshavarzian A, Zhang L, Shaikh M, Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Fields JZ (2007) NF-kappaB activation as a key mechanism in ethanol-induced disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton and monolayer barrier integrity in intestinal epithelium. Alcohol 41(6):447–460. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Gray AM, Erickson MA, Salameh TS, Damodarasamy M, Sheibani N, Meabon JS, Wing EE, Morofuji Y, Cook DG, Reed MJ (2015) Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood–brain barrier disruption: roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J Neuroinflamm 25(12):223. 10.1186/s12974-015-0434-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baradaran Z, Vakilian A, Zare M, Hashemzehi M, Hosseini M, Dinpanah H, Beheshti F (2021) Metformin improved memory impairment caused by chronic ethanol consumption during adolescent to adult period of rats: role of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Behav Brain Res 6(411):113399. 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista D, Ferrari CC, Gage FH, Pitossi FJ (2006) Neurogenic niche modulation by activated microglia: transforming growth factor beta increases neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci 23(1):83–93. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmadani A, Tran PB, Ren D, Miller RJ (2006) Chemokines regulate the migration of neural progenitors to sites of neuroinflammation. J Neurosci 26(12):3182–3191. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0156-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Ben-Menachem O, Reinhartz E, Karussis D, Abramsky O (2003a) Transplanted multipotential neural precursor cells migrate into the inflamed white matter in response to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Glia 41(1):73–80. 10.1002/glia.10159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Ben-Menachem O, Furer V, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Grigoriadis N (2003b) Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 24(3):623–631. 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann O, Liebl J, Bernard S, Alkass K, Yeung MS, Steier P, Kutschera W, Johnson L, Landén M, Druid H, Spalding KL, Frisén J (2012) The age of olfactory bulb neurons in humans. Neuron 74(4):634–639. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola A, Mathews S, Ki SH, Wang H, Gao B (2013) Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model). Nat Protoc 8(3):627–637. 10.1038/nprot.2013.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bönsch D, Greifenberg V, Bayerlein K, Biermann T, Reulbach U, Hillemacher T, Kornhuber J, Bleich S (2005) Alpha-synuclein protein levels are increased in alcoholic patients and are linked to craving. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29(5):763–765. 10.1097/01.alc.0000164360.43907.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK (2013) Microglia play a role in ethanol-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in developing hypothalamic neurons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37(2):252–262. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01889.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler M, Mann K (2011) Alcohol and the human brain: a systematic review of different neuroimaging methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35(10):1771–1793. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, Landa G, Talpalar AE, Pluchino S, Martino G, Schwartz M (2006) Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 31(1):149–160. 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McKay RD (2001) Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol 435(4):406–417. 10.1002/cne.1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon AR, Hammer AM, Choudhry MA (2018) Alcohol, inflammation, and depression: the gut–brain axis. Inflammation and immunity in depression. Academic Press, Boca Raton, pp 509–524 [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi A, Rao G, Praharaj SK, Guruprasad KP, Pais V (2020) Reduced serum levels of cluster of differentiation 200 in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Alcohol 55(4):391–394. 10.1093/alcalc/agaa033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cippitelli A, Domi E, Ubaldi M, Douglas JC, Li HW, Demopulos G, Gaitanaris G, Roberto M, Drew PD, Kane CJM, Ciccocioppo R (2017) Protection against alcohol-induced neuronal and cognitive damage by the PPARγ receptor agonist pioglitazone. Brain Behav Immun 64:320–329. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clelland CD, Choi M, Romberg C, Clemenson GD Jr, Fragniere A, Tyers P, Jessberger S, Saksida LM, Barker RA, Gage FH, Bussey TJ (2009) A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science 325(5937):210–213. 10.1126/science.1173215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG Jr, Crews FT (2018) Innate immune signaling and alcohol use disorders. Handb Exp Pharmacol 248:369–396. 10.1007/164_2018_92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG Jr, Zou J, Crews FT (2017) Microglial-derived miRNA let-7 and HMGB1 contribute to ethanol-induced neurotoxicity via TLR7. J Neuroinflammation 14(1):22. 10.1186/s12974-017-0799-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covacu R, Perez Estrada C, Arvidsson L, Svensson M, Brundin L (2014) Change of fate commitment in adult neural progenitor cells subjected to chronic inflammation. J Neurosci 34(35):11571–11582. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0231-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Nixon K (2009) Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and regeneration in alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol (oxford, Oxfordshire) 44(2):115–127. 10.1093/alcalc/agn079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Vetreno RP (2014) Chapter Ten-Neuroimmune basis of alcoholic brain damage. In: Cui C, Shurtleff D, Harris RA (eds) International review of neurobiology, vol 118. Academic Press, Boca Raton, pp 315–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Mdzinarishvili A, Kim D, He J, Nixon K (2006) Neurogenesis in adolescent brain is potently inhibited by ethanol. Neuroscience 137(2):437–445. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Bechara R, Brown LA, Guidot DM, Mandrekar P, Oak S, Qin L, Szabo G, Wheeler M, Zou J (2006) Cytokines and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30(4):720–730. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Zou J, Coleman LG Jr (2021) Extracellular microvesicles promote microglia-mediated pro-inflammatory responses to ethanol. J Neurosci Res 99(8):1940–1956. 10.1002/jnr.24813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutcher KA, Gendelman HE, Kipnis J, Perez-Polo JR, Perry VH, Popovich PG, Weaver LC (2006) Debate: “Is increasing neuroinflammation beneficial for neural repair?” J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 1(3):195–211. 10.1007/s11481-006-9021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J et al (2006) 2-Aminothiazole as a novel kinase inhibitor template. Structure–activity relationship studies toward the discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methylphenyl)-2-[[6-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl)]-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinyl] amino)]-1, 3-thiazole-5-carboxamide (dasatinib, BMS-354825) as a potent pan-Src kinase inhibitor. J Med Chem 49(23):6819–6832. 10.1021/jm060727j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis L, Halikere A, McGowan H, Moore JC, Tischfield JA, Hart RP, Pang ZP (2016) Ethanol-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in iPS cells and iPS cells-derived neural progenitor cells. Mol Brain 9(1):51. 10.1186/s13041-016-0221-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Monte SM, Kril JJ (2014) Human alcohol-related neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol 127(1):71–90. 10.1007/s00401-013-1233-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew MR, Denny CA, Hen R (2010) Arrest of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice impairs single-but not multiple-trial contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci 124(4):446–454. 10.1037/a0020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew PD, Johnson JW, Douglas JC, Phelan KD, Kane CJ (2015) Pioglitazone blocks ethanol induction of microglial activation and immune responses in the hippocampus, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex in a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(3):445–454. 10.1111/acer.12639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein O, Kol R, Reinhartz E, Ben-Menachem O, Karussis D, Abramsky O, Ben-Hur T (2002) Transplanted neural precursor cells migrate into the inflamed white matter in response to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Wiley, New York, pp S89–S89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A (2015) The gastrointestinal microbiome: alcohol effects on the composition of intestinal microbiota. Alcohol Res 37(2):223–236 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp JR, Silva Mera R, Köhler S, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2016) Neurogenesis-mediated forgetting minimizes proactive interference. Nat Commun 26(7):10838. 10.1038/ncomms10838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson AK, Löfving S, Callaghan RC, Allebeck P (2013) Alcohol use disorders and risk of Parkinson’s disease: findings from a Swedish national cohort study 1972–2008. BMC Neurol 5(13):190. 10.1186/1471-2377-13-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K, Pakkenberg H, Pakkenberg B (2007) No changes in neocortical cell volumes or glial cell numbers in chronic alcoholic subjects compared to control subjects. Alcohol Alcohol 42(5):400–406. 10.1093/alcalc/agm007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lizarbe S, Montesinos J, Guerri C (2013) Ethanol induces TLR4/TLR2 association, triggering an inflammatory response in microglial cells. J Neurochem 126(2):261–273. 10.1111/jnc.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Voigt RM, Burgess HJ, Swanson GR, Keshavarzian A (2015) Circadian rhythms, alcohol and gut interactions. Alcohol 49(4):389–398. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P, Bienenstock J, Kunze WA (2014) Vagal pathways for microbiome–brain–gut axis communication. Adv Exp Med Biol 817:115–133. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabr AA, Lee HJ, Onphachanh X, Jung YH, Kim JS, Chae CW, Han HJ (2017) Ethanol-induced PGE2 up-regulates Aβ production through PKA/CREB signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1863(11):2942–2953. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Baos A, Puig-Reyne X, García-Algar Ó, Valverde O (2021) Cannabidiol attenuates cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation induced by early alcohol exposure in a mice model. Biomed Pharmacother 141:111813. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geil CR, Hayes DM, McClain JA, Liput DJ, Marshall SA, Chen KY, Nixon K (2014) Alcohol and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: promiscuous drug, wanton effects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 3(54):103–113. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SS et al (2020) Intestinal barrier function and metabolic/liver diseases. Liver Res 4(2):81–87. 10.1016/j.livres.2020.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH (2010) Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell 140(6):918–934. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub HM, Zhou QG, Zucker H, McMullen MR, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Ro EJ, Nagy LE, Suh H (2015) Chronic alcohol exposure is associated with decreased neurogenesis, aberrant integration of newborn neurons, and cognitive dysfunction in female mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(10):1967–1977. 10.1111/acer.12843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez GI, Falcon RV, Maturana CJ, Labra VC, Salgado N, Rojas CA, Oyarzun JE, Cerpa W, Quintanilla RA, Orellana JA (2018) Heavy alcohol exposure activates astroglial hemichannels and pannexons in the hippocampus of adolescent rats: effects on neuroinflammation and astrocyte arborization. Front Cell Neurosci 4(12):472. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonca S, Filiz S, Dalçik C, Yardimoğlu M, Dalçik H, Yazir Y, Erden BF (2005) Effects of chronic ethanol treatment on glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in adult rat optic nerve: an immunocytochemical study. Cell Biol Int 29(2):169–172. 10.1016/j.cellbi.2004.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Horn KH, Zhou FC (2005) Alcohol teratogenesis: mechanisms of damage and strategies for intervention. Exp Biol Med (maywood) 230(6):394–406. 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorky J, Schwaber J (2016) The role of the gut–brain axis in alcohol use disorders. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 65:234–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson AC, Nixon K, Rimondini R, Damadzic R, Sommer WH, Eskay R, Crews FT, Heilig M (2010) Long-term suppression of forebrain neurogenesis and loss of neuronal progenitor cells following prolonged alcohol dependence in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 13(5):583–593. 10.1017/S1461145710000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häussinger D, Kircheis G, Fischer R, Schliess F, vom Dahl S (2000) Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: a clinical manifestation of astrocyte swelling and low-grade cerebral edema? J Hepatol 32(6):1035–1038. 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80110-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DM, Nickell CG, Chen KY, McClain JA, Heath MM, Deeny MA, Nixon K (2018) Activation of neural stem cells from quiescence drives reactive hippocampal neurogenesis after alcohol dependence. Neuropharmacology 1(133):276–288. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Crews FT (2008) Increased MCP-1 and microglia in various regions of the human alcoholic brain. Exp Neurol 210(2):349–358. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, Oh JH, Alexander LM, Huang W, Stärkel P, Ho SB, Gao B, Fiehn O, Emond P, Sokol H, van Pijkeren JP, Schnabl B (2019) Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 in intestine induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease in mice. Gut 68(8):1504–1515. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer ME, Pennington DL, Durazzo TC, Mon A, Abé C, Truran D, Hutchison KE, Meyerhoff DJ (2014) Genetic and behavioral determinants of hippocampal volume recovery during abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol 48(7):631–638. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.08.00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holownia A, Ledig M, Braszko JJ, Ménez JF (1999) Acetaldehyde cytotoxicity in cultured rat astrocytes. Brain Res 833(2):202–208. 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01529-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C, Marschallinger J, Tempfer H, Furtner T, Couillard-Despres S, Bauer HC, Rivera FJ, Aigner L (2011) Inhibition of leukotriene receptors boosts neural progenitor proliferation. Cell Physiol Biochem 28(5):793–804. 10.1159/000335793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez F, Montesinos J, Ureña-Peralta JR, Guerri C, Pascual M (2019) TLR4 participates in the transmission of ethanol-induced neuroinflammation via astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles. J Neuroinflammation 16(1):136. 10.1186/s12974-019-1529-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez F, Ureña-Peralta JR, Costa-Alba P, Torres JL, Laso FJ, Marcos M, Guerri C, Pascual M (2020) Circulating MicroRNAs in extracellular vesicles as potential biomarkers of alcohol-induced neuroinflammation in adolescence: gender differences. Int J Mol Sci 21(18):6730. 10.3390/ijms21186730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram M, Saeed K, Khan A, Muhammad T, Khan MS, Jo MG, Rehman SU, Kim MO (2019) Natural dietary supplementation of curcumin protects mice brains against ethanol-induced oxidative stress-mediated neurodegeneration and memory impairment via Nrf2/TLR4/RAGE signaling. Nutrients 11(5):1082. 10.3390/nu11051082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imitola J, Raddassi K, Park KI, Mueller FJ, Nieto M, Teng YD, Frenkel D, Li J, Sidman RL, Walsh CA, Snyder EY, Khoury SJ (2004) Directed migration of neural stem cells to sites of CNS injury by the stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha/CXC chemokine receptor 4 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(52):18117–18122. 10.1073/pnas.0408258102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]