Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the learning outcomes and educational effectiveness of social media as a continuing professional development intervention for surgeons in practice.

Background:

Social media has the potential to improve global access to educational resources and collaborative networking. However, the learning outcomes and educational effectiveness of social media as a continuing professional development (CPD) intervention are yet to be summarized.

Methods:

We searched MEDLINE and Embase databases from 1946 to 2022. We included studies that assessed the learning outcomes and educational effectiveness of social media as a CPD intervention for practicing surgeons. We excluded studies that were not original research, involved only trainees, did not evaluate educational effectiveness, or involved an in-person component. The 18-point Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) was used for quality appraisal. Learning outcomes were categorized according to Moore’s Expanded Outcomes Framework (MEOF).

Results:

A total of 830 unique studies revealed 14 studies for inclusion. The mean MERSQI score of the included studies was 9.0 ± 0.8. In total, 3227 surgeons from 105 countries and various surgical specialties were included. Twelve studies (86%) evaluated surgeons’ satisfaction (MEOF level 2), 3 studies (21%) evaluated changes in self-reported declarative or procedural knowledge (MEOF levels 3A and 3B), 1 study (7%) evaluated changes in self-reported competence (MEOF level 4), and 5 studies (36%) evaluated changes in self-reported performance in practice (MEOF level 5). No studies evaluated changes in patient or community health (MEOF levels 6 and 7).

Conclusions:

The use of social media as a CPD intervention among practicing surgeons is associated with improved self-reported declarative and procedural knowledge, self-reported competence, and self-reported performance in practice. Further research is required to assess whether social media use for CPD in surgeons is associated with improvements in higher level and objectively measured learning outcomes.

Keywords: social media, social networking, electronic learning, distance learning, remote learning, surgical education, continuing professional development, CPD, practicing surgeons

INTRODUCTION

Continuing professional development (CPD) plays a fundamental role in the improvement of surgical care. With the constant evolution of knowledge and techniques, it is necessary for practicing surgeons to keep abreast of the latest advances to maintain their competence and provide evidence-based care for patients.1 CPD encompasses a broad range of educational modalities intended to maintain professional competence and support lifelong learning.2,3 CPD has traditionally relied on conventional educational delivery methods such as conferences, workshops, courses, and journal clubs.2 The rapid adoption of social media by the healthcare sector4–6 has opened new avenues for global learning and collaboration, with unique benefits and challenges for CPD in the field of surgery. Surgeons are leveraging the power of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and other social media platforms to connect with colleagues, share challenging cases, enhance knowledge dissemination, and promote ongoing learning regardless of their geographical location.4,7

While the use of social media as a CPD educational intervention shows promise, its learning outcomes and educational effectiveness remain the subject of some controversy.7 As a CPD educational intervention, social media can offer timely and accessible educational content, facilitate peer-to-peer learning, and foster interprofessional collaboration.6,7 By serving as a forum for discussion of new or challenging cases and experiences, it also offers the opportunity for reflective practice. Unfortunately, the quality, authenticity, and accuracy of the educational content available on social media have been called into question as social media content often lacks standardized peer review, evaluation, and verification processes.6 The absence of a peer review process increases the risk of encountering misinformation, unverified claims, and potential biases in the CPD educational content on social media platforms.4 Additionally, issues related to patient privacy, professional boundaries, and potential conflicts of interest have been raised in the context of social media use for professional purposes, including for CPD.8–11 These considerations underscore the need for a comprehensive review and evaluation of the learning outcomes and educational effectiveness of social media as a CPD intervention for surgeons in practice, which was the primary objective of our study. The secondary objective of our study was to offer recommendations regarding the future use of social media as a CPD intervention for surgeons and to identify future avenues for research on this topic.

METHODS

Our protocol was registered with PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews): registration number CRD42022359766. We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses12 reporting and publication standards.

We used Moore’s Expanded Outcomes Framework (MEOF)13 to classify the learning outcomes associated with the use of social media as a CPD intervention for surgeons. MEOF examines seven levels of learning outcomes: participation in the educational intervention (L1), satisfaction with the educational intervention (L2), changes in participants’ declarative knowledge (L3A), changes in participants’ procedural knowledge (L3B), changes in participants’ competence in an educational setting (L4), changes in participants’ performance in practice (L5), changes in patient health (L6), and changes in community health (L7) (Supplement 1 http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A386). MEOF permits the use of both objective and subjective sources of data for each learning outcome.13 Changes in patient health measured in terms of participants’ ability or via self-reports are considered L5 rather than L6.

We defined social media as any internet-based service that allows users to asynchronously broadcast information, images, and/or status updates to a wide network of connections (without necessarily requiring the user to individually select those they wish to communicate with) and, as a central feature, serves as a forum for mass collaboration and/or discussion. This definition includes, among others, platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, Snapchat, TikTok, Reddit, Tumblr, WhatsApp, Pinterest, ResearchGate, and Doximity.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched Embase and MEDLINE (all databases) for studies in English from January 1, 1946, to September 13, 2022. The search start date parameter was chosen as the earliest available search date among searched databases for inclusivity and in an effort to avoid the introduction of bias regarding the dates of first social media use. Search terms included both subject headings and keywords relating to surgeons (including specific specialties) as the population; social media or social networking (including specific platforms) as the intervention; and surgical education, continuing medical education, or CPD as the outcome. A detailed search strategy is included in Supplement 2 http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A387. Our gray literature search included conference proceedings and published dissertations. We also examined the reference lists of all included studies and all excluded review articles to identify additional studies not captured by our original search strategy. All records identified were imported into Covidence software for further review.

Study Selection

Prior to beginning title and abstract screening, all reviewers agreed on screening criteria. Five independent reviewers (A.G., F.S.-M., R.D.F., E.W., and K.C.) then screened each title and abstract. Discrepancies were resolved by a third independent reviewer during a consensus meeting with an opportunity for discussion among all reviewers. The same procedure was repeated to assess the eligibility of full-text articles with more comprehensive inclusion and exclusion criteria.

During title and abstract screening, records were screened for relevance only. Records that involved (1) a social media component and (2) the use of the social media component for educational purposes beyond just patient education progressed to full-text review.

During the full-text review, we included articles that (1) were original research studies, (2) administered or examined (e.g., via survey or questionnaire) an educational intervention involving social media, (3) included surgeons in practice as participants (whether alone or in concert with other populations; fellows were considered as surgeons in practice), and (4) reported learning outcomes and effectiveness of social media as a CPD intervention at L2 or higher on MEOF. We excluded studies reporting L1 outcomes on MEOF since the aim of CPD extends beyond simple participation in an educational activity. We excluded conference abstracts, commentaries, reviews, and articles lacking social media as an educational intervention. We also excluded studies with educational interventions involving an in-person component.

Interrater agreement was calculated at each stage of the study selection process using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (A.G. and F.S.-M.) independently extracted data from included studies using a standardized, piloted data extraction form. We extracted (1) study features including author(s), publication year, study design, participant demographics, participant specialties, and practice types; (2) social media platforms and their use as educational interventions; (3) patterns of social media use; and (4) learning outcomes and educational effectiveness, organized by MEOF level. All learning outcomes at each MEOF level addressed by each study were recorded. A qualitative analysis to identify trends in reported learning outcomes over time was carried out.

Two reviewers (A.G. and F.S.-M.) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI).14,15 The MERSQI is a 10-item instrument (Supplement 3 http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A388) that was developed specifically for the appraisal of methodological quality in studies of medical education. The MERSQI score can range between a minimum of five and a maximum of 18 points. Scoring discrepancies were resolved through a consensus meeting between reviewers with the opportunity for discussion.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Given the significant heterogeneity among included studies, we employed a narrative approach to evidence synthesis, which is in line with prior systematic reviews.16,17 We focused on participant characteristics (age, location, career stage, specialty, and practice type), social media platforms included, and outcomes reported for each study to identify emergent themes among included studies.

Ethics Approval

This systematic review did not require ethics approval.

RESULTS

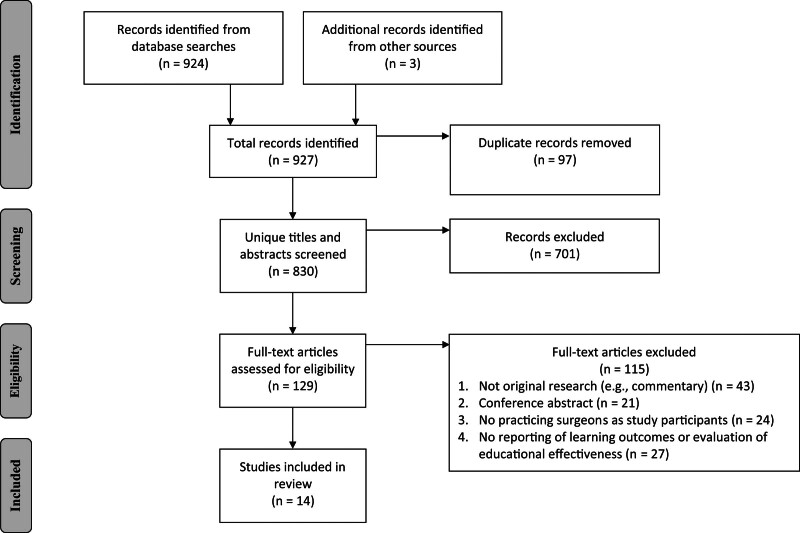

We screened 830 titles and abstracts after the removal of duplicates, including 3 studies that were identified from the reference lists of included studies and excluded review articles. We identified 129 studies for full-text review. Of these, 14 studies were included in our systematic review. Fig. 1 illustrates the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. Reported learning outcomes are summarized in Table 1 and detailed in Supplement 4 http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A389. Of the 115 studies excluded after full-text review, 43 were not original research, 21 were conference abstracts, 24 did not include surgeons as study participants, and 27 did not report learning outcomes or evaluate the educational effectiveness of social media as a CPD intervention at L2 or higher on MEOF. Interrater agreement was moderate for title and abstract screening across reviewers (82.7%–82.8%; κ = 0.49 − 0.57) and substantial for full-text review (93.8%; κ = 0.70).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Evidence

| Learning Outcomes as per Moore’s Expanded Outcomes Framework | Studies Reporting the Learning Outcome | Participant Specialty (No. Studies) | Social Media Platforms Examined (No. Studies) | Study Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2: surgeons’ satisfaction with social media educational interventions | 12 out of 14 studies (86%): Bozkurt and Chaurasia, 2021 Dong et al, 2015 Elkhayat, Amin, and Thabet, 2018 Fuoco and Leveridge, 2015 Haberle et al, 2020 Laurentino et al, 2020 Lucatto et al, 2022 Mota et al, 2018 Rapp et al, 2016 Redmann, Willging, and Roby, 2020 Wagner et al, 2018 Waqas et al, 2021 |

4 general surgeries 4 neurosurgeries 3 otolaryngologies 3 ophthalmologies 3 plastic surgeries 2 orthopedic surgeries 2 urologies 1 cardiothoracic surgery 1 oral and maxillofacial surgery 1 vascular surgery 1 obstetrics and gynecology |

10 YouTube 7 Facebook 7 LinkedIn 5 Twitter 4 Instagram 4 WhatsApp 2 ResearchGate 1 each of Doximity, Reddit, Pinterest, and Tumblr |

11 cross-sectional, descriptive survey studies (1 including interviews and 1 including profile review) 1 single-group, posttest-only study |

| Level 3: changes in surgeons’ declarative knowledge (A) and procedural knowledge (B) | 3 out of 14 studies (21%): Bozkurt and Chaurasia, 2021 Lucatto et al, 2022 Schmidt, Shi, and Sethna, 2016 |

1 neurosurgery 1 ophthalmology 1 plastic surgery |

3 YouTube 1 each of Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, LinkedIn, and ResearchGate |

2 cross-sectional, descriptive survey studies 1 single-group, posttest-only study |

| Level 4: changes in surgeons’ procedural competence in an educational setting | 1 out of 14 studies (7%): Bozkurt and Chaurasia, 2021 |

1 neurosurgery | 1 each of YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, LinkedIn, and ResearchGate | 1 cross-sectional, descriptive survey studies |

| Level 5: changes in surgeons’ performance in practice | 5 studies (36%): Bozkurt and Chaurasia, 2021 Dong et al, 2015 Nathaniel and Adio, 2016 Schmidt, Shi, and Sethna, 2016 Waqas et al, 2021 |

2 neurosurgeries 2 plastic surgeries 1 ophthalmology 1 orthopedic surgery |

4 LinkedIn 3 Facebook 3 Twitter 3 Instagram 2 WhatsApp 2 YouTube 1 each of ResearchGate, Reddit, Pinterest, and Tumblr |

4 cross-sectional, descriptive survey studies 1 cross-sectional, descriptive survey and online profile review study |

Characteristics of Included Studies

Included studies were all published between 2015 and 2022. Thirteen studies18–30 (93%) were cross-sectional survey studies, with two of these including either an additional interview22 or a social media profile review19 component. One study31 (7%) utilized a single-group, posttest-only design. There was a total of 3227 surgeon participants across all studies, and the participant-weighted mean response rate among studies that reported the number of invited individuals18–21,24,26–31 (n = 11, 79%) was 20.4% (range, 8.3%20–90.7%26). Surgeons were from 105 countries, and more than half of studies18–20,22–25,31 (n = 8, 57%) included surgeons outside North America. Among studies that reported participation figures by specialty18–21,23–28,30,31 (n = 12, 86%; 2927 total participants), neurosurgery was the most represented specialty18,24,30 (n = 1302, 44.5%), followed by plastic surgery19,24,28 (n = 442, 15.1%), general surgery23,24,26 (n = 321, 11.0%), urology21,24,32 (n = 271, 9.3%), and ophthalmology24,25,31 (n = 151, 5.2%). Other specialties included orthopedic surgery,19,24,29 otolaryngology,22,24,27,29 cardiothoracic (including cardiac and thoracic) surgery,20,29 vascular surgery,24,29 pediatric surgery,24,27,29 gynecology and obstetrics,24,29 and oral and maxillofacial surgery.22,29 Most studies19,20,22–26,29,30 (n = 9, 64%) included residents or students in addition to surgeons in practice. Among studies that reported participation figures by practice type18,21,26–30 (n = 7, 50%; 2051 total participants), the majority of surgeon respondents were in academic (n = 1344, 65.5%) as opposed to nonacademic (n = 707, 34.5%) practice settings.

YouTube was the most represented social media platform among studies18,20–24,26–28,30,31 (n = 11, 76%), followed by Facebook18,20–23,25,29,30 and LinkedIn18–21,23,25,29,30 (each n = 8, 57%), Twitter18,20,21,25,29,30 (n = 6, 43%), Instagram18,20,23,25,30 and WhatsApp18,22,23,25,29 (n = 5, 36%), ResearchGate18,20 (n = 2, 14%), and Doximity,29 Reddit,30 Tumblr,30 and Pinterest30 (n = 1, 7%).

Almost all studies18–24,26,27,29–31 (n = 12, 86%) evaluated surgeons’ satisfaction with social media as an educational intervention (MEOF L2). Three studies18,28,31 (21%) reported changes in surgeons’ knowledge (MEOF L3), 1 study18 (7%) described self-reported changes in surgeons’ competence (MEOF L4), and 5 studies18,19,25,28,30 (36%) reported changes in surgeons’ performance in practice (MEOF L5). No studies reported learning outcomes at L6 or L7 on MEOF. All assessments of learning outcomes (educational effectiveness) were conducted via participants’ self-report.

Nature and Use of Social Media as an Educational Intervention for Surgeons

Social media was used by surgeons to access academic resources18,21–24,26–31 (n = 11, 79%), exchange knowledge or ideas with colleagues18–20,22,23,25,29,30 (n = 8, 57%), learn from/discuss recent cases18–22,29 (n = 6, 43%), and network with colleagues18,19,21,25,29 (n = 5, 36%). Several studies24,26–28,31 (n = 5, 36%) focused specifically on the use of videos from YouTube and other sources, such as society websites, to prepare for surgery.

L2: Surgeons’ Satisfaction With Social Media as a CPD Intervention

Twelve studies18–24,26,27,29–31 (86%) assessed surgeons’ satisfaction with social media educational interventions and reported moderate to high satisfaction with overall contribution to the discipline or professional development18,20,24,26,27,29,31 (n = 7, 58%), facilitation of communication and discussion19–21 (n = 3, 25%), facilitation of networking18,19 (n = 2, 17%), exposure to different approaches/techniques18,19 (n = 2, 17%), utility in preparing for cases24,27 (n = 2, 17%), ease of use19 (n = 1, 8%), facilitation of consultation and professional support19 (n = 1, 8%), utility as a repository of information21 (n = 1, 8%), quality of available resources31 (n = 1, 8%), exposure to event and conference opportunities18 (n = 1, 8%), and rapid and widespread information transfer18 (n = 1, 8%).

One study23 (7%) that focused on social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic among robotic, laparoscopic, and general surgeons found that surgeons reported higher satisfaction with live webinars with chat functionality compared to streamed videos, live Instagram videos, and other formats.

Surgeons from Africa, Latin America, and Asia reported some challenges accessing social media educational resources due to connectivity and/or language limitations.22 As such, these surgeons often sought more downloadable and subtitled resources.22 Surgeons from the United States and Europe reported a reduced need for social media educational resources in light of specialized surgical consultations, case conferencing, and literature search tools available from their academic institutions.22

L3: Changes in Surgeons’ Knowledge

Three studies18,28,31 (21%) of moderate methodological quality found that the use of social media as a CPD intervention improved surgeons’ self-reported declarative and/or procedural knowledge. Knowledge of best evidence-based practices in neurosurgery18 and knowledge of a new surgical technique in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery28 are examples of reported knowledge gains. Fellows were significantly more likely than senior surgeons to report a change in knowledge following the use of social media.31

L4: Changes in Surgeons’ Self-Perceived Competence

One study18 (7%) of moderate methodological quality assessed self-reported changes in the competence of neurosurgeons; 736 neurosurgeons (n = 1104, 67%) felt that they could change their practice and 512 neurosurgeons (n = 1105, 46%) felt that they could better consider alternative management plans for patients as a result of their participation in social networking activities.

L5: Changes in Surgeons’ Performance in Practice

Five studies18,19,25,28,30 (36%) of low-to-moderate methodological qualities assessed changes in performance or practice associated with the use of social media as a CPD intervention. Academic use of social media was associated with surgeons’ self-reported improved job performance (40 out of 178 [22.5%] neurosurgeons30), care for patients (517 out of 1109 [46.6%]18 and 39 out of 178 [21.9%]30 neurosurgeons), ability to improve patient outcomes (489 out of 1102 [44.4%] neurosurgeons18 and 7 out of 19 [36.8%] hand surgeons19), and/or practice in general (9 out of 19 [47.4%] hand surgeons,19 52 out of 87 [59.8%] ophthalmologists,25 and 98 out of 184 [53.3%] facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons28). These changes were reported by surgeons to be associated with their ability to collaborate and exchange ideas using social media,25 as well as with their improved ability to consider alternative treatment options.18

Trends in Learning Outcomes Over Time

Qualitative analysis of included studies yielded no significant differences in reported learning outcomes over time. No trends over time were identified for the MEOF levels or reported educational effectiveness of using social media for CPD of surgeons.

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

MERSQI scores for each study are detailed in Table 2. The MERSQI score of the included studies was 9.0 ± 0.8 (mean ± SD) and ranged from 8.0 to 11.0. One study26 sampled fewer than the 3 institutions needed for the maximum score in this MERSQI domain. Most studies18,20,21,24–31 (n = 11, 79%) performed data analysis beyond descriptive analysis only (eg, tests of statistical inference). Twelve studies18,21–31 (86%) included appropriate data analysis; one study19 incorrectly reported the proportion of participants who found various features of the intervention under study most useful, and another study20 included figures with unclear P values. The most common reasons for low-quality MERSQI scores were study designs that were single-group cross-sectional or single-group, posttest18–31 (n = 14, 100%), subjectivity of data in the form of participant self-assessments18–31 (n = 14, 100%), little to no validity evidence for the evaluation instrument(s) employed18–30 (n = 13, 93%), and low sampling response rates18–23,25,27–30 (n = 11, 79%).

TABLE 2.

MERSQI Scores of Included Studies

| Study Number | Source | Study Design Score/3 | Sampling: Institution/1.5 | Sampling: Response Rate/1.5 | Type of Data/3 | Validity Evidence for Evaluation Instrument Scores/3 | Data Analysis: Sophistication/2 | Data Analysis: Appropriate/1 | Outcome/3 | MERSQI Score/18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bozkurt and Chaurasia, 2021 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| 2 | Dong et al, 2015 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 3 | Elkhayat, Amin, and Thabet, 2018 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 8.5 |

| 4 | Fuoco and Leveridge, 2015 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 5 | Haberle et al, 2020 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| 6 | Laurentino et al, 2020 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 7 | Lucatto et al, 2022 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 | 11 |

| 8 | Mota et al, 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 9 | Nathaniel and Adio, 2016 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| 10 | Rapp et al, 2016 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 11 | Redmann, Willging, and Roby, 2020 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 12 | Schmidt, Shi, and Sethna, 2016 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| 13 | Wagner et al, 2018 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 14 | Waqas et al, 2021 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

DISCUSSION

With the increasing use of social media as an educational and professional development medium among practicing surgeons,4–6 we summarized the evidence regarding the learning outcomes associated with this intervention, its educational effectiveness, its strengths, and its limitations. We identified 14 studies of low-to-moderate methodological qualities that reported learning outcomes and assessed the educational effectiveness of social media as a CPD intervention for practicing surgeons. Our results suggest that social media has the potential to be a useful tool for the CPD of surgeons, as its use was associated with self-reported improvements in declarative and procedural knowledge, competence, and performance in clinical practice. Surgeons were satisfied with social media as an educational medium, especially with respect to its utility in facilitating discussion and communication, networking opportunities, and exposure to new surgical techniques. There is, however, a paucity of evidence for improvements in higher level learning outcomes such as patient and community health outcomes.

Prior quasi-experimental33 and systematic review34 studies have examined the effectiveness of social media in medical education among students and trainees. Among general surgery residents specifically, Lamb et al33 found that those who participated in a 6-month, Twitter-based educational intervention between annual administrations of the American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination had significantly greater year-over-year changes in their American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination percentile rank compared to peers who did not participate. In 2013, Cheston et al34 reported that educational interventions that utilized social media tools were associated with improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and skills among medical students and, to a lesser extent, residents and practicing physicians. Our findings are in agreement with prior literature34 and extend the evidence for the educational effectiveness of social media in the population of surgeons in practice.

Despite the overall satisfaction of surgeons with social media as a CPD intervention, there are notable drawbacks and barriers to its use. The quality of content and credentials of individuals sharing content on social media typically lack a standardized review process or any review whatsoever. This means that the accuracy and quality of the content on social media are variables,4,6,35 and it is often up to the individual users to discriminate between useful and erroneous content. One strategy to address this limitation may include the implementation of standardized review processes, similar to peer review in academic research, to ensure the accuracy and reliability of shared content. Another strategy could include the development of user-friendly tools, such as rating systems, embedded citation tools, and verification badges, which could aid users in distinguishing between trustworthy and erroneous resources. Twitter’s Community Notes represents a recent example of these strategies for content moderation. Under this system, notes are posted alongside Twitter content to appraise the quality and accuracy of the content. Users may rate notes as helpful or unhelpful, and notes are classified according to consensus among ratings from users with diverse perspectives (rather than majority rule). These perspectives are defined by past note ratings, and users who consistently rate notes constructively are granted the privilege of authoring future notes.36

Patient cases shared publicly on social media pose a potential concern for patient privacy and confidentiality. To protect both patients and providers, informed consent should be obtained from patients for any postings on social media, irrespective of the degree to which attempts are made to deidentify cases.6,37 User education, guidelines, and awareness campaigns can promote responsible sharing practices among surgeons using social media to mitigate the risk of inadvertent patient identification.4 Several surgery associations, including the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons,37 the American Urological Association,38 and the European Association of Urology,39 have developed guidelines for social media use by their members. In public social media groups wherein a large number of users have access to posted cases, concerns regarding patient privacy are particularly evident given the increased likelihood that ≥1 reader may be able to identify a patient. Therefore, a distinction should be drawn between open (public) and closed (private) social media groups, where the latter can serve to decrease the likelihood of a breach of patient confidentiality. Guidelines from the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons recommend participation in closed groups,37 and the American College of Surgeons has gone so far as to create the American College of Surgeons Communities tool, a closed online platform for surgeons to share experiences and discuss cases in a secure environment.4

From an accessibility point of view, social media as a medium is dependent on the connectivity infrastructure underlying it. Regions and populations with unreliable access to technology and/or the internet are disadvantaged in their use of social media for the purposes described. To address these technology and accessibility challenges, offline or downloadable resources can help bridge the digital divide and ensure equitable access to these materials. The issue of communication and discussion via social media platforms (especially in real time) is a more challenging problem that may depend on the long-term expansion of internet access to enhance the access of underserved regions and populations. By implementing these solutions, the drawbacks associated with social media content quality, patient privacy, and accessibility can be addressed, thereby promoting a more reliable, secure, and inclusive environment for professional development.

The low-to-moderate methodological qualities of studies included in our review are in line with other studies in health professions education.15,34 In an analysis of 26 review studies that applied the MERSQI, a mean, weighted MERSQI score of 11.5 was reported across studies.15 One study34 focused specifically on the topic of social media in medical education and reported a mean MERSQI score of 8.9, which is nearly identical to the mean MERSQI score of 9.0 among studies included in our review. Future studies should aim to employ pretest and posttest, dual-group, or randomized control designs as opposed to single-group cross-sectional or posttest-only designs to improve the methodological quality of the evidence. Future studies should also aim to collect objective data using evaluation instruments with strong validity evidence rather than relying solely on subjective data from participant self-assessments.

Our study has limitations. First, the definition of social media as an internet-based service may have excluded offline or hybrid platforms that play a role in information dissemination and collaboration for surgeons. Our definition of social media emphasized asynchronous broadcasting and mass collaboration/discussion as central features, potentially neglecting platforms that prioritize synchronous communication or other unique functionalities (eg, Zoom and other teleconferencing platforms). Second, the use of descriptive study designs and lack of objectively measured learning outcomes limits our ability to draw strong conclusions regarding the educational effectiveness of social media educational interventions. Finally, the methodological heterogeneity between studies limited our ability to combine results and derive pooled effect estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of social media as a CPD intervention for surgeons in practice was associated with improved knowledge, self-reported competence, and performance in clinical practice. Surgeons were particularly satisfied with social media’s utility in facilitating discussion and communication, networking opportunities, and exposure to new surgical techniques. These findings extend the evidence for the educational effectiveness of social media to surgeons in practice. By expanding our understanding of social media as a CPD tool, we can be more confident in using it to increase the geographic accessibility of educational resources, offer cost-effective alternatives to traditionally costly CPD methods, facilitate greater peer-to-peer knowledge sharing, and potentially contribute to improved care for patients. Future studies should use experimental rather than descriptive study designs to compare the effectiveness of social media CPD intervention versus other educational interventions for surgeons. They should also focus on investigating higher level and objectively measured learning outcomes of social media CPD interventions, such as changes to patient and community health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available from the authors of this work.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: None declared.

Data Access Statement: All data analyzed in this study are included in this published article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.annalsofsurgery.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sachdeva AK. Continuing professional development in the twenty-first century. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(Suppl 1):S8–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart GD, Teoh KH, Pitts D, et al. Continuing professional development for surgeons. Surgeon. 2008;6:288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachdeva AK. Surgical education to improve the quality of patient care: the role of practice-based learning and improvement. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1379–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ovaere S, Zimmerman DDE, Brady RR. Social media in surgical training: opportunities and risks. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan TM, Dzara K, Dimeo SP, et al. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees: a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9:20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima DL, Viscarret V, Velasco J, et al. Social media as a tool for surgical education: a qualitative systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:4674–4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrucci AM, Chand M, Wexner SD. Social media: changing the paradigm for surgical education. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy DG, Loeb S, Basto MY, et al. Engaging responsibly with social media: the BJUI guidelines. BJU Int. 2014;114:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansfield SJ, Morrison SG, Stephens HO, et al. Social media and the medical profession. Med J Aust. 2011;194:642–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabbard GO, Kassaw KA, Perez-Garcia G. Professional boundaries in the era of the Internet. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guseh JS, 2nd, Brendel RW, Brendel DH. Medical professionalism in the age of online social networking. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:584–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore DE, Jr, Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, et al. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298:1002–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang B, Sandarage R, Chai J, et al. A systematic review of evidence-based practices for clinical education and health care delivery in the clinical teaching unit. CMAJ. 2022;194:E186–E194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozkurt I, Chaurasia B. Attitudes of neurosurgeons toward social media: a multi-institutional study. World Neurosurg. 2021;147:e396–e404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong C, Cheema M, Samarasekera D, et al. Using LinkedIn for continuing community of practice among hand surgeons worldwide. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elkhayat H, Amin MT, Thabet AG. Patterns of use of social media in cardiothoracic surgery; surgeons’ prospective. J Egypt Soc Cardiothoracic Surg. 2018;26:231–236. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuoco M, Leveridge MJ. Early adopters or laggards? Attitudes toward and use of social media among urologists. BJU Int. 2015;115:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haberle AD, Nath R, Facente SN, et al. What surgeons want: access to online surgical education and peer-to-peer counseling-a qualitative study. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2020;14:189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima DL, Lima RNCL, Benevenuto D, et al. Survey of social media use for surgical education during Covid-19. JSLS. 2020;24:e2020.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mota P, Carvalho N, Carvalho-Dias E, et al. Video-based surgical learning: improving trainee education and preparation for surgery. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathaniel GI, Adio O. How ophthalmologists and ophthalmologists-in-training in Nigeria use the social media. Niger J Med. 2016;25:254–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapp AK, Healy MG, Charlton ME, et al. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:1072–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redmann AJ, Willging JP, Roby BB. The use of videos in preparation for pediatric otolaryngology cases-a national survey. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt RS, Shi LL, Sethna A. Use of streaming media (YouTube) as an educational tool for surgeons-a survey of AAFPRS members. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18:230–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner JP, Cochran AL, Jones C, et al. Professional use of social media among surgeons: results of a multi-institutional study. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waqas M, Gong AD, Dossani RH, et al. Social media use among neurosurgery trainees: a survey of North American training programs. World Neurosurg. 2021;154:e605–e615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucatto LFA, Prazeres JMB, Guerra RLL, et al. Evaluation of quality and utility of YouTube vitreoretinal surgical videos. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2022;8:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azoury SC, Bliss LA, Ward WH, et al. Surgeons and social media: threat to professionalism or an essential part of contemporary surgical practice? Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015;100:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamb LC, DiFiori MM, Jayaraman V, et al. Gamified Twitter microblogging to support resident preparation for the American Board of Surgery In-Service Training Examination. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:986–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutherland S, Jalali A. Social media as an open-learning resource in medical education: current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wirtschafter V, Majumder S. Future challenges for online, crowdsourced content moderation: evidence from Twitter’s community notes. J Online Trust Saf. 2023;2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bittner JG, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook(R)) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saade K, Shelton T, Ernst M. The use of social media for medical education within urology: a journey still in progress. Curr Urol Rep. 2021;22:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roupret M, Morgan TM, Bostrom PJ, et al. European Association of Urology (@Uroweb) recommendations on the appropriate use of social media. Eur Urol. 2014;66:628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]