Abstract

Midlife, beginning at 40 years and extending to 65 years, a range that encompasses the late reproductive to late menopausal stages, is a unique time in women’s lives, when hormonal and physical changes are often accompanied by psychological and social evolution. Access to sexual health and sexual well-being (SHSW) services, which include the prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections, contraception and the support of sexual function, pleasure and safety, is important for the health of midlife women, their relationships and community cohesion. The objective was to use the socio-ecological model to synthesise the barriers and enablers to SHSW services for midlife women in high-income countries. A systematic review of the enablers and barriers to women (including trans-gender and non-binary people) aged 40–65 years accessing SHSW services in high-income countries was undertaken. Four databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Google Scholar) were searched for peer-reviewed publications. Findings were thematically extracted and reported in a narrative synthesis. Eighty-one studies were included; a minority specifically set out to study SHSW care for midlife women. The key barriers that emerged were the intersecting disadvantage of under-served groups, poor knowledge, about SHSW, and SHSW services, among women and their healthcare professionals (HCPs), and the over-arching effect of stigma, social connections and psychological factors on access to care. Enablers included intergenerational learning, interdisciplinary and one-stop women-only services, integration of SHSW into other services, peer support programmes, representation of minoritised midlife women working in SHSW, local and free facilities and financial incentives to access services for under-served groups. Efforts are needed to enhance education about SHSW and related services among midlife women and their healthcare providers. This increased education should be leveraged to improve research, public health messaging, interventions, policy development and access to comprehensive services, especially for midlife women from underserved groups.

Keywords: access, women, middle age, sexual health, sexual well-being

Plain language summary

Sexual health and sexual wellbeing services for midlife women in high income countries

Midlife, beginning at 40 years and extending to 65 years, a range that encompasses the late reproductive to late menopausal stages, is a unique time in women’s lives. Access to Sexual Health and Sexual Wellbeing (SHSW) services, which include the prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections, contraception and the support of sexual function, pleasure and safety, is important for the health of midlife women, their relationships and community cohesion. The objective of this systematic review was to use the socio-ecological model to synthesise the barriers and enablers to SHSW services for midlife women in high income countries. Eighty-one studies were included; a minority specifically set out to study SHSW care for midlife women. The key barriers that emerged were the intersecting disadvantage of under-served groups, poor knowledge, about SHSW, and SHSW services, among women and their HealthCare Professionals (HCPs), and the over-arching effect of stigma, social connections, and psychological factors on access to care. Enablers included intergenerational learning, interdisciplinary and one-stop women-only services, integration of SHSW into other services, peer support programmes, representation of minoritised midlife women working in SHSW, local and free facilities, and financial incentives for under-served groups to access services. The appetite for education about SHSW and SHSW services among midlife women and their HCPs should be capitalised upon, and utilised to improve research, public health messaging, interventions and access to holistic services, particularly for midlife women from under-served groups.

Introduction

The publication of the UK government’s first Women’s Health Strategy in 2022 1 coincided with the welcome and long overdue global recognition of the necessity for more multi-disciplinary research in both women’s2 –5 and older people’s sexual health and sexual well-being (SHSW).6 –8 Public health approaches to sexuality focus on adverse biomedical outcomes, 9 despite the growing evidence for the importance of a holistic approach when evaluating sexual health,8,9 and the inclusion of positive sexuality and sexual experiences in the World Health Organization’s definition of sexual health. 10 In this review, we have followed Mitchell’s framework, which separates SHSW into two separate, inter-linked foci of public health enquiry. 11 Sexual health is defined as encompassing the prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, sexual violence prevention, support of sexual function, desire and arousal and fertility management. Sexual well-being is a multi-dimensional concept,12,13 which comprises sexual safety and security, sexual respect, sexual self-esteem, resilience in relation to sexual experience, forgiveness of past sexual experience, comfort with sexuality and self-determination in one’s sexual life. 11 SHSW services are often combined and offered in primary care, secondary care (sexual health and gynaecology services), health services which look after physical and mental health conditions interlinked with SHSW, and community and charitable services. Midlife is defined as beginning at 40 years and extending to 65 years, 14 a time when hormonal, physical and psychological changes in the lives of women 15 are often accompanied by evolution in their relationships,16,17 and social developments. 18 This stage can be a positive transition point for women, 19 empowering them to determine how they envision spending the latter half of their years, and can result in varied sexual experiences. 20

Midlife women are a growing population, often responsible for being both primary caretakes of children and elders, and major economic contributors.21,22 Increasing societal demands impact on their sexual experiences. 23 Cultural shifts in relationship patterns, 24 and population changes due to the stretching of mid years, 25 mean that SHSW services are an increasingly important part of the lives of midlife women, integral to the physical and mental health of many.26,27 Intimate partner violence and sexual assault are major public health issues, which have long-term effects on the health and functioning of many midlife women. 28 Prompt, effective diagnosis and treatment of STIs and gynaecological diseases, and the provision to support midlife women in having enjoyable, safe sex, has wide-ranging benefits to individuals, partnerships 29 and communities. 30 Indeed, the provision of sexual and reproductive health services is related to multiple human rights and should be available in adequate numbers, physically and economically accessible without discrimination and of good quality for everybody, including all midlife women. 31 Studies are often framed in a male, hetero-normative 32 perspective and the heterogeneous needs of midlife women are sometimes stereotyped by ageist and sexist misconceptions, or forgotten, 24 squeezed between the higher prevalence of STIs in adolescents and the increasingly apparent high prevalence of sexual dysfunction in older adults. 33

General health issues, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and arthritis, begin to emerge during the latter half of midlife and operate both to impact on sexual experience, with implications for the need for help-seeking, and should also provide opportunities for issues relating to sexual matters to be raised in routine healthcare. 8 However, many healthcare professionals (HCPs) are reserved about, and ill equipped to discuss SHSW with midlife women.5,6,15,32,34 –37 Stigma and negative attitudes about women’s sexuality, and sexuality at older ages, may inhibit discussion with HCPs. 38 Embarrassment may inhibit women from accessing help when symptomatic, 15 and SHSW services are not designed in a way that encourage midlife adults to seek help.5,6,15,32,34 –37 Health policies about ageing often omit sexuality, further contributing to the lack of research and services available. 39 Technology has not been sufficiently harnessed; the only evidence available for improving access to SHSW services for midlife women lies in the menopause field, but many menopause apps lack a credible evidence base. 40

In addition to the health inequalities related to identifying as female gender, 41 including the diminishing healthy life expectancy despite a longer life expectancy of women, 42 and the historical default of medical research being carried out on men, 43 there are also significant disparities in access to, and engagement with, healthcare services among women, largely due to the social determinants of health. 44 Within globally privileged settings, there is already a high disparity in access to services. The review was therefore restricted to high-income countries to improve the specificity of findings. It has enabled us to disentangle the impact of different strands of marginalisation within the context of affluent economies, which have separate challenges from low- and middle-economic locales. The World Bank’s definition of high-income countries was employed; high-income countries had a gross national income per capita of US$13,845 or more in 2022, calculated using the Atlas method. 45

This review evaluated the research that identified the enablers and barriers to midlife women’s access to SHSW services and established whether any groups of midlife women were particularly disadvantaged. It thereby delineated the key foci for policy and strategy change to improve quality and equity of SHSW care for midlife women in high-economic countries. The socio-ecological model (SEM) recognises the multiple and dynamic factors that can affect the barriers and enablers to accessing healthcare by considering the complex interplay between individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and public policy factors. 46 These factors affect SHSW decision-making for an individual and can both enable and inhibit healthy sexual behaviours. 47 The SEM approach has been successfully employed to interrogate many aspects of SHSW services for different populations, for example SHSW services for female sex workers, 48 adolescents49,50 and migrant Asian women, 51 and has enabled a holistic consideration of the different SHSW needs of midlife women within the complex context of the societies in which they live.

Objectives

The objectives of this review were to identify the barriers and enablers to SHSW services for midlife women in high-income countries 45 using the SEM, 52 and to identify the groups of midlife women in high-income countries who found accessing these services particularly challenging.

Method

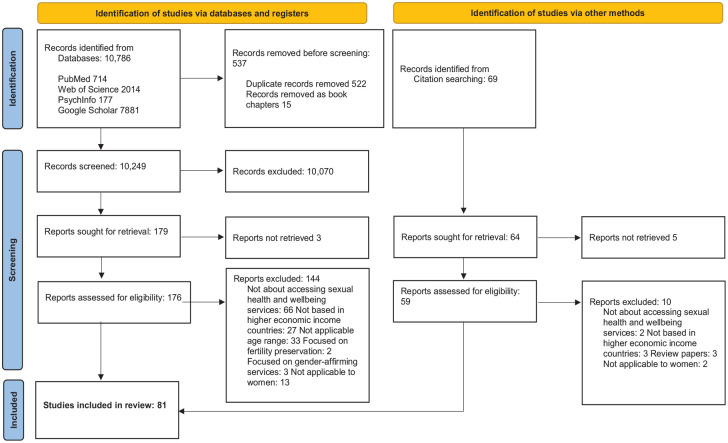

Reporting of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) recommendations (Figure 1). The protocol was Registered with the PROSPERO database on 8 June 2023, registration number: CRD42023433812.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. The barriers and enablers to accessing sexual health and well-being services for midlife women (aged 40–65 years) in high-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.

Source: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria (Table 1) were studies that had been published between November 1993 and November 2023, peer-reviewed, employed any methodology to capture primary data and investigated barriers to, or enablers of, access to SHSW care for midlife women (40–65 years old) who resided in high-income countries, 45 grouped into intrapersonal, HCP relationship, community and organisation perspectives. Studies on anyone who identified as a woman, gender diverse and non-conformist to either gender were included in this review. Transgender women and non-binary people (TGNB) experience different levels of stigma and discrimination than their cisgender counterparts, 53 but can share more in common with cisgender women than they do with men who have sex with men, 54 a group with whom they are often aggregated in SHSW research. 55 The review states when conclusions were drawn from TGNB-specific studies.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the barriers and enablers to accessing sexual health and sexual well-being services for midlife women (aged 40–65 years) in high-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Studies which were composed of self-identifying women aged 40–65 years (studies which included men and women were included if women aged 40–65 years (or whose mean age was between 40 and 65) represented 50% or more of the study population, or women aged 40–65 were analysed separately). Studies which were composed of HCPs who worked in, or sign-posted midlife women to, SHSW services. |

Studies which were composed of less than 50% self-identifying women aged 40–65 (or whose mean age was not between 40 and 65) or studies in which women aged 40–65 were not analysed separately. Studies which were composed of HCPs who did not work with or sign post-midlife women to SHSW services. |

| Design | Empirical research. | Review/Meta-analysis articles. Theoretical articles. Book chapters. Unpublished manuscripts. Conference abstracts. |

| Publication | Peer-reviewed. Published between November 1993 and October 2023. | Not peer-reviewed. Published prior to November 1993 or after October 2023. |

| Language | English. | Any other language. |

| Duration of follow-up | All. | Not applicable. |

| Focus | Studies that assessed intra-personal-based factors, for example, age, sexuality, ethnicity, knowledge, psychological factors, other priorities, that may have affected midlife women’s access to SHSW services. Studies which evaluated the impact of interactions with HCPs on access to SHSW services. Studies which investigated the impact of organisational factors (hospital policies) on access to SHSW services. Studies which investigated community factors, for example, social stigma, which impacted on access to SHSW services. Studies which investigated public policy, for example health insurance coverage, guidelines, which impacted on access to SHSW services. |

Studies which investigated interventions, for example, treatment for menopause, sexual dysfunction, HIV testing, adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, adherence to antiretrovirals, if not directly related to improving access to existing services. Studies which investigated the enablers and barriers to fertility technology techniques. Studies which investigated the enablers and barriers to accessing male-related sexual dysfunction services. Studies which assessed access to gender-affirming therapy for transpeople. Studies which investigated the impact of COVID-19 or other natural disasters on barriers/facilitators to services unless it included barriers/facilitators applicable to ongoing care. Studies with a focus on enablers and barriers to accessing SHSW care for men who have sex with men and non-binary and/ or transpeople unless there was a separate analysis for midlife non-binary and/ or transpeople, or midlife transpeople represented at least 50% of the studied population. |

HCP, healthcare professionals; SHSW, sexual health and sexual well-being.

Exclusion criteria (Table 1) comprised studies which investigated fertility technology techniques, as this was felt to widen the scope of the review too much and warrant a separate analysis. Male-related sexual dysfunction services were excluded, as although these would affect some women as partners in a relationship, women would not be the primary focus of the services. Studies addressing enablers and barriers to care for midlife TGNB people were only included in the review if they met the criteria of including at least 50% TGNB people and did not focus solely on gender-affirming therapy, a subject that warrants a separate review. COVID-19 may have had a significant impact on access to SHSW services 48 ; studies were only included if enablers and barriers that could be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet reverted back to their state prior to the pandemic.

Search strategy

The search strategy was devised by KS with the assistance of CI, CL and SB. PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were searched between 23 April 2023 and 1 August 2023. The search strategy (Figure 2) was based on the SPIDER tool. 56 Sample: Women aged 40–65 years (and their HCPs); Phenomenon of Interest: Barriers and enablers to SHSW services; Design: Peer-reviewed research (qualitative/quantitative/mixed-methods); Evaluation: Critical Appraisal Checklists (CASP) criteria 57 ; Research type: Systematic review to optimise identification of relevant articles. The detailed search strategy is documented in Figure 2. Search limits included: English language and adults and middle-aged adults. No date or country of setting limits were applied. The included articles’ reference lists were hand-searched for additional relevant articles. Articles identified in the search were exported to EndNote. After removal of duplicates, 45 the remaining articles were exported to Excel.

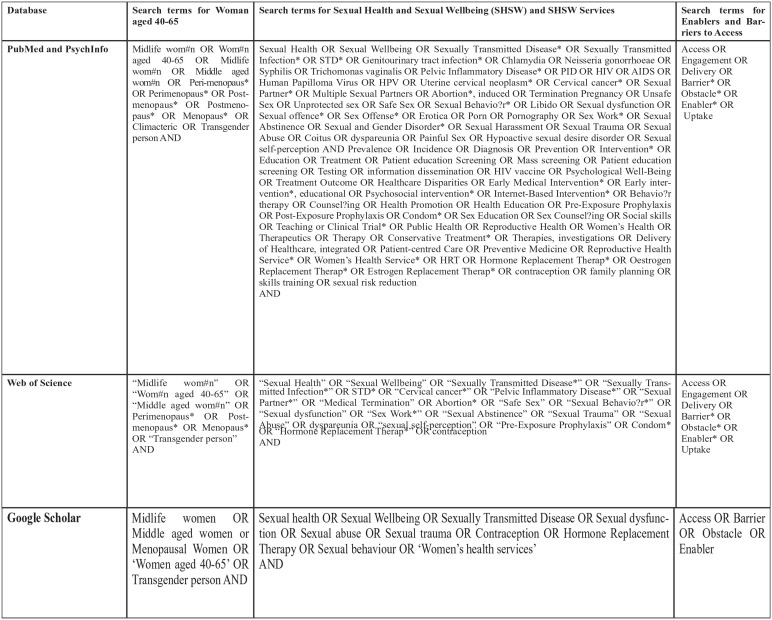

Figure 2.

Detailed search strategy criteria for the barriers and enablers to accessing sexual health and well-being services for midlife women (aged 40–65 years) in high-income countries: a mixed-methods systematic review.

Selection

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by KS and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. Full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed independently in Microsoft Excel by KS and CN. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between KS, CN and CI to reach a final decision.

Data extraction

Study characteristics were extracted by KS using a pre-set proforma on Excel (author, title, year published, participant characteristics, study aim.) Further study characteristics were then extracted by hand by KS onto a table in Microsoft Word (participant characteristics: sample, age range, gender of participants, relationship status, sexual orientation, language requirements, education level, ethnicity, study design and study findings).

Quality assessment

The CASPs 57 were used to systematically assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of the articles. The appropriate checklist was used for each study, for example the qualitative checklist was used for qualitative studies. The reporting of the results of the study were assessed for validity, what the results were, and whether the methodology was sound. KS rated the studies (high, moderate or low quality) using the checklists as guides. About 10% were randomly selected and rated by a second author (CI, SB, CL, CN) to ensure validity. Any discrepancy in the rating was discussed, and if required, a third or fourth author would have been consulted to ensure unanimity. However, there were no discrepancies, resulting in a Cohen’s Kappa rating 51 of 1. Eligibility of articles was not determined by quality rating.

Data synthesis

The socio-ecological model (SEM) 52 was used to conceptualise and organise the findings into the enablers and barriers to accessing SHSW care, in terms of intra-personal factors, interactions with providers, organisational factors, community factors and public policy. The use of the SEM model has precedence in contextualising the complex levels of socioecology in which individuals are embedded, and the social, structural and cultural influences on behaviours affecting access to SHSW care. In the past, it has proved valuable in the analysis of the barriers and enablers to SHSW care for female sex workers, 58 adolescents, 59 urban men 49 and migrant Asian women. 50 Narrative synthesis was used to explore relationships within and between study findings. This method was employed because characteristics of the study designs and outcomes were too heterogenous to yield a meaningful summary of findings using a meta-analysis. The main findings and conclusions were grouped and coded inductively into descriptive themes that emerged from the data within the categories of ‘barriers to’ and ‘enablers of’ access to SHSW care, as defined by the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Data were further grouped and coded to iteratively develop and refine descriptive themes, with each study contributing new themes, using the SEM. Generation of higher-level analytical themes was undertaken.

Results

Study characteristics and main findings

Eighty-one studies were included in the final selection (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of studies for the barriers and enablers to accessing sexual health and sexual well-being services for midlife women (aged 40–65 years) in high-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review.

| Author (year of publication), study location | Study population characteristics (sample, age range, gender of participants, relationship status, sexual orientation, education level, ethnicity) | Study design and methodology | Aim of study | CASP quality | What are the results? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auerbach et al. (2020), USA 54 | 43, 55.6% were aged 41–55 years, 25 women who identified as cisgender, 10 women who identified as transgender, 3 women who identified as ‘other’, 55.5% more than high-school education, 71% Black/African/Afro-Caribbean, 5 HCPs (one identified as a transwoman, two as cisgender women, two as cisgender men) | Qualitative. Focus groups. Convenience sampling. | Barriers and facilitators to including transwomen in HIV treatment and support services traditionally focused on cisgender women. | High, good mix of participants. | Histories of trauma, need for space safe away from men, unique challenge of being a woman in the world. Lack of understanding that many cisgender women are receptive to education, with a low barrier to improving their knowledge. Drawn to women’s care spaces out of desire for community, care tailored to specifically meet women’s needs, and a space that feels free of stigma and harm. Inclusive all-women care environment would disentangle transwomen demographically from men who have sex with men, foster community and understanding, affirm gender. |

| Bass et al. (2022), USA 60 | 34, age 18–52, mean age 34–46, 21% identified as female, 82% identified as transwoman, 6% identified as queer, 2.9% identified as ‘additional’, 56% some college education and above, 44% African American, 41% White, 21% Latinx, 12% other races | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sampling. | Barriers and facilitators to HIV PrEP use in transgender women. | High. | Knowledge of HIV PrEP is low. Persistent beliefs about effect of PrEP on hormone use. Need for culturally appropriate trans-specific messages in HIV prevention interventions and communications. |

| Benyamini et al. (2008), Israel 61 | 814, Aged 45–64, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 540 long-term Jewish resident women, 151 Russian immigrants, 123 Arab women | Quantitative. Cohort. Questionnaire. Stratified random sampling. | Assess rates of primary and preventive healthcare use among midlife women from different cultural origins to identify socio-demographic and health characteristics that could explain differences in healthcare use. | High. | Long-term residents reported more preventive visits and screening tests compared with immigrants and Arab women. Cultural group, education, self-rated health and health motivation were significantly associated with use of primary and preventive care. Ethnic/origin group differences were mostly related to cultural rather than financial barriers. Arab women’s low use of preventive gynaecologic care related to lack of physicians of same culture and gender. |

| Blackstock et al. (2021), USA 62 | 52, Mean age 44.7 years, 11.5% transgender women, 88.5% gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 34.6% less than a high school education, 86.5% Latina or non-Latina Black | Quantitative. Cohort study. Pilot intervention. Convenience sampling. | Evaluate HIV PrEP outreach and navigation intervention. | Moderate (Study aim not completely clear). | 50% Aware of HIV PrEP. Gap between PrEP interest and connecting to PrEP care. Importance of peer-outreach. |

| Bullington et al. (2022), USA 63 | 578, Aged 25–60 (35 experienced menopause aged under 41, 101 experienced menopauses aged 41–45, 442 experienced menopause aged 46–50), women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, majority Black ethnicity but mixed ethnicity study (e.g. 9% White) | Quantitative. Cohort. Convenience sample. | Description of premature and early menopause and subsequent hormonal treatment in women living with or at risk of HIV. | Moderate (significant confounding factors as to why older women received less hormonal therapy). | 51% of women who experienced menopause before 41, 24% of women 41–45, 7% of women between 46 and 50 received menopausal hormonal therapy or hormonal contraception. Women Living with HIV are less likely to access hormone therapy for menopause than other women. |

| Bush et al. (2007), USA 64 | 22, Physicians | Qualitative. In-depth interviews. Convenience sampling. | Physician’s perceptions on HRT and counselling strategies. | High. | Many felt that women should oversee HRT decision. Decision aids are needed to guide discussions with women. |

| Cahill et al. (2020), USA 65 | 19, Mean age 42, 72% had high-school or less education, identify as transgender women, mixed ethnicity study | Qualitative. Focus groups. Convenience sampling. | Explore barriers to HIV PrEP uptake. | High. | Some had not heard of HIV PrEP, some reported their HCPs had not told them about PrEP, some had questions about side-effects, some expressed medical distrust. Expressed need for gender-affirming healthcare services, concerns about interactions between feminising hormones and PrEP, these interactions need to be made clear in health education campaigns. Clinicians should be trained in providing gender-affirming care. |

| Cannon et al. (2018), USA 66 | 68, Ages 18–50 but ages 35–50 analysed separately, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 59% African-American, 25% White, 14.9% other | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study: survey with multiple-choice close-ended questions administered via interview. Convenience sampling. | Risk of unintended pregnancy among newly incarcerated women. | Moderate (small study). | Poor knowledge about emergency contraception safety, when and how to take. About 58.8% aged 35–50 used no contraception at intake, but 63.2% would accept free contraception at release. |

| Cappiello and Boardman (2021), USA 67 | 35, Nurse practitioners in their first 2 years of community-based practice | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Exploration of perceived competency in providing sexual and reproductive healthcare. | High but small study. | More preparation needed to discuss STIs, dyspareunia and pelvic pain. Interest in discussion of sexuality across the lifespan and postmenopausal sexual concerns. |

| Clarke (2009), USA 68 | 6 Magazines, 3 for middle-aged women, all 3 have circulation of >2,000,000 | Qualitative. Exploratory content analysis. | Portrayal of sexuality, sexual health and sexual disease. | High. | Major themes: sex depicted as a woman’s work and responsibility in a marriage; accountable for husband’s sexual fulfilment, and happiness. Fear-mongering in refusing husband’s request for sex. Idea that sex can be viewed as a workout and beneficial for women’s health. |

| Cronin et al. (2023), England, Finland, Denmark, New Zealand, Australia and USA 22 | 48 Nurses, ages 37–65 (majority over 40 years) | Qualitative. Focus groups and interviews. | Perspectives of nurses (wide range of clinical settings) on digital interventions as strategies to support menopausal women. To understand the requirements for designing health interventions for support in the workplace. | High. | Women were frustrated by the stigma and lack of recognition and awareness at work about menopause. Without awareness, women felt uncertain of the validity of their own experiences, often questioning themselves and their concerns. Colleagues were judgemental, lacked insight, tiredness related to menopause symptoms was not socially acceptable. Participants from many countries felt that many women were unprepared and there was a lack of knowledge about the menopause. Mothers had not prepared them – no detail/depth in explanations. ‘You just get on with it, that sort of thing’. ‘I talk to mums everyday about everything to do with their bodies and their bleeding, babies and everything . . . there are so many variations on how it is for premenopausal women, like maybe we don’t really understand enough’. Participants preferred to select from a range of interventions available across different formats (to meet individual needs). Participants had spent a long time looking for information, with poor results. They felt that due to the widespread use of smart phones, it should be possible to have quick, easy access at any time and anonymously, to a private, secure platform with evidence-based information. They felt that digital resources should be culturally sensitive, with podcasts, videos, virtual reality, mindfulness, expert blogs. |

| Dakshina et al. (2014), UK 69 | 202, Ages 16–60, Median age 41, IQR 35–49 years, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | Ascertain proportion of women with a documented discussion about their family planning needs within a 12-month period. | High. | Contraception only documented to have been offered to 15% of women who required it. |

| Dalrymple et al. (2017), Scotland 70 | 31 (18 Women, 13 men), ages 45–65, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, most had been divorced, most from deprived areas as per Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation areas | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sample. | Psychosocial factors that influence risk-taking. | High (but small study and may not have been representative due to recruitment from clinics and sporting centres and limited ethnic diversity). | Reassured if new partner had few previous partners, long previous relationships, or had recently spent time alone. Very few used condoms or tested for STIs. Unwanted pregnancy shaped risk perceptions through life-course. Prioritisation of intimacy above risk of STIs. Feelings of reassurance and safety from STIs were associated with intimacy. Motivation to seek intimate and monogamous relationships, and a sense of emotional connection with new partner, lent safety to actual exposure to STIs. Vulnerability associated with relationship transitions – guilt and loss of self-esteem leading to prioritisation of emotional rather than health needs (safe sex). Social norms relating to age-appropriate sexual and health seeking behaviours – older people ‘should know better’, ashamed to seek help. Distancing from young people’s risky behaviour. Felt had to adjust to new sexual culture – fast progression to sex in new relationships. Sense of freedom linked with feeling young, encouraging more risk taking. |

| Dietz et al. (2018), USA 71 | 30, Aged 45–60, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative study. Focus groups. Convenience sample. | Women’s knowledge of menopause, preferred sources of information, barriers to treatment. | High (but not generalisable). | Feel insufficiently informed about hormone therapy. Prefer older female providers. |

| Doblecki-Lewis et al. (2015), USA 72 | 8, Aged 40–59 (analysed separately from other women in study aged 18 to >60), women, gender identity/education/ethnicity not separated out for this age group, but study included predominantly Black and Hispanic participants and 77% of total participants were heterosexual) | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | Self-reported sexual risk behaviour, awareness and perception of HIV Pre exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and HIV Post exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) in a sheltered population (women experiencing homelessness). | High (but although analysed separately, small sample of midlife women). | Women who reported that they would ‘definitely consider’ or ‘might consider’ PrEP or PEP were significantly younger (mean age = 29.3 years) compared with those who reported they would ‘definitely not consider’ these strategies (mean age = 41.5 years; p = 0.004 for difference). |

| Donati et al. (2009), Italy 73 | 720, Aged 45–60 years, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | Women’s attitude, knowledge and practice regarding menopause and HRT. | High. | Minority received information about menopause, those who did found it poor and contrasting. |

| Duff et al. (2018), Canada 74 | 109, Aged 44–53, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 33% Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, two-spirit, 90% high school graduate, 56% Indigenous, 7% African/Black/Caribbean, 36% White | Quantitative. Cohort study. Convenience sampling. | Correlates of antiretroviral adherence among perimenopausal and menopausal women living with HIV. | High. | Severe menopausal symptoms, injecting drug use and physical/sexual gender-based violence associated with <95% antiretroviral adherence. |

| Du Mont et al. (2021), Canada 75 | 27, HCPs who look after people who have been sexually assaulted | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Convenience recruitment. | Evaluation of networks’ capacity to address needs of trans-sexual assault survivors. | High. | Barriers to providing care: lack of knowledge, discriminatory attitudes, limited training opportunities. About 100% felt would benefit from further training to help trans-people. Hospital policies not trans-sensitive. Paucity of trans-positive services for referral/collaboration. Facilitators: efforts to promote trans-positive environments, trans-positive hospital policies, partnership building with other services. |

| Ejegi-Memeh et al. (2021), UK 76 | 10 (4 Aged 40–65, results separated out), aged 50–83, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Barriers and facilitators to sexual discussions in primary care in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. | High quality but small number. | Problematic changes to sexual health and well-being, attributed to diabetes, menopause, ageing and changes in intimate relationship, tended not to be discussed with HCPs. Women assumed HCPs did not broach topic of sex due to embarrassment, ageism, social taboos around older women and sex. Facilitators: professional-patient rapport, female HCPs, instigation of conversation by HCP. |

| Erens et al. (2019), UK 8 | 23 (5 Women aged 40–65 years, results separated out), aged 55–74, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 3 married, 1 widowed, 1 co-habiting, 30,503,880 (9,751,175 women aged 40–65 years, results separated out) | Mixed methods. Qualitative. Interviews. Purposive sampling from nationally representative sample (Natsal-3). Quantitative. Cross-sectional (nationally representative sample from private residential addresses, Natsal-3). | To explore how older people see their health status as having influenced their sexual activity and satisfaction; and to further understanding of how they respond and deal with the consequences. | High. | Where help had been received, it was in the form of sildenafil for men. No participants in the qualitative component mentioned any other form of help. Women described continuing to have sex despite a health-related reduction in their own sexual desire to ensure the continued stability of the relationship. ‘You get used to what you like and because I can’t have what I like I’m not really bothered’. After adjusting for age and relationship status, the odds for being sexually active were much lower for those who saw themselves as being in bad/very bad health compared with those in very good health. For women in a steady or cohabiting relationship, after adjusting for age, satisfaction with their sex life was associated with feeling happy in the relationship. |

| Erickson et al. (2019), Canada 77 | 292, mean age 43, 10% transgender women, 90% cisgender women, 48% had completed high-school, 58% indigenous, 34% White, 4% Afro-Caribbean, 5% other | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Convenience sample. | How incarceration affects HIV treatment outcomes. | High. | Exposure to recent incarceration independently associated with reduced odds of HIV virological suppression. |

| Esposito (2005), USA 78 | 56 (40 Women, 6 HCPs), ages 39–62, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 38% married or cohabiting, 6, HCPs, ages 34–56, all White and European American | Qualitative. Focus groups. Convenience and snowball sampling. | Immigrant Hispanic and Healthcare Providers expectations of healthcare encounters in the Menopause. | High. | Linguistic ability. Cultural inhibitions to not bringing up topic. Dealing with American providers required higher level of assertiveness than previously needed. Lack of access to advice – some knowledgeable relatives were now dead, others never talked about menopause/could not remember it/denied symptoms. Brochures and videos nonspecific – unsure if applied to them, failed to address intensity of symptoms. Women wanted provider-initiated, individualised, anticipatory guidance for menopause. Providers felt other challenges (diabetes, heart disease, HIV prevention) were more important. Providers did not have time to assess their needs. Need for better mainstream medical relief from menopause symptoms. HCPs questioned whether menopause an issue for immigrant Hispanic women. Symptoms were not important because women were socialised to minimise their gynaecological discomforts in context of competing family needs. May manage symptoms effectively through alternative health resources such as local medicine woman. HCPs wanted patients to be informed and clear about what they wanted. Frustrated with lack of continuity in care, for example, when international mobility complicated care. Cultural expectations of stoicism around gendered issues such as menopause. |

| Ettinger et al. (2000) and Ettinger and Pressman (1999), USA79,80 | 749, Aged 50–65, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Convenience sampling. | Predictors of women receiving HRT counselling. | High. | Higher level of education and higher level of income associated with increased likelihood of HRT counselling being obtained. |

| Fox-Young et al. (1995), Australia 81 | 40, Aged 45–55, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Focus groups. Convenience sampling. | Women’s perceptions and experiences of menopause, HRT, doctor–patient relationships. | High (but not generalisable). | Lack of reliable and accurate information about menopause. Need to foster open discussion between women and HCPs, need for equal partnership. |

| Gazibara et al. (2022), Spain and Serbia 82 | 461 from Madrid, 513 from Belgrade, 40–65, Women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sampling. | Compare climacteric symptoms associated with health-related quality of life. | High (unclear whether similar level of contra-indications in two different populations). | Similar ratings of somatic and urogenital complaints. Serbian women of higher education were more likely to use HRT. |

| Gkrozou et al. (2019), UK 40 | 22 Apps | Review analysis of menopause apps. | Identify mHealth apps that address the menopause with a focused view on the degree of medical professional involvement and evidence base practice in their design. | High (but limited due to small number). | Only 22.7% of the apps analysed had documented evidence-based practice in the form of guidelines or treatment protocols. |

| Gleser (2015), UK 83 | 62, Specialist trainee doctors | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Questionnaire. Convenience sampling. | Determine views and attitudes of specialist trainee doctors towards sexual health in the (peri)menopause. | Moderate. (Did not look at confounders such as ethnicity, sexuality). | Do not believe that women proactively raise their concerns regarding menopausal symptoms affecting sexual health without being asked. Reported lack of consultation time as main barrier to address sexual health and sexual problems in menopausal women. Some reported perceived unease from patient’s side, poor coverage of topic in curriculum, lack of training. |

| Gomez-Acebo et al. (2020), Spain 84 | 2038, Ages 20–85 (1031 women born before 1950 had average age of 70, 1007 women born after 1950 had average age of 48), women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, majority with low level of education, 12 Spanish provinces | Quantitative. Cross-sectional design. Purposive sampling. | Influence of individual and contextual socio-economic levels on reproductive factors. | Moderate (did not stratify by ethnicity). | For women born before 1950: more educated women double use of HRT, women living in less vulnerable areas double use of HRT. But socio-economic inequalities in HRT not true for women born after 1950. |

| Goparaju et al. (2015), USA 85 | 39, Median age 49, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, Majority Black/African American or Latina/Hispanic, mixed level of education, 50% married | Qualitative. Focus groups. Purposive sampling. | Women’s knowledge, attitudes and potential behaviours regarding HIV PrEP. | High. | PrEP awareness was extremely low and the HIV-negative women urged publicity: they wanted to use and recommend it to others despite potential side effects, and difficulties with access, duration and frequency of use. Women’s reactions to PrEP differed based on their sero-status: HIV-negative women expressed much enthusiasm while the HIV-positive women voiced caution and concerns based on their experience with ARVs. |

| Guo and Sims (2021), USA 86 | 498, Aged 42–65, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, Chinese American women | Quantitative. Cohort study. Purposive recruitment. | Patient-level factors associated with Pap uptake. | High. | Having a female healthcare provider positively associated with Pap test uptake. Not having a primary healthcare provider and not having time to go to the doctor negatively associated with Pap test uptake. |

| Heinemann et al. (2008), USA 87 | 10,297, Age: 40–70, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, education level: over 60% were low/medium, majority married/stable relationships, 9 countries on 4 continents | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Validated survey. National representative population panes and quota sampling. | Prevalence of menopausal women’s symptoms, motivations for hormone therapy. | Moderate (ethnicity not described). | Self-reported symptoms did not differ significantly among women in Europe, North America, Latin America and Indonesia. Prevalence range of hormone therapy from 50% to 1.8%. Acceptance of HRT affected by: worry about side effects. |

| Hendren et al. (2019), Canada 88 | 154, Median age 41–45, 53% women (Adult nephrologists) | Quantitative. Cohort. Convenience sampling. | Adult nephrologists training in, exposure to and confidence in managing women’s health. | High. | 65% lacked confidence in women’s health issues, 89% felt that interdisciplinary clinics and continuing education seminars would improve their knowledge. |

| Hillman et al. (2020), UK 89 | 142,919,989, Aged over 40 (2,677,613 HRT prescriptions), women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, from 6478 practices | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | General practice HRT prescription trends and their association with markers of socio-economic deprivation. | High. | HRT prescribing rate 39% lower in practices from most deprived quintile compared to most affluent. After adjusting for cardiovascular risks/outcomes, 18% lower. More deprived practices have significantly higher tendency to prescribe oral HRT (should be avoided if high cardiovascular risk). |

| Hinchliff et al. (2021), UK 90 | 23 (12 Women, 11 men), ages 58–75, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, majority married | Qualitative. Interviews. Purposive sampling. | Explore why older adults do, or do not, seek help for sexual difficulties. | High. | Both women and men framed help-seeking in relation to erectile dysfunction. Reluctance/inability to talk about sex with partner stopped them getting help. Feeling embarrassed to talk about sexual difficulties – considered taboo. Dealing with other health conditions more important. Significant barrier was concern about interaction of medicines prescribed for the sexual difficulty with those already taken for health conditions. Spent a long time, sometimes years, thinking about whether to get help. Patient fear of not being taken seriously and doctor reticence to ask. Help-seeking journeys often ended without resolution. Most were not asked about sexual well-being even though had conditions known to affect sex life. Doctors prioritised general health over sexual health. Having access to approachable doctor facilitated help-seeking. Patients saw help-seeking only appropriate up to a certain age. |

| Howells et al. (2019), UK 91 | 73, Women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 56% Black African, 5% Black Caribbean, 5% Black British, 3% White British, 10% White other | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Retrospective case note review. Purposive sampling. | Assess uptake and effectiveness of HRT in postmenopausal women living with HIV. | High. | Good symptom control (91%) in those of Black ethnicity who started HRT but low uptake (52%). |

| Huang et al. (2009), USA 92 | 1977, Aged 45–80 (77% between 45 and 64), women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 67% currently married/living as married, 44% White, 29% African American, 18% Latina, 19% Asian | Quantitative. Cohort study. Purposive sampling. | Factors influencing sexual activity and functioning. | High. | 43% Reported moderate to very high sexual desire or interest, decreased with increasing age varied according to race/ethnicity/co-habitation. Sexual desire and interest strongly associated with sexual satisfaction. About 40% reported problems with sexual activity. Physical and mental health strongly associated with sexual desire and interest. Lack of partner capable of or interested in sex important. |

| Huynh et al. (2022), USA 93 | 87, Ages <45 (40%), 45–65 (44.8%), >65 (12.6%), women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 85% Heterosexual, 72% married or partnered, 82% Caucasian, 5.7% Asian, 4.6% Black or African American, 1% Latina, 1% American Indian or Alaskan, 4.6%, Other/prefer not to say, Focus groups: 13, Individual interviews: 3 | Mixed methods. Cross-sectional study and Qualitative (interviews and focus groups). Convenience sampling. | Characterise education that patients with breast cancer receive about potential sexual health effects of treatment, and preferences in format, content, timing. | Moderate quality (? Selection bias and homogenous population, and qualitative element very small). | Few women received information about sexual health effects of treatment. Patients in favour of multiple options of education being offered, with emphasis on in-person options and support groups. |

| Jacobs et al. (2014), USA 94 | 3258, aged 42–52, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 7 US sites, 68% married, 76% had some form of college education, 28% African American, 7% Chinese, 8% Japanese, 7% Hispanic, 50% Caucasian | Quantitative. Cohort. Mixed recruitment methods. | Relationship between perceived everyday multi-ethnic/multiracial and other discrimination and receipt of cervical (and breast) screening. | High (but difficulty with concept of ‘reported discrimination’). | Reported discrimination owing to physical appearance and gender associated with reduced receipt of Pap smear regardless of race. Perceived discrimination much higher in African American women. |

| Kerkhoff et al. (2006), Ireland 95 | 58, Age 22–81, median age 46, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sample. | Assess female renal transplant recipient’s awareness of gynaecological issues, and to assess uptake of screening services. | High (but not generalisable). | 84% Aware as to why they should have regular cervical smears. |

| Kingsberg et al. (2013), USA 34 | 3046, Age: postmenopausal, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Questionnaire. Purposive sampling. | Characterise postmenopausal women’s experiences with vulvar-vaginal atrophy and interactions with HCPs about it. | High. | 24% Attributed symptoms to menopause, 65% had discussed symptoms with HCP, 40% using treatment (62% who had consulted HCP were using treatment). Concerns about side effects and cancer risks limited access to treatment. |

| Levin et al. (2023), Israel 96 | 252, Mean age 54, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sample. | Compare stage and survival of cervical cancer of Jewish and Arab women. | Moderate- (many more Jewish women in study, unsure re. power, and many confounders). | Arab women at higher risk to be diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer than Jewish women. |

| Lewis et al. (2020), UK 24 | 19 (10 Women, 9 men), ages 40–59, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Face-to-face interviews. Purposive selection from NATSAL-3. | Identify factors shaping STI risk perceptions and practices among individuals contemplating or having sex with new partners following end of long-term relationship. | High (but small number). | Loss of fertility reduces motivation to prioritise safe sex. Inadequate indicators to assess STI status of partners, for example, demeanour, appearance. Self-perception as low risk even if have come out of long-term relationship. Constraints on the navigation of sexual safety include self-perceived STI risk rooted in past. Perceived dominance of ‘couple culture’ pressure to re-partner. Perceived norms vary between social networks – normalisation of condomless sex with new partners, paying for sex, ‘othering’ of those at risk of STIs/HIV. Intersecting gender-age dynamics in negotiation of risk prevention strategies – association with youth, lack of familiarity, concerns about erectile dysfunction. Enablers: peers and younger relatives’ influences. Age-related barriers to accessing condoms; disconnection from safe sex messaging and services (men who have sex with men and youth focused). Greater public discussion about sexuality and more positive representation of sexuality in mid-life in tension with sensationalised media coverage. Age-gender barriers to accessing condoms in shops/pharmacies. |

| Lippman et al. (2016), USA 97 | 50 (11 Gave in-depth interviews), median age 42, transgender women 56% post high-school education, 30% Black African-American, 22% White/Caucasian, 20% Hispanic/Latino, 8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 8% Native American, 12% multi-racial |

Mixed. Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Qualitative interviews. Convenience sampling. | Feasibility and acceptability of HIV self-testing. | High. | 68% Prefer HIV self-testing to attendance at clinic. Emotional support embedded into service very important. |

| Maar et al. (2013), Canada 98 | 18, HCPs | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Structural barriers to cervical screening. | High. | Shortage of HCPs, lack of recall system, geographic/transportation barriers, health literacy, socio-economic inequalities, generational effects, colonial legacy. |

| Maiorana et al. (2021), USA 99 | 67, 36 Staff, 31 participants in interventions, average age 44 (range 21–63), all participants identified as transgender women of colour, 77% of staff identified as transgender women of colour | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Identify commonalities amongst intervention services for Transgender Women of Colour (addressing unmet basic needs, facilitating engagement in HIV care, health system navigation, improving health literacy and support) and relationships formed during implementation. | High. | Interplay of transphobia, sexism and racism. Transgender women have low self-esteem, feel defensive and socially excluded due to stigma, and previous experiences of marginalisation in community and healthcare system. Gender-affirming services and caring relationships help to engage transwomen of colour in care. Intervention services need to be complex, and HCPs need to be able to perform many roles. Services that address basic unmet needs such as food, housing before addressing other barriers to engaging in HIV care. |

| Moro et al. (2010), Canada 100 | 4, Age 46–72, women, gender-identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Focus group. Convenience sampling. | Enablers and barriers to obtaining bioidentical hormones and how to improve the access path. | Poor (small number). | Seek information from friends/books/websites/HCPs. Quality of available information a barrier to making informed decision. Internet a confusing medium-wide range of quality. HCP with supportive/trustworthy/ample information seen as key enabler to care. Some physicians did not listen to their needs. Some made unilateral decisions favouring HRT without consulting patient. Struggle to access physicians who would prescribe HRT. Cost of bioidentical HRT big barrier. Suggestions: continuing education for physicians, comprehensive website with risks and benefits of HRT, regular seminars for menopausal women, policy change to allow other health professionals to prescribe HRT, women-only clinics. |

| Munro et al. (2017), Canada 101 | 14 Women (8 aged over 40) and 10 HCPs, women who identify as transgender women | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Dynamics of healthcare utilisation by transwomen living with HIV. | High, but small study. | Importance of coordinating HIV services and transition-related care. Importance of training service providers. |

| Nappi and Kokot-Kierepa (2010), USA 102 | 4246, Aged 55–65, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, Sweden, Finland, UK, USA, Canada | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Interviews using structured questionnaire. Purposive sampling. | Issues related to vaginal atrophy via an international survey. | Moderate (purposive sampling but not sampled to be representative). | Different needs in different countries (51% in US versus 10% in Finland aware of local treatment); country-specific approaches to improve uptake of treatment for vaginal atrophy. About 77% believe women uncomfortable discussing vaginal atrophy, 42% not aware that local treatment is available. |

| Nemoto et al. (2021), USA 103 | 60 in Cohort study (34 enrolled in HIV care and 26 who had never enrolled), 12 interviews, age range 19–60, average age 41, transgender women (78% gender identity transgender woman, 21% female), 32% college or above level education, 80% African American, 13% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 5% Multiracial | Mixed study: Cohort and qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sample. | Describe access to HIV primary care for African American transwomen living with HIV. | High. | Transphobia and community stigma are strong barriers to enrolling in HIV care; 44% who had enrolled in HIV care had not received anti-retroviral treatment (ART); 50% of those on ART had poor adherence. If engaged in sex work, sold drugs, or experienced higher levels of transphobia less likely to have enrolled in HIV care. |

| Nusbaum et al. (2004), USA 104 | 1196, 54% aged <45, 15% 45–54 years, 32% aged over 54, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Survey. Convenience sampling. | Self-reported sexual concerns and interest and experience in discussing these concerns with physicians. | High. | 96% of ‘middle aged’ women showed interest in discussing with HCP. Women who discussed concerns found it helpful. Felt that discussing would be easier if physician broached topic. Having female physician would facilitate discussion. Most women had never had topic raised by physicians. |

| Okhai et al. (2020), UK 105 | 6455 Women (1595 aged 40–50, analysed separately, 607 aged >50, analysed separately), women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, all acquired HIV via sex with men, 14% White, 5.7% Black Caribbean, 70.6% Black African, 3.6% Black other, 2.7% South Asian, 3.4% Mixed | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | Investigate whether association between menopausal age and engagement in HIV care. | High, large study. | Postmenopausal aged women less likely to be engaged in HIV care than younger ages differs from previous studies? Due to different definitions of engagement in care. However, suggestion that better adherence to antiretrovirals among 40–50 years than younger women. |

| Ong et al. (2022), Australia 106 | 3 Suburban GP practices, qualitative: 33, 17 doctors, 7 nurses, 9 administrative staff | Mixed methods. Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sample. | Hub and spoke model: primary care HIV/STI testing and treatment with support of specialist SH centre hub. | High. | Early and sustained increase in chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, HIV testing. Many training needs identified by GPs, nurses and admin staff, for example, taking a non-judgemental sexual history, using culturally appropriate terms, approaching partner notification, legal requirements, how to invite patients to talk, work flow in the clinic, to provide flexible time for lectures, routine refresher training-enthusiasm to upskill, rarely provided consultations with ‘priority’ populations (LGBTQ, sex workers, people who inject drugs, certain ethnicities, incarcerated, refugees). |

| Parkes et al. (2020), UK 107 | 7019, Ages 16–74 but approximately 50% over 40, and ages analysed in groups, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 88% White | Quantitative. Latent class analysis from NATSAL-3. Purposive sampling. | Identify clusters of sexual health markers with their socio-demographic, health and lifestyle correlates. | High. | 6 Classes found for women, for example, 7% ‘unwary STI risk takers’. |

| Politi et al. (2009), USA 108 | 40, Mean age 55, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, unmarried women, 73% college degree, 98% White | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Describe the experience of middle aged and older aged unmarried women’s communication with HCPs about Sexual Health. | Moderate (not generalisable). | Sexual minority women hesitant to share information due to previous negative experiences when disclosing sexuality. Unmarried women more likely to disclose information about sexual health if perceive HCP does not make assumptions and appears non-judgemental. Unmarried women more comfortable talking to female providers about sexual health. |

| Reese et al. (2020), USA 109 | 144, Mean age 56, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 62% partnered, 67% White, 27% Black/African American, 4% Hispanic/Latina | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Web-based baseline self-report surveys. Convenience sample. | How commonly women sought help for sexual health concerns after breast cancer treatment and from whom, and whether help-seeking was associated with sexual function/activity/self-efficacy. | High. | Women seeking help were younger and more likely to be partnered; 42% sought help from intimate partners, family/friends; 24% from HCPs, 19% from online/print materials. Women seeking help from outlets other than HCPs had significantly lower self-efficacy than those who did not. |

| Roberts and Sibbald (2000), UK 110 | 181 General practitioners, 147 Practice nurses | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Purposive sampling. | Knowledge and views about HRT. | Moderate | 57% of GPs and 85% of practice nurses wanted more knowledge about HRT. |

| Rostom et al. (2002), Canada 111 | 51, Ages 40–70, women, gender-identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 75% had college or University degree | Quantitative. Randomised trial. | Perceptions of HRT associated risks, barriers to HRT, knowledge of menopause symptoms, decision aids for HRT/menopause. | High. | Realistic expectations score of risk perceptions (heart disease, hip fractures, breast cancer): 35%. Baseline knowledge score: 77%. |

| Samuel et al. (2014), UK 112 | 124, Age range 50–75 years, mean age 52, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 83% Black ethnicity | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Notes review. Purposive sampling. | Review of care provided to HIV-positive women aged over 50. | High. | 71% Late diagnoses, 42% with advanced/very advanced HIV, 22.6% documented missed opportunities for early diagnosis. |

| Sangaramoorthy et al. (2017), USA 113 | 35, Age: 40–71, 88% between 40 and 59 years, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 32% college or higher education, 28 native-born African Americans, 7 Black African participants | Qualitative. Interviews. Purposive and snowball recruitment. | Perceptions and experiences of HIV-related stigma. | High. | Intersectional stigma is a central feature in lives, at interpersonal, familial/community and institutional/structural levels. Negative responses to gender, age, race and disease. |

| Schneider (1997), France, Germany, Spain, UK 114 | 929, Aged 40–65, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Convenience sampling. | Attitudes towards and use of HRT. | High. | Use of HRT: 18% Spain, 55% France; 38%–61% of women had not discussed menopause or symptoms with HCP; 66% women believed they needed more information about HRT. |

| Sevelius et al. (2014), USA 115 | 58, 20 interviewees, 38 focus group participants, 85% aged 40–59, women who identified as transgender women, 85% African-American/Black, 5% Pacific Islander, 5% Multiracial, 5% Caucasian | Qualitative. Interviews and focus groups. Convenience sample. | Barriers and facilitators to engagement in HIV care among transgender women. | High (triangulation across methods). | Mental health problems, substance use, poverty, transphobia, barriers to care. Avoidance of healthcare due to stigma and past negative experiences, prioritisation of hormone therapy, concern about interactions between hormone therapy and anti-retroviral. Culturally competent, transgender sensitive healthcare powerful facilitator. |

| Sillence et al. (2023), UK 116 | 18 Menopause apps | Qualitative and quantitative. Review analysis. | Quality, feature and written review analysis of menopause apps. | High. | Data reports and visualisations empowered app users to seek out help and facilitated conversations with HCPs. Apps with clear links to HCP support, were viewed positively by app reviewers and all three apps with HCP support had ‘good’ quality scores. Few of the menopause apps were explicitly supported by HCPs. Many apps scored poorly in relation to the credibility of the source. |

| Simon et al. (2013), USA 117 | 3530, Age 55–65 years, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sample. | Postmenopausal women’s knowledge of, and attitudes towards, vaginal atrophy. | High. | 63% Associated vaginal symptoms with menopause; 80% considered vaginal atrophy to negatively affect their lives; 40% Waited 1 year before consulting HCP. |

| Sinko and Saint Arnault (2020), USA 118 | 21, Aged 20–81 (9 aged over 41–50+ and 4 aged 31–40), women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 78% college degree or higher, 86% Caucasian, 11% African American, 1% Asian | Qualitative. Survivor narratives. Convenience sampling. | Explore nature of Gender-based violence healing. | High. | Contextual factors that influence healing: societal expectations, social reactions to self-disclosure, normalisation of violence. Internal themes of shame, self-doubt, self-blame, fear of judgement. Healing: reconnecting with self (reclaiming identity, managing symptoms, regaining control); reconnecting with others (sense of belonging, relating to others); reconnecting with world (releasing negativity, living a purposeful life). |

| Solomon et al. (2021), UK 119 | 661, Aged 45–60, median age 49, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 44% completed University, 72% Black African, 8.4% White UK, 19.4% other | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sampling. | Association between HIV clinic attendance and ART adherence and menopausal symptoms. | High, large study, majority Black African. | Severe menopausal symptoms associated with suboptimal ART adherence and HIV clinic attendance. |

| Strohl et al. (2015), USA 120 | 215, Age range 18–70, average age 50, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 22% married, 38% college graduate or above education, 100% African American/Black | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study: survey. Convenience sampling. | HPV knowledge and awareness. | High (but not generalisable (100% African American/Black)). | Knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer and HPV vaccination was low. |

| Studts et al. (2012), USA 121 | 345, Aged 40–64, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 61.2% married, 95.1% White | Quantitative. Randomised controlled trial, single-blind, two-arm. | Effectiveness of faith-based lay health advisor intervention to improve cervical screening rates in an area of low screening rates. | High (but homogenous study population). | Significantly more likely to have smear if baseline report of recent prior smear. |

| Studts et al. (2013), USA 122 | 345, Ages 40–64, mean age 51, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 64% High-school education or less, 61% Married, 95% Non-Hispanic Caucasian | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study: 88-Item questionnaire (built using qualitative research). Recruited from Churches. Convenience sampling. | Barriers to cervical cancer screening. | Moderate (results not generalisable as recruited from churches and homogeneous ethnicity). | Fear, worry and embarrassment prevented screening. Erroneous beliefs (that a person who has cervical cancer would have symptoms) prevented screening. Lowest perceived income adequacy, lowest perceived health status more likely to report fear of cancer being detected (significant emotional barrier). Access to healthcare facilities, health insurance coverage, cost of testing, limited transport options, lack of physician recommendation/interaction. More likely to screen if could use home kit. |

| Taylor et al. (2017), USA 123 | 50, Ages 50–69, mean age 56, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 48% more than high school education, 90% Black or African American | Qualitative. Interviews and focus groups. Convenience sampling. | Explore importance of sex and sexuality among women living with HIV to identify their sexual health and HIV prevention needs. | High. | Sexual pleasure increases with age. Sexual freedom (from the fear of pregnancy and traditional gender norms – expectations of being in a committed relationship or needing financial support, have more partners, sex when they like). Less pleasurable due to partner and relationship characteristics (partner’s inability to perform, unhappiness with relationships, trapped in sexless relationship). Changes in sexual abilities (physical limitations, increase or decrease in desire, ageing as barrier/improvement to orgasm experience, impact of comorbidities). Sexual risk behaviours (many condomless sex, relationship dynamics important for not practising safe sex). Ageist assumptions about sex lives and serostatus (belief older women should not be sexually active, younger men perceive sex with older women is lower risk behaviour-expectation they can have condomless sex) many fought against these stereotypes. STI prevention for older women living with HIV should promote ways to maintain satisfying and safe sex lives. |

| Thames et al. (2018), USA 124 | 45, Ages 50–80 years, African-American, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Focus groups, followed by community-based conference. Convenience sampling. | Community-based participatory research approach to analyse sexual health behaviours and mental health. | High. | Depression, loneliness and self-esteem issues reasons for engaging in high-risk sexual behaviours. Women did not feel comfortable discussing sexual practices with their physicians, partners, or friends. |

| Tortolero-Luna et al. (2006), USA 125 | 235, 35–61 Years (62% aged between 40 and 61), women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 58% less than high school education, 80% married or co-habiting, Hispanic women (92% from Mexico) | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Survey questions. Univariate and multivariate analysis. Convenience sampling. | Assess how English language use by Hispanic women affects their preferences for participating in decision-making and information seeking regarding medical care. | Moderate (difficult to distinguish between effect of language and effect of culture). | Decreased use of English language associated with less desire to participate in medical decision making. Increased use of English language may influence Hispanic women’s preferences for participating in medical decisions and their information-seeking behaviour. |

| Valanis et al. (2000), USA 126 | 93, 311, Aged 50–79, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender, 40 study centres with range of geographic and ethnic diversity, 85% White but attempted to recruit mixed ethnicity | Quantitative. Cohort study. Questionnaire. Convenience sample. | Compare heterosexual and non-heterosexual women on demographic characteristics, psychosocial risk factors, screening practices, health-related behaviours associated with increased risk of diseases. | Moderate (quality-lower proportion of non-heterosexuals than ideal). | In bisexual and homosexual women: lower cancer screening rates. Lesbian and bisexual women had more risk factors for reproductive cancers. Women reporting never having had sex as adults had lower Pap screening rates and lower rates of HRT use. |

| Van Dommelen et al. (2022), USA 127 | 220, Physicians and advanced practice providers (182 OBGYN, 38 family/internal medicine) | Quantitative. Cross-sectional. Questionnaire. Convenience sampling. | Identify barriers to screening for sexual dysfunction among HCPs. | High. | Primary barrier for OBGYNs time constraints, for primary care provider not having enough knowledge. |

| Vazquez et al. (2007), USA 146 | 440, 43% Over age of 45, 32% aged 35–44, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Survey. Convenience sample. | Women’s perceptions of issues they face with diagnosis of epilepsy. | High (but not generalisable). | 31% of Women with epilepsy knowledgeable about menopause; 28% Discussed menopause with HCP but 52% wanted more info; 48% very concerned about impact of antiepileptic drugs on menopause. |

| Walter et al. (2004), UK 128 | 40, Aged 50–55, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender | Qualitative. Focus groups and interviews. Convenience sampling. | Women’s understanding of risk associated with menopause and HRT. | High (but not generalisable). | Women request unbiased, truthful, summarised, personalised, information. Barriers to optimal risk communication and decision making were lack of HCP time, GP attitudes and poor communication. |

| Walters et al. (2021), USA 129 | 35, 31% Aged 36–50, 50% aged over 50, 32 cisgender, 3 transgender, 37% Heterosexual, 31% some college or more (education), 46% Hispanic/Latina, 46% Non-Hispanic Black, 9% Non-Hispanic White | Qualitative, interviews. Purposive recruitment. | Barriers and facilitators to HIV PrEP education intervention. | High. | 51% Had previously heard about HIV PrEP (although many had behaviours that would put them at risk of HIV). Facilitators: offering other health and social services as well, women-focused approach, peer-outreach and navigation. Barriers: concerns about side-effects or interactions, concurrent health-related conditions or appointments, insecure housing and travel, caring responsibilities. |

| Watts and Jen (2023), USA 130 | 27, Aged 39–57, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 70% in long-term relationship, 74% heterosexual, 7% lesbian, 11% bi- or pan-sexual, 4% gender fluid, 4% asexual, 80% bachelor or postgraduate degree, 59% White ethnicity, 11% White Jewish, 15% mixed ethnicity, 1% Asian, 1% Latina, 1% no race given | Qualitative. Interviews. Purposive and snowballing recruitment. | Investigate perceptions and interpretations of midlife women’s sexual experiences and changes about sexual engagement, unwanted sexual experiences, body image, sexual healthcare. | High. | Increasing age and sexual-minority group associated with worse healthcare experiences. New lack of sexual desire: sometimes loss, sometimes relief. Relieved to no longer feel like sexual objects. After divorce-renewed sense of autonomy over sexual experiences, renewed interest in sex with new partners. Interdependence between their sexual experiences and other important people in their lives. Growth in sexual expression-increasing awareness of own sexual needs. Legacy of unwanted sexual experiences. Overwhelmingly negative healthcare experiences, felt dismissed, ageist, sexist or heterosexist attitudes – deep scepticism of HC system’s ability to meet needs. Representation matters – want more women and more minorities as providers. Those who also worked as HCPs expressed concern that there is very little training for HCPs about needs of midlife women. Positive experience if provider normalised age-related changes and provided honest and direct communication. |

| Weng et al. (2001), UK 131 | 581, Aged 45–54, women, gender not specified, presumed cisgender | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study. Convenience sample. | Factors associated with physician recommendation of HRT. | High. | Black women significantly less likely than White women to report being advised about HRT. |

| Wigfall et al. (2011), USA 132 | 2027, Aged 50–64, women, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, 6 deep-South States, majority had college or higher education level, majority Non-Hispanic White, but good Non-Hispanic Black representation | Quantitative. Cohort study. Convenience sample. | HIV testing uptake among postmenopausal women. | High. | 26% Had ever had HIV test (excluding blood donation testing); 14% had most recent test during post-reproductive years. Women aged 50–54 were 25% as likely to have been tested for HIV as women 60–64. Non-Hispanic White women were half as likely as Non-Hispanic Black women, and rural women 30% as likely as urban women, to have had most recent test during post-reproductive years. |

| Wilson et al. (2013), USA 133 | 10, Ages 28–55 years, women who identify as transwomen, African-American | Qualitative. In-depth interviews. Convenience sampling. | Barriers and facilitators to HIV care and support services. | Moderate(demographic details (age in particular) unclear, all participants same ethnicity). | Gender-related stigma: socially excluded and isolated; peer distrust; institutional distrust-negative experiences in HIV care system. Facilitators: instrumental support (incentives to meet their basic needs), emotional and informational support, access to gender-related care. Transportation and safe and anonymous location of services. Social connectedness. |

| Wong et al. (2018), Hong Kong 29 | 40, Age 42–65 years, gender identity not specified, presumed cisgender, Chinese Cantonese | Qualitative. Interviews. Convenience sampling. | Impact of menopause on sexual health. | High. | Lack of information – suggestion to give information specifically about sexual health (how physical and emotional changes influence sex life and strategies) instead of general menopause symptoms. Cultural taboos – lack of open dialogue about sex and menopause – unsure what is ‘normal’. Seminars, pamphlets for women, documentaries, storytelling programmes, adverts, newspapers/magazines useful sources of information. Financial constraints to seeking healthcare. |

CASP, Critical Appraisal Checklists; HCP, healthcare professionals; HPV, human papilloma virus; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; SHSW, sexual health and sexual well-being; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Study locations

Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (46), and the United Kingdom (17), with the remaining being conducted in Canada (7), Australia (2), Hong Kong (1), Israel (2), Spain (1), Italy (1), Ireland (1), Spain and Serbia (1), England, Finland, Denmark, New Zealand, Australia and United States (1) and Europe (1).

Design of included studies

Studies included in the review were quantitative (45), qualitative (30) and mixed methods (six). Of those using qualitative methods, nine employed focus group discussions, 16 used interviews, four used both focus group discussions and interviews and one was a qualitative content analysis. Of those employing quantitative methods, one was a review analysis, 10 were cohort studies, 32 were cross-sectional studies and two were randomised trials. Mixed methods trials included cross-sectional studies linked with interviews (three) or interviews (one) and focus groups (one), a cohort study linked with interviews (one) and a mixed quantitative and qualitative content analysis (one).

Study samples

Most studies (60) were presumed to have been conducted on cisgender women, although this was not specifically documented. Ten studies were conducted on transgender women. Three studies were conducted on both transgender and cisgender women. Eight studies were conducted on HCPs.

Recruitment methods

Convenience sampling was the most common method of recruitment (51), followed by purposive sampling (20). Four studies used a mixture of purposive and snowballing sampling, one study used convenience and snowballing sampling, four studies used randomised sampling, one study used ‘mixed recruitment’.

Quality assessment