Abstract

Vertically transmitted endogenous retroviruses pose an infectious risk in the course of pig-to-human transplantation of cells, tissues, and organs. Two classes of polytropic type C porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) which are infectious for human cells in vitro are known. Recently, we described the cloning and characterization of replication-competent PERV-B sequences from productively infected human cells (F. Czauderna, N. Fischer, K. Boller, R. Kurth, and R. R. Tönjes, J. Virol. 74:4028–4038, 2000). Here, we report the isolation of infectious molecular PERV-A and PERV-B clones from pig cells and compare these proviruses with clones derived from infected human 293 cells. In addition to clone PERV-A(42) derived from 293 cells, four “native” full-length proviral PERV sequences derived from a genomic library of the porcine cell line PK15 were isolated. Three identical class A clones, designated PK15-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(45), and PK15-PERV-A(58), and one class B clone, PK15-PERV-B(213), were characterized. PK15-PERV-B(213) is highly homologous but distinct from the previously described clone PERV-B(43). PK15-PERV-A(58) demonstrates close homology to PERV-A(42) in env and to PERV-C in long terminal repeat, gag, and pro/pol sequences. All three PERV clones described here were replication competent upon infection of susceptible cell lines. The findings suggest that the pig genome harbors a limited number of infectious PERV-A and -B sequences.

A better understanding of the cellular and molecular basis of transplant rejection and the generation of transgenic donor animals bearing genes that mediate protection towards rejection (3, 24, 25) have stimulated approaches to use xenotransplantation, i.e., the therapeutic use of animal cells, tissues, and organs, to overcome the shortage of allogeneic transplants (7). Pigs are preferred as donors for xenotransplants (10).

Major concerns have been raised about the possibility of introducing new microbial agents from the animal into the recipient, leading to xenozoonosis (2, 11, 18, 27). Viruses that are germ line transmitted, i.e., porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) (21), and DNA viruses that can persist without symptoms in their natural host and are transmitted via intrauterine or transplacentar pathways, e.g., herpesviruses (8), are of particular interest.

Approximately 50 integration sites of PERV exist in the genomes of different pig breeds (1, 14, 21), and at least three classes are known (14, 28). Those classes, named PERV-A, -B, and -C (PERV-C is also known as PERV-MSL), display high sequence homology in the genes for group-specific antigens (gag) and polymerase (pol) but differ in the envelope (env) genes which determine the host range. In addition, the existence of multiple other PERV sequences in domestic pigs and their phylogenetic relatives has been described. However, only classes A, B, and C appear to be infectious (22).

PERV that are released from different pig cell lines are able to infect human cells in vitro (15, 32, 33). PERV-C (1) is ecotropic compared to PERV-A and PERV-B, which are polytropic as deduced from pseudotype experiments utilizing the corresponding env genes (28).

A retrospective investigation of 160 patients who had been treated with porcine cells and tissues showed no evidence for transmission of PERV (20); however, no long-term transplantation of a whole vascularized organ has been attempted so far. In contrast, a recent study utilizing NOD/SCID mice revealed PERV infection in several tissue compartments after transplantation of pig pancreatic islets, indicating the xenozoonotic potential of those retroviruses (31).

Recently, we have reported the isolation of replication-competent PERV-B molecular clones derived from human embryonic kidney cells infected with PERV (293 PERV-PK) (5). In this communication, we describe the cloning and characterization of PERV-A and PERV-B proviral sequences derived from the porcine kidney cell line PK15 as well as the characterization of the molecular clone PERV-A(42); isolated from 293 PERV-PK cells (5). [Hereafter, clones derived from cell line 293 PERV-PK will be designated 293-PERV-B(33), 293-PERV-B(43), and 293-PERV-A(42); clones derived from cell line PK15 will be designated PK15-PERV-A(58), and so on.] Three proviruses, one PERV-B and two PERV-A clones, produce infectious and replication-competent particles upon transfection of susceptible cells and subsequent infection of different human cell lines. Thus, this study provides the first functional PERV-A and PERV-B clones isolated directly from the pig genome and allows the comparison of proviral PERV sequences from different origins at the molecular and cellular level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and replication studies.

The cell lines PK15 and 293 were kindly provided by R. Weiss (London, England). HeLa, D17, and PG-4 cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures. For the generation of producer cells, plasmid DNA was prepared by utilizing the EndoFree system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 1 to 5 μg of DNA was transfected into cells with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). Infectivity was tested by inoculation of semiconfluent cultures of susceptible cell lines with cell-free supernatants of producer cells after filtration through 0.45-μm-pore-size membranes (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). Viral replication was detected by reverse transcriptase (RT) assays and immunofluorescence microscopy with PERV-specific antibodies (13).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Human 293 and HeLa cells as well as canine D17 cells and feline PG-4 cells were infected with PERV and fixed 48 to 72 h post infection (p.i.) with 2% formaldehyde. Indirect immunofluorescence analyses were performed as described previously with PERV-specific antisera directed against the nucleocapsid (p10) (13).

RT assay.

Membrane-filtered cell-free supernatants of transfected and infected cell lines were tested for RT activity by employing the C-type RT activity assay (Cavidi Tech Ab, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions (protocol B).

Detection of integrated PERV.

Genomic DNA was isolated from different cell lines grown to confluence by standard procedures (23). Proviral integration of PERV was tested by PCR of pro/pol sequences with oligonucleotides PK1 (5′-TTGACTTGGCAGTGGGACGGGTAAC-3′; nucleotide [nt] 2886 to 2910) and PK6 (5′-GAGGGTCACCTGAGGGTGTTGGAT-3′; nt 3700 to 3677) in a first amplification and PK2 (5′-GGTAACCCACTCGTTTCTGGTCA-3′; nt 2905 to 2927) and PK5 (5′-CTGTGTAGGGCT TCGTCAAAGATG-3′; nt 3657 to 3634) in a nested amplification. Nucleotide positions refer to those for 293-PERV-A(42).

Identification of ORF.

Isolated PERV sequences were tested for open reading frames (ORF) by means of the protein truncation test using the TNT T7 Quick-Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Gene sequences for gag, pol, and env were amplified in conjunction with a T7 promoter using oligonucleotides T7-PERV-gag-for (5′-CTTGTGCGTCCTTGTCTACAG-3′; nt 1087 to 1107), PERV-gag-rev (5′-CTTCAAAGTTACCCTGGGCTCG-3′; nt 2737 to 2716), T7-PERV-pol-for (5′-GCTACAACCATTAGGAAAAC-3′; nt 2794 to 2813), PERV-pol-rev (5′-GAGTTCGGGCTGTCCACAAGG-3′; nt 6304 to 6284), T7-PERV-env-for (5′-CCACTAGACATTTGAAGTTC-3′; nt 6116 to 6136), and PERV-env-rev (5′-GTTAATAGTTCTAATCTTAGAAC-3′; nt 8163 to 8141). Nucleotide positions refer to those for 293-PERV-A(42).

Generation and screening of porcine and human λ bacteriophage libraries.

A genomic DNA library from PK15 cells was constructed utilizing the λ FixII/XhoI partial fill-in vector (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) as described previously (5). The generation of a genomic library from cell line 293 PERV-PK has been reported as well as the screening of bacteriophage libraries with a 32P-labeled PERV pro/pol probe (5). Subcloning of DNA inserts from purified λ clones into pBS-KS (Stratagene) was done as previously described (5).

Differentiation of PERV classes by PCR.

To distinguish PERV-A and PERV-B proviral sequences, envA- and envB-specific oligonucleotide primers were employed in PCR experiments. Oligonucleotides used are envA-for (5′-CAATCCTACCAGTTATAATCAATT-3′; nt 6638 to 6661), envA-rev (5′-TCGATTAAAGGCTTCAGTGTGGTT-3′; nt 7334 to 7311), envB-for (5′-GTGGATAAATGGTATGAGCTGGGG-3′; nt 6711 to 6734), and envB-rev (5′-CTGCTCATAAACCACAGTACTATA-3′; nt 7287 to 7264). Nucleotide positions for envA and envB refer to those for 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-B(213), respectively.

PCR amplification of PERV LTRs.

Proviral long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences were amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 5′-PERV-LTR I (5′-TGAAAGGATGAAAATGCAACCTAAC-3′; nt 1 to 25), priming at the 5′ end of the U3 region, and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I (5′-TTTCCCGGCCAACGCACCAAATGA-3′; nt 728 to 705), located at the primer binding site of PERV. Nucleotide positions refer to those for 293-PERV-B(33) (5).

Sequence analyses.

The DNA sequences of both strands of molecular clones were determined by primer walking as described previously (5) with an ABI 373A or 377 DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213) have been deposited at GenBank under accession numbers AJ133817 (5), AJ293656, and AJ293657, respectively. Sequences used for homology analyses are 293-PERV-B(33) (AJ133816), 293-PERV-B(43) (AJ133818) (5), and PERV-C (AF038600) (1).

RESULTS

Cloning of PERV sequences from human and pig cells.

One proviral clone, 293-PERV-A(42), which had been isolated from a genomic DNA library of 293 PERV-PK cells (5), was further characterized. In addition, a DNA library from the porcine cell line PK15, which releases infectious PERV particles (21), was established and screened to isolate “native” (i.e., derived from the pig genome) proviral sequences.

After three rounds of screening, 68 clones from the PK15 library were purified to homogeneity. Differentiation of these clones by PCR utilizing primers specific for envA and envB genes revealed 41 PERV-A clones and 10 PERV-B clones, respectively. The remaining 17 clones yielded neither envA, envB, envC, nor envD amplificates in PCR experiments (data not shown). These clones were considered deficient of the appropriate env gene sequences and were excluded from further analysis.

The PERV-A and PERV-B sequences derived from PK15 cells were investigated for the presence of proviral ORF by protein truncation test analyses (data not shown). Most of the isolated clones were truncated in either one or more of the three ORF except for three class A clones, λPK15-PERV-A(42), λPK15-PERV-A(45), and λPK15-PERV-A(58), and one class B clone, λPK15-PERV-B(213), that demonstrated all three reading frames. Restriction enzyme analyses, partial sequencing, and PCR analyses revealed that the three PERV-A sequences are integrated at the same site in the porcine genome, indicating that these clones represent the same provirus (data not shown). Thus, only clone λPK15-PERV-A(58) was chosen for further experiments and was designated pPK15-PERV-A(58) after subcloning into pBS. Clone λPK15-PERV-B(213) was further analyzed after subcloning of the corresponding λ insert, yielding plasmid pPK15-PERV-B(213).

Analyses of full-length PERV sequences.

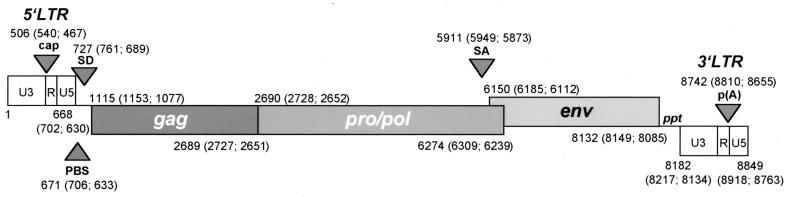

For further characterization of the genomic structure, proviral PERV sequences were determined. Clone 293-PERV-A(42) and clone PK15-PERV-A(58) display sequences of 8,849 and 8,918 bp in length, respectively. The gag gene of 293-PERV-A(42) starts at nt 1115 and is colinear with the pro/pol ORF (nt 2690 to 6274) (Fig. 1). The amber stop codon (UAG) at nt 2689 separating both genes is suppressed by tRNAGln as described previously (1, 5). The env gene partially overlaps with pro/pol (nt 6150 to 8132) and forms a new reading frame. PK15-PERV-A(58) shows a similar structure encompassing the genes for gag (nt 1153 to 2727), pro/pol (nt 2728 to 6309), and env (nt 6185 to 8149). PK15-PERV-B(213) displays a sequence of 8,763 bp and shows ORFs for gag (nt 1077 to 2651), pro/pol (nt 2652 to 6239), and env (nt 6112 to 8085). Comparison of the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the class A clone PK15-PERV-A(58) with 293-PERV-A(42) and the class B clone PK15-PERV-B(213) with the previously described 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) (5) revealed high homology scores which are listed in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Structures of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213). Proviral sequences of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213) are 8,849, 8,918, and 8,763 bp in length, respectively. Genes are shown as open boxes, and the first and last nucleotides of the LTR and genes are given [numbers in parentheses are nucleotide positions for PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213), respectively]. Arrowheads indicate the transcriptional start site (cap), the primer binding site (PBS), the splice donor (SD), the splice acceptor (SA), and the poly(A) addition site [p(A)]. The nucleotide positions correspond to those of molecular clone 293-PERV-B(33) (accession no. AJ133516).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of nucleotide and amino acid sequences of PERV LTR, gag, pro/pol, and env ORFa

| Virus | % Nucleotide homology (% amino acid homology)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTR | gag | pro/pol | env | |

| 293-PERV-A(42) | 63.4 | 95.4 (95.8) | 97.2 (97.4) | 98.1 (98.3) |

| 293-PERV-B(33) | 79.9 | 99.4 (99.2) | 99.7 (99.6) | 99.6 (99.2) |

| 293-PERV-B(43) | 99.0 | 99.5 (99.4) | 99.7 (99.3) | 99.6 (99.1) |

Homology scores were revealed with DNASIS sequence analysis software (Hitachi). 293-PERV-A(42) was compared to PK15-PERV-A(58); 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) were compared to PK15-PERV-B(213).

All three proviral PERV clones show highly conserved amino acid motifs of mammalian type C retroviruses (1, 5) as summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Highly conserved amino acid motifs of mammalian type C retroviruses present in 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213)

| Protein | Consensus sequence | PERV sequence | Nucleotide positiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| N terminus of Gag | Asn1-Met1-Gly2-Gln3-Thr4b | Identical | 1115–1127; 1153–1165; 1077–1089 |

| N terminus of p30 | Prolinec | Identical | 1697–1699; 1735–1737; 1659–1661 |

| C terminus of p30 | Thr-Lys-X-Leu | Thr-Lys-Ile-Leud | 2463–2475; 2501–2513; 2425–2437 |

| Cys-His box in p10 | Cys-Xaa2-Cys-Xaa4-His-Xaa4-Cyse | Identical | 2592–2634; 2630–2672; 2554–2596 |

| Aspartyl protease | Leu-Leu/Val-Asp-Thr-Gly-Ala-Asp-Lysf | Leu-Val-Asp-Thr-Gly-Ala-Glu/Lys-Hisg | 2762–2785; 2724–2747; 2800–2823 |

| RNA-dependent polymerase (RT) | Tyr-X-Asp-Asp (YXDD)h | Tyr-Val-Asp-Asp (YVDD) | 3557–3569; 3597–3609; 3521–3533 |

| Cleavage site gp70-p15E | Arg/Lys-X-Lys-Argi | Arg-Pro-Lys-Arg | 7525–7537; 7560–7572; 7478–7490 |

Motifs of retroviral consensus sequences (nucleotide positions) are given for 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PERV-B(213), respectively.

Reference 19.

Identical in BaEV (accession no. D10032), GaLV (accession no. NC_001885), and KoRV (accession no. AF151794).

f Reference 4.

g In PK15-PERV-A(58), the seventh amino acid is lysine.

h Reference 34.

PK15-PERV-B(213) harbors the longest pro/pol gene. The gene bears one more codon (nt 6234 to 6237, coding for glutamine) than pro/pol of 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-A(58) and one more codon (nt 5951 to 5953, coding for arginine) than PK15-PERV-A(58). Likewise, in the pro/pol of 293-PERV-A(42), one more arginine (nt 5989 to 5991) is found than in PK15-PERV-A(58). Thus, PK15-PERV-A(58) bears the shortest pro/pol gene.

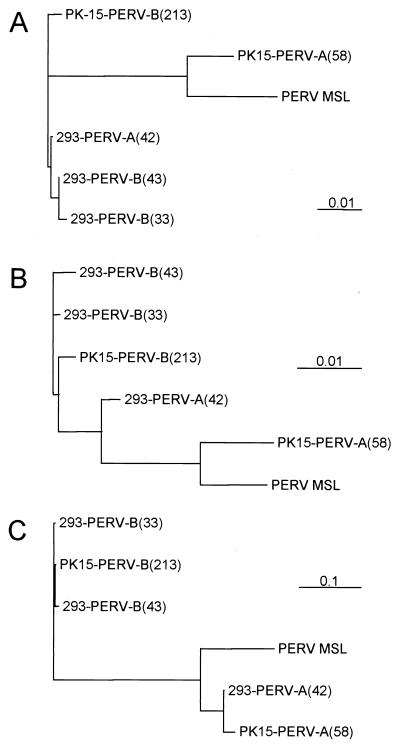

The env gene of PK15-PERV-A(58) demonstrates a curtailment of 18 nt compared to 293-PERV-A(42) (nt 8115 to 8132) at the 3′ end of the sequence. The class-specific differences of PERV-A and PERV-B are also reflected by the difference in length between the env sequences of PK15-PERV-B(213) and 293-PERV-A(42) (1,973 and 1,982 nt, respectively). Furthermore, an insertion of 4 nt was found in the 5′ untranslated region of PK15-PERV-A(58) (nt position 787 to 790). Phylogenetic analyses of the amino acid sequences derived from clones PK15-PERV-A(58), PK15-PERV-B(213), and 293-PERV-A(42) and the corresponding ORF of previously described PERV sequences (1, 5) reflect their relationship (Fig. 2). For Gag, a clustering of the clones derived from human 293 cells was revealed, whereas Gag of PK15-PERV-A(58) is more closely related to Gag of PERV-C than to Gag of PK15-PERV-B(213) (Fig. 2A). The Pro/Pol sequences are distributed according to the appropriate class of PERV (Fig. 2B). The native clone PK15-PERV-B(213) is closely related to clones 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43). However, the two PERV-A clones show a higher level of divergence for Pro/Pol. Env shows the expected class-like distribution (15) where the class B sequences form one branch (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, clones 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-A(58) are located proximal to PERV-C in Env. PERV-C demonstrates general proximity to PK15-PERV-A(58) for all three ORF.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of PERV proteins. Phylograms are based on full-length ORF for Gag (A), Pro/Pol (B), and Env (C) (see also Table 1). Relative distances are indicated by scale bars (0.1, 10% divergence). Phylograms were generated with PHYLIP 3.574c (Prodist and Neighbor programs) (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html).

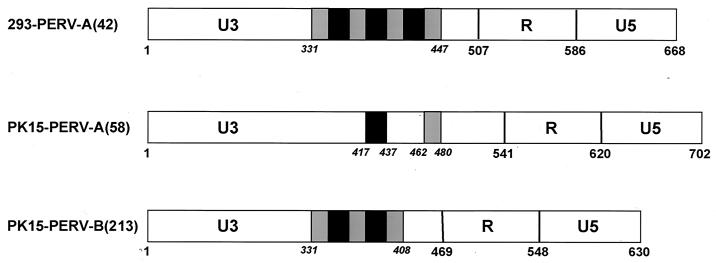

Features of LTR sequences.

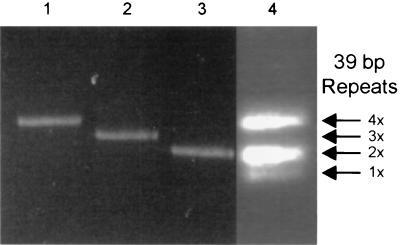

Major differences were found in the LTRs of PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213) (Fig. 3). The LTRs of these proviral PERV are limited by the inverted repeat sequence TGAAAGG/CCTTTCA, as described for the previously characterized clones 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) (5). Furthermore, a box of 39-bp repeats is found in the U3 region of 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-B(213), each repeat consisting of subrepeats of 21 and 18 bp. For 293-PERV-A(42), three consecutive repeats ranging from nt 331 to 447 are found. The LTR of PK15-PERV-B(213) exhibits two repeats (nt 331 to 408). In both LTRs, an 18-bp repeat is found preceding the triplex and duplex repeat box, respectively. Thus, the LTR of PK15-PERV-B(213) resembles the LTR of molecular clone 293-PERV-B(43) (reference 5 and Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Schematic structure of the 5′ LTRs of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PERV-B(213). The LTRs are 668 [293-PERV-A(42)], 707 [PK15-PERV-A(58)], and 630 [PK15-PERV-B(213)] bp long. Repeats consisting of 18- and 21-bp subrepeats are indicated as black and grey boxes, respectively.

The LTR of PK15-PERV-A(58) harbors one 21-bp and one 18-bp subrepeat, both showing two nucleotide exchanges, which are separated from each other (nt 417 to 437 and nt 462 to 480, respectively) (Fig. 3). Comparison with the LTR of 293-PERV-A(42) revealed a homology of 63.4% (Table 1).

Analysis of PERV expression and replication.

Genomic DNA extracted from cell lines infected with PERV was investigated for the presence of integrated pro/pol sequences by PCR amplification. All cell lines used in infection studies, 293, HeLa, D17, and PG-4, showed the expected 753-bp amplification product after infection (data not shown).

As different cell lines have been described as being susceptible to PERV infection (28), the ability of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213) to productively infect cells was investigated by indirect immunofluorescence analyses with a PERV-specific Gag p10 antiserum (13). Distinct signals, although with different intensities, were obtained for all three viruses as well as cell lines tested p.i. after incubation with p10 antibody (data not shown). 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-A(58) showed significant Gag expression 8 to 12 days p.i. in all cell lines, similar to the pattern found for 293 cells after infection with molecular clone 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG (reference 13 and data not shown). PK15-PERV-B(213), however, showed a lower degree of Gag expression (data not shown).

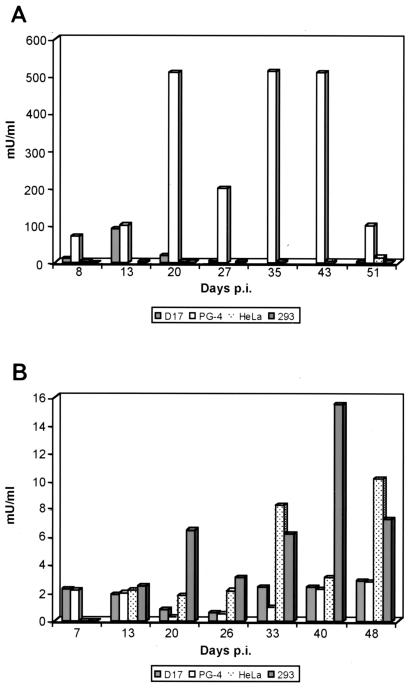

To confirm the presence of infectious and replication-competent viral particles, RT activities in the supernatant of cell lines were determined in the course of infection with PERV. Cell-free supernatants from D17, PG-4, HeLa, and 293 cells that had been infected with PERV derived from 293 or HeLa producer cells subsequent to transfection with either of the molecular clones 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), or PK15-PERV-B(213) were collected up to 51 days p.i.

In the case of clone 293-PERV-A(42), RT activity of up to 500 mU/ml was found for PG-4 cells infected with PERV derived from transfected HeLa producer cells (Fig. 4A), where the virus stock used had a titer of 4 mU/ml (data not shown). Furthermore, after infection of D17 cells with the same virus stock 293-PERV-A(42) initially demonstrated an activity of 100 mU/ml (day 13), which declined from day 20 on. Conversely, virus 293-PERV-A(42) demonstrated weaker RT activity on 293 cells and on HeLa cells at day 51 p.i. Clone PK15-PERV-A(58) demonstrated RT activities in a range of 2 to 15 mU/ml on different cell lines (Fig. 4B). In contrast to clone 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58) showed elevated levels of activity (15 mU/ml after infection with virus derived from 293 cells that were transfected with this clone) on 293 cells at day 40 p.i. PK15-PERV-B(213) demonstrated RT activities similar to PK15-PERV-A(58) upon infection of 293 and HeLa cells (data not shown). For 293 cells infected with PERV derived from HeLa producer cells that had been originally infected with PK15-PERV-B(213) derived from transfected 293 cells, a transient activity of up to 4 mU/ml was detected at day 21. The HeLa producer cells showed RT activities ranging from 2 to 4 mU/ml until day 48. All other cell lines, HeLa, PG-4, and D17, were infected with PK15-PERV-B(213) derived from transfected 293 producer cells and revealed activities <1 mU/ml (data not shown). Supernatants used for infection showed activities of 1 to 2 mU/ml in the case of PK15-PERV-A(58) and of 4 mU/ml in the case of PK15-PERV-B(213) (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Replication of 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-A(58). RT activity in cell-free culture supernatants of 293-PERV-A(42)-infected (A) and PK15-PERV-A(58)-infected (B) cells. Cell lines 293, HeLa, D1, and PG-4 were studied for up to 51 days p.i. MoMLV RT was used as a standard. Note the different scales of panels A and B.

DISCUSSION

Recently, we have reported the cloning of full-length, replication-competent PERV-B proviral sequences derived from infected human 293 cells (293 PERV-PK) (5). These data, in addition to the characterization of a PERV-C proviral sequence (1), demonstrate that the pig genome harbors intact proviruses similar to those found in several other species (30).

Here, we present the first structural and functional description of two proviral sequences, PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213), isolated from the porcine cell line PK15. In addition, the characterization of a clone, 293-PERV-A(42), isolated from a human 293 cell line productively infected with PERV (293 PERV-PK), is presented. All three proviruses bear replicative capacities. Isolation of these clones allows to compare native and “humanized” (i.e., cloned from infected human cells) PERV sequences at molecular and cellular levels.

All three molecular clones described here show the same proviral structure as the previously characterized clones 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) (5). Amino acid exchanges compared to the humanized clones are mainly found in PK15-PERV-A(58) as indicated in Fig. 2. For Gag and Pro/Pol of PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213), those differences are scattered along the sequences. Exchanges found in the Env of PK15-PERV-A(58) mostly occur in the transmembrane (data not shown), and most of these differences are neutral. The impact of the remaining exchanges on the replicative capacity of the virus needs to be evaluated.

The polymorphisms found in 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213) have an impact neither on the highly conserved motifs in pro/pol for mammalian type C retroviruses (Table 2) nor, in the case of PK15-PERV-A(58), on the regions in the env genes which are important for the determination of the host range (VRA, VRB, and PRO) (14).

As defined for other type C retroviruses like gibbon ape leukemia virus (GaLV) (9), the C-terminal end of the Env protein comprises the putative R peptide in 293-PERV-A(42) (nt 8079 to 8129), PK15-PERV-A(58) (nt 8114 to 8149), and PK15-PERV-B(213) (nt 8032 to 8082). However, the putative R peptide of 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-B(213), and the published proviruses 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) (5) appears to be 17 amino acids (aa) in length compared to 16 aa in GaLV (9). Studies with truncated forms of the R peptide of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) indicated that up to 7 aa from the C-terminal end could be deleted without a detectable effect on the fusion activity of Env (35). However, since the curtailment of the cytoplasmic tail of PK15-PERV-A(58) Env comprises only 6 aa, no tendency for fusion activity was found in cells infected with this virus (data not shown).

As clones 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-A(58) both show lower degrees of homology than the class B clones (Table 1), the LTR of PK15-PERV-A(58) demonstrates a different structure within the U3 region compared to 293-PERV-A(42) and PK15-PERV-B(213) (Fig. 3). The LTR U3 regions of these two clones and of the two previously reported proviruses 293-PERV-B(33) and 293-PERV-B(43) (5) contain different numbers of a 39-bp repeat box which consists of two subrepeats (18 and 21 bp). 293-PERV-A(42) displays a triplicated box, and PK15-PERV-B(213) bears a duplicated box. Thus, the repeat boxes appear to be variations on a basic theme. In contrast, the subrepeats are separated from each other in the U3 of PK15-PERV-A(58) (Fig. 3) and show two nucleotide exchanges per subrepeat. A preliminary analysis of the 39-bp repeat revealed that it contains motifs for nuclear binding factors (G. Scheef et al., submitted for publication), similar to repeat structures in the LTR of MoMLV (16). In addition, as there appears to be a direct correlation between the number of repeats in U3 and the transcriptional activity (Scheef et al., submitted), it is conceivable that the disruption of the repeat, as found in PK15-PERV-A(58), has an impact on the transcriptional acitvity of the LTR and thus on the level of replicative capacity of this clone. The question of whether the U3 structure found in PK15-PERV-A(58) can give rise to the structure observed in proviruses 293-PERV-A(42), 293-PERV-B(33), 293-PERV-B(43), and PK15-PERV-B(213) is presently under investigation in our laboratory. However, PCR analysis of genomic DNA of PK15 cells revealed that no proviral LTR exists in these cells that is identical to the one found in clone 293-PERV(42), which bears three 39-bp repeats (Fig. 5). Thus, it is conceivable that this clone is a recombination product. On the other hand, taking into account the divergence between the two class A clones, it is unlikely that 293-PERV-A(42) is derived from PK15-PERV-A(58) (Table 1).

FIG. 5.

Presence of PERV LTR in PK15 cells. LTRs containing distinct numbers of a 39-bp repeat exist in molecular clones 293-PERV-B(33) (lane 1), 293-PERV-A(42) (lane 2), and 293-PERV-B(43) (lane 3). Proviral LTRs in the genome of PK15 cells show variable numbers of 39-bp repeats (lane 4). Arrows indicate the multiplicity of 39-bp repeats in U3.

The capacity of the viruses 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213) to infect different cell lines was revealed by PCR amplification of integrated proviral copies and by detection of Gag expression (data not shown) and viral particles in cell-free supernatants of infected cells by RT assays (Fig. 4). Several cell lines have been reported to be susceptible to infection with PERV, including human 293 cells (21, 28). None of the PERV clones described here showed high levels of RT activity on 293 cells [15 mU/ml for 293-PERV-A(58) and 4 mU/ml for PK15-PERV-B(213)] (Fig. 4 and data not shown).

In contrast to our results, pseudotype experiments utilizing PERV-A, PERV-B, and PERV-C env sequences indicated a more efficient entry for PERV-A env with 293 and HeLa cells (28). However, this study concentrated on the tropism of PERV and not on replicative capacity. The pseudotype analyses utilized only the env genes and did not take into account interactions between the host and the virus and regulatory elements as present, e.g., in the proviral LTR. For the infectivity studies based on biological separation of PERV class A, B, and C clones presented in the same report, no RT values are given (28). Hence, it cannot be ruled out that the genetically cloned proviruses derived from PK15 cells described here are identical with the biologically cloned PERV.

The most susceptible cell line for 293-PERV-A(42) in this study is the feline cell line PG-4 (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, lower-level but transient activity was found for canine cells (D17) (Fig. 4A), which is in accordance with the host range study (28).

PK15-PERV-A(58) showed a significantly lower activity of up to 3 logarithmic scales than 293-PERV-A(42) and, except for 293 cells, only transient and low activity was observed for the other cell lines investigated (Fig. 4B). It cannot be ruled out that the selected producer cell line (293) has an influence on the RT activity found for the clone PK15-PERV-A(58) on 293 cells. However, as the 293-PERV-A(42) virus stock used to infect PG-4 cells was derived from HeLa producer cells, an adaptation seems not to have much impact on the time scale of the experiments.

Infection studies with clone PK15-PERV-B(213) revealed low levels of activity on HeLa cells and transient levels of activity on 293 cells (data not shown). All other cell lines tested revealed very low activity levels for PK15-PERV-B(213) (data not shown). However, as published data show RT activities of 0.1 mU/ml after infection of 293 cells with PK15 derived PERV (virus stock activity of 1.6 mU/ml) (31), the activities described here for PK15-PERV-A(58) and PK15-PERV-B(213) clearly demonstrate the replication-competence of these clones.

Based on the high homology between PK15-PERV-B(213) and the previously described 293-PERV-B(43) (Table 1), it is likely that PK15-PERV-B(213) represents the porcine ancestor of clone 293-PERV-B(43), which was isolated from infected 293 cells. However, a deletion of 12 bp exists in the 5′ untranslated region between the LTR and the gag gene of 293-PERV-B(43) [nt 753 to 764 in PK15-PERV-B(213)], which might have an impact on the infectivity of the virus. Furthermore, as serial passaging through human cell lines is a selection for viruses that are more infectious for human cells (28), it is conceivable that PK15-PERV-B(213) demonstrates different properties than 293-PERV-B(43). The latter virus resulted from cocultivation experiments of PK15 and 293 cells (21) rather than from transfected proviral DNA. Furthermore, 293-PERV-B(43) has been in culture for longer periods of time and may have been subjected to recombination and adaptation processes.

A comparison of the proteins of different PERV, including PERV-C (1) and clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG and 293-PERV-B(43) (5), as well as the clones 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), and PK15-PERV-B(213) described here, revealed different assignments of individual clones by phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2). In the case of Gag, the humanized clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG, 293-PERV-B(43), and 293-PERV-A(42) are clustered whereas the native clones PK15-PERV-A(58), PK15-PERV-B(213), and PERV-C are located on different branches. Thus, it appears that the selection achieved by serial passages of PERV on human cells (5, 21) has favored a certain type of Gag (Fig. 2A) or, vice versa, that a certain Gag is an advantage for the productive infection of human cells. In regard of the class-specific assignment, particularly for the class B clones, it could be speculated based on Pro/Pol sequences that the different PERV-B clones have arisen from one ancestral provirus (Fig. 2B). This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that the Env sequences of 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG, 293-PERV-B(43), and PK15-PERV-B(213) are phylogenetically very closely related (Fig. 2C).

As indicated in Table 1, PK15-PERV-A(58) reveals an overall lower level of homology than 293-PERV-A(42), which is reflected by the phylogenetic distances of Gag and Pro/Pol (Fig. 2A and B). PK15-PERV-A(58) is more closely related to PERV-C (gag, 97.6%; pro/pol, 97.5%) with exception of env (69.3%), for which PK15-PERV-A(58) demonstrates a closer relationship to 293-PERV-A(42) (Fig. 2C). Thus, it appears that PK15-PERV-A(58) forms a major group with PERV-C, irrespective of the env sequence. When the Env sequences of all class A and class B clones were aligned (data not shown), PERV-C revealed deletions of the putative VRA and VRB region, suggesting that these PERV-C sequences have evolved from a class A predecessor that shows closest homologies to clone PK15-PERV-A(58).

In this communication, we describe the cloning and the structural and molecular characterization of two replication-competent full-length proviral PERV-A and PERV-B clones derived from the pig genome. Furthermore, the functional characterization of a PERV-A clone derived from infected human cells is presented. The two native clones revealed productive infection on different cell lines, however only at low levels. The fact that the LTR of clone 293-PERV-B(43) has an almost identical counterpart in the pig genome, represented by PK15-PERV-B(213), suggests that this LTR, bearing two 39-bp repeats (Fig. 3), is not the result of an adaptation process to a new host, but an original, (i.e., native) sequence. This finding is confirmed by the independent isolation of a proviral LTR that is closely related to the LTR of 293-PERV-A(42) from a genomic porcine library cloned in bacterial artificial chromosomes (reference 30 and M. Niebert et al., unpublished data). On the other hand, no proviral LTR as present in 293-PERV-B(33), bearing four 39-bp repeats, has been isolated from the pig genome so far, although PCR experiments in our laboratory have indicated its presence (Fig. 5 and G. Scheef et al., submitted for publication). Due to our approach to search for ORF, other PERV clones, e.g., those containing this LTR, could have been missed during the screening procedure of the PK15 library.

In terms of numbers of functional copies of proviral PERV, it might be speculated that PK15 cells do not harbor many more than two replication-competent PERV-A and two PERV-B sequences, as revealed by isolation of clones 293-PERV-A(42), PK15-PERV-A(58), 293-PERV-B(43), and PK15-PERV-B(213), since 293-PERV-B(33) lacks the env start codon and is thus not functional (5). However, as a 293-PERV-A(42) type of LTR is not present in PK15 cells (Fig. 5) but exists in cells from large white pigs (see above), recombination and adaptation events appear to occur in infected cells.

In conclusion, as it was shown recently for NOD/SCID mice that the transplantation of porcine islets leads to PERV infection (31), the capacity of different proviral PERV to replicate in human cells even at low levels as shown here has a major implication for the use of pig organs and tissues in the course of xenotransplantation. The identification of defined replication-competent retroviruses in the pig genome, however, might help to identify pig breeds which produce lower levels of PERV or are devoid of individual proviruses due to polymorphisms. In general, the number of active PERV is probably dependent on the particular strain of animal. The data presented in this study suggest that the numbers of functional PERV in the pig genome are limited, which would have an impact on the possibility of cloning PERV-free pigs (6).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit), Bonn, Germany.

The technical assistance of Gundula Braun is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Barbara Chmielewicz (Robert-Koch-Institut, Berlin, Germany) for her support in phylogenetic analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyoshi D E, Denaro M, Zhu H, Greenstein J L, Banerjee P T, Fishman J A. Identification of a full-length cDNA for an endogenous retrovirus of miniature swine. J Virol. 1998;72:4503–4507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4503-4507.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan J S. Xenotransplantation at a crossroads: prevention versus progress. Nat Med. 1996;2:18–21. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach F H, Robson S C, Winkler H, Ferran C, Stuhlmeier K M, Wrighton C J, Hancock W W. Barriers to xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 1995;1:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin J. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Hagerstown, Md: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1767–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czauderna F, Fischer N, Boller K, Kurth R, Tönjes R R. Establishment and characterization of molecular clones of porcine endogenous retroviruses replicating on human cells. J Virol. 2000;74:4028–4038. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4028-4038.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorey E. PERV data renew xeno debate. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1032–1033. doi: 10.1038/80207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorling A, Riesbeck K, Warrens A, Lechler R. Clinical xenotransplantation of solid organs. Lancet. 1997;349:867–871. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlers B, Ulrich S, Goltz M. Detection of two novel porcine herpesviruses with high similarity to gammaherpesviruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:971–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fielding A K, Chapel-Fernandes S, Chadwick M P, Bullough F J, Cosset F-L, Russell S J. A hyperfusogenic gibbon ape leukemia envelope glycoprotein: targeting of a cytotoxic gene by ligand display. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:817–826. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishman J A. Miniature swine as organ donors for man: strategies for prevention of xenotransplant-associated infections. Xenotransplantation. 1994;1:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishman J A. Xenosis and xenotransplantation: addressing the infectious risks posed by an emerging technology. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997;51:S41–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green L M, Berg J M. A retroviral Cys-Xaa2-Cys-Xaa4-His-Xaa4-Cys peptide binds metal ions: spectroscopic studies and a proposed three-dimensional structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4047–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krach U, Fischer N, Czauderna F, Kurth R, Tönjes R R. Generation and testing of a highly specific anti-serum directed against porcine endogenous retrovirus nucleocapsid. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:221–229. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeTissier P, Stoye J P, Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Weiss R A. Two sets of human-tropic pig retroviruses. Nature. 1997;389:681–682. doi: 10.1038/39489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin U, Kiessig V, Blusch J H, Haverich A, von der Helm K, Herden T, Steinhoff G. Expression of pig endogenous retrovirus by primary porcine endothelial cells and infection of human cells. Lancet. 1998;352:692–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martiney M J, Rulli K, Beaty R, Levy L S, Lenz J. Selection of reversions and suppressors of mutation in the CBF binding site of a lymphomagenic retrovirus. J Virol. 1999;73:7599–7606. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7599-7606.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meric C, Goff S P. Characterization of Moloney murine leukemia virus mutants with single-amino-acid substitutions in the Cys-His box of the nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1989;63:1558–1568. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1558-1568.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaels M G, Simmons R L. Xenotransplant-associated zoonoses. Transplantation. 1994;57:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oroszlan S, Copeland T D, Gilden R V, Todaro G J. Stuctural homology of the major internal proteins of endogenous type C viruses of two distantly related species of Old World monkeys, Macaca arctoides and Colobos polykomos. Virology. 1981;115:262–271. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradis K, Langford G, Long Z, Heneine W, Sandstrom P, Switzer W M, Chapman L E, Lockey C, Onions D, Otto E. Search for cross-species transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus in patients treated with liver pig tissue. Science. 1999;285:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997;3:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patience C, Switzer W M, Takeuchi Y, Griffiths D J, Goward M E, Heneine W, Stoye J P, Weiss R A. Multiple groups of novel retroviral genomes in pigs and related species. J Virol. 2001;75:2771–2775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2771-2775.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandrini M S, Fodor W L, Mouhtouris E, Osman N, Cohney S, Rollins S A, Guilmette E R, Setter E, Squinto S P, McKenzie I F. Enzymatic remodelling of the carbohydrate surface of a xenogenic cell substantially reduces human antibody binding and complement-mediated cytolysis. Nat Med. 1995;1:1261–1267. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma A, Okabe J, Birch P, McClellan S B, Martin M J, Platt J L, Logan J S. Reduction in the level of Gal(alpha1,3)Gal in transgenic mice and pigs by the expression of an alpha(1,2)fucosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7190–7195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinnick T M, Lerner R A, Sutcliff J G. Nucleotide sequence of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Nature. 1981;293:543–548. doi: 10.1038/293543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoye J P, Coffin J M. The danger of xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 1995;1:1100. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1100a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Magre S, Weiss R A, Banerjee P T, LeTissier P, Stoye J P. Host range and interference studies of three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:9986–9991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9986-9991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tönjes R R, Czauderna F, Fischer N, Krach U, Boller K, Chardon P, Rogel-Gaillard C, Niebert M, Scheef G, Werner A, Kurth R. Molecularly cloned porcine endogenous retroviruses replicate on human cells. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tönjes R R, Czauderna F, Kurth R. Genome-wide screening, cloning, chromosomal assignment, and expression of full-length human endogenous retrovirus type K. J Virol. 1999;73:9187–9195. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9187-9195.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Laan L J W, Lockey C, Griffeth B C, Fraiser F S, Wilson C A, Onions D E, Hering B J, Long Z, Otto E, Torbett B E, Salomon D R. Infection by porcine endogenous retrovirus after islet xenotransplantation in SCID mice. Nature. 2000;407:90–94. doi: 10.1038/35024089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson C A, Wong S, Van Brocklin M, Federspiel M. Extended analysis of the in vitro tropism of porcine endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 2000;74:49–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.49-56.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson C A, Wong S, Muller J, Davidson C E, Rose T M, Burd P. Type C retrovirus released from porcine primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells infects human cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3082–3087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3082-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong Y, Eickbush T H. Origin and evolution of retroelements based upon their reverse transcriptase sequences. EMBO J. 1990;9:3353–3362. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang C, Compans R W. Analysis of the murine leukemia virus R peptide: delineation of the molecular determinants which are important for its fusion inhibition activity. J Virol. 1997;71:8490–8496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8490-8496.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]