Abstract

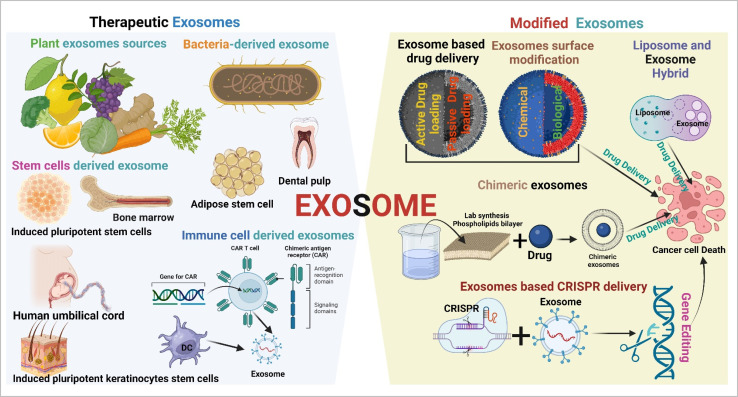

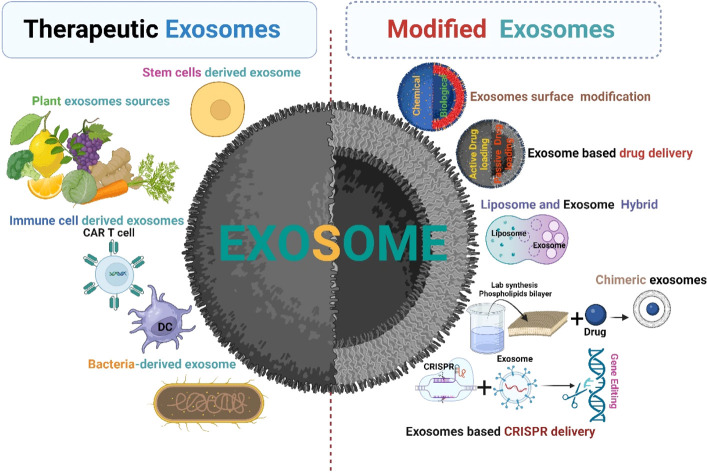

Exosomes are a subpopulation of extracellular vesicles (EVs) that naturally originate from endosomes. They play a significant role in cellular communication. Tumor-secreted exosomes play a crucial role in cancer development and significantly contribute to tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and metastasis by intracellular communication. Tumor-derived exosomes (TEXs) are a promising biomarker source of cancer detection in the early stages. On the other hand, they offer revolutionary cutting-edge approaches to cancer therapeutics. Exosomes offer a cell-free approach to cancer therapeutics, which overcomes immune cell and stem cell therapeutics-based limitations (complication, toxicity, and cost of treatment). There are multiple sources of therapeutic exosomes present (stem cells, immune cells, plant cells, and synthetic and modified exosomes). This article explores the dynamic source of exosomes (plants, mesenchymal stem cells, and immune cells) and their modification (chimeric, hybrid exosomes, exosome-based CRISPR, and drug delivery) based on cancer therapeutic development. This review also highlights exosomes based clinical trials and the challenges and future orientation of exosome research. We hope that this article will inspire researchers to further explore exosome-based cancer therapeutic platforms for precision oncology.

Modified exosomes are a smart tool for the upcoming precision cancer therapeutic era.

1. Introduction

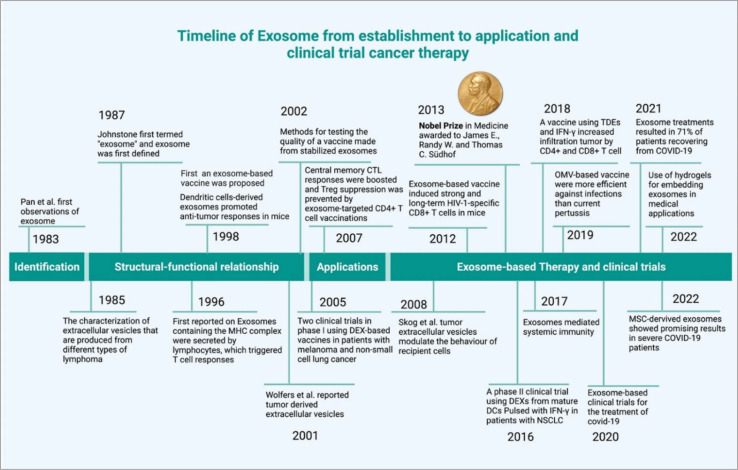

Cancer has became a major global health challenge, causing a significant number of deaths each year.1 Extracellular vesicle (EV)-based cancer investigation has introduced a new dimension to cancer research.2 EVs subpopulation exosomes have played a significant role in cancer development.3 They originate from endosomes.4 Exosomes retain the properties of their source and are unique in their mRNA, proteins, lipids, and miRNA contents.5 The cellular cargoes of exosomes, which include proteins, cell receptors, and miRNAs, can be used to develop cancer biomarkers and thus result in cancer therapy development.6 The DNA present in the exosomes can also be used as biomarkers for detection of cancer.7 Exosomes are a promising tool for anti-cancer drug delivery.8 Therapeutic exosomes can be derived from several sources such as stem cells,9 immune cells,10 and plants.11 Tumor cell-derived (TEXs) exosomes have a dual nature in cancer theranostics applications (due to the enrichment of oncogenic cargos), they are not recommended for therapeutic applications.12,13 TEXs show some cancer-healing properties via tumor growth inhibition.13 Exosomes can be used for anti-cancer vaccine. Another way exosomes can be used as a drug delivery system is because of their non-toxicity, lack of immune reactivity, and stability within biological systems. Electrochemical sensor-based exosomes detection an impressive initiative for early cancer indenfication.14 Modified exosomes are expected to play a role in cancer therapeutic applications. This modification can be a surface modification, chemical modification, genetic modification or synthetic modification.15–17 However, the downside of using exosomes in therapeutic applications is the heterogeneity (this regulated via several factors such as origin, size, and molecular diversity). This problem can be solved using single exosome profiling.18 Single exosome profiling, exosome barcoding and a combination of advanced nanotechnology-based exosome profiling pave the way for us to reach the exosome-based precision oncology era.19 The timeline of exosome-based cancer therapy development summarized in Fig. 1. In this review, we explore the therapeutic applications of exosomes and their modifications based promising clinical outcomes in cancer therapy, clinical trials and future prospects in this field.

Fig. 1. Timeline of exosome-based therapeutics (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 20 Copyright@2022 The Authors).

2. Exosome biogenesis

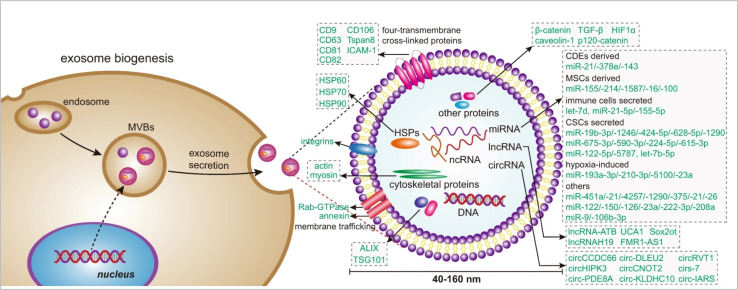

Exosomes are associated with cellular signalling. Exosome biogenesis (Fig. 2) occurs dependently or independently of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT). The ESCRT complexes, which include ESCRT0 to III along with proteins like vacuolar protein sorting 4 (VPS4) are primarily involved in regulating exosome biogenesis. Other ubiquitinated proteins are recognized and sorting is initiated by ESCRT-0,21 while the ESCRT-1 and ESCRT-2 are responsible for the induction of membrane deformation and cargo processing.22 The ESCRT-3 forms spiral-shaped bundles to drive vascular scission and budding with the help of complexes like C-terminal residues of the human CHMP4 proteins (CHMP4).23 The VPS4 recycles the ESCRT-3 after the vascular scission. This synchronous process regulates the intraluminal vesicle formation and hence, facilitates cellular communication. The ESCRT-independent mechanisms provide diverse paths for the formation of exosomes one of which is in the form of lipid components like ceramide and lipid rafts.24 The accumulation of ceramide initiates the budding of exosomes after fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with plasma membrain. In ESCRT independent pathway tetraspanin proteins25 has significal role in exosomes biogensis.26 However, evidence of crosstalk between the two pathways has been observed. For example, the CHMP4C component of the ESCRT-III has interactions with the lipid rafts that are associated with proteins like syntenin.27 Another example is the involvement of syndecan-syntenin-ALIX which is responsible for the release of exosomes and indicates connections between the components of the ESCRT machinery.28 A dysregulation in the ESCRT-dependent or independent pathway can lead to aberrant production of exosomes. This can establish a microenvironment which is pro-tumorigenic.29 Hence, understanding this crosstalk could pave the way for further development of therapeutics which may offer avenues for the modulation of the vesicular cargo.30 During cancer development, exosome secretion depends on the low pH of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and ESCRT-independent pathways.31

Fig. 2. Exosome biogenesis (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 6 Copyright@2020 The Authors).

3. Exosome isolation and characterization

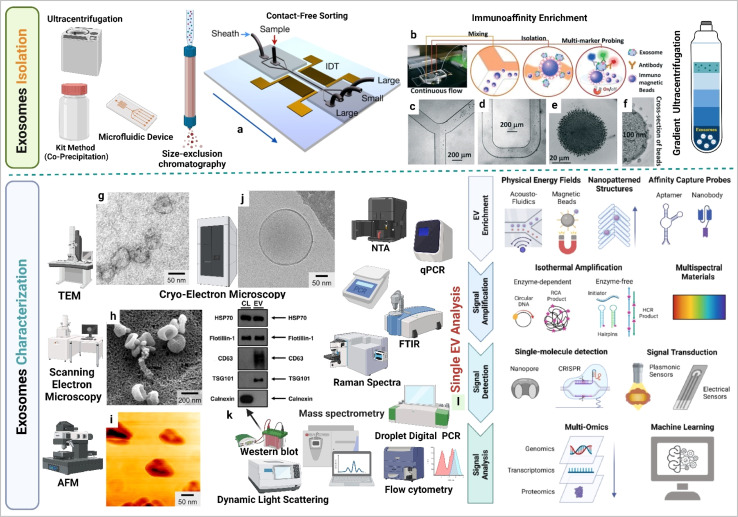

Exosomes can be isolated via several methods such as ultracentrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, and various affinity chromatography techniques which separate them on the basis of size and density.32 While ultracentrifugation is widely used, it is limited by high equipment costs. Dynamic light scattering provides information on the size distribution of exosomes and zeta potential measurements indicate the surface charge of exosomes (in tumor exosomes the surface charge is more negative compared to healthy individual exosomes). Molecular expression of exosomes can be assessed via flow cytometry. Transmission electron microscopy captures exosome images and provides size information, and Raman spectroscopy supports molecular expression analysis in exosomes.33 Challenges related to measuring the size and quantity of the exosome can be addressed using devices based on microfluidics that track exosomes based on antibody fluorescence. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), magnetic and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) principles for individual exosome screening, and advanced and highly sensitive flow cytometry are also utilized for exosomes detaction. Exosome molecular profiling techniques are crucial for unveiling the diverse functional cargo of bioactive molecules within exosomes.34 Exosome RNA profiling has became a prominent area of cancer research.35 The integration of droplet digital polymerase chain reaction microfluidic technology, a chip system, and the electrochemical principle-based microRNA profiling of exosomes offers an innovative perspective towards understanding the cancer complications. Multi-omics approach supports in understanding the molecular diversity of exosomes.36,37 By incorporating machine learning into the single-cell exosome profiling approach, we enhance precision in the development of cancer markers investigation. These technological advancements collectively contribute to the evolution of the next-generation cancer theranostic era, centered around exosomes.37,38 Exosome isolation and characterization are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Exosome isolation and characterization. (a) Contact-free exosome sorting, (b) schematics of a microfluidic chip that enables continuous mixing and isolation of EVs using immunomagnetic beads, microscopy images of the device: (c) Y-shaped injector, (d) serpentine fluidic mixer for immunomagnetic binding, (e) magnetic aggregates, and (f) bound EVs on immunomagnetic beads. (g) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of exosomes, (h) scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of exosomes, (i) atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of exosomes, (j) cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) image of exosomes, (k) western blotting based EVs protein expression analysis (figure (a) to (k) reproduced with permission from ref. 5 Copyright@2018 American Chemical Society), and (l) single EV profiling approaches (reproduced with permission from ref. 39 Copyright@2022 American Chemical Society.).

4. Role of exosomes in cancer

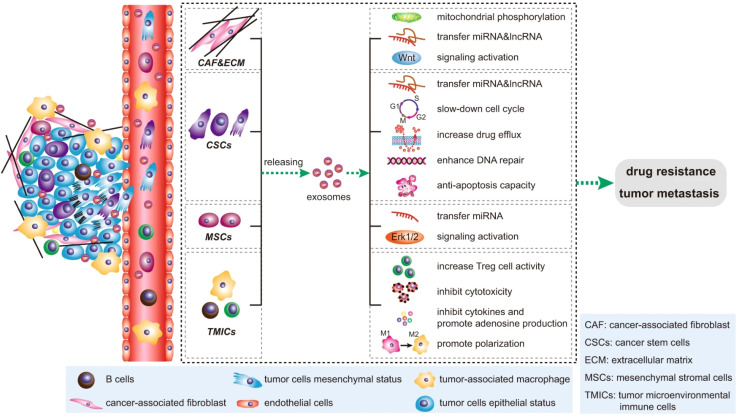

During cancer development, phage exosome-based cell-to-cell communication can reprogram the cell system in different ways. Immune suppression is crucial in cancer development.40 In this event, tumor-derived exosomes (TEXs) mediated miRNA-1 promote M2 polarization in liver cancer.41 This process promotes angiogenesis and myeloid-derived suppressor cells-based immune suppression.42 TEXs based multiple angiogenic factors enhances the angiogenic event in cancer.43 Dendrite cells play a key role in cell-mediated immune response development. TEXs-mediated dendritic (DC) cell signalling during cancer reduces anti-cancer cytotoxicity against tumor cells.44 T cells in the major cell population develop anti-cancer responses in cancer. TEXs medicated PDL1 expression reduce Tell activity against cancer.45 Tumor exosomes develop dysfunctionality in B cells during cancer development.46 TEXs mediate natural killer (NK) cell complex reprogramming in several aspects such as inhibiting NK cell proliferation, reducing cytotoxic effects and downregulation of receptor proteins, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α.47 Tumor-released cells related to ECM and cells become motile and promote EMT.48,49 TEXs are also associated with cancer drug and therapeutic resistance development.49 The tetraspanin protein of TEXs regulates several aspects of cancer development such as immune suppression, angiogenesis, and metastasis.50 Circulating cancer cells migrate to specific organs and develop secondary tumors based on TEXs integrin expression. These phenomena lead to organ-specific metastasis in cancer. The exosome-based cancer development is depicted in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Impact of exosomes in cancer. (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 6 Copyright@2020 Nature publisher).

5. Therapeutic exosomes

Exosomes are cell signalling molecules in the cellular system. Based on their parental cell type, they show promising therapeutic potential against cancer.51 Tumor cell-derived exosomes in general are not used in cancer therapeutic applications due to the enrichment of oncogenic cargos. Several sources of therapeutic exosomes and their modification approaches are described in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Therapeutic exosomes and modified exosomes in cancer therapy (created with https://www.Biorender.com).

5.1. Immune cell-derived exosomes

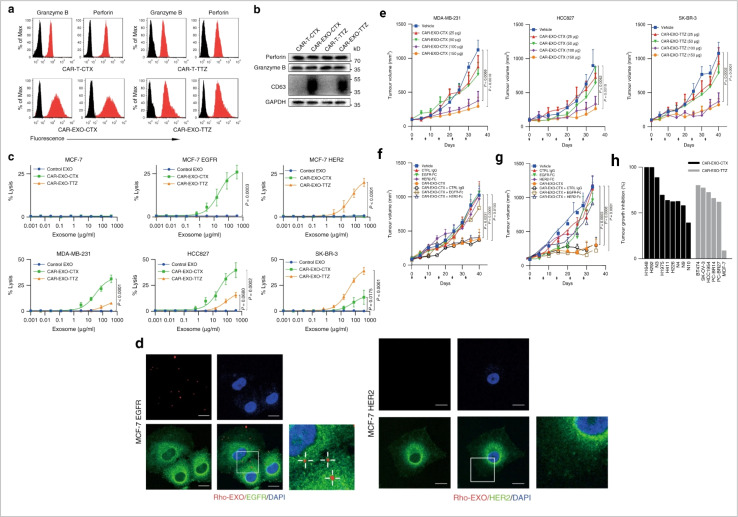

Immune cells are essential for the immune system to protect the human body against disease. However, during cancer, immune cells can be reprogrammed and promote cancer. It is expected that cancer immunotherapy will play a significant role in cancer prevention. Exosome-based immunotherapeutic developments are very impressive. In the immune system, several cells secret exosomes such as T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, NK cells, macrophage cells, mast cells, and neutrophils. Mast cells are part of innate immunity. Mast cell-derived exosomes are related to miRNA and support cellular communication and cell maturation.52–54 These cell population-derived exosomes promote cancer development and enhance EMT events in cancer.55,56 Mast cell device exosomes are also capable of developing an immune response.57 Mast-cell exosome-based cancer therapy requires further research. Natural killer (NK) cells are a major population of cells involved in the immunosurveillance system in the human body and develop an anti-tumor response.58 NK cells release cytotoxic EVs and play a role in the inhibition of tumor growth.59–63 NK cell-derived exosomal miRNA-186 suppresses tumor development.64 The therapeutic potential of NK cell-derived exosomes in cancer treatment is impressive.65 Tumor associated macrophage-derived exosomes promote cancer development.66 In pancreatic cancer, miRNA-510 transported via macrophage exosomes enhances cancer development.67 The most interesting fact about macrophage exosomes is related to drug resistance development.68 In cancer, M2 polarization (a subpopulation of macrophages) promotes angiogenesis and metastasis. One interesting fact is that M1 (a subpopulation of macrophages) derived exosomes show anti-cancer activity.69 Neutrophil-derived exosomes inhibit cancer proliferation and metastasis.70 B-cell-derived exosomes are an unexplored domain of exosome biology. Myeloid suppressor cell-derived exosomal miRNA-126 develop chemoresistance and promote metastasis.71 Dendritic cells (DCs) are a major cell population for antigen presentation in the immune system and activate the T cell-mediated immune response. DCs-derived exosomes have been used in cancer vaccine development.72 T cells are a vital cell population in cell-mediated immunity in humans. T cell-derived exosomes enhance the anti-tumor response via Tc (cytotoxic T cell).73 CAR T cell therapy is a promising approach in cancer therapy. CAR T cell-derived exosomes (cell-free therapy) overcome several limitations of CAR T therapy (toxicity) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Immune cell-derived exosomes in cancer inhibition. Cytolytic activity of CAR exosomes in vitro. (a) Flow cytometry analyses of CAR exosomes linked to latex beads (4 mm diameter) or CAR-T cells stained with the indicated primary Abs. The histograms shown in black correspond to the isotype controls of the respective Abs, whereas the red histograms indicate positive fluorescence. (b) Immunoblots for perforin and granzyme B expression in CAR exosomes and CAR-T cells. (c) Killing activity of CAR exosomes in response to tumor cells. (d) Confocal microscopy analysis of MCF-7 EGFR cells (up) and MCF-7 HER2 cells (down) after incubation with NHS-Rhodamine (Rho)-labelled CAR-EXO-CTX for 2 h, CAR exosomes have notable anti tumor activity in vivo. (e) Tumor volumes of MDA-MB-231 (left), HCC827 (middle) and SK-BR-3 (right) tumor xenografts after treatment with the indicated treatment, (f) and (g) tumor volumes of MDA-MB-231 (b) and SK-BR-3 (c) tumor xenografts after treatment with the indicated CAR exosome treatment with or without blocking recombinant antigen, and (h) cancer cell lines or patient-derived tumour tissue fragments established as subcutaneous xenografts (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 74 Copyright@2019 The Authors).

5.2. Stem cell-derived exosomes

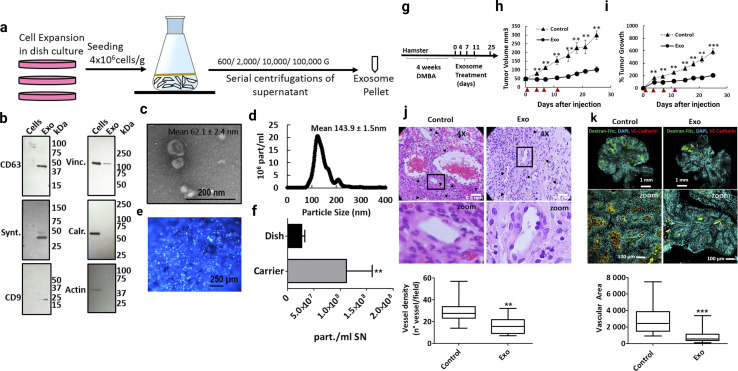

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-Exo) are known for their anti-inflammatory, regenerative, and immunomodulatory properties. MSCs perform tissue healing and immunoregulatory tasks by secreting paracrine substances such as exosomes and MVs.75,76 Stem cell-derived exosomes represent a cell-free approach in cancer therapeutic development (this is more effective compared to stem cell therapy).77 Exosomes derived from umbilical cord MSCs, adipose MSCs also have huge therapeutic benefits, such as tissue regeneration and even tumor progression. The analysis of exosomes from the umbilical cord and MSCs has led to important information, which states that exosomes from these sources have an immunomodulatory effect. Taxol-treated exosomes from MSC544 exhibited cytotoxicity in cancer cells and showed significant tumor growth inhibiting activity.78 Adipose stem cell derived exosome-mediated miRNA-124 exhibited wound healing activity via Wnt signalling pathways.79 Exosomes loaded with paclitaxel that were extracted from prostate cancer showed relatively higher cytotoxic levels than autologous prostate cancer cells.80,81 During cancer development, TME-related MSCs and exosome-mediated cell-to-cell communication develop a complex relationship (cancer-promoting and cancer healing).82 MSCs are used in inflammation-related to colon cancer treatment.83 Inflammation is a key event in tumor development.84 Escaping immune surveillance promotes cancer development.85 In cancer, TME-related MSCs promote cancer stem cell development.86 MSCs derived exosomes miRNA-16 suppress angiogenesis via down relation of VEGF.87 In the in vitro model, MSCs-mediated miRNA100 transport inhibits the angiogenesis of breast cancer.88 Bone marrow MSCs-derived exosomes miRNA-23 promote breast cancer.89 In prostate cancer, exosomes from MSCs carrying miR-145 suppress cancer cell proliferation and enhance apoptosis.90 Bone marrow MSCs-derived exosomes reduce lung cancer metastasis.91 Research into MSCs exosomes indicates that modified stem cell-derived exosomes are more promising for cancer therapeutic development.92 Stem cell exosome-based cancer healing is depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer therapy. (a) Schematic overview of the exosome production process, (b) western blot of cell lysate (cells) and exosomes (exo). To confirm the purity of the exosomes, positive exosomal markers CD63, syntenin and CD9 and negative exosomal markers vinculin (Vinc.) and calreticulin (Calr.) and β-Actin (actin) were analyzed, (c) scanning electron micrograph of purified exosomes, and (d) size distribution of exosomes determined by insights showing that the highest abundance of particles was below 200 nm. (e) Hoechst-stained MenSC on BioNOC II carrier, showing a typical confluence for exosome production. (f) Yield of purified exosomes in PBS as particles (part) per mL of initial cell culture supernatant. Tumor growth and angiogenesis is significantly reduced by exosome treatment. (g) Scheme of experimental design. Tumors were induced with four weeks of DMBA treatment and four injections of exosomes were administered every 3–4 days, (h) and (i). Tumor growth in mm3 tumor volume and relative tumor growth indicating days of exosome treatment. Control tumors are shown as triangles and exosome treated tumors as circles. (j) Histological sections of tumors at day 25 (end-point) with Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E), and (k) Dextran-Fitc (green), VE Cadherin (red) and Hoechst (blue) stained histological sections of tumors at day 25 (end-point) (Reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 93 Copyright@2019 The Authors).

5.3. Plant-derived exosomes

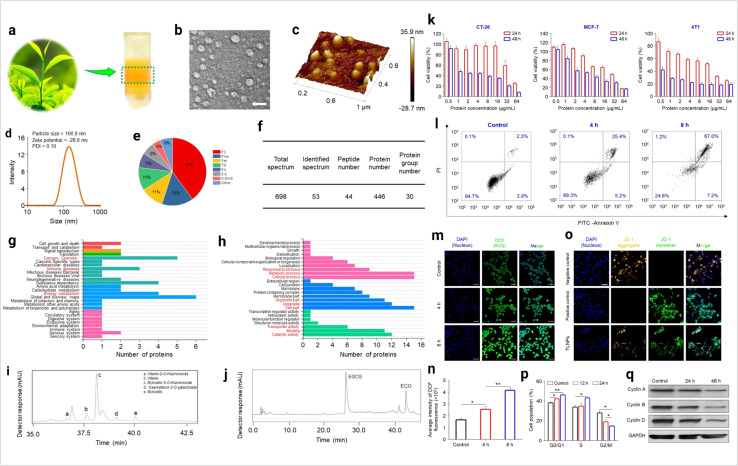

Plant-derived exosomes are a natural source of exosomes. Multiple fruits, vegetables, and several parts of plants are the source of plant exosomes. Plant-derived exosomes (PDExo) carry large amounts of anti-oxidant, anti-inflammation, and anti-tumor regulatory molecules.94 In cancer, CRISPR-based gene editing shows a significant outcome. PDExo-based CRISPR transport develops an impressive cancer therapeutic approach.95 PDExo-based drug delivery for targeting cancer cells is very impactful.96 Toxicological expect PDExo is better compared to stem cells and immune cells-derived exosomes.96 Black grape derived exosome-based oral cancer therapeutics are showing effective results in a clinical trial.97 PDExo metabolites have a significant role in anti-cancer activity.98 Ginseng-derived EVs promote M1 polarization-based anti-cancer activity.99Dendropanax morbifera and Pinus densiflora plant extract-derived EVs show effective anti-cancer potential against breast cancer.100 Citrus limon-derived exosomes inhibit tumor cell growth via activation of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor.101 PDExo-mediated miRNA17 transport shows effective anti-brain cancer activity in mice models.102 Plant exosome-based hybrid exosome development becomes a smart approach for therapeutic development.96 Some of the questions are still unsolved such as the environmental impact on PDExo and PDExo phytochemical cargos working principle. Ongoing clinical trials determine the future clinical therapeutic applications of plant-derived exosomes. The plant exosome-based anti-cancer activity is depicted in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Plant-derived exosomes in cancer inhibition. (a) Plant exosomes in the sucrose gradients after ultracentrifugation, (b) TEM imaging (scale bar: 100 nm), (c) AFM imaging, (d) hydrodynamic particle size distribution, (e) lipid compositions, (f) protein summary, (g) KEGG annotated statistical charts, (h) Go secondary classification statistical charts of plant exosomes, (i) flavonoids, and (j) polyphenols in plant exosomes. In vitro anti-tumor effects of plant exosomes, (k) cytotoxicity of plant exosomes against various tumor cell lines after co-incubation with plant exosomes, (l) pro-apoptotic properties of TLNTs after co-incubation with plant exosomes, (m) CLSM images of 4T1 cells stained with DCFH-DA after co-incubation with plant exosomes for 4 and 8 h, (n) ROS fluorescence intensity of 4T1 cells after co-incubation with plant exosomes for 4 and 8 h, respectively. (o) Mitochondrial membrane potential changes in 4T1 cells (scale bar: 50 μm), (p) TLNTs restrained cell cycle progression in 4T1 cells after co-incubation with plant exosomes for 12 and 24 h, respectively, (q) western blot analysis of 4T1 cells receiving the treatment of plant exosomes for 48 h. Cyclin A, cyclin B and cyclin D proteins were probed. GAPDH was probed to ensure the equal loading of total proteins in each lane (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 103 Copyright@2023 The Authors).

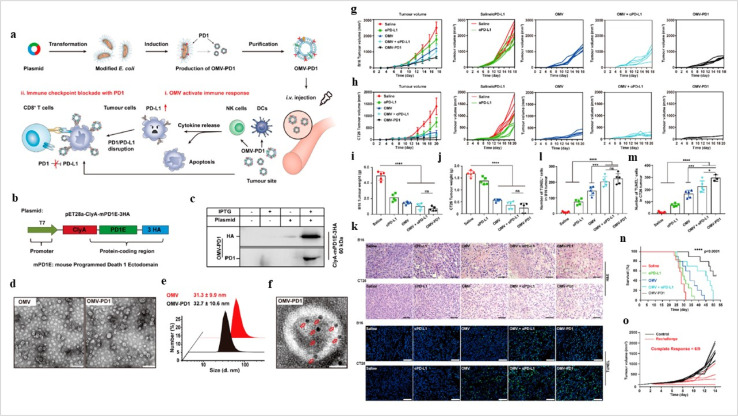

5.4. Bacteria-derived exosomes

Bacteria-derived exosomes (Fig. 9) are a new chapter in cancer therapeutic development. The high-purity cellulose-based BC + Exos membrane displayed a three-dimensional interconnected structure and exhibited acceptable mechanical characteristics. Degeneration was not observed. The BC + Exos membrane demonstrated biocompatibility in vivo and no cytotoxicity. Both peridural adhesions and epidural fibrosis might be prevented by the BC + Exos film. According to the latest research, post-operative epidural fibrosis and adhesion can be avoided by using the BC + Exos membrane.105

Fig. 9. Bacteria-derived exosomes in cancer inhibition. (a) Outer membrane vesicles (OMV) OMV-PD1 were obtained by engineering E. coli to stably express the mouse PD1 ectodomain fused with the surface protein ClyA and then purifying the vesicles from the parent bacteria by ultracentrifugation. OMV-PD1 accumulation at the tumor site increases the infiltration of immune cells, such as DCs and NK cells, and activates an immune response in vivo. At the same time, the PD1 ectodomain on the OMV-PD1 surface blocks the PD1/PD-L1 interaction and protects CD8+ T cells, which can then attack tumor cells. (b) A schematic illustration of the construct used to express ClyA-mPD1E-3HA, (c) western blot analysis of the expression of ClyA-mPD1E-3HA on the OMV, detected using an anti-HA and an anti-PD1 antibody, (d) and TEM images of OMV and OMV-PD1. Scale bar = 100 nm. (e) The size distribution of OMV and OMV-PD1 was measured by DLS. (f) Representative TEM image of OMV-PD1 immunostained with an anti-HA primary antibody and then with an immunogold-labeled secondary antibody. Red arrowheads indicate 5 nm gold particles. Scale bar 25 nm. Antitumor effects of OMV-PD1 in vivo. (g and h) Growth curves of subcutaneously implanted B16 tumors (g) and CT26 tumors (h) following treatment with saline, αPD-L1, OMV, OMV + αPD-L1, or OMV-PD1, (i and j) the final weight of excised B16 tumors (i) and CT26 tumors (j) from mice in each group at the end of the treatment, (k) representative H&E (upper) and fluorescent TUNEL (bottom; indicates apoptotic cells) stained sections of B16 and CT26 tumor tissue at the end of the experiments. (l and m) Statistical analysis of the number of TUNEL+ cells per field for B16 (l) and CT26 (m) tumor. (n) Survival curves of CT26 tumor-bearing mice treated with different formulations, and (o) tumor volumes of subcutaneous re-challenge with CT26 tumor cells at day 55 in OMV-PD1-cured CT26 tumor-bearing mice (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 104 Copyright @2020The Authors).

6. Exosomes in drug delivery

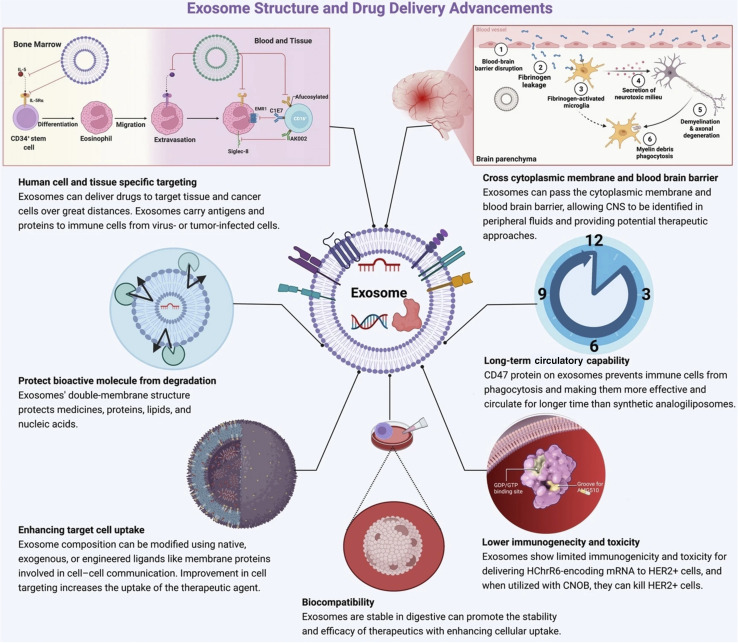

EVs are lipid-bound vesicles that originate from cells and play diverse roles in regulating biological processes.102 Exosomes, a subtype of EVs, originate from endosomes. It is an efficient cellular transporter in the cellular system for the genetic material of drug delivery.106 Exosome loading approaches are classified into major groups such as active and passive methods.107 In breast cancer, exosome-based drug delivery shows promising results in an in vitro and in vivo model.108 Exosome-based cancer-specific antigen delivery promotes a strong immune response against cancer.109 Exosome-based drug delivery comes with several advantages (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Advantages of exosome-based drug delivery (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 20 Copyright 2022 The Authors).

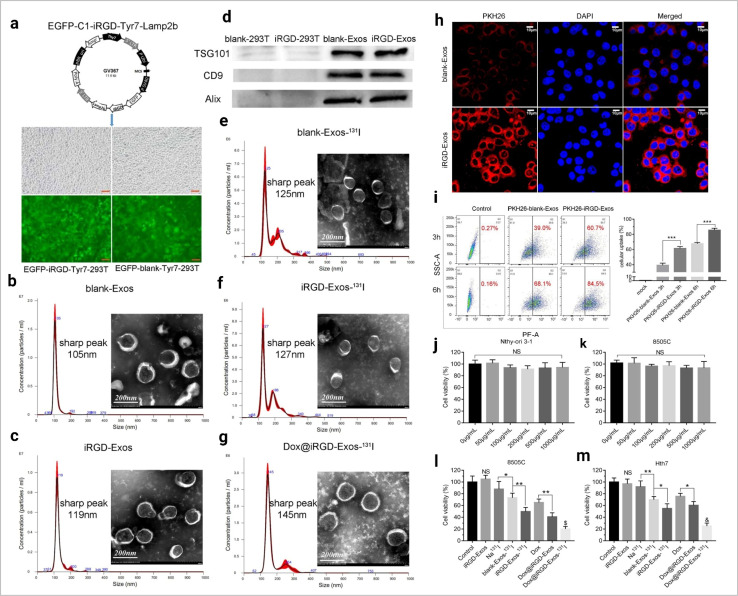

Exosomes loaded with herbal drugs have potential anticancer activity against ovarian cancer in both in vitro and in vivo models.110 Tumor-derived exosome-based chemotherapeutic (DOX) drug delivery has shown effective anti-cancer activity.111 The tripartite motif 3 (TRIM3) protein found in the serum of the gastric cancer exosome is a potential biomarker and acts as a therapeutic agent for cancer treatment.112 Lung cancer antigen-loaded dendritic cell (DC) derived exosome-based vaccines have shown stability in treatment in clinical trials (phase I).113 Exosome-based drug delivery to the brain is very effective.114 In ovarian cancer, exosome-mediated miRNA-99 developed an aggressive tumor population.115 Exosomes and magnetic nanoparticle-based modified exosome-based DOX delivery show promising antitumor activity.116 RBC-derived EVs are a promising RNA drug transporter.117 This approach also shows effectiveness in cancer therapy. Phosphatidylcholine-based exosome engineering enhances better exosome uptake efficiency in tumor cells.118 Dendritic cell-derived exosomes are the most successful cell-free cancer immunotherapeutic approach.119 Still, this approach required more research for better immune response development. This domain carries the hope of future cancer vaccine-developed efficiency.120 Anti-CTLA-4 functionalized DC cell-derived exosomes promote T cell-mediated anti-tumor response in cancer.121 The exosome-based drug delivery approach is depicted in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11. Exosome-based drug delivery. (a) The main composition of the EGFP-C1-iRGD-Tyr7-Lamp2b plasmid and an image of iRGD/blank-Tyr7-EGFP-293T cells using fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 100 μm). Representative TEM images and particle size distribution of (b) blank-Exos, (c) iRGD-Exos, (d) western blotting analysis of exosome marker proteins (TSG101, CD9 and Alix) of blank-Exos and iRGD-Exos, (e) blank-Exos-131I, (f) iRGD-Exos-131I and (g) Dox@iRGD-Exos-131I, in vitro targeting of iRGD-Exos. (h) Confocal microscopy images of 8505C cells incubated with PKH26-blank-Exos and PKH26-iRGD-Exos at 4 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Fluorescence from PKH26 (red) and DAPI (blue) was observed. The scale bar is 10 μm. (i) Flow cytometric analysis of PKH26-iRGD-Exos binding to 8505C cells. Exosomes were labelled with PKH26 and incubated with 8505C for different lengths of time, viability of (j) Nthy-ori 3-1 and (k) 8505C cells treated with different concentrations of iRGD-Exos, (l) 8505C and (m) Hth7 cells were incubated with control medium, iRGD-Exos, Na131I, blank-Exos-131I, iRGD-Exos-131I, Dox, Dox@ iRGD-Exos, or Dox@iRGD-Exos-131I. A CCK-8 assay was used to assess cell viability in each group (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 122 Copyright @ 2022 The Authors).

7. Modified exosomes in cancer therapy

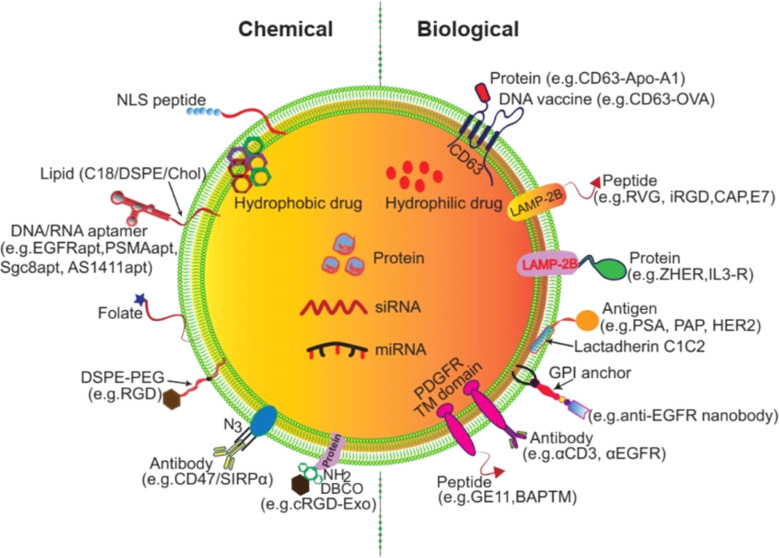

7.1. Exosome surface modification

Modified surface-engineered EVs provide enhanced specificity with low immunogenic and toxicity for drug transport in target cells.123,124 Exosome release and uptake are influenced by pH.125 Research evidence suggests that tumor derived exosomes (TEXs) carry a high negative charge on their surface. Surface modification of EVs holds great promise for clinical applications.126 DNA aptamer-based exosome surface modification is an effective clinical theranostic approach.127 Click chemistry offers a promising exosome surface functionalization method.128 In this process, the alkaline group is used and is not affected by surface charge and size of the exosome. The fusion of click chemistry and exosomes opens new possibilities to versatile biomedical applications of exosomes.128 Exosome surface modification can be conducted via aptamers and gold nanoparticles to promote cancer cell apoptosis.129 In in vitro imaging and specific drug transportation exosome surface modification shows a promising impact.130 Engineered exosome-based miRNA transport provides a potential cancer therapeutic tool.131 Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and programmed cell death ligand-based exosome modification develops a T cell-mediated anti-cancer response.131 Biological and chemical surface modification approaches for exosomes are described in Fig. 12.132

Fig. 12. Exosome surface modification (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 123 Copyright @ 2021 The Authors).

7.2. Chimeric exosomes in cancer therapy

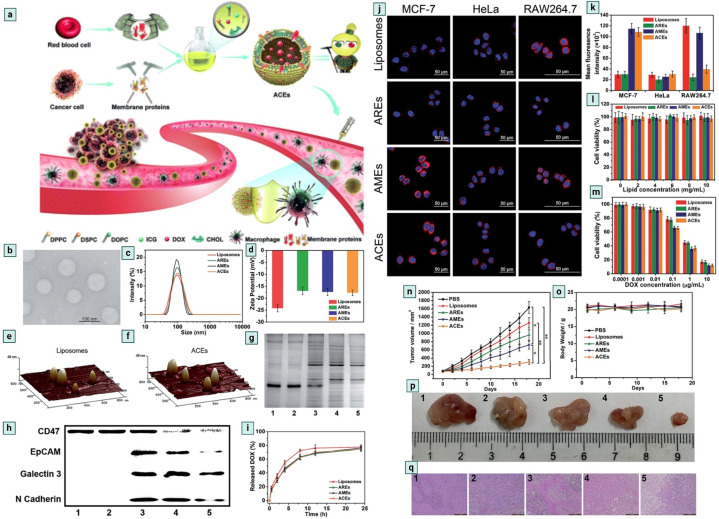

Exosome modification is essential for enhancing specificity, biocompatibility, stability, and efficiency.133 Modified exosomes are a smart platform which offer a promising approach for exosome-based cancer immunotherapy.134 CD47 is an interesting protein that inhibits the accumulation of exosomes on the tumor side, CD47 knockdown cell-derived exosomes show promising therapeutic activity against cancer.135 CD47 is found on the surface of RBC and it plays a crucial role in anti-phagocytic response development.136,137 Exosomes serve as messengers in the cellular system,138 and are effective drug delivery tools,139 but for large-scale production purposes, scientists have developed the Artificial Chimeric Exosomes (ACEs) concept.140,141 Zhang et al.16 developed an innovative approach by isolating CD47 proteins from the RBC surface and fusing them with a laboratory synthesised phospholipid bilayer membrane to develop chimeric exosomes. ACEs-based DOX (doxorubicin) drug delivery shows effective anti-cancer activity (Fig. 13.).16,142,143 ACEs show promising anticancer activity in in vitro and in vivo models.

Fig. 13. Chimeric exosomes in tumor inhibition. (a) A schematic illustration of the design of biomimetic ACEs for anti-phagocytosis and targeted cancer therapy. (b) TEM images of ACEs, (c) hydrodynamic diameter and, (d) zeta potential of liposomes, AREs, AMEs and ACEs. AFM images of (e) liposomes and (f) ACEs reveal the presence of hinged structures on the surface of ACEs. (g) Protein content visualization of (1) RBCs, (2) AREs, (3) ACEs, (4) AMEs and (5) MCF-7 cells. (h) Membrane protein characterization by western blotting analysis of (1) RBCs, (2) AREs, (3) ACEs, (4) AMEs and (5) MCF-7 cells. (i) In vitro DOX release behaviour at 37 °C, intracellular uptake and cytotoxicity of ACEs. (j) In vitro DOX fluorescence imaging of ACEs in MCF-7 cells, HeLa cells, and RAW264.7 cells after 2 h incubation. The nucleus was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). The vesicles were loaded with DOX (red), (k) semiquantitative intracellular uptake of ACEs determined by the averaged DOX fluorescence intensity of each cell, in vitro cytotoxicity of different nanovesicles (l) without DOX and (m) with various concentrations of DOX after 24 h incubation with MCF-7 cells. In vivo antitumor efficacy of ACEs to tumor-bearing nude mice. (n) Tumor growth curves of different groups after treatments. (o) Changes of body weight with increasing time. (p) Representative tumor photos and (q) H&E stained tumor sections from tumor-bearing mice after treatment with (1) PBS, (2) liposomes, (3) AREs, (4) AMEs and (5) ACEs (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 16 Copyright @ 2018 The Authors).

7.3. Exosome-based CRISPR delivery

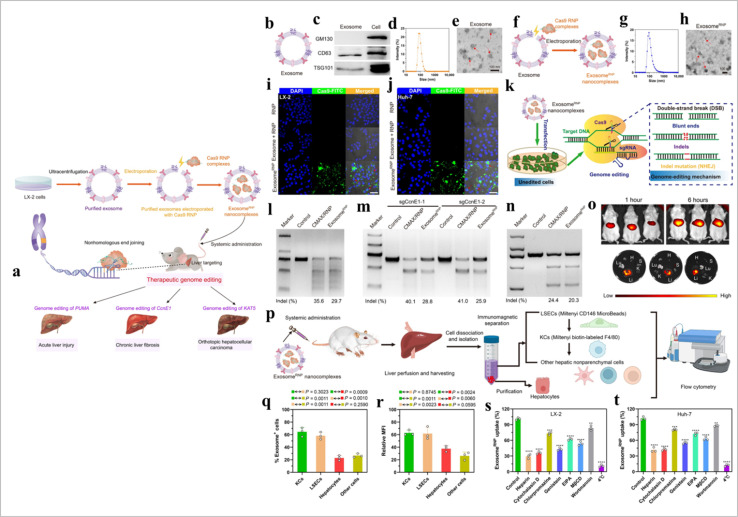

CRISPR/Cas9 is a promising gene editing tool.144 This method has some limitations such as developing potential mutations,145 non-specificity, and immunogenicity.146 EVs-based CRISPR/Cas9 transport gives effective outcomes in in vitro and in vivo models.146 The cell-free loading method (EVs loading) effectively delivers drugs and CRISPR/Cas9 in the targeted cells.147 The electroporation method used RNA molecules loading in EVs.148 CRISPR/Cas9 loaded in EVs via the incubation method.146 Cancer cell-derived exosome-based CRISPR/Cas9 delivery promotes cancer cell apoptosis.149 However, caution should be exercised when using cancer-derived EVs as they may contain various molecules that could promote tumor growth and metastasis. Compared to tumor exosomes, epithelial exosomes-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery is safer and more effective.150 EVs-based CRISPR/Cas9 transport has shown promising outcomes in liver disease.151 CAR EVs and CRISPR/Cas9 combination has shown significant effects against B cell malignancy.152 Exosome based CRISPR delivery is described in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14. Exosome-based CRISPR transport. (a) A schematic illustration of exosome for in vivo delivery of Cas9 RNP for the treatment of liver disorders, (b) and exosomeRNP complexes (c), (d) biomarkers of exosome by western blotting. (e and f) DLS and TEM images of purified exosome. The arrows show the typical exosome nanoparticles. (f and G) DLS and TEM images of exosomeRNP complexes. The arrows show the typical exosomeRNP nanoparticles. (h and i) Cytosolic delivery of Cas9-FITC into LX-2 (h) and Huh-7 (i) cells by exosomes for 4 hours. The red arrows point at the efficient translocation of RNP into the nuclei. Scale bars, 25 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (j) Exosome-mediated Cas9 RNP delivery for genome editing. (k) Frequency of PUMA indel mutation detected by T7E1 assay from AML-12 cells after the specified treatments. (l) Frequency of CcnE1 indel mutation detected by T7E1 assay from AML-12 cells after the specified treatments. (m) Frequency of KAT5 indel mutation detected by T7E1 assay from LX-2 cells after the specified treatments. (n) In vivo distribution of DiR-labeled exosomes in whole mice (top) or in the organs of the mice (bottom). H, heart; Lu, lung; Li, liver; K, kidney; and S, spleen. (o) A schematic illustrating the procedure to isolate different hepatic cell types and determine exosomeRNP biodistribution. (p) Percentage of each hepatic cell type that is DiI-labeled exosomeRNP-positive. (q) Relative MFI of each hepatic cell type. (r and s) Mechanism of cellular uptake of exosomeRNP nanocomplexes in LX-2 (r) and Huh-7 (s) cells by the addition of different inhibitors (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 151 Copyright @ 2022 The Authors).

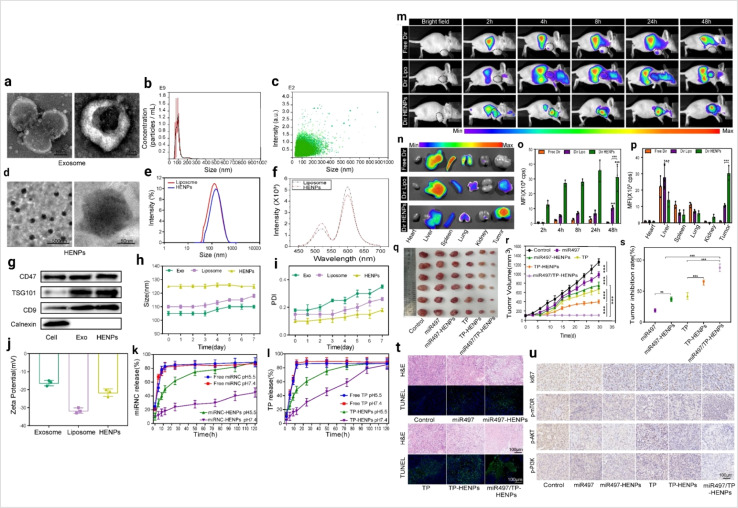

7.4. Exosomes and liposome hybrid

In cancer therapy, liposomes are a promising drug delivery tool.153 The exosome and liposome hybrid concept arises from the need for more specific cancer targeting. Exosome and liposome hybrids develop effective cellular transport which carries some impressive features such as low toxicity, biocompatibility, lower immunogenic, more stability and the capability to cross the biological barrier.154 This hybrid approach supports the controlled release of drugs.155 Liposome hybrid based cancer therapy is described in Fig. 15.

Fig. 15. Liposome hybrid in cancer therapy (a) representative image of exosomes captured by TEM at different magnifications. (b) The size distribution of exosomes and (c) the particle size distribution range of exosomes as measured by NTA. (d) The morphology of HENPs detected by TEM. (e) Size distribution of liposomes and HENPs. (f) The FRET assay showed the successful fusion of exosomes and liposomes. (g) Protein expression of exosomes and HENPs nanovesicles. (h and i) The nanoparticle size and PDI over time, used to assess the stability of the nanoparticles. (j) Zeta potential distribution of exosomes, liposomes and HENPs. (k and l) Release profiles of miRNC and TP at pH values of 5.5 and 7.4 at 37 °C. The targeting and antitumor activity of miR497/TP-HENPs in vivo. (m) In vivo imaging to observe the tumor targeting ability of different nanoparticles. (n) Ex vivo fluorescence images of the main organs and tumors isolated from mice bearing subcutaneous SKOV3-CDDP tumors. (o) Quantitative analysis of Dir distribution in the tumor site postinjection elevated by the fluorescence intensity measured in (m). (p) Quantitative assessment of the mean fluorescence intensity in major organs and isolated subcutaneous tumors. (q) Representative photographs of subcutaneous tumors harvested from all treatment groups. (r) Growth record curves of subcutaneous tumors in nude mice during the experiment. (s) The inhibition rate of OC treated with various drugs. (t) The H&E staining and TUNEL staining. (u) Immunohistochemical detection of ki67, p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR (reproduced with permission under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license from ref. 156 Copyright @ 2022The Authors).

8. Clinical trials

Several exosome-based clinical trials are ongoing worldwide. Based on this review article theme, we have listed only therapeutic exosome trials (Table 1).

Clinical trials of therapeutic exosomesa.

| Clinical trial ID | Status | Cancer | Exosomes source | Clinically significant | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01294072 | Recruiting | Colon cancer | Plant exosomes | Phase I clinical trial investigating the ability of plant exosomes to deliver curcumin to normal and malignant colon tissue | University of Louisville |

| NCT03608631 | Active, not recruiting | Metastatic pancreas cancer | Mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes (with KrasG12D) | Phase I study of mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes with KrasG12D siRNA for metastatic pancreas cancer patients harboring KrasG12D mutation | M.D. Anderson cancer center |

| NCT01159288 | Completed | Unresectable non small cell lung Cancer | Vaccination with tumor antigen-loaded dendritic cell-derived exosomes | Phase II trial of a vaccination with tumor antigen-loaded dendritic cell-derived exosomes on patients with unresectable non small cell lung cancer responding to induction chemotherapy | Gustave roussy, cancer campus, Grand Paris |

| NCT06245746 | Not yet recruiting | Acute myeloid leukemia (after achieving complete remission) | Umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells exosomes (UCMSC-Exo) | A single-center, prospective trial of the safety and efficacy of UCMSC-Exo in consolidation chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression in patients with acute myeloid leukemia after achieving complete remission | Wuhan Union Hospital, China |

| NCT01668849 | Completed | Oral mucositis associated with chemoradiation treatment of head and neck cancer | Edible plant (grape) exosome | Preliminary clinical trial investigating the ability of plant exosomes to abrogate oral mucositis induced by combined chemotherapy and radiation in head and neck Cancer patients | University of Louisville |

Source: https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

9. Challenges and future prospects of exosomes in cancer research

The intricate nature of exosomes presents opportunities for the development of clinical-grade products, yet their diverse subgroups require comprehensive studies for their characterization and definition as biomarkers. Standardizing the analysis and manufacturing of exosomes for clinical use remains a challenge due to the unresolved irregularities in isolation methods and experimental procedures. In spite of their potential in regenerative medicine, challenges persist for exosomes, particularly concerning their informative value, which pivots around their concentration. While methods like ultracentrifugation and tangential flow filtration can successfully be used, their appropriate accuracy requires supplementation with methods like immunocapture and density gradient centrifugation.157 Enriched clinical protocols are essential for phase II trials to evaluate exosomes' efficacy on a larger scale. Diverse standards across industries for exosomes products highlight the significance of purification methods, which impact miRNA and the composition of their surface proteins. Exosomes' heterogeneity is regulated with the help of molecular variation, dynamic origin, and size.39 To resolve problems associated with heterogeneity,39 used a microfluid158 based platform for proper exosomes isolation. Single exosome profiling and exosome barcoding uncover the overall diversity of exosomes. Single exosome assays, pertaining to point-of-care testing principles, offer a high performance with simplicity and make it easy for clinical adoption and commercialization on multiple platforms.159 Exosomes carry diverse molecular cargo as a reflection of their parental cell properties. However, understanding their effects and mechanisms of their action remains challenging. The applicable and accurate delivery of exosomes as therapeutics is obstructed by their short half-life, poor zeta potential, and uncertain optimal doses.160 Hence, comparing exosome types, properties and cargo for therapeutic effectiveness is necessary for forthcoming applications.161

10. Conclusions

In summary, the study of exosome-based therapeutics offers significant promise for medical interventions. Exosomes, with their unique biological properties, have versatile functions across various medical fields. Their flexibility holds potential for groundbreaking advancements in cancer therapy and multiple medical domains. Exosomes show immense potential in targeted cancer interventions by delivering therapeutic cargo directly to cancer cells. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes, known for their regenerative properties, also have immunomodulatory effects and can be tailored for cancer therapy. However, several challenges need to be addressed to fully realize the potential of exosome-based therapies. These include the standardization of isolation techniques and heterogeneity in source, size, and molecular diversity. However, these issues can be addressed through single exosome profiling, exosome barcoding, and advanced nanotechnology, which enable progress toward precision oncology. Additionally, concerns regarding immunogenicity and ethical considerations about the use of exosomes need to be addressed after careful consideration. To resolve challenges like these, ongoing research activities focus on refining isolation methodologies, enhancing scalability, and developing standardized protocols. Enhancements in engineering exosomes to optimize their therapeutic cargo and improve targeting specificity also represent assuring opportunities. The therapeutic potential of exosomes derived from various sources like plant cells, mesenchymal stem cells, immune cells and other cells addresses numerous challenges in cancer therapy like toxicity and immunogenicity etc. Hybrid exosomes offer effective cellular transport with advantages such as low toxicity, high biocompatibility, reduced immunogenicity, increased stability, and the ability to cross biological barriers, opening new possibilities in precision cancer medicine. The collective efforts of researchers, clinicians, and stakeholders are crucial for establishing guidelines and forming ethical frameworks to ensure the responsible integration of exosome-based therapies into clinical practice. As the field progresses, it is crucial to adopt interdisciplinary collaborations, and capitalize technological innovations. The collaborative commitment to overcome these challenges will make way for exosomes as versatile and promising therapeutics in the field of medicine. In this process, exosomes will revolutionize the way we approach disease treatment and personalized medicine.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author K. A. acknowledges the University of the Free State (UFS) and the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa for the NRF-Support for Y-rated Researchers [Grant No. CSRP22031632].

Biographies

Biography

Divya Mirgh.

Ms Divya Mirgh is a research assistant at the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Centre, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA, and has a significant publication track record in the field of exosomes and cancer. Her research interests are cancer, immunotherapy, bioinformatics, exosomes, and image mass cytometry.

Biography

Swarup Sonar.

Mr Swarup Sonar is a distinguished member of the Indian Extracellular Vesicles Society (IEVS) and the International Society of Liquid Biopsy (ISLB). He is involved in research activities with the Center for Global Health Research at Saveetha Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. His research interests include exosome-based cancer medicine, biomarkers for early diagnosis and prognosis of cancer, extracellular vesicle-based liquid biopsy, and the targeted application of nano-medicine in cancer research. He has published several articles in these domains.

Biography

Srestha Ghosh.

Ms Srestha Ghosh completed her undergraduate and postgraduate studies in microbiology at the University of Calcutta, focusing on exosome-related cancer therapies. Eager to explore this dynamic field further, she soon joins West Virginia University, USA, as a PhD student. Her research will concentrate on advancing our understanding of biological elements in regeneration biology.

Biography

Manab Deb Adhikari.

Dr Manab Deb Adhikari is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biotechnology at the University of North Bengal, India. He holds a PhD from IIT Guwahati and has over 15 years of experience in Nanobiotechnology and interdisciplinary research. His interests include diagnostics, exosomes, therapeutics, and drug delivery, with publications in leading journals and contributions to multiple books. He has also served as a peer reviewer for several scientific journals and is a member of the Society for Biotechnologists (India) and the Association of Microbiologists of India.

Biography

Vetriselvan Subramaniyan.

Professor Vetriselvan Subramaniyan, a distinguished academic with over fifteen years of experience, graduated from Annamalai University and has worked at prestigious institutions worldwide, including Arba Minch University and MAHSA University. Currently, he holds a professor position at Sunway University. He has filed eight patents internationally, published over 180 papers with a cumulative impact factor exceeding 500, and received numerous grants from organizations like the Ministry of Higher Education, in Malaysia. His professional affiliations include membership in several renowned scientific societies and editorial boards.

Biography

Sukhamoy Gorai.

Dr Sukhamoy Gorai is a postdoctoral researcher (Neurosciences) at the Rush University Medical Centre. His expertise is in small molecules, molecular biology, protein purification, docking and exosomes. He has a significant publication track record in the field of exosomes and cancer.

Biography

Krishnan Anand.

Dr Krishnan Anand is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State and a National Research Foundation (NRF) – rated scientist who was included in Stanford University's global top 2% list of leading researchers in applied biochemistry. He leads the Precision Medicine and Integrated Nano Diagnostics (P-MIND) research group, which is currently engaged in the biological functions of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in cellular studies conducted under supraphysiological conditions, biomarker discovery through EVs derived from liquid biopsies and the role of circulating biomarkers in disease development.

References

- Siegel R. L. Miller K. D. Wagle N. S. Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. H. Cerione R. A. Antonyak M. A. Extracellular vesicles and their roles in cancer progression. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021;2174:143–170. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0759-6_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Y. L. Chen K. C. Hsieh J. T. Shen T. L. Exosomes in cancer development and clinical applications. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(8):2364–2374. doi: 10.1111/cas.13697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Liu Y. Liu H. Tang W. H. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H. Im H. Castro C. M. Breakefield X. Weissleder R. Lee H. New technologies for analysis of extracellular vesicles. Chem. Rev. 2018;118(4):1917–1950. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J. Su Y. Zhong S. Cong L. Liu B. Yang J. Tao Y. He Z. Chen C. Jiang Y. Exosomes: key players in cancer and potential therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2020;5(1):145. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya B. Dhar R. Mukherjee S. Gorai S. Devi A. Krishnan A. Alexiou A. Papadakis M. Exosome DNA: An untold story of cancer. Clin. Transl. Discovery. 2023;3(4):e218. [Google Scholar]

- Moon B. Chang S. Exosome as a Delivery Vehicle for Cancer Therapy. Cells. 2022;11(3):316. doi: 10.3390/cells11030316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A. Dhar R. Devi A. Stem cell-derived exosomes: An advanced horizon to cancer regenerative medicine. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024;7(4):2128–2139. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.4c00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. Zeng S. Gong Z. Yan Y. Exosome-based immunotherapy: a promising approach for cancer treatment. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhan S. Dhar R. Devi A. Plant-derived exosomes: a green approach for cancer drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2024;12(9):2236–2252. doi: 10.1039/d3tb02752j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. Luo J. D. Jiang H. Duan D. D. Tumor exosomes: a double-edged sword in cancer therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018;39(4):534–541. doi: 10.1038/aps.2018.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei R. Baghaei K. Hashemi S. M. Zali M. R. Ghanbarian H. Amani D. Tumor-derived exosomes Enriched by miRNA-124 promote Anti-tumor Immune response in CT-26 tumor-bearing mice. Front. Med. 2021;8:619939. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.619939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. Ma Q. Electrochemical nano-sensing interface for exosomes analysis and cancer diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022;214:114554. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. Hu S. Liu L. Dang P. Liu Y. Sun Z. Qiao B. Wang C. Engineered exosomes from different sources for cancer-targeted therapy. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2023;8(1):124. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01382-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K. L. Wang Y. J. Sun J. et al., Artificial chimeric exosomes for anti-phagocytosis and targeted cancer therapy. Chem. Sci. 2018;10:1555–1561. doi: 10.1039/c8sc03224f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. J. Wu J. Y. Liu J. et al., Artificial exosomes for translational nanomedicine. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:242. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00986-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R. Gorai S. Devi A. et al., Exosome: a megastar of future cancer personalized and precision medicine. Clin. Transl. Discovery. 2023;3:e208. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotram R. Dhar R. Dhar D. Purushothaman K. Narasimhan A. K. Devi A. Fusion of Exosomes and Nanotechnology: Cutting-Edge Cancer Theranostics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024;7:8489–8506. [Google Scholar]

- Hussen B. M. Faraj G. S. H. Rasul M. F. Hidayat H. J. Salihi A. Baniahmad A. Taheri M. Ghafouri-Frad S. Strategies to overcome the main challenges of the use of exosomes as drug carrier for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):323. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02743-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M. Katzmann D. J. Estepa-Sabal E. J. Meerloo T. Emr S. D. Escrt-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for mvb sorting. Dev. Cell. 2002;3(2):271–282. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne W. M. Stenmark H. Emr S. D. Molecular mechanisms of the membrane sculpting ESCRT pathway. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2013;5(9):a016766. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. H. Hanson P. I. Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: it's all in the neck. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11(8):556–566. doi: 10.1038/nrm2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K. Hsu C. Chiantia S. Rajendran L. Wenzel D. Wieland F. Schwille P. Brügger B. Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel G. Charrin S. Simoes S. Romao M. Rochin L. Saftig P. Marks M. S. Rubinstein E. Raposo G. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and -dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2011;21(4):708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu Z. Yáñez-Mó M. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:442. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobardt M. D. Saphire A. C. Hung H. C. Yu X. Van der Schueren B. Zhang Z. David G. Gallay P. A. Syndecan captures, protects, and transmits HIV to T lymphocytes. Immunity. 2003;18(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baietti M. F. Zhang Z. Mortier E. Melchior A. Degeest G. Geeraerts A. Ivarsson Y. Depoortere F. Coomans C. Vermeiren E. Zimmermann P. David G. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14(7):677–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino A. Costa-Silva B. Shen T. L. Rodrigues G. Hashimoto A. Tesic Mark M. Molina H. Kohsaka S. Di Giannatale A. Ceder S. Singh S. Williams C. Soplop N. Uryu K. Pharmer L. King T. Bojmar L. Davies A. E. Ararso Y. Zhang T. Zhang H. Hernandez J. Weiss J. M. Dumont-Cole V. D. Kramer K. Wexler L. H. Narendran A. Schwartz G. K. Healey J. H. Sandstrom P. Labori K. J. Kure E. H. Grandgenett P. M. Hollingsworth M. A. de Sousa M. Kaur S. Jain M. Mallya K. Batra S. K. Jarnagin W. R. Brady M. S. Fodstad O. Muller V. Pantel K. Minn A. J. Bissell M. J. Garcia B. A. Kang Y. Rajasekhar V. K. Ghajar C. M. Matei I. Peinado H. Bromberg J. Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J. Arras G. Colombo M. Jouve M. Morath J. P. Primdal-Bengtson B. Dingli F. Loew D. Tkach M. Théry C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113(8):E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. Dhar R. Gurudas S. G. Dey D. Devi A. Jha S. K. Adhikari M. D. Gorai S. Clinical Impact of Exosomes in Colorectal Cancer Metastasis. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023;6(7):2576–2590. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.3c00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. Li A. Hu J. Feng L. Liu L. Shen Z. Recent developments in isolating methods for exosomes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023;10:1100892. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1100892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo M. de la Canal L. de Marcos Lousa C. A call for Rigor and standardization in plant extracellular vesicle research. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2021;10(6):e12048. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. Jin K. Gao L. Zhang Z. Li F. Zhou F. Zhang L. Methods and technologies for exosome isolation and characterization. Small Methods. 2018;2(9):1800021. [Google Scholar]

- Mateescu B. Jones J. C. Alexander R. P. Alsop E. An J. Y. Asghari M. Boomgarden A. Bouchareychas L. Cayota A. Chang H. C. Charest A. Chiu D. T. Coffey R. J. Das S. De Hoff P. deMello A. D'Souza-Schorey C. Elashoff D. Eliato K. R. Franklin J. L. Galas D. J. Gerstein M. B. Ghiran I. H. Go D. B. Gould S. Grogan T. R. Higginbotham J. N. Hladik F. Huang T. J. Huo X. Hutchins E. Jeppesen D. K. Jovanovic-Talisman T. Kim B. Y. S. Kim S. Kim K. M. Kim Y. Kitchen R. R. Knouse V. LaPlante E. L. Lebrilla C. B. Lee L. J. Lennon K. M. Li G. Li F. Li T. Liu T. Liu Z. Maddox A. L. McCarthy K. Meechoovet B. Maniya N. Meng Y. Milosavljevic A. Min B. H. Morey A. Ng M. Nolan J. De Oliveira Junior G. P. Paulaitis M. E. Phu T. A. Raffai R. L. Reátegui E. Roth M. E. Routenberg D. A. Rozowsky J. Rufo J. Senapati S. Shachar S. Sharma H. Sood A. K. Stavrakis S. Stürchler A. Tewari M. Tosar J. P. Tucker-Schwartz A. K. Turchinovich A. Valkov N. Van Keuren-Jensen K. Vickers K. C. Vojtech L. Vreeland W. N. Wang C. Wang K. Wang Z. Welsh J. A. Witwer K. W. Wong D. T. W. Xia J. Xie Y. H. Yang K. Zaborowski M. P. Zhang C. Zhang Q. Zivkovic A. M. Laurent L. C. Phase 2 of extracellular RNA communication consortium charts next-generation approaches for extracellular RNA research. iScience. 2022;25(8):104653. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M. Kar R. Ghosh S. Sonar S. Mirgh D. Sivakumar I. Nayak A. Muthusamy R. Clinical Impact of Multi-omics profiling of extracellular vesicles in cancer Liquid Biopsy. J. Liq. Biopsy. 2024;3:100138. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R. Gorai S. Devi A. Muthusamy R. Alexiou A. Papadakis M. Decoding of exosome heterogeneity for cancer theranostics. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023;13(6):e1288. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales P. A. Zhou H. Pisitkun T. Wang N. S. Star R. A. Knepper M. A. Yuen P. S. Isolation and purification of exosomes in urine. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;641:89–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-711-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales R. T. Ko J. Future of Digital Assays to Resolve Clinical Heterogeneity of Single Extracellular Vesicles. ACS Nano. 2022;16(8):11619–11645. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c04337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R. Devi A. Gorai S. Jha S. K. Alexiou A. Papadakis M. Exosome and epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A complex secret of cancer progression. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023;27(11):1603–1607. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W. Yang Y. Liu J. Xue J. Zhao H. Mao L. Zhao S. Tumor-derived exosomes promote macrophages M2 polarization through miR-1-3p and regulate the progression of liver cancer. Mol. Immunol. 2023;162:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2023.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier A. J. Elsawa S. F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(13):6995. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi M. Rezaie J. Tumor cells derived-exosomes as angiogenenic agents: possible therapeutic implications. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18(1):249. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02426-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini R. Asef-Kabiri L. Yousefi H. Sarvnaz H. Salehi M. Akbari M. E. Eskandari N. The roles of tumor-derived exosomes in altered differentiation, maturation and function of dendritic cells. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01376-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Zeng H. Zhang H. Han Y. The role of exosomal PD-L1 in tumor immunotherapy. Transl. Oncol. 2021;14(5):101047. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J. C. Puntigam L. Hofmann L. Jeske S. S. Beccard I. J. Doescher J. Laban S. Hoffmann T. K. Brunner C. Theodoraki M. N. Schuler P. J. Circulating Exosomes Inhibit B Cell Proliferation and Activity. Cancers. 2020;12(8):2110. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini R. Sarvnaz H. Arabpour M. Ramshe S. M. Asef-Kabiri L. Yousefi H. Akbari M. E. Eskandari N. Cancer exosomes and natural killer cells dysfunction: biological roles, clinical significance and implications for immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01492-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q. F. Li W. J. Hu K. S. Gao J. Zhai W. L. Yang J. H. Zhang S. J. Exosome biogenesis: machinery, regulation, and therapeutic implications in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01671-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li I. Nabet B. Y. Exosomes in the tumor microenvironment as mediators of cancer therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0975-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. Saha P. Kalele K. Sonar S. Clinical signature of exosomal tetraspanin proteins in cancer. Clin. Transl. Discovery. 2024;4:e341. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. Kim Y. Ha S. Sheller-Miller S. Yoo J. Choi C. Park C. H. The emerging role of exosomes as novel therapeutics: Biology, technologies, clinical applications, and the next. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021;85(2):e13329. doi: 10.1111/aji.13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström K. Valadi H. Sjöstrand M. Malmhäll C. Bossios A. Eldh M. Lötvall J. Characterization of mRNA and microRNA in human mast cell-derived exosomes and their transfer to other mast cells and blood CD34 progenitor cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2012;1:18389. doi: 10.3402/jev.v1i0.18389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Wang Y. Lin L. Wang J. Xiao H. Li J. Peng X. Dai H. Li L. Mast Cell-Derived Exosomes Promote Th2 Cell Differentiation via OX40L-OX40 Ligation. J. Immunol. Res. 2016;2016:3623898. doi: 10.1155/2016/3623898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skokos D. Botros H. G. Demeure C. Morin J. Peronet R. Birkenmeier G. Boudaly S. Mécheri S. Mast cell-derived exosomes induce phenotypic and functional maturation of dendritic cells and elicit specific immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 2003;170(6):3037–3045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H. Lässer C. Shelke G. V. Wang J. Rådinger M. Lunavat T. R. Malmhäll C. Lin L. H. Li J. Li L. Lötvall J. Mast cell exosomes promote lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation - role of KIT-stem cell factor signaling. Cell Commun. Signaling. 2014;12:64. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. Shelke G. V. Lässer C. Brismar H. Lötvall J. Extracellular vesicles from mast cells induce mesenchymal transition in airway epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2020;21(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01346-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. Zhao J. Cao M. Liu R. Chen G. Li S. Xie Y. Xie J. Cheng Y. Huang L. Su M. Xu Y. Zheng M. Zou K. Geng L. Xu W. Gong S. Mast cells-derived MiR-223 destroys intestinal barrier function by inhibition of CLDN8 expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Biol. Res. 2020;53(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s40659-020-00279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugini L. Cecchetti S. Huber V. Luciani F. Macchia G. Spadaro F. Paris L. Abalsamo L. Colone M. Molinari A. Podo F. Rivoltini L. Ramoni C. Fais S. Immune surveillance properties of human NK cell-derived exosomes. J. Immunol. 2012;189(6):2833–2842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pace A. L. Tumino N. Besi F. Alicata C. Conti L. A. Munari E. Maggi E. Vacca P. Moretta L. Characterization of Human NK Cell-Derived Exosomes: Role of DNAM1 Receptor In Exosome-Mediated Cytotoxicity Against Tumor. Cancers. 2020;12(3):661. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici C. Shahaj E. Cecchetti S. Camerini S. Casella M. Iessi E. Camisaschi C. Paolino G. Calvieri S. Ferro S. Cova A. Squarcina P. Bertuccini L. Iosi F. Huber V. Lugini L. Natural-Killer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Immune Sensors and Interactors. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong A. Y. Wu C. H. Li J. Sun J. Fabbri M. Wayne A. S. Seeger R. C. Large-scale isolation and cytotoxicity of extracellular vesicles derived from activated human natural killer cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2017;6(1):1294368. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1294368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. H. Li J. Li L. Sun J. Fabbri M. Wayne A. S. Seeger R. C. Jong A. Y. Extracellular vesicles derived from natural killer cells use multiple cytotoxic proteins and killing mechanisms to target cancer cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2019;8(1):1588538. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1588538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. Kalimuthu S. Oh J. M. Gangadaran P. Baek S. H. Jeong S. Y. Lee S. W. Lee J. Ahn B. C. Enhancement of antitumor potency of extracellular vesicles derived from natural killer cells by IL-15 priming. Biomaterials. 2019;190–191:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neviani P. Wise P. M. Murtadha M. Liu C. W. Wu C. H. Jong A. Y. Seeger R. C. Fabbri M. Natural Killer-Derived Exosomal miR-186 Inhibits Neuroblastoma Growth and Immune Escape Mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2019;79(6):1151–1164. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. Kalimuthu S. Gangadaran P. Oh J. M. Lee H. W. Baek S. H. Jeong S. Y. Lee S. W. Lee J. Ahn B. C. Exosomes Derived From Natural Killer Cells Exert Therapeutic Effect in Melanoma. Theranostics. 2017;7(10):2732–2745. doi: 10.7150/thno.18752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J. Sun L. Xu F. Liu L. Hu F. Song D. Hou Z. Wu W. Luo X. Wang J. Yuan X. Hu J. Wang G. M2 Macrophage-Derived Exosomes Promote Cell Migration and Invasion in Colon Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(1):146–158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. Ma T. Huang B. Lin L. Zhou Y. Yan J. Zou Y. Chen S. Macrophage-derived exosomal microRNA-501-3p promotes progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through the TGFBR3-mediated TGF-β signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binenbaum Y. Fridman E. Yaari Z. Milman N. Schroeder A. Ben D. G. Shlomi T. Gil Z. Transfer of miRNA in Macrophage-Derived Exosomes Induces Drug Resistance in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(18):5287–5299. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Y. W. Kang M. Kim H. Y. Han J. Kang S. Lee J. R. Jeong G. J. Kwon S. P. Song S. Y. Go S. Jung M. Hong J. Kim B. S. M1 Macrophage-Derived Nanovesicles Potentiate the Anticancer Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. ACS Nano. 2018;12(9):8977–8993. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Zuo X. Xiao Y. Liu D. Luo H. Zhu H. Neutrophil-derived exosome from systemic sclerosis inhibits the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;526(2):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z. Rong Y. Teng Y. Zhuang X. Samykutty A. Mu J. Zhang L. Cao P. Yan J. Miller D. Zhang H. G. Exosomes miR-126a released from MDSC induced by DOX treatment promotes lung metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36(5):639–651. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viaud S. Théry C. Ploix S. Tursz T. Lapierre V. Lantz O. Zitvogel L. Chaput N. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer immunotherapy: what's next? Cancer Res. 2010;70(4):1281–1285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. Jung I. Jung D. Kim C. S. Kang S. M. Ryu S. Choi S. J. Noh S. Jeong J. Lee B. Y. Park J. K. Shin J. Cho H. Heo J. I. Jeong Y. Choi S. H. Lee S. Y. Baek M. C. Yea K. Novel antitumor therapeutic strategy using CD4+ T cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Biomaterials. 2022;289:121765. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W. Lei C. Liu S. Cui Y. Wang C. Qian K. Li T. Shen Y. Fan X. Lin F. Ding M. Pan M. Ye X. Yang Y. Hu S. CAR exosomes derived from effector CAR-T cells have potent antitumour effects and low toxicity. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):4355. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12321-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshtkar S. Azarpira N. Ghahremani M. H. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0791-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao A. G. Shah K. Cromer B. Sumer H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Therapeutic Potential. Stem Cell. Int. 2020;2020:8825771. doi: 10.1155/2020/8825771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K. Cheng K. Stem cell-derived exosome versus stem cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2023;12:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s44222-023-00064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer C. Ohe J. V. Hass R. Anti-Tumor Effects of Exosomes Derived from Drug-Incubated Permanently Growing Human MSC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(19):7311. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. Zhu C. Jia J. Hao X. Y. Yu X. Y. Liu X. Y. Shu M. G. ADSC-Exos containing MALAT1 promotes wound healing by targeting miR-124 through activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40(5):BSR20192549. doi: 10.1042/BSR20192549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari H. Lázaro-Ibáñez E. Viitala T. Vuorimaa-Laukkanen E. Siljander P. Yliperttula M. Microvesicle- and exosome-mediated drug delivery enhances the cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel in autologous prostate cancer cells. J. Controlled Release. 2015;220(Pt B):727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralikumar M. Manoj Jain S. Ganesan H. Duttaroy A. K. Pathak S. Banerjee A. Current understanding of the mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer and aging. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021;31:e00658. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2021.e00658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside T. L. Exosome and mesenchymal stem cell cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Immunol. 2018;35:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. Zhang L. Luo X. Ma X. Wang G. Yang Y. Yan Y. Qian H. Zhang X. Xu W. Mao F. Systematic Exposition of Mesenchymal Stem Cell for Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Its Associated Colorectal Cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:9652817. doi: 10.1155/2018/9652817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten F. R. Grivennikov S. I. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 2019;51(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K. Cho S. W. The Evasion Mechanisms of Cancer Immunity and Drug Intervention in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:868695. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.868695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffey A. Storini C. Diceglie C. Martelli C. Sironi L. Calzarossa C. Tonna N. Lovchik R. Delamarche E. Ottobrini L. Bianco F. Mesenchymal stem cells from tumor microenvironment favour breast cancer stem cell proliferation, cancerogenic and metastatic potential, via ionotropic purinergic signalling. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):13162. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. K. Park S. R. Jung B. K. Jeon Y. K. Lee Y. S. Kim M. K. Kim Y. G. Jang J. Y. Kim C. W. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells suppress angiogenesis by down-regulating VEGF expression in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakravan K. Babashah S. Sadeghizadeh M. Mowla S. J. Mossahebi-Mohammadi M. Ataei F. Dana N. Javan M. MicroRNA-100 shuttled by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes suppresses in vitro angiogenesis through modulating the mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis in breast cancer cells. Cell. Oncol. 2017;40(5):457–470. doi: 10.1007/s13402-017-0335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M. Kosaka N. Tominaga N. Yoshioka Y. Takeshita F. Takahashi R. U. Yoshida M. Tsuda H. Tamura K. Ochiya T. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells contain a microRNA that promotes dormancy in metastatic breast cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 2014;7(332):ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara K. Ii M. Inamoto T. Nakagawa T. Ibuki N. Yoshikawa Y. Tsujino T. Uchimoto T. Saito K. Takai T. Tanda N. Minami K. Uehara H. Komura K. Hirano H. Nomi H. Kiyama S. Asahi M. Azuma H. microRNA-145 Mediates the Inhibitory Effect of Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells on Prostate Cancer. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25(17):1290–1298. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Feng Y. Zeng X. He M. Gong Y. Liu Y. Extracellular vesicles-encapsulated let-7i shed from bone mesenchymal stem cells suppress lung cancer via KDM3A/DCLK1/FXYD3 axis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021;25(4):1911–1926. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieu A. Lalu M. M. Slobodian M. Gnyra C. Fergusson D. A. Montroy J. Burger D. Stewart D. J. Allan D. S. An Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Preclinical Use. ACS Nano. 2020;14(8):9728–9743. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c01363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger L. Ezquer M. Lillo-Vera F. Pedraza P. L. Ortúzar M. I. González P. L. Figueroa-Valdés A. I. Cuenca J. Ezquer F. Khoury M. Alcayaga-Miranda F. Stem cell exosomes inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):663. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36855-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subha D. Harshnii K. Madhikiruba K. G. Nandhini M. Tamilselvi K. S. Plant derived exosome-like Nanovesicles: An updated overview. Plant Nano Biol. 2023;3:100022. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman T. The use of plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles as a delivery system of CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutics for editing long non-coding RNAs in cancer colon cells. Front. Oncol. 2023;13:1194350. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1194350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonar S. Anand K. Plant-derived exosomes: a green nanomedicine for cancer. Clin. Transl. Discovery. 2024;4:e333. [Google Scholar]

- Nyahatkar S. Kalele K. Plant exosomes: A natural medicine for oral cancer. Clin. Transl. Discovery. 2024;4:e269. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasati A. Syahruddin M. H. Nuryanti A. Ana I. D. Barlian A. Wijaya C. H. Ratnadewi D. Wungu T. D. K. Takemori H. Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications and Regenerative Therapy. Biomedicines. 2023;11(4):1053. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11041053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian M. Q. Chng W. H. Liang J. Yeo H. Q. Lee C. K. Belaid M. Tollemeto M. Wacker M. G. Czarny B. Pastorin G. Plant-derived extracellular vesicles: Recent advancements and current challenges on their use for biomedical applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2022;11(12):e12283. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. Yoo H. J. Jung J. H. Lee R. Hyun J. K. Park J. H. Na D. Yeon J. H. Cytotoxic Effects of Plant Sap-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on Various Tumor Cell Types. J. Funct. Biomater. 2020;11(2):22. doi: 10.3390/jfb11020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo S. Naselli F. Fontana S. Monteleone F. Lo Dico A. Saieva L. Zito G. Flugy A. Manno M. Di Bella M. A. De Leo G. Alessandro R. Citrus limon-derived nanovesicles inhibit cancer cell proliferation and suppress CML xenograft growth by inducing TRAIL-mediated cell death. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19514–19527. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X. Teng Y. Samykutty A. Mu J. Deng Z. Zhang L. Cao P. Rong Y. Yan J. Miller D. Zhang H. G. Grapefruit-derived Nanovectors Delivering Therapeutic miR17 Through an Intranasal Route Inhibit Brain Tumor Progression. Mol. Ther. 2016;24(1):96–105. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. Zu M. Gong H. Ma Y. Sun J. Ran S. Shi X. Zhang J. Xiao B. Tea leaf-derived exosome-like nanotherapeutics retard breast tumor growth by pro-apoptosis and microbiota modulation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12951-022-01755-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Zhao R. Cheng K. Zhang K. Wang Y. Zhang Y. Li Y. Liu G. Xu J. Xu J. Anderson G. J. Shi J. Ren L. Zhao X. Nie G. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Presenting Programmed Death 1 for Improved Cancer Immunotherapy via Immune Activation and Checkpoint Inhibition. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):16698–16711. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]