Abstract

IE1 is a principal transcriptional regulator of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV). Transactivation by IE1 is stimulated when early viral promoters are cis linked to homologous-region (hr) enhancer sequences of AcMNPV. This transcriptional enhancement is correlated with the binding of IE1 as a dimer to the 28-bp palindromic repeats comprising the hr enhancer. To define the role of homophilic interactions in IE1 transactivation, we have mapped the IE1 domains required for oligomerization. We report here that IE1 oligomerizes by a mechanism independent of enhancer binding, as demonstrated by in vitro pull-down assays using fusions of IE1 (582 residues) to the C terminus of glutathione S-transferase. In vivo oligomerization of IE1 was verified by immunoprecipitation of IE1 complexes from extracts of plasmid-transfected SF21 cells. Analyses of a series of site-directed IE1 insertion mutations indicated that a helix-loop-helix (HLH)-like domain extending from residue 543 to residue 568 is the primary determinant of oligomerization. Replacement of residues within the hydrophobic face of the putative dimerization domain disrupted IE1 homophilic interactions and caused loss of IE1 transactivation of hr-dependent promoters in plasmid transfection assays. Thus, oligomerization is required for IE1 transcriptional stimulation. HLH mutations also reduced IE1 stability and abrogated transactivation of non-hr-dependent promoters. These data support a model wherein IE1 oligomerizes prior to DNA binding to facilitate proper interaction with the symmetrical recognition sites within the hr enhancer and thereby promote the transcription of early viral genes.

The principal transcriptional regulator of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) is the immediate-early protein IE1. Highly conserved among members of the family Baculoviridae, IE1 regulates baculovirus early gene expression, as first demonstrated by plasmid transfection assays (2, 13, 15, 18–20, 22, 25, 28, 33, 36). In similar assays, IE1 was also required for late gene expression and is one of six viral factors required for plasmid DNA replication (17, 26, 30). Consistent with a role in viral transcription and DNA replication, IE1 is detected throughout infection and localizes to the nucleus, where it associates with viral DNA replication factories (5, 7, 29). A temperature-sensitive mutation has implicated IE1 in the proper timing of the AcMNPV life cycle (8, 34). Thus, the participation of IE1 in multiple viral processes suggests that it is essential for the achievement of productive infection.

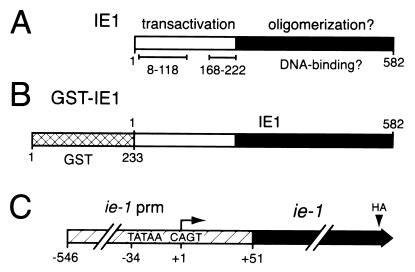

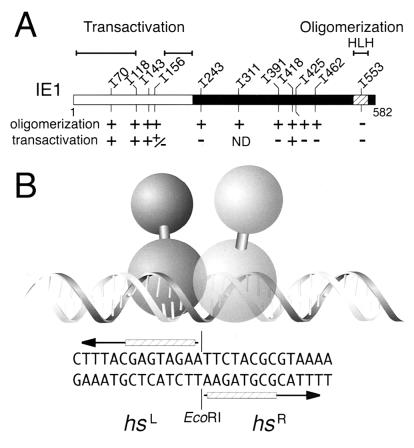

IE1 is a 582-residue (67-kDa) phosphoprotein with separable domains contributing to promoter transactivation and DNA binding (Fig. 1A). The N terminus of IE1 contains transcription-stimulatory domains (residues 8 to 118 and 168 to 222) that are dispensable for DNA binding (18, 38, 39). The C-terminal half of IE1 participates in DNA binding (18, 38), but the residues involved in binding site recognition are unknown. IE1 transactivation of viral early promoters is enhanced when the promoter is cis linked to AcMNPV homologous-region (hr) sequences, which function as transcription enhancers and possible origins of DNA replication (12, 14, 20, 22, 28, 32, 33, 36). The hr enhancer contains multiple copies of a 28- to 30-bp imperfect palindrome (28-mer) which is the minimal motif required for enhancer activity and plasmid DNA replication (11, 14, 22, 36, 37). Current evidence indicates that IE1 interacts specifically with the 28-mer as a dimer and must bind to both palindromic half sites for stimulation of hr enhancer activity (11, 20, 23, 37, 38).

FIG. 1.

Structure of IE1 and GST-IE1 fusions. (A) Functional domains. The 582-residue IE1 protein possesses transcriptional transactivation domains (residues 8 to 118 and 168 to 222) within its N-terminal half and unmapped DNA-binding and oligomerization domains within its C-terminal half. (B) GST-IE1. Residues 1 to 233 of GST (crosshatched) were fused to the N terminus of full-length IE1 (residues 1 to 582). (C) Genetic organization of ie-1HA expression plasmids. Sequences encoding the HA epitope were inserted into the ie-1 open reading frame after residue 579. The resulting ie-1HA gene or mutations thereof were placed under control of the full-length ie-1 promoter (prm; nucleotides −546 to +51) for transient-expression assays. Transcription initiates (arrow) from the CAGT (+1) initiator motif.

The binding of oligomeric IE1 to a symmetrical recognition sequence suggests that oligomerization contributes to IE1 functions. Indeed, the activity of transcriptional activators is often regulated by homophilic interactions (reviewed in references 27 and 31). Site-specific IE1 mutations that eliminate DNA binding have been characterized (18, 38). A subset of these mutated forms of IE1 fail to bind the palindromic 28-mer as a homodimer but retain the capacity to bind as a heterodimer with wild-type IE1 (38). In contrast, IE1 containing mutations in a C-terminal helix-loop-helix (HLH)-like domain fail to bind DNA as either a homodimer or a heterodimer (38). These findings suggested that oligomerization mediated by C-terminal IE1 residues is required for DNA binding and is therefore critical to IE1 function.

To investigate the role of oligomerization and define the molecular mechanism of IE1 transactivation, we used a combination of in vitro and in vivo assays that tested IE1 homophilic interactions. As determined by in vitro pull-down assays using glutathione S-transferase fused to the N terminus of IE1 (GST-IE1), we report here that IE1 oligomerizes in the absence of viral DNA and other cellular factors. Immunoprecipitations of differentially tagged IE1 synthesized in cultured cells confirmed that IE1 forms oligomeric complexes in vivo. By using a panel of site-specific IE1 mutations, we mapped the residues required for oligomerization to the HLH-like domain at the IE1 C terminus. Mutations that altered hydrophobic residues of the predicted helices eliminated oligomerization, both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, loss of IE1 oligomerization was concomitant with loss of positive activation of hr-dependent and non-hr-dependent promoters in plasmid transfection assays. Collectively, these findings indicated that IE1 homophilic interactions are required for promoter transactivation and support IE1's role as a sequence-specific, HLH-containing transregulator of early virus transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids. (i) IE1 insertions and substitutions.

IE1 insertion mutations were generated in pSP64/IE1 by using BglII linkers which inserted three to eight amino acids into the ie-1 open reading frame (38). IE1 amino acid substitutions were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of pIE1BS (33) and subsequently cloned into pSP64/IE1 for in vitro transcription and translation reactions (38). pIE1 encodes the wild-type ie-1 gene under the control of its own full-length promoter (28).

(ii) IE1HA and IE1FLAG expression plasmids.

pSP64/IE1 was digested with BstBI, end repaired with Klenow fragment, and ligated to an SpeI linker (5′-GG ACT AGT CC-3′) to form pSP64/IE1SpeI. After digestion with SpeI, the complementary oligonucleotides 5′-CT AGC ATG TAC CCA TAC GAC GTC CCA GAC TAC GCT G-3′ and 5′-CT AGC AGC GTA GTC TGG GAC GTC GTA TGG GTA CAT G-3′ were added by intramolecular ligation to give pSP64/IE1HA, in which 16 amino acid residues (GTSMYPYDVPDYAASP), including the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (underlined), were inserted after IE1 residue 579. Similarly, complementary oligonucleotides 5′-CT AGC GAC TAC AAA GAC GAT GAC GAT AAG CTT G-3′ and 5′-CT AGC AAG CTT ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC G-3′ were used to give pSP64/IE1FLAG, in which 15 amino acid residues (GTSDYKDDDDKLASP), including the FLAG (Eastman Kodak) epitope (underlined), were inserted after IE1 residue 579. Proper insertion of the epitope tags was verified by nucleotide sequencing. The NdeI-SstI fragment of pSP64/IE1HA was inserted into the corresponding sites of pIE1BS to generate pIE1HA/BS (Fig. 1C). pIE1HA insertion and substitution mutations were generated by inserting the appropriate restriction fragment from mutated pSP64/IE1 into the corresponding sites of pIE1HA/BS, including the Eco47III-NdeI fragment to give pIE1I70HA/BS, pIE1I118HA/BS, and pIE1I156HA/BS; the HpaI fragment to give pIE1I143HA/BS; the NdeI-AlwNI fragment to give pIE1I311HA/BS, pIE1I418HA/BS, pIE1I425HA/BS, and pIE1I553HA/BS; the NdeI-BstBI fragment to give pIE1I243HA/BS, pIE1I391HA/BS, and pIE1I462HA/BS; and the StuI-BstBI fragment to give pIE1(524/526)HA/BS, pIE1(537/538)HA/BS, pIE1(543/547)HA/BS, pIE1(550/554)HA/BS, pIE1(561/564)HA/BS, and pIE1(565/568)HA/BS. For the latter nine plasmids, the BstBI site at residue 579 within pIE1HA/BS was reinstated (GGG [Gly] → GAA [Glu]) by PCR mutagenesis.

(iii) GST-IE1 plasmids.

Sequences encoding GST residues 1 to 233 were fused to those encoding full-length IE1 (residues 1 to 582) (Fig. 1B). For expression in Escherichia coli, an ie-1-containing Sau3AI fragment from pIE1BS was inserted into the BamHI site of pGEX-3X (Pharmacia) to give pGEX/IE1 encoding GST-IE1. To generate pGEX/IE1 mutations, the appropriate restriction fragment was replaced with those of mutated pSP64/IE1 plasmids, including the NdeI-SphI fragment to give pGEX/IE1I243, pGEX/IE1I391, and pGEX/IE1I425 and the StuI-XbaI fragment to give pGEX/IE1(524/526), pGEX/IE1(550/554), pGEX/IE1(561/564), and pGEX/IE1(565/568).

(iv) Luciferase reporters.

The HindIII-NdeI fragment of pGEM-luc (Promega) encoding luciferase was inserted into the corresponding sites of p35 promoter-containing plasmids pBAS35K-CAT/28mer-up+ (36) and p(Δ3′-162/Δ5′-154)35K-CAT (9) to give pBAS35K-Luc/28mer-up+ and pFL35K-Luc, respectively. Through multiple steps, the polyadenylation signal from pIE1hr/PA (4) was subsequently inserted into each plasmid to give pBAS35K-Luc/28mer-up+/PA and pFL35K-Luc/PA, representing hr-dependent and UAR-dependent reporter plasmids, respectively.

(v) IE1 antigen expression plasmid.

After digestion with SpeI, pSP64/IE1SpeI was intramolecularly ligated to complementary oligonucleotides 5′-CT AGC CAC CAT CAC CAT CAC CAT TAA AGA TCT G-3′ and 5′-CT AGC AGA TCT TTA ATG GTG ATG GTG ATG GTG G-3′. The resulting plasmid, pSP64/IE1His, encodes IE1 with a His6 tag (GTSHHHHHH) and a stop codon inserted after residue 579. IE1His sequences were inserted into vector pET11b (Novagen) to give pET-IE1His. Sequences encoding IE1 residues 157 to 556 were subsequently removed by digestion with StuI and AlwNI, and the vector was end repaired with Klenow fragment and intramolecularly ligated to give pET-IE1HisΔ157-556.

In vitro protein synthesis.

Coupled in vitro transcription-translation reactions were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (TNT system; Promega). Circular plasmid DNA (0.6 μg) was added to mixtures (30 μl) containing rabbit reticulocyte lysate, amino acids, Tran35S-labeled methionine and cysteine (NEN), SP6 polymerase, and RNasin (Promega). After a 2-h incubation at 30°C, samples (3 μl) of the reaction mixture were subjected to denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Protein production was quantified by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager (model 450).

GST-IE1 binding assay.

E. coli strain JM83 harboring plasmids pGEX-3X or pGEX/IE1 was grown in Luria-Bertani broth with ampicillin. Cells were collected, suspended in NETN buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, protease inhibitors [Boehringer Mannheim]), and lysed by sonication. After clarification, glutathione-agarose beads (Pierce) were added and the combination was mixed for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were washed five times and suspended in NETN buffer to give a 50% (vol/vol) slurry. Protein was eluted from a sample of beads by boiling, and the yield was determined by SDS-PAGE and staining with colloidal Coomassie G-250 (Zaxis). To compare levels of in vitro IE1 protein bound as a measure of IE1 oligomerization, GST and GST-IE1 protein levels were normalized by diluting beads in NETN–0.5% dry milk. After washing with NETN–0.5% dry milk, a slurry of protein-bound beads (20 μl) was mixed with in vitro-synthesized, 35S-labeled IE1 (10 μl) in 500 μl of NETN–0.5% dry milk. After a 2-h incubation at 4°C, the beads were washed three times with NETN and bound protein was eluted by boiling. Proteins were quantified by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

An α-32P-end-labeled DNA probe containing the 28-mer of hr5 was prepared and mixed with in vitro-synthesized IE1 as described previously (38). Protein-DNA complexes were subjected to nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide-Tris-glycine gel electrophoresis also as previously described (37). For antibody supershifts, IE1HA- and IE1FLAG-bound DNA complexes were incubated with 12CA5 anti-HA (BAbCO) or M2 anti-FLAG (Eastman Kodak) monoclonal antibodies, respectively, prior to electrophoresis.

Cells and plasmid transfections.

Spodoptera frugiperda IPLB-SF21 (40) cells were propagated in TC100 growth medium (GIBCO Laboratories) supplemented with 2.6 mg of tryptose broth per ml and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. For transfections, SF21 cell monolayers were washed with TC100 and overlaid with a transfection mixture containing N-[1-(2,3-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium methyl sulfate–l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine, dioleoyl (C18:1, [cis]-9) (DOTAP-DOPE) and plasmid DNA in TC100. After 4 h at room temperature, the mixture was replaced with supplemented TC100.

Reporter transfection assays.

SF21 cells (2 × 106/60-mm-diameter plate) were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmid DNA (2 μg), either alone or with the indicated IE1HA-encoding plasmids (0.5 μg). Cells were collected 48 h later, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (21), and lysed by suspension in 250 μl of 1× cell culture lysis reagent (Promega). After clarification, the level of luciferase activity in the cell lysate (20 μl) was determined by using a luminometer (Monolight 3010) in accordance with the manufacturer's (Promega) instructions. When purified luciferase (Promega) was used, the assay was linear from 104 to 108 relative light units.

Immunoprecipitations.

SF21 cells (7 × 106/100-mm-diameter plate) were transfected with plasmid DNA (11 μg) encoding untagged, wild-type IE1 and IE1HA. Cells were collected 24 h later, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (21), and lysed by suspension in 900 μl of E1A buffer (250 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7], protease inhibitors) for 45 min on ice. After clarification by centrifugation (16,000 × g) for 10 min at 4°C, lysate (300 μl) was mixed with 918 μl of WCE buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7], 400 mM NaCl, 0.10 mM EGTA, protease inhibitors) containing ≈10 μg (2 μl) of HA.11 monoclonal antibody (α-HA; BAbCO). After 4 h on ice, a 50% slurry of protein G-Sepharose beads (Sigma) in WCE buffer was added and mixed for 6 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were washed six times with WCE buffer–0.1% SDS and eluted by boiling in 1% SDS–2.5% β-mercaptoethanol.

α-IE1 polyclonal serum.

Protein production was induced in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) harboring pET-IE1HisΔ157–556 by addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). After cell lysis, inclusion bodies were collected and solubilized in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole) containing 6 M urea. His-tagged protein was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (1), dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline, and concentrated. Protein purity was >95%, as judged by SDS-PAGE. New Zealand White rabbits were immunized, and antisera were prepared by the University of Wisconsin Medical School Polyclonal Antibody Service using standard procedures.

Immunoblot analysis.

Protein samples in SDS and β-mercaptoethanol were electrophoresed on SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gels. After protein transfer, nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with a 1:20,000 dilution of α-IE1, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or a 1:1,000 dilution of α-HA (HA.11), followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Signal development was performed by using nitroblue tetrazolium chloride-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt) colorimetric detection as described previously (16) or the Western-Star Chemiluminescent Detection System (Tropix).

Image processing.

Immunoblots were scanned at a resolution of 300 dots/in. by using a UMAX PowerLook III. The files were printed from Adobe Photoshop by using a Tektronics Phaser 450 dye sublimation printer.

RESULTS

In vitro oligomerization of IE1 in the absence of viral DNA.

In enhancer-dependent transactivation by IE1, the 28-mer palindromic repeats comprising the hr enhancer elements interact with dimeric IE1 (11, 18, 20, 22, 37, 38). Thus, IE1 oligomerization has been implicated as a required step in DNA-dependent transactivation (6, 37, 38). To investigate the role of IE1 oligomerization and to determine whether homophilic association is DNA dependent, we tested IE1 interactions by first using a pull-down assay involving GST fusion proteins.

GST-IE1, which consists of full-length IE1 (residues 1 to 582) fused to the C terminus of GST (Fig. 1B), was overproduced in E. coli and loaded onto glutathione-Sepharose beads. After incubation with in vitro-synthesized, [35S]methionine-labeled IE1, the GST-IE1 beads were washed extensively and protein was eluted. Significant binding of wild-type IE1 to GST-IE1 was detected (Fig. 2A, lane 3). In contrast, little, if any, binding of IE1 to GST alone occurred (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The specificity of IE1 binding to GST-IE1 was confirmed by testing for interaction with unrelated AcMNPV protein P35 (1, 10). In vitro-synthesized P35 failed to interact with GST or GST-IE1 (data not shown). We concluded that independently synthesized IE1 molecules have the capacity to oligomerize in the absence of hr enhancer DNA.

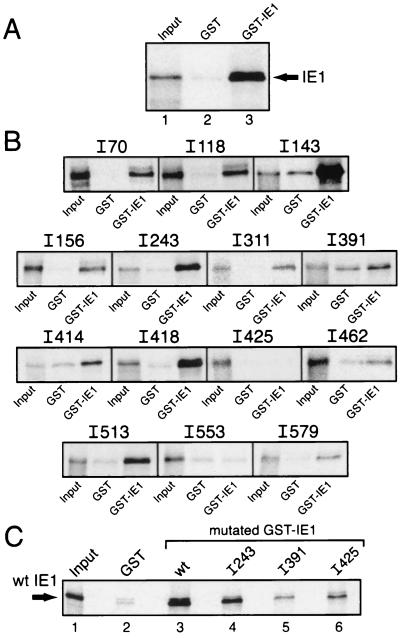

FIG. 2.

In vitro association of GST-IE1 with IE1. (A) GST-IE1 binding assay. In vitro-synthesized, 35S-labeled IE1 was mixed with glutathione-beads containing GST alone (lane 2) or GST-IE1 (lane 3). After washing, bound protein was eluted, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and imaged. (B) GST-IE1 association with IE1 insertions. 35S-labeled IE1 insertions were assayed for binding to GST alone and GST-IE1 as described for panel A. Mutated IE1s are designated by the amino acid residue preceding the insertion (38). (C) Wild-type (wt) IE1 association with GST-IE1 insertions. 35S-labeled IE1 was assayed for binding to GST alone (lane 2), GST-IE1 (lane 3), or GST-IE1 insertions (lanes 4 to 6) as described for panel A. For each binding assay (A to C), 1% of the 35S-labeled input protein (Input) was included.

Identification of IE1 domains required for in vitro oligomerization.

To map the domains required for IE1 oligomerization, we tested the effects of site-specific mutations on the ability of IE1 to interact with GST-IE1. We first screened a panel of 14 IE1 mutations containing three- to eight-residue insertions spanning the full-length protein (38). The mutated IE1s were synthesized in vitro and tested for oligomerization by using the GST-IE1 pull-down assay. A majority of the IE1 insertion mutations tested, including IE1I70, IE1I118, IE1I143, IE1I156, IE1I243, IE1I311, IE1I418, IE1I513, and IE1I579, associated with GST-IE1 at levels comparable to that of wild-type IE1 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that oligomerization was unaffected. In contrast, insertions IE1I391, IE1I414, IE1I425, IE1I462, and IE1I553 exhibited reduced levels of interaction, as judged by subtracting the level of 35S-labeled IE1 bound nonspecifically to GST alone from that bound specifically to GST-IE1. Of these insertions, IE1I425 and IE1I553 were the most impaired for GST-IE1 binding (Fig. 2B), which suggested that domains contributing to IE1 oligomerization were compromised by these mutations.

To verify these IE1 interactions, we used reciprocal binding assays. GST was fused to selected IE1 insertion mutations and subsequently tested for association with 35S-labeled wild-type IE1. As expected, GST-IE1I243 interacted with wild-type IE1 at levels comparable to that of GST-IE1 (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 4). Under these conditions, wild-type IE1 also interacted with GST-IE1I391 and GST-IE1I425 but at reduced levels (Fig. 2C, lanes 5 and 6). Although not analyzed here, the domain including residue 553 was characterized further by substitution mutagenesis (see below). Collectively, these in vitro data indicated that domains encompassing residues 391, 425, and 553 contribute directly or indirectly to IE1 intermolecular interactions.

Identification of IE1 domains required for in vivo oligomerization.

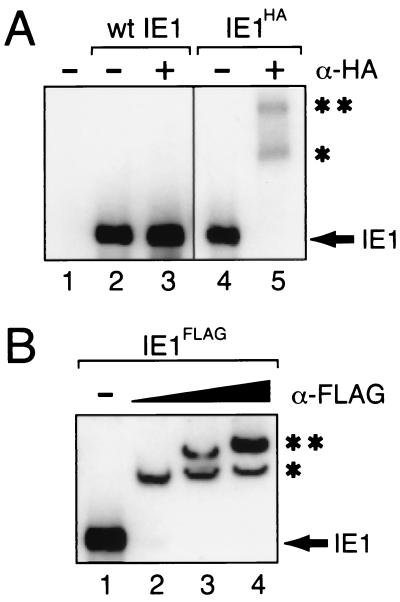

To verify that IE1 oligomerizes within the cell, we investigated IE1 interactions in vivo. To this end, we tagged IE1 at residue 579 with the influenza virus HA epitope (IE1HA) or the FLAG epitope (IE1FLAG). Transactivation by IE1HA was indistinguishable from that by wild-type, untagged IE1 (data not shown). DNA-binding activity was verified by EMSAs. Under these conditions, both IE1HA and IE1FLAG bound a DNA probe containing the 28-mer of the hr5 enhancer with an efficiency comparable to that of untagged IE1 (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 4, and B, lane 1). The presence of each epitope-tagged protein in the DNA complex was confirmed by using specific antiserum. HA-specific monoclonal antiserum α-HA yielded two supershifted IE1HA-containing complexes (Fig. 3A, lane 5). α-FLAG antiserum also detected two supershifted IE1FLAG-containing complexes. The proportion of the largest complex increased with increasing α-FLAG (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 to 4) and thus indicated the presence of two IE1FLAG molecules. These data demonstrated that dimeric IE1 binds to the single 28-mer, as expected (37, 38).

FIG. 3.

DNA binding by C-terminally epitope-tagged IE1. (A) EMSA using IE1HA. In vitro-synthesized, untagged IE1 (lanes 2 and 3) and IE1HA (lanes 4 and 5) were incubated with a 32P-labeled 28-mer DNA probe in the presence (+) or absence (−) of monoclonal antiserum α-HA. Complexes were subjected to nondenaturing PAGE and autoradiography. IE1-DNA complexes, alone (IE1) or bound by one (*) or two (**) antibodies, are indicated. In the absence of IE1 (lane 1), no DNA probe was bound. (B) EMSA using IE1FLAG. In vitro-synthesized IE1FLAG was incubated with a 28-mer DNA probe in the absence (−) (lane 1) or presence of increasing amounts of α-FLAG antiserum (lanes 2 to 4) and subjected to EMSA as described for panel A. wt, wild type.

To test for intracellular IE1 oligomerization, we used IE1HA in α-HA immunoprecipitation assays. SF21 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding IE1HA and untagged, wild-type IE1. The ie-1 promoter lacking hr enhancer sequences was used to direct ie-1 expression (Fig. 1C). α-HA immunoprecipitation of nonionic detergent lysates of transfected cells detected a complex containing both IE1 proteins, as shown by immunoblot analysis using α-IE1 antiserum (Fig. 4C, lane 3). Although untagged IE1 was readily detected in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 4B, lane 1), it was not immunoprecipitated by α-HA (Fig. 4C, lane 1). Thus, detection of untagged IE1 in immunoprecipitates was indicative of its capacity to complex directly or indirectly with IE1HA.

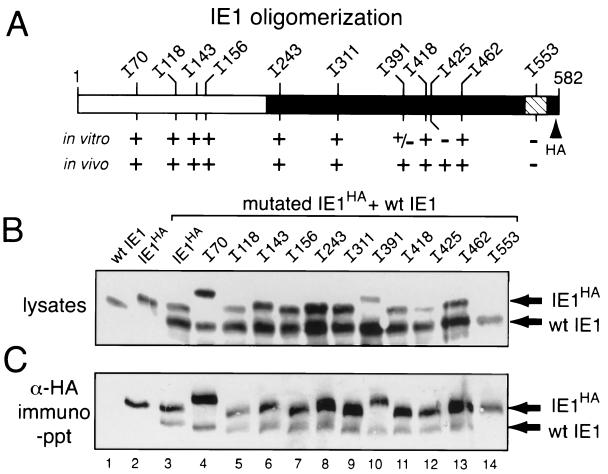

FIG. 4.

In vivo association of IE1 and IE1HA insertions. (A) IE1 insertions. The position of each insertion mutation within IE1HA is depicted. The ability (+) (see below) or inability (−) to oligomerize in vitro and in vivo is shown. (B) Intracellular levels of wild-type (wt) IE1 and IE1HA insertions. SF21 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type, untagged IE1 and wild-type IE1HA or the indicated IE1HA insertions. Plasmid levels were adjusted to provide comparable levels of protein, maintaining a constant plasmid level by supplementation with ie-1 promoter-containing plasmid pIE1-lacZ (3). Nonionic detergent extracts of cells were prepared 24 h after transfection. Samples (105 cell equivalents) representing 10% of that used for immunoprecipitation (see below) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using IE1-specific (α-IE1) serum. (C) Immunoprecipitations. HA-tagged proteins from transfected-cell extracts (106 cell equivalents) were immunoprecipitated (immuno-ppt) with HA-specific monoclonal antibody α-HA and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using α-IE1. IE1HA and wild-type IE1 proteins are indicated.

We therefore used immunoprecipitation assays of IE1 insertion mutations to define the residues required for in vivo IE1 oligomerization. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that all IE1 insertion mutations were synthesized in plasmid-transfected cells (Fig. 4B). However, the levels of IE1I553 were the lowest (Fig. 4B, lane 14), suggesting that its stability was reduced (see below). The IE1 insertion mutations capable of in vitro oligomerization, IE1I70, IE1I118, IE1I143, IE1I156, IE1I243, IE1I311, IE1I418, and IE1I462, complexed with untagged wild-type IE1 (Fig. 4C). IE1I391 and IE1I425 also maintained the capacity to oligomerize. Only IE1I553 failed to interact, despite the presence of excess wild-type IE1 (Fig. 4C, lane 14). Thus, of the insertion mutations tested, only IE1I553 was defective for oligomerization, both in vitro and in vivo. These data indicated that the domain encompassing residue 553 is a principal determinant of IE1 oligomerization.

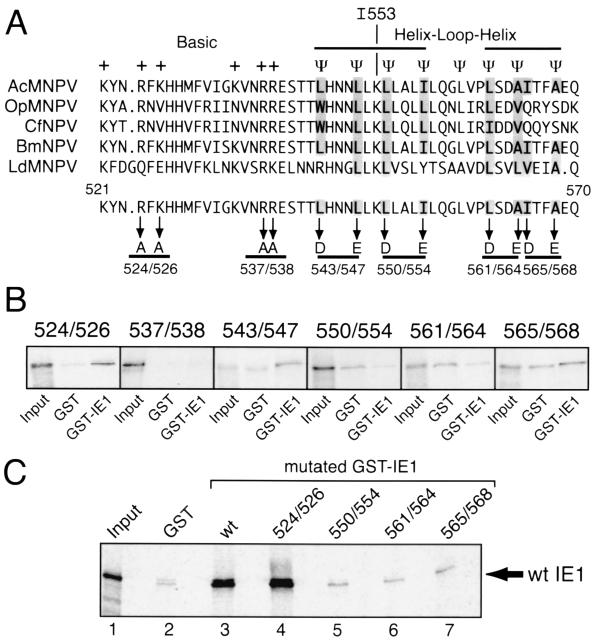

Requirement of a helix-loop-helix-like domain for IE1 oligomerization in vitro.

HLH domains are commonly required for oligomerization of transcription activators and often serve as the protein-protein interface (24, 27, 31, 35). IE1 residue 553 lies within a C-terminal region (Fig. 5A) predicted to contain two amphipathic α-helices preceded by a cluster of basic residues (18, 38). The high degree of conservation of this region among baculovirus IE1 proteins (Fig. 5A) is indicative of its relative importance for IE1 function. To define the function of this HLH-like domain, we determined the effects of selective amino acid substitutions on IE1 interactions in vitro. IE1 mutations were synthesized and tested for the capacity to interact by using the GST-IE1 pull-down assay. As shown previously (Fig. 2A), wild-type IE1 bound efficiently to GST-IE1 (data not shown). Replacement of pairs of hydrophobic residues with charged residues within the putative HLH (L543D-L547E, L550D-I554E, L561D-A564E, and I565D-A568E) diminished IE1's interaction with GST-IE1 to levels comparable to that with GST alone (Fig. 5B). Although replacement of adjacent arginines with alanine (R537A-R538A) also eliminated IE1 interaction, replacement of a nearby arginine-lysine pair (R524A-K526A) did not (Fig. 5B). Reciprocal GST-IE1 binding assays confirmed the binding differences between substitution R524A-K526A and the mutations within the HLH. GST-IE1R524A-K526A interacted with wild-type IE1 at levels comparable to that of GST-IE1 (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, only background levels of wild-type IE1 bound to substituted GST-IE1L550D-I554E, GST-IE1L561D-A564E, and GST-IE1I565D-A568E (Fig. 5C, lanes 5, 6, and 7). On the basis of these in vitro data, we concluded that hydrophobic residues within the putative helices contribute to oligomerization. R537 and R538 also contributed to IE1 in vitro interactions, but subsequent studies indicated that they were less important in vivo (see below).

FIG. 5.

In vitro association of GST-IE1 with HLH substitutions. (A) HLH-like domain of IE1. AcMNPV IE1 residues 521 to 570 were aligned with the corresponding IE1 residues from the indicated baculoviruses. Conserved basic (+) and hydrophobic (Ψ) residues (shaded) are depicted. Pairwise substitutions (underlined) are designated by position. (B) Binding to GST-IE1. The indicated IE1 mutations were synthesized in vitro with [35S]methionine and assayed for binding to GST alone and GST-IE1 as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (C) Binding to GST-IE1 substitutions. 35S-labeled wild-type (wt) IE1 was tested for binding to GST alone (lane 2), GST-IE1 (lane 3), or the indicated GST-IE1 substitutions (lanes 4 to 7). For each binding assay, 1% of the 35S-labeled input protein (Input) was included.

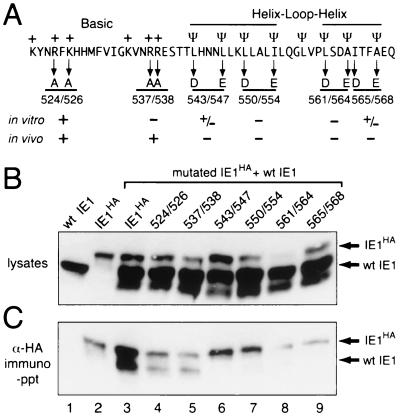

Requirement of the C-terminal HLH-like domain for IE1 oligomerization in vivo.

To verify that the HLH-like domain is required for intracellular IE1 oligomerization, we tested the effects of HLH substitutions on in vivo IE1 interactions as assayed by immunoprecipitation of extracts from plasmid-transfected cells (Fig. 6B). The steady state levels of all HLH substitution mutations were reduced compared to that of wild-type IE1, suggesting that defects within the HLH-like domain reduce IE1 stability. The least stable was IE1L561D-A564E (Fig. 6B, lane 8). Complexes containing IE1HA were precipitated with α-HA and subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-IE1 (Fig. 6C). Both IE1R524A-K526A and IE1R537A-R538A interacted with wild-type IE1 (Fig. 6C, lanes 4 and 5). Thus, replacement of R537 and R538 had less of an effect on IE1 oligomerization in vivo than in vitro. Despite the presence of excess wild-type IE1, mutations IE1L543D-L547E, IE1L550D-I554E, IE1L561D-A564E, and IE1I565D-A568E failed to complex with IE1 (Fig. 6C, lanes 6 to 9). Thus, all substitution mutations within the HLH-like domain abrogated in vivo IE1 oligomerization. Collectively, the in vivo and in vitro assays indicated that the hydrophobic residues within the HLH are required for IE1 oligomerization and contribute to IE1 stability.

FIG. 6.

In vivo association of IE1 and HLH substitutions. (A) IE1 substitution mutations. Pairs of residue substitutions designated by their positions are indicated below IE1 residues 521 to 570. The ability (+) or inability (−) of each IE1HA mutation to oligomerize in vitro and in vivo is shown. (B) Intracellular levels of wild-type (wt) IE1 and IE1HA mutations. SF21 cell extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection with plasmids encoding untagged wild-type IE1 and wild-type IE1HA or the indicated IE1HA substitutions as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Samples (105 cell equivalents) representing 10% of the amount used for immunoprecipitation (see below) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using α-IE1. (C) Immunoprecipitations. HA-tagged proteins from cell extracts (106 cell equivalents) were immunoprecipitated (immuno-ppt) with α-HA and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using α-IE1. IE1HA and wild-type IE1 proteins are indicated.

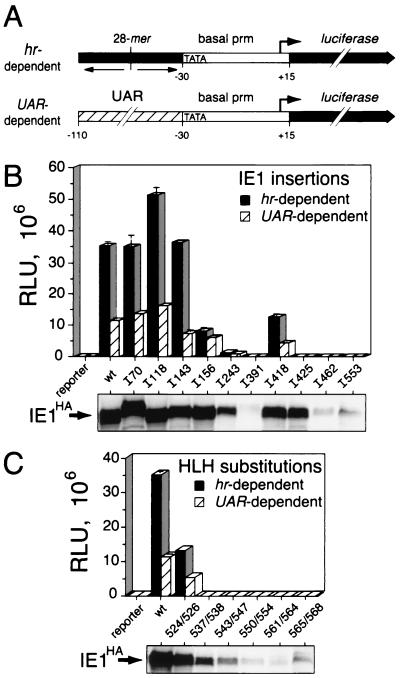

Requirement of oligomerization for transactivation by IE1.

IE1 mutations that disrupt binding to hr enhancer elements eliminate hr-dependent transactivation (18, 37). Since oligomerization should enhance the stability of the IE1 interaction with the palindromic 28-mer response elements within the hr enhancer (38), we predicted that oligomerization contributes to IE1 transactivation. To test this hypothesis, we compared the capacity of IE1 oligomerization-defective mutations to transactivate an hr-dependent promoter. To this end, we constructed a reporter plasmid (Fig. 7A) encoding the luciferase gene under control of the basal promoter of the AcMNPV p35 gene, which was linked to an upstream palindromic 28-mer of the hr5 enhancer. The minimal p35 basal promoter contains a TATA element and early RNA start site (+1) but lacks its viral upstream activating region (UAR) (9, 33, 36, 38). cis linkage of a single 28-mer in either orientation yields 40-fold stimulation of the p35 basal promoter by IE1 (37).

FIG. 7.

Transactivation by IE1HA mutations. (A) Luciferase reporters. For hr-dependent transcription, the luciferase gene under the control of the p35 basal promoter (prm; TATA element and RNA start site, +1) was linked to a single copy of the palindromic 28-mer from hr5, which is sufficient for enhancer activity. For UAR-dependent transcription, the luciferase gene was placed under the control of the full-length p35 promoter with UAR sequences −110 to −30 upstream from the TATA element. (B) IE1HA insertions. SF21 cells (2 × 106/plate) were transfected with reporter plasmid DNA (2 μg) alone or with reporter plasmid DNA and plasmid DNA (0.5 μg) encoding the indicated IE1HA. Cell lysates were prepared 48 h later and assayed for luciferase. The values for hr-dependent (solid bar) and UAR-dependent (striped bar) transactivation are averages ± standard deviations of triplicate transfections and are reported as relative light units (RLU). IE1HA levels were determined by immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates (2.4 × 105 cell equivalents) using α-HA. (C) IE1HA substitutions. Plasmid transfection assays were conducted by using hr-dependent (solid bar) and UAR-dependent (striped bar) reporters and the indicated IE1HA substitutions as described for panel B. IE1HA levels were also determined as described for panel B. wt, wild type.

Levels of transactivation by IE1HA mutations were determined by plasmid transfection assays. IE1HA synthesis in transfected cells was confirmed by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates (Fig. 7B and C). Several mutated IE1s were produced at lower levels, including oligomerization-defective IE1I553, IE1L543D-L547E, IE1L550D-I554E, IE1L561D-A564E, and IE1I565D-A568E. Transactivation of the hr-dependent reporter by oligomerization-competent insertion mutations IE1I70, IE1I118, and IE1I143 was greater than or equal to that of wild-type IE1HA (Fig. 7B, solid bar). Oligomerization-competent IE1I156 and IE1I418 showed reduced transactivation, whereas oligomerization-competent IE1I243, IE1I391, IE1I425, and IE1I462 were transactivation defective (Fig. 7B, solid bar). Likewise, oligomerization-defective IE1I553 failed to transactivate. Of the oligomerization-competent substitution mutations, IE1R524A-K526A exhibited 40% of wild-type transactivation but IE1R537A-R538A was inactive (Fig. 7C, solid bar). Oligomerization-defective HLH mutations IE1L543D-L547E, IE1L550D-I554E, IE1L561D-A564E, and IE1I565D-A568E failed to transactivate (Fig. 7C, solid bar).

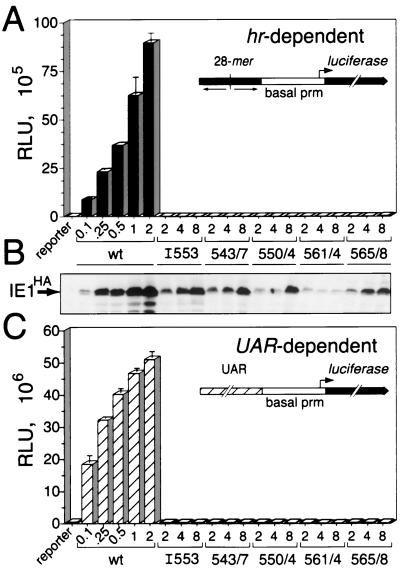

To determine whether the observed instability of oligomerization-defective IE1 was solely responsible for the loss of function, we tested for transactivation by IE1 mutations in dose-dependent transfection assays by using the hr-dependent luciferase reporter (Fig. 8A, inset). As expected, increased levels of plasmid DNA encoding wild-type IE1HA yielded a proportional increase in reporter activation (Fig. 8A) and IE1HA synthesis (Fig. 8B). With the exception of IE1L561D-A564E, all oligomerization-defective mutations, including IE1I553, IE1L543D-L547E, IE1L550D-I554E, and IE1I565D-A568E, were produced at levels greater than the lowest level of wild-type IE1 (Fig. 8B). Despite increased intracellular levels, none of these IE1 mutations transactivated the hr-dependent reporter (Fig. 8A). Thus, although loss of oligomerization reduced IE1 levels, this instability was not exclusively responsible for loss of IE1 function. We concluded that IE1 oligomerization is required for hr enhancer-dependent transactivation.

FIG. 8.

Dose response of transactivation by oligomerization-defective IE1HA. (A) hr-dependent luciferase reporter activity. SF21 cells (2 × 106/plate) were transfected with 2 μg of the hr-dependent reporter plasmid (inset) and increasing amounts (micrograms) of the indicated IE1HA plasmids. A constant level of plasmid DNA was maintained by supplementation with ie-1 promoter (prm)-containing plasmid pIE1-lacZ (3). Luciferase reporter activity was determined 48 h after transfection as described in the legend to Fig. 7. (B) Immunoblots. IE1HA levels were determined by immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates (2 × 105 cell equivalents) by using α-HA. (C) UAR-dependent luciferase reporter activity. SF21 cells (2 × 106/plate) were transfected with 2 μg of the UAR-dependent reporter plasmid (inset) and increasing amounts (micrograms) of the indicated IE1HA plasmids and then assayed for luciferase activity as described for panel A. wt, wild type.

IE1 oligomerization is required for transactivation of non-hr promoters.

Certain AcMNPV early promoters are highly responsive to IE1 transactivation in the absence of cis-linked hr elements (2, 13, 18, 19, 25, 28, 33). For example, the AcMNPV p35 promoter is stimulated more than 1,000-fold by IE1 (28, 33). There is no evidence that IE1 binds to this promoter or its UAR (37). Thus, to ascertain whether IE1 oligomerization is also necessary for non-hr transactivation, we tested IE1 mutations for stimulation of the luciferase gene placed under the control of the full-length p35 promoter (Fig. 7A). Levels of IE1HA in transfected SF21 cells (not shown) were comparable to those observed in hr-reporter transfections (Fig. 7B and C).

The UAR-dependent p35 promoter was transactivated by oligomerization-competent IE1I70 and IE1I118 at or above the level of transactivation by wild-type IE1HA. Mutated IE1I143, IE1I156, and IE1I418 transactivated at levels that were >40% of the wild-type IE1 level (Fig. 7B, striped bars). In contrast, oligomerization-competent IE1I243, IE1I391, IE1I425, and IE1I462 failed to transactivate the UAR-dependent promoter (Fig. 7B, striped bars). Oligomerization-defective IE1I553 also failed to transactivate. Likewise, oligomerization-defective HLH substitutions IE1L543D-L547E, IE1L550D-I554E, IE1L561D-A564E, and IE1I565D-A568E were transactivation defective (Fig. 7C, striped bars). Of the oligomerization-competent mutations, IE1R524A-K526A exhibited 50% of wild-type activity but IE1R537A−R538A was inactive (Fig. 7C, striped bars).

To rule out the possibility that the instability of oligomerization-defective IE1 caused loss of non-hr transactivation, we also tested the activity of the IE1 mutations in dose-dependent transfection assays by using the UAR-dependent p35 reporter (Fig. 8C, inset). The intracellular levels (not shown) of the oligomerization-defective IE1 mutations were indistinguishable from those in the hr-dependent reporter assays (Fig. 8B). All IE1 mutations, excluding IE1L561D−A564E, were produced at levels greater than the lowest level of wild-type IE1. Despite increased intracellular levels, none of these IE1 mutations transactivated the UAR-dependent reporter (Fig. 8C). We concluded that oligomerization is also necessary for non-hr transactivation by IE1. Thus, proper homophilic interactions by IE1 are necessary for transcriptional stimulation of distinct early promoters.

DISCUSSION

The activity of transcriptional activators is often regulated by homophilic interactions. Many HLH-containing transcriptional activators homo-oligomerize through HLH interactions to form an active dimer capable of binding to palindromic DNA recognition sites (reviewed in references 24, 27, 31, and 35). Similarly, baculovirus IE1 binds as a dimer to the palindromic 28-mer enhancer element of the hrs (11, 37). We report here that hr-dependent transactivation by IE1 requires IE1 homo-oligomerization, which occurs in a DNA-independent manner. Our data build a model (Fig. 9) in which IE1 dimers assemble upon synthesis and interact directly with symmetrical recognition sites comprising the 28-mer as a prerequisite to enhancer-dependent transcriptional activation.

FIG. 9.

Role of oligomerization in IE1 transactivation. (A) Summary of IE1 mutations. The capacity of each IE1HA mutation to oligomerize in vivo (+ or −) and to transactivate hr-dependent promoters (+ or −) is shown. ND, not determined. Residues comprising the transactivation and HLH-like domains are indicated (overlined). Residues constituting the DNA-binding domain(s) remain undefined. (B) Model of dimeric IE1 binding to the 28-mer of hr5. The imperfect palindrome of the 28-mer is bisected by an EcoRI site. Each IE1 monomer interacts with a half site (hs) by contacting the top strand of hsL and the bottom strand of hsR (striped boxes) (23). The monomers interact across the EcoRI site through their HLH-like domains. IE1 is depicted with separable transactivation (upper orb) and DNA-binding (lower orb) domains.

IE1 oligomerization mediated by an HLH interface.

The C terminus of IE1, which contains an HLH-like domain, was previously implicated in IE1 homophilic interactions (18, 38). Our mutational analyses described here indicated that multiple domains contribute to the capacity of IE1 to oligomerize in vitro (Fig. 2 and 5). However, only mutations that disrupted the HLH-like domain (residues 543 to 568) caused loss of oligomerization both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 4 and 6). Thus, the HLH motif is the principal contributor to IE1 oligomerization. This conclusion is supported by the previous finding that IE1 binding to 28-mer DNA as a heterodimer with wild-type IE1 was selectively compromised by mutations in the HLH domain (38). As predicted from studies on the oligomerization domains of known HLH-containing transcriptional activators (24, 27, 31), replacement of the hydrophobic residues comprising the HLH-like domain of IE1 eliminated oligomerization (Fig. 6). By analogy, it is likely that the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic helices participates directly in these homophilic interactions. Under the conditions we used, IE1-IE1 interaction was sufficiently strong that oligomerization was readily detected in the absence of DNA binding, suggesting that IE1 oligomerization occurs prior to hr binding. It is unknown whether the HLH-like domain is sufficient to mediate oligomerization. The finding that domains centered at residues 391 and 425 (Fig. 2) also affected in vitro oligomerization suggests that other regions contribute indirectly to IE1 homophilic interactions.

Oligomerization-dependent transactivation by IE1.

Of 11 IE1 insertion mutations, 5 failed to transactivate an hr-dependent promoter (Fig. 9A). However, all of these mutated IE1s retained the capacity to homo-oligomerize, with the exception of the insertion at residue 553. On the basis that all oligomerization-defective mutations, including substitutions within the HLH, caused loss of IE1 transactivation (Fig. 9A), we concluded that oligomerization is required for hr-dependent transactivation. Since transactivation is directly correlated with the capacity of IE1 to bind the palindromic 28-mer of the hr element (11, 20, 22, 37), it is likely that oligomerization contributes directly to DNA binding (see below). Consistent with this conclusion, in vitro biochemical studies indicated that each of the oligomerization-defective IE1s analyzed here failed to bind 28-mer DNA (38). Nonetheless, our studies indicated that oligomerization-defective IE1 also failed to transactivate IE1-responsive promoters that lack obvious hr-related sequences, including the full-length p35 promoter (Fig. 7 and 8). Thus, oligomerization also contributes to transactivation functions other than DNA binding. Possibilities include oligomerization-dependent conformational changes in IE1 that facilitate interaction with or recruitment of cellular factors contributing to RNA polymerase II transcription at early promoters. Consistent with oligomerization-induced conformational changes, oligomerization-defective IE1 exhibited marked instability compared to oligomerization-competent IE1, as suggested by the reduced steady-state levels of these IE1 mutations (Fig. 7 and 8). In particular, the substitution mutations within the HLH-like domain, which were expected to have minor effects on overall IE1 conformations, exhibited the greatest instability. These findings suggested that oligomerization contributes to proper protein folding.

Model for DNA binding by IE1: role of oligomerization.

Our data reported here, combined with previous studies (20, 23, 37, 38), suggest that IE1 oligomerization orients each IE1 subunit for proper interaction with the two half sites of the 28-mer. In this model (Fig. 9B), the preassembled IE1 dimer interacts across the 28-mer axis of symmetry to make simultaneous contact with both half sites in order to achieve transcriptional enhancement. The demonstration here of two supershifted DNA-protein species (Fig. 3) and the detection of discrete heterodimers (37, 38) by EMSA verified that the IE1–28-mer complex contains two molecules of IE1. The requirement for a critical spacing of the 28-mer half sites suggests that simultaneous interaction with both half sites is needed for enhancer activation (37). Both half sites are also required for optimal IE1 interaction in vitro (37). Moreover, since a single half site is sufficient to bind IE1 but insufficient to stimulate transcription, it is likely that interaction with dual half sites induces an uncharacterized change in IE1 or the interacting DNA which promotes enhancer activity. Thus, the binding of preformed IE1 dimers likely facilitates proper contact with the 28-mer half sites.

DNA binding by IE1.

In many basic-HLH domain-containing transactivators, the consequence of dimerization is the juxtaposition of two regions rich in basic residues that form a DNA-binding interface (24, 27, 31, 35). By analogy, the basic residues preceding the HLH-like domain of IE1 (Fig. 5) were predicted to be involved in hr binding. Replacement of R524 and K526 with alanine had little effect on IE1 oligomerization (Fig. 5 and 6) or in vitro DNA binding (38). In contrast, replacement of residues R537 and R538, located immediately adjacent to the predicted HLH, caused loss of in vitro DNA binding as homo- and heterodimers (38) and eliminated IE1 transactivation (Fig. 7C). Subsequent studies indicated that IE1 nuclear localization was compromised by R537-R538 substitutions, possibly explaining the loss of transactivation (V. A. Olson, unpublished data). Although direct participation in DNA interactions by the these basic residues has not been resolved, other IE1 domains contribute to DNA binding. Mutagenesis of the conserved basic region centered at residue 156 also caused loss of in vitro DNA binding (38). Our studies reported here have shown that IE1I156 is impaired in hr-dependent transactivation but not non-hr-dependent transactivation (Fig. 7). Since IE1I156 is oligomerization competent (Fig. 2 and 4), its loss of DNA binding may be due to the disruption of a DNA (hr)-binding domain. These results imply that IE1 differs from other basic-HLH transcriptional activators by possessing multiple DNA-binding domains. Further studies are required to identify the regions of IE1 involved in hr binding.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bob Liu for the construction of several of the plasmids used in this study and for helpful discussions. Steve Rodems and Steve Pullen also provided plasmids and insight.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AI25557 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertin J, Mendrysa S M, LaCount D J, Gaur S, Krebs J F, Armstrong R C, Tomaselli K J, Friesen P D. Apoptotic suppression by baculovirus P35 involves cleavage by and inhibition of a virus-induced CED-3/ICE-like protease. J Virol. 1996;70:6251–6259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6251-6259.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson D D, Summers M D, Guarino L A. Transient expression of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus immediate-early gene, IE-N, is regulated by three viral elements. J Virol. 1991;65:945–951. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.945-951.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cartier J L. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin—Madison; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartier J L, Hershberger P A, Friesen P D. Suppression of apoptosis in insect cells stably transfected with baculovirus p35: dominant interference by N-terminal sequences p351–76. J Virol. 1994;68:7728–7737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7728-7737.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm G E, Henner D J. Multiple early transcripts and splicing of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE-1 gene. J Virol. 1988;62:3193–3200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.9.3193-3200.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J, Guarino L A. The baculovirus transactivator IE1 binds to viral enhancer elements in the absence of insect cell factors. J Virol. 1995;69:4548–4551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4548-4551.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi J, Guarino L A. Expression of the IE1 transactivator of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus during viral infection. Virology. 1995;209:99–107. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi J, Guarino L A. A temperature-sensitive IE1 protein of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus has altered transactivation and DNA binding activities. Virology. 1995;209:90–98. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson J A, Friesen P D. Identification of upstream promoter elements mediating early transcription from the 35,000-molecular-weight protein gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1991;65:4006–4016. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4006-4016.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher A J, Cruz W, Zoog S J, Schneider C L, Friesen P D. Crystal structure of baculovirus P35: role of a novel reactive site loop in apoptotic caspase inhibition. EMBO J. 1999;18:2031–2039. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarino L A, Dong W. Functional dissection of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus enhancer element hr5. Virology. 1994;200:328–335. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarino L A, Gonzalez M A, Summers M D. Complete sequence and enhancer function of the homologous DNA regions of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1986;60:224–229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.224-229.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarino L A, Summers M D. Functional mapping of a trans-activating gene required for expression of a baculovirus delayed-early gene. J Virol. 1986;57:563–571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.563-571.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarino L A, Summers M D. Interspersed homologous DNA of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus enhances delayed-early gene expression. J Virol. 1986;60:215–223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.215-223.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guarino L A, Summers M D. Nucleotide sequence and temporal expression of a baculovirus regulatory gene. J Virol. 1987;61:2091–2099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2091-2099.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershberger P A, LaCount D J, Friesen P D. The apoptotic suppressor P35 is required early during baculovirus replication and is targeted to the cytosol of infected cells. J Virol. 1994;68:3467–3477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3467-3477.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kool M, Ahrens C H, Goldbach R W, Rohrmann G F, Vlak J M. Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11212–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs G R, Choi J, Guarino L A, Summers M D. Functional dissection of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus immediate-early 1 transcriptional regulatory protein. J Virol. 1992;66:7429–7437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7429-7437.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacs G R, Guarino L A, Summers M D. Novel regulatory properties of the IE1 and IE0 transactivators encoded by the baculovirus Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1991;65:5281–5288. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5281-5288.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kremer A, Knebel-Morsdorf D. The early baculovirus he65 promoter: on the mechanism of transcriptional activation by IE1. Virology. 1998;249:336–351. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H H, Miller L K. Isolation of genotypic variants of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1978;27:754–767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.27.3.754-767.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leisy D J, Rasmussen C, Kim H T, Rohrmann G F. The Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus homologous region 1a: identical sequences are essential for DNA replication activity and transcriptional enhancer function. Virology. 1995;208:742–752. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leisy D J, Rohrmann G F. The Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus IE-1 protein complex has two modes of specific DNA binding. Virology. 2000;274:196–202. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littlewood T D, Evan G I. Transcription factors 2: helix-loop-helix. Protein Profile. 1995;2:621–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu A, Carstens E B. Immediate-early baculovirus genes transactivate the p143 gene promoter of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1993;195:710–718. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu A, Miller L K. The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J Virol. 1995;69:975–982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.975-982.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massari M E, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nissen M S, Friesen P D. Molecular analysis of the transcriptional regulatory region of an early baculovirus gene. J Virol. 1989;63:493–503. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.493-503.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okano K, Mikhailov V S, Maeda S. Colocalization of baculovirus IE-1 and two DNA-binding proteins, DBP and LEF-3, to viral replication factories. J Virol. 1999;73:110–119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.110-119.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passarelli A L, Miller L K. Three baculovirus genes involved in late and very late gene expression: ie-1, ie-n, and lef-2. J Virol. 1993;67:2149–2158. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2149-2158.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patikoglou G, Burley S K. Eukaryotic transcription factor-DNA complexes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:289–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson M N, Bjornson R M, Pearson G D, Rohrmann G F. The Autographa californica baculovirus genome: evidence for multiple replication origins. Science. 1992;257:1382–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1529337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pullen S S, Friesen P D. Early transcription of the ie-1 transregulator gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus is regulated by DNA sequences within its 5′ noncoding leader region. J Virol. 1995;69:156–165. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.156-165.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribeiro B M, Hutchinson K, Miller L K. A mutant baculovirus with a temperature-sensitive IE-1 transregulatory protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1075–1084. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1075-1084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson K A, Lopes J M. Survey and summary: Saccharomyces cerevisiae basic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodems S M, Friesen P D. The hr5 transcriptional enhancer stimulates early expression from the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus genome but is not required for virus replication. J Virol. 1993;67:5776–5785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.5776-5785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodems S M, Friesen P D. Transcriptional enhancer activity of hr5 requires dual-palindrome half sites that mediate binding of a dimeric form of the baculovirus transregulator IE1. J Virol. 1995;69:5368–5375. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5368-5375.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodems S M, Pullen S S, Friesen P D. DNA-dependent transregulation by IE1 of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: IE1 domains required for transactivation and DNA binding. J Virol. 1997;71:9270–9277. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9270-9277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slack J M, Blissard G W. Identification of two independent transcriptional activation domains in the Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE1 protein. J Virol. 1997;71:9579–9587. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9579-9587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaughn J L, Goodwin R H, Thompkins G L, McCawley P. Establishment of two insect cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae) In Vitro. 1977;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]