Abstract

The drivers of immune evasion are not entirely clear, limiting the success of cancer immunotherapies. Here we applied single-cell spatial and perturbational transcriptomics to delineate immune evasion in high-grade serous tubo-ovarian cancer. To this end, we first mapped the spatial organization of high-grade serous tubo-ovarian cancer by profiling more than 2.5 million cells in situ in 130 tumors from 94 patients. This revealed a malignant cell state that reflects tumor genetics and is predictive of T cell and natural killer cell infiltration levels and response to immune checkpoint blockade. We then performed Perturb-seq screens and identified genetic perturbations—including knockout of PTPN1 and ACTR8—that trigger this malignant cell state. Finally, we show that these perturbations, as well as a PTPN1/PTPN2 inhibitor, sensitize ovarian cancer cells to T cell and natural killer cell cytotoxicity, as predicted. This study thus identifies ways to study and target immune evasion by linking genetic variation, cell-state regulators and spatial biology.

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Translational immunology, Sequencing, Genetic techniques

Here the authors provide a resource for ovarian cancer combining spatial transcriptomics, genomics, CRISPR Perturb-seq screens and in silico methods to focus on T cells and natural killer cells in the tumor and their role in immune evasion.

Main

Multicellular dysregulation has an important function in the initiation and progression of a wide range of diseases, including cancer, where tumor development and accompanying immune responses depend on (and shape) the location of different cell-type populations, tissue properties and organization1–3. Cellular and animal models have been instrumental in identifying central immune suppressors4–6 and have resulted in major breakthroughs in cancer treatment. However, many patients with cancer do not respond to current immunotherapies7–9, resulting, at least in part, from two central gaps. First, in contrast to the study of cancer genetics, in which genome sequencing of tumors across large and diverse patient populations has provided a foundation to study the genetic basis of cancer and develop targeted therapies, we still lack equivalent maps for tumor tissue organization to study the inherently spatial processes of multicellular dynamics and immune exclusion in patients. Second, identifying the regulators of cell states and reciprocal intercellular interactions poses additional challenges and requires functional interrogation across a larger search space of combinatorial gene–environment perturbations.

In tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC)—the most common and aggressive form of ovarian cancer10—these gaps are pronounced. HGSC is often diagnosed at advanced stages, and is prone to chemoresistance, resulting in a 5-year survival rate below 50%10. HGSC genetics has been thoroughly characterized11–14, demonstrating nearly ubiquitous TP53 mutations and massive copy number alterations (CNAs), with some tumors also presenting with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations and homologous recombination deficiency. Abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are a robust prognostic marker of positive clinical outcomes in patients with HGSC15,16. Yet, while single-cell studies have provided important resources and insight into HGSC cell biology17,18, the molecular and cellular modalities that promote or suppress immune recruitment and infiltration in HGSC are unclear, and existing immunotherapies continue to have limited success in treating HGSC19,20.

Here, we provide a molecular map of HGSC spatial organization, that, in conjunction with data-driven experimental design and high-content CRISPR screens, enabled us to systematically uncover molecular and cellular regulators of HGSC tumor immunity, as well as genetic and pharmacological perturbations that affect it.

Results

Single-cell spatial transcriptomic mapping of HGSC

To spatially map HGSC in the setting of metastatic disease, we applied in situ imaging with high-plex RNA detection at single-cell resolution to 130 HGSC tumors from a total of 94 patients to generate 202 tissue profiles, yielding a total of 2,598,277 high-quality single-cell spatial transcriptomes (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1a,b). Tumor tissues were obtained from the adnexa (ovaries/fallopian tube, n = 84), and/or omentum (n = 46), with 36 patient-matched pairs of adnexal and omental tumors. All tumor tissue profiles were obtained from debulking surgeries in either the treatment-naive or the neoadjuvant chemotherapy-treated setting (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2a,b). Associated patient clinical data including treatment history (for example, PARP inhibitor, bevacizumab and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)) and survival outcomes are also available (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Table 2a,b and Methods). Eight patients in this cohort received ICB treatment, but in all cases ICB treatment was after sample collection. For 40 patients, we also obtained DNA sequencing data spanning a 648-gene panel (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1b and Methods), focused on actionable single-nucleotide variations, somatic CNAs, chromosomal rearrangements and tumor mutational burden (TMB), providing a basis to link tissue structure and somatic genetic aberrations.

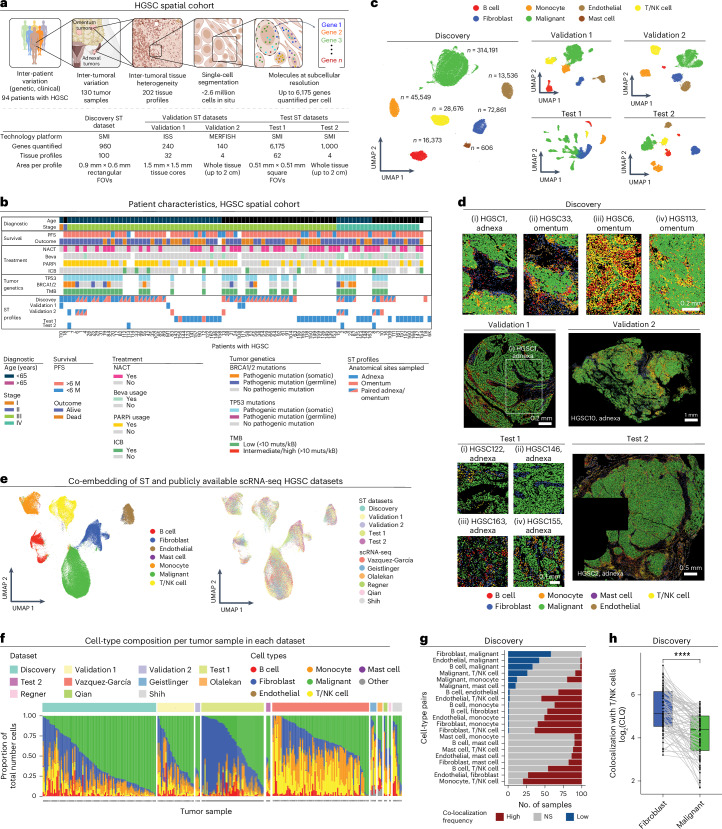

Fig. 1. Single-cell ST mapping of HGSC.

a, Cohort and data overview. Created with BioRender.com. b, Summary of clinical history, tumor genetics and ST profiles per patient. Each column represents 1 of 94 patients. NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; Beva, bevacizumab; PARPi, PARP inhibitor. c, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) embedding of high-confidence spatial single-cell transcriptomes from the different datasets. n denotes number of cells within each cell-type annotation in the Discovery dataset. d, Representative tumor tissue ST images (11 of 202) with cells plotted in situ and colored based on cell-type annotations. e, Co-embedding of spatial single-cell transcriptomes from this study with six publicly available HGSC scRNA-seq datasets17,24–29. f, Cell-type composition (y axis) per tissue profile (x axis) from this study and in six publicly available scRNA-seq HGSC datasets17,24–29. g, Pairwise colocalization analysis: the number of tissue profiles (x axis) where each pair of cell types (y axis) shows significantly (BH FDR < 0.05, hypergeometric test) higher (red), lower (blue) or expected (gray) colocalization frequencies compared to those expected by random. h, log2 colocalization quotient (CLQ) of T/NK cells with fibroblasts (CLQT/NK cell→fibroblast, blue) and T/NK cells with malignant cells (CLQT/NK cell→malignant, green, x axis) in ST tissue profiles from the Discovery dataset (n = 87 CLQ pairs, P = 4.31 × 10−10, paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Light gray lines connect paired values in each ST tissue core (black dots). In the box plots, the middle line denotes the median, box edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the most extreme points that do not exceed ±1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR); further outliers (minima and maxima) are marked individually as black points beyond the whiskers; ****P < 1 × 10−4, paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test. NS, not significant.

The spatial data were collected using three spatial transcriptomics (ST) platforms, allowing rigorous cross-platform validation of these recently developed technologies (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Table 1b). All three ST platforms used here provide detection of RNA molecules at subcellular resolution. As the spatial molecular imaging (SMI, also known as CosMx)21 platform had the largest gene panels, we used SMI to generate most of the data in this study. Data were generated with the SMI platform in two rounds (Discovery and Test; Fig. 1a). In the first round, we applied SMI to formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue microarrays (TMAs) to generate a Discovery dataset that spans 960 genes measured across 491,792 cells from 94 tumors. The discovery phase of the study was performed exclusively based on analyses of the Discovery dataset; all the spatiomolecular transcriptional programs identified in this study were derived from this dataset. In the second round, we applied SMI to another TMA from 34 additional (unseen) patients as well 4 whole-tissue sections (from patients included in the Discovery set), spanning 6,175 and 1,000 genes (Supplementary Table 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a), respectively, and a total number of 1,233,033 cells. The Test datasets were used only in the testing phase of the study to test if the key spatiomolecular findings generalize to unseen patients and larger fields of view (FOVs) within a tumor. For technical comparison and validation, in situ sequencing (ISS; via Xenium22) was applied to profile 280 genes in an FFPE TMA of 32 tissue cores, and MERFISH23 (multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (ISH)) was applied to profile 140 genes in four fresh-frozen tissue sections (Methods and Supplementary Table 1b).

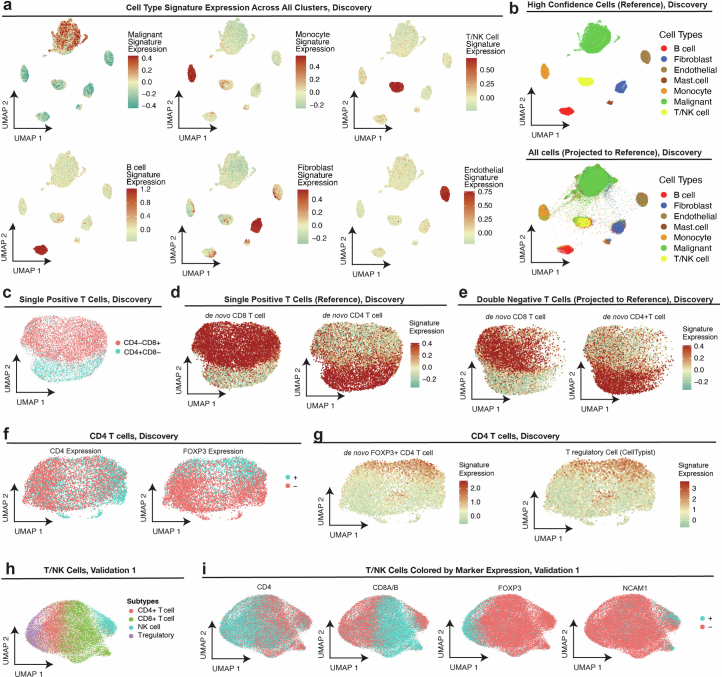

For robust data processing, we developed an analytical procedure that mitigates segmentation inaccuracies (Extended Data Fig. 1a–f and Methods) and results in robust cell-type annotation through recursive clustering of the spatial single-cell gene expression profiles (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Methods). Applying our pipeline to the Discovery dataset identified malignant cells (n = 314,191), T cells and natural killer (NK) cells (n = 28,676), B cells (n = 16,373), monocytes (n = 45,549), mast cells (n = 606), fibroblasts/stromal cells (n = 72,861) and endothelial cells (n = 13,536; Fig. 1c,d and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). The same procedure resulted in similar annotations of the Validation and Test datasets (Fig. 1c,d). T/NK cells were then further stratified to NK (n = 6,897), CD4+ T (n = 6,040), CD8+ T (n = 8,439) and regulatory T cells (Treg cells; n = 1,905) in the Discovery dataset (Extended Data Fig. 2c–g and Methods), with similar T/NK stratification results obtained in the Test and Validation 1 datasets (Extended Data Fig. 2h,i and Methods).

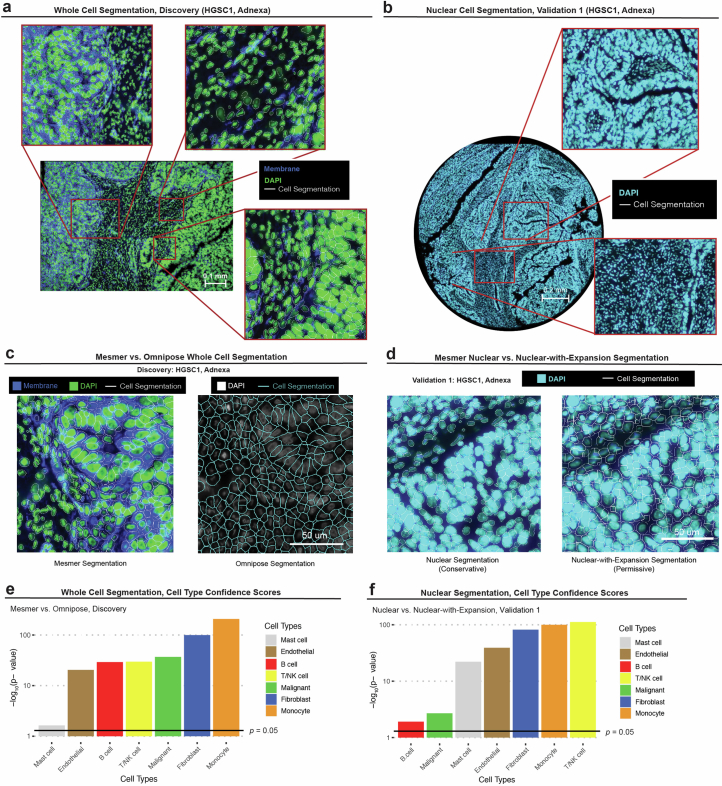

Extended Data Fig. 1. Cell segmentation.

(a) Representative whole-cell segmentation performed for the Discovery dataset. Input data includes DAPI immunofluorescent (IF) and cell membrane stain. Cell boundaries represented as white contours. This is a single representative sample out of 100. Similar results were obtained for all 100 other samples. (b) Representative nuclear segmentation performed for Validation 1 dataset. Input data includes DAPI IF stain. Cell boundaries represented as white contours. This is a single representative sample out of 32 samples. Similar results were obtained for all other samples. (c) Representative comparison of Mesmer vs. Omnipose cell segmentation in a tissue profile (1 of 100) from the Discovery dataset. (d) Representative comparison of Mesmer Nuclear (left) and Mesmer Nuclear-with-Expansion (right) segmentation in a tissue profile (1 of 32) from Validation 1 dataset. (e) P values denoting if cell type confidence scores are significantly higher (one-sided Wilcoxon sum rank test) for whole cells segmented by Mesmer vs. Omnipose for each cell type in the Discovery dataset. (f) P values denoting if cell type confidence scores are significantly higher (one-sided Wilcoxon sum rank test) in cells segmented by Mesmer Nuclear vs. Mesmer Nuclear-with-Expansion for each cell type in Validation 1 dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Cell type annotations of spatial transcriptomics.

(a) UMAP projection (matches (b) and Fig. 1c) of high confidence (Supplementary Methods) spatial single cell transcriptomes (Discovery dataset); cells colored by overall expression of pre-defined cell type signatures (Supplementary Table 3,a, Methods). (b) UMAP projection of high confidence (top panel, matches (a) and Fig. 1c) spatial single cell transcriptomes (Discovery dataset) to yield a reference map. UMAP projection of all cells in the Discovery dataset (bottom panel) onto the high confidence reference map. (c-d) UMAP embedding of single positive (that is, CD4+ or CD8+) T cell transcriptomes (Discovery dataset), cells colored by (c) CD8 and CD4 expression, and (d) expression of de novo CD8 (left) and CD4 (right) T cell expression signatures. (e) Projection of double negative T/NK cell transcriptomes (Discovery) onto CD8/CD4 T cell reference map in (b), with cells colored by overall expression of the de novo CD8 (left) and CD4 (right) T cell gene signatures (Supplementary Table 3,b). (f) UMAP embedding of CD4 T cell transcriptomes (Discovery dataset), cells colored by CD4 expression (left) and FOXP3 expression (right). (g) UMAP as in (f), with cells (Discovery dataset) colored based on de novo FOXP3+CD4 T cell gene signature expression (left) and pre-defined regulatory T cell (Treg) signature expression (Methods; Supplementary Table 3,a). (h-i) UMAP embedding T/NK single cell transcriptomes in Validation 1 dataset, cells colored by (h) final T/NK cell subtype annotations, (i) detection of (from left to right): CD4, CD8A/B, FOXP3 (regulatory T cell marker), and NCAMI (NK cell marker).

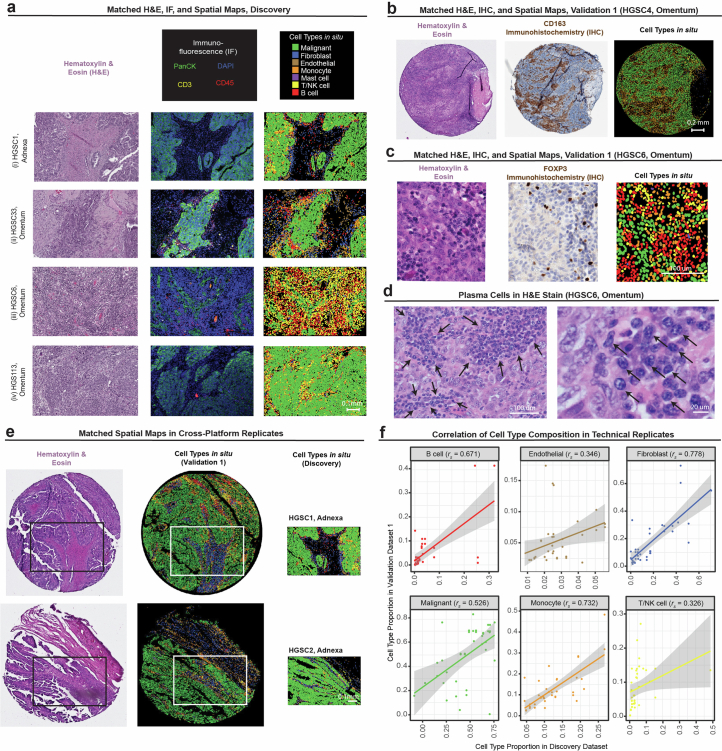

Cell-type annotations were validated in five ways. First, de novo cell-type signatures identified based on the annotated cells recapitulate well known cell-type markers (Methods, Supplementary Table 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Second, cell-type annotations are aligned with matching hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical markers (Extended Data Fig. 3a–d). Third, cell-type annotations were aligned both spatially (Extended Data Fig. 3e) and compositionally (Extended Data Fig. 3f) when examining biological and technical replicate-matched tissue samples profiled in the Discovery and Validation 1 datasets. Fourth, we generated a unified HGSC single-cell transcriptomic atlas by integrating the HGSC spatial data with six publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets17,24–29 (Fig. 1e,f and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). The unified co-embedding corroborates the cell-type annotations obtained independently based on the ST data alone (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 2a,b and Methods). Fifth, using patient-matched CNA data, we examined for each gene in each cell type whether its expression is significantly associated with its copy number in the tumor (Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (BH FDR) < 0.05, linear mixed-effects model (LMM); Methods). In malignant cells, gene expression is patient specific and the expression of 42% of the genes matches their CNAs (that is, ‘in cis’), compared to only 0–2% in the nonmalignant cell types (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The genes that do not show in cis RNA-to-CNA associations in malignant cells are significantly more copy number stable (median = 2, range = 0–7) compared to those showing the association (median = 3, range = 0–20, P = 5.04 × 10−10, one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). In contrast to CNAs, a relatively small number of genes (0–4%) are associated with clinical and other genetic covariates in malignant and nonmalignant cell types (that is, age at diagnosis, disease stage, pathogenic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutational status and TMB; Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Cross-platform ST data validations.

(a) Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining (left), Immunofluorescence (middle) of in situ cell type annotations in the Discovery dataset (right) for four representative tissue FOV (4 of 100). (b-c,e-f) cells colored according to cell type legend in (a). (b) H&E staining (left), Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain for CD163 (middle; monocyte marker) with corresponding in situ cell type annotations (right) in a representative tissue core (1 of 32) in Validation 1 dataset. (c) H&E (left), IHC stain for FOXP3 (middle, Treg marker), and corresponding in situ cell type annotations (right) in a representative tissue (1 of 32) FOV from Validation 1 dataset. (d) H&E stains of HGSC6 omentum tumor tissue (1 of 100) resolving morphology of plasma cells (black arrows) identified based on the Discovery tissue profile shown in panel (a)(iii). (e) H&E (left), in situ cell type annotations from Validation 1 dataset (middle), and Discovery dataset (right) from technical replicate pairs (2 of 39). Each dataset was processed and annotated separately. White box denotes region of tissue profiled by ISS via Xenium in the Validation 1 dataset that corresponds an adjacent region profiled by SMI in the Discovery dataset (same row). (f) Cell type proportion in technical replicates profiled both in the Discovery and Validation 1 datasets. Straight lines correspond to the linear regression fit; grey ribbons correspond to 95% confidence interval; rs denotes the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Initial analyses of the data reveal heterogeneous tumor tissue compositions across patients (Fig. 1f), yet a generalizable spatial organization at the macro level, where malignant cells and fibroblasts form spatially distinct compartments (which we refer to as the malignant and stromal compartments; Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 3a,b), such that T/NK cells preferentially localized in the stromal rather than the malignant compartment (P < 1 × 10−4, paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test; Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 3c–g and Methods). This macro-organization principle was first observed in the Discovery dataset (Fig. 1g,h and Supplementary Fig. 3c) and subsequently validated in the Validation and Test datasets (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b,d–g).

Patients with higher T/NK cell abundance had improved clinical outcomes (P = 2.03 × 10−2, univariate Cox regression, P = 2.1 × 10−4, log-rank test), demonstrating that even a relatively small area within the tumor (Supplementary Fig. 1a) is predictive of patient outcomes 5 years and even 8 years later.

T cell states reflect T cell tumor infiltration status

Using the Discovery dataset, we set out to map the immune cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic factors that mark immune infiltration and exclusion. First, taking an unbiased data-driven approach, we used unsupervised methods to embed and cluster the transcriptomes of cells from each immune cell type without any spatial information. The resulting embedding and clustering shows that immune cells residing in the malignant compartment are transcriptionally distinct from those that reside outside of it (Fig. 2a). Next, we took a spatially supervised approach and identified for each of the five immune cell subtypes robustly represented in the data a tumor infiltration program (TIP), consisting of genes that are significantly (BH FDR < 0.05, LMM; Methods) overexpressed or underexpressed in the pertaining immune cell subtype as a function of proximity to malignant cells (Fig. 2b,c, Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 4a).

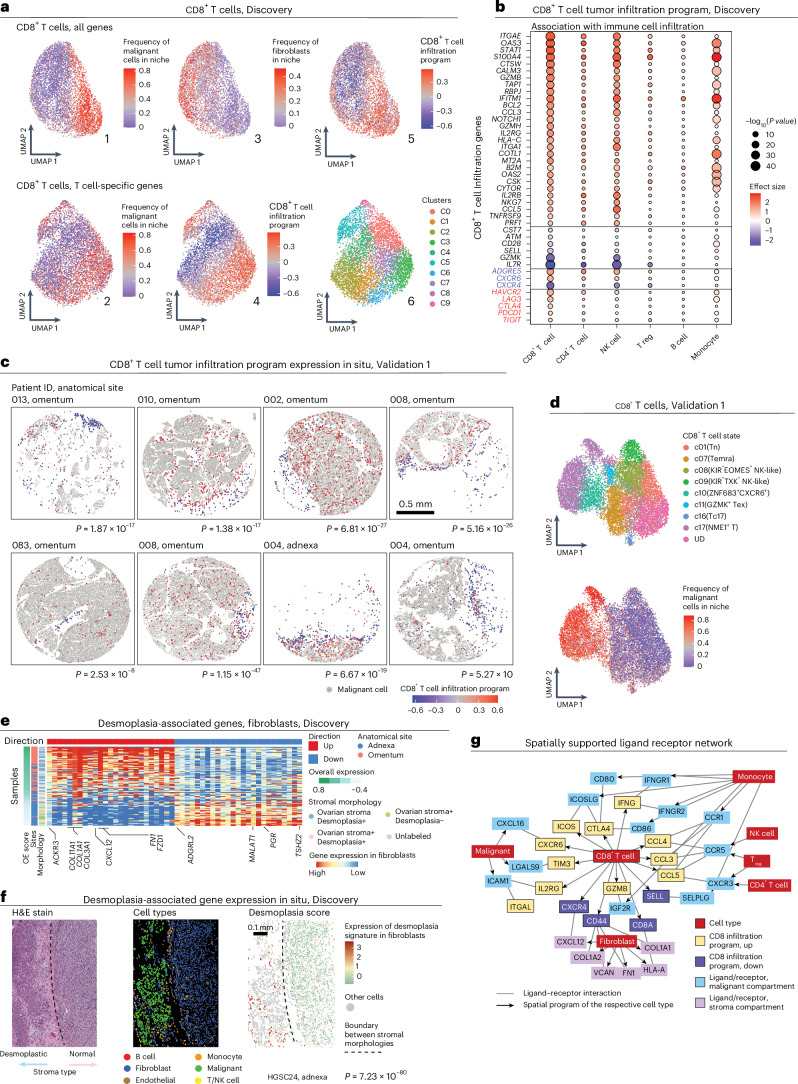

Fig. 2. Immune cell states mark immune cell tumor infiltration status.

a, UMAP embedding of CD8+ T cells (Discovery dataset) derived from gene expression of all genes (top) or only T cell-specific genes (bottom). b, The association (P value and effect size, LMM) of each gene (row) from the CD8 TIP with immune cell infiltration status, when considering CD8+ T cells and other immune cell types in the Discovery dataset (columns). c, Representative ST images from the Validation 1 dataset depicting the CD8 TIP identified in the Discovery dataset. P values denote per tissue core if the expression of the CD8 TIP is significantly higher in CD8+ T cells with a high (above median) versus low (below median) abundance of malignant cells within a radius of 30 μm (one-sided t-test). d, UMAP embedding of CD8+ T cells (Validation 1 dataset) from gene expression alone. e, Average gene expression (z score) in fibroblasts (Discovery dataset) of the top 50 desmoplasia-associated genes (columns) in each tissue profile (rows, n = 87). f, Representative tissue section (HGSC24, adnexa, Discovery dataset, 1 of 100), wherein the desmoplasia-associated genes capture stromal morphology on the per-cell level (n = 1,968 fibroblasts, P value = 7.23 × 10−80, one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These results were observed repeatedly across samples, as shown in e. g, Ligand–receptor interactions (lines) consisting of genes from the CD8 TIP and their respective ligand/receptor in the malignant compartment and stromal compartment. The arrows connect each gene to the cell type where it was found to mark the malignant or stromal compartment.

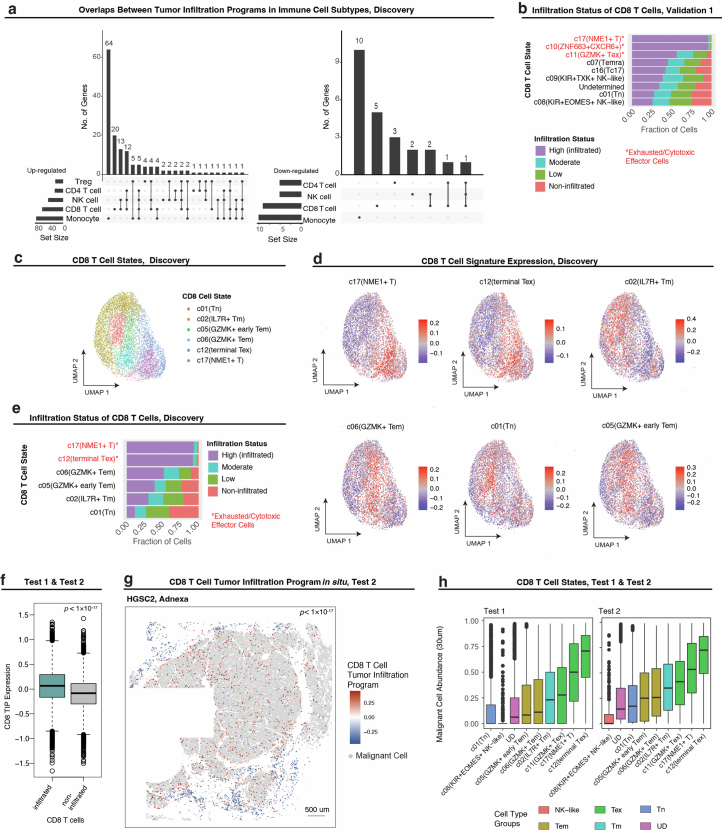

Extended Data Fig. 4. CD8 T cell states reflect CD8 T cell tumor infiltration levels.

(a) Size and overlap between the tumor infiltration programs (TIPs) identified in the Discovery dataset for the five different immune cell subsets, shown for the up-regulated (left) and down-regulated (right) subsets. (b) Stratification CD8 T cell subsets based on tumor infiltration status (Validation 1 dataset). (c-d) UMAP embedding of CD8 T cells (Discovery dataset) from gene expression only; cells colored by CD8 T cell states30 (c), overall expression of predefined CD8 T cell signatures30. (d). (e) Stratification CD8 T cell subsets based on tumor infiltration status (Discovery dataset). (f) Expression of CD8 TIP in infiltrating vs. non-infiltrating CD8 T cells (Test 1 and Test 2 datasets); p-value derived from one-sided student’s t-test. (g) CD8 TIP expression marks infiltrating CD8 T cells in the Test datasets, shown in situ for a representative whole tissue section (HGSC2, Adnexa, 1 of 4); p-value derived from one-sided student’s t-test. (h) Abundance of malignant cells in a 30um radius of CD8 T cells in Test datasets, stratified by CD8 T cell subset.

CD8+ T cell TIP (CD8 TIP) demonstrates that effector and exhausted CD8+ T cells more frequently colocalize with malignant cells (P = 3.24 × 10−53, LMM; Fig. 2b,c), as also confirmed by annotating CD8+ T cells based on predefined signatures30 (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 4b–e). CD8 TIP upregulated genes include effector cytotoxicity genes as granzymes (GZMA, GZMB and GZMH) and perforin (PRF1), chemokines (CCL3, CCL4, CCL4L2 and CCL5), interferon gamma (IFN-γ; encoded by IFNG), interferon signaling genes (for example, IFITM1, IFNG, JAK1 and STAT1) and immune checkpoints (CTLA4, HAVCR2, PDCD1, TIGIT and LAG3), as well as KLRB1 (that is, CD161) and CXCR6, which have been previously reported to suppress31 or sustain32–34 the cytotoxic function of exhausted CD8+ T cells, respectively. CD8 TIP downregulated genes include naive and memory T cell markers (SELL, IL7R and CD44), the co-stimulatory gene CD28, the granzyme encoded by GZMK and the chemokine receptor encoded by CXCR4 (Fig. 2b). Extending CD8 TIP to the whole-transcriptome level based on scRNA-seq data17 (Methods and Supplementary Table 4b,c) revealed the upregulation of other exhaustion-associated genes30,35 (that is, ENTPD1, BST2, CD63, MIR155HG, MYO7A and NDFIP2), and downregulation of additional naive T cell markers (for example, CCR7, TCF7, SATB1 and KLF2), with MALAT1, KLF2, CCR7, GPR183 and TCF7 being the topmost downregulated genes in the extended CD8 TIP (P < 1 × 10−16, rs > 0.23, Spearman correlation).

Testing these findings in the Test datasets, the CD8 TIP identified in the Discovery dataset was validated as an infiltration marker both in unseen patients and in whole-tissue sections (P = 4.22 × 10−3 and P < 1 × 10−17, LMM, Test datasets 1 and 2, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 4f,g), and exhausted and effector CD8+ T cell subsets were enriched in proximity to malignant cells (P = 1.09 × 10−5 and P < 1 × 10−17, hypergeometric tests, for Test datasets 1 and 2, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 4h).

CD8 TIP is not associated with age at diagnosis, disease stage (III or IV), pathogenic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations, or TMB, but does show lower expression levels in samples after neoadjuvant treatment (P < 4.42 × 10−3, LMM, also when controlling for malignant cell abundance).

To investigate the role of the stroma in preferentially colocalizing with naive and memory T cells compared to effector and exhausted T cells, we integrated the ST data with sample-matched H&E stains independently annotated by a gynecologic pathologist (Supplementary Fig. 5a–e), revealing two fibroblast subsets, one marking normal stroma and the other marking desmoplasia (that is, a neoplasia-associated alteration in fibroblasts and extracellular matrix with distinct tissue morphology36–40; Fig. 2e,f, Supplementary Fig. 5a–g and Supplementary Table 5a). As expected41,42, desmoplastic fibroblasts not only overexpress collagen fibril organization and extracellular matrix genes (P < 1 × 10−2, permutation test; Supplementary Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 5b), but also upregulate CXCL12 (the cognate ligand of CXCR4; Fig. 2e) and were associated with niches enriched with T/NK cells (P < 1 × 10−4, LMM).

To link these findings to paracrine signaling, we compiled 2,678 ligand–receptor pairs based on three public resources43–45 (Supplementary Table 5c and Methods). Focusing on CD8+ T cells, we identified 24 ligand–receptor pairs that mark the interactions of CD8+ T cells with other cells in the malignant or stromal compartment (Methods). The resulting network (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 5d) manifests suppressive ligand–receptor interactions in the malignant compartment (for example, CD80/CD86–CTLA4, CD8+ T cell–monocyte; TIM3–LAGLS9, CD8+ T cell–malignant cell) and CD8+ T cell-mediated chemoattraction of other immune cells via CCL2 and CCL5. Colocalization of CXCR6–CXCL16 (CD8+ T cell–malignant cell) and CXCR4–CXCL12 (CD8+ T cell–fibroblasts) mark chemoattraction of infiltrating and stroma-residing CD8+ T cells, respectively (Fig. 2g; BH FDR < 1 × 10−10, LMM; Supplementary Fig. 5j–l). Of note, TCF1 (encoded by TCF7 and downregulated in the extended CD8 TIP) has been shown to directly repress CXCR6 expression34 (upregulated in the CD8 TIP), suggesting that this central regulator of naive and resting T cells46 represses CD8+ T cell chemoattraction to CXCL16 expressed by the malignant cells.

A malignant cell state marks and predicts T/NK cell abundance

Mapping the spatial distributions of T/NK cells within the malignant compartment revealed that TILs preferentially colocalize with a subset of malignant cells (Methods, Fig. 3a–c, Extended Data Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 6a). Although malignant cell states are highly patient specific (Supplementary Fig. 4b) and vary also within patients (Supplementary Fig. 4c–f), we found that the connection between TIL location and malignant cell gene expression appeared repeatedly across the heterogeneous tumors in our cohort and external cohorts (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6).

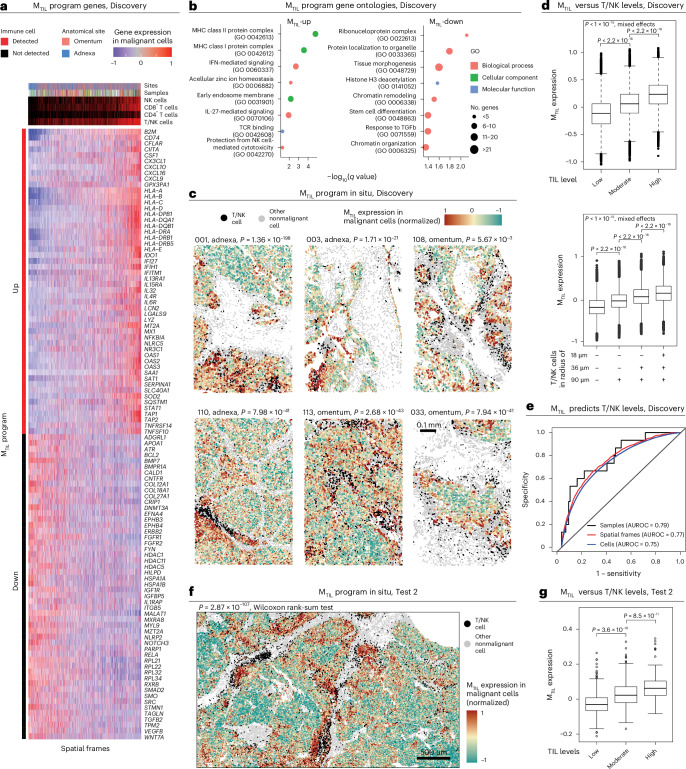

Fig. 3. Malignant cell transcriptional program marks and predicts T/NK cell infiltration.

a, Heat map of genes in the MTIL (malignant transcriptional program that robustly marks the presence of TILs) program (Discovery dataset). Average expression of the top 104 MTIL genes (rows) across spatial frames (columns). b, Top gene sets enriched in MTIL based on Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. c, MTIL spatial distributions in six representative tumor tissue profiles (6 of 100, Discovery dataset). P values denote if MTIL expression is significantly (one-sided t-test) higher in frames with high-versus-low T/NK abundance, defined based on the median level in the respective tissue section. Matching cumulative analysis is provided in Extended Data Fig. 5e. d, MTIL expression in each malignant cell (Discovery dataset, n = 297,960 cells), stratified based on the relative abundance of T/NK cells in their surroundings (top) and the presence of T/NK cells at different distances (bottom). e, ROC curves obtained for cross-validated SVM classifier using MTIL expression in malignant cells (Discovery dataset) to predict T/NK cell levels, at the sample, spatial frame and single-cell levels. f, MTIL spatial distributions in a representative region from one (of four) whole-tissue section (HGSC1, adnexa, Test 2 dataset; MTIL expression in TIL-high versus TIL-low niches, P = 2.87 × 10−107, one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). A full view of the whole-tissue section is provided in Extended Data Fig. 6g. g, Mean MTIL expression in malignant cells in each FOV (Test 2 dataset, n = 878 FOVs), stratified based on the relative abundance of T/NK cells in each FOV. In d and g, in the box plots, the middle line denotes the median, box edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the most extreme points that do not exceed ±1.5 times the IQR; further outliers are marked individually with circles (minima/maxima). P values of group comparisons are derived from a one-sided Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. MTIL marks T/NK infiltration at micro- and macro-scales.

(a) Statistical significance and effect size showing the association of each gene’s expression in malignant cells with T/NK cell levels, quantified via mixed effect models (two-sided) applied to the Discovery dataset (Methods). (b-d) In the Discovery dataset: MTIL expression in malignant cells as a function of (b) discretized T/NK cell levels across tissue profiles (n = 99 profiles, top) and spatial frames (n = 6699 frames, bottom), (c) T/NK cell levels in spatial frames (n = 6699 frames) across anatomical sites, (d) presence of T/NK cell subtypes in spatial frames (n = 6699 frames): CD4 T cells (left), CD8 T cells (middle), and NK cells (right); p-values derived from one-sided student’s t-test. (e) Cumulative probability analysis of fraction of T/NK cells in spatial frames stratified by MTIL expression in 6 representative tissue profiles (Discovery dataset) shown in Fig. 3c. In (b-d) Boxplots middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ± IQR x 1.5; further outliers are marked individually with circles (minima/maxima).

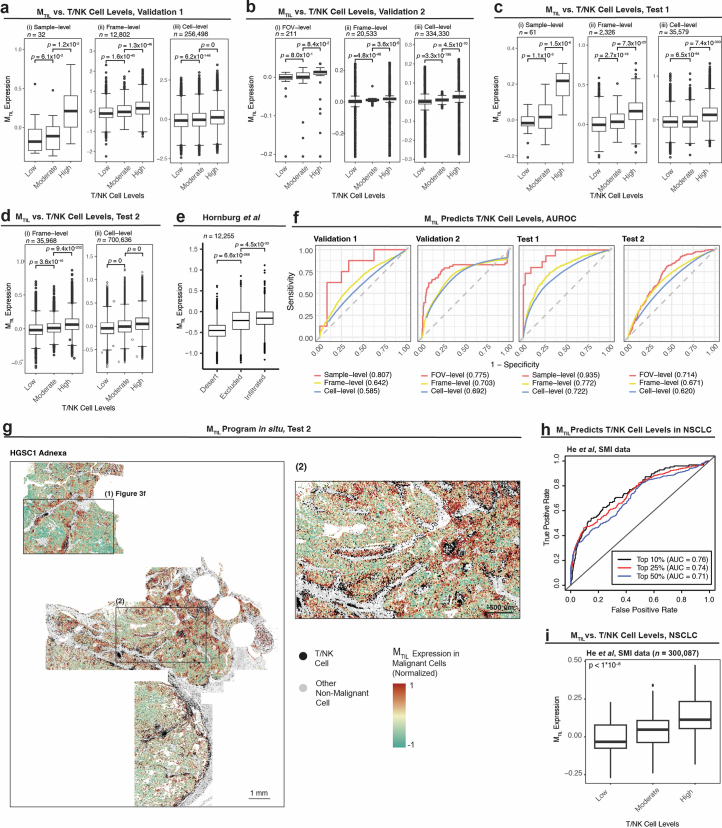

Extended Data Fig. 6. MTIL is predictive of T/NK infiltration.

(a-d) MTIL expression in malignant cells, stratified by discretized TIL levels in a malignant cell’s niche in (a) Validation 1 dataset, (b) Validation 2 dataset, (c) Test 1 dataset, and (d) Test 2 dataset. (e) MTIL expression in malignant cells, stratified by tissue immune subtyping in Hornburg et al scRNA-seq study47. In (a-e) p-value derived from one-sided t-tests. (f) MTIL expression in malignant cells as a predictor of T/NK cell levels. Predictive performances are quantified and visualized via the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves shown per ST dataset. Area under the ROC (AUROC) curve is reported in parentheses. (g) In situ MTIL expression marks T/NK cell levels shown in a representative whole tissue section (HGSC1, Adnexa, Test 2 dataset; MTIL expression is higher in TIL-high versus TIL-low niches, p = 2.87 × 10−107, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). A magnified version of region (1) is shown in Fig. 3f, region (2) is magnified in the right image. (h-i) MTIL predicts T/NK cell levels at the microenvironment level in an independent ST SMI data from NSCLC21. (h) ROCs depicting prediction performances in NSCLC when predicting the top 10%, 25%, and 50% most T/NK cell rich frames based on the MTIL expression in malignant cells. (i) MTIL expression in NSCLC malignant cells stratified by the level of T/NK cells in their vicinity (‘high’ and ‘low’ depict the top and bottom quartiles, respectively, and ‘moderate’ otherwise). p-value derived from one-sided mixed effect tests. In (a-e, i) boxplots middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ± IQR x 1.5; further outliers are marked individually with circles (minima/maxima).

Formulating these findings, we used the Discovery dataset to identify a malignant transcriptional program that robustly marks the presence of TILs, abbreviated as the malignant TIL (MTIL) program (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Table 6a). The program consists of 100 upregulated and 100 downregulated genes whose expression in malignant cells is significantly (BH FDR < 0.05, LMM) positively (MTIL-up) and negatively (MTIL-down) correlated with and predictive of T/NK cell infiltration (Fig. 3d,e). MTIL overall expression in malignant cells (Methods) reflects both inter-sample and intra-sample variation in T/NK cell levels (Fig. 3d, e), irrespective of anatomical site (P < 1 × 10−30, LMM; Extended Data Fig. 5c). MTIL continuously increases as a function of T/NK cell abundance and proximity, also when stratifying the T/NK population into its respective cell subtypes (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e). MTIL is associated and predictive of T/NK cell levels both in the Validation (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b,f) and Test datasets, generalizing to unseen patients (Extended Data Fig. 6c,f) and whole-tissue sections (Fig. 3f,g, Extended Data Fig. 6d,f,g and Supplementary Fig. 6). Likewise, an independent scRNA-seq dataset47 demonstrates that MTIL expression in malignant cells is highest in tumors annotated as ‘infiltrated’, moderate in tumors annotated as ‘excluded’ and lowest in tumors annotated as ‘immune desert’ (Extended Data Fig. 6e).

Gene-set enrichment analyses demonstrate the connection between MTIL and immune evasion48–53. MTIL-up includes chemokines (for example, CCL5, CXCL10, CXCL9 and CXCL16 the cognate ligand to CXCR6), and oxidative stress genes (for example, GPX3 and SOD2; Fig. 3a,b), and is enriched with multiple immune response genes, including antigen presentation (for example, B2M, CIITA and HLA-A/HLA-B/HLA-C), interferon gamma response genes (for example, IDO1, IFI27, IFIH1, OAS1/OAS2/OAS3, JAK1 and STAT1) and cell adhesion molecules (for example, ICAM1, ITGAV and ITGB2; BH FDR = 1.91 × 10−9, 2.86 × 10−10, 4.59 × 10−2, respectively, hypergeometric test; Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 6b). MTIL-up also includes immune suppression genes, most notable is LGALS9, encoding galectin 9—the ligand of the immune checkpoint TIM3 (that is, HAVCR2), which is upregulated in the infiltrating T/NK cells (Fig. 2g). However, there is no significant correlation between MTIL and the expression of exhaustion signatures in the nearby T cells (rs < 0.046, P > 0.05, Spearman correlation, Discovery dataset; Supplementary Table 6c). MTIL-down reflects diverse processes including Wnt signaling (for example, CTNNB1, FZD3/FZD4/FZD6, SMO, FGFR2 and WNT7A), epigenetic regulation (DNMT3A and HDAC1/HDAC11/HDAC4/HDAC5), insulin signaling (for example, IGFR1 and IGFBP5) and cell differentiation (for example, BMP7, BMPR1A, ETV4, FGFR1/FGFR2, FYN, S100A4, SMAD4 and SMO; BH FDR < 0.05, hypergeometric test; Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 6b). Comparing the MTIL program to 13 malignant signatures previously identified in a comprehensive HGSC scRNA-seq study17, we found that 156 of the 200 genes in the MTIL program were not included in any of these signatures (Supplementary Table 6d).

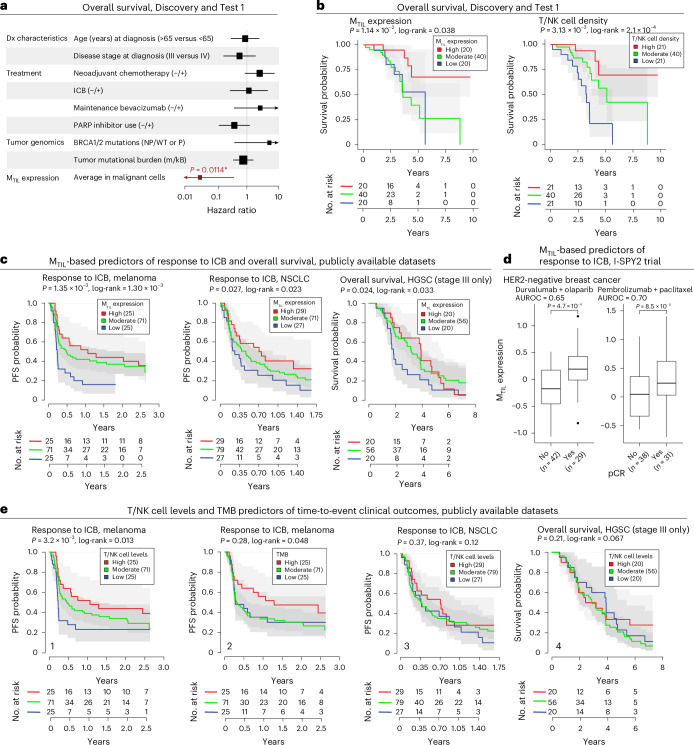

In our cohort, MTIL expression is not associated with patient age at diagnosis, disease stage, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, TMB or sample anatomical site (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 7a–c), but it is moderately positively associated with pathogenic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations (P = 0.0423, LMM). MTIL expression is associated with improved overall survival, both in our cohort (n = 54, P = 0.011, Cox regression, based on mean expression of malignant cells in adnexal tumors, while controlling for age at diagnosis, disease stage and treatment history; Fig. 4a,b, Supplementary Table 8a–d and Methods), and in an external HGSC cohort (n = 111, P = 0.024, Cox regression, controlling for patient age and stage; Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. MTIL predicts patient survival and ICB response.

a, Hazard ratios (HRs) estimated for each predictor from multivariate Cox proportional hazards models of overall survival in the HGSC cohort of this study (Discovery and Test 1 datasets, n = 30 and 54 patients for genomic and non-genomic features, respectively). Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (Methods). Arrowheads indicate that the 95% interval extends beyond the HR limits shown in the x axis. *P value < 0.05, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. b, Kaplan–Meier curves and numbers-at-risk table of overall survival in patients with HGSC (Discovery and Test 1 datasets); patients stratified by average MTIL expression (left), and T/NK cell density (right) in adnexal tumors. c, Kaplan–Meier curves and numbers-at-risk tables of ICB PFS probability (melanoma56, left; NSCLC57, middle) and overall survival (external HGSC cohort, right) with patients stratified by tumor MTIL expression. d, MTIL expression is significantly higher in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer with pCR (pathogenic clinical response) versus without pCR in two arms of the I-SPY2 clinical trial (durvalumab + olaparib (n = 71 patients)58 and pembrolizumab + paclitaxel (n = 67 patients)59). In the box plots, the middle line denotes the median, box edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the most extreme points that do not exceed ±1.5 times the IQR; further outliers are marked individually (minima/maxima). P values derived from one-sided Student’s t-test. e, T/NK cell levels estimated from bulk transcriptomics and TMB (mut/kB) as predictors of ICB responses in the datasets shown in c. Kaplan–Meier curves and numbers-at-risk tables of ICB PFS probability in patients with melanoma56 stratified by T/NK cell levels (1) and TMB (2), and in patients with NSCLC57 stratified by T/NK cell levels (3), and of overall survival in patients with HGSC stratified by T/NK cell levels (4). In b, c and e, P values were calculated from the Wald statistic of covariate-controlled Cox proportional hazards regression models. The log-rank P value was derived from comparing discretized predictors (high = top quartile versus low = bottom quartile).

Testifying to its generalizability, MTIL expression in malignant cells is predictive of T/NK cells in the vicinity of the malignant cells also in a previously published SMI dataset collected from five patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)21 (area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve > 0.71; Extended Data Fig. 6h,i). Likewise, MTIL expression was significantly correlated with the expression of a T/NK cell signature in external bulk gene expression datasets, both in HGSC (n = 578, rs = 0.72, P < 2.2 × 10−16, Spearman correlation) and other cancer types (rs > 0.66, P < 1 × 10−9, Spearman correlation; Supplementary Fig. 8a). However, although MTIL is strongly supported by bulk gene expression data as a marker of T/NK cell levels, attempting to rediscover the MTIL signature based on the covariation structure of HGSC bulk gene expression data across patients resulted in poor performances (area under the precision recall curve (AUPRC) of 0.202 and 0.306 for the prediction of MTIL-up and MTIL-down genes, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 8b), underscoring the need for single-cell ST studies.

To expand beyond the 960-gene panel in the Discovery dataset, we identified 200 additional genes that were significantly coexpressed with the MTIL program based on the Test 1 dataset (Supplementary Table 6e and Methods), and among these are RUNX1, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-encoding genes (CEBPB and CEBPD, which encode for subunits of the RUNX1 co-activation complex54,55), and complement genes (C1S and C3) as a part of the extended MTIL-up module, as well as the stem cell marker encoded by LGR5, and the BAF complex subunit encoded by SMARCB4, as a part of the extended MTIL-down module.

MTIL expression predicts clinical response to ICB

We hypothesized that higher MTIL expression may represent more immunogenic malignant cell states and could thus be predictive of clinical responses to ICB in HGSC and potentially other cancer types. As genomic datasets from ICB trials are currently not available in HGSC and given the generalizability of the MTIL program to other cancer types (Extended Data Fig. 6h,i and Supplementary Fig. 8a), we tested this hypothesis in five external bulk gene expression datasets obtained from tumor samples of other cancer types before ICB treatment.

The MTIL program overall expression scores (Methods) were predictive of ICB response in four of the five cohorts that we tested. MTIL scores were predictive of ICB responses in the melanoma cohort56 (n = 152, P = 1.35 × 10−3, progression-free survival (PFS) Cox regression, controlling for patient sex, treatment status, TMB and anatomical site; patient age was not available, Fig. 4c), NSCLC cohort57 (n = 121, P = 0.027, PFS Cox regression model, controlling for patient sex, age, smoking status and tumor histological type; Fig. 4c) and in two independent arms of the I-SPY2 trial in HER2-negative breast cancer58,59 (durvalumab/olaparib, n = 71, P = 2.52 × 10−4, one-sided t-test, AUROC = 0.65, and pembrolizumab/paclitaxel: n = 69, P = 6.37 × 10−3, one-sided t-test; AUROC = 0.70; Fig. 4d). In the urothelial cancer cohort60, MTIL program scores and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) levels were not predictive of clinical responses (n = 205, P > 0.05, one-sided t-test). Collectively, MTIL predictive performances were comparable and, in several cases, superior to those of other ICB response biomarkers, including PD-L1 gene expression, TMB levels and estimates of TIL levels (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 8c).

Lastly, we note that MTIL is not associated with TMB based on our data (rs = −0.077, P = 0.67, Spearman correlation), as well as the melanoma and urothelial ICB cohorts, where TMB information was available (rs < 0.09, P > 0.32, Spearman correlation). These findings suggest that MTIL is an orthogonal property that is not directly linked to TMB but is predictive of ICB response in several cancer types.

MTIL expression and T/NK cell abundance in the tumor as a function of CNAs

A key question is whether MTIL is merely reflecting the response of malignant cells to the presence of TILs and is thus a surrogate marker of TILs, or whether MTIL is regulated by other cell-intrinsic processes and is driving TIL infiltration and potentially also malignant cell susceptibility to TIL-mediated cytotoxicity, making it a causal predictive biomarker of ICB responses. Given the strong connection we observed between CNAs and malignant cell transcriptomes (Supplementary Fig. 4a), we turned to examine the connection between MTIL expression and CNAs to probe at this question.

First, we note that MTIL inter-patient variation supersedes its intra-tumoral variation, as observed also after regressing out the impact of the tumor microenvironment compositions, or when considering only malignant cells in TIL-deprived environments (Fig. 5a; P < 1 × 10−30, analysis of variance (ANOVA) test). Moreover, when considering only malignant cells that are in TIL-deprived niches in the tumor, the MTIL score is still predictive of whether the entire tumor tissue core has high/low TIL levels (AUROC = 0.76, 0.89 and 0.83, when predicting which samples have TIL levels above the median, and 75th and 85th percentiles).

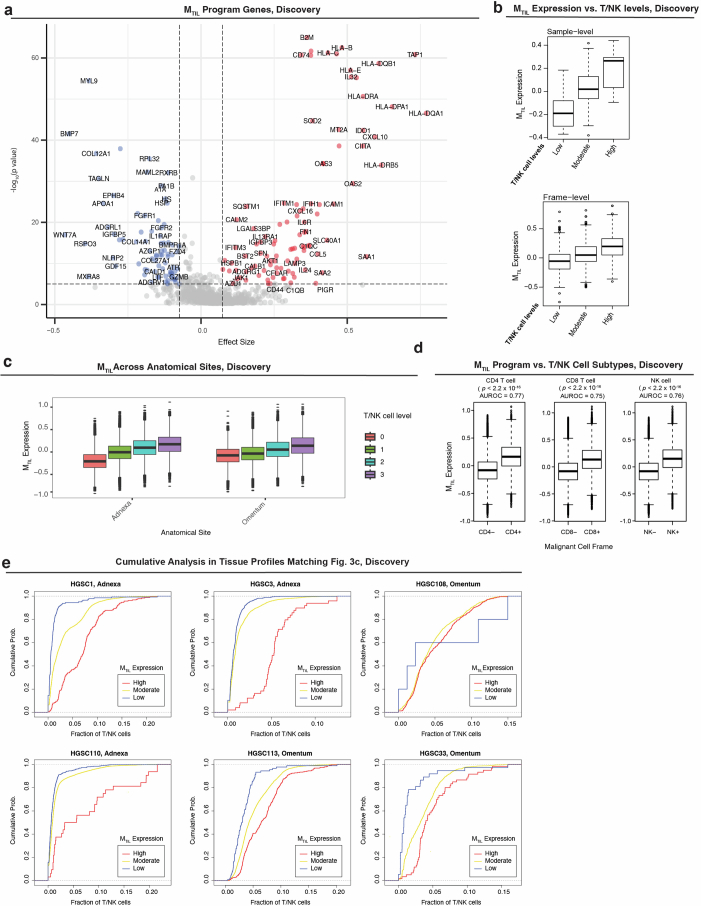

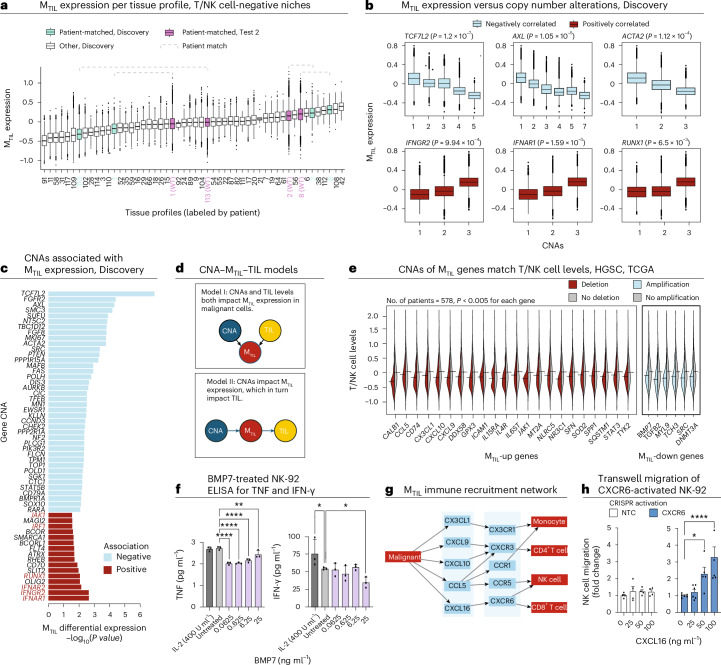

Fig. 5. Genetic association with MTIL and T/NK cell levels.

a, MTIL expression in adnexal malignant cells (Discovery and Test 2 datasets, n = 264,825 cells) residing in tissue niches where T/NK cells were not detected, stratified by tissue profiles labeled by patient and dataset. Dashed brackets indicate adnexal malignant cells from patient-matched tissue profiles from Discovery and Test 2. b, MTIL expression in malignant cells (Discovery dataset), stratified by somatic copy number of six respective genes based on patient-matched bulk tumor genomic profile (LMM, n = 40 patients). c, Top CNAs showing a significant (BH FDR < 0.05, LMM; Methods) association with MTIL expression in malignant cells in the Discovery dataset. d, CNA–MTIL–TIL models. e, Deletion (red) of MTIL-up genes and amplification (light blue) of MTIL-down genes that are significantly (BH FDR < 0.05, one side t-test) associated with low T/NK cell levels (estimated based on gene expression of T/NK cell signatures; Methods) in an independent TCGA HGSC cohort of 578 patients12. Exact P values are provided in Supplementary Table 9a. f, ELISA quantification of IFN-γ (1:100) and TNF (undiluted) in NK-92 supernatant treated with various concentrations of recombinant human BMP7. g, MTIL chemokines and the matching chemokine receptors in immune cell TIPs. h, Fold change of NK-92 cell migration of CXCR6+ NK-92 cells derived via CRISPR activation (Supplementary Fig. 9) versus control NK-92 cells (transduced with non-targeting control CRISPR activation guides, left) at varying CXCL16 concentrations. In the box plots in a and b, the middle line denotes the median, box edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the most extreme points that do not exceed ±1.5 times the IQR; further outliers are marked individually with circles (minima/maxima). In f and h, error bars represent the mean ± s.d. for f and mean ± s.e.m. for h; comparisons are indicated via brackets; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (ordinary one-way ANOVA); brackets that are not shown denote nonsignificant (P > 0.05) comparisons. Data from n = 3 biological replicates were collected per condition in f and n = 4 technical replicates were collected per condition in h.

Second, in addition to RNA–CNA associations in cis (Supplementary Fig. 4a), MTIL expression strongly correlated with the copy number of multiple genes in our cohort (Methods). Among the positively correlated ones are interferon receptors IFNGR2, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, as well as interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and RUNX1, and the top negatively correlated ones being TCF7L2, FGFR2 and AXL (P < 5 × 10−3, LMM; Fig. 5b,c).

Third, CNAs of MTIL genes are predictive of TIL abundance scores in an independent cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) of 578 HGSC tumors12 (AUROC = 0.82, on unseen test samples, support vector machine (SVM) model; Methods), such that tumors with amplification of MTIL-down genes (for example, BMP7, DNMT3A, FZD3, MYL9, SRC and TGFB2) or deletion of MTIL-up genes—including both chemokines (CX3CL1, CXCL10, CXCL9, CXCL16 and CCL5) and other genes (for example, ICAM1, GPX3 and NR3C1)—have significantly lower TIL abundance scores compared to tumors without these copy number changes (BH FDR < 5.0 × 10−3, one-sided t-test; Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary Table 9a).

Mechanistically, the composite effect of CNAs (or other forms of genetic/epigenetic aberrations) in MTIL genes and regulators can lead to immune evasion through diverse mechanisms. To demonstrate this, we show that BMP7—one of the topmost repressed genes in the MTIL program (Extended Data Fig. 5a) that is amplified in TIL-deprived HGSC tumors (Fig. 5e)—suppresses IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) secretion in NK-92 cells (Fig. 5f). Likewise, MTIL chemokines whose deletion was associated with low TIL levels in the TCGA data (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL16, CCL5 and CX3CL1; Fig. 5e) recruited different subsets of TILs and other immune cells based on ligand–receptor colocalization analyses in the HGSC spatial data (Fig. 5g). To functionally demonstrate this, we activated CXCR6 in NK-92 cells via CRISPR–dCas9 activation (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 9a,b) and showed a dose-dependent and CXCR6-dependent NK cell directional migration toward CXCL16 (Fig. 5h).

MTIL sensitizes cancer cells to T/NK cell cytotoxicity

Given our findings and previous studies where genes and pathways represented in the MTIL program have been shown to have an important function in antitumor immune responses61–64, we hypothesized that MTIL reflects not only the response of malignant cells to TILs, but also an intrinsically regulated malignant cell state that impacts TIL-mediated tumor control. Supporting this hypothesis, a collection of previously published CRISPR screens48–52 shows that MTIL-up is enriched with genes that sensitize cancer cells to immune-mediated selection pressures (including ICAM1, JAK1, NLRC5, SOD2 and STAT1; P = 1.82 × 10−4, hypergeometric test), while MTIL-down includes genes with desensitizing effects (BCL2, FGFR1, HDAC1, HDAC5, ITGB5 and RELA).

To functionally probe the MTIL program genes and examine their effect on ovarian cancer cell response to lymphocyte cytotoxicity, we performed high-content CRISPR knockout (KO) screens in ovarian cancer cells in monoculture and two types of co-cultures with cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), including one co-culture with T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-engineered CD8+ T cells and another co-culture with NK cells.

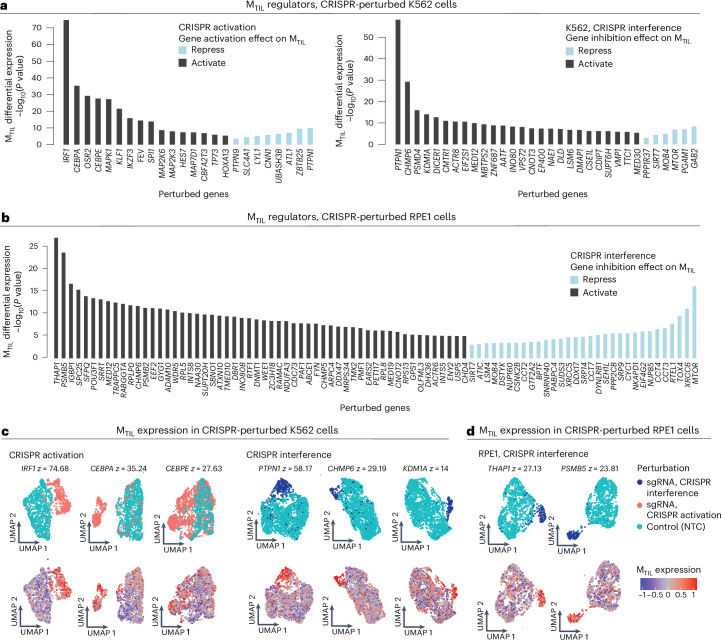

Instead of targeting only genes in the MTIL program itself, we devised a meta-analysis pipeline to identify program regulators based on available Perturb-seq datasets (Methods). Using three previously published Perturb-seq datasets65–67 (Supplementary Fig. 10a), we identified 43 and 104 perturbations that result in significantly higher and lower expression of the program, respectively (Fig. 6a–d, Supplementary Fig. 10b,c, Supplementary Table 10a and Methods). Demonstrating the value of this approach, it revealed a wider and more diverse set of regulators, most of which are not included in the MTIL program itself or not included in the gene panel of the Discovery dataset (Supplementary Table 1b). The positive regulators are enriched (BH FDR < 0.05, hypergeometric test) for genes involved in telomere maintenance (for example, CCT3/CCT4/CCT7, RTEL1), transcriptional regulators (for example, DDX17, IKZF3, KLF1, MTOR, SIRT7, TP73 and XRCC6), protein metabolism (for example, CYC1, SRP14 and SRP9) and cytokine signaling (for example, IRF1, NUP85 and SEH1L). The positive MTIL regulators also include the RUNX1 complex genes (CBFA2T3, CEBPA and CEBPE), aligned with our findings that CNAs of RUNX1 are positively associated with the MTIL program (Fig. 5c) and that RUNX1 is a part of the extended MTIL program. Negative MTIL regulators are enriched for chromatin organization (for example, DNMT1, INO80, TAF10 and WDR5), Wnt pathway, Myc targets and immune resistance genes48–52,68 (BH FDR < 1 × 10−3, hypergeometric test). The top negative regulator identified here is PTPN1, which is supported by both gene activation and inhibition screens (Fig. 6a,c).

Fig. 6. Meta-analyses of Perturb-seq datasets identify regulators of the MTIL program.

a,b, Differential MTIL expression (two-sided t-test comparing cells with the respective perturbation to cells with control sgRNAs) for MTIL altering perturbations identified in K562 (myelogenous leukemia) (a) and RPE1 (human retinal pigment epithelial) (b) cell lines Perturb-seq data65,66. c,d, Representative UMAP embeddings of MTIL altering perturbation: cells were labeled based on the sgRNA detected (top) and based on MTIL expression (bottom) in K562 (c) and RPE1 (d) cell lines. z denotes −log10(P value), two-sided t-test, comparing MTIL expression in the perturbed versus control cells.

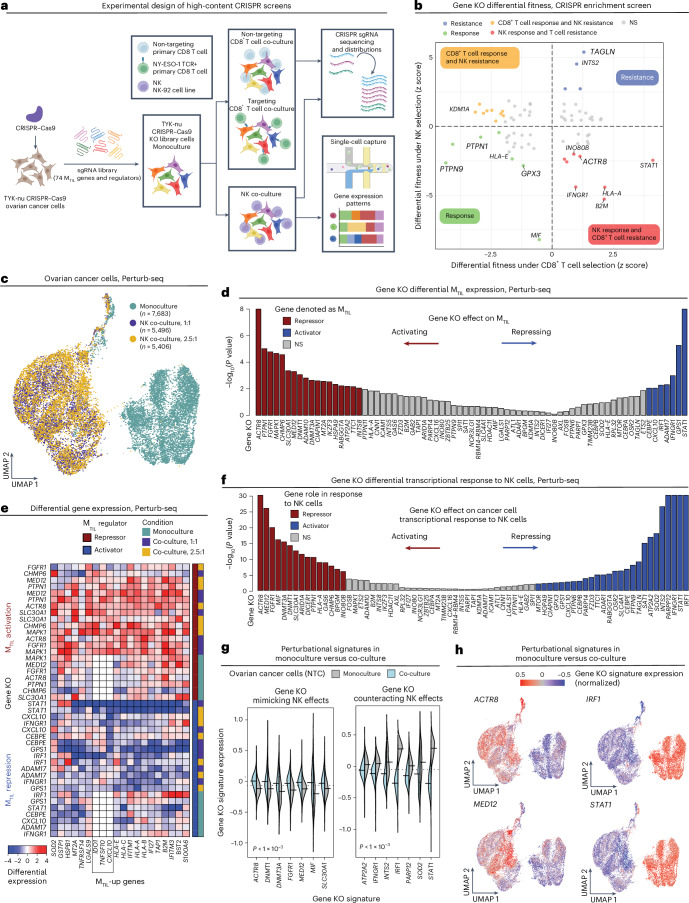

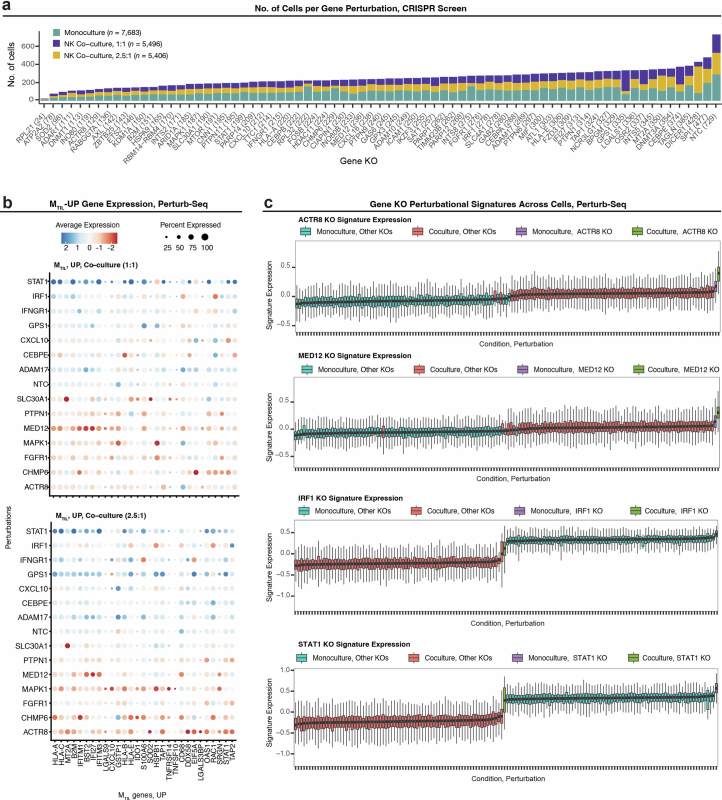

Based on these findings, we designed a pooled knockout screen of 74 MTIL genes and regulators (Supplementary Table 10a,b) to test their function in ovarian cancer cells (TYK-nu cell line; Fig. 7a and Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8). Mapping fitness upon genetic perturbations under both adaptive and innate immune selection pressures (Fig. 7a,b; BH FDR < 0.05, MAGeCK; Methods) along with Perturb-seq scRNA-seq readouts in monoculture and co-culture with NK cells (Fig. 7a,c), we identified perturbations that activate or repress the program and tracked subsequent effects of these perturbations on immune escape. In total, we profiled 18,585 high-quality single-cell transcriptomes, each assigned to an ovarian cancer cell with a single guide RNA (sgRNA) confidently identified, and a median of 4,251 genes detected per cell (Fig. 7c and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Differentially expressed genes were identified for each gene knockout across the three conditions (Fisher’s method; Methods), resulting in 74 gene ‘perturbation signatures’ (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 9b,c) that were then used to identify gene knockouts that significantly repressed or activated the MTIL program, denoted as ‘activators’ and ‘repressors’, respectively (Fig. 7d and Methods).

Fig. 7. High-content CRISPR screens identify perturbations that de-repress or repress MTIL.

a, Overview of experimental design. Created with BioRender.com. b, Ovarian cancer cell (TYK-nu) differential fitness (MAGeCK82) under CD8+ T cell and NK cell selection pressures. c, UMAP of scRNA-seq profiles from Perturb-seq screen. Each dot corresponds to an ovarian cancer cell (TYK-nu) with 1 of the 232 guides confidently detected, cultured in monoculture or co-culture with NK cells at a 1:1 or a 2.5:1 effector-to-target ratio. d, Differential expression of MTIL genes (Fisher’s combined test; Methods) when comparing ovarian cancer cells with the respective gene KO to those with NTC sgRNAs. e, Differential expression of MTIL-up genes upon different gene KOs under different conditions, shown for genes identified as MTIL repressors or activators. f–h, Gene KOs alter the cancer cell transcriptional response to NK cells. f, Differential expression of the gene KO signature in control ovarian cancer cells in monoculture versus co-culture (two-sided t-test). g, Gene KO signature expression in control ovarian cancer cells in monoculture versus co-culture; statistical significance per KO shown in f. h, UMAPs as in c with cells colored according to differential gene KO signature expression.

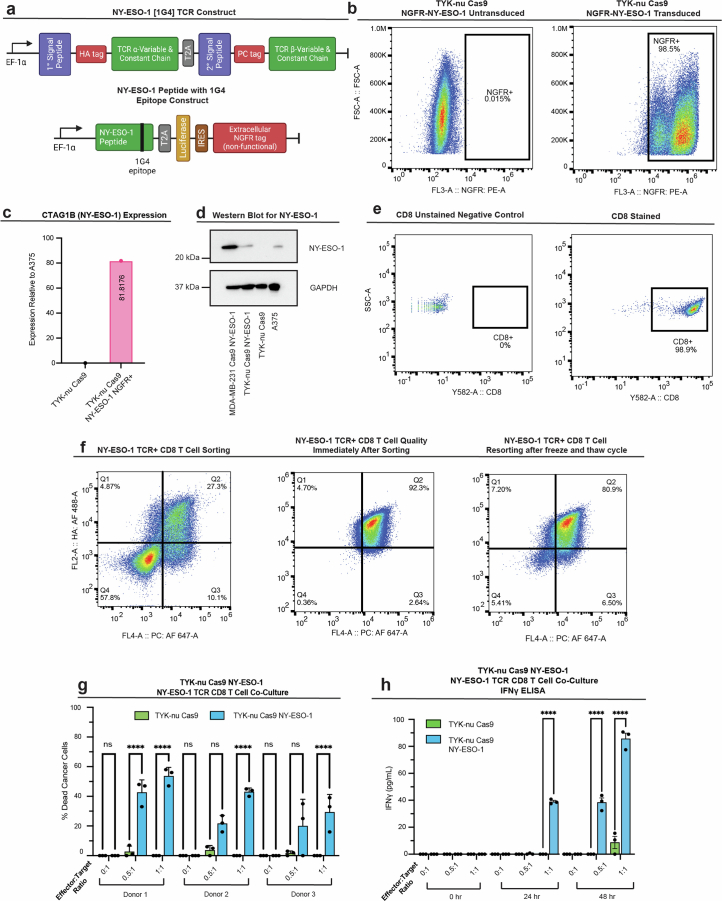

Extended Data Fig. 7. Establishing an ex vivo model of TCR-dependent T cell cytotoxicity.

(a) Top: NY-ESO-1 [1G4] TCR lentiviral construct used to engineer primary human CD8 T cells. Bottom: NY-ESO-1 peptide with 1G4 epitope lentiviral construct used to edit TYK-nu Cas9 cells to express the 1G4 NY-ESO-1 antigen. A non-functional, extracellular domain of human growth factor receptor (NGFR) was used to detect and isolate NY-ESO-1 expressing cancer cells. Created with BioRender.com. (b) Representative flow cytometric analysis gated on the expression of the non-functional NGFR tag to quantify TYK-nu Cas9 cells transduced to express NY-ESO-1 antigen (TYK-nuCas9,NY-ESO-1+). (c) qPCR quantification of CTAG1B mRNA expression in TYK-nuCas9,NY-ESO-1+ cells relative to A375 melanoma cell line with endogenous CTAG1B expression. (d) Western blot of NY-ESO-1 expression from NY-ESO-1 transduced MDA-MB-231 Cas9, TYK-nuCas9,NY-ESO-1+, TYK-nuCas9, and A375 whole cell lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown in (d) is one representative experiment repeated three times with similar results. (e) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD8+ T cells isolated from PBMC. (f) Representative flow cytometric analysis of NY-ESO-1 TCR transduced CD8 T cells. HA (α chain) and PC (β chain) double-positive CD8+ T cells were sorted (left). Cells were re-analyzed immediately after sorting to determine sorting quality (middle). Sorted HA+PC+ CD8+ T cells that were frozen and thawed were re-sorted to determine population purity over time (right). (g) TCR-dependent cytotoxicity: NY-ESO-1 TCR expressing primary CD8 T cells were co-cultured with TYK-nuCas9 cells or TYK-nuCas9,NY-ESO-1+ cells at variable effector to target cell ratios (E:T). The percentage of dead cancer cells was calculated by normalizing to cancer cell monoculture conditions. (h) ELISA quantification of IFNγ secreted in the co-culture supernatant (1:1000). In (g) and (h): co-cultures were performed using n = 3 technical replicates per condition and n = 3 different T cell donors; comparisons are indicated with brackets; p-values ****p < 1 × 10−4 (two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons for (g) and (h)); ‘ns’ denote non-significant (p > 0.05) comparisons. Exact p-values and raw blot images are provided with the Source Data. Data shown for (g) represent mean ± standard deviation and (h) mean ± s.e.m.

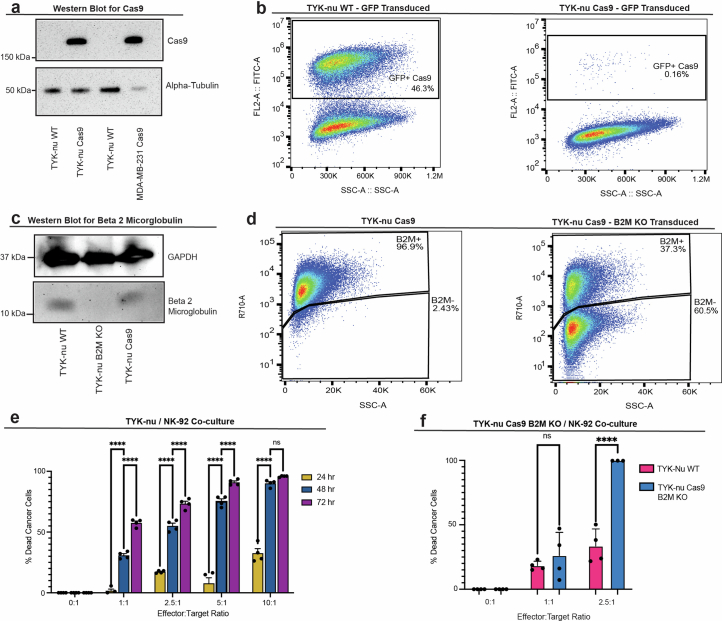

Extended Data Fig. 8. Establishing an in vitro cancer-NK model for CRISPR screens.

(a) Western blot of Cas9 protein from WT and Cas9 transduced whole cell lysates. Alpha tubulin measured as a loading control. (b) Representative flow cytometric analysis gated on GFP expression to measure Cas9 efficiency using pMCB306 plasmid. Loss of GFP denotes Cas9 activity (Methods). (c) Western blot of beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) from whole cell lysates of WT, Cas9, and B2MKO TYK-nu. GAPDH measured as a loading control. (d) B2M surface expression by flow cytometry in B2Mwt and B2MKO Cas9 TYK-nu cells. (e) 24-to-72-hour time course cell viability in co-cultures of TYK-nuCas9 and NK-92 cells at variable effector to target cell ratios. Percent killing was calculated by normalizing to monoculture conditions. Co-cultures were performed in 4 replicates per condition as shown. (f) 48-hour cell viability of B2MKO and B2MWT TYK-nu cell lines in co-culture with NK-92 cells. Percent killing was calculated by normalizing to the respective monoculture conditions. Data shown in (a) and (c) are one representative experiment repeated two or more times with similar results. In (e) and (f), co-culture data is represented by mean ± s.e.m. for (e) and mean ± standard deviation for (f) with each experiment performed in n = 4 technical replicates; p-values **** represent p < 1 × 10−4 and *p < 0.05 (two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons); ‘ns’ shown denote non-significant (p > 0.05) comparisons. Exact p-values and raw blot images are provided with the Source Data. All statistical tests were conducted on GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Perturb-seq screen in ovarian cancer identifies immune response regulators.

(a) Number of cells detected with sgRNAs targeting each gene in the CRISPR knockout (KO) library. (b) Gene expression of MTIL-up genes under different gene KOs. (c) Gene KOs mimic (top and second tows) and repress (third and bottom rows) transcriptional response to NK cells: Expression of KO gene signatures (ACTR8, MED12, IRF1, and STAT1) across ovarian cancer cells (n = 18,585 cells in each row) stratified based on culture condition and gene KO combination. Boxplots middle line: median; box edges: 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers: most extreme points that do not exceed ± IQR x 1.5; minima and maxima are depicted by extreme ends of whiskers.

Validating our hypothesis and approach, the top perturbations activating the program—PTPN1 and ACTR8 KO—sensitize malignant cells to T/NK cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 7b,d,e and Extended Data Fig. 9b), while the top perturbations that repress the program, IFNGR1, IRF1 and STAT1 KOs, confer resistance to T cell-mediated killing (Fig. 7b,d,e and Extended Data Fig. 9b). This further supports the causal link between CNAs of interferon signaling genes and MTIL expression (Fig. 5c). Knockout of MTIL repressors ACTR8, PTPN1, FGFR1, MAPK1 and MED12 was found to sensitize cancer cells to immune elimination also in previous in vivo CRISPR screens48–52. Demonstrating that the transcriptional response to TILs can be genetically rewired, our data also show that knockout of MTIL repressors (ACTR8, DNMT1, FGFR1, PTPN1, MED12 and MIF) mimics and amplifies the transcriptional responses to NK cells, while knockout of MTIL activators, as STAT1, IFNGR1, INTS2, IRF1, PARP12 and others, represses and counteracts the transcriptional response to NK cells (Fig. 7f–h and Extended Data Fig. 9c).

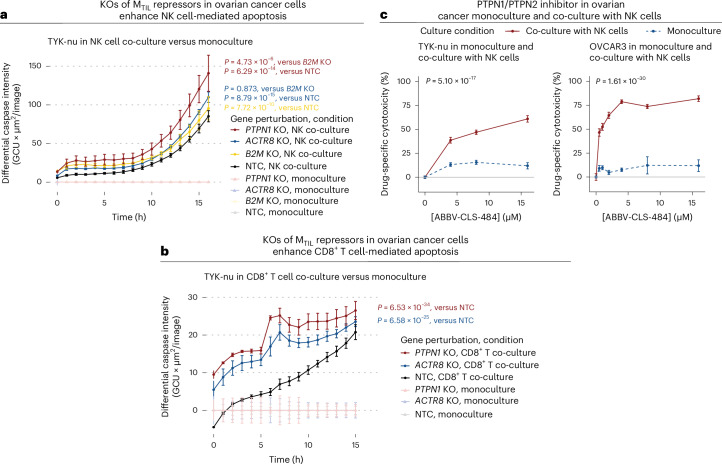

To examine if the inhibition of MTIL repressors substantially impacts immune-based cancer cell elimination, we generated syngeneic PTPN1 and ACTR8 KO TYK-nu ovarian cancer lines (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Both knockouts significantly sensitized the cancer cells to both NK cell-mediated cell death (P = 6.29 × 10−14 and P = 8.79 × 10−15 for PTPN1 KO and ACTR8 KO, respectively; time-controlled LMM in comparison to non-targeting control (NTC)) and T cell-mediated cell death (P = 6.53 × 10−34 and P = 6.58 × 10−25 for PTPN1 KO and ACTR8 KO, respectively; time-controlled LMM in comparison to NTC), as quantified over 16-h monitoring of caspase-3/caspase-7 activity in monoculture versus co-culture with NK-92 cells (Fig. 8a) and co-culture with TCR-engineered CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8b). Although ACTR8 is considered an essential gene (Supplementary Table 10c), its knockout did not impact ovarian cancer cell viability (Fig. 8a and Extended Data Fig. 10b). Focusing on NK cell-mediated killing, we tested the PTPN1/PTPN2 inhibitor ABBV-CLS-484 (refs. 50,69) in both the TYK-nu and OVCAR3 cell lines. The drug had minimal effect on cell viability in monoculture (Fig. 8c) but led to a substantial increase in ovarian cancer cell killing by NK cells, as observed for both ovarian cancer cell lines across a range of doses (P = 5.10 × 10−17 and P = 1.61 × 10−30, for TYK-nu and OVCAR3, respectively; dose-controlled LMM; Fig. 8c).

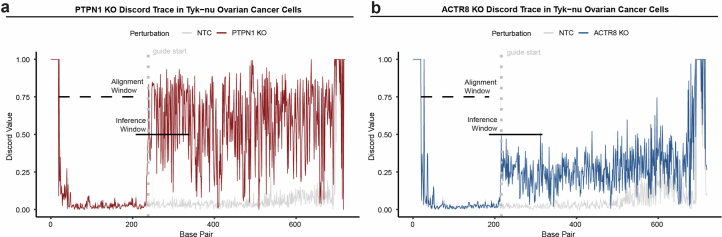

Extended Data Fig. 10. Validation of PTPN1 KO and ACTR8 KO in ovarian cancer cells.

(a-b) Discordance of base pairs corresponding to KO target genes (a) PTPN1 and (b) ACTR8 generated from Sanger sequencing using Synthego ICE Analysis tool (v3). Non-targeting control (NTC) depicted in grey. Alignment window for sequences depicted with dashed black bar; interference window for sequences depicted with solid black bar; start of guide sequence is depicted as a grey dotted line.

Fig. 8. Inhibiting MTIL repressors sensitizes cancer cells to T/NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

a, Fluorescent caspase-3/caspase-7 activity monitored in NTC and PTPN1, ACTR8 and B2M KO syngeneic TYK-nu cell lines in monoculture and co-culture with NK-92 cells over 16 h. b, Fluorescent caspase-3/caspase-7 activity monitored in NTC, PTPN1 and ACTR8 KO syngeneic TYK-nu cell lines in monoculture and co-culture with TCR-specific CD8+ T cells over 16 h. In a and b, P values were derived from Satterthwaite’s ANOVA in time-controlled two-sided LMMs; n = 3 technical replicates per experimental condition. c, PTPN1/PTPN2 inhibitor (ABBV-CLS-484) increased NK-mediated cytotoxicity in TYK-nu (left) and OVCAR3 (right) ovarian cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. P values were derived from Satterthwaite’s ANOVA in dose-controlled two-sided LMMs; n = 3 technical replicates per experimental condition. For a–c, all data shown represent the mean + s.e.m. GCU, global counting unit.

Discussion

Here we provide a comprehensive spatial mapping of HGSC tumors, revealing generalizable principles of tissue organization and lymphocyte infiltration within these aggressive and genetically unstable tumors. Our study demonstrates the connection between somatic genetic aberrations, malignant transcriptional dysregulation and immune evasion at the cellular and tissue levels, providing a new perspective to the barriers preventing the antitumor immune response in patients with HGSC and new leads to de-repress HGSC cancer immunogenicity.

Our study puts forward new frameworks to delineate complex multicellular processes and phenotypes through the lens of spatial organization. These include linking cell states to genetic variation across individuals and using existing Perturb-seq datasets to identify latent regulators of spatial cell states. We show that our data-driven approach provides a framework to uncover cell-state regulators, even when the transcriptional level of the regulator is not linked to the cell state of interest in the unperturbed state (for example, PTPN1). As available Perturb-seq datasets are still limited in their scope and diversity (Supplementary Discussion), it is likely that we are still not fully scanning the search space of cell-state regulators. In the case of the MTIL program, additional MTIL regulators beyond those identified here probably exist, as further suggested by our CNA analyses. As more Perturb-seq datasets, as the one generated here, become available across a more diverse range of cell types and conditions, it will be possible to use Perturb-seq data more effectively to extrapolate from one context to another with increasing accuracy70,71 and, in the case of malignant cell states, using CNA-to-RNA and CNA-to-cell-state associations to further guide Perturb-seq experimental design.

The key findings from our study provide new leads and resources to study HGSC immune evasion toward new diagnostic and intervention strategies.

ICB and other immunotherapies have shown modest effects in tumors with low TIL levels at baseline3,15. Our findings demonstrate that this may be not only due to immune exclusion per se, but also due to malignant cell-intrinsic differences between TIL-rich and TIL-deprived tumors that protect malignant cells even in the presence of targeting CTLs. Supporting this model, we show that CTLs have a substantial effect on the cancer cell transcriptome (Fig. 7c), such that perturbing malignant cells to prevent or enhance this malignant cell transcriptional response significantly impacts cancer cell susceptibility to CTL cytotoxicity, as we show in highly controlled co-cultures where spatial segregation is unlikely to have a major effect.

We show that stratifying patients based on such malignant cell-intrinsic features—whether through gene expression or CNAs—can help determine patient response to ICB and which aspects of the immune response are genetically dysregulated. Instead of a single immune evasion driver, we propose that immune evasion in HGSC is a result of the composite effects of multiple gene deletions and amplifications that dysregulate both well-established mechanisms (as interferon signaling and chemokine mediated recruitment) as well as specific genes and processes proposed by our analyses and data (for example, BMP7 and RUNX1). As ST data provide a single snapshot in time, we also note that MTIL-high areas that are deprived of TILs may mark situations where the snapshot is not representative of TIL location in the past or the probability that these areas will be infiltrated in the future. This may explain the improved ability of MTIL to predict clinical response to ICB compared to TIL levels in certain cohorts.

We anticipate that the detailed mapping of HGSC tumors provided here will help inform the design of new interventions including T/NK cell engineering strategies to enhance T/NK cell infiltration. Our findings demonstrate that the stroma differentially retains or sequesters certain subsets of T/NK cells, but not others, providing new leads to activate or inhibit chemokine receptors as CXCR6 and CXCR4 to mobilize endogenous or engineered T/NK cells into the tumor. Our findings also underscore the need to map T cell clonality as a function of location at the micro level to examine whether T cells that reside in the malignant and stromal compartments are part of the same or different TCR clones, and dynamically track tumor-reactive T/NK cells to examine if these can egress back to the stroma to avoid or reverse exhaustion72.

Our data provide new leads to target HGSC resistance, including the inhibition of ACTR8 and PTPN1. PTPN1’s protein product PTP1b is inactivated by oxidation73, which may explain MTIL activation under oxidative stress (as indicated by the upregulation of GPX3 and SOD2). PTP1b posttranscriptional regulation may also explain why it could not have been identified as an MTIL regulator with a standard approach of gene expression correlations. PTP1b is a negative regulator of insulin and leptin signaling74 that has been an attractive drug target for treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity75–78. PTPN1 KO mice have been shown to be viable and resistant to the development of obesity and diabetes, with more recent work demonstrating that PTPN1/PTPN2 inhibition is enhancing antitumor immune response, primarily via activation of CD8+ T cells50,69,79. Here we show that PTPN1 KO in ovarian cancer cells as well as its inhibition via ABBV-CLS-484 selectively sensitized ovarian cancer cells to both T cell-mediated and NK cell-mediated killing, providing rationale to include patients with HGSC in the ongoing phase I clinical trials (NCT04777994 and NCT04417465)80,81.

Taken together, this integrative study provides a blueprint to functionally map and probe the molecular landscape of multicellular interplay in complex biological tissues and reveals spatial, molecular and genetic aspects of immune escape in HGSC, opening new avenues to activate targeted immune responses.

Methods

Human tumor specimen collection

All ST data other than the Validation 2 dataset were obtained from archival clinical FFPE tumor tissues, retrospectively procured from archival storage under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol (number 44615). In patients with both adnexal and omental tumors available for study, tumor blocks from both sites were selected by an expert gynecologic pathologist (B.E.H.) using histopathologic review of the associated H&E slides. HGSC diagnosis was confirmed in all cases. Tumor content as well as tissue quality and preservation were assessed for inclusion in the study. The Validation 2 dataset was obtained from fresh HGSC tumors that were collected at the time of surgery by Stanford Tissue Procurement Shared Resource facility with the appropriate written informed consent and institutional IRB approval (number 11977). Samples were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C until requested for this study. Samples were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. Sections were generated using a cryostat and stained with H&E, which were reviewed by an expert gynecologic pathologist (B.E.H.) to confirm the diagnosis, quality and tumor content. Summary statistics of tissue sections, tumors and patients profiled are available in Supplementary Table 1a. Annotations at the patient level and tissue level are provided in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2a,b, respectively.

Primary CD8+ T cells were isolated from de-identified blood samples received from the Stanford Blood Center (IRB number 13942).

Tumor tissue DNA sequencing

HGSC tumor sample selection for next-generation sequencing (NGS) was based on the assessment of overall tumor content by a board-certified expert pathologist (B.E.H). Solid tumor tissue was digested by proteinase K. Total nucleic acid was extracted from FFPE tissue sections using Chemagic 360 sample-specific extraction kits (PerkinElmer). Percentage tumor cellularity as a ratio of tumor to normal nuclei was verified against pathologist-derived assessment, with a minimum requirement of 20% tumor content. Macro-dissection was utilized as required to enrich specimens below the 20% threshold. Specimens that met the 20% threshold of tumor to normal nuclei were selected for DNA sequencing. DNA sequencing was subsequently performed via Tempus Labs according to the xT platform protocol83. Additional information about NGS data generation and processing is provided in Supplementary Information Section 1.9.

ST data collection via SMI

The Discovery and Test datasets were generated using the CosMx SMI instrument according to the company’s protocols as described here and in greater detail in Supplementary Information Section 1.5. In brief, CosMx Universal Cell Characterization RNA 960-gene panel and the CosMx Human 6K Discovery Panel were used (Supplementary Table 1b), consisting of ISH probes. Each reporter set contains 16 readout rounds with four different fluorophores, creating a 64-bit barcode design with a Hamming distance of 4 (HD4) and a Hamming weight of 4 (HW4) to ensure low error rates. Probe fluorescence was detected at subcellular resolution via the CosMx SMI instrument, and the signal was aggregated to identify the specific RNA molecule measured in each location21.

SMI tissue preparation and RNA assay were performed as follows. Five-micron tissue sections were cut from FFPE TMA tissue blocks and adhered onto VWR Superfrost Plus Micro Slides (VWR, 48311-703) or Leica BOND Plus slides (Leica Biosystems, S21.2113.A). After sectioning, the tissue sections were air-dried overnight at room temperature. Tissue preparation was performed as described in the CosMx SMI Manual Slide Preparation Manual (MAN-10184-02). Briefly, the tissues underwent deparaffinization, heat-induced epitope retrieval for 15 min at 100 °C, and enzymatic permeabilization with 3 µg ml−1 digestion buffer for 30 min at 40 °C. Subsequently, a 0.0005% working concentration of fiducials were applied to the tissue, followed by post-fixation and blocking using NHS-acetate. Finally, an overnight hybridization was performed using the CosMx Universal Cell Characterization 960 plex RNA Panel or the CosMx Human 6K Discovery Panel of probes. The next day, the tissues were subjected to stringent washes to eliminate any unbound probes. The tissues were stained with CosMx Nuclear Stain, CosMx Hs CD298/B2M, CosMx Hs PanCK/CD45 and CosMx Hs CD3 nuclear and segmentation markers before loading onto the instrument. The slide and coverslip constitute the flow cell, which was placed within a fluidic manifold on the SMI instrument for morphological imaging and in situ analyte readout. Analysis run on the instrument was set up using the 60 s FOV pre-bleaching profile and segmentation profile for human tissue.

ST data collection via Xenium

The Validation 1 dataset was generated via 10x Genomics’ Xenium platform according to the company’s protocols as described here and in greater detail in Supplementary Information Section 1.6. In brief, 10x Genomics’ Xenium ISS technology was used with the Xenium Human Breast Panel for multiplexed measurement of 280 genes (Supplementary Table 1b). Xenium hybridization padlock probes were designed to contain two complementary sequences that hybridize to the target RNA84. Probes also contain a third sequence encoding for a gene-specific barcode such that once the paired ends of the probe bind to the target RNA and ligate, a circular DNA probe is generated for rolling circle amplification. Five-micron FFPE TMAs were sectioned onto a Xenium slide, deparaffinated, permeabilized and incubated with a Xenium probe for probe hybridization and barcode amplification, as described in detail in Supplementary Information Section 1.6. Following washing and background fluorescence quenching84, slides were placed into an imaging cassette and loaded on the Xenium Analyzer instrument for morphological imaging and in situ analyte readout.

ST data collection via MERFISH

The Validation 2 dataset was generated via the Vizgen platform according to the company’s protocols as described here and in greater detail in Supplementary Information Section 1.7. In brief, a custom 140-gene panel was designed with an additional set of 50 blank negative control barcodes based on the MERFISH design that incorporates combinatorial labeling with an error-robust encoding scheme to mitigate detection errors85. Four HGSC fresh-frozen tissue samples were preserved in OCT compound and stored at −80 °C before sectioning. Ten-micron tissue sections were cut from the fresh-frozen OCT tissue blocks and adhered onto MERSCOPE slides (Vizgen, 20400001). After sectioning, the tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS for 15 min, washed three times with 1× PBS, and incubated overnight at 4 °C in 70% ethanol. As described in detail in Supplementary Information Section 1.7, following tissue sample preparation process samples were loaded onto the MERSCOPE instrument (Vizgen, 10000001) for analyte readout and morphological imaging.

Cell segmentation

Cell segmentation was performed using a deep-learning-based segmentation image processing algorithm, Mesmer86, from the DeepCell platform on raw TIFF images. The cell segmentation algorithm was chosen after systematic comparisons with the Omnipose87 algorithm as described in Supplementary Information Section 1.7 (Extended Data Fig. 1a–f). The inputs for whole-cell segmentation for SMI images included immunofluorescence (IF) images of DAPI and CD298/B2M for nuclear and cell membrane detection, respectively. MERFISH whole-cell image segmentation was performed with DAPI and cell membrane stains (Vizgen stain boundary kit, 10400009). Nuclear segmentation was performed for ISS images wherein the input includes DAPI IF stain.

ST data quantification and processing

Preprocessed RNA in situ data include RNA transcripts confidently identified for each gene and their spatial coordinates. Given these data, each RNA transcript was aligned to the cell segmentation outputs described above based on its spatial coordinates. Cell count matrices, C, were generated by counting the number of RNA transcripts detected within the segmentation boundaries of each cell j for each gene i to yield for entry of C in each ST dataset. Cell counts were converted to transcripts per million (TPM) according to equation (1):

| 1 |

where G is the total number of genes in each ST dataset.

Expression levels were quantified as shown by equation (2):

| 2 |

Cells with fewer than 50, 20 and 5 genes detected in the SMI, Xenium and MERFISH data were excluded, as well as cells with exceptionally large volume (>441 μm2).

Expression of a gene signature or set was computed by considering all the genes in the signature/set, with additional normalizations to filter technical variation, similarly to the procedure reported before88 with some modifications as described in Supplementary Information Section 2.1. For gene programs, the expression of the upregulated set minus the expression of the downregulated set was computed as the program expression.

The location of each cell was defined based on the location of its centroid. The r-neighborhood of a cell was defined as all the cells that reside at a distance of at most r μm from the cell. Spatial frames were defined by binning the tissue section FOV to squares with a size of 60 μm × 60 μm (that is, 3,600 μm2), with a median number of 53 cells per frame.

As described in detail in Supplementary Information Section 2.2, the cell-type annotation procedure was applied separately for each of the three spatial datasets via an initial cell-type assignment followed by an iterative subsampling procedure to obtain robust cell-type assignments with confidence levels. Cell-type signatures used for this purpose were derived from previous HGSC scRNA-seq datasets26,27,29,89.

Co-embedding ST and scRNA-seq datasets

A reference single-cell atlas was generated to examine consistency across spatial and scRNA-seq cohorts and validate cell-type annotations. The atlas includes spatial datasets collected here and six scRNA-seq HGSC cohorts17,24–29. Preprocessed gene expression matrices were downloaded from Synapse (syn33521743)17, the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; GSE118828, GSE173682, GSE147082 and GSE154600)24,26,25,28 and https://lambrechtslab.sites.vib.be/en/data-access/27,29. Tumor samples derived from other anatomical sites, other than the adnexa or omentum, were removed to match the scope of this study. All nine datasets were co-embedded with reciprocal principal component analysis using the top 30 PCs fit on each dataset, using the Seurat R package version 5.1.0 implementation90, and then visualized with two-dimensional UMAP91. A detailed description of the co-embedding pipeline is available in Supplementary Information Section 2.3.

Mixed-effects modeling