Abstract

T cell inhibitory mechanisms prevent autoimmune reactions, while cancer immunotherapy aims to remove these inhibitory signals. Chronic ultraviolet (UV) exposure attenuates autoimmunity through promotion of poorly understood immune-suppressive mechanisms. Here we show that mice with subcutaneous melanoma are not responsive to anti-PD1 immunotherapy following chronic UV irradiation, given prior to tumor injection, due to the suppression of T cell killing ability in skin-draining lymph nodes. Using mass cytometry and single-cell RNA-sequencing analyzes, we discover that skin-specific, UV-induced suppression of T-cells killing activity is mediated by upregulation of a Ly6ahigh T-cell subpopulation. Independently of the UV effect, Ly6ahigh T cells are induced by chronic type-1 interferon in the tumor microenvironment. Treatment with an anti-Ly6a antibody enhances the anti-tumoral cytotoxic activity of T cells and reprograms their mitochondrial metabolism via the Erk/cMyc axis. Treatment with an anti-Ly6a antibody inhibits tumor growth in mice resistant to anti-PD1 therapy. Applying our findings in humans could lead to an immunotherapy treatment for patients with resistance to existing treatments.

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Immunotherapy, Cancer immunotherapy

Chronic UV exposure has been associated with immune system suppression. Here the authors show that enhanced tumor growth and resistance to PD1 blockade in mice exposed to UV irradiation is associated with induced expression of Ly6a in CD8 + T cells and that targeting Ly6a enhances anti-tumor immune responses in models resistant to anti-PD1.

Introduction

For more than 3500 years, sunlight has been used as a treatment for skin autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and vitiligo1. About 30 years ago, it was discovered that ultraviolet radiation B (UVB) inhibits the immune response to cancer in mice2,3. The suppressive effects of UVB are mediated by alterations in immune cell phenotypes4. Many mechanisms have been suggested to explain how UVB induces immunosuppression. Some, such as increases in platelet activation factor, cis-urocanic acid, and vitamin D levels, affect not only in the skin but also internal organs5–7. Other mechanisms are more local such as the migration of UVB-exposed Langerhans cells from the skin to the skin-draining lymph nodes (sDLNs)8. Importantly, in the context of cancer, exposure of mice to UVB before cancer cell injection inhibits the immune response to cancer via T cell modulation9. However, how UVB exposure inhibits the T cell response to cancer is not well understood.

Cancer cells often express antigens that are recognized by the immune system; however, cancer cells are “self” cells, and some mechanisms that inhibit the immune system’s response to self, including PD1- and CTLA4-mediated signaling, are endogenous mechanisms that prevent an autoimmune response10. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown remarkable efficacy as therapeutic interventions in melanoma11, about 50% of patients are treatment-resistant12.

We reasoned that use of UVB, which inhibits autoimmunity as well as the immune response to cancer, could serve as a platform for investigation the regulation of the immune response to cancer, possibly leading to the identification of factors that could be targeted for development of new treatments for cancer.

Here, we show that UVB exposure prior to melanoma cell injection enhances tumor growth and induces resistance to anti-PD1 antibody treatment in mice via inhibition of the CD8+ T cell response to tumors in the skin. This repressive effect on T cells is specific to skin and sDLNs and is not observed in internal immune organs. In this work, we report that UVB induces expression of Ly6a in T cells. Ly6a expression is also increased upon chronic exposure to type 1 interferon (IFN), which accelerates the exhaustion of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Moreover, antibodies against Ly6a enhances the T cell response to tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, our data indicate that targeting Ly6a should enhance the immune response to cancer.

Results

Chronic UVB exposure suppresses sDLN CD8+ T cell-mediated killing and induces resistance to melanoma immunotherapy

Previous reports have demonstrated that chronic exposure to UVB upregulates various mechanisms of immune suppression across the organism13–19. Although the suppressive effects of UVB are beneficial during treatment of certain autoimmune disorders, the opposite may be true for cancer. UVB exposure before cancer cell injection inhibits the immune response to the cancer cells and enhances primary tumor growth9, but how UVB influences tumor progression, specifically on metastases, has yet to be assessed. Thus, we evaluated the local and systemic immunosuppression mechanisms in response to melanoma induction in immunocompetent mice that had been chronically exposed to UVB. Mice were irradiated five times per week for 8 weeks with UVB exposure, then Ret melanoma cells20,21 were injected subcutaneously to induce skin tumors or intravenously to induce metastases as previously described22. Local tumor growth and metastatic burden were measured over time (Fig. 1a). In agreement with previous studies2, UVB-irradiated mice injected subcutaneously with melanoma cells had significantly higher local tumor growth rates than control mice that were mock irradiated (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 1a, b).

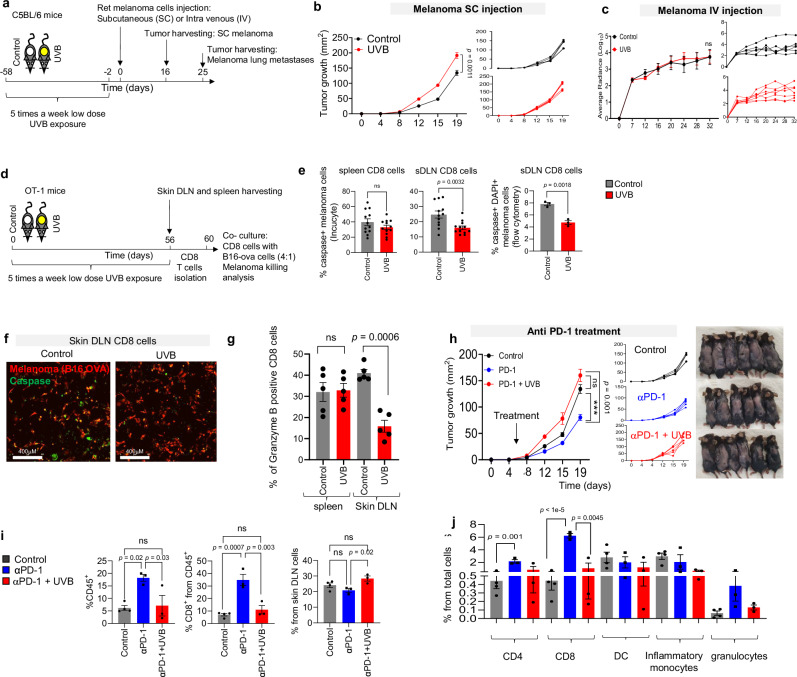

Fig. 1. Chronic UVB exposure suppresses sDLN CD8+ T cell-mediated killing and induces resistance to melanoma immunotherapy.

a Experimental flowchart. b Mean tumor diameter (left) and individual plots (right) of SC Ret melanoma tumors growth in UVB- and mock-treated mice (n = 4 per group). c Average radiances (left) and data for individual UVB- and mock-treated mice (right) with Ret melanoma lung metastases (n = 7 per group). d Experimental flowchart. e, f B16-OVA melanoma cells were incubated with OT-I CD8+ T cells isolated from UVB- or mock-irradiated mice. e Mean percentages of caspase 3/7+ melanoma cells based on Incucyte data (n = 10 per group) (left) and flow cytometry (n = 3 per group) (right). f Representative images (out of n = 10) of Caspase 3/7 staining. g Mean percentages of Granzyme B expression in T cells isolated from sDLN (Skin Drained Lymph Nodes) of UVB- or mock-irradiated (control) mice (n = 6 per group). h–j Mice treated with UVB or mock-irradiated were injected subcutaneously with Ret melanoma cells and treated with anti-PD1 antibody or IgG control. Arrows indicate time of antibody injections. h Mean tumor diameters with arrow indicating time of antibody injection (n = 6 per group) (left), data for individual mice (middle), and representative images of the mice described (right). i Flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells (left), tumor-infiltrating CD8+ cells (middle), and CD8+ cells (right) in sDLNs (n = 4 control group and n = 3 UVB, UVB PD1 groups). j Flow cytometry analysis of percent of immune infiltrate cell types (n = 4 control group and n = 3 UVB, UVB PD1 groups). Shown are means ± SEM from one experiment out of three performed. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA test with Tukey correction (b, c, h), one-way ANOVA test with Tukey correction (i and j), or two-tailed t test (e, g). n.s. not significant. Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, mice were intravenously injected with Ret melanoma cells that express mCherry and luciferase to allow tracking of lung metastases that develop independently of the primary tumor burden in the skin. Bioluminescence quantification indicated that, in contrast to the enhanced tumor growth in the skin, no differences in growth rates of lung metastases between the UVB-irradiated mice and the control group were observed when melanoma cells were injected intravenously (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Similarly, quantification of levels of the mRNA encoding mCherry in micro-metastases in liver and inguinal and brachial lymph nodes showed no significant differences between UVB-treated and control mice (Supplementary Fig. 1d). This indicates that UVB treatment prior to tumor initiation enhances local tumor growth but does not enhance metastasis.

To test the effect of UVB on T cell responses to melanoma, we used C57BL/6 J OT-1 mice, which were genetically engineered to recognize the OVA albumin antigen23 and thus respond to B16 melanoma cells that over express the OVA peptide (B16-OVA). Dorsally shaved C57BL/6 J OT-1 mice were chronically exposed to low-dose UVB irradiation or were mock-irradiated as controls (Fig. 1d). Spleens and sDLNs are reflective of systemic and local effects of UVB, respectively. CD8+ T cells from sDLNs and spleens of UVB-exposed and from control mice were co-cultured with B16-OVA cells for 24 h. We found that UVB treatment significantly inhibited the ability of sDLN CD8+ T cells to kill tumor cells as shown by quantification of apoptotic melanoma cells in live imaging analyzes and in flow cytometry analyzes of DAPI+/caspase 3/7+ melanoma cells (Fig. 1e, f), but there was no significant difference in cell killing by spleen CD8+ T cells from UVB- and mock-irradiated mice (Fig. 1e, f). In accordance with these data, there was a significant decrease in Granzyme B in sDLN CD8+ cells, but not in the spleen CD8+ cells, from mice following UVB treatment (Fig. 1g).

Given the reduction in CD8+ T cell activity due to UVB irradiation, we next examined whether UVB affected the efficacy of the immunotherapeutic anti-PD1 antibody. We found that anti-PD1 antibody treatment failed to inhibit tumor growth in UVB-irradiated mice, although it was effective in mock-irradiated controls (Fig. 1h). Flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) showed that UVB-treated mice had significantly fewer CD45+ immune cells and significantly lower percentages of CD8+ T cells relative to total cells and to CD45+ immune cells than control mice (Fig. 1i, left panel; Supplementary Fig. 1e, f). Thus, the lower percentage of CD8+ T cells in tumors of UVB-treated mice relative to controls is not a reflection of larger tumor size. Interestingly, examination of T cells from sDLNs showed the opposite trend: After anti-PD1 antibody treatment, the UVB-treated group had a higher percentage of CD8+ T cells relative to all sDLNs cells than the mock-irradiated group (Fig. 1i, right panel). Examination of other UVB-relevant immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, and granulocytes, showed no significant differences in percentage relative to total cells in UVB-irradiated versus mock-treated mice after anti-PD1 antibody treatment (Fig. 1j). Hence, we hypothesize that UVB exposure prior to injection of tumor cells alters T cell phenotypes and inhibits the response of CD8+ T cells to melanoma even in the presence of anti-PD1 immunotherapy treatment.

UVB induces a Ly6ahigh T cell subpopulation in the skin drain lymph nodes

To dissect the effect of UVB on the immune system at the local and systemic levels, we performed a multi-parameter mass cytometry analysis. We chronically UVB or mock irradiated dorsally shaved mice, isolated their spleen and sDLNs, and subjected single cells to mass cytometry analysis. We analyzed each cell type (Supplementary Fig. 2a; Supplementary Data 1) using UMAP dimensionality reduction to provide an overview of various reconstituted populations and employed FlowSOM algorithms for unsupervised cells clustering. We first performed unsupervised analysis of CD4+ T cells of the sDLNs, which revealed cell segregation according to known subsets of T cells23 including naïve (CD62L+/CD44-), effector and effector memory (CD44+/CD62L), and central memory (CD62L+/CD44+) T cells (Fig. 2a). Comparison between the UMAP density plots, which provides a topographic view of cells’ amount, of UVB and control sDLNs CD4+ cells from the sDLNs revealed that a subset of cells was present at higher levels in UVB-irradiated mice compared to mock-irradiated controls (Fig. 2b). This UVB-induced cell subset was also observed using FlowSOM, which showed that cluster L_CD4_6 was present at significantly higher frequency in the UVB-treatment group than the control group (control, 4.98%; UVB, 14.46%; P = 0.0097), whereas cluster L_CD4_3 was present at significantly lower frequency (control, 7.13%; UVB, 2.63%; P = 0.017; Fig. 2b, c). Cluster L_CD4_6 is a cluster of effector and effector memory cells that express high levels of Ly6a but not Ly6c, CD25, Tbet, or PD1; this expression pattern is unlike other effector and effector memory clusters L_CD4_4 and L_CD4_5 (Fig. 2c).

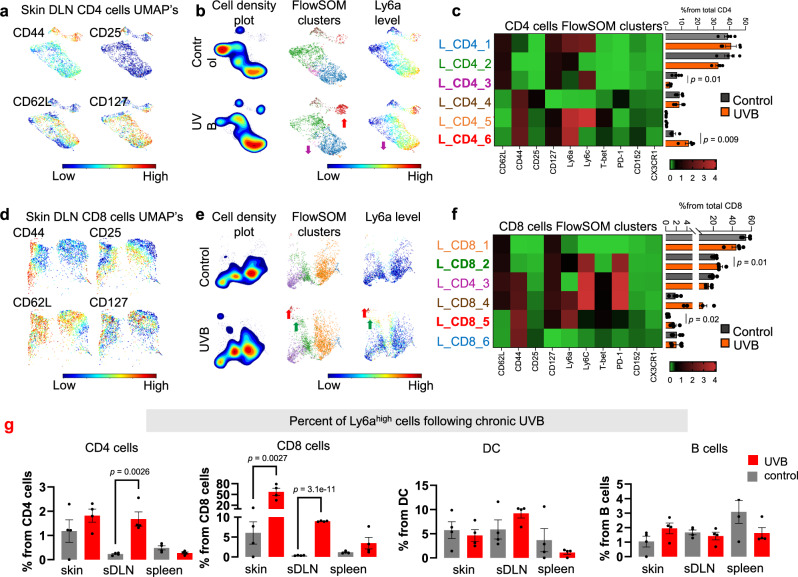

Fig. 2. UVB induces a Ly6ahigh T cell subpopulation in the skin drain lymph nodes.

a Representative UMAPs for CD4+ subset markers levels (red, high; blue, low) in sDLNs (skin Drained Lymph Nodes) of UVB- or mock-irradiated mice (n = 4 per condition). b Cell density plots (left), FlowSOM clusters indicated by different colors (middle), and Ly6a levels (red, high; blue, low) in CD4+ clusters from sDLNs of UVB- or mock-irradiated mice. Arrows, colored by cluster, indicate significantly higher or lower levels in UVB-irradiated versus mock-irradiated mice (n = 4 per condition). c Left: Heatmap of median expression levels of the indicated markers in CD4+ clusters of sDLNs. Colors reflect the transformed ratio relative to the minimum expression of the indicated marker in CD4+ cells. Right: Percentage of each cluster from the total population of CD4+ cells (n = 4 per condition). d–f Analyzes for sDLNs CD8+ cells analysis as done for CD4+ T cells in (a–c). g Mean percent of Ly6ahigh cells in various organs from UVB- and mock-treated mice (n = 4 per group). Statistical significance was determined in a two-tailed t test. n.s. not significant. Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we analyzed the CD8+ cells from sDLNs. The percentages of cluster L_CD8_2, which are CD44−/CD62L+/Ly6aint naïve CD8+ T cells (control, 21.6%; UVB, 27.63%; P = 0.04) and of cluster L_CD8_5 (effector memory CD44+/CD62L−/Ly6ahigh/CD8+ T cells; control, 0.43%; UVB, 1.59%; P = 0.023) were significantly higher upon UVB exposure than in controls (Fig. 2d–f). The increases in Ly6a+ CD8+ cells were observed upon UVB treatment independently of cell maturation status indicating that UVB exposure induces a general increase in Ly6a expression in CD8+ T cells. Supervised examination of the expression levels of all markers tested showed that UVB specifically enhanced Ly6a expression in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells but did not increase expression of other T cells markers that were examined (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Further, among all immune cells subtype identified by supervised mass cytometry analysis of sDLN, Ly6a expression was significantly increased only in T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

To validate the effect of UVB on Ly6a expression in T cells, B cells, and DCs in the skin, sDLN, and spleen, we repeated the experiment and subjected the indicated organs to flow cytometry analysis. We found that UVB irradiation significantly increased Ly6a expression on T cells and that this effect was observed in the skin and sDLN but not in the spleen (Fig. 2g). Mass cytometry analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in the spleen also showed no significant differences in Ly6a expression or in the percentages of T cell clusters in UVB- or mock-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 2d–j). Further, flow cytometry analysis of cells isolated from the skin, sDLN, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen showed that the increase in Ly6a following UVB is specific to the skin area and not these internal organs (Supplementary Fig. 2k–o). Taking together, we found that among all T cells markers that were examined, only Ly6a increases upon chronic UVB treatment, an increase which is specific to T cells in the skin area. These results, together with the evidence about UVB immunosuppressive effect on T cells immune response to tumor in the skin trigger us to investigate the role of Ly6a in T cells immunity and the mechanism behind the increase in Ly6a expression.

Ly6ahigh T cells are induced by type 1 IFN secreted by DCs following UVB

Previous studies have demonstrated that Ly6a is a marker of hematopoietic stem cells and of CD62L+/CD44− stem-like memory CD8+ T cells24. Additionally, Ly6a levels are increased in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to inflammatory cytokines25. Ly6a is detected on the membranes of T cells and other immune cells, but the functional role and its ligand are unknown26. Since our finding places Ly6a as a marker of T cells that is induced following UVB treatment, we used our experimental model to gain deeper insights into the function of Ly6a role. We conducted single-cell RNA sequencing of sDLN cells from mice following UVB or mock irradiation. To infer the evolving dynamics among different T cell subsets, we performed sub-clustering analyzes of CD8 and CD4 T cells (Fig. 3a). For defining CD8 and CD4 T cell subclusters, we employed the differentially expressed genes within each cluster (Supplementary Data 2). Our unsupervised clustering identified one cluster of CD4+ cells and one cluster of CD8+ cells that expressed high levels of Ly6a (cluster CD4_4 and cluster CD8_5, respectively; Fig. 3a). These clusters included the majority of the cells that expressed high levels of Ly6a in the mock-irradiated control mice, and thus are cells that have high Ly6a levels independently of UVB treatment. Enrichment test for predicting the active cytokines within these clusters using Response Enrichment Analysis27, showed a notable and distinct impact of the type 1 IFN response, both in CD4 and in CD8 cells (Fig. 3b). Notably, IFNα and IFNβ were the only cytokines identified in this analysis (Fig. 3b). These findings suggest that Ly6a marks a subset of IFN-exposed CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

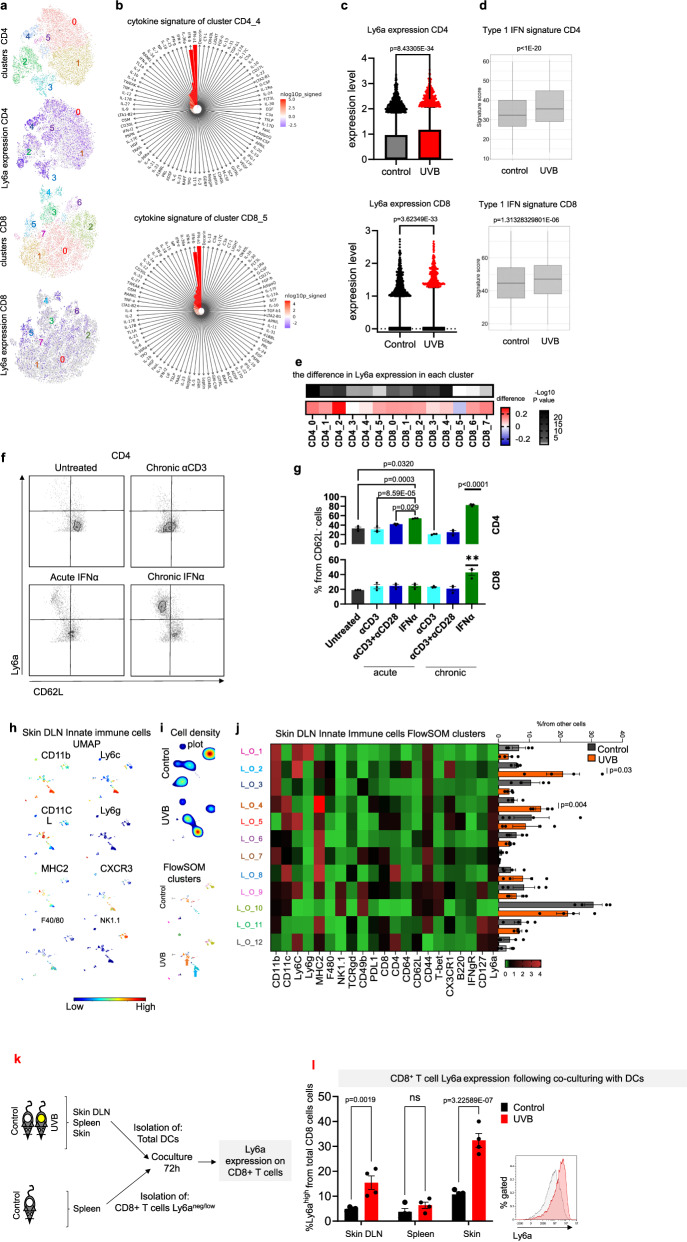

Fig. 3. Ly6ahigh T cells are induced by type 1 IFN secreted by DCs following UVB.

a–e Single-cell RNA-seq analyzes of sDLNs isolated from UVB- and mock-irradiated (control) mice (n = 3 and n = 4, respectively). a t-SNE projection of all 14,783 CD4+ T cells (upper panel) and all 14,020 CD8+ T cells (lower panel) with subsets indicated by colors and numbers, accompanied by t-SNE projections colored by the expression levels of Ly6a (purple) in each cell. b Prediction of the active cytokines within the clusters that express high levels of Ly6a (CD4_4- upper panel; and CD8_5- lower panel). Red indicates a significant level of the activation signature. c Box plot (box represents percentile 25–75 and the median and whiskers represent the range between 10–90; points above the whiskers are drawn as individual points) of Ly6a expression in CD4+ T cells (upper) and CD8+ T cells (lower) following chronic UVB or mock irradiation (control) treatments. d Box plots (box represents percentile 25–75 and the median and whiskers represent the range between minima and maxima) of type 1 IFN signature of CD4+ T cells (upper) and CD8+ T cells (lower) following chronic UVB or mock irradiation (control) treatment. e Heatmap of difference (and significance level in Ly6a expression in UVB-treated mice versus mock-irradiated controls in each cluster of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. f Representative flow cytometry images of Ly6a expression in splenic T cells activated ex vivo as indicated. g Mean percentages of Ly6a expression in splenic T cells activated ex vivo as indicated (n = 3 per condition). h Representative UMAP plots of non-T and non-B cells in sDLNs (skin Drained Lymph Nodes) from UVB- or mock-irradiated (control) mice (n = 4 per condition). i FlowSOM clusters in sDLNs from UVB- or mock-irradiated (control) mice (n = 4 per condition). j Left: Heatmap of median expression levels of the indicated markers in clusters of sDLNs. Colors reflect the transformed ratio relative to the minimum expression of the indicated marker in CD4+ cells. Right: Percentage of each cluster from the total innate cell population (n = 4 per condition). k Experimental flowchart. l Mean percentages of Ly6a levels in Ly6aneg/low/CD4+ cells after 72 h of co-culture with spleen or sDLN CD11b+ cells from UVB irradiated mice (n = 4 mice per group). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t test (c–e, h, i, j, l) or one-way ANOVA test with Tukey correction (g). n.s. not significant. Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In line with our mass cytometry and flow cytometry results, we found a significant increase in Ly6a expression in UVB-treated versus control mice (Fig. 3c). The increase in Ly6a expression following UVB was accompanied by an increase in expression of type 1 IFN signature genes (Fig. 3d). Notably, the increases in Ly6a expression after UVB treatment was observed in multiple clusters of CD4+ and CD8+ cells including clusters of naïve/memory cells and regulatory cells (clusters 0, 1, 2, and 5 of CD4+ cells and clusters 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 in CD8+ cells; Supplementary Data 2; Fig. 3e). For example, in cluster CD4_2, (regulatory T cells) the significant increase in Ly6a expression following UVB was accompanied by type 1 IFN signature enhancement (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). The genetic association between Ly6a expression in T cells and type 1 IFN signature genes was validated using independent single-cell RNA sequencing data of T cells28 (Supplementary Fig. 3c; Supplementary Data 3). These data suggest that Ly6ahigh T cells are a subset of type 1 interferon exposed cells, that respond to the chronic effects of UVB exposure and thus may be targeted to counteract UVB immunosuppression.

To better understand the mechanisms behind Ly6a induction in T cells, we tested the effects of various cytokines (IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IFNα, IFNγ, and TNFα) and T cell receptor (TCR) activation factors (anti-CD3 antibody, anti-CD28 antibody, lipopolysaccharide, and CL307) on Ly6a levels. We found that almost all tested cytokines and activation factors (except for IL-1 for CD8+ T cells) significantly increased Ly6a levels; IFNα had the strongest effect (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Since during UVB exposure and in the tumor environment, the exposure to the inflammatory environment is continuous, we also examined the effect of chronic exposure to either IFNα or TCR activation. As expected, chronic TCR activation by chronic exposure to anti-CD3 antibody or to anti-CD3 antibody plus anti-CD28 antibody increased the number of CD62L− effector T cells (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 3e, f); however, most of these cells did not express Ly6a, and there was no increase in the percent of Ly6ahigh cells in CD4+ or CD8+ effector and effector memory compartments (Fig. 3f, g; Supplementary Fig. 3e). In contrast, upon chronic IFNα exposure, almost all cells expressed Ly6a, and the percentage of Ly6ahigh cells was significantly increased in both CD4+ and CD8+ compartments (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 3e). Chronic IFNα treatment, but not the other treatments, significantly increased Ly6a levels in CD62L−/CD4+ and in CD62L−/CD8+ compartments (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Taken together, these data suggest that Ly6a is a marker of T cells found in a chronically inflamed environment such as results from UVB chronic exposure or at the tumor microenvironment, and that Ly6a expression is induced following exposure to type 1 IFN rather than due to continuous signaling through TCR.

To identify the cells that regulate type 1 IFN-mediated induction of Ly6a expression on T cells, we analyzed the effect of UVB on all immune cells in the sDLN of UVB- or mock-irradiated mice using mass cytometry. Analysis of B cells showed no significant differences in B cell clusters in the sDLNs or spleens between UVB-exposed and mock-irradiated mice (Supplementary Fig. 3g–l). All other cell types, which were detected at lower percentages than T or B cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a), were then analyzed in one group of “non T and non B cell”, or “other immune cells” as we termed, other lymph node clusters (L_O). UMAP and FlowSOM analyzes showed significantly higher frequencies of cluster L_O_2, which contains inflammatory monocytes (control, 5.91%; UVB, 20.87%; P = 0.031), and in cluster L_O_4, which contains dendritic cells (CD11c+ /MHC2high/CD8−/CD11b+; control, 5.01%; UVB, 13.78%; P = 0.0048; Fig. 3h–j). These results are in line with the previous work that showed that UVB increases frequencies of monocytes in the skin and in sDLN due to secretion of inflammatory cytokines from the skin upon UVB exposure29 and DC migration from the skin to the sDLN8.

We detected significantly higher levels of cluster S_O_4, which contains CD11b+/Ly6g+/Ly6clow granulocytes, but not in inflammatory monocytes or DC subtypes, in spleens of UVB-treated mice compared to mock-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 3m–o) in agreement with an earlier study that demonstrated that UVB induces neutrophil migration not only to the skin but also to internal organs such as spleen, lung, and kidney18. UVB irradiation did not have a significant effect on natural killer cell percentages or phenotypes in sDLNs or in the spleen (Fig. 3h–j; Supplementary Fig. 3m–o). In accordance with the unsupervised analyses, supervised analysis of the mass cytometry data showed that UVB exposure significantly increased the percentage of CD11b+ DCs and inflammatory monocytes as a fraction of all CD45+ cells in the sDLNs but not in the spleen, whereas granulocyte frequencies were significantly increased in the spleen but not in the sDLNs (Supplementary Fig. 3p). This indicates that UVB has a skin-specific effect on adaptive immune cells such as T cells and also on the innate immune cells including DCs and monocytes.

To examine the potential role of UV-induced DCs in modulating Ly6ahigh expression in T cells, we isolated DCs from the skin, lymph nodes, and spleens of UVB-treated or mock-irradiated mice. Isolated cells were then co-cultured for 48 h with T cells that expressed no or low levels of Ly6a sorted from the spleens of naive mice, followed by flow cytometry analysis of the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells that expressed high levels of Ly6a (Fig. 3k). Significantly higher percentages of Ly6ahigh/CD8+ cells were detected upon incubation with DCs from sDLNs or skin of UVB-exposed mice compared to DCs isolated from mock-irradiated (control) mice; levels in upon incubation with splenic DCs were similar in the two groups (Fig. 3l). This suggests that the skin-specific effect of UVB on T cell phenotype is mediated by UVB-induced migration of myeloid cells to the skin area. Blocking of IFNα in the secreted media of the isolated DCs inhibited DC-mediated induction of Ly6a expression on T cells (Supplementary Fig. 3q, r). Taken jointly, our data suggests that chronic exposure of CD8+ T cells to type 1 IFN, predominantly secreted by UV-activated DCs, induces Ly6a expression.

Ly6ahigh T cells are enriched in the tumor microenvironment independently of UVB exposure

Next, we examined whether Ly6a expressing T cells are present in the immunosuppressed tumor environment. Significantly higher levels of Ly6a expression were detected on MC38 colon cancer TILs than on T cells of spleen or lymph nodes (Fig. 4a, b; Supplementary Fig. 4a). In contrast, Ly6a levels in B cells, DCs, and macrophages from the tumor microenvironment did not differ significantly from Ly6a levels in those cells isolated from other organs (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Consistent with this, when we analyzed published single-cell RNA sequencing data of TILs compared to T-cells from lymph nodes30, we found significantly higher levels of Ly6a in B16 melanoma TILs than in T cells from lymph nodes (Fig. 4c). Further, in the Ret melanoma metastasis mouse model, we found that Ly6ahigh TILs were enriched in lung metastases, as shown by mass cytometry analysis (Fig. 4d). This demonstrates that the induction of Ly6a occurs in primary and metastatic tumors but not in adjacent lymph nodes. Further, we analyzed markers associated with Ly6ahigh T cells in our melanoma lung metastases mass cytometry data and found that Ly6a was highly expressed on CD62L−/CD44+/PD1+ T cells (Fig. 4e), suggesting that these cells are effector or effector memory or exhausted subpopulations of T cells.

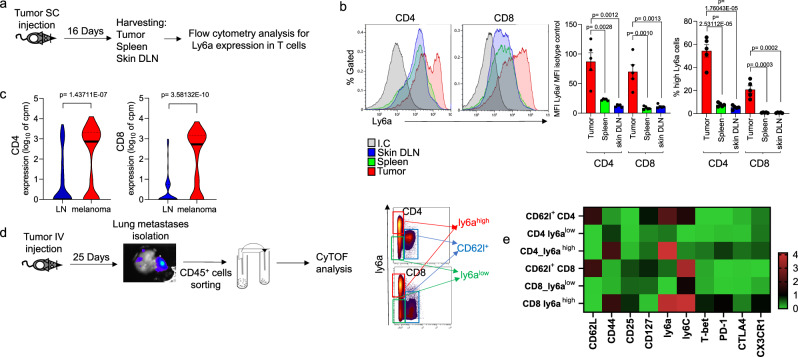

Fig. 4. Ly6ahigh T cells are enriched in the tumor microenvironment independently of UVB exposure.

a Experimental flowchart. b Left: Representative flow cytometry analyzes of Ly6a expression levels in CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T cells from inguinal lymph nodes, spleens, and tumors. Right: MFI of Ly6a normalized to isotype control (left) and percentage of Ly6ahigh cells in total CD4+ or CD8+ compartments (right) (n = 5 per condition). c Violin plots of Ly6a expression in CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) cells in lymph nodes and tumors. Single-cell RNA-seq data from Davidson et al.30. d Experimental flowchart: Melanoma metastases were isolated from mouse lungs, and CD45+ cells were isolated and analyzed using CyTOF. CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells are divided into three groups: CD62l+ (blue gate), Ly6ahigh (red gate), and Ly6alow (green gate). e Heatmap of median expression levels of T cell markers in indicated cells. The colors reflect the transformed ratio relative to the minimum expression of the marker (n = 4 per group). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA test with Tukey correction (b) or two-tailed t test (c). n.s. not significant. Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The increase in Ly6a expression in the tumor microenvironment may be due to TCR-dependent activation that occurs when T cells recognize tumor cells, in which case Ly6a represents a marker of activated or exhausted T cells. On the other hand, it is also possible that the high levels of Ly6a expression on TILs is related to the inflammatory environment induced by tumor cells and by myeloid cells that migrate to the tumor. To test these possibilities, C57BL/6 J OT-1 mice were subcutaneously injected with B16-OVA melanoma cells, which are recognized by the TCR of the OT-1 T cells, or with B16 melanoma cells that are not recognized by the T cells of these mice. There was no difference in the level of Ly6a in the TILs of B16 and B16-OVA tumors; in both groups of mice, levels of Ly6a were higher in tumors than in T cells of the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

We further examined the Ly6a levels in TILs that did or did not express the OVA tetramer by challenging C57Bl/6 and OT-I mice with B16-OVA melanoma cells injected subcutaneously. Once tumors were palpable, we analyzed the infiltrating CD8+ T cells for their expression of Ly6a and the OVA tetramer. We found that approximately 20% of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells that were positive for the OVA tetramer expressed high levels of Ly6a (Supplementary Fig. 4d). This is equivalent to the percentages of Ly6a+/CD8+ T cells that infiltrated tumor tumors in control mice (Supplementary Fig. 4c) This indicates that the increase in Ly6a is not restricted by the TCR specificity, but probably results from the inflammatory environment of the tumor supporting our hypothesis that Ly6a is a marker of T cells that have been exposed to an inflammatory or an immunosuppressive environment that could result from chronic UVB exposure or cancer.

Anti-Ly6a antibody has a strong immunotherapeutic effect even in mice resistant to anti-PD1 antibody treatment

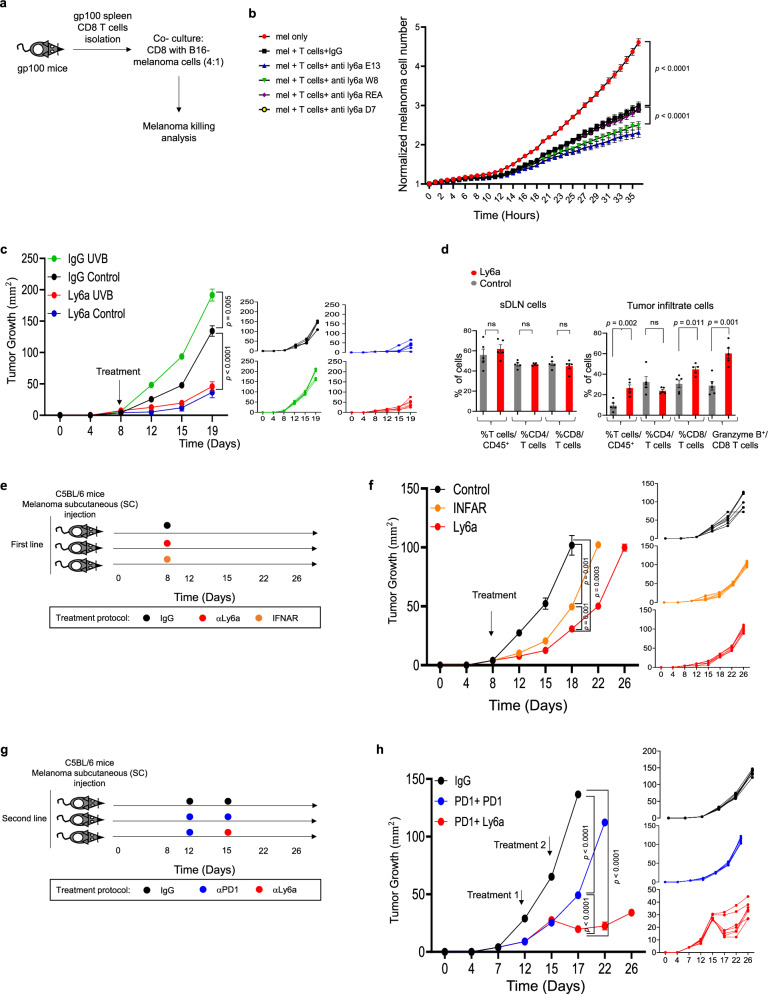

Our findings that Ly6a is a marker of T cell in the tumor microenvironment, together with the finding that chronic UVB suppressive effect on T cells in response to cancer is associate to Ly6a increase, motivate as to examine the function of Ly6a in the T cell response to cancer, we first evaluated the effect of anti-Ly6a antibodies on CD8+ T cell killing ability in vitro. Since the antibody effect is highly dependent on the epitope bound by the antibody, we used four different anti-Ly6a antibody clones. We performed the in vitro killing assay by co-culturing CD8+ T cells from spleens of gp10025,28–35 TCR transgenic mice36 with B16 melanoma cells (Fig. 5a). The anti-Ly6a antibodies all significantly enhanced killing of melanoma cells; clones E13.161 and W18174A were considerably more active than clone D7 or clone REA422 (Fig. 5b). We found that IFNα treatment of T cells did not enhance T cell killing ability in vitro but that there was a significant additive effect when cells exposed to IFNα were also treated with anti-Ly6a antibody (Supplementary Fig. 5a). This suggests that Ly6a treatment may have a strong effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells that express high levels of Ly6a.

Fig. 5. Anti-Ly6a antibody has a strong immunotherapeutic effect even in mice resistant to anti-PD1 antibody treatment.

a Experimental flowchart. b Normalized mean numbers of B16F10 melanoma cells following co-culture with splenic CD8+ T cells from transgenic mice bearing gp100-reactive T cells in the presence of various clones of anti-Ly6a antibody or IgG control (n = 10 per group). c Mean tumor diameters (left) and data from individual mice (right) treated with UVB or mock-irradiated (control) and injected subcutaneously with Ret melanoma cells then treated with anti-Ly6a antibody or IgG control. Arrow indicates time of antibody injection (n = 6 per group). d Mean percentages of Granzyme B expression in tumor-infiltrating (left) or sDLN (skin Drained Lymph Nodes) (right) CD45+ cells (n = 5 per group). e Experimental flowchart. f Mean tumor diameters (left) and data for individual mice (right) injected with Ret melanoma cells and treated with anti-IFNR1, anti-Ly6a, or IgG (control) antibodies. The arrow indicates the day of treatment. (n = 6 per group). g Experimental flowchart. h Mean tumor diameters (left) and individual data (right) for mice injected with Ret melanoma cells and treated with anti-PD1, anti-PD-1, anti-Ly6a, or IgG (control) antibodies (n = 6 per group). Arrows indicate days of treatment. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA test with Tukey correction (b, c, f, h) or two-tailed t test (d). Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we examined the potential of anti-Ly6a-antibody as an immunotherapy treatment in vivo. For these experiments, we used an established in vivo model of cancer response to immunotherapy31,36. We subcutaneously injected MC38 colon cancer cells or Ret melanoma cells into C57BL/6 J mice, followed by two intraperitoneal injections of anti-Ly6a antibody. Remarkably, injection of clone E13.161 significantly inhibited the growth of tumors and improved the survival of the treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Clone W18174A was also active, whereas clone D7, which binds to a different epitope of the Ly6a protein37, had no inhibitory effect on tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These data indicated that anti-Ly6a antibody has an anti-cancer effect that is epitope specific.

Next, we tested the potential of anti-Ly6a antibody in the context of UVB-induced tumor suppression in vivo. Mice were exposed to UVB or were mock irradiated for 8 weeks. Post irradiation, 2 × 105 Ret melanoma cells were injected subcutaneously. Once tumors were palpable, mice were injected intraperitoneally twice a week with anti-Ly6a antibody (clone E13 161-7) or with anti-IgG2a as a control. Treatment with anti-Ly6a antibody significantly inhibited tumor growth in mice that were exposed to UVB and in those that were mock irradiated (Fig. 5c). The inhibitory impact of the anti-Ly6a antibody on tumor growth after UVB treatment was associated with an elevation in activated CD8+ cells within the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Fig. 5d). This was in sharp contrast to the effect of anti-PD1 antibody, which did not reduce tumor growth following chronic exposure to UVB (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Fig. 5e). Thus, anti-Ly6a treatment hinders the accelerating effect of UVB-induced immunosuppression on tumor growth.

Given that chronic exposure of CD8+ T cells to type 1 IFN induces Ly6a expression (Fig. 3), we next tested whether IFNAR blockade phenocopies anti-Ly6a antibody treatment. We challenged mice with Ret melanoma cells and the treated the mice with anti-IFNAR-1 or anti-Ly6a antibodies. Like anti-Ly6a antibody treatment, INFAR-1 blockade significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to control IgG injection (Fig. 5f).

Finaly, in mice with established Ret melanoma tumors, the anti-Ly6a antibody was more effective as a second-line treatment after partial response to anti-PD1 antibody than were additional cycles of anti-PD1 antibody (Fig. 5g). Taken jointly, our results show that anti-Ly6a antibody treatment enhances the immune response to cancer even in tumors resistant to anti-PD-1 antibody. This suggests that anti-Ly6a antibody treatment has the unique immunotherapeutic effect that modulates T cell phenotype and relieves suppression of T cell killing ability.

Anti-Ly6a antibody treatment enhances CD8+ T cell activity and prevents loss of mitochondrial function through effect on cMyc-mediated signaling

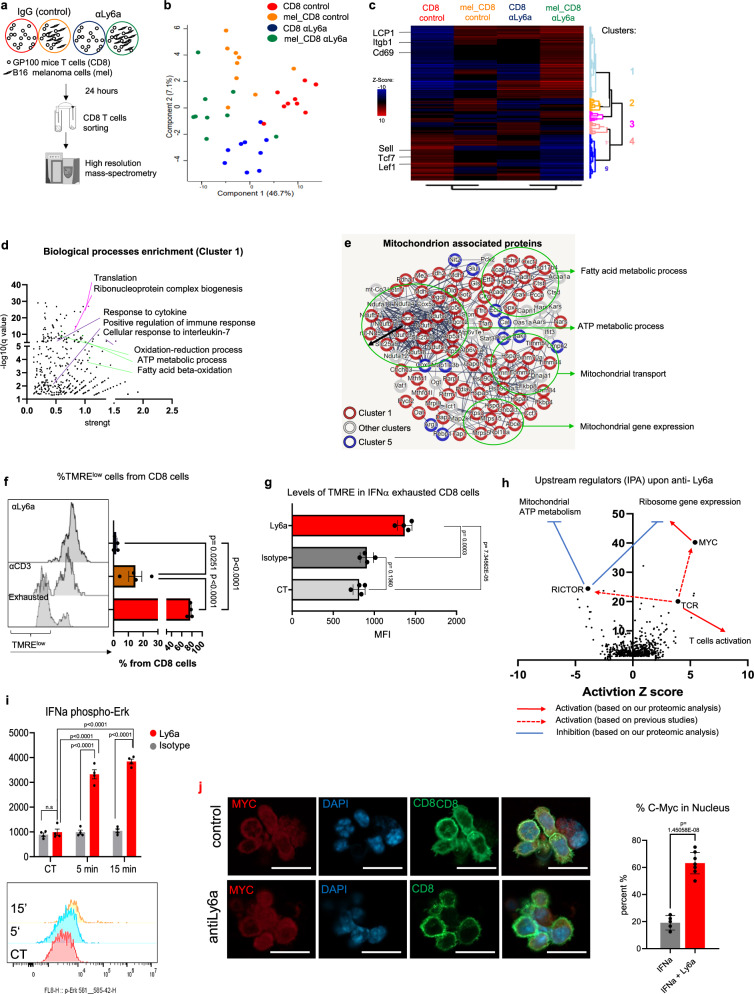

To evaluate the downstream effects of anti-Ly6a antibody treatment, we examined the effect of anti-Ly6a antibodies on CD8+ T cell activity in the presence and absence of tumor cells using a high-resolution mass spectrometry proteomic analysis. Spleen cells were isolated from gp10025,28–35 TCR transgenic mice and incubated for 3 days with IL-2, IFNα, and gp10025,28–35 peptide. Next, CD8+ T cells were isolated and incubated overnight with anti-Ly6a antibody (clone E13.161) or IgG with or without B16F10 melanoma cells. CD8+ T cells were then sorted and subjected to proteomic analysis (Fig. 6a). Of the 4202 identified proteins, 588 were significantly different between groups (Supplementary Data 4). Principal component analysis indicated that the proteome profiles of CD8+ T cells after Ly6a crosslinking markedly differed from the profile of IgG-exposed cells both in the presence and in the absence of melanoma cells (Fig. 6b). Unsupervised clustering of the significantly different proteins revealed five clusters indicative of the effect of anti-Ly6a antibody on CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6c). The largest cluster, cluster 1, includes proteins that were significantly upregulated upon anti-Ly6a antibody treatment compared to those treated with IgG. Among the 269 proteins of cluster 1, we found T cell activation markers such as CD69, Lcp-1, and Itgb2 (Fig. 4e). The next largest cluster, cluster 5, includes proteins with decreased expression upon anti-Ly6a antibody treatment such as the transcription factors Lef1 and Tcf7, known to be expressed in naïve T cells38, and CD62L (encoded by Sell), which is downregulated upon T cell activation39 (Fig. 6c; Supplementary Data 4). Further, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis indicated that cluster 1 proteins were enriched in factors involved in translation and ribosome biogenesis (Fig. 6d; Supplementary Data 4), two well-established indicators of T cell activation40. Interestingly, we found that anti-Ly6a antibody treatment significantly increased the levels of multiple proteins associated with mitochondrial metabolism, especially ATP metabolic process and fatty acid oxidation (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Data 4). Enrichment of factors involved in mitochondrial functions such as ATP production by cellular respiration, mitochondrial gene expression and fatty acid metabolism was observed specifically in cluster 1 (Fig. 6e; Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Thus, treatment of T cells with the anti-Ly6a antibody induces two processes: Although not necessarily opposed, their co-presence is somewhat surprising: On one hand, the expression of classical markers of T cell activation, including upregulation of ribosomal proteins and CD69 and downregulation of CD62L, (Fig. 6c). On the other hand, the antibody also caused increased mitochondrial activity (Fig. 6c–e and Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), a metabolic process that is expected to decrease during T cell activation, which is associated with increased anaerobic glycolysis41.

Fig. 6. Anti-Ly6a antibody treatment enhances CD8+ T cell activity and prevents loss of mitochondrial function through effect on cMyc-mediated signaling.

a Experimental flowchart. b Principal component analysis of the proteins that significantly changed across indicated conditions (n = 9 per condition). c Heatmap of the average Z scores for each group. Selected proteins in cluster 1 and cluster 5 are indicated. d GO terms significantly associated with proteins of cluster 1. Shared colors indicate related GO terms. e String protein networks of significantly changed proteins in all samples that are associated with the GO term “mitochondrion”. Selected GO terms are indicated. Clusters are indicated by circle colors (red and blue). f Representative flow cytometry (left) and mean percentages (right) of TMRE expression in CD8+ cell (n = 4 per condition). g MFI of TMRE expression in IFNα exhausted CD8+ T cells (n = 3 per group). h Predicted upstream regulators of the significantly changed proteins in all samples. Arrows represent the predicted effect of anti-Ly6a crosslinking. i Mean intensity (upper) and representative flow cytometry (lower) of phosphorylated Erk1/2 in CD8+ T cells incubated with anti-Ly6a antibodies (n = 5 per group). j Representative confocal images (left) and mean percentages of T cells with nuclear c-Myc (right) following exhaustion with IFNα and incubation with anti-Ly6a antibodies (n = 10). Shown is one representative experiment out of at least three independent experiments performed. The scale bar is 20 µM. Statistical significance was calculated using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons (f, g, i, j) or FDR correction with FDR < 0.1 significant (c, d). n.s. not significant. Error bars represent standard errors. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Examination mitochondrial activity analysis using tetra-methylrhodamine ester (TMRE), a dye sensitive to membrane potential that is indicative of the mitochondrial activity level, showed that in contrast to anti-CD3 antibody-activated T cells or exhausted T cells, anti-Ly6a antibody-treated cells had high mitochondrial activity (Fig. 6f). Further, incubation of CD8+ T cells with anti-Ly6a antibody rescued T cells from exhaustion and deactivated mitochondria (Fig. 6g). These findings support the hypothesis that anti-Ly6a antibody not only activates T cells to enhance their cytotoxicity but also reprograms T cell metabolism to favor mitochondrial activity.

Since we saw markers of activation without the expected decrease in mitochondrial function, we sought to identify the specific pathways that mediate the downstream effects of anti-Ly6a antibody. First, we test whether anti-Ly6a antibody directly impacted TCR-mediated signaling. We found no change in Zap70 phosphorylation in cells treated with both anti-CD3 antibody and anti-Ly6a antibody compared to anti-CD3 antibody treatment alone (Supplementary Fig. 6c). This indicates that anti-Ly6a antibody does not directly influence signaling mediated by the TCR; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that Ly6a may modulate some of the downstream effects of TCR activation.

Next, we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to predict upstream regulators of the effect of the anti-Ly6a antibody on T cell function. We found that Myc, a transcription factor that upregulates multiple metabolic pathways upon T cell activation42, was the most significant upstream regulator (Fig. 6h). Myc-deficient T cells have impaired proliferation upon TCR activation and rapidly differentiate toward an exhaustion phenotype in the tumor microenvironment due to mitochondrial defects41. One of the copartners of Myc is Rictor, a subunit of the mTOR complex 2, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolic activity upon T cell activation43. Rictor-deficient CD8+ cells have enhanced mitochondrial metabolic activity but their effector function is not inhibited43. Rictor was predicted to be an upstream regulator of Ly6a (Fig. 6h). Chronic TCR activation may enhance Rictor activity leading to exhaustion via loss of mitochondrial activity. Anti-Ly6a antibody inhibited Rictor expression. Taken together, our proteomic analysis suggests that anti-Ly6a crosslinking reprograms metabolic pathways in CD8+ T-cells via Myc induction together with mTOR complex 2 inhibitions, which may enhance the metabolic fitness of CD8+ T-cells and prevent loss of mitochondrial activity that is associated with T-cells exhaustion. Further, incubation of CD8+ T cells with anti-Ly6a antibody induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and mobilization of Myc from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Fig. 6i, j). These data are consistent with the function of the Erk-Myc axis in mitochondrial metabolism44.

Intersection of our proteomic data with a proteomic analysis of T cells treated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies45, revealed the unique effect of anti-Ly6a antibody on T cells: The anti-Ly6a antibody enhanced mitochondrial metabolism, which does not result from TCR activation (Supplementary Fig. 6d–f). In summary, our results indicate that Ly6a increase in T cells following chronic UVB or in the tumor microenvironment, is not only a marker of chronic type 1 interferon inflammatory condition, but also a target that opposite T cells immunosuppression. The unique effect of anti Ly6a may use as a model for immunotherapy treatment that, independently to T cells activation via TCR, can enhance T cells metabolism and cancer cells killing ability.

Discussion

Although the suppressive effects of UVB on the immune response to cancer have been known for several decades2,3, little research has been conducted on how UVB specifically impacts the killing ability of CD8+ T cells, and there have been no investigations into how UVB influence the response to immunotherapy. We discovered that UVB irradiation impaired the tumor killing ability of T cells from sDLN. Moreover, UVB reduced the frequency of CD8+ TILs during anti-PD1 immunotherapy and thus caused resistance to this treatment. Our UVB model therefore provided an opportunity to identify factors that suppress the T cell response to cancer independently of PD1-mediated signaling.

Our comprehensive investigation of the effects of UVB on both systemic and local compartments of the immune system revealed three significant effects that specifically influence sDLN immune cells. Two effects, the increase in DC percentage and the increase of inflammatory monocytes percentage, are recognized known UVB immunosuppressive and inflammatory mechanisms8,29. However, we revealed a third effect, the upregulation of Ly6a expression in T cells. Our single-cell RNA sequencing analysis revealed that the upregulation of Ly6a expression following UVB exposure was accompanied by a significant enhancement of the type 1 IFN gene signature on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The association between UVB and type 1 IFN secretion has been previously demonstrated in both mice and humans46,47. However, the link between UVB-induced type 1 IFN gene expression and UVB-induced immunosuppression has not been previously studied. Induction of type 1 IFN expression by UVB exposure appears to promote an inflammatory response: For example, autoimmune symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus worsen after UVB exposure48. However, there is also evidence suggesting that chronic exposure to type 1 IFNs has the opposite effect, contributing to the suppression of T cell responses to viruses and cancer49,50. Our finding that Ly6a, which was induced by type 1 IFNs, can be targeted to inhibit UVB-induced immunosuppression and to enhance the immune response to cancer indicates that the inflammatory effect of UVB and the immunosuppressive effect of UVB are not distinct phenomena but rather mutually influence each other.

Independently of UVB treatment, we observed high Ly6a levels on T cells within the tumor microenvironment. These high levels resulted from chronic exposure to factors from the tumor microenvironment rather than from TCR activation. Thus, similar to the effect resulting from UVB exposure, type 1 IFNs secreted by cells of the tumor microenvironment contribute to the increase in Ly6a. A previous study demonstrated that IFNγ and IL-27 modulate the expression of Ly6a on T cells in a parasitic protozoan25, so we cannot exclude the possibility that cytokines such as IL-27 and IFNγ also contribute to the induction of Ly6a expression in the tumor microenvironment. Type 1 IFN is an activator of T cells during acute viral infections; however, when chronically present, it suppresses the T cell response to viruses and tumors49,50. Further, high levels of expression of IFN signature genes on T cells are correlated with a lack of response to immunotherapy51. We found that CD8+ T cells that are chronically exposed to IFNα can be activated by antibodies against Ly6a, suggesting opportunities for the development of new immunotherapy treatments.

Since the endogenous ligand of Ly6a is not known and the uncertainty surrounding its human homolog, it is currently not possible to fully analyze the biological role of Ly6a. Nonetheless, several of our findings strongly suggest that anti-Ly6a antibody does not block its interactions with a ligand. First, incubation of CD8+ T cells with the antibody induces expression of activation markers such as CD69 and ribosomal proteins and elevates the metabolic and mitochondrial activity of CD8+ T cells. Second, incubation of CD8+ T cells with anti-Ly6a antibody rescued T cells from exhaustion, deactivated mitochondria, induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2, and induced mobilization of Myc from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. These data suggest that the influence of anti-Ly6a antibody on CD8+ T cells does not depend on the presence of a ligand found on other cells of the immune system or on cancer cells.

The mechanism by which T cells are activated by anti-Ly6a antibody exemplifies the capacity to trigger T cell responses independently of TCR signaling. Recently, there is increasing evidence suggesting that even TILs not specifically targeting tumors can exhibit activity against cancer cells. Bystander activated T cells possess the ability to recognize and eliminate cancer cells in a manner reminiscent of innate immunity52. The potential of an antibody targeting Ly6a to augment the immune response, even in cases of anti-PD1 resistance, is linked to this distinctive mechanism. We anticipate that the capability to activate TILs independently of TCR signaling will complement existing immunotherapies, offering a promising approach for treating patients with resistance to current immunotherapy treatments.

Methods

All experiments were conducted under the ethical supervision and approval of Tel Aviv University (01-20-033, 01-19-086, and TAU-MD-2405-134-5).

Mice

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Tel Aviv University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee using approved protocols (IACUC permits: 01-20-033 and 01-19-086). Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions under 12 h dark/12 h light conditions at 22 ± 1 °C and 32–35% humidity with ad libitum water and food. C57BL/6 mice aged 7–8 weeks old were purchased from Envigo and were allowed to acclimatize for one week after arrival. OT1 TCR C57BK/6 CD45.1+ mice expressing the T cell receptor that recognizes ovalbumin peptide (amino acids 257–264) were a kind gift from Professor Steffen Jung (Weizmann Institute of Science). gp100 mice expressing the transgenic Pmel 17 TCR36 were a kind gift from Professor Michal Lotem (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem).

UVB treatment

Seven to eight-week-old C57BL/6 J female were habituated for 7 days prior to experiment initiation and dorsally shaved 2 days prior radiation exposure. Mice were exposed to UVB 5 days/week for a period of 8 weeks in a reverse light setting with a XX-15 stand equipped with 15-W, 302-nm UVB bulbs (Ultraviolet Products). The dose of UVB was increased gradually to mimic the protocol used for human UVB phototherapy53. Starting at an initial dose of 50 mJ/cm2, a sub-erythematic dose in this mouse strain54, the UVB dose was increased by 30% at each treatment, reaching a final dose of 200 mJ/cm2. UVB emission was measured using a UVX radiometer (Ultra-Violet Products) equipped with a UVB-measuring head. Mock-irradiated mice were shaved and placed in the radiation chamber for an equal amount of time. Mice were re-shaved once a week if there were patches of fur regrowth.

In vivo tumor growth models

All the animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the Tel Aviv University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (#01-21-046). For in vivo tumor growth, cultured tumor cells suspended in PBS at 2 × 105 cell/50 µl for MC38 and B16 cells, 1 × 106 cells/50 µL for B16-OVA cells (in Supplementary Fig. 4b) 2 × 105 cells/50 µL for Ret melanoma cells in Fig. 1 experiments and 1 × 106 cells/50 µL for Ret melanoma cells in Fig. 5 experiments (for partial resistance to anti-PD-1), and were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) for subcutaneous injection. An aliquot of 100 µl was injected subcutaneously into the shaved area on the dorsal side of the mouse. The height and width of the subcutaneous tumors were measured twice a week using calipers. Tumor size was calculated as square dimeter (in mm2). Tumor volume was calculated as the (length × width2) /2. Mice were sacrificed when the tumors reached 200 mm2. To induce lung metastases, RetmChery+luciferase+ melanoma cells were suspended in PBS (5 × 105 cells/100 µL), and an aliquot of 100 µl was injected into the tail vein. This line is widely used in melanoma models and induces spontaneous melanoma progression that resembles human melanoma in its progression, metastases potential, melanotic level, and immunogenicity. It results in the activation of MAPK and cJun signaling, which are downstream of the Ret oncogene16–18. Lung tumors were quantified twice a week by in vivo imaging beginning on day 7 after injection. For in vivo imaging, mice were anesthetized using 2.5% isoflurane and administered 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (Biovision) by intraperitoneal injection. Ex vivo imaging of the lungs and liver was performed after sacrifice and pulmonary artery perfusion. The average radiance (photons/s/cm2/sr) was calculated using an IVIS Lumina III system (PerkinElmer).

Survival curve

Mice were subcutaneously injected as described before. When the tumor reached 1.5 cm3 in volume, mice were sacrificed as per the ethical approval. The sacrifice date was taken into survival curve analysis. Significance was determined using the two-tailed long-rank test.

In vivo immunotherapy treatment

Mice were injected intraperitonealy with 200 µg of anti-PD1 (RMP1–14, BioXCell), 200 µg of rat IgG2a isotype control (BioXCell), or 100 µg anti-Ly6a (clone D7, E13.161, or W18174A; Biolegend) as indicated.

Cell culture

B16F10 melanoma cells, Ret melanoma cells, and MC38 colon cancer cells were cultured in RPMI (Biological Industries), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine (Biological Industries). Generation of Ret melanoma cells, which stably express mCherry and luciferase, was conducted by transfecting the PLKO-mCherry-luc-puro plasmid (Addgene) into the ReT-cells using the jetPEI DNA transfection reagent (Polypus). After 48 h, the stable clones were selected by culture in puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, 10 µg/ml). All cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Primary cell isolation

Spleen and lymph node were homogenized in Hank’s balanced salt solution (Gibco) supplemented with 2% FBS and 5 mmol/L EDTA and were isolated through a 70-μm strainer (Corning). Tumors were digested in RPMI 1640 with 2 mg/mL collagenase IV, 2000 U/mL DNase I (Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min at 37 °C and then homogenized and strained through a 70-μm strainer.

For killing assays, mononuclear layers were collected from splenocyte suspensions using Ficol Histopaque®−1077 (Sigma Aldrich), washed by adding 10 mL of RPMI 1640 medium and centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 18 °C. The pellet of spleen mononuclear cells or the pellet of sDLN cells was re-suspended in MACS buffer (0.5% BSA, 2 mM EDTA in PBS). CD8+ T-cells enrichment was conducted using CD8 mouse magnetic MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD4+ and CD8+ cells were enriched by negative selection using Pan T-cells Isolation Kit II, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec). CD11b+ cells were isolated using magnetic CD11b MicroBeads and column (both from Miltenyi Biotec). Ly6anegative/low T-cells were sorted from spleen mononuclear cells using FACS (BD FACSAria III, BD Biosciences). Working dilutions/concentrations for all antibodies were according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro killing assay

Spleen and lymph node cells of OT-1 mice were isolated post 8 weeks of UVB radiation 5 days a week (Fig. 1) or spleen cells of gp100 mice (Fig. 5) were activated with OVA peptide or gp100 peptide and with IL-2 (100 IU/mL; PeproTech) for 48 h. After activation, CD8+ cells were isolated as described above and cultured for 48 h with IL-2 (200 IU/mL; PeproTech). CD8+ T-cells were co-cultured with B16-OVA (4:1). Melanoma cells were also cultured alone. Cultures were treated with antibodies to Ly6a, clones D7, E13.161, or W18174A (Biolegend) or REA422 (Miltenyi Biotec), Ly6e (EB10216, Everst Biotech), or rat IgG2a isotype control (BioXCell) at concentrations of 10 µg/ml or as indicated. The percentage of cells positive for caspase-3/7 (clone #C10423, Invitrogen; dilution used 1:1000) was determined after 24 h. The number of melanoma cells was normalized to the number of melanoma cells in each well at time 0. Analysis was performed using the IncuCyte® Live Cell Analysis System (Sartorius). Samples were also analyzed after 24 h using flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Colter) for the percent of CD45−/CD8−/caspase-3/7+/DAPI+ cells from total CD45−/CD8− cells in the wells.

Flow cytometry

Cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Colter) and sorted by FACS (BD FACSAria III, BD Biosciences). Datasets were analyzed using Kaluza software (Beckman Colter). Intracellular flow cytometry as performed using Miltenyi Biotec fixation buffer and permeabilization buffer according to the manufacture protocol. The following antibodies were used: CD4-FITC, mouse (IgG2bκ, Miltenyi Biotec), CD8-APC-VIO770 APC (REA734, Miltenyi Biotec), CD11b-PE (REA592, Miltenyi Biotec), Ly6c-APC (REA796, Miltenyi Biotec), Ly6g-FITC (REA526, Miltenyi Biotec), CD3-VioBlue (BW264/56, Miltenyi Biotec), CD45 APC (REA737, Miltenyi Biotec), Ly6A-PE (REA422, Miltenyi Biotec), CD44 APC (REA664, Miltenyi Biotec), MHC2 APC (M5/114.15.2, Biolegend), CD11c (N418, Biolegend), FoxP3 Alexa fluor 647 (MF-14, Biolegend), CD25 BV650 (PC61, Biolegend), REA control antibody- PE (isotype control, REA293, Miltenyi Biotec), CD69 (clone REA937) and CD62L (clone MEL14-H2.100).H-2Kb:OVA (SINFEKEL) tetramers conjugated to APC were purchased from MBL (Woburn, MA). Anti-phopho-Erk1/2 (clone 6B8B69, Biolegend). Working dilutions/concentrations for all antibodies were according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Mass cytometry analysis

High-throughput mass cytometry analyzes were performed as previously described55. Briefly, sDLN cells or splenocytes were isolated, fixed, and permeabilized with 100 µl of 2% PFA in CyPBS and eBioscience perm buffer and then stained with metal-tagged antibodies to intracellular markers. All antibodies were conjugated using the Maxpar® reagent (Fluidigm). The antibodies used are described in Supplementary Data 1. Rhodium and iridium intercalators were used to identify live/dead cells. Cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 1.6% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), and then washed with H2O. Data were acquired using a CyTOF mass cytometry system (Fluidigm) and uploaded to the Cytobank web server. CD45+ live cells were analyzed, and the gated cells were segregated into subpopulation clusters by expression markers. Data analysis was performed using UMAP56 and FlowSOM57 algorithms for unsupervised analysis and a traditional flow cytometry gating strategy for supervised analysis on the Cytobank server. After removal of dead cells, CD45− cells, and low-quality events, we separately analyzed the major immune cell populations (T cells, B cells, and other cells). Each population was analyzed separately using only markers relevant for each cell type (Supplementary Data 1). Results of one algorithm were not used as an influencing factor in the analysis by the other algorithm; however, the number of clusters in the FlowSOM analysis was determined by the number of separate populations observed after reducing the dimensions in the UMAP algorithm. There were 6 clusters for CD4+ T cells, 6 for CD8+ T cells, 5 for B cells, and 12 for all other cells.

In vitro cytokine treatment

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, isolated from C57BL/6 J mouse spleens, were treated with the 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 (clone 17A2, BioLegend), 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD28 (clone 37.51, Biolegend), anti-LEAF (BioLegend), LPS (Invivogen), or CL307 (TLR7 agonist, Invivogen) or with IFNα, IFNγ, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, TNFα (10 ng/mL; Miltenyi Biotec) or IL-2 (1000 IU/mL; PeproTech). After 24 h, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for Ly6a.

US and IVIS imaging of tumor growth

Ultrasound measurements were performed using a portable ultrasound device (Mindray M9, Shenzhen Mindray Bio-medical Electronics). The ultrasound transducer was placed on the tumor center, and the tumor depth measurement was performed. Doppler imaging was used to evaluate blood flow within the tumor area. Ex vivo imaging of lungs and liver was performed after sacrifice and pulmonary artery perfusion using D-luciferin. The bioluminescence signals were detected using an IVIS Lumina III system (PerkinElmer).

RNA purification and quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to quantify mCherry mRNA for detection micro metastases as described before58. Lymph nodes and liver were homogenized, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA was produced using the cDNA SuperMix kit (QuantaBio) and then subjected to qRT-PCR using the Blue SYBR low ROX kit (PCR Biosystems). mRNA levels were normalized to endogenous actinβ. Naïve lymph nodes and liver were used as negative controls. The qRT-PCR primers were mCherry forward, 5′-GAACGGCCACGAGTTCGAGA-3′; mCherry reverse, 5′-CTTGGAGCCGTACATGAACTGAGG-3′; actinβ forward, 5′-CTGTCCCTGTATGCCTCTG-3′; and actinβ reverse, 5′-ATGTCACGCACGATTTCC-3′. For the other genes we used these primers: 36B4 forward, 5′-GATGATCAAAGGGATGTGGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCTCGGCAACAGACTCTTC-3′.

RNA and single-cell RNA sequencing dataset analyzes

Single-cell RNA sequencing data of CD4+ cells from spleens of young and old mice28 were used for the analysis of Ly6a expression in CD4+ cell subsets. We used this dataset because of the deep separation of the CD4+ cells into seven different subsets. The read counts were downloaded from https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell, normalized as described in the original analysis. (The expression level of a gene was divided by total expression of all genes in that subset and multiplied by 10,000. This product was log-transformed (base e) after the addition of a pseudocount of 1). For analysis genes co-expressed with Ly6a in effector memory and exhausted CD4+ T cells, we segregated the cells defined in the metadata of the original analysis as effector memory (2181 cells) or exhausted (1841 cells) according to Ly6a expression levels and compared the expression level of each gene in Ly6aneg cells to Ly6ahigh cells (defined as level of Ly6a is more than the median expression of cells with any level of Ly6a.

Proteomics

Samples were prepared by sorting 12,000 CD8 T-cells (>98% purity) into separate wells in a 96 wells plate (Eppendorf twin.tec® PCR Plates) containing 33 ul of lysis buffer [composed of 2% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 20 mM Tris(2‐carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP), 80 mM Chloroacetamide (CAA)] and the total volume was completed with 100 mM HEPES solution (pH= 8.5). After sorting, the plates were spun to enable proper mixing between the cells and the lysis buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Further sample preparation was based on the SP3 protocol59, which is suited for samples with low protein amounts. The first stage of the protocol was done using the Bravo Automated Liquid Handling Platform (Agilent) and the second stage was done manually. Briefly, magnetic beads (SeraMag magnetic beads; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to the samples, followed by the addition of ethanol (final concentration 50%), and incubated to allow binding of the proteins to the beads. Beads were then washed twice with ethanol using a magnetic rack and incubated for overnight digestion with trypsin (Promega). Thereafter, the samples were transferred to clean lobind tubes and fresh beads were added with the addition of acetonitrile (ACN) to promote the attachment of peptides to the beads. Samples were washed once more with ACN using a magnetic rack. Finally, to release the peptides from the beads, 2% DMSO (in water) was added. Samples were then collected in lobind tubes. ~3 µl of each sample were loaded directly into Evotips (Evosep) for proteomic analysis. All reagents are LC-MS grade.

For all other proteome analyses, we used an EvoSep One liquid chromatography system60 and analyzed with a 40 SPD gradient. We used a 15 cm nanoflow UHPLC packed emitter column with nanoZero® technology, compatible with Bruker CaptiveSpray source. (Ion optics). Mobile phases A and B were 0.1% FA in water and 0.1% FA in ACN, respectively. Mass spectrometric analysis was performed in a data-independent (dia) PASEF mode. Raw files were analyzed with DIA-NN61 (version 1.8) using default settings (e.g., 1% precursor and protein FDR), except, enabling MBR, and quantification strategy to robust LC (high precision), and library generation to IDs, RT, and IM profiling using the Uniprot Mus musculus proteome. The DIA-NN protein group data output was filtered first for at least 70% in at least one group (out of 4), imputed, and then quantile normalized. Data were analyzed through the use of IPA (QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity- pathway-analysis) using upstream analysis and STRING analysis at https://stringdb.org/ as indicated in the results.

Immunofluorescence of cells

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed with 1.8% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at RT, and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X. Cells were then washed, blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 10% goat serum and 5% BSA and stained overnight with primary antibody to anti-MYC antibody (clone 9E10, Abcam) at 4 °C. Cells were stained for nuclear staining with DAPI (vector laboratories) and imaged under Zeiss800 confocal microscope and MYC nuclear localization was analyzed by Zen Blue software. Working dilutions/concentrations for all antibodies were according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Single Cell RNA-sequencing

Library preparation

10 μL of sorted cells were stained with Trypan Blue and counted using a hemocytometer and optical microscope. Cells were then centrifuged at 300 G for 5 min, resuspended into sorting medium at concentration of 1000 cells/ μL. Cells were encapsulated into droplets, and libraries were prepared using Chromium Single Cell 30 Reagent Kits v3 according to manufacturer’s protocol (10 × Genomics). The generated single-cell RNA-seq libraries were sequenced using a 75 cycle NextSeq 500 high output V2 kit.

Droplet-based single-cell RNA-Seq data processing

FASTQ files were created using CellRanger mkfastq function (v7 10×Genomics)62. Gene counts were obtained by aligning reads to the mm10 genome using CellRanger count function. To remove doublets and poor-quality cells, we excluded cells that: Contained more than 25% mitochondrially-derived transcripts. Contained less than 200 or more than 5000 genes detected. Contained less than 200 or more than 25,000 detected molecules. The filtering process yielded 33,703 cells. Four samples of lymph nodes from control mice and 3 samples of lymph nodes of UV treated mice were merged and transcript counts were normalized and scaled using the NormalizeData ScaleData functions in Seurat 4.3.263 R package, which normalizes scales, and centers features in the dataset. For principal component analysis (PCA) and clustering, we used a log-transformed expression matrix. Variably expressed genes were used to construct principal components (PCs) and PCs covering the highest variance in the dataset were selected. The selection of these PCs was based on an elbow plot.

Single-cell RNA-seq clustering

Clusters were calculated by the FindClusters function with a resolution between 0.25 and 0.35 and visualized using the t-SNE dimensionality reduction method. The FindClusters function in Seurat was used to identify clusters of cells by a shared nearest neighbor (SNN) modularity optimization-based clustering algorithm. First, we calculated the k-nearest neighbors and constructed the SNN graph. To generate tSNE plots of single cell profiles, we used the Seurat’s RunTSNE function.

Genes differentially expressed between clusters

The FindAllMarkers Seurat function was used to find marker genes that were differentially expressed between clusters. This function identifies differentially expressed genes between two groups of cells using a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with limit testing chosen to detect genes that display an average of at least 0.25-fold difference (log-scale) between the two groups of cells and genes that are detected in a minimum fraction of 0.25 cells in either of the two populations.

Visualization of single-cell data

To generate both CD4 and CD8 tSNE plots, the scores along the 13 or 15 significant PCs described above were used as input for the R implementation of tSNE, by the RunTSNE Seurat function. Specific gene expressions were visualized over the tSNE using FeaturePlot Seurat function and some genes were visualized using the VlnPlot Seurat function.

Single-cell gene signature scoring

Single-cell gene signature scoring was done as described previously64. Briefly, as an initial step to remove the bias towards highly expressed genes, the data was scaled using a z-score across each gene. For a given gene signature (list of genes), a cell-specific signature score was computed. Scores were computed by first sorting the normalized scaled gene expression values for each cell, followed by summing up the indices (ranks) of the signature genes. The same method was also applied to gene signatures, which include both up-regulated and down-regulated genes. In this case, two ranking scores were obtained separately, and the down-regulated associated signature score was subtracted from the up-regulated generated signature score. A contour plot which takes into account only those cells that have a signature score above the indicated threshold was added on top of the tSNE space, in order to further emphasize the region of highly scored cells.

Statistical analyzes

All statistical analyses were conducted in Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For time-course experiments, significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for multiple hypotheses. For analysis of more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was used, with Tukey’s correction for multiple hypotheses. A t test was used for comparisons between two groups. For the analysis of RNA and single-cell RNA sequencing data, FDR correction for multiple comparisons was used. All the statistical tests were two-tailed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

C.L. acknowledges grant support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant agreement no. 726225) and the Israel Science Foundation (no. 2017/20). C.L. thanks Medina and Elisha and Yuval and Omer with endless gratitude and A.M. thanks Nerya for continuous support.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Av.M., C.L. and Y.C. Methodology: Av.M., C.L. and Y.C. Investigation: Av.M., S.P., R.P., G.B., N.E., S.G.T., S.G., L.R., M.K., R.B., H.V., E.N., L.M., Y.C., N.K.S., Ar.M., T.Ge., E.S., T.Go., Y.S., K.R., As.M., A.R., P.M., A.K., N.S.M., O.K., M.N., A.G., V.Z.W. and I.A.L. Supervision: C.L. and Y.C. Writing—original draft: Av.M. and C.L.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joy Edwards-Hicks, Yuwen Zhu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD050734. The single cell RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE272861. Published data that was used in Supplementary Fig. 3c refers to reference28. The data used in this study are available via Single Cell Portal [https://portals.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP490/aging-promotes-reorganization-of-the-cd4-t-cell-landscape-toward-extreme-regulatory-and-effector-phenotypes]. Published data that was used in Supplementary Fig. 6d refers to reference45. The data used in this study are available via the PRIDE database (http://www.proteomexchange.org) under accession numbers PXD004367 and PXD005492. All remaining data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are presented in the main article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Yaron Carmi, Carmit Levy.

Contributor Information

Yaron Carmi, Email: yaroncarmi@tauex.tau.ac.il.

Carmit Levy, Email: carmitlevy@tauex.tau.ac.il.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52079-x.

References

- 1.Roelandts, R. The history of phototherapy: something new under the sun? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.46, 926–930 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romerdahl, C. A., Donawho, C., Fidler, I. J. & Kripke, M. L. Effect of ultraviolet-B radiation on the in vivo growth of murine melanoma cells. Cancer Res48, 4007–4010 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donawho, C. K. & Kripke, M. L. Evidence that the local effect of ultraviolet radiation on the growth of murine melanomas is immunologically mediated. Cancer Res51, 4176–4181 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart, P. H. et al. Dermal mast cells determine susceptibility to ultraviolet B-induced systemic suppression of contact hypersensitivity responses in mice. J. Exp. Med.187, 2045–2053 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damiani, E. & Ullrich, S. E. Understanding the connection between platelet-activating factor, a UV-induced lipid mediator of inflammation, immune suppression and skin cancer. Prog. Lipid Res.63, 14–27 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noonan, F. P., De Fabo, E. C. & Morrison, H. Cis-urocanic acid, a product formed by ultraviolet B irradiation of the skin, initiates an antigen presentation defect in splenic dendritic cells in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol.90, 92–99 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart, P. H., Gorman, S. & Finlay-Jones, J. J. Modulation of the immune system by UV radiation: more than just the effects of vitamin D? Nat. Rev. Immunol.11, 584–596 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moodycliffe, A. M., Kimber, I. & Norval, M. Role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in ultraviolet B light-induced dendritic cell migration and suppression of contact hypersensitivity. Immunology81, 79–84 (1994). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ullrich, S. E. The effect of ultraviolet radiation-induced suppressor cells on T-cell activity. Immunology60, 353–360 (1987). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakowska, J. et al. Autoimmunity and cancer-two sides of the same coin. Front. Immunol.13, 793234 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert, C. A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat. Commun.11, 3801 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harel, M. et al. Proteomics of melanoma response to immunotherapy reveals mitochondrial dependence. Cell179, 236–250 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González Maglio, D. H., Paz, M. L. & Leoni, J. Sunlight effects on immune system: is there something else in addition to UV-induced immunosuppression? Biomed. Res. Int.2016, 1934518 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schade, N., Esser, C. & Krutmann, J. Ultraviolet B radiation-induced immunosuppression: molecular mechanisms and cellular alterations. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci.4, 699–708 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz, T. Mechanisms of UV-induced immunosuppression. Keio J. Med.54, 165–171 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skopelja-Gardner, S. et al. Acute skin exposure to ultraviolet light triggers neutrophil-mediated kidney inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA118, e2019097118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon, J. C., Tigelaar, R. E., Bergstresser, P. R., Edelbaum, D. & Cruz, P. D. Ultraviolet B radiation converts Langerhans cells from immunogenic to tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells. Induction of specific clonal anergy in CD4+ T helper 1 cells. J. Immunol.146, 485–491 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart, P. H. & Norval, M. More than effects in skin: ultraviolet radiation-induced changes in immune cells in human blood. Front. Immunol.12, 694086 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garssen, J. et al. UVB exposure-induced systemic modulation of Th1- and Th2-mediated immune responses. Immunology97, 506–514 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi, M. et al. Establishment and characterization of a malignant melanocytic tumor cell line expressing the ret oncogene. Oncogene7, 1491–1496 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato, M. et al. Transgenic mouse model for skin malignant melanoma. Oncogene17, 1885–1888 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]