Abstract

Classic psychedelics have regained interest in research and therapy. Despite the long tradition of the human use of mescaline, modern data on its dose-dependent acute effects and pharmacokinetics are lacking. Additionally, its mechanism of action has not been investigated in humans. We used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design in 16 healthy subjects (8 women) who received placebo, mescaline (100, 200, 400, and 800 mg), and 800 mg mescaline together with the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A (5-HT2A) receptor antagonist ketanserin (40 mg) to assess subjective effects, autonomic effects, adverse effects, and pharmacokinetics up to 30 h after drug administration. Mescaline at doses >100 mg induced dose-dependent acute subjective effects. Mescaline increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure at doses >100 mg, with no difference between doses of 200-800 mg. Heart rate increased dose-dependently. Pharmacokinetics of mescaline were dose-proportional. Maximal concentrations were reached after approximately 2 h, and the plasma elimination half-life was approximately 3.5 h. The average duration of subjective effects increased from 6.4 to 14 h with increasing doses of 100-800 mg mescaline. Nausea and emesis were frequent adverse effects at the 800 mg dose. Co-administration of ketanserin attenuated and shortened acute effects of 800 mg mescaline to become comparable to the 100 and 200 mg doses. There were no ceiling effects of the subjective response within the investigated dose range, but tolerability was lower at the highest doses. These results may assist with dose finding for future research and suggest that acute effects of mescaline are primarily mediated by 5-HT2A receptors.

Subject terms: Pharmacology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a serotonergic psychedelic with a long history of ethnomedical use [1, 2]. Other classic psychedelics include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin, and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), which have regained interest in psychiatric research. LSD and psilocybin are particularly being investigated as treatments for depression and anxiety-related disorders [3–7]. Mescaline is found as an alkaloid in different species of cacti (e.g., peyote or San Pedro) in North and South America. The radiocarbon dating and alkaloid analysis of archeological specimens of peyote buttons revealed that mescaline was used for more than 5000 years by native North Americans [8]. Subjective effects of mescaline were scientifically investigated and described starting at the end of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century [9–13]. In contrast to other classic psychedelics, there has been little contemporary clinical research on mescaline. A recent first study determined the dose-equivalence of mescaline, LSD, and psilocybin and found no differences in the overall quality of subjective effects between these three classic psychedelics [14]. However, no modern data are available on the acute psychedelic effects, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of different doses of mescaline in humans. Therefore, we investigated acute subjective, autonomic, and adverse effects of mescaline across a range of doses and within-subjects in healthy participants. The selected range covers doses from very low to very high, based on previous studies with mescaline [2, 12, 14–16]. Additionally, we fully characterized the pharmacokinetics of different doses of mescaline. The psychedelic effects of LSD, psilocybin, and DMT have been shown to be mediated primarily by serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A (5-HT2A) receptors in humans. Specifically, the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin prevented [17–20] or reversed [21] most acute subjective effects in healthy subjects. No studies have yet similarly explored the mechanism of action of mescaline in humans. Hence, we investigated the role of 5-HT2A receptors in acute effects of mescaline by administering a high dose of 800 mg mescaline with either the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin or placebo. The present study is the first contemporary full characterization of acute effects of different doses of mescaline that describes the role of 5-HT2A receptors in mescaline-induced altered states in healthy volunteers. We hypothesized that effects of mescaline would be dose-dependent and blocked by ketanserin.

Methods and materials

Study design

The study used a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over design with six experimental test sessions to investigate responses to (i) placebo, (ii) 100 mg mescaline, (iii) 200 mg mescaline, (iv) 400 mg mescaline, (v) 800 mg mescaline, and (vi) 800 mg mescaline plus 40 mg ketanserin that were administered in a counter-balanced order. The washout periods between sessions were at least 14 days. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines in Good Clinical Practice and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Switzerland (EKNZ) and Swiss Federal Office for Public Health. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04849013).

Participants

Sixteen healthy subjects (8 men and 8 women; mean age ± SD: 33 ± 10 years; range: 25-55 years) were recruited by word of mouth. All subjects provided written informed consent and were paid for their participation. Exclusion criteria were age <25 years or >65 years, pregnancy (urine pregnancy tests were performed at screening and before each test session), personal or first-degree relative psychotic disorders, current or history of major psychiatric disorders (assessed by the Semi-structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Axis I disorders), the use of medications that may interfere with the study drugs (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives), chronic or acute physical illness (e.g., abnormal physical exam, electrocardiogram, or hematological and chemical blood analyses), tobacco smoking (>10 cigarettes/day), lifetime prevalence of hallucinogenic drug use >20 times (except for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol), illicit drug use within the last 2 months, and illicit drug use during the study period (determined by randomly performed urine drug tests). The participants were asked to consume no more than 20 standard alcoholic drinks/week and have no more than one drink on the day before the test sessions.

Thirteen participants had previously used a psychedelic (3-15 times), including LSD (11 participants), psilocybin (10 participants), DMT (three participants), and mescaline (three participants). Nine participants had used 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 2-10 times). Ten participants had used a stimulant (1-15 times), including methylphenidate (two participants), amphetamine (three participants), and cocaine (nine participants). Two participants had used 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenethylamine (2C-B; 1-2 times). Two participants had used ketamine (1-5 times). Six participants had used nitrous oxide (1-5 times). One participant had never used any illicit drugs with the exception of cannabis.

Study drugs

Mescaline hydrochloride (ReseaChem GmbH, Burgdorf, Switzerland) was administered in capsules that were produced according to Good Manufacturing Practice in dosing units that contained 100 mg mescaline hydrochloride. Ketanserin was obtained as the marketed drug Ketensin (20 mg, Janssen-Cilag, Leiden, NL) and encapsulated with opaque capsules to ensure blinding. Placebo consisted of identical opaque capsules that were filled with mannitol. See Supplementary Methods online for details. At the end of each session and at the end of the study, the participants were asked to retrospectively guess their treatment assignment.

Study procedures

The study included a screening visit, six 31-h test sessions (each separated by at least 14 days), and an end-of-study visit. The sessions were conducted in a calm hospital room. Only one research subject and one investigator were present during each test session. The test sessions began at 8:00 AM. A urine sample was taken to verify abstinence from drugs of abuse, and a urine pregnancy test was performed in women with child-bearing potential. The subjects then underwent baseline measurements. Ketanserin (40 mg) or placebo and mescaline or placebo were administered at 9:00 AM. The outcome measures were repeatedly assessed for 30 h after drug administration. A standardized lunch and dinner were served. The subjects were never alone during the first 16 h after drug administration, and the investigator was in a room next to the subject for up to 30 h. The subjects were sent home the next day at 3:15 PM.

Subjective drug effects

Subjective effects were assessed repeatedly using visual analog scales (VASs) [22, 23] and the Adjective Mood Rating Scale (AMRS) [24]. The 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC) scale [25, 26] was administered at the end of the session at 30 h after drug administration to retrospectively rate peak drug effects. Mystical experiences were similarly assessed 30 h after drug administration using the States of Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ) [27, 28] that includes the 43-item Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ43) [27], the 30-item MEQ 30 [29], and subscales for “aesthetic experience” and negative “nadir” effects. Subjective effects ratings are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods online.

Autonomic and adverse effects

Blood pressure, heart rate, tympanic body temperature, and pupil size were repeatedly measured [30]. Adverse effects were assessed using the List of Complaints 1 h before and 14 and 30 h after drug administration.

Plasma mescaline and ketanserin concentrations

Blood was collected into lithium heparin tubes at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 20, 24, and 30 h after drug administration. The blood samples were immediately centrifuged, and plasma was subsequently stored at -80 °C until analysis. Plasma concentrations of mescaline and ketanserin were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [21, 31].

Data analysis

Peak (Emax and/or Emin), peak change from baseline (ΔEmax and/or ΔEmin) values or area under the effect curve (AUEC) were determined for repeated measures. The values were then analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with drug dose as the within-subjects factor. Additional ANOVAs were performed with order as between-subjects factor. Tukey post hoc tests were performed based on significant main effects or interactions. For data analysis, the statistical analysis software R was used ([32]. The criterion for significance was p < 0.05. Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using non-compartmental models in Phoenix WinNonlin 6.4 (Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA) [33]. The time to onset, maximal effect, offset, effect duration, and AUEC were assessed in the any-drug-effect–time plots using a threshold of 10% of the maximum individual response. The AUEC was determined using linear trapezoidal with linear interpolation method in Phoenix WinNonlin 6.4 [33].

Results

Subjective drug effects

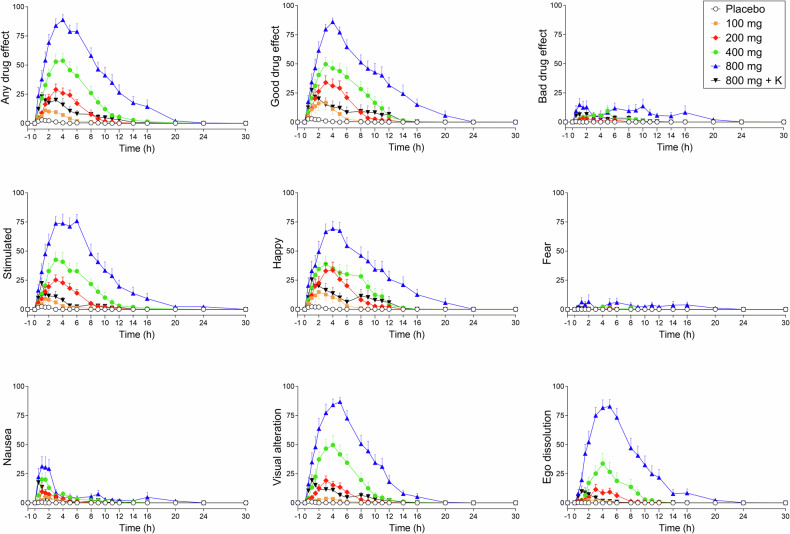

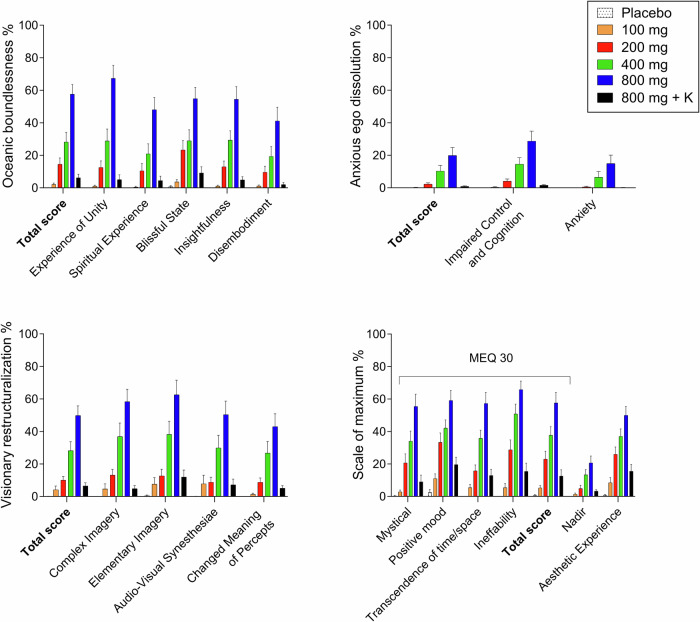

Subjective effects over time on the VAS and AMRS are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2. The corresponding peak responses and statistics are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Alterations of mind on the 5D-ASC and mystical-type experiences on the MEQ 30 are presented in Fig. 2. Statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 1. Acute subjective effects of different doses of mescaline over time.

Mescaline elicited dose-dependent acute subjective effects compared with placebo. No ceiling effects were reached. The co-administration of ketanserin strongly reduced acute effects of mescaline (800 mg). Both mescaline (100–800 mg) and ketanserin (K; 40 mg) and their respective placebos were administered at t = 0 h. The data show the mean ± SEM of Visual Analog Scale ratings (0–100%) in 16 participants. Maximal responses and statistics are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 2. Acute alterations of consciousness on the 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC) Scale and mystical-type experiences on the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ).

Mescaline produced dose-dependent alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences compared with placebo, with significant changes at doses >100 mg. There was no ceiling effect. The co-administration of ketanserin (K) reduced acute alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences of mescaline (800 mg) to the level of 100–200 mg mescaline. The data show the mean ± SEM percentage of maximally possible scale scores in 16 participants. Statistics are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

On the VAS, mescaline produced dose-dependent subjective effects starting at the 200 mg dose. Significant bad drug effects occurred only at the 800 mg dose. Nausea increased at 400-800 mg compared with placebo (Fig. 1). Generally, higher doses produced proportionally greater subjective responses with no ceiling effect (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). The maximal effect, area under the effect-time curve, and effect duration of “any drug effect” consistently increased dose-dependently (Table 1). Ketanserin co-administration strongly reduced and shortened the subjective response to 800 mg mescaline to become similar to the effect of 100-200 mg mescaline (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Individual mescaline effect reductions by ketanserin along with plasma ketanserin levels in each participant are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. No order effects were observed in the subjective response to mescaline, except for nausea.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the acute subjective response to Mescaline.

| Effect | Mescaline 100 mg | Mescaline 200 mg | Mescaline 400 mg | Mescaline 800 mg | Mescaline 800 mg + 40 mg Ketanserin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 16 | n = 16 | n = 16 | n = 16 | n = 16 | |

| Time to onset (h) | 0.5 ± 0.5a (0.1–1.7) | 0.6 ± 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.6 ± 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.5 ± 0.5 (0.1–1.8) | 0.3 ± 0.3 (0.1–1.1) |

| Time to offset (h) | 6.9 ± 2.2a (3.9–11) | 8.9 ± 1.6 (5.8–12) | 11 ± 2.8 (8.1–19) | 15 ± 3.9 (7.3–22) | 7.9 ± 4.3 (1.5–17) |

| Time to maximal effect (h) | 2.0 ± 1.3 (0.0–5.0) | 3.0 ± 1.0 (1.0–5.0) | 3.2 ± 1.3 (1.5–6.0) | 3.4 ± 1.3 (0.5–6.0) | 1.9 ± 1.4 (0.5–6.0) |

| Effect duration (h) | 6.4 ± 2.0a (3.0–10) | 8.3 ± 1.7 (4.7–12) | 11 ± 2.8 (7.9–19) | 14 ± 3.7 (7.2–22) | 7.7 ± 4.1 (1.4–17) |

| Maximal effect (%) | 16 ± 13 (0–51) | 33 ± 17 (10–74) | 60 ± 26 (9–100) | 92 ± 15 (50–100) | 38 ± 23 (17–91) |

| AUEC | 45 ± 38 (0–138) | 154 ± 100 (44–429) | 370 ± 216 (32–821) | 817 ± 353 (318–1676) | 147 ± 141 (24–519) |

Parameters are for “any drug effect” as determined using the individual effect-time curves. The threshold to determine times to onset and offset was set to 10% of the individual maximal response. Values are mean ± SD (range); AUEC area under the effect curve; an = 14.

Mescaline dose-dependently increased alterations of mind and mystical-type experiences on the 5D-ASC and MEQ 30, respectively, starting at 200 mg compared with placebo (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). Anxiety on the 5D-ASC significantly increased only at the 800 mg dose. 5D-ASC and MEQ 30 ratings markedly and mostly significantly increased further from 400 to 800 mg, indicating no ceiling effect at the doses tested.

Ketanserin co-administration reduced 5D-ASC and MEQ 30 scores compared with 800 mg mescaline alone to levels that were reached with 100-200 mg mescaline (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Autonomic and adverse effects

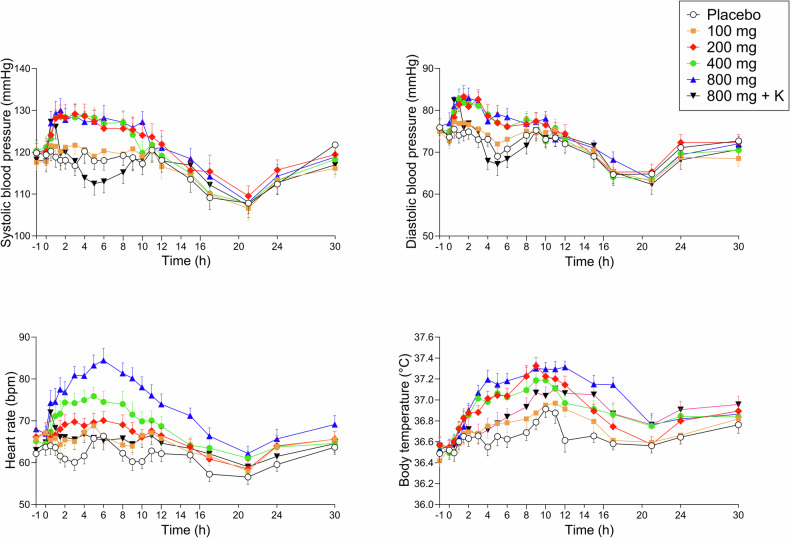

Autonomic effects over time are shown in Fig. 3. Maximal effects and statistics are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Adverse effects are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S3.

Fig. 3. Acute autonomic effects of mescaline over time.

Mescaline increased diastolic and systolic blood pressure at 200–800 mg compared with placebo and independent of dose. Mescaline dose-dependently elevated heart rate and body temperature at doses of 200–800 mg. Ketanserin decreased all autonomic effects of mescaline. Both mescaline (100–800 mg) and ketanserin (K; 40 mg) were administered at t = 0 h. The data show mean ± SEM values in 16 participants. Maximal responses and statistics are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Mescaline increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure and body temperature relatively similarly at the 200-800 mg doses compared with placebo (Fig. 3). In contrast, mescaline increased heart rate more dose-dependently compared with placebo (Fig. 3). Co-administration of ketanserin reversed the mescaline-induced elevations of blood pressure and heart rate. The peak blood pressure responses to mescaline were not significantly reduced by ketanserin because the onset of the effect of ketanserin occurred after the mescaline-induced increase in blood pressure. The peak effect of mescaline (800 mg) on heart rate and body temperature was significantly reduced by ketanserin (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Mescaline dose-dependently increased pupil size and reduced the light reflex compared with placebo. Ketanserin transiently reduced these mescaline-induced changes in pupillary function (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S1). Mescaline dose-dependently induced acute (0–14 h) and subacute (14–30 h) adverse effects on the List of Complaints compared with placebo (Supplementary Tables S1 and S3). Frequent acute adverse effects included fatigue, headache, lack of concentration, and nausea (Supplementary Table S3). Mescaline caused emesis in two and seven subjects at the 400 and 800 mg doses, respectively. Ketanserin co-administration reduced the number of participants who experienced emesis to two. One subject reported having one flashback after the study day with 800 mg mescaline. [34]. Spontaneously reported adverse events during the study included headaches (3 subjects), stomachache (1 subject), dizziness (1 subject), and nosebleed (1 subject).

Pharmacokinetics

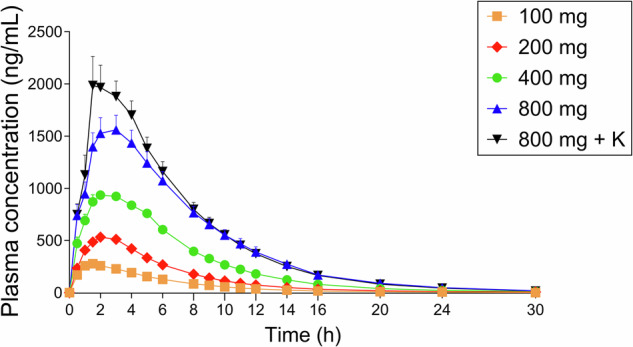

Pharmacokinetic parameters of mescaline and its two main metabolites, 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylacetic acid and N-acetyl mescaline, are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4. Plasma mescaline concentrations increased proportionally with increasing mescaline doses (Fig. 4). However, the 400 and 800 mg doses of mescaline resulted in slightly lower concentrations than expected based on the 100 mg mescaline, 200 mg mescaline, and 800 mg mescaline + ketanserin conditions, likely because of more vomiting. The concentration of 800 mg mescaline was in the expected range when it was co-administered with ketanserin, which reduced vomiting.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters [geometric mean (95% CI), range] of parent substances and their metabolites.

| Cmax (ng/mL) | tmax (h) | t1/2 (h) | AUC30 (ng h/mL) | AUC∞ (ng h/mL) | CL/F (L/h) | Vz/F (L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mescaline 100 mg | |||||||

| Mescaline | 298 (268–332) | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 3.5 (3.2–3.8) | 1767 (1660–1880) | 1805 (1700–1916) | 55 (52–59) | 281 (254–312) |

| 205–420 | 1.0–4.0 | 2.6–4.4 | 1346–2038 | 1395–2063 | 49–72 | 205–380 | |

| TMPAA | 277 (249–308) | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) | 4.0 (3.6–4.4) | 1632 (1454–1830) | 1676 (1496–1878) | 60 (53–67) | 346 (305–392) |

| 203–401 | 1.0–3.0 | 2.6–5.5 | 1068–2382 | 1109–2438 | 41–90 | 256–571 | |

| NAM | 14 (8–25) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 60 (32–113) | 63 (34–117) | 1588 (858–2939) | 5372 (3147–9171) |

| 3.0–83 | 1.0–3.0 | 1.5–3.1 | 7.7–502 | 8.8–504 | 198–11,305 | 899–24,884 | |

| Mescaline 200 mg | |||||||

| Mescaline | 568 (522–619) | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 3.7 (3.4–4.0) | 3588 (3342–3853) | 3636 (3393–3898) | 55 (51–59) | 292 (266–321) |

| 444–696 | 1.0–4.0 | 2.6–5.1 | 2582–4737 | 2642–4775 | 42–76 | 224–404.9 | |

| TMPAA | 530 (475–591) | 1.9 (1.7–2.2) | 4.1 (3.8–4.4) | 3288 (2962–3650) | 3344 (3021–3701) | 60 (54–66) | 351 (313–394) |

| 338–710 | 1.5–3.0 | 3.0–5.0 | 2253–4540 | 2331–4578 | 44–86 | 246–551 | |

| NAM | 38 (22–66) | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 177 (95–332) | 181 (98–336) | 1105 (595–2049) | 3496 (2051–5959) |

| 5.8–211 | 1.5–4.0 | 1.3–3.5 | 18–1351 | 20–1355 | 148–9995 | 587–19131 | |

| Mescaline 400 mg | |||||||

| Mescaline | 1034 (944–1132) | 2.3 (1.8–2.9) | 3.7 (3.4–3.9) | 7435 (6791–8140) | 7493 (6844–8204) | 53 (49–58) | 283 (258–311) |

| 692–1328 | 1.0–5.0 | 2.9–4.7 | 5443–10,491 | 5478–10,550 | 38–73 | 206–415 | |

| TMPAA | 872 (768–992) | 2.5 (2.1–3.1) | 4.1 (3.8–4.5) | 6259 (5415–7235) | 6331 (5474–7322) | 63 (55–73) | 377 (335–423) |

| 488–1431 | 1.5–5.0 | 3.0–6.2 | 3540–9979 | 3569–10,274 | 39–112 | 270–590 | |

| NAM | 79 (49–127) | 2.9 (2.4–3.4) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 446 (259–769) | 450 (262–773) | 889 (517–1529) | 2842 (1762–4584) |

| 18–324 | 1.5–5.0 | 1.7–3.4 | 69–2441 | 70–2449 | 163–5702 | 582–14,921 | |

| Mescaline 800 mg | |||||||

| Mescaline | 1721 (1482–1998) | 2.2 (1.5–3.2) | 3.7 (3.5–4.0) | 13,047 (11,119–15,310) | 13,144 (11,190–15,439) | 61 (52–72) | 328 (282–381) |

| 1021–2414 | 0.5–6.0 | 3.2–5.3 | 7274–17,485 | 7313–17,636 | 45–109 | 229–611 | |

| TMPAA | 1532 (1294–1814) | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 11,554 (9435–14,149) | 11,677 (9502–14,351) | 69 (56–84) | 413 (347–491) |

| 919–3007 | 1.0–6.0 | 3.4–6.2 | 6752–23,286 | 6784–23,502 | 34–118 | 236–666 | |

| NAM | 159 (99–257) | 3.4 (2.8–4.3) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 980 (562–1707) | 983 (565–1712) | 814 (467–1416) | 2621 (1637.7–4193) |

| 42–519 | 1.5–6.0 | 1.5–3.5 | 185–4529 | 186–4533 | 176–4292 | 649–10,779 | |

| Mescaline 800 mg + Ketanserin 40 mg | |||||||

| Mescaline | 2260 (1775–2879) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 3.8 (3.6–4.0) | 14,239 (11,654–17,396) | 14,317 (11,721–17,489) | 56 (46–68) | 305 (247–377) |

| 771–3965 | 1.0–5.0 | 3.3–4.4 | 5212–20,987 | 5245–21,100 | 38–153 | 202–866 | |

| TMPAA | 1564 (1253–1953) | 2.9 (2.3–3.6) | 4.1 (3.9–4.2) | 11,910 (9492–14,944) | 12,000 (9565–15,054) | 67 (53–84) | 390 (305–498) |

| 484–2935 | 1.0–6.0 | 3.5–4.6 | 4247–24,085 | 4285–24,327 | 33–187 | 182–1191 | |

| NAM | 162 (93–282) | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | 2.3 (2.1–2.5) | 984 (525–1846) | 988 (528–1851) | 809 (432–1516) | 2676 (1506–4753) |

| 31–809 | 1.5–5.0 | 1.7–3.5 | 175–6401 | 177–6404 | 125–4518 | 429–15,003 | |

AUC area under the plasma concentration-time curve, AUC∞ AUC from time zero to infinity, AUC30 from time 0–30 h, CL/F apparent total clearance, Cmax maximum observed plasma concentration, total after deglucuronidation (unconjugated + glucuronide); unconjugated, t1/2 plasma half-life, tmax time to reach Cmax, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, Vz/F apparent volume of distribution, TMPAA 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylacetic acid, NAM N-acetyl mescaline; data are geometric mean with 95% confidence interval of the mean and range; n = 16.

Fig. 4. Plasma concentrations of different doses of mescaline.

Plasma concentrations of mescaline increased in a dose-proportional manner. Plasma concentration of mescaline after the 800 mg dose was slightly lower than expected, likely due to emesis in 6 of 16 participants during onset of drug effects and potentially reduced availability of the orally administered amount of mescaline. When mescaline was administered together with ketanserin (K), nausea and vomiting were reduced (only one participant experienced emesis). Concentrations of mescaline were in the expected range (twice as high as with the 400 mg dose) when the 800 mg dose was administered with ketanserin. Mescaline and ketanserin were administered at t = 0 h. Values are mean ± SEM. Pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 2.

Blinding

Results of the blinding assessment are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The 800 and 400 mg doses of mescaline were correctly identified by 16 and 15 participants, respectively, at the end-of-study visit. Two of the 16 subjects mistook 100 mg mescaline for placebo. All other doses of mescaline were identified as active doses. The mescaline and ketanserin combination was identified correctly by 12 subjects or mistaken as 100 mg mescaline (three subjects) or 200 mg mescaline (one subject) when they were asked after the sessions.

Discussion

The present study was the first current investigation of acute effects of different doses of mescaline in healthy participants. We found that mescaline dose-dependently produced acute subjective responses without reaching a ceiling effect at the doses tested. Mescaline increased blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and pupil size and induced acute adverse effects, including headaches and nausea. Co-administration of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin strongly reduced all acute effects of mescaline, indicating that acute psychedelic and physical effects of mescaline primarily depend on 5-HT2A receptor activation. Additionally, we characterized pharmacokinetics of different doses of mescaline. Pharmacokinetics of mescaline were dose-proportional, with linear elimination kinetics and an elimination half-life of approximately 3.5 h. The relatively long duration of action of mescaline was attributable to slow absorption and consequently a long time to reach maximal effects.

A previous recent study characterized acute effects of 300 and 500 mg doses of mescaline in healthy subjects [14]. However, these two doses were administered in different participants using a parallel design. In contrast, the present study compared four different doses of mescaline, placebo, and the co-administration of mescaline and ketanserin within-subjects. We documented dose-dependent increases in subjective effects, including alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences starting at the 200 mg dose. Additionally, the effects were still increasing on practically all subjective effect measures when the dose was increased from 400 to 800 mg. Thus, no ceiling effect was observed at relatively high doses, in contrast to two recent studies with LSD [17, 35] and one study that used an identical design [17] and where 200 µg LSD did not produce more positive mood effects or more positive alterations of consciousness compared with 100 µg LSD. The present findings indicate that we were dosing within the linear range of the dose-effect curve with mescaline and that a ceiling effect for positive experiences may be reached only at higher doses. Confirming this view, a 500 mg dose of mescaline hydrochloride produced comparable effects to 100 µg LSD base or 20 mg psilocybin dihydrate when they were compared within the same study and subjects [14]; therefore, an 800 mg dose of mescaline could be expected to correspond to 160 µg LSD base or 32 mg psilocybin dihydrate. One might speculate that a higher 1000 mg dose of mescaline (corresponding to 200 µg LSD) might result in a ceiling effect. However, the 800 mg dose already produced substantial adverse effects, including relevant nausea and vomiting, and we expect tolerability of the 1000 mg mescaline dose to be low. In contrast, 100 mg of mescaline was chosen as the lowest dose administered in this study to elicit the threshold for inducing acute subjective effects. Dosages ranging from 178 to 356 mg of mescaline hydrochloride are considered moderate [36].

The present study also investigated the mechanism of action of mescaline in humans. Mescaline shows binding affinity for 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A and adrenergic α2A receptors [2, 37]. Blocking only 5-HT2A receptors with ketanserin reduced most acute effects of mescaline in the present study, indicating that 5-HT2A receptors primarily mediated these responses. Typically, the subjects correctly identified the co-administration of mescaline and ketanserin because of the initial short-lasting effects of mescaline, followed by a marked and rapid decrease. The present study complements previous findings that ketanserin attenuated acute psychedelic effects of LSD and psilocybin in humans [17–19, 21]. Importantly, ketanserin was administered at the same time as mescaline in the present study and not before. In several participants, initial effects of mescaline appeared before sufficient ketanserin reached the circulation and could antagonize the mescaline response. Therefore, the remaining acute effects of mescaline, when co-administered with ketanserin, were partly attributable to the delayed kinetics and effect of ketanserin in some participants and not to a failure of ketanserin to dynamically block the mescaline response. However, minimal subjective effects of mescaline persisted after maximal ketanserin concentrations were reached, indicating a very minor contribution of other receptors to the mediation of acute effects of mescaline. The reason for using co-administration rather than the pre-administration of ketanserin in the present study was our concern that effects of mescaline may be reestablished later in the day because of the long duration of action of mescaline and historically reportedly much longer plasma half-life of mescaline (6 h) [38] compared with ketanserin (2 h for the clinically relevant early half-life) [39].

The present study was the first to use a range of different doses of mescaline to characterize its pharmacokinetics using modern analytics. Plasma concentrations (Cmax and the area under the curve) increased dose-proportionally with increasing doses. The concentrations were slightly lower at the 400 and 800 mg doses of mescaline, very likely because of emesis at the mescaline effect onset, which may have removed some of the administered substance (4–8 capsules of 100 mg were administered to obtain these doses). The co-administration of ketanserin with mescaline reduced nausea and emesis and resulted in higher mescaline concentrations that were in the range that was expected based on dose-proportional extrapolation of the values of lower doses. We found that the order in which mescaline doses were administered had no significant effect on the subjective response with exception for nausea. This may be explained by the fact that subjects were sensitized for nausea after receiving a high dose first, which was more likely to induce nausea. However, it is unclear why mescaline induced more nausea compared with other classic serotonergic psychedelics having a similar receptor profile [40].

The present study found that mescaline produced moderate autonomic effects, including increases in blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and pupil size as previously reported [14] and very similar to LSD [14, 17] and psilocybin [14].

The present study confirmed the recently reported plasma elimination half-life of approximately 3.6 h [14], which is markedly shorter than the 6 h that was indicated by earlier studies [36, 38]. Consistent with the elimination half-life of mescaline of 3.6 h, doubling the dose of mescaline in the present study extended the effect duration by approximately 3 h. The average effect durations of mescaline were 10.7 and 14 h at the 400 and 800 mg doses, respectively. The average effect durations were 9.7 and 11.1 h at 300 and 500 mg mescaline, respectively, in a previous study [14]. By comparison, the effect durations of LSD were 8.3 and 11 h at 100 and 200 µg LSD, respectively, when measured similarly [17]. Notably, the longer effect duration of mescaline is not attributable to longer plasma elimination because the plasma elimination half-life of LSD is 4 h and comparable to mescaline [17]. The longer duration of action of mescaline can largely be explained by its longer time (2.2 h) to reach the peak plasma concentration compared with LSD (1.3–1.4 h) and the resulting longer time to reach peak responses for mescaline (3.2–4.0 h) compared with LSD (2.3–2.5 h) [14, 17].

The present study had several notable strengths. Four different doses of mescaline were administered within the same study and within-subjects and compared to a placebo in a controlled laboratory environment under double-blind conditions. Furthermore, a ketanserin-mescaline condition was included to shed light on the mechanism of action of mescaline in humans. We also improved blinding of the different conditions by using several active doses and the ketanserin condition. We included the same number of female and male participants. We administered internationally used, standardized, and validated psychometric assessments. Finally, plasma mescaline concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters of pharmaceutically well-defined doses of mescaline were analyzed for all doses and up to 30 h. Ketanserin concentrations were also determined. Despite these strengths, the study also had limitations. We did not include doses higher than 800 mg mescaline. Ketanserin was administered at the same time as mescaline and not as a pretreatment. All but one participant had prior experience with psychedelics, although no one had used them more than 15 times. Finally, the study was conducted in a highly regulated environment and involved only healthy people, meaning that responses to mescaline may differ among individuals in other settings and those with psychiatric conditions.

Conclusion

The present study characterized acute subjective and autonomic effects of different doses of mescaline. Starting at the 200 mg dose of mescaline, it produced dose-dependent psychedelic effects up to 800 mg, with no ceiling effect. The 800 mg dose of mescaline produced significant subjective bad drug effects and emesis. The present mescaline dose-response data may be useful for defining doses in future psychedelic research in healthy subjects and patients. The co-administration of ketanserin together with 800 mg mescaline attenuated the acute response, confirming that serotonin 5-HT2A receptors are primarily involved in psychedelic effects of mescaline in humans.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Denis Arikci, Fabio Coviello, Sophie Dierbach, Nepomuk Halter, Elias Hartmann, Ioanna Istampoulouoglou, Nadia Leonti, Miriam Meier, Mikko Mutti, Albiona Nuraj, Manuel Strebel, Lorenz Müller, Moira Rathgeb, Salome Jael Stein, Avram Tolev, Anja Vandermissen, and Severin Vogt for their help with conducting the study, Patrick Vizeli for his help with the statistical analyses, and Michael Arends for proofreading the manuscript.

Author contributions

YS and MEL designed the research. AK, AB, IS, LE, AJ, JT and DL performed the research. AK, JT, DL and MEL analyzed the data. AK, YS and MEL wrote the manuscript with input from all of the other authors. All authors gave final approval to the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 32003B_185111 to MEL) and Mind Medicine, Inc. Knowhow and data associated with this work and owned by the University Hospital Basel were licensed by Mind Medicine, Inc. Mind Medicine, Inc. had no role in planning or conducting the present study or the present publication.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data associated with this work are owned by the University Hospital Basel and were licensed by Mind Medicine. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to MEL, matthias.liechti@usb.ch.

Competing interests

MEL is a consultant for Mind Medicine, Inc. The other authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines in Good Clinical Practice and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Switzerland (EKNZ) and Swiss Federal Office for Public Health. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04849013). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-024-03116-2.

References

- 1.La Barre W. Peyotl and mescaline. J Psychedelic Drugs. 1979;11:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassels BK, Saez-Briones P. Dark classics in chemical neuroscience: mescaline. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2018;9:2448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Rotz R, Schindowski EM, Jungwirth J, Schuldt A, Rieser NM, Zahoranszky K, et al. Single-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy in major depressive disorder: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;56:101809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raison CL, Sanacora G, Woolley J, Heinzerling K, Dunlop BW, Brown RT, et al. Single-dose psilocybin treatment for major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:843–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin GM, Croal M, Feifel D, Kelly JR, Marwood L, Mistry S, et al. Psilocybin for treatment resistant depression in patients taking a concomitant SSRI medication. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:1492–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holze F, Gasser P, Muller F, Dolder PC, Liechti ME. Lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety with and without a life-threatening illness: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruhn JG, De Smet PA, El-Seedi HR, Beck O. Mescaline use for 5700 years. Lancet. 2002;359:1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beringer K. Der Meskalinrausch. Berlin: Springer; 1927.

- 10.Guttmann E. Artificial psychoses produced by mescaline. J Ment Sci. 1936;82:204–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guttmann E, Maclay WS. Mescaline and depersonalization: therapeutic experiments. J Neurol Psychopathol. 1936;16:193–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermle L, Funfgeld M, Oepen G, Botsch H, Borchardt D, Gouzoulis E, et al. Mescaline-induced psychopathological, neuropsychological, and neurometabolic effects in normal subjects: experimental psychosis as a tool for psychiatric research. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:976–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unger SM. Mescaline, LSD, psilocybin, and personality change. Psychiatry. 1963;26:111–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ley L, Holze F, Arikci D, Becker AM, Straumann I, Klaiber A, et al. Comparative acute effects of mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide, and psilocybin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study in healthy participants. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:1659–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrichs H, Dierssen O, Passie T. Die Psychologie des Meskalinrausches. VWB, Verlag für Wiss. und Bildung; Berlin, 2009.

- 16.Laing R, Laing RR, Beyerstein BL, Siegel JA. Hallucinogens: a forensic drug handbook. Academic Press; San Diego, 2003.

- 17.Holze F, Vizeli P, Ley L, Muller F, Dolder P, Stocker M, et al. Acute dose-dependent effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:537–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stämpfli P, et al. The fabric of meaning and subjective effects in LSD-induced states depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Curr Biol. 2017;27:451–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vollenweider FX, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF, Babler A, Vogel H, Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valle M, Maqueda AE, Rabella M, Rodriguez-Pujadas A, Antonijoan RM, Romero S, et al. Inhibition of alpha oscillations through serotonin-2A receptor activation underlies the visual effects of ayahuasca in humans. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1161–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker AM, Klaiber A, Holze F, Istampoulouoglou I, Duthaler U, Varghese N, et al. Ketanserin reverses the acute response to LSD in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy participants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holze F, Vizeli P, Muller F, Ley L, Duerig R, Varghese N, et al. Distinct acute effects of LSD, MDMA, and D-amphetamine in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:462–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid Y, Enzler F, Gasser P, Grouzmann E, Preller KH, Vollenweider FX, et al. Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:544–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janke W, Debus G. Die Eigenschaftswörterliste. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1978.

- 25.Dittrich A. The standardized psychometric assessment of altered states of consciousness (ASCs) in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31:80–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studerus E, Gamma A, Vollenweider FX. Psychometric evaluation of the altered states of consciousness rating scale (OAV). PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:268–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liechti ME, Dolder PC, Schmid Y. Alterations in conciousness and mystical-type experiences after acute LSD in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:1499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:1182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hysek CM, Vollenweider FX, Liechti ME. Effects of a b-blocker on the cardiovascular response to MDMA (ecstasy). Emerg Med J. 2010;27:586–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomann J, Ley L, Klaiber A, Liechti ME, Duthaler U. Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of mescaline and major metabolites in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2022;220:114980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2023.

- 33.Holze F, Duthaler U, Vizeli P, Muller F, Borgwardt S, Liechti ME. Pharmacokinetics and subjective effects of a novel oral LSD formulation in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:1474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zerssen DV. Die Beschwerden-Liste. Münchener Informationssystem. München: Psychis; 1976.

- 35.Holze F, Ley L, Muller F, Becker AM, Straumann I, Vizeli P, et al. Direct comparison of the acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:1180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Pereira CL, da Silva DD. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects of Peyote and mescaline: clinical and forensic repercussions. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2019;12:184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rickli A, Luethi D, Reinisch J, Buchy D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs). Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:546–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charalampous W, Kinross-Wright. Metabolic fate of mescaline in man. Psychopharmacologia. 1966;9:48–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persson B, Heykants J, Hedner T. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ketanserin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1991;20:263–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data associated with this work are owned by the University Hospital Basel and were licensed by Mind Medicine. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to MEL, matthias.liechti@usb.ch.