ABSTRACT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is well-known for its antimicrobial resistance and the ability to survive in harsh environmental conditions due to an abundance of resistance mechanisms, including the formation of biofilms and the production of exopolysaccharides. Exopolysaccharides are among the major components of the extracellular matrix in biofilms and aggregates of P. aeruginosa. Although their contribution to antibiotic resistance has been previously shown, their roles in resistance to oxidative stressors remain largely elusive. Here, we studied the function of the exopolysaccharides Psl and Pel in the resistance of P. aeruginosa to the commonly used disinfectants and strong oxidizing agents NaOCl and H2O2. We observed that the simultaneous inactivation of Psl and Pel in P. aeruginosa PAO1 mutant strain ∆pslA pelF resulted in a significant increase in susceptibility to both NaOCl and H2O2. Further analyses revealed that Pel is more important for oxidative stress resistance in P. aeruginosa and that the form of Pel (i.e., cell-associated or cell-free) did not affect NaOCl susceptibility. Additionally, we show that Psl/Pel-negative strains are protected against oxidative stress in co-culture biofilms with P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the EPS matrix and, more specifically, Pel exhibit protective functions against oxidative stressors such as NaOCl and H2O2 in P. aeruginosa.

IMPORTANCE

Biofilms are microbial communities of cells embedded in a self-produced polymeric matrix composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA. Biofilm bacteria have been shown to possess unique characteristics, including increased stress resistance and higher antimicrobial tolerance, leading to failures in bacterial eradication during chronic infections or in technical settings, including drinking and wastewater industries. Previous studies have shown that in addition to conferring structure and stability to biofilms, the polysaccharides Psl and Pel are also involved in antibiotic resistance. This work provides evidence that these biofilm matrix components also contribute to the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to oxidative stressors including the widely used disinfectant NaOCl. Understanding the mechanisms by which bacteria escape antimicrobial agents, including strong oxidants, is urgently needed in the fight against antimicrobial resistance and will help in developing new strategies to eliminate resistant strains in any environmental, industrial, and clinical setting.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, biofilms, exopolysaccharides, oxidative stress, sodium hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide, reactive chlorine species

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen found in various environments, from water and soil to animals and humans. This bacterium is commonly associated with nosocomial and difficult-to-treat infections, mainly in immune-compromised individuals (1, 2). The high versatility of P. aeruginosa, its increased resistance to several classes of antibiotics, and its ability to form robust biofilms led this bacterium to be considered a critical priority pathogen that poses a great threat to human health (1, 3).

Biofilms are the most common form of bacterial growth in nature. They are cellular aggregates that can either be found in suspension or attached to biotic or abiotic surfaces encased by a self-produced extracellular polymeric matrix. This extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, which accounts for over 90% of the biofilm biomass (4), is primarily comprised of polysaccharides, extracellular DNA (eDNA), proteins, and lipids and provides the infrastructure for an extremely versatile and adaptable form of multicellular microbial life (5). Besides surface-attached biofilms, non-attached aggregates have been described in nature and disease (6), with research showing that the physiological characteristics of bacteria within such aggregates closely resemble those found in surface-associated biofilms, leading to the classification of aggregates as biofilms (7). Biofilms protect bacteria against the host immune system and render them more tolerant to antibiotics and disinfectants than their planktonic counterparts. This reduced susceptibility is attributed to several factors, including the EPS, high cell density, heterogeneity in metabolism, low metabolic activity, and the presence of persister cells (8, 9).

Exopolysaccharides are highly diverse in composition and structure and are thought to be the major and most important component of the EPS. Different bacterial species produce different exopolysaccharides, with some microbes producing multiple polysaccharides at different stages of aggregate and biofilm formation (5). P. aeruginosa produces at least three exopolysaccharides: Psl, Pel, and alginate (10). Psl, synthesized by the pslA-O operon, is a neutrally charged mannose-rich polysaccharide involved in initial cell-to-cell and cell-surface attachment and is important for the initial attachment of the cells as well as maintenance of the mature biofilm structure (11–14). Pel, expressed through the pelA-G operon, is a positively charged polysaccharide composed of α−1,4 linked galactosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine repeats and has been shown to play roles in cell-to-cell interactions, acting as a primary structural scaffold for the microbial community (15, 16). Psl and Pel are essential for microcolony formation during the early stages of biofilm development (17). In contrast to Psl and Pel, alginate is a negatively charged polymer not required for initial attachment. However, it is important for later stages of biofilm development and a mucoid phenotype (18, 19). Alginate is only produced by some strains of P. aeruginosa and is not a critical matrix component of the laboratory strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 (20, 21).

Besides their roles as structural elements, exopolysaccharides have been linked to increased tolerance against antimicrobial agents, including antibiotics and disinfectants. Psl has been shown to promote resistance of P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms to several classes of antibiotics, particularly at the early stages of biofilm formation (21, 22), whereas Pel enhances P. aeruginosa resistance against aminoglycoside antibiotics (15).

Oxidative antimicrobial agents [e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl)] have been commonly used to eradicate microbes. Among them, NaOCl and its active ingredient, hypochlorous acid (HOCl), are potent and fast-acting reactive chlorine species (RCS) widely used in sanitation and disinfection purposes in industrial, domestic, and hospital settings. Furthermore, HOCl is also produced by the human immune system as a defense against invading pathogens (23, 24). The broad-spectrum antimicrobial action of NaOCl is due to its interaction with proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, affecting diverse cellular processes, such as membrane stabilization, protein and DNA synthesis, ATP production, and protein transport through the membrane (24).

In the present study, we analyzed the roles of exopolysaccharides in the tolerance of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to the oxidative stressors NaOCl and H2O2. Since alginate is not a critical EPS component in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (21, 25), we focused our analyses on the polysaccharides Psl and Pel. Using a set of PAO1 ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF mutants, we show that the absence of both polysaccharides leads to a 2.5-fold and 8-fold increase in susceptibility toward NaOCl and H2O2, respectively. Furthermore, we found that Pel plays a more significant role in NaOCl resistance than Psl.

RESULTS

Absence of Psl and Pel increases susceptibility of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to NaOCl

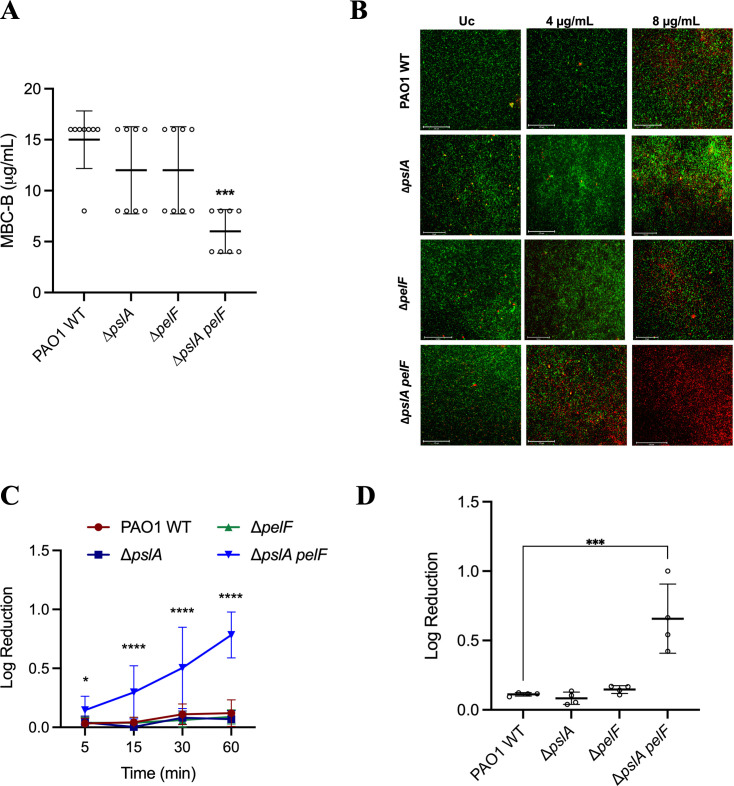

In order to study the involvement of Psl and Pel in NaOCl resistance, we performed the minimal bactericidal concentration in biofilms (MBC-B) assay in microtiter plates, as previously described (26), and challenged 24 h grown, static cultures of PAO1 wild-type (WT) and mutant strains ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF with increasing concentrations of NaOCl in the range of 2–1024 µg/mL (Fig. 1A). Of note, although the WT and ∆pelF mutant strains form similar biofilms under these growth conditions, ∆pslA and ∆pslA pelF show biofilm defects in flow chamber experiments and form only monolayer biofilms with the absence of microcolonies and reduced biomass compared with WT (25). This indicates that the cells analyzed in this particular assay likely represent a mixture of biofilm cells as well as loosely attached and sedimented cells. After removing planktonic cells and subsequent NaOCl treatment, we observed that 15 µg/mL of NaOCl was required to kill PAO1 WT cells. In contrast, only 6 µg/mL NaOCl was needed to eliminate cells of ∆pslA pelF, indicating a 2.5-fold increase in susceptibility. Both single-mutant ∆pslA and ∆pelF exhibited an MBC-B of 12 µg/mL, which was not statistically significant compared with the MBC-B of PAO1 WT.

Fig 1.

Susceptibility of PAO1 WT and PAO1 ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF to NaOCl. PAO1 WT and mutant strains were grown in polystyrene 96- or 12-well microplates for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium under static conditions and treated with NaOCl. (A) Susceptibility was evaluated by the MBC-B assay. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of PAO1 WT and ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF mutant biofilms treated with 4 µg/mL and 8 µg/mL NaOCl. Biofilms were grown in flat-bottom polystyrene 96-well microplates, treated with NaOCl at 4 and 8 µg/mL NaOCl 1 h at 37°C under static conditions, and stained with DNA-intercalating 1:1 Syto9 and PI dyes and visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 20× magnification. Untreated biofilms were used as controls. Pictures are representative of three independent experiments with three replicates. Scale bars represent 125 µm. (C) Time kill kinetics of PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF biofilms treated with 8 µg/mL NaOCl for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min. (D) Susceptibility of PAO1 WT and ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF mutant strains of biofilms using the agar colony biofilm model. P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF were grown overnight in LB media, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS, and the OD600nm was adjusted to 0.05 (5 × 107 CFU/mL). Ten microliters of bacterial culture were inoculated in the center of the semi-permeable membranes, and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C to allow biofilm establishment. Colony biofilms were treated with NaOCl at 32 µg/mL, which were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and plated following the drop plate method. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Uc: untreated control.

Since the ∆pslA and ∆pslA pelF mutants are known to have reduced biofilm biomass compared with the WT (15), we determined whether the increased susceptibility of ∆pslA pelF was due to the overall lower biomass of this mutant strain compared with the WT rather than to the effect of NaOCl. In accordance with (21, 21), we conducted an MBC-B experiment for cells grown for 6 h (attachment, early-stage biofilms, and lower biofilm biomass) and 24 h (mature biofilms and higher biofilm biomass) by treating the cells with NaOCl (2–1,024 µg/mL) for 1 h. For all tested strains, we received no statistically significant changes in the MBC-B for cells grown for 6 h and 24 h (Fig. S1). These results indicate that the simultaneous loss of Psl and Pel increases the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to NaOCl, and this increase in susceptibility is not due to lower biomass.

In contrast, analyses of planktonic cells revealed no differences in susceptibility and growth of PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF in the presence of 0.5, 1, and 2 µg/mL NaOCl (Table S1). Moreover, no differences in cell viability by CFU determination were obtained upon treatment of planktonic cells with 1.25 µg/mL NaOCl (Fig. S2).

Fluorescence microscopy, kill-curve kinetics, and agar colony model confirm the ∆pslA pelF phenotype

To further verify these results, we assessed the viability of P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF after a 1 h treatment with NaOCl using fluorescence microscopy in combination with LIVE/DEAD cell viability staining as well as time kill-curve kinetics. In these experiments, we added a washing step after initial growth and before treatment to remove all non-surface-adhered cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment of PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF with a sub-MBC-B concentration of NaOCl of 4 µg/mL did not affect cell viability, and the number of dead cells (red) in all three strains was low and comparable with the untreated controls. Furthermore, treatment with 8 µg/mL NaOCl also revealed a similar phenotype for PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF with a decrease in cell viability; however, many cells were still not affected. In contrast, most ∆pslA pelF double mutant cells were inactivated at 4 µg/mL NaOCl, and almost all cells were killed after treatment with 8 µg/mL (Fig. 1B). The reduction in the amount of live cells in the NaOCl-treated conditions, expressed in relative fluorescence units (RFU), was normalized based on the untreated control and is shown in Fig. S3a.

We then analyzed time kill-curve kinetics of adhered cells by determination of CFU numbers after NaOCl treatment over time (Fig. 1C) to show that ∆pslA pelF is more susceptible to NaOCl treatment in comparison to the WT and single knockout mutants. NaOCl at 8 µg/mL induced a significant reduction in the viable cell counts of the ∆pslA pelF double mutant (i.e., 0.15-fold, 0.3-fold, 0.5-fold, and 0.78-fold reduction in the log CFU after 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively), being the most pronounced effect. PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF did not present increased susceptibility to NaOCl treatment. After 60 min, a log reduction of 0.12, 0.07, and 0.09 was obtained for PAO1 WT, ∆pslA and ∆pelF, respectively.

Biofilms can be studied through many different methods. Therefore, to further confirm the results previously obtained, we utilized an agar colony biofilm model to evaluate the susceptibility of PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF to NaOCl. This model, in which bacteria are grown as biofilms on the surface of an agar plate, has been commonly used to evaluate the effect of antimicrobial agents (27, 28). PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF were grown on a polycarbonate membrane filter for 48 h at 37°C before being treated with NaOCl at 32 µg/mL for 1 h. This concentration represents a sub-lethal concentration of NaOCl found for the PAO1 WT strain in this biofilm model. In accordance with our initial microtiter plate experiments, the ∆pslA pelF double mutant presented an increased susceptibility to NaOCl compared with PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF strains (Fig. 1D). A log reduction of 0.66 in the number of viable cells was obtained for the ∆pslA pelF after treatment with NaOCl, whereas PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF presented a non-statistical reduction in cell viability of 0.11, 0.08, and 0.14, respectively (Fig. 1D).

Together, these results show that the simultaneous lack of Psl and Pel significantly increases the susceptibility of PAO1 to NaOCl.

Psl and Pel play additional roles in H2O2 susceptibility

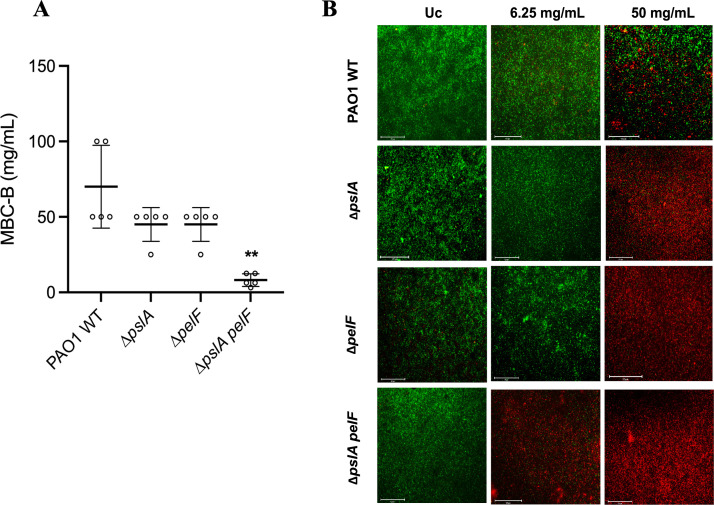

To evaluate whether the susceptibility phenotype obtained is hypochlorite-specific or if Psl and Pel are involved in a more general response to oxidative stressors, we performed MBC-B analyses in the presence of varying concentrations of H2O2 (1.95–100 mg/mL) to show that cells of ∆pslA ∆pelF were also more susceptible to this oxidant. As shown in Fig. 2A, PAO1 WT exhibited an MBC-B of 70 mg/mL, which was more than 8-fold more resistant to H2O2 treatment compared with ∆pslA pelF with an MBC-B of 8.125 mg/mL. A less pronounced and not statistically significant increase in susceptibility to H2O2 was detected for ∆pslA and ∆pelF, with an MBC-B of 45 mg/mL for both strains.

Fig 2.

Susceptibility of PAO1 WT and PAO1 ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF biofilms to H2O2. PAO1 WT and mutant strains were grown in polystyrene 96- or 12-well microplates for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium under static conditions and treated with H2O2. (A) Susceptibility was evaluated by the MBC-B assay. (B) Microscopy pictures of PAO1 WT and ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF mutant biofilms treated with 6,250 µg/mL and 50,000 µg/ml H2O2. Biofilms were grown for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium in flat-bottom polystyrene 96-well microplates. H2O2 was diluted in BM2, and biofilms were treated for 1 h at 37°C under static conditions. Biofilms were stained with DNA-intercalating 1:1 Syto9 and PI dyes and visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 20× magnification. Untreated biofilms were used as the positive control. Pictures are representative of three independent experiments with three replicates each. Scale bars represent 125 µm. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01. Uc: untreated control.

In addition, we used fluorescence microscopy and LIVE/DEAD staining to analyze cell viability after the treatment with H2O2 at 6.25 and 50 mg/mL H2O2 for 1 h. Treatment with 6.25 mg/mL H2O2 killed nearly all cells of ∆pslA pelF. However, PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, and ∆pelF cells were not affected by this concentration of H2O2. Treatment with 50 mg/mL H2O2 revealed the complete killing of ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF, whereas PAO1 WT still showed a significant number of living cells (Fig. 2B). The reduction in the number of live cells (green) in the NaOCl-treated conditions, expressed in relative fluorescence units (RFU), was normalized based on the untreated control and is shown in Fig. S3b. These data are in accordance with our results obtained for NaOCl, suggesting that Psl and Pel provide protection against different oxidative stressors.

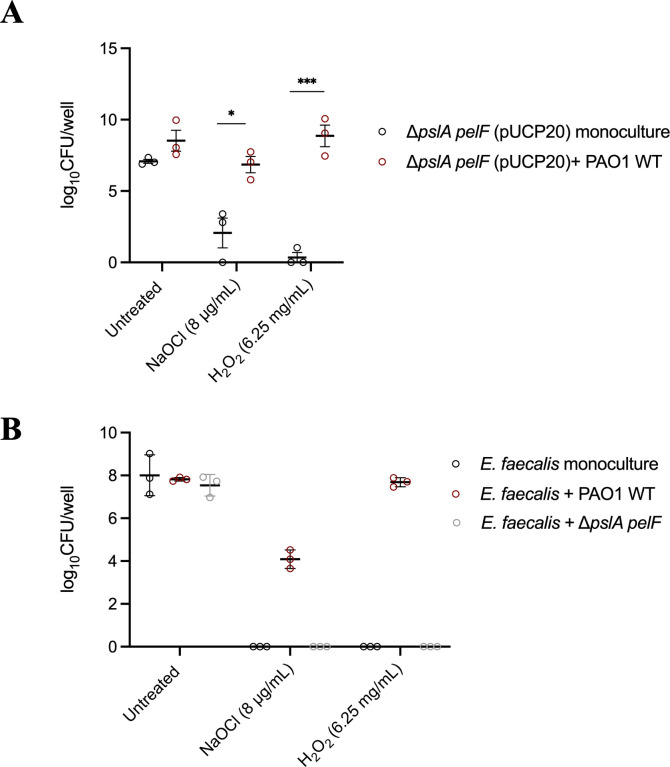

Psl and Pel protects ∆pslA pelF and Enterococcus faecalis against oxidizing agents

In their natural environment, biofilms are predominantly found as heterogeneous and often multi-species populations, which confer many advantages to the bacteria, including the ability to share resources and increased resistance to antimicrobial treatment (29). With this in mind, we evaluated if Psl and Pel produced by the PAO1 WT could influence the survival of the Psl- and Pel-deficient strain ∆pslA pelF as well as E. faecalis, an opportunistic Gram-positive pathogen often isolated together with P. aeruginosa from biofilm infections (30).

First, plasmid pJN105 (gentamicin resistance) was introduced into PAO1 WT and plasmid pUCP20 (carbenicillin resistance) into ∆pslA pelF in order to distinguish between both strains in our co-culture analyses. Biofilms formed by PAO1 WT (pJN105) and ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20) were then cultured in 12-well microplates in BM2 biofilm medium for 24 h at 37°C, treated with NaOCl at 8 µg/mL or H2O2 at 6.25 mg/mL for 1 h, and susceptibility was determined by CFU counts. These analyses showed an increase in the amount of viable ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20) cells when this strain was co-cultured together with PAO1 WT (pJN105) (Fig. 3A). For NaOCl treatment, a 5-fold increase in the number of viable cells was obtained, whereas for H2O2, the co-culture of PAO1 WT (pJN105) with ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20) increased the viability of the mutant by 25-fold.

Fig 3.

Viability of (A) ∆pslA pelF and (B) E. faecalis cells after the treatment with NaOCl and H2O2 as monoculture or mixed culture. (A) CFU numbers of ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20) cells after NaOCl and H2O2 treatment of mono- and co-culture biofilms with PAO1 WT (pJN105). Mono- and co-culture biofilms were grown for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium in flat-bottom polystyrene 12-well microplates. Biofilms were washed and treated with NaOCl or H2O2 diluted in BM2 at 8 µg/mL and 6.25 mg/mL, respectively, and biofilms were treated for 1 h at 37°C under static conditions. Then, sodium thiosulfate at 10 mM was added to NaOCl-treated biofilms, and CFU was determined by the drop method. For PAO1 WT (pJN105) was selected in LB agar plates supplemented with 30 µg/mL gentamicin, and ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20) cells were selected in LB agar plates supplemented with 300 µg/mL carbenicillin. (B) CFU numbers of E. faecalis cells after the treatment with NaOCl and H2O2 as monoculture or mixed culture with PAO1 WT or ∆pslA pelF. Mono- and co-culture biofilms were grown for 24 h at 37°C in DMEM in flat-bottom polystyrene 12-well microplates. Biofilms were washed and treated with NaOCl or H2O2 diluted in BM2 at 8 µg/mL and 6.25 mg/mL, respectively, and biofilms were treated for 1 h at 37°C under static conditions. Then, sodium thiosulfate at 10 mM was added to NaOCl-treated biofilms, and CFU was determined by the drop method. P. aeruginosa was selected using BM2 agar plates, and E. faecalis was selected using LB plates supplemented with 5 µg/mL gentamicin and 12 µg/mL Polymyxin B. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA or t-test for comparison between two groups. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

The co-culture of P. aeruginosa with E. faecalis was performed using a co-culture model developed in our lab, in which biofilms were grown for 24 h at 37°C in DMEM, P. aeruginosa was selected using BM2 agar plates, and E. faecalis was selected using LB agar plates supplemented with 5 µg/mL gentamicin and 12 µg/mL polymyxin B. When grown as a mono-species biofilm, no E. faecalis cells were detected after the treatment with NaOCl and H2O2, whereas in the co-culture together with PAO1 WT, E. faecalis was able to survive the toxic effect of both oxidizing agents, presenting log10 CFU/well of 4 and 7, respectively (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, the mixed culture biofilm formed by ∆pslA pelF and E. faecalis did not affect the survival rate of E. faecalis to NaOCl and H2O2 stress, in which, as in the monoculture, no viable cells were detected after the 1 h treatment with these oxidants.

These results indicate that the exopolysaccharides Psl and Pel produced by P. aeruginosa protect Psl/Pel-negative strains of P. aeruginosa as well as E. faecalis against NaOCl and H2O2 stress.

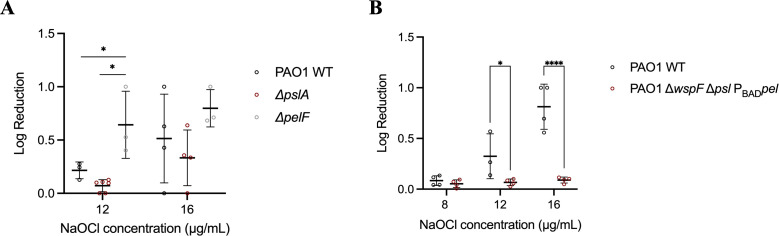

Pel increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to NaOCl

To further investigate potential differences between Psl and Pel in resistance of P. aeruginosa to NaOCl, we analyzed cell viability of the PAO1 ∆pslA and ∆pelF mutant strains treated with NaOCl at 12 and 16 µg/mL, respectively, for 1 h. A log reduction of 0.64 in cell viability was observed for the treatment of P. aeruginosa ∆pelF with 12 µg/mL NaOCl, whereas for PAO1 WT and ∆pslA, a reduction of 0.21 and 0.071 in the log of CFU/well, respectively, was obtained after the treatment with 12 µg/mL NaOCl for 1 h (Fig. 4A). No statistical difference was found for the treatment with 16 µg/mL.

Fig 4.

Susceptibility of (A) PAO1 WT and PAO1 mutants ∆pslA and ∆pelF and (B) PAO1 ΔwspF Δpsl PBADpel biofilms to NaOCl. PAO1 WT and mutant strains were grown in polystyrene 12-well microplates for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium under static conditions and treated with NaOCl at 8, 12, or 16 µg/mL. Then, 10 mM sodium thiosulfate was added to quench the toxic effect of the remaining NaOCl, and CFU was determined by the drop method. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or t-test for comparison between two groups. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001.

Based on these results, we then analyzed if the overproduction of Pel would result in reduced susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to NaOCl. For this, the Pel overproducing strain PAO1 ΔwspF Δpsl PBADpel (31) was treated with NaOCl at 8, 12, and 16 µg/mL for 1 h, and cell viability was assessed by CFU determination to show that ΔwspF Δpsl PBADpel indeed exhibited increased tolerance to NaOCl in comparison to PAO1 WT (Fig. 4B).

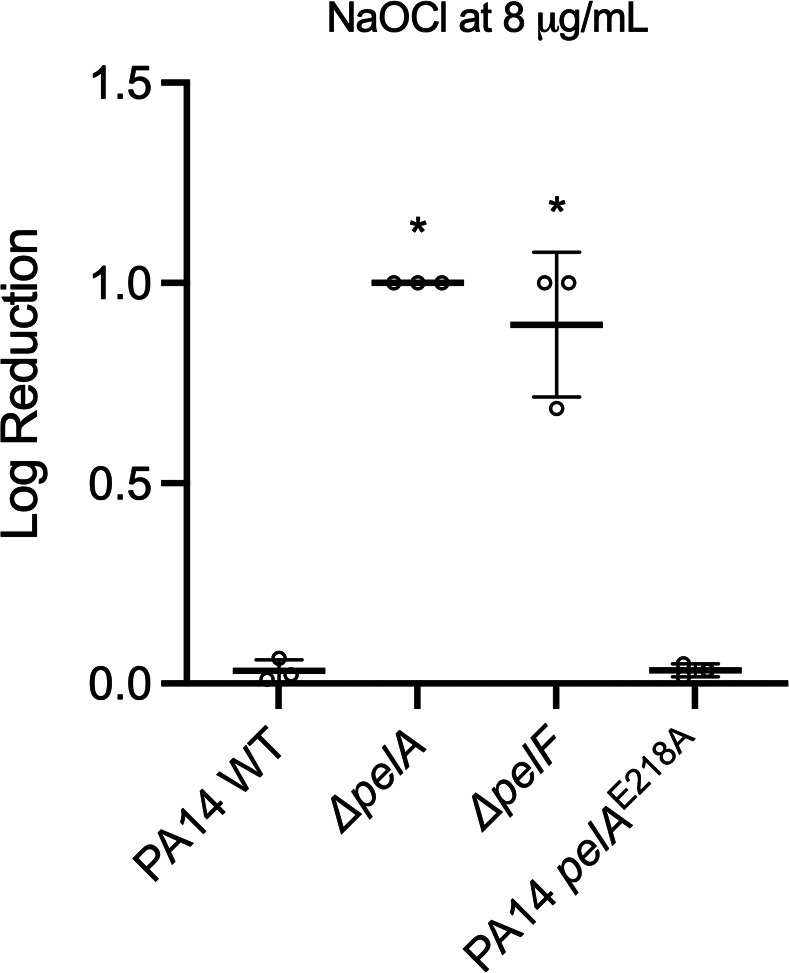

Pel increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa PA14 to NaOCl independently of its structure

P. aeruginosa strain PA14 synthesizes Pel but does not produce Psl (32). With this in mind, we investigated if additional knockout of Pel in PA14 mutant strains ∆pelA and ∆pelF would attenuate NaOCl susceptibility in P. aeruginosa PA14. After treatment with 8 µg/mL NaOCl, we observed that PA14 ∆pelA and ∆pelF presented a 1 and 0.89 log reduction in cell viability, respectively, which was 33-fold more killing in comparison to cells of PA14 WT (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Susceptibility of PA14 WT and PA14 mutants ∆pelA, ∆pelF, and PA14 pelAE218A biofilms to NaOCl. PAO1 WT and mutant strains were grown in polystyrene 96- or 12-well microplates for 24 h at 25°C in BM2 biofilm medium under static conditions and treated with NaOCl at 8 µg/mL. Then, 10 mM sodium thiosulfate was added to quench the toxic effect of the remaining NaOCl, and CFU was determined by the drop method. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05.

As Pel can be found in both cell-associated and cell-free forms (33), we investigated if the localization of the polymer played differential roles in NaOCl resistance. For this, we tested the PA14 pelAE218A strain, a mutant in which the PelA hydrolase activity was disrupted by using the inactive catalytic point variant E218A (34). In the absence of hydrolase activity, Pel was found almost exclusively in the cell-associated fraction in the PAO1 Pel overexpressing strain compared with the parental strain (34). As shown in Fig. 5, cell viability analyzed by CFU determination upon treatment with 8 µg/mL NaOCl for 1 h resulted in a 0.033 reduction in the cell viability of PA14 pelAE218A, a phenotype similar to that obtained for the PA14 WT (0.032 log reduction). The PA14 pelAE218A analysis suggests that the distribution of Pel between the two forms (i.e., cell-associated and cell-free) does not influence the NaOCl susceptibility of PA14.

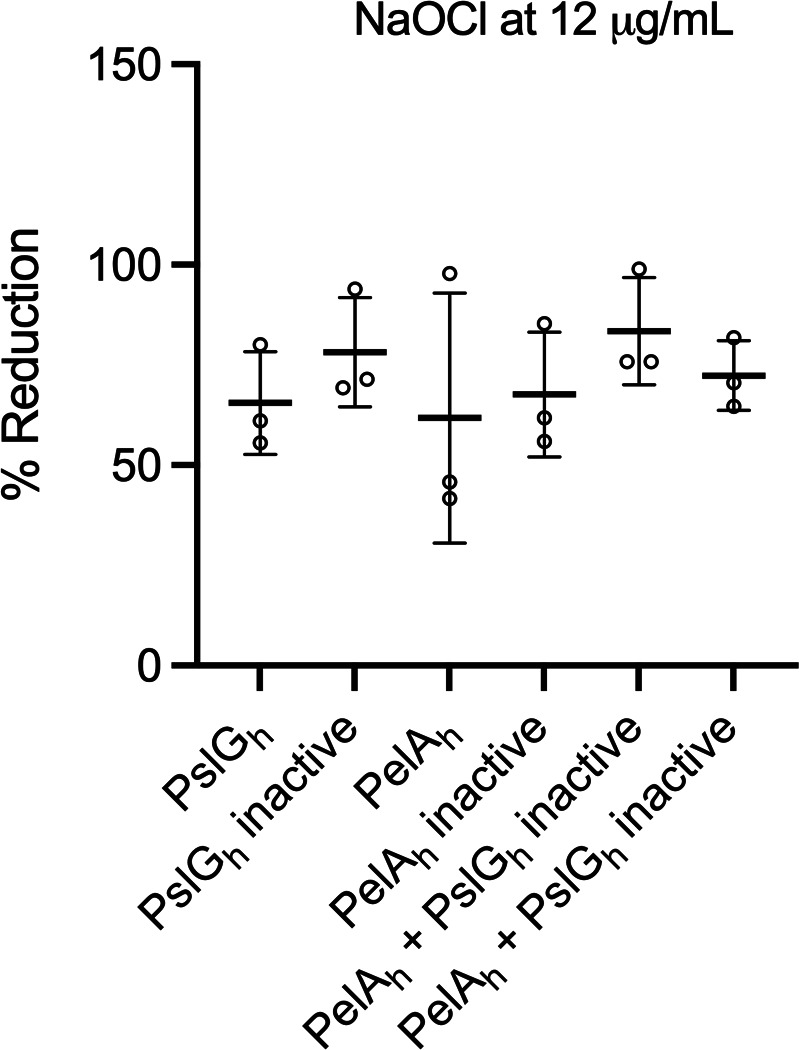

Treatment of PAO1 biofilms with glycoside hydrolases PslGh and PelAh does not affect NaOCl susceptibility

Previous studies have shown that the glycoside hydrolases PslG and PelA (PslGh and PelAh, respectively) degrade Psl and Pel, respectively (35), and contribute to the killing effect of antibiotics such as tobramycin, Polymyxin B, colistin, and neomycin (36). We, therefore, aimed to evaluate if treating PAO1 WT biofilms with PslGh and PelAh would influence the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to NaOCl. First, hydrolase activities were confirmed by analyzing the biofilm biomass of PAO1 WT biofilms treated with active or heat-inactive hydrolases (Fig. S4). Then, to evaluate the effect of the hydrolases on NaOCl susceptibility, PAO1 WT biofilms were treated with 2 µM of PslGh, PelAh, or the combination of PslGh and PelAh for 1 h, followed by treatment with NaOCl at 12 µg/mL for 1 h. Cell viability analyses revealed no statistical difference between the PslGh-, PelAh-, and PslGh + PelAh-treated biofilms compared with those treated with inactive enzymes (Fig. 6). These results suggest that degraded polysaccharides also protect P. aeruginosa against NaOCl. In this context, upon degradation by hydrolases, polysaccharide fragments would still be available in the culture supernatant to react with NaOCl, as opposed to the results observed for the mutant strains, which lack the respective polysaccharides.

Fig 6.

NaOCl susceptibility of PAO1 WT biofilms treated with the glycoside hydrolases PslGh and PelAh. PAO1 WT biofilms were grown in polystyrene 12-well microplates for 24 h at 37°C in BM2 biofilm medium under static conditions and treated with 2 µM of PslGh, PelAh, or a combination of PslGh and PelAh for 1 h at 25°C. Then, NaOCl at 12 µg/mL was added for 1 h, followed by 10 mM sodium thiosulfate to quench the toxic effect of the remaining NaOCl, and CFU was determined by the drop method. Heat-inactive enzymes were used as a control. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria have developed a variety of mechanisms to resist the damage caused by oxidizing agents, such as the expression of detoxifying enzymes (e.g., catalase and peroxidase), protein and DNA repair systems, activation of transcriptional regulators (e.g., OxyR, SoxR, and OhrR), and the formation of biofilms (24, 37). Previously, we and others have shown that sub-lethal concentrations of oxidants such as NaOCl stimulate biofilm formation (38) and that this stimulation is mediated in several different ways, including changes in cell morphology (e.g., increasing membrane hydrophobicity) (39, 40) and synthesis of cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP) and EPS matrix components, mainly exopolysaccharides (38, 41–43). In this study, we demonstrate that the simultaneous inactivation of the exopolysaccharides Psl and Pel in P. aeruginosa PAO1 mutant strain ∆pslA pelF resulted in increased susceptibility to oxidizing agents compared with the PAO1 WT and ∆pslA and ∆pelF single mutant strains (Fig. 1 and 2). The PAO1 mutant strains used in this study were previously characterized (44). Considering that cells of ∆psl and ∆psl pel mutants do not form mature biofilms but are still able to adhere to surfaces and form monolayer biofilms with reduced biomass (25), we used a variety of different methods and approaches to study the roles of Psl and Pel in oxidative stress resistance of P. aeruginosa. These experiments confirmed the increased susceptibility of the double mutant ∆pslA pelF to NaOCl stress compared with the WT and single-knockout mutant strains and showed that compared with Psl, Pel plays a more significant role in oxidative stress resistance in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1).

Furthermore, since NaOCl resistance has been shown to be mediated by a combination of specific and general resistance mechanisms (24, 37, 45, 46), we also tested if the loss of Psl and Pel in P. aeruginosa PAO1 increases the susceptibility of biofilms to H2O2, a widely used reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a component of the innate immune system (47). As obtained for NaOCl, the absence of both polysaccharides in the ∆pslA pelF double mutant increased its susceptibility to H2O2 compared with the WT and single mutant strains (Fig. 2), indicating, therefore, that the exopolysaccharides of the biofilm matrix of P. aeruginosa function as a general resistance mechanism employed by P. aeruginosa against oxidizing agents.

The EPS matrix is a dynamic and complex space providing the infrastructure for microbial communities like biofilms. Previous research has demonstrated many functions for the EPS matrix, including adhesion, retention of water, nutrient source, exchange of genetic information, and export of cell components, among many others (48). In addition, the EPS also functions as a protective, physical, and chemical barrier, contributing to the increased stress and antibiotic tolerance of biofilms in many bacterial species, including P. aeruginosa (5, 15, 21, 44, 48–50), Staphylococcus sp (51, 52), and Escherichia coli (53, 54). In particular, the polysaccharides and proteins within the EPS matrix are responsible for the increased antimicrobial resistance of biofilms (48).

It has been demonstrated that the polysaccharides Psl and Pel contribute to the increased antimicrobial tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms. Although their involvement in resistance toward antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, colistin, and ciprofloxacin (15, 21, 44, 49) has been well documented, the effects of Psl and Pel on resistance toward oxidative stress and oxidizing agents such as NaOCl and H2O2 have been poorly investigated thus far. A recent study found that Psl and Pel are involved in the resistance of P. aeruginosa submerged and air-liquid interface biofilms to lethal doses of ultraviolet-A (UVA) radiation, H2O2, and NaOCl (55). However, this study was predominantly focused on UVA radiation, and results for H2O2 and NaOCl were limited.

The restricted penetration of molecules into biofilms has been suggested as an important mechanism involved in EPS-mediated resistance (50, 54). For example, tobramycin, a positively charged antibiotic, has been shown to ionically interact with negatively charged components of the biofilm matrix of P. aeruginosa at the periphery, impairing its penetration into these structures, an effect that depends on the structure and maturity of the biofilms (56). In accordance with our results, Yang and co-workers showed that treatment with 20 µg/mL tobramycin had the strongest effect on biofilms formed by the Psl- and Pel-deficient PAO1 double mutant ∆pelA pslBCD, killing almost all cells within this biofilm after 24 h of treatment. A large portion of cells was also killed in the ∆pslBCD biofilms, whereas only some cells in the surface layer of PAO1 WT and ∆pelA biofilms were killed by tobramycin (49). Indeed, Billings and colleagues obtained similar results when challenging biofilms of PAO1 WT, a Psl- and a Pel-deficient mutant with antibiotics, with the Psl mutant showing the strongest increase in susceptibility toward tobramycin, colistin, polymyxin B, and ciprofloxacin (21). By adding NaCl to P. aeruginosa biofilms, the authors showed that Psl sequesters the positively charged antibiotics colistin, polymyxin B, and tobramycin by electrostatic interactions (21). In addition, it has been previously shown that overproduction of Psl and Pel increased the resistance of P. aeruginosa aggregates to tobramycin and ciprofloxacin. In contrast, the deletion of these genes increased the susceptibility of aggregates to these antibiotics. This phenotype was attributed to changes in the bacterial physiology of aggregates, e.g., limited penetration of nutrients and oxygen induced by the matrix components (57). On the other hand, a recent study using an agar-embedded P. aeruginosa aggregate model showed that Psl and Pel did not protect P. aeruginosa aggregates against tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, and meropenem under these culture conditions (28). The authors suggested that this is most likely due to oxygen limitation and that Psl and Pel affect the metabolic state of the bacteria, which influences antibiotic susceptibility (28). In a different study, Psl production was found to promote resistance of P. aeruginosa to the surfactant polysorbate 80 (PS80) (32). Overall, our data are in line with these previous findings about the contribution of the EPS components Psl and Pel to antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa.

Interestingly, only the ∆pslA pelF double mutant but not the corresponding single Psl and Pel mutants showed a statistically significant difference in susceptibility in the MBC-B assay and cell viability analyses when exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of oxidants in comparison to WT cells. It has been shown that Psl and Pel present redundancy during biofilm development, that is, one polysaccharide can compensate for the lack of the other (25, 33). For example, Ghafoor and colleagues showed that cells of the ∆pslA mutant produced significantly more Pel than WT cells (44). It could explain our resistance phenotypes, in which no significant difference was observed when the ∆pslA and ∆pelF mutants were exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of NaOCl. Further analyses using more defined concentrations of NaOCl showed that Pel increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa at 12 µg/mL NaOCl. In accordance with our results (55, 55), we found that the PAO1 ∆pel, as well as the double mutant ∆psl pel, were consistently more susceptible to NaOCl than the ∆psl deficient strain. In our study, the importance of Pel in the NaOCl survival of P. aeruginosa was also found for the PA14 strain, indicating that this is not a strain-specific phenotype.

Polysaccharides can be found as cell-associated or cell-free molecules (33). Although it is believed that there is a similarity between these two forms, only the composition of the cell-free form of Pel has been determined (16, 34, 58). The cell-free form of Pel contributes to the mechanical characteristics of P. aeruginosa biofilms and reduces P. aeruginosa virulence in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster infection models (34). We then showed that the presence of mostly cell-associated Pel (due to the inactivation of PelA hydrolase in the PA14 pelE218A strain) did not attenuate the protection against NaOCl, indicating that the form of Pel does not impact NaOCl resistance in P. aeruginosa.

We then hypothesized that the exopolysaccharides of the EPS matrix promote resistance to NaOCl by reacting with this oxidant. Indeed, it has been shown that HOCl, the active ingredient of NaOCl, reacts with polysaccharides and sugars, preferably in an N-acetyl group (24, 37, 59, 60). For example, HOCl reacts with hyaluronic acid, and this reaction appears to be localized at the N-acetylglucosamine sugar rings (59). Furthermore, after proteins, the nitrogen-containing amine groups are considered the secondary targets of HOCl (61). These structures and groups can be found in the structure of Pel, which is composed of partially acetylated α−1,4-N-acetylgalactosamine comprised predominantly of dimeric repeats of galactosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine (16). The biochemistry of these interactions will be analyzed in more detail in the following study.

The use of glycoside hydrolases encoded in the psl and pel operon, respectively (PslGh and PelAh, respectively), to degrade Psl and Pel has been shown to potentiate the killing effects of antibiotics such as colistin (35), tobramycin, gentamicin, polymyxin B, and neomycin by improving their penetration into the biofilm (36). Furthermore, these enzymes increased neutrophil response against P. aeruginosa and the use of topical PslGh to treat wound infections increased bacterial clearance and the antimicrobial effect of tobramycin (36). Additionally, treatment of P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus with the glycoside hydrolases cellulase and α-amylase disrupted the biofilms and improved the antimicrobial effect of gentamicin (62). In this study, the treatment with PslGh did not provoke a significant reduction in the susceptibility of PAO1 WT biofilms to NaOCl. Based on our previous results, a slight but not significant reduction in susceptibility upon PslGh treatment followed by NaOCl exposure was expected. Interestingly, degrading Pel with PelAh produced a similar effect, in which no increase in the susceptibility of PAO1 WT biofilms to NaOCl was detected compared with the inactive enzyme control, as observed in our previous analyses using ∆pel mutant strains. Since Pel is composed of galactosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine (16), we hypothesize that although PelAh cleaves this polysaccharide, amine groups are widely available to quench NaOCl and would still be a substrate for this disinfectant, protecting the biofilms against reactive chlorine stress. Therefore, these results suggest that Pel also protects P. aeruginosa biofilms even when the matrix is disrupted.

Growing as multi-species populations is the predominant form of biofilms in nature and confers many advantages for these communities (29). Among them, the species within muti-species populations can share resources such as nutrients and molecules (29) and present increased resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants (63–65). In this context, Psl and Pel play roles in the competition of PAO1 WT and S. aureus when grown as dual-species biofilms (55). Furthermore, Psl and Pel produced by P. aeruginosa protected E. coli and S. aureus against the killing effect of colistin (21). In accordance, we found that Psl and Pel produced by PAO1 WT protect non-exopolysaccharides-producing strains such as the ∆pslA pel double mutant as well as E. faecalis, reinforcing the function of these matrix components as a community good.

The present findings demonstrate that the EPS matrix and the polysaccharide Pel play a role in resistance to oxidizing agents in P. aeruginosa. In this context, we hypothesize that the reaction of Pel with NaOCl, for example, could provide biofilm cells more time to develop and activate other defense mechanisms, e.g., synthesis of detoxifying enzymes. Future research will focus on characterizing the exact biochemical interactions of Pel with strong oxidants such as NaOCl and H2O2 to understand the precise molecular mechanisms of resistance. Understanding the mechanisms by which bacteria escape antimicrobial agents, including strong oxidants, is urgently needed in the fight against antimicrobial resistance and will help in developing new strategies to eliminate resistant strains in any environmental, industrial, and clinical settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Overnight bacterial cultures were grown in LB at 37°C, unless otherwise stated, washed, and diluted in BM2 minimal media [7 mM (NH4)2SO4, 40 mM K2HPO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.01 mM FeSO4, pH 7.0]. Biofilms were grown in BM2 biofilm medium [i.e., BM2 supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) casamino acids (CAA)] (66, 67) for 24 h at 37°C under static conditions unless otherwise stated. Arabinose at 0.5% (wt/vol) was used to induce the production of Pel in the PAO1 ΔwspF Δpsl PBADpel strain. PA14 cultures and biofilms were grown at 25°C, since lower temperatures support Pel production in PA14. Pel production was monitored in PA14 WT at 25°C and in PAO1 WT at 37°C by dot blot (Fig. S5).

Free chlorine concentration of NaOCl solutions was determined weekly using DPD Free Chlorine Powder Packs (Thermo Scientific Orion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oxidative stress experiments were conducted using BM2 minimal medium to mitigate side reactions between NaOCl and media components. Furthermore, the amount of total RCS remaining in the media after mixing NaOCl and BM2 was determined as previously described (68), and no significant reduction was observed, whereas LB, used as a control, completely quenched NaOCl.

Minimal bactericidal concentration of biofilms (MBC-B) assay

The MBC-B was determined as described previously (26). Briefly, cells were grown overnight at 37°C at 220 rpm, collected by centrifugation, washed twice, and resuspended in BM2. The bacterial suspension was then diluted in BM2 biofilm medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm) of 0.1 (18) to obtain approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL. An aliquot of 100 µL was placed into 96-well microtiter plates, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C under static conditions to allow biofilm formation. The supernatant was removed, and 200 µL of NaOCl (2–1,024 µg/mL) or H2O2 (1.95–100 mg/mL) diluted in BM2 was added to the pre-formed biofilms. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, unless otherwise stated, the supernatant was removed, and 100 µL of LB media was added to the wells, followed by incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Finally, the 96-well microplates were stamped and transferred on a 2% (wt/vol) LB agar plate and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The MBC-B was considered the lowest concentration of oxidizing agent where no bacterial growth was observed.

Fluorescence microscopy

To visualize the effects of NaOCl and H2O2 on cells, we conducted fluorescence microscopy using the LIVE/DEADTM BacLightTM Bacterial viability kit (1:1 Syto9:PI) (InvitrogenTM Thermo Fisher Scientific). Overnight cultures were washed twice and diluted in BM2 biofilm medium to an OD600nm of 0.1 and transferred to flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microplates, which were incubated under static conditions for 24 h at 37°C to allow adherence and biofilm formation. Biofilms were carefully washed with BM2 minimal medium to remove planktonic cells and treated with NaOCl (4 and 8 µg/mL) or H2O2 (6.25 and 50 mg/mL) for 1 h at 37°C. Untreated biofilms were used as the growth control. Then, 10 mM of sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) (69) was added to the NaOCl-treated biofilms to quench the oxidizing effect of NaOCl, and the biofilms were subsequently stained with a 1:1 LIVE/DEADTM BacLightTM and incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature (70). Pictures were taken from three independent experiments with three replicates using an EVOS FL Auto 2 microscope (Thermofisher). RFU was quantified using the software Fiji.

Time-kill kinetics experiments and CFU determination

The viability of P. aeruginosa biofilm cells after the treatment with NaOCl was assessed by CFU determination. P. aeruginosa strains were grown overnight in LB at 37°C and 220 rpm, washed twice, and resuspended in BM2 biofilm medium to an OD600nm of 0.1. Aliquots of 1 mL were transferred to 12-well microtiter plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C under static conditions to allow biofilm formation. P. aeruginosa PA14 strains were grown at 25°C. Then, the media was removed, and biofilms were carefully washed with BM2 and treated with NaOCl for 1 h at 37°C. Na2O2S3 at 10 mM was added to the samples to quench the effect of the remaining NaOCl (69), and biofilm cells were collected by scraping. Untreated biofilms were used as the positive control. Samples were serially diluted and plated out on LB agar plates using the drop plate method (71).

Co-culture biofilms of P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT with E. faecalis and ∆pslA pelF

Co-culture of PAO1 WT (pJN105) and ∆pslA pelF (pUCP20): Plasmids pJN105 and pUCP20 were transferred into PAO1 WT and ∆pslA pelF, respectively, by electroporation (72). P. aeruginosa was grown overnight in LB containing 30 µg/mL gentamicin or 300 µg/mL carbenicillin, respectively. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed twice, and resuspended in BM2. Bacterial suspensions were diluted in BM2 biofilm medium to an OD600nm of 0.05. Mixed biofilms were produced by mixing 1:1 of 0.05 OD600nm of PAO1-pJN105 and ∆pslA pelF-pUCP20. Monoculture biofilms were prepared and used as controls. One milliliter of mono or mixed cultures was transferred to 12-well microplates, which were incubated for 24 h at 37°C under static conditions to allow biofilm establishment and treated with NaOCl at 8 µg/mL or H2O2 at 6.25 mg/mL for 1 h at 37°C. Na2S2O3 was added to the NaOCl-treated biofilms, the cells were scraped, and the CFU/well was determined by the drop plate method (71). PAO1 WT was selected by growth on agar plates containing 30 µg/mL gentamicin, and ∆pslA pelF was selected by growth on agar plates with 300 µg/mL carbenicillin.

Co-culture of PAO1 WT or ∆pslA pelF with E. faecalis: Overnight cells were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with PBS. E. faecalis was diluted in DMEM to an OD600nm of 0.01. PAO1 WT and ∆pslA pelF were diluted to an OD600nm of 0.05, followed by a 1/1,000 dilution. Mixed biofilms were prepared by mixing E. faecalis at 0.01 OD600nm with a 1/50,000 dilution of PAO1 WT or ∆pslA pelF in DMEM. Monocultures were prepared and used as controls. One milliliter of mixed cultures or monocultures was added to 12-well microplates, which were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and static conditions. The biofilms were then washed and treated with NaOCl at 8 µg/mL and H2O2 at 6.25 mg/mL for 1 h at 37°C. Na2S2O3 was added to the NaOCl-treated biofilms, which were scraped, and the CFU/well was determined by the drop plate method (71). LB agar plates supplemented with 5 µg/mL gentamicin and 12 µg/mL polymyxin B were used to select E. faecalis, and P. aeruginosa was selected using BM2 agar plates.

Colony biofilm assay

Colony biofilm assay was performed as previously described (27, 73), with slight modifications. P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT, ∆pslA, ∆pelF, and ∆pslA pelF were grown overnight in LB media under shaking conditions (220 rpm) at 37°C. Then, overnight bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed, and the OD600nm was adjusted to 0.05 (5 × 107 CFU/mL) in PBS. Then, 25 mm polycarbonate membranes with a pore size of 0.22 µm were placed in agar plates using sterilized forceps. Ten microliters of bacterial culture were inoculated in the center of the semi-permeable membranes, and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Then, using sterile forceps, the membranes were removed from the agar plates and transferred to 50 mL Falcon tubes containing PBS for the untreated control or NaOCl at 32 µg/mL, which were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Ten mM Na2S2O3 was added to quench the toxic effect of NaOCl, and cells were vigorously vortexed for two pulses of 1 min each. Serial dilutions were prepared, and the samples were plated out on LB agar plates following the drop plate method (71).

Recombinant GH expression and purification

His-tagged recombinant PelAh and PslGh were expressed in Clearcoli® cells grown in Terrific Broth (Bioshop) or autoinduction medium with 50 µg/mL Kanamycin (Biobasic) as previously described (35, 74). Bacterial cultures in Terrific Broth were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Biobasic) when the cells reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.2 to 1.4. The cells were incubated post-induction overnight at 18°C with shaking at 200 rpm before being harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Both proteins were purified using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid columns (GE Healthcare) followed by buffer exchange as previously described (74).

Treatment of biofilms with hydrolases

We investigated the effect of NaOCl on P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms after degrading Psl and Pel with the glycoside hydrolases PslG and PelA (PslGh and PelAh, respectively) (36). PAO1 overnight cells were washed, the OD600nm was adjusted to 0.1 (1 × 108 CFU/mL) in BM2 biofilm medium, and 1 mL was transferred to 12-well microtiter plates for 24 h at 37°C under static conditions. Then, biofilms were carefully washed and treated with 2 µM PslGh or PelAh for 1 h at 25°C, followed by treatment with NaOCl at 12 µg/mL for 1 h at 37°C. Na2O2S3 at 10 mM was added to the samples to quench the effect of the remaining NaOCl (69), and biofilm cells were collected by scraping and plated out on LB agar plates following the drop plate method (71). Heat-inactive enzymes were used as controls.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed in at least three independent experiments. Data are presented as log10 reduction (75, 76) calculated based on the untreated and NaOCl-treated conditions and compared with PAO1 or PA14 WT data, which were used as the positive control. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9.0 (San Diego, USA). The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data normality was confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk or D'Agostino-Pearson test. Then, parametric data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey or Dunnett’s post-test for multiple comparisons or Student’s t-test for comparison between two groups. On the other hand, non-parametric distribution was evaluated by the t-test and Mann-Whitney test for comparison between the two groups. Results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Bernd Rehm, Dr. Erum Razvi, and Dr. Matthew Parsek for providing strains used in this study.

This research was funded by the Carleton University, Ontario Graduate Scholarship, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC, RGPIN-2019–06335), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR FDN 143327 and CRC Tier I chair 2006–2020).

Contributor Information

Joerg Overhage, Email: joerg.overhage@carleton.ca.

Emily Weinert, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00922-24.

Supplemental tables, figures, and methods.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Azam MW, Khan AU. 2019. Updates on the pathogenicity status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Drug Discov Today 24:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thi MTT, Wibowo D, Rehm BHA. 2020. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Int J Mol Sci 21:8671. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . 2017. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 4. Moradali MF, Ghods S, Rehm BHA. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: a paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:39. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flemming H-C, van Hullebusch ED, Neu TR, Nielsen PH, Seviour T, Stoodley P, Wingender J, Wuertz S. 2023. The biofilm matrix: multitasking in a shared space. Nat Rev Microbiol 21:70–86. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00791-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kragh KN, Tolker-Nielsen T, Lichtenberg M. 2023. The non-attached biofilm aggregate. Commun Biol 6:898. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-05281-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alhede M, Kragh KN, Qvortrup K, Allesen-Holm M, van Gennip M, Christensen LD, Jensen PØ, Nielsen AK, Parsek M, Wozniak D, Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T, Høiby N, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T. 2011. Phenotypes of non-attached Pseudomonas aeruginosa aggregates resemble surface attached biofilm. PLoS One 6:e27943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frieri M, Kumar K, Boutin A. 2017. Antibiotic resistance. J Infect Public Health 10:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin T-J, Cheng Z. 2019. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv 37:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maunders E, Welch M. 2017. Matrix exopolysaccharides; the sticky side of biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx120. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jackson KD, Starkey M, Kremer S, Parsek MR, Wozniak DJ. 2004. Identification of psl, a locus encoding a potential exopolysaccharide that is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 186:4466–4475. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4466-4475.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma L, Jackson KD, Landry RM, Parsek MR, Wozniak DJ. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa conditional psl variants reveals roles for the psl polysaccharide in adhesion and maintaining biofilm structure postattachment. J Bacteriol 188:8213–8221. doi: 10.1128/JB.01202-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma L, Conover M, Lu H, Parsek MR, Bayles K, Wozniak DJ. 2009. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000354. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Overhage J, Schemionek M, Webb JS, Rehm BHA. 2005. Expression of the psl operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms: PslA performs an essential function in biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4407–4413. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4407-4413.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colvin KM, Gordon VD, Murakami K, Borlee BR, Wozniak DJ, Wong GCL, Parsek MR. 2011. The Pel polysaccharide can serve a structural and protective role in the biofilm matrix of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Mauff F, Razvi E, Reichhardt C, Sivarajah P, Parsek MR, Howell PL, Sheppard DC. 2022. The Pel polysaccharide is predominantly composed of a dimeric repeat of α-1,4 linked galactosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine. Commun Biol 5:502. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03453-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Wrafy F, Brzozowska E, Górska S, Gamian A. 2017. Pathogenic factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa – the role of biofilm in pathogenicity and as a target for phage therapy. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 71:78–91. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hentzer M, Teitzel GM, Balzer GJ, Heydorn A, Molin S, Givskov M, Parsek MR. 2001. Alginate overproduction affects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm structure and function. J Bacteriol 183:5395–5401. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5395-5401.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fong JNC, Yildiz FH. 2015. Biofilm matrix proteins. Microbiol Spectr 3:3. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0004-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Franklin MJ, Nivens DE, Weadge JT, Howell PL. 2011. Biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa extracellular polysaccharides, alginate, Pel, and Psl. Front Microbiol 2:167. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Billings N, Millan M, Caldara M, Rusconi R, Tarasova Y, Stocker R, Ribbeck K. 2013. The extracellular matrix component Psl provides fast-acting antibiotic defense in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003526. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murakami K, Ono T, Viducic D, Somiya Y, Kariyama R, Hori K, Amoh T, Hirota K, Kumon H, Parsek MR, Miyake Y. 2017. Role of psl genes in antibiotic tolerance of adherent Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02587-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02587-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farrant KV, Spiga L, Davies JC, Williams HD. 2020. Response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the innate immune system-derived oxidants hypochlorous acid and hypothiocyanous acid. J Bacteriol 203:e00300-20. doi: 10.1128/JB.00300-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. da Cruz Nizer WS, Inkovskiy V, Overhage J. 2020. Surviving reactive chlorine stress: responses of Gram-negative bacteria to hypochlorous acid. Microorganisms 8:1220. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colvin KM, Irie Y, Tart CS, Urbano R, Whitney JC, Ryder C, Howell PL, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2012. The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ Microbiol 14:1913–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02657.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mah T-F. 2014. Establishing the minimal bactericidal concentration of an antimicrobial agent for planktonic cells (MBC-P) and biofilm cells (MBC-B). J Vis Exp JoVE e50854. doi: 10.3791/50854-v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O’Toole GA. 2011. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. CP Microbiol 22:1. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liang Z, Nilsson M, Kragh KN, Hedal I, Alcàcer-Almansa J, Kiilerich RO, Andersen JB, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2023. The role of individual exopolysaccharides in antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa aggregates. Front Microbiol 14:1187708. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1187708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elias S, Banin E. 2012. Multi-species biofilms: living with friendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:990–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan CAZ, Lam LN, Biukovic G, Soh EY-C, Toh XW, Lemos JA, Kline KA. 2022. Enterococcus faecalis antagonizes Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth in mixed-species interactions. J Bacteriol 204:e0061521. doi: 10.1128/jb.00615-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colvin KM, Alnabelseya N, Baker P, Whitney JC, Howell PL, Parsek MR. 2013. PelA deacetylase activity is required for Pel polysaccharide synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 195:2329–2339. doi: 10.1128/JB.02150-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zegans ME, Wozniak D, Griffin E, Toutain-Kidd CM, Hammond JH, Garfoot A, Lam JS. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exopolysaccharide Psl promotes resistance to the biofilm inhibitor polysorbate 80. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4112–4122. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00373-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jennings LK, Storek KM, Ledvina HE, Coulon C, Marmont LS, Sadovskaya I, Secor PR, Tseng BS, Scian M, Filloux A, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL, Parsek MR. 2015. Pel is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11353–11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503058112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Razvi E, Whitfield GB, Reichhardt C, Dreifus JE, Willis AR, Gluscencova OB, Gloag ES, Awad TS, Rich JD, da Silva DP, Bond W, Le Mauff F, Sheppard DC, Hatton BD, Stoodley P, Reinke AW, Boulianne GL, Wozniak DJ, Harrison JJ, Parsek MR, Howell PL. 2023. Glycoside hydrolase processing of the Pel polysaccharide alters biofilm biomechanics and Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9:7. doi: 10.1038/s41522-023-00375-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baker P, Hill PJ, Snarr BD, Alnabelseya N, Pestrak MJ, Lee MJ, Jennings LK, Tam J, Melnyk RA, Parsek MR, Sheppard DC, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL. 2016. Exopolysaccharide biosynthetic glycoside hydrolases can be utilized to disrupt and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Sci Adv 2:e1501632. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pestrak MJ, Baker P, Dellos-Nolan S, Hill PJ, Passos da Silva D, Silver H, Lacdao I, Raju D, Parsek MR, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL. 2019. Treatment with the Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycoside hydrolase PslG combats wound infection by improving antibiotic efficacy and host innate immune activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00234-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00234-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. da Cruz Nizer WS, Inkovskiy V, Versey Z, Strempel N, Cassol E, Overhage J. 2021. Oxidative stress response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pathogens 10:1187. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Strempel N, Nusser M, Neidig A, Brenner-Weiss G, Overhage J. 2017. The oxidative stress agent hypochlorite stimulates c-di-GMP synthesis and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol 8:2311. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fong JCN, Karplus K, Schoolnik GK, Yildiz FH. 2006. Identification and characterization of RbmA, a novel protein required for the development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm structure in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 188:1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.1049-1059.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Capita R, Riesco-Peláez F, Alonso-Hernando A, Alonso-Calleja C. 2014. Exposure of Escherichia coli ATCC 12806 to sublethal concentrations of food-grade biocides influences its ability to form biofilm, resistance to antimicrobials, and ultrastructure. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1268–1280. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02283-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Villa F, Remelli W, Forlani F, Gambino M, Landini P, Cappitelli F. 2012. Effects of chronic sub-lethal oxidative stress on biofilm formation by Azotobacter vinelandii. Biofouling 28:823–833. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2012.715285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shemesh M, Kolter R, Losick R. 2010. The biocide chlorine dioxide stimulates biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis by activation of the histidine kinase KinC. J Bacteriol 192:6352–6356. doi: 10.1128/JB.01025-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lacey MM, Partridge JD, Green J. 2010. Escherichia coli K-12 YfgF is an anaerobic cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase with roles in cell surface remodelling and the oxidative stress response. Microbiology 156:2873–2886. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037887-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ghafoor A, Hay ID, Rehm BHA. 2011. Role of exopolysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and architecture. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5238–5246. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00637-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. da Cruz Nizer WS, Adams ME, Inkovskiy V, Beaulieu C, Overhage J. 2023. The secondary metabolite hydrogen cyanide protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa against sodium hypochlorite-induced oxidative stress. Front Microbiol 14:1294518. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1294518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gray MJ, Wholey W-Y, Jakob U. 2013. Bacterial responses to reactive chlorine species. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:141–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102912-142520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. da Cruz Nizer WS, Adams ME, Allison KN, Montgomery MC, Mosher H, Cassol E, Overhage J. 2024. Oxidative stress responses in biofilms. Biofilm 7:100203. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2024.100203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Flemming H-C, Wingender J. 2010. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang L, Hu Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Ulstrup J, Molin S. 2011. Distinct roles of extracellular polymeric substances in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Environ Microbiol 13:1705–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ciofu O, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2019. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents-how P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front Microbiol 10:913. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jefferson KK, Goldmann DA, Pier GB. 2005. Use of confocal microscopy to analyze the rate of vancomycin penetration through Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2467–2473. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2467-2473.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Singh R, Ray P, Das A, Sharma M. 2010. Penetration of antibiotics through Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1955–1958. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lewis K. 2001. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:999–1007. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.999-1007.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hall CW, Mah T-F. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:276–301. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grossich R, Lemos Vilches M, Costa CS, Pezzoni M. 2023. Role of Pel and Psl polysaccharides in the response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to environmental challenges: oxidative stress agents (UVA, H2O2, sodium hypochlorite) and its competitor Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 169:001301. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tseng BS, Zhang W, Harrison JJ, Quach TP, Song JL, Penterman J, Singh PK, Chopp DL, Packman AI, Parsek MR. 2013. The extracellular matrix protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by limiting the penetration of tobramycin. Environ Microbiol 15:2865–2878. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goltermann L, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2017. Importance of the exopolysaccharide matrix in antimicrobial tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa aggregates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02696-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02696-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gheorghita AA, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR, Howell PL. 2023. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm exopolysaccharides: assembly, function, and degradation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 47:fuad060. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuad060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schiller J, Arnhold J, Gründer W, Arnold K. 1994. The action of hypochlorous acid on polymeric components of cartilage. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 375:167–172. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1994.375.3.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. 1998. Degradation of hyaluronic acid, poly- and monosaccharides, and model compounds by hypochlorite: evidence for radical intermediates and fragmentation. Free Radic Biol Med 24:1396–1410. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pattison DI, Davies MJ, Hawkins CL. 2012. Reactions and reactivity of myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants: differential biological effects of hypochlorous and hypothiocyanous acids. Free Radic Res 46:975–995. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.667566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fleming D, Chahin L, Rumbaugh K. 2017. Glycoside hydrolases degrade polymicrobial bacterial biofilms in wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01998-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01998-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bottery MJ, Pitchford JW, Friman V-P. 2021. Ecology and evolution of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial communities. ISME J 15:939–948. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00832-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Luppens SBI, Kara D, Bandounas L, Jonker MJ, Wittink FRA, Bruning O, Breit TM, Ten Cate JM, Crielaard W. 2008. Effect of Veillonella parvula on the antimicrobial resistance and gene expression of Streptococcus mutans grown in a dual-species biofilm. Oral Microbiol Immunol 23:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yamakawa T, Tomita K, Sawai J. 2018. Characteristics of biofilms formed by co-culture of Listeria monocytogenes with Pseudomonas aeruginosaat low temperatures and their sensitivity to antibacterial substances. Biocontrol Sci 23:107–119. doi: 10.4265/bio.23.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Periasamy S, Nair HAS, Lee KWK, Ong J, Goh JQJ, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA. 2015. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 exopolysaccharides are important for mixed species biofilm community development and stress tolerance. Front Microbiol 6:851. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fortuna A, Collalto D, Schiaffi V, Pastore V, Visca P, Ascenzioni F, Rampioni G, Leoni L. 2022. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa DksA1 protein is involved in H2O2 tolerance and within-macrophages survival and can be replaced by DksA2. Sci Rep 12:10404. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14635-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ashby LV, Springer R, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. 2020. Evaluating the bactericidal action of hypochlorous acid in culture media. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 159:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Groitl B, Dahl J-U, Schroeder JW, Jakob U. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa defense systems against microbicidal oxidants. Mol Microbiol 106:335–350. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rosenberg M, Azevedo NF, Ivask A. 2019. Propidium iodide staining underestimates viability of adherent bacterial cells. Sci Rep 9:6483. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42906-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Herigstad B, Hamilton M, Heersink J. 2001. How to optimize the drop plate method for enumerating bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 44:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00241-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Choi K-H, Kumar A, Schweizer HP. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J Microbiol Methods 64:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ahmed MN, Porse A, Sommer MOA, Høiby N, Ciofu O. 2018. Evolution of antibiotic resistance in biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations exposed to subinhibitory levels of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00320-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00320-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Baker P, Whitfield GB, Hill PJ, Little DJ, Pestrak MJ, Robinson H, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL. 2015. Characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycoside hydrolase PslG reveals that its levels are critical for Psl polysaccharide biosynthesis and biofilm formation. J Biol Chem 290:28374–28387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.674929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gupta K, Marques CNH, Petrova OE, Sauer K. 2013. Antimicrobial tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is activated during an early developmental stage and requires the two-component hybrid SagS. J Bacteriol 195:4975–4987. doi: 10.1128/JB.00732-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Alvarez-Ordóñez A, Begley M, Hill C. 2012. Polymorphisms in rpoS and stress tolerance heterogeneity in natural isolates of Cronobacter sakazakii. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3975–3984. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07835-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental tables, figures, and methods.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.